Abstract

Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) is widely used in nanomedicine design, but emerging PEG immunogenicity in the general population is of therapeutic concern. As alternative, polyoxazolines are gaining popularity, since “polyoxazolinated” nanoparticles show long-circulating properties comparable to PEGylated nanoparticles in mice. Here, we show species differences in opsonization and differential uptake by monocytes and macrophages of nanoparticles coated with either poly-2-methyl-2-oxazoline or poly-2-ethyl-2-oxazoline. These nanoparticles evade murine opsonization process and phagocytic uptake but porcine ficolin 2 (FCN2), through its S2 binding site, recognizes polyoxazolines, and mediates nanoparticle uptake exclusively by porcine monocytes. In human sera, FCN opsonization is isoform-dependent showing inter-individual variability but both FCN2 and complement opsonization promote nanoparticle uptake by human monocytes. However, nanoparticle uptake by human and porcine macrophages is complement-dependent. These findings advance mechanistic understanding of species differences in innate immune recognition of nanomaterials’ molecular patterns, and applicable to the selection and chemical design of polymers for engineering of the next generation of stealth nanoparticles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Blood opsonization of nanomedicines promotes their recognition and clearance by blood leukocytes and tissue macrophages such as Kupffer cells and splenic marginal zone and red-pulp macrophages1,2,3,4. This mode of clearance is advantageous for the treatment of phagocytic cell infections, enzyme deficiency, and reprogramming/immunomodulation within the context of pro- and anti-inflammatory responses4,5, but it compromises nanomedicine delivery to pathological cells outside the reticuloendothelial system6. The third complement protein (C3) is considered among the most important blood opsonins2,3,4,7,8,9. C3 is proteolytically cleaved on activation of the complement system, where generated fragments C3b and iC3b promote nanomedicine recognition by phagocytic cells through their complement receptors7,8,9. Pathways and mechanisms of complement activation and C3 opsonization by preclinical and clinical nanomedicine have received considerable attention8,10,11. There are some degree of controversy about whether other complement proteins, notably the pattern-recognition molecules C1q and ficolins, can directly prime particulate and cells for phagocytic clearance12,13. For example, CD93 (C1qRp) is the receptor recognizing the collagen-like stalk domain of C1q, which contributes to the removal of apoptotic cells in vivo, but is not required for C1q-mediated enhancement of phagocytosis12.

Considering the importance of opsonization in nanoparticle pharmacokinetics, several studies have indicated that the opsonization of nanomedicines and immune cells responses to opsonized nanoparticles in preclinical species may not necessarily resemble those in humans10,14,15. For example, mice are widely used models for studying pharmacokinetic and biodistribution of intravenously injected nanoparticles, but there are major differences between mouse and human complement responses10,14,15,16,17,18,19. First, the majority of common laboratory mouse strains have exceedingly low complement levels compared with humans16,18,19. Second, studies with NPs have identified major differences in NP opsonization between mice and human sera10. For example, intravenously injected NPs coated with poly-2-alkyl-2-oxazolines, such as poly-2-methyl-2-oxazoline (PMOXA), circulate for prolonged periods of time in mice20,21,22. In line with these observations, PMOXA-coated NPs avoid C3 opsonization in mouse serum, but in human sera, PMOXA-coated NPs are efficiently opsonized by C3, and this promotes their recognition and uptake by human blood leukocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages10. Another preclinical example is the porcine model, which has been used for assessing immune responses and infusion reactions to nanomedicines15, but there are differences in NP-mediated complement activation, blood opsonization, and macrophage clearance between pigs and humans23,24. Accordingly, species disparities and sensitivities in NP opsonization and phagocytic cell responses could pose major translational consequences for human nanomedicine design and development, and prompt more studies to delineate similarities and differences.

In this work, we study species differences (mouse, pig, and human) in NP opsonization and phagocytic cell responses using a preclinical organically modified silica (ORMOSIL) NP model. These NPs have excellent safety records compared with inorganic amorphous silica and amenable to surface modification with a wide range of polymers10,25,26,27,28,29,30, thereby offering a valuable tool for comparing the impact of polymer coating with similar antifouling properties but different chemical structure on opsonization processes. Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) is widely used for engineering and stabilization of clinical nanomedicines, but the emerging PEG immunogenicity and complement activation by PEGylated nanomedicines is compromising their therapeutic efficacy31,32. As such, general interest in polyoxazolines such as PMOXA and poly-2-ethyl-2-oxazoline (PEOXA) in NP surface engineering and nanomedicine design is increasing33,34,35, despite the fact the stealthing property of polyoxazolination has only been demonstrated in the murine model10,20,21. Thus, we delineate species differences in opsonization and phagocytic cell response to PEGylated, PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated ORMOSIL NPs. Polyoxazolination confers stealthing behavior to the murine complement opsonization and phagocytic uptake, but we identify ficolin 2 (FCN2) as the opsonic factor promoting the uptake of polyoxazolinated NPs by pig monocytes. In human sera, FCN opsonization is isoform-dependent with interindividual variability, but FCN and complement opsonization both promote NP uptake by human monocytes. We further identify the polymer-binding site of FCN2 and elaborate on the importance of this finding in relation to polymer selection for NP stabilization as well as in broader recognition of microbial or altered-self patterns. Finally, in contrast to monocytes, NP uptake by human and porcine macrophages is FCN-independent, but complement activation/opsonization is required for uptake. These results contribute to the understanding of the broader roles of innate pattern-recognition molecules in NP clearance as well as species disparities in NP opsonization and phagocytic cell responses.

Results

NP synthesis and characterization

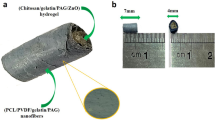

Uncoated and polymer-coated ORMOSIL NPs were prepared by ammonia-catalyzed microemulsion polymerization of vinyltrietoxysilane (VTES) as previously described (Supplementary Fig. 1)10,36,37. Fluorescent labeling and surface functionalization with PEG (MW = 2000 Da, degree of polymerization = 44), PMOXA (MW = 4000 Da, degree of polymerization = 40), and PEOXA (MW = 3000 Da, degree of polymerization = 30) were achieved by copolymerizing VTES with a Rhodamine-B triethoxysilane derivative and, when needed, with the trimethoxysilane derivatives of the polymers. All NPs exhibited a near-spherical morphology (visualized by transmission electron microscopy, Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1) with diameters (mean ± SD) of 70 ± 18, 93 ± 26, 101 ± 34, and 100 ± 20 nm for typical batches of uncoated, PEGylated, PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs, respectively. Polydispersity indices were below 0.1. Thermogravimetric analysis indicated ~7800 PEG molecules, 8000 PMOXA molecules, and 8300 PEOXA molecules per designated NP. These arrangements correspond to a surface density of 0.28, 0.25, and 0.26 nm−2 for PEG, PMOXA, and PEOXA, respectively. As expected, the ζ-potential values were slightly negative37. All NPs exhibited similar UV−visible spectra (Supplementary Fig. 2). Rhodamine-B loadings were in the 0.1−0.2% w/w range.

Species comparison of NP serum proteome

We analyzed the deposition of serum proteins on NPs after incubation in sera of human (HS), pig (PS), and mouse (MS) by shot-gun mass spectrometry (Fig. 1a–c and Supplementary Data 1–6). Complement proteins were more abundant in HS- and PS-derived proteome than that of MS-derived proteome. In the case of HS and PS, complement proteins were more abundant in the proteome of PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs compared with uncoated and PEGylated NPs. In MS, the abundance of complement components was considerably lower than that of HS- and PS-derived proteome. This was irrespective of the polymer type. C3 and properdin (a positive regulator of the complement alternative pathway) were among the most abundant proteins in the HS- and PS-derived NP proteome. EDTA (an inhibitor of all three-complement pathways)38 strongly reduced the presence of C3, properdin, and other complement proteins in HS- and PS-derived NP proteome but, as expected, it had no effect on complement recruitment by NPs in MS (Fig. 1a, b). PEGylated NPs also activated complement to some extent; however, PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs were more potent in activating complement compared with uncoated NPs in both HS and PS, but not in MS. Species differences in complement deposition were consistent in proteomics experiments performed with different sera preparations (Fig. 1c). Species differences in complement activation by PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs was also consistent with C3a liberation as determined by western blot analysis and using zymosan as positive control (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 3). Again, consistent with these findings, mass spectrometry after SDS-PAGE digestion of separated polypeptides (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Figs. 4, 5, and Supplementary Data 7) confirmed C3 cleavage. Following HS and PS incubation, the cleavage products were C3c α’ chain fragment 2, C3dg, and C3c α’ chain fragment 1. Notably, C3dg and C3c α’ chain fragment 1 migrated in SDS-PAGE with an apparent Mw much higher than their expected Mw (100–200 vs 70 KDa), indicating their covalent binding to other proteins deposited on NP surfaces. This further confirms NP opsonization by iC3b, and is consistent with recent findings that the majority of C3 covalently binds to adsorbed proteins on nanoparticle surfaces38.

