Abstract

Selective control of single untethered robots within a collection is trivial in macroscale robotics since it is possible to address and actuate individual entities using various communication schemes. This strategy does not work at reduced (sub-µm) length scales, where the global field cannot differentiate or control a single nanobot selectively from within a collection of indistinguishable objects. Here, we propose and demonstrate strategies where identical magnetic nanobots can be selectively and independently actuated using global control fields.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Untethered nanobots have been envisioned to perform tasks that are not possible with existing technologies, for example, microsurgery deep inside the organ of a living animal1, assembling components on an electronic chip2, repairing damaged DNA within the nucleus of a cancerous cell3, and many more4. By imparting multiple functionalities within a single nanobot, one can achieve simultaneous sensory and actuation capabilities down to very small scales, which can lead to a paradigm shift in many current technologies5. An important thrust of modern research in nanorobotics is to devise ways to maneuver nanobots with a high degree of precision and control6, both at the level of individual bots as well as the complete collection. This requires solving many non-trivial problems, for example, overcoming the dominant effect of friction at small scales7 while ensuring controllability in the presence of strong thermal fluctuations. Accordingly, challenges to achieve controlled manipulation of nanobots in fluids are often different from their macroscale counterparts8. A variety of approaches using external control mechanisms such as electrical9, optical10, magnetic11, and acoustic forces12 have been reported, where controlled manipulation of both individual and swarms of nanobots have been demonstrated.

The question addressed in this paper pertains to individual control of nanobots, specifically how to position them and/or control their trajectories in an independent and selective manner13. Adding this capability can allow a system of nanobots to achieve functionalities with a higher degree of complexity14, e.g., where the task elements are spatially distributed15, and therefore requiring precise placement or movement of the nanobots. Independent positioning and manipulation of bots can aid in better parallelization, thereby leading to higher throughput. This feature is significantly simpler to implement in macroscale robotics, where it is possible to communicate with an individual robot and actuate it selectively. Typically, the communication protocol is based on radio frequency signals with onboard electronics, which unfortunately also implies that the smallest bot size will be limited by the footprint of the chip and the associated cost of integration16.

The commonly used strategy to address smaller robots selectively is by applying external drive with spatial variation17, which allows motility to be induced selectively to certain robots based on their location. This can be achieved through selective pattering of a highly customized underlying substrate, where electrostatic or magnetic forces can be used to address the robots individually18. Alternately, for magnetic microbots, one can achieve selective control by using a combination19 of gradient and time-varying homogenous fields. Neither of these approaches scales easily to smaller sizes, considering practical issues in reducing the dimensions of the nanopatterning features or generating magnetic field gradients that are appreciable over the size of the robot. The approach more suitable for nanoscale robotics is, therefore, based on global, spatially uniform, control fields. All current strategies to achieve selective control with nanobots are based on differences between individual nanobots20,21 in their response to a global control field, which poses a fundamental limitation to the number of nanobots that can be maneuvered independently22. Examples include dye-loaded nanotree23 swimmers that can be driven selectively by using light of the appropriate wavelength or magnetic microbots that respond differently to a global magnetic drive through differences in their surface24, direction25, and strength26 of magnetization, or in their interactions with the surface25 of the fluidic chamber.

The challenge that emerges is the following: can we selectively address and actuate an individual bot, from within a system of nanobots that are completely identical27? As we show here, this can be achieved through controlled and intermittent randomization of the orientation of the nanobots, followed by a global drive that depends on the spatial configuration of the entire collection. The method can be applied to many experimental platforms, and here, we demonstrate the strategy with helical magnetic nanobots. The chosen system is highly biocompatible28 and can be rendered multifunctional with capabilities for cargo manipulation, sensing, and therapeutic potential, all of which are desirable for biological29 applications of futuristic nanobots.

Results

As shown in the schematic shown in Fig. 1, we consider a strategy to move nanobot A along a certain trajectory (brown line), while keeping nanobot B fixed at its location. Upon application of the external drive (shown by the blue arrow), the nanobots orient and move toward the direction defined by the drive. Consider Fig. 1A, where both nanobots are initially \(t=0\) aligned along the same direction. The angles \({\alpha }_{A}(={\alpha }_{B})\) are defined with respect to the initial orientation and the direction of the intended trajectory for nanobot A. Upon application of the external drive, the nanobots re-orient in a characteristic timescale \({\tau }_{A}(={\tau }_{B})\) to align along the intended direction and then move along parallel trajectories. As evident from the schematics, this cannot result in selective manipulation. Next, consider Fig. 1B, where the initial orientations (\({\alpha }_{A}\ne {\alpha }_{B}\)) of the nanobots are different. Upon application of the control drive, the bot whose orientation is closest to the drive direction (here, nanobot A), starts to move immediately along the intended trajectory. The other bot turns over a certain duration (\({\tau }_{B}\)), which depends on its initial orientation (\({\alpha }_{B}\)) and then starts moving along the intended trajectory. The key point to note is the existence of a short window of time \({\tau }_{B}\), during which one bot moves along an externally defined trajectory while the other one has negligible displacement. This is the underlying principle that can lead to differential and selective displacements of the nanobots that are otherwise completely identical.

A Same initial orientation for nanobots A and B: Upon application of an external drive along a different direction results in identical displacements of the two nanobots. B Different initial orientations: Times taken by nanobots to orient along the externally defined direction, and therefore corresponding displacements are different. This is the fundamental mechanism to achieve selective control. For simplicity, the initial orientation for nanobot A was taken to be parallel to the direction of the intended trajectory. C Schematic of the control algorithm based on real-time information processing and feedback.

