Abstract

Tearing tough soft solids such as rubbers, leather or meat is much harder than cutting them with a sharp blade. To understand why, we use samples labeled with mechanically sensitive fluorophores to investigate cutting and fracture behavior in PDMS elastomers and quantify the extent of bond scission resulting from cutting pre-stretched samples. Our findings reveal that stretch-induced cracks produce significant deformation, bond scission and blunting near the crack tip, requiring more energy to propagate. In contrast, using blades reduces the amount of stretching and blunting required for crack propagation, resulting in a lower fracture energy. The measured linear correlation between fracture energy and the areal density of broken chains clarifies the relationship between pre-stretching, blunting, and molecular damage. These multi-scale insights demonstrate the key differences between fracture and cutting mechanics of soft materials, allowing to optimize engineering applications, such as rubber and food processing, energy-efficient recycling, biomedical and surgical devices, protective equipment and sports gear.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soft and tough materials such as meat, leather, or filled rubbers are very difficult to tear apart, even when a small cut is made to weaken them. In contrast, cutting with a sharp blade is much easier, involving both lower forces and better control of the shape and surface finish of the parts. This sensitivity to blade cutting can also be a major limitation in the design of protective equipment, which has to resist penetration by needles or blades, or sports gear, where very tough materials can result in unexpected failure by accidental contact with blades. Understanding the origin of the different resistance of a material to cutting and tearing can open new promising strategies to design materials where these two properties can be triggered independently.

Fracture mechanics teaches us that the critical force is not the right metric to compare tearing and cutting since it strongly depends on the size and shape of the objects as well as on the way the loads are applied. The proper physical quantity to assess the resistance to crack growth is the fracture energy, i.e., the energy required to extend the crack by a unit area. Whether fracture energy can be used as a proper material metric to characterize fracture by cutting has been a matter of extensive research and is still debated1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Both tearing and cutting involve new surface creation in a material by the extension of an existing localized crack. However, in the tearing process, the energy required to extend the crack is due to the application of a remote load and reaches the crack tip through the singular stress/strain concentration fields. On the contrary, in the cutting process, the energy required to extend the crack is dominated by the work provided by the local contact of the blade against the material, which also modifies the local stress/strain fields. Although both processes can be analyzed with the Griffith energy balance criterion:

(where Uel and W are, respectively, the elastic energy stored in the sample and the external work, while A is the area of the crack surface) they provide different values of the crack extension energy \(\Gamma\) of the same material, even when minimizing the energy losses due to friction of the blade by pre-stretching the target material1. It is thus convenient to use different words to address them, i.e., respectively, the fracture energy and the cutting energy, while using the term crack extension energy to refer to either of them.

Research on blade-induced damage in soft materials remains relatively scarce, even if basic cutting experimental setups, like pure-shear2 and Y-shape cutting1,8,9 and their theoretical framework started decades ago. The influence of the blades’ geometry10, sharpness11,12, slicing13,14, and surface friction15 on the cutting energy have been addressed. More recently, Mars et al. combined numerical simulations and strain field measurements to show that cutting allows to localize large strains on a smaller region compared to fracture16,17. Hutchens et al. have proposed a dimensionless fracture-cutting parameter to phenomenologically link the values of the fracture and cutting energy through a power law combination of other material parameters, pointing out the prime importance of the strain-hardening characteristics of the material6,7. Yet, most of these experiments and numerical simulations have been conducted within the framework of continuum mechanics. A molecular-level understanding of the coupling between the nonlinear large strain and the damage occurring in the polymer network during the cutting process remains unknown. Addressing this shortcoming requires the development of new methodologies in order to link the crack extension energy to molecular-level energy dissipation, and in particular, energy dissipated by bond scission, which is not captured by viscoelastic models of energy dissipation18.

