Abstract

Conventional alloying strategies often require high alloying concentrations, leading to impurity phases and additional phase transition that limit the figure of merit of thermoelectric materials. Here, we introduce metavalent alloying and vacancy engineering as transformative strategies to facilitate the orthorhombic-to-cubic phase transition, in which we stabilize pure cubic GeSe under ambient conditions with just 10% alloying concentration using Sb2Te3 as an effective alloying agent. Compared to the covalently bonded orthorhombic phase, the metavalently bonded cubic GeSe features lower cation vacancy formation energy, reduced bandgap, enhanced band degeneracy, weaker chemical bonding, stronger lattice anharmonicity, and multiple phonon scattering centers. These properties synergistically improve the power factor and suppress the lattice thermal conductivity. Subsequent trace Pb doping further reduces the lattice thermal conductivity, achieving an unprecedented ZT of 1.38 at 723 K in cubic (Ge0.95Pb0.05Se)0.9(Sb2Te3)0.1, along with a remarkable energy conversion efficiency of 6.13% under a 430 K temperature difference. These results advance the practical application of GeSe-based alloys for medium-temperature power generation and provide critical insights into the orthorhombic-to-cubic phase transition mechanism in chalcogenides.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Thermoelectric energy conversion technology is crucial for addressing the global energy crisis by efficiently converting low-grade thermal energy into valuable electrical energy1,2,3,4,5. The energy conversion efficiency (η) of thermoelectric devices is governed by the dimensionless figure of merit, ZT = S2σT/κ, where σ, S, κ, and T represent the electrical conductivity, Seebeck coefficient, thermal conductivity (comprising both carrier κe and lattice κL contributions), and absolute temperature, respectively6,7,8. Enhancing thermoelectric performance typically involves band engineering9,10 and phonon engineering11,12,13. Band engineering focuses on optimizing the electronic band structure, such as through band convergence14, band anisotropy15, or the introduction of resonant energy levels16,17, to improve the power factor (S2σ). In contrast, phonon engineering aims to reduce the κL by lowering the sound velocity (vm) or introducing multi-scale defects to shorten the phonon mean free path18,19.

Recent advancements have brought layered orthorhombic SnSe into the spotlight due to its unparalleled ZT values20,21. Similarly, GeSe, another IV-VI group semiconductor, has emerged as a promising candidate for medium-temperature thermoelectric applications22,23. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations predict that optimally doped orthorhombic GeSe could achieve a peak ZT of 2.5 along the b-axis at 800 K22. However, the limited solubility of dopants in orthorhombic GeSe restricts the effective carrier concentration (nH), leading to a low ZT of approximately 0.224. In contrast, transitioning to rhombohedral or cubic GeSe has demonstrated significantly enhanced ZT, driven by its unique metavalent bonding (MVB) mechanism25,26,27. Unlike the conventional covalent bonding (CVB) in orthorhombic GeSe where two electrons are shared28,29, resulting in a bond order of 1, MVB involves the sharing of approximately one electron between neighboring atoms, yielding a bond order of ~1/2. This bonding type, distinct from covalent, ionic, and metallic bonds, endows MVB solids with exceptional properties for carrier and phonon transport28,30. Electrically, compared to its covalently bonded orthorhombic counterpart, metavalently bonded rhombohedral or cubic GeSe exhibits a reduced bandgap (Eg), lower Ge vacancy formation energy, narrower band edges, and greater band degeneracy (NV). Thermally, it demonstrates a lower vm and stronger lattice anharmonicity. These factors collectively contribute to the enhanced ZT value observed in metavalently bonded GeSe31.

Current research on high-performance p-type GeSe primarily focuses on its rhombohedral phase32. Significant advancements, such as Sb-Cd co-doping33 and alloying with compounds like InTe34, CdTe27, MnCdTe235, AgInTe236, LiBiTe237, and Ag(Sb, Bi)(Se, Te)226,38,39,40,41, have successfully transformed orthorhombic GeSe into the rhombohedral structure, achieving ZT values ranging from 0.90 to 1.3626,27,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41. However, cubic GeSe, which is unaffected by Peierls distortion, offers larger band degeneracy, lower vm and greater lattice anharmonicity25, theoretically surpassing thermoelectric performance of the rhombohedral phase. Additionally, the phase transition from orthorhombic (or rhombohedral) to cubic at elevated temperatures causes a significant change in the coefficient of thermal expansion, leading to internal stresses that can damage the materials or disrupt the material-electrode interfaces. This, in turn, compromises the long-term reliability of thermoelectric devices. Therefore, facilitating the orthorhombic-to-cubic phase transition and stabilizing the cubic phase across the entire temperature range hold both theoretical and practical importance.

Understanding the mechanisms driving the orthorhombic-to-cubic phase transition in chalcogenides is therefore critical. In these materials, the orthorhombic structure exhibits strong Peierls distortion, characterized by high electron sharing (ES) between neighboring atoms, while the cubic structure, free from such distortion, displays minimal ES due to the absence of s- and p-band hybridization28. By chemically or physically suppressing Peierls distortion (effectively reducing the ES capacity between neighboring atoms), the bonding can be transitioned from CVB to MVB, enabling the progression of GeSe from the orthorhombic to the rhombohedral, and ultimately, to the cubic phase28,29. Strategic alloying of GeSe with compounds such as InSnTe2 and AgSnTe2 has been explored to facilitate this phase transition42,43. However, limited solubility in these alloys has hindered the complete elimination of residual orthorhombic phases and the prevention of secondary phase precipitation, presenting challenges to achieving fully cubic GeSe.

Previous studies have investigated the critical role of chemical bonding mechanism in governing dopant solubility. High miscibility is achieved when both the host material and the dopant share the same MVB mechanism, as demonstrated in systems like SnTe-AgSbTe244 and GeTe-PbSe-PbS45. In contrast, mixing metavalent compounds with covalent solids often leads to phase separation, as observed in the GeTe-GeSe-GeS system46. Consequently, MVB compounds, such as IV-VI, V2VI3, and I-V-VI2, exhibit excellent solubility in GeSe, minimizing residual orthorhombic or precipitated phases (Fig. 1a). However, alloying cubic GeSe with IV-VI or I-V-VI2 compounds typically requires extremely high alloying concentrations, which can negatively impact μH and, consequently, the ZT value. For example, stabilizing cubic GeSe through I-V-VI2 alloying necessitates at a minimum of 30% content, significantly lowering the ZT compared to rhombohedral GeSe38,43,47. Quantum chemical calculations and enthalpy of formation analyzes reveal that cation vacancies destabilize covalently bonded orthorhombic GeSe48, but are essential for mitigating unfavorable anti-bonding Ge-Se interactions in metavalently bonded rhombohedral or cubic GeSe49. This suggests that the introduction of cation vacancies is critical for stabilizing high-symmetry phases (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, DFT calculations and X-ray diffraction (XRD) studies indicate that the concentration of Ge vacancies in cubic GeTe is significantly higher than in its rhombohedral counterpart50. These findings imply that alloying with V2VI3 compounds, which offer high solubility and additional cation vacancies, can accelerate the orthorhombic-to-cubic phase transition in chalcogenides, potentially bypassing the intermediate rhombohedral phase.

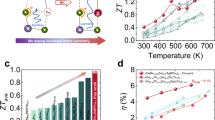

a Illustration of design strategy for cubic GeSe: metavalent V2VI3 alloying with high solid solubility and additional cation vacancy49. Here Orth. refers to the orthorhombic structure, while Rhom. represents the rhombohedral structure. b Alloying content (x) and configurational entropy (ΔS) required for obtaining cubic GeSe studied herein in comparison with literature data26,38,43,47 (the bar chart corresponds to x and the red line represents ΔS). c Comparison of peak ZT of this work and reported works24,26,33,34,35,36,37,38,40,41,42,43,64. d Energy conversion efficiency (η) of single-leg GeSe-based device under various temperature differences (∆T) in comparison with literature data36.

