Abstract

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)/polyethylene glycol (PEG) hydrogels, being low-cost and abundant materials, can demonstrate tremendous potential in applications requiring mechanical robustness by harnessing the enhancements afforded by a structure inspired by articular cartilage (AC). This study presents the fabrication of bioinspired PVA/PEG (BPP) hydrogel, characterized by their high mechanical strength and low friction coefficient. By utilizing a concrete-like structure composed of PVA particles and PVA/PEG fibers, the BPP hydrogel demonstrates notable properties such as high compressive strength (86%, 29.5 MPa), high tensile strength (265%, 10.5 MPa), fatigue resistance, impact resistance, and cut resistance. Moreover, under submerged conditions, it exhibits low coefficient of friction (COF) and minimal wear. The packaged hydrogel sensor demonstrates high sensitivity, high linearity, and fast response time. Ultimately, we endeavor to apply the straightforward yet competent bioinspired strategy to intelligent protective sensing equipment, showcasing extensive prospects for practical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the most promising approaches to designing synthetic hydrogels with notable mechanical properties—including strength, modulus, toughness, lubrication, and fatigue resistance—is through bioinspired structural design1,2,3,4. The most direct example is natural cartilaginous materials, composed of chondrocytes, dense type II collagen intertwined with glycoprotein matrices5,6,7,8,9,10. It reduces friction between joint surfaces during repetitive motions, possesses lubricious and wear-resistant properties, and also serves to cushion impacts and absorb shock11,12,13. By emulating natural cartilage, bioinspired hydrogel materials can be developed, with the key being an understanding of the structure-function relationship in AC. In recent decades, researchers have made profound experimental and theoretical advances in elucidating the function and performance of natural cartilage14,15. Cartilage can withstand loads up to 100 MPa, endure millions of loading-unloading cycles without significant fatigue, and rapidly recover upon unloading16,17,18. Our research team has also explored the structure and underlying mechanisms of cartilage in recent years, explaining how AC achieves its unique mechanical characteristics through a network of entangled collagen fibers and proteoglycans, which bears striking resemblance to concrete structures19,20,21.

Currently, some studies on the development of hydrogel materials have achieved significant breakthroughs in mechanical performance by using cartilage as a biomimetic model22,23,24,25. These studies have developed more complex preparation processes and more sophisticated material systems, significantly enhancing mechanical properties such as strength and modulus. In contrast, our work is inspired by the role of cartilage in dispersing pressure and dissipating energy in the human body, aiming to apply similar functions of AC to protective and sensing equipment. To achieve this, we hope to prepare hydrogel materials by mimicking the concrete-like structure of natural cartilage, finding a balance between high stiffness and flexibility. The goal is to enable these materials to function like AC when applied between rigid protective equipment and soft human skin: the outer layer of conventional protective equipment prevents damage, while the inner layer of hydrogel dissipates energy and protects the skin from injury. Thus, the mechanical properties required for the hydrogel should not be blindly focused on strength alone, but rather should be similar to those of cartilage, capable of withstanding certain loads without damage and able to buffer and absorb pressure. In addition to providing protection, the hydrogels must also possess sensing capabilities, enabling wireless data transmission and automatic alerts for excessive impact stress to seek rescue. Considering the need for commercial promotion, low-cost and simple preparation tools are required, and biocompatible raw materials are necessary for skin contact. Therefore, PVA and PEG are suitable ideal materials. Reported PVA/PEG hydrogel materials lack sufficient mechanical strength and durability under alternating loads and cyclic friction conditions, making them unsuitable for load-bearing components26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43. Given that high stiffness and high toughness are typically mutually exclusive properties, designing and fabricating ultra-strong and super-tough hydrogels at low cost using currently available, straightforward technological methods to meet the mechanical performance requirements for practical applications remains challenging.

Herein, inspired by the concrete-like architecture of natural AC, we successfully fabricated BPP hydrogel that boasts notable mechanical strength and effective lubricity. An innovative biomimetic “concrete” structure was designed, composed of a PVA/PEG fiber network and micro PVA particles. Upon tensile loading, the crystallinity of the hydrogel increased, promoting the formation of a highly compact PVA/PEG fiber network; under compressive loading, the rigid PVA particles compressed against each other to share the load collectively. The design significantly enhanced the overall tensile and compressive mechanical properties of the BPP hydrogel. This was manifested in its high compressive strength, pronounced tensile strength, durable fatigue resistance, and surface hardness comparable to that of natural cartilage. Moreover, the BPP hydrogel also exhibited notable resistance to impact and cutting. Under mixed synovial fluid conditions, its COF was exceedingly low, approximately 75% lower than that of AC. Integrating these characteristics, we compared the performance of our BPP hydrogel with that of natural cartilage and other PVA/PEG hydrogels to highlight its potential in the field of intelligent protective sensor. Ultimately, we developed an intelligent sensory protector that enables wireless detection of impacts, energy dissipation, and automatic warning emails sending, and further systematically studied its mechano-electrical coupling performance. This straightforward yet competent bioinspired strategy demonstrated broad application prospects in protective sensing equipment.

Results and discussion

Design and formation of BPP hydrogel

Our previous research has elucidated that chondrocytes and the extracellular matrix (ECM) are the two fundamental components of AC, with chondrocytes providing structure and the ECM enveloping these cells, endowing cartilage with elasticity and tensile strength20,21. The cartilage ECM structurally resembles a concrete composite (Fig. 1), consisting of collagen fibers and other ECM components. Collagen fibers act akin to rebar in concrete, while the remaining ECM, predominantly proteoglycans, is similar to the cementitious binder. The collagen fiber network forms the scaffold of the joint cartilage, with numerous proteoglycan aggregates, resembling miniature springs, embedded within this network44. These aggregates confer elasticity against compressive forces, offering mechanical protection to the joint and enabling the load-bearing function of cartilage45.

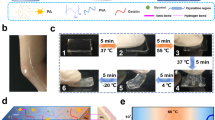

Inspired by the concrete-like structure found in the middle and deep layers of natural cartilage, we designed a convenient method for manufacturing BPP hydrogels. In this design, fibers formed from the PVA/PEG network serve as “rebars,” while partially undissolved PVA particles act as “cement.” The rigid PVA particles, together with the crystalline-enhanced PVA/PEG network, achieve multi-scale stress dispersion46,47. In brief, in a beaker, PVA and PEG were mixed in a 1:1 ratio with a small amount of deionized water added. The mixture was then heated to 80 °C and continuously stirred. Given that PEG’s solubility is higher than that of PVA, once PEG was fully dissolved, heating and stirring were stopped, leaving PVA partially dissolved. The resulting mixture was poured into molds and frozen in a refrigerator before being thawed. Subsequently, the samples were repeatedly stretched until aligned textures appeared on their surfaces. This step promoted the formation of a dual-network skeleton of PVA/PEG, interspersed with many partially undissolved PVA particles, functioning similarly to “proteoglycans” in ECM. Throughout the freeze-thaw cycles, water transformed into ice crystals, occupying volume within the hydrogel. Upon thawing, these crystals were expelled from the biomimetic hydrogel, leaving behind numerous tiny cavities that formed the network structure48. In future applications, these pores and the presence of PEG facilitate the movement and migration of cations and anions within the hydrogel, thereby enhancing the electrical conductivity of the BPP hydrogel and improving its sensing performance in smart protective equipment. The elasticity of PVA particles and the densification of the PVA/PEG fiber network fundamentally determine the hardness and load-bearing capacity of the BPP hydrogel.

