Abstract

Human substance needsśś have been enriched by the development of smart-responsive materials possessing unique responsiveness and mechanical variability. However, acquiring these features in photoresponsive energy-driven elastomers is challengeable but highly desirable. Here, we report fabrication of physically-crosslinked elastomers based on an aliphatic polycarbonate terminated with one azobenzene derivative as the end group. Upon irradiation of UV light, the aliphatic polycarbonate shows unusual mechanical transformation from trans-azobenzene-rich elasticity to cis-azobenzene-rich plasticity, which is contrary to the photo-triggered mechanics of other azopolymers. This indicates that stronger interaction may be established between the terminated cis-azobenzenes and the benzene rings in the side chain of polymer, leading to a higher crosslinking density appeared in the cis-azobenzene-rich sample. This azobenzene-terminated polymer is an energy-driven elastomer, which has photo-switchable supramolecular interactions, showing photo-tunable mechanical properties (the half-life period of the cis-azobenzene is 16.9 h). More interestingly, the photoinduced mechanical change occurs at room temperature, enabling the aliphatic polycarbonate to behave as non-thermally switchable ultra-strong adhesive for different substrates, which is specifically suitable for smart dressings to promote wound healing. This switchable mechanical feature of elastomers may be a reference for smart elastomers towards advanced applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In nature, biological populations can sense the external environment and deform in response to stimuli. For example, sunflowers are sun-oriented, and mimosas rapidly close leaves when stimulated by the outside world. So nature has inspired many smart materials and structures to acquire characteristics such as physical intelligence, foldable compression, and impact resistance1,2,3,4,5, allowing them to realize complex and controllable motor functions6,7,8,9. However, smart materials with chemically-crosslinked networks often suffer from mechanical instability and microphase segregation9,10,11,12, making the precisely-switchable mechanics of elastomers challenging because their polymer chains in the network do not have sufficient mobility to respond to mechanical transformations13,14. A prospective approach to address these challenges is to formulate non-covalently crosslinked elastomers that can be reversibly softened and hardened at room temperature.

Azobenzene (AZ), as one of the most favorite photoresponsive moieties, can remotely and instantly control material deformation in a precise and non-contact manner15,16,17,18. AZ-containing polymers (or azopolymers) with elegant molecular design can demonstrate reversible solid-liquid transformations upon photoirradiation due to the trans-cis isomerization1,19,20,21,22, bestowing azopolymers with many attractive properties, like self-repairing6,7,8,9, mechano-sensing1,2,3,4,5,20,21,22, and mass transportation8, which has been used to control structural colors, macroscopic deformation, and fluid properties23,24,25,26,27. More interestingly, one single AZ terminal group can effectively influence the whole macromolecule chain by molecular isomerization1,24. For example, Du et al. prepared an AZ-terminated polymer and investigated the effect of hydrophobic-hydrophilic change of AZ groups on solution aggregations and rheological properties after photoisomerization24, leading to remarkable changes in rheological behaviors of the polymer solution. Guo et al. utilized one AZ-terminated polymer matrix to modulate the thermal behaviors and mechanical properties of the material by using its photoresponsive switching function28, thus exploiting its applications in anti-counterfeiting, security labels, and photo-controlled switchable adhesives28,29,30. Although researches on AZ-terminated polymers have progressed favorably, there is still a great scientific challenge to control the segmental motion of polymer networks1,2,3,24.

Recently, one AZ compound was introduced into an aliphatic polycarbonate (APC) network by physical blending to acquire fast self-repairing behaviors for completing the wound closure by tying a knot8. However, the composite does not possess photo-switchable mechanical properties. To the best of our knowledge, the selection of an AZ-terminated APC (AZ-APC) for preparing non-covalently elastomer has not yet been reported, let along the study of its photo-tunable mechanical transition. Here, we report unusual photo-tunable mechanical transformation of AZ-APCs, synthesized with ring-opening bulk polymerization with an AZ derivative as the initiator. The obtained AZ-APCs exhibit elasticity at room temperature due to physical crosslinking formation. Upon irradiation of UV light, AZ-APCs show reversible changes between elasticity to plasticity (Fig. 1). This mechanical switching can be in-situ accomplished at room temperature, relying solely on AZ-APCs themselves without any functional additives, which allows for its photo-switchable adhesion on different substrates, particularly suitable for medical dressings to promote wound healing. This work delivers a photoinduced mechanical feature strategy that can be applied as advanced smart adhesion by modulating the dynamic mechanical properties of elastomers.

a Structural transformation upon photoisomerization b Molecular weights and their distributions. c An illustrative diagram of the potential energy between the cis-AZ-rich plastics and the trans-AZ-rich elastomer. Thereby achieving a photoinduced reversible transition between plasticity and elasticity to yield a flexible molding.

Results

Design of mechanical variability of AZ-APCs

The terminal group of one macromolecule can not only modulate the physicochemical feature of polymer (eg., glass transition temperature (Tg), relaxation process and viscosity, etc.), but also offer the possibility of developing responsive mechanical transformations1,31. Recently, one hydrophilic poly(ethylene glycol) monomethyl ether was chosen as the terminal group of one APC to acquire strong mechanic strength and shape-memory function. However, it still could not overcome the issues of traditional APCs, like non-mechanical transformability, slow responsiveness, etc32,33,34,35. If one APC is terminated by an AZ derivative, it should be practicable to acquire the photo-modulated mechanical transformation. As shown in Fig. 1a and Supplementary Scheme 1, one AZ molecule was selected as the terminal group to initiate ring-opening bulk polymerization of one APC monomer containing one benzene ring (MBC), and then three AZ-APCs were successfully obtained (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Tables S1, Supplementary Fig. 1a).