a Indicated NPs were incubated in human serum (HS), pig serum (PS), and mouse serum (MS) at 37 °C for 20 min without (black) or with (red) EDTA (10 mM final concentration), washed and subjected to shot-gun mass spectrometry analysis. The identified polypeptides are represented in the order of abundance in the serum-treated samples, based on the label-free quantification parameter iBAQ. C3 (blue), other major complement-related proteins (black), clusterin (orange), ficolin isoforms (FCN), and mannose-binding lectin (MBL) (green) are highlighted. Source data are provided as Source Data file. b Amount of C3 and properdin (iBAQ) associated with uncoated or polymer-coated NPs in normal and EDTA-chelated sera. Source data are provided as Source Data file. c Fold increase (mean ± SD) of major complement proteins (sum of C3 and properdin) in polymer-coated NP proteome relative to uncoated NPs (pink line), after incubation with sera from different human subjects and pigs and pooled sera from different mice (MS). HS: n = 8 (PEG), n = 10 (PMOXA), n = 6 (PMOXA); PS: n = 5 (PEG), n = 7 (PMOXA), n = 4 (PEOXA); MS: n = 6 (PEG), n = 6 (PMOXA), n = 3 (PEOXA). Significant p values (*<0.05) are derived from two-sided t-tests: p = 2,6E-5 (HS-PMOXA vs HS-PEG), p = 0.013 (HS-PEOXA vs HS-PEG); p = 0.034 (PS-PMOXA vs PS-PEG), p = 0.016 (PS-PEOXA vs PS-PEG); p = 0.03 (MS-PMOXA vs MS-PEG), p = 0.32 (n.s.) (MS-PEOXA vs MS-PEG). Source data are provided as Source Data file.

a Western blot detection of C3a release after incubation of PMOXA- and PEOXA-NPs with HS, PS, and MS as above, using anti-human C3a polyclonal antibodies. Negative (no NP, mock) and positive zymosan (ZYM) controls are included. Sup indicates the serum supernatant after NPs centrifugation, while pellet indicates washed NPs. b C3 convertase-dependent processing of PMOXA-coated NPs. Silver-stained SDS-PAGE separation in reducing (+βme) conditions of the polypeptides bound to PMOXA-coated NPs after incubation with HS, PS, and MS without or with selective Ca2+ chelation (10 mM EGTA and 2 mM MgCl2, EGTA/Mg2+). Properdin and Ficolin 2 (FCN2) are also indicated. Major C3 fragments and their expected and apparent MW, (shown in scheme), were identified by mass spectrometry after in-gel digestions of the indicated bands and their relative amounts was estimated by using the label-free parameter emPAI (table in Fig. 2b). No mouse complement polypeptides were identified. Source data are provided as Source Data file. Uncoated and polymer-coated NPs were incubated with PS preparations (c) from four different animals (conventionally annotated with #) or with HS preparations (d) from eight different donors (annotated with #). The amount of FCN3 and FCN2 isoforms was estimated after shot-gun proteomics (iBAQs). Source data are provided as Source Data file.

In parallel with C3 opsonization of NPs, shot-gun mass spectrometry also revealed that the PS-derived proteome of PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs was strongly enriched with FCN2 (Figs. 1a, 2b and Supplementary Figs. 4, 5A). This trend was reproducible in sera from different animals (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Data 1, 2, 6). Contrary to the porcine model, the HS-derived NP proteome contained smaller amounts of FCN but with isoform inter-subject variability. Thus, of eight analysed sera, the NP proteome was positive for FCN3 but negative for FCN2 in 4 sera, whereas the reverse trend was observed for the other 4 sera (Fig. 2d, Supplementary data 1, 2, 4, 5, 8–10). The reason for this inter-subject variability is not clear, but it may be related to the polymorphic nature of FCN genes39. Indeed, the FCN2 gene bears functional polymorphic sites that regulate FCN2 expression and function. Furthermore, FCN2 and FCN3 form heterocomplexes, and this could affect the serum concentration of free FCN2 and FCN3 for binding competition40. Based on mass spectrometry, when human FCN2 is detected, it is more enriched in the proteome of PEOXA-coated NPs compared with PMOXA-coated NPs. In contrast to PS and HS, ficolins did not appear in the MS-derived NP proteome.

The observed species differences in differential abundance (or absence) of FCN isoforms in the biomolecule corona of PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs could indicate differences in their affinity for PMOXA and PEOXA or in their serum concentration. Indeed, considering the latter, FCN2, FCN3, and FCN1 are the major isoforms in pig, human, and mouse serum, respectively, with abundance ratios of 27:4:141,42 (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Data 11). Notwithstanding, the species-specific binding pattern of FCN isoforms to NPs is interesting, since ficolins are pattern-recognition molecules belonging to the soluble defense collagen family43, which not only can activate complement via lectin pathway, but also directly function as opsonins13,43,44. Thus, in contrast to mouse, where NPs evade C3 and FCN opsonization, which in turn might explain the long-circulating profile of polyoxazolines-coated NPs in this species20,21,22, combined C3 and FCN opsonization of NP might endow a recognition hierarchy in the clearance of PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs by different types of human and porcine phagocytic cells.

Phagocytic cell responses to opsonized NPs

To assess the role of serum opsonization in NP recognition by phagocytic cells, we incubated monocytes and macrophages with NPs in relevant sera and followed their uptake. Both human- and porcine-derived macrophages internalized PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs more intensely than PEGylated and uncoated NPs (Fig. 3a–c). On the other hand, NPs uptake by mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages was similar (observed differences were not statistically significant) irrespective of their polymer coat (Supplementary Fig. 7). Pig and human monocytes also internalized PMOXA and PEOXA-coated NPs more efficiently than their PEGylated and uncoated counterparts, although uptake was less effective when compared with macrophages in absolute terms (Fig. 3c).

Macrophages and monocytes from humans and pigs were incubated for 3 h at 37 °C with uncoated NPs, and PEG-, PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs in the presence of serum, and analysed by fluorescence confocal microscopy (a, b) or by FACS (c). FITC lysotracker (green) was used to mark acidic endosomes. NPs are labeled in red. FACS data are the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) ± SD from independent experiments (for human macrophages: n = 6 (uncoated), n = 7 (PEG), n = 20 (PMOXA), n = 15 (PEOXA); for human monocytes: n = 14 (uncoated), n = 16 (PEG), n = 30 (PMOXA), n = 19 (PEOXA); for pig macrophages: n = 3 (uncoated), n = 3 (PEG), n = 7 (PMOXA), n = 7 (PEOXA); for pig monocytes: n = 3 (uncoated), n = 3 (PEG), n = 4 (PMOXA), n = 4 (PEOXA)). Significant p values (<0.05) were determined by Brown-Forsythe and Welch’s ANOVA with Dunnett’s T3 multiple comparison tests. d NP uptake by human and pig macrophages and monocytes in the absence and presence of EDTA-chelated serum. Bars represent % uptake of NPs compared with control (mean ± SD; for macrophages in HS: n = 11 (PMOXA), n = 10 (PMOXA + EDTA), n = 10 (PEOXA), n = 10 (PEOXA + EDTA); for macrophages in PS: n = 7 (PMOXA), n = 7 (PMOXA + EDTA), n = 8 (PEOXA), n = 8 (PEOXA + EDTA); for monocytes in HS: n = 5 (PMOXA), n = 4 (PMOXA + EDTA), n = 8 (PEOXA), n = 7 (PEOXA + EDTA); for monocytes in PS: n = 8 (PMOXA), n = 8 (PMOXA + EDTA), n = 5 (PEOXA), N = 5 (PEOXA + EDTA). Significant p values (<0.05) were calculated by two-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple comparison tests. e Analysis of the effect of Ca2+ (10 mM EGTA and 2 mM MgCl2, EGTA/Mg2+) and of Ca2+/Mg2+ chelation (10 mM EDTA), left panels, and of phosphoserine (P-ser; right panels) on the association of human and pig C1q with PMOXA-coated NPs incubated with HS ad PS. f Effect of Ca2+ chelation (EGTA/Mg2+) and of phosphoserine (P-ser) (5 or 20 nM) on PMOXA-coated NP uptake by human and pig macrophages in HS or PS. Values are MFI ± SD (n = 3 independent experiments). Significant p values (<0.05), tested by Brown-Forsythe and Welch’s ANOVA and Dunnett’s T3 tests. For all panels, source data are provided as Source Data file.

The uptake of PS-opsonized PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs by pig macrophages was inhibited following Ca2+/Mg2+ chelation, as it was the case for the uptake of HS-opsonized PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs by human macrophages (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 8). This could indicate a role for Ca2+/Mg2+-dependent C3 opsonization as a plausible mechanism for PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NP recognition by both human and pig macrophages. Consistent with this suggestion, Ca2+ chelation in HS and PS considerably reduced C1q binding to PMOXA-coated NPs, leading to poor C3 opsonization through inhibition of the classical pathway (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 9A)45. Furthermore, the C1qC subunit antagonist phosphoserine46 inhibited C1q binding to PMOXA-coated NPs, and their uptake by porcine and human macrophages was comparable to that seen on Ca2+ chelation (Fig. 3e,f and Supplementary Fig. 9B). Therefore, direct binding of C1q to PMOXA-coated NPs could trigger activation of the classical pathway in both HS and PS. On the contrary, the uptake of MS-treated uncoated, PEGylated, PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs by mouse macrophages was Ca2+ insensitive (Supplementary Fig. 10), which is in line with poor NP opsonization by C3 reported here and elsewhere10. Therefore, the observed NP uptake by mouse macrophages is through complement-independent mechanisms.

Contrary to the findings with macrophages, the uptake of PS-opsonized PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs by pig monocytes was not affected by Ca2+/Mg2+ chelation, whereas that of HS-opsonized NPs by human monocytes was Ca2+ and Mg2+ sensitive, and consistent with previous reports10 (Fig. 3d). Thus, the interaction of pig monocytes with opsonized PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs proceeds without a need for C3 opsonization. Since, the biomolecule proteome of PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs was highly enriched with FCN2, and by considering that FCN2 is an opsonic molecule, it is plausible that FCN2 could play an active role in NP uptake by the porcine monocytes. This suggestion might also apply to human monocytes, particularly with PEOXA-coated NPs, where the inhibition by EDTA is significantly less effective compared with PMOXA-coated NPs.