We consider bots whose direction of motion under a certain external drive is fixed with respect to its body axis, as would be the case for most driven systems that are rendered motile through external fields. There are many strategies currently available to drive nanobots remotely, of which magnetic field is especially promising due to its inherent compatibility with living systems and applicability under both in vivo and ex vivo environments. The experimental system chosen here is based on ferromagnetic helical30,31 nanostructures (see schematic and scanning electron micrograph shown in Fig. 2A), which are driven by rotating magnetic fields. The magnetic drive results in rotation and, therefore, translation of the helical nanobot, along a direction determined by the sense of rotation of the field and handedness32 of the helix. For rotation frequencies lower than a critical value (step-out frequency) \({\Omega }_{{so}}\), the speed is proportional to the hydrodynamic pitch of the helix and the frequency. The step-out frequency physically represents the highest angular frequency that a nanobot can attain. Typical experiments are carried out in a microfluidic chamber placed within a triaxial Helmholtz coil and an optical microscope.

A Schematic representation of a helical nanobot with magnetic moment \(m\), under the action of rotating (red arrow) magnetic field of strength \(B\), moves along the direction shown by the blue arrow. B The variation of the turning time (\(\tau\))as a function of its initial orientation \(\alpha\) with respect to the drive direction. The experimental values (shown as black squares) are averaged over 10 measurements. Also shown are the results of the numerical calculations (red dotted line) under equivalent experimental conditions. Data are presented as mean value \(\pm\) standard error of the mean. C Two examples of time-lapse images of a nanobot turning upon the application of a rotating magnetic drive. The initial orientation of the nanobot was at angle α = 70° (top panel) and α = 30° (bottom panel) with respect to the externally defined direction (blue arrow).

The dependence of the turning time \(\tau\) on the initial orientation \(\alpha\) is an important component of the proposed strategy. In Fig. 2C, we show snapshots of the turning of the nanobots upon application of the experimental drive for two initial orientations α = 70° and α = 30°, shown in the top and bottom panels, respectively. The variation of \(\tau\) on \(\alpha\) from multiple experiments is shown in Fig. 2B. Also shown are the results of the numerical calculations following the theoretical framework developed previously33,34, which matches closely with the experiments. Please see the materials and methods section for more details on the fabrication steps, experimental procedure, and numerical calculations. The experimental demonstration of this dynamical behavior of nanobot is available in Supplementary Movie 1; please refer to the supplementary information for further details. Note the value \(\tau\) in our experiments varied between 0.5 and 1.5 s, which in turn depends on the details of the system, such as the dimensions and magnetic properties of the nanobots.

Another crucial component of the proposed strategy relies on randomization of the bot orientations on demand. As the nanostructures are suspended in a fluid, a simple strategy would be to wait for their orientation to be randomized through Brownian diffusion35. This can be a slow process depending on the experimental system. For example, in a medium of viscosity \(\sim 1\) cP, the randomization time for a robot of length 4.2 μm is expected to be around 2 s. We instead used a strategy based on bistability20,36 of the helical structures that allowed us to achieve the randomization significantly faster. The method is described schematically in Fig. 3A, based on a bistability phenomenon reported previously33 on the same experimental system. The bistability here corresponds to the random switching of the externally driven helical nanobots between two dynamical configurations: tumbling and propelling states for drive frequencies above the step-out frequency, \({\Omega }_{{so}}\). The origin of this phenomenon arises due to multiple possible stable configurations of elongated structures under external torque and the role of thermal fluctuations, as investigated previously with analytical34,37 and numerical33 calculations.

A Schemtaic representation of “propulsion” and “tumbling” dynamical states, along with a time sequence of the bistable dynamics randomly jumping between the two states. The rotating drive in the xy-plane is stopped intermittently so as to get the nanobots oriented along random directions. The numerically calculated time series of the orientation angles for two nanobots show time windows when they are in the same state (inset i) and when they are not (inset ii). B Histogram of the orientation angles measured experimentally (\({\theta }_{A}\) and \({\theta }_{B}\)) for the nanobots A and B, respectively. C Screenshots of two nanobots intermittently randomized as per the schematic shown in panel (A). The symbols “Propulsion” and “Tumbling” correspond to two dynamical states during the bistable regime. D Plot of the orientations for the two nanobots after every randomization step conforms to the lack of correlation with each other. E Experimental screenshots of four nanobots during randomization demonstrate that any of the nanobots can be in either the tumbling or propulsion state at any given moment, with these state transitions occurring independently and uncorrelated with one another.