Recent advances in mechanochemistry applied to soft materials have made it possible to visualize and quantify molecular damage before19 and during fracture propagation20 in soft polymer networks under various loading situations and geometries21. This is possible by labeling the network with a force-sensitive molecule, or mechanophore incorporated as a crosslinker. As stress is applied, the molecule breaks irreversibly, and one of the fragments becomes fluorescent. Optical observation of the material with laser scanning confocal microscopy and proper calibration makes it possible to map and quantify the bond scission occurring near the fracture surface obtained by a macroscopic fracture process21,22,23. Quantitative mechanochemistry with properly labeled samples has, for example, revealed how viscoelastic energy dissipation and sacrificial bond scission couple during crack growth in multiple network elastomers23. The combination of damage and stress mapping in the process zone ahead of the crack tip has shed light on the mechanics of damage during the fracture of soft materials24, both in monotonic loading up to failure and in crack growth by cyclic fatigue22. Here, we present the first use of mechanochemistry to reveal how contact with a sharp blade influences molecular damage mechanisms in the macromolecular network during crack extension.

The pure-shear cutting experiment used in this study (Fig. 1a) was first reported by Lake and Yeoh1 in order to minimize the frictional contributions during the cutting process and to provide a well-defined steady-state cutting process (provided the crack propagation is intrinsically stable for the selected material). Using the Griffith energy approach Eq. (1) as a crack propagation criterion in steady-state conditions, Lake and Yeoh propose to split the strain energy release rate G in two contributions, G1 and G2, from cutting and stretching, respectively. The cutting term G1 results from the work done per unit crack area by the constant force f acting on the blade:

where t is the thickness of the sample, while the stretching term G2 (also called tearing, since it is the only active term in pure-shear tearing) results from the release of the constant elastic energy density stored in the pre-stretched material. For the present range of applied stretch (λ < 1.5), G2 can be conveniently approximated by the expression for a Neo-Hookean material as:

where h0 is the unstretched sample width, E is the Young modulus of the soft incompressible elastomer, and λ = h/h0 is the uniform pre-stretch applied to the material. The total strain energy release rate becomes then:

a Sketch of the pure-shear cutting and stretching experiment. b Sketch of the PDMS network at the molecular scale with unbroken mechanophores represented as blue stars and activated mechanophores as yellow stars. This damage occurs in the blunted crack tip zone during the combined stretching/cutting process. c Sketch of the post-mortem PDMS cutting sample.

In steady-state conditions, fracture mechanics implies that G should have a constant value: the crack extension energy \(\Gamma\).

Using a custom cutting and stretching setup (described in Methods and in the Supplementary information), we carried out a series of crack propagation experiments under combined stretching and cutting on mechanophore-labeled PDMS elastomer samples to quantify the changes in molecular damage occurring when the relative amount of applied stretching and cutting is systematically varied (Fig. 1b, c).

Results

A commercial grade of Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), i.e., Sylgard 184, was selected as a model elastomer since it is a readily available and well-characterized material, and it is suitable for incorporating a vinyl difunctionalized Diels-Alder adduct mechanophore (DACL) as a crosslinker19,25. PDMS’s mechanical properties, network structure26, and the damage induced by stress/strain concentration during fracture propagation have been previously investigated19,24,27,28, providing a robust framework for our cutting studies. The sample preparation is detailed in the Methods section. The comparison of the mechanical properties of the mechanophore-labeled and original PDMS material was evaluated in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Effect of increasing the pre-stretch on the cutting energy

Figure 2a reports the force-displacement measurements during a series of cutting tests with different values of the applied pre-stretch λ. All curves present an initial elastic loading phase due to the contact between the sample and the blade. After reaching a peak, the blade starts cutting through the sample, and the force reaches a plateau that corresponds to steady-state cutting. The values of the plateau forces, reported in Fig. 2b, systematically decrease with applied pre-stretch.

a Force-displacement curves during the cutting process for different stretch ratios λ. b Variation of the plateau force f (blue) and the blunting radius rb (red) as a function of stretch ratio λ. The error bars correspond to the standard deviation. c The crack extension energy obtained by Eq. (4) is represented as a function of the stretch ratio, as well as the two separate contributions to the strain energy release rate from cutting Eq. (2) and stretching Eq. (3). The results can be divided into three distinct regions: Region I: out-of-plane deformation and frictional contact, Region II: clean cutting in steady-state, and Region III: pure fracture without the blade. d Left: The crack opening profile for different stretch ratios (scale bar: 1 mm). Right: Parabolic fitting of the crack opening profile to estimate the blunting radius rb (R21 = 0.9484, R22 = 0.9688). NB: the crack tip region at a lower scale than the blunting radius was excluded from the parabolic fit since it is affected by non-linear terms29.

