Abstract

Porphyry-type Cu (Mo, Au) deposits are among the economically most important ore resources. The depth and mode of ore-forming fluid exsolution from their source magmas has remained poorly constrained. Here, we studied 36 magmatic rocks from six mineralized systems in the Sanjiang region of southwestern China. Melt inclusions trapped in the phenocrysts of mineralizing, felsic magmas are strongly depleted in Cl, S, and metals. Petrographic evidence, apatite volatile contents, and mass balance calculations suggest that this depletion was caused by the exsolution of aqueous fluids, which extracted 63‒97% of the Cl, S, and metals originally present in the magmas. Three independent geobarometers reveal that all the major phenocrysts in the felsic magmas crystallized within the pressure range of 0.3‒0.5 GPa. These results show that the ore-forming fluids exsolved from magmas that crystallized at mid- to upper crustal depths of ~10‒20 km, rather than from magmas crystallizing entirely within the upper crust or from magmas directly ascending from the lower crust. The fluids thus had to transport their metal and S endowments over a vertical distance of ~10 km to the site of ore precipitation, likely first via bubbles suspended in ascending porphyry magmas, and then through an interconnected fluid network.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Porphyry-type Cu (Mo, Au) deposits provide ~75% of the world’s Cu, and considerable amounts of Mo and Au (ref. 1). Ore formation at crustal depths of a few kilometers is the product of multiple processes, which involve (1) partial melting of hydrated upper mantle, (2) crustal differentiation of mafic arc magmas, (3) exsolution of metal- and S-bearing, saline aqueous fluids from intermediate to felsic magmas, (4) emplacement of porphyry stocks or dikes that subsequently serve as fluid pathways, and (5) hydrothermal evolution and ore precipitation2,3,4.

Based on the high Sr/Y signature of Cu-mineralized porphyries, high-pressure differentiation of mafic arc magmas in the lower crust is recognized as a critical prerequisite for the formation of intermediate to felsic, fertile magmas5,6. However, the site and mode of ore-forming fluid exsolution from the fertile magmas are still a matter of debate (e.g., see discussions in refs. 4,7). In the traditional model, fertile magmas accumulate in the upper crust to form large magma reservoirs, which, upon further fractionation, contribute porphyry magmas and fluids for the overlying porphyry Cu systems1,2,3,8,9,10. The large magma reservoirs have been postulated to be located at depths of 5‒15 km (ref. 1), but only very few quantitative data exist, and these rather suggest depths of only 4–10 km (refs. 8,11,12,13,14; Supplementary Table 1). On the other hand, some recent models propose that the ore-forming fluids start to exsolve already at lower- to mid-crustal depths in response to the ascent of fertile magma from the lower crust and that no large, upper crustal magma reservoirs exist at the time of mineralization5,6. Irrespective of these different models, the mechanism of fluid transfer from the source magma to the site of ore formation is not well understood4,15.

Melt inclusions, which are tiny droplets of silicate melt trapped in growing minerals, provide a unique approach to quantify magmatic volatile and metal contents before and after fluid exsolution, and, together with mineral compositions, preserve information about magmatic pressure and temperature. However, melt inclusion studies combined with thermobarometry on mineralized magmatic systems are scarce, mostly due to the difficulty of finding suitable natural samples.

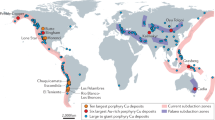

Here we report on results from the Sanjiang porphyry-skarn Cu (Au, Mo) metallogenic belt in southwestern China (Fig. 1a). The study area was chosen for the following reasons: (1) the variably evolved magmatic rocks in certain magmatic systems are clearly cogenetic, and they contain well-preserved melt inclusions16,17; (2) evolutionary systematics of H2O, S, and Cl concentrations in the residual melt during magma differentiation at high pressure have been explored experimentally17; (3) melt inclusions coexist with CO2- or H2O-rich fluid inclusions in various phenocrysts; and (4) the presence of hornblende and quartz phenocrysts in mineralized felsic porphyries allows the application of two well-calibrated, independent barometers.

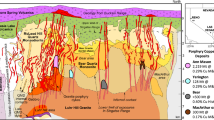

a, b The distribution of strongly mineralized felsic porphyries and weakly to non-mineralized variably evolved rocks in the Sanjiang region. The maps in (a) are modified after https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Simplified_World_Map.svg and ref. 26, and the one in (b) after ref. 80. c The distribution of intermediate to felsic rocks in the Jianchuan area. The map is modified after refs. 81,82. d, e The distribution of strongly mineralized and weakly to non-mineralized felsic porphyries in the Beiya and Yulong areas. The maps are modified after refs. 29,30, respectively. The age ranges shown in (c) to (e) are based on in-situ zircon U-Pb dates of the intermediate to felsic rocks (see age summaries in refs. 16,29).

Results and discussion

Volatile and metal concentrations in variably evolved melts

We analyzed Cl, S, and metal concentrations in a total number of 207 melt inclusions that were hosted in olivine and clinopyroxene phenocrysts of mafic rocks (trachybasaltic andesite and trachybasalt), in clinopyroxene phenocrysts of intermediate rocks (syenite porphyry and trachyte), and in quartz, plagioclase, and K-feldspar phenocrysts of felsic rocks (rhyolite tuff, monzogranite porphyry, and quartz-monzonite porphyry) (Fig. 1; Supplementary Data 1 and 2). Most of the melt inclusions were crystallized, and thus only unexposed ones were analyzed as a whole using laser-ablation inductively-coupled-plasma mass-spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS; Methods).

The Cl and S concentrations in melt inclusions analyzed from the mafic to intermediate rocks match well with the Cl and S trends observed in residual melts of the magma differentiation experiments conducted at 1.0 GPa (ref. 17), and the W, Pb, Mo, and Ag concentrations in these melt inclusions are close to theoretical trends predicted for the case of 100% incompatibility in the crystallizing minerals (Fig. 2). The S, Cu, and Au concentrations are variably depleted compared to the theoretical trends. This is likely because S, Cu, and Au are strongly compatible in magmatic sulfides that were present in intermediate melts in both the experimental and natural samples17,18. The Cl concentrations are slightly lower than the theoretical trends, which may be explained by the exsolution of early, CO2-rich fluids that could contain small amounts of Cl (ref. 19; the small amount of Cl that is incorporated into magmatic biotite has already been subtracted from the theoretical Cl trend shown in Fig. 2). This interpretation is supported by the presence of CO2-rich fluid inclusions in clinopyroxene and K-feldspar phenocrysts of the intermediate rocks (Supplementary Fig. 1), and also by the exsolution of CO2-rich fluids in magma differentiation experiments performed at 1.0 GPa (ref. 17). The presence of lower crustal, garnet-amphibolite and eclogite xenoliths in the intermediate rocks16 and clinopyroxene–liquid barometric results (Supplementary Data 3; Methods) suggest that the intermediate magmas formed through magma differentiation at pressures of ~0.5–1.3 GPa.

The stars at the top indicate bulk-rock SiO2 contents of the studied rocks, whereas the solid lines below show the ranges of SiO2 contents of melt inclusions that are color-coded to their respective host rock. Large, fully filled symbols denote LA-ICP-MS analyses. Volatile contents determined by EPMA, metal contents reconstructed from the composition of sulfide inclusions, and part of the LA-ICP-MS analyses were reported in ref. 18. Water, Cl, and S contents of the experimental melts were taken from equilibrium crystallization experiments performed at 1.0 GPa (ref. 17), which utilized a Sanjiang basaltic trachyandesite sample as starting material. The theoretical trends for 100% incompatibility were calculated based on magma crystallinities observed in the 1.0 GPa experiments, assuming that the components stay solely in the residual melt, except for H2O which was allowed to partition slightly into biotite17. Error bars show one standard deviation of multiple analyses. MI’s melt inclusions, SI’s sulfide inclusions, ol olivine, cpx clinopyroxene, qtz quartz, pl plagioclase, kfs K-feldspar, EPMA electron probe micro-analyzer.

