Abstract

Whether language has its evolutionary origins in vocal or gestural communication has long been a matter of debate. In humans, the arcuate fasciculus, a major fronto-temporal white matter tract, is left-lateralized, is larger than in nonhuman apes, and is linked to language. However, the extent to which the arcuate fasciculus of nonhuman apes is linked to vocal and/or manual communication is currently unknown. Here, using probabilistic tractography in 67 chimpanzees (45 female, 22 male), we report that the chimpanzee arcuate fasciculus is not left-lateralized at the population level, in marked contrast with humans. However, individual variation in the anatomy and leftward asymmetry of the chimpanzee arcuate fasciculus is associated with individual variation in the use of both communicative gestures and communicative sounds under volitional orofacial motor control. This indicates that the arcuate fasciculus likely supported both vocal and gestural communication in the chimpanzee/human last common ancestor, 6–7 million years ago.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The arcuate fasciculus (AF) is a large white matter tract that connects ventrolateral frontal cortex with lateral temporal cortex, passing through the white matter below lateral parietal cortex1. In humans, the primary endpoints of the AF, Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas, are implicated in language functions, and this network shows robust population-level left-lateralization2,3,4,5,6,7. However, whether this asymmetry exists in nonhuman primates is a matter of debate. There have been conflicting results across studies, several of which have used relatively small sample sizes and/or did not include both males and females8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Here, using a mixed-sex sample of 67 chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), we test for population-level asymmetries in the AF.

Additionally, whether individual variation in the nonhuman primate arcuate fasciculus is associated with communication is entirely unknown. Accordingly, we also assessed a unique category of communicative behaviors described in chimpanzees and other great apes. Attention-getting sounds (AGs) include raspberries, kisses, and extended food grunts15,16,17. Raspberries are produced by expelling air through pursed lips and sound like a “Bronx cheer,” while kisses involve drawing air through pursed lips and sound exactly as the name implies. Extended food grunts are a voiced, low frequency, atonal sound that is a modification to naturally-occurring food grunts. In wild chimpanzees, AGs are most commonly produced during grooming, particularly between male dyads, and are thought to signal positive intentions18. In captivity, AGs are similarly produced during grooming19 but are also used to capture the attention of an otherwise inattentive human audience20,21,22,23,24,25.

AGs are of interest for several reasons. First, AGs are under voluntary motor control26,27,28,29. Second, like human languages, individual variation in the use of AGs appears to be socially learned and run in families17. Third, AGs are primarily used in social communication contexts, which makes them important as potential indicators of ancestral pre-adaptations for human language. Therefore, we examined whether individual variation in AG behavior was associated with AF volume, asymmetry, and fractional anisotropy (FA), a scalar measure of white matter that can reflect myelination and/or tract coherence, although it is not a comprehensive index of all aspects of white matter microstructure30. We also quantified the volume and asymmetry of AF terminations into ventral premotor cortex and the homolog of Broca’s area, where gray matter morphology has previously been associated with the production of attention-getting sounds31,32,33.

Importantly, great apes also possess a rich gestural communication repertoire34. Captive chimpanzees show population-level right-hand preference for gesture production35. Whether spoken human language may have evolved from gestural origins has been a matter of heated debate35,36,37. We measured chimpanzees’ frequency and hand preference when using manual gestures to draw a human’s attention toward out-of-reach food (initiating a behavioral request, IBR)38,39,40. We considered the possibility that manual gestures and AGs might involve white matter tracts other than the AF, particularly those that link frontal, parietal, and temporal regions associated communication and orofacial/manual action. Therefore, we also examined the superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF), ventral pathway (VP), and corticospinal tract (CST). It is important to keep in mind that modern chimpanzees are not the ancestors of modern humans. However, brain-behavior relationships that are present in both chimpanzees and humans likely reflect functionality present in the chimpanzee-human last common ancestor, and can therefore shed light on the emergence of pre-adaptations for language evolution. We reasoned that if significant relationships existed between vocal and/or gestural communication and the anatomy of any of these tracts, then that would suggest that the tract played a functional role in that aspect of communication in the chimpanzee/human last common ancestor.

Results

Tractography

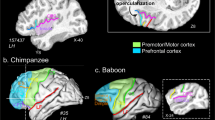

Within the total sample 67 subjects, complete and reliable parcellation of the AF, SLF, CST, and VP was achieved in 47, 58, 67, and 56 chimpanzees, respectively. Figure 1 shows group composite images for each tract, illustrating above-threshold connectivity in over 50% of subjects for each tract. Expanded views of tractography are available in Supplementary Figs. 1–4.

Age effects

Because the age range of the subjects were considerable within the chimpanzee sample, we initially tested for their association with mean FA and volume as well as the AQ values. These results are shown in Table 1. Increasing age was associated with lower bihemispheric mean FA values for the AF and SLF but not the CST and VP tracts. No significant associations were found between age and the mean volume or the AQ values for the volumes and FA values for any of the 4 tracts.

Lateralization

We tested for population-level asymmetries in the volume and FA for each tract as well as the gray matter terminations of the arcuate fasciculus into PMv and Broca’s area using one sample t-tests and these results are shown in Table 2. Also shown in Table 2 are the number of chimpanzees with a positive (rightward) or negative (leftward) AQ scores for each measure. Significant leftward asymmetries were found for the CST FA and volume. By contrast, we found a significant rightward asymmetry for SLF volume and a borderline leftward asymmetry for SLF FA. For the gray matter terminations of the AF, no significant population-level asymmetry was found, but terminations in PMv did approach conventional levels of statistical significance toward rightward asymmetry (p < 0.10). When considering the sign of the difference scores, we also found a significant association between lateralization and sex for the terminations of the arcuate fasciculus into PMv using a chi-square test of independence, X2(1, N = 47) = 3.958, p = 0.047, Φ = 0.290). A higher proportion of males showed a leftward asymmetry of AF PMv terminations compared to females. None of the remaining chi-square tests were significant.