Results and discussion

According to the Hume-Rothery rules51, the atomic size mismatch between Ge and Bi is significantly larger compared to that between Ge and Sb, resulting in a higher solubility of Sb2Te3 in GeSe than Bi2Te3 (Supplementary Fig. 1). Based on this principle, we introduced a small amount (> 7.5%) of metavalent Sb2Te3 as an alloying agent to accelerate the stabilization of cubic GeSe (Fig. 1b). Compared to orthorhombic GeSe, cubic GeSe exhibits optimized nH, enhanced μH, and a higher density-of-states effective mass (m*), leading to a significant improvement in the S2σ. Additionally, the weakened chemical bonding and enhanced lattice anharmonicity in cubic (GeSe)1−x(Sb2Te3)x, combined with multiple phonon scattering mechanisms, effectively reduce the κL. To further minimize κL, trace amounts of Pb was doped into (GeSe)0.9(Sb2Te3)0.1, achieving a record-breaking ZT = 1.38 at 723 K in cubic (Ge0.95Pb0.05Se)0.9(Sb2Te3)0.1. The single-leg device demonstrated an impressive η of 6.13% under a ΔT of 430 K (Fig. 1c, d). These results not only represent a significant breakthrough in the ZT of cubic GeSe but also provide valuable insights into the key factors driving the orthorhombic-to-cubic phase transition in chalcogenides.

To determine whether the integration of non-stoichiometric metavalent Sb2Te3 can accelerate the stabilization of cubic GeSe, powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) was performed on the full series of (Ge1−yPbySe)1−x(Sb2Te3)x samples (x = 0 ~ 15%, y = 3 ~ 7%). As shown in Fig. 2a, the room-temperature XRD patterns reveal significant structural changes in GeSe with increasing Sb2Te3 content (x). The initial sample with x = 0 exhibited diffraction peaks characteristic of the typical orthorhombic structure (Pnma). After alloying with Sb2Te3, the intensity of the orthorhombic phase peaks between 30° and 33° decreased significantly, while the intensity at 31.3° increased, indicating the formation of a cubic phase (Fm-3m). This suggests the coexistence of cubic and orthorhombic phases in the sample with x = 0.05. When the Sb2Te3 content increased to x ≥ 0.075, a predominantly cubic structure was consistently observed in all samples at room temperature. Notably, further addition of trace Pb to the x = 0.10 sample had minimal impact on the phase structure, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

a Room-temperature powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns. Calculated b lattice parameters a, b, c and c bond distances. Here, 0.1% error bar is employed. Variable-temperature XRD patterns for d x = 0.075 and e x = 0.01 samples. f Calculated formation energy of Ge vacancy for orthorhombic GeSe, cubic GeSe, and cubic (GeSe)0.9(Sb2Te3)0.1. g Phase structure and vacancy concentration evolution upon Sb2Te3 alloying according to the XRD Rietveld refinement results.

To quantify the impact of Sb2Te3 alloying on the crystal structure of GeSe, structural refinement was conducted using the Fullprof Suite52, allowing precise determination of the lattice parameters for the (Ge1−yPbySe)1−x(Sb2Te3)x samples (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). Specifically, the x = 0 sample exhibited a purely orthorhombic phase. As x increased, the proportion of the orthorhombic phase decreased significantly, while the fraction of the cubic phase correspondingly increased. For instance, in the x = 0.05 sample, the ratio of cubic to orthorhombic phases was quantified as 55.84% to 44.16%. Interestingly, while the room-temperature XRD pattern of the x = 0.075 sample suggested no detectable orthorhombic phase, structural refinement revealed a residual orthorhombic fraction of 6.36%. Complete transformation to a 100% cubic phase was achieved at x = 0.10, emphasizing the critical requirement for Sb2Te3 content to exceed 7.5% to stabilize cubic GeSe at ambient conditions.

As shown in Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 5, the lattice parameters (a, b, and c) of both orthorhombic and cubic GeSe increase significantly with the rising values of x or y. This lattice expansion is attributed to the larger ionic radii of Sb (145 pm), Pb (175 pm), and Te (221 pm) compared to those of Ge (73 pm) and Se (198 pm), respectively53. More importantly, as shown in Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 6, the bond lengths in orthorhombic GeSe generally range from 2.52 to 2.61 Å, whereas those in cubic GeSe extend from 2.84 to 2.89 Å. Based on the phenomenological bond length-bond strength relationship, shorter bonds typically correspond to stronger interactions, while longer bonds tend to indicate weaker interactions. Thus, the elongation of bond lengths in the cubic structure signifies a weakening of chemical bonding. This reduction in bond strength leads to weaker atomic interactions, which in turn reduces the vm and significantly lowers the κL.

To assess the effect of Sb2Te3 alloying on phase stability at high temperatures, temperature-dependent XRD measurements were conducted on the x = 0.075 and x = 0.10 samples (Fig. 2d, e). Upon heating, trace orthorhombic phases were observed in both samples, consistent with thermodynamic predictions that the metastable cubic phase transitions to the more stable orthorhombic structure under thermal stress. Notably, the orthorhombic phase appears above 623 K in the x = 0.075 sample and above 673 K in the x = 0.10 sample. Furthermore, the intensity of the orthorhombic peaks is significantly weaker in the x = 0.10 sample, indicating better retention of the cubic structure at higher temperatures. While increasing the Sb2Te3 content could potentially suppress the formation of the orthorhombic phase at elevated temperatures, it would likely compromise the ZT value.

To validate whether metavalent Sb2Te3 alloying with additional cation vacancies can accelerate the formation of cubic GeSe, we compared the required alloying concentrations with conventional approaches (Fig. 1b). Traditional alloying to achieve a fully cubic structure typically demands a high alloying content, such as over 40% for AgSnTe243 and at least 30% for AgBiTe226, AgSbTe238, and AgBiSe247. In contrast, our study demonstrates that orthorhombic GeSe can successfully transition to a pure cubic phase with Sb2Te3 alloying concentrations as low as 10% or less. To further clarify the influence of different alloying types, we quantitatively evaluated the configurational entropy (ΔS) required for various cubic GeSe-based alloys using Boltzmann theory54: \(\Delta S=-R{\sum }_{i=1}^{n}{x}_{i}\,{{\mathrm{ln}}}\,{x}_{i}\), where R represents the gas constant, n denotes the number of element types, and xi specifies the mole fraction of the i-th element (Fig. 1b). Notably, alloying with AgSnTe2, AgBiTe2, and AgSbTe2 requires ΔS values exceeding the typical threshold for high-entropy alloys (ΔS = 1.50 R)55. In the case of Sb2Te3 alloying, the cubic structure becomes mostly stable at ΔS = 0.98 R and fully stable at ΔS = 1.21 R. Compared to existing literature, the observed alloying content and ΔS in this study are significantly reduced, highlighting the importance of understanding the key factors governing the orthorhombic-to-cubic phase transition in chalcogenides. This reduced requirement underscores the efficiency and practicality of using Sb2Te3 as an alloying agent to stabilize cubic GeSe.

The driving force for the formation of cubic (GeSe)1−x(Sb2Te3)x alloys was investigated through the theoretical calculations of Ge vacancy formation energy (EV). As shown in Fig. 2f, we simulated three different crystal structures, namely Ge31Se32 (Pnma), Ge26Se27 (Fm-3m), and Ge22Sb4Se21Te6 (Fm-3m), and calculated EV using DFT. Notably, EV decreased significantly from 0.99 eV for binary orthorhombic Ge31Se32 to 0.35 eV for binary cubic Ge26Se27. For cubic Ge22Sb4Se21Te6, EV was further reduced to 0.07 eV. Given that cubic GeSe typically requires extreme conditions, such as high temperatures (> 900 K) or high pressures (> 8 GPa)56,57, our results confirm that metavalent Sb2Te3 alloying can accelerate the formation of the cubic phase under ambient conditions by intentionally introducing cation vacancies. This highlights the role of Sb2Te3 in reducing vacancy formation energy, enabling the stabilization of cubic GeSe without the need for extreme synthesis conditions.