After summing the two contributions to the strain energy release rate according to Eq. (4), the crack extension energy was found not to be constant, as displayed in Fig. 2c. Its behavior can be divided into three regions. In region I (λ < 1.14), the stretch is too low to prevent the frictional contact of the crack lips with the sides of the blade, and the sample either wrinkles out-of-plane before cutting or cuts with an elevated force due to frictional contact on the sides of the blade. In region II (1.14 < λ < 1.42), we observe a clean cutting, i.e., a steady-state cutting with stable crack propagation and constant measured force f on the blade, resulting in smooth fracture surfaces. In region III (λ > 1.42), we observe a pure fracture propagation, i.e., the applied pre-stretch is large enough to allow the steady-state crack propagation ahead of the blade (without any contact between the sample and the blade).

Real-time imaging of the crack extension process in Fig. 2d reveals that the local crack tip opening increases with applied pre-stretch. This can be characterized by the blunting radius rb, i.e., the radius of curvature of the crack opening profile near the crack tip29. This was determined by extracting the crack opening profile by image analysis (Fig. 2d left) and fitting it by a parabolic function (Fig. 2d right). The results are plotted in Fig. 2b as a function of the applied pre-stretch showing that the increase of the blunting radius rb is concomitant to the decrease of the measured cutting force f.

In the following, we will focus on the intermediate region II (1.14 < λ < 1.42), which corresponds to the clean cutting regime where friction is minimized, and the crack grows in a well-defined steady-state regime under the combined action of stretching and cutting applied in variable proportions. This clean-cutting regime can be further divided in two sub-regions. For moderate applied stretch (1.14 < λ < 1.25), the increase of the applied pre-stretch is compensated by the decrease of the measured cutting force in order to maintain an almost constant total strain energy release rate. For larger applied stretch (1.25 < λ < 1.42), while the cutting force keeps decreasing, the total strain energy release rate is not constant but increases significantly with increasing applied stretch. Although this trend has previously been observed by Lake and Yeoh1, it was attributed to the observed appearance of unstable stick-slip propagation in the large pre-stretch region. Since in our model PDMS material, the crack propagation remains stable in the whole measured clean-cut regime, the measured increase of the total strain energy release rate must be attributed to a real increase of the cutting energy with the applied stretch under combined stretch/cutting. Understanding and modeling such an intrinsic dependency of cutting energy with the relative amount of stretching and cutting will be the core of our investigation.

Comparing cutting and fracture energy

When comparing the clean-cutting region II with the pure fracture region III in Fig. 2c, we observe that the crack extension energy is systematically lower in region II than the pure fracture energy of 540 J·m-2 (λ = 1.45) and decreases when decreasing the applied stretch, down to a plateau region of to 260 J·m-2 (λ = 1.2), which is generally referred to as the pure cutting regime1,6. We emphasize that the cutting energy of elastomers in the pure cutting regime has been shown to be independent of the blade sharpness when the terminal radius of the blade is below a threshold of about 120 nm7, which corresponds to our selected blades.

The crack extension energy is thus a monotonically increasing function of the applied stretch and also of the observed crack tip blunting. The contribution of the sharp blade cutting is thus not limited to providing a part of the work necessary to the fracture process, but somehow this also reduces the total energy needed for crack propagation. This very puzzling issue has pushed us to investigate the changes in the molecular damage mechanisms by using mechanochemistry tools illustrated in the next section.

