Abstract

To address the dual challenges of freshwater scarcity and energy storage demands, battery deionization has emerged as a promising technology for simultaneous salt removal and energy recovery. Compared to the significant research advancement in cation-storage electrodes, anion-storage counterparts remain a critical bottleneck thus limiting the industrialization of battery deionization technique. Here, we employ Cu2O as a Cl− storage electrode material, by engineering the electrochemical-driven reversible synthesis-decomposition process between Cu2O and Cu2(OH)3Cl, the Cu2O electrode delivers the state-of-the-art high charge capacity of 286.3 ± 8.1 mAh g−1 and Cl− storage capacity of 203.5 ± 21.3 mg g−1 in natural seawater. Ex-situ liquid cell electrochemical transmission electron microscopy and in-situ powder X-ray diffraction unveil a continuous and spatial confirmed electrochemical-driven electrode oxidation, spatial migration and crystallization mechanism engaged in the reversible structural transformation between Cu2O and Cu2(OH)3Cl during battery deionization process. This work not only introduces a highly efficient electrode material for Cl− removal but also establishes a basis for leveraging the electrochemical-driven reversible synthesis-decomposition process and spatial confinement reversible structural transformation mechanism to design advanced electrode materials for diverse ion removal applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With over 3.2 billion people facing intensifying freshwater scarcity globally1,2, securing sustainable water management is an urgent imperative for the future of Earth. Although established desalination methods like thermal-driven, membrane-based, and electrochemical processes dominate the desalination landscape3,4,5, emerging technologies like battery deionization (BDI) offer promising advancements in capacity, and energy efficiency, and potentially reduce costs6,7,8. Among them, BDI, capable of reversibly storing ions within the crystal structure of electrode materials via Faradic reaction, thus enabling high-capacity desalination and offering energy recovery potential, is of special interest9,10,11.

During the past decade, significant advancements have led to the development of various symmetric BDI systems using anion exchange membranes12,13. Membrane-free and asymmetric BDI systems that rely heavily on developing robust and cost-effective anions storage electrode materials (CSEM) are of great interest to the community. Inspiration could come from chloride-ion storage electrodes in halide-ion batteries14,15, while most are limited to be used within organic or solid electrolytes, with their aqueous performance needing further investigation. Up to now, limited inorganic (Ag16,17,18,19,20, Bi21,22,23, NaBi3O4Cl224) and organic (Polysilsesquioxane25, PPY26 and PANI27) materials have been reported for selective Cl− capture via battery deionization or capacitive deionization mechanism28,29,30. In 2012, Pasta et al. 16 established the first BDI system with Ag serving as the CSEM through the reversible reaction (Ag(s) + Cl− − e− ↔ AgCl(s), Ksp = 1.77 × 10−10), demonstrating initial Cl− removal capabilities via Faradic reaction. Later, Nam et al. 21 explored a Bi/NaTi2(PO4)3 battery, where Bi functioned as the CSEM via the reaction (Bi(s) + H2O + Cl− − 3e− ↔ BiOCl(s) + 2H+, Ksp = 1.07 × 10−12). More recently, our group24 introduced NaBi3O4Cl2, the first dual ion-storage material for both sodium ion (Na⁺) and Cl⁻ removal. In this regard, state-of-the-art BDI devices heavily rely on rare and expensive Ag- and Bi-based CSEMs, which hinder large-scale deployment of BDI when considering the material cost and anion storage capacity.

Herein, initiated from our theoretical prediction and in-situ structural evolution observations, we engineer Cu2O within a confined sandwich space, and report a cost-effective, stable, and Ag and Bi-free Cu2O electrode as a Cl− storage electrode in BDI. During the BDI process, Cu2O undergoes an electrochemically driven reversible synthesis-decomposition process (ED-RSDP) to form Cu2(OH)3Cl, thus storing Cl− from aqueous solution, with the state-of-the-art high charge capacity of 286.3 ± 8.1 mAh g−1 and a Cl− storage capacity of 203.5 ± 21.3 mg g−1, accompanied by a 30% energy recovery efficiency, in natural seawater desalination. Ex-situ liquid cell electrochemical transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and in-situ powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) reveal the interesting spatial confined reversible structural evolution phenomena between Cu2O and Cu2(OH)3Cl. Upon positive potential being applied on the electrode, Cu2O undergoes 1) electrode oxidation; 2) chloride ion uptake; 3) CuCl+ migration, and 4) Cu2(OH)3Cl crystallization process within a confined space; followed by a reversible reduction potential applied, Cu2(OH)3Cl can be reduced into Cu2O with Cl− released. This work not only reports a highly efficient and cost-effective CSEM for Cl− removal but also establishes a basis for leveraging the ED-RSDP mechanism to design advanced electrode materials for diverse ion removal or recovery from different aqueous solutions.