Mechanical properties of BPP hydrogel

Initially, a series of mechanical property tests were conducted on PVA/PEG hydrogels of varying ratios, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. S1. Through screening of these results, the normal PVA/PEG (NPP) hydrogel with a PVA:PEG ratio of 1:1 was identified as exhibiting the most notable mechanical performance. Unless otherwise stated, all subsequent PVA/PEG hydrogels were prepared at this 1:1 ratio. Tensile testing revealed that the ultimate tensile strength (UTS) of NPP hydrogels fabricated via conventional methods was approximately 4 MPa, whereas the BPP hydrogel demonstrated enhanced tensile properties and modulus, achieving a UTS of 10.5 MPa. This value significantly surpassed that of the NPP hydrogel and exceeded the required 8.1 MPa for equivalence with natural cartilage (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Movie 1)22,49. As shown in Fig. 2b, the ultimate compressive strength (UCS) of the NPP hydrogel barely reached the lower limit of cartilage strength, indicating inadequate performance for cartilage equivalence. By simply incorporating the biomimetic concrete structure into the BPP hydrogel, we significantly augmented the UCS to 29.5 MPa, well within the cartilage equivalence range50. Additionally, durometer tests were conducted on AC, NPP, and BPP hydrogel, revealing overlapping hardness ranges, with the mean hardness of the BPP hydrogel marginally lower than cartilage, nearly achieving equivalence (Supplementary Fig. S2)51. Interestingly, post-testing examination showed clear indentation marks on AC and NPP hydrogel samples but no visible traces on the BPP hydrogel sample (Supplementary Fig. S3). The compressive modulus (0–50% strain) and tensile modulus (0–100% strain) of the fabricated hydrogels were compared with those of AC (Supplementary Fig. S2). The compressive modulus of the BPP hydrogel surpassed the mean value of the compressive modulus range for AC, while its tensile modulus reached within the equivalent range of AC. Compared to NPP hydrogel, the BPP hydrogel demonstrated a substantial improvement in strength, hardness, and modulus10. Notably, while introducing the concrete structure into PVA-PEG hydrogels elevated UTS, UCS, and hardness to cartilage equivalence levels, it reduced the tensile failure strain from 330% to 270%. Natural cartilage, in contrast, experiences a much lower tensile failure strain range of 20–30%, significantly less than that of the BPP hydrogel52. Considering a common usage scenario of protective equipment—wearing under cyclic fatigue loads—we further verified the fatigue resistance of the BPP hydrogel. Using a fatigue testing machine, the BPP hydrogel was subjected to 84% compressive strain at a frequency of 10 Hz for 28 h. After approximately 1 million cycles, the peak compressive stress decreased from about 25 MPa (85% of the unconfined compressive strength of BPP hydrogel) to 91.43% of the original value (Fig. 2c). Even after 1 million cycles, the stress–strain curves remained clear and stable, indicating notable fatigue performance. Additionally, we evaluated the long-term mechanical stability of BPP hydrogel after immersion in various conducting solutions other than deionized water, including normal saline (NaCl), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and hyaluronic acid (HA)/Plasma mixed solution. As shown in Fig. 2d, the tensile mechanical properties of the samples slightly increased after 12 hours of immersion in these liquids. Detailed evaluations of strength, modulus, and toughness are summarized in Fig. 2e. Specifically, after soaking for 12 h, the strength and modulus of samples in all three solutions increased to similar levels. In terms of toughness, PBS and HA/Plasma mixed solutions showed the most significant enhancement. This enhancement is mainly attributed to osmotic pressure effects when the hydrogel is placed in salt solutions, causing water within the hydrogel to migrate into the solution, leading to dehydration and a more compact network structure. Furthermore, according to the Hofmeister effect, which describes the influence of salt ions on polymer chain aggregation, the mechanical properties of BPP hydrogel are also affected. Normal saline, rich in Na⁺ and Cl⁻ ions, promotes PVA chain aggregation to some extent, although this effect is relatively mild. PBS primarily contains phosphate ions (PO₄³⁻) and potassium ions (K⁺), which tend to reduce polymer solubility and enhance chain aggregation, thereby strengthening the mechanical performance of BPP hydrogel53,54,55. Plasma contains a variety of ions, with higher concentrations of Na⁺, Cl⁻, and K⁺ ions, which similarly promote the aggregation of PVA/PEG chains within the BPP hydrogel. However, in solutions with low ion concentrations, the Hofmeister effect was not pronounced after short-term soaking. After 30 days of immersion, no dissolution was observed, and the effects of salting-out were more pronounced, resulting in performance changes that align with the Hofmeister effects of the respective ions (Fig. 2f). We also conducted compression tests after immersion. As shown in Fig. 2g, the compression curves of the samples immersed for 12 hours in different solutions are very similar, with UCS being higher than those of samples immersed in deionized water. This increase is primarily due to the dehydration and densification of the hydrogel under osmotic pressure. The linear relationship between the compressive modulus and stress was derived from the compression curves (Fig. 2h). To facilitate the calculation of contact stress during friction tests, we fitted the compression modulus-stress curves for samples in different solutions using appropriate functions. After 30 days of immersion, the salting-out effects of ions became fully pronounced (Fig. 2i). Samples immersed in PBS exhibited the highest UCS and compressive modulus. The performance of samples in normal saline and HA/plasma mixed solutions was similar, while the properties of samples in deionized water remained stable.

a Tensile stress–strain curves, b compressive stress–strain curves, c Compressive fatigue performance of BPP hydrogel. d Tensile curves of BPP hydrogel after soaking for 12 h. e Tensile strength, modulus, and toughness of BPP hydrogel after soaking in different solutions. f Tensile curves of BPP hydrogel after soaking for 30 days. g Compression curves of BPP hydrogel after soaking for 12 h. h Relationship between compressive modulus and stress of BPP hydrogel after soaking in different solutions. i Compression curves of BPP hydrogel after soaking for 30 days. Data in e are presented as mean values ± standard deviations (s.d.) of n = 3 replicates.

In-situ X-ray scattering and structural evolution

We characterized the structural evolution of BPP hydrogel at micro-, nano-, and molecular scales during synthesis and tensile testing, summarizing the strengthening and toughening mechanisms at both macroscopic and microscopic levels (Fig. 3). Optical image of BPP hydrogel samples revealed fibrous textures and irregular particles (Fig. 3a). In contrast, NPP hydrogels exhibited a more uniform texture (Supplementary Fig. S4a). To further investigate a partially fractured BPP hydrogel sample after tensile testing, we used laser confocal scanning microscopy (LCSM) (Fig. 3b). Even though surface cracks propagated through the sample, internal crack propagation was impeded by PVA particles, forcing cracks to deflect around these particles. LCSM observations of the network structure between particles revealed that some particles were not tightly connected but rather linked by PVA/PEG chain structures (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. S5). The width of these microscopic structures ranged from 38 μm to 182 μm, with pores distributed throughout, facilitating fluid flow. Field emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the internal structure of BPP hydrogel are shown in Fig. 3d, e, while SEM images of NPP hydrogels are presented in Supplementary Fig. S4b, c. At the microscopic level, there were significant morphological differences between BPP and NPP hydrogels. NPP hydrogels prepared via freeze-thaw cycles exhibited a single, homogeneous microstructure characterized by pores formed by melted ice crystals and a three-dimensional network created by PVA and PEG cross-linking56,57. In contrast, BPP hydrogel displayed density gradients beyond their porous and network structures (Fig. 3d). Optical photographs of BPP hydrogel showed PVA/PEG fibers aligned around PVA particles, with SEM focusing on the junctions where fibers met particles. Near the particles, a dense, thick-walled microstructure formed due to restricted pore formation, while regions farther from the particles contained fiber networks woven by PVA and PEG (Fig. 3e). This characteristic was attributed to thicker reinforcing chains resulting from PEG accumulation around PVA particles and within the network cavities. Further SEM characterization of fracture surfaces clearly showed micro-pore walls and aligned fiber remnants caused by particle spalling (Fig. 3f). Therefore, at the micro level, the introduction of a concrete-like structure increased material density through the densification of PVA particles, enhancing the material (Fig. 3g). During tensile deformation, the toughening mechanism involved the pull-out and bridging of fibrous “rebars” composed of PVA and PEG chains, as well as the blocking effect of PVA particle “cement” on crack propagation, causing deflection. During compression, the solid “cement” blocks formed by PVA particles resisted stress by mutual compression.