Visualization and quantification of network damage in pure-shear cutting

In order to provide a quantitative mapping of the polymer chain damage during the combined stretching and cutting of the elastomer network, we incorporated mechanophores into the PDMS elastomer. As illustrated in Fig. 3a and b, the specialized mechanophore cross-linker in the elastomer undergoes force-induced scission, activating permanent fluorescence. By mapping the fluorescence intensity on the post-mortem fracture surfaces by confocal microscopy, we can determine the volume density of broken bonds in the PDMS network, for each of the combinations of applied stretch and cutting force. Figures 3c and d report some typical 2D sections of the 3D maps, measured perpendicularly to the fracture surface to appreciate the post-mortem damage distribution.

a Mechanophores (DACL) based on π-extended anthracene-maleimide adducts yield π-extended anthracene moieties upon force-induced cycloreversion. b The mechanophores are incorporated into the PDMS chains by substituting a given fraction of the crosslinks. c After cutting the pure shear samples at a given value of pre-stretch λ, fluorescence microscopy was performed near the fracture surfaces (red square) and represented in (d), the size bar corresponds to 100 μm in all damage maps: the PDMS sample is on the left of the bright fracture surface where damage is concentrated. e Comparison of the damage maps for two different pre-stretch λ of 1.2 (i) and 1.45 (ii) with the corresponding average depth profile of bond damage φy.

By measuring the fluorescence intensity on a series of calibrated samples of PDMS with variable densities of activated mechanophores, we evaluated the calibration parameter α by a linear fit (Supplementary Note 1). The fraction of activated mechanophores in the PDMS network φxyz can thus be estimated from the fluorescent intensity map I(x,y,z) as:

where c is the concentration of mechanophore crosslinks in the material, and Ibkg is the background fluorescence intensity of the image. This determination is based on the hypothesis that the probability of breaking an ordinary or mechanophore crosslink is the same, which has been validated for relatively dilute concentrations20.

Since the damage is distributed quite evenly along the fracture surfaces, we could increase the signal-to-noise ratio by averaging the depth profile of the damage φy as a function of the depth y below the fracture surfaces:

where xs (500 µm) and zs (50 µm) correspond to the dimensions of the sampled region along the x-axis and z-axis at the fracture surface, respectively. These dimensions represent a reasonable region to capture the damage distribution while ensuring consistent measurements. The data in Fig. 3e show that the damage maps are highly dependent on the applied pre-stretch.

When approaching the fracture surface, the activation ratio φy increases well beyond the value φb = 0.02% that is observed in the bulk of the sample (cf. Fig. 3e), which indicates significant covalent bond scission caused by the cutting process. Accordingly, we define the damage zone as the region where the activation ratio exceeds this threshold and plot its depth d in Fig. 4a as a function of pre-stretch.

a The damage zone depth d and (b) the dimensionless damage surface density \(\bar{\Sigma }\) in the cutting edge as a function of the applied stretch ratio λ. The error bars for each data point represent the standard deviation of the fluctuations over several hundred independent depth profiles acquired on at least three different samples.

When further integrating the depth profile φy in the remaining y-direction, we can estimate the average surface density \({\Sigma }_{\exp }\) of broken bonds per unit area of fracture surface:

where \({\nu }_{x}\) is the volume density of crosslinks for an affine network model, estimated in Supplementary Note 2. This is the appropriate observable to be compared with the measured cutting/fracture energy. Although Sylgard 184 contains small amounts of silica fillers that influence its properties25,30, its polymer network structure is similar to pure PDMS. Thus, it is treated as an ideal PDMS polymer chain when estimating the number of broken bonds and in the following theoretical calculations.

The Lake and Thomas model31 provides a physical theory of the fracture energy of an affine polymer network, where all the chains crossed by an ideal fracture plane with density \({\Sigma }_{{LT}}\) are broken. We will consider here the dimensionless damage surface density \(\bar{\Sigma }\):

Since the Lake-Thomas model corresponds to a single layer of broken bonds in a perfect network, we can interpret the dimensionless damage surface density \(\bar{\Sigma }\) as an effective number of broken layers20 (cf. Supplementary Note 2 for an estimation of the orders of magnitude).

