Abstract

Leveraging the rich stimuli-response of polymers represents a promising direction towards optical communication/encryption. Sign language, which relies on specific geometric change for secured communication, has been widely used for the same purpose since ancient time. We report a strategy that combines both in a validated manner with a hydrogel that not only carries encrypted optical information but also has the hidden behavior to morph geometrically. In particular, the shape morphing behavior is programmable by controlling the oriented state of the polymer chain in the thermo-responsive network. Whether the shape morphing direction is positive (bending) or negative (flattening) cannot be predicted when the polymerization methods are not informed, revealing a hidden manner. Through deciphering the coupling of chain elastic stresses and thermo-induced deswelling stress, the hydrogel can perform designed and diversified 4D morphing which represents evolution of 3D geometries with time as the fourth dimension. Consequently, the corresponding optical information can be gated based on these geometric features, thereby decrypting the correct permutation of information. Our approach that utilizes the geometric 4D morphing for gated verification of optical information offers a strategy for enhancing the security of communication in ways that are quite different from existing strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Amid global concerns about information security, numerous anti-counterfeiting technologies have been reported for information storage and encryption1,2, spanning the application fields of food security3,4, information communication5,6, and display devices7,8. Since ancient times, people have used syrup to write invisible messages that reappear when heated. In this context, diverse fluorescent and stimuli-responsive molecules have been designed and patterned9,10,11,12,13, selectively displaying optical information in an encrypted form, such as patterns, letters, and QR codes under specific conditions14,15,16,17. Notably, to better match different application backgrounds, multi-level anti-counterfeiting technologies combining with multiple decryption stimuli (e.g., temperature, light, pH, and moisture) have been further proposed to improve storage capacity and information security18,19,20. However, most of the reported strategies relied on a single optical channel to encrypt information of various colors or transparency, which are invariably susceptible to decryption by unauthorized individuals21,22. For example, non-assigned inspectors might use different light sources or apply various stimuli to reveal the encrypted information via trial and error, leading to information leakage. Therefore, developing an additional encryption channel which is independent of the traditional optical-based channel holds scientific and practical importance for information security. Moreover, the information capacity can be greatly enhanced via introducing an additional encryption channel. The cracking times required for the trial and error must increase exponentially, which remarkably elevates the security level.

Sign language, a widely used communication method offers an inspiration for elevating both the capability and security level. It commonly conveys information through dynamic transformation of geometries posed by hands and fingers without relying on patterns or text. This method, often unintelligible to non-professionals, provides a promising alternative to traditional optical encryption systems23,24,25. Inspired by this, the past decade has witnessed a number of shape-changing materials for anti-counterfeiting systems, including shape memory polymers26,27, liquid crystal elastomers28,29, and responsive hydrogels30,31. However, these systems can only be decrypted into a single pre-designed geometry upon stimulus, since the shape morphing cannot be altered unless a distinct sample is prepared (Fig. 1a). Such information storage capacity is far inferior to that of gestures which allow multiple geometric displays with a single hand (Fig. 1b). Consequently, existing geometric-related encryption systems have been limited to shielding or revealing optical information32,33,34. Their low information capacity and predictable shape morphing prevent it from serving as an independent encryption channel. With this in mind, we propose a 4D multi-shape-morphing system in which a responsive hydrogel can be mechanically programmed into unanticipated shapes and afterward reveal the hidden 3D geometric information upon decryption by an external stimulus (Fig. 1c). It is worth noting that the original information carriers must maintain a consistent appearance. And only when the correct programming operation were executed the decrypted geometries containing the intended information can be revealed. Upon satisfaction of these requirements, the morphing geometries can be regarded as a viable independent encryption channel. This represents a significant challenge for current anti-counterfeiting technologies, particularly in the field of programmable shape-morphing materials.

a Illustration showing that conventional hydrogels can only provide a single shape-morphing mode after preparation. b Illustration showing the communication mechanism of sign language that one hand can convey multiple gesture information. c Programmable hydrogel with multiple shape-morphing modes enabling multiple geometric information. d Shape-morphing profiles showing positive morphing upon deswelling stress and negative morphing upon elastic recovery stress. e Geometric information with hidden morphing direction based on the coupling of the deswelling stress and the elastic recovery stress.

We recognize from our latest discoveries that hydrogels with programmable chain orientation offer the possibility for carrying this multiple geometric information35,36. Traditionally, various morphing actions of hydrogels can be controlled according to the heterogeneity in volume changing (e.g., deswelling gradient for bending, Fig. 1d left)37,38,39,40,41. In contrast, the chain orientation generates elastic recovery stress upon stimulus when maintaining the overall volume of the material (Fig. 1d right). In this work, the two opposite shape-morphing driving forces (e.g., the deswelling stress and the elastic recovery stress) were integrated into a single material. In addition to multiple geometries evolved, the morphing direction can also be adjusted to either positive or negative by controlling the competition of the two forces (Fig. 1e), which further enhances the security level. Consequently, optical information can be planarly patterned onto the hydrogel surface through a process known as ion printing, in which lanthanide metal ions were soaked in cropped filter paper and then coordinated with the pendant terpyridine moieties in the hydrogel matrix to create distinct patterns (Supplementary Fig. S1). These patterns can then be authenticated by the geometric information after encryption from the synthesis and programming approaches.

