Abstract

‘Green growth’ is a cornerstone of global sustainability debates and policy agenda. Although there is no consensus definition, it is commonly associated with the absolute decoupling of economic growth from greenhouse gas emissions, which is indeed occurring in high-income countries today. Nevertheless, green growth thus defined could be insufficient to reach global mitigation goals. Here we examine long-term historical data and develop a framework to identify global, regional, and national patterns of decoupling between economic output and anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. We show that 60% of cumulative fossil-fuel CO2 reduction during 1820–2022 took place under recessions rather than during instances of green growth, with just 5 global crises accounting for about 40%. While in the last 50 years national episodes of green growth became more common, they have not been sustained over time. Crucially, historical episodes compatible with sustained growth and the required emission reductions are anecdotal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

“Green growth” is a cornerstone of global sustainability debates and policy agenda. While it still lacks a precise consensus definition, its popularity hinges on its promise to reconcile two apparently conflicting paths into the future: sustaining economic growth while, at the same time, reducing the environmental footprint of the global economy. The main institutional promoters of green growth—the United Nations1, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)2,3, and the World Bank4— usually associate it to “absolute decoupling”: a fall in levels of environmental impacts in a context of gross domestic product (GDP) expansion5,6.

Nevertheless, the very feasibility of green growth is hotly debated7,8. Its advocates argue that a combination of efficiency gains through technological change, energy transition towards cleaner sources, and structural change led by cleaner sectors will make economic growth an ally of environmental sustainability rather than a threat to it9,10,11,12. This techno-optimistic idea has long been present in the literature, most famously in the Environmental Kuznets Curve hypothesis13,14,15. Nevertheless, skeptics argue that green growth, even defined conservatively as absolute decoupling, may not be feasible for all environmental impacts16,17,18 and, even if it was, its achievements have proven reversible19 and might be too little too late to keep humanity within a “safe operating space6,8,18,20.” Furthermore, absolute decoupling does not mean sufficient decoupling: “genuine green growth” requires not simply any reduction of environmental impacts but a reduction fast enough to keep us within planetary limits6,18,20.

Both advocates and skeptics of green growth base their positions—explicitly or implicitly—on a certain reading of history. Techno-optimists look to the past and find that instances of absolute decoupling have become more common, especially in high-income countries21,22,23. Critics, instead, view history as evidence of economic growth’s unavoidable and relentlessly growing ecological footprint16,17,18. In “the past,” they claim, “the two things have gone hand in hand8.” But what does history actually tell us? How often have modern human societies managed to decouple economic growth from environmental impacts? On what scale and under which social and economic circumstances? And have these mitigation achievements proved persistent through time?

Our study examines coupling and decoupling trajectories over the last two centuries at a global, regional, and national level. We focus on comparing emission reductions achieved during economic expansion (i.e., “green growth”) with those that occurred during economic recessions. We also consider the reversibility of these reductions. To do so we construct a database from a range of secondary sources containing evidence on greenhouse gas emissions (GHGe, distinguishing fossil-fuel CO2 emissions from others)24,25,26, population and GDP27. Following Tapio’s methodology28, commonly used to assess decoupling trends22,29, we distinguish between six patterns in the relationship between economic growth and GHGe: (i) dirty growth, when GHGe grow faster than GDP; (ii) coupled growth, when both GHGe and GDP grow at similar rates; (iii) relative decoupling, when the economy grows faster than GHGe; (iv) absolute decoupling when GDP grows and GHGe decrease; (v) recessive emission reduction, when both emissions and the economy shrink; and (vi) dirty recessions when GDP decreases but emissions go up. Our analysis reveals that globally, emissions and GDP grew at similar rates until the early twentieth century, followed by an overall pattern of weak decoupling, notwithstanding substantial variation across time and space. National episodes of absolute decoupling have indeed become more frequent, yet they are neither new nor exclusive to high-income countries, particularly when considering all emissions rather than only fossil-fuel CO2 emissions. Finally, a significant portion of cumulative fossil-fuel CO2 reduction occurred during recessions rather than green growth periods, suggesting that historical episodes of sustained green growth have not been the primary source of these reductions.

Results

Overview

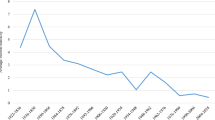

The Industrial Revolution ushered in an era of growing GDP, energy use and GHGe, all of which expanded towards unprecedented levels (Fig. 1a). While the overall trajectory of these variables is somewhat similar in the long run, if we look more closely their historical paths differ at crucial junctures (Fig. 1b). During the nineteenth century and until the First World War, global GDP and emissions were very much “coupled”: they grew at a similar yearly cumulative rate (~1.4%). In other words, the carbon intensity of the global economy, i.e., GHGe per unit of GDP, remained relatively stable (Supplementary Fig. 1a). During the interwar period, between 1914 and 1945, we can see the first global decoupling between GDP and GHGe. Global economic growth maintained its pace, despite relative stagnation in the West (as referred to in the historical regions of the Maddison Project), while emissions slowed down, mainly because the largest emitters (i.e., Western countries, Supplementary Fig. 2) reduced their fossil-fuel emissions. In the decades following the Second World War, both economic growth and emissions accelerated dramatically. Economic historians refer to this period as the “golden age of (Western) economic growth30,” while in the environmental literature, it is known as the era of the “great acceleration” of resource use and environmental impacts31. In this context, the global economy grew significantly faster than emissions (3.8% compared to 2.3%), resulting in decades of relative decoupling, as the carbon intensity of the economy fell substantially. Since 1990, both economic growth and emissions slowed down relative to the post-war era, although their rate of growth remains above pre-Second World War trends. Emissions have slowed down to a larger extent than GDP, and so the carbon intensity of the global economy has decreased at an unprecedented pace (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Relative decoupling persisted, as GDP continued to grow faster than emissions, but much like in the preceding periods, there was no evidence of absolute decoupling at the global level.

a Normalized long-term trend (1820 = 1). b Annual growth rates in selected periods. Supplementary Fig. 4 provides an estimate including an uncertainty range for emissions.