Figures 4a and b represent, respectively, the variation of the damage zone depth d and dimensionless surface density of broken bonds \(\bar{\Sigma }\) as a function of the applied stretch for the same samples as in Fig. 2. Note that both measurements are a representation of the activated mechanophores. In the data from Region I, we can observe enhanced damage on the fracture surfaces corresponding to strong friction on the side of the blade. We will neglect this region here since the aim of the paper is comparing regions II and III for clean cutting and pure fracture, respectively. We can remark that in regions II and III, both the damage depth d and the damage surface density \(\bar{\Sigma }\) increase with the level of applied pre-stretch, consistent with the observed increase of the cutting/fracture energy in Fig. 2d. The depth of the damage region d changes from 20 to 40 µm, while the dimensionless damage surface density \(\bar{\Sigma }\) changes from 2.0 to 4.3 network layers (corresponding to a real surface density \({\Sigma }_{\exp }\) increasing from 8.1·1017 to 1.7·1018 broken bonds·m-2), and the crack extension energy changes from 260 to 540 J·m-2. This good correlation is even clearer when we plot the measured crack extension energy as a function of the measured surface density of broken chains, as shown in Fig. 5a. The pure fracture appears as a coherent limiting case of the clean cutting curves with variable applied pre-stretch. Interestingly, the damage zone depth d is proportional to (but much smaller than) the observed blunting radius rb of the crack (Fig. 5b), suggesting that a larger level of blunting causes more extensive molecular damage.

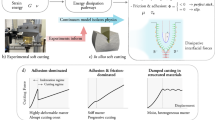

a The relationship between the cutting/fracture energy and the surface density of broken bonds. b The relationship between the blunting radius rb and damage zone depth d. c Photos of the cutting and tearing process (scale bar: 1 mm) and the sketch of the damage mechanism: the contribution of the cutting blade allows the propagation of the fracture for a lower applied stretch and a reduced radius of blunting of the tip. The reduction of the volume where large strains are experienced in front of the crack tip results in the reduction of the number of chains broken per unit fracture surface area and, thus, of the crack extension energy.

Molecular model for the cutting energy

The Lake-Thomas model has long been the most widely accepted molecular model for the fracture of elastomers, relating the threshold fracture energy (without viscoelastic dissipation) to the cost of breaking all the polymer chains crossing a well-defined fracture plane, i.e., a single layer of the crosslinked polymer network31. Classic models have always considered that molecular fracture was not dependent on strain rate or temperature18.

Recent investigations of the fracture mechanisms with mechanophores have, however, proven that the surface density of broken bonds near the fracture surface of an elastomer depends on the test conditions (rate and temperature notably20) and on the network architecture, as well as the presence or absence of fillers. In non-threshold conditions, the molecular damage can spread over a thickness of the order of tens of microns, which is much larger than the nanometric mesh size of the polymer network. The measured values of activated mechanophores correspond to the rupture of a larger number of chains, which is equivalent of several full mesh layers20,23,32,33.

This increase in damage zone depth was rationalized by considering that common networks are intrinsically polydisperse in strand length and strand conformation. Some shorter or more extended chains can reach their maximum stretch at some micrometric distance away from the crack tip, even if the average strain is lower there. Fracture mechanics states that the width of the region that experiences strains exceeding 100% around a propagating crack is driven by the blunting radius rb, which scales as Γ/Ε (~ 100 µm for PDMS)34. Although this is one order of magnitude larger than the typical 10 µm thickness of the measured damage zone, it suggests that the damage zone depth d should be proportional to the fracture energy. This is also a good guide to understand why cutting is easier than tearing.

When comparing pure fracture and combined stretch/cutting, the crack can be propagated with a reduced pre-stretch of the elastomer (more than a factor of two), since the contribution of the work of cutting reduces the stretch energy required to reach the Griffith criterion. According to our observations, the role of the blade is to limit the size of the large strain region and, hence, to reduce the density of bonds that need to be broken and, therefore, the crack extension energy.

Discussion

This investigation provides the first mapping of the extent of molecular damage occurring during the combined cutting and stretching of elastomers. The total cutting energy was shown to be proportional to the number of broken bonds per unit area (quantified by mechanophores), much like in fracture propagation. However, the use of a blade allows to reduce the amount of stretch required for fracture propagation. This reduces, in turn, the blunting radius of the crack tip and, thus, the volume where the material undergoes large strains that can induce the failure of overloaded chains in the network. In other words, using a blade localizes the bond-breaking region to a smaller scale than simple tearing, thus reducing the total energy required for crack extension.