In addition to theoretical calculations, cation vacancy concentration can be quantitatively evaluated through XRD refinement by analyzing the atomic occupancy of cation sites52 (Fig. 2g). Ideally, the atomic occupancy of cation sites should be 100%; however, with increasing Sb2Te3 content (x), this occupancy gradually deviates from 100%, indicating a significant increase in cation vacancy concentration. For instance, the cation site occupancy decreased sharply from 100% in the x = 0 sample to 96.8% in the x = 0.10 sample and further dropped to 93.2% in the x = 0.15 sample. This trend demonstrates a direct correlation between the increasing Sb2Te3 alloying content and the generation of cation vacancies. In contrast, the addition of Pb to the x = 0.10 sample increases the cation site occupancy, thereby reducing the concentration of cation vacancies, as shown in Supplementary Table 2.

The solubility of dopants, in addition to the cation vacancy, plays a pivotal role in facilitating the rapid formation of cubic GeSe-based materials. The powder XRD patterns of the (Ge1−yPbySe)1−x(Sb2Te3)x series (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2), alongside scanning electron microscopy (SEM) combined with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) (Supplementary Figs. 7–12), confirmed the absence of any impurity phases. Additionally, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements confirmed the valence states of Ge, Pb, Sb, Se, and Te as 2+, 2+, 3+, 2−, and 2−, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 13). To further investigate the chemical composition and distribution in the (GeSe)0.9(Sb2Te3)0.1 sample, transmission electron microscopy (TEM), known for its high chemical sensitivity and spatial resolution, was employed. Figure 3a, obtained by high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) imaging, reveals a smooth surface with no evidence of secondary phases. EDS mapping further supports this observation, showing a uniform distribution of the matrix elements Ge and Se, as well as the dopants Sb and Te, throughout the sample. These findings, combined with XRD and SEM results, confirm the effective incorporation of metavalent Sb2Te3 into the GeSe matrix. A similar absence of impurity phases was observed in other metavalent Ag-V-VI2 alloyed GeSe systems38,39. In contrast, when GeSe was alloyed with compounds possessing different bonding types (e.g., covalent, ionic, or metallic bonding), such as InSe58, InTe34, CdTe27, MnCdTe235, AgInTe236, and AgSnTe243, secondary phases like In2Se3, Ge2In2Se6, MnCdSe2, CdSe, and Ag2Te were formed. This highlights the superior solubility of MVB compounds, such as Sb2Te3, in GeSe, which promotes the full stabilization of the cubic phase while effectively preventing the formation of undesired secondary phases. Thus, alloying with high-solubility, non-stoichiometric MVB compounds, combined with the deliberate introduction of cation vacancies, is identified as a critical factor in accelerating the orthorhombic-to-cubic phase transition in chalcogenide materials. This approach highlights the synergy between chemical design and defect engineering in stabilizing the cubic phase under ambient conditions.

a Low-resolution TEM images of (GeSe)0.9(Sb2Te3)0.1, including energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) mapping of elements Ge, Sb, Se, and Te. b High-resolution imaging reveals nanoscale or atomic-scale defects. c A close-up of b, showing atomic arrays compared with the corresponding atomic model of the cubic phase. d The fast Fourier transform (FFT) of b reveals the diffraction pattern of cubic GeSe along the \([0\overline{1}0]\) direction. e High-intensity Ge vacancies in (GeSe)0.9(Sb2Te3)0.1. f A close-up image collected from the white box in (e). g Corresponding intensity profile marked in f.

The high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image in Fig. 3b further confirms the cubic structure of (GeSe)0.9(Sb2Te3)0.1. A magnified view of the white boxed region in Fig. 3b reveals a well-defined atomic arrangement, where alternating Ge and Se atoms occupy the lattice positions. Due to the higher atomic number of Se (34) compared to Ge (32)53, Se anions appear with brighter contrast, as illustrated in Fig. 3c. The observed atomic structure aligns perfectly with the atomic-level crystal structure model of cubic GeSe. To further verify the crystal structure, a fast Fourier transform (FFT) analysis was performed to identify the diffraction pattern. As shown in Fig. 3d, the FFT pattern corresponds to a cubic GeSe phase projected along the \([0\overline{1}0]\) direction. This analysis confirms that Sb2Te3 alloying successfully induces the formation of cubic GeSe.

Typically, rhombohedral and cubic GeSe exhibit lower Ge vacancy formation energy compared to the orthorhombic phase, creating a more favorable environment for Ge precipitation and resulting in Ge vacancy defects35,48. Specifically, in rhombohedral GeSe systems, Ge vacancy planes are frequently observed, primarily due to larger atoms substituting smaller Ge atoms, leading to a pinning effect on the cation vacancy migration process34. In this work, HRTEM analysis was conducted to explore structural defects in cubic GeSe. As shown in Fig. 3e, a high density of stripe-like defects was observed in (GeSe)0.9(Sb2Te3)0.1, consistent with previously reported characteristics of Ge vacancy planes34. Figure 3f provides a magnified view of the boxed region in Fig. 3e, clearly showing weaker contrast for vacancy planes compared to lattice positions occupied by atoms. To further characterize these defects, Fig. 3g illustrates the line intensity distribution corresponding to Se layers, Ge layers, and Ge vacancy stripe layers. A significant intensity reduction (~35 ~ 40%) is observed for the vacancy layers, directly visualizing the presence of Ge vacancy defects. These Ge vacancy defects effectively scatter mid-frequency phonons, thereby suppressing the κL, contributing to the improved thermoelectric performance of the material.

To investigate the effect of Sb2Te3 alloying on the electrical transport properties, we used DFT to calculate the electronic band structures of orthorhombic GeSe, cubic GeSe, and Sb2Te3-alloyed cubic GeSe. Figure 4a–c show band structures of the orthorhombic GeSe, cubic GeSe, and cubic (GeSe)0.9(Sb2Te3)0.1, and Fig. 4d-f show corresponding partial density-of-states (PDOS). Orthorhombic GeSe exhibits an indirect Eg of 0.79 eV (Fig. 4a), where the relatively large Eg leads to low nH and limits the potential for achieving a high S2σ (Fig. 4d). In contrast, pure cubic GeSe shows a direct Eg of 0.05 eV along the L-symmetry direction (Fig. 4b), making it highly susceptible to minority carrier excitation and, consequently, to bipolar conduction effects (Fig. 4e). Upon Sb2Te3 alloying, the Eg widens significantly to 0.33 eV (Fig. 4c), effectively mitigating the detrimental impact of bipolar conduction (Fig. 4f). This Eg optimization highlights the critical role of Sb2Te3 alloying in improving the electronic properties of cubic GeSe and enhancing its thermoelectric performance.

Additionally, in orthorhombic GeSe, the valence band maximum (VBM) is located along the Γ-Y direction, exhibiting a valley degeneracy (NV) of 2 (Supplementary Fig. 14a). By increasing the doping level and shifting the Fermi level deeper into the valence band, a second maximum can emerge at the Γ point, increasing NV to 3. However, due to the inherently low solubility of dopants in covalently bonded GeSe, achieving such high nH experimentally remains challenging24. In contrast, cubic GeSe, with its higher symmetry Brillouin zone, has its VBM located at the L point, resulting in a high NV of 4 (Supplementary Fig. 14b). At higher doping levels, the Σ band, which exhibits an NV of 12, can also contribute to conduction, leading to a total NV of 16 in cubic GeSe. This behavior is similar to that observed in cubic PbTe and GeTe59,60. However, in binary cubic GeSe, the significant energy separation (ΔE = 0.39 eV) between the first and second valence band maxima limits the contribution of deeper valence bands to electrical transport. In this context, Sb2Te3 alloying plays a crucial role in reducing ΔE, facilitating the convergence of multiple valence bands. This promotes substantial orbital convergence and enhances the m*, thereby improving the thermoelectric performance of cubic GeSe.