As shown in the schematic in Fig. 3A, we apply the rotating field in the xy-plane (see schematic of Fig. 3A), which results in a few of the nanobots aligned along the z-direction (propelling state) while others rotating asynchronously in the xy-plane (tumbling state). The z-confinement provided by the microfluidic chamber limits the propelling nanobots to remain in the imaging plane. As the xy-rotating field is switched off, different nanobots were found to be oriented along random directions. Results of the experiments are shown in Fig. 3C, showing snapshots of two nanobots at different instances of the controlled randomization process. The experimental results show the two states (denoted by “Propulsion” and “Tumbling”) of the nanobots when the drive is applied and show their random orientations (\({\theta }_{A}\) and \({\theta }_{B}\)) with respect to the system x-axis, of the two nanobots after the drive is turned off. We have confirmed over 100 randomization events and detailed statistical analysis that the orientations of the bots were not correlated to each other and were independent of the past can be inferred from Fig. 3B, D. Details of this analysis and experimental conditions are available in the supporting information. Finally, in Fig. 3E, we demonstrate the randomization protocol applied to four nanobots, which clearly shows the orientation of the nanobots after each randomization event to be independent of each other, as well as to their past orientations. Supplementary Movie 2 has been provided in supplementary information in which the randomization of nanobot’s orientation can be observed, and the two states of the nanobot in the xy-rotating magnetic field, namely, “Propulsion” and “Tumbling,” are demonstrated.

In Fig. 4A, we describe the algorithm along with an experimental demonstration of selective and independent control. In the example shown here, nanobot A is maneuvered along a pre-defined trajectory while nanobot B is held at the location. Please note that our method can be easily generalized to more complex trajectories and, more importantly, to a larger number of nanobots, as shown later. The initialization step (see Fig. 4A) corresponds to identifying the two nanobots through standard image acquisition and analysis and subsequently defining the trajectory to be followed by bot A and the location where bot B will be confined. The next step is to randomize their orientations (see Fig. 4A) as per the methodology outlined earlier and then estimate the orientations of the two bots, given by \({\alpha }_{A}\) and \({\alpha }_{B}\) measured with respect to the pre-defined trajectory for bot A. The decision to apply the drive along the trajectory is taken if, \({\alpha }_{A}\) is close to the intended direction (yes: if \({\alpha }_{A} < {\delta }_{\alpha }\)) and if \({\theta }_{A}\) is sufficiently smaller than \({\theta }_{B}\) (yes: \({\theta }_{B}-{\theta }_{A} > \Delta\)). The drive was applied for a duration of time \({T}_{{\rm{drive}}}\), during which bot A moved by a short distance, and bot B only re-oriented, while remaining in its location (see Fig. 4A). If the estimated \({\alpha }_{A}\) was found to be comparable or larger than \({\alpha }_{B}\), no drive was applied, but instead the randomization step would be applied. These steps: randomization—estimation—decision—drive was carried out in a loop till the intended trajectory was completed.

A Adaptive control algorithm: organizational flow diagram of the algorithm where the visual feedback block computes the parameters designated for efficient decision-making to implement independent control. The algorithm adjusts magnetic field actuation parameters after each Tdrive based on real-time image feedback to guide nanobots to their target positions. B Optimization of Tdrive for selective control: The intended and actual trajectories for the nanobots (red and green) actuated for different constant and adaptive propulsion times are shown, the initial position of the nanobot is demonstrated as ‘o’ and programmed final position demonstrated as ‘x’. (i)–(iv) and (vii)–(x) show the actual trajectory for nanobots performed by the strategy of “constant propulsion timing” in which one is programmed to be trapped in a circle, and the other is programmed to travel in a vertical straight line. (v) and (vi) show the actual paths traversed by the nanobots following the “adaptive propulsion timing” protocol. Figure of merit and speed of different propulsion timing methods compared to deduce the most efficient protocol for independent positioning of nanobots.

The algorithm mentioned here considers the possibility that the bots are subject to thermal fluctuations, and therefore bot B can be localized from its original position. This shows functional similarity to what was achieved with the “ABEL” trap38 using electrokinetic forces. The results of the experiments are shown in Fig. 4B. The algorithm considers the present location of the nanobot B after each randomization step and defines a trajectory from its current to the pre-defined fixed location. We image and subsequently calculate the misalignment of their initial orientations to respective intended trajectories given by the angles \(\Delta {{\alpha }}_{A}\) and \(\Delta {{\alpha }}_{B}\). The decision of whether to apply the drive and, if so, in which direction was based on a consideration like before. The choices \(\Delta \alpha=\min \left(\Delta {\alpha },\Delta {\alpha }\right) < {\delta }_{\theta }\) and the difference \(\Delta \theta=\left|{\theta }_{A}-{\theta }_{B}\right| > \Delta\) ensured that only the bot closer to its intended direction of motion is actuated. In the example shown here, we found \(\Delta {\alpha }_{B}\) it to be smaller by a significant amount and, therefore, moved toward the fixed point. We carry out the steps of randomization—estimation—decision—drive repeatedly till nanobot A can complete its trajectory, while actively confining nanobot B in its original location.

Two crucial components of this algorithm are (i) the decision to apply drive or not, which depends on the spatial configuration parameters, \({\delta }_{\alpha }\) and \(\Delta\), and (ii) drive duration, \({T}_{{\rm{drive}}}\). It is easy to see how the accuracy and speed of selective manipulation depend on the choice of these important parameters. Smaller \({\delta }_{\alpha }\) and larger \(\Delta\) imply one would have to wait for several randomization steps for the drive condition to appear, and therefore increase the time to complete the procedure. Note, however, that this can be countered by a choice of drive duration \({T}_{{\rm{drive}}}\). Similarly, the choice of a larger \({\delta }_{\alpha }\) and smaller \(\Delta\) can compromise the accuracy by resulting in unwanted motion of one of the nanobots, unless the drive duration \({T}_{{\rm{drive}}}\) is made very small.