Correlates with AG sound production

In the initial analysis, we found no significant main effects or interactions of sex or AG group on bihemispheric mean AF volume or FA values. For the AF AQ scores, the MANOVA revealed a significant two-way interaction between sex and AG group, F(2, 42) = 3.938, p = 0.027, ηp2 = 0.158. Subsequent univariate F-test revealed a significant two-way interaction between sex and AG group for the AF volume, F(1, 43) = 6.509, p = 0.026, ηp2 = 0.131, but not FA value, F(1, 43) = 0.030, p = 0.862, ηp2 = 0.001. The mean AF AQ scores +/− SEM for male and female AG− and AG+ chimpanzees is shown in Fig. 2a. Post-hoc analysis indicated that AG+ males had more leftward asymmetries in the AF volume compared to AG− males and AG+ females. For the SLF, CST, and VP, the MANOVAs revealed no significant main effects or interactions of sex or AG group for either the mean volume, mean FA values, the AQ volume or the FA AQ values. Regarding the AF gray matter terminations, the mixed-model analysis of the mean AF gray matter terminations failed to reveal any significant main effects or interactions; however, for the AQ scores, a significant two-way interaction was found between sex and AG group F(1, 43) = 6.816, p = 0.012, ηp2 = 0.137. The mean gray matter termination AQ scores +/− SEM for male and female AG− and AG+ chimpanzees is shown in Fig. 2b. As was the case for the AF volume, post-hoc analysis indicated that AG+ males had more leftward asymmetries in the combined Broca’s area and PMv gray matter terminations compared to AG− males and AG+ females.

A Box and whisker plot of AQ volume for AG− (red) and AG+ (blue) male and female chimpanzees. Significant two-way interaction between sex and AG group for AF volume: F(1, 43) = 6.509, p = 0.026, ηp2 = 0.131. B Box -and-whisker plot of gray matter AQ termination values for AG− (red) and AG+ (blue) male and female chimpanzees. Significant two-way interaction between sex and AG group: F(1, 43) = 6.816, p = 0.012, ηp2 = 0.137. For (A and B), each circle within the bar graph represents an individual subject data point and the highest and lowest horizontal lines (boundaries) of the whiskers represent the maximum and minimum values. The upper and lower lines within the box represent the 25th and 75th percentiles while the central horizontal line indicates the median. Note that negative AQ values indicate leftward asymmetry. AG− indicates individuals that do not produce attention-getting sounds; AG+ indicates individuals that do. Total N = 47 chimpanzees for these analyses. GM gray matter.

Recall that chimpanzees were classified as AG− and AG+ based on their percentage in producing AG sounds across the 6 trial test sessions. As a follow up analysis, we also performed a correlation coefficient between the percentage of trials on which chimpanzees made an AG sound and the AQ scores for the AF volume (Fig. 3). Correlation analyses were run only to confirm significant MANCOVA results and were not carried out exhaustively over a large number of variables. For females, there was a non-significant positive association between the percentage AG sound use and the volume AQ scores, indicating that AG sound use was weakly associated with more rightward asymmetric AF tract volumes (r(28) = 0.167, p = 0.312). By contrast, in males, there was a significant negative association with higher percentages in the use of AG sounds were produced associated with greater leftward asymmetry of AF volume (r(15) = −0.716, p = 0.001). These findings validate the MANOVA results and suggest that the leftward asymmetry in AF volume among males is manifest whether characterizing AG sound production on a binary or continuous scale of measurement.

For males, (blue) increased production of AG sounds were significantly associated with greater leftward asymmetries in the volume of the arcuate fasciculus r(15) = −0.716, p = 0.001). By contrast, among females, increased production of AG sounds was associated with greater rightward asymmetries in the arcuate fasciculus, though the correlation was non-significant r(28) = 0.167, p = 0.312). The correlation coefficients differed significantly between males and females (z = −3.711, p < 0.001).

Further, we also assessed the relationship between AG sound production and asymmetry of gray matter terminations within Broca’s area and ventral premotor cortex (Fig. 4a, b). For terminations in Broca’s area, females showed a non-significant positive (rightward) association with the percentage of trials on which an AG sound was produced (r (28) = +0.184, p = 0.330) whereas males showed a significant negative (leftward) association (r(15) = −0.418, p = 0.081). Notably, effect sizes for males in each of these correlations are in the moderate to strong range. For terminations in PMv, males showed a moderate, significant negative (leftward) association with the percentage of trials on which AG sounds were produced (r(15) = −0.533, p = 0.027), whereas females showed a weak, significant positive (rightward) association (r(28) = 0.356, p = 0.058).

A Males (blue) show a moderate, significant association between AG sound use and leftward asymmetry of terminations in Broca’s (r(15) = −0.418, p = 0.081) whereas females showed a non-significant positive (rightward) association with the percentage of trials on which an AG sound was produced (r(28) = +0.184, p = 0.330). The correlation coefficients differed significantly between males and females (z = −1.917, p = 0.028). B For terminations in PMv, males showed a moderate, significant association with the percentage of trials on which AG sounds were produced associated with increasing leftward asymmetry (r(15) = −0.533, p = 0.027), whereas females showed a weak, significant positive (rightward) association (r(28) = 0.356, p = 0.058). The correlation coefficients differed significantly between males and females (z = −2.935, p = 0.002). GM gray matter.

Correlates with manual gesture communication

For the bihemispheric mean AF volume and FA values, the MANCOVA revealed a significant main effect for IBR performance, F(2, 41) = 3.610, p = 0.036, ηp2 = 0.150. Subsequent univariate F-test revealed a significant main effect of IBR performance on mean AF FA value F(1, 42) = 4.239, p = 0.046, ηp2 = 0.092 with AA performing chimpanzees having higher FA values than BA apes (Fig. 5a). No significant main effects or interactions were found for the AF volume or FA AQ scores. Regarding SLF, no significant main effects or interactions were found for the mean SLF volume or FA values; by contrast, the MANCOVA revealed a significant main effect for IBR performance for the AQ scores, F(2, 52) = 8.395, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.244. The univariate F-tests revealed significant effects of IBR performance on AQ values for both SLF FA F(1, 53) = 9.611, p = 0.003, ηp2 = 0.153 (see Fig. 5b) and volume F(2, 52) = 8.824, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.143 (see Fig. 5c). For both measures, AA chimpanzees had greater leftward AQ values than BA apes. For CST, no significant main effects or interactions were found for mean volume or FA values. For the CST AQ values, a borderline significant main effect for IBR performance was found F(2, 62) = 2.879, p = 0.064, ηp2 = 0.085 with the univariate F-tests revealing a significant effect for the AQ FA scores F(1, 63) = 5.137, p = 0.027, ηp2 = 0.076. As with the SLF, AA chimpanzees had greater leftward asymmetries than AB apes. Finally, the MANCOVA failed to reveal any significant main effect or interactions for the VP mean volume and FA values as well as the corresponding AQ scores.