Results and discussion

Thermodynamic feasibility of employing Cu2O for Cl− storage

The thermodynamic feasibility of Cu2O as a CSEM was assessed using a Pourbaix diagram considering the speciation of copper-related species in 0.6 M NaCl solution at 25 °C (Fig. 1). The corresponding formation energies (ΔfG˚) and equations are tabulated in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. Notably, Equation 2 in Supplementary Table 2 highlights the critical role of CuCl+ complex ion31, while the pH governing the interconversion between CuCl+ and Cu2(OH)3Cl. Considering the maximum permitted copper concentration in drinking water (≤1.3 mg L−1)32, the calculated pH boundary for this interconversion reaction is 5.99. The pH boundary for the interconversion between Cu(OH)2 and Cu2(OH)3Cl is calculated to be 9.37. These values define a crucial window for Equation 3, suggesting that a pH of 5.99 to 9.37 is best suitable for the conversion between Cu2O and Cu2(OH)3Cl, where typical seawater pH falls within this range24. Furthermore, a potential window of 0.18 V to 0.28 V (vs. SHE) can drive the reaction to happen, in which the water will remain stable without an electrolysis reaction. Collectively, these thermodynamic calculations support the feasible electrochemical oxidation of Cu2O to Cu2(OH)3Cl under mild pH and potential conditions, facilitating Cl− uptake; while the subsequently reversible electrochemical reduction of Cu2(OH)3Cl back to Cu2O, accompanied by Cl− release. These theoretical data suggest a promising avenue for employing Cu2O in Cl− storage and enrichment.

Cu2O synthesis and characterization

Motivated by thermodynamic favorability, a facile method33 was employed to prepare cubic Cu2O via chemical reduction of Cu(OH)2 using sodium ascorbate solution. The successful synthesis of cubic Cu2O was comprehensively characterized using various techniques. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns (Supplementary Fig. 1) revealed a series of diffraction peaks that well matched the cuprite Cu2O phase (ICSD no. 63281), devoid of any discernible impurity peaks. High-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) imaging (Supplementary Fig. 2a) confirmed the formation of cubic Cu2O nanoparticles with an average size of 200 nm. The monovalent state of copper (Cu(I)) was unambiguously confirmed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (Supplementary Fig. 2e), which exhibited the characteristic satellite peaks of Cu2O located at 945 eV34 without any discernible CuO satellite peaks.

Electrochemical performance evaluation

Figure 2a illustrates the electrode preparation procedures. Briefly, a Cu2O slurry is prepared using synthetic Cu2O powder. The slurry is then drop-casted onto a carbon cloth substrate. After drying, the coated carbon cloth is masked with insulation tape, leaving only the edges exposed. This “sandwich-like” Cu2O electrode is expected to be with better cycling stability regarding the electrode material detachment during electrochemical cycling study compared to the traditional electrode fabrication. The as-fabricated electrode is further employed as the working electrode in a three-electrode configuration for galvanostatic chronopotentiometry and cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements. Preliminary experiments revealed rapid capacity decay for a bare Cu2O electrode (Supplementary Fig. 3a), accompanied by precipitate formation at the bottom of the cell (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) identified the precipitate as atacamite Cu2(OH)3Cl (ICSD-61252) (Supplementary Fig. 2c), an insoluble substance (Ksp = 2.04 × 10−35). These observations suggest the potential of Cu2O for Cl− storage, despite its limited cyclability.

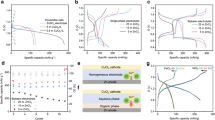

a Flow chart of electrode fabrication, electrochemical test and performance. b Cycle performance of Cu2O electrodes in 50 cycles in 0.6 M NaCl solution at pH = 7 with progressive specific currents (0.2 A g −1, 0.4 A g −1, 0.8 A g −1) applied. c Redox potential curves of a typical Cu2O electrode at different specific currents in 0.6 M NaCl solution at pH = 7. No iR compensation. d Comparison of charge capacity versus specific current of reported materials17 and Cu2O electrode. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To address the electrode structural stability and achieve high capacity, the “sandwich-like” electrode configuration was developed using insulation tape. In this design, Cl− ions migrate only through the exposed edges, while the conversion product, Cu2(OH)3Cl, is confined to the carbon cloth by the tape. The carbon cloth fibers further hinder its lateral detachment, ensuring good contact with the current collector. The cyclability of sandwich-like electrode was evaluated using galvanostatic chronopotentiometry over 50 cycles (Fig. 2b). At a specific current of 0.2 A g−1, the electrode delivered a high average charge capacity of 299.6 mAh g−1 during the initial five cycles, corresponding to an estimated 78% conversion of Cu2O within the electrode based on theoretical capacity. The first three redox potential profiles are presented in Supplementary Fig. 4. The initial oxidation profile (gray line) exhibits high-potential fluctuations, but subsequent cycles exhibit stable curves, indicating consistent electrochemical behavior of the as-fabricated Cu2O electrode. Even at increased specific current (0.4 A g−1 and 0.8 A g−1), the average charge capacity remained around 292 mAh g−1 and 271.5 mAh g−1, respectively. Notably, returning to 0.2 A g−1 for the final 35 cycles, resulted in an impressive average capacity of 286.3 ± 8.1 mAh g−1, representing a remarkable 95% retention of the initial capacity. This improved cyclability performance highlights the effectiveness of the implemented structural engineering in confining the conversion product within electrode porous space and promoting electrode stability. Despite this improvement, some electrodes showed slight instability (Supplementary Fig. 5), indicating performance variability. This variability is likely attributable to inconsistencies arising from manual preparation, specifically in the slurry deposition and tape attachment steps. Importantly, this method could extend to similar BDI electrode materials with insoluble redox products and significant volume expansion, resulting in mechanistic instability. The scalability of this design can be achieved by iteratively stacking the current BDI cell, similar to the assembly of commercial silicon solar panels.