To elucidate the impact of non-stoichiometric metavalent Sb2Te3 alloying on the electrical transport properties of all (Ge1−yPbySe)1−x(Sb2Te3)x samples, Fig. 5a presents the room-temperature nH and μH. Initially, pure orthorhombic GeSe exhibited an extremely low nH of 1.2 × 1016 cm−3, attributed to its relatively wide Eg and sparse Ge vacancies. Furthermore, the limited solubility of dopants in orthorhombic GeSe hindered the effective tuning of the Fermi level required to optimize nH. Metavalent Sb2Te3 alloying rapidly converted the CVB-dominated orthorhombic GeSe into MVB-connected cubic GeSe by deliberately introducing additional cation vacancies. This structural transition led to a dramatic increase in room-temperature nH, skyrocketing from 1.2 × 1016 cm−3 in binary orthorhombic GeSe to 2.7 × 1020 cm−3 and 5.6 × 1020 cm−3 in the x = 0.075 and x = 0.15 samples, respectively. This significant increase arose from the phase transition from the orthorhombic to the cubic structure, which considerably narrowed the Eg. Moreover, unlike materials dominated by strong CVB interactions with few cation vacancies, MVB materials inherently generate cation vacancies to eliminate energetically unfavorable anti-bonding interactions31, leading to a four-order-of-magnitude increase in nH. Additionally, the larger atomic radius of Pb compared to Ge suppresses the formation of Ge vacancies, resulting in a slight reduction in nH in Pb-containing samples.

a Room-temperature carrier concentration (nH) and carrier mobility (μH). Temperature-dependent (b) electrical conductivity (σ) and c Seebeck coefficient (S). d Calculated Pisarenko curves at room temperature based on the single parabolic band (SPB) model. e The effective mass (m*) in comparison with literature data27,34,35,38,39,42,43,58. f Temperature-dependent weighted mobility (μW). g The power factor (S2σ) vs. nH relationship calculated using SPB model at room temperature. h Temperature-dependent S2σ. i Temperature-dependent S2σ derived in the present work and other high-performance GeSe-based materials26,27,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,58,64.

According to the Kane band model61, the effective mass of the band edge carriers (mb*), which is inversely proportional to the Eg, plays a critical role in determining electrical transport properties. In orthorhombic GeSe, the larger Eg results in flatter valence band edges, which are associated with a higher mb*. This leads to a significantly lower μH at room temperature, measured at 1.2 cm2 V−1 s−1 35. Alloying with Sb2Te3 induces a dual transformation effect. For one thing, Sb2Te3 alloying enhances the crystal symmetry and significantly reduces Eg, leading to a lower mb* and a rapid increase in μH. For another, the introduction of Sb2Te3 and Pb introduces a substantial number of substitutional point defects and cation vacancies, which enhance the point defect scattering on the carriers. These opposing effects resulted in an initial sharp increase in room-temperature μH for the cubic x = 0.10 sample, reaching 7.8 cm2 V−1 s−1, followed by a gradual decline to 2.3 cm2 V−1 s−1 in the cubic x = 0.15 sample. This trend reflects the balance between improved band structure and increased point defect scattering in the alloyed system. Figure 5b presents the temperature-dependent σ of the (Ge1−yPbySe)1−x(Sb2Te3)x samples. Initially, σ increases significantly with the addition of Sb2Te3, followed by a gradual decrease as the Sb2Te3 content continues to rise. The initial increase in σ is directly linked to the substantial enhancements in both nH and μH. However, despite the continued rise in nH, the subsequent decrease in σ is primarily attributed to the reduction in μH. For example, at room temperature, σ increases sharply from 0.3 S m−1 for the orthorhombic x = 0 sample to an impressive 3.3 × 104 S m−1 for the cubic x = 0.075 sample, before slightly decreasing to 2.0 × 104 S m−1 for the cubic x = 0.15 sample. Additionally, pristine orthorhombic GeSe and low Sb2Te3-alloyed samples (0 ≤ x < 0.10) show an increase in σ with temperature, indicative of semiconductor-like transport dominated by carrier grain boundary scattering. In high Sb2Te3-alloyed samples (x ≥ 0.10), the high nH reduces grain boundary scattering, leading to a decrease in σ near room temperature, reflecting metal-like behavior. However, the introduction of Pb slightly lowers nH, reinstating thermally activated σ and semiconductor-like behavior.

In contrast to the σ, the S initially undergoes a significant decrease, followed by an increase with increasing Sb2Te3 and Pb content, as shown in Fig. 5c. Specifically, at room temperature, S drops sharply from 775 μV K−1 in pristine GeSe to 130 μV K−1 for the x = 0.05 sample, before increasing to 232 μV K−1 for the x = 0.10, y = 0.07 sample. The initial decrease in S for the Sb2Te3-alloyed samples is primarily attributed to the dramatic increase in nH, which rises by four orders of magnitude compared to the original orthorhombic GeSe. This significant increase in nH reduces the thermoelectric voltage generated per unit temperature gradient, leading to the observed reduction in S. Moreover, the S of pristine orthorhombic GeSe reaches its peak around 473 K before decreasing at higher temperatures, indicating the onset of a bipolar effect. This effect is intensified by its ultra-low nH, despite the large Eg, and severely diminishes S and consequently the ZT at elevated temperatures. However, Sb2Te3 and Pb alloying facilitate the formation of cubic GeSe, which significantly increases nH and shifts the onset temperature of the bipolar effect to higher values.

In addition to the nH, the S is closely tied to the m*, a key parameter influencing thermoelectric performance. Using the single parabolic band (SPB) model62, we calculated the relationship between S and nH at room temperature, highlighting the significant impact of Sb2Te3 alloying on m* (Fig. 5d). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 14, orthorhombic GeSe exhibits a relatively low m* of 0.72 m0, attributed to its limited NV = 2. However, the incorporation of non-stoichiometric metavalent Sb2Te3 effectively mitigates Peierls distortion, facilitating the transition of GeSe to the cubic structure. This structural evolution leads to a substantial increase in NV = 4. Moreover, electronic band structure calculations reveal that Sb2Te3 alloying promotes multivalley band convergence, further enhancing m*. As a result, cubic (Ge0.95Pb0.05Se)0.9(Sb2Te3)0.1 achieves an exceptional m* of 4.82 m0, the highest reported value for rhombohedral and cubic GeSe-based alloys (Fig. 5e)27,34,35,38,39,42,43,58. This significant increase in m* explains the observed improvements in thermoelectric performance in the Sb2Te3-alloyed samples.

Weighted mobility (μW) analysis provides deeper insights into the electronic band structure and scattering mechanisms within the material, offering a clearer evaluation of electron transport properties by considering the interplay between μH and m* 63. Figure 5f illustrates the variation of μW over the entire temperature range, calculated using the method described in the literature. Notably, the cubic (GeSe)0.9(Sb2Te3)0.1 sample exhibits the highest μW across the entire temperature range. Compared to pristine orthorhombic GeSe, the significant increase in μW highlights the effective manipulation of the electronic band structure facilitated by Sb2Te3 alloying. While Pb substitution leads to a slight reduction in μW, attributed to enhanced alloy scattering, particularly at ambient temperatures. The μW of cubic (Ge0.95Pb0.05Se)0.9(Sb2Te3)0.1 consistently remains above 40 cm2 V−1 s−1 at all temperatures. This robust performance underscores the tremendous potential of the material for further enhancing its ZT, demonstrating its viability for high-performance thermoelectric applications.

Figure 5g elucidates the relationship between S2σ and nH. The addition of Sb2Te3 causes a rapid increase in nH, bringing it closer to the optimal threshold. Notably, the actual nH of the x = 0.10 sample aligns closely with the ideal value. This synergistic optimization of nH and μW significantly enhances S2σ across the entire temperature range, as depicted in Fig. 5h. Specifically, the cubic x = 0.10 sample achieves a peak S2σ of 15.12 μW cm−1 K−2 at 723 K, which is approximately 32 times higher than that of pristine orthorhombic GeSe (0.46 μW cm−1 K−2). Although the introduction of trace Pb slightly reduces nH and μW, the cubic (Ge0.95Pb0.05Se)0.9(Sb2Te3)0.1 sample still demonstrates a highly competitive maximum S2σ of 13.52 μW cm−1 K−2. This exceptional performance makes it one of the most efficient GeSe-based thermoelectric materials reported to date26,27,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,58,64, as illustrated in Fig. 5i, underscoring its significant potential for high-performance thermoelectric applications.

