Abstract

An intact oxide scale adhering well to the matrix is crucial for the safe service of metallic materials at high temperatures. However, premature failure is usually caused by spallation of scales from the matrix. Although few mechanisms have been proposed to understand this phenomenon, consensus has not yet been reached. In this study, we reveal that trace sulfur impurities contaminated in high-purity raw materials prominently segregate to the interface and form a thin intermediate amorphous-like layer between the oxide scale and alloy matrix during the oxidation process. Subsequently, cracking and spallation occur preferentially between the sulfur-rich layer and alumina scale due to the weak bonding between sulfur and alumina atoms. We validate the revealed atomistic spalling mechanism by successfully eliminating the detrimental effect of sulfur via microalloying. Our findings are useful for improving adhesion of oxide scales and enhancing heat-resistant properties of other high-temperature alloys.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heat-resistant alloys are key materials widely applied in the field of transportation, aerospace, petroleum industry and energy generation1. Particularly, with the flourishing development of energy storage and electric vehicle, new requirements have been put forward for heat-resistant alloys as balance of plant components, which encounter severe challenge in high-temperature oxidation and corrosion under complex environments2,3,4. The corrosion resistance of these heat-resistant materials, which relies on the formation and retention of contact yet adherent oxide scales to protect the metal matrix from corrosive atmospheres, plays a pivotal role during operation5. However, because of differences in physical properties between the oxide scale and the metal matrix (i.e., coefficient of thermal expansion), the oxide scale is prone to cracking or spalling during the growth process and thermal cycling, leading to premature catastrophic failure6,7. Serious efforts were devoted to elucidating the origins of the high-cracking tendency, nevertheless, no consensus has been reached yet.

The segregation phenomenon of indigenous sulfur impurity from raw materials at the oxide-matrix interface during oxidation is one of prevailing mechanisms for explaining the spalling of the oxide scale8,9. In the mid-1980s, Smeggil et al. discovered significant sulfur segregation (over 20 at. %) on the free surface of NiCrAl alloy which contained only about 50 ppmw of inherent sulfur impurities10. Then the “sulfur effect” was proposed by Hou et al., who assumed that the scale-metal interfaces are intrinsically strong, but impurity sulfur segregated at oxide-matrix weakens the bonding and causes the scale to be nonadherent11,12,13. Smialek confirmed this proposal by demonstrating that removing sulfur from the alloy, typically through high-temperature H2-annealing, can significantly improve the spallation resistance of the oxide scale during cyclic oxidation processes14,15. While the presence of sulfur near the oxide-alloy interface has been identified through techniques such as Auger electron spectroscopy (AES), there is still no direct evidence to ascertain whether a ppm-level amount of sulfur can segregate along the interface, and how it segregates and deteriorates the adhesion at atomic scale, primarily due to the lack of clear observation and quantitative analysis of atomic configuration of S.

In this study, we used the atomic level characterization techniques to solve the aforementioned questions and challenges. The integrated differential phase contrast (iDPC) signal of spherical aberrations-corrected scanning transmission electron microscopy (AC-STEM) is facilitates the resolution of lightweight atoms, whilst three-dimension atom probe tomography (3D-AP) is feasible and precise for quantitative analysis of segregation atoms at the interface16,17. A typical alumina-forming austenitic (AFA) steel prepared with high-purity raw materials was selected as the model material, and the deterioration effect of indigenous sulfur on the adhesion of oxide scales during the oxidation process was re-evaluated18. By atomic-scale analysis (i.e., iDPC and 3D-AP) combination, we clearly verified the sulfur effect and investigated the amorphous-like sulfur-rich layer at the oxide-matrix interface, then experimentally guided simulations were performed based on the probed segregation configurations to uncover atomistic mechanism of decohesion.