To confirm the Cl− uptake within the electrode, energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) mapping was performed on cross-sections of Cu2O electrodes before and after electrochemical oxidation (Supplementary Fig. 6c, f). Compared to the unoxidized control (only immersed in NaCl solution), a significant increase in the chlorine signal was observed on the oxidized electrode. This observation provides preliminary evidence for Cl− storage within the electrode. Furthermore, the XRD patterns of Cu2O electrodes (Supplementary Fig. 1) after a full cycle (oxidation and reduction), revealed the formation of atacamite Cu2(OH)3Cl and its subsequent conversion back to Cu2O.

The influence of specific current on the redox behavior of the electrodes was investigated (Fig. 2c). As the specific current increased, the oxidation potential platforms shifted to more positive, and the reduction potential platforms negatively shifted. This resulted in a wider potential difference during cycling, also known as voltage drop35, signifying lower energy output during discharge. The Cu2O electrode exhibited a lower potential difference of 0.29 V at a specific current of 0.2 A g−1(Supplementary Table 3), compared to Bi electrode (0.45 V22), with more efficient electrode recovery and higher energy efficiency. Notably, the Cu2O electrode in this work demonstrates the state-of-the-art high charge capacity and a wider operational specific current range compared to conventional CSEMs reported in battery deionization literature (Fig.2d, Supplementary Table 4).

Reaction mechanism of ED-RSDP about Cu2O/Cu2(OH)3Cl

The multi-stage character of the Cu2O electrode’s charge/discharge profiles (Fig. 2c) necessitates further investigation of the underlying mechanisms, beyond simply establishing the initial and final states. To this end, cyclic voltammetry (CV) was performed on the Cu2O electrode after 50 cycles at 0.5 mV s⁻¹. The CV curve (Fig. 3a) exhibits two distinct oxidation peaks (O1 and O2 at −0.075 V and 0.315 V, respectively), and three reduction peaks (R1, R2 and R3 at 0.09 V, −0.28 V and −0.54 V, respectively). The corresponding charge associated with each peak is quantified in Fig. 3b. For a detailed analysis, the potential profile of a single cycle (Fig. 3c) is segmented into five stages corresponding to the five observed CV peaks. Referring to the reported literature30, we assign O2 at 0.315 V to the oxidation of Cu(I) to Cu(II), corresponding to the conversion of Cu2O to Cu2(OH)3Cl. Conversely, R2 at −0.28 V is attributed to the reduction of Cu(II) back to Cu(I), signifying the conversion of Cu2(OH)3Cl to Cu2O. An additional reduction peak (R3) at −0.54 V suggests the presence of a Cu2(OH)3Cl population with poor electrical contact to the carbon cloth current collector, resulting in an overpotential penalty during reduction36. This implies two Cu2(OH)3Cl populations: one readily reduced at R2 with good conductivity and another requiring a higher initial potential (R3) due to limited conductivity. This difference in conductivity is further reflected by the “potential valley” at R3 in the discharge profile (Fig. 3c), potentially representing a stage where poorly connected Cu2(OH)3Cl particles establish better contact with the current collector. Besides, the presence of a minor oxidation peak (O1) at −0.075 V, suggests the unintended formation of a small amount of elemental copper during reduction process37.

a CV curve of the Cu2O electrode after 50 charge/discharge cycles at a scan rate of 0.5 mV s−1 in 0.6 M NaCl solution at pH = 7., with identified stages. No iR compensation. b Charge contribution of each peak in the CV curve; c Potential profile of Cu2O electrode with identified stages. d Illustration of homemade in-situ PXRD cell. This cell is a three-electrode system with reference electrode (RE), counter electrode (CE) and working electrode (WE). e Charge/discharge profile obtained during in-situ PXRD measurement; f Corresponding in-situ PXRD pattern collected during a single charge/discharge cycle; g Schematic illustration of crystal structure evolution during the reversible electrochemical reaction. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To elucidate the real-time crystallographic structure conversion during Cu2O/Cu2(OH)3Cl transformation under electrochemical desalination, in-situ PXRD was employed. A custom-designed in-situ PXRD cell, assembled as depicted in Fig. 3d, was utilized on our in-house diffractometer to collect data specific to the desalination process. During the electrochemical oxidation at 0.2 A g−1 (Fig. 3a), the in-situ PXRD pattern (Fig. 3b) from 0 V to 0.7 V revealed a gradual intensity decrease of Cu2O diffraction peaks, particularly (111) and (200). The decrease coincided with a concurrent rise in the intensity of Cu2(OH)3Cl peaks, particularly (011) and (210). These observations directly correlate with the decomposition of Cu2O and the corresponding formation of Cu2(OH)3Cl. Under the influence of the positive potential during oxidation, Cu(I) in Cu2O loses electrons being transferred to Cu(II) upon reaching the onset potential. Thermodynamically favored for Cl− uptake in NaCl solutions (Fig. 1), Cu2(OH)3Cl becomes the primary product. By the cutoff potential of 0.7 V, the in-situ PXRD data confirms complete consumption of Cu2O.