Since the concentrations of Cl and most metals (except for Cu and Au) in the trachydacitic melt inclusions (67‒70 wt% SiO2) analyzed from the intermediate rocks are still close to the theoretical trends of 100% incompatibility (Fig. 2), we conclude that the onset of aqueous fluid exsolution was not yet reached. By contrast, the Cl, S, and metal concentrations in the rhyolitic melt inclusions (75‒78 wt% SiO2) analyzed from the felsic rocks are much lower than those in the trachydacitic melt inclusions, despite higher degree of fractionation of the former melts (Fig. 2). We interpret these trends to reflect the exsolution of Cl-, S-, and metal-rich aqueous fluids, in agreement with the presence of H2O-dominated fluid inclusions coexisting with rhyolitic melt inclusions along growth zones in plagioclase phenocrysts (Fig. 3).

a, b Coexisting H2O-rich fluid inclusions and melt inclusions along a growth zone within a plagioclase phenocryst. c, d Close-up view of plagioclase-hosted melt inclusions in the same sample. They consist mainly of glass and contain an exsolved aqueous fluid phase that is composed of about equal volumes of liquid H2O and a vapor bubble. MI melt inclusion, FI fluid inclusion.

The F, Cl, and OH contents of clinopyroxene-hosted apatite inclusions in the intermediate rocks and of plagioclase- and potassic feldspar-hosted apatite inclusions in the felsic rocks are consistent with the interpretation that the trachydacitic melts were not saturated in aqueous fluids, whereas the rhyolitic melts were saturated (Fig. 4; see Methods for a discussion about the validity of using apatite volatile contents to constrain the timing of aqueous fluid saturation). Compositions of zircon-hosted apatite inclusions from mineralized felsic porphyries20 also suggest that these magmas were saturated in aqueous fluids (Fig. 4).

Lines show modeled evolutionary trajectories of apatite volatile ratios during H2O-undersaturated (dashed line) and H2O-saturated (solid line) crystallization58. The molar XF/XCl ratio in apatite increases only during the exsolution of aqueous fluids, because the fluid-melt partition coefficient of Cl is about an order of magnitude higher than that of F (ref. 83), whereas the mineral-melt partition coefficients of Cl are slightly lower than those of F (ref. 84). The grey area represents the range of published data of zircon-hosted apatite inclusions (n = 41) from strongly mineralized felsic porphyries at Yulong, Duoxiasongduo, and Zhanaga in the Sanjiang region20. apa apatite, cpx clinopyroxene, kfs K-feldspar, pl plagioclase.

Depth and mode of fluid exsolution

The solubility of H2O in rhyolitic melts within the pressure range of 0.05‒0.50 GPa can be approximated by the equation21:

in which P is given in GPa. The high H2O contents of glassy melt inclusions in quartz phenocrysts of the Jianchuan rhyolite tuff samples18 (Fig. 2; up to 7.0‒9.3 wt% H2O) suggest that they were trapped at pressures of at least 0.26‒0.42 GPa. These are minimum values because the activity of H2O in silicate melts was suppressed by the presence of CO2 (ref. 22), which was detected by laser Raman spectroscopy in the vapor bubble of the melt inclusions. For the same rhyolite tuff samples, slightly higher pressures (i.e., 0.3–0.5 GPa) are obtained via Al-in-hornblende barometry23 (using the composition of hornblende inclusions in quartz and K-feldspar phenocrysts; Methods; Supplementary Data 4) and Ti-in-quartz barometry24,25 (using the Ti contents of quartz phenocrysts in conjunction with reconstructed temperatures and TiO2 activities; Methods; Supplementary Data 5) (Fig. 5). For all porphyry intrusions, similar pressures of phenocryst crystallization were obtained (typically at 0.3–0.5 GPa), independent of whether they are mineralized or not16,26 (Fig. 5). Notably, the good agreement between the results obtained from the three barometers within uncertainties reinforces their validity. This comparison relies only on hornblende inclusions hosted within other phenocrysts because the composition of unshielded hornblende phenocrysts is often variably reset (see Methods). Overall, the results summarized in Fig. 5 clearly demonstrate that all major phenocrysts in the felsic magmas (i.e., quartz, hornblende, plagioclase, and K-feldspar) crystallized within the pressure range of ~0.3‒0.5 GPa, some potentially even up to 0.6 GPa. The evidence from fluid inclusion petrography (Fig. 2) and apatite volatile contents (Fig. 3) explicitly suggests that the felsic magmas were saturated in aqueous fluids at such high pressures.

While all the major phenocrysts (filled symbols) crystallized in the pressure range of ~0.3‒0.6 GPa, very late-grown hornblende in the matrix and re-crystallized hornblende phenocrysts (empty symbols) returned pressures of only ~0.1‒0.2 GPa. Magma storage pressures of the Jianchuan rhyolite tuff were also obtained based on the H2O contents of quartz-hosted glassy melt inclusions. The final emplacement depth of the Yuzhaokuai stock is constrained by its proximity to the Jianchuan rhyolite tuff and the Laojunshan syenite (Fig. 1), whereas the final emplacement depths of the mineralized stocks at Yulong, Beiya, and Machangqing are based on fluid inclusion types and quartz vein textures in the ore deposits34,35. The error bars denote the estimated uncertainty of individual barometric results.

The mineralization potential of the aqueous fluids was evaluated by mass balance calculations (Supplementary Data 6), based on (1) the volatile and metal concentrations in the trachydacitic vs. the rhyolitic melt inclusions (Fig. 2) and (2) the increase in magma crystallinity between these two melt compositions. To simplify the calculations, we assumed that minimal amounts of these elements were incorporated into the crystallizing minerals (i.e., plagioclase, K-feldspar, quartz, and minor amounts of biotite, amphibole, clinopyroxene, apatite, titanite, and magnetite). This is justified by the good match between most element concentrations measured in the trachydacitic melt inclusions and the theoretical trends for 100% incompatibility (Fig. 2), except for S, Cu, and Au. The latter elements could be affected by the presence of sulfides (S also by anhydrite), but the abundance of sulfides and anhydrite in the natural intermediate to felsic magmas is extremely low (typically, only 1‒2 sulfide inclusions per 150-μm-thick section; anhydrite has been observed only sporadically). Since the mass of fluids exsolved from the felsic magma significantly outweighs the mass of potentially precipitated sulfides (~5‒10 wt% fluid vs. <<0.2 wt% pyrrhotite; Supplementary Data 6), and because sulfides that are not fully enclosed within other minerals decompose during fluid exsolution27,28, we argue that the effect of sulfides on the composition of the exsolved fluids was likely insignificant. The magma crystallinity was varied in the range of 40‒60 wt% based on the typical modal abundance of phenocrysts in the felsic porphyries (Supplementary Data 1) and the fact that their whole-rock SiO2 content matches that of the trachydacitic melt inclusions (Fig. 2).