a Optical images of strip and circular samples. Confocal images showing b the microstructure inside the hydrogel that did not fully fracture and c the microstructure existing between PVA particles. d The SEM image showing the gradient network of the internal microstructure of the sample after tensile fracture and e a local magnified view. The inset indicates the location imaged by SEM. f The SEM image showing the microstructure of the fracture surface of the sample after tensile fracture. g Enhancement mechanism at the micrometer scale. h–j SAXS and k–m WAXS 2D patterns of BPP hydrogel during tensile testing. n The integrated spectra of 1D SAXS profiles plotted as a function of the scattering vector q. o 1D WAXS patterns of BPP hydrogel under different strains. p Azimuth integral curves of BPP hydrogel at 19° peak in WAXS diagrams under different strains. q FTIR spectra of BPP hydrogel and NPP hydrogel. r Toughening mechanism of BPP hydrogel at the molecular scale, featuring crystalline domains.

The in-situ small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) of the unstrained sample showed distinct lamellar crystal signals with a long period of approximately 30 nm (d = 2π/q) (Fig. 3h). When the tensile strain reached 100%, the lamellar crystal signals gradually disappeared, replaced by prominent fibrous crystal signals (Fig. 3i). As the strain increased, the lamellar crystal signals weakened, while the fibrous crystal signals became more pronounced and increased in size (Fig. 3j, n). In the two-dimensional (2D) patterns of in-situ wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS), it was observed that as the stretching ratio increased, the diffraction signals gradually concentrated and oriented more strongly perpendicular to the stretching direction (Fig. 3k–m). Converting the 2D WAXS patterns into one-dimensional (1D) curves, we observed that the diffraction peak near 19° became sharper and stronger, indicating that stretching promoted preferential orientation growth of the crystal planes (Fig. 3o). By calculating the azimuthal integration of this crystal plane, we observed that the orientation gradually increased, with orientation degrees of −0.00255, −0.06676, and −0.14595 (Fig. 3p). Using the Scherrer equation to calculate the grain size of the crystal planes at 19°, we obtained values of 3.5 nm, 3.1 nm, and 2.6 nm, indicating improved crystallinity during stretching. Peak fitting of the 1D integrated curves yielded crystallinity values of 0.1111, 0.24352, and 0.23607, suggesting that under lower stretching ratios, stress promoted molecular chain movement, enhancing crystallinity (Supplementary Fig. S6)53. However, as the stretching ratio increased, the crystallinity slightly decreased. We further verified the interactions between PEG and PVA using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and X-ray diffraction (XRD). As shown in Supplementary Fig. S7, the XRD pattern of pure PVA exhibited a large peak at approximately 19.4° corresponding to the (101) plane, indicating its semi-crystalline structure. For the PVA/PEG composite material, a new characteristic peak appeared at 22.5°, indicating successful incorporation of PEG chains into the PVA matrix. Figure 3q shows the FTIR spectra of the PVA/PEG composite gel. The peak at 3275 cm⁻1 corresponded to the O–H stretching vibrations of intra- and intermolecular hydrogen bonds in NPP hydrogels. In contrast, for BPP hydrogel, a red shift of the O–H bond (approximately 3255 cm⁻1) and an enhanced bending vibration peak at 3255 cm⁻¹ were observed, indicating enhanced interactions between O-H bonds. Therefore, more hydrogen bonds form between the O–H groups of PVA and PEG chains in BPP hydrogels. Additionally, the peak at 1141 cm⁻1, associated with C–O stretching vibrations in PVA molecules, undergoes significant changes during crystallization, making its intensity useful for evaluating PVA crystallinity58. The peak at this position was slightly higher in BPP hydrogel than in NPP hydrogel, suggesting that the inhibitory effect of PEG on PVA crystallization is weaker in BPP hydrogel. These results confirmed that PVA crystallizes and forms intermolecular hydrogen bonds with PEG. The increase in crystallinity during stretching strengthens each PVA/PEG fiber chain, enhancing the material’s elasticity because the crystalline domains act as rigid, high-functionality cross-linkers that retard the fracture of PVA/PEG chains (Fig. 3r). The strengthening mechanism primarily resulted from structural densification due to hydrogen bonding and crystalline domain formation.

In-situ impact and tribological tests

Due to the elasticity of the PVA particles, the BPP hydrogel exhibited notable impact resistance compared to AC and NPP hydrogels. As shown in Supplementary Movie 2, a Split Hopkinson Pressure Bar (SHPB) was used to impact a composite structure of AC, NPP hydrogel, and BPP hydrogel at a speed of approximately 4.5 meters per second driven by an air pressure of 0.07 MPa. This speed is consistent with the ground impact experienced during a ~1-m drop, reflecting real-world conditions59,60. The in-situ testing setup and principle are depicted in Supplementary Fig. S8, where the bar and sample diameters are 20 mm and 15 mm, respectively. As shown in Fig. 4a, during the impact test on AC, most of the incident wave on the incident bar was absorbed by the cartilage and returned to the incident bar. Therefore, there was only a slight decrease in voltage on the strain gauge of the transmission bar, while there was a significant increase in voltage on the strain gauge of the incident bar. During the impact test on the NPP hydrogel, it was damaged, leading to the majority of the incident wave being transmitted to the transmission bar, which resulted in a significant dip in the voltage curve on the strain gauge of the transmission bar (Fig. 4b). As shown in Fig. 4c, during the impact test on the BPP hydrogel, the voltage curves of both strain gauges were very similar to those during the cartilage test. The difference was that the voltage on the strain gauge of the transmission bar remained at zero during the impact on the BPP hydrogel, indicating no impact was transmitted to the transmission bar. This demonstrated that the BPP hydrogel could effectively absorb impact energy like AC, and even better than AC. The entire process was captured by a high-speed camera (Fig. 4d)61. The central region of the NPP hydrogel was completely penetrated, whereas AC and BPP hydrogel remained intact even under extreme compression, with BPP hydrogel exhibiting complete recovery from impact strain. But AC has only recovered 70 percent of its thickness. Moreover, an adult male, exerting full force with a single hand, failed to cut through the hydrogel samples using a blade edge, further attesting to the satisfactory strength and hardness of the BPP hydrogel (Fig. 4e). We further utilized a high-speed camera to illustrate the surface wettability of the BPP hydrogel (Supplementary Fig. S9 and Supplementary Movie 3), observing that the contact angles of water droplets (1 μL) on the hydrogels were exceedingly small, ultimately leading to their complete absorption by the hydrogels62. This indicated that the presence of hydrated PVA/PEG chains enhanced surface hydration and hydrophilicity, suggesting that as a sensor, it could maintain its own moisture and high water content for a longer period. Given the comparable performance of AC and BPP hydrogel in the SHPB impact test, we proceeded to conduct a pendulum impact test with a 5.5 J energy using the edge of the pendulum head to cut into cartilage and BPP hydrogel samples (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Movie 4). As illustrated in Fig. 4g, cartilage was seen with a significant gash incurred from the cutting process. Conversely, in Fig. 4h, no conspicuous wound was discernible on the surface of the BPP hydrogel with the naked eye. Upon closer examination using an Olympus microscope and subsequent analysis of the 3D cloud map from scanning, it was revealed that the injury on the BPP hydrogel surface was exceedingly shallow (170 μm), extending to a depth far less than that of the shallowed point of the wound in cartilage (480 μm). Under extreme conditions, the BPP hydrogel maintained its integrity without any permanent damage, even when subjected to puncture attempts using a sharp blade tip dropped from a height of 5 cm, whereas AC was readily penetrated, as depicted in Supplementary Movie 5.