Beneath these global patterns, there is of course substantial regional variation (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). But overall, both the global economy and its climate footprint have extraordinarily expanded over the last two centuries. Until the early twentieth century, they did so in tandem; since then, they have grown at different rates, with GDP outpacing emissions, allowing for a fall in the carbon intensity of economic activity (Supplementary Fig. 1a). This has resulted in emission savings, but has not avoided an absolute increase in total emissions.

Patterns of decoupling

Global and regional decoupling patterns look remarkably different if we count only fossil-fuel CO2 emissions (as the literature most often does) or if we instead consider all GHGe. Considering non-fossil-fuel emissions, dominated by agriculture, forestry, and other land-use emissions (hereafter “land-based emissions”), is crucial for a deeper understanding of economic growth’s impact on the climate, as they account for about 40% of cumulative GHGe since c.1820 (Supplementary Fig. 5). Land-based emissions are also related to economic growth, even if less clearly so than in the case of fossil fuels32, as they also depend heavily on resource endowments (e.g., the remaining stock of primary forest) and large spikes are sometimes caused by exceptional events (such as forest fires)33. Moreover, the evolution of land-based and fossil-fuel emissions are closely intertwined: the expansion of the agricultural frontier was made possible by fossil fuels, while in other contexts changes in energy systems have allowed for reductions in land-based emissions34,35.

When considering only fossil-fuel CO2 emissions (Fig. 2a) we find that most of the world experienced “dirty growth” (emissions expanding faster than GDP) until c.1945. Since then, several countries, especially but not only in the West, entered a relative decoupling path, as their economies grew faster than their GHGe, i.e., decreasing their carbon intensity. In the last few decades, we observe that most of the rest of the world has also transitioned to a relative decoupling pattern, while some Western economies show evidence of “absolute decoupling,” i.e., they are reducing their emissions while their GDP continues to expand. The scale of absolute decoupling in Western economies remains, however, insufficient to meet the Paris climate targets, which would require a yearly emission reduction of about 6% until 2050 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

a Diagram of identified Tapio patterns relating GDP growth and GHGe; b, c Regional patterns of Tapio-based coupling and decoupling in 5-year periods; d, e National patterns of decoupling in selected periods. In the case of countries without GDP data in 1945, the value for 1950 is used. All country-level data are provided in Supplementary Fig. 8.

This relatively recent and mostly Western pattern of absolute decoupling in fossil-fuel CO2 emissions does not hold when we consider all GHGe (Fig. 2b). When doing so, we find that both relative and absolute decoupling are not historically new nor essentially Western. Already in the nineteenth century, many countries achieved substantial economic growth alongside emission mitigation, mainly due to slowing deforestation rates in a historical context where fossil-fuel CO2 emissions were marginal. Figure 3 shows how a large part of national instances of absolute decoupling were caused by changes in land-based emissions, especially in countries in Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, and South and South-East Asia (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 6). Nevertheless, when considering all emissions, we still find evidence of a global transition towards relative decoupling in the late-twentieth century, with spots of absolute decoupling in recent years, although not just in Western economies but also in low-income regions. Indeed, the fastest reductions in the carbon intensity of GDP are found in Sub-Saharan Africa in recent years (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Annual observations for a all country-years and b selected countries. National figures for all countries >10 million inhabitants are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6.

As suggested in other studies8,19, the incidence of absolute decoupling tends to decrease when emissions are counted from a consumption-based perspective, i.e., including emission transfers through international trade36. According to our results, when considering consumption-based (rather than production-based) emissions, the number of country-year instances of absolute decoupling decreases by 49% between 1991 and 2021 for the case of CO2 fossil-fuel emissions, the only period and the only gas category for which we have data on national carbon footprints. Nevertheless, we still find that there is a trend towards a higher prevalence of decoupling (both absolute and relative) in recent decades regardless of how we count emissions (Supplementary Fig. 7).

In short, global, regional, and also national trajectories (see Supplementary Fig. 8) suggest that as economies developed over the long run, cases of relative decoupling (and, more recently, absolute decoupling) became more common and more intense, especially when counting only fossil-fuel CO2 emissions (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for evidence on the rate of growth of carbon intensity). And yet, the scale of these historical decoupling instances remains relatively small when compared to the rarer but much more consequential emission reductions during major economic recessions. Let us look more closely at the contrast between green growth episodes and instances of falling emissions under recessions.