FCN2 binding sites for PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs

FCN2 comprises a C-terminal with a globular fibrinogen-like domain (ligand-binding domains), which is preceded by a fibrillar collagen-like domain that mediates binding to the mannan-binding lectin-associated serine proteases (MASPs)43,44 and possibly to some cell surface receptors13. Four homotrimers of the FCN2 unit further oligomerize into a distinctive sertiform shape, a characteristic shared by other FCN isoforms as well as soluble defense collagens such as mannose-binding lectin (MBL), C1q, surfactant protein A (SP-A), and collectin-11 (CL-LK)43. Functional and substrate co-crystallization data has indicated that FCNs display four binding sites, S1–S447,48,49. Among the ficolin isoforms (FCN1, FCN2, and FCN3), FCN2 shows the highest preference towards acetylated substrates via S2 and S3 sites, while S1 and S4 are Ca2+-dependent binding sites for acetylated albumin and 1,3 β-d glucans49 (Supplementary Fig. 11A). Furthermore, S3 also binds to broad substrates such as phosphorylcholine, heparin, DNA and sucrose octasulphate (SOS)49.

To gain further insight into FCN2 binding to PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs, we first performed a homology modeling study using the available FCN2 crystal structure. Superposition of S2 binding sites of the human and porcine FCN2 suggests this is a highly conserved region (Fig. 4a), and consistent with sequence alignment. Accordingly, the physiological substrate N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (GlcNAc) may bind porcine and human FCN2 in a similar manner. Based on crystallography47,48, this ligand engages in a hydrogen bond network in the S2 site of FCN2. Indeed, Arg122 (Arg 157 in pig), Ser143 (Ser 178 in pig), and Glu 282 (Glu 317 in pig) form hydrogen bonds with hydroxyl, ether, and carbonyl moieties of GlcNAc, respectively. In addition to these directional polar interactions, some hydrophobic interactions also occur between GlcNAc and the S2 site. Indeed, the S2 site has two hydrophobic pockets. Side chains of Leu 142 (pig) and Leu 107 (human) accommodate the acetyl functionality, whereas Val 206 and Val 315 (pig) and Val 171 and Val 280 (human) interact with the C6 methylene of GlcNAc (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 11B). On the contrary, the S2 sites of human FCN3 and mouse FCN1 show significant differences when compared with the S2 site of human and pig FCN2 (Supplementary Fig. 12A, B). Similarly, the S3 binding site is highly conserved in human and pig FCN2 (Supplementary Fig. 12C), but not in human FCN3 (Supplementary Fig. 12D) and mouse FCN1 (Supplementary Fig. 12E).

a Localization of the three S2 sites for acetylated compounds, in the trimeric -COOH terminal binding domain of FCN2 (left) and superimposition of pig (green) and human (blue) S2 sites (right). b Two binding modes of N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (GlcNAc) to the S2 binding site of human FCN2, schematically highlighting the substrate coordination by hydrogen bonds and the insertion of hydrophobic aliphatic groups into the two hydrophobic pockets present in the site. c Effect of monosaccharide inhibitors on the binding of FCN2 to PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs. NPs were incubated with PS alone or in the presence of 100 mM GlcNAc (a natural substrate of FCN2), d-mannose (Man), a natural substrate of mannose-binding lectin, and d-galactose (Gal), as negative control. NPs were recovered, washed and FCN2 was identified based on SDS-PAGE mobility (green arrow, representative gel). The histogram represents the inhibition of FCN2 corona abundancy (densitometry of SDS-PAGE) in the presence of monosaccharides (mean ± SD; n = 7 independent experiments). Significant p values (<0.05) are derived from Brown-Forsythe and Welch’s ANOVA and Dunnett’s T3 tests. Source data are provided as Source Data file. d Dose response SDS-PAGE analysis of the amount of pig FCN2 bound to PMOXA-coated NPs after incubation in PS alone or in the presence of increasing doses of GlcNAc, Man, and Gal, as indicated. The IC50% value of GlcNac is shown. Source data are provided as Source Data file. e Effect of amide inhibitors on the binding of FCN2 to PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs. FCN2 (green arrow in a representative gel) was quantified (histogram of band densitometry) in the corona of NPs incubated in PS as in c in the presence of different amides (100 mM): N, N-dimethylpropionamide (DMNPr), N, N-dimethylacetamide (DMNAc), N, N-dimethylformamide (DMNF), N-formamide (MNF) and formamide (NF). The gel is representative and the data of the histogram are mean ± SD (n = 5 for PMOXA-ctrl, n = –4 for other samples). Significant p values (<0.05) are derived from Brown-Forsythe and Welch’s ANOVA and Dunnett’s T3 tests. The structures of amides are shown, revealing overlap with PEOXA monomer (DMNPr) or PMOXA monomer (DMNAc). f Dose response SDS-PAGE analysis of the amount of pig FCN2 bound to PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs after incubation in PS alone or in the presence of increasing doses of dimethylacetamide (DMNAc) and N,N-dimethylpropionamide (DMNPr). The IC50% values are shown. Source data are provided as Source Data file.

We used a library of known inhibitors and antagonists to assess FCN2 binding to PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs. Competition studies with SOS, which interferes with Lys221-mediated interaction with N-acetylated substrates49 in the S3 site, had no effect on FCN2 binding to NPs (Supplementary Fig. 13). This indicates that the S3 site in FCN2, which is conserved in both humans and pigs, is not involved in binding to PMOXA- and PEOXA -coated NPs. Similarly, a role for the Ca2+-sensitive S1 and S4 sites50 is ruled out, since FCN2 binding to PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs is marginally affected by chelating agents (Figs. 1a, 2b and Supplementary Fig. 4A). Next, we examined the role of S2 binding site using GlcNAc as the physiological substrate. GlcNAc (100 mM) effectively inhibited the binding of FCN2 to PMOXA-coated NPs in PS, whereas the MBL substrates d-mannose (Man) and the control sugar d-galactose (Gal) had no effect (Fig. 4c, d). The IC50% of GlcNAc on FCN2 binding to PMOXA-coated NPs (67 mM) is comparable to the IC50% of the same sugar on human FCN2 binding to GlcNAc-decorated beads (20 mM)51. In contrast to PMOXA-coated NPs, GlcNAc, and up to 100 mM, did not inhibit the binding of FCN2 to PEOXA-coated NPs. This could indicate that FCN2 has a stronger affinity for PEOXA compared with PMOXA. The pattern of FCN2 binding inhibition to PMOXA-coated NPs by GlcNAc was further validated by western blot and SDS-PAGE (Supplementary Fig. 14).

To further elaborate on the mode of FCN2 binding to PMOXA and PEOXA-coated NPs, we used a library of small-molecule amides resembling the chemical structure of the monomeric units in PMOXA and PEOXA for competition studies (Fig. 4e, f). SDS-PAGE analysis showed that both N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMNAc), mimicking the PMOXA monomer, and N,N-dimethylpropionamide (DMNPr), mimicking the PEOXA monomer, inhibited FCN2 binding to PMOXA-coated NPs, without affecting the binding of other proteins at 100 mM. Higher quantities of both DMNAc and DMNPr (300 mM) were necessary to inhibit the binding of FCN2 to PEOXA-coated NPs. Amides with structures gradually diverging from the original PMOXA and PEOXA units (N,N-dimethylformamide, DMNF; n-methylformamide, MNF; formamide, NF) showed small or no inhibitory activity. These observations indicate that DMNAc and DMNPr could occupy the S2 site on FCN2, thereby preventing its association with both PMOXA and PEOXA chains on NPs. Consistent with previous observations obtained with GlcNAc, the variable inhibitory activities of the tested amides also suggest that FCN2 has a stronger affinity for PEOXA than for PMOXA on NP surfaces. This suggestion is experimentally supported, since half-saturation of the FCN2 binding to PEOXA-coated NPs is achievable at a PS concentration ~7 times lower (9.7% v/v) compared with PMOXA-coated NPs (72% v/v) (Supplementary Fig. 15).