The results shown in Fig. 6 suggest that (1) the composition of the computed fluid compares well with the composition of high-temperature fluid inclusions analyzed from the Beiya, Taohua, and Yulong deposits in the Sanjiang region and the Bingham Canyon porphyry Cu-Au(-Mo) deposit in Utah (USA; associated with potassic magmas, too) and that (2) the computed fluid extracted 63‒97% of the Cl, S, and metal inventories that were present in the trachydacitic melts. Since all this extraction occurred at depths of ~10‒20 km as monitored by Al-in-hornblende barometry, Ti-in-quartz barometry, and the H2O content of glassy melt inclusions (Fig. 5), most of the Cl, S, and metals in the felsic magmas were already partitioned into aqueous fluids before some of these magmas finally ascended to shallow depth to form the porphyry stocks (Fig. 7a). Hence, the amounts of fluids that exsolved from the shallow porphyry stocks themselves seem to have played an insignificant role in the formation of the ore deposits.

a Composition of high-temperature fluid inclusions from several mineralized systems, compared to theoretical fluid compositions computed from the volatile- and metal content of trachydacitic and rhyolitic melt inclusions in the Sanjiang region. For valid comparison, all the fluid compositions were normalized to a salinity of 10 wt% NaCl equivalent, similar to the salinity of early, intermediate-density fluid inclusions present in the Yulong and Beiya deposits31,32. Note the generally good match in element concentrations between the computed and natural fluids. The few discrepancies can be explained by the effect of additional factors on the composition of the fluid inclusions, such as (1) the depletion of S in the brine phase during vapor-brine immiscibility85; (2) the possibility of partial S, Cu, W, and Mo precipitation prior to fluid inclusion entrapment31; and (3) post-entrapment gain of Cu in quartz-hosted fluid inclusions86. The fluid inclusion data are provided in Supplementary Data 7. b Element extraction efficiencies calculated based on the compositional differences between trachydacitic and rhyolitic melt inclusions. The error bars denote propagated errors from the input values.

a Accumulation of lower-crustal, fertile magmas at the mid- to upper crustal depths of 10‒20 km, and exsolution of the ore-forming fluids at these depths during considerable crystallization of the magmas. b, c Percolation of the fluids through a transient, interconnected fluid network in the porphyry magma. Notice that the residual melt at the top of the porphyry stock has already transformed into a finely-crystallized matrix due to decompression-induced H2O loss87,88.

The same conclusion is reached if one compares the total amount of metals present in the ore deposits with the metal content of the ore-forming magmas. The volume of the mineralized porphyry stocks at Yulong and Beiya in the Sanjiang region is likely less than 10 km3, based on a typical diameter of ≤1 km (Fig. 1d, e) and a vertical extension of ~10 km (Fig. 7a). In contrast, to provide the 6.5 Mt Cu and 0.4 Mt Mo contained in the Yulong deposit29 and the 300 t Au contained at Beiya30, at least 24 ± 13 km3, 17 ± 4 km3, and 54 ± 10 km3 of magma are required, respectively, if one assumes a magma density of 2.7 g/cm3, the metal concentrations present in the trachydacitic melt inclusions (99 ± 52 µg/g Cu; 8.8 ± 2.0 µg/g Mo; 2.0 ± 0.4 ng/g Au), and the geologically unrealistic case of 100% metal extraction efficiency from the magma and 100% metal precipitation efficiency at the ore deposit level. The actually required magma volumes should be far higher, also because the metal contents of the deposits represent only the mineable reserves, which do not include mineralized rock masses below economic cutoff ore grades (0.2 wt% Cu, 0.03 wt% Mo, and 1 g/t Au), nor the ~1/3 eroded Cu-Mo orebody at Yulong29. Hence, most of the ore-forming fluid must have originated from deeper levels, i.e., from the magma reservoirs located at 10‒20 km depth (Fig. 7a).

Distance and mechanism of fluid transport

The following lines of evidence suggest that the final emplacement of felsic porphyries and the formation of orebodies occurred at much shallower depths than the exsolution of ore-forming fluids (Figs. 5 and 7a): (1) Some felsic porphyry stocks occur within only ~2 km distance to similarly-aged volcanic tuffs, with no major faults in between (Fig. 1c); (2) Quartz vein textures and fluid inclusion types31,32,33 suggest that the emplacement depths of the orebodies at Yulong, Beiya, and Machangqing are of the order of 3‒4 km (refs. 34,35); (3) Small hornblende crystals in the matrix, the rim of some hornblende phenocrysts, and hornblende phenocrysts that recrystallized in-situ give Al-in-hornblende pressures of only ~0.1‒0.2 GPa, in contrast to the typically ~0.3‒0.5 GPa recorded in hornblende inclusions within other phenocrysts and in non-recrystallized core zones of hornblende phenocrysts. Consequently, the porphyry magmas and the ore-forming fluids must have migrated up over a vertical distance of at least 10 km on average from the underlying magma reservoirs to the site of ore precipitation (Fig. 7).

Initial fluid transfer was likely in the form of bubbles suspended in rising porphyry magmas (e.g., ref. 36), where depressurization promoted additional fluid exsolution. Otherwise, it is difficult to explain the fact that the phenocryst content of some felsic porphyries is higher than the rheological lock-up crystal content in magmas37 (~50 vol.%), such as at Beiya where the entire mineralized porphyry stock including its preserved apex contains ~60 vol.% phenocrysts38,39 (Supplementary Data 1). The presence of abundant fluid bubbles likely aided the transport of the very crystal-rich magmas40.

However, the large volume of the fluids required to produce the Beiya and Yulong deposits (at least 8 ± 3 to 37 ± 22 km3, calculated based on the Cu, Mo, and Au contents of the orebodies, the composition of the computed fluid, a fluid density of 0.5 g/cm3, and 100% metal precipitation efficiency) relative to the volume of the mineralized porphyry stocks (≤10 km3) renders it very unlikely that all the fluids were transferred together with the porphyry magmas to the site of mineralization (see also refs. 4,41), but rather suggests that most of the fluids ascended after the emplacement of the magmas as stocks. The low degrees of veining and alteration in deeper parts of the mineralized porphyry stocks29,30 imply that most of the fluids percolated through an interconnected fluid network at near-solidus conditions (Fig. 7b, c). The overall high crystal fractions in the porphyry magmas likely facilitated the development of the fluid network41,42 (Fig. 7b). Continuous input of fluids from the magma reservoir could ensure the fluid network to have remained open, thereby efficiently directing the fluids toward the top of the porphyry stock.

The proposed fluid transport mechanisms may be generally applicable to porphyry-type Cu deposits worldwide, considering common reports of (1) very high phenocryst contents of syn-ore porphyry intrusions40,43,44,45 (based on the least-altered samples), which are above the rheological lock-up value of ~50 vol.%37, (2) large tonnages of ore metals and S versus small volumes of mineralized porphyry stocks or dikes1,46,47, (3) the general occurrence of orebodies at the top of porphyry stocks1,47, and (4) the little-veined and little-altered nature of roots of mineralized porphyry stocks11,12.