Patterns of GHGe reduction

In most (72%) historical instances (country-years) when emissions fell, GDP grew, thus achieving absolute decoupling. Some of these were due to changes in land-based emissions, which in many cases were not a result of technological or structural change, but mainly a consequence of deforestation rates slowing down after a period of large-scale land-use change37. In sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and South and South-East Asia, these cases account for more than 80% of historical emission reduction (Fig. 4a). Green growth accounts for 60% of cumulative global emission reduction and 40% if we only consider fossil-fuel CO2 emissions (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 1). However, only 32% and 13% of reductions, respectively, can be attributed to what we term genuine green growth: absolute decoupling large enough for an emission reduction compatible with the IPCC’s 2° scenario38 and economic growth sufficiently fast to meet the OECD (i.e., GHGe falling at −3.4% per annum and GDP expanding at 2.6% per annum; recent studies take similar benchmarks)39. These figures are even lower, 26% and 6% if we consider the IPCC’s 1.5° scenario. Furthermore, if, as some studies suggest40,41,42, the potential of negative emissions technologies—such as Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS)—is more limited than assumed by the main scenarios, achieving these targets would require an even steeper reduction in emissions. With this assumption, instances of genuine green growth in the past become merely anecdotal (Supplementary Table 1). That said, calling a 2° or even a 1.5° scenario “genuinely green” might imply that we consider that level of global warming to be safe or acceptable—we do not43. In choosing these boundaries our intention is to provide a lower-bound threshold, i.e., an easy test for green growth (for more detail see “Methods”; for a sensitivity analysis see Supplementary Table 1).

a Cumulative emission reduction by regions including all GHGe and distinguishing land-based emissions. b Global cumulative emission reduction including all GHGe and distinguishing land-based emissions; considering only fossil-fuel emissions; and identifying the impact of global crises. c Annual fossil-fuel emission reduction (excluding land-based emissions) distinguishing between recessive instances (negative GDP growth) and green growth (positive GDP growth).

Cases of emission decrease during recessions, where GHGe and GDP fall at the same time, are less frequent: only 22% or 28% of the country-year instances of emission reduction, again counting all gases or only fossil-fuel CO2 respectively. But despite being rarer, they tend to result in much sharper falls of GHGe and thus collectively account for at least as much historical emission reduction (40% counting all GHGe and 60% counting only fossil-fuel CO2) as all green growth episodes combined (Fig. 4). These emission-reducing recessions have generally been the result of global or local disruption. As shown in Fig. 4, just during five critical global episodes—the World Wars, the financial crises of 1929 and 2008, the oil crises of the 1970s, and the coronavirus pandemic of 2020—combine to explain 67% of reductions in fossil-fuel CO2 during recessions over the last 200 years (Fig. 4b). There were also national crises that triggered similarly large-scale emission reductions (Fig. 3b for selected countries; Supplementary Fig. 6 for all countries). In Russia, substantial falls in emissions bookend the twentieth century, following the civil war and the collapse of the USSR. In China, during the Great Famine of 1961 (a fall of −16% in emissions). Germany, a major theater of world war, saw its emissions fall by 73% in 1945. The United States experienced emission reductions of around 10% per annum during the Depression (1931–1933), as well as for several years during both World Wars, and under the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020.

It should be noted that emission reductions in contexts of recession are not only due to the impact of economic contraction itself but can also result from falls in carbon intensity from technological improvements and structural change. According to our calculations, 63% of all emissions reduction (50% if considering only fossil-fuel CO2) in contexts of recession are explained directly by the fall in GDP per capita, whereas the rest is due to efficiency gains, that is, to the fall in carbon intensity (see Supplementary Table 2).

Reversibility

Recent studies, albeit covering only very short periods, have shown absolute decoupling to be reversible16,19, an issue highlighted by the IPCC38. Our results also reveal the episodic nature of green growth experiences in the past. The longest episodes of absolute decoupling have all faced an eventual backlash. The United Kingdom recently achieved 7 years of absolute decoupling, brought to an end during the Covid-19 pandemic. Decades before, France had also succeeded in achieving 7 consecutive years of absolute decoupling in 1979–1986, but this trend also came to an end. The same happened with other Western countries after a few years of green growth: Japan (2014–2018), Germany (1990–1994), and Belgium (2005–2007). Even if the long-run gains produced by absolute decoupling are sometimes persistent (i.e., countries often do not go back to their emission levels after an episode of green growth), history suggests that sustaining absolute decoupling rates over more than a few years is extremely difficult (Fig. 5). In fact, episodes of green growth are sometimes as short-lived as recessions. For their part, emission reductions during recessions have also proven reversible. Economic contraction in the aftermath of the fall of the USSR led to several countries experiencing consecutive years of recessive emission reduction, such as Ukraine (8 years), followed by 2 years of absolute decoupling and then a decade of growing emissions. Likewise, North Korea experienced 8 consecutive years of recessive emission reduction between 1991 and 1998. More recently, Venezuela had at least (the quality of the GDP data has been contested) 7 straight years of recessive emission reduction (2014–2020) and Syria experienced 6 years of consecutive emission reduction in the context of war (2009–2015).

a National episodes of absolute decoupling. b National episodes of emission reduction during recessions, 1950–2020. Column one selects the eight countries with the highest number of episodes in the period. Supplementary Fig. 9 provides detailed information for all world countries.

Discussion

Can we sustain economic growth and at the same time reduce its environmental impacts to keep humanity within a “safe operating space?” This question, one of the most important for our collective future, still lacks a consensus answer7,44. Our results can inform that debate in the following ways.

First, historical data chart our direction of travel. Continuing to expand output while reducing absolute emission levels requires that we drastically reduce the carbon intensity of the global economy (i.e., GHGe per unit of GDP)6,20,45 and, additionally, that rising economic activity (encouraged by these efficiency gains) does not result in a decrease in absolute emissions—thus avoiding the “rebound effect46,47.” Does history suggest we are moving in that direction? During the first century and a half following the Industrial Revolution and its initial spread in the West, global economic output, resource use, and emissions were coupled and grew at roughly the same pace. This means that, at the global scale, technological change did not result in a significant fall in emissions per unit of GDP, except (partially) during the interwar years. Some countries were already experiencing instances of decoupling throughout the nineteenth century, although these were mostly explained by the slowing down of deforestation processes rather than by substantial emission-mitigating technological change. It was only after World War II that a more generalized pattern of relative decoupling emerged. New technologies and their global diffusion, as well as service-oriented structural change in advanced economies, substantially reduced the energy required per unit of output48,49,50. Furthermore, the transition from coal to oil and gas, and more recently towards renewable energy sources, reduced the GHG emitted per unit of energy, thus decoupling (to an extent) emissions from energy use51.