Results

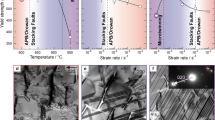

Spallation and sulfur segregation behavior in high-purity AFA steels

AFA specimens were heat-treated in a humid air atmosphere at 900 °C for 100 h, and morphology of the spontaneously grown oxide scale is shown in Fig. 1. The top-view morphology (i.e., Fig. 1a) clearly shows spalling and cracking occurred on the surface of the specimen, suggesting poor adhesion of the oxide scale. The red dashed lines indicate the areas where the matrix is exposed due to the spalling of the scale, and some detached locations can be clearly observed adjacent to these areas. The high-magnification image in Fig. 1b shows the coexistence of areas still covered by oxides and areas underlying extensive spalling. A fresh matrix surface without any protecting scale can be probed on the left of the image and some cracks present within the adjacent scale, indicating that the scale has lost its protection. In order to further uncover the origin of the scale spallation, TEM investigation was conducted for the white-boxed region. The alloy matrix, oxide scale and deposited Pt protective layer are shown in Fig. 1c. The oxide scale has a thickness of about 500 nm and is mainly composed of columnar crystals that exhibit light contrast in the bright field (BF) image. A long yet continuous crack along the interface between the scale and matrix was observed, evidencing that the spalling occurred preferentially along the oxide-matrix interface.

Figure 1d shows the enlarged HAADF-STEM image of the oxide-matrix interface region, where two flat phase boundaries were examined. One interface is still connected with the matrix (red dashed line) while cracks have already initiated on the other interface (blue dashed line). The EDS mapping results indicate that the main components of the oxide scale are Al and O elements. The fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the selected atomic image reveals that the crystal structure of the scale is α-Al2O3, which was taken from the \([2\bar{1}\bar{1}0]\) direction (Fig. 1e). Since there are no detectable specific orientation relationships between the α-Al2O3 grains and austenite matrix, it is difficult to detect the lattice fringes of the matrix as well. Particularly notable is the detection of a sulfur-rich layer with a relatively high concentration at the oxide-matrix interface, as shown by the EDS mapping around the interface (Fig. 1f). This observation directly confirms the segregation of sulfur along the interface, which has been frequently proposed as the origin of interface decohesion in previous studies.

Atomic configuration of sulfur at the interface between oxide and matrix

To elucidate the interface segregation configuration of sulfur (only 26 ppmw in the matrix) and its role in decohesion, atomic-resolution STEM and 3D-AP techniques were employed. Figure 2a, b shows HAADF and iDPC images recorded concurrently from the \([10\bar{1}0]\) direction of Al2O3. The HAADF image (Fig. 2a) only presents the sublattice occupied by Al in the outer scale layer, whilst the iDPC image (Fig. 2b) also illustrates the sublattice occupied by oxygen atoms. Compared with the outer α-alumina layer, the periodic lattice structure between the scale and matrix becomes relatively disordered (highlighted by two blue dash lines). The corresponding EDS mapping and line scanning results in Fig. 2c, d demonstrated that this amorphous-like layer corresponds well to the S-rich layer. In addition, the morphology of sulfur-rich layer within differently oriented samples were further checked. As shown in supplementary Fig. 1, an S-rich amorphous-like layer was consistently observed regardless of the orientation and terminating plane of the adjacent grains, and their average thickness was determined to be about 632 ± 26 pm. The orientation independent behavior of sulfur segregation across various phase boundaries provides a raw interface complexion diagram and an opportunity to understand the role of sulfur in the migrating interface decohesion of alumina-forming alloy systems.