Voltage changes in the strain gauges of the incident bar and transmission bar during impact on a AC, b NPP hydrogel, and c BPP hydrogel. d High-speed snapshot images showing AC and hydrogel samples impacted by the incident bar. The incident bar rebounded for the BPP hydrogel, while incident bar perforated through the NPP hydrogel. e The photographs show that the BPP hydrogel can resist cutting with a sharp knife. f Pendulum impact tester. Residual morphology of (g) the AC sample and (h) the BPP hydrogel sample after pendulum impact testing. Friction test curves of BPP hydrogel at different frequencies and different water lubricants, including i 1 Hz/NaCl, j 1 Hz/PBS, k 1 Hz/Plasma/HA, l 5 Hz/NaCl, m 5 Hz/PBS, and n 5 Hz/Plasma/HA. o Corresponding average COF of BPP hydrogel at different situations. p Reciprocating wear test of BPP hydrogel for 18,000 s. q Surface morphology of BPP hydrogel after wear. Data in o are presented as mean values ± s.d. of n = 3 replicates.

The tribological tests revealed the lubrication performance and mechanisms of BPP hydrogel. The average COF was collected using a ball-on-disk tribometer with a reciprocating sliding contact mode. The sliding distance was 5 mm, and the ball counterpart was a stainless steel ball with a diameter of 6 mm. The sliding tests were conducted at room temperature (25 °C). As shown in Fig. 4i–n, the effects of applied load, lubricant type, and sliding frequency on the lubrication performance of BPP hydrogel samples were investigated. Considering the application scenarios of hydrogel-based protective sensors, the applied loads were chosen as 1, 5, and 10 N, the frequencies were 1 and 5 Hz, and the lubricants were physiological saline (NaCl), PBS, and HA/Plasma mixture. We also calculated the contact stress under spherical-disk friction motion in three different solutions, following the formula described in the “Methods” section63,64. First, Fig. 2h depicted the E(p) curves for three compression loading curves. From these curves, an E(p) fitting function was derived, which represented the relationship between the compressive modulus and stress of the hydrogel. Ultimately, when the samples were compressed by a rigid sphere, the contact stress of the hydrogel became calculable. Typical values of normal force and the corresponding contact stress are listed in Table 1. To provide more convincing evidence, we also tested the average COF of AC against stainless steel under the same conditions as a control (Supplementary Fig. S10a–c). As a complement, we also included the friction coefficient testing of NPP hydrogel (Supplementary Fig. S11). As the tribological test time increased, the COF of BPP hydrogel tended to stabilize. With increasing applied load, the overall trend of the COF was a slight increase. The COF was higher when physiological saline was used as the lubricant compared to PBS buffer and HA/Plasma mixture, with the latter yielding the lowest COF. Under the same conditions, the COF at a sliding frequency of 5 Hz was significantly lower than at 1 Hz, which is consistent with the COF variation pattern of AC. Under all conditions, the stable COF of BPP hydrogel was lower than that of AC against stainless steel, especially when the HA/Plasma mixture was used as the lubricant. To intuitively demonstrate the tribological response of BPP hydrogel under different conditions, we calculated the average COF of BPP hydrogel samples under each condition, as shown in Fig. 4o. The above tribological phenomena can be attributed to the influence of applied load on the contact stress and deformation of BPP hydrogel. Under loads, the elastic deformation of BPP hydrogel increases significantly, allowing the lubricant stored in the internal porous structure to more easily flow to the surface, providing lubrication and maintaining a low COF. This mechanism is similar to the interstitial flow in AC51,65,66. The viscosity of the lubricant also affects its lubrication efficiency. Under the same load and frequency, the higher viscosity of the plasma/HA mixture results in the most effective lubrication on the hydrogel surface, leading to a smaller COF. Compared to normal PVA/PEG hydrogels, the BPP hydrogel exhibits greater surface hardness and microgroove structures, providing effective load-bearing capacity while allowing the surface microstructures to store a small amount of lubricant, further enhancing tribological performance. The sliding distance was fixed; consequently, a higher frequency results in faster reciprocating friction. At 5 Hz, the higher speed promoted the flow and distribution of the lubricant, facilitating the formation of a uniform lubricating film at the friction interface. This lubricating film reduced direct contact between the metal ball and the hydrogel, lowering the friction coefficient. Furthermore, considering the application scenarios of hydrogel-based protective and sensing equipment for human wear, the BPP hydrogel should maintain effective lubrication and wear resistance over long-term use. Therefore, the long-term lubrication and wear resistance of BPP hydrogel were investigated (Fig. 4p). The results showed that even after 18,000 seconds of sliding cycles, the BPP hydrogel still exhibited effective lubrication performance, indicating their notable wear resistance67. After long-term friction and wear, the surface morphology of the BPP hydrogel was characterized in three dimensions and compared with that of AC. The BPP hydrogel surface exhibited smooth grooves with a width of 416.7 μm and a depth of 68.8 μm (Fig. 4q). In contrast, the AC surface showed large-area indentations (width: 905.7 μm) accompanied by scratches with a depth of 160 μm (Supplementary Fig. S10d). Furthermore, we conducted friction stability tests on the samples after 30 days of immersion. Friction tests were performed under conditions of 1 N normal load and 5 Hz frequency (Supplementary Fig. S12a). Comparing the original results with those of fresh hydrogel samples, we observed that long-term immersion had minimal impact on the friction performance (Supplementary Fig. S12b). The type of lubricant remained the dominant factor influencing the friction behavior. Collectively, these results indicate that BPP hydrogel, due to its effective lubrication mechanisms, can maintain notable lubrication and wear resistance under continuous shear.

