Abstract

Quantum simulators are ideal platforms to investigate quantum phenomena that are inaccessible through conventional means, such as the limited resources of classical computers to address large quantum systems or due to constraints imposed by fundamental laws of nature. Here, through a digitized adiabatic evolution, we report an experimental simulation of antiferromagnetic (AFM) and ferromagnetic (FM) phase formation induced by spontaneous symmetry breaking (SSB) in a three-generation Cayley tree-like superconducting lattice. We develop a digital quantum annealing algorithm to mimic the system dynamics, and observe the emergence of signatures of SSB-induced phase transition through a connected correlation function. We demonstrate that the signature of a transition from classical AFM to quantum FM-like phase state happens in systems undergoing zero-temperature adiabatic evolution with only nearest-neighbor interacting systems, the shortest range of interaction possible. By harnessing properties of the bipartite Rényi entropy as an entanglement witness, we observe the formation of entangled quantum FM and AFM phases. Our results open perspectives for new advances in condensed matter physics and digitized quantum annealing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Symmetry in physical systems has led to a number of scientific and technological advances related to conservation laws of nature encapsulated by Noether’s theorem1. On the other hand, symmetry breaking is a key mechanism in condensed matter physics and the standard model2,3,4,5, and second-generation quantum devices in spintronics6,7,8. In particular, at finite-temperature systems, spontaneous symmetry breaking (SSB) is of great interest for quantum phase transitions phenomena in low-dimensional systems (one and two dimensions)9,10,11,12, as it may lead to the formation of genuine long-range order when the physical system contains sufficiently long-ranged interactions13,14. Recently, two independent experimental realizations in one-dimensional trapped ion chains15 and two-dimensional (2D) Rydberg atoms arrays16 have successfully observed continuous symmetry breaking and the formation of long-range order. Experimental realizations in trapped ions have been possible because such a phenomenon in low-dimensional quantum systems can be achieved for power-law interactions as V(r) ~ r−α, with α < 317. Such a theorem applies to a large class of systems, at temperature T > 0 and dimension D ≤ 2, like interacting electrons in a metal18, spin systems described by Heisenberg chains13,14, Hubbard and Kondo lattices19, among others20,21. Although the Mermin-Wagner13,14, which forbids the formation of correlated antiferromagnetic (AFM) and ferromagnetic (FM) states, does not apply to zero-temperature systems, it is believed that SSB is also forbidden for one-dimensional systems17. Therefore, this subject is less explored than its finite-temperature counterpart13,14,15,16,17,22.

In this scenario, gate-based digital quantum simulators can efficiently observe zero-temperature quantum phenomena or processes, since such a cooling regime for quantum analog computers is not allowed as a consequence of the third law of thermodynamics: the unattainability principle23,24. As a promising platform for both digitized and analog tasks, superconducting integrated circuits are universal platforms to mimic adiabatically driven quantum processes at zero temperature through quantum annealing25,26, or digitized adiabatic evolutions (DAE)27. The DAE method aims to create a model of computation that takes advantage of two different models: adiabatic quantum computation28 and quantum circuit model of computation29,30,31. Inspired by the application potential of DAE, the goals of this work are twofold: (i) establish a general and sufficient condition for high-fidelity digitized adiabatic quantum computation, and (ii) report the experimental simulation of zero-temperature SSB in a 2D Cayley tree spin chain without long-range interactions. The signature of SSB is observed through two-point correlation functions and the second-order Rényi entropy, revealing the correlation profile over the system and the emergence of genuine entanglement in the system, respectively.

Results

The digital quantum annealing

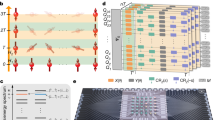

Since the zero-temperature SSB transition is simulated by keeping the maximum purity of the system, this can be done through closed system adiabatic evolution32. For this reason, as sketched in Fig. 1a, we aim to investigate the digital adiabatic evolution driven by the time-dependent Hamiltonian of the generic form \(\hat{H}(t)=f(t){\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{ini}}}}}+g(t){\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{fin}}}}}\). The functions f, g satisfy f(0) = g(τ) ≠ 0 and f(τ) = g(0) = 0, with τ the total evolution time. In this way, we are able to describe how the experimental simulation of SSB for the lattice is engineered through the digitization of adiabatic evolution. To this end, we first introduce the Suzuki–Trotter adiabatic digitization that governs the performance of adiabatic quantum optimization tasks in digital quantum processors. Given the Schrödinger equation, \(i\hslash \left\vert \dot{\psi }(t)\right\rangle=\hat{H}(t)\left\vert \psi (t)\right\rangle\), to digitize the dynamics we consider the Riemann-like discretization of the evolution, as sketched in Fig. 1a. Let us define now the normalized time s ∈ [0, 1] as s = t/τ. In this approach, the evolution for the nth step of the digitizing procedure is governed by the evolution operator \({\hat{U}}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}({s}_{n+1};{s}_{n})\), during a time interval δsn = sn + 1−sn. \({\hat{U}}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}({s}_{n+1};{s}_{n})\) is obtained from the Hamiltonian parameters at the instant of time \({\bar{s}}_{n}=({s}_{n+1}+{s}_{n})/2\) and assuming a time-independent evolution for a time duration of δsn (first approximation of the method). Following this strategy, we aim to find a quantum circuit able to properly mimic the evolution, where each operator \({\hat{U}}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}({s}_{n+1};{s}_{n})\) is given by the first-order Trotter decomposition (second approximation). In this way, as shown in the “Methods” section, we can properly digitize the evolution and make a direct relation between the adiabatic energy gap and the total number of blocks M required for the digitized annealing procedure through the digitized decomposition of the evolution operator as

a The procedure to digitize an adiabatic evolution is done through a Riemann-like discretization of the time interval s ∈ [0, 1], where each step in time corresponds to the digital block. The time-continuous adiabatic algorithm implemented through time-dependent fields can be efficiently decomposed in a sequence of pulses through a circuit version of the evolution. After M blocks the output state is expected to be prepared with good fidelity without any computation complexity due to the search for the optimal parameters of the circuit. b The only optimization required to reduce the circuit length is done through the suitable choice of the parameters of the Hamiltonian. The a priori knowledge of the parameters of the Hamiltonian, which leads to a large energy gap, will enhance the digitized algorithm.