Results

To achieve this extraordinary shape-morphing event, we synthesized a thermo-responsive P(NIPAm-co-Tpy) hydrogel via thermo-initiated copolymerization of N-isopropyl acrylamide (NIPAm) as the thermo-responsive monomer, terpyridine-containing acrylate (Tpy-A) as the dynamic crosslinker, and N, N’-methylenebisacrylamide (BIS) as the permanent crosslinker (Fig. 2a). In this system, the introduction of hydrophobic Tpy-A would generate hydrophobic clusters which decrease the water content of P(NIPAm-co-Tpy) hydrogel42 (Supplementary Fig. S2). The mechanical properties of the hydrogels (strain at break and modulus) enhance with the content of Tpy-A which can form energy dissipation domains as physical crosslinking points (Supplementary Fig. S3)43,44. This hydrophobic cluster can be dissociated after adding Fe3+ (Supplementary Fig. S4), and the consequent influence on the shape-morphing properties of the P(NIPAm-co-Tpy) hydrogel will be studied subsequently. Moreover, after further optimization of the BIS content (Supplementary Fig. S5), hydrogels with 5 wt% Tpy-A and 1 wt% BIS were applied for subsequent studies unless otherwise noted.

a Monomer precursors. b Illustration showing the mechanism of deswelling stress-induced positive morphing. c Shape-morphing kinetics of thermo-initiated and photo-initiated P(NIPAm-co-Tpy) hydrogels. d Images showing the shape-morphing process. e Illustration showing the mechanism of coupling-stress-induced negative morphing. f Impact of BIS content on bending direction and angle. Scale bars:0.5 cm. Data are presented as mean values +/− SD (n ≥ 3).

Through ion printing, the deswelling stress and shape-morphing of the P(NIPAm-co-Tpy) hydrogel were subsequently regulated via the created gradient of the Fe3+ content. As shown in Fig. 2b, when a wet filter paper absorbing 0.1 M Fe3+ was covered onto one surficial side of the hydrogel, Fe3+ diffused along the thickness direction and coordinated with the pendant Tpy-A groups, accompanied with a color change from colorless to purple. This diffusion process and the corresponding gradient structure were monitored via optical microscopy and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Supplementary Fig. S6). The EDX analysis of the Fe element along the cross-sectional direction further confirmed the gradient structure (Supplementary Fig. S7). Due to the disassociation of the Tpy-A hydrophobic clusters after the Fe3+ coordination, the thermo-responsive shrinkage ratio of the hydrogels increases accordingly (Supplementary Fig. S8). Since the coordination attenuates along with the diffusion process, the shrinkage ratio decreases from the filter paper side to the other. As a result, the deswelling stress upon uniform heating gradually increases, leading to the bending of the hydrogel (positive morphing) (Supplementary Fig. S9). When the ion diffusion time is too short or overly extended, the responsive bending angles are small due to the insufficient gradient structure (Supplementary Fig. S10). Consequently, an optimized diffusion time of 5 min was applied for the following investigation.

Furthermore, when the elastic recovery stress was incorporated into the system via Fe3+ coordination of a bent hydrogel sample (Supplementary Fig. S11), unexpected shape-morphing could be achieved. Based on the stress distribution of a bent hydrogel, the internal region was compressed with an expansive tendency (opposite to the deswelling stress), while the external region was stretched with a contraction tendency (aligned with the deswelling stress). Along this line, we discovered that the thermo-initiated P(NIPAm-co-Tpy) hydrogel (labeled as TIH) and the photo-initiated hydrogel (labeled as PIH) exhibited two opposite shape-morphing directions when their feed compositions and programming methods were both identical. The TIH bended from 150° to 10° (positive morphing) in 30 s, whereas the PIH bended from 60° to 170° (negative morphing) in 16 seconds (Fig. 2c and d). The shape-morphing process was fully reversible at 20 °C and could be repeated without obvious difference over 10 cycles (Supplementary Fig. S12). However, the programmed hydrogels cannot recover to their original flat shape prior to programming since the Tpy-Fe3+ coordination is too strong to be completely decoupled.