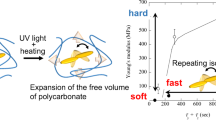

The obtained AZ-APC behaved as one elastomer at room temperature, since supramolecular non-covalent networks formed due to the unique properties of benzene rings, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1b32,33,34. When exposed to UV light, the condensed state of AZ-APCs changed greatly due to the transformation of trans-rich structures into cis-rich ones in the network, and the photoinduced cis-AZ-rich sample showed plastic, indicating the occurrence of photo-stimulable mechanical transformation (Fig. 1c). Interestingly, the cis-trans back isomerization of AZs was accelerated upon visible light or thermal radiation (the half-life of the cis-isomer is 16.9 h at room temperature, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2), which brought about mechanical changes of the AZ-APC from the rigid plastic in the cis-AZ-rich state to the soft elastomer in the trans-AZ-rich state, allowing further exploitation for flexible molding (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 3). The unusual mechanical transformation is contrary to the photo-triggered mechanics of other azopolymers1,36, which will be further explicated in the part of theoretical analysis. Besides, the molecular weight has a great influence on the performance of the AZ-APCs, especially their Tgs (Supplementary Fig. 4) and mechanical properties (Fig. 2). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 4, with increasing molecular weight, Tgs of both trans-AZ-rich and cis-AZ-rich polymers gradually increased. Since the Tg of homopolymer (PMBC) is −15 °C35, while the AZ-APC dramatically augments its Tg by the AZ-involved supramolecular interaction. The enhanced Tg values of AZ-APC can be attributed to several key factors. Firstly, AZ-capped APC forms supramolecular network elastomers that exhibit higher Tg compared to APC homopolymers. As the duration of the polymerization reaction increases, the benzene ring groups within the side chains of AZ-APC become enriched. Once the degree of polymerization reaches a certain threshold, the increased presence of these groups enhances spatial resistance within the polymer, thereby affecting molecular mobility and leading to an elevation in Tg. Secondly, the supramolecular crosslinked network structure formed by AZ-APC significantly contributes to the increase in Tg. This crosslinked network restricts molecular mobility, which consequently raises the Tg. Furthermore, regarding azo-polymer interactions, the cis-trans isomerization of AZ molecules within the polymer chains alters the distance and arrangement between the chains. This modification reinforces the interaction forces between the polymer chains, further restricting their movement and contributing to an increase in the Tg of the material. Finally, the Tg characterizes the temperature at which the movement of the chain segments begins, while the difference between trans and cis APC highlights the distinct natures of the supramolecular network. Although increasing the crosslink density generally raises the Tg of the polymer, it is evident that this increase in crosslink density does not lead to a decrease in chain-end motility. In cis APC, although the crosslink density increases, the impact of the increased crosslink density is somewhat offset by an increase in chain-end motility. Consequently, the Tg values of the APCs in the two states remain similar.

a and b are the storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) of trans-rich and cis-rich AZ-APCs vs. frequency at room temperature, respectively. c and d are the stress-strain curves of trans-rich and cis-rich AZ-APCs, respectively. The inset photos show that the strain of cis-rich AZ-APC is smaller than the trans-rich one under the same test conditions (length 12 mm, width 2 mm, thickness 1.5 mm, strain rate 0.33 s−1).

Photo-tunable mechanical transformation

Rheometry was adopted to characterize the photo-tunable mechanical behavior of AZ-APC at the 0.1% strain (Supplementary Fig. 5), and the frequency-dependent rheological behavior of trans-rich AZ-APC is shown in Fig. 2a. As the frequency increases, G″ is larger than G’, suggesting that AZ-APC displays viscous deformation over a wide range of frequency. After irradiation of UV light (an intensity of 176 mW/cm2 at 365 nm) for 30 min, the modulus of cis-Az-rich sample was 1.1–3.0 times stronger than that of trans-AZ-rich one in the whole range of frequency (Fig. 2b), demonstrating that the cis-rich AZ-APC exhibits a higher tightness and a higher viscosity at room temperature. Furthermore, with increasing the molecular weight, both G’ and G″ of trans-rich and cis-rich AZ-APCs were enhanced with the rising frequency. These may be attributed to that the AZ-APC network constructed by physical crosslinking is more sensitive to stress since the originally-established crosslinking point can be broken under an exerted small stress9,33,37,38. These demonstrate that the cis-rich AZ-APC can produce a stronger supramolecular interaction than the trans-rich one, resulting in an increased crosslinking density, bringing about a higher modulus.

We also investigated the temperature-dependent rheological behavior of AZ-APCs. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 6, both G′ and G″ gradually rose upon cooling AZ-APCs from 100 °C to −15 °C, and G′ tended to approach G″, illustrating the emergence of an elastic region at the temperature close to Tg of AZ-APCs. At 70–85 °C, G′ of both trans-AZ-rich and cis-AZ-rich samples were above 103 Pa in modulus values, while G″ of the two samples were higher than 103 Pa at about 100 °C. These demonstrate that both G′ and G″ need a higher temperature for chain segment movement since a higher crosslinking density of the network needs to overcome energy barriers from macromolecular chain movement25,26. On heating, a peak of tan δ appeared at around 7–9 °C for trans-AZ-rich sample, and around 9–11 °C for cis-AZ-rich one, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 7), which can be assigned to their Tgs, fitting well with the DSC results. At temperatures below Tgs of both cis-rich and trans-rich samples, G′ and G″ were strengthened progressively, and tan δ firstly decreased and then increased, exhibiting plastic and elastic, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2c,d, the stress of cis-rich AZ-APCs was always larger than trans-rich ones in their stress-strain curves, while the strain value of cis-rich AZ-APCs was always lower than trans-rich ones (Supplementary Table S2), which is in good agreement with the rheological evaluation. Therefore, the molecular changes of AZ isomerization can be greatly amplified by the supramolecular interaction of polymer, realizing the photo-tunable mechanics of AZ-APC matrices.

As shown in Supplementary Fig. 8, the relaxation time of the cis-rich AZ-APC was greater than that of the trans-rich AZ-APC, indicating that the entanglement of cis-rich polymer segments is stronger than trans-rich one. In addition, the modulus and tensile strength of the cis-rich AZ-APC are larger than those of the trans-rich one, which could be caused by the enhanced supramolecular interaction between the terminal cis-AZ groups and the benzene rings in the polymer side chain, allowing for an increase in the physical crosslinking density. As a result, the photoisomerization caused plasticity in the cis-rich AZ-APCs can be called “photoinduced network elastomers”.

Theoretical analysis of photo-tunable mechanical transformation

Generally, an elastomer with crosslinked network has entropy elasticity or energy elasticity, which can be studied by the Helmholtz free energy equation (detailed descriptions in the characterization part). Remarkably, when the stretch ratio is 200%, there is a highly linear fit between stress and temperature using the double partial derivative of the Helmholtz free energy concerning the temperature \({\left[\frac{{\partial }^{2}F}{\partial T\partial L}\right]}_{V}\) and strain\({\left[\frac{{\partial }^{2}F}{\partial L\partial T}\right]}_{V}\) through Flory composition (Fig. 3a). Then, the intercept of the straight line is energy contribution \(({\frac{\partial U}{\partial L}})_{T,{V}}\), and the slope is entropy contribution \(({\frac{\partial S}{\partial L}})_{T,{V}}\), indicating that the elasticity of the network structure is energy-driven rather than entropy-driven (the energy contribution >80%, Supplementary Fig. 9). Unlike other entropic elastomers, the network of AZ-APC elastomers is more likely affected by temperature since its majority network is constructed by supramolecular interactions. Moreover, APCs are usually thermosensitive39,40, and the energy stored by the physical crosslinking network is more easily released upon thermal treatment. Besides, the small contribution of entropy elasticity of AZ-APCs is attributed to their not high molecular-weights and small conformational changes. Consequently, AZ-APC elastomers can also be referred to as energy-driven elastomers, which generally have a higher modulus and a smaller reversible deformation41,42.

a Helmholtz free energy of energy-driven elastomers: Flory composition, the linear fitting of external force and temperature of P2 at a fixed stretching ratio of 200%. b Linear fitting of yield stresses as a function of the natural logarithm of strain rates (ε̇) for the trans-rich and the cis-rich AZ-APC (P2).