To investigate the crucial importance of the drive duration, we show trajectories for different choices of \({T}_{{drive}}\). For a small value of \({T}_{{\rm{drive}}}=\) 100 ms, the process was very slow, and the desired trajectory, although accurate, could not be completed (Fig. 4B, panel (i) and (ii)). Here, bot A could cover \(20\) µm in \(\sim 23\) min, implying an effective speed of 0.87 μm/min. For a higher value of \({T}_{{drive}}=\) 1000 ms, the achieved trajectory (Fig. 4B, panel (vii) and (viii)) deviated too much from what was intended; for example, at certain times during the manipulation procedure, the bot B was found to be almost ~17.5 μm away for its original intended location. For “Adaptive” timing with average \({T}_{{\rm{drive}}} \sim\) 760 ms (for mathematical description, refer to Supplementary Information), the effective speed of bot A and maximum displacement of bot B were found to be 2.25 μm/min and 2 μm, respectively; implying a reasonable compromise when compared with the results obtained from the constant duration of propulsion. Further discussion on a metric to quantify the speed and accuracies of the manipulation scheme, along with experimental results, are provided in the supporting information, which proves a choice of \({T}_{{\rm{drive}}}\) between 0.75 and 1.0 s indeed provides an optimal solution.

Finally, we consider the case when \({T}_{{\rm{drive}}}\) was modified depending on the value of \(\alpha\), as per the experimental and numerical results shown in Fig. 2B. This implied applied a longer drive for larger turning angles, and similarly smaller \({T}_{{\rm{drive}}}\) when \(\alpha\) was less. We kept the condition for \(\Delta=30^\circ\) as before. The results for this “adaptive” \({T}_{{\rm{drive}}}\) provided an optimum balance between speed and accuracy, as seen in panel (v) and (vi) of Fig. 4B (also discussed in Supporting Information), the corresponding experimental videos related to Fig. 4 (Supplementary Movies 3–5) are provided in the Supplementary Information.

The speed of trajectory completion in the strategy described in this manuscript is primarily influenced by two factors: the probability of a “True” propulsion condition and the duration of propulsion (\({T}_{{\rm{drive}}}\)). Let’s consider two nanobots, A and B. We aim to move nanobot A while keeping B stationary. Initially, the “True” propulsion condition was defined as the state where the two nanobots are tumbling but not aligned in orientation, i.e., \({\theta }_{A}\ne {\theta }_{B}\). However, during bistability, there’s a distinct possibility that nanobot A may be tumbling and aligned toward the intended direction (\({\alpha }_{A} < {\delta }_{\alpha }\)), while nanobot B is in a propulsion state. This state is also a valid actuation condition since the target nanobot (A) is oriented toward the desired direction while nanobot B is perpendicular to it. Applying a rotating magnetic field under these conditions immediately initiates movement in nanobot A, while nanobot B, needing time \(\tau\) to align itself, remains effectively stationary, achieving independent control. By incorporating this scenario into the algorithm, we increase the probability of propulsion condition.

For optimal algorithm efficiency, it is essential that the turning time (\(\tau\)) is maximized. From Fig. 2B, it is clear that \(\tau\) is maximum for \(\alpha \sim 90^\circ\), though with considerable uncertainty. While previous method, “Adaptive Time” relies on setting \({T}_{{\rm{drive}}}\) to mean turning time values, this high variability could lead to incorrect decisions. Instead of depending on a predefined condition for \(\tau\) to achieve \(\alpha \sim 90^\circ\) relationship, our approach monitors the real-time orientation of each nanobot, dynamically assessing whether to attempt propulsion of a certain nanobot along the pre-defined direction. Once nanobot B aligns with the intended direction, we stop propulsion and initiate randomization through bistability again, ensuring by this time nanobot A has progressed along the chosen direction by a certain amount. This real-time feedback significantly enhances the FERRIC method’s efficiency over previous approach, albeit requiring fast image acquisition, analysis and instrumentation control. The flow diagram of the FERRIC method is shown in Fig. 5A.

A Feedback enhanced rapid randomization-based independent control (FERRIC) algorithm: organizational flow diagram of the algorithm where the visual feedback block implemented in parallel architecture with multi-cascaded information stages. The algorithm computes the duration of magnetic field applied for randomization and propulsion depending on the real-time information of the location and orientation of the nanobots. The fast feedback allows the nanobots to their target positions rapidly and accurately on two identical nanobots namely, NBA and NBB. B Variation in velocity of nanobots NBA and NBB as a function of rotational frequency of magnetic field. Data are presented as mean value \(\pm\) standard error of mean. C Experimental results presenting the bistable dynamics of nanobots, A and B. The nanobots are actuated at the rotational frequency of 25 Hz which is higher than the cut-off frequency of structures (20 Hz). D Statistical representation of the orientation angles θ for the nanobots NBA and NBB with blue and red color histograms, respectively. E The intended (white) and actual trajectories for the nanobots (red and green) actuated for different programmed trajectories denoted by the alphabets (i) “I” and “C”, and (ii) Inverted “V” and “G”. The scale bar denotes a length of 10 µm.