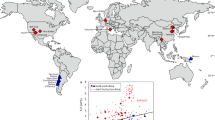

In summary, this study provides support for the classical model of porphyry Cu formation because our data clearly demonstrate that mid to upper crustal magma reservoirs existed beneath the porphyry Cu (Au, Mo) deposits in the Sanjiang region and that most of the ore-forming fluids originated from these reservoirs (Fig. 7a). However, in contrast to the few depth constraints available so far, which range up to 10 km, the magma reservoirs in the Sanjiang region were situated at depths of 10‒20 km (average 15 km), whereas the orebodies themselves were situated at depths of ca. 5 km. This means that the fluids had to ascend over a distance of ~10 km from the source region to the site of ore precipitation. Initial fluid transfer was likely in the form of bubbles suspended in the rising porphyry magma, but most of the ore-forming fluids seem to have subsequently percolated through an interconnected fluid network (Fig. 7b, c). Whereas the ore metal tonnages of the investigated systems vary by more than three orders of magnitude, the metal content (e.g., Cu, Au content) of analyzed high-temperature fluid inclusions are similar everywhere (Fig. 8). Hence, the extent of mineralization was not controlled by the metal content of the fluid, but rather by the mass of fluid exsolved from the underlying magma reservoirs, and, therefore, probably by the size of these reservoirs. Furthermore, the formation of deposits with vastly different Cu/Au ratios despite the presence of similar Cu/Au ratios in the input fluids suggests that selective metal precipitation mechanisms at the hydrothermal stage played an important role (e.g., ref. 48). A major erosion level control on the extent of mineralization in the Sanjiang porphyries can be discarded because many weakly to non-mineralized porphyry stocks occur very close to strongly mineralized ones (Fig. 1), and because the original orebodies at Beiya (Au-only) and Yulong (Cu-Mo) are largely preserved29,30.

a Cu tonnage vs. fluid Cu concentrations. b Au tonnage vs. fluid Au concentrations. The error bars denote one standard deviation. See Supplementary Data 7 for the source of the fluid inclusion data. The Cu and Au tonnages are taken from the literature (Taohua: ref. 82; Yulong: ref. 29; Beiya: ref. 30; Bingham: ref. 89).

Methods

Geologic background of the studied samples

The collision of India with the Eurasian continent triggered widespread Eocene-Oligocene potassic magmatism in the Sanjiang region along the eastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau26 (Fig. 1). Previous studies suggest that the entire range of mafic to felsic potassic magmas can be explained by differentiation of mantle-derived, potassic melts16,17. Many of the felsic, potassic porphyries (>65 wt% bulk-rock SiO2) are genetically associated with porphyry- or skarn-type Cu (Au, Mo) deposit or prospect.

We collected variably evolved potassic rocks in the Sanjiang region for petrography and in-situ geochemical microanalysis, including mafic samples from basaltic trachyandesite to trachybasalt lavas at Wozhong (n = 8), intermediate samples from syenite porphyry intrusions at Jianchuan (n = 4) and trachyte lavas at Madeng (n = 2), and felsic samples from rhyolite tuffs at Jianchuan (n = 2), and many monzogranite to quartz-monzonite porphyry intrusions at various locations (n = 20) (Fig. 1; Supplementary Data 1). At the giant Yulong porphyry(-skarn) Cu-Mo deposit, the giant Beiya skarn(-porphyry) Au-Cu deposit, the small Machangqing and Xiaolongtan porphyry(-skarn) Cu(-Mo-Au) deposits, and the Taohua and Xiejiaochong porphyry Cu-Au-Mo prospects, most samples were taken within or close to sites of mineralization. In-situ zircon U-Pb dates of variably evolved potassic rocks within a specific area are indistinguishable within the analytical uncertainty of ~1‒2 million years (refs. 16,29 and references therein; Fig. 1c–e). Based on Nd-Sr-Pb isotopic and major to trace element compositions, the mafic to felsic rocks collected in and around the Jianchuan and Beiya areas appear to have evolved from a common, mantle-derived, potassic parental melt16.

LA-ICP-MS analysis of melt inclusions and fluid inclusions

As previously described in ref. 18, we utilized two LA-ICP-MS systems to analyze melt inclusions: (1) a GeoLas-Pro 193 nm ArF Excimer laser coupled with an Elan DRC-e quadrupole ICP-MS hosted at the Bavarian Geoinstitute (BGI), University of Bayreuth, Germany; (2) the same type of laser coupled with an Agilent 7900 quadrupole ICP-MS hosted at the Institute of Geological Sciences, University of Bern, Switzerland. The latter system has a much stronger detection capacity and was thus particularly used to analyze Au and Ag concentrations in relatively large melt inclusions, and Cl concentrations in rhyolitic melt inclusions. Unexposed, individual melt inclusions were drilled out as a whole, together with part of the adjacent host mineral49. The laser systems were operated at an ablation frequency of 6–10 Hz with an energy density of 3–10 J/cm2 on the sample surface. The laser beam size was adjusted in the range of 16‒90 μm, depending on the inclusion size, such that it ultimately covered the entire inclusion volume but included as little host mineral as possible. The ICP-MS systems were tuned to a ThO rate of 0.10 ± 0.05 % and a rate of doubly-charged 42Ca ions of 0.25 ± 0.05 % based on measurements of NIST SRM610 and 612 glasses. GSE-1G, GSD-1G, NIST SRM610, or Armenia rhyolite glass was used as external standard for most elements, whereas either an afghanite or a scapolite standard was used for quantifying S and Cl. The NIST SRM612 glass was used for quantifying Au concentrations. Isotopes analyzed at BGI include 23Na, 25Mg, 27Al, 30Si, 31P, 32S, 35Cl, 39K, 43Ca, 49Ti, 51V, 53Cr, 55Mn, 57Fe, 60Ni, 65Cu, 66Zn, 85Rb, 88Sr, 89Y, 90Zr, 93Nb, 98Mo, 133Cs, 137Ba, 139La, 163Dy, 173Yb, 184W, 232Th, and 238U, whereas those analyzed at the Institute of Geological Sciences include 23Na, 25Mg, 27Al, 29Si, 31P, 34S, 35Cl, 39K, 43Ca, 49Ti, 51V, 53Cr, 55Mn, 57Fe, 65Cu, 75As, 85Rb, 88Sr, 90Zr, 93Nb, 98Mo, 109Ag, 137Ba, 181Ta, 197Au, and 208Pb.

Melt inclusion analyses were quantified by subtracting the contribution of host mineral to the mixed inclusion-host signals, using either a fixed Al2O3 content or a bulk-rock trend of Al2O3 vs. SiO2 or FeOt vs. SiO2 as internal standard50 (Supplementary Data 2). The sum of all major element oxides was normalized to 100 wt%. To optimize the host subtraction, the MgO, FeOt, CaO, P2O5, or Na2O content of some melt inclusions was fixed at a value based on the composition of bulk rocks or of well-quantified, similarly-evolved melt inclusions (please see the footnote of Supplementary Data 2 for details about how the replacement values were chosen). Sulfur and Cl concentrations in melt inclusions that were analyzed at BGI were quantified using an in-house afghanite standard that contains 4.4 wt% S and 4.4 wt% Cl, though sophisticated corrections were required51. Sulfur and Cl concentrations in melt inclusions analyzed at the Institute of Geological Sciences were quantified without any correction, using the scapolite standard Sca17 that contains 2500 μg/g S and 2.9 wt% Cl. The validity of the latter results was confirmed on glassy melt inclusions through comparison with EPMA data18. Titanium concentrations in quartz hosts were quantified by normalizing the SiO2 content to 100 wt%.

