Abstract

The Lewis acid-catalyzed tittle reaction of 1,3-dicycloalkenlidine ketones is recognized as so far the shortest and most effective 1-step method for construction of angular tricyclic scaffolds, which are extensively found in bioactive terpenoids. Here, a further kinetic study of this reaction with 30 reaction examples is carried out using in situ IR technology and DFT calculation. That enables the creation of well-fitted linear relationships of lnk/(ΔG1‡/T), ΔG1‡/ΔG2, ln(k/kH)/σp, reflecting the structure′s effect on reactivity/selectivity, and validating the reaction mechanism. Particularly highlighted is that substituents C1-R1/C3-R2 activate this reaction in the order: alkyl ≈ aryl >> aryl S-, halogen, alkyl O-, and alkyl N-. While electron-withdrawing R1/R2 will inactivate this reaction. When R1 = R2 = Me and m = 4, the reactivity of n-membered substrates follow the order of ring′s size: 3 > 4 > 7 > 6 > 5. Then, DFT calculations combined with machine learning algorithms establish a prediction model for first cycloexpansion (i e. regioselectivity). Electron-donating R1/R2 can direct preferentially the first cycloexpansion of its near ring in the order: alkyl > aryl > halogen ≈ alkyl O- > alkyl N- > aryl S-, which can be fitted into the relationship as ΔΔG/(ΔΔG-R1, ΔΔG-R2, ΔΔG-m, ΔΔG-n) or ΔΔG/(m-rse, m-ra, n-rse, n-ra, R1-σp, R2-σp). When R1 and R2 show the similar electronic effect, the first cycloexpansion of m/n takes place in the order of ring′s size: 4 > 5 > 6, 7, 8 > 3. Six examples are successfully validated by model prediction and then experiment. In this work, structure-reactivity relationship and regioselectivity predicting model are established.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Development of the reaction capable of reorganizing multiple C–C single bonds to rapidly construct the core, complexity as well as diversity of bioactive organic molecules, is of great importance in the fields of synthesis science, biology and medicine. The angular tricycles are one of the crucial cores which have three carbon-rings fused with one quaternary carbon center1,2. They exist extensively in and have the substantial bioactive contribution to bioactive polycyclic molecules3,4,5,6, such as the terpenoids and their related lactones, lactams and alkaloids7,8,9. Since 1970′s, chemists have been making efforts to synthesize the angular tricyclic molecules and relatives for the chemistry, biology and medicine researches. However, these strategies developed usually suffer from a difficult construction of the key angular tricycles, because of their inherent rigidity and hindrance, and thus stepwise approaches have to be used in most cases10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Recently we have developed so far the most efficient 1-step method to access these scaffolds (Fig. 1), which involves remarkably a synergistic cascade reorganization of several C–C single bonds of 1,3-cycloalkenylidine ketone substrates. Further advantages include: catalytic effective with various Lewis acids, high yields (> 90%) and short reaction time (0.5–12 h) in many cases, broad scope and easy availability of substrates, as well as mild conditions and convenient operation. This reaction has efficiently been applied by our team to synthesize a series of complex natural bioactive polycyclic terpenoids with angular tricycles17,18,19,20. In addition, a qualitative substitution/ring strain effect and reaction mechanism involving an initial rate-determining 4π-electrocyclization have primarily been investigated (Fig. 1). In order to further insight into its structure-property, especially the reactivity and regioselectivity, so as to achieve its broad and efficient utility in synthetic chemistry, herein we continue to conduct an in-depth kinetic study of this reaction by use of in situ IR technology and DFT calculations. As a powerful tool for seeking inner correlation between molecule structural factors and chemical reaction behaviors (i.e., yields, selectivity, reactivity), machine learning is now gradually used for chemical science21,22,23,24,25,26,27. Here this method is used, for the first time, to explore the regioselectivity prediction model of the tittle reaction.