The global economy has become remarkably more efficient in environmental terms than it was in the Industrial Revolution era because it uses less energy per unit of output and contemporary energy sources themselves are much cleaner52. Nevertheless, the overall scale of production has increased dramatically, leading to a continued increase in absolute emission levels rather than savings and mitigation, much like Jevons famously predicted when studying the demand for coal in the United Kingdom in the mid-nineteenth century53. In short, in a long run we might be traveling in the right direction, but far too slowly.

Second, our results contribute to understanding whether present “green growth” is indeed unprecedented. Recent years show increasingly common episodes of absolute decoupling at a national and even at a regional level, especially in high-income countries21,22,23,45. Are these episodes truly unprecedented and hence able to break from the slow-moving trends we just described? Our analysis shows that instances of green growth (defined as absolute decoupling) have been recurrent for a long time, but they have also proved invariably reversible. While technological improvements do have long-lasting effects (the emission savings are locked-in) if absolute decoupling is to avoid a “rebound effect,” then efficiency gains must be continuous and also large enough to compensate for increases in economic output. What we call genuine green growth involving substantial mitigation and robust economic growth (as defined by the IPCC 2° scenario and the OCDE growth projections for 2050) is uncommon in modern history and accounts for a small part of cumulative global mitigation. If green growth is expected to achieve not just any absolute decoupling, but one large enough to meet economic growth goals within planetary boundaries6,54,55, then it must represent a break with preceding trends.

Beyond the formidable technical challenges involved, such a transition would need to meet the requirements of fairness. Not every country, and not every person56, has contributed equally to climate change (Supplementary Fig. 3). Acknowledging the principle of “shared but differentiated responsibilities,” each country’s remaining fair share depends on historical cumulative emissions, and so efforts should also be diverse57,58. Moreover, such a transition would need to take into account not just climate impacts, which are the only ones we examine in this study54, but also other environmental impacts which can be equally harmful to human wellbeing.

Third, our results highlight emission reductions during economic recessions. Rather disturbingly, history tells us that emission reduction in the past owes at least as much (if not more) to recessions than to episodes of genuine green growth. Modern economic development and anthropogenic GHGe have been historically so closely intertwined that most fossil-fuel emission reduction has taken place during times of contraction rather than expansion of economic activity. Importantly, this does not imply that to save the planet we should hope for socio-economic crises: recessions reduce emissions primarily because of the conjunctural slowdown of economic activity, not because they make the structure of output or employment “greener.” If they did, their impact on emissions would be sustained through time, and the data show otherwise. Instead, what the historical mirror suggests is that economic growth as we know it since industrialization is by default coupled with rising emissions. This does not entitle us to predict that the future will follow this pattern. But if genuine green growth becomes the new norm, it will enter the archives as a discontinuity in historical development.

Methods

Database

Our database includes annual series at the national, regional, and global levels of GHGe, energy use, GDP, and population between 1820 and 2020. These data have been collected from existing datasets and then harmonized for our analysis. The details of the sources and our harmonization are as follows:

Emissions of CO2 from fossil fuels are taken from the Global Carbon Project (GCP, version 2023v43)24,59, which distinguishes between kinds of fuel, cement, flaring gases, and other gases. The GCP estimates rely on the historical series of Carbon Dioxide Information and Analysis Center—Fossil Fuels (CDIAC-FF) until 201760, which they modified to ensure consistency. The CDIAC-FF series are extended up to the present using the rates of growth of energy consumption offered by BP, following Mhyre et al.’s proposal61. CGP disaggregates emissions associated with “international trade” (code XIT), which we allocate to each country proportionally to its oil-based emissions. All CGP estimates are available on an annual basis for the period 1750-2022 at the national level.

Land use, land-use change, and forestry (LULUCF) emissions are taken for the period 1850–2022 from the recent estimates by Jones et al.25. Their study offers an annual series based on the average of three bookkeeping estimates also used by the GCB62,63,64. These include emissions caused by vegetation loss and soil organic carbon in processes of land-use change, as well as wood harvesting, peat burning, and drainage. To extend the series back to 1820, we rely on the Land Use Harmonization dataset (LUH2)65, which offers gridded data on biomass C stocks since 850. We extracted yearly country stocks from this source and used the annual variation in these stocks to project Jones et al.’s back from 1850 to 1820.

CH4 and N2O emission data are taken from PRIMAP-Hist (v.2.5.1)26,66, which provides annual estimates at the national level between 1750 and 2022. This database distinguishes between emissions associated with energy; industrial processes and product use; agriculture and livestock; and waste and others. PRIMAP-hist estimates rely on several datasets, notably CDIAC, BP, FAO, EDGAR, and UNCFF. A detailed description of these sources and the estimation procedures can be found in the following references66. In particular, we work with the HISTTP scenario in which third-party data are preferred over country-reported data, as other studies have shown them to be more reliable25.