Seventeen high-salinity brine inclusions were analyzed using the Agilent 7900 ICP-MS at the Institute of Geological Sciences in Bern (Supplementary Data 7). The fluid inclusions were drilled out individually, together with part of the adjacent quartz. The contribution of quartz host was numerically subtracted from the mixed signal until no Si was left in the fluid inclusion. The GSD-1G glass was used as external standard for most elements, whereas the Sca17 standard was used for quantifying S and Cl, and the NIST SRM612 glass was used for quantifying Au. Analyzed isotopes include 23Na, 27Al, 29Si, 34S, 35Cl, 39K, 43Ca, 55Mn, 57Fe, 65Cu, 79Br, 85Rb, 88Sr, 98Mo, 109Ag, 133Cs, 182W, 197Au, and 208Pb. While the brine inclusions had salinities of ~35‒50 wt% NaClequiv, the absolute element concentrations were normalized to a constant salinity of 10 wt% NaClequiv to allow for direct comparison of all fluid inclusion data. For each analysis, that nominal salinity of 10 wt% NaClequiv was corrected for the presence of other major cations (their abundance relative to Na being known from the LA-ICP-MS analysis) to estimate the “net” Na concentration52 (all concentrations in wt%):

EPMA analysis of clinopyroxene and amphibole

A JEOL JXA-8200 EPMA hosted at BGI was used to analyze amphiboles in felsic samples (n = 17) and clinopyroxene phenocrysts in mafic to felsic samples (n = 11) for the application of thermobarometry (see below). Since most felsic porphyries experienced variable degrees of alteration following phenocryst crystallization, we focused on amphibole and clinopyroxene inclusions shielded by other phenocrysts to constrain the crystallization pressure of phenocrysts. For the analysis, fully-enclosed inclusions were exposed onto the sample surface by means of polishing. As a comparison and also to constrain the pressure of final magma emplacement, we additionally analyzed large, euhedral amphibole phenocrysts from their core to rim, and small, anhedral amphibole crystals in the matrix. The fact that even the core zones of some amphibole phenocrysts returned much lower pressures than amphibole inclusions hosted in other phenocrysts of the same samples (Supplementary Data 4) suggests that these amphibole phenocrysts sometimes re-equilibrated completely. This means that pressure constraints based on the composition of amphibole phenocrysts from mineralized porphyries should be treated with much caution53,54.

All the samples were coated with a ~ 12 nm thick carbon film. The utilized conditions were 15 kV and 10 nA, with a beam defocused to 5‒10 μm. Counting times of Na and K on peak and background before and after the peak were 10 and 5 s, respectively; for Fe, Mn, Al, Si, Ca, Ti, Cr, and Mn they were 20 and 10 s, respectively; and for Cl and F they were 60 and 30 s, respectively. The elements were standardized on albite (Na, Si), orthoclase (K), metallic Fe and Cr, enstatite (Mg), spinel (Al), wollastonite (Ca), MnTiO3 (Ti, Mn), fluorite (F), and vanadinite (Cl).

EPMA analysis of apatite

The same EPMA hosted at BGI was used for the analysis of apatite from the Jianchuan syenite porphyry and rhyolite tuff (Fig. 1c) to constrain the fluid saturation history during magma evolution. Previous studies have shown that the F-Cl-OH content of apatite can easily get modified by means of diffusion on geologically very short timescales55,56,57 (e.g., in days to years, depending on the grain size and temperature;), such that even in fresh lava rocks the F-Cl-OH content of apatite microphenocrysts can have diffusively re-equilibrated during cooling and thus have become different from that of small apatite inclusions fully enclosed in robust minerals58. Therefore, in mineralized porphyry stocks that experienced relatively slow cooling, prolonged magmatic fluid fluxing, and hydrothermal alteration, it is unavoidable that the F-Cl-OH content of apatite microphenocrysts re-equilibrated at the site of magma emplacement45,59. Rapid re-equilibration is further confirmed by our test on apatites from the very fresh Jianchuan trachyte porphyry (Supplementary Fig. 2). Since our aim is to understand the timing of fluid exsolution, we thus focused solely on apatite inclusions fully enclosed in fresh, robust phenocrysts such as zircon, clinopyroxene, plagioclase, and K-feldspar (e.g., refs. 20,45,59,60,61), rather than on apatite inclusions enclosed in non-robust phenocrysts such as biotite and amphibole, which have well-developed cleavages (e.g., refs. 62,63), or apatite microphenocrysts (e.g., refs. 54,64,65).

It has been demonstrated that apatite F and Cl X-ray count rates vary with exposure to the electron beam due to F and Cl migration66,67,68. The use of a relatively low beam energy or a relatively large beam size can reduce this effect (e.g., 10 kV accelerating voltage, 4 nA beam current, and a beam diameter defocused to 10 μm; ref. 67). To further minimize halogen migration issues, the analyzed surface of apatite crystals should be optimally parallel to their c-axis66,67. However, a beam diameter of 10 μm is often too large for the analysis of apatite inclusions, and the chance to get apatite inclusions with the c-axis exactly parallel to the sample surface is rather small. As a compromise, we thus used the analytical conditions of 15 kV, 10 nA, and 5 μm. To assess and correct the effect of halogen migration, we analyzed six gem-quality apatites from Durango, Ipira, Pakistan, Tirol, Switzerland, and Arusaha and three synthetic apatites H25, H26, and H27 as secondary standards. The F and Cl contents of the Durango apatite and the synthetic apatites have previously been determined by wet chemistry67,68. The Durango and Ipira crystals were analyzed in five different orientations (Supplementary Fig. 3). In the case of F the measured concentrations vary substantially as a function of the angle between the sample surface and the crystallographic c-axis, whereas in the case of Cl the measured concentrations remained almost constant (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). The fitted equation in the plot in Supplementary Fig. 3c was thus employed to correct for F concentrations in the measured apatite unknowns, with the orientation of apatite inclusions estimated using polarized transmitted light microscopy. Using this approach, the uncertainties of the measured F and Cl concentrations are estimated at 5–10% and 10–15%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3; Supplementary Data 8).

All the apatite unknowns and secondary standards were coated with a ~ 12 nm thick carbon film. Fluorine and Cl were analyzed first to minimize the effect of diffusive loss during the analysis. Counting times of F, Cl, S, and Mg on peak and background before and after the peak were 60 and 30 s, respectively; P, Ca, Na, K, Si, Al, Fe, and Ti were 20 and 10 s. The elements were standardized on fluorite (F), tugtupite (Cl), apatite (Ca, P), albite (Na, Si), orthoclase (K), spinel (Al), enstatite (Mg), barite (S), MnTiO3 (Mn, Ti), and hematite (Fe).

Thermobarometry

Thermobarometry based on the composition of clinopyroxene crystals with or without coexisting silicate liquid has been widely used in magmatic systems, but different calibrations return vastly different results69. To identify the most accurate and precise expressions for application to the Sanjiang potassic magmas, we tested the various calibrations on 39 hydrous experiments conducted at 0.1–1.5 GPa and 850–1300 °C on starting materials that are compositionally similar to the Sanjiang potassic magmas17,18,70. These experimental data are best captured by the following two equations (Supplementary Fig. 4):

and

where X denotes mole fraction. Equation (3) is modified after equation (32b) of ref. 71, whereas Eq. (4) is modified after model (B) of ref. 72. Wieser et al.73 suggested that the clinopyroxene (± liquid)-based thermobarometers generally exhibit relatively large uncertainties (±0.3 GPa and ±40 °C). To find the best-matching liquid compositions for the natural clinopyroxenes from Sanjiang, we numerically related the liquid SiO2 to all the other major elements based on fitting equations in bulk-rock Harker diagrams and then varied the content of liquid SiO2 until an equilibrium Fe–Mg exchange coefficient between clinopyroxene and the liquid was found (i.e., KD(Fe–Mg) = 0.27 ± 0.03, refs. 71,72; Supplementary Data 3). The trachybasaltic andesitic melts and trachydacitic to rhyolitic melts were assumed to have contained 4 wt% H2O and 8 wt% H2O, respectively. Varying the melt H2O content by 1 wt% results in a small change of the calculated pressures (i.e., ≤0.05 GPa). Mole fractions of clinopyroxene and liquid components in Eqs. (3) and (4) were calculated using the template provided in ref. 74.