A Box-and-whisker plot of individual FA values for each tract in BA (red) and AA (blue) chimpanzees. Chimpanzees that performed above average (AA, blue) had significantly higher mean bihemispheric FA within the arcuate fasciculus (AF) than chimpanzees that performed below average (BA, red). Significant main effect of IBR performance on mean AF FA value F(1, 42) = 4.239, p = 0.046, ηp2 = 0.092. B Box-and-whisker plot of individual AQ FA values for each tract in BA (red) and AA (blue) chimpanzees. Chimpanzees that performed above average had significantly greater leftward asymmetries for FA values than those that performed below average. Significant effect of IBR performance on asymmetry quotient for superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF) FA: F(1, 53) = 9.611, p = 0.003, ηp2 = 0.153. C Box-and-whisker plot of individual AQ volume values for each tract in BA (red) and AA (blue) chimpanzees. Chimpanzees that performed above average had significantly more leftwardly-asymmetric SLF volume values than those that performed below average. Significant effects of IBR performance on asymmetry quotient for SLF volume: F(2, 52) = 8.824, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.143. For all Figures, each circle within the bar graph represents an individual subject data point and the highest and lowest horizontal lines (boundaries) of the whiskers represent the maximum and minimum values. The upper and lower lines within the box represent the 25th and 75th percentiles while the central horizontal line indicates the median. Negative AQ values indicate leftward asymmetry. AG− indicates individuals that do not produce attention-getting sounds; AG+ indicates individuals that do. For all analyses, * indicates p < 0.05. CST corticospinal tract, VP ventral pathway.

As was done for the analysis of AG sound use, while controlling for age, we also assessed correlations between the percentage of trials in which chimpanzees made an IBR with the mean AF FA values, SLF volume and FA AQ scores and the CST AQ values (Fig. 6), as a means determining whether the use of the cut-points to classify the apes as AA or BA may have biased the results. A significant positive correlation was found between IBR performance and (1) mean AF FA values (r(43) = 0.364, p = 0.007) (2) leftward asymmetry in the volume of the SLF (r(54) = −0.305, p = 0.011) and (3) leftward asymmetry in the mean FA of the SLF (r(54) = −0.432, p < 0.001). We failed to find a significant association between IBR performance and the AQ values for the CST FA values (r(63) = −0.160, p = 0.102).

A Increasing IBR performance was associated with higher mean fractional anisotropy (FA) values in the arcuate fasciculus (r(43) = 0.364, p = 0.014). B Better IBR performance correlates with increased leftward asymmetry in the volume of the superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF) (r(54) = 0.305, p = 0.02. C Increasing IBR performance correlates with greater leftward asymmetry in FA values for the SLF(r(54) = −0.432, p = 0.001). D No significant relationship between gestural initiation of a behavioral request (IBR) and asymmetry of fractional anisotropy values within the corticospinal tract (CST) (r(63) = −0.160, p = 0.102).

MANCOVA analyses did not find any significant relationship between individual variation in hand preference for gesture production and the asymmetry in the FA or volume of any tract. Further, no significant relationships were found between gesture hand preference and asymmetry of gray matter terminations in Broca’s area or PMv.

Discussion

In this study, we used probabilistic tractography in a sample of 67 chimpanzees to assess relationships between the anatomy and lateralization of the arcuate fasciculus (AF) and communication behavior. This produced 3 main findings.

First, we did not find evidence for population-level asymmetry in the volume or fractional anisotropy (FA) of the chimpanzee AF. Further, no population-level asymmetries were found in the gray matter terminations of the AF into PMv or Broca’s area. This is a marked difference from the human AF, which is consistently found to be lateralized to the left hemisphere in both volume and FA2,3,5,6,7,41. Thus, it appears that a significant and potentially important difference between humans and chimpanzees is in the lateralization of the AF and its frontal targets13,42,43,44,45,46.

We also failed to find population-level asymmetries in the volume or FA in the VP tracts. Chimpanzees did show a rightward asymmetry in SLF FA and volume and a leftward asymmetry in CST FA and volume (see Table 2), a finding consistent with previous work in chimpanzees47 and humans, particularly right-handed individuals48,49. The leftward CST asymmetries within this cohort of chimpanzees may be explained by the fact that a statistical majority are right-handed when assessed across multiple measures of hand preference50.

Second, we found that individual variation in chimpanzee AF anatomy is linked to volitional orofacial motor control within the context of communicative sound production. This relationship varied in a sex-dependent manner. Specifically, males who produced attention-getting sounds (AG+) had greater leftward asymmetries AF volume and gray matter terminations in Broca’s area and PMv compared to AG− individuals (see Fig. 2). By contrast, AG+ females had greater rightward AF asymmetries as well as gray matter terminations in Broca’s area and PMv compared to AG− females. The sex-dependent pattern is consistent with previous studies in this cohort of chimpanzees. For instance, Hopkins, Coulon33 found that the depth of the middle and inferior portions of the central sulcus differed between AG+ and AG− chimpanzees in a sex dependent manner. Similarly, Hopkins32 found that AG+ and AQ− chimpanzees differed in lateralization in the surface area and depth of the inferior frontal and precentral inferior sulcus in a sex dependent manner. Note that the inferior frontal and precentral inferior sulci are the superior and posterior border of the inferior frontal gyrus, which contains the chimpanzee homolog to Broca’s area.

Third, we found that individual variation in the anatomy of the AF and SLF is associated with the production of manual communicative gestures. Specifically, within the AF, we observed higher FA values in chimpanzees that more consistently engaged in the initiation of a behavioral request (IBR) by manually gesturing toward unreachable food in the presence of a human experimenter (see Fig. 5a). Moreover, within the SLF, chimpanzees that more consistently engaged in IBR had greater leftward FA and volume AQ values than those that did not (see Fig. 5b, c). In humans, frontal and parietal regions that are connected by the AF and SLF are consistent with regions hypothesized to play a role in joint attention51.

We did not find any significant association between asymmetry of the AF and handedness for gesture production. This is consistent with a previous study in humans which found that AF asymmetry was not associated with handedness52. Previous studies in both captive and wild chimpanzees have reported significant rightward asymmetries in hand use for gestural communication53,54. However, we found no significant associations between hand use for manual gestures and the FA or volumetric AQ values for any of the tracts. This suggests that individual variation in the anatomical characteristics of these tracts is associated with chimpanzees’ propensity to produce IBR gestures, rather than handedness for the gesture itself.