The subsequent reduction period at −0.2 A g−1 (Fig. 3b) from 0.7 V to −0.8 V exhibited a gradual increase in Cu2O diffraction peak intensity, accompanied by a corresponding decrease in Cu2(OH)3Cl peak intensity. Under the influence of the applied reduction potential, Cu(II) within Cu2(OH)3Cl gain electrons, reverting to Cu(I) atoms and reforming Cu2O. As indicated by Reaction 8 in Supplementary Table 2, Cu2O is the thermodynamically favored product in a neutral aqueous solution compared to hydrolysable CuCl. Notably, a portion of Cu2(OH)3Cl remains even after reaching the reduction cutoff potential of −0.8 V. Additionally, no significant diffraction peak indicative of elemental copper was detected. Collectively, the in-situ PXRD data strongly evidence for the reversible conversion of Cu2O to Cu2(OH)3Cl during electrochemical oxidation and the subsequent regeneration of Cu2O from Cu2(OH)3Cl during electrochemical reduction under mild pH and potential conditions (Fig. 3f). This process can be termed electrochemical-driven reversible synthesis-decomposition process (ED-RSDP).

Ex-situ liquid cell electrochemical TEM

To gain deeper insights into the morphological evolution and product spatial migration during ED-RSDP reaction, ex-situ liquid cell electrochemical TEM was used to capture a time-resolved sequence of high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) images of a single Cu2O particle elolution (Fig. 4a–d). Prior to electrochemical oxidation, the particle exhibited a well-defined cubic structure with concentrated Cu signals (Fig. 4a). Quantitative EDS analysis revealed negligible Cl/Cu molar ratios in two designated regions (Fig. 4d). After 5 minutes of electrochemical oxidation in 0.6 M NaCl solution, the contrast of cubic Cu2O diminished, accompanied by the formation of a surrounding gel-like product (Fig. 4a). The Cu signal distribution broadened outwards (Fig. 4b), while a distinct Cl signal appeared (Fig. 4c). Notably, the Cl/Cu molar ratio in the green region reached 0.386 (Fig. 4d), approaching the theoretical value of 0.5 for Cu2(OH)3Cl, indicating that oxidation product spatially migrated away from the original Cu2O particle and eventually formed Cu2(OH)3Cl product near the original Cu2O particle.

Time-resolved ex-situ liquid cell electrochemical TEM images for a single Cu2O particle. a STEM-HAADF image. EDS mapping of b Cu and c Cl. d Molar ratio of Cl/Cu resolved from EDS in the blue and green areas. e Interfacial Cu(I) oxidation-migration and crystallization mechanism with a bare Cu2O electrode. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Prolonged oxidation resulted in further decomposition of Cu2O (Fig. 4a) and broader spatial distribution of the Cu signal (Fig. 4b) along with time. A Cl/Cu molar ratio of 0.488 approaches 0.5 in the green region at 15 mins, while the blue region retained a lower Cl/Cu molar ratio of 0.392 due to the presence of residual Cu2O (Fig. 4d). The expanding Cu distribution suggests the mobility of the oxidation product, which is supposed to be CuCl+ under a locally acidic environment induced by the positive potential at the electrode38,39,40. As mobile CuCl+ migrates away from the Cu2O interface under a local acidic reaction environment, a pH-rising bulk solution environment (pH >5.99) promotes its reaction with OH− anions to crystallize into Cu2(OH)3Cl (Fig. 4e). The presence of larger, needle-like products identified as Cu2(OH)3Cl in distal regions (Supplementary Fig. 7d) further supports the mobile and migration crystallization behavior of CuCl+ cations. These larger, crystallized Cu2(OH)3Cl particles likely exhibit poor electrochemical kinetics, hindering their reduction and contributing to the observed potential valley in Fig. 3c.