It is important to note that the results presented here (and elsewhere in the manuscript) are with nanobots whose differences in magnetic and hydrodynamic properties, are negligible. To ensure their magnetization direction is the same, we subjected two nanobots designated as NBA and NBB, to a static magnetic field and measured the angle \({\theta }_{M}\), which is the angle between their short axis and the applied magnetic field. The measured angles were \({{{\rm{\theta }}}}_{{{\rm{M}}}}=4.95^\circ \pm 1.0^\circ\) for nanobot NBA and \({{{\rm{\theta }}}}_{{{\rm{M}}}}=5.82^\circ \pm 1.46^\circ\) for nanobot NBB, showing alignment within experimental error. The results are presented in Fig. 5B, where from the variation of speed as a function of the rotating field frequency, it is clear that the experimental nanobots are very close with respect to their magnetic moment (step-out frequency) and hydrodynamic pitch. The results of the randomization experiment are plotted in Fig. 5C, D, which denotes the dynamic state in bistability and the angular position, respectively. Symbol ‘1’ represents ‘propulsion’, and ‘0’ shows ‘tumbling’. Initially, the nanobots transitioned between these states in synchronization, but after 10–11 s, their transitions became independent of each other, i.e., became non-deterministic and led to the randomized orientation of the nanobots which can be observed in Fig. 5D in the uniform distribution the angular orientations.

With these two identical nanobots, we experimentally verified the FERRIC method by first programming the input trajectories as “I” and “C” for nanobots, standing for acronyms of Independent Control, as presented in Fig. 5E (i) and in Supplementary Movie 6. The comparison with the intended trajectory clearly demonstrates the accuracy of the control algorithm. The speed of trajectory execution is approximately 100 μm/min, which is significantly higher than the ‘Adaptive Timing’ method. This occurs, as mentioned before, due to the enhanced rate at which the randomization condition is achieved (average 1 events per minute) compared to the results shown in Fig. 5C (average 20 events per minute). We further programmed the input trajectories in the shapes of an inverted “V” and “G.” Both Fig. 5E (ii) and Supplementary Movie 7 show the experimental results, demonstrating the robustness of the algorithm in managing increased complexity in trajectory patterns.

The demonstrations of being able to move one nanobot while keeping the other one fixed, acts as a building block to achieve selective and independent control over more than two particles, as well as more complicated trajectories. We generalized the algorithm to more than two nanobots, by modifying the following, \(\Delta \alpha=\min \left(\Delta {\alpha }_{i}\right) < {\delta }_{\alpha }\) and the difference \(\left|{\theta }_{i}-{\theta }_{j}\right| > \Delta\). Here, \(i\) and \(j\) refer to identifiers for nanobots whose orientations are closest and second closest to their respective intended trajectories. The results are shown in Fig. 6, sometimes there are more bots in the field of view than the intended pattern, so we used an advanced feature extraction algorithm incorporated with nearest neighbor algorithm (details are mentioned in supporting information) that filters the redundant nanobots, and the computational speed of the algorithm is not affected by the presence of the redundant nanobots. We used a technique known as “dot matrix calligraphy” (for further details, refer to Supplementary Materials) to define the complex trajectories over which nanobots are manipulated, where the trajectories are divided in the form of dots. We follow the same principle described in the previous section to manipulate individual nanobots from one dot to another, using the parallel control. The intended and the actual trajectories are shown in Fig. 6A (i)–(v), along with the target and final positions, refer to the Supplementary Movies 8–11 which are provided in the supplementary information for further information about the experiments. This level of selective and independent control over more than two nanobots has not yet been demonstrated in the literature.

A Screenshots of the achieved and intended trajectories for different number of nanobots operated with parallelly addressed control system. The symbol ‘o’ demonstrates the initial position of nanobots, programmed target position is demonstrated as ‘■’ and the final position of respective nanobot is represented as ‘x’. (i) and (v) Two nanobots are manuevered along perpendicular trajectories, while the third nanobot is localized at its position. (ii) Three nanobots are localized at one place, while the fourth bot is moving in a straight line. (iii) Two nanobots moved along perpendicular trajectories, while two bots are held in a place. (iv) Two nanobots are held at respective initial positions,while the third nanobots moved in a straight line. Scale bar denotes the length of 10 µm. (the trajectories are scaled and shifted with respect to the actual experiments for demonstration purpose, for further details refer Supplementary Movies 8–11). B Four nanobots trace programmed trajectories with sequentially addressed control system, the trajectories describe out the letters “I”, “I”, “S”, and “C”. The length of the scale bar is 10 µm.

We have also carried out the same demonstrations using sequential control, where one nanobot is manipulated at a single instant as shown in Fig. 6B and in Supplementary Movie 12. In the example shown, we have maneuvered them to depict the initials of our institute, IISc (Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore). The manipulation was made by the faster FERRIC method, with average speed maintained at approximately 37 μm/min. While this is slower than 100 μm/min achieved for two nanobots systems, it is still significantly faster than the ‘Adaptive Timing” method. Note that the example shown in Supplementary Movie 12 in the supplementary information uses sequential control with a subtle difference; here, we do not attempt to keep the non-actuated nanobots in a certain location. As a result, the non-actuated nanobots are subject to position randomization of magnitude \(\sim \surd (2D{t}_{{\rm{expt}}})\), shown with a bar graph in the movie assuming the diffusivity of a \(1\,\mu m\) bead. Because the process is faster in general, the diffusional displacement for the non-actuated nanobots is still less than the motion intended for actuated nanobots. In principle, it is possible to ensure that the displaced non-actuated bots are periodically actuated to bring them back to their intended locations.

Discussion

The present technique relies on direct imaging and subsequently estimating the nanorobot orientations, which limits the minimum length of the bots to greater than a micron using a microscope objective of high magnification (100×) and numerical aperture (1.3 NA). It may be possible to determine the orientation of shorter nanobots using polarization-dependent scattering, which will also allow us to image the system with lower magnification, i.e., a bigger field of view, and therefore image and control a greater number of nanobots. In the experiments shown here, the distance between the nanobots is large enough such as to neglect the inter-nanobot fluidic and magnetic interactions39, which can be significant for the denser suspension of nanobots. This is a very system dependent challenge, for example here we use bistability for slightly larger bots, while faster randomization can be achieved for shorter bots through thermal fluctuations.

We also stress that the problem addressed here is about individual control within a swarm of robots, as opposed to controlling the behavior of a swarm, which for helical magnetic nanobots, may or may not be self-propelled40,41. Controlling a swarm can be achieved through careful engineering of inter-robot communications, which in macroscale robotics can occur through radio frequency signals42, while at smaller scales, the robots can interact through hydrodynamic or magnetic forces showing various swarm43 behaviors. Inter-robot interactions can become important at high densities, and it will be interesting in the future to investigate the effect of fluidic interactions on the control strategy demonstrated in the article.

To summarize, we have described a method of independent manipulation and positioning of nanobots using global control fields. Unlike previous techniques that rely on differences between individual nanobots with respect to their geometry, material, or surface properties, our strategy can work with robots that are completely identical. The present experimental system is versatile enough to have multiple functionalities integrated within a single robot, including sensing, cargo manipulation4, local heating44, etc., and therefore can find use in situations that require parallelized and precise assembly45 of nanoscale components, sensing46 or actuation of individual components in a microfluidic environment, including intracellular47 media. The technique is versatile enough to be useful in other experimental platforms48, across many scales. An obvious next step will be to integrate magnetic elements with chemically49, acoustically50 or optical51 powered nanobots, where the randomization can be induced by thermal fluctuations. For larger objects, vibrations induced by acoustic fields may provide alternate techniques for randomization. The technique can be extended to dry systems as well, e.g., robots that crawl or depend on rocking motion on a surface52. Finally, we envision situations in macroscale robotics where local control is not preferred or possible, for example hazardous environments where it is not possible to control individually, rather applying a global drive.

Methods

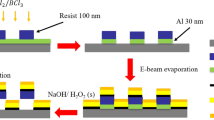

Fabrication of nanobots

The SiO2 nano helices were fabricated using the glancing angle deposition (GLAD) method on the seed layer of 900 nm polystyrene beads. A monolayer of 900-nm polystyrene particles was deposited from Langmuir–Blodgett (LB) on a silicon wafer. Once the helices were fabricated, they were taken out from the wafer into water by sonication, and the solution was then put onto a pre-cleaned Si wafer so that the helical structure was laid down randomly on the surface. A metal evaporation step was performed on the laid down structures in which ferromagnetic materials were deposited on them using thermal evaporation. Depending on the requirement of the magnetic moment of the nanobot, the thickness of the layer of magnetic material of thickness ~30 nm.

Experimental procedure

The first step to carrying out an experiment was to make a microfluidic chamber where the nanobots were dispersed in water or other viscous medium. A small piece of the wafer (5 mm \(\times\) 5 mm) containing the laid down helices was taken and sonicated in an Eppendorf tube with de-ionized (DI) water (or any other fluid depending on the experiment), because of which the nanobots were detached from the wafer and were dispersed in the solution. Depending on the thickness of the microfluidic chamber/cell required, a specific volume of the solution was then put between a piranha-cleaned coverslip (18 mm2) and a glass-slide. The cell was then mounted on the triaxial Helmholtz coil to actuate the nanobots with an external rotating magnetic field. Supplying currents to the three coils, acquiring, and processing the images could be carried out synchronously, all controlled by a powerful desktop. A data acquisition device (DAQ) was also connected to the desktop to generate voltage signals according to the magnetic field generation commands. The device was configured to send 3000 samples/s which can generate signals up to a frequency of 1.5 kHz, this parametric setting provides the user with enough bandwidth to operate in a comparable range of frequencies. The DAQ was connected to constant current amplifiers that were used to generate the magnetic fields in the tri-axial Helmholtz coil. A CMOS camera was used to take snapshots of the bots, which could be used to determine their orientations on the fly.

Numerical calculations

To estimate the time of turning (\(\tau\)) for the nanobots, we simulated the dynamics of the system with experimental parameters. We modeled the helix as an ellipsoid, whose long and short axes are equal to the length and width of the helix34. For an ellipsoid, the drag coefficients along short and long axes are given as,

and

respectively. Here,

where μ is the viscosity of water (=\(9\times {10}^{-4}\) Pa s, \(a=(4.5\,\mu{{\rm{m}}})\)) and \(b\left(=0.5\,\mu{{\rm{m}}}\right)\) are the lengths of the semi-major and semi-minor axes of the ellipsoid respectively. With these experimental parameters, we obtained \({\gamma }_{s} \sim\) \(1.55\times {10}^{-20}\) kg m2/s and \({\gamma }_{L}\sim 6.27\times {10}^{-21}\) kg m2/s. The strength of the magnetic moment and the magnetic field were chosen to be \(2.3\times {10}^{-16}\) A/m2 and 50 Gauss, respectively.