Taken together, these findings suggest a potential neuro-ethological scenario for the evolution of communication circuits in the great ape lineage. In the wild, chimpanzees and other great apes produce a complex and diverse set of voluntary manual gestural/tactile signals34, as well as “sound gestures” in the auditory domain such as AGs55,56,57,58. Gestures in the manual/tactile domain are well developed in chimpanzees and our results suggest that these behaviors at least partially involve the SLF, which is visibly more robust in chimpanzees than the AF (see Fig. 1). Meanwhile, gestures in the auditory domain are more variable and appear to be more narrowly associated with the less-developed AF, with leftward AF asymmetry being linked to increased auditory orofacial communication specifically in males. Notably, previous studies in wild and captive chimpanzees have reported that the proportion of individuals that produce AG sounds is greater in males than females18,33. We further note that the sex-dependent associations between orofacial motor control and the asymmetry of white matter tract volumes were specific to the AF tract and non-significant for the SLF, VP, and CST. This suggests that the AF plays in a potentially unique role in the cognitive and/or motor aspects of this simple form of auditory communication. Speculatively, then, the variability in the use of voluntary sounds as gestures in chimps may create some individual advantages for males such as enhanced social rank or increased mating opportunities. This hypothesis could be tested with behavioral observations in the wild. It predicts that males who make more voluntary auditory gestures will have increased fitness, i.e., more offspring.

If fitness benefits do indeed occur from increased AF-dependent communication, it raises the possibility that this trait could have been selected for in the lineage leading to humans, gradually producing more sophisticated sound-based communication systems (language) that rely heavily on the connections provided by the AF. Speculatively, given the social and communicative role of AG sound use in wild and captive chimpanzees17,18, this finding suggests that the AF tract may have had a role in volitional communication in the auditory domain in the chimpanzee-human last common ancestor, but that the human lineage experienced much greater expansion, elaboration, and leftward-lateralization of this tract after the split.

Several limitations of the present study should be considered. It examined four specific tracts rather than considering a more comprehensive set of fibers. Of course, there are additional tracts that may be associated with the behavioral measures quantified in this study. Thus, future studies should consider additional tracts for measurement, particularly those that connect Broca’s area and the PMv with other brain regions. Additionally, the AF in humans typically includes robust components for both the frontal-parietal limb and the parietal-temporal limb. We found that the extension of the AF past the posterior superior temporal gyrus was highly variable across chimpanzees, and we therefore measured FA only within the core portion of the tract was consistently present across individuals, which reaches minimally into the temporal lobe (see Fig. 1). Moreover, the scalar index of white matter assessed here, FA, is not a comprehensive index of all aspects of white matter microstructure30. Histological research would be ideally suited to examine the underlying cellular-level cause of variation in FA observed here, which could potentially include variables like axon thickness, myelin density, and/or presence/absence of crossing fibers. Additionally, because of the correlative nature of the study, we cannot make any causal inferences regarding the associations we found between the behavioral and anatomical measures studied here. We cannot rule out that our behavioral assessments of communication are not at least partially indexing emotional processes like attention and motivation; however, the presence of significant associations between these behavioral indices and neuroanatomical features known to support communication argues that the behavioral tests do reflect communicative processing in the brain.

Lastly, with regard to neuroanatomical traits that differ between chimpanzees and humans, we cannot disambiguate between the potential effects of evolved and acquired change. Humans are immersed in a language-rich environment from birth, while chimpanzees are not, raising the possibility that some aspects of human language circuitry, such as the asymmetry, FA, or volume of the AF, may be at least partially the result of experience-dependent plasticity.

In conclusion, there are few if any studies to date examining behavioral or cognitive correlates of individual variation in white matter connectivity of different tracts within the brains of nonhuman primate species. Here, we found that although the chimpanzee arcuate fasciculus is not left-lateralized at the population level, greater leftward asymmetry was observed in male chimpanzees that produce attention-getting sounds, a unique category of volitional orofacial auditory communicative behaviors. We further found that the use of manual gestural communication to initiate joint attention with a human experimenter was associated with increased FA values in the arcuate fasciculus as well as higher mean FA and greater rightward asymmetry within the SLF. Together, these collective data suggest that the white matter tracts that connect Broca’s area with the parietal and temporal lobes played a role in communication behavior prior to the split between the last common ancestor of chimpanzees and humans, but that evolved changes after this split, particularly in the leftward asymmetry of the arcuate fasciculus, may be part of the uniquely human neural basis for language.

Methods

Subjects

Research procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Emory University. Data was collected in 67 chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) including 45 females and 22 males housed at the Emory National Primate Research Center (formerly Yerkes). At the time they were scanned, they ranged in age between 9 and 54 years of age (Mean = 24.16 years, SD = 11.21). No subjects were excluded from analysis. Replication was not applicable to this study as all available scans were used for the present analysis.

Image collection

Scan acquisition details are described on the National Chimpanzee Brain Resource website: https://www.chimpanzeebrain.org/protocols. Briefly, chimpanzees were sedated with ketamine (2–6 mg/kg, i.m.) and anesthetized with propofol (10 mg/kg/hr). A Siemens Trio 3.0-Tesla MRI scanner was used to acquire 8 averages of 60-direction diffusion-weighted images at B = 1000 with isotropic 1.8 mm3 voxels. Diffusion-weighted images were acquired with reversed phase encoding to allow for EPI distortion correction. Five volumes were acquired at B = 0 with no diffusion weighting. T1-weighted images were acquired with 0.8 × 0.8 × 0.8 mm resolution in 18 subjects, 0.7 × 0.7 × 1.0 mm resolution in 47 subjects, and 0.9 × 0.9 × 0.9 mm resolution in 2 subjects. Images are available through the National Chimpanzee Brain Resource at http://www.chimpanzeebrain.org/.

Image preprocessing

Image processing and analysis used the FSL software package59,60,61. T1 images underwent bias correction using FAST62 and brain extraction using BET63. DTI images underwent EPI distortion correction using TOPUP64, eddy-current correction using EDDY64, diffusion tensor fitting using DTIFIT65,66 and brain extraction using BET63. BEDPOSTX was applied to model three fiber populations at each voxel65,66. The resultant Bayesian distribution of fiber populations was sampled probabilistically with PROBTRACKX2 to produce tractography65,66. Tractography parameters were as follows: 5000 samples per voxel; curvature threshold 0.2; fiber threshold 0.1; step length 0.5 mm; step limit 2000; loopcheck and onewaycondition enabled; waycond = AND; wayorder set to seed-waypoint-target. We used bidirectional tractography for each tract: streamlines were first computed from region A to region B, and then the reverse. Streamline density maps (fdt_paths) were then summed and each tract was thresholded at 5% of the combined waytotal for the two runs. The general approach of using bidirectional tractography indexed by summed streamline density maps is similar to the standardized protocol used in XTRACT67, and has been previously used by Bryant, Li10 to create the comprehensive chimpanzee white matter atlas. For visualization, binarized tracts were registered back to template space and further thresholded to only retain voxels present in at least 50% of the population for each tract to produce group-level composite images. In these composite images, intensity at each voxel represents the percent of subjects with above-threshold connectivity at that location. 3D renderings were created using MRIcroGL.