To provide a deeper understanding of the unusual photo-tunable mechanical behavior, the Erying model was introduced to describe the physically crosslinked network formed in the trans-rich and cis-rich AZ-APCs. The stress at different strain rates were characterized by using a stretching machine, showing that the motion of the segments and the whole macromolecular chain increased rapidly with increasing the stretching rate (Supplementary Fig. 10), leading to a decrease in the maximal strain and an elevation of yield stress. At the same test condition, the stress of the cis-rich AZ-APC was larger than the trans-rich one, which is consistent with the stress-strain curve. As shown in Fig. 3b, the relationship between the natural logarithm of the yield stress and the strain rate is close to linear for both trans-rich and cis-rich samples, following the Eyring model of force-induced physical crosslinking dissociation43,44,45. Furthermore, since AZ-APC is amorphous, the trans-rich and cis-rich samples fitted an activation volume of 0.28 nm3 and 0.44 nm3, respectively, confirming that the segment sizes of the amorphous matrix involved in the yield-related motions are reasonable. Then, the apparent activation energies were calculated to be 0.07 kJ mol-1 and 0.18 kJ mol-1 for trans-AZ and cis-AZ samples, respectively. Obviously, the energy barrier to overcome the segment motion in the cis-rich AZ-APC is larger than that in trans-rich one, and the binding energy of physical crosslinks constructed from cis-AZ-APC is larger than that of trans-AZ-APC. Consequently, the AZ-APC produces unusual mechanical transition upon photoisomerization, in agreement with the results of rheological and tensile test in Fig. 2, but in contrast to most of the reported azopolymers1,36.

Flory equilibrium solvation experiments were used to calculate the crosslinking density in the trans-rich and cis-rich AZ-APCs33,34. With increasing the molecular weight (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Table S3), the crosslinking density of the cis-rich AZ-APC was higher than trans-rich one, which is also consistent with the above-mentioned Erying model. Then, all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulation was used to further explain the tightness of the crosslinking network (detailed descriptions in the characterization part), as shown in Fig. 4b,c and Supplementary Fig. 1146. The simulation results demonstrate that the cis-rich AZ-APC possesses a high binding energy (−212.59 kcal/mol), compared to the trans-rich one (−198.67 kcal/mol), while the intramolecular crosslinking of the cis-rich sample possesses a smaller value (−174.61 kcal/mol) but still larger than that of the trans-rich one (−142.18 kcal/mol), suggesting that the cis-AZ has a greater influence on the physical crosslinking network in AZ-APCs. That is, intermolecular crosslinking formed in cis-rich AZ-APCs is more compact, compared to trans-rich ones, which is consistent with the results of apparent activation energy tests. To explore the influence of AZ ring interactions on the physical crosslink density in cis-polymers, we conducted a detailed analysis of the weak supramolecular interactions within the AZ-APC network. This analysis utilized the reduced density gradient (RDG) function and MD modeling. The RDG method allows us to thoroughly examine which weak supramolecular interactions contribute to the increase in physical crosslink density observed in cis-polymers. As shown in Fig. 4d, our analysis reveals that hydrogen bonding, π-π conjugation, and hydrophobic interactions within the cis-rich network significantly enhance crosslink density. This leads to stronger supramolecular interactions in the cis-rich network (−42.59 kcal/mol) compared to those in the trans-rich network (−41.74 kcal/mol). Additionally, to gain a deeper understanding of the increase in crosslink density within the cis-rich network, we investigated the number of hydrogen bonds between the two states using the MD model (Fig. 4e,f). Our findings indicate that the number of hydrogen bonds fluctuates over the simulation time, with the cis-system exhibiting a higher number of hydrogen bonds than the trans-system as a whole. Notably, the increase in hydrogen bonds in the cis-rich network primarily involves O…H and N…H interactions.

a The crosslinking density of the trans-rich and cis-rich AZ-APCs (empty for cis-rich, solid for trans-rich, distinct samples, mean ± s.d., n = 3). b, c IGM modeling of trans-and cis-rich AZ-APC: intra- and inter-macromolecular of hydrophobic interactions. d The reduced density gradient (RDG) function of AZ-APC: the blue portion is the H-bond, and the green portion is the π-π conjugation interactions formed between the benzene ring groups of the side chains of the AZ and APC polymers as well as the hydrophobic association interactions formed between the benzene ring groups of the side chains of the APC polymers. e, f MD modeling of hydrogen bond number of AZ-APC.

Therefore, the mechanism of photo-tunable mechanics of AZ-APC can be primarily explained by the above-mentioned physical models and theoretical calculations. The mechanical transformation of the plastic/elastic behavior is strongly governed by the supramolecular interactions photo-manipulated by the AZ isomerization and physical crosslinking, and three steps should be engaged basically. The first step is the photoisomerization of AZs in the terminated end of APCs under UV irradiation. The second step is the changes in the activation volume, physical crosslinking density, and binding energy that are simultaneously accompanied with the transformation from a trans-AZ-rich soft elastomer to a cis-AZ-rich hard plastic. The final step is the reversible change from cis-rich AZ-APCs to stable trans-rich samples by visible light radiation or thermal treatment, realizing the mechanical transformation from plastic to elastomer. Overall, from a polymeric perspective, a single-molecular photochemical transformation can significantly influence macroscale properties. A key consideration in the design of such materials is the introduction of supramolecular interactions that are sensitive to the polarity and motility of the chain ends. In this study, we utilized azobenzene, a photoresponsive moiety characterized by changes in its conjugated structure and polarity, and incorporated hydrophobic interactions alongside hydrogen bonding. This integration of molecular property changes with supramolecular interactions is regarded as a crucial aspect of material design.

Photo-switchable adhesives based on photoinduced mechanical properties

Investigation of the photo-tunable mechanical switching between plasticity and elasticity can address scientific challenges, such as smart switching of adhesive strength for low-adhesion polymers and handling of hard plastic polymers at room temperature without the use of plasticizers. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 12, one lap-joint shear strength test was used to evaluate the photo-switchable adhesive behavior to different substrates, like polycarbonate (PC), glass, iron (Fe), zirconium oxide (ZrO2), and pigskin. The AZ-APC samples were placed on the substrates followed by a 50 °C hot bench to firmly attach the two substrates and then shear force was applied to the substrates and pulled until fracture. Then, the adhesive strengths were obtained, ranging from 0.01 MPa for the pigskin to 1.5 MPa for the glass substrate. The PC adhesion strength was 4.57 MPa, which is amongst the strongest, much higher than that of the commercial ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA) polymer (0.53 MPa), suggesting a high degree of stability of the AZ-APC adhesives. The commercial PC and the present AZ-APC have a similar chemical structure, enabling the trans-rich AZ-APC to form a strengthened physical interlock at the interface.