Although we used a relatively brittle elastomer model system (Γ ∼ 500 J m−2) to facilitate the incorporation of mechanophores, the reduction of the extent of bond scission achieved with a sharp blade should be quite general, and all the more effective for the case of tougher and more viscoelastic elastomers such as styrene-butadiene rubber (SBR) (Γ ∼ 10–50 kJ m−2)35, multiple network elastomers (Γ ∼ 10 kJ m-2)23, or filled rubbers (Γ ∼ 10–100 kJ m-2)36 or even thermoplastic elastomers (Γ ∼ 140 kJ m−2)37, where the damage zone remains large even under threshold conditions. In these tough materials, the blunting associated with fracture propagation can be huge, and the spread of the damage over a large scale underpins their very high fracture toughness. By limiting blunting, the blade is expected to reduce both the extent of damage and the overall fracture energy, an area that warrants further investigation. However, a key challenge in this research approach lies in the need to develop specific chemical strategies for incorporating mechanophores into different materials38 while ensuring minimal impact on their mechanical properties. In addition, the application of mechanophores in other soft materials, such as tough hydrogels, remains constrained by their low emission efficiency in aqueous environments.

Understanding the relationship between network architecture and the varying degrees of molecular damage undercutting and tearing conditions can play a crucial role in optimizing material design. By tailoring network structures, it becomes possible to achieve specific and independent resistance to these different fracture modes, enabling the development of materials with enhanced durability and performance. This knowledge is particularly valuable in applications such as protective gears, biomedical devices, soft robotics components, and high-performance elastomers used in tires and industrial seals, where resistance to both sharp incisions and gradual tearing is essential.

Methods

Sample preparation

The mechanofluorescent π-extended anthracene maleimide probe, also known as a Diels-Alder cross-linker (DACL), was incorporated into PDMS (2 mol·m−3) as a crosslinker via hydrosilylation of Sylgard 184 (10:1 base: curing agent). The synthetic procedures and characterization of the DACL probe are described in detail in a previous work20. The preparation procedure of the PDMS sample was as follows: 5 mg of the DACL mechanophore was dissolved in 1 g of dichloromethane (Sigma Aldrich) and thoroughly mixed with 4 g of PDMS base and 0.4 g of PDMS curing agent for 10 min. The resulting viscous solution was poured into a 1 mm-thick glass mold, separated by a polyethylene terephthalate film to ensure easy demolding. The mold was placed in a vacuum tank for 30 min to remove residual dichloromethane solvent. Finally, the sample was cured by heating the mold at 60 °C for 5 h.

Pure-shear Cutting experiment

A rectangular thin elastomer layer (with length L much larger than the width h0) is secured on the x-y plane (Fig. 1a) with its longer edge fixed parallel to the x-axis using two movable clamps. A constant and homogenous stretch λ = h/h0 is applied along the width h0, leading to what is called the pure-shear fracture propagation test. To combine stretching and cutting, a custom-built fixture holds the pre-stretched pure-shear sample orthogonally to a blade centered at the middle of the stretched sample (Supplementary Fig. 2). A pre-notch is introduced to the sample using a sharp blade. The blade is then displaced at a constant velocity V = 0.2 mm·s−1 while the applied force is recorded by a load cell. A side camera captures the images of the strained sample, as shown in Fig. 3d, to check steady-state propagation and measure the blunting radius rb of the crack opening profile. We used Feather Platinum coated blades with a sharpness radius ≈ 120 nm, as measured in Supplementary Fig. 3. A new blade was used for each sample.

Visualization of damage by bond scission

The surfaces of the fractured specimens underwent cleaning with ethanol and optical paper to remove any impurities. The π-extended anthracene fluorophores were excited using a 405 nm laser. The fluorescent emission from these fluorophores was recorded within the range of 420–530 nm. Fluorescence images were captured within the sample at a depth of 100 µm from the surface using a customized Nikon AZ-100/C2 + confocal microscope in a single section normal to the fracture surface. This microscope was equipped with an AZ Plan Fluor 5× objective lens with a focal length of 15 mm. The optical magnification was set to × 2, resulting in raw images of dimensions 1024 × 1024 pixels, with a pixel size of 1.63 μm. 3D scans were collected starting from the specimen surface, specifically the plane of maximum intensity. These scans were conducted through a depth of 200 μm, with a step size of 10 μm. This process allowed for the 3D mapping of the damage due to bond scission, as reported in Fig. 3.