a HAADF image, b iDPC image (the blue dash lines indicate the disordered region and the blue and red spheres represent O and Al atoms, respectively), c EDS mapping and d line scanning analysis of the disordered sulfur segregation layer, as indicated by blue dash lines. e Atomic maps of all constituent elements from a 3D reconstruction. f, g 1D concentration and 2D mapping quantitative analysis of the oxide-matrix interface, which confirms the existence of sulfur segregation on the alumina side. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Quantitative analysis of sulfur at the interface was conducted by 3D-AP. Figure 2e shows a representative 3D reconstruction atom map of a typical oxide-matrix interface, which clearly displays the distribution of O, Al and Fe atoms. To analyze the distribution of S, a 30 × 20 × 20 nm3 region in the orange box of Fig. 2e was extracted, and a one-dimensional (1D) profile of elemental distribution along the cylinder was then obtained, which clearly verifies segregation of sulfur atoms. Although the detected concentration of sulfur in the layer with less than 1 nm thickness was significantly affected by interface broadening caused by the needle tip evaporation, the S content at the interface was roughly estimated to be as high as 18 at. % (Fig. 2f) by using the method proposed previously19. Such a high concentration of sulfur may be the reason for the highly disordered structure. In addition, a corresponding two-dimensional (2D) elemental mapping in Fig. 2g indicates that sulfur enrichment mainly occurred on the alumina side near the oxide-matrix interface. In light of all these observations, it can be speculated that the S-rich amorphous-like layer containing a substantial amount of Al and O atoms locally shares the Al2O3 lattice.

Although sulfur segregation has not been experimentally observed in phase boundaries at the atomic scale before, these amorphous-like (or liquid-like) nanometer-thick intergranular films (IGFs) were frequently observed in grain boundaries of metals. It has been reported that their existence is mainly originated from the strong segregating tendency to free metal surfaces and physical characteristics such as low melting point of sulfur20,21. Current findings confirm that sulfur also preferentially segregates along phase boundaries due to the high thermodynamic driving force, as evidenced by density functional theory (DFT) calculation shown in Fig. 3.

a Filtered iDPC image and an intensity line profile taken across the scale-matrix interface (orange line). b A simple oxide-matrix interface, similar to a, constructed by a DFT simulation. c Change of Gibbs free energy as sulfur diffuses from the matrix to the interface. d The 2D ELF maps and e PDOS curves between typical S atoms and other nearest atoms (Al and O). f iDPC imaging and g EDS mapping analysis of the detached scale region. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Segregation and decohesion mechanism of sulfur at the oxide-matrix interface

With the information of atomic configuration and composition, the segregation was further modeled and analyzed by calculations. Figure 3a is a filtered iDPC image with higher magnification used to analyze the disordered segregation at atomic scale. The intensity profile analysis along the orange dash line from the top to bottom of the image reveals the atomic arrangement near the interface. The high-intensity peaks represent the atomic columns of oxygen, whilst the low-intensity peaks represent the atomic columns of Al. Regular periodic intensity evolution maintains within the outer Al2O3 scale while irregular intensity evolution with a thickness of about four atomic layers emerges in the interface layer at the scale side where sulfur containing.

Based on the above analysis, a model was then built via randomly replacing one-fifth of Al and O atoms in the corresponding atomic layers at the oxide-matrix interface with sulfur atoms, followed by relaxation. As shown in Fig. 3b, the model subsequently formed and replicated a disordered layer, which is consistent with the experimental results. By initiatively changing the location of sulfur in the model, we found that the Gibbs free energy of the system decreased markedly as sulfur atoms were displaced from the interior of the alumina to the interface (from −461.1 to −499.7 eV). Thus, the segregation along interfaces is thermodynamically favored by a high driving force. From a kinetics perspective, the growth of α-alumina is dominated by the diffusion process of O towards the oxide-matrix interface22. It can be inferred that the high concentration of sulfur segregation on the alumina side at the interface is caused by the inward growth of alumina during oxidation. In this process, the diffusion coefficient of sulfur in α-alumina and γ-Fe was calculated according to the reported data. It was found that the diffusion rate of sulfur in γ-Fe (1.69E-11 m2/s) is 3 orders of magnitude higher than that in α-Al2O3 (6.30E-14 m2/s), and both are much larger than that of constituent metallic elements (Supplementary Table 2)23,24. This result suggests that the rapid diffusion of sulfur from the γ-Fe matrix to the interface while the sluggish diffusion of sulfur in α-Al2O3 dynamically results in the special segregation configuration, rather than segregation along the free surface at the outer of the scale.