For establishing the quantitative relationships of structure-reactivity/regioselectivity, the reaction rate constants k data were measured using in situ IR technique28,29,30 together with 1H qNMR analysis31,32,33. The free energy ΔG1‡ of the initial 4π-electrocyclization transition state d and formation energy ΔG2 of allylic carbocation e were calculated out using DFT, together with Hammett constant σp34, to express structure variants of substrates. Well-fitted linear relationships of lnk/(ΔG1‡/T), ΔG1‡/ΔG2, ln(k/kH)/σp and some more crucial kinetic parameters of this reaction were also obtained. The ΔΔG data of all allylic carbocation intermediates e were obtained by DFT calculations to determine priority of the first cycloexpansion and summarized into training set, whereafter Support Vector Regression (SVR), Neural Network (NN) and Linear Regression algorithms (LR) and so on were applied to train the training set24,35,36 to establish a model for predicting the reaction regioselectivity. 120 virtual examples were trained by the algorithms, and six selected substrates 15a, 28a–32a19 were validated for the reliability of this model. This model was verified practical for designing suitable reactants to obtain desired angular tricyclic skeletons and foreseeing reaction processes and experimental results. Here, we show a kinetic study based on in situ IR and DFT, and regioselectivity prediction by combination of DFT with machine learning algorithms.

Results

Design of substrates′ scope

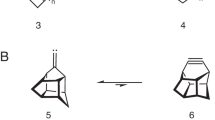

Our broad research began with the preparation of substrates 1a–30a via simple aldol condensation/dehydration from ketone and cycloalkanone material17,19, which were classified as 6 represented groups according to their structure variation. The 1st (1a–5a) group was designed to examine the σ→π electronic donating effect of alkyls R1/R2 on π-system; the 2nd (10a–15a, 26a–27a) group with aryls, carbonate esters, or cyano for examining the π→π conjugative effect; the 3rd with arylthios (16a–21a) and 4th group with halogen (F, Cl, Br) (23a–25a) for examining the heteroatomic substituent′s n→π and σ←π effect; the 5th group (1a, 6a–9a) for examining the ring′s strain/size effect (m = 4, n = 3–7). Six examples (15a, 28a–32a) were subjected to subsequent validation of prediction model of regioselectivity (i.e., cycloexpansion priority of m vs. n). All rate constants and corresponding ΔG1‡ values were summarized in Table 1 (see Supplementary Table 4 in SI for details).

Kinetic study for acquisition of rate constants k

Rate constants k data were indirectly obtained through reaction rate equation. Thus the reaction order of this cascade reaction should be firstly studied. Taking the reaction of 1a to 1b (R1 = R2 = Me, m = n = 4, Fig. 1) to exemplify the procedure, we obtained initially the characteristic IR absorption of 1a and 1b in CHCl3 at 1618 cm−1 and 1659 cm−1 (Fig. 2a), respectively. By converting the absorbance-time relationship of 1b into its concentration-time relationship, the cross-section could be obtained (black curve in Fig. 2b), representing yield of 1b rising along with reaction time increasing.

The kinetic reaction order could be obtained by varying the initial concentrations [In(SbF6)3]0 and [1a]0 of catalyst and substrate 1a, respectively. In the tests, [In(SbF6)3]0 in the black and red curves were the same but their [1a]0 data were different. And the calculated reaction rates for yielding 1b in the black and red curves were 4.82 × 10−4 M•s−1 and 5.06 × 10−4 M•s−1, respectively. Their small difference suggested that the reaction was of a zero-order kinetic dependence on [1a] of substrate a. By varying [In(SbF6)3]0 from 0.02 to 0.01 M, the calculated reaction rate for yielding 1b in the blue curve was 2.39 × 10−4 M•s−1, which was about 1/2 of the reaction rate in the black curve, indicating that the reaction was of a first-order kinetic dependence on [In(SbF6)3] of catalyst. Accordingly, the rate equation could be expressed as kobs = k[In(SbF6)3]1[a]0, where kobs was the reaction rate for generating product b and k was the rate constant. The detail experimental operation and calculation procedure, and the full data obtained were summarized in SI (Supplementary Information, Supplementary Table 4) attached. Altering the reaction temperature, activation enthalpy ΔH≠ was calculated as 18.4 kcal/mol and activation entropy ΔS≠ as −7.2 cal•(K•mol)−1 from Eyring equation. Notably, the negative ΔS≠ value indicated the 4π electrocyclization process was rate-determining step.