In this way, as depicted in Fig. 1b, the performance of the DAE may be optimized by finding the best functions f(s) and g(s) to maximize the minimum adiabatic gap. This can be done by a suitable choice of the Hamiltonian interpolation functions as determined by quantum adiabatic brachistochrone trajectories33,34, which will be considered in this work.

It is worth mentioning that, even though this method is not a variational algorithm and classical optimization is not required, the complexity of the problem may be as costly as simulating \({\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{fin}}}}}\). In general, such a complexity will increase with the number of qubits and the presence of many-body terms in \({\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{fin}}}}}\), and in this sense, the digital annealing is as complex as any other simulation or variational algorithm. However, when \({\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{fin}}}}}\) is efficiently implemented in a real quantum processor, the complexity of the digital algorithm, i.e., the number of blocks M, does not necessarily increase. In this case, we can take advantage of digital annealers even for larger systems. To exemplify this, in Supplementary Note 135, we show the numerical simulation of a digitized SSB in a 15-qubit using a number of blocks smaller than that one required for SSB in a 7-qubit system, where we used the solution of the analog dynamics through exact numerical diagonalization.

The three-generation Cayley tree-like device

The physical system of interest in the experimental setup consists of seven qubits in a three-generation Cayley tree-like superconducting 2D lattice shown in Fig. 2a. Our tree-like processor employs a flip-chip packaging process in which the device consists of a 3D chip with two layers of superconducting elements, separated by 9 μm. In this setup, the qubits and couplers are placed on the top layer of the chip, while the complex of Purcell filter, control lines, and readout resonators are placed on the bottom layer. This pristine environment enhances the quality of both qubits and couplers with respect to undesired systematic errors. These seven qubits exhibited an average single-qubit gate fidelity of 99.92%, and for the two-qubit gate, we reached 98.68%. See Supplementary Note 2 for more information on the device parameters and calibration35.

a The 7-qubit Tree sub-lattice used in our experiment. Our chip is a 3D chip, in which the Purcell filter, readout resonators, and flux and control lines are placed on a layer different from the couplers and transmon qubits. b The circuit considered in our experiment is composed of a first layer of single-qubit gates, emulating local fields, followed by interaction blocks to mimic the spin-spin interaction during the evolution. As stated by Theorem 1, given the minimum energy gap \({\Delta }_{\min }\), high-fidelity digitization is achieved when \(M\propto 1/{\Delta }_{\min }^{2}\). For the dynamics under consideration, we used M = 5 for all the simulations. In (c), we sketch the influence of symmetry on the dynamics, where the transition into FM and AFM quantum phases occurs in different magnetization planes. d The experimental data for the energy splitting along the digitized evolution of the system from the initial to the final state. Time is encoded in the number of blocks of the digitized circuit (n = 0 and n = 5 refers to t = 0 and t = τ, respectively), for Jτ = 5.

In our experiment, the quantum processor is not a zero-temperature system, as it is impossible by fundamental laws of nature, and the temperature of the quantum processing unity is around 10 mK. However, the target evolution we will implement using an experimental digital quantum circuit corresponds to a zero-temperature unitary evolution of the system driven by an ideal adiabatic Hamiltonian. In other words, we perform a digital circuit able to simulate the expected dynamics of a system undergoing unitary evolution in contact with a zero-temperature environment. As we shall see, even under the presence of noise, gate errors, and thermal fluctuations, we can properly observe the emergence of SSB from our experimental digital simulation because it in fact captures the zero-temperature aspect of the target evolution.

The system is driven through an SSB-induced transition from an initial state given by the classical Néel state. In our system, the Néel state is defined in such a way that the spin state of any pair of adjacent spins are opposite to each other, that is, they are initially at state \(\left\vert \uparrow \downarrow \right\rangle\) or \(\left\vert \downarrow \uparrow \right\rangle\) (as shown in Fig. 2b). For our topology, such Néel states can be obtained from the generation-staggered field Hamiltonian for the tree lattice given by

where L denotes the total number of generations of the tree (for 7 spins, one has L = 3) and Nl the total number of spins in the lth generation, given in terms of l as Nl = 2l. It is worth mentioning that our initial Hamiltonian is not unique, as any other Hamiltonian that commutes with HNeel share the same set of eigenstates HNeel. However, if we assume only the set of all non-interacting Hamiltonians, then the Hamiltonian \({\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{N}}}} {\acute{\rm {e}}} {{{\rm{el}}}}}\) considered is unique. The above Néel Hamiltonian has two important energy states, namely, the ground and excited classical Néel states given, respectively, by

where \({\left\vert \uparrow \right\rangle }_{{n}^{{{{\rm{th}}}}}}\) denotes that all spins in the nth layer are in the spin-up state, and similarly for \({\left\vert \downarrow \right\rangle }_{{n}^{{{{\rm{th}}}}}}\). The highest energy eigenstate of the Hamiltonian \({\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{N}}}} {\acute {{{\rm{e}}}}} {{{\rm{el}}}}}\) is denoted the excited classical Neel state. In this way, a given spin site with a positively-oriented local magnetic field only interacts with a negatively-oriented one, when the interaction Hamiltonian for our system device reads

where ∑〈n, k〉 is a sum over all connections of the tree-like lattice. Therefore, the adiabatic Hamiltonian for the SSB in our device is \(\hat{H}(s)=f(s){\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{N}}}} {\acute {{{\rm{e}}}}} {{{\rm{el}}}}}+g(s){\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{Tree}}}}}\). As we shall see soon, the preparation of the system in the classical Néel states in Eq. (3) is relevant to the final target state of the evolution because they allow us to have different quantum phases encoded in the correlated eigenstates of the final Hamiltonian \({\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{Tree}}}}}\).