To uncover why specific sulfur segregation configurations can initiate interface cracking, statistical analysis, electron locational function (ELF) and projected density of states (PDOS) were conducted to reveal the atomic arrangement and bonding environment of sulfur atoms. Different from previous studies in classical Ni-S system25,26, it was found that S atoms in alumina tend to cluster in pairs with a closer interatomic distance in dashed box in Fig. 3b. We choose a typical sulfur-atom pair in the red dashed box, named S1 and S2. As shown in Fig. 3d, the two-dimensional (2D) ELF maps clearly show that S atoms form a strong covalent bond with each other, and the interatomic distance of the S-atom pair is 1.98 Å. While the surrounding Al and O atoms are repelled by these S-atom pairs (the nearest interatomic distances are 2.6 Å and 2.8 Å, respectively), indicating the two S atoms do not bond with the nearby Al and O atoms. The valence electron density at the midpoint between two adjacent S-Al and S-O is close to zero. In Supplementary Fig. 2, it is found that all other S-atoms pairs follow this rule, which proves that this phenomenon is not occasional. In addition, it was found that the PDOS in Fig. 3f of a typical sulfur atom has almost no coincidence with surrounding Al atoms, and interaction between S and O is not sufficient to maintain the cohesion of the scale, despite slight overlap above the Fermi level. It is worth mentioning that regardless of the interaction between S and the matrix Fe, the oxide scale will spall off along the interface between sulfur and alumina since sulfur cannot form strong bonds with Al or O, as demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 3.

To verify the above mechanism, a high-resolution investigation was conducted on the cracks at the oxide-matrix interface in Fig. 1c. As shown in Fig. 3g, zigzag fracture planes can be observed on the scale side. An amorphous-like layer with a thickness of about 5 nm was formed on the surface of the fractured matrix side. The EDS mapping in Fig. 3h shows that this layer is a new Cr-rich scale due to the secondary oxidation of the exposed fresh matrix at low temperatures, rather than the sulfur segregation, which is further verified by Supplementary Fig. 4. In addition, sulfur segregation (yellow arrow) can be observed between the new oxide layer and the matrix, suggesting that the crack propagates along the interface and the poor bonding between sulfur and alumina.

Adhesion improvement guided by the atomistic mechanism of sulfur effect

Therefore, eliminating segregated-S to remove weak bonds may be an effective way to improve adhesion. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 5, the S impurity is difficult to eliminate by H2-annealing treatment because it is only a few ppm in the matrix. According to the S-destruction mechanism, we need to find an element that not only have stronger segregation tendency, but also can form strong bonding with the oxide. For this purpose, we found that the standard molar Gibbs energy for the formation of zirconium oxide (−1042.8 kJ/mol) is lower than that of transition metal oxides (i.e., Fe2O3 is −742.2 kJ/mol)27, suggesting that Zr can form strong bonds with O relatively. Moreover, we substituted S with Zr atoms in the above model and calculated the segregation energy (\({{\rm{E}}}_{{\rm{seg}}}\)) (or impurity formation energy) by the following equation28,29:

where \({{\rm{E}}}_{{{{\rm{Al}}}}_{2}{{{\rm{O}}}}_{3}/M/{{\rm{Fe}}}}^{{{\rm{slab}}}}\) and \({{\rm{E}}}_{{{{\rm{Al}}}}_{2}{{{\rm{O}}}}_{3}/{{\rm{Fe}}}}^{{{\rm{slab}}}}\) are the total energy of M-doped and clean Al2O3/Fe interface slab, \({{\rm{E}}}_{M}^{{{\rm{bulk}}}}\) and \({{\rm{E}}}_{{{\rm{Al}}}/{{\rm{O}}}}^{{{\rm{bulk}}}}\) are the energies of the single M and substituted (Al or O) atoms in the relaxed bulk, respectively. A smaller \({{\rm{E}}}_{{{\rm{seg}}}}\,\) means that doped atoms can more easily segregate to the interface. The results in Fig. 4a show that there is a significant decrease in \({{\rm{E}}}_{{{\rm{seg}}}}\) of the system alloyed with Zr, indicating that the driving force for Zr segregation is stronger than that for S (i.e., from 52.0 to 34.3 eV).