Quantitative structure-reactivity relationship

All the rate constants k were measured via in situ IR experiments. DFT calculations of all examples also presented the highest energy barriers ΔG1‡ for the initial 4π-electrocyclization in their corresponding reaction process, demonstrating this cyclization was the rate-limiting step. Thus the relationship between lnk and ΔG1‡/T was plotted in Fig. 3a, which revealed that all substrates 1a–30a followed two well-fitted (R-Squares: 0.938 and 0.947) linear relationships in blue and red with slopes of −343.2 and −155.2, respectively, though they were initially classified as six different groups. In detail, the reactivity of substrates 16a–21a, 23a–25a and 28a with n→π electron donating but σ←π withdrawing effects of heteroatom-based substituents (phenylthio, halogen and thienyl) followed the blue linear dots with a bigger slope of −343.2, which indicated that their reactivity shall show more sensitive to reaction temperature. Interestingly, in this series, the reactivity for the stronger electron-withdrawing arylthio-substitutions was reversely higher than that of the stronger electron-donating (e.g., p-CF3C6H4S > p-ClC6H4S ≈ p-FC6H4S > PhS > p-MeC6H4S > 2-Thiofenyl > p-MeOC6H4S). While the reactivity of other substrates 1a–15a, 22a, 26a–27a with various carbon-based substitutions (alkyls, aryls, carbonate ester, cyano) or with ring-size′s variation of m/n (= 3–7) followed the red linear dots with a smaller slope of −155.2. And the stronger electron-donating substituents R1/R2 showed higher activation ability, displaying the order: i-Pr > Et > Me; p-OMeC6H4 > p-MeC6H4 > Ph > p-FC6H4 > p-ClC6H4 > p-CF3C6H4). Electron-donating effect of substituent on benzene rings of aryl (red) or thiophenyl (blue) substrates showed a quite different tendency on chemical reactivity, possibly due to the substituents′ disparate electronic induction directions. For the red line, carbon-based substituents always showed the π→π electron donating effect. While for blue line, different heteroatom-based substituents showed different total electron effect of σ←π and n→π. Hammett analysis was done to explore the linear relationship between ln(k/kH) of the aryl and thiophenyl substrates and σp of respective Rp, which was displayed in SI. When R2 = Me, m = 4 and n varied from 3 to 7, the highest reactivity was observed for the substrate with n = 319.

Two substrates 29a and 30a with the same Ph and different cycloalkyl sizes were applied to foresee their reactivity (green dots). The DFT calculation results indicated their reactivity shall follow the red dots, which was in agreement with latter experimental fact. Comparison of k data (29a vs 8a, 30a vs 7a) showed that the Ph′s substitution could highly promote reactivity regardless of Ph was at same or different side of larger rings (m/n = 5, 6). Two sets of kinetic experiments with substrates bearing active C3-MeO or BocHN failed to give reaction rate constant k. In the case of R1 = Me, R2 = OMe, m = n = 4, reaction gave the overlapped signals of in situ IR. While R2 = BocHN, substrate was too inactive under the standard condition to give the detectable signals within the measurable region of IR-spectrometer, possible due to the association of Lewis acid with the active N-atom of BocHN, that deactivated the catalysis.

Moreover, the stability of allylic carbocations e was evaluated by their formation energy ΔG2. The linear correlation between ΔG1‡ and ΔG2 (R-Square = 0.874) was found (Fig. 3b), indicating that the more stable allylic carbocation intermediate e was more likely to be formed and proceeding the subsequent ring expansion, which was to some extent more favorable to conduct higher reactivity of 4π-electrocyclization processes. Generally, weak electron donating effect of aryl, alkyl groups could stabilize allylic carbocation e, while the σ←π electron withdrawing effect of heteroatomic groups (blue curve in Fig. 3b) might reduce the reactivity of substrates by weakening the stability of allylic carbocations. This accounts for why two different fitting curves were found in Fig. 3a.