Performance summary and protective sensing application

Finally, we summarized the various mechanical properties of the proposed BPP hydrogel. To date, many materials based on PVA/PEG hydrogels have been developed. Despite this, most of these hydrogels typically exhibit insufficient strength and stiffness. We selected a series of hydrogels primarily composed of PVA and PEG with similar water content (BPP hydrogel: 54%) for comparison (Supplementary Table S1). Figures 5a, b compares the tensile modulus-UTS and compressive modulus-UCS of our BPP hydrogel with those of previously reported hydrogel materials26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43. Our BPP hydrogel exhibits moduli and strengths within the equivalent range of cartilage, surpassing the majority of existing synthetic hydrogels, such as PVA/PEG/BA hydrogels, SA/PVA/PEG hydrogels, PEG/PVA/PAA hydrogels, GO/PVA/PEG hydrogels, PVA/PEG/CMC hydrogels, and PVA/PEG/gelatin hydrogels, while maintaining their toughness. Mechanical properties similar to those of AC indicate that the BPP hydrogel in this study can achieve the same impact resistance and energy dissipation functions as cartilage, making them worthy of consideration for use in protective sensors. Additionally, the quantities of materials used and the number of processing steps involved in manufacturing these typical hydrogels were quantified to assess their cost-effectiveness (Fig. 5c). Clearly, the proposed BPP hydrogel offer the most cost-effective and simplest preparation method, highlighting their economic feasibility. We selected three of the most comprehensively reported PVA/PEG hydrogels for a comprehensive comparison. Overall, the BPP hydrogel proposed in this study are the most suitable for use as protective sensing devices, matching the characteristics of cartilage in terms of strength and toughness, and excelling in impact resistance, lubrication, and cost-effectiveness, thus demonstrating significant potential for commercial scalability (Fig. 5d)26,36,42.

a Property map of UTS versus tensile modulus, b property map of UCS versus compressive modulus, and c quantity map of raw materials versus processes for different kinds of PVA/PEG hydrogels. Data of other hydrogel materials were compiled from literature. d Performance comparisons of reported typical PVA/PEG hydrogels. e Real-time relative resistance change responding to cyclic compression tests with different strains (0–50%) at a fixed speed of 12 mm/min. f Fit indices of the BPP hydrogel sensor versus consecutive applied strains and forces (GF: gauge factor, R²: determination coefficient). g Cycling stability of the resistance signal of the BPP hydrogel sensor. h A prototype of an automated warning intelligent protective sensing system. i Real-time relative resistance change responding to shooting tests with different speeds.

Given the notable comprehensive performance of BPP hydrogel, we explored its application in intelligent protective equipment for special populations, such as firefighters or delivery personnel engaged in high-risk occupations. BPP hydrogel was soaked in physiological saline until swelling equilibrium was reached, enriching them with Cl- and Na+ ions, which endowed the BPP hydrogel with high electrical conductivity68. In the BPP hydrogel, PEG enhances Na+ cation transport through chain hopping, further improving the hydrogel’s conductivity. We encapsulated the BPP hydrogel as a pressure sensor using copper foil and insulating tape. When the BPP hydrogel sensor was compressed under external force, the path length for ion migration shortened, decreasing the resistance, and vice versa. As depicted in Fig. 5e, within the strain range of 0–50%, predefined strain-specific signal peak profiles could be identified, with stable detection signals and a broad operational window. The relative change in resistance was defined as ((R − R0)/R0), where R0 and R denote the initial and instantaneous resistances, respectively. Linearity, a critical metric for assessing sensor sensitivity, is particularly pertinent in advanced applications such as health monitoring devices. As illustrated in Fig. 5f, the relative change in resistance of the hydrogel sample decreased with increasing strain and force. Clearly, for responses to force and strain, corresponding linear fitting curves yielded determination coefficients (R²) for two distinct regions, both greater than 0.9868, indicating high linearity. Moreover, the gauge factor (GF), an indicator of sensitivity, fully satisfied the usage requirements. To verify the reliability of the sensor, we conducted 5500 compression tests on the BPP hydrogel sensor (Fig. 5g). The resistance signal remained clear and stable throughout the process. After 5500 cycles, the relative resistance change still maintained 90.4% of its original value. Due to the BPP hydrogel’s notable mechanical properties combined with its ability to monitor changes in electronic signals induced by mechanical deformation, we envisaged its application in intelligent protective sensing. When a significant impact force was applied to the BPP hydrogel protector, an instantaneous electrical signal was promptly displayed on the multimeter (Supplementary Movie 6). The undamaged state of the BPP hydrogel post-impact highlighted its reliable impact protection capability. Consequently, the external force could be assessed based on the electrical signal. Excessive relative resistance change indicated that the force of the impact might have exceeded the threshold of human tolerance, signifying the need for immediate rescue measures. For instance, in high-risk scenarios like riding electric scooters, installing a BPP hydrogel protector inside helmets would enable it to mitigate the impact of the hard outer shell on the head upon danger, and automatically trigger alarms in case of excessive external force indicative of bodily harm. To this end, we constructed a prototype of an automated warning intelligent protective sensing system, as shown in Fig. 5h. A simple sensor was fabricated by encapsulating BPP hydrogel with a copper sheet and electrical tape. An electromagnetic coil gun was set up to fire bullets (5.38 g) at the hydrogel sensor at varying speeds. Upon impact, the resistance value decreases as a monitoring signal. Simultaneously, the changes in the electrical signal throughout the process were detected by a smart acquisition module, which does not require external power69. The module automatically sends a warning email when a significant signal decay indicates excessive impact energy and can wirelessly transmit data to personal terminals for display. As shown in Fig. 5i, higher impact speeds result in greater energy, leading to larger decreases in the relative resistance curve. The BPP hydrogel sensor can clearly distinguish these curve characteristics. Overall, the BPP hydrogel sensor exhibits rapid response, notable stability, and high impact resistance, making it an ideal candidate for protective sensing equipment.

In summary, this work aims to balance cost-effectiveness, toughness, stiffness, strength, and conductivity, striving to achieve the most simple and efficient preparation method. By introducing a bioinspired structure from natural cartilage, we obtain a toughened BPP hydrogel. A series of microscopic characterizations revealed that the strengthening mechanism of the hydrogels under tensile force primarily resulted from the densification of the PVA/PEG network structure due to hydrogen bonding and crystalline domain formation. Ingeniously, this structural design utilized micro PVA particles as “cement” for load-bearing, while PVA/PEG fibers acted like “rebars” connecting these particles, collectively forming a system with significantly enhanced mechanical properties. Experimental outcomes demonstrated the BPP hydrogel’s notable mechanical attributes, including high compressive strength (29.5 MPa at 86% strain), high tensile strength (10.5 MPa at 265% strain), fatigue resistance (degraded by only 8.57% after 1,000,000 compression cycles), and surface hardness similar to native cartilage. Through in-situ testing techniques, we visually demonstrated the BPP hydrogel’s notable surface hydrophilicity, as well as its effective resilience against impacts and cutting. In the liquid environment, the BPP hydrogel exhibited low COF and minimal wear. This verifies its wear resistance for use in protective sensors. The sensor demonstrated high sensitivity (GF: 337), high linearity (R²: 0.9868), and fast response time (100 ms). Based on these properties, an intelligent protective sensing system has been developed, enabling wireless detection of impacts, energy dissipation, and automatic warning emails sending. Notably, compared to traditional PVA/PEG hydrogel preparation methods, our approach achieves performance enhancement without introducing any additional processing steps or materials. This work provided a straightforward yet competent bioinspired strategy for the development of hydrogel materials intended for use in protective sensing equipment.

Methods

Materials

PVA (alcoholysis degree 99%, polymerization degree 1799) was provided by Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. PEG (chemically pure, M = 2 × 104 g/mol) was provided by National Medicines Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Deionized water was used throughout the entire experiment.