Since FCN2 can trigger complement activation through the lectin pathway, next we assessed the effect of FCN2 inhibitors on complement responses towards PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs in PS by TMT shotgun proteomics52. First, in agreement with SDS-PAGE analysis, GlcNAc, DMNAc, and DMNPr at 100 mM inhibited FCN2 binding to PMOXA-coated NPs, while higher concentrations (300 mM) of DMNAc and DMNPr were necessary to suppress FCN2 binding to PEOXA-NPs. Second, GlcNAc, DMNAc and DMNPr did not affect the overall characteristic of the NP protein corona, and only partially reduced the recruitment of immunoglobulins, C1, C4, Factor H, properdin and C3 on PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs (Fig. 5a, b, Supplementary Figs. 16, 17, Supplementary Data 12, 13). Importantly, C3b/iC3b opsonization was not affected by FCN2 inhibitors (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Data 14) and further validated by SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis (Supplementary Fig. 18). Thus, C3 opsonization of NPs proceeds effectively when FCN2 binding is inhibited.

a TMT shotgun analysis of the effect of GlcNAc (100 mM) and DMNAc (100 mM) on the proteome of PMOXA-coated NPs incubated in PS. The graphs represent identified proteins in order of % increasing abundancy in agonist-treated NPs relative to control NPs. FCN2 (green) and major complement proteins (blue) are indicated. Source data are provided as Source Data file. b Analysis of the amount of indicated proteins bound to PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs, identified by TMT shotgun proteomics after incubation in PS in the presence of the indicated agonists, expressed as % of controls. GlcNAc, Man, and Gal were used at 100 mM concentration; EDTA was 10 mM. DMNAc and DMNPr were used at the concentration of 100 mM with PMOXA-coated NPs and at the concentration of 300 mM with PEOXA-coated NPs. The data shown is the mean ± range (n = 2). Source data are provided as Source Data file. c TMT-based relative quantification of total C3, C3b, and iC3b bound to PMOXA-coated NPs, using fragment-specific peptide markers (see scheme), after incubation in PS in the presence of GlcNAc and DMNAc (100 mM). Data were the mean ± range (n = 3). Differences with controls were not significant (p > 0.05) as determined by two-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple comparison tests. Source data are provided as Source Data file. d, e Effect of sugar and amide FCN2 inhibitors on NP uptake by pig phagocytes NPs. NPs were pretreated with PS alone or in the presence of indicated agonists (GlcNAc and Man 100 mM for both PMOXA-NPs and PEOXA-NPs; DMNPr and DMNAc 100 mM for PMOXA-NPs and 300 mM for PEOXA-NPs), for 20 min at 37 °C. NPs were washed and further incubated in sera and agonist-free RPMI with pig macrophages (d) and pig monocytes (e). After 3 h cells were washed and analysed by FACS. NPs uptake was based on normalized MFI and expressed as % of control cells (Ctr; no agonists). GlcNAc N-acetyl-d-glucosamine, Man mannose, DMNPr N,N-dimethylpropionamide, DMNAc N,N-dimethylacetamide. Values are means ± SD (macrophages, n = 5 independent experiments; monocytes n = 4–8 independent experiments. Significant p values (<0.05), calculated by two-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple comparison test. f, g Data represent uptake of PMOXA-coated NPs by human macrophages and monocytes, respectively (G) in the presence of HS with and without the indicated agonists (100 mM). Values are MFI means ± SD (macrophages, n = 12 independent experiments, monocytes n = 6 independent experiments). Significant p values (<0.05), calculated by two-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple comparison tests. Source data are provided as Source Data file.

The role of FCN2 on NP uptake by porcine and human phagocytes

GlcNAc and DMNAc did not significantly affect the uptake of PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs by porcine macrophages in the presence of PS, while DMNPr partially reduced the uptake of PMOXA-coated NPs (~35% inhibition) (Fig. 5d). A similar pattern was observed when porcine cells were incubated with HS (Supplementary Fig. 19A). On the contrary, the uptake of PMOXA-coated NPs by pig monocytes was significantly reduced in the presence of 100 mM GlcNAc (~60% inhibition), while the association of PEOXA-coated NPs was unaffected (Fig. 5e). DMNAc and DMNPr at 100 mM also strongly reduced (~60 and ~50% inhibition) the internalization of PMOXA-coated NPs by pig monocytes (Fig. 5e). However, among the tested inhibitors, only DMNPr partially inhibited the uptake of PEOXA-coated NPs by the pig monocytes. Sugar and amide FCN2 antagonists had no effect on the uptake of PMOXA-NPs and PEOXA-NPs by pig monocytes after pre-treatment with HS as control (Supplementary Fig. 19B). On the other hand, the uptake of PMOXA-coated NPs by both human macrophages and monocytes was slightly affected by FCN2 antagonists in the presence of HS (Fig. 5f, g). FCN2 inhibitors affected the binding of PMOXA and PEOXA-coated NPs also to pig blood polymorphonuclear granulocytes and to lymphocytes in the presence of PS (Supplementary Fig. 20).

Thus, while with porcine macrophages, the situation is very similar to the human macrophages, where both PMOXA-coated and PEOXA-coated NP uptake is Ca2+- and complement-dependent, NP uptake by pig monocytes is to a large extent FCN2-dependent. As shown before, compared with pigs, where no FCN3 is present, FCN isoforms in the NP proteome of human sera show inter-subject variability but exclusive to FCN3 and FCN2. When human FCN2 is detected in the NP proteome, contrarily to FCN3, the levels are higher compared with FCN3. However, the abundance of FCN2 in HS-derived proteome is lower when compared with that of pig FCN2.

Next, we verified that purified human FCN3 weakly binds to either PMOXA- or PEOXA-coated NPs at concentrations up to 10 µg/mL (Supplementary Fig. 21A). On the other hand, dose escalation experiments showed that purified human FCN2 binds with a higher affinity to PEOXA- than to PMOXA-coated NPs (Supplementary Fig. 21B). Consistently the binding of purified human FCN2 to PMOXA-coated NPs was inhibited by 100 mM GlcNAc and DMNPr (but not by Man), whereas the binding to PEOXA-coated NPs was inhibited only by 300 mM DMNPr (Supplementary Fig. 21C). Shot-gun proteomics (Fig. 6a, b, Supplementary Fig. 22, and Supplementary Data 9) also showed that FCN2 is found in larger amount in HS-derived PEOXA-coated NP proteome compared with PMOXA-coated NP proteome. Furthermore,100 mM GlcNac and 100 mM DMNAc prevented the binding of FCN2 to PMOXA-NPs, while 300 mM DMNAc and 300 mM DMNPr prevented the binding of FCN2 to PEOXA-NPs, in appropriate HS samples. FCN2 binding inhibition did not affect the proteome composition, particularly the major opsonin C3, and other complement proteins. We conclude that pig and human FCN2 selectively recognize PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs in a similar manner.

a, b Relative amount of FCN2, immunoglobulins (Ig), and major complement proteins identified in the corona of PMOXA- (a) and PEOXA-coated NPs (b) following incubation in HS from different donors. NPs were incubated with HS at 37 °C in the absence or in the presence of GlcNAc (100 mM), N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMNAc) (100 mM with PMOXA- and 300 mM with PEOXA-coated NPs) and N,N-dimethylpropionamide (DMNPr) (300 mM). Data were the % mean ± range (n = 2) of controls. Values above 200% and below 50% of controls were marked with a star (*). Source data are provided as Source Data file. c SDS-PAGE analysis of the effect of free PMOXA and PEOXA polymers on FCN2 binding to PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs. Left panels: representative gels showing the SDS-PAGE proteome pattern of the PMOXA-coated in PS in the presence of increasing levels of free PMOXA or PEOXA. FCN2 is indicated by a green arrow. Right panels: after silver staining and densitometry, the intensities of the 38 kDa band (FCN2) were determined and represented as % of controls (no polymer). Data from three independent experiments were interpolated with logistic curves to obtain indicated IC50%s. Source data are provided as Source Data file.

Multivalence binding of polyoxazolines to FCN

Next, we investigate the interaction between FCN2 and PMOXA and PEOXA in soluble form. Free PEOXA effectively and selectively prevented FCN2 binding to both PMOXA-coated and PEOXA-coated NPs in PS with a relatively low half-inhibitory concentration (IC50%) of 0.22 and 1.0 μM, respectively (Fig. 6c). Free PMOXA reduced FCN2 binding to PMOXA-coated NPs with an IC50% of ~1.0 mM, but had no effect on PEOXA-coated NPs (up to 10 mM). PEG, as a control polymer, showed no effect on FCN2 binding to PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs in PS (Supplementary Fig. 23). In agreement with SDS-PAGE analysis, shotgun proteomic showed that free PEOXA prevents the binding of porcine FCN2 to PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs, but its effect on the deposition of the other proteins, including complement proteins is negligible (Fig. 7a and Supplementary Data 6). Human FCN2 binding to both PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs in HS was also inhibited by free PMOXA and PEOXA polymers, and in agreement with data obtained with purified human FCN2 (Fig. 7b, Supplementary Fig. 24, and Supplementary Data 10). Again, free polymers did not exert a considerable effect on the deposition of IgG and other key complement proteins, including the C1 complex, C4, C2, properdin, FH, and C3. We conclude that FCN2 specifically binds to the PMOXA and PEOXA coating on NPs but with a higher affinity for PEOXA than for PMOXA.

a PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs were treated as above with PS without or with the indicated concentrations of free PEOXA polymer, washed and analysed by shot-gun mass spectrometry. The abundancy of identified bound polypeptides in the abundancy order of control are shown (left panels) using IBAQs (mean of n = 4). FCN2 is indicated by a green arrow, and C3 and properdin by black arrows. Right panel: % binding of FCN2, Ig, and major complement proteins to PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs in the presence of free PEOXA. Values are mean ± SE (n = 4). Significant p values (<0.05) were determined by two-sided t-tests. Source data are provided as Source Data file. b Relative amount of FCN2 and of major complement proteins in the proteome of PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs formed in the HS from representative donors in the presence of indicated FCN2 antagonists. Graphs on the left represent the overall polypeptide abundancy distribution in the corona of NPs in control (only HS, black symbols) and in the presence of PEOXA polymer (red symbols) obtained by shotgun proteomics. Polypeptides are ordered according to their decreasing abundancy in control samples. FCN2 and MASP are indicated in green. Major complement proteins (C3, C4, and C1q) are indicated in black. The histogram on the right summarizes the % amount of relevant indicated proteins bound to NPs in the presence of free polymers, relative to controls. Data were the mean ± SE (n = 6). Significant p values (<0.05) are calculated by a two-sided t-test and are indicated by asterisks. ND not detected. Source data are provided as Source Data file. c Modeling of PMOXA and PEOXA binding to FCN2 S2 site. First sketch on the left: the binding mode of GlcNAc to the S2 binding site of human FCN2, highlighting the insertion of hydrophobic aliphatic groups into the two hydrophobic pockets present in the site. Second and third sketches on the right: pose obtained by molecular docking of PMOXA and PEOXA trimers (TMOXA and TEOXA) to the pig FCN2 S2 binding site, with suggested accommodations of the aliphatic portions of the N-acetyl and N-propionyl, respectively to hydrophobic subsites. d Effect of FCN2 binding inhibition on NPs phagocyte uptake. PEOXA- and PMOXA-coated NPs were treated with free PEOXA (0–300 µg/mL), in the presence of HS and further incubated in RPMI with human monocytes (left panel) and macrophages (right panel). After 3 h, cells were processed for FACS analysis to assess NP cell content. Data were the mean ± SD (n = 3 independent experiments). Significant p values (<0.05), calculated with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests, are indicated in the graphs. Source data are provided as Source Data file.