After UV irradiation, the adhesive strength was dramatically enhanced from 0.22 MPa for pigskin to 4.93 MPa for glass substrate. The adhesion strength for PC was increased to 9.58 MPa, which is about 210% of the original one (Fig. 5a). Obviously, this photocontrollable adhesion is far different from other azopolymers36,47,48. Here, the cis-AZ-rich polymer shows a higher adhesive strength than the trans-rich one for different substrates, due to the combination effect of photoisomerization and physical crosslinking. After UV irradiation, the photoisomerization alters the supramolecular interactions in the AZ-APC, enabling the cis-rich polymer to have far different mechanical properties from trans-rich one, which is in agreement with the results of physical simulations, network cross-linking densities, and rheological tests. There was no detectable reduction in the adhesion strength even after several cycles of photoisomerization, exhibiting good reversibility (Supplementary Figs. 13,14).

a The stress values of universal bonding of trans-rich and cis-rich AZ-APCs to various substrates (distinct samples, mean ± s.d., n = 3). b Schematic illustration of dipole moments and electron cloud densities of the AZ-APC and the AZ initiator based on Gaussian theory. c Demonstration of the adhesive properties of AZ-APC adhesive by finger joints. d–f Biocompatibility and cellular safety: d Hemolysis rate test, hemolysis rate less than 5% could be used as a biomaterial. Three repeated measurements were made on different samples (distinct samples, mean ± s.d., n = 3). e, f The clonogenic ability of HUVEC cells after transfection, indicating that HUVEC cells cultured by the experimental group had strong proliferative vigor (the clonogenic test of the samples was repeated 3 times). g Representative photographs of wound healing under different treatments (control and experimental groups). h Typical wound closure rates for the treatment period. i Dimensional changes of wound healing of different treatment groups at different healing times.

As shown in Fig. 5b, the dipole moment (DM) of the AZ initiator and the AZ-APC were calculated by Gaussian theory simulations, respectively. After UV irradiation, DM of the cis-rich AZ-APC was 4.95, while the trans-rich sample was 0.82, suggesting that the cis-AZ has a higher polarity and a strong inhomogeneity of charge distribution in the polymer compared to its trans isomer. Consequently, a more polar cis-AZ sample can form a stronger interaction with different substrates49, for example, it will generate polar bonding, hydrogen bonding, etc., which in turn produces unexpected adhesion performance. In short, the anomalous results observed in the AZ-APC supramolecular network, in comparison to other azopolymers, can be explained as follows: Firstly, the AZ-APC supramolecular network contains a substantial number of bonding sites due to its physical cross-linked conformation during interactions with various substrates. Cis-rich APCs exhibit greater cross-linking strength compared to their trans-rich. Consequently, the increased availability of bonding sites in cis-rich APCs results in enhanced bonding strengths. This observation is supported by previous experimental findings, including rheological measurements, tensile testing, binding energy assessments, and apparent activation energy analyzes. Secondly, the dipole moments of

cis-rich AZ-APC were significantly larger than those of the trans-rich. This increased polarity facilitates stronger bonding interactions between cis-rich AZ-APC and various substrates, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 15. Importantly, the AZ-APC is hydrophobic (Supplementary Fig. 16), allowing adhesives to eliminate their inherent viscosity in a UV-/thermo-stretchable manner (Supplementary Movies S1, S2)50,51. The AZ-APC also exhibited excellent adhesion to human knuckles during motions (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Movie S3), demonstrating the universality of its adhesive properties.

Application of photo-tunable mechanical transformation

APC is a class of biocompatible and biodegradable materials8,39,40 and smart debonding can be implemented based on the present AZ-APCs by photoirradiation or thermal treatment, which may reduce the adhesive pain of patients when used as a medical smart dressing52. Upon wound healing, the healing material often requires mechanical switching to ensure the normal vital activity of the injured organism, which could be satisfied by using AZ-APCs with unparalleled advantages in smart bonding. Usually, natural compound glycyrrhizic acid (GA) and its derivatives have bioactivities, such as anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, anticancer, antiviral, etc53. The composition of AZ-APCs with GA has a significant potential to promote wound healing as advanced smart dressing.

Then, nanofiber dressings with multi-porosity and large specific surfaces were fabricated by electro-spinning (Supplementary Fig. 17), using a blend of one AZ-APC and GA (recorded as AZ-APC-GA, the experimental group). As shown in Fig. 5d–f and Supplementary Fig. 18, AZ-APC-GA had excellent biocompatibility and a good hemolysis rate, promising for biomaterials with biosafety. Utilizing the adhesive properties of AZ-APCs, rapid adhesion to wound surfaces was successfully obtained, solely relying on the mouse body temperature without applying an external stimulus (Supplementary Movie S4). As shown in Fig. 5d, on 10 and 15 days, the area of AZ-APC-GA treated wounds was significantly smaller than that of gauze and pristine AZ-APC treated wounds as control groups. Moreover, after 15 days, the wound contraction rate reached 100% in the AZ-APC-GA group, and it was 85.0% and 77.8% in the control groups, respectively (Fig. 5g–i). Afterward, the trauma covered by AZ-APC-GA nanofiber dressing had the smallest gap (Supplementary Fig. 19). More follicles and better connective tissue arrangement were formed, and the cells of the spinous cell layer were more neatly arranged and more tightly integrated with the granulation tissue under them. Then, inflammatory cells containing macrophages and neutrophils around the tissues were not observed at all, suggesting that AZ-APC-GA was more conducive to anti-inflammation. However, the healed epidermis of the control groups was not tightly combined with its underlying tissues, and obvious separations and inflammatory cells were observed. Furthermore, the Masson-stained images demonstrate that the AZ-APC-GA-covered wounds had uniformly organized collagen fibers like normal skin, whereas the collagen in the control groups was noticeably sparsely and disorganized deposited. Therefore, AZ-APC-GA has remarkable potential in promoting wound healing, anti-inflammation, and skin regeneration.

Discussion

In summary, energy-driven elastomers with photo-tunable mechanical transformation have been successfully obtained in AZ-APCs, which are terminated with one AZ derivative as the end group. Upon irradiation of UV light, AZ-APCs exhibited unusual mechanical changes from trans-AZ-rich soft elasticity to cis-AZ-rich plasticity, which is contrary to most of azopolymers. Removal of UV light, the AZ-APCs were switched to elasticity with the assistance of visible light irradiation or thermal treatment. This is complemented in the same ambient conditions thanks to the contribution of the reversible physical crosslinking network. Based on this unique feature, photo-switchable adhesion was acquired to various of commercial substrates. Among them, the PC substrates not only form reliable mechanical interfaces but also have similar compatible interactions with AZ-APCs, resulting in stronger adhesive strengths and a higher level of application in potential medical dressings. Although the present work has focused primarily on AZ-terminated polymer elastomers, we believe the proposed method can be extended to other elastomers with photoinduced mechanically switchable properties. The integration of photoisomerization units in elastomeric systems will help provide a approach to elegantly designing smart-responsive elastomers similar to biological systems that sense complex environments.