Data availability

Additional information related to the article is provided in the Supplementary Information. The data presented in both the main paper and supplementary information have been deposited in the OSF database (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/RZWKE). All data are also available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Lake, G. & Yeoh, O. Measurement of rubber cutting resistance in the absence of friction. Int. J. Fract. 14, 509–526 (1978).

Lake, G. & Yeoh, O. Effect of crack tip sharpness on the strength of vulcanized rubbers. J. Polym. Sci., Part B Polym. Phys. 25, 1157–1190 (1987).

Gent, A., Lindley, P. & Thomas, A. Cut growth and fatigue of rubbers. I. The relationship between cut growth and fatigue. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 8, 455–466 (1964).

Gent, A. & Wang, C. Cutting resistance of polyethylene. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 34, 2231–2237 (1996).

Lechenault, F., Ramdane, I., Moulinet, S., Roman-Faure, M. & Ciccotti, M. Soft coring: How to get a clarinet out of a flute? Extrem. Mech. Lett. 61, 101976 (2023).

Zhang, B., Shiang, C. S., Yang, S. J. & Hutchens, S. B. Y-Shaped Cutting for the Systematic Characterization of Cutting and Tearing. Exp. Mech. 59, 517–529 (2019).

Zhang, B. & Hutchens, S. B. On the relationship between cutting and tearing in soft elastic solids. Soft Matter 17, 6728–6741 (2021).

Gent, A., Lai, S., Nah, C. & Wang, C. Viscoelastic effects in cutting and tearing rubber. Rubber Chem. Technol. 67, 610–618 (1994).

Zhan, S., Wagoner Johnson, A. & Hutchens, S. Y-Shaped cutting of soft solids: History and best practices. Exp. Mech. 64, 1185–1198 (2024).

McCarthy, C. T., Annaidh, A. N. & Gilchrist, M. D. On the sharpness of straight edge blades in cutting soft solids: Part II–Analysis of blade geometry. Eng. Fract. Mech. 77, 437–451 (2010).

McCarthy, C. T., Hussey, M. & Gilchrist, M. D. On the sharpness of straight edge blades in cutting soft solids: Part I–indentation experiments. Eng. Fract. Mech. 74, 2205–2224 (2007).

Goda, B. A., Ma, Z., Fregonese, S. & Bacca, M. Cutting soft matter: scaling relations controlled by toughness, friction, and wear. Soft Matter 20, 6016–6022 (2024).

Mora, S. & Pomeau, Y. Cutting and slicing weak solids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 038002 (2020).

Li, M., Karnal, P., Lu, Y., Hui, C.-Y., Jagota, A. Slicing of a soft solid. J. Chem. Phys. 159, 114704 (2023).

Liu, Y., Hui, C.-Y. & Hong, W. A clean cut. Extrem. Mech. Lett. 46, 101343 (2021).

Robertson, C. G., Stoček, R. & Mars, W. V. Fatigue Crack Growth in Rubber Materials: Experiments and Modelling. Adv. Polym. Sci. 57–83 (2020).

Mars, W. V., Robertson, C. G., Stocek, R. & Kipscholl, C. Why cutting strength is an indicator of fatigue threshold. Constitutive Models for Rubber XI. 351–356 (CRC Press, 2019).

Creton, C. & Ciccotti, M. Fracture and adhesion of soft materials: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 79, 046601 (2016).

Ju, J. et al. Real-time early detection of crack propagation precursors in delayed fracture of soft elastomers. Phys. Rev. X 13, 021030 (2023).

Slootman, J. et al. Quantifying rate-and temperature-dependent molecular damage in elastomer fracture. Phys. Rev. X 10, 041045 (2020).

Morelle, X. P., Sanoja, G. E., Castagnet, S. & Creton, C. 3D fluorescent mapping of invisible molecular damage after cavitation in hydrogen exposed elastomers. Soft Matter 17, 4266–4274 (2021).

