Abstract

The exploration of stable and functional linkages by multicomponent reactions to enrich the stability and diversity of covalent organic frameworks (COFs) and to broaden their potential applications is of fundamental significance to the development of COFs. Herein, we report the facile construction of a set of benzo[f]quinoline-linked COFs (B[f]QCOFs) via one-pot three-component [4 + 2] cyclic condensation of aldehydes and aromatic amines with easy-to-handle triethylamine as the vinyl source. These B[f]QCOFs possess high crystallinity, good physico-chemical stability as well as significant light absorption ability. More importantly, the obtained B[f]QCOF-1 exhibits a superior H2O2 production rate of 9025 μmol g-1 h-1 in pure water without any sacrificial agent under visible-light irradiation, surpassing most of the previously reported COF-based photocatalysts under comparable conditions. This work not only provides a general synthetic route for the preparation of fully conjugated COFs, but also helps the rational design of COF-based photocatalysts for efficient H2O2 photosynthesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Covalent organic frameworks (COFs), first reported by the Yaghi group in 2005, represent an emerging class of advanced crystalline porous materials that integrate both reticular chemistry and dynamic covalent chemistry1,2. Elegant strategies have been developed in the past decades to construct COFs with various types of linkages and the imine-linked COFs have been the most widely studied subclass of COFs for various applications thus far3,4,5,6,7. However, the relatively limited stability and functions of the imine linkages hinder its widespread practical applications to some extent8. In this context, the exploration of robust and functional linkages for COFs has drawn increasing attention in recent years5,9,10. Recently, multicomponent reactions (MCRs), directly combining three or more reactants in one-pot to afford the desired products in an atom-economy route, have been successfully applied to the construction of robust crystalline COFs by combining different reversible or irreversible covalent assemblies11,12,13,14,15. For example, our group has successfully synthesized a set of substituted quinoline-based COFs by employing Povarov and Doebner reactions16,17,18. Noteworthy, these strategies appear to be inaccessible for the synthesis of COFs linked by nonsubstituted quinolines. Very recently, Xiang and coworkers employed the post-synthetic modification (PSM) approach for the successful conversion of imine-based COFs to corresponding nonsubstituted quinoline-linked COFs by a rhodium-catalyzed [4 + 2] annulation in the presence of vinylene carbonate, while the collapse of the framework, decrease of the crystallinity and low yield of the heterogeneous reaction was inevitable19. In this regard, it is necessary to explore efficient chemistry to expand the scope diversity and applications of highly stable nonsubstituted quinoline-based COFs.

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), as a versatile and eco-friendly chemical, has been widely applied in our daily life as well as various chemical industries, and the global demand for H2O2 is rapidly growing year by year20. To date, the state-of-art technology for industrial production of H2O2 is the anthraquinone oxidation process, which needs massive energy and generates lots of hazardous wastes. Consequently, the conflict arising from the growing market demand and the unsustainability of the conventional anthraquinone method has motivated the urgent exploration of more sustainable alternative approaches for efficient H2O2 production21,22. Visible-light driven photocatalysis, which utilizes light energy and certain photocatalyst, offers a promising approach to produce H2O2 and has gained considerable attention owing to its environmental-friendly and sustainable features in recent years23,24. Especially, among various photocatalysts, COFs have emerged as one of the most promising candidates for efficient H2O2 photosynthesis since 2020 benefiting from their structural diversity and tunability, well-defined structures as well as semiconducting properties25,26,27,28,29,30.

More recently, Gao et al. and the Deng group developed a convenient protocol for the preparation of various benzo[f]quinoline molecules with various electron-deficient or electron-efficient groups from aromatic aldehydes, amines and triethylamine with NH4I as the catalyst and di-tert-butyl hydrogen peroxide (DTBP)/O2 as the oxidant31,32. Inspired by these reports, in this study, we successfully designed and synthesized a set of nonsubstituted benzo[f]quinoline-linked COFs (B[f]QCOFs) with excellent crystallinity, stability and light absorption ability via the one-pot three-component [4 + 2] cyclic condensation of different aldehydes, amines and triethylamine. More importantly, the obtained B[f]QCOF-1 exhibited a remarkable H2O2 production rate of 9025 μmol g-1 h-1 in pure water without any sacrificial agent under visible-light irradiation, achieving an apparent quantum yield (AQY) of 8.9% at 450 nm and a solar-to-chemical conversion (SCC) efficiency of 0.23%, superior to the value (~0.10%) for natural synthetic plants. This work not only broadens the synthetic routes of the fully conjugated COFs, but also might shed light on the rational design of COF-based photocatalysts for efficient H2O2 photosynthesis.