Briefly, the ex-situ liquid cell electrochemical TEM observations (Fig. 4) reveal a unique characteristic of Cu2O electrochemical oxidation in Cl−-rich solutions: the initial formation of mobile CuCl+ under acidic conditions on the electrode surface, followed by its gradual crystallization as Cu2(OH)3Cl after spatial migration. This migratory crystallization mechanism leads to widespread product distribution and inherently limits electrode cyclability. Thus, as demonstrated in this work, the implementation of a sandwich-like electrode configuration (Fig. 4f) effectively mitigates this drawback and is crucial in achieving stable cyclability over 50 cycles with a 95% retention (Fig. 2b). This finding underscores the significant role of electrode configuration engineering in improving cyclability based on ex-situ liquid cell electrochemical TEM observation.

Cl− storage performance of employing Cu2O in desalination battery system

To assess the practical chloride-storage capacity of the engineered Cu2O electrode for natural seawater desalination via battery deionization, a battery desalination cell was constructed by coupling the Cu2O electrode with a NaTi2(PO4)3 electrode (Fig. 5a). The complete reaction equation is shown below:

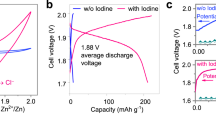

a Photograph of the assembled desalination cell. b Schematic diagram of the desalination cell and its components. c Cl− storage capacity of a Cu2O electrode compared to a Cu2O-free electrode in seawater. d Comparison of Cl− storage capacities for various reported materials and the material in this work at different electrolyte concentrations. e Charge/discharge voltage profiles of the desalination battery in 0.6 M NaCl solution. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Details of the cell configuration and assembly are provided in Fig. 5b. Conventional face-to-face cell configurations are susceptible to product leakage from the Cu2O electrode. To address this challenge, an external clamp was implemented using an acrylic plate and a polymer gasket, effectively confining product migration while allowing unimpeded ion transport, similar to the previously employed insulation tape (Fig. 5b). Following influent 2 mL electrolyte and electrode immersion, a specific current of 0.2 A g⁻¹ was applied to initiate simultaneous seawater desalination and battery charging. The initial and final Cl− concentration of the influent electrolyte was determined using anion chromatography. The practical performance of the Cu2O electrode was evaluated in both 0.6 M NaCl solution and natural seawater from Dapeng Bay, respectively. The Cu2O electrode exhibited a remarkable practical Cl− storage capacity of 203.5 ± 21.3 mg g⁻¹ in seawater (Fig. 5c). As illustrated in Fig. 5d, the practical Cl− storage capacity demonstrated in this work surpasses those of all the reported CSEMs for battery deionization and pseudocapacitive deionization, highlighting its potential for effective desalination of high-salinity seawater (Supplementary Table 5). Additionally, we noticed that the price of Cu2O is lower than that of Bi and Ag (e.g., 6.2 USD kg−1 for Cu, 10.9 USD kg−1 for Bi and 602 USD kg−1 for Ag)41, suggesting a significant economic effectiveness of employing Cu2O for chloride desalination compared to Bi and Ag (Supplementary Table 6). To address environmental concerns about copper leaching, inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) analysis revealed a Cu2+ concentration of 176.81 ± 25.03 μg L−1 in 0.6 M NaCl of this cell after desalination. This concentration is well below the 1.3 mg L⁻1 limit established by the United States Environmental Protection Agency for copper in drinking water32.

To evaluate the energy recovery efficiency of Cu2O/NaTi2(PO4)3 desalination battery, a complete charge/discharge cycle was performed (Fig. 5e). The battery exhibits charging and discharging voltages of 1.08 V and 0.36 V, respectively. This significant voltage drop (0.72 V) can be attributed to three main factors: (i) the potential difference of the Cu2O/Cu2(OH)3Cl electrode (0.29 V, as previously determined); (ii) the potential difference of the NaTi2(PO4)3 cathode (approximately 0.05 V, Supplementary Fig. 8), and (iii) the internal resistance of the cell. The combined effect of these factors results in a relatively low energy recovery efficiency of approximately 30%. This value is estimated based on the shaded areas under the charge and discharge curves in Fig. 5e, which represent the energy stored during charging and recovered during discharge, respectively. Additionally, a charge imbalance is observed, with a lower discharge capacity compared to the charging capacity. This mismatch further contributes to the reduced energy recovery rate. Compared to the commercially available energy storage devices with an 80% energy recovery rate36,37, to further improve the energy recovery rate within the present Cu2O/NaTi2(PO4)3 deionization battery, the conductivity and mass transfer resistance can be fine-tuned in futural work.

In summary, this work presents the demonstration of the ED-RSDP mechanism involving Cu2O/Cu2(OH)3Cl within a BDI process. The Cu2O electrode achieved the state-of-the-art high Cl− storage capacity of 203.5 ± 21.3 mg g−1, highlighting its potential for seawater desalination. A continuous and spatial confirmed electrochemical-driven electrode oxidation, spatial migration and crystallization mechanism has been unraveled during the reversible transformation of Cu2O into Cu2(OH)3Cl in BDI process, which requires further electrode engineering to improve its cycling stability. Despite this limitation, this approach offers a promising pathway for designing cost-effective faradaic CSEMs by utilizing readily available transition metals copper (Cu), which could be expanded to other elements like iron (Fe) and zinc (Zn). Considering the success of electrode engineering in this work, further research is warranted to optimize both electrode structure and battery configuration to enhance electrode stability and achieve higher energy recovery rates. This work not only introduces a highly efficient electrode material for Cl− removal but also establishes a basis for leveraging the ED-RSDP and spatial confinement reversible structural transformation mechanism to design advanced electrode materials for diverse ion removal applications.