Prediction of cycloexpansion priority

In order to predict the reaction regioselectivity (cycloexpansion priority of m vs. n), DFT calculations combined with ML algorithms modeling were performed to construct a prediction model, which was then validated by experiment. As shown in Fig. 4a, the cycloexpansion of allylic carbocation intermediate e could be initiated either from left ring (m) or the right (n), leading to two different regioisomeric products (in blue or dark red, respectively). Thus training sets including the features ΔΔG-m, ΔΔG-n, ΔΔG-R1 and ΔΔG-R2 (or the features m-rse, m-ra, n-rse, n-ra, R1-σp, R2-σp, see SI for details) of these allylic carbocation intermediates were obtained by DFT calculations. For the substitution effect of R1, provided that R2 = Me, m = n = 4, the energy barrier ΔΔG-R1 ( = ΔG-R1– ΔG-Me, Fig. 4b) would determine if its nearest m ring will take the first expansion. Similarly, for ring-strain′s effect of m, provided that R1 = R2 = Me, n = 4, the energy barrier ΔΔG-m ( = ΔG-m – ΔG-4) would determine if the m ring will take the first expansion. The training sets containing 120 virtual examples by DFT calculations were further trained by Random Forest (RF), Neural Network (NN), Support Vector Regression (SVR) algorithms and so on, and the mathematical model could be constructed to predict the more favorable product. When the algorithms output the positive (or negative) value, the first cycloexpansion of the right n (or left m) ring was predicted to take place. As shown in Fig. 4c, the 5-fold cross-validation of all the ML algorithms suggested SVR method showed best performance in R-square (0.979) and smallest MAE (0.691). Thus SVR could be used to predict priority of the first cycloexpansion. In Fig. 4d, experimental validation of six substrates (15a, 28a–32a) was carried out as test set to examine the reliability of the prediction model. Fortunately, all the outputs predicted by SVR algorithm well matched the experimental results, as directional distributions of the horizontal bars suggested (Fig. 4d). Additionally, the predicted result based on SVR algorithm was consistent with that calculated out by DFT. The left (or right) distribution meant left ring m (or right ring n) took the first cycloexpansion (Fig. 4d). Particularly applicable was the regioselectivity prediction for 30a, which had the favorable Me and cyclobutyl located at the competing left and right sites, respectively, and its cycloexpansion priority was hard to predict based on our general experience.

a Framework for predicting priority of cycloexpansion (m vs n) by DFT calculations combined with ML algorithms; b Explanations of generating features ΔΔG-R1/R2, ΔΔG-m/n and ΔΔG, LA = In(SbF6)3; c Performance of ML algorithms for regioselectivity predicting; d Reliability testing of SVR algorithm′s outputs.

Discussion

Based on the research evidences obtained above using in situ IR technology, DFT calculations and machine learning algorithms, together with some results we previously reported, we have achieved the linear structure-reactivity relationship and structure-regioselectivity prediction model of tittle cascade reaction generating angular tricycles. The structure affections mainly involve the σ-π, n-π, and/or π-π electron effect of C1, C3-substituents (R1, R2) on the 4π- system, as well as the ring′s strain (or size) of two rings (m, n) to be expanded. The combination work of in situ IR measurement and DFT calculations reveals that reactivity of this 4π electrocyclization process is mainly affected by electronic properties of R1/R2 and steric hindering of m/n. While machine learning modeling based on DFT calculations suggests the cycloexpansion priority is primarily determined by competitive effect of electronic property of R1/R2 versus the ring′s strain of m/n. Actually, in the case m, n = 6, 7 or 8, reactivity of the tittle cascade reaction is rather low and no expected reaction product can be detected19. For these large size ring substituted ketones, 4π electrocyclization might not be rate-determining step, and cycloexpansion processes were hard to occur. When smaller size ring presents as m or n = 4, 5, reaction is active enough. While cyclopropyl (m or n = 3) is designed to induce first cycloexpansion, no reaction is observed, as it releases only small amount of energy from 3- to 4-membered ring, and the latter is still an unfavorable strained ring system. Fortunately, the relationship of lnk/(ΔG1‡/T), ΔG1‡/ΔG2, ln(k/kH)/σp and ΔΔG/(ΔΔG-R1, ΔΔG-R2, ΔΔG-m, ΔΔG-n) or ΔΔG/(m-rse, m-ra, n-rse, n-ra, R1-σp, R2-σp) are able to explain and predict the reaction reactivity and regioselectivity of ordinarily used 4-6-membered ring systems. Further study of this project is going in our group.