Results

Synthesis and characterization of the B[f]QCOFs

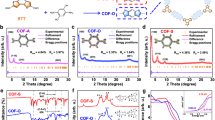

To verify the feasibility of the proposed synthetic strategy, we first synthesized the model compound of 3-phenylbeno[f]quinoline via the one-pot reaction of benzaldehyde, naphthalen-2-amine and triethylamine under mild conditions (Fig. 1a, for details, see the Supplementary Information, Supplementary Figs. 1–4). On this basis, we initially selected the building units of 1,3,5-tris-(4-formyl-phenyl)benzene, naphthalene-2,6-diamine, and triethylamine to construct the benzo[f]quinoline-linked COFs. After extensive screening of various parameters (e.g. solvents, catalysts, oxidants, reaction temperature and time), the corresponding highly crystalline B[f]QCOF-1 was afforded in 78% yield under the optimized conditions (Fig. 1b) at 120 °C for 3 days. To demonstrate the general applicability of this approach, other three COFs, namely B[f]QCOF-2 to B[f]QCOF-4, were also successfully synthesized in high yield (Fig. 1b). For direct comparison, the corresponding imine-based COFs (COF-1 to COF-4) were also synthesized. The successful formation of the nonsubstituted quinoline linkages was firstly verified by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR). Taking B[f]QCOF-1 as an example, compared with the corresponding imine-based COF-1, the attenuation of the C=N stretch at approximately 1620 cm-1 and the appearance of quinolyl species at approximately 1598 cm-1 verified the successful formation of the quinoline rings (Fig. 2a)19,33. Similar observations can also be found in those of B[f]QCOF-2 to B[f]QCOF-4 (Supplementary Figs. 5–7). In addition, the resonance signals at approximate 148 ppm and 155 ppm in the solid-state 13C NMR spectra of all the B[f]QCOFs can be assigned to the carbon atoms of the quinoline ring34,35, while the peak at 168 ppm for B[f]QCOF-2 is related to the carbons of the triazine ring (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Figs. 8–10)36. The formation of quinoline linkages was further supported by X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) analysis (Fig.2c and Supplementary Figs. 11–14). As depicted in Fig. 2c, the peak of N1s at 398.7 ± 0.1 eV is related to the nitrogen of the imine linkages in the corresponding imine-based COF-1, which was shifted to a higher binding energy of 399.5 ± 0.1 eV arising from the nitrogen of the formed quinoline rings in the B[f]QCOF-119,34. Similar results were also observed in the high resolution N1s XPS spectra of other B[f]COFs (Supplementary Figs. 11–13).

a Comparison of the FT-IR spectra of B[f]QCOF-1 and corresponding imine-based COF-1. b The solid state 13C cross polarization magic angle spinning (13C CP/MAS) NMR spectrum of B[f]QCOF-1. Asterisks in the spectrum indicate the ssNMR spinning sidebands. c High resolution N1s XPS spectra of B[f]QCOF-1 and corresponding COF-1. d The experimental, simulated and Pawley refined PXRD patterns for the eclipsed AA stacking mode of B[f]QCOF-1. e The proposed eclipsed structure of B[f]QCOF-1. f N2 adsorption and desorption isotherm of B[f]QCOF-1 measured at 77 K. (Inset: the pore size distribution of B[f]QCOF-1 derived from NLDFT).