The shape-morphing events observed in both TIH and PIH can be controlled via tuning the synthesis parameters. When the chemical composition and polymerization conditions were altered, the predomination between the two stresses would be switched accordingly, thus the shape-morphing direction can be changed (Fig. 2e). For instance, TIH exhibited negative morphing only when the content of the fed BIS content was very low (0.25 wt%), and PIH, in contrast, exhibited positive morphing when the content was relatively high (> 1 wt%) (Fig. 2f). Notably, although the threshold BIS concentration differed between the TIH and PIH, the corresponding threshold modulus is similar (~ 30 kPa, Supplementary Figs. S5, S13 and S14). This is probably because the low modulus of the original hydrogel promotes shape retention after the coordination (Supplementary Fig. S15). On the other hand, shape retention represents the degree of the chain orientation within the network, which can further correspond to the elastic recovery stress. Higher shape retention implies larger elastic recovery stress, which tends to cause negative morphing. As a result, negative morphing is more likely to occur when the shape retention is higher than 30% with the modulus lower than 30 kPa. A similar trend was found with respect to polymerization time. As the polymerization time increased, the shape morphing of the TIH shifted from negative to positive due to the strengthen of the network (Supplementary Fig. S16). In contrast, extending the polymerization time had little effect on the shape-morphing direction of PIH owing to its incomplete and looser network. Besides the opposite shape-morphing direction, it should be noted that the TIH and the PIH exhibited indistinguishable appearance (Supplementary Fig. S17), gradient structure (Supplementary Figs. S18, S19, and S20), and shape-morphing kinetics (Supplementary Figs. S21 and S22). Therefore, the shape-morphing information could be unpredictable and is thus hidden from the naked eye. In contrast, previous shape-changing polymers can only execute predictable morphing along one direction when they were synthesized from the same precursor thus cannot hide the morphing direction.

The extraordinary shape-morphing event motivates us to further investigate the underlying mechanism. For the two driving forces contributing to the shape-morphing upon heating, the deswelling stress is attributed to the volume phase transition of PNIPAm and the recovery stress is originated from the stretched polymer chains. Based on the mechanical and responsive deswelling properties (Supplementary Fig. S23) of the hydrogels, a shape-morphing model was constructed via finite element simulation (Fig. 3a). The deswelling stress predominated for the TIH to promote bending (positive morphing), and the elastic recovery predominated for the PIH to result in flattening (negative morphing). Conversely, negative morphing occurs when the recovery stress dominates, as can be observed in PIH. The distribution and coupling of the two stresses further reveal that the corresponding gradient in TIH is significantly higher than that in PIH. In this case, the deswelling stress would predominate in TIH to enable positive morphing (Fig. 3b). It should be further noted that the shape-morphing direction is not immutable for hydrogels synthesized via the same initiation system. The structural parameters and the programming bending strain can all be tuned to alter the predominance of the two stresses, thus change the morphing direction of TIH and PIH. For example, PIH exhibits negative morphing at low thicknesses (0.5 mm) but positive morphing at greater thicknesses (> 1 mm) (Supplementary Fig. S24). The aspect ratio did not affect the shape-morphing direction for neither TIH nor PIH, as it scarcely impacted on the coupled stress distribution (Supplementary Fig. S25).

a The shape-morphing process and mechanism of the programmed P(NIPAm-co-Tpy) hydrogels. b Simulated stress distribution in the thickness direction of TIH and PIH, respectively. c Illustration and images showing the complex shape-morphing process with anisotropic deswelling stress. d Illustration and images showing the shape-morphing with isotropic deswelling stress. Scale bars: 1 cm.

In addition, after fabrication, the shape-morphing direction can also shift from negative to positive as the programming diameter increases from 2 mm to 10 mm (Supplementary Fig. S26). These results suggest that enhancing the elastic recovery stress while maintaining the deswelling stress leads to a tendency of negative morphing, thus opposite shape-morphing directions could be manipulated. Subsequently, more complex shape-morphing behaviors can be achieved from a single initial shape through stress coupling enabled by various programming methods. Samples with both anisotropic and isotropic deswelling stress were investigated. When the TIH was spirally wrapped and fixed with Fe3+, each spiral ring can be simplified as bending despite the overall three-dimensional shape. Based on stress analysis, the resulting spiral shape can reduce the diameter and form more pitches upon heating (Supplementary Fig. S27a), in accordance with the positive morphing in the bending mode. In contrast, the PIH after the same spiral-type programming became flattened upon heating(Fig. 3c). For twist-type programming, which did not create the difference in Fe3+ concentration from the two surficial sides, it can be considered that the samples underwent isotropic deswelling stress. In this case, the internal torque from the elastic recovery stress can be decomposed into two components, namely, untwisting stress along the axis and bending stress perpendicular to the axis (Supplementary Fig. S27b). Due to the difference in shape retention ratio between TIH and PIH (Supplementary Fig. S15), PIH retained a more significantly twisted structure which stored higher elastic recovery stress. As a result, TIH underwent flattening, while PIH eventually adopted a helical shape upon heating (Fig. 3d). The overall results indicate that the encrypted shape-morphing information could be hidden in the same appearance and could not be predicted unless the correct synthesis approaches or programming pathways were provided.