All information about the circuit that digitizes \(\hat{H}(s)\), such as connectivity and gate parameters, is obtained from the adiabatic digitization at first-order Suzuki–Trotter, Eq. (1). In our particular case, the native circuit topology (Fig. 2a) allows us to find an optimized gate sequence of the circuit to simulate each block. Our gate parameters are chosen to approximate the Quantum Adiabatic Brachistochrone interpolation functions33

A preliminary simulation of the analog adiabatic dynamics indicates that a total evolution time given by τJ0 = 5 is enough to approximately achieve the adiabatic regime of this dynamics. After each block of the circuit, shown in Fig. 2b, we measure physical quantities related to the outcome state of the system, focusing on the signature of SSB transitions through two complementary quantities: energy and pair-wise connected correlations.

The system has a symmetry in \({\hat{M}}_{z}\), since \([{\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{N}}}} {\acute {{{\rm{e}}}}} {{{\rm{el}}}}},{\hat{M}}_{z}]=0\), therefore each adiabatic evolution from the ground/excited Néel states will take place over a different magnetization (\(\langle {\hat{M}}_{z}\rangle\)) plane (Fig. 2c). The expectation value of the total magnetization, \({\hat{M}}_{z}=(\hslash /2){\sum }_{n}{\hat{\sigma }}_{z}^{n}\), for the ground (exited) state is negative (positive). Therefore, as a first quantity able to highlight the transition from the classical AFM Néel state to quantum AFM-like and FM-like phases, we evaluate the energy of the system with respect to the Tree Hamiltonian \(\langle {\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{Tree}}}}}\rangle\). For this purpose, we use \(\langle {\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{Tree}}}}}\rangle /\hslash {J}_{0}={\sum }_{\langle n,k\rangle }\left(\langle {\hat{\sigma }}_{n}^{x}{\hat{\sigma }}_{k}^{x}\rangle+\langle {\hat{\sigma }}_{n}^{y}{\hat{\sigma }}_{k}^{y}\rangle \right)\), where the two-body \(\langle {\hat{\sigma }}_{n}^{x/y}{\hat{\sigma }}_{k}^{x/y}\rangle\) terms are experimentally obtained by standard measurement protocols36. As it can be seen from the experimental data in Fig. 2d, both the ground and excited Néel states have the same energy with respect to this reference Hamiltonian, namely \(\langle {\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{Tree}}}}}\rangle=0\). However, by driving the system continuously from the initial Néel field Hamiltonian \({\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{N}}}} {\acute{{{\rm{e}}}}} {{{\rm{el}}}}}\) to the tree-like one \({\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{Tree}}}}}\), the instantaneous system energy, with respect to the \({\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{Tree}}}}}\), presents an energy splitting due to the formation of either the FM-like or the AFM-like phase, depending on the initial Néel state considered (sketched in Fig. 2d). When the system starts in the classical AFM Néel state with negative magnetization (ground state), it follows a trajectory on the negative magnetization plane while decreasing the system energy. Conversely, by preparing the system in the AFM Néel state with positive magnetization (excited state), we observe a spontaneous transition of the system to the (ordered) quantum FM-like state, which leads to an increase in its energy while its magnetization keeps constant during the process.

We take advantage of the Cayley tree-like lattice to observe the SSB phenomena using the minimum amount of gates as possible. It is possible because our lattice is 2D, but the number of interactions in the system is significantly smaller than a square lattice, for example. In this way, we only need to simulate a small number of interactions, which allows us to efficiently observe SSB with a few blocks of digitized evolution. In fact, the topology of our superconducting device permits an efficient gate sequence of the circuit to simulate each block. The simulation of spin-spin interaction is done through two-qubit CZ gates and single-qubit rotations as depicted in Fig. 3a, with two parameters to be determined \({\phi }_{z,n}^{0}\) and φJ,n. For arbitrary functions \(f,g\in {\mathbb{R}}\), the parameters of the circuit, which Phase transition signature and formation of entangled quantum phases implements the evolution, are immediately obtained from \({\phi }_{z,n}^{l}={(-1)}^{l}{\omega }_{0}\tau f(\bar{{s}_{n}})\delta {s}_{n}\), and \({\varphi }_{J,n}={J}_{0}\tau g(\bar{{s}_{n}})\delta {s}_{n}\), where \({\phi }_{z,n}^{l}\) and φJ,n are dimensionless parameters associated with the initial local fields and interaction terms of the Hamiltonian, respectively. We simplify our circuit by defining a single parameter \({\phi }_{z,n}^{0}\) such that \({\phi }_{z,n}^{l}={(-1)}^{l}{\phi }_{z,n}^{0}\).

a Gate sequence for each block of the digitized circuit, describing how to encode the arbitrary parameters \({\phi }_{z,n}^{0}\) and φJ,n in the circuit to implement digitized CSB. Here we use the notation \({(\alpha )}_{\eta }={\hat{R}}_{\eta }(\alpha )={e}^{-i\alpha {\hat{\sigma }}_{\eta }/2}\). In (b), we show the experimental data of \({C}_{x}^{(i,j)}\) immediately after the nth block of a 5-block digitized circuit. The graphs are ordered from the state initialization (n = 0) to the final state (n = M = 5), respectively, showing the digitized evolution for the system initialized in (top) the ground state and (bottom) the highest excited state. c The behavior of the similarity with respect to the ideal digital process, obtained for each corresponding \({C}_{x}^{(i,j)}\) shown in (b). In (d), we present the profile of the range of \({C}_{x}^{3,k}={C}_{x}({r}_{3k})\) as a function of the Manhattan distance from the kth spin to spin 3, and the block step, for the ground and excited states.