a The segregation energy and ideal adhesion work calculated by using the initial S-segregation model and Zr-doped model. b Top-view and c cross-section view of the oxide scale grown spontaneously on the surface, and d EDS mapping of the oxide-matrix interface on the surface of an AFA specimen doped with 0.1 at. % Zr and oxidized after 500 h in air+10%H2O atmosphere at 900 °C. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Then, we calculated the ideal adhesion work using Eq. 2 to evaluate the adhesion of the oxide-matrix interface after Zr doped30,31:

Among them, \({{\rm{E}}}_{{{{\rm{Al}}}}_{2}{{{\rm{O}}}}_{3}/M}^{{{\rm{slab}}}}\) and \({{\rm{E}}}_{{{\rm{Fe}}}}^{{{\rm{slab}}}}\) are the total energy of oxide and Fe slab, respectively. \({{\rm{E}}}_{{{{\rm{Al}}}}_{2}{{{\rm{O}}}}_{3}/M/{{\rm{Fe}}}}^{{{\rm{slab}}}}\) is the total energy of the Fe-S-Al2O3 interface system, and \(A\) is the area of the interface. In comparison with the S segregation layer, the model in which Zr substitutes S lattice sites has a higher adhesion work (from 124.0 to 128.0 J/m2), which theoretically verifies our viewpoint. As expected, after 500 h cyclic oxidation at the same condition, the oxide scale on the surface of the Zr-doped AFA specimen indeed did not spall off, indicating formation of an adherent oxide-matrix interface (Fig. 4b, c). As shown in Fig. 4d, EDS mapping captured Zr atoms at the interface but without S segregation, which vividly validates our viewpoint experimentally.

Discussion

Although sulfur is often reported as a grain boundary (GB) segregator and embrittlement agent in alloys, traditional wisdom suggests that its detrimental effect can be essentially eliminated when the sulfur concentration is reduced to several tens of ppm32. Indeed, in recent studies, S-rich amorphous-like intergranular films have been probed at GBs of transition metals and ceramics26. However, the amorphous-like layer caused by indigenous impurity S segregation at the phase interface between oxide and alloy was rarely reported. More importantly, our work reveals that severe segregation at interfaces and detrimental effects occurred even when the sulfur concentration in the raw materials is only ppm level, which breaks the general knowledge about segregation. This phenomenon means that the tendency of sulfur segregation at the oxide-matrix boundaries is much higher than that at GBs, and the segregation along the interfaces must be taken into account even if the material is highly purified.

Furthermore, the segregation morphology and embrittlement mechanism along the interfaces are also different from those reported at GBs. On the one hand, in the case of oxidation resistance, the interface is continuously moving, and during the oxidation process, the segregated sulfur atoms are always on the scale side of the interface during oxidation, which is distinguished from those boundary complexions with both sides containing segregated atoms. This difference may be resulted from the different solubility of sulfur in oxide scale and alloy matrix. On the other hand, compared with the interface bonding between the oxide scale and alloy matrix, GBs of metallic materials are generally strongly bonded, and the presence of relatively weak S–S bond is considered the root cause of embrittlement. However, in this case, the S–S bond is still stronger than S–O/Al bonds in the amorphous oxide layer. In conjunction with the experimental observation that cracking occurred right along the interface between the segregated layer and alumina scale, it is believed that the weaker S–O/Al is responsible for cracking and spallation. Based on these findings, we have successfully eliminated S segregation through microalloying and significantly improved the oxide scale adhesion, which may also provide a solution to GB brittleness caused by impurity element segregation.