Template creation

The software package ANTS was used to create templates and compute alignments between each subject’s images and the templates68. We created an unbiased T1-weighted template for this dataset using the ANTS script buildtemplateparallel.sh, using the greedy SyN diffeomorphic transformation model and probability mapping similarity metric. We produced an FA template which is aligned with the T1 template using the same approach.

Registration

Masks (described below) were registered to individual subjects’ native diffusion-space FA images using the nonlinear diffeomorphic ANTS transforms computed during the template-building registration process. Accurate alignment of mask images was visually confirmed individually for each dataset.

Masks

Figure 7 illustrates masks used for tractography. Masks were drawn manually on the template. To ensure that masks consisted entirely and only of gray matter voxels in each subject, we computed the intersection between registered template masks and each subjects’ diffusion-space gray matter segmentation, which was produced by thresholding the FA image at 0.2. Varying Boolean logic combinations of the same 3 gray matter masks were used for the arcuate fasciculus, superior longitudinal fasciculus II/III, and ventral pathway, as described below.

-

Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex + ventral premotor cortex: This mask was created by joining masks for ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (Broca’s area) and ventral premotor cortex. The Broca’s area mask is bordered posteriorly by the inferior precentral sulcus, anteriorly by the small sulcus that extends anteriorly from the fronto-orbital sulcus (fos), and superiorly by the inferior frontal sulcus. It encompasses ventral premotor cortex plus the portion of the inferior frontal gyrus corresponding to the pars opercularis and pars triangularis, roughly approximating Brodmann Areas 44 (FCBm) and 45 (FDp), respectively. However, it is important to note that the correspondence between cytoarchitecture and sulcal morphology is variable across individuals, particularly for BA4569. The ventral premotor cortex mask is bordered posteriorly by a vertical line from the lateral sulcus to the superior tip of superior pre-central sulcus (i.e., primary motor cortex), and superiorly by the gyrus that splits the inferior and superior precentral gyri. It corresponds to the ventral portion of BA6. This mask was used as a seed for the arcuate fasciculus, superior longitudinal fasciculus, and ventral pathway.

-

Inferior parietal cortex + superior parietal cortex: This mask was created by joining masks for inferior and superior parietal cortex. The inferior parietal cortex mask is bordered anteriorly by the posterior bank of post-central sulcus. Its posterior border is located at the approximate half-way point of the inferior parietal lobe. It corresponds roughly to cytoarchitectonic areas BA 40 and 7b (PFD and PF). The posterior parietal cortex mask is bordered anteriorly by the posterior bank of postcentral sulcus, and posteriorly by a vertical line drawn up from the termination of the inferior sulcus that extends off the posterior end of the STS. It corresponds approximately to BA 5 (PEm and PEp). This mask was used as a seed for the ventral pathway and superior longitudinal fasciculus and as an exclusion mask for the arcuate fasciculus.

-

Lateral temporal cortex: This mask includes the entirety of the lateral temporal cortex extending from the temporal pole to the junction of the temporal lobe with the occipital lobe, located using the position of the occipital notch. This mask was used as a seed for the arcuate fasciculus and ventral pathway and as an exclusion mask for the superior longitudinal fasciculus.

Additional white matter masks were used as inclusion/exclusion masks for these tracts:

-

Intrahemispheric plane: This mask was placed to intercept interhemispheric streamlines. It was used as an exclusion mask for all tracts.

-

Frontoparietal white matter: Two frontoparietal white matter masks were placed posterior to the central sulcus. The mask immediately posterior to the central sulcus was used as an inclusion mask for superior longitudinal fasciculus tractography, and the mask placed near the posterior end of the lateral sulcus was used as an inclusion mask for the tractography of the arcuate fasciculus.

-

Frontotemporal white matter: This mask was placed in the white matter between the inferior frontal lobe and anterior temporal lobe in the location of the extreme capsule. It was used as an inclusion mask for ventral pathway tractography and exclusion mask for the arcuate fasciculus and superior longitudinal fasciculus.

-

Ventral pathway exclusion mask: This mask was placed in the coronal plane at the same level as the frontotemporal white matter mask. It was used as an exclusion mask for the ventral pathway to avoid subcortical connectivity.

Different masks were used for corticospinal tractography:

-

Corticospinal gray matter seed: This mask includes the primary motor and supplementary motor cortices as well as primary and secondary somatosensory cortex.

-

Superior and inferior white matter: Two masks were placed in the axial slices along the expected path of the corticospinal tract. While the superior mask was placed adjacent to putamen, the inferior mask was placed in the pons.

A Schematic diagram of tracts. The arcuate fasciculus (AF) connects the ventrolateral frontal lobe with the temporal lobe, passing beneath parietal cortex. The ventral pathway (VP) connects the ventrolateral frontal lobe with the temporal lobe. The second and third branches of the superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF II/III) connect the ventrolateral frontal lobe with inferior parietal cortex. B Inclusion and exclusion masks used for AF, SLF, and VP tractography. C Masks used for corticospinal tract (CST) tractography.

The frontal and parietal gray matter masks are equivalent to those used in prior studies70,71. The lateral temporal cortex matter mask is comparable to masks used in ref. 72.

Tractography

Tractography was accomplished using FSL’s probtrackx2 tool using the following parameters: 5000 samples per voxel; curvature threshold 0.2; fiber threshold 0.1; step length 0.5 mm; step limit 2000; loopcheck and onewaycondition enabled; waycond = AND; wayorder set to seed-waypoint-target. We used bidirectional tractography for each tract: streamlines were first computed from region A to region B, and then the reverse. Streamline density maps (fdt_paths) were then summed and each tract was thresholded at 5% of the combined waytotal for the two runs. The general approach of using bidirectional tractography indexed by summed streamline density maps is similar to the standardized protocol used in XTRACT49, and has been previously used by Bryant, Li10 to create the comprehensive chimpanzee white matter atlas. For visualization, binarized tracts were registered back to template space and further thresholded to only retain voxels present in at least 50% of the population for each tract to produce group-level composite images. In these composite images, intensity at each voxel represents the percent of subjects with above-threshold connectivity at that location. 3D renderings were created using MRIcroGL.

Arcuate fasciculus

Bidirectional tractography was run using frontal and temporal seed/target masks, with an inclusion mask in the frontoparietal white matter and exclusion masks in parietal gray matter, frontotemporal white matter, and the mid-sagittal plane.

Superior longitudinal fasciculus II/III

Bidirectional tractography was run using frontal and parietal seed/target masks, with an inclusion mask in frontoparietal white matter and exclusion masks in temporal gray matter, frontotemporal white matter, and the mid-sagittal plane.

Ventral pathway

Bidirectional tractography was run using frontal and temporal seed/target masks, with an inclusion mask in the frontotemporal white matter and exclusion masks in parietal gray matter, frontoparietal white matter, and the mid-sagittal plane.