Multivalent interactions between polymers and FCN, as well as the greater affinity of FCN for PEOXA, was confirmed by molecular docking simulations, which showed tri-methyl-oxazoline (TMOXA) and tri-ethyl-oxazoline (TEOXA) (used as PMOXA and PEOXA analogs, respectively) could dock in the S2 domain of FCN2 via their carbonyl-linked -CH3 and CH2-CH3 appendages, respectively (Fig. 7c and Supplementary Fig. 25). The trimers accommodate with a V-shaped configuration, allowing the N-acetyl or N-propionyl of the second monomer to insert in the hydrophobic cavity holding the acetyl moiety of GlcNAc, while the N-acetyl/N-propionyl groups of a contiguous monomer interact with the other hydrophobic pocket capable of holding the C6 methylene of GlcNAc. Next, we estimated the possible influence of different functional groups (acetyl vs propionyl) on the binding of TMOXA and TEOXA to the S2 site using the Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) method. The calculated ΔG values for TEOXA (−16.2 kcal/mol) and TMOXA (−7.6 kcal/mol) results in an eightfold higher affinity of FCN2 for PEOXA than for PMOXA, and are consistent with experimental observations (Supplementary Fig. 15). This is presumably due to stronger ligand energetic stabilization at the S2 site of the longer alkyl chain in PEOXA compared with PMOXA, allowing a more extended hydrophobic contact with the protein. Molecular dynamics simulations using penta-methyl-oxazoline (penta-MOXA) and penta-ethyl-oxazoline (penta-EOXA) showed that both ligands remain stable in the S2 sites of the human FCN2 throughout the simulations (250 ns) (Supplementary Fig. 26A). This suggests the binding affinity of both ligands is in part driven by hydrophobic interactions (Supplementary Fig. 26B), which agrees with static docking simulations. Moreover, it also suggests an additional role for hydrogen bonds (Supplementary Fig. 26C). However, the hydrophobic and hydrogen bonding patterns of penta-EOXA and penta-MOXA seem different. Penta-EOXA proceeds with hydrophobic interactions through two ethyl groups and Leu145 of hFCN2, whereas penta-MOXA only interacted with a single methyl group and the same protein residue. Penta-EOXA established two hydrogen bonds with Arg122 and Ser143 through two carbonyl groups, whereas penta-MOXA formed hydrogen bonds with Asp113 and Glu147. It is interesting to note that the amino acid residues in the S2 site of FCN2 that participate in polymer interaction also stabilize physiological ligands48,49. The simulations suggest that PEOXA polymer interaction in the S2 site is characterized by lower mobility, compared with PMOXA, and consistent with the higher energetic stabilization in the site. Overall, both computational simulations support the binding of PMOXA and (more effectively) of PEOXA to the S2 site of the FCN2.

Finally, we used free PEOXA as a specific inhibitor to test the functional effect of human FCN2 as an opsonin. As expected, the internalization of both PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs by human macrophages (Fig. 7d) and lymphocytes (Supplementary Fig. 27) was either weakly or not affected by free PEOXA. On the contrary, incubation of NPs in HS in the presence of free PEOXA dramatically reduced the uptake of PEOXA-coated NPs by human monocytes (Fig. 7d). However, the monocyte uptake of PMOXA-coated NPs (which recruits much less FCN2 into its proteome), is not affected by free PEOXA. These observations indicate that in HS, when FCN2 is the prevalent NP-bound isoform, it substantially improves the recognition of PEOXA-coated NPs by monocytes.

Discussion

Here, we showed that polyoxazolination, which confers a stealthing property to NP recognition by murine phagocytes, does not protect NPs against uptake by porcine and human phagocytic cells. Therefore, polyoxazolination may not be a suitable strategy for engineering the next-generation stealth nanomedicines for human applications. These species differences were due to differences in opsonization processes. In both porcine and human sera, NPs were opsonized by ficolin and complement, whereas in murine sera these opsonization processes did not occur. With porcine and human macrophages, NP uptake was predominantly complement dependent, but with monocytes NP uptake was strongly FCN-dependent. FCN2 opsonization of NPs was highly reproducible in porcine sera, whereas in human sera, it was isoform-dependent (Fig. 8a). Importantly, the porcine model provided a platform for retracing FCN2 opsonization in the human blood, which could have been missed considering interindividual variability in human studies. The predominant role of porcine FCN2 opsonization could be a reflection of an evolutionary adaptation process to porcine-specific infections53, given the importance of ficolins in innate defenses against respiratory pathogens54,55,56. Variability of FCN2 abundancy in the human proteome of PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs might be genetically related. Indeed, the human FCN2 gene shows strong polymorphisms, influencing both plasma concentration and substrate affinity39,57. Our proteomics analysis could not differentiate FCN2 genetic variants and alleles associated with PMOXA and PEOXA-coated NPs, since the identified peptides did not overlap with known mutated regions (Supplementary Fig. 28). Ficolins are known to trigger complement activation through the lectin pathway13. Our opsonization findings might also suggest that the mode of FCN2 binding to PAOXA polymers may not result in the activation of MBL-associated serine proteases and, hence, the lectin pathway.

a In both human and pig serum, C1q is mostly involved in complement triggering and iC3b opsonin deposition on the surface of NPs. In pig serum also FCN2 is acting as a dominant opsonin (left). Functionally, FCN2 appears more relevant for the uptake of NPs by blood monocytes in pig serum, while the uptake by pig macrophages is less FCN2 and more C1q/iC3b dependent. In the HS, C1q-dependent C3 opsonization is sufficient to ensure macrophage recognition of NPs (right). However, for NP uptake by monocytes, there is interindividual variability with respect to FCN opsonization (red text). b Simplified representation of the promiscuous binding ability of FCN2, ensuring its association with both microbially-displayed GlcNAc (1) and PMOXA or PEOXA (2) due to the recognition of sugar N-acetyl or polymer N-alkyl groups by the S2 sites present in its COOH-terminal fibrinogen-like domains driven by hydrophobic interactions, and to hydrogen bonds with the –OH, -O-, and carbonyl moieties in the GlcNAc, and the carbonyls in PMOXA/PEOXA. Depiction in (3) indicates the hypothetical recognition of other PAMPs (pathogen-associated molecular patterns), DAMPs (damage-associated molecular patterns), and nanomaterial coatings by FCN2 resulting from the identification of regularly displaced aliphatic/hydrophobic and hydrogen bond-forming chemical groups. Red and black circles indicate chemical moieties forming regular patterns on FCN2 targeted molecules, involved in aliphatic and hydrogen bonds, respectively.

We identified both the methyl and the ethyl moieties of PMOXA and PEOXA as FCN2 targets, with a contribution of N-carbonyls. Two conserved hydrophobic pockets and hydrogen bond donor amino acid residues in the S2 binding site of the FCN2 facilitated this recognition. The S2 site binds N-acetylated monosaccharides present on pathogen surfaces44,47,48,49,51, but the results here suggest broader ligand specificity for FCN2. Interestingly, FNC2 paradoxically binds with higher affinity to N-propionyl moieties than N-acetyl groups. This may indicate an unrecognized ability of FCN2 to discriminate broader microbial or altered-self patterns through hydrophobic interactions. For instance, FCN2 binding to N-propionylated histones, which are released from necrotic cells58,59 is one possibility. The ability of ficolins to sense hydrogen bond-forming chemical moieties (e.g., PAOXA carbonyls) and hydrophobic patterns (Fig. 8b) could prove important to the biological performance of some polymeric nanomedicines. Notwithstanding, a better understanding of pattern-recognition mechanisms by FCNs could offer new possibilities for the design and selection of suitable polymers for the engineering of the next generation of stealth NPs. However, detailed genomic studies are needed to unravel the role of FCN polymorphism in NP opsonization and phagocytic cell responses in human subjects.

To date, FCN opsonization of NPs in human and animal sera has not received much attention, but earlier reports demonstrated that FCN2 directly induces the production of inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, by human monocytic leukemia cell line THP-160,61. Thus, considering the role of immune cells in idiosyncratic reactions to nanomedicine injection/infusion15, it is tempting to speculate whether FCN-directed NP uptake by monocytes and blood leukocytes could be a plausible contributing mechanism, and whether plasma FCN isoforms and their levels could serve as biomarkers for predicting the severity of infusion-related reactions to FCN-opsonized nanomedicines in humans. Also, by considering the involvement of complement opsonization in nanoparticle clearance by tissue macrophages, we must await availability for high-affinity porcine-specific complement inhibitors (as well as ficolin inhibitors), to assess the role of complement and ficolins in nanomedicine performance and safety in the porcine model in comparison with humans. In summary, our findings highlight species disparity in multifaceted mechanisms surrounding NP recognition and clearance by different phagocytic cells, and further warn that the stealth behavior of NPs in the widely used preclinical murine model may not necessarily translate to other preclinical models (e.g., pigs), and humans.