Phase transition signature and formation of entangled quantum phases

We measure the two-point correlation function, which is defined as \({C}_{x}^{(i,j)}=\langle {\hat{\sigma }}_{i}^{x}{\hat{\sigma }}_{j}^{x}\rangle -\langle {\hat{\sigma }}_{i}^{x}\rangle \langle {\hat{\sigma }}_{j}^{x}\rangle\). Because of the isotropic aspect of the two-qubit correlations in the XY-plane, see Supplementary Note 1, without loss of generality we show the correlations only along the x-direction. Fig. 3b shows the behavior of the 2D profile of the correlations (\({C}_{x}^{(i,j)}\)), with respect to the two-spin sites (i, j), as a function of the nth block in the digitized circuit. So, we state one of our main results: while ferromagnetism and antiferromagnetism formation are forbidden for short-range interacting systems at any finite temperature13, these phases can be accessed through zero-temperature evolution by exploring adiabatically driven dynamics of a nearest-neighbor interacting spin-lattice. More than that, we also observe the signature of phase transition from uncorrelated classical AFM states to a correlated quantum FM-like phase state. In fact, the result shown in Fig. 3b–d is clear evidence of a dynamical symmetry breaking in the system. On the one hand, when we initialize the system in the ground state we see the emergence of the AFM phase of the XY Hamiltonian. On the other hand, by starting the system in the excited state, we achieve a final state consistent with a quantum-ordered FM-like phase state. This behavior is consistent with a phase transition from the classical AFM Néel state37 to the correlated FM-like state of the XY Heisenberg Hamiltonian, which is the signature of SSB induced during the evolution of the system.

Because the final Hamiltonian admits the existence of symmetries, at the final of the evolution the system energy spectrum is expected to be doubly degenerate, at minimum. Therefore, we state now that the existence of accessible states other than the target states cannot be populated along the evolution, and then destroy the formation of the correlated phases of the matter. In fact, it can be properly addressed by exploiting the symmetry of the system with respect to the eigenstate parity, defined as the expected value of the operator \({\hat{\Pi }}_{z}={\prod }_{l=0}^{L-1}{\prod }_{{n}_{l}=1}^{{N}_{l}}{\hat{\sigma }}_{{n}_{l}}^{z}\). As detailed in Supplementary Note 3, because \([{\hat{\Pi }}_{z},\hat{H}(s)]=0\), the conservation law for \({\hat{\Pi }}_{z}\) allows to efficiently address the final state because of the well-defined parity of each initial state as considered in Eq. (3). Therefore, degenerated states with different parity cannot be mixed during the evolution.

In order to quantify the impact of errors in the digitized circuit implementation, we compare the ideal and experimental correlation matrices. We define the similarity between the theoretical and experimental data as \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}=1-\mathop{\max }_{j,i}| {[{C}_{{{{\rm{the}}}}}-{C}_{\exp }]}_{j,i}| /2\), where [X]j,i is the element (i, j) of a given matrix X. The matrix Cthe is the theoretical prediction for the correlation matrix, with elements \({C}_{x}^{(i,j)}\), as provided by the numerical simulation of the digitized circuit, and \({C}_{\exp }\) is the corresponding correlation matrix computed with the experimental outcomes of the digitized circuit. As a result, the similarity \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}\) of the experimental realization with respect to the desired ideal result is shown in Fig. 3c. It is worth mentioning that the analysis of the similarity is not related to state fidelity, as it only quantifies the quality of the experimental data with respect to the theoretical one. However, by combining the result shown in Fig. 3c, with the energy estimate in Fig. 2b, and the two-point correlation profile in Fig. 3b, we can associate high values of \({{{\mathcal{S}}}}\) with SSB and a transition from the classical AFM to an FM-like phase state in our dynamics.

Our results lead to the conclusion that the experiment is mainly affected by the single and two-qubit gate errors (see Supplementary Note 4). However, even under the influence of such undesired effects, it is worth highlighting that the digitization of our 7-qubit scheme provides a final accuracy of around 80%. Additionally, as shown in Fig. 3b, c, by properly choosing the final time of the evolution, and the digitized step (for example n = 3 and n = 4), the emergence of the phase transition can be observed with enhanced sharpness. In other words, the formation of an ordered quantum FM-like phase state from the AFM classical state emerges early in the evolution (s < 1.0), so we could stop the digitized dynamics at n = 3 or n = 4 to reduce the accumulated errors. For example, the signature of SSB, as well as the formation of correlated quantum FM and AFM-like phase states, can be efficiently captured by the digital circuit after the second block with similarity around 90% (in case n = 2). The good performance of the circuit decomposition around the middle of the evolution in Fig. 3, also observed in Fig. 2d, can be justified by the small variations in the quantum adiabatic brachistochrone interpolation function used in the experimental circuit. This demonstrates the resilience of our digitized approach in simulating the relevant phenomenon under consideration. Thermal fluctuations primarily affect the initial quantum state preparation, and the quantum circuit evolution is relatively robust to such fluctuations, allowing us to observe the experimental phenomena (see Supplementary Table II).

We also investigate spin-spin correlation behavior as a function of the “distance” between the spins. To measure this quantity, we use the distance between two spins j and i given by the Manhattan distance rij = ∣sj − si∣, where the separation between two neighbor spins is d and the reference spin is the first spin of the 2nd generation, namely, spin 3. The graphical view of the Manhattan distance is presented in Fig. 3d, where our reference spin at the origin is highlighted. The main conclusion is that the profile of the correlations in our Cayley tree device differs from the long-range model observed for linear and 2D lattices15,16, where the FM phase exhibits a correlation length bigger than the AFM one due to the nature of AFM and FM spin states and symmetry breaks17,38.