Methods

General information

The reactions were performed using oven-dried glassware equipped with a magnetic stir bar under an atmosphere of argon if without otherwise noted. Reagents purchased from commercial suppliers were directly used without further purification. Extra dry solvents used for preparation of starting materials were obtained by standard operating method: toluene, tetrahydrofuran, diethyl ether (Et2O) were distilled from sodium and dichloromethane (DCM) was distilled from calcium hydride, excerpt for commercially available solvents. Analytically pure chloroform (CHCl3) was treated with concentrated sulfuric acid (V(CHCl3): V(H2SO4) = 20: 1) to remove the stabilizer, dried by anhydrous CaCl2 grains overnight, distilled under argon protection and stored in a dark place to give freshly prepared chloroform (CHCl3) solvent for in situ IR measurements. Thin-layer chromatography was performed with EMD silica gel 60 F254 plates eluting with solvents indicated, visualized by a 254 nm UV lamp and stained with phosphomolybdic acid (PMA). 1H NMR, 13C NMR spectra were obtained on Bruker AM-400, Bruker AM-500, or Bruker AM-600. Chemical shifts (δ) were quoted in ppm relative to tetramethylsilane or residual un-deuterated solvent as internal standard (CDCl3: 7.26 ppm for 1H NMR, 77.00 ppm for 13C NMR), and multiplicities were as indicated: s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet, dd = doublet of doublet, td = triplet of doublet, ddd = doublet of doublet of doublet. The IR spectra were recorded on Nicolet FT-170SX spectrometer. High-resolution mass spectral analysis (HRMS) data were measured on the Bruker ApexII by means of ESI technique. The in situ IR experiments were recorded on Mettler Toledo React IR 4000 spectrometer using a 6.3 mm AgX diamond comb.

General procedure for the in situ IR experiments

Purified starting material a (0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv) was loaded into reaction tube without solvent, filled with pure argon and cooled to 0 °C in ice-bath, then the background spectrum was collected keeping no contact between starting material and probe. CHCl3 (0.20 mL) was injected into the reaction tube and newly prepared In(SbF6)3 solution (4.4 mg InCl3 and 20.6 mg AgSbF6 dissolved in 0.80 mL CHCl3, 0.02 mmol, 0.1 equiv) was subsequently cooled in ice-bath for 10 mins. The In(SbF6)3 solution was rapidly injected into solution of a under argon protection, simultaneously the record started. The measurement finished when formation of b reached chemical equilibrium. The reaction mixture was filtered in air to remove solid phase, washed by CH2Cl2 (5 × 10 mL), and 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene (16.8 mg, 0.10 mmol) was added as internal standard. The reaction mixture was concentrated under vacuum to determine the content of b by quantitative NMR method (γ was obtained from 1H qNMR yield31,32,33 and k was calculated from Supplementary Equation (2)).

Data availability

The data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information or Source Data file. The experimental procedures, data of NMR, IR and HRMS have been deposited in SI. All other data are available in the main text, or from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

A Python source code implementation of the model and all data needed to reproduce model development are available at https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.9415061.v1.

References

Talele, T. T. Opportunities for tapping into three-dimensional chemical space through a quaternary carbon. J. Med. Chem. 63, 13291–13315 (2020).