Throughout the article, when we speak of “fossil-fuel emissions,” we include CO2 fossil-fuel emissions retrieved from CGP as well as the CH4 and N2O emissions from the energy sector retrieved from PRIMAP-hist. When we say “land-based emissions” we include CO2 LULUCF emissions retrieved from Jones et al. as well as CH4 and N2O emissions by “agriculture and livestock” as reported by PRIMAP-hist.

In Supplementary Fig. 7 we show consumption-based estimates of CO2 emissions from fossil fuels since 1990. These are based on the data of emission transfer via international trade published by the CGP24.

To convert non-CO2 gases into CO2 equivalent emissions, we rely on the 100-year global warming potential (GWP100) factors, taken from IPCC’s AR667. We are aware of its limitations67,68, but we use it as it is the preferred metric of the IPCC and the UNFCC parties. Moreover, the emission scenarios we use to define genuine green growth are also expressed in GWP100.

Data on GDP and population are taken from the latest release of the Maddison Project Database (MPD), which provides data until 202227. MPD offers estimates for almost every country in the world; the time coverage and the periodicity vary in each case (see country coverage in Supplementary Fig. S8). It is not possible, therefore, to produce a global series via the addition of national data. However, the MPD offers aggregate estimates for eight world regions in 21 benchmark years between 1820 and 2022. To obtain an annual series for these eight regions, we have recalculated the regional series from the national-level data. For years when the MPD provided estimates for countries which encompassed more than 85% of a region’s aggregate GDP, we added up the national values to arrive at the regional total. Given the uneven coverage across regions, this recalculated annual series begins in different years in each region: for Western Europe, Western Offshoots, East Asia, and South and South-East Asia, the annual regional series covers the entire period, starting in 1820; for Latin America, it begins in 1830; for Sub-Saharan Africa in 1950; for Eastern Europe and Middle East and North Africa in 1980. The years preceding these annual regional series are calculated by interpolating MPD’s original regional benchmark estimates.

Territorial boundaries

Our national-level data refers to present-day borders, which is how all datasets report their estimates. The MPD in particular offers estimates on current countries as well as some former ones, including Czchecolsovakia, Yugoslavia, or the USSR. In cases where the current countries did not exist as such for parts of our period of analysis, we extend the national series backward using the rates of variation in population and GDP of the relevant former national states.

We also work with income and population data at the regional level. As mentioned above, the national estimates in the MPD are an unbalanced panel. Nevertheless, the MPD offers a balanced panel of estimates for eight world regions since 1820. Therefore, we follow the regional groups defined by Maddison and shown in Supplementary Table 3. In the case of emissions, the regional estimates are simply the result of adding up the national observations.

Throughout this text, we use the term “Western countries” to refer to the historical regions identified in the Maddison Project as “Western Europe“ and “Western Offshoots” (i.e., USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand), characterized by a comparatively early transition to modern economic growth and sustained economic development, higher levels of industrialization and capital accumulation, which allowed them to lead the global economy from the nineteenth century onwards.

Tapio model

To examine the coupling and decoupling patterns between GDP and emissions, we take inspiration from the Tapio model28. This model identifies up to eight possible scenarios depending on the growth rates of each variable. In this study, we adapt Tapio’s original model to identify the following six scenarios. (i) Dirty growth, which takes place when both GDP and GHGe grow, but GHGe substantially outpace GDP. More specifically, we consider that “dirty growth” occurs when the parameter b of Eq. (1) and Eq. (2) is greater than 1.2 (i.e., when emissions grow at a rate higher than 120% of GDP’s rate of growth). (ii) Coupled growth. In this case, both GDP and emissions grow at a similar pace, with b values between 0.8 and 1.2. (iii) Relative decoupling. GDP and GHGe both expand, but GDP outpaces GHGe substantially. More concretely, we consider relative decoupling takes place when b < 0.8, and thus GHGe grow at less than 80% of GDP’s rate of growth. (iv) Absolute decoupling. This scenario, usually associated with the idea of green growth, occurs when GDP grows and GHGe fall. (v) Recessive emission reduction. In this case, both emissions and GDP decrease. (vi) Dirty recessions. This scenario refers to a rise in GHGe in the context of falling GDP.

The b parameter is simply estimated as Eq. (1):

And thus as Eq. (2):

The variation of both GHGe and GDP is calculated as the difference between the year t + 1 relative to the year t.

Figure 3 and 4 show whether emission-reduction scenarios, i.e., absolute decoupling and recessive emission reduction, are due to a fall in land-based emissions. We identify as land-based driven reductions those in which land-based emissions contributed more to the overall decrease than all other emissions combined. As an example, if in a particular year, the GHGe of one country fall by 10 Gt CO2e due to a fall of 7 Gt in land-based emissions and 3 Gt in the rest of emissions, we consider this to be a case of land-based driven emission reduction.

Figure 4 makes an additional distinction within cases of absolute decoupling. In this figure we use the term “genuine green growth” for cases of absolute decoupling involving both robust economic growth and substantial emission reduction. By “robust economic growth” we understand a rate of cumulative annual output increase equal or greater than 2.4%, which is the projection of the OECD for the global economy up to 205069. We set the threshold for “substantial emission reduction” at 3.4%, which is the annual fall in emissions required for the planet to stay below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels by 2050 with a probability of 67%38. We also provide an estimate for the 1.5 °C scenario, which would require an annual cumulative reduction in emissions of 5.9%. In other words, the “genuine green growth” scenario allows us to identify past episodes in which an economy experienced output growth as predicted for the next decades, together with an emission reduction compatible with the current international climate agreements.