In summary, this study clearly demonstrates that ppm-level sulfur impurities diffuse rapidly and progressively segregate to the interface during the oxidation process, leading to the formation of an amorphous-like intermediate layer containing a high centration of sulfur atoms at the alumina side. DFT calculations suggest that both Al and O atoms in alumina cannot form strong bonds with S, which is the reason why S atoms form pairs and repel other atoms, leading to occurrence of debonding. Moreover, we doped Zr in the alloy and successfully eliminated S segregation in the oxide-matrix interface, resulting in much-improved cohesion of the oxide scale and vividly verifying our findings. Our current work not only enrich our fundamental understanding of fracture and adhesion mechanisms at the interface between oxide scale and matrix, but also suggests that even in materials with ppm sulfur, preventing sulfur segregation is essential for improving scale adhesion and enhancing oxidation resistance of the material for its high-temperature uses.

Methods

Material preparation and microstructure characterization

Alloy ingots with a nominal composition of Fe–25Ni–18Cr–3Al–0.8Mo–0.5 Nb (wt. %) were prepared by arc-melting under argon atmosphere using metals with purity above 99.99 at. %. The actual composition was measured by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES), and the content of S was determined to be less than 30 ppmw (Supplementary Table 1). The as-cast bars were first homogenized and cold rolled, followed by recrystallization annealing. Oxidation tests of the samples with dimension of 10 × 10 × 2 mm3 were performed in flowing air with 10% water vapor at 900 °C, followed by air cooling. Water vapor was introduced by distilled water atomization into the flowing gas stream above its condensation temperature. The specimens were positioned in alumina boats (multiple specimens per boat) in the furnace hot zone so as to expose the specimen faces parallel to the flowing gas33. Surface microstructures were examined using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Zeiss, supra 55), and specimens for atomic analysis were prepared by focused-ion beam (FEI, Helios G5 UX). The detailed cross-section morphology, atomic structure and chemical composition of the oxide scale were examined on a Thermo Fisher Scientific TEM (Themis Z, 300 kV), which is coupled with atomic resolution high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF), iDPC and Energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) detectors. APT quantitative analysis was performed on CAMECA LEAP 5000 XS, and data was collected at a base temperature of 60 K using 80 pJ pulse energy in laser mode with a repetition rate of 200 kHz. The laser and high voltage were progressively increased to maintain a detection rate of 5 ions per 1000 pulses. The APT data was reconstructed using CAMECA IVAS in AP Suite 6.3.

Density functional theory simulations

DFT calculations were performed using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP) code34,35 with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzehof (PBE)36 potential of Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) for exchange-correlation functional. The convergency of the total energy for calculation parameters such as kinetic energy cutoff and the number of k points for the Brillouin zone integration were carefully tested. A plane wave cutoff energy of 400 eV was selected. Brillouin zone integration was performed on k points of 2 × 4 × 2 Monkhorst–Pack mesh for the 225-atom supercells, which is sufficient to obtain fully converged results. Atomic positions were relaxed within the conjugate gradient algorithm until the forces on all atoms were converged to be less than 10−2 eV/Å. The total energy was converged to better than 10−5 eV/atom using Gaussian smearing.

The cells of α-Al2O3 for R-3C (No.167) and γ-Fe for FM-3M (No.225) were selected to construct the oxide-alloy interface models. With reference to the experimental results, a model with α-Al2O3 slab along the \([2\bar{1}\bar{1}0]\) orientation (2 × 2 × 2 supercell, 173 atoms) on the top and face-centered cubic (fcc) Fe slab along the [100] orientation (5 × 5 × 5 supercell, 52 atoms) on the bottom was established, and the slab model was separated with a vacuum length of 1.4 Å. The Al2O3-M-Fe systems were constructed by randomly replacing the Al and O atoms at the interface (4 disordered atomic layers in alumina) with varying numbers of S (20) and Zr (10) atoms. The atoms at the outermost layer were fully fixed and the other atoms were relaxed at the bulk lattice.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Meetham, G. W. High-temperature materials: a general review. J. Mater. Sci. 26, 853–860 (1991).