Preparation of hydrogels

To prepare the BPP hydrogel, 4.0 g of PEG and 4.0 g of PVA were added to 12 g of deionized water, and the mixture was heated and stirred at 80 °C for approximately 1 h to form a solid–liquid mixture with a mass fraction of 25%. At this stage, some of the PVA did not fully dissolve, resulting in millimeter- and micrometer-sized particles. The resultant solid-liquid mixture was then poured into molds and frozen for 12 h. Due to the high viscosity of the hydrogel precursor, external force (such as squeezing or stretching) was applied to ensure the mixture completely adhered to the rectangular or circular mold. After removing the samples from the freezer, the required solutions (deionized water, normal saline, PBS, HA/plasma mixed solution) were added to the molds. The immersed samples were then placed in the refrigerator’s chilling compartment for either 12 h or 30 days of soaking and thawing processes. The extended soaking period was intended for subsequent stability testing. After completing the soaking process, the samples were removed from the molds and subjected to repetitive tensile treatments using a fatigue tester or universal testing machine until oriented fibrous textures appeared on the surface, thus obtaining BPP hydrogel with a bio-inspired concrete-like structure.

For the preparation of NPP hydrogels, 4.0 g of PEG and 4.0 g of PVA were dissolved in 12 g of deionized water under heating at 80 °C and stirring until a uniform, transparent solution formed. This solution was poured into molds and frozen for 12 h, followed by thawing for another 12 h, ultimately yielding NPP hydrogels. According to the outlined preparation method, NPP hydrogels with different compositions were systematically prepared by incrementally increasing the mass of PVA according to predetermined ratios. During the entire heating and stirring process, both hydrogel solutions were kept sealed.

Preparation of AC samples

The porcine cartilage samples used in this study were sourced from a commercial slaughterhouse. The sample collection process in the laboratory did not involve any additional handling or sacrifice of live animals, and therefore, this study does not directly manipulate experimental animals and is not classified as a life sciences study involving living subjects. Within 12 h post slaughter, the distal femur including the articular cartilage was completely sectioned using a precision medical oscillating saw (model YTZJ-B). Subsequently, punch molds were utilized to cut the cartilage into circular samples with a diameter of 1.5 cm for impact and friction testing. Cartilage from the knee joints of three freshly slaughtered adult pigs was selected as the experimental material, and friction experiments were conducted with three independent replicates.

Tension, compression, and fatigue tests

Mechanical tests, including tension tests, compression tests, and compressive fatigue measurements, were conducted on samples using both a universal testing machine (QT-1166, Quatest, China) and a fatigue testing machine (FTM7110, Suzhou cnstar equipment Co., LTD, China), each equipped with a 10,000 N load cell. Use a vernier caliper to test the length, area, and other dimensions of samples.

FTIR and XRD measurements

FTIR spectroscopy analysis of hydrogel materials was carried out using an FTIR spectrometer (Nicolet iS50, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) within a wavenumber range of 500–4000 cm⁻1. XRD measurements were executed using an X’Pert PRO instrument (Panalytical, Netherlands) over a 2θ range of 5–70°.

SEM Measurement

SEM images of hydrogel materials were acquired using a JSM-7900F Thermal Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (JEOL, Japan). Briefly, pre-prepared BPP composite hydrogel and NPP composite hydrogel underwent freeze-drying for 36 h. Subsequently, prior to the experiment, a thin gold film was sputter-coated onto the cross-section of the BPP hydrogel and the NPP hydrogel.

Contact angle measurement

The contact angle measurement was conducted through a high-speed camera (X213, Hefei Zhongke Junda Vision Technology Co., Ltd, China) at ambient temperature. The volume of tested droplets was constant at 5 μL. Each reported contact angle was an average of at least three replicate measurements of the same sample.

Tribological test

The lubrication performance of the BPP hydrogel samples was evaluated using a conventional tribometer (MS-M-9000, Lanzhou Huahui Instrument Technology Co., Ltd, China), which operated under a ball-on-disc contact mode at ambient temperature. The COF was calculated as the ratio of the tangential force opposing motion (Ff) to the normal force (FN) between the two contacting surfaces.

A stainless steel ball (316#) with a diameter of 6 millimeters served as the counterface. BPP hydrogel specimens were affixed to the base of the testing platform using a Hot-melt adhesive. Prior to testing, the hydrogel samples were fully immersed in sufficient water-based lubricant at room temperature. Friction assessments on each hydrogel surface were conducted at a frequency of 1 Hz and 5 Hz, with a sliding distance of 5 millimeters per cycle. The applied normal load ranged from 1 N, 5 N, to 10 N. Each tribological test comprised a minimum sliding duration of 600 s. The aqueous lubricants employed encompassed physiological saline, PBS at pH 7.4, and a mixture of plasma and hyaluronic acid simulating synovial fluid.

SHPB impact test

The SHPB (ZDSHTB-20/15, Zongde Electromechanical Company, China) was employed to conduct impact tests on the AC, NPP hydrogel, and BPP hydrogel samples. The impact bar, incident bar, and transmission bar all featured a diameter of 20 millimeters. Compressed air from the air pump was further compressed at the position of the air gun. Upon reaching a pressure of 0.6 MPa, the impact bar was instantaneously propelled by the compressed gas within the air gun, striking the incident bar at an approximate speed of 4.5 meters per second. Samples of AC and hydrogels, each with a diameter of 15 millimeters, were secured between the incident and transmission bars. A high-speed digital camera (X213, capable of capturing 5000 frames per second at a resolution of 1000 × 1000 pixels) was positioned at a 50 mm distance to record the thickness of the samples both before and after the impact by SHPB.

Pendulum impact test

For pendulum impact testing, an apparatus (HNB-5.5 J, Xiamen Yutesi Instrument Co., Ltd, China) was utilized, imparting an energy of 5.5 J onto the AC and BPP hydrogel samples. Subsequently, the post-test morphologies of damage on the sample surfaces were observed and analyzed through depth scanning using an Olympus microscope (LEXT OLS5100, Olympus Corporation, Japan).

Wide-angle X-ray Scattering (WAXS) and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) Measurements

Two-dimensional WAXS and SAXS profiles of the hydrogel samples were collected with an X-ray detector of Pilatus 3 R 300 K in a small-angle X-ray scattering instrument (Xeuss 2.0, Xenocs) with Cu microfocal spot X-ray source. The pixel size was 172 μm. The sample to detector distance was 84.6 mm for WAXS measurements.

Electrical measurement

Resistance signals from the flexible BPP hydrogel sensor were measured using a digital multimeter (DM858, RIGOL Technologies, Co. Ltd, China).

The measuring method of Poisson ratio of BPP hydrogel

According to a classic formula in mechanics of materials, the relation between Poisson ratio and elastic modulus is:

Where ν is the Poisson ratio, E is the elastic modulus, while K is the bulk modulus.

Bulk modulus (K) is defined as the opposite value of the stress change (Δp) divided by the volume change (ΔV), written as:

Because the volume of a material is bound to reduce when deforming, ΔV is bound to be a negative value when Δp is greater than zero. Therefore, K is a positive value.

Elastic modulus (E) is defined as the ratio of the change in stress (Δp) to the change in strain (Δε), written as:

After combining the three equations above, the Δp value could be eliminated and the following formula was derived, which applies to soft materials whose moduli are not fixed:

For cylindrical hydrogel samples, the precise strain values can be obtained using a stretching machine with a compression testing cell. When compressed to a fixed shape by the machine, the precise diameter values of the samples can be manually measured using a caliper. According to the strain and diameter values, the precise ΔV values can be manually calculated, and the ν value can then be determined using Eq. 4. The Poisson’s ratios of the BPP hydrogel measured at compressive strains of 7.7%, 23.1%, and 38.5% were 0.3898, 0.3713, and 0.3975, respectively. The average value of 0.3861 was used for the calculation of contact stress.