The coordination between pendant Tpy-A moieties and metal ions can not only regulate shape morphing but also exhibit multi-color visualization enabled by fluorescent emission19,45. The Tpy-A moieties can serve as both an energy acceptor and a sensitizer, significantly increasing the emission intensity of Eu3+ or Tb3+ ions through resonance energy transfer (RET) under an appropriate light source (Supplementary Fig. S28)42,46. Thus, when a PIH, which was transparent under natural light and non-fluorescent under UV light, was treated with 0.1 M solutions of lanthanide ions (Eu3+ or Tb3+), corresponding red or green fluorescent emission was generated under 254 nm due to the complexation with Tpy-A (Fig. 4a and b). It is worth noting that the fluorescent behavior of TIH was similar (Supplementary Fig. S29), and the fluorescent intensity for both PIH and TIH can be regulated by the ion concentration (Supplementary Figs. S30 and S31). In addition, more multi-color fluorescent hydrogels can be further obtained by treatment with mixed solutions of Eu³⁺ and Tb³⁺, and these fluorescent emissions can be quenched by Fe3+. The luminescence emission originating from the LnIII is relatively stable, with no obvious change in fluorescent intensity when stored in a sealed bag without additional water (Supplementary Fig. S32).

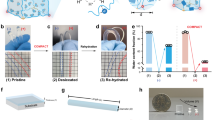

a Images showing the multi-color fluorescent behavior of PIH. The emission color can be easily adjusted to red, green, or yellow upon coordination with Eu3+, Tb3+, or their mixtures. All fluorescent emissions can be quenched by Fe3+. b Fluorescence spectra (λex = 254 nm) of PIH treated with Eu3+, Tb3+, their mixtures and Fe3+. c Illustrations showing the multi-color pattern. d Images showing the patterning process on the surface of PIH by ionoprinting. e Illustrations showing the operation of dual-encryption by integrating pattern fluorescence and thermo-responsive shape-morphing of PIH. Number-shaped filters containing Eu3+ and trapezoid-shaped filters containing Fe3+ were ionoprinted onto the upper and lower surfaces of PIH, respectively. The hydrogel was then immersed in 50 °C water to trigger thermo-responsive shape-morphing, thereby shielding the fluorescent pattern. f Images showing the information encryption process. Scale bars: 0.5 cm.

Moreover, a series of filter papers containing different metal ions were sequentially applied to the surface of a PIH (Fig. 4c). After the removal of these papers, the corresponding multi-color fluorescent mushroom pattern was obtained (Fig. 4d). Notably, the lanthanides-coordinated areas which were visible under 254 nm UV light could not be observed, while the Fe3+-coordinated area was visible under natural light but almost invisible under UV light. Such behavior is desirable for anti-counterfeit. For further demonstration, the number information from “1” to “6” that was only visible under 254 nm UV light, were encoded with Eu3+ on the top surface of a six-petal PIH (Fig. 4e). Subsequently, Fe3+ were printed onto the bottom surface of non-programmed TIH to introduce the response gradient. Upon heating, the six petals of the complexed hydrogel bend, thereby shielding the encrypted information under 254 nm UV light (Fig. 4f). Similar encryption process can also be enabled by TIH (Supplementary Fig. S33). This demonstration provides a synergistic encryption of fluorescent information and 3D morphology. Incorporating further programming operations, we subsequently showcase that the hydrogels with hidden geometric information can act as an additional encryption channel.

To act as an additional channel, the material should be capable of adopting various distinct geometric features (e.g., flat or spiral) to authenticate the leaked pattern information (Fig. 5a). As shown in Fig. 5b when the letter information (“♥HEART”) was encoded onto the surface of a TIH and a PIH, the encrypted information could be intentionally decrypted or inadvertently leaked under 254 nm UV light. The hydrogels were then programmed into similar twisted shapes upon treatment with Fe3+. Upon heating, the two hydrogels respectively transformed into a flat shape and a spiral shape, which can be used to authenticate the validity by comparing with the pre-set correctness of the geometric information.

a Illustrations showing the dual-channel encryption process. The letter “E” is first ionoprinted onto the surface of a P(NIPAm-co-Tpy) hydrogel strip. The strip is then twisted by external force and immersed in 0.1 M Fe3+ for 5 min to fix the temporary shape. The hydrogel will morph into either a flat shape, indicating verification failure, or a spiral shape, indicating verification success. b Images showing the dual-channel encryption of TIH and PIH. c The 3D dual-channel encryption of P(NIPAm-co-Tpy) hydrogel strip. The word “RETURN” is encoded into the corresponding thermo-initiated and photo-initiated areas of the hydrogel strip. Through different programming pathways for verification (① non-program, ② spiral program, and ③ twist program), the hydrogel strip generates various 3D geometries and displays the decrypted information upon heating. Scale bars: 1 cm.