Methods

Materials

Benzyl chloride (99%) was obtained from Shanghai Chemical Reagent Factory (Shanghai, China). 2,2-Bis(hydroxymethyl)propionic acid (99%) was bought from Tianjin Bodi Chemical Co. (Tianjin, China). Triethylamine (99%) was purchased from Tianjin Damao Chemical Reagent Factory (Tianjin, China). Triethylamine (99%) was purchased from Tianjin Damao Chemical Reagent Factory (Tianjin, China). The p-n-butylaniline, sodium nitrite and phenol were purchased from Peking University Chemical Reagent Library. Stannous octanoate [Sn(Oct)2] (99%) was purchased from SigmaAldrich. ethyl chloroformate (99%) was purchased from Xinyi City Huili Fine Chemical Co. (Xinyi, China) was purchased. Toluene (99%) was dried by Na treatment and distilled before use.

Animal

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the animal management regulations of the Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China and approved by the animal care organization. Furthermore, the experimental protocol was approved by the Laboratory Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of the Institute of Zoology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and was conducted in accordance with the Guidelines for Ethical Review of Animal Welfare of Laboratory Animals in China (GB/T 35892-2018) (Ethics Committee/IACUC Approval No.: IOZ-IACUC-2023-170). C57BL/6 J mice (female, 6–8 weeks) were purchased from Beijing Weitong Lihua Experimental Animal Technology Co., Ltd., (Beijing, China).

Preparation of AZ-APCs

In this study, one AZ compound was used to initiate the ring-opening polymerization of the monomer (MBC) containing one benzene ring, as shown in Figure S1. MBC as a hydrophobic monomer, and Sn(Oct)2 as the catalyst, and the synthetic ratios were given in Table S1. The reaction was performed as follows: one mixture of AZ and MBC was thoroughly mixed and placed in a dry silanized glass ampoule. The ampoule is vacated, purged three times with nitrogen and sealed, then immersed in an oil bath preheated to 85 °C for 30 h. The product was dissolved in dichloromethane and then precipitated in methanol (repeated three times). Finally, the product was dried for four days in a vacuum oven to a constant weight.

The formating of AZ-APC supramolecular network

Azobenzene (AZ) small molecules served as the initiator, while stannous octanoate acted as the catalyst to initiate the ring-opening polymerization of the aliphatic polycarbonate monomer MBC. MBC was selected as the polymerization monomer because it can function as a rigid chain segment and contains both an ester carbonyl group and a benzene ring. The sp² hybridized oxygen atom in the carbonyl group of MBC is highly electronegative, enhancing MBC’s ability to attract lone electron pairs during the polymerization process. This allows MBC to act as a proton acceptor, forming hydrogen bonds with donors. The free benzene ring groups in the polycarbonate chain segments exhibit high chemical reactivity, enabling the formation of hydrophobic associative interactions. Meanwhile, the change in polarity and kinematics of the chain ends fundamentally changes the nature of the overall network (topological and elastic contributions). These groups also engage in π-π conjugate interactions with the initiator AZ. As a result, the polycarbonate can form a supramolecular AZ-APC network after the polymerization reaction by controlling the reaction conditions, utilizing multiple non-covalent bonding interactions as cross-linking sites.

Furthermore, the mechanism of the supramolecular network polymerization reaction can be outlined as follows: during the AZ-initiated MBC ring-opening polymerization, protons from AZ migrate to the alcohol salt ligand through the coordination process, leading to the formation of hydrogen bonds between AZ and the alcohol salt ligand. Subsequently, a weak complex is formed between MBC and the ligand, facilitating the transfer of the alcohol ligand into the MBC structure. This transfer and embedding process involves two key steps: first, the MBC is attacked by the nucleophile from the alcohol salt, and second, MBC undergoes ring-opening polymerization. During this polymerization process, the number of ester carbonyls and free benzene ring groups on the polymer chain segments increases. Hydrogen bonding occurs between the ester carbonyls and hydroxyl groups, while hydrophobic associative interactions and π-π conjugation interactions form between the benzene ring groups of the polymer side chains and the terminal AZs. This leads to lateral stacking of the cross-linking sites, ultimately resulting in the bundling of these stacks into supramolecular networks.

Preparation of cis-azobenzene AZ-APC half-life test samples

Firstly, the solution made of AZ-APC was rotationally coated on a quartz substrate. Then UV illumination was given for 10 min to obtain a cis-rich film. Finally, the half-life of the cis-isomer was obtained using the time-dependent UV-vis absorption spectrum of this cis-rich film.

Characterizations

Chemical structure and thermal behavior

The molecular weight and chemical structure of the AZ-APC were characterized by gel permeation chromatography (GPC, Waters 1515) with a multi-angle light-scattering detector, and 400 MHz WB Solid-State NMR Spectrometer (H NMR, AVANCE III, Bruker). Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements were made using a NETZSCH DSC-204 thermal analyzer (Netzsch, Hanau, Germany) with a temperature range of −40 °C to 100 °C and a measurement rate of 10 °C/min under a flowing nitrogen atmosphere. UV absorption spectra have been recorded on a Lambda 750 spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer; Boston, USA), which was used to test the half-life of AZ-APC.

Mechanical properties

Rheological behavior: Anton paar rheometer (MCR301) was used to test the rheological behavior of hydrogels with a fixed strain of 0.1% and to test the changes in energy storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) at a variable frequency (range: 0.01–100 Hz) and a variable temperature (range: −15–100 oC). All tests were conducted on a universal tensile machine (Instron, USA) with a 1000 N load cell. Unless otherwise stated, all tests in the tensile strength study were performed at a constant speed of 20 mm/min at room temperature with at least five parallel samples recorded for each sample.

Helmholtz free energy

The constant capacitance free energy is used to evaluate the attribution of elasticity of materials, and elastomer elasticity is categorized into energetic and entropic elasticity44,54. Stretching an elastomer of original length L0 by dL at constant temperature, the change in internal energy of the material comes from three main sources: firstly, the material absorbs the tensile work fdL during the stretching process; secondly, the work of volume change (work done by the material on the environment) PdV; and thirdly, the change in heat in the process of pulling TdS. If the volume is constant, the derivation is carried out by using the Helmholtz free energy. Its derivation is as follows:

Taking partial derivation of T and L, respectively.

Here, U is the internal energy, S is the entropy of the material, f and F are the externally applied forces, T and V are the ambient temperature and the material volume, respectively.

Calculation of activation volume and energy

The activation volume and energy were determined by the Eyring model43,44,45.

where Va is the activation volume, with Ea being the activation energy, \({\varepsilon }^{.}\) the strain rate, and σy the yield stress.

Flory-Rehner equation

The cross-linking density is determined by the well-known Flory-Rehner formula according to equilibrium swelling experiments in ether. Pre-weighed, dried AZ-APCs were dissolved in ether at room temperature for 72 h, with a new solvent every 24 h. The samples were instantly weighed and then dried in a vacuum oven at 25 °C until constant weight. Three specimens were measured for each sample.

The cross-linking density of gel was calculated by the Flory–Rehner equation33:

where Ve is the crosslinking density of the material and χ is the Flory–Huggins polymer-solvent interaction parameter. (0.722 for aliphatic polycarbonate and ether). Vr is the volume fraction of the material in ether:

Where md is the sample mass before swelling, and ms is the sample weight at equilibrium swelling. ρs and ρp are the densities of the solvent and elastomer, respectively.