The crystalline structures of the obtained B[f]QCOFs were determined by powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) together with simulations using Materials Studio. As shown in Fig. 2d, the intense peak at 2.50°, and other minor peaks at 4.32°, 4.99° and 6.61° in the PXRD pattern of B[f]QCOF-1 correspond to the (100), (110), (200) and (120) facets, respectively, and the simulation calculations indicate that B[f]QCOF-1 preferably possesses the eclipsed AA stacking structure (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Figs. 15 and 16). Pawley refinement afforded the optimized unit cell parameters as a = b = 40.8628, c = 3.4411, α = β = 90°, γ = 120° with the space group of P6/M and excellent agreement factors (Rwp = 4.46%, Rp = 3.37%) (Supplementary Table 1). Similarly, B[f]QCOF-2 and B[f]QCOF-3 adopt the same AA stacking model in the P6/M space group with the lattice parameters of a = b = 40.6592, c = 3.4424, α = β = 90°, γ = 120° (Rwp = 4.43%, Rp = 3.29%) and a = b = 25.8103, c = 3.4373, α = β = 90°, γ = 120° (Rwp = 5.99%, Rp = 4.06%), respectively (Supplementary Figs. 17–24, Supplementary Tables 2, 3), while B[f]QCOF-4 possesses the AA stacking structure in the C2/M space group with the lattice parameters of a = 38.7555, b = 35.1094, c = 3.6237, α = β = γ = 90°, (Rwp = 9.61%, Rp = 6.91%). (Supplementary Figs. 25 and 26 and Supplementary Table 4). SEM and TEM images show uniform morphology of the B[f]QCOFs and thus confirm their phase purity (Supplementary Figs. 27–30). The permanent porosity of these B[f]QCOFs were determined by nitrogen sorption measurements conducted at 77 K (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Figs. 31–33). Before the measurements, the samples were firstly activated by washing with supercritical CO2. Taking B[f]QCOF-1 as an example, the N2 adsorption-desorption isotherm derived the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area and the total pore volume of B[f]QCOF-1 as 756 m2 g−1 and 0.44 cm3 g−1 (P/P0 = 0.99), respectively. The pore size distribution derived from the nonlocal density functional theory model (NLDFT) demonstrates that the pore width is centered at 3.2 nm (Fig. 2f, inset), which is in good agreement with its simulated structure (3.5 nm). Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) revealed that all the B[f]QCOFs can be stable up to 350 °C (Supplementary Figs. 34–37), while their chemical stability was identified by respectively immersing the samples in H2O, DMF, HCl (6 M), NaOH (6 M) and H2O2 (2 M) for 3 days. Afterwards, the samples were characterized by PXRD and FT-IR measurements. The PXRD patterns (Supplementary Figs. 38–41) and FT-IR spectra (Supplementary Figs. 42–45) before and after the experiments of all the B[f]QCOFs exhibited negligible changes, confirming their good chemical stability. Furthermore, the stability of the B[f]QCOFs was further confirmed by measuring its corresponding N2 sorption isotherms after different solvents treatment with B[f]QCOF-1 as the representative sample (Supplementary Fig. 46).

The ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) diffuse reflectance spectra of all the B[f]QCOFs exhibited a broad optical absorbance in the visible light range (400–800 nm) and the corresponding optical band gaps for B[f]QCOF-1 to B[f]QCOF-4 were calculated to be 2.42, 2.51, 2.47 and 2.55 eV, respectively by their Tauc-plots (Figs. 3a, b), indicating their semiconductor characteristics. Moreover, the conduction band (CB) and valence band (VB) positions of all the B[f]QCOFs were determined by the Mott Schottky (M-S) electrochemical measurements combined with the determined optical band gaps (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Figs. 47–50). For instance, the positive slope of the M-S plot for B[f]QCOF−1 indicated its typical n-type semiconductor characteristic and the flat-band potential of B[f]QCOF−1 was calculated to be −0.55 V vs. Ag/AgCl, accordingly, the CB and VB values of B[f]QCOF-1 were obtained to be −0.35 V and +2.07 V, respectively, indicating the thermodynamic feasibility of oxygen reduction reaction (ORR, two-step one-electron process (−0.33 V vs. NHE) and one-step two-electron process ( + 0.68 V vs. NHE) and water oxidation reaction (WOR, +1.76 V vs. NHE) for H2O2 photosynthesis37,38. In order to verify the accuracy of these results, the ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy (UPS) measurements were carried out to determine the HOMO and VB levels of the B[f]QCOFs (Supplementary Fig. 51), from which the HOMO levels of the B[f]QCOFs are determined to be −6.53, −6.55, −6.48 and −6.67 eV, respectively, by subtracting the excitation energy of 21.22 eV from the width of the He I UPS spectrum28. Likewise, the VB levels are obtained to be 2.03, 2.05, 1.98 and 2.17 eV, respectively, which are well consistent with the values obtained by M-S measurements. The water contact angle measurements of the B[f]QCOFs indicate their superhydrophilicity characters (Supplementary Figs. 52–55), which should be beneficial for WOR process29. All these results unambiguously verify that the B[f]QCOFs could be used as effective photocatalysts for full reaction photosynthesis of H2O2 due to their suitable energy band structures and superhydrophilicity. The charge dynamics of all the B[f]QCOFs were investigated by a set of characterization techniques. As can be seen from the EIS Nyquist plots, B[f]QCOF-1 exhibits the smallest semicircle radius among all the COFs, indicating more effective charge-transfer resistance and photogenerated carriers migration ability (Fig. 3d). Under visible-light illumination, all the B[f]QCOFs exhibit fast photocurrent responses with a few reduplicative cycles of intermittent on-off irradiation following the order of B[f]QCOF-1 > B[f]QCOF-3 > B[f]QCOF-2 > B[f]QCOF-4, confirming that B[f]QCOF-1 demonstrates the highest photogenerated carriers transport efficiency and indicating its excellent photogenerated carriers transport efficiency (Fig. 3e). In addition, TRPL spectra reveal the average lifetimes of B[f]QCOF-1 to B[f]QCOF-4 are 1.45 ns, 1.03 ns, 1.08 ns and 1.95 ns, respectively, (Supplementary Fig. 56) suggesting their significant excitons-dissociation efficiency. The steady-state photoluminescence (PL) spectra are further acquired to probe the electron-hole pairs recombination behaviors (Supplementary Fig. 57), in which the B[f]QCOF-1 exhibits the markedly lowered PL emission intensity among all the B[f]QCOFs, suggesting its efficiently impeded charge recombination. Furthermore, the photogenerated charge carriers separation and transfer behavior of all the B[f]QCOFs is investigated by employing surface photovoltage spectroscopy (SPV). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 58, B[f]QCOF-1 exhibits the highest SPV response intensity among all the B[f]QCOFs in the range of 300–520 nm, confirming more excited charges enriched on the surface of B[f]QCOF-1 and indicating that B[f]QCOF-1 is more favorable for charge carriers transfer39, which is in line with the aforementioned steady-state PL results. In addition, the exciton binding energy (Eb), an important parameter for characterizing the interaction forces between excitons, are determined by the temperature-dependent photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 59). The results, presented in the inset of Fig. 3f, indicate that B[f]QCOF-1 exhibits thermal PL quenching with the temperature ranging from 293 K to 430 K. The Eb values of the B[f]QCOFs are determined to be 93, 156, 145 and 306 meV, respectively, by fitting the integrated PL intensities as functions of temperature to the Arrhenius equation28. The lowest Eb value of B[f]QCOF-1 suggests its highest exciton dissociation efficiency among all the COFs, which is consistent with the above steady-state PL results. To gain insight into the process of charge carrier separation and transfer dynamics, femtosecond time-resolved transient absorption (fs-TA) spectroscopy experiments were performed for the B[f]QCOFs (Fig. 3g–i and Supplementary Fig. 60). All the spectra exhibit a broad negative bleaching signal in the range of 400–500 nm, which can be assigned to the ground state bleach (GSB) process, corresponding to the generation of excited electrons40. The distinct positive broad absorption from 500 to 650 nm is related to the excited-state absorption (ESA) signals41 and among all the B[f]QCOFs, B[f]QCOF-1 exhibits the strongest and longest-lived absorption for ESA, confirming the most effective separation of charge carriers and promoting the interactions between the excited electrons and oxygen molecules. The kinetics fitting results of the B[f]QCOFs show biexponential decay processes, namely the short lifetime (τ1) and long lifetime (τ2), corresponding to electron trapping and electron transfer kinetics, respectively42. According to the kinetics profiles, B[f]QCOF-1 demonstrates a longer average lifetime (τavg = 162 ps) than those of other three B[f]QCOFs (122 ps for B[f]QCOF-2, 134 ps for B[f]QCOF-3, 101 ps for B[f]QCOF-4), indicating a higher efficiency of exciton dissociation and charge transfer.

a The UV-Vis DRS of the B[f]QCOFs. b The Tauc plots of the B[f]QCOFs for band gap calculation. c The experimentally derived energy band alignments of the B[f]QCOFs. d Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) Nyquist plots of the B[f]QCOFs. e Comparison of the photocurrent response of the B[f]QCOFs. f Temperature-dependent PL spectra of B[f]QCOF-1 excited at 340 nm for the determination of binding energy (Eb). g, h The femtosecond time-resolved transient absorption (fs-TA) spectra of the B[f]QCOF-1. i The TA delay kinetic profile of B[f]QCOF-1.

Photosynthesis of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)