Methods

General materials and instruments

Chemical reagents and silica gel were from Merck and used without further purification. Water was purified using a MilliQ® water purification system. Reactions were monitored by TLC developed on 0.25 mm Merck silica gel plates (60 F254) using UV light as a visualizing agent and/or heating after staining with ninhydrin. Solvents were of laboratory reagent grade, HPLC grade, or analytical reagent grade according to the need. NMR spectra in the solution state were recorded on an AVIII 500 spectrometer (500 MHz for 1H frequency) using solvent suppression sequences. UV-Vis absorption spectra were measured on a Varian Cary 50 spectrophotometer with 1 cm path-length quartz cuvettes. MALDI spectra were recorded with an AB SCIEX MALDI TOF/TOF, and α-Cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) was used as the matrix. The hydrodynamic particle size (Dynamic Light Scattering, DLS) and Z-potential were measured with a Malvern Zetasizer Nano-S equipped with a HeNe laser (633 nm) and a Peltier thermostatic system. Measurements were performed at 25 °C in water or PBS 0.1x buffer at pH 7. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were recorded on a FEI Tecnai G12 microscope operating at 100 kV. The images were acquired with an OSIS Veleta 4 K camera. Thermogravimetric analyses (TGA) were run on 50 μL aliquots of NP suspension using a TA Q5000 IR instrument, setting a temperature program from 25 to 1000 °C (10°/min) under a continuous airflow.

Polymer synthesis and characterization

Synthesis of PMOXA and PEOXA

Polyoxazolines terminating with a primary amine (PMOXA-NH2 and PEOXA-NH2) were prepared by cationic ring-opening polymerization (CROP) of 2-methyl-2-oxazoline (MOXA) or 2-ethyl-2-oxazoline (EtOXA) according to previously reported procedures62. In brief, the desired oxazoline (about 10 g, 116 mmol, 40 eq), previously distilled on KOH, was dissolved in dry acetonitrile (25 mL) under N2 atmosphere. The resulting solution was then cooled down to 0 °C, and methyl triflate (548 mg, 2.9 mmol, 1 eq) was added as a polymerization initiator. The mixture was heated to 70 °C and kept under stirring and under an inert atmosphere for 24 h. After this time, cooling was interrupted, and the reaction was quenched by the addition of a 0.5 M NH3 solution in THF (20 mL, 10 mmol, 3.3 eq). The mixture was left under stirring at room temperature for a further 48 h and the solvent was then evaporated under reduced pressure. The crude product was eventually dissolved in a small amount of ultrapure water (MilliQ) and purified by dialysis with 1000 Da cut-off tubes. PMOXA40-NH2 and PEOXA30-NH2 were obtained as a white powder.

Synthesis of PEG2000-OMe-Si

PEG2000-OMe-Si was prepared according to previously reported procedures36. In brief, O-2-aminoethyl)-O′-methyl poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG2000-amine, 250 mg, 0.125 mmol) was dissolved in 5 mL of dry dichloromethane in a Schlenk tube. Et3N (61 µL, 0.438 mmol) and 2-(4-chlorosulfonylphenyl) ethyl trimethoxysilane (50% solution in dichloromethane, 164.5 µL, 0.25 mmol) were subsequently added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at 42 °C under N2 atmosphere for 24 h. After this time, the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in ethanol (0.3 mL), cooled to 4 °C and precipitated by addition of cold tert-butyl methyl ether (13 mL) for three times. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 4 °C. The white solid obtained was eventually dried under vacuum (70%). 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 1.00 (m, 2H), 2.82 (m, 2H), 3.11 (s, 9H), 3.38 (s, 3H), 3.64 (m, 180 H), 5.47 (m, 1H), 7.33 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.77 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H).

Synthesis of PMOXA40-Si

N-(2-aminoethyl)-poly(2-methyloxazoline) (PMOXA40-NH2, 250 mg, 0.07 mmol) was dissolved in 3 mL of dry dichloromethane in a Schlenk tube. Et3N (39 µL, 0.28 mmol) and 2-(4-chlorosulfonylphenyl) ethyl trimethoxysilane (50% solution in dichloromethane, 190 µL, 0.28 mmol) were added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at 42 °C under N2 atmosphere for 6 h. After this time, the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in ethanol (0.3 mL), cooled to 4 °C and precipitated by addition of cold tert-butyl methyl ether (14 mL) for three times. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 4 °C. The white solid obtained was dried under vacuum (92 %). 1H-NMR, (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 0.75–1.06 (m, 2H), 1.94–2.36 (m, 120H), 2.60–3.13 (m, 12H), 3.27–3.68 (m, 160 H), 7.11–7.98 (m, 4H). MALDI-MS (m/z): 3711.4 [M+Na+], 3626.4, 3796.4 [M ± 85+Na+], 3541.4, 3881.4 [M ± 170+Na+], 3456.4, 3966.4 [M ± 255+Na+], 3371.4, 4051.4 [M ± 340+Na+]. M+Na+ calc. (for n = 40) = 3712.4.

Synthesis of PEOXA30-Si

N-(2-aminoethyl)-poly(2-methyloxazoline) (PEOXA30-NH2, 200 mg, 0.066 mmol) was dissolved in 2 mL of dry dichloromethane in a Schlenk tube. Et3N (18 μL, 0.132 mmol) and 2-(4-chlorosulfonylphenyl) ethyl trimethoxysilane (50% solution in dichloromethane, 112 µL, 0.165 mmol) were added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at 42 °C under N2 atmosphere for 4 h. After this time, the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in ethanol (0.3 mL), cooled to 4 °C and precipitated by addition of cold tert-butyl methyl ether (14 mL) for three times. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 4 °C. The white solid obtained was dried under vacuum (80 %). 1H-NMR, (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 0.91 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 2.6 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 1.02 (m, 90H), 3.37 (m, 70H), 3.46 (t, 60H), 3.47 (s, 3H), 7.45 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.81 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H). MALDI-MS (m/z): 3326,7 [M+Na+], 3227.7, 3425.7 [M ± 99+Na+], 3128.7, 3524.7 [M ± 198+Na+], 3029.7, 3623.7 [M ± 297+Na+], 2930.7, 3722.7 [M ± 396+Na+]. M calc. (for n = 30) = 3323.4.

General synthesis of nanoparticles

Polymer-coated ORMOSIL NPs were prepared following a previously reported protocol10,29,37. In brief, PEG-Si, PMOXA-Si, or PEOXA-Si (0.013 mmol) and water (4.16 mL) were added to a jacketed reaction vessel connected to a thermostatic circulating bath. The temperature was set at 30 °C. Subsequently, a Brij35P water solution (833 µL, 30 mM, pH 2), n-butanol (150 µL), rhodamine-B silane (25 μL, 2.5·10−4 mmol), and vinyl-triethoxysilane (VTES, 100 μL, 0.489 mmol) were added and the mixture was vigorously stirred for 30 min. The polymerization was started by the addition of 15% aqueous ammonia (10 μL) and the mixture was stirred for two hours. After this time, the reaction mixture was filtered through a 0.45 µm membrane filter. The purification of the nanoparticles was performed by centrifugation and resuspension in MilliQ water (5 mL, 23,500×g, 30 min, three times). Purified nanoparticle suspensions in water were stored at 4 °C.

Characterization of protein binding to NPs

For shot-gun experiments and mass spectrometry analysis of protein bound to NPs, 800 µg/mL of PEGylated, PMOXA- and PEOXA-coated NPs were incubated in 60% (v/v) HS or PS for 20 min at 37 °C. Human serum was obtained from freshly drawn human blood from consented healthy volunteers in accordance with established protocols to conserve complement16,63. Briefly, after collection of the whole blood in tubes with no coagulation enhancers, the blood was allowed to clot by leaving it undisturbed at 37 °C for 30 min, the clot was then removed by centrifuging at 2000×g for 10 min. The serum was aliquoted and stored at −20 °C. The same procedures were followed for preparing pig serum.

Following incubation in serum, NPs were pelleted by centrifugation (18,000×g, 30 min, 4 °C) and washed three times with 1 mL of PBS (with or without the different inhibitors). In some experiments, different inhibitors and control chemicals were added to serum and included N-acetyl-glucosamine (GlcNAc, 100 mM), DMNPr (100 or 300 mM) or DMNAc (100 or 300 mM), mannose (Man, 100 mM), and galactose (Gal, 100 mM). For shot-gun analysis, NP pellets were treated as described earlier10. For SDS-PAGE analysis, NP pellets were dissolved in a loading buffer and loaded onto 10% acrylamide gels. Proteins were stained with silver nitrate or with colloidal Coomassie G-250 in the case of mass spectrometry analysis. In-gel digestion, protein identification, and database search of proteins bound to NPs were performed as described earlier64. For C3a analysis by Western blot, samples were prepared as described previously10: briefly, after the incubation of NPs with the different kind of sera, NPs were directly centrifuged; after the centrifugation, the supernatants were recovered and mixed with loading buffer, the pellets were washed three times, as previously described in this section. Control serum samples were treated with 25 mg/ml Zymosan (Sigma) for 30 min at 37 °C, and the reaction was blocked with 25 mM EDTA. Samples were loaded onto an 8% gel, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Biorad), and blotted against C3a antibodies (Calbiochem, 1:2000) overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were washed three times with TBS/0.1% v/v Tween 20 and treated with secondary HRP-antibodies (1:2000, Calbiochem, 204589). Proteins were detected by the Uvitec imaging system (Eppendorf). Densitometric analysis of the bands were performed using Image J software.