The calculation of ball-on-disk contact stress

For the characterization of lubricity, ball-on-disk friction tests are commonly used to measure the friction coefficients of samples. In these tests, ‘ball’ refers to the sliding probe is spherical, while “disk” means that the sample for test is fixed on a flat surface. Due to the curved contact surface, calculating the contact stress can be challenging. The classical Hertzian contact mechanics requires knowledge of the Poisson ratio and the elastic modulus of the two contacting materials, however, the Poisson ratio of hydrogels is hard to measure, and their elastic modulus often changes with stress. Therefore, this paper summarizes a calculation method proposed in previous literature to more accurately determine the maximum contact stress of hydrogels in spherical-disk friction tests.

Following the classic elastic contact theory of Hertz, the relationship between the maximum contact stress p of two spheres and the normal load F given as follow:

Where R1 and R2 are the radii of the two spheres, ν1 and ν2 are their Poisson ratios, E1 and E2 are their elastic moduli. Let the probe ball be material 1 while the flat hydrogel be material 2, since R2 value (the radius of hydrogel) approaches infinity, and the term (R1 + R2)/R1R2 simplifies to 1/R1. In ball-on-disk friction tests, when the spherical probe is rigid, the values of R1, E1, ν1 and ν2 are all fixed. Therefore, the p value could be calculated directly by a given F value as long as the E2 value is known. However, E2 (elastic modulus of hydrogel) is not constant and changes with the contact stress p. Whereas, E2 can be fitted as a function in terms of p. The function can be derived from compression test data. Thus, the equation was further transformed into:

In this formula, E2(p) is an expression for E2 in terms of p. The measuring units of F, p, R, E are respectively N, MPa, mm, MPa. Aside from the variable of F and p, the other parameters are all constant.

Example for contact stress calculation of BPP hydrogel

Figure 2h illustrates the relationship between the elastic modulus and stress of the hydrogel. According to the aforementioned Eq. (4), the average value of the Poisson’s ratio for the BPP hydrogel was measured to be 0.3861. For the probe balls, the stainless steel 316# used in this work unless specified. The radius of the ball is 3 mm. According to the internationally accepted standard, elastic modulus and Poisson ratio of the 316# stainless steel are 193 GPa and 0.3, respectively.

After substituting all of the parameters, when the measuring unit of p is MPa, the relation between F and p can be expressed as:

According to Eqs. (7), (8), (9), the contact stress p could be directly calculated from a given normal load F. The typical F values and corresponding p values are listed in Table 1 in the main text.

The calculation of water content

The BPP hydrogel samples, immediately after tensile testing, were placed on a balance, and the fresh weight Wf was recorded. Subsequently, the samples were left to dry in air at room temperature (25 °C) for 2 days, after which the dried weight Wd was re-recorded. The water content was calculated based on Eq. (10).

Based on the weights recorded in Supplementary Fig. S13, the water content of the BPP hydrogel was calculated to be ~54%.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published article and its Supplementary Information. Source data are provided in this paper. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Nian, G., Kim, J., Bao, X. & Suo, Z. Making highly elastic and tough hydrogels from doughs. Adv. Mater. 34, 2206577 (2022).

Kim, J., Zhang, G., Shi, M. & Suo, Z. Fracture, fatigue, and friction of polymers in which entanglements greatly outnumber cross-links. Science 374, 212–216 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Bioinspired footed soft robot with unidirectional all-terrain mobility. Mater. Today 35, 42–49 (2020).

Zhao, J. et al. High-strength hydrogel attachment through nanofibrous reinforcement. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 10, 2001119 (2021).

Wan, S. et al. High-strength scalable mxene films through bridging-induced densification. Science 374, 96–99 (2021).

Mao, L.-B. et al. Synthetic nacre by predesigned matrix-directed mineralization. Science 354, 107–110 (2016).

Yu, Z.-L. et al. Bioinspired polymeric woods. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat7223 (2018).

Yeom, B. et al. Abiotic tooth enamel. Nature 543, 95–98 (2017).

Yin, Z., Hannard, F. & Barthelat, F. Impact-resistant nacre-like transparent materials. Science 364, 1260–1263 (2019).

Fu, L. et al. Cartilage-like protein hydrogels engineered via entanglement. Nature 618, 740–747 (2023).

Stockwell, R. A. & Barnett, C. H. Changes in permeability of articular cartilage with age. Nature 201, 835–836 (1964).

Stockwell, R. A. Lipid in the matrix of ageing articular cartilage. Nature 207, 427–428 (1965).

Devitt, B. M., Bell, S. W., Webster, K. E., Feller, J. A. & Whitehead, T. S. Surgical treatments of cartilage defects of the knee: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Knee 24, 508–517 (2017).

Kumar, P. et al. Role of uppermost superficial surface layer of articular cartilage in the lubrication mechanism of joints. J. Anat. 199, 241–250 (2001).

Becerra, J. et al. Articular cartilage: structure and regeneration. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 16, 617–627 (2010).

Kerin, A. J., Wisnom, M. R. & Adams, M. A. The compressive strength of articular cartilage. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. H 212, 273–280 (1998).

McCutchen, C. W. Lubrication of joints. Br Med. J. 1, 1044–1044 (1964).

Lu, X. L. & Mow, V. C. Biomechanics of articular cartilage and determination of material properties. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 40, 193–199 (2008).

Ma, Z. et al. Full domain surface distributions of micromechanical properties of articular cartilage structure obtained through indentation array. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 17, 2259–2266 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Full regional creep displacement map of articular cartilage based on nanoindentation array. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 9, 3546–3555 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Water loss and defects dependent strength and ductility of articular cartilage. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 21, 1714–1723 (2022).

Yang, F. et al. A synthetic hydrogel composite with the mechanical behavior and durability of cartilage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2003451 (2020).

Zhao, J. et al. A synthetic hydrogel composite with a strength and wear resistance greater than cartilage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2205662 (2022).

Ritchie, R. O. The conflicts between strength and toughness. Nat. Mater. 10, 817–822 (2011).

Gong, J. P. Materials science. materials both tough and soft. Science 344, 161–162 (2014).

Cui, L. et al. PVA-BA/PEG hydrogel with bilayer structure for biomimetic articular cartilage and investigation of its biotribological and mechanical properties. J. Mater. Sci. 56, 3935–3946 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Construction of porous sponge-like PVA-CMC-PEG hydrogels with pH-sensitivity via phase separation for wound dressing. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 69, 505–515 (2020).

Hu, O. et al. An antifreezing, tough, rehydratable, and thermoplastic poly(vinyl alcohol)/sodium alginate/poly(ethylene glycol) organohydrogel electrolyte for flexible supercapacitors. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9, 9833–9845 (2021).

Mehrjou, A., Hadaeghnia, M., Namin, P. E. & Ghasemi, I. Sodium alginate/polyvinyl alcohol semi-interpenetrating hydrogels reinforced with PEG-grafted-graphene oxide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 263, 130258 (2024).

Xu, B. et al. Self-assembly of MoS2 nanoflakes contributing to continuous porous hydrogel for high-rate flexible zinc battery. J. Energy Storage 85, 110941 (2024).

Cai, J. et al. Polyethylene glycol grafted chitin nanocrystals enhanced, stretchable, freezing-tolerant ionic conductive organohydrogel for strain sensors. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 155, 106813 (2022).

Charron, P. N., Braddish, T. A. & Oldinski, R. A. PVA-gelatin hydrogels formed using combined theta-gel and cryo-gel fabrication techniques. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 92, 90–96 (2019).