Swelling rate

The swelling rate of AZ-APCs in aqueous solvents in the pH range of 3–12 was employed to examine the resistance of AZ-APC to anti-corrosion. The formula for calculating the SR of AZ-APCs is as follows34:

where Ws is the equilibrium swelling mass of the AZ-APC and Wd is the initial weight of the AZ-APC.

All-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulation

To study the hydrophobic association interactions in polymers, the IGM was used to investigate the hydrophobic association interactions within a polymer and between two polymers46,55. The range of color scale axis sign (λ2) ρ of IGM isosurface is generally set to [−0.04, +0.02]. The scale axis is a color scale displayed from blue to green, and then to red with different colors on the scale axis corresponding to different types of weak supramolecular interactions. The hydrophobic association interaction is mainly green.

Adhesion procedure of P3

To produce adhesion of AZ-APCs, 10 mg of P3 elastomer was placed on a substrate with an area of 2.5 cm × 5 cm. The P3 was directly UV light irradiated or heat treated to form a uniform liquid layer. Another substrate was then placed on top of the liquid layer. A pressure was then applied to the substrate before the P3 returned to the solid state. The adhered substrates were stored at room temperature for 24 h for further testing. Then, shear forces were applied to the substrate on the universal testing machine and pulled until failure.

All the participants of the study gave written informed consent for the publication of the images and data. The authors affirm that human research participants provided written informed consent for publication of the images in Fig. 5c and Supplementary Movie S3.

Biological recognition

In vitro cell compatibility test. Cell counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) and clone formation assays were used to assess the effect of the AZ-APCs on cell viability. Cytocompatibility testing of the AZ-APCs was performed in vitro8. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were used for cell culture experiments, which were purchased from the Cell Bank of the Type Culture Collection Committee of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). HUVEC cells were first digested, then centrifuged and counted. HUVEC cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (Gibco) containing 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (Gibco) and 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) at an incubator temperature of 37 °C/5% CO2. Special note: All elastomers were sterilized with 75% ethanol overnight and then treated with phosphate buffer solution (PBS) wash. Afterward, HUVEC were digested and centrifuged, resuspended with medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, and counted. The concentration was adjusted to 6 × 104/mL, inoculated in 96-well plates, and 100 μL of cell suspension was added to each well and co-cultured with the material mixture. Then, after 24 h of incubation, 10 μL of CCK-8 was added to the wells, and CCK-8 incubation was ended at the end of 2 h. The well plates were placed in the zymography (Biochrom, Anthos 2010, Germany), and the OD450 was measured, and the determination was made once every 24 h.

Clone-forming experiments

HUVEC cells in the logarithmic growth phase were centrifuged, and counted. The cells were then inoculated into a 6-well plate at 2000 cells/well and cross-hatched so that the cells were evenly dispersed in the plate. The cells were placed in the incubator for regular observation. After 5–7 days, the culture was terminated by removing the well plates when visible colonies were detected. After carefully removing the culture medium, the culture medium was rinsed with PBS for 3 times. Then, add Coomassie Brilliant Blue Staining Fixative and stain for 10 min at room temperature. Cell clone formation was observed using an inverted phase contrast microscope (DMIL-PH1, Leica, Germany).

Transwell experiment to detect cell migration ability

HUVEC were digested and centrifuged, resuspended and counted with a medium containing 10% without fetal bovine serum, and the concentration was adjusted to 5 × 105 cells/mL. A 24-well plate was taken, and 600 μL of 10% fetal bovine serum-containing medium was added in the empty space to co-cultivate with the material mixture. The 100 μL of the Cell suspension was added to the upper layer of the chamber. After 24 h, the chamber was taken out, and the top of the chamber was wiped with a cotton swab. Fixed staining was carried out with Caumas Brilliant Blue, and the chamber was air-dried and photographed.

Blood Compatibility

The erythrocyte compatibility of the AZ-APCs can be studied by the hemolysis test56. Fresh blood (2 mL) was placed into an anticoagulant heparin-pretreated blood collection tube and centrifuged (10,000 rpm, 5 min × 3–4 times) with a homogeneous mixture of Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (D-PBS, 4 mL). Subsequently, when the supernatant was clear, fresh D-PBS was added to resuspend the red blood cells. Then, six new EP tubes were added, and 0.2 mL of erythrocyte solution and AZ-PC-elastomer were mixed for 30 min at 37 °C. Deionized water (DW) served as the positive control, and D-PBS served as the negative control.

The calculation formula for the hemolysis rate: Hemolysis ratio (%) = (Absorbance of sample-Absorbance of control)/Absorbance of DW × 100%56.

A statement of informed consent from the participant: Participant was informed and consented to the hemolysis experiment. The blood samples were obtained after receiving written informed consent from the patients, who did not receive compensation. All the procedures were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Reproductive Hospital of China Medical University according to ethical guidelines (Approved 2023-AE-36).

In vivo studies

Firstly, 6–8 weeks C57BL/6 J mice were acclimatized for one week57. Rearing conditions of 6-8 weeks C57BL/6 J mice: mice live in a dimly lit environment with room temperature and humidity of 55%. The light intensity in the rearing room should be controlled at 15–20 lx, and a 12-hour/14-hour light cycle alternating light and dark should be used to simulate the natural environment and to maintain the biorhythms of the mice. Then, the mice were placed in the induction box of the anesthesia machine for isoflurane gas anesthesia. When the mice had no behavioral activity were removed from the induction box and placed on the operating table of the biosafety cabinet, and the inhalation anesthesia was continued by placing their faces against the respirator mask. After the mice were unresponsive to external stimuli, the surgical operation was started. After that, the backs of the mice were shaved and prepared for skin preparation, and the skin surface was first disinfected with a cotton swab dipped in 75% alcohol, and then the epidermis was disinfected with a cotton swab dipped in iodophor. The skin tissue on the back of the mice was cut off with a scalpel in a rectangular shape (area of about 1 cm × 1 cm). Next, the mouse skin wound size was measured with a steel ruler and recorded. Finally, a wound patch of appropriate wound size was applied to the mouse skin wound, and its wound healing was observed on Day 1, Day 3, Day 5, Day 10, and Day 15, respectively (wound measurements were taken, and photographs were taken to record the wound changes).

Note

Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the committee of the institute of animal research, Chinese academy of sciences. Meanwhile, all surgical instruments and consumables involved in the experiments were sterilized/disinfected in the barrier facility in advance and put into the biosafety cabinet to be sterilized again by UV irradiation before the start of the experiments. Secondly, mice were targeted with insulin for intramuscular injection of meloxicam 10 μL/10 g for analgesia (3 consecutive days).