Non-stoichiometric metavalent Sb2Te3 alloying has a profound impact on the thermal transport properties, as shown in Fig. 6. Evidently, the κ decreases rapidly with increasing Sb2Te3 content near room temperature, and this trend becomes even more pronounced with subsequent Pb alloying (Fig. 6a). Although Pb alloying slightly reduces S2σ, it intensifies phonon scattering through point defects, further lowering κL, and also reduces κe due to a decrease in σ. Together, these effects result in a significant reduction in total κ. Specifically, the room-temperature κ gradually decreases from 1.76 W m−1 K−1 in pristine orthorhombic GeSe to 0.86 W m−1 K−1 for the cubic x = 0.10 sample and further to 0.65 W m−1 K−1 for the cubic x = 0.10, y = 0.05 sample. This substantial reduction in κ demonstrates the effectiveness of Sb2Te3 and Pb alloying in suppressing thermal transport, which is crucial for enhancing the thermoelectric performance of GeSe-based materials.

Temperature-dependent of a total thermal conductivity (κ) and b lattice thermal conductivity (κL). c Temperature-dependent and d room-temperature κL derived in the present work and other GeSe-based materials26,27,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,58,64. Room-temperature (e) sound velocity (vm) and f Grüneisen constants (γ) as a function of Sb2Te3 and Pb content. g Room-temperature κL as a function of Sb2Te3 content for (GeSe)1−x(Sb2Te3)x series. The red dotted line and bule dotted line represent the fitted κL considering the mass and strain contrast between Ge-Sb and Se-Te, and mass and strain contrast between Ge-Sb, Se-Te, and Ge vacancy, respectively. h Calculated spectral lattice thermal conductivity (κs) using the Debye-Callaway model. i Relationship between μW and 1/κL at 300 K in comparison with literature data27,35,42.

The κL was calculated by subtracting the electronic contribution (κe) from the κ. κe was determined using the Wiedemann-Franz law65, κe = LσT, where L is the Lorenz number estimated using the formula L = 1.5 + exp(−|S | /116) (Supplementary Fig. 15). Figure 6b visually illustrates the effect of Sb2Te3 and Pb alloying on κL. Notably, near room temperature, κL decreases progressively with increasing Sb2Te3 and Pb content. Specifically, room-temperature κL significantly decreases from 1.71 W m−1 K−1 for pristine orthorhombic GeSe to 0.72 W m−1 K−1 for cubic x = 0.10 sample, and further to 0.61 W m−1 K−1 for cubic x = 0.10, y = 0.05 sample. Remarkably, for the (Ge0.95Pb0.05Se)0.9(Sb2Te3)0.1 sample, the κL reaches a minimum of 0.42 W m−1 K−1 at 723 K, approaching the amorphous limit of GeSe24. Figures 6c, d compare the κL values obtained in this study with literature-reported data, revealing that the current κL values are among the lowest for GeSe-based thermoelectric materials. These findings highlight the exceptional ability of Sb2Te3 and Pb alloying to suppress κL and improve thermoelectric performance26,27,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,58,64. Furthermore, pristine orthorhombic GeSe exhibits a κL ~ T−1.21 trend, aligning with acoustic phonon scattering (κL ~ T−1.0). Alloying with Sb2Te3 and Pb reduces the power law exponent. Specifically, the cubic (Ge0.95Pb0.05Se)0.9(Sb2Te3)0.1 sample demonstrates a κL ~ T−0.45 trend, consistent with dominant alloy scattering (κL ~ T−0.5).

To explore the mechanisms contributing to the reduction in κL toward the theoretical minimum for GeSe, the following factors can be identified. Firstly, according to the phonon transport model, vm is a critical determinant of κL. vm is influenced by the interatomic force constant (F), which reflects the chemical bond strength, and the atomic mass (M) according to \({v}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}}\propto \sqrt{F/M}\) 31. In orthorhombic GeSe, the strong CVB, where a pair of electrons is shared between neighboring atoms, results in rigid bonds and a higher vm. In contrast, cubic GeSe with MVB, characterized by single-electron sharing between neighboring atoms, exhibits weaker chemical bonds, leading to a lower vm. This reduction in bond strength is corroborated by the elongated bond lengths observed in XRD refinements (Fig. 2c) and the reduced bulk/Young’s modulus and Debye temperature listed in Supplementary Table 3, all indicating weaker bonds in cubic GeSe. Secondly, the replacement of Ge with heavier atoms like Sb and Pb, and Se with Te, further reduces vm. For example, the room-temperature vm decreases significantly from 2242 m s−1 in pristine orthorhombic GeSe to 2139 m s−1 in the cubic x = 0.10 sample and further to 2073 m s−1 in the cubic x = 0.10, y = 0.05 sample (Fig. 6e). These mechanisms demonstrate how Sb2Te3 and Pb alloying effectively weaken the bonds and reduce the vm, thereby suppressing κL and enhancing thermoelectric performance.

Additionally, lattice anharmonicity plays a critical role in controlling intrinsic phonon scattering by the Umklapp process (U-process), which significantly affects κL31. U-process scattering has been identified as the dominant phonon scattering mechanism in most thermoelectric materials66. In contrast to the behavior of covalently bonded orthorhombic GeSe, the highly delocalized p-electrons in metavalently bonded cubic GeSe exhibit long-range interactions along the <100> direction. These interactions induce significant electron-transverse optical phonon coupling, which softens optical phonon modes and enhances lattice anharmonicity. The softened optical phonons strongly couple with heat-carrying acoustic phonons through anharmonic scattering, reducing the group velocity of acoustic phonons and expanding the phase space for Umklapp scattering processes66. To quantify this effect, we calculated the Grüneisen parameter (γ), an indicator of lattice anharmonicity31. Higher γ values indicate greater anharmonicity, which, in turn, results in lower κL. As shown in Fig. 6f, at room temperature, γ increases from 1.36 in orthorhombic GeSe to 1.67 in the cubic x = 0.10 sample, and then gradually rises to 1.71 in the cubic x = 0.10, y = 0.07 sample. Additionally, we observed a slight decrease in γ (and a corresponding increase in vm) with higher Sb2Te3 contents (x > 0.05), likely due to the influence of Sb2Te3 alloying on the phonon dispersion relationship. In summary, this increase in anharmonicity, driven by MVB and the softening of optical phonons, is a key factor in the further reduction of κL.

Additionally, Sb2Te3 and Pb co-alloying introduces substitution and vacancy point defects, disrupting the lattice periodicity and inducing mass and strain field fluctuations, which enhance phonon scattering. Therefore, a point defect scattering model was employed to simulate the impact of mass and strain contrast on κL67,68, as illustrated in Fig. 6g. Specifically, we considered three types of point defects: Sb/Ge substitution, Te/Se substitution, and Ge vacancies. The simulation revealed that even with these combined scattering mechanisms, the experimentally observed κL in (GeSe)1−x(Sb2Te3)x is significantly lower than the theoretical predictions. This discrepancy suggests the presence of additional phonon scattering mechanisms beyond those considered in the point defect model. To further investigate the impact of multiscale microstructures on heat transport in the (Ge0.95Pb0.05Se)0.9(Sb2Te3)0.1 sample, the Debye-Callaway model was applied to calculate the spectral lattice thermal conductivity (κs)69 (Fig. 6h). This model accounted for various phonon scattering mechanisms, including Umklapp and normal processes (U + N), grain boundaries, substitutions, Ge vacancies, and Ge vacancy layers (detailed calculation parameters are provided in Supplementary Table 4 of the Supporting Information). The area between the two κs curves corresponds to the reduction in κL caused by each specific phonon scattering mechanism: grain boundaries primarily scatter low-frequency phonons, substitutions and Ge vacancies primarily impede high-frequency phonon transport, and planar defects significantly reduce κL by scattering mid-frequency phonons. In summary, the combination of weakened chemical bonding, strong lattice anharmonicity, and the presence of multiple phonon-scattering centers collectively reduces κL, bringing it closer to the theoretical minimum. These factors highlight the synergy between material design and multiscale defect engineering in optimizing thermoelectric performance. Besides, stabilizing cubic GeSe through non-stoichiometric metavalent Sb2Te3 alloying enables a synergistic optimization of electrical and thermal transport properties. This is clearly demonstrated by the correlation between the μW and the reciprocal of the κL (1/ κL) at 300 K (Fig. 6i)27,35,42 and the temperature-dependent quality factor (βB) (Supplementary Fig. 16) for (Ge1−yPbySe)1−x(Sb2Te3)x samples.