To highlight the quantumness of the FM-like and AFM-like phase states observed in Fig. 3, we also analyze the increased quantum correlation in the system. To this end, we observe the formation of entanglement entropy as witnessed by the second-order Rényi entropy, given by \({S}_{{{{\rm{R}}}} {\acute {{{\rm{e}}}}} {{{\rm{nyi}}}}}(\hat{\rho })=-{\log }_{2}\left[{{{\rm{Tr}}}}({\hat{\rho }}^{2})\right]\), for bi-partitions of the tree lattice encoded in our device. The Rényi entropy reveals aspects of inseparability for both pure and mixed quantum states39, therefore it is used here as a witness of entanglement formation between two subsystems, say A and B, of a given system AB. More precisely, by denoting the output density matrix \({\hat{\rho }}_{{{{\rm{FM}}}}/{{{\rm{AFM}}}}}\) for the FM/AFM-like phase state, and the reduced density matrix \({\hat{\rho }}_{{{{\rm{FM}}}}/{{{\rm{AFM}}}}}^{A}\) of the subsystem A, \({S}_{{{{\rm{R}}}} {\acute {{{\rm{e}}}}} {{{\rm{nyi}}}}} ({\hat{\rho }}_{{{{\rm{FM}}}}/{{{\rm{AFM}}}}}) < {S}_{{{{\rm{R}}}} {\acute{{{\rm{e}}}}} {{{\rm{nyi}}}}} ({\hat{\rho }}_{{{{\rm{FM}}}}/{{{\rm{AFM}}}}}^{A})\) implies entanglement between the partition A and the rest of the system39,40,41, even if the system is not a pure state at the end of the experiment, the Rényi entropy can still be used as a witness of entanglement. Further details on the error corrections and Rényi entropy experimental measurements can be found in Supplementary Note 5. In the case of pure states, we have \({S}_{{{{\rm{R}}}} {\acute {{{\rm{e}}}} {{{\rm{nyi}}}}}} ({\hat{\rho }}_{{{{\rm{FM}}}}/{{{\rm{AFM}}}}})=0\), and therefore any quantity \({S}_{{{{\rm{R}}}} {\acute {{{\rm{e}}}}} {{{\rm{nyi}}}}}({\hat{\rho }}_{{{{\rm{FM}}}}/{{{\rm{AFM}}}}}^{A}) > 0\) implies entanglement.

The experimental evaluation of the Rényi entropy is done through randomized measurements42,43,44, carried out in our work as follows. We characterize all possible combinations of subsystems with NA qubits in A and 7−NA qubits in B. After the experiment circuits, we apply a product of single-qubit unitaries to all seven of our qubits, denoted as \(\hat{U}={\hat{u}}_{{q}_{0}}\otimes \ldots \otimes {\hat{u}}_{{q}_{6}}\). Each unitary \({\hat{u}}_{{q}_{i}}\) is independently drawn from the Circular Unitary Ensemble45. Subsequently, we measure the qubits in the σz-basis (computational basis). We perform multiple joint measurements with 10,000 shots on the whole system for each instance of U to gather statistical data, and we repeat this entire process for 100 different randomly selected instances of U. Using the data obtained through the above process and employing the statistical analysis methods provided in the literature44, we can obtain the second-order Rényi entropy \({S}_{{{{\rm{R}}}} {\acute {{{\rm{e}}}}} {{{\rm{nyi}}}}} ({\hat{\rho }}^{A})\) of any subsystem A with NA spins (qubits).

The Rényi entropy after correcting the noise effects is shown in Fig. 4, where each “cloud” in the graph denotes the Rényi entropy for all subsystems with the same size NA. Further details about error mitigation can be found in Supplementary Methods35. For each value of NA, we have c(NA) = 7!/NA!(7−NA)! points in the cloud due to the number of combinations for the bipartite decomposition A−B. For the case NA = 7, we only have one data point. The average value and the standard deviation for each cloud are highlighted. This analysis exposes that the correlations spread almost identically over the system for both the AFM-like and FM-like phase states from the top and bottom panels of Fig. 4, respectively, showing that the correlation range of both phases obeys the similar decay profile.

a The sequence of steps to measure the Rényi entropy is presented. After the adiabatic digitized circuit is implemented through the unitary digital operator \({\hat{U}}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}\), we apply random single-qubit unitaries to the output state and perform the joint measurement of the whole system on the computational basis. b, c Bipartite quantum correlations (Rényi entropy) of different choices of the subsystem A for each block of the digitized protocol (from n = 1 to n = 5), in cases where the system is initialized in the Néel ground state (b) and the Néel excited state (c). Each set of points corresponds to the Rényi entropy for a choice of the A subsystem obtained through the random measurements, where average values and their corresponding standard deviations are shown (horizontal and vertical bars). When considering the entire system (NA = 7), the dataset consists of a single point with a constant value of zero, because we employ the whole system Renyi entropy as a reference for error mitigation procedures.

Discussion

In this work, we have done theoretical and experimental investigations on zero-temperature SSB in a tree-like spin-spin interacting system with only nearest-neighbor interaction. While fundamental theorems forbid such a system to undergo a phase transition from the classical AFM Néel state to the quantum FM-like state induced by SSB at finite temperature, the results presented in the main text and Supplementary Methods35 suggest such a phenomenon is possible through zero-temperature adiabatic evolution. The quantumness of the FM-like phase state is witnessed through two-point correlation functions and the formation of entropy of entanglement as given by the second-order Rényi entropy. Since the applicability of our framework goes beyond the particular phenomenon studied here, we expect to observe SSB occurring for other geometries and structures, like regular 2D lattice, zigzag lattice, and others. For quantum simulation and computation, the sufficient condition for high-fidelity DAE is useful to achieve high-fidelity for digital adiabatic-inspired algorithms. As an alternative to QAOA46,47, DAE constitutes a promising strategy to build quantum circuits for the optimization process, but without classical optimization required by hybrid models of optimization. Therefore, it establishes a route to perform optimization tasks in quantum processors that cannot be used as quantum annealers.

Our results instigate further prospects on the simulation of physical systems and processes in digitized adiabatic quantum simulators. The challenges of the scalability of digitized annealing are mainly related to the accumulating errors due to limited gate fidelity. However, by employing efficient error mitigation techniques48,49,50, we expect to be able to extrapolate the application of digitized quantum annealing to larger quantum processors.