Wachsman, E. D. & Lee, K. T. Lowering the temperature of solid oxide fuel cells. Science 334, 935–939 (2011).

Zhou, L. et al. Alumina-forming austenitic stainless steel for high durability and chromium-evaporation minimized balance of plant components in solid oxide fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 47, 38334–38347 (2022).

Liu, M., Jiang, L. & Demkowicz, M. J. Role of slip in hydrogen-assisted crack initiation in Ni-based alloy 725. Sci. Adv. 10, 2118 (2024).

Richardson, T. et al. Shreir’s Corrosion (Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2009).

Hou, P. Y. & Stringer, J. Oxide scale adhesion and impurity segregation at the scale/metal interface. Oxid. Met. 38, 323–345 (1992).

Smialek, J. L. Invited review paper in commemoration of over 50 years of Oxidation of Metals: alumina scale adhesion mechanisms: a retrospective assessment. Oxid. Met. 97, 1–50 (2022).

Xing, L., Fan, X., Wang, M., Zhao, L. & Bao, Y. The formation mechanism of proeutectoid ferrite on medium-carbon sulfur-containing bloom. Metall. Mater. Trans. B Process Metall. Mater. Process. Sci. 52, 3208–3219 (2021).

Xing, L., Gu, C., Lv, Z. & Bao, Y. High-temperature internal oxidation behavior of surface cracks in low alloy steel bloom. Corros. Sci. 197, 110076 (2022).

Funkenbusch, A. W., Smeggil, J. G. & Bornstein, N. S. Reactive element-sulfur interaction and oxide scale adherence. Metal. Trans. A 16, 1164–1166 (1985).

Hou, P. Y. Beyond the sulfur effect. Oxid. Met. 52, 337–351 (1999).

Hou, P. Y. Impurity effects on alumina scale growth. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 86, 660–668 (2003).

Hou, P. Y. Segregation phenomena at thermally grown Al2O3/alloy interfaces. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 38, 275–298 (2008).

Smialek, J. L. Effect of sulfur removal on Al2O3 scale adhesion. Metall. Trans. A 22, 739–752 (1991).

Smialek, J. Maintaining adhesion of protective Al2O3 scales. JOM 52, 22–25 (2000).

Yang, C. et al. Interfacial superstructures and chemical bonding transitions at metal-ceramic interfaces. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf6667 (2021).

Tabata, C. et al. Quantitative analysis of sulfur segregation at the oxide/substrate interface in Ni-base single crystal superalloy. Scr. Mater. 194, 113616 (2021).

Yamamoto, Y. et al. Creep-resistant, Al2O3-forming austenitic stainless steels. Science 316, 433–436 (2007).

Peng, Z. et al. An automated computational approach for complete in-plane compositional interface analysis by atom probe tomography. Microsc. Microanal. 25, 389–400 (2019).

Grabke, H. J., Wiemer, D. & Viefhaus, H. Segregation of sulfur during growth of oxide scales. Appl. Surf. Sci. 47, 243–250 (1991).

Černošek, Z., Holubova, J., Cernoskova, E. & Růžička, A. Sulfur-a new information on this seemingly well-known element. J. Non Oxide Glasses. 1, 38–42 (2009).

Naumenko, D., Pint, B. A. & Quadakkers, W. J. Current thoughts on reactive element effects in alumina-forming systems: in memory of John Stringer. Oxid. Met. 86, 1–43 (2016).

Doremus, R. H. Diffusion in alumina. J. Appl. Phys. 100, 101301 (2006).