Methods

Synthesis and fabrication

Cubic Cu2O material was synthesized via the reduction of a Cu(OH)2 precipitate33. Briefly, 4 M NaOH solution was added dropwise into 500 mL of 0.1 M CuSO4 solution under vigorous stirring until the pH reached 10. The resulting Cu(OH)2 precipitate was then reduced by the slow addition of 200 mL of 0.2 M sodium ascorbate solution. After stirring for 1 h, the product was isolated by centrifugation and washed thoroughly with deionized water. Finally, the precipitate was dried under a vacuum at 40 °C for 12 h.

NaTi2(PO4)3 powder42 was prepared via solid-state melting method. Stoichiometric amounts of Na2CO3, TiO2, (NH4)2HPO4 were ball-milled for 3 h. The resulting precursor was calcined in air at 500 °C for 5 h, followed by a subsequent calcination at and 900 °C for 24 h. The product was then washed and filtrated three times before drying at 80 °C in the air for 12 h. To improve the conductivity of NaTi2(PO4)3, the as-synthesized NaTi2(PO4)3 was ball-milled with glucose in a mass ratio of 9:1 for 3 h. This was followed by sequential calcination in an Ar atmosphere at 800 °C for 3 h.

To fabricate the Cu2O electrode, a slurry was prepared by mixing 0.7 g Cu2O, 0.2 g acetylene black and 0.1 g PVDF in 8 mL NMP. The slurry was then drop-cast onto carbon cloth before being dried under vacuum at 40 °C. To enhance electrode cyclability, a “sandwich-like” configuration (Supplementary Fig. 9a) was achieved using insulation tape. The small electrode for CV and galvanostatic chronopotentiometry is 1 cm*2 cm. The mass loading is around 3 mg.

Material characterization

Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) of the material was confirmed using a 9 kW Rigaku SmartLab machine with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). The scanning rate was 20° min−1 and the step size was 0.02°. The morphology and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping image of Cu2O nano-powder and Cu2O electrode was obtained by a Zeiss Merlin scanning electron microscopy (SEM) operated at an acceleration voltage of 20 kV. High-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) imaging, EDS mapping analyses, and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) of Cu2O powder were performed on an FEI Talos F200X G2 apparatus at 200 kV. The X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) for valence states analysis of Cu2O nano-powder was obtained from a PHI 5000 Versaprobe III instrument.

Electrochemical measurement

All the electrochemical characterizations were performed under an inert (Argon) atmosphere and conducted on an electrochemical workstation (Lvium-N-Stat, lvium technologies B.V.) at 25 °C. Argon gas was input into the cell but doesn’t stir the electrolyte. Half-cell reactions were investigated by galvanostatic chronopotentiometry in a three-electrode configuration (Supplementary Fig. 9b). This configuration consisted of the working electrode (Cu2O electrode), a counter electrode (carbon rod), and a reference electrode (saturated calomel electrode, SCE, in saturated KCl solution, 0.248 V vs SHE). No iR compensation.

In-situ PXRD measurement

In-situ PXRD measurements were performed using a homemade three-electrode device from our lab colleagues24 as shown in Supplementary Fig. 9c. Cu2O slurry was deposited onto the center of a circular carbon cloth. After drying, the carbon cloth was integrated into the in-situ device, which was then mounted in the XRD instrument. The device was filled with 0.6 M NaCl solution. An oxidation current of 0.2 A g−1 and a reduction current of −0.2 A g−1 were applied.

BDI cell fabrication and performance

To assess the practical Cl− storage capacity in seawater, considering both capacity and result reliability, a custom-designed desalination battery cell was fabricated (Supplementary Fig. 9d). The Cu2O electrode sized 2 cm*3 cm and containing approximately 50 mg of electrode material was fabricated. The Cu2O/NaTi2(PO4)3 electrode pair was assembled within the cell, followed by the injection of 2 mL of seawater. After a charging and desalination cycle, the 2 mL of seawater was extracted and diluted 500 times for Cl⁻ concentration determination using anion chromatography. Five parallel experiments were conducted, and standard deviation was calculated. The Cl− concentration in the solution was determined by anion chromatography (AC) (Aquion, Thermo Fisher). The concentration of leached Cu2+ was determined by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) using a Thermo Fisher iCAP RQ instrument.