As shown in Fig. 7a and Supplementary Table 5, the cubic (Ge0.95Pb0.05Se)0.9(Sb2Te3)0.1 sample exhibits an optimized nH, enhanced μH, increased m*, and reduced κL, collectively leading to a maximum ZT (ZTmax) of 1.38 at 723 K, representing a remarkable 27-fold improvement compared to pristine orthorhombic GeSe, which shows a ZTmax of 0.05 at 673 K. This ZTmax is the highest reported to date for GeSe-based alloys, spanning orthorhombic, rhombohedral, and cubic structures (Figs. 1c, 7b)24,26,33,34,35,36,37,38,40,41,42,43,64. Moreover, as illustrated in Fig. 7c, the ZTave values for samples with x = 0.10 across the y series consistently exceed 0.60, highlighting their excellent thermoelectric performance over a wide temperature range. These results underscore the significant potential of Sb2Te3-alloyed cubic GeSe for high-performance thermoelectric applications. Although trace amounts of Pb are incorporated in this work, its usage is reduced by an order of magnitude compared to traditional PbTe-based alloys. Moreover, there is an inherent trade-off between material toxicity and achieving high ZT values, as superior performance is essential for thermoelectric applications.

a Temperature-dependent ZT values for (Ge1−yPbySe)1−x(Sb2Te3)x samples. b Temperature-dependent ZT for cubic (Ge0.95Pb0.05Se)0.9(Sb2Te3)0.1, comparing with those of other high-ZT cubic GeSe-based materials38,42,43,47. c The average ZT (ZTave) values for the (Ge1−yPbySe)1−x(Sb2Te3)x samples. d Fracture toughness (KIC), e Vickers hardness (HV), and f compression strength (σbc) at 300 K for the (Ge1−yPbySe)1−x(Sb2Te3)x samples. Current (I)-dependent (g) output voltage (V), h output power (P), and i η of a single-leg (Ge0.95Pb0.05Se)0.9(Sb2Te3)0.1 device under various ∆T.

The mechanical properties of thermoelectric materials have become increasingly important as they determine their processability, operational stability, and cost-effectiveness in thermoelectric devices. Sb2Te3 and Pb alloying significantly enhance critical mechanical parameters, such as fracture toughness (KIC), Vickers hardness (HV), and compressive strength (σbc). Pristine orthorhombic GeSe exhibits moderate mechanical properties, with KIC of 0.36 MPa m1/2, HV of 1.1 GPa, and σbc of 255 MPa (Fig. 7d–f). The introduction of Sb2Te3 leads to substantial improvements: for the cubic x = 0.10 sample, KIC increases to 0.88 MPa m1/2, HV rises to 1.8 GPa, and σbc reaches a peak of 495 MPa. Further substitution with Pb results in slight additional enhancements, with KIC reaching 0.90 MPa m1/2, HV improving to 2.1 GPa, and σbc climbing to 555 MPa. Since metavalent bonding is inherently weaker and associated with a high concentration of cation vacancies, cubic GeSe is expected to exhibit lower HV and σbc than orthorhombic GeSe. However, alloying with Sb2Te3 and Pb introduces significant solid-solution strengthening, enhancing HV and σbc beyond those of the original orthorhombic GeSe. Although solid-solution strengthening can sometimes reduce toughness, MVB acts as an intermediate state between localized covalent and delocalized metallic bonding, enabling materials to absorb and distribute strain more effectively under stress. This mechanism mitigates brittle fracture and enhances toughness, explaining the superior KIC of Sb2Te3 and Pb co-alloyed cubic GeSe compared to its orthorhombic counterpart. This enhanced mechanical performance makes Sb2Te3- and Pb-alloyed cubic GeSe more suitable for practical thermoelectric applications, offering both improved durability and processability.

After achieving enhanced thermoelectric and mechanical performance, we fabricated a single-leg thermoelectric device using the optimized cubic (Ge0.95Pb0.05Se)0.9(Sb2Te3)0.1 sample and evaluated its performance with a custom-designed system. Figure 7g illustrates the current (I) and output voltage (V) characteristics of the single-leg device under various ΔT, with the cold-side temperature (Tc) maintained at 285 K. The internal resistance (Rin) of the device was calculated from the slope of the V-I curves, and the open-circuit voltage (VOC) increased significantly as the hot-side temperature (Th) rose from 523 to 723 K. Specifically, the VOC increased from 49.6 to 98.9 V, while Rin decreased from 1.71 to 1.39 Ω. Concurrently, the V decreased linearly with increasing I. Figures 7h, i show the output power (P) and η as functions of I under different ΔT. Both P and η initially increased with I, reaching their maximum values when the external load resistance matched Rin, and then decreased. Ultimately, the single-leg device achieved a maximum power density of 0.21 W cm−2 and a peak η of 6.13% under a ΔT of 430 K. The experimentally measured η remains significantly lower than the theoretical value of 8.36%, which can be attributed to several factors, including inconsistencies in the soldering process, heat losses within the testing apparatus, non-ideal characteristics of the thermoelectric model, dimensional inaccuracies, and measurement errors in the module70. These factors highlight the need for further optimization of device fabrication and measurement techniques to fully realize the theoretical performance potential of the materials. Furthermore, the development of high-performance n-type GeSe-based alloys to complement their p-type counterparts is critical for fabricating efficient p-n legs in thermoelectric devices. This advancement represents a key area for future research and is essential for facilitating the industrial-scale application of GeSe-based materials.

In conclusion, we synthesized a series of (Ge1−yPbySe)1−x(Sb2Te3)x samples to explore the strategies for accelerating the orthorhombic-to-cubic phase transition in chalcogenides. Our findings reveal that only 10% metavalent Sb2Te3 alloying is sufficient to stabilize cubic GeSe under ambient conditions without the formation of detectable impurity phases. This stabilization is attributed to the high solubility of Sb2Te3 and its role in introducing additional cation vacancies. Compared to its covalently bonded orthorhombic counterpart, the metavalently bonded cubic GeSe exhibits a lower Ge vacancy formation energy, a narrower Eg, and higher valley degeneracy. The Sb2Te3 alloying further facilitates multivalley band convergence, enhancing orbital degeneracy, and optimizing nH, improve μH, and increase m*. These improvements lead to a significant enhancement in S2σ. Moreover, the weak chemical bonding, strong lattice anharmonicity, and multiple phonon-scattering centers in the cubic (Ge1−yPbySe)1−x(Sb2Te3)x effectively suppress κL to 0.42 W m−1 K−1 at 723 K, approaching the amorphous limit of GeSe. As a result, cubic (Ge0.95Pb0.05Se)0.9(Sb2Te3)0.1 achieves an impressive ZT of 1.38 at 723 K and a peak η of 6.13% under a ∆T of 430 K in a single-leg thermoelectric device. These findings highlight the critical role of chemical bonding and vacancy engineering in facilitating the orthorhombic-to-cubic phase transition in chalcogenides and provide valuable insights for designing next-generation thermoelectric materials.

Methods

Synthesis procedure

All the GeSe-based samples were prepared using a systematic process involving melting, quenching, ball milling, and spark plasma sintering (SPS). High-purity element chunks of Ge, Se, Sb, Te, and Pb (≥ 99.999%, Beijing Yipin Chuancheng Technology Co., Ltd.) were weighed according to the stoichiometric compositions (GeSe)1−x(Sb2Te3)x (x = 0.05, 0.075, 0.10, 0.125, 0.15) and (Ge1−yPbySe)0.9(Sb2Te3)0.1 (y = 0.03, 0.05, 0.07). The weighted materials were placed into quartz tubes with a 20 mm diameter and sealed under a vacuum of 10−3 Pa. The encapsulated mixtures were heated in a muffle furnace to 1323 K for 8 hours, held at this temperature for 10 hours, and then cooled to 1123 K, followed by rapid quenching in water. The resulting ingots were pulverized using a ball mill (MSK-SFM-3, MTI Corporation) at 1000 rpm for 25 minutes under vacuum. The resulting fine powders were then consolidated using SPS at 723 K for 5 minutes under a uniaxial pressure of 50 MPa, producing high-density cylindrical samples with a 20 mm diameter, suitable for microstructural analysis and thermoelectric performance evaluation.