Methods

Digitized adiabatic theorem

We discuss here how the optimization of DAQC can be done through strategies to find the optimal adiabatic functions f(t) and g(t) responsible for driving the Hamiltonian between the initial (\({\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{ini}}}}}\)) and problem Hamiltonians (\({\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{fin}}}}}\)) according to the equation

In this case, we can write

By assuming that δsn is small enough to get a good approximation of the above equation, here we need to make sure that \({U}_{{{{\rm{dig}}}}}^{{{{\rm{std}}}}}({s}_{n+1};{s}_{n})\) can be decomposed in simple quantum gates. For example, it would be desirable to decompose the above unitary into two independent unitary associated to \({\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{ini}}}}}\) and \({\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{fin}}}}}\), we mean

with good approximation. However, because \([{\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{ini}}}}},{\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{fin}}}}}]\ne 0\), such a decomposition is not possible in general. To this end, here we develop a general condition over δsn in order to get such a decomposition. We use the Baker–Campbell–Hausdorff to write

From this equation, it is intuitive to say that if

then we can satisfy the approximation given in Eq. (8). Then, a sufficient (but not necessary) condition to get good fidelity with a single Trotter–Suzuki decomposition of the nth digitized block reads

Therefore, following the strategy of obtaining a general and robust condition for the adiabatic regime, we first assume the continuum of values for the above equation, replacing \({\bar{s}}_{n}\to s\) (minimizing over s is, at least, as good as minimizing over \({\bar{s}}_{n}\)), and we also consider an estimate of a reasonable total run time by invoking the condition for the adiabatic theorem to write

where \(\Delta (s)={\min }_{n,m| n\ne m}| {g}_{n}-{g}_{m}|\) is the minimum energy gap between different energy levels of the Hamiltonian spectrum. It is timely to mention that the above estimate also works for adiabatic Hamiltonians with spectral degeneracy, as Δ(s) is always smaller or equal to gnk(s), for any n and k, constructed by definition. In fact, as discussed in Refs. 51,52, because Δ(s) is computed for different energy levels n and m, we can deal with degenerate Hamiltonian because the possibility of zero-gap due to two degenerate states is taken into account in the theory.

Since the above condition needs to be satisfied for all sn in the digitized time domain, we can write it in a short way as

Therefore, we state the following theorem.

Theorem 1

Given an adiabatic Hamiltonian \(\hat{H}(s)=f(s){\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{ini}}}}}+g(s){\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{fin}}}}}\), a sufficient condition for DAT decomposition into first-order of the Suzuki–Trotter decomposition,

is given by

where \(\parallel \hat{A}\parallel=\sqrt{{{{\rm{tr}}}}({\hat{A}}^{{{\dagger}} }\hat{A})}\) is the Hilbert–Schmidt norm, and Δ(s) is the minimum instantaneous non-vanishing energy gap of \(\hat{H}(s)\).

The consequences of the digitized adiabatic theorem, as introduced in the main text, are: (i) It imposes a minimum value of the number of blocks M for high-fidelity digitization. In fact, as \(s={\sum }_{n=1}^{M}\delta {s}_{n}\) the above equation can also be used to determine M; (ii) The longer the adiabatic time τad, the bigger the number of blocks demanded for DAEs, establishing then a connection with validity conditions for adiabatic theorem in analog evolution; (iii) The approximated behavior of the adiabatic solution allows us to reduce the number of blocks by adequately managing the adiabaticity constraint over the total evolution time τad. (iv) The circuit complexity, given the available native gates of our device, is given by the quantum circuit that implements the interaction terms of \({\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{fin}}}}}\), since no optimization in the space of parameters of the circuit is required. On the other hand, the performance of the DAE may be optimized by finding the best functions f(s) and g(s), which are determined by quantum adiabatic brachistochrone trajectories and responsible for driving the system from the initial (\({\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{ini}}}}}\)) and problem Hamiltonians (\({\hat{H}}_{{{{\rm{fin}}}}}\)) at a short time interval τ ~ τad.

The above discussion also works even when the adiabatic Hamiltonian admits the existence of degenerated energy levels. To take these cases into account, let us first briefly discuss how to get the Eq. (12). To this end, we recall the validity conditions for the non-degenerated energy spectrum with53

where gnk(s) = Ek(s)−En(s) is the instantaneous minimum gap associated with the two eigenstates \(\left\vert {E}_{n}(s)\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert {E}_{k}(s)\right\rangle\). First, we observe that \(\parallel {d}_{s}H(s)\parallel \ge | \left\langle {E}_{n}(s)\right\vert {d}_{s}H(s)\left\vert {E}_{k}(s)\right\rangle |\), because \(| \left\langle {E}_{n}(s)\right\vert {d}_{s}H(s)\left\vert {E}_{k}(s)\right\rangle |\) is only a single element of the matrix dsH(s), so we can super-estimate the inequality above by substituting the maximization over the off-diagonal matrix elements \(| \left\langle {E}_{n}(s)\right\vert {d}_{s}H(s)\left\vert {E}_{k}(s)\right\rangle |\) by the norm of the Hamiltonian as \(| \left\langle {E}_{n}(s)\right\vert {d}_{s}H(s)\left\vert {E}_{k}(s)\right\rangle | \to \parallel {d}_{s}H(s)\parallel\). To end, because Δ(s) is, by definition, the minimum energy gap, it is always smaller or equal to gnk(s), for any n and k. In this way, we estimate τad by doing gnk(s) = Δ(s)33. Using these two observations in the above equation, we get Eq. (12).

Now, the generalization of our estimate for the adiabatic time to systems with spectral degeneracy can be done if we take start from the adiabatic condition for degenerate systems. In fact, consider the eigenvalue equation \(H(s)\left\vert {E}_{k}^{{d}_{k}}(s)\right\rangle={E}_{k}(s)\left\vert {E}_{k}^{{d}_{k}}(s)\right\rangle\), where we introduce the index dk = {1, 2,⋯, Nk} to denote the set of Nk eigenstates of the degenerate subspace of energy Ek(s). By doing that, the condition in Eq. (16) is modified as

where the additional maximization \({\max }\) is done over the degenerate subspaces \(\{\vert {E}_{k}^{{d}_{k}}\rangle \}\) and \(\{\vert {E}_{n}^{{d}_{n}}\rangle \}\). So, by using the same analysis as before, we can estimate the \({\tau }_{{{{\rm{ad}}}}}^{{{{\rm{deg}}}}}\) from Eq. (12).