Jafari Jezeh, A. et al. Liposomal nanocarriers-loaded poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA)/Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) hydrogels: physico-mechanical properties and drug release. J. Polym. Environ. 31, 5110–5125 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. A Bi-Layer PVA/CMC/PEG hydrogel with gradually changing pore sizes for wound dressing. Macromol. Biosci. 19, 1800424 (2019).

Zhang, W., Ma, X., Li, Y. & Fan, D. Preparation of smooth and macroporous hydrogel via hand-held blender for wound healing applications: in vitro and in vivo evaluations. Biomed. Mater. 15, 055032 (2020).

Lu, X. et al. Bentonite reinforced tough composite hydrogels as potential artificial articular cartilage. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 34, 1028–1034 (2018).

Ran, P. et al. On-demand bactericidal and self-adaptive antifouling hydrogels for self-healing and lubricant coatings of catheters. Acta Biomater. 186, 215–228 (2024).

Bhattacharya, P. et al. Acceleration of wound healing By PVA-PEG-MgO nanocomposite hydrogel with human epidermal growth factor. Mater. Today Commun. 37, 107051 (2023).

Zewail, T. M. M., Saad, M. A., AbdelRazik, S. M., Eldakiky, B. M. & Sadik, E. R. Synthesis of sodium alginate / polyvinyl alcohol / polyethylene glycol semi-interpenetrating hydrogel as a draw agent for forward osmosis desalination. BMC Chem. 18, 134 (2024).

Branco, A. C. et al. PVA-based hydrogels loaded with diclofenac for cartilage replacement. Gels 8, 143 (2022).

Cao, J., Meng, Y., Zhao, X. & Ye, L. Dual-anchoring intercalation structure and enhanced bioactivity of poly(vinyl alcohol)/graphene oxide-hydroxyapatite nanocomposite hydrogels as artificial cartilage replacement. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59, 20359–20370 (2020).

Meng, Y., Ye, L., Coates, P. & Twigg, P. In situ cross-linking of poly(vinyl alcohol)/graphene oxide-polyethylene glycol nanocomposite hydrogels as artificial cartilage replacement: intercalation structure, unconfined compressive behavior, and biotribological behaviors. J. Phys. Chem. C 122, 3157–3167 (2018).

Zhang, Z. et al. Flexible hybrid wearable sensors for pressure and thermal sensing based on a double-network hydrogel. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 6, 5114–5123 (2023).

Stockwell, R. A. & Scott, J. E. Distribution of acid glycosaminoglycans in human articular cartilage. Nature 215, 1376–1378 (1967).

Sophia Fox, A. J., Bedi, A. & Rodeo, S. A. The basic science of articular cartilage: structure, composition, and function. Sports Health 1, 461–468 (2009).

Steck, J., Kim, J., Kutsovsky, Y. & Suo, Z. Multiscale stress deconcentration amplifies fatigue resistance of rubber. Nature 624, 303–308 (2023).

Zhang, G., Kim, J., Hassan, S. & Suo, Z. Self-assembled nanocomposites of high water content and load-bearing capacity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 119, e2203962119 (2022).

Maroudas, A. & Bullough, P. Permeability of articular cartilage. Nature 219, 1260–1261 (1968).

Kempson, G. E., Freeman, M. A. & Swanson, S. A. Tensile properties of articular cartilage. Nature 220, 1127–1128 (1968).

Grodzinsky, A. J., Lipshitz, H. & Glimcher, M. J. Electromechanical properties of articular cartilage during compression and stress relaxation. Nature 275, 448–450 (1978).

Ye, Z. et al. Glycerol‐modified poly(vinyl alcohol)/poly(ethylene glycol) self‐healing hydrogel for artificial cartilage. Polym. Int. 72, 27–38 (2023).

Sasazaki, Y., Shore, R. & Seedhom, B. B. Deformation and failure of cartilage in the tensile mode. J. Anat. 208, 681–694 (2006).

Hua, M. et al. Strong tough hydrogels via the synergy of freeze-casting and salting out. Nature 590, 594–599 (2021).

Liu, D. et al. Tough, transparent, and slippery PVA hydrogel led by syneresis. Small 19, 2206819 (2023).

Wu, S. et al. Poly(vinyl alcohol) hydrogels with broad-range tunable mechanical properties via the hofmeister effect. Adv. Mater. 33, 2007829 (2021).

Zhang, H. & Cooper, A. I. Aligned porous structures by directional freezing. Adv. Mater. 19, 1529–1533 (2007).

Qian, L. et al. Systematic tuning of pore morphologies and pore volumes in macroporous materials by freezing. J. Mater. Chem. 19, 5212–5219 (2009).

Wang, Y.-L., Yang, H. & Xu, Z.-L. Influence of post-treatments of porous poly(vinyl alcohl) membranes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 107, 1423–1429 (2008).

Liang, X. et al. Impact‐resistant hydrogels by harnessing 2d hierarchical structures. Adv. Mater. 35, 2207587 (2023).

Radin, E. L. & Paul, I. L. Failure of synovial fluid to cushion. Nature 222, 999–1000 (1969).

Li, C. et al. Development of an in-situ current-carrying friction testing instrument and experimental analysis under the background of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Mech. Syst. Signal Proc. 223, 111936 (2025).

Zhao, S. et al. Golden section criterion to achieve droplet trampoline effect on metal-based superhydrophobic surface. Nat. Commun. 14, 6572 (2023).

Liu, H. et al. Robust super-lubricity for novel cartilage prototype inspired by scallion leaf architecture. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2310271 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Durable hydrogel-based lubricated composite coating with remarkable underwater performances. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 654, 568–580 (2024).

Grant, C. et al. Poly(vinyl alcohol) hydrogel as a biocompatible viscoelastic mimetic for articular cartilage. Biotechnol. Progr. 22, 1400–1406 (2006).

Krishnan, R., Park, S., Eckstein, F. & Ateshian, G. A. Inhomogeneous cartilage properties enhance superficial interstitial fluid support and frictional properties, but do not provide a homogeneous state of stress. J. Biomech. Eng. 125, 569–577 (2003).

Yan, C., Chen, J., Jia, Z. & Li, Z. Organization structure and tribological study of hydrogel prepared by Uv light molding and casting molding methods for bionic articular cartilage. Mater. Res. Express 10, 045303 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Multimodal and flexible hydrogel-based sensors for respiratory monitoring and posture recognition. Biosens. Bioelectron. 243, 115773 (2024).

Liu, J., Zhao, W., Ma, Z., Zhao, H. & Ren, L. Self-powered flexible electronic skin tactile sensor with 3D force detection. Mater. Today 81, 84–94 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2023YFF0716800, Z.M.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 92266206, Z.M. and No. 52227810, Z.M.), Jilin Province Science and Technology Development Plan (No. YDZJ202101ZYTS129, Z.M.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. and Z.M. conceived the research and designed the experiments. J.L. carried out the experiments. J.L. and W.Z. prepared the samples and analyzed the data. J.L. wrote the manuscript with input from the other authors. Z.M. and W.Z. examined and polished the manuscript. Z.M., H.Z. and L.R. supervised the research. All authors contributed to the interpretation and drafting of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Xiaolong Wang, Dekun Zhang, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Zhao, W., Ma, Z. et al. Cartilage-bioinspired tenacious concrete-like hydrogel verified via in-situ testing. Nat Commun 16, 2309 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57653-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57653-5

This article is cited by

-

Hierarchically structuralized hydrogels with ligament-like mechanical performance

Nature Communications (2025)