Phase and microstructure characterization

The phase purities and crystal structures of the samples were analyzed at room temperature using XRD (Cu-Kα radiation, SmartLab, Rigaku®, Japan). Lattice parameters for the various crystal structures were determined via Rietveld refinement using the Fullprof Suite software52. The uncertainty in the XRD structural refinement was quantified as ± 0.002 Å. The chemical valence states were confirmed using XPS (Thermo ESCALAB 250, Japan) with monochromatic Al Kα radiation. Microstructural characterizations were conducted using SEM (Hitachi® SU-70, Japan) equipped with EDS, along with high-resolution TEM (HRTEM, FEI Titan Themis G2 300).

Thermoelectric performance measurement

The temperature-dependent σ and S were simultaneously measured using a ZEM-3 (Ulvac-Riko®, Japan) under a protective helium atmosphere, with the measuring error of 10% for σ and 7% for S. In this vein, the σ was measured using four-probe method and the S was measured by static direct-current methods. Thermal diffusivity (D) was determined by the laser flash method (LFA 467, Netzsch®, Germany), with the measure error of 3%. The sample density (d) was evaluated using the Archimedes method71, while the specific heat capacity (Cp) was estimated using the Dulong-Petit law72. The κ was then calculated using the formula κ = DdCp. The κe was computed using the Wiedemann-Franz law73, κe = LσT, where the Lorenz number (L) was estimated using the formula L = 1.5 + exp(−|S | /116)74. Subsequently, the κL was derived by subtracting κe from the κ. The maximum measurement temperature for all samples was 723 K. The Hall coefficient (RH) was measured at room temperature using the physical properties measurement system (PPMS-9, Quantum Design®, America). The uncertainty of RH measurements was ± 5%. nH and μH were calculated via the equation nH = 1/e RH and μH = σRH, respectively. The longitudinal (vl) and transverse (vt) components of sound velocity were measured using an ultrasonic pulse receiver (MS-100, Ritec Laboratories, France).

Data availability

The data generated in this study is provided in the Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Chen, W. et al. Nanobinders advance screen-printed flexible thermoelectrics. Science 386, 1265–1271 (2024).

Shi, X.-L., Zou, J. & Chen, Z.-G. Advanced thermoelectric design: from materials and structures to devices. Chem. Rev. 120, 7399–7515 (2020).

Yang, Q. et al. Flexible thermoelectrics based on ductile semiconductors. Science 377, 854–858 (2022).

Jiang, B. et al. High-entropy-stabilized chalcogenides with high thermoelectric performance. Science 371, 830–834 (2021).

Xiao, Y. & Zhao, L.-D. Seeking new, highly effective thermoelectrics. Science 367, 1196 (2020).

Li, L., Hu, B., Liu, Q., Shi, X.-L. & Chen, Z.-G. High-performance AgSbTe2 Thermoelectrics: advances, challenges, and perspectives. Adv. Mater. 36, 2409275 (2024).

Tang, Q. et al. High-entropy thermoelectric materials. Joule 8, 1641–1666 (2024).

Hu, H. et al. Highly stabilized and efficient thermoelectric copper selenide. Nat. Mater. 23, 527–534 (2024).

Hu, J. et al. Realizing ultrahigh conversion efficiency of ≈9.0% in YbCd2Sb2/Mg3Sb2 zintl module for thermoelectric power generation. Adv. Mater. 36, 2411738 (2024).

Li, K. et al. High-entropy strategy to achieve electronic band convergence for high-performance thermoelectrics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 14318–14327 (2024).

Ge, B. et al. Engineering an atomic-level crystal lattice and electronic band structure for an extraordinarily high average thermoelectric figure of merit in n-type PbSe. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 3994–4008 (2023).

Jia, B. et al. Pseudo-nanostructure and trapped-hole release induce high thermoelectric performance in PbTe. Science 384, 81–86 (2024).

Cui, J. et al. Two-dimensional-like phonons in three-dimensional-structured rhombohedral gese-based compounds with excellent thermoelectric performance. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 16, 39656–39663 (2024).

Shi, X., Song, S., Gao, G. & Ren, Z. Global band convergence design for high-performance thermoelectric power generation in Zintls. Science 384, 757–762 (2024).

Li, A. et al. Demonstration of valley anisotropy utilized to enhance the thermoelectric power factor. Nat. Commun. 12, 5408 (2021).

Li, Z. et al. Vacancy suppression and resonant level rendering extraordinary power factor in Sn0.99In0.01Te/Tourmaline composite. Small 20, 2402651 (2024).

Liang, R. et al. Compromise design of resonant levels in gete-based alloys with enhanced thermoelectric performance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2404021 (2024).

Zhu, J. et al. Vacancies tailoring lattice anharmonicity of Zintl-type thermoelectrics. Nat. Commun. 15, 2618 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. Ultralow thermal conductivity in vacancy-ordered halide perovskite Cs3Bi2Br9 with strong anharmonicity and wave-like tunneling of low-energy phonons. Small 20, 2405276 (2024).

Liu, D. et al. Lattice plainification advances highly effective SnSe crystalline thermoelectrics. Science 380, 841–846 (2023).

Qin, B., Kanatzidis, M. G. & Zhao, L.-D. The development and impact of tin selenide on thermoelectrics. Science 386, eadp2444 (2024).

Hao, S., Shi, F., Dravid, V. P., Kanatzidis, M. G. & Wolverton, C. Computational prediction of high thermoelectric performance in hole doped layered GeSe. Chem. Mater. 28, 3218–3226 (2016).

Zhang, M. et al. Compositing Effect Leads to Extraordinary Performance in GeSe-Based Thermoelectrics. Adv Funct Mater, 2500898 (2025).

Zhang, X. et al. Thermoelectric properties of GeSe. J. Materiomics 2, 331–337 (2016).

Yu, Y. et al. Doping by design: enhanced thermoelectric performance of GeSe alloys through metavalent bonding. Adv. Mater. 35, 2300893 (2023).

Sarkar, D. et al. Metavalent bonding in GeSe leads to high thermoelectric performance. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 60, 10350–10358 (2021).

Yao, W. et al. Two-step phase manipulation by tailoring chemical bonds results in high-performance GeSe thermoelectrics. Innovation 4, 100522 (2023).

Wuttig, M. et al. Revisiting the nature of chemical bonding in chalcogenides to explain and design their properties. Adv. Mater. 35, 2208485 (2023).

Arora, R., Waghmare, U. V. & Rao, C. N. R. Metavalent bonding origins of unusual properties of group iv chalcogenides. Adv. Mater. 35, 2208724 (2023).

Schön, C.-F. et al. Classification of properties and their relation to chemical bonding: essential steps toward the inverse design of functional materials. Sci. Adv. 8, eade0828 (2022).

Yu, Y., Cagnoni, M., Cojocaru-Mirédin, O. & Wuttig, M. Chalcogenide thermoelectrics empowered by an unconventional bonding mechanism. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1904862 (2020).

Lyu, T. et al. Advanced GeSe-based thermoelectric materials: progress and future challenge. Appl Phys. Rev. 11, 031323 (2024).

Wang, Z. et al. Phase modulation enabled high thermoelectric performance in polycrystalline GeSe0.75Te0.25. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2111238 (2022).

Hu, L. et al. In situ design of high-performance dual-phase gese thermoelectrics by tailoring chemical bonds. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2214854 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Crystal symmetry enables high thermoelectric performance of rhombohedral GeSe(MnCdTe2). x. Nano Energy 100, 107434 (2022).