The amphibole crystals in the felsic rocks at Sanjiang are part of the low-variance mineral assemblage amphibole + plagioclase + alkali feldspar + biotite + quartz + titanite + magnetite + apatite (Supplementary Data 1) and thus can be used to calculate pressures using the formulation of ref. 23 (Supplementary Data 4). Their Altot value (in atoms per formula unit) was calculated using the template provided in ref. 75, and the corresponding pressure was calculated according to the following equation23:

Mutch et al.23 state that the relative pressure uncertainty is about ±16% and that the minimum absolute uncertainty is not better than 0.06 GPa. Since this barometer was calibrated also on a large dataset from natural granitic samples with independent pressure constraints, the uncertainties of our pressure estimates are unlikely to be significantly higher than the recommended values.

The crystallization pressure of quartz phenocrysts in the Sanjiang felsic rocks was calculated using the composition of quartz-hosted melt inclusions and Ti concentrations in the quartz host determined by LA-ICP-MS (Supplementary Data 5), based on the Ti-in-quartz thermobarometer of ref. 24 and the approach described in ref. 25. The solubility of Ti in quartz is described by the equation24:

To determine the pressure, the temperature and the activity of TiO2 need to be independently constrained. Since the crystallization of the quartz phenocrysts occurred at zircon-saturated conditions, the temperature can be estimated based on zircon saturation thermometry76 applied to melt inclusions:

For the calculation of \({{\mathrm{D}}}_{{\mathrm{Zr}}}^{{\mathrm{zir}}/{\mathrm{liq}}}\), the zircon is assumed to have contained a typical ZrO2 content of 62.5 wt%. The TiO2 activity in magmas is calculated based on the following solubility model77 applied to the melt inclusion compositions:

The uncertainty of calculated pressures using this approach is likely better than 0.1 GPa, based on comparison with independent pressure constraints in natural magma systems25,78,79.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data that were generated in this study are provided in the files Supplementary Data 1–8. The raw data underlying the figures are available in the Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Sillitoe, R. H. Porphyry copper systems. Econ. Geol. 105, 3–41 (2010).

Richards, J. P. Magmatic to hydrothermal metal fluxes in convergent and collided margins. Ore Geol. Rev. 40, 1–26 (2011).

Audétat, A. & Simon, A. C. Magmatic controls on porphyry copper genesis. in Hedenquist, J. W., Harris, M. & Camus F. (eds) Geology and Genesis of Major Copper Deposits and Districts of the World: A Tribute to Richard H. Sillitoe. Special Publications 16 553–572 (Society of Economic Geologists). https://doi.org/10.5382/SP.16.21 (2012).

Heinrich, C. A. The chain of processes forming porphyry copper deposits—An invited paper. Econ. Geol. 119, 741–769 (2024).

Rohrlach, B. D. & Loucks, R. R. Multi-million-year cyclic ramp-up of volatiles in a lower crustal magma reservoir trapped below the Tampakan copper-gold deposit by Mio-Pliocene crustal compression in the southern Philippines. in Super Porphyry Copper & Gold Deposits—A Global Perspective (ed. Porter, T. M.) vol. 2, 369–407 (PCG Publishing, Adelaide, 2005).

Loucks, R. R. Deep entrapment of buoyant magmas by orogenic tectonic stress: its role in producing continental crust, adakites, and porphyry copper deposits. Earth Sci. Rev. 220, 103744 (2021).

Sillitoe, R. H. & Perelló, J. Porphyry copper recurrence in the Andes of Chile and Argentina. Econ. Geol. 119, 995–1003 (2024).

Dilles, J. H. Petrology of the Yerington Batholith, Nevada; evidence for evolution of porphyry copper ore fluids. Econ. Geol. 82, 1750–1789 (1987).

Chelle-Michou, C., Rottier, B., Caricchi, L. & Simpson, G. Tempo of magma degassing and the genesis of porphyry copper deposits. Sci. Rep. 7, 40566 (2017).

Chiaradia, M. & Caricchi, L. Stochastic modelling of deep magmatic controls on porphyry copper deposit endowment. Sci. Rep. 7, 44523 (2017).

Sillitoe, R. H. The tops and bottoms of porphyry copper deposits. Econ. Geol. 68, 799–815 (1973).

Seedorff, E., Barton, M. D., Stavast, W. J. A. & Maher, D. J. Root zones of porphyry systems: extending the porphyry model to depth. Econ. Geol. 103, 939–956 (2008).

Seedorff, E. et al. Temporal evolution of the Laramide arc: U-Pb geochronology of plutons associated with porphyry copper mineralization in east-central Arizona. in Geologic Excursions in Southwestern North America (ed. Pearthree, P. A.) vol. 55, 369–400 (Geological Society of America, 2019).

Olson, N. H. The geology, geochronology, and geochemistry of the Kaskanak Batholith, and other Late Cretaceous to Eocene magmatism at the Pebble porphyry Cu-Au-Mo deposit, SW Alaska. (Oregon State University, 2015).

Abdullin, R. et al. Ascent of volatile-rich felsic magma in dikes: a numerical model applied to deep-sourced porphyry intrusions. Geophys J. Int 236, 1963–1876 (2024).

Chang, J. & Audétat, A. Post-subduction porphyry Cu magmas in the Sanjiang region of southwestern China formed by fractionation of lithospheric mantle–derived mafic magmas. Geology 51, 64–68 (2023).

Chang, J. & Audétat, A. Experimental equilibrium and fractional crystallization of a H2O, CO2, Cl and S-bearing potassic mafic magma at 1.0 GPa, with implications for the origin of porphyry Cu (Au, Mo)-forming potassic magmas. J. Pet. 64, egad034 (2023).

Chang, J., Audétat, A. & Pettke, T. The gold content of mafic to felsic potassic magmas. Nat. Commun. 15, 6988 (2024).

Hsu, Y.-J., Zajacz, Z., Ulmer, P. & Heinrich, C. A. Chlorine partitioning between granitic melt and H2O-CO2-NaCl fluids in the Earth’s upper crust and implications for magmatic-hydrothermal ore genesis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 261, 171–190 (2019).

Huang, W. et al. Determining the impact of magma water contents on porphyry Cu fertility: Constraints from hydrous and nominally anhydrous mineral analyses. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 136, 673–688 (2023).

Johannes, W. & Holtz, F. Petrogenesis and Experimental Petrology of Granitic Rocks. (Berlin, Springer, Berlin, 1996).

Ni, H. & Keppler, H. Carbon in silicate melts. Rev. Miner. Geochem. 75, 251–287 (2013).

Mutch, E. J. F., Blundy, J. D., Tattitch, B. C., Cooper, F. J. & Brooker, R. A. An experimental study of amphibole stability in low-pressure granitic magmas and a revised Al-in-hornblende geobarometer. Contrib. Miner. Pet. 171, 85 (2016).

Huang, R. & Audétat, A. The titanium-in-quartz (TitaniQ) thermobarometer: a critical examination and re-calibration. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 84, 75–89 (2012).