Moreover, the encryption level could be further elevated by combining thermo- and photo-initiated polymerization. As shown in Fig. 5c, a composite hydrogel with thermo-initiated areas (II, III, and V) and photo-initiated areas (I, IV, and VI) was first prepared. The characters “RETURN” were sequentially encoded via ion printing. The encryption consists of two orthogonal channels corresponding to the character and shape-morphing information, respectively. Accordingly, full decryption involves two steps: UV decryption and heating decryption. Even if the encrypted fluorescent information was leaked, further decryption of the geometric information is still required to obtain the true information. In addition, verification pathways can be enabled via various programming approaches for authentication. The hydrogel can either remain non-programmed (pathway 1) or be programmed into a spiral shape (pathway 2) or a twisted shape (pathway 3). Among these, only one can be predetermined as the correct pathway (for instance, pathway 3). Subsequently, the three types of hydrogels were immersed in Fe3+ and triggered to undergo shape morphing in 50 °C water. In pathway 1, the corresponding shape transformation of the hydrogel was undecipherable. In pathway 2, the hydrogel exhibited a complex 3D morphology. According to the encoding principle, the spiral area represented effective information, while the flat area represented useless information. Although the characters “ETR” were decrypted, they were incorrect according to the hidden predetermination. Only through correct verification (pathway 3) could the hydrogel exhibit the correct 3D geometry after shape morphing, thereby decrypting the true information “RUN”. Regardless of the verification pathway chosen, the hydrogels required Fe3+ treatment, which quenched fluorescent emission and erased the information. The stable metal coordination prevents Fe3+ from being removed, meaning the hydrogel cannot be reprogrammed. In this case, there is only one chance to authenticate the decrypted information, eliminating trial and error and enhancing security. For existing encryption systems combining optical and shape-morphing units in comparison, geometric changes only serve to reveal or shield optical information. This feature allows for multiple decryption attempts, introducing the potential for trial and error.

We further use shape-morphing as an independent information channel to create a sophisticated encryption system. The hidden geometric feature is encoded with basic logical code (e.g., spiral morphology represents “1” and flat morphology represents “0”) (Fig. 6a). After programming, thermo-initiated areas self-transform into a spiral shape, while photo-initiated areas become flat. By analyzing this geometric sequence (flat-spiral-flat-spiral-flat-flat), designated inspectors can decode the sequence (0-1-0-1-0-0) to reveal the encrypted letter “T” according to ASCII code (Fig. 6b). Additional geometric sequences can be generated using the same process (Supplementary Fig. S34), enabling the encoded hydrogel strips to independently export all letter information in theory. The encryption system is composed of three parts, including a Fe3+-written QR code (web of our group), a Tb3+-written barcode (Zhejiang University, abbreviated as ZJU), and Eu3+-written letter information (Cutting for verification) (Fig. 6c). Due to the optical properties of Tpy-complexation, the QR code was scannable under natural light, while the barcode and letter information were visible under 254 nm UV light. Although the full pattern information could be obtained by alternating visible and UV illumination, the hidden shape-morphing information remained encrypted to the naked eye. For further decryption, a strip should be cut from area III and programmed through twisting. The geometric sequence (flat-spiral-flat-spiral-flat-flat) was then exhibited in 50 °C water, revealing the letter “T” and authenticating the obtained pattern information. In case of any other letters revealed, the pattern information should be recognized as a false one. Notably, this verification code could only be known for the receiver from another secret passage. Therefore, this dual-channel encryption strategy provides a higher security level in comparison with existing pattern-dependent encryption methods. Still, there are indeed some practical limitations. The controlling precision of the complex shape-morphing was limited by the operation consistency of the ion printing process. Wet filter papers contained ions have to precisely and consistently cover the design area to generate complex morphing patterns. This procedure is hard to handle, especially on nonplanar 3D surface. Moreover, the resolution of this approach is not very high due to the unavoidable diffusion. Therefore, the feature size of the patterning method in this work is limited to the order of a few millimeters.

a ASCII code representation. Upon shape changing, the flat location indicates “0” while the spiral location indicates “1”. b Geometry information display. In the hydrogel strip, the thermo-initiated area reveals “0” and the photo-initiated area reveals “1”. c Illustrations and images of 4D information encryption and verification. The 2D QR code (visible under natural light) and the 1D barcode (visible under 254 nm light) are encoded onto the hydrogel sheet. The nether barcode is cut, and the verification can be then performed. Scale bars: 1 cm.

Discussion

In summary, we propose a dual-channel encryption system with a combination of an optical encryption channel and a geometry encryption channel. In a hydrogel providing coordination between Tpy-A moieties and Fe3+, deswelling stress induced by thermal shrinkage was integrated with elastic recovery stress originating from programmed chain orientation. Upon the same programming approach, two apparently similar hydrogels synthesized via respectively thermal and photopolymerization would generate distinct shape-morphing directions (e.g., bending and flattening) due to the alternative predominance of the two stresses. This pre-coded shape-morphing information remained encrypted until the disclosure of the hidden synthesis approaches, the structural parameters, and the programming processes. Compared to existing encryption strategies, the presented hydrogel system provided another independent encryption channel to either reveal the encrypted pattern information or authenticate the leaked ones, enhancing both information capacity and security level. This geometric morphing channel has not been realized by other anti-counterfeiting technologies due to the predictable shape-morphing events of existing programmable polymers, which is believed to inspire the design of more anti-counterfeiting technologies with multi-channel and higher security features.