Cell experiments

Primary human and pig monocytes and macrophages were prepared following an established protocol described earlier10. Human buffy coats from healthy, anonymous blood donors were supplied by the Hospital of Padova Transfusion Center, after written informed consent for their use in research. No ethic approval was required in our institution for the use of buffy coat, since data were not consequent to experimentation on human beings. Pig blood was obtained from abattoirs complying with the regulation CE- N.1099/2009 (24 September 2009). Buffy coats or porcine whole blood were washed and diluted in PBS, layered (25 mL) on 15 mL Lymphoprep (Stem cell technologies), and spun at 1200×g (no brake) for 30 min. After one wash with PBS, cells were spun over a Percoll gradient (Amersham) for 30 min at 550×g with no brake. Monocyte number was assessed and cells were seeded on 24-well plates at 2 × 106 cells per well, or per coverslip glasses in case of confocal microscopy. Macrophages were differentiated from monocytes after a 7 days incubation in macrophage colony-stimulating factor (MCSF, ORF Genetics) (100 ng/mL) in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) containing 20% (v/v) fetal calf serum, FCS, (Euroclone, endotoxin <0.3 EU/mL), and antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin, Euroclone).

For confocal and FACS analysis, NPs (800 µg/mL) were pretreated with homologous sera (60% v/v) for 20 min at 37 °C and diluted ten times in preheated RPMI medium and then added to cells for 3 h at 37 °C. After washing with PBS, cells were analysed with a FACS Canto II cytofluorimeter (Becton Dickinson) supported by the FACS Diva software; data were expressed as MFI (mean fluorescence intensity) values, normalized based on the intrinsic quantum yield of different NP types and batches. For confocal analysis, endo-lysosomal acidic compartments of NP-treated cells were labeled in vivo via incubation with 75 nM Lysotracker green (Thermo Fisher) for 30 min at 37 °C. After further PBS washing, cells were inspected with a Leica SP5 confocal microscope.

In some experiments, cells were pretreated with NPs in media supplemented with EDTA (10 mM) or EGTA (10 mM) + MgCl2 (2 mM) to chelate Ca2+ or both Ca2+ and Mg2+. To prevent FCN2 association with NPs, GlcNAc (100 mM), DMNPr (100 or 300 mM), or DMNAc (100 or 300 mM) were added to the sera before the preincubation with NPs, being Man and Gal (both 100 mM) tested as negative controls. In such cases, NPs were washed with agonist-free PBS, eventually suspended in a serum-free cell culture medium, and added to cells. In other experiments, free polymers (PMOXA-pol and PEOXA-pol) were used as competitors at different concentrations (100 or 200 µg/mL) during the preincubation of NPs with sera.

Methods for LC-MS/MS analyses

Label-free approach

For all the experiments performed using a label-free strategy, the different types of NPs were incubated under the specified conditions (presence of Ca2+, Mg2+, chelating agents, GlcNAc) with serum from human, mouse, and pig donors, as detailed above. After extensive washing, NPs bound proteins were reduced, alkylated, and trypsin digested as reported10. After digestion, peptide samples were desalted on C18 cartridges (Sep-Pak, waters) following the manufacturer’s instructions and dried under vacuum. For each experiment involving the comparison of multiple conditions, all samples were treated in parallel and suspended in the same volume of 3% v/v acetonitrile (ACN)/0.1% v/v formic acid (FA) so as to obtain a theoretical concentration of 0.5 μg/μL for the most abundant sample. A volume corresponding to 1 μg of the most abundant sample was then analysed by LC-MS/MS using a nano-HPLC Ultimate 3000 (Dionex—Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled with a LTQ-Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptides were separated using a linear gradient of ACN from 3 to 40% in 40 min at a flow rate of 250 nL/min. The instrument operated in a data-dependent acquisition mode, with cycles consisting of a Full MS scan acquired in the Orbitrap (at 60,000 nominal resolution at 200 m/z) followed by MS/MS scans of the four most abundant ions acquired in the linear Ion Trap. To reduce the effect of possible carry-over, the analysis of each sample was followed by a blank injection. Raw files were searched with the MaxQuant/Andromeda software package (version 1.5.1.2) against one of the following sections of the Uniprot database: human (version Sep2020, 75,074 entries), mouse (version Sep2020, 55,471 entries), and pig (version Nov2020, 49,799 entries). Trypsin was set as an enzyme with up to two missed cleavages allowed. Carbamidomethyl Cys was set as fixed modification, while Met oxidation was set as variable modification. A false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.01 was applied at the peptide and protein level. Results were filtered to remove all contaminants and all proteins identified with less than 2 peptides. The intensity and the iBAQ parameters calculated by the software were used for the relative quantification and the comparison of protein abundances across samples, as detailed earlier10.

Tandem mass tags (TMT) approach

NPs were incubated in PS (n = 2) as detailed above. Samples were reduced, alkylated, and trypsin digested, dried under vacuum, and suspended in equal volumes of 100 mM tri-ethyl-ammonium bicarbonate (TEAB), pH 8.0. Peptides were labeled with TMT tags (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to manufacturer’s instructions. Before pooling, the labeling efficiency was evaluated for every sample by performing an LC-MS/MS analysis as specified below, except that the TMT labeling of N-term and K residues was set as a variable modification. In all cases the efficiency of labeling was above 99%, with all N-term and K residues correctly modified. Samples were pooled and the excess of TMT tags was removed by strong cation exchange (SCX) chromatography as reported in ref. 65. Peptides were eluted from the SCX cartridge using two concentrations of KCl (150 and 350 mM), desalted using C18 cartridges (Sep-Pak, Waters) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and dried under vacuum. Peptide samples (2 μg of total peptides loaded on-column for each SCX fraction) were then subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis with the same instrument specified above. Peptides were separated using a linear gradient of ACN from 3 to 40% in 90 min at a flow rate of 250 nL/min. The instrument operated in a data-dependent acquisition mode, with cycles consisting of a Full MS scan acquired in the Orbitrap (at 60,000 nominal resolution at 200 m/z) followed by MS/MS scans of the three most abundant ions acquired in the linear Ion Trap with CID fragmentation (for identification purposes) and in the Orbitrap (7500 resolution) with HCD fragmentation (for quantification purposes). Raw files were analyzed with the Proteome Discoverer software package (version 1.4, Thermo Fisher Scientific) interfaced to a Mascot search engine server (version 2.4, Matrix Science). The search was carried out against the pig section of the Uniprot database (as specified above). Trypsin was set as an enzyme with up to two missed cleavages allowed. Peptide and fragment tolerance were set at 10 ppm and 0.6 Da, respectively. Carbamidomethyl Cys and TMT labeling (N-term and K) were set as fixed modifications, while Met oxidation was set as variable modifications. A false discovery rate (FDR) was calculated by the software based on the search against a randomized database. Identified peptides were grouped into protein families according to the principle of maximum parsimony and data were filtered to account only for proteins identified with at least two unique peptides with high confidence (>99%). The intensities of TMT reporter ions were used by the software to calculate the relative abundance of proteins across the different conditions.

Analysis of SDS-PAGE separated proteins

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and bands of interest were excised and subjected to in-gel reduction, alkylation, and trypsin digestion as specified elsewhere66. LC-MS/MS analysis was performed using the same instrumental conditions specified above, applying a linear gradient from 3 to 40% in 40 min at a flow rate of 250 nL/min and a top10 instrument cycle: a Full MS scan at high resolution on the Orbitrap followed by the acquisition of MS/MS spectra in the linear ion trap under CID conditions for the ten most intense ions. Raw data files were searched using the MaxQuant software package as specified above.

Computational methods

Molecular docking

The structure of mouse (Mus musculus) FCN1 and Pig (Sus scrofa) FCN2 have been modeled by using the homology Modeling tool part of the MOE suite (version 2019.10, http://www.chemcomp.com) [Chemical Computing Group (CCG) Inc. (2020). Molecular Operating Environment (MOE). Chemical Computing Group. http://www.chemcomp.com] by using human FCN2 as template (PDB ID: 2J3O). Ligand conformations were built using the MOE-builder tool implemented in the MOE suite (version 2020.10, http://www.chemcomp.com) and were subjected to an MMFF94x energy minimization until the rmsd conjugate gradient was <0.05 kcal mol–1 Å–1. Tri-methyl-oxazoline (TMOXA) and tri-ethyl-oxazoline (TEOXA) were docked into S2 binding. A molecular docking study was performed employing the docking engine GOLD Suite (version 5.2.1, http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk)67. For each compound, 25 independent docking runs were performed and searching was conducted within a user-specified docking sphere with the Genetic Algorithm protocol and the GoldScore scoring function. The resulting docking complexes (ligand and side-chain residues within 4.5 Å) were rescored using the MM-GBSA scheme. Calculations were performed using the Prime MM-GBSA tool in the Schrodinger suite (2019–04) (Schrödinger Release 2020-4: LigPrep, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2020).