Lovering, F., Bikker, J. & Humblet, C. Escape from flatland: increasing saturation as an approach to improving clinical success. J. Med. Chem. 52, 6752–6756 (2009).

Mehta, G. & Srikrishna, A. Synthesis of polyquinane natural products: an update. Chem. Rev. 97, 671–720 (1997).

Kotha, S. & Keesari, R. R. A modular approach to angularly fused polyquinanes via ring-rearrangement metathesis: synthetic access to cameroonanol analogues and the basic core of subergorgic acid and crinipellin. J. Org. Chem. 86, 17129–17155 (2021).

D’yakonov, V. A., Trapeznikova, O. G. A., de Meijere, A. & Dzhemilev, U. M. Metal complex catalysis in the synthesis of spirocarbocycles. Chem. Rev. 114, 5775–5814 (2014).

Xu, G. et al. Przewalskin B, a novel diterpenoid with an unprecedented skeleton from salvia przewalskii maxim. Org. Lett. 9, 291–293 (2007).

White, J. D. & Ihle, D. C. Tandem photocycloaddition-retro-mannich fragmentation of enaminones. A route to spiropyrrolines and the tetracyclic core of koumine. Org. Lett. 8, 1081–1084 (2006).

Crimmins, M. T. et al. The total synthesis of (±)-ginkgolide B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 8453–8463 (2000).

Hirst, G. C., Johnson, T. O. Jr & Overman, L. E. First total synthesis of Lycopodium alkaloids of the magellanane group. Enantioselective total syntheses of (−)-magellanine and (+)-magellaninone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115, 2992–2993 (1993).

Thaharn, W., Soorukram, D., Kuhakarn, C., Reutrakul, V. & Pohmakotr, M. Synthesis of C2-symmetric gem-difluoromethylenated angular triquinanes. J. Org. Chem. 83, 388–402 (2018).

Amberg, W. M. & Carreira, E. M. Enantioselective total synthesis of (+)-Aberrarone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 15475–15479 (2022).

Pallerla, M. K. & Fox, J. M. Enantioselective synthesis of (−)-Pentalenene. Org. Lett. 9, 5625–5628 (2007).

Huang, Z.-H. et al. Total syntheses of Crinipellins enabled by cobalt-mediated and palladium-catalyzed intramolecular Pauson-Khand reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 8744–8788 (2018).

Zhao, Y.-F. et al. Divergent total syntheses of (−)-Crinipellins facilitated by a HAT-initiated Dowd-Beckwith rearrangement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 2495–2500 (2022).

Tormo, J., Moyano, A., Pericàs, M. A. & Riera, A. Enantioselective construction of angular triquinanes through an asymmetric intramolecular Pauson−Khand reaction. Synthesis of (+)-15-Nor-pentalenene. J. Org. Chem. 62, 4851–4856 (1997).

Gharpure, S. J., Niranjana, P. & Porwal, S. K. Stereoselective synthesis of oxa- and aza-angular triquinanes using tandem radical cyclization to vinylogous carbonates and carbamates. Org. Lett. 14, 5476–5479 (2012).

Wang, Y.-P. et al. An efficient approach to angular tricyclic molecular architecture via Nazarov-like cyclization and double ring-expansion cascade. Nat. Commun. 13, 2335 (2022).

Yin, J.-J. et al. Total syntheses of polycyclic diterpenes phomopsene, methyl phomopsenonate, and iso-phomopsene via reorganization of C-C single bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 21170–21175 (2023).

Fang, K. et al. Expansion of structure property in cascade Nazarov cyclization and cycloexpansion reaction to diverse angular tricycles and total synthesis of nominal madreporanone. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202412337 (2024).

Xue, Y. et al. Total synthesis of the hexacyclic sesterterpenoid niduterpenoid B via structural reorganization strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 25445–25450 (2024).

Rinehart, N. I. et al. A machine-learning tool to predict substrate-adaptive conditions for Pd-catalyzed C-N couplings. Science 381, 965–972 (2023).