Methods

Materials

N-isopropyl acrylamide (NIPAM, > 98%), 2,2,-dimethoxy-2-phenylacetophenone (DMPA, > 98%) were purchased from TCI (Shanghai) Development Co., Ltd. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, > 99%), 1,3-propanediol (> 99%), 4’-chloro-3,5-bis(pyridyl)-1,2,4-triazole (> 99%), ammonium persulfate (APS, > 98%), acryloyl chloride (> 99%), triethylamine were purchased from Aladdin reagent Co. Ltd. Dichloromethane (DCM), potassium hydroxide (KOH) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. N,N’-Methylenebisacrylamide (BIS, > 99%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

All the chemicals were used as received.

Synthesis of terpyridine-containing acrylate (Tpy-A)

Under a nitrogen atmosphere, 1,3-propanediol (56.0 mmol, 4.26 g) was added to 50 mL of a round-bottom flask containing 25 mL of dry DMSO. While stirring the solution, KOH (56.0 mmol, 3.14 g) was added, and the mixture was heated to 60 °C for 10 min. 4’-chloro-3,5-bis(pyridyl)-1,2,4-triazole (11.2 mmol, 3.00 g) was added, and the temperature maintains at 60 °C for two days. The reaction mixture was poured into 20 mL of ice water, and the pH was adjusted to 6. By filtration and recrystallized with 10 mL of methanol at 70 °C, the white precipitate 4’-hydroxypropoxy-3,5-bis(pyridyl)-1,2,4-triazole was obtained with an 85% yield.

Add 4’-hydroxypropoxy-3,5-bis(pyridyl)-1,2,4-triazole (1.0 g, 3.25 mmol) to 50 mL of ice-cooled CH2Cl2, and mix 320 mg (3.57 mmol, 0.288 mL) of acryloyl chloride and 493.3 mg (4.88 mmol, 0.5 mL) of triethylamine to solution by using a syringe. After 30 min, warmed the solution to room temperature and stirred overnight. The reaction mixture was extracted with K2CO3 aqueous solution (3 × 15 mL) to remove the inorganic salts. Remove the solvent under vacuum at room temperature, and recrystallize the product twice from methanol (10 mL) at 70 °C to obtain 800 mg (66%) of white crystals.

Fabrication of P(NIPAm-co-Tpy) hydrogel

For the thermo-initiated P(NIPAm-co-Tpy) hydrogel (TIH), 1 g NIPAM, 10 mg BIS, 50 mg Tpy-A, 10 mg APS, and 1 g DMSO were mixed and added into a homemade mold comprising a 0.5 mm silicone rubber spacer and two pieces of glass. The precursor was polymerized at 70 °C for 8 h, followed by solvent exchange with water at 20 °C for 24 h to obtain the TIH. The photo-initiated P(NIPAm-co-Tpy) hydrogel (PIH) was fabricated from the same feed composition, except that APS was replaced by 10 mg photo-initiator DMPA. The polymerization was conducted under UV light for 5 min, followed by water exchange.

Programming of the chain orientation within hydrogels

The hydrogel was deformed into various temporary shapes (such as bending and helix) by applying external force. Subsequently, a wet filter paper soaking 0.1 M Fe3+ was covered on the surface of the hydrogel for the ion printing. The resulting metal coordination can fix the deformed shape, retaining the chain orientation. The optimal time of the coordination treatment was determined to be 5 minutes.

Patterning optical information via ion printing

Filter papers were cropped into designed shapes (letters, patters or numbers), and were then immersed in 0.1 M solution of lanthanide metal ions (Eu3+ or Tb3+). After wipe of excessive surface water, the hydrogels were covered with the wet filter papers for the ion printing. After a certain time (5 min for the optimized cases), the filter papers were peeled off, leaving behind luminescence patterns on the hydrogels, reproducing the shapes of the papers.

Measurements of water content

Water content was calculated using the following equation:

where \({m}_{s}\) and \({m}_{d}\) represent the weight of fully swollen hydrogels and dried hydrogels, respectively.

Measurements of thermo-responsive shrinkage ratios

Thermo-responsive shrinkage ratios was calculated using the following equation:

where \({m}_{h}\) represents the weight of hydrogels which were immersed in 50 °C water for 5 min, and \({m}_{c}\) represents the weight of hydrogels in 20 °C water.

Mechanical properties tests

The mechanical properties were measured by universal material testing machine (Zick/Roell Z005) at the strain rate of 5 mm/min, all samples were cut into dumbbell types with the neck dimensions of 20 mm × 2 mm × 0.5 mm.