Decomposing Heisenberg interaction in fundamental gates

As a fundamental part of the adiabatic digitizing considered in this work, we show now how to get the circuit to simulate pair-wise interactions of the Hamiltonian \({\hat{H}}_{Tree}\). See Ref. 36 for more details on how to simulate Hamiltonian evolutions using fundamental quantum gates. For the particular case of interest to our work, let us write the Hamiltonian in Eq. (4) as

where we have the interaction term for two arbitrary qubits (n, k)

As part of the approximation for digitization, we assume the system evolution operator U(tℓ, tℓ−1) reads

where we define the dimensionless parameter (angle) ϕℓ = J0(tℓ, tℓ−1). Therefore, we just need to show how to implement the two-qubit unitary given by \({U}_{n,k}({\phi }_{\ell })=\exp \left(-i{\hat{h}}_{n,k}{\phi }_{\ell }\right)\). At this point, because \({\hat{h}}_{n,k}\) can be analytically diagonalized we find

From this equation, we observe that the structure of the operator Un,k(ϕℓ) is similar to the structure of an iSWAP gate

So, it means that Un,k(ϕℓ) can be efficiently simulated using iSWAP as the two-qubit gates. In fact, we can observe that this operator can be decomposed as single-qubit rotations and the iSWAP gate as

where \({\hat{R}}_{\eta }(\alpha )={e}^{-i\alpha {\hat{\sigma }}_{\eta }/2}\). However, by using the relation between iSWAP and the CZ gate we get the more efficient decomposition (less gates) as

Correcting noise effects on entanglement generation

Due to noise effects during the experimental implementation, the output data needs to be properly treated in order to provide the correct output entanglement entropy. We first consider that the noise causes a uniform entropy growing over the system as a whole. In this way, the noise effects correction is done by measuring the entropy of the whole system S(ρ)54 and then subtracting it from the original experimental entropy (including the uniform system noise). So, consider that at a given time t one gets the original experimental data S(ρ), then the uniform noise rate contributes as R = S(ρ)/N43,55, where N is the total number of qubits. Now if we measure the entropy of the subsystem A and obtain S(ρA), and the subsystem size is NA, we can correct it according to the equation below

Data availability

All data that support this work are available in the main text or in the supplementary information. Source data are provided with the paper. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The codes are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Noether, E. “Invariante variationsprobleme”, Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen. Math. Phys. Kl. 1918, 235–257 (1918).

Higgs, P. W. Broken symmetries and the masses of gauge bosons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 13, 508–509 (1964).

Guralnik, G. S., Hagen, C. R. & Kibble, T. W. B. Global conservation laws and massless particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 13, 585–587 (1964).

Sigrist, M. & Ueda, K. Phenomenological theory of unconventional superconductivity. Rev. Mod. Phys. 63, 239–311 (1991).

Anderson, P. W. Basic Notions of Condensed Matter Physics 2nd edn (Westview Press, 1997).

Poulsen, K., Santos, A. C. & Zinner, N. T. Quantum Wheatstone bridge. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 240401 (2022).

Kannan, B. et al. On-demand directional microwave photon emission using waveguide quantum electrodynamics. Nat. Phys. 19, 394–400 (2023).

Díez-Mérida, J. et al. Symmetry-broken Josephson junctions and superconducting diodes in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nat. Commun. 14, 2396 (2023).

Sadler, L., Higbie, J., Leslie, S., Vengalattore, M. & Stamper-Kurn, D. Spontaneous symmetry breaking in a quenched ferromagnetic spinor Bose–Einstein condensate. Nature 443, 312–315 (2006).

Sachdev, S. Quantum Phase Transitions 2nd edn (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Lu, L. et al. Magnetism and local symmetry breaking in a Mott insulator with strong spin orbit interactions. Nat. commun. 8, 14407 (2017).

Trenkwalder, A. et al. Quantum phase transitions with parity-symmetry breaking and hysteresis. Nat. Phys. 12, 826–829 (2016).

Mermin, N. D. & Wagner, H. Absence of ferromagnetism or antiferromagnetism in one- or two-dimensional isotropic heisenberg models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 17, 1133–1136 (1966).

Bruno, P. Absence of spontaneous magnetic order at nonzero temperature in one- and two-dimensional Heisenberg and XY systems with long-range interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 137203 (2001).

Feng, L. et al. Continuous symmetry breaking in a trapped-ion spin chain. Nature 623, 713–717 (2023).

Chen, C. et al. Continuous symmetry breaking in a two-dimensional Rydberg array. Nature 616, 691–695 (2023).

Maghrebi, M. F., Gong, Z.-X. & Gorshkov, A. V. Continuous symmetry breaking in 1d long-range interacting quantum systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 023001 (2017).

Walker, M. B. & Ruijgrok, T. W. Absence of magnetic ordering in one and two dimensions in a many-band model for interacting electrons in a metal. Phys. Rev. 171, 513–515 (1968).

Gelfert, A. & Nolting, W. Absence of a magnetic phase transition in Heisenberg, Hubbard, and Kondo-lattice (s-f) films. Phys. Status Solidi B 217, 805–818 (2000).

Gelfert, A. & Nolting, W. The absence of finite-temperature phase transitions in low-dimensional many-body models: a survey and new results. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 13, R505 (2001).

Beekman, A. J., Rademaker, L. & van Wezel, J. An introduction to spontaneous symmetry breaking. SciPost Phys. Lect. Notes 11 (2019).

Block, M., Bao, Y., Choi, S., Altman, E. & Yao, N. Y. Measurement-induced transition in long-range interacting quantum circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 010604 (2022).

Nernst, W. “Ueber die Berechnung chemischer Gleichgewichte aus thermischen Messungen”. Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen. Math. Phys. Kl. 1906, 1–40 (1906).

Masanes, L. & Oppenheim, J. A general derivation and quantification of the third law of thermodynamics. Nat. Commun. 8, 1–7 (2017).

King, A. D. et al. Quantum annealing simulation of out-of-equilibrium magnetization in a spin-chain compound. PRX Quantum 2, 030317 (2021).

King, A. D. et al. Quantum critical dynamics in a 5,000-qubit programmable spin glass. Nature 617, 61–66 (2023).

Barends, R. et al. Digitized adiabatic quantum computing with a superconducting circuit. Nature 534, 222 (2016).