Corticospinal tract

Bidirectional tractography was run using the corticospinal gray matter mask and inferior white matter mask as seed/target, with an inclusion mask in the superior axial plane and exclusion mask in the mid-sagittal plane.

Tractography quantification

Individual tracts were thresholded at 5% of the summed waytotal. Next, thresholded tractography results from each subject were warped to template space and summed to create group-level composite tracts. These group-level composite tracts were thresholded at 50% of the cohort to retain voxels that were present in at least half of the individuals, and were then binarized, dilated, and made symmetric across hemisphere to create archetype masks. Symmetrical archetypes are necessary in order to ensure that presence/absence of connectivity is being measured within the same voxels of the left and right hemisphere across individuals, to avoid biasing results toward either hemisphere. This is a conservative approach which favors bias toward null results over bias toward positive results. However, please note that the masks used to seed tractography were not symmetrized, ensuring that registration of template space masks to individual diffusion datasets was maximally anatomically accurate. The archetype masks for each tract were projected back into individual space to be used as a logical inclusion mask when quantifying white matter volume and average FA. Only voxels that were part of each individual’s white matter segmentation were used to quantify white matter properties. Similarly, each subject’s gray matter segmentation was used as a logical inclusion mask when calculating volume of gray matter terminations of tracts in ROIs.

Measurement of AG sound production

We used to same criteria for measuring orofacial motor control and the production of AG sounds as described in ref. 33. Each chimpanzee received 6 test trials and they were tested alone. At the onset of each 60 s trial, a human was positioned outside the chimpanzees’ home enclosure ~1 to 1.5 meters from the focal subject. At the start of the trial, a second experimenter would approach the home cage and place a food item (a portion of banana) at a location outside the focal subject’s home cage but between the human and chimpanzee subject. On three trials, the human was facing the focal chimpanzee and on the three remaining trials, the human experimenter was facing away. On each trial, we recorded whether the chimpanzees produced an AG sound within the 60 s time period of each trial. At the end of the trial, the focal chimpanzee was given the piece of banana regardless of their response. Only 1 trial was administered each day and testing continued until all 6 trials were completed. The outcome measure was the percentage of trials on which the chimpanzee produced an AG sound. Based on these, we classified chimpanzees as AG− if they produced zero AG sounds during all 6 trials or AG+ if they produced at least one AG sounds of any of the 6 trials. With this sample, this resulted in 34 AG− (26 females, 8 males) and 33 AG+ apes (19 females, 14 males).

Measurement of manual gesture communication

As an index of volitional communication in the manual gesture modality, we used previously published data from Leavens, Reamer73 to quantify their proficiency in initiating joint attention via a behavioral request (IBR). Briefly, each chimpanzee voluntarily separated from their social group and was temporarily housed in their outdoor enclosure. At the start of the trial, a human experimenter was positioned outside the chimpanzee’s home cage at the extreme left or right side of the enclosure. At the start of the 60 s trial, a second experimenter would approach the outdoor home enclosure and place a half of a banana at the opposite end of the focal subject’s home cage for the position of the human experimenter. We recorded whether the chimpanzees tried to request the food by (1) gesturing toward the food and (2) alternating their gaze between the referent (i.e., the banana) and the human experimenter, and if so, which hand was used. If the chimpanzee gestured toward the food while alternating their gaze between the banana and the experimenter, their response was recorded as “correct”. If the chimpanzees only gestured to the food without alternating their gaze or they alternated their gaze between the experimenter and the food without simultaneously gesturing, their response was recorded as “incorrect”. Each chimpanzee was administered 4 trials that were separated by at least one day. The percentage of correct trials out of 4 was the outcome measure. We classified chimpanzees that responded correctly on 3 or 4 trials above average (AA) and all others as below or average (BA). Based on this criterion, 31 chimpanzees were classified as BA (21 females, 10 males) and 36 as AA (24 females, 12 males). Hand preference data for gestural communication were derived from previously published data by Hopkins et al.53. In this study, a human placed a food outside the chimpanzees’ home enclosure in a unbiased, neutral position. The chimpanzee could request the food by gesturing to it and their hand use was recorded as right or left. Each chimpanzee received 30 trials. Binomial z-scores based the frequency of right and left hand use were computed for each chimpanzee. Chimpanzees with z-scores ≥ 1.96 or z-scores ≤ −1.96 were classified as right and left-handed. All other chimpanzees were classified as ambiguously-handed. Within this sample, there were 38 right-, 14 left- and 7 ambiguously-handed.

Data analysis

For each tract, we quantified the volume and mean FA in each subject’s native diffusion-space. Asymmetry quotients for tract volume and tract FA were calculated using the equation: AQ = 2 × (R−L)/(R + L)69,74,75,76. Hence, positive values indicate rightward asymmetry and negative values indicate leftward asymmetry. Similarly, for the AF, we also computed average and difference values for the gray matter terminations in Broca’s (Broca_GMT) and the ventral premotor (PMv_GMT) regions. The mean and difference values for the AF, SLF, CST, and VP white matter volume and FA values were compared using multiple analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) with each outcome measure as the dependent measures while sex and AG group were the between group factors. For the Broca’s and PMv gray matter means and difference values, we performed a mixed model analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). Region was the repeated measure while sex and AG group were the between group factors. Alpha was set to p < 0.05 and post-hoc analyses, when needed, were performed using Tukey’s Honestly Significance Different (HSD) test.

To control for variation in age across the samples in the dataset, age was included as a covariate in these models.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Source Data are provided with this paper. All source images used for this analysis are publicly available through the National Chimpanzee Brain Resource at https://www.chimpanzeebrain.org/. Specifically, to download data, users may fill out the MRI data request form at https://www.chimpanzeebrain.org/request-tissue-or-mri-data. Data related to Figs. 2–6 is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28668560.

References

Catani, M. & Thiebaut de Schotten, M. A diffusion tensor imaging tractography atlas for virtual in vivo dissections. Cortex 44, 1105–1132 (2008).

Buchel, C. et al. White matter asymmetry in the human brain: a diffusion tensor MRI study. Cereb. Cortex 14, 945–951 (2004).

Vernooij, M. W. et al. Fiber density asymmetry of the arcuate fasciculus in relation to functional hemispheric language lateralization in both right- and left-handed healthy subjects: a combined fMRI and DTI study. NeuroImage 35, 1064–1076 (2007).

Nucifora, P. G. P. et al. Leftward asymmetry in the relative fiber density of the arcuate fasciculus. Neuroreport 16, 791–794 (2005).