Ex-situ liquid cell electrochemical TEM measurement

Ex-situ liquid cell transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was employed to capture the transformation of Cu₂O to Cu₂(OH)₃Cl. 1 mg of cubic Cu₂O was dispersed in 1 mL of ethanol and 1 mg of oxidized graphene to enhance conductivity. After 10 mins of sonication, a drop of the solution was deposited onto a gold grid coated with a carbon film and a coordinate system (QUANTIFOIL® R 1.2/1.3, Au 200). The loaded grid served as the working electrode in a custom-built three-electrode system (Supplementary Fig. 9e). The Au grid was sandwiched between a glass substrate and an ITO conductive glass, with the counter electrode (Pt wire) positioned directly opposite. Before initiating the reaction, an adequate volume of 0.6 M NaCl electrolyte was added to immerse the Au grid, reference electrode, and Pt wire. This custom-built three-electrode system confined the reaction to restricted space, minimizing exposure of the working electrode and enabling precise control of the applied current. A constant current of 1 μA was applied to the grid for 5 mins at each stage. Afterwards, the grid was washed, dried under infrared light, and imaged using TEM. The same particle could be relocated on the grid at each stage, allowing for HAADF and EDS mapping of the individual Cu₂O particle.

Data availability

The source data generated in this study are provided in Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of Food and Agriculture 2020, 26–31 (2020).

Elimelech, M. & Phillip, W. A. The future of seawater desalination: energy, technology, and the environment. Science 333, 712–717 (2011).

Ghaffour, N., Missimer, T. M. & Amy, G. L. Technical review and evaluation of the economics of water desalination: current and future challenges for better water supply sustainability. Desalination 309, 197–207 (2013).

Shahzad, M. W., Burhan, M., Ang, L. & Ng, K. C. Energy-water-environment nexus underpinning future desalination sustainability. Desalination 413, 52–64 (2017).

Greenlee, L. F., Lawler, D. F., Freeman, B. D., Marrot, B. & Moulin, P. Reverse osmosis desalination: water sources, technology, and today’s challenges. Water Res. 43, 2317–2348 (2009).

Oren, Y. Capacitive deionization (CDI) for desalination and water treatment—past, present and future. Desalination 228, 10–29 (2008).

AlMarzooqi, F. A., Ghaferi, A. A., Saadat, I. & Hilal, N. Application of capacitive deionisation in water desalination: a review. Desalination 342, 3–15 (2014).

Zhang, C., He, D., Ma, J., Tang, W. & Waite, T. D. Faradaic reactions in capacitive deionization (CDI)-problems and possibilities: a review. Water Res. 128, 314–330 (2018).

Srimuk, P., Su, X., Yoon, J., Aurbach, D. & Presser, V. Charge-transfer materials for electrochemical water desalination, ion separation and the recovery of elements. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 517–538 (2020).

Son, M. et al. Simultaneous energy storage and seawater desalination using rechargeable seawater battery: feasibility and future directions. Adv. Sci. 8, 2101289 (2021).

Khodadousti, S. & Kolliopoulos, G. Batteries in desalination: a review of emerging electrochemical desalination technologies. Desalination 573, 117202 (2024).

Kim, T., Gorski, C. A. & Logan, B. E. Low energy desalination using battery electrode deionization. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 4, 444–449 (2017).

Smith, K. C. Theoretical evaluation of electrochemical cell architectures using cation intercalation electrodes for desalination. Electrochim. Acta 230, 333–341 (2017).

Xue, Z., Gao, Z. & Zhao, X. Halogen Storage Electrode Materials for Rechargeable Batteries. Energy Environ. Mater. 5, 1155–1179 (2022).

Zhao, X., Zhao-Karger, Z., Fichtner, M. & Shen, X. Halide-based materials and chemistry for rechargeable batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 5902–5949 (2020).

Pasta, M., Wessells, C. D., Cui, Y. & Mantia, L. F. A desalination battery. Nano Lett. 12, 839–843 (2012).

Zhao, W., Guo, L., Ding, M., Huang, Y. & Yang, H. Y. Ultrahigh-desalination-capacity dual-ion electrochemical deionization device based on Na3V2(PO4)3@C-AgCl electrodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 40540–40548 (2018).

Srimuk, P., Husmann, S. & Presser, V. Low voltage operation of a silver/silver chloride battery with high desalination capacity in seawater. RSC Adv. 9, 14849–14858 (2019).

Liang, M. et al. Combining battery-type and pseudocapacitive charge storage in Ag/Ti3C2Tx MXene electrode for capturing chloride ions with high capacitance and fast ion transport. Adv. Sci. 7, 2000621 (2020).

Chen, F., Huang, Y., Guo, L., Ding, M. & Yang, H. Y. A dual-ion electrochemistry deionization system based on AgCl-Na0.44MnO2 electrodes. Nanoscale 9, 10101–10108 (2017).

Nam, D. H. & Choi, K. S. Bismuth as a new chloride-storage electrode enabling the construction of a practical high capacity desalination battery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 11055–11063 (2017).

Shi, W. et al. Bismuth nanoparticle-embedded porous carbon frameworks as a high-rate chloride storage electrode for water desalination. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 21149–21156 (2021).

Chen, F. et al. Dual-ions electrochemical deionization: a desalination generator. Energy Environ. Sci. 10, 2081–2089 (2017).