Zhai, Y. et al. Initial oxidation of Ni-based superalloy and its dynamic microscopic mechanisms: The interface junction initiated outwards oxidation. Acta Mater. 215, 116991 (2021).

Yamaguchi, M., Shiga, M. & Kaburaki, H. Grain boundary decohesion by impurity segregation in a nickel-sulfur system. Science 307, 393–397 (2005).

Hu, T., Yang, S., Zhou, N., Zhang, Y. & Luo, J. Role of disordered bipolar complexions on the sulfur embrittlement of nickel general grain boundaries. Nat. Commun. 9, 2764 (2018).

Haynes, W. M. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (CRC Press, Florida, 2014).

Xie, H., Zhao, N., Shi, C., He, C. & Liu, E. Effects of active elements on adhesion of the Al2O3/Fe interface: a first principles calculation. Comput. Mater. Sci. 188, 110226 (2021).

Li, Z., Xie, W., Chen, J., Cai, C. & Zhou, G. Effects of Lu on the α-Al2O3/β-NiAl interface adhesion from first-principles calculations. Mater Today Commun. 38, 107820 (2024).

Lipkin, D. M., Israelachvili, J. N. & Clarke, D. R. Estimating the metal-ceramic van der Waals adhesion energy. Philosoph. Mag. A 76, 715–728 (1997).

Zhang, Z., Hu, C. C., Chen, H. & He, J. Pinning effect of reactive elements on structural stability and adhesive strength of environmental sulfur segregation on Al2O3/NiAl interface. Scr. Mater. 188, 174–178 (2020).

Loier, C. & Boos, J. The influence of grain boundary sulfur concentration on the intergranular brittleness of nickel of different purities. Metall. Trans. A Phys. Metall. Mater. Sci. 12, 1223–1233 (1981).

Xu, X., Zhang, X., Chen, G. & Lu, Z. Improvement of high-temperature oxidation resistance and strength in alumina-forming austenitic stainless steels. Mater. Lett. 65, 3285–3288 (2011).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for open-shell transition metals. Phys. Rev. B Condens Matter 48, 13115–13118 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B Condens Matter 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Burke, K., Ernzerhof, M. & Perdew, J. P. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFB3705201), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. U20B2025, 12335017, 52322102, 52101120, 51971018, 52222102), the Funds for Creative Research Groups of China (51921001), and 111 Project (B07003, BP0719004). S.H.J. acknowledges the financial support from the Fundamental Research Fund for the Central Universities of China (FRF-TP-24-05C, FRF-MP-20-43Z, FRF-TP-18-093A1). Project of SKLAMM-USTB (2023-Z14, 2022Z-01), NSFC Young Scientist Fund (52101120), COMAC Shanghai Aircraft Design & Research Institute (2022-1150), China Nuclear Power Technology Research Institute Co., Ltd. (2021-0811), HUAWEI Technologies Co., Ltd. (2021-0399).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.L. and H.W. prepared specimens. W.Z. and Z.Y. conducted electron microscopy. C.L. and H.Z. conducted atom probe tomography. C.L., H.Z., and X.L. conducted atomistic simulation. C.L. and Y.W. conducted data analysis. C.L., S.J., and Z.Y. wrote the manuscript. X.Z., S.J., and Z.L. conceived, designed, and supervised this study. All of the authors discussed the results, analyzed data, and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, C., Zheng, W., Zhong, H. et al. Unveiling the atomistic mechanism of oxide scale spalling in heat-resistant alloys. Nat Commun 16, 2291 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57635-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57635-7

This article is cited by

-

High-Temperature Oxidation and Thermal Expansion Behavior of NbTi–X (X = 5Co, 10Cr, 10Ni, 10CoCrNi) Refractory Medium Entropy Alloys

Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A (2025)

-

Impact of Initial Surface Roughness on Oxidation and Pickling Response of AISI 304L and 430

Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance (2025)