Audétat, A. Origin of Ti-rich rims in quartz phenocrysts from the Upper Bandelier Tuff and the Tunnel Spring Tuff, southwestern USA. Chem. Geol. 360–361, 99–104 (2013).

Deng, J., Wang, Q.-F., Li, G.-J. & Santosh, M. Cenozoic tectono-magmatic and metallogenic processes in the Sanjiang region, southwestern China. Earth Sci. Rev. 138, 268–299 (2014).

Halter, W. E., Pettke, T. & Heinrich, C. A. The origin of Cu/Au ratios in porphyry-type ore deposits. Science 296, 1844–1846 (2002).

Nicholson, E. J. et al. Sulfide saturation and resorption modulates sulfur and metal availability during the 2014–15 Holuhraun eruption, Iceland. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 164 (2024).

Chang, J., Li, J.-W., Selby, D., Liu, J.-C. & Deng, X.-D. Geological and chronological constraints on the long-lived Eocene Yulong porphyry Cu-Mo deposit, eastern Tibet: Implications for the lifespan of giant porphyry Cu deposits. Econ. Geol. 112, 1719–1746 (2017).

He, W.-Y. et al. The geology and mineralogy of the Beiya skarn gold deposit in Yunnan, southwest China. Econ. Geol. 110, 1625–1641 (2015).

Chang, J., Li, J.-W. & Audétat, A. Formation and evolution of multistage magmatic-hydrothermal fluids at the Yulong porphyry Cu-Mo deposit, eastern Tibet: Insights from LA-ICP-MS analysis of fluid inclusions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 232, 181–205 (2018).

Liu, H. et al. Nature and evolution of fluid inclusions in the Cenozoic Beiya gold deposit, SW China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 161, 35–56 (2018).

Liu, Q. et al. Geochronology and fluid evolution of the Machangqing Cu-Mo polymetallic deposit, western Yunnan, SW China. Ore Geol. Rev. 127, 103828 (2020).

Monecke, T. et al. Quartz solubility in the H2O-NaCl system: a framework for understanding vein formation in porphyry copper deposits. Econ. Geol. 113, 1007–1046 (2018).

Sun, M., Monecke, T., Reynolds, T. J. & Yang, Z. Understanding the evolution of magmatic-hydrothermal systems based on microtextural relationships, fluid inclusion petrography, and quartz solubility constraints: insights into the formation of the Yulong Cu-Mo porphyry deposit, eastern Tibetan Plateau, China. Min. Depos. 56, 823–842 (2021).

Tosdal, R. M. & Dilles, J. H. Creation of permeability in the porphyry Cu environment. Rev. Econ. Geol. 21, 173–204 (2020).

Huber, C., Bachmann, O. & Dufek, J. Thermo-mechanical reactivation of locked crystal mushes: Melting-induced internal fracturing and assimilation processes in magmas. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 304, 443–454 (2011).

He, W.-Y. et al. Origin of the Eocene porphyries and mafic microgranular enclaves from the Beiya porphyry Au polymetallic deposit, western Yunnan, China: Implications for magma mixing/mingling and mineralization. Gondwana Res. 40, 230–248 (2016).

Gao, X.-Q., He, W.-Y., Gao, X., Bao, X.-S. & Yang, Z. Constraints of magmatic oxidation state on mineralization in the Beiya alkali-rich porphyry gold deposit, western Yunnan, China. Solid Earth Sci. 2, 65–78 (2017).

Pacey, A. et al. The anatomy of an alkalic porphyry Cu-Au system: Geology and alteration at Northparkes mines, New South Wales, Australia. Econ. Geol. 114, 441–472 (2019).

Parmigiani, A., Degruyter, W., Leclaire, S., Huber, C. & Bachmann, O. The mechanics of shallow magma reservoir outgassing. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 18, 2887–2905 (2017).

Huber, C., Bachmann, O., Vigneresse, J., Dufek, J. & Parmigiani, A. A physical model for metal extraction and transport in shallow magmatic systems. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 13 (2012).

Pollard, P. & Taylor, R. Paragenesis of the Grasberg Cu-Au deposit, Irian Jaya, Indonesia: results from logging section 13. Min. Depos. 37, 117–136 (2002).

Anderson, E. D., Atkinson, W. W., Marsh, T. & Iriondo, A. Geology and geochemistry of the Mammoth breccia pipe, Copper Creek mining district, southeastern Arizona: evidence for a magmatic–hydrothermal origin. Min. Depos. 44, 151 (2009).

Nathwani, C. L., Large, S. J. E., Brugge, E. R., Wilkinson, J. J. & Buret, Y. Apatite evidence for a fluid-saturated, crystal-rich magma reservoir forming the Quellaveco porphyry copper deposit (Southern Peru). Contrib. Miner. Pet. 178, 49 (2023).

Hunt, J. P. Porphyry copper deposits. Econ. Geol. Monogr. 8, 192–206 (1991).

Seedorff, E. et al. Porphyry deposits: characteristics and origin of hypogene features. in One Hundredth Anniversary Volume 251–298 (Society of Economic Geologists). https://doi.org/10.5382/AV100.10 (2005).

Murakami, H., Seo, J. H. & Heinrich, C. A. The relation between Cu/Au ratio and formation depth of porphyry-style Cu–Au ± Mo deposits. Min. Depos. 45, 11–21 (2010).

Halter, W. E., Pettke, T., Heinrich, C. A. & Rothen-Rutishauser, B. Major to trace element analysis of melt inclusions by laser-ablation ICP-MS: methods of quantification. Chem. Geol. 183, 63–86 (2002).

Chang, J. & Audétat, A. LA-ICP-MS analysis of crystallized melt inclusions in olivine, plagioclase, apatite and pyroxene: quantification strategies and effects of post-entrapment modifications. J. Pet. 62, egaa085 (2021).

Rottier, B. & Audétat, A. In-situ quantification of chlorine and sulfur in glasses, minerals and melt inclusions by LA-ICP-MS. Chem. Geol. 504, 1–13 (2019).

Heinrich, C. A. et al. Quantitative multi-element analysis of minerals, fluid and melt inclusions by laser-ablation inductively-coupled-plasma mass-spectrometry. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 67, 3473–3497 (2003).

Huang, M.-L. et al. Apatite volatile contents of porphyry Cu deposits controlled by depth-related fluid exsolution processes. Econ. Geol. 118, 1201–1217 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. Mechanisms of fluid degassing in shallow magma chambers control the formation of porphyry deposits. Am. Miner. 109, 2073–2085 (2024).

Stock, M. J., Humphreys, M. C. S., Smith, V. C., Isaia, R. & Pyle, D. M. Late-stage volatile saturation as a potential trigger for explosive volcanic eruptions. Nat. Geosci. 9, 249–254 (2016).

Li, W., Chakraborty, S., Nagashima, K. & Costa, F. Multicomponent diffusion of F, Cl and OH in apatite with application to magma ascent rates. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 550, 116545 (2020).

Humphreys, M. C. S. et al. Rapid pre-eruptive mush reorganisation and atmospheric volatile emissions from the 12.9 ka Laacher See eruption, determined using apatite. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 576, 117198 (2021).

Stock, M. J. et al. Tracking volatile behaviour in sub-volcanic plumbing systems using apatite and glass: Insights into pre-eruptive processes at Campi Flegrei, Italy. J. Pet. 59, 2463–2492 (2018).

Huang, W. et al. Reconstructing volatile exsolution in a porphyry ore-forming magma chamber: Perspectives from apatite inclusions. Am. Miner. 109, 1406–1418 (2024).