Shields, B. J. et al. Bayesian reaction optimization as a tool for chemical synthesis. Nature 590, 89–96 (2021).

Xu, L.-C. et al. Enantioselectivity prediction of pallada-electrocatalysed C-H activation using transition state knowledge in machine learning. Nat. Synth. 2, 321–330 (2023).

Ahneman, D. T., Estrada, J. G., Lin, S.-S., Dreher, S. D. & Doyle, A. G. Predicting reaction performance in C-N cross-coupling using machine learning. Science 360, 186–190 (2018).

Li, X., Zhang, S.-Q., Xu, L.-C. & Hong, X. Predicting regioselectivity in radical C-H functionalization of heterocycles through machine learning. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 13253–13259 (2020).

Li, S.-W., Xu, L.-C., Zhang, C., Zhang, S.-Q. & Hong, X. Reaction performance prediction with an extrapolative and interpretable graph model based on chemical knowledge. Nat. Commun. 14, 3569 (2023).

Xu, L.-C. et al. Towards data-driven design of asymmetric hydrogenation of olefins: database and hierarchical learning. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 22804–22811 (2021).

Hu, X., Zhang, G.-T., Bu, F. X. & Lei, A.-W. Visible-light-mediated anti-Markovnikov hydration of olefins. ACS Catal. 7, 1432–1437 (2017).

Li, J., Jin, L.-Q., Liu, C. & Lei, A.-W. Quantitative kinetic investigation on transmetalation of ArZnX in a Pd-catalysed oxidative coupling. Chem. Commun. 49, 9615–9617 (2013).

Hesp, K. D., Tobisch, S. & Stradiotto, M. [Ir(COD)Cl]2 as a catalyst precursor for the intramolecular hydroamination of unactivated alkenes with primary amines and secondary alkyl- or arylamines: a combined catalytic, mechanistic, and computational investigation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 413–426 (2010).

Aerts, H. A. J., Sels, B. F. E. & Jacobs, P. A. The use of 1H NMR for yield determination in the regioselective epoxidation of squalene. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 82, 409–413 (2005).

Do, N. M., Olivier, M. A., Salisbury, J. J. & Wager, C. B. Application of quantitative 19F and 1H NMR for reaction monitoring and in situ yield determinations for an early stage pharmaceutical candidate. Anal. Chem. 83, 8766–8771 (2011).

Huang, X. et al. The ortho-difluoroalkylation of aryliodanes with enol silyl ethers: rearrangement enabled by a fluorine effect. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 9078 (2018).

Hansch, C., Leo, A. & Taft, R. W. A survey of Hammett substituent constants and resonance and field parameters. Chem. Rev. 91, 165–195 (1991).

Gong, S. et al. Calibrating DFT formation enthalpy calculations by multifidelity machine learning. JACS Au. 2, 1964–1977 (2022).

Yu, H.-S. et al. Using machine learning to predict the dissociation energy of organic carbonyls. J. Phys. Chem. A. 124, 3844–3850 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the “National Key R&D Program of China” (2023YFA1506400, 2023YFA1506403); NSFC (92256303); Shanghai Science and Technology Committee (19JC1430100) and Shanghai Jiao Tong University (WH410111001) for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The project was conceived and directed by Y.-Q. Tu. K. Lu designed the experiments and analyzed the data. K. Lu and K. Li performed the experiments. K. Lu finished DFT calculations. K. Lu and J.-Q. Li performed machine learning modeling. P.-P. Zhou offered suggestions on manuscript revision and F.-M. Zhang, X.-M. Zhang, K. Fang, Y.-P. Wang, and Z.-H. Li offered suggestions on experimental improvement.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Peiyuan Yu and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, K., Zhou, PP., Tu, YQ. et al. In-depth insight into structure-reactivity/regioselectivity relationship of Lewis acid catalyzed cascade 4πe-cyclization/dicycloexpansion reaction. Nat Commun 16, 2689 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57859-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57859-7