Farhi, E. et al. A quantum adiabatic evolution algorithm applied to random instances of an np-complete problem. Science 292, 472–475 (2001).

Benioff, P. The computer as a physical system: a microscopic quantum mechanical Hamiltonian model of computers as represented by Turing machines. J. Stat. Phys. 22, 563–591 (1980).

Benioff, P. Quantum mechanical Hamiltonian models of Turing machines. J. Stat. Phys. 29, 515–546 (1982).

Deutsch, D. Quantum theory, the Church–Turing principle and the universal quantum computer. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 400, 97–117 (1985).

Kato, T. On the adiabatic theorem of quantum mechanics. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 5, 435–439 (1950).

Rezakhani, A. T., Kuo, W.-J., Hamma, A., Lidar, D. A. & Zanardi, P. Quantum adiabatic brachistochrone. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 080502 (2009).

Santos, A. C., Villas-Boas, C. J. & Bachelard, R. Quantum adiabatic brachistochrone for open systems. Phys. Rev. A 103, 012206 (2021).

See Supplemental Material at [URL will be inserted by publisher] for details of the superconducting chip used in our study and complementary theoretical discussions on the continuous symmetry breaking in linear and tree-like spin chains.

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information: 10th Anniversary Edition 10th edn (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Néel, M. L. Propriétés magnétiques des ferrites ; ferrimagnétisme et antiferromagnétisme. Ann. Phys. 12, 137–198 (1948).

Peter, D., Müller, S., Wessel, S. & Büchler, H. P. Anomalous behavior of spin systems with dipolar interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 025303 (2012).

Horodecki, R. & Horodecki, M. Information-theoretic aspects of inseparability of mixed states. Phys. Rev. A 54, 1838–1843 (1996).

Horodecki, M., Horodecki, P. & Horodecki, R. Separability of mixed states: necessary and sufficient conditions. Phys. Lett. A 223, 1–8 (1996).

Horodecki, R., Horodecki, P., Horodecki, M. & Horodecki, K. Quantum entanglement. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 865–942 (2009).

van Enk, S. J. & Beenakker, C. W. J. Measuring \({{{\rm{Tr}}}}{\rho }^{n}\) on single copies of ρ using random measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 110503 (2012).

Elben, A., Vermersch, B., Dalmonte, M., Cirac, J. I. & Zoller, P. Rényi entropies from random quenches in atomic Hubbard and spin models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 050406 (2018).

Brydges, T. et al. Probing Rényi entanglement entropy via randomized measurements. Science 364, 260–263 (2019).

Mezzadri, F. How to generate random matrices from the classical compact groups. Not. Am. Math. Soc. 54, 592–604 (2007).

Farhi, E., Goldstone, J. & Gutmann, S. A quantum approximate optimization algorithm. arXiv e-prints arXiv:1411.4028 (2014).

Farhi, E., Goldstone, J., Gutmann, S. & Zhou, L. The quantum approximate optimization algorithm and the Sherrington-Kirkpatrick Model at infinite size. Quantum 6, 759 (2022).

Kandala, A. et al. Error mitigation extends the computational reach of a noisy quantum processor. Nature 567, 491–495 (2019).

Kim, Y. et al. Scalable error mitigation for noisy quantum circuits produces competitive expectation values. Nat. Phys. 19, 752–759 (2023).

Kim, Y. et al. Evidence for the utility of quantum computing before fault tolerance. Nature 618, 500–505 (2023).

Sarandy, M. S. & Lidar, D. A. Adiabatic approximation in open quantum systems. Phys. Rev. A 71, 012331 (2005).

Jansen, S., Ruskai, M.-B. & Seiler, R. Bounds for the adiabatic approximation with applications to quantum computation. J. Math. Phys. 48, 102111 (2007).

Sarandy, M. S., Wu, L.-A. & Lidar, D. A. Consistency of the adiabatic theorem. Quantum Inf. Process. 3, 331–349 (2004).

Vovrosh, J. et al. Simple mitigation of global depolarizing errors in quantum simulations. Phys. Rev. E 104, 035309 (2021).

Vermersch, B., Elben, A., Dalmonte, M., Cirac, J. I. & Zoller, P. Unitary n-designs via random quenches in atomic Hubbard and spin models: application to the measurement of rényi entropies. Phys. Rev. A 97, 023604 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the useful discussions with Z. Liu and F. Yan. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (11934010, 12205137, 12004167), the Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (Grants No. 2018B030326001 and 2020B0303030001), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grants No. 2020M671861 and 2021T140648), the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory (Grant No. 2019B121203002), Technology and Innovation Commission of Shenzhen Municipality (KQTD20210811090049034), the Innovation Program for Quantum Science and Technology (Grant No. 2021ZD0301703). K.P. and N.T.Z. acknowledge funding from The Independent Research Fund Denmark DFF-FNU. A.C.S. is supported by the Comunidad de Madrid through the research funding program Talento 2024 “César’ Nombela”, under Grant No 2024-T1/COM-31530. A.C.S. acknowledges the partial financial support by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) (Grant No. 2019/22685-1), by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 FET-Open project SuperQuLAN (899354) and Comunidad de Madrid Sinérgicos 2020 project NanoQuCo-CM (Y2020/TCS-6545).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.T. and D.Y. supervised the project. C.-K.H. designed the devices and conducted the measurements with assistance from G.X., J.C., C.L., R.Z., H.Y., S.Y. S.L., and D.T. C.-K.H. and D.T. conceived and designed the experiment. Y.Z. fabricated the devices supervised by S.L. A.C.S., K.P., and N.T.Z. developed the theory, and A.C.S. and K.P. did the theoretical simulations to fit the experimental data. A.C.S. supervised the project from the theoretical aspect. A.C.S., C.-K.H., and D.T. wrote the manuscript with feedback from all the authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Shingo Kono, Shi-Ju Ran, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, CK., Xie, G., Poulsen, K. et al. Digital simulation of zero-temperature spontaneous symmetry breaking in a superconducting lattice processor. Nat Commun 16, 3289 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57812-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57812-8