Wei, W. et al. Electrochemical driven phase segregation enabled dual-ion removal battery deionization electrode. Nano Lett. 21, 4830–4837 (2021).

Silambarasan, K. & Joseph, J. Redox-polysilsesquioxane film as a new chloride storage electrode for desalination batteries. Energy Technol. 7, 1800601 (2019).

Kong, H., Yang, M., Miao, Y. & Zhao, X. Polypyrrole as a novel chloride-storage electrode for seawater desalination. Energy Technol. 7, 1900835 (2019).

Zornitta, R. L., Ruotolo, L. A. M. & de Smet, L. C. P. M. High-performance carbon electrodes modified with polyaniline for stable and selective anion separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 290, 120807 (2022).

Zhang, Z. & Li, H. Promoting the uptake of chloride ions by ZnCo-Cl layered double hydroxide electrodes for enhanced capacitive deionization. Environ. Sci. Nano 8, 1886–1895 (2021).

Wang, K. et al. Chloride pre-intercalated CoFe-layered double hydroxide as chloride ion capturing electrode for capacitive deionization. Chem. Eng. J. 433, 133578 (2022).

Xing, S. et al. Reactive P and S co-doped porous hollow nanotube arrays for high performance chloride ion storage. Nat. Commun. 15, 4951 (2024).

Zhao, H., Chang, J., Boika, A. & Bard, A. J. Electrochemistry of high concentration copper chloride complexes. Anal. Chem. 85, 7696–7703 (2013).

Regulations, E. Maximum contaminant level goals and national primary drinking water regulations for lead and copper; final rule. Fed. Regist. 56, 26460 (1991).

Sun, S. et al. Cuprous oxide (Cu2O) crystals with tailored architectures: a comprehensive review on synthesis, fundamental properties, functional modifications and applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 96, 111–173 (2018).

Vasquez, R. P. Cu2O by XPS. Surf. Sci. Spectra 5, 257–261 (1998).

Wu, J. et al. Dissociate lattice oxygen redox reactions from capacity and voltage drops of battery electrodes. Sci. Adv. 6, 3871 (2020).

Lu, Q. et al. Uniform Zn deposition achieved by Ag coating for improved aqueous zinc-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 16869–16875 (2021).

Walters, L. N., Huang, L.-F. & Rondinelli, J. M. First-principles-based prediction of electrochemical oxidation and corrosion of copper under multiple environmental factors. J. Phys. Chem. C. 125, 14027–14038 (2021).

Rudd, N. C. et al. Fluorescence confocal laser scanning microscopy as a probe of pH gradients in electrode reactions and surface activity. Analy. Chem. 77, 6205–6217 (2005).

Landon, J., Gao, X., Omosebi, A. & Liu, K. Emerging investigator series: local pH effects on carbon oxidation in capacitive deionization architectures. Environ. Sci.: Water Res. Technol. 7, 861–869 (2021).

Lei, Y., Song, B., van der Weijden, R. D., Saakes, M. & Buisman, C. J. N. Electrochemical induced calcium phosphate precipitation: importance of local pH. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 11156–11164 (2017).

Geological Survey U. S., Mineral Commodity Summaries 2022. 55 (Geological Survey U. S., 2022).

Zheng, L. D., Young, K., Xiang, W., Craig, C. & Yet-Min, C. Towards high power high energy aqueous sodium-ion batteries: the NaTi2(PO4)3/Na0.44MnO2 system. Adv. Energy Mater. 3, 4 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2021YFA1202500, H.C.), Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Soil and Groundwater Pollution Control (No. 2023B1212060002, H.C.), the Stable Support Plan Program of Shenzhen Natural Science Foundation (No. 20231122110855002, H.C.), Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Committee (No. KCXST20221021111208018, H.C.; No. JCYJ20241202123900001, X.F.), High level of special funds (G03034K001, H.C.), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2023A1515110125, X.F.), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2023M741533, X.F.), Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (No. GZC20231035, X.F.) from SUSTech. The ICP-MS, AC, XRD, SEM, TEM and STEM-EDS data were collected by using equipment maintained by Southern University of Science and Technology core Research Facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.C. and S.Y. conceived the idea and designed the experiments. S.Y. synthesized the materials and design and assembled the electrode configuration and battery construction. S.Y. conducted the electrochemical, PXRD, and in-situ PXRD and ex-situ liquid cell electrochemical TEM. X.G. executed the AC test for Cl− concentration. R.W. carried out the SEM measurements. X.F. handled the HRTEM imaging. X.L. conducted the ICP-MS experiments. W.W. designed and provided the in-situ PXRD cell. S.Y. wrote the manuscript. H.C. supervised the work and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Xitong Liu, Xingtao Xu, Xiangyu Zhao and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, S., Gu, X., Feng, X. et al. Engineering the reversible redox electrochemistry on cuprous oxide for efficient chloride ion uptake. Nat Commun 16, 2282 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57605-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57605-z