DFT Calculations

The geometries of the molecular systems were optimized using Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations. All computational procedures were executed using the Gaussian 16 software package58, which incorporates mixed B3LYP functional methodologies59. For the basis set, we employed the 6-31 G* configuration for all elements to ensure a balanced trade-off between computational efficiency and accuracy. To further enhance the precision of our calculations, Grimme’s D3BJ dispersion correction60 was implemented, allowing for a more accurate representation of non-covalent interactions. The analysis of the reduced density gradient (RDG) was performed using Multiwfn 3.8_dev61, which enabled a detailed examination of the electronic density characteristics. The visualization of these analyzes was carried out with VMD 1.9.362, facilitating an intuitive interpretation of the results and providing insights into the molecular interactions involved.

Computational Details

Molecular dynamics simulations were conducted using the Gromacs 2021.6 software package63. For all molecular systems, we employed the General Amber Force Field (GAFF) parameters64 in conjunction with RESP charges65 to accurately model the molecular interactions. Each simulation system began with the construction of an initial simulation box containing 100 Cis or Trans molecules. Prior to the production runs, energy minimization was performed using the steepest descent algorithm with a termination gradient set at 500 kJ·nm·mol-¹. Following energy minimization, a 50 ns NPT (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) simulation was executed at 298 K. Temperature and pressure were regulated using a V-rescale thermostat and a Parrinello–Rahman barostat, respectively. To accurately model the system, a cut-off distance of 1.5 nm was applied, while long-range electrostatic interactions were calculated using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method. Non-bonding interactions were assessed using Lennard-Jones potentials. The time step for all simulations was set to 1 fs to ensure sufficient temporal resolution. The visualization of molecular structures and simulation results was performed using VMD software, allowing for detailed analysis and interpretation of the molecular dynamics trajectories.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary information files. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Zhang, Z., Xie, Z., Nie, C. & Wu, S. Photo-controlled properties and functions of azobenzene-terminated polymers. Polymer 256, 125166 (2022).

Zhou, H. et al. Photoswitching of glass transition temperatures of azobenzene-containing polymers induces reversible solid-to-liquid transitions. Nat. Chem. 9, 145–151 (2017).

Pang, X., Lv, J., Yu, Y. L., Qin, Y. & Yu, Y. L. Photodeformable azobenzene‐containing liquid crystal polymers and soft actuators. Adv. Mater. 31, 1904224 (2019).

Pang, X. L., Qin, L., Xu, B., Liu, Q. & Yu, Y. L. Ultralarge contraction directed by light‐driven unlocking of prestored strain energy in linear liquid crystal polymer fibers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2002451 (2020).

Xu, Y. et al. In situ light‐writable orientation control in liquid crystal elastomer film enabled by chalcones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202319698 (2024).

Yang, B., Cai, F., Huang, S. & Yu, H. F. Athermal and soft multi‐nanopatterning of azopolymers: phototunable mechanical properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 132, 4064–4071 (2020).

Ren, H., Yang, P. & Yu, H. F. Recent progress in zzopyridine-containing supramolecular assembly: From photoresponsive liquid crystals to light-driven devices. Molecules 27, 3977 (2022).

Chen, C. X., Hou, Z., Yang, L. Q. & Hu, J. S. Photothermally responsive smart elastomer composites based on aliphatic polycarbonate backbone for biomedical applications. Compos. Part. B-Eng. 240, 109985 (2022).

Cai, F., Yang, B., Lv, X., Feng, W. & Yu, H. F. Mechanically mutable polymer enabled by light. Sci. Adv. 8, eabo1626 (2022).

Guo, H., Han, Y., Zhao, W., Yang, J. & Zhang, L. Universally autonomous self-healing elastomer with high stretchability. Nat. Commun. 11, 2037 (2020).

Alapan, Y., Karacakol, A. C., Guzelhan, S. N., Isik, I. & Sitti, M. Reprogrammable shape morphing of magnetic soft machines. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc6414 (2020).

Hayashi, M., Matsushima, S., Noro, A. & Matsushita, Y. Mechanical property enhancement of ABA block copolymer-based elastomers by incorporating transient cross-links into soft middle block. Macromolecules 48, 421–431 (2015).

Colquhoun, H. M. Materials that heal themselves. Nat. Chem. 4, 435–436 (2012).

Yang, Y. & Urban, M. W. Self-healing polymeric materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 7446–7467 (2013).

Lv, X., Wang, W., Clancy, A. J. & Yu, H. High-speed, heavy-load, and direction-controllable photothermal pneumatic floating robot. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 13, 23030–23037 (2021).

Cai, F., Zheng, F., Lu, X. & Lu, Q. Control of the alignment of liquid crystal molecules on a sequence-polymerized film by surface migration and polarized light irradiation. Polym. Chem. 8, 7316–7324 (2017).

Bisoyi, H. K. & Li, Q. Light-driven liquid crystalline materials: from photo-induced phase transitions and property modulations to applications. Chem. Rev. 116, 15089–15166 (2016).

Huang, X. et. al. Multiple shape manipulation of liquid crystal polymers containing diels‐alder network. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2208312 (2022).

Mu, W. et al. Membrane-confined liquid-liquid phase separation toward artificial organelles. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf9000 (2021).

Weis, P., Tian, W. & Wu, S. Photoinduced liquefaction of azobenzene‐containing polymers. Chem. A. Eur. J. 24, 6494–6505 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Fabrication of anticounterfeiting nanocomposites with multiple security features via integration of a photoresponsive polymer and upconverting nanoparticles. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2103908 (2021).

Xu, W. C., Sun, S. & Wu, S. Photoinduced reversible solid‐to‐liquid transitions for photoswitchable materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 9712–9740 (2019).

Ji, Y. F., Song, T. F. & Yu, H. F. Assembly-induced dynamic structural color in a host-guest system for time-dependent anticounterfeiting and double-lock encryption. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 136, e202401208 (2024).

Du, Z. et al. Aggregation and rheology of an azobenzene-functionalized hydrophobically modified ethoxylated urethane in aqueous solution. Macromolecules 49, 4978–4988 (2016).

Yang, R., Peng, S., Wan, W. & Hughes, T. C. Azobenzene based multistimuli responsive supramolecular hydrogels. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2, 9122–9131 (2014).

Jochum, F. D., Borg, L., Roth, P. J. & Theato, P. Thermo-and light-responsive polymers containing photoswitchable azobenzene end groups. Macromolecules 42, 7854–7862 (2009).

Wang, H. Q. et al. A dual‐responsive liquid crystal elastomer for multi‐level encryption and transient information display. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 135, e202313728 (2023).

Guo, Y. et al. Photoswitching of the melting point of a semicrystalline polymer by the azobenzene terminal group for a reversible solid-to-liquid transition. J. Mater. Chem. A. 9, 9364–9370 (2021).

Lee, C. et al. Fast photoswitchable order-disorder transitions in liquid-crystalline block co-oligomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 390–399 (2022).

Zha, R. H. et al. Photoswitchable nanomaterials based on hierarchically organized siloxane oligomers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1703952 (2018).

Jang, J., Oh, J. H. & Moon, S. I. Crystallization behavior of poly(ethylene terephthalate) blended with hyperbranched polymers: The effect of terminal groups and composition of hyperbranched polymers. Macromolecules 33, 1864–1870 (2000).