Simulation

All simulations were carried out using Abaqus 2020. The Abaqus/Explicit solver was employed. The models of the hydrogels were constructed using an 8-node linear brick, reduced integration, and hourglass control mesh element type (C3D8R). The mechanical properties of the hydrogels were captured using a linear elastic model with the uniaxial tension test data, and the contraction behavior of the hydrogel was captured using isotropic contraction from the shrinking test data.

The programming process of the hydrogels was captured by loading and unloading moments to the layers. The difference concerning the temperature response along the thickness direction of the hydrogels was captured by setting the temperature field with an analytical field according to the structural parameters from experiment data.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are provided within the article and its Supplementary Information file. All data are available upon request. Source data are provided in this paper.

References

Shen, Y., Le, X. X., Wu, Y. & Chen, T. Stimulus-responsive polymer materials toward multi-mode and multi-level information anti-counterfeiting: recent advances and future challenges. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 606–623 (2024).

Zhang, H. W., Li, Q. Y., Yang, Y. B., Ji, X. F. & Sessler, J. L. Unlocking chemically encrypted information using three types of external stimuli. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 18635–18642 (2021).

Mazur, F., Han, Z., Tjandra, A. D. & Chandrawati, R. Digitalization of colorimetric sensor technologies for food safety. Adv. Mater. 36, 202404274 (2024).

Lou, D. Y. et al. Double lock label based on thermosensitive polymer hydrogels for information camouflage and multilevel encryption. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, 202117066 (2022).

Deng, S. H. et al. Bioinspired dual-mode temporal communication via digitally programmable phase-change materials. Adv. Mater. 33, 2008119 (2021).

Chen, X. C., Huang, W. P., Ren, K. F. & Ji, J. Self-healing label materials based on photo-cross-linkable polymeric films with dynamic surface structures. ACS Nano 12, 8686–8696 (2018).

Yang, B. et al. Asymmetrically enhanced coplanar-electrode electroluminescence for information encryption and ultrahighly stretchable displays. Adv. Mater. 34, 202201342 (2022).

Fan, W. et al. Iridescence-controlled and flexibly tunable retroreflective structural color film for smart displays. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw8755 (2019).

Yang, H. L. et al. Erasable, rewritable, and reprogrammable dual information encryption based on photoluminescent supramolecular host-guest recognition and hydrogel shape memory. Adv. Mater. 35, 2301300 (2023).

Wang, Q. et al. A dynamic assembly-induced emissive system for advanced information encryption with time-dependent security. Nat. Commun. 13, 4185 (2022).

Sun, L. Y. et al. Bioinspired programmable wettability arrays for droplets manipulation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 4527–4532 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Non-monotonic information and shape evolution of polymers enabled by spatially programmed crystallization and melting. Chem. Bio. Eng. 1, 790–797 (2024).

Chen, D. et al. Orthogonal photochemistry toward direct encryption of a 3D-printed hydrogel. Adv. Mater. 35, 2209956 (2023).

Sun, Y., Le, X. X., Zhou, S. Y. & Chen, T. Recent progress in smart polymeric gel-based information storage for anti-counterfeiting. Adv. Mater. 34, 2201262 (2022).

Lu, L. et al. Multiple photofluorochromic luminogens via catalyst-free alkene oxidative cleavage photoreaction for dynamic 4D codes encryption. Nat. Commun. 15, 4647 (2024).

Xie, H. L. et al. Mechanochemical fabrication of full-color luminescent materials from aggregation-induced emission prefluorophores for information storage and encryption. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 18350–18359 (2024).

Li, X. K. et al. Multi-modal melt-processing of birefringent cellulosic materials for eco-friendly anti-counterfeiting. Adv. Mater. 36, 2407170 (2024).

Le, X. X. et al. A urease-containing fluorescent hydrogel for transient information storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 3640–3646 (2021).

Sun, Y. et al. Dual-mode hydrogels with structural and fluorescent colors toward multistage secure information encryption. Adv. Mater. 36, 2401589 (2024).

Li, L. Q. et al. Finely manipulating room temperature phosphorescence by dynamic lanthanide coordination toward multi-level information security. Nat. Commun. 15, 3846 (2024).

Ju, H. Q. et al. Polymerization-induced crystallization of dopant molecules: An efficient strategy for room-temperature phosphorescence of hydrogels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 3763–3773 (2023).

Yang, Y. B. et al. Codes in code: AIE supramolecular adhesive hydrogels store huge amounts of information. Adv. Mater. 33, 2105418 (2021).

Lu, H. H. et al. Programming shape memory hydrogel to a pre-encoded static deformation toward hierarchical morphological information encryption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2206912 (2022).

Le, X. X. et al. Ionoprinting controlled information storage of fluorescent hydrogel for hierarchical and multi-dimensional decryption. Sci. China Mater. 62, 831–839 (2018).

Su, G. et al. From fluorescence-transfer-lightening-printing-assisted conductive adhesive nanocomposite hydrogels toward wearable interactive optical information-electronic strain sensors. Adv. Mater. 36, 202400085 (2024).