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations

These simulations were conducted using the crystallographic structure of hFCN2 in complex with GlcNAc as the initial configuration. The ligand atom types were assigned following the GAFF2 force field, while atomic partial charges were computed using the AM1-BCC method68, both implemented via the Antechamber module in AMBER 18. The simulations were executed within the AMBER 1869, employing the GAFF2 and ff14SB force fields70,71. System preparation, including topology and coordinate file generation, was carried out using the LEaP module of AMBER 18. The MD simulations were performed using the CUDA-enabled PMEMD module. Each molecular complex was solvated in an explicit water environment, placing it within a TIP3P water72 box with a 10 Å buffer region. To ensure system neutrality, explicit counterions were introduced. A two-step geometry optimization protocol was applied using PMEMD. Initially, solvent molecules and counterions were subjected to minimization under a harmonic restraint of 50 kcal·mol−1·Å−2, while in the second stage, the entire system underwent unrestrained minimization. Both steps consisted of 2500 iterations of steepest descent followed by 2500 iterations of conjugate gradient minimization. Subsequently, the systems were gradually heated from 0 to 300 K over a 2 ns period under constant pressure of 1 atm and periodic boundary conditions. During this process, harmonic restraints (10 kcal·mol−1) were applied to the solute, and temperature regulation was managed using the Andersen thermostat73. A 1-fs time step was maintained throughout the heating phase. Bond constraints involving hydrogen atoms were enforced using the SHAKE algorithm74. Long-range electrostatic interactions were treated using the particle-mesh Ewald (PME) approach75, with a real-space cutoff of 8.0 Å applied for electrostatic and Lennard-Jones interactions. Equilibration was performed over 2 ns with a 2-fs time step under constant temperature (300 K) and volume conditions. Finally, a production MD trajectory was generated for an additional 250 ns under identical simulation parameters.

Statistics

A range of statistical analyses was used. These included unpaired and paired student’s t-tests; Brown-Forsythe and Welch’s ANOVA with Dunnett’s T3 multiple comparison post hoc tests (equal SD not assumed); one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc tests (equal SD assumed) or two-way ANOVA with post hoc Šidák’s multiple comparison tests to calculate the statistical significance of means differences between groups (Software: Origin8 or Graph Pad Prism 9.0.0 statistical packages).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Source data is available for Figs. 1–7 and for Supplementary Figs. 5, 7, 10, 15–17, 19–24, 26, 27 in the associated source data file. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD058735. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Dilliard, S. A. & Siegwart, D. J. Passive, active and endogenous organ-targeted lipid and polymer nanoparticles for delivery of genetic drugs. Nat. Rev. Mater. 8, 282–300 (2023).

Papini, E., Tavano, R. & Mancin, F. Opsonins and dysopsonins of nanoparticles: facts, concepts, and methodological guidelines. Front. Immunol. 11, 567365 (2020).

Moghimi, S. M., Hunter, A. C. & Andresen, T. L. Factors controlling nanoparticle pharmacokinetics: an integrated analysis and perspective. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 52, 481–503 (2012).

Moghimi, S. M. et al. Particulate systems for targeting of macrophages: basic and therapeutic concepts. J. Innate Immun. 4, 509–528 (2012).

Shen, L. et al. Protein corona–mediated targeting of nanocarriers to B cells allows redirection of allergic immune responses. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 142, 1558–1570 (2018).

Haroon, H. B., Hunter, A. C., Farhangrazi, Z. S. & Moghimi, S. M. A brief history of long circulating nanoparticles. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 188, 114396 (2022).

West, E. E., Woodruff, T., Fremeaux-Bacchi, V. & Kemper, C. Complement in human disease: approved and up-and-coming therapeutics. Lancet 403, 392–405 (2024).

Haroon, H. B. et al. Activation of the complement system by nanoparticles and strategies for complement inhibition. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 193, 227–240 (2023).

Ricklin, D., Reis, E. S., Mastellos, D. C., Gros, P. & Lambris, J. D. Complement component C3 – The “Swiss Army Knife” of innate immunity and host defense. Immunol. Rev. 274, 33–58 (2016).

Tavano, R. et al. C1q-mediated complement activation and C3 opsonization trigger recognition of stealth poly(2-methyl-2-oxazoline)-coated silica nanoparticles by human phagocytes. ACS Nano 12, 5834–5847 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Inhibition of acute complement responses towards bolus-injected nanoparticles using targeted short-circulating regulatory proteins. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 246–254 (2024).

Norsworthy, P. J. et al. Murine CD93 (C1qRp) contributes to the removal of apoptotic cells in vivo but is not required for C1q-mediated enhancement of phagocytosis. J. Immunol. 125, 14–23 (2005).

Matsushita, M. & Fujita, T. The role of ficolins in innate immunity. Immunobiol. 205, 490–497 (2002).

Li, Y. et al. Complement opsonization of nanoparticles: differences between humans and preclinical species. J. Control. Release 338, 548–556 (2021).

Moghimi, S. M. et al. Perspectives on complement and phagocytic cell responses to nanoparticles: from fundamentals to adverse reactions. J. Control. Release 356, 115–129 (2023).

Moghimi, S. M. & Simberg, D. Critical issues and pitfalls in serum and plasma handling for complement analysis in nanomedicine and bionanotechnology. Nano Today 44, 101479 (2022).

Ogunremi, O., Tabel, H., Kremmer, E. & Wasiliu, M. Differences in the activity of the alternative pathway of complement in BALB/c and C57Bl/6 mice. Exp. Clin. Immunogenet. 10, 31–37 (1993).

Baba, A., Fujita, T. & Tamura, N. Sexual dimorphism of the fifth component of mouse complement. J. Exp. Med. 160, 411–419 (1984).

Ong, G. L. & Mattes, M. J. Mouse strains with typical mammalian levels of complement activity. J. Immunol. Method. 125, 147–158 (1989).

Woodle, M. C., Engbers, C. M. & Zalipsky, S. New amphipatic polymer-lipid conjugates forming long-circulating reticuloendothelial system-evading liposomes. Bioconjug. Chem. 5, 493–496 (1994).

Zalipsky, S., Hansen, C. B., Oaks, J. M. & Allen, T. M. Evaluation of blood clearance rates and biodistribution of poly(2-oxazoline)-grafted liposomes. J. Pharm. Sci. 85, 133–137 (1996).

Bludau, H. et al. POxylation as an alternative stealth coating for biomedical applications. Eur. Polym. J. 88, 679–688 (2017).

Wibroe, P. P. et al. Bypassing adverse injection reactions to nanoparticles through shape modification and attachment to erythrocytes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 589–594 (2017).

Brain, J. D., Molina, R. M., DeCamp, M. M. & Warner, A. E. Pulmonary intravascular macrophages: their contribution to the mononuclear phagocytic system in 13 species. Am. J. Physiol. 276, L146–L154 (1989).

Kumar, R. et al. In vivo biodistribution and clearance studies using multimodal organically modified silica nanoparticles. ACS Nano 4, 699–708 (2010).

Barandeh, F. et al. Organically modified silica nanoparticles are biocompatible and can be targeted to neurons in vivo. PLoS ONE 7, e29424 (2012).

Tavano, R. et al. Procoagulant properties of bare and highly PEGylated vinyl-modified silica nanoparticles. Nanomedicine 5, 881–896 (2010).

Roy, I. et al. Ceramic-based nanoparticles entrapping water-insoluble photosensitizing anticancer drugs: a novel drug-carrier system for photodynamic therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 7860–7865 (2003).

Rio-Echevarria, I. M. et al. Highly PEGylated silica nanoparticles: stealth nanocarriers. J. Mater. Chem. 20, 2780 (2010).

Morillas-Becerril, L. et al. Multifunctional, CD44v6-targeted ORMOSIL nanoparticles enhance drugs toxicity in cancer cells. Nanomaterials 10, 298 (2020).

Fu, J., Wu, E., Li, G., Wang, B. & Zhan, C. Anti-PEG antibodies: current situation and countermeasures. Nano Today 55, 102163 (2024).

Moghimi, S. M. & Simberg, D. Anti-poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) antibodies: from where are we coming and where are we going. J. Nanotheranostics 5, 99–103 (2024).

Verbraeken, B., Monnery, B. D., Lava, K. & Hoogenboom, R. The chemistry of poly(2-oxazoline)s. Eur. Polym. J. 88, 451–469 (2017).

Morgese, G. & Benetti, E. M. Polyoxazoline biointerfaces by surface grafting. Eur. Polym. J. 88, 470–485 (2017).

Wilson, P., Ke, P. C., Davis, T. P. & Kempe, K. Poly(2-oxazoline)-based micro- and nanoparticles: a review. Eur. Polym. J. 88, 486–515 (2017).

Rio-Echevarria, I. M. et al. Water-soluble peptide-coated nanoparticles: control of the helix structure and enhanced differential binding to immune cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 8–11 (2011).

Selvestrel, F. et al. Targeted delivery of photosensitizers: efficacy and selectivity issues revealed by multifunctional ORMOSIL nanovectors in cellular systems. Nanoscale 5, 6106–6116 (2013).

Chen, F. et al. Complement proteins bind to nanoparticle protein corona and undergo dynamic exchange in vivo. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 387–393 (2017).

Hummelshoj, T. et al. Polymorphisms in the FCN2 gene determine serum variation and function of ficolin-2. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, 1651–1658 (2005).

Jarlhelt, I. et al. Circulating ficolin-2 and ficolin-3 form heterocomplexes. J. Immunol. 204, 1919–1928 (2020).