Genuine green growth benchmarks

Conventional definitions of green growth refer to economic growth accompanied by an absolute reduction in emissions. However, such emission reductions may be marginal, making them insufficient to meet climate agreements. Similarly, economic output may expand at a slow pace, failing to align with growth projections. Therefore, we identify a scenario that we refer to as genuine green growth, which entails significant economic growth alongside emission reductions compatible with climate agreements. Regarding growth, we consider it robust enough to meet the OECD’s projections for output expansion by 2050 (i.e., 2.6% annual GDP growth). For emissions, we use as benchmarks the C1 and C3 pathways assessed in the IPCC’s AR6, which respectively aim to limit warming to 1.5 °C (>50%) with no or limited overshoot and to 2 °C (>67%).

Given the uncertainties surrounding the large-scale implementation of negative emissions technologies, several studies include scenarios that limit or exclude their projected contributions. In this context, we develop an additional variation for the four scenarios described above—resulting in four new scenarios—in which the assumed impact of negative emissions technologies is constrained. Specifically, we exclude the contribution of carbon dioxide removals from emerging Biomass Carbon Capture and Storage technologies, which currently have negligible deployment. Furthermore, we assume that CO₂ emissions from certain industrial processes (e.g., cement production), where decarbonization is technically infeasible, will persist according to the trends projected in each evaluated scenario. The results of these scenarios are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

With this exercise, we just try to examine whether it is possible to find in the past instances of green growth compatible with the climate agreements and the expected trajectory of global economic growth. In other words, our historical mirror asks whether any country or region has in any period successfully reached a rate of change in emissions and economic output compatible with what is required at a global level today.

Cumulative emission reduction

In Fig. 4 of the main text, we show estimates of the cumulative emission reduction globally and regionally, distinguishing between different patterns. These are calculated by adding up the reductions at the national level. Consequently, when we include and disaggregate reductions in land-based driven drops, we estimate which part of net emission reduction in a region or the world is due to land-based emissions in order to make these results compatible with the national-level figures. An example: total emissions fall in one country during one year by 10 Gt CO2e, as a result of a fall of 15 Gt of CO2e from land-based emissions and an increase of 5 Gt of CO2e in other emissions. In this case, 10 Gt CO2e represents the net fall, which is what we count as cumulative emission reduction. However, if we instead counted the gross reductions (in this example, 15 Gt CO2e), our results would not substantially change, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 9.

Decomposition analysis

In the “Patterns of GHGe reduction” section, we consider whether the fall in emissions took place in contexts of economic growth (absolute decoupling) or contraction (recessive emission reduction). In the case of recessive emission reduction, the fall in emissions could be explained by the economic contraction itself, or by improvements in efficiency allowing for a decreasing carbon intensity of economic activity. We calculate how much of emission reduction in these contexts was explained by GDP contraction, and how much by improvements in the carbon intensity. To do so, we rely on decomposition analysis using an additive logarithmic median Divisia index. At a national level, we calculate the variation in annual emissions (C), and decompose the part of the variation responding to population change (P), GDP per capita (A), and carbon intensity (T), as Eq. (3):

The general contribution of each of the components is then calculated as the summation of the values corresponding to each country i in the year t, as Eq. (4):

Uncertainty

We estimated the uncertainty in the GHGe series by combining the uncertainty of emission values of each gas and activity with the uncertainty in the GWP of that gas (Fig. S4). The uncertainty ranges (coefficient of variation, CV) of the emission values of each kind of gas and activity were retrieved from Jones et al.25 and AR6 IPCC38, and are as follows: CO2-FFI ± 8%; CO2-LULUCF ± 70%; CH4 ± 30%; N2O ± 60%; F-gases ± 30%; GHG ± 11%38. Regarding the uncertainty in the GWP of non-CO2 gases, we obtained the values from the IPCC A6 report67. The CV in the GWP100 of each gas is as follows: fossil CH4 37%; biogenic CH4 41%; N2O 48%; F-gases 30%.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed in this study and the computer code are available on Zenodo at the following link: https://zenodo.org/records/13944279. The estimations rely on several open-access databases: GDP and population data from the Maddison Project27; CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and cement from the Global Carbon Project24; land-based CO₂ emissions from Jones et al.25; and CH₄ and N₂O emissions from PRIMAP-Hist26,66. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code used in this study is available on Zenodo at the following link: https://zenodo.org/records/13944279.

Change history

30 May 2025

In this article, the acknowledgements section was incorrectly given as, ‘The authors would like to thank Alexander Urrego and Iñaki Iriarte for their help and comments, as well as the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback, which helped improve the work. This project has been partially financed by the State Research Agency (SRA) and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) (grant numbers AEI/PID2021-124394NB-I00, with E.T. as a member of the research team, and AEI/PID2021-123220NB-I00, awarded to J.I.A.), Areces Foundation (grant number CISP19A6420, awarded to J.I.A.) and the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation program (ERC StG Project 101115126 “WHEP,” awarded to E.A.). E.A. is supported by a Ramón y Cajal Grant (RYC2022-037863-I), funded by MICIU/AEI /10.13039/501100011033 and by the European Social Fund Plus (ESF+).’ and should have been ‘The authors would like to thank Alexander Urrego and Iñaki Iriarte for their help and comments, as well as the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback, which helped improve the work. This research has received funding from the following projects and institutions: project PID2021-123220NB-I00, funded by MCIN/AEI /10.13039/501100011033 and by FEDER, EU, and the Areces Foundation (grant number CISP19A6420), both awarded to J.I.A.; project PID2021-124394NB-I00, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by FEDER, EU, with E.T. as a member of the research team; and the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation program (ERC StG Project 101115126 “WHEP,” awarded to E.A.). E.A. is also supported by a Ramón y Cajal Grant (RYC2022-037863-I), funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the European Social Fund Plus (ESF+)’. The original article has been corrected.