Yuan, W. H. et al. Self-evolving materials based on metastable-to-stable crystal transition of a polymorphic polyolefin. Mater. Horiz. 9, 756–763 (2022).

Huang, J. H., Jiang, Y., Chen, Q. Y., Xie, H. & Zhou, S. B. Bioinspired thermadapt shape-memory polymer with light-induced reversible fluorescence for rewritable 2D/3D-encoding information carriers. Nat. Commun. 14, 7131 (2023).

Choi, S. H. et al. Phase patterning of liquid crystal elastomers by laser-induced dynamic crosslinking. Nat. Mater. 23, 834–843 (2024).

Wang, H. Q. et al. A dual-responsive liquid crystal elastomer for multi-level encryption and transient information display. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202313728 (2023).

Zhang, M. C. et al. Hydrogel muscles powering reconfigurable micro-metastructures with wide-spectrum programmability. Nat. Mater. 22, 1243–1252 (2023).

Miao, S. S., Wang, Y., Sun, L. Y. & Zhao, Y. J. Freeze-derived heterogeneous structural color films. Nat. Commun. 13, 4044 (2022).

Zhang, Y. C. et al. 3D fluorescent hydrogel origami for multistage data security protection. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1905514 (2019).

Zhu, C. N. et al. Dual-encryption in a shape-memory hydrogel with tunable fluorescence and reconfigurable architecture. Adv. Mater. 33, 2102023 (2021).

Wang, R. J. et al. Bio-inspired structure-editing fluorescent hydrogel actuators for environment-interactive information encryption. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, 202300417 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Differential diffusion driven far-from-equilibrium shape-shifting of hydrogels. Nat. Commun. 12, 6155 (2021).

Ni, C. J. et al. High speed underwater hydrogel robots with programmable motions powered by light. Nat. Commun. 14, 7672 (2023).

Wu, B. Y. et al. Recent progress in the shape deformation of polymeric hydrogels from memory to actuation. Chem. Sci. 12, 6472–6487 (2021).

Fan, W. X. et al. Dual-gradient enabled ultrafast biomimetic snapping of hydrogel materials. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav7174 (2019).

Zhu, Q. L. et al. Animating hydrogel knotbots with topology-invoked self-regulation. Nat. Commun. 15, 300 (2024).

Zhu, C. N. et al. Reconstructable gradient structures and reprogrammable 3D deformations of hydrogels with coumarin units as the photolabile crosslinks. Adv. Mater. 33, 2008057 (2021).

Zhang, Y. C., Liao, J. X., Wang, T., Sun, W. X. & Tong, Z. Polyampholyte hydrogels with pH modulated shape memory and spontaneous actuation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1707245 (2018).

Yin, G. Q. et al. Precisely coordination-modulated ultralong organic phosphorescence enables biomimetic fluorescence-afterglow dual-modal information encryption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2310043 (2023).

Hou, W. S., Yu, X. D., Li, Y. J., Wei, Y. & Ren, J. J. Ultrafast self-healing, highly stretchable, adhesive, and transparent hydrogel by polymer cluster enhanced double networks for both strain sensors and environmental remediation application. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 57387–57398 (2022).

Chen, C., Pang, X. L., Li, Y. J. & Yu, X. D. Ultrafast self-healing, superstretchable, and ultra-strong polymer cluster‐based adhesive based on aromatic acid cross-linkers for excellent hydrogel strain sensors. Small 20, 2305875 (2023).

Chen, C., Pang, X. L., Li, Y. J. & Yu, X. D. Dual lewis acid- and base-responsive terpyridine-based hydrogel: Programmable and spatiotemporal regulation of fluorescence for chemical-based information security. Inorg. Chem. 62, 2105–2115 (2023).

Wu, B. Y. et al. Cephalopod-inspired chemical-gated hydrogel actuation systems for information 3D-encoding display. Adv. Mater. 36, 2401659 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFB3805701 to Q.Z.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (52273112 and U20A6001 to Q.Z.), Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (GZB20240649 to B.W.), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2024ZFJH01-01 to T.X.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.Z., B.W., and X.W. conceived the concept. X.W., B.W., and G.C. conducted the experiments. K.Z. and X.Y. conducted the simulation. Q.Z., B.W., K.Z., and X.Y. analyzed the mechanism with the assistance of N.Z. and J.W. for visualization. X.W., B.W., Q.Z., and T.X. wrote the manuscript. All authors participated in the discussion of results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Shazed Aziz, who co-reviewed with Bidita Salahuddin, Xudong Yu, and Xiaoling Zuo for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wen, X., Zhang, K., Wu, B. et al. Multi-mode geometrically gated encryption with 4D morphing hydrogel. Nat Commun 16, 2830 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58041-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58041-9

This article is cited by

-

Shape-morphing active particles with invertible effective polarizability for configurable locomotion and steering

Nature Communications (2026)