The photocatalytic H2O2 production performance of all the obtained B[f]QCOFs is investigated in pure O2-saturated water without any sacrificial agent under visible-light irradiation (300 W Xe lamp, λ ≥ 420 nm) at room temperature (Supplementary Fig. 61). As shown in Fig. 4a, the amount of produced H2O2 steadily increases with the extension of irradiation time for all the B[f]QCOFs, indicating their excellent photocatalytic activities, and the average hydrogen peroxide evolution rate of B[f]QCOF-1 to B[f]QCOF-4 reaches approximately 9025, 5302, 5712 and 2540 μmol g−1 h−1, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 62, 63). By contrast, their corresponding imine-based COFs exhibit relatively much lower H2O2 production rates of 6069, 4258, 3795 and 1101 μmol g-1 h-1, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 64). Moreover, the hydrogen peroxide evolution rate of B[f]QCOF-1 can reach up to 11338 μmol g−1 h−1 with ethanol as the sacrificial agent (Supplementary Fig. 65). To further evaluate the light utilization efficiency of B[f]QCOF-1 in pure water, the apparent quantum yield (AQY) was measured under monochromatic light irradiation (Fig. 4b). The AQY of B[f]QCOF-1 at 450 nm reaches 8.9%, surpassing most of previously reported COFs and exhibiting decreasing trends in AQY with the increase of wavelength, which aligns with the variation of the visible-light absorption spectrum. Moreover, the solar-to-chemical conversion (SCC) efficiency of B[f]QCOF-1 reaches 0.23%, which is superior to the value for natural synthetic plants (~0.10%). In addition, we have also examined the photocatalytic performances of all the B[f]QCOFs under different lights irradiation and in different kinds of water sources (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 66). All the B[f]QCOFs exhibit the best photocatalytic performances in pure water under Xenon lamp irradiation at room temperature. For example, the B[f]QCOF-1 exhibit the H2O2 production rate of 9025 (5060), 6737, 6034 and 5714 μmol g-1 h-1, respectively in pure water (under natural sunlight irradiation), Daming Lake water, Baotu Spring water and Bohai Bay seawater without any sacrificial agent under Xenon lamp irradiation, ranking the top levels among all the reported COF-based materials under identical conditions (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Table 5). The lower performance of the B[f]QCOFs in natural seawater in comparison with other water sources is mainly attributed to the higher content of ions and contaminants in seawater, which maybe corrode the photocatalyst, thus leading to the decreased photocatalytic performances of the COFs43,44. These results clearly demonstrate that the B[f]QCOFs can efficiently produce H2O2 in a variety of real water samples26,27. The formation and decomposition of H2O2 are two competitive pathways, while the photocatalytic decomposition experiments of H2O2 (2 mM) indicate that B[f]QCOFs barely degrade H2O2 as the amount of H2O2 can keep over 95% of its initial concentration under visible-light irradiation for 1 h (Supplementary Fig. 67), favoring the continuous photosynthesis of H2O2 over the B[f]QCOFs. In addition, the comparison of the formation (Kf) and decomposition (Kd) rate constants of H2O2 is separately evaluated and the results are listed in Fig. 4e. Remarkably, among all the B[f]QCOFs, B[f]QCOF-1 exhibits the highest Kf, while these B[f]QCOFs shows similar Kd values, thus resulting in the highest photocatalytic performance of B[f]QCOF-1. Furthermore, the promising stability of B[f]QCOF-1 is evaluated by comparison with the corresponding imine-based COF-1, where the photocatalytic activity of B[f]QCOF-1 could be maintained with negligible loss after even ten consecutive cycles, while the photocatalytic performance of COF-1 starts to decrease even after five repeated cycles and the H2O2 production rate drops to only 4000 μmol g−1 h−1 after ten cycles, which is mainly attributed to the relatively lower stability of the imine-based COF-1 (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 68). Besides, the structure and morphology of the spent B[f]QCOF-1 after ten consecutive photocatalytic cycles are largely reserved (Supplementary Figs. 69 and 70), suggesting that B[f]QCOF-1 could serve as an efficient and stable photocatalyst for H2O2 photosynthesis. The long-term photocatalytic performances of the B[f]QCOFs were performed in pure water without any sacrificial agent under visible-light irradiation for consecutive 12 h. As depicted in Supplementary Fig. 71, the amount of H2O2 gradually accumulates within 10 h, afterwards, it starts to decrease, which is mainly attributed to the decrease of the catalytic activity due to the gradual loss of the crystallinity of the photocatalysts under long-term continuous light irradiation as well as the accelerated decomposition of H2O2 with the accumulation of the produced H2O245,46, as evidenced by the corresponding H2O2 decomposition experiments in O2 and the PXRD detection over time (Supplementary Figs. 72–74).

a Time-dependent H2O2 production curves of all the B[f]QCOFs under visible-light irradiation over 2 h. b AQYs of B[f]QCOF-1 at different selected wavelengths (450, 475, 520, 550, 600, 650 nm). Error bars indicate the error in the measurement. c The photocatalytic performances of all the B[f]QCOFs in different kinds of water under Xenon lamp irradiation. d The photocatalytic performance of the B[f]QCOFs in comparison with reported COF-based photocatalysts. e The formation (Kf) and decomposition (Kd) rate constants of H2O2 for B[f]QