Abstract

The health impact of floods has not been well characterized. This study evaluated long-term associations between cause-specific mortality rates and county-level monthly flood days (excluding coastal floods caused by tropical storms) in the post-flood year in the contiguous U.S., using a triply robust approach incorporating propensity score, counterfactual estimation, and confounder adjustment. Death records came from the CDC National Center for Health Statistics (2001-2020) and floods came from the NOAA Storm Events Database (2000-2020). We found that one flood day was associated with 8.3 (95% CI: 2.5 to 14.1) excess all-cause deaths per 10 million individuals, 3.1 due to myocardial infarction, 2.4 due to respiratory diseases, and 5.9 due to external causes. From 2001 to 2020, 22,376 (95% CI: 6,758 to 37,993) all-cause deaths were attributable to floods. Our findings highlight the long-term health risks after floods, and a need for measures to reduce these risks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Flooding can lead to huge loss of life and properties. Floods due to excessive rainfall were the third most common type of billion-dollar natural disaster event in the U.S. from 1980 to 2023, following severe storms and tropical cyclones and causing a total cost of about 200 billion dollars1. Moreover, the risk of floods is increasing, driven by the dual challenges of climate change and population growth in areas with flood risk2,3. As an example, the Missouri and Mississippi River flooding in 2019 was severe, which cost $17 billion and was directly linked to seven deaths4. However, this fatality count might not fully capture the true health impact, as it overlooks floods’ enduring direct and indirect consequences5.

The health impact of floods (e.g., drownings and other injuries) can be immediate, often occurring within days, and can extend over a longer period. Longer-term health impacts can arise directly, such as through infectious diseases, or more commonly, through indirect pathways such as deteriorated health conditions following emotional stress6 or disruption to infrastructure, social services, and medical supplies that impede access to or quality of medical care7,8.

Despite these impacts, a comprehensive assessment of the prolonged effects of floods (e.g., during the post-flood year) is lacking. A recent multi-country multi-city study found elevated risk for all-cause, cardiovascular, and respiratory mortality, but the time window was up to 60 days after floods, which captured better the short- to medium-term associations9. In contrast, a Czechian study found no significant excess deaths from cardiac diseases in the flood month10. Three other studies found contradictory results based on comparisons of all-cause death tolls between flooded versus non-flooded periods or areas in the post-flood years, without in-depth consideration of other weather variables or spatiotemporal confounding11,12,13.

In this study, we explored long-term associations between floods and cause-specific mortalities in the post-flood year in the U.S. using a triply robust approach incorporating propensity score, counterfactual estimation, and confounder adjustment (Fig. 1). We assessed the outcome and exposure by county-level age-standardized monthly mortality rates using the 2000 U.S. standard population14 (Fig. S1) and moving averages of county-level monthly flood days. We investigated 23 disease categories based on the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes (Table 1). We additionally compared such associations across flood types (flash inland floods defined as rapidly rising water within minutes to hours [generally less than six hours] versus non-flash inland floods15) and sub-populations defined by age, sex, race, and ethnicity. It should be noted that this study did not include coastal floods associated with storms of tropical origin.

We developed a triply robust approach: (1) County-month observations were assigned into treatment/control, and propensity scores of being treatment/control were estimated (named “propensity-score model”). (2) With inverse-probability weights based on propensity scores, age-standardized death counts were regressed on covariates in the control group (named “control-outcome model”). Using the fitted control-outcome model, counterfactual outcomes in the treatment group were estimated had floods not occurred. (3) In the treatment group, the residual mortality rates were regressed on the flood exposure (named “treatment-outcome model”), weighted by the inverse-probability weights calculated from propensity scores.

Results

Study characteristics

From 2000 to 2020, floods affected 99.6% of the contiguous U.S. counties (Fig. 2), and over 70% of flood days were non-flash inland floods (hereinafter referred as non-flash floods) (Table S1). There were 41,983,819 deaths from 2001 to 2020. Approximately one-third were attributed to circulatory diseases (N = 13,810,907 [32.9%]), and one-quarter were neoplasms (N = 9,749,778 [23.2%]) (Table 1). Respiratory diseases (9.6%), external causes (7.1%), and nervous diseases (6.4%) were also among the leading causes.

Individuals aged ≥65 years accounted for most all-cause deaths (74.8%), non-external deaths (78.4%), deaths for neoplasms (71.6%), and deaths for circulatory diseases (82.6%); while individuals below 64 years contributed to 73.3% of deaths from external causes (Table S2). Females and males contributed approximately equally, except that 67.9% of deaths from external causes occurred in males. Approximately 72–80% of deaths (varied by causes) occurred in non-Hispanic White populations (population share = 65.1% from 2000 to 2020), 11–14% in non-Hispanic Black populations (population share = 12.9%), and 6%-10% in Hispanic White populations (population share = 14.6%).

Association between floods and mortality

In our preliminary analysis, cause-specific associations would not extend over one year in general (Fig. S2). For example, the strongest association with all-cause mortality appeared approximately at lag 0–10 months. And taking seasonality into additional consideration, we thus selected 12 months (i.e., lag 0–11 months) as the main timespan for associations between floods and mortality.

In the year following a flood day, the excess all-cause deaths were 8.3 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.5–14.1) per 10 million individuals (Table 2).

There were 2.5 (95% CI: 0.1–5.0) excess deaths due to ischemic heart disease and 3.1 (95% CI: 1.4–4.8) due to its subcategory -- myocardial infarction. The excess deaths due to cerebrovascular diseases were 1.6 (95% CI: 0.4–2.9). Regarding respiratory diseases (excess deaths=2.4 [95% CI: 0.5–4.3]), the dominant contributor was chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD; 2.2 [95% CI: 0.6–3.7]). The excess deaths for external causes were 5.9 (95% CI: 3.6–8.2), and the major subcategory -- unintentional injuries -- had 3.1 (95% CI: 1.5–4.8), which was mostly due to injuries in transport accidents (1.7 [95% CI: 0.3–3.0]).

There were also some associations with decreased mortality. We observed –1.5 (95% CI: –2.6 to –0.4) excess deaths due to dementia. As for hypertensive diseases, a subcategory of circulatory diseases, the excess deaths were –1.0 (95% CI: –2.0 to –0.1), and its subcategory, hypertensive heart disease had –2.1 (95% CI: –2.9 to –1.4) excess deaths.

There were no significant associations between floods and other causes of death in the post-flood year.

Association by flood type

The patterns associated with non-flash floods were similar to those with all-type floods (Table 2). Excess deaths were due to all-cause, ischemic heart diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, and external causes, along with decreased deaths in hypertensive heart disease.

For flash inland floods (hereinafter referred as flash floods), patterns with circulatory diseases had the opposite direction from non-flash floods. There were decreased deaths due to ischemic heart diseases (–20.1 [95% CI: –37.6 to –2.6]) and cerebrovascular diseases (–17.7 [95% CI: –26.6 to –8.8]), while adverse associations with hypertensive diseases (12.1 [95% CI: 5.4–18.9]). Furthermore, there was no association with all-cause deaths, respiratory diseases, and aggregated external causes, which was different from non-flash floods.

We also observed excess deaths for genitourinary diseases (9.6 [95% CI: 3.5–15.6]) and decreased deaths for neoplasms (–31.2 [95% CI: –51.3 to –11.1]) and self-harm (–15.3 [95% CI: –23.9 to –6.7]) for flash floods, which was not found for non-flash floods.

For other causes, flash floods generally showed stronger associations in the same direction as non-flash floods.

Association by age, sex, race, and ethnicity

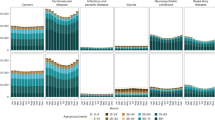

In the post-flood year, individuals aged ≥65 years had more excess all-cause (48.2 versus –0.7 in younger individuals), non-external (33.3 versus –5.7), and external (13.3 versus 4.1) deaths (Fig. 3 and Table S3).

We performed stratified analyses by age (10,596,783 individuals aged 0–64 years; 31,387,036 individuals aged above 65 years) [Panel A], sex (21,249,942 females; 20,733,877 males) [Panel B], and race and ethnicity (33,032,160 non-Hispanic White individuals; 5,037,864 non-Hispanic Black individuals; 2,690,009 Hispanic White individuals) [Panel C]. Center points indicated point estimates from models, and error bars indicated 95% confidence intervals. P values were for Q-statistics without consideration of multiple comparisons, and we considered p < 0.05 as statistically significant.

Females had more excess all-cause (12.8 versus –0.6 among males) and non-external (9.1 versus –8.9) deaths, while males had higher excess external deaths (9.8 versus 1.1 among females) (Fig. 3 and Table S4).

Among different racial and ethnic groups, we found lower excess deaths due to external causes among the non-Hispanic White population (6.6 versus 164.5 and 76.5 in non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic White populations, respectively) (Fig. 3 and Table S5).

Deaths attributable to floods

All-cause deaths attributable to floods were 22,376 (95% CI: 6758 to 37,993) (Table S6). Myocardial infarction (attributable deaths=8453 [95% CI: 3863 to 13,044]) and respiratory diseases (6390 [95% CI: 1328–11,451]) contributed to approximately 38% and 29% of attributable deaths, respectively; and around 71% were from external causes (15,925 [95% CI: 9646–22,204]). However, dementia-related and hypertension-related diseases had negative attributable deaths to floods (i.e., floods averted deaths due to dementia and hypertensive diseases).

Sensitivity analysis

When varying the time window, we observed significant increases in all-cause mortality from lag 0-3 to lag 0–11 months (Fig. S2). The length of time window related with the strongest association varied by outcome, generally ranging from half a year to a year, except for neoplasms and Alzheimer’s disease, which were two to three months. In the other sensitivity analyses varying the fixed-effect terms, truncating the propensity scores, laying restrictions on the affected areas of exposed counties (i.e., excluding counties with ≤ 20%, 40%, 60%, or 80% of the county area being affected by zonal floods), or restricting the time period, the point estimates and variances were similar to those from the primary analyses (Figs S3–6).

Discussion

All-cause deaths increased during the post-flood year, which resulted in over twenty-two thousand attributable deaths in the contiguous U.S. during 2001-2020, far exceeding the immediate deaths reported by the U.S. Billion-Dollar Disasters database. Elevated mortality was primarily due to respiratory diseases, external causes, and specific subcategories of circulatory diseases (i.e., ischemic heart diseases, cerebrovascular diseases). In contrast, there were decreased deaths due to dementia and hypertensive diseases (contributed by hypertensive heart disease). We found differential associations by flood type and among sub-populations by age, sex, race, and ethnicity.

This study adds to the current literature regarding the prolonged and indirect health impacts from floods, covering diverse causes of death. To date, few epidemiological studies have evaluated the long-term associations between floods and mortality. We observed associations in the same direction as the multi-country multi-city study during the two months after floods for all-cause, cardiovascular, and respiratory deaths, while that study did not evaluate other causes and longer time windows for an in-depth comparison9. A recent difference-in-differences analysis examined the association between seven billion-dollar flood disasters or five billion-dollar flood/severe storm disasters in the U.S. during 2011-2016 and mortality among Medicare beneficiaries (a population predominantly aged 65 years and older), finding no significant changes in the mortality rate in the weeks after the disasters16. This nonsignificant finding on mortality rate may be due to the differences in their focus on billion-dollar weather disasters (either floods or floods/severe storms) rather than all flood events, examining Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries rather than all age groups, and the relatively short lag period (up to six weeks, compared with 12 months in our study) after flood disasters.

Biologically in the long run, floods may cause emotional stress (e.g., due to loss of relatives and friends and resettlement) and shifts in lifestyle behaviors (e.g., sleep disorders and changes in exercise and dietary patterns), which would cause body dysregulation and disturb the human body’s homeostasis, increasing the risk for multiple diseases, including circulatory diseases6,17,18. Furthermore, the dampness and mold growth in the flood-affected houses may last for months or even over one year19, leading to increased risks for respiratory diseases20,21, neurological disorders22,23, circulatory system diseases24,25, and liver and kidney damage26,27. Besides these direct pathways, floods usually cause secondary disasters, including disruption of medical services, power outages, disruption of transportation, and lack of daily necessities (including food, clothes, shelters, and personal care supplies) and other social supplies (including sanitation and hygiene systems)5,28, which would limit the accessibility to health care services, decrease quality of life, and increase vulnerability, thereby indirectly leading to hastened fatalities. In other words, floods add to the health burden possibly due to exposure and increased vulnerability. However, these indirect pathways may not explain why certain diseases (e.g., the circulation and respiratory systems) were more likely to be associated with increased mortality risk after flood events. Further research is warranted to advance our understanding of the underlying biological, social, and behavioral mechanisms for different mortality causes.

The decreased deaths due to specific causes of death may appear puzzling, but several potential reasons may account for these findings. First, these associations might be false by chance or due to shifts in disease screening and diagnosis process. Emergencies like floods limit access to routine medical services (e.g., blood pressure tests), postponing or canceling physical exams and preventive care, which in turn delays or misses diagnoses after the onset of early symptoms29,30. Second, there could be mortality displacement across outcomes due to competing risks31,32. For example, an individual with undiagnosed glioma may have severe brain hemorrhage and have their death attributed to cerebrovascular diseases. Third, hypertension might have been listed as a contributing cause, instead of a primary cause, leading to underreporting and misclassification of hypertensive diseases in death certificates, which might be exacerbated by floods due to limited access to routine medical services33. Lastly, these associations could be real due to emergency actions after floods and more attention paid to individuals in flooded areas (e.g., post-flood mobilization of social support)34.

Regarding stronger associations with flash floods, suddenness, intensity, timing, and locations could be the reasons based on hydrometeorological evidence35,36,37. However, with no long-term epidemiological evidence on flash floods, we are unable to confer a more comprehensive discussion.

We observed vulnerability for all-cause or non-external deaths among individuals ≥65 years and females, and vulnerability for external causes among individuals ≥65 years, males and Hispanic White populations. Using aggregated demographic information on the city-level, Yang et al. did not observe any vulnerability among the older population regarding all-cause and cardiovascular mortality during the two months after floods9. Similarly, we did not observe heterogeneity across age groups for circulatory mortality during the post-flood year but found higher risk among older individuals for all-cause mortality. On the opposite end, Milojevic et al. found no evidence for heterogeneous flood-related effects on all-cause mortality by age or sex in the post-flood year in England and Wales or by age during the three years after flooding in rural Bangladesh11,12. The vulnerability among older populations may be due the relatively higher prevalence of chronic conditions and more fragile body homeostasis. However, it is unclear why females may be more vulnerable to non-external deaths when compared to males, although they may be more likely to have more severe psychological distress after disasters38,39 and to remain indoors to take care of children and older dependents40, whereas males may be more vulnerable to external deaths due to a higher likelihood of being outdoors or in occupational circumstances with higher risk for external injuries41,42. Preliminary U.S. flood fatality statistics showed that 64% of the direct flood fatalities were from male in the U.S. from 2010 to 2020, which counted deaths like drowns due to floods flipping over the vehicles15,43. However, considering the scarce evidence, these findings should be interpreted with caution and with consideration of the study context, whereas they may alert targeted health management in different populations after floods and call for further research on potential disparities and mechanisms.

The findings of this study have important implications for understanding the impact of floods on cause-specific mortality in the U.S., offering critical insights for public health planning and disaster preparedness. Even with a seemingly small magnitude of effect (i.e., approximately 8 excess deaths per 10 million individuals in the year following one flood day), floods have caused considerable health burden (more than twenty-two thousand attributable deaths; similar to the number of unintentional injury deaths in 2022) in aggregate across the contiguous U.S. over our study period. Such a number is much greater than the direct deaths (n = 266) due to floods from heavy rainfall reported in the U.S. Billion-Dollar Disasters database, even if we additionally counted all the deaths due to severe storms (n = 1234) and tropical cyclones (n = 6096) by assuming 100% of their attribution to accompanied inland floods (which is nearly impossible)1. However, the U.S. Billion-Dollar Disasters database only included the most severe events, overlooking the life loss in milder flood events. Furthermore, the National Weather Service preliminarily reported a total of 1062 direct flood fatalities from 2010 to 2020, which does not count indirect fatalities and is still considerably smaller than our estimate43. Our flood-related attribution analysis underscores the prolonged and indirect impacts of floods and the urgency of mitigation strategies against floods, not only the most severe ones. The impacts will likely become more substantial with more floods due to climate change. Our findings across spectrum of causes and subpopulations may inform the allocation of health care resources after floods. Beyond mortality, which is a limited measure of health impact, further research on the morbidity burden of floods is warranted.

Beyond above findings and implications, this study also adds to the current literature from the aspect of methodology that we proposed a triply robust approach to incorporate causal inference ideas. Due to the “pulse” and relatively “rare” nature of extreme events like floods, traditional methods were unstable and sensitive in our exploratory analyses. In the context of climate change, more frequent and more severe extreme events (e.g., tornado outbreak in Midwestern and South-Central U.S. in April 2024) are raising the public concern and interest. Our method is generalizable for further analysis of extreme events.

There are limitations to our study. First, we do not have information on the objective severity of the floods, which might influence the magnitude of the association. The partially subjective nature of the storm data may lead to confounding and exposure misclassification. Both the local report of flood events and the death counts are affected by the location and the timestamp of events, causing spatial and temporal confounding. However, confounding was controlled by including spatial and temporal fixed-effect terms in the propensity-score and control-outcome models. On the other hand, the exposure misclassification due to local subjective reports would make the control and treatment groups more similar, thus biasing the associations towards the null. Second, we do not have information on population displacement after floods. However, population mixing due to displacement between flooded and non-flooded areas would bias the associations towards the null. To reduce exposure misclassification, we have restricted analyses to individuals whose county of death was their residential county. Third, our analysis did not include coastal floods associated with tropical storms. Therefore, our estimates of flood-related health burdens should be interpreted with caution regarding the definition of floods. Finally, we could not rule out the possibility that our findings were positive or negative by chance. Further research using different exposure assessment methods, based on different locations, or utilizing different statistical approaches is warranted.

During the year after floods, there were excess all-cause deaths in aggregate. From 2001 to 2020, over twenty-two thousand deaths in the contiguous U.S. were attributable to floods, substantially surpassing officially reported estimates. These findings highlight the health risks of floods and underscore the need for prolonged efforts to support individuals impacted by floods beyond the initial emergency management. As the totality of knowledge about the health impacts of floods is still limited, more systemic research is needed to enable effective adaptation strategies under the backdrop of climate change.

Methods

Study settings and main outcomes

This study covered all 3103 county-equivalent areas (hereinafter referred to as counties) throughout the contiguous U.S.44. We harmonized the county boundaries from 2000 to 2020, taking into account the historical changes in cartographic boundaries. We obtained monthly death records by county (with individual-level demographic information) from the National Center for Health Statistics (2000–2020) and yearly county-level population data by age group from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, National Cancer Institute45. We then calculated county-level age-standardized mortality rates using the 2000 U.S. standard population14. Hereinafter, mortality rates are age-standardized and reported per 10 million individuals.

We focused on 23 disease categories (Table 1). All-cause deaths included non-external and external causes, and non-external deaths were further classified into certain infectious and parasitic diseases, mental and behavioral disorders, diseases of the circulatory system, etc. Specific subcategories were also evaluated, like dementia and myocardial infarction. Other categories were not assessed considering sample sizes. See the screening process in Figure S1.

The Institutional Review Board of Yale University determined that this study does not involve human subjects (ID: 2000036520).

Exposure assessment

We extracted flood events during 2000–2020 defined by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Storm Events Database15, along with their occurrence county/zone and the starting and end dates. The database included all the flood events (excluding coastal floods associated with tropical storms [e.g., hurricane]) with sufficient intensity to result in financial loss, property damage, injuries, or fatalities, incorporating information from both objective measures (e.g., overflow volume and duration information from monitors and emergency management officials) and local media (e.g., newspaper). More details on the definition of floods were in Text S1. For the floods coded as county events, we directly converted the event-level data into county-level monthly count of flood days. For the floods coded as zonal events, we used the NOAA county-forecast zone correlation table to locate the affected counties, calculated the percentage of the county area being affected based on the zone boundaries defined by NOAA, and then counted county-level monthly flood days. In the main analysis, we had no restriction on the size of affected area for a county to be considered as exposed; while in the sensitivity analysis, we only included counties affected by county-level floods and counties with >20%, 40%, 60%, or 80% of the county area being affected by zonal floods. We also calculated county-level monthly temperature, precipitation, and snow from the Daymet dataset46.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were based on 2001 to 2020 (with year 2000 excluded due to incomplete exposure records). We applied a triply robust approach (Fig. 1) using moving averages of monthly count of flood days in the post-flood year: (1) We assigned county-month observations into treatment/control groups based on the presence/absence of flood days in a 12-month timespan (i.e., 0–11 months prior to the death record; in other words, we were assuming that the affected counties had fully recovered from floods after one year)47, and estimated propensity scores of being treatment/control (named “propensity-score model”). The timespan of 12 months was selected based on our preliminary results that cause-specific associations generally would not extend over 12 months (for example, the association with all-cause mortality reached the highest magnitude approximately at lag 0–10 months [Fig. S2]) and in consideration of seasonality. Counties could switch between the treatment and control groups; such a crossover ensures better information sharing between groups. (2) With inverse-probability weights based on propensity scores, we regressed age-standardized death counts on covariates (specified below) in the control group using a quasi-Poisson regression (named “control-outcome model”). Using the fitted control-outcome model, we estimated counterfactual outcomes in the treatment group had floods not occurred. (3) In the treatment group, we regressed the residual mortality rate (i.e., the observed minus the counterfactual) on the flood exposure (named “treatment-outcome model”), weighted by the inverse-probability weights calculated from propensity scores. We interpreted the flood coefficient as the excess mortality rate per additional monthly flood day.

In all models, we controlled for meteorological factors including monthly temperature, precipitation, and snow in that county and averaged precipitation and flood days in the surrounding counties (i.e., the other counties in the same state)48. Because heavy precipitation is a main cause of flooding and can result in increased mortality risks independent of flooding49,50, precipitation is considered as a confounder in this analysis examining the association between flooding and mortality. In the propensity-score and the control-outcome models, we included fixed-effect terms for counties, combinations of calendar year and month of year, and combinations of state and calendar year to control for spatial, temporal, and spatial-temporal confounding, respectively. More details on the selection of covariates and confounding issues were in Text S1.

Specifically, we used logistic regression for the propensity-score model as shown below,

where\({{\rm{tr}}}{{{\rm{eatment}}}/{{\rm{control\; status}}}}_{{{\rm{c}}},{{\rm{a}}},{{\rm{m}}}}\) is the treatment/control status of county \(c\), on month \(m\) of year \(a\),\(p\) is the probability of being in the treatment group,\({\alpha }_{c}\) is the fixed-effect term for counties,\({\alpha }_{s,a}\) is the fixed-effect term for the combinations of state and calendar year,\({\alpha }_{a,m}\) is the fixed-effect term for the combinations of calendar year and month of year,and \({{\rm{f}}}({{\rm{covariate}}}{{{\rm{s}}}}_{{{\rm{c}}},{{\rm{a}}},{{\rm{m}}}})\) controls for covariates, including monthly temperature, precipitation, and snow in the county itself and averaged precipitation and flood days in the surrounding counties (defined as the other counties in the same state).

We fitted the control-outcome model using a quasi-Poisson regression in the control group weighted by the inverse-probability weights based on propensity scores calculated from the propensity-score model.

Where \({Y}_{c,{a},{m}}\) is the age-adjusted monthly death count in county \(c\), on month \(m\) of year \(a\), and \({{\rm{populatio}}}{{{\rm{n}}}}_{{{\rm{c}}},{{\rm{a}}}}\) is the total population in county \(c\) in year \(a\).

We fitted the treatment-outcome model in the treatment group weighted by the inverse-probability weights based on propensity scores calculated from the propensity-score model.

where\({{\rm{rat}}}{{{\rm{e}}}}_{{{\rm{c}}},{{\rm{a}}},{{\rm{m}}}}\) is the age-adjusted monthly residual mortality rate in county \(c\), on month \(m\) of year \(a\) (i.e., \(({Y}_{{1}_{c,{a},{m}}}-{\hat{Y}}_{{0}_{c,{a},{m}}})/{{\rm{populatio}}}{{{\rm{n}}}}_{{{\rm{c}}},{{\rm{a}}},{{\rm{m}}}}\)),\({\hat{Y}}_{{0}_{c,{a},{m}}}\) is the predicted counterfactual death count had floods not happened by plugging values of covariates in the treatment group into the control-outcome model,\({\alpha }_{0}\) is the intercept,\({\beta }_{1}\) is the coefficient for the moving averages of monthly counts of flooding days in county \(c\), on month \(m\) of year \(a\) (\({{\rm{floo}}}{{{\rm{d}}}}_{{{\rm{c}}},{{\rm{a}}},{{\rm{m}}}}\)),and \({{\rm{f}}}({{\rm{covariate}}}{{{\rm{s}}}}_{{{\rm{c}}},{{\rm{a}}},{{\rm{m}}}})\) controls for other covariates (same as those in the propensity-score model excluding the fixed-effect terms).

Stratified analyses by potential effect modifiers

To account for differences in flood severity, we conducted a stratified analysis by flood type (flash floods versus non-flash floods). Other flood types (i.e., coastal floods, lakeshore floods, and debris flows) were not evaluated due to small sample sizes (Table S1).

We also assessed different subgroups by age (0–64 years, ≥65 years; no finer categorization considering the sample distribution by age), sex (male, female), race, and ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic White populations [others were excluded considering sample sizes]) for all-cause, non-external, neoplasms, circulatory diseases, and external causes (Table S2). Other causes were not assessed due to sample sizes. We used the Q-statistic and the corresponding p-value to describe inter-group heterogeneities.

Considering the large number of flood events and of affected populations and assuming causality on our estimates, we calculated deaths attributable to floods by summing the county-month-specific attributable deaths (i.e., the excess mortality rate per flood day × average monthly flood days × population) over counties in the contiguous U.S. and months from 2001-2020.

Sensitivity analyses

We conducted several sensitivity analyses to evaluate the robustness of our primary results: (1) varying the time window: in the main analysis, lag 0–11 months were used (e.g., the exposure for a death occurring on May 2024 would be the flood exposure from June 2023 to May 2024); (2) varying the fixed-effect terms to evaluate the potential location-dependent seasonality; (3) addressing outliers in inverse-probability weights; (4) for zonal floods, only including counties with > 20%, 40%, 60%, or 80% of the county area being affected; and (5) excluding 2020 data which was like influenced by the COVID-19.

All statistical analyses were conducted in R-4.2.0. The fixed-effect regression in the propensity-score models and the control-outcome models was fitted using R package “fixest” (version 0.11.1). We interpreted p < 0.05 as statistically significant and reported findings according to the STROBE guidelines. Codes are available at https://github.com/CHENlab-Yale/Flood_mortality_US (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14888416)51.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The monthly county-level cause-specific mortality data are protected and are not publicly available due to data privacy laws, but can be requested from the National Center for Health Statistics (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/index.htm). The raw flood data are available in the NOAA Storm Events Database (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/stormevents/). The population data are available from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program, National Cancer Institute (https://seer.cancer.gov/data-software/uspopulations.html).

Code availability

R code for this analysis will be available at: https://github.com/CHENlab-Yale/Flood_mortality_US (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14888416).

References

Smith A. B. U.S. Billion-dollar Weather and Climate Disasters, 1980 - present (NCEI Accession 0209268). In: NOAA_National_Centers_for_Environmental_Information, ed.: NOAA_National_Centers_for_Environmental_Information; 2020.

Hirabayashi, Y. et al. Global flood risk under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 816–821 (2013).

Rentschler, J. et al. Global evidence of rapid urban growth in flood zones since 1985. Nature 622, 87–92 (2023).

Smith A. B. 2010–2019: A landmark decade of US. billion-dollar weather and climate disasters. National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration 2020.

The_Lancet_Respiratory_Medicine. Flooding and excessive rainfall risk respiratory health [Editorial]. Lancet Respir. Med. 12, 89 (2024).

Turner, A. I. et al. Psychological stress reactivity and future health and disease outcomes: A systematic review of prospective evidence. Psychoneuroendocrinology 114, 104599 (2020).

Klinger, C., Landeg, O. & Murray, V. Power outages, extreme events and health: A systematic review of the literature from 2011–2012. PLoS Curr. 6, 6 (2014).

Romanello, M. et al. The 2022 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: health at the mercy of fossil fuels. Lancet 400, 1619–1654 (2022).

Yang, Z. et al. Mortality risks associated with floods in 761 communities worldwide: time series study. BMJ (Clin. Res. ed.) 383, e075081–e075081 (2023).

Obrová, J., Sovová, E., Ivanová, K., Táborský, M. & Loyka, S. Effects of the July 1997 Floods in the Czech Republic on Cardiac Mortality. Disaster Med. Public Health Preparedness 8, 492–496 (2014).

Milojevic, A. et al. Long-term effects of flooding on mortality in England and Wales, 1994–2005: controlled interrupted time-series analysis. Environ. Health.: a Glob. access Sci. source 10, 11–11 (2011).

Milojevic, A. et al. Health effects of flooding in Rural Bangladesh. Epidemiology 23, 107–115 (2012).

Bennet, G. Bristol floods 1968. Controlled survey of effects on health of local community disaster. Br. Med. J. 3, 454–458 (1970).

NcicancerStats. Standard Populations (Millions) for Age-Adjustment - SEER Population Datasets. @NCICancerStats; 2024.

NOAA. Storm Events Database. 2023.

Salas, R. N. et al. Impact of extreme weather events on healthcare utilization and mortality in the United States. Nat. Med. 30, 1118–1126 (2024).

Steptoe, A. & Kivimäki, M. Stress and cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 9, 360–370 (2012).

Yazawa, A. et al. Post-disaster mental health and dietary patterns among older survivors of an earthquake and tsunami. J. Nutr., health aging 27, 124–133 (2023).

Hasegawa, K. et al. Indoor environmental problems and health status in water-damaged homes due to tsunami disaster in Japan. Build. Environ. 93, 24–34 (2015).

Mendell, M. J., Mirer, A. G., Cheung, K., Tong, M. & Douwes, J. Respiratory and allergic health effects of dampness, mold, and dampness-related agents: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. Environ. Health Perspect. 119, 748–756 (2011).

Ban, J., Sutton, C., Ma, Y., Lin, C. & Chen, K. Association of flooding exposure with cause-specific mortality in North Carolina, United States. Nat. Water 1, 8 (2023).

Ehsanifar, M., Rajati, R., Gholami, A. & Reiss, J. P. Mold and mycotoxin exposure and brain disorders. J. Integr. Neurosci. 22, 137 (2023).

Vasefi, M., Ghaboolian-Zare, E., Abedelwahab, H. & Osu, A. Environmental toxins and Alzheimer’s disease progression. Neurochem. Int. 141, 104852 (2020).

Carvajal-Moreno, M. Mycotoxins that affect the human cardiovascular system. Biomol. Res. Ther. 4, 2 (2015).

Wang, K., Liu, S., Zhang, X. & Sun, D. Toxic effect of mycotoxins on cardiovascular system: A topic worthy of further study. Food Rev. Int. 39, 2203–2211 (2023).

Wangikar, P. B., Dwivedi, P., Sinha, N., Sharma, A. K. & Telang, A. G. Teratogenic effects in rabbits of simultaneous exposure to ochratoxin A and aflatoxin B1 with special reference to microscopic effects. Toxicology 215, 37–47 (2005).

M. Mohamed, A. & S. Metwall, N. Antiaflatoxigenic activities of some plant aqueous extracts against aflatoxin-B1 induced renal and cardiac damage. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 4, 1–16 (2008).

Merz, B., Kreibich, H., Schwarze, R. & Thieken, A. Review article” Assessment of economic flood damage. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 10, 1697–1724 (2010).

Miki, Y., Tase, T., Tokunaga, H., Yaegashi, N. & Ito, K. Cervical cancer screening rates before and after the Great East Japan Earthquake in the Miyagi Prefecture, Japan. PLoS One 15, e0229924 (2020).

Saito, H. et al. The long term participation trend for the colorectal cancer screening after the 2011 triple disaster in Minamisoma City, Fukushima, Japan. Sci. Rep. 11, 23851 (2021).

Harvey, L., Mitchell, R., Brodaty, H., Draper, B. & Close, J. The influence of dementia on injury-related hospitalisations and outcomes in older adults. Injury 47, 226–234 (2016).

Collaborators, G. et al. Global mortality from dementia: Application of a new method and results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Alzheimer’s. Dement.: Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 7, e12200 (2021).

Habibisaravi, R. et al. Flood and hypertension: A systematic review. Res. Cardiovascular Med. 11, 1–5 (2022).

Kaniasty, K. & Norris, F. H. Distinctions that matter: Received social support, perceived social support, and social embeddedness after disasters. Ment. health disasters 2009, 175–200 (2009).

Diakakis M. et al. How different surrounding environments influence the characteristics of flash flood‐mortality: The case of the 2017 extreme flood in Mandra, Greece. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2020;13. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12613.

Ruin, I., Creutin, J.-D., Anquetin, S. & Lutoff, C. Human exposure to flash floods – Relation between flood parameters and human vulnerability during a storm of September 2002 in Southern France. J. Hydrol. 361, 199–213 (2008).

Liu, T., Wang, Y., Yu, H. & Chen, Y. Using statistical functions and hydro-hydraulic models to develop human vulnerability curves for flash floods: The flash flood of the Taitou catchment (China) in 2016. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 73, 102876 (2022).

Goldmann, E. & Galea, S. Mental health consequences of disasters. Annu. Rev. public health 35, 169–183 (2014).

Yazawa, A., Aida, J., Kondo, K. & Kawachi, I. Gender differences in risk of posttraumatic stress symptoms after disaster among older people: Differential exposure or differential vulnerability? J. Affect. Disord. 297, 447–454 (2022).

Rahman, M. S. Climate change, disaster and gender vulnerability: A study on two divisions of Bangladesh. Am. J. Hum. Ecol. 2, 72–82 (2013).

Fothergill, A. The neglect of gender in disaster work: An overview of the literature. International Journal of Mass Emergencies & Disasters 14, 33–56 (1996).

Sorenson, S. B. Gender disparities in injury mortality: consistent, persistent, and larger than you’d think. Am. J. public health 101, S353–S358 (2011).

Us Department of Commerce NNWS, National Weather S. NWS Preliminary US Flood Fatality Statistics. NOAA’s National Weather Service, October 30th 2024 7:28 PM 2024. (https://www.weather.gov/arx/usflood).

Ma, Y. et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in PM2. 5-attributable cardiovascular mortality burden in the United States. Nat. Human Behav. 7, 2074–2083 (2023).

The_SEER_Program. U.S. County Population Data - 1969-2020. 2022.

Thornton M. M. et al. Daymet: Daily Surface Weather Data on a 1-km Grid for North America, Version 4 R1. ORNL Distributed Active Archive Center; 2022.

Liu, L., Wang, Y. & Xu, Y. A practical guide to counterfactual estimators for causal inference with time‐series cross‐sectional data. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 68, 160–176 (2022).

Oskorouchi, H. R. & Sousa‐Poza, A. Floods, food security, and coping strategies: Evidence from Afghanistan. Agric. Econ. 52, 123–140 (2021).

Chan, K., Ban, J., Ma, Y. & Chen, K. Association of exposure to extreme rainfall events with cause-specific mortality in North Carolina, US. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 044006 (2024).

He, C. et al. Rainfall events and daily mortality across 645 global locations: two stage time series analysis. BMJ 387, e080944 (2024).

Chu, L. et al. Floods and cause-specific mortality in the United States applying a triply robust approach. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14888416.

Acknowledgements

Funding/Support Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HL169171 (K.C.). Role of the Funder/Sponsor The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.C. and K.C. designed the study and led the methodology development. L.C., K.C., and J.W. performed the statistical analysis. All authors interpreted the results. L.C. and K.C. drafted the manuscript. J.W., E.S., S.L., Y.L., X.M., J.R., and H.K. edited and reviewed the manuscript. K.C. obtained funding.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

E.S.S. reported receiving grants from the US Food and Drug Administration to support projects within the Yale University–Mayo Clinic Center of Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation and from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, all for work unrelated to this study. S.L. reported receiving funding through an early career fellowship from the Gulf Research Program of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Y.L. reported receiving grants from the Sentara Research Foundation; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health; and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute outside of the submitted work. X.M. consulted for Bristol Myers Squibb outside the submitted work. J.S.R. reported grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ, R01HS022882) during the conduct of the study; grants from the US Food and Drug Administration, Johnson & Johnson, Medical Devices Innovation Consortium, grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NIH/NHLBI), and Arnold Ventures outside the submitted work; and serving as an expert witness at the request of Relator’s attorneys, the Greene Law Firm, in a qui tam suit alleging violations of the False Claims Act and Anti-Kickback Statute against Biogen Inc that was settled September 2022. H.M.K. received personal fees from Element Science, Identifeye, and F-Prime; is a co-founder of Hugo Health, Refactor Health, and ENSIGHT-AI; was the editor of Journal Watch and is a section editor of UpToDate; and is associated with contracts, through Yale New Haven Hospital, from the US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and through Yale University from Janssen, Johnson & Johnson Consumer, and Pfizer. K.C. has received grant funding from the Health Effects Institute and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. No other disclosures were reported. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chu, L., Warren, J.L., Spatz, E.S. et al. Floods and cause-specific mortality in the United States applying a triply robust approach. Nat Commun 16, 2853 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58236-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58236-0

This article is cited by

-

Prolonged health risks following floods

Nature Water (2025)