Sun, S. Q., Chen, C. X., Zhang, J. H. & Hu, J. S. Biodegradable smart materials with self-healing and shape memory function for wound healing. Rsc. Adv. 13, 3155–3163 (2023).

Chen, C. X., Guo, Z. H., Chen, S. W., Hu, J. S. & Yang, L. Q. Highly efficient self-healing material with excellent shape memory and unprecedented mechanical properties. J. Mater. Chem. A. 8, 16203–16211 (2020).

Chen, C. X., Duan, N., Chen, S. W., Hu, J. S. & Yang, L. Q. Synthesis mechanical properties and self-healing behavior of aliphatic polycarbonate hydrogels based on cooperation hydrogen bonds. J. Mol. Liq. 319, 114134 (2020).

Liu, X. F., Guo, Z. H., Xie, Y., Chen, Z. P. & Hu, J. S. Synthesis and liquid crystal behavior of new side chain aliphatic polycarbonates based on cholesterol. J. Mol. Liq. 259, 350–358 (2018).

Li, J., Zhang, Q, Y. & Lu, X. B. Azopolyesters with intrinsic crystallinity and photoswitchable reversible solid-to-liquid transitions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 135, e202311158 (2023).

Wei, Z. et al. Self-healing gels based on constitutional dynamic chemistry and their potential applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 8114–8131 (2014).

Zhang, H., Xia, H. & Zhao, Y. Poly (vinyl alcohol) hydrogel can autonomously self-heal. Acs. Macro. Lett. 1, 1233–1236 (2012).

Xu, J., Feng, E. & Song, J. Renaissance of aliphatic polycarbonates: new techniques and biomedical applications. Appl. Polym. Sci. 131, 39822 (2014).

Yu, W., Maynard, E., Chiaradia, V. & Arno, M. C. Aliphatic polycarbonates from cyclic carbonate monomers and their application as biomaterials. Chem. Rev. 121, 10865–10907 (2021).

Kofod, G., Wirges, W., Paajanen, M. & Bauer, S. Energy minimization for self-organized structure formation and actuation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 081916 (2007).

Chris, C., Hornat, M. & Urban, W. Entropy and interfacial energy driven self- healable polymers. Nat. Commun. 11, 1028 (2020).

Chen, X. et al. A thermally re-mendable cross-linked polymeric material. Science 295, 1698–1702 (2002).

Bilici, C., Ide, S. & Okay, O. Yielding behavior of tough semicrystalline hydrogels. Macromolecules 50, 3647–3654 (2017).

Shi, Y., Wu, B., Sun, S. & Wu, P. Aqueous spinning of robust, self-healable, and crack-resistant hydrogel microfibers enabled by hydrogen bond nanoconfinement. Nat. Commun. 14, 1370 (2023).

Chakraborty, T., Hens, A., Kulashrestha, S., Murmu, N. C. & Banerjee, P. Calculation of diffusion coefficient of long chain molecules using molecular dynamics. Phys. E. 69, 371–377 (2015).

Zhang, Z. et al. Long alkyl side chains simultaneously improve mechanical robustness and healing ability of a photoswitchable polymer. Macromolecules 53, 8562–8569 (2020).

Zhou, Y. et al. Light-switchable polymer adhesive based on photoinduced reversible solid-to-liquid transitions. Acs. Macro. Lett. 8, 968–972 (2019).

Fridgen, T. D. Structures of heterogeneous proton-bond dimers with a high dipole moment monomer: covalent vs electrostatic interactions. J. Phys. Chem. A. 110, 6122–6128 (2006).

Narayanan, A. et al. Viscosity attunes the adhesion of bioinspired low modulus polyester adhesive sealants to wet tissues. Biomacromolecules 20, 2577–2586 (2019).

Heinzmann, C. et al. Supramolecular polymer adhesives: advanced materials inspired by nature. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 342–358 (2016).

Chen, K. et al. A conformable and tough janus adhesive patch with limited 1D swelling behavior for internal bioadhesion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 20, 2303836 (2023).

Zhao, Z. et al. Glycyrrhizic acid nanoparticles as antiviral and anti-inflammatory agents for COVID-19 treatment. Acs. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 13, 20995–21006 (2021).

Zhu, W. & Shelley, M. Modeling and simulation of liquid-crystal elastomers. Phys. Rev. E. 83, 051703 (2011).

Lu, T. & Chen, Q. Independent gradient model based on Hirshfeld partition: a new method for visual study of interactions in chemical systems. J. Comput. Chem. 43, 539–555 (2022).

Zhou, L. P. et al. Multifunctional DNA hydrogel enhances stemness of adipose‐derived stem cells to activate immune pathways for guidance burn wound regeneration. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2207466 (2022).

Biswas, A., Singh, A. P., Rana, D., Aswal, V. K. & Maiti, P. Biodegradable toughened nanohybrid shape memory polymer for smart biomedical applications. Nanoscale 10, 9917–9934 (2018).

Frisch, M. J., Trucks, G. W., Fox, D. J., Gaussian 16, Revision A.03: Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2016.

Jean‐ Louis, C. Density‐functional theory of atoms and molecules. Int. J. Quantum. Chem. 47, 101 (1993).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011).

Contreras-García, J. & Yang, W. Analysis of hydrogen-bond interaction potentials from the electron density: integration of noncovalent interaction regions. J. Phys. Chem. A. 115, 12983–12990 (2011).

Humphrey, W. & Dalke, A. K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Molecular. Graphics. 14, 33–38 (1996).

Lindahl, E. et al. GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1701–1718 (2005).

Wang, J., Wang, W., Kollman, P. A. & Case, D. A. Automatic atom type and bond type perception in molecular mechanical calculations. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 25, 247–260 (2006).

Cieplak, P., Cornell, W. D., Bayly, C. & Kollman, P. A. Application of the multimolecule and multiconformational RESP methodology to biopolymers: Charge derivation for DNA, RNA, and proteins. J. Comput. Chem. 16, 1357–1377 (1995).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (H.F.Y: Grant No.s, 52173066, 51921002 and T.F.S: 52303021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.X.C., T.F.S. and H.F.Y. have conceptualized and designed the study. C.X.C. fabricated AZ, MBC, and AZ-APCs. C.X.C. and T.F.S. characterized the rheological properties. C.X.C. and Y.F.J. have performed AFM work. C.X.C. prepared AZ-APC-GA composite. C.X.C. and H.M.L. performed Gaussian simulation calculations. C.X.C. characterized chemical structure, thermal behavior, mechanical strength, and self-healing behavior tests. C.X.C. and T.F.S. fabricated and characterized the different substrate bonds. C.X.C. and Y.F.J. performed equipment photography and videography work. C.X.C., T.F.S., and H.F.Y. prepared the manuscript based on input from all authors. H.F.Y. supervised the research.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, C., Ji, Y., Li, H. et al. Unusual photo-tunable mechanical transformation of azobenzene terminated aliphatic polycarbonate. Nat Commun 16, 2620 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57608-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57608-w