Stonadge, G., Miles, A., Smith, D., Large, S. & Knott, T. The volatile record of volcanic apatite and its implications for the formation of porphyry copper deposits. Geology 51, 1158–1162 (2023).

Sun, X. et al. Two stages of porphyry Cu mineralization at Jiru in the Tibetan collisional orogen: Insights from zircon, apatite, and magmatic sulfides. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 135, 2971–2986 (2023).

Zhu, J.-J. et al. Elevated magmatic sulfur and chlorine contents in ore-forming magmas at the Red Chris porphyry Cu-Au deposit, northern British Columbia, Canada. Econ. Geol. 113, 1047–1075 (2018).

Huang, M.-L., Zhu, J.-J., Bi, X.-W., Xu, L.-L. & Xu, Y. Low magmatic Cl contents in giant porphyry Cu deposits caused by early fluid exsolution: A case study of the Yulong belt and implication for exploration. Ore Geol. Rev. 141, 104664 (2022).

Chelle-Michou, C. & Chiaradia, M. Amphibole and apatite insights into the evolution and mass balance of Cl and S in magmas associated with porphyry copper deposits. Contrib. Miner. Pet. 172, 105 (2017).

Parra-Avila, L. A. et al. The long-lived fertility signature of Cu–Au porphyry systems: insights from apatite and zircon at Tampakan, Philippines. Contrib. Miner. Pet. 177, 18 (2022).

Stormer, J. R., J. C., Pierson, M. L. & Tacker, R. C. Variation of F and Cl X-ray intensity due to anisotropic diffusion in apatite during electron microprobe analysis. Am. Miner. 78, 641–648 (1993).

Goldoff, B., Webster, J. D. & Harlov, D. E. Characterization of fluor-chlorapatites by electron probe microanalysis with a focus on time-dependent intensity variation of halogens. Am. Miner. 97, 1103–1115 (2012).

Stock, M. J., Humphreys, M. C. S., Smith, V. C., Johnson, R. D. & Pyle, D. M. New constraints on electron-beam induced halogen migration in apatite. Am. Miner. 100, 281–293 (2015).

Wieser, P. E., Kent, A. J. R. & Till, C. B. Barometers behaving badly II: a critical evaluation of cpx-only and cpx-liq thermobarometry in variably-hydrous arc magmas. J. Pet. 64, egad050 (2023).

Parat, F., Holtz, F., René, M. & Almeev, R. Experimental constraints on ultrapotassic magmatism from the Bohemian Massif (durbachite series, Czech Republic). Contrib. Miner. Pet. 159, 331–347 (2010).

Putirka, K. D. Thermometers and barometers for volcanic systems. Rev. Miner. Geochem. 69, 61–120 (2008).

Putirka, K. D., Mikaelian, H., Ryerson, F. & Shaw, H. New clinopyroxene-liquid thermobarometers for mafic, evolved, and volatile-bearing lava compositions, with applications to lavas from Tibet and the Snake River Plain, Idaho. Am. Miner. 88, 1542–1554 (2003).

Wieser, P. E. et al. Barometers behaving badly I: Assessing the influence of analytical and experimental uncertainty on clinopyroxene thermobarometry calculations at crustal conditions. J. Pet. 64, egac126 (2023).

Neave, D. A. & Putirka, K. D. A new clinopyroxene-liquid barometer, and implications for magma storage pressures under Icelandic rift zones. Am. Miner. 102, 777–794 (2017).

Putirka, K. Amphibole thermometers and barometers for igneous systems and some implications for eruption mechanisms of felsic magmas at arc volcanoes. Am. Miner. 101, 841–858 (2016).

Watson, E. B. & Harrison, T. M. Zircon saturation revisited: temperature and composition effects in a variety of crustal magma types. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 64, 295–304 (1983).

Hayden, L. A. & Watson, E. B. Rutile saturation in hydrous siliceous melts and its bearing on Ti-thermometry of quartz and zircon. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 258, 561–568 (2007).

Kularatne, K. & Audétat, A. Rutile solubility in hydrous rhyolite melts at 750–900 °C and 2 kbar, with application to titanium-in-quartz (TitaniQ) thermobarometry. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 125, 196–209 (2014).

Audétat, A. et al. New constraints on Ti diffusion in quartz and the priming of silicic volcanic eruptions. Nat. Commun. 14, 4277 (2023).

Zeng, P., Mo, X. & Yu, X. Nd, Sr and Pb isotopic characteristics of the alkaline-rich porphyries in western Yunnan and its compression strike-slip setting. Acta Petrol. et Mineral. 21, 231–241 (2002).

Zhao, Y., Liu, L. & Wang, Y. Regional Geological Survey Report Lanping (G-47-X VI) 1:200000 (In Chinese). (1974).

Wang, Z., Zhang, Y. & Peng, X. Regional Geological Survey Report Weixi (G-47-X) 1:200000 (In Chinese). (1984).

Webster, J. D., Goldoff, B., Sintoni, M. F., Shimizu, N. & De Vivo, B. C-O-H-Cl-S-F volatile solubilities, partitioning, and mixing in phonolitic-Trachytic melts and aqueous-carbonic vapor saline liquid at 200 MPa. J. Pet. 55, 2217–2248 (2014).

Zhang, C., Li, X., Behrens, H. & Holtz, F. Partitioning of OH-F-Cl between biotite and silicate melt: experiments and an empirical model. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 317, 155–179 (2022).

Seo, J. H. & Heinrich, C. A. Selective copper diffusion into quartz-hosted vapor inclusions: evidence from other host minerals, driving forces, and consequences for Cu–Au ore formation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 113, 60–69 (2013).

Lerchbaumer, L. & Audétat, A. High Cu concentrations in vapor-type fluid inclusions: An artifact? Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 88, 255–274 (2012).

Burnham, C. W. Magmas and hydrothermal fluids. in Geochemistry of Hydrothermal Ore Deposits (ed. Barnes, H. L.) 71–136 (John Wiley and Sons, New York, 1979).

Whitney, J. A. The origin of granite: The role and source of water in the evolution of granitic magmas. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 100, 1886–1897 (1988).

Landtwing, M. et al. Copper deposition during quartz dissolution by cooling magmatic–hydrothermal fluids: The Bingham porphyry. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 235, 229–243 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We thank Shiguang Du for his help with the fieldwork, Siqi Liu for providing two samples from Beiya, and Daniel Harlov for providing synthetic apatites. We also like to thank Raphael Njul and Detlef Krauße for preparing epoxy sample mounts and calibrating standards for the EPMA analyses, respectively. A.A. and J.C. acknowledge funding by the German Science Foundation (DFG; grant Nr. 440924553). T.P. acknowledges funding by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant Nr. 206021_170722 to Daniela Rubatto and T.P.). J.C. was partly supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (grant Nr. 2023YFF0804200) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant Nr. 42321001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C. and A.A. conceived the project. T.P. performed the LA-ICP-MS analyses of fluid inclusions and some melt inclusions. J.C. collected the samples, conducted the petrography, all the other LA-ICP-MS analyses, the EPMA analyses, the data reduction, and the thermobarometry, and wrote the manuscript with substantial input from A.A. and T.P.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Zoltan Zajacz, Olivia Hogg, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, J., Audétat, A. & Pettke, T. Ten kilometers ascent of porphyry Cu (Au, Mo)-forming fluids in the Sanjiang region, China. Nat Commun 16, 2330 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57710-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57710-z