References

UNEP. Towards a Green Economy: Pathways to Sustainable Development and Poverty Eradication (United Nations Environment Programme, 2011).

OECD. Towards Green Growth (Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development, 2011).

OECD. Beyond Growth: Towards a New Economic Approach (Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development, 2020).

World Bank. Inclusive Green Growth: The Pathway to Sustainable Development (The World Bank, 2011).

Haberl, H. et al. A systematic review of the evidence on decoupling of GDP, resource use and GHG emissions, part II: synthesizing the insights. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 065003 (2020).

Stoknes, P. E. & Rockström, J. Redefining green growth within planetary boundaries. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 44, 41–49 (2018).

King, L. C., Savin, I. & Drews, S. Shades of green growth scepticism among climate policy researchers. Nat. Sustain. 6, 1316–1320 (2023).

Jackson, T. & Victor, P. A. Unraveling the claims for (and against) green growth. Science 366, 950–951 (2019).

Panayotou, T. Empirical Tests and Policy Analysis of Environmental Degradation at Different Stages of Economic Development (International Labour Office, 1993).

Grossman, G. M. & Krueger, A. B. Environmental impacts of a North American free trade agreement. NBER Working Paper No. 3914. https://doi.org/10.3386/w3914 1–57 (National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, 1991).

Stern, N. & Stiglitz, J. E. Climate change and growth. Ind. Corp. Change 32, 277–303 (2023).

van Vuuren, D. P. et al. Energy, land-use and greenhouse gas emissions trajectories under a green growth paradigm. Glob. Environ. Change Hum. Policy Dimens. 42, 237–250 (2017).

Dasgupta, S., Laplante, B., Wang, H. & Wheeler, D. Confronting the environmental Kuznets curve. J. Econ. Perspect. 16, 147–168 (2002).

Dinda, S. Environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis: a survey. Ecol. Econ. 49, 431–455 (2004).

Stern, D. I. The rise and fall of the environmental Kuznets curve. World Dev. 32, 1419–1439 (2004).

Parrique, T. et al. Decoupling debunked: Evidence and arguments against green growth as a sole strategy for sustainability. 1–79 (European Environmental Bureau (EEB), Brussels, 2019).

Wiedmann, T., Lenzen, M., Keyßer, L. T. & Steinberger, J. K. Scientists’ warning on affluence. Nat. Commun. 11, 3107 (2020).

Hickel, J. & Kallis, G. Is green growth possible? N. Political Econ. 25, 469–486 (2020).

Hubacek, K., Chen, X., Feng, K., Wiedmann, T. & Shan, Y. Evidence of decoupling consumption-based CO2 emissions from economic growth. Adv. Appl. Energy 4, 100074 (2021).

Tilsted, J. P., Bjørn, A., Majeau-Bettez, G. & Lund, J. F. Accounting matters: revisiting claims of decoupling and genuine green growth in Nordic countries. Ecol. Econ. 187, 107101 (2021).

Le Quere, C. et al. Drivers of declining CO2 emissions in 18 developed economies. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 213–217 (2019).

Shuai, C., Chen, X., Wu, Y., Zhang, Y. & Tan, Y. A three-step strategy for decoupling economic growth from carbon emission: empirical evidences from 133 countries. Sci. Total Environ. 646, 524–543 (2019).

Ritchie, H. Not the End of the World: How We Can Be the First Generation to Build a Sustainable Planet (Random House, 2024).

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Global Carbon Budget 2021. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 1917–2005 (2022).

Jones, M. W. et al. National contributions to climate change due to historical emissions of carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide since 1850. Sci. Data 10, 155 (2023).

Gütschow, J. & Pflüger, M. The PRIMAP-hist national historical emissions time series (1750-2022) v2.5.1. (2024).

Bolt, J. & van Zanden, J. L. Maddison style estimates of the evolution of the world economy: a new 2023 update. J. Econ. Surv. 12, 1–41 (2024).

Tapio, P. Towards a theory of decoupling: degrees of decoupling in the EU and the case of road traffic in Finland between 1970 and 2001. Transp. Policy 12, 137–151 (2005).

Wu, Y., Zhu, Q. & Zhu, B. Comparisons of decoupling trends of global economic growth and energy consumption between developed and developing countries. Energy Policy 116, 30–38 (2018).

Vonyó, T. Post-war reconstruction and the Golden Age of economic growth. Eur. Rev. Econ. Hist. 12, 221–241 (2008).

Steffen, W., Broadgate, W., Deutsch, L., Gaffney, O. & Ludwig, C. The trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration. Anthr. Rev. 2, 81–98 (2015).

Sanchez, L. F. & Stern, D. I. Drivers of industrial and non-industrial greenhouse gas emissions. Ecol. Econ. 124, 17–24 (2016).

Page, S. E. et al. The amount of carbon released from peat and forest fires in Indonesia during 1997. Nature 420, 61–65 (2002).

Gingrich, S. et al. Hidden emissions of forest transitions: a socio-ecological reading of forest change. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 38, 14–21 (2019).

Gingrich, S., Lauk, C., Krausmann, F., Erb, K.-H. & Le Noë, J. Changes in energy and livestock systems largely explain the forest transition in Austria (1830–1910). Land Use Policy 109, 105624 (2021).