Huang, Y. et al. Manipulation of metavalent bonding to stabilize metastable phase: a strategy for enhancing zT in GeSe. Interdiscipl Mater. 3, 607–620 (2024).

Dong, J. et al. High thermoelectric performance in rhombohedral GeSe-LiBiTe2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 17355–17364 (2024).

Yan, M. et al. Synergetic optimization of electronic and thermal transport for high-performance thermoelectric GeSe–AgSbTe2 alloy. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 8215–8220 (2018).

Huang, Z. et al. High thermoelectric performance of new rhombohedral phase of GeSe stabilized through alloying with AgSbSe2. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 56, 14113–14118 (2017).

Sarkar, D. et al. Ferroelectric instability induced ultralow thermal conductivity and high thermoelectric performance in rhombohedral p-type GeSe crystal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 12237–12244 (2020).

Guo, M. et al. Achieving superior thermoelectric performance in Ge4Se3Te via symmetry manipulation with I–V–VI2 Alloying. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2313720 (2024).

Lyu, T. et al. Stepwise Ge vacancy manipulation enhances the thermoelectric performance of cubic GeSe. Chem. Eng. J. 442, 136332 (2022).

Li, Y.-G. et al. Leveraging crystal symmetry for thermoelectric performance optimization in cubic GeSe. Rare Met. 43, 5332–5345 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Improved solubility in metavalently bonded solid leads to band alignment, ultralow thermal conductivity, and high thermoelectric performance in SnTe. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2209980 (2022).

Liu, M. et al. Doping strategy in metavalently bonded materials for advancing thermoelectric performance. Nat. Commun. 15, 8286 (2024).

Samanta, M. & Biswas, K. Low thermal conductivity and high thermoelectric performance in (GeTe)1-2x(GeSe)x(GeS)x: competition between solid solution and phase separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 9382–9391 (2017).

Roychowdhury, S., Ghosh, T., Arora, R., Waghmare, U. V. & Biswas, K. Stabilizing n-Type cubic GeSe by entropy-driven alloying of AgBiSe2: ultralow thermal conductivity and promising thermoelectric performance. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 57, 15167–15171 (2018).

Yan, M., Geng, H., Jiang, P. & Bao, X. Glass-like electronic and thermal transport in crystalline cubic germanium selenide. J. Energy Chem. 45, 83–90 (2020).

Wuttig, M. et al. The role of vacancies and local distortions in the design of new phase-change materials. Nat. Mater. 6, 122–128 (2007).

Sist, M., Kasai, H., Hedegaard, E. M. J. & Iversen, B. B. Role of vacancies in the high-temperature pseudodisplacive phase transition in GeTe. Phys. Rev. B 97, 094116 (2018).

Gan, L. et al. The thermoelectric performance in transition metal-doped PbS influenced by formation enthalpy. Appl Phys. Lett. 123, 192103 (2023).

Cui, X. et al. AutoFP: a GUI for highly automated Rietveld refinement using an expert system algorithm based on FullProf. J. Appl Crystallogr 48, 1581–1586 (2015).

Miller A. P. et al. Lange’s handbook of chemistry. American Public Health Association (1941).

Liu, R. et al. Entropy as a gene-like performance indicator promoting thermoelectric materials. Adv. Mater. 29, 1702712 (2017).

Zhang, W., Liaw, P. K. & Zhang, Y. Science and technology in high-entropy alloys. Sci. China Mater. 61, 2–22 (2018).

Sist, M. et al. High-temperature crystal structure and chemical bonding in thermoelectric germanium selenide (GeSe). Chem.-Eur. J. 23, 6888–6895 (2017).

Yu, H. et al. Unraveling a novel ferroelectric GeSe phase and its transformation into a topological crystalline insulator under high pressure. NPG Asia Mater. 10, 882–887 (2018).

Duan, B. et al. The role of cation vacancies in GeSe: stabilizing high-symmetric phase structure and enhancing thermoelectric performance. Adv. Energy Sustain Res. 3, 2200124 (2022).

Pei, Y. et al. Convergence of electronic bands for high performance bulk thermoelectrics. Nature 473, 66–69 (2011).

Hong, M., Li, M., Wang, Y., Shi, X.-L. & Chen, Z.-G. Advances in versatile GeTe thermoelectrics from materials to devices. Adv. Mater. 35, 2208272 (2023).

Kane, E. O. Band structure of indium antimonide. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1, 249–261 (1957).

May, A. F., Toberer, E. S., Saramat, A. & Snyder, G. J. Characterization and analysis of thermoelectric transport in n-type Ba8Ga16-xGe30-x. Phys. Rev. B 80, 125205 (2009).

Kim, M., Kim, S.-i., Kim, S. W., Kim, H.-S. & Lee, K. H. Weighted mobility ratio engineering for high-performance bi–te-based thermoelectric materials via suppression of minority carrier transport. Adv. Mater. 33, 2005931 (2021).

Zhang, M. et al. High-performance GeSe-based thermoelectrics via Cu-Doping. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2411054 (2024).

Liu, L., Liang, L., Deng, L., Wang, H. & Chen, G. Is there a constant Lorentz number for organic thermoelectric materials? Appl Mater. Today 27, 101496 (2022).

Lee, S. et al. Resonant bonding leads to low lattice thermal conductivity. Nat. Commun. 5, 3525 (2014).

Slack, G. A. Effect of isotopes on low-temperature thermal conductivity. Phys. Rev. 105, 829–831 (1957).

Abeles, B. Lattice thermal conductivity of disordered semiconductor alloys at high temperatures. Phys. Rev. 131, 1906–1911 (1963).

Callaway, J. & von Baeyer, H. C. Effect of point imperfections on lattice thermal conductivity. Phys. Rev. 120, 1149–1154 (1960).

Song, K., Wang, S., Duan, Y., Ling, X. & Schiavone, P. Effect of inevitable heat leap on the conversion efficiency of thermoelectric generators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 207001 (2023).

Yang, L., Wu, J. S. & Zhang, L. T. Synthesis of filled skutterudite compound La0.75Fe3CoSb12 by spark plasma sintering and effect of porosity on thermoelectric properties. J. Alloy. Compd. 364, 83–88 (2004).

Zosiamliana, R. et al. First-principles investigation of the electronics, optical, mechanical, thermodynamics and thermoelectric properties of Na based Quaternary Heusler alloys (QHAs) NaHfXGe (X = Co, Rh, Ir). J. Phys.-Condens Mat. 36, 065501 (2024).

Adam, A. M. et al. Thermoelectric power properties of Ge doped PbTe alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 872, 159630 (2021).

Kim, H.-S., Gibbs, Z. M., Tang, Y., Wang, H. & Snyder, G. J. Characterization of lorenz number with seebeck coefficient measurement. APL Mater. 3, 041506 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52471233 and 52071218), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2025B1515020023), the Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Commission (JCYJ20230808105700001), and the Shenzhen University 2035 Program for Excellent Research (00000218). The authors also appreciate the Instrumental Analysis Center of Shenzhen University. ZGC thanks the financial support from the Australian Research Council, HBIS-UQ Innovation Center for Sustainable Steel project, and the QUT Capacity Building Professor Program. This work was enabled by using the Central Analytical Research Facility hosted by the Institute for Future Environments at QUT.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.-G.C., L.H., and X.-L.S. supervised the overall experiments. L.H. designed the related experiments. Y.L., X.L., H.L., M.W., X.H., and M.Z. prepared materials and measured the thermoelectric properties, designed device structures, fabricated devices, and measured the performance. L.H., H.L., Y.L., M.Z., X.L., and Z.-G.C. analyzed the data. H.L. performed the device numerical simulation, and M.L. conducted the DFT calculations. H.L., L.H., and Z.-G.C. discussed the results. H.L. wrote the manuscript with the help of all the authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Aman Bhardwaj, Sahiba Bano, Kaleyathodi Gurukrishna, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, H., Shi, XL., Liu, Y. et al. Metavalent alloying and vacancy engineering enable state-of-the-art cubic GeSe thermoelectrics. Nat Commun 16, 3136 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58387-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58387-0