Thiebaut de Schotten, M. et al. Atlasing location, asymmetry and inter-subject variability of white matter tracts in the human brain with MR diffusion tractography. Neuroimage 54, 49–59 (2011).

Takao, H. et al. Gray and white matter asymmetries in healthy individuals aged 21-29 years: a voxel-based morphometry and diffusion tensor imaging study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 32, 1762–1773 (2011).

Takao, H., Hayashi, N. & Ohtomo, K. White matter asymmetry in healthy individuals: a diffusion tensor imaging study using tract-based spatial statistics. Neuroscience 193, 291–299 (2011).

Rilling, J. K. et al. The evolution of the arcuate fasciculus revealed with comparative DTI. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 426–428 (2008).

Frey, S., Mackey, S. & Petrides, M. Cortico-cortical connections of areas 44 and 45B in the macaque monkey. Brain Lang. 131, 36–55 (2014).

Bryant, K. L. et al. A comprehensive atlas of white matter tracts in the chimpanzee. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000971 (2020).

Mars, R. B. et al. Concurrent analysis of white matter bundles and grey matter networks in the chimpanzee. Brain Struct. Funct. 224, 1021–1033 (2019).

Rilling, J. K. et al. Continuity, divergence and the evolution of brain language pathways. Front. Evolut. Neurosci. 3, 1–6 (2012).

Balezeau, F. et al. Primate auditory prototype in the evolution of the arcuate fasciculus. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 611–614 (2020).

Hecht, E. E. et al. Process versus product in social learning: comparative diffusion tensor imaging of neural systems for action execution-observation matching in macaques, chimpanzees, and humans. Cereb. Cortex 23, 1014–1024 (2013).

Walsh, S., Bramblett, C. A. & Alford, P. L. A vocabulary of abnormal behaviors in restrictively reared chimpanzees. Am. J. Primatol. 3, 315–319 (1982).

Leavens, D. A., Russell, J. L. & Hopkins, W. D. Multi-modal communication and its social contextual use in captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Anim. Cogn. 13, 33–40 (2010).

Taglialatela, J. P. et al. Social learning of a communicative signal in captive chimpanzees. Biol. Lett. 8, 498–501 (2012).

Watts, D. P. Production of grooming-associated sounds by chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) in Ngogo: variaito, social learning and possible functions. Primates 57, 61–72 (2016).

Leavens, D. A., Taglialatela, J. P. & Hopkins, W. D. in The Evolution of Social Communication in Primates: A Multidisciplinary Approach (eds Pina, M. & Gontier, N.) 179–194 (Springer, 2014).

Theall, L. A. & Povinelli, D. J. Do chimpanzees tailor their gestural signals to fit the attentional state of others? Anim. Cogn. 2, 207–214 (1999).

Liebal, K. et al. To move or not to move: how apes adjust to the attentional state of others. Interact. Stud. 5, 199–219 (2004).

Leavens, D. A. et al. Tactical use of unimodal and bimodal communication by chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes. Anim. Behav. 67, 467–476 (2004).

Hostetter, A. B., Cantero, M. & Hopkins, W. D. Differential use of vocal and gestural communication by chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) in response to the attentional status of a human (Homo sapiens). J. Comp. Psychol. 115, 337–343 (2001).

Hostetter, A. B. et al. Now you see me, now you don’t: evidence that chimpanzees understand the role of the eyes in attention. Anim. Cogn. 10, 55–62 (2007).

Leavens, D. A., Hopkins, W. D. & Bard, K. A. Understanding the point of chimpanzee pointing: Epigenesis and ecological validity. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 14, 185–189 (2005).

Hopkins, W. D., Taglialatela, J. P. & Leavens, D. A. Chimpanzees differentially produce novel vocalizations to capture the attention of a human. Anim. Behav. 73, 281–286 (2007).

Hopkins, W. D., Taglialatela, J. P., & Leavens, D. A. in Primate Communication and Human Language: Vocalisation, Gestures, Imitation and Deixis in Humans and Non-humans (eds Vilain, A., Schwartz, J.-L., Abry, C. & Vauclair, J.) 71–88 (John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2011).

Premack, D. Is language the key to human intelligence? Science 303, 318–320 (2004).

Simonyan, K. The laryngeal motor cortex: its organization and connectivity. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 28, 15–21 (2014).

Figley, C. R. et al. Potential pitfalls of using fractional anisotropy, axial diffusivity, and radial diffusivity as biomarkers of cerebral white matter microstructure. Front. Neurosci. 15, 799576 (2021).

Bianchi, S. et al. Neocortical grey matter distribution underlying voluntary, flexible vocalizations in chimpanzees. Sci. Rep. 6, 34733 (2016).

Hopkins, W. D. in Origins of Human Language: Continuities and Discontinuities with Nonhuman Primates 160–195 (Elsevier, 2018).

Hopkins, W. D. et al. Genetic factors and orofacial motor learning selectively influence variability in central sulcus morphology in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). J. Neurosci. 37, 5475–5483 (2017).

Byrne, R. W. et al. Great ape gestures: intentional communication with a rich set of innate signals. Anim. Cogn. 20, 755–769 (2017).

Corballis, M. C. Language evolution: a changing perspective. Trends Cogn. Sci. 21, 229–236 (2017).

Arbib, M. A., Liebal, K. & Pika, S. Primate vocalization, gesture, and the evolution of human language. Curr. Anthropol. 49, 1053–1063 (2008).

Petkov, C. I. & Jarvis, E. D. Birds, primates, and spoken language origins: behavioral phenotypes and neurobiological substrates. Front. Evol. Neurosci. 4, 12 (2012).

Leavens, D. A. & Hopkins, W. D. Intentional communication by chimpanzees: a cross-sectional study of the use of referential gestures. Dev. Psychol. 34, 813–822 (1998).

Leavens, D. A., Hopkins, W. D. & Bard, K. A. Indexical and referential pointing in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). J. Comp. Psychol. 110, 346–353 (1996).

Leavens, D. A. & Hopkins, W. D. The whole-hand point: the structure and function of pointing from a comparative perspective. J. Comp. Psychol. 113, 417–425 (1999).

Glasser, M. F. & Rilling, J. K. DTI tractography of the human brain’s language pathways. Cereb. Cortex 18, 2471–2482 (2008).

Becker, Y. et al. The Arcuate Fasciculus and language origins: disentangling existing conceptions that influence evolutionary accounts. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 134, 104490 (2022).

Chauvel, M. et al. In vivo mapping of the deep and superficial white matter connectivity in the chimpanzee brain. Neuroimage 282, 120362 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Human torque is not present in chimpanzee brain. Neuroimage 165, 285–293 (2018).