Peters, G. P. From production-based to consumption-based national emission inventories. Ecol. Econ. 65, 13–23 (2008).

Meyfroidt, P. & Lambin, E. F. Global forest transition: prospects for an end to deforestation. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 36, 343–371 (2011).

IPCC. Mitigation of Climate Change: Working Group III Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 2022).

Jackson, T., Hickel, J. & Kallis, G. Confronting the dilemma of growth. A response to Warlenius (2023). Ecol. Econ. 220, 108089 (2024).

Grubler, A. et al. A low energy demand scenario for meeting the 1.5 C target and sustainable development goals without negative emission technologies. Nat. Energy 3, 515–527 (2018).

Fuss, S. et al. Negative emissions—Part 2: costs, potentials and side effects. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 063002 (2018).

Anderson, K. & Peters, G. The trouble with negative emissions. Science 354, 182–183 (2016).

Armstrong McKay, D. I. et al. Exceeding 1.5 °C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points. Science 377, eabn7950 (2022).

D’Alessandro, S., Cieplinski, A., Distefano, T. & Dittmer, K. Feasible alternatives to green growth. Nat. Sustain. 3, 329–335 (2020).

Vogel, J. & Hickel, J. Is green growth happening? An empirical analysis of achieved versus Paris-compliant CO2–GDP decoupling in high-income countries. Lancet Planet. Health 7, e759–e769 (2023).

Sorrell, S., Dimitropoulos, J. & Sommerville, M. Empirical estimates of the direct rebound effect: a review. Energy Policy 37, 1356–1371 (2009).

Berkhout, P. H., Muskens, J. C. & Velthuijsen, J. W. Defining the rebound effect. Energy Policy 28, 425–432 (2000).

Smil, V. Making the Modern World: Materials and Dematerialization 242 (Wiley, 2013).

Smil, V. Energy and Civilization: A History (MIT Press, 2018).

Kander, A., Malanima, P. & Warde, P. Power to the People: Energy in Europe over the Last Five Centuries (Princeton University Press, 2014).

Henriques, S. T. & Borowiecki, K. J. The drivers of long-run CO2 emissions in Europe, North America and Japan since 1800. Energy Policy 101, 537–549 (2017).

Malanima, P. Energy, productivity and structural growth. The last two centuries. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 58, 54–65 (2021).

Alcott, B. Jevons’ paradox. Ecol. Econ. 54, 9–21 (2005).

Rockström, J. et al. Planetary boundaries: exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecol. Soc. 14, 1–32 (2009).

Rockström, J. et al. Safe and just Earth system boundaries. Nature 619, 102–111 (2023).

Chancel, L. Global carbon inequality over 1990–2019. Nat. Sustain. 5, 931–938 (2022).

Hickel, J. Quantifying national responsibility for climate breakdown: an equality-based attribution approach for carbon dioxide emissions in excess of the planetary boundary. Lancet Planet. Health 4, e399–e404 (2020).

den Elzen, M. et al. Analysing countries’ contribution to climate change: scientific and policy-related choices. Environ. Sci. Policy 8, 614–636 (2005).

Andrew, R. M. & Peters, G. P. The Global Carbon Project’s fossil CO2 emissions dataset. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.5569235 (2021).

Gilfillan, D. & Marland, G. CDIAC-FF: global and national CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion and cement manufacture: 1751–2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 1667–1680 (2021).

Myhre, G., Alterskjær, K. & Lowe, D. A fast method for updating global fossil fuel carbon dioxide emissions. Environ. Res. Lett. 4, 034012 (2009).

Hansis, E., Davis, S. J. & Pongratz, J. Relevance of methodological choices for accounting of land use change carbon fluxes. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 29, 1230–1246 (2015).

Houghton, R. A. & Nassikas, A. A. Global and regional fluxes of carbon from land use and land cover change 1850–2015. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 31, 456–472 (2017).

Gasser, T. et al. Historical CO2 emissions from land use and land cover change and their uncertainty. Biogeosciences 17, 4075–4101 (2020).

Hurtt, G. C. et al. Harmonization of global land-use change and management for the period 850-2100 (LUH2) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. Discuss. 2020, 1–65 (2020).

Gütschow, J. et al. The PRIMAP-hist national historical emissions time series. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 8, 571–603 (2016).

IPCC. The Physical Science Basis: Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Lynch, J., Cain, M., Pierrehumbert, R. & Allen, M. Demonstrating GWP*: a means of reporting warming-equivalent emissions that captures the contrasting impacts of short-and long-lived climate pollutants. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 044023 (2020).

Real GDP long-term forecast (OECD). https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/real-gdp-long-term-forecast.html (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Alexander Urrego and Iñaki Iriarte for their help and comments, as well as the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback, which helped improve the work. This research has received funding from the following projects and institutions: project PID2021-123220NB-I00, funded by MCIN/AEI /10.13039/501100011033 and by FEDER, EU, and the Areces Foundation (grant number CISP19A6420), both awarded to J.I.A.; project PID2021-124394NB-I00, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by FEDER, EU, with E.T. as a member of the research team; and the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation program (ERC StG Project 101115126 “WHEP,” awarded to E.A.). E.A. is also supported by a Ramón y Cajal Grant (RYC2022-037863-I), funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the European Social Fund Plus (ESF+).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.I.A.: conceptualization, data curation, methodology, project administration, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. E.T.: conceptualization, formal analysis, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. E.A.: conceptualization, formal analysis, and writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Infante-Amate, J., Travieso, E. & Aguilera, E. Green growth in the mirror of history. Nat Commun 16, 3766 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58777-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58777-4