Sanoja, G. E. et al. Why is mechanical fatigue different from toughness in elastomers? The role of damage by polymer chain scission. Sci. Adv. 7, eabg9410 (2021).

Slootman, J., Yeh, C. J., Millereau, P., Comtet, J. & Creton, C. A molecular interpretation of the toughness of multiple network elastomers at high temperature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2116127119 (2022).

Rencheck, M. L. et al. Identifying internal stresses during mechanophore activation. Adv. Eng. Mater. 24, https://doi.org/10.1002/adem.202101080 (2021).

Clough, J. M., Creton, C., Craig, S. L. & Sijbesma, R. P. Covalent bond scission in the mullins effect of a filled elastomer: Real‐time visualization with mechanoluminescence. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 9063–9074 (2016).

Gula, I. A., Karimi-Varzaneh, H. A. & Svaneborg, C. Computational study of cross-link and entanglement contributions to the elastic properties of model PDMS networks. Macromolecules 53, 6907–6927 (2020).

Wang, J., Zhu, B., Hui, C.-Y. & Zehnder, A. T. Delayed fracture caused by time-dependent damage in PDMS. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 181, 105459 (2023).

Genesky, G. D. & Cohen, C. Toughness and fracture energy of PDMS bimodal and trimodal networks with widely separated precursor molar masses. Polymer 51, 4152–4159 (2010).

Long, R., Hui, C.-Y., Gong, J. P. & Bouchbinder, E. The fracture of highly deformable soft materials: A tale of two length scales. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 12, 71–94 (2021).

Lee, J. N., Jiang, X., Ryan, D. & Whitesides, G. M. Compatibility of mammalian cells on surfaces of poly (dimethylsiloxane). Langmuir 20, 11684–11691 (2004).

Lake, G. J. & Thomas, A. G. The strength of highly elastic materials. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 300, 108–119 (1967).

Wang, S., Panyukov, S., Craig, S. L. & Rubinstein, M. Contribution of unbroken strands to the fracture of polymer networks. Macromolecules 56, 2309–2318 (2023).

Wang, S., Panyukov, S., Rubinstein, M. & Craig, S. L. Quantitative adjustment to the molecular energy parameter in the Lake–Thomas theory of polymer fracture energy. Macromolecules 52, 2772–2777 (2019).

Hui, C.-Y., Bennison, S. & Londono, J. Crack blunting and the strength of soft elastic solids. Proc. R. Soc. Lond., Ser. A 459, 1489–1516 (2003).

Gent, A. Adhesion and strength of viscoelastic solids. Is there a relationship between adhesion and bulk properties? Langmuir 12, 4492–4496 (1996).

Morishita, Y., Tsunoda, K. & Urayama, K. Universal relation between crack-growth dynamics and viscoelasticity in glass-rubber transition for filled elastomers. Polymer 179, 121651 (2019).

Scetta, G., Selles, N., Heuillet, P., Ciccotti, M. & Creton, C. Cyclic fatigue failure of TPU using a crack propagation approach. Polym. Test. 97, 107140 (2021).

Cartier, A. et al. Labeling a polydiene elastomer with a π-extended mechanophore with a facile and low temperature synthetic route. Macromolecules 57, 8712–8721 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The work was financially supported by the ERC Grant agreement AdG no. 695351 (CHEMECH, received by C.C.) and D.Z. was supported by a Chinese Scholarship Council fellowship (File No.202106320020). We thank S. Hutchens and C. Davis for insightful discussions. We thank J. Comtet for important insights in the quantification of mechanophore maps. We thank L. Olanier and B. Bresson for contributing to the custom setup and confocal imaging techniques.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.C., M.C., T.N., and D.Z. conceived the idea. D.Z. performed the experimental investigation. D.Z. and A.C. prepared mechanophore-labeled samples. D.Z, M.C., and F.L. developed the experimental devices and mechanical modeling. D.Z., C.C., M.C., and T.N. developed the molecular interpretations. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, D., Cartier, A., Narita, T. et al. Why cutting is easier than tearing elastomers. Nat Commun 16, 3203 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58483-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58483-1