Like our previous results, we followed the x-convention in our simulation, where at any instant of time \(t\), the orientation of the nanobot was represented by unit quaternion,

The magnetic moment is chosen to be along \({\theta }_{m}\) direction with respect to the long axis of the nanobot and is represented in a vector form as

in the body fixed coordinate system, where m is the strength of the magnetic moment. Here, ‘T’ represents transpose. In the simulation, we have assumed \({q}_{m}=\) 0°. As a starting point of the simulation, initial orientation of the nanobot was set to be along a direction (lab X axis, here), in the absence of any magnetic field. We then applied a rotating magnetic field, orthogonal to lab XY plane, but along a certain direction with lab X axis (represented by ‘Angle of turning’ in Fig. 2D). The applied magnetic field in lab fixed coordinate is given by

where B represents magnetic field strength, \(\varOmega\) represents the angular frequency of the rotating field, and t represents time. The time of turning (\(\tau\)) for the nanobots was calculated via angular velocities (\({\Omega }_{{\rm{BF}}}\)), derived from the Stokes law. This was calculated in the body frame of reference by the following equation,

where

is the frictional tensor. The dynamical evolution of the system was calculated by updating the quaternions from their time rate by

where

and

The time-step of the dynamical equation (\(\Delta t\)) is equal to 10−5 s, which is smaller than any timescale associated with the system. It is to be noted that the frequency of the magnetic field, \(\Omega\), is chosen to be close to the step-out frequency of the nanobot, which is given by \(\frac{{mB}}{{\gamma }_{l}}\).

Data availability

The data generated in this study have been deposited in the Zenodo database under the accession code 14849474. Contact Ambarish Ghosh for further requests of any other additional materials.

References

Wu, Z. et al. A microrobotic system guided by photoacoustic computed tomography for targeted navigation in intestines in vivo. Sci. Robot. 4, eaax0613 (2019).

Cappelleri, D., Efthymiou, D., Goswami, A., Vitoroulis, N. & Zavlanos, M. Towards mobile microrobot swarms for additive micromanufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 11, 150–163 (2014).

Jeon, S. et al. Magnetically actuated microrobots as a platform for stem cell transplantation. Sci. Robot. 4, 1–12 (2019).

Li, J. et al. Micro/nanorobots for biomedicine: delivery, surgery, sensing, and detoxification. Sci. Robot. 2, 1–10 (2017).

Palagi, S. et al. Structured light enables biomimetic swimming and versatile locomotion of photoresponsive soft microrobots. Nat. Mater. 15, 647 (2016).

Yang, Y. et al. Optimal navigation of self-propelled colloids. ACS Nano 12, 10712–10724 (2018).

Bechinger, C. et al. Active particles in complex and crowded environments. Rev. Modern Phys. 88, 045006 (2016).

Bogue, R. Microrobots and nanorobots: a review of recent developments. Ind. Robot. 37, 341–346 (2010).

Pawashe, C., Floyd, S. & Sitti, M. Multiple magnetic microrobot control using electrostatic anchoring. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 92–95 (2009).

Dai, B. et al. Programmable artificial phototactic microswimmer. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 1087–1092 (2016).

Kim, S. et al. Fabrication and manipulation of ciliary microrobots with non-reciprocal magnetic actuation. Sci. Rep. 6, 30713 (2016).

Ren, L. et al. 3D steerable, acoustically powered microswimmers for single-particle manipulation. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax3084 (2019).

Petit, T. et al. Selective trapping and manipulation of microscale objects using mobile microvortices. Nano Lett. 12, 156–160 (2011).

Gross, R., Bonani, M., Mondada, F. & Dorigo, M. Autonomous self-assembly in swarm-bots. IEEE Trans. Robot. 22, 1115–1130 (2006).

Li, J. et al. Development of a magnetic microrobot for carrying and delivering targeted cells. Sci. Robot. 3, eaat8829 (2018).

Mei, Y., Solovev, A. A., Sanchez, S. & Schmidt, O. G. Rolled-up nanotech on polymers: from basic perception to self-propelled catalytic microengines. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 2109–2119 (2011).

Muñoz, E. M., Quispe, J. E. & Vela, E. Closed-loop selective manipulation of multiple microparticles by controlling the transient regime of Marangoni flows. in 2016 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). https://doi.org/10.1109/IROS.2016.7759754 (2016).

Diller, E., Giltinan, J., Jena, P. & Sitti, M. Independent control ofmultiple magnetic microrobots in three dimensions. Proceedings—IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICRA.2013.6630929 (2016).

Rahmer, J., Stehning, C. & Gleich, B. Spatially selective remote magnetic actuation of identical helical micromachines. Sci. Robot. 2, eaal2845 (2017).

Bachmann, F., Bente, K., Codutti, A. & Faivre, D. Using shape diversity on the way to structure-function designs for magnetic micropropellers. Phys. Rev. Appl. 11, 034039 (2019).

Morozov, K. I., Mirzae, Y., Kenneth, O. & Leshansky, A. M. Dynamics of arbitrary shaped propellers driven by a rotating magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2, 044202 (2017).

Vach, P. J., Klumpp, S. & Faivre, D. Steering magnetic micropropellers along independent trajectories. J. Phys. D 49, 065003 (2016).

Zheng, J. et al. Orthogonal navigation of multiple visible-light-driven artificial microswimmers. Nat. Commun. 8, 1–7 (2017).

Wang, X. et al. Surface-chemistry-mediated control of individual magnetic helical microswimmers in a swarm. ACS Nano 12, 6210–6217 (2018).