Li, X. et al. Comparison of surface area and cortical thickness asymmetry in the human and chimpanzee brain. Cereb Cortex. 34, bhaa202 (2024).

Vickery, S. et al. Chimpanzee brain morphometry utilizing standardized MRI preprocessing and macroanatomical annotations. Elife. 9, e60136 (2020).

Li, L. et al. Chimpanzee pre-central corticospinal system asymmetry and handedness: a diffusion magnetic reonance imaging study. PLoS ONE 5, e12886 (2009).

Demnitz, N. et al. Right-left asymmetry in corticospinal tract microstructure and dexterity are uncoupled in late adulthood. Neuroimage 240, 118405 (2021).

Angstmann, S. et al. Microstructural asymmetry of the corticospinal tracts predicts right-left differences in circle drawing skill in right-handed adolescents. Brain Struct. Funct. 221, 4475–4489 (2016).

Hopkins, W. D. et al. Within- and between-task consistency in hand use as a means of characterizing hand preferences in captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). J. Comp. Psychol. 127, 380–391 (2013).

Mundy, P. A review of joint attention and social-cognitive brain systems in typical development and autism spectrum disorder. Eur. J. Neurosci. 47, 497–514 (2018).

Allendorfer, J. B. et al. Arcuate fasciculus asymmetry has a hand in language function but not handedness. Hum. Brain Mapp. 37, 3297–3309 (2016).

Hopkins, W. D. et al. The distribution and development of handedness for manual gestures in captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Psychol. Sci. 16, 487–493 (2005).

Hobaiter, C. & Byrne, R. W. Laterality in gestrual communication of wild chimpanzees. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1288, 9–16 (2013).

Hobaiter, C., Byrne, R. W. & Zuberbuhler, K. Wild chimpanzees’ use of single and combined vocal and gestural signals. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 71, 96 (2017).

Hobaiter, C. & Byrne, R. W. The meanings of chimpanzee gestures. Curr. Biol. 24, 1596–1600 (2014).

Roberts, A. I., Roberts, S. G. & Vick, S. J. The repertoire and intentionality of gestural communication in wild chimpanzees. Anim. Cogn. 17, 317–336 (2014).

Hobaiter, C. & Byrne, R. W. The gestural repertoire of the wild chimpanzee. Anim. Cogn. 14, 745–767 (2011).

Smith, S. M. et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation of FSL. NeuroImage 23, 208–219 (2004).

Jenkinson, M. et al. Fsl. Neuroimage 62, 782–790 (2012).

Woolrich, M. W. et al. Bayesian analysis of neuroimaging data in FSL. Neuroimage 45, S173–S186 (2009).

Zhang, Y., Brady, M. & Smith, S. M. Segmentation of the brain MR images through hidden Markov random filed model and expectation-maximization algorithm. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 20, 45–57 (2001).

Smith, S. M. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum. Brain Mapp. 17, 143–155 (2002).

Andersson, J. L., Skare, S. & Ashburner, J. How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage 20, 870–888 (2003).

Behrens, T. E. et al. Characterization and propagation of uncertainty in diffusion-weighted MR imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 50, 1077–1088 (2003).

Behrens, T. E. et al. Probabilistic diffusion tractography with multiple fibre orientations: what can we gain? Neuroimage 34, 144–155 (2007).

Warrington, S. et al. XTRACT - Standardised protocols for automated tractography in the human and macaque brain. Neuroimage 217, 116923 (2020).

Avants, B. B., Tustison, N. & Song, G. Advanced normalization tools (ANTS). Insight J https://doi.org/10.54294/uvnhin (2009).

Schenker, N. M. et al. Broca’s area homologue in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes): probabilistic mapping, asymmetry, and comparison to humans. Cereb. Cortex 20, 730–742 (2010).

Hecht, E. E. et al. Virtual dissection and comparative connectivity of the superior longitudinal fasciculus in chimpanzees and humans. Neuroimage 108, 124–137 (2015).

Hecht, E. E. et al. A neuroanatomical predictor of mirror self-recognition in chimpanzees. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 12, 37–48 (2017).

Hecht, E. E. et al. Differences in neural activation for object-directed grasping in chimpanzees and humans. J. Neurosci. 33, 14117–14134 (2013).

Leavens, D. A. et al. Distal communication by chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes): evidence for common ground? Child Dev. 86, 1623–1638 (2015).

Hopkins, W. D. et al. Motor skill for tool-use is associated with asymmetries in Broca’s area and the motor hand area of the precentral gyrus in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Behav. Brain Res. 318, 71–81 (2017).

Spocter, M. A. et al. Reproducibility of leftward planum temporale asymmetries in two genetically isolated populations of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Proc. Biol. Sci. 287, 20201320 (2020).

Hopkins, W. D. et al. A comprehensive analysis of variability in the sulci that define the inferior frontal gyrus in the chimpanzee () brain. Am. J. Biol. Anthropol. 179, 31–47 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of the animal care and imaging center staff at the Emory National Primate Research Center and the support staff of the Emory Center for Systems Imaging. Additionally, the authors appreciate the support of the staff of the National Chimpanzee Brain Resource, including Mary Ann Cree. This work was funded by NSF 1941626 (W.D.H.), NSF 1631563 (W.D.H.), NSF NCS 2219815 (E.E.H., W.D.H.), NSF NCS 2219739 (E.E.H., W.D.H.), the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (E.E.H.), NIH NS-092988 (W.D.H.), NIH AG-067419 (W.D.H.), NIH NS-073134 (W.D.H.), NIH NS-42867 (W.D.H.), H2020 European Research Council (716931 - GESTIMAGE - ERC-2016-STG) (Y.B.), Initiative d’Excellence d’Aix-Marseille Université (A*Midex AMX-19-IET-004) (Y.B.); Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-17-EURE-0029) (Y.B.) and the Fyssen Foundation (Y.B.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: E.E.H., W.D.H.; methodology: E.E.H., S.V., W.D.H.; software: E.E.H., S.V.; validation: S.V., Y.B., E.E.H.; formal analysis: S.V., E.H.; investigation: W.D.H.; resources: W.D.H., E.E.H.; data curation: W.D.H., S.V., E.E.H.; writing – original draft: E.E.H., W.D.H.; writing – review and editing: E.E.H., W.D.H., S.V., Y.B.; visualization: S.V., W.D.H., E.E.H.; project administration: E.E.H., W.D.H.; funding acquisition: W.D.H., E.E.H.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hecht, E.E., Vijayakumar, S., Becker, Y. et al. Individual variation in the chimpanzee arcuate fasciculus predicts vocal and gestural communication. Nat Commun 16, 3681 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58784-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58784-5