Mandal, P., Chopra, V. & Ghosh, A. Independent positioning of magnetic nanomotors. ACS Nano 9, 4717–4725 (2015).

Mahoney, A. W., Nelson, N. D., Peyer, K. E., Nelson, B. J. & Abbott, J. J. Behavior of rotating magnetic microrobots above the step-out frequency with application to control of multi-microrobot systems. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 1–5 (2014).

Howell, T. A., Osting, B. & Abbott, J. J. Sorting rotating micromachines by variations in their magnetic properties. Phys. Rev. Appl. 9, 054021 (2018).

Venugopalan, P. L. et al. Conformal cytocompatible ferrite coatings facilitate the realization of a nanovoyager in human blood. Nano Lett. 14, 1968–1975 (2014).

Qiu, F. & Nelson, B. J. Magnetic helical micro- and nanorobots: toward their biomedical applications. Engineering 1, 021–026 (2015).

Ghosh, A. & Fischer, P. Controlled propulsion of artificial magnetic nanostructured propellers. Nano Lett. 9, 2243–2245 (2009).

Fischer, P. & Ghosh, A. Magnetically actuated propulsion at low Reynolds numbers: towards nanoscale control. Nanoscale 3, 557–563 (2011).

Schamel, D. et al. Chiral colloidal molecules and observation of the propeller effect. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 12353–12359 (2013).

Ghosh, A., Paria, D., Singh, H. J., Venugopalan, P. L. & Ghosh, A. Dynamical configurations and bistability of helical nanostructures under external torque. Phys. Rev. E 86, 1–5 (2012).

Ghosh, A., Mandal, P., Karmakar, S. & Ghosh, A. Analytical theory and stability analysis of an elongated nanoscale object under external torque. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 10817–10823 (2013).

Ghosh, A., Paria, D., Rangarajan, G. & Ghosh, A. Velocity fluctuations in helical propulsion: how small can a propeller be. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5, 62–68 (2014).

Meshkati, F. & Fu, H. C. Modeling rigid magnetically rotated microswimmers: rotation axes, bistability, and controllability. Phys. Rev. E 90, 063006 (2014).

Morozov, K. I. & Leshansky, A. M. The chiral magnetic nanomotors. Nanoscale 6, 1580–1588 (2014).

Wang, Q., Goldsmith, R. H., Jiang, Y., Bockenhauer, S. D. & Moerner, W. E. Probing single biomolecules in solution using the anti-brownian electrokinetic (ABEL) trap. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 1955–1964 (2012).

Tierno, P., Golestanian, R., Pagonabarraga, I. & Sagués, F. Controlled swimming in confined fluids of magnetically actuated colloidal rotors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 1–4 (2008).

Mandal, P., Patil, G., Kakoty, H. & Ghosh, A. Magnetic active matter based on helical propulsion. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 2689–2698 (2018).

Mandal, P. & Ghosh, A. Observation of enhanced diffusivity in magnetically powered reciprocal swimmers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 1–5 (2013).

Rubenstein, M., Cornejo, A. & Nagpal, R. Programmable self-assembly in a thousand-robot swarm. Science 345, 795 (2014).

Xie, H. et al. Reconfigurable magnetic microrobot swarm: multimode transformation, locomotion, and manipulation. Sci. Robot. 4, 1–15 (2019).

Venugopalan, P. L., Jain, S., Shivashankar, S. & Ghosh, A. Single coating of zinc ferrite renders magnetic nanomotors therapeutic and stable against agglomeration. Nanoscale 10, 2327–2332 (2018).

Ghosh, S. & Ghosh, A. Mobile nanotweezers for active colloidal manipulation. Sci. Robot. 3, eaaq0076 (2018).

Ghosh, A. et al. Helical nanomachines as mobile viscometers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1–6 (2018).

Pal, M. et al. Maneuverability of magnetic nanomotors inside living cells. Adv. Mater. 30, 1–7 (2018).

Zhang, L., Peyer, K. E. & Nelson, B. J. Artificial bacterial flagella for micromanipulation. Lab a Chip 10, 2203–2215 (2010).

Paxton, W. F. et al. Catalytic nanomotors: autonomous movement of striped nanorods. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 13424–13431 (2004).

Ahmed, D. et al. Selectively manipulable acoustic-powered microswimmers. Sci. Rep. 5, 1–8 (2015).

Ibele, M., Mallouk, T. E. & Sen, A. Schooling behavior of light-powered autonomous micromotors in water. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 3308–3312 (2009).

Palagi, S. & Fischer, P. Bioinspired microrobots. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 113–124 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Debayan Dasgupta, Gouri Patil, Malay Pal and Reshma V.R. for helpful discussions regarding fabrication of nanobots. The authors thank RBCCPS, DBT, DST-BRICS, and DST-AMAT for funding this research. We also acknowledge funding from MHRD, MeitY and DST Nano Mission for supporting the facilities at CeNSE.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.G. conceived and guided the research. R.G. and J.B. carried out experiments including fabrication, numerical simulations, and data analysis. P.M. helped with numerical simulations and helped with the experimental system during the initial phases of the research. R.G., J.B., and A.G. planned the paper and the presentation. All authors brainstormed together during the research.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Goyal, R., Behera, J., Mandal, P. et al. Externally controlled intermittent randomization enables complex navigation of multiple nanobots. Nat Commun 16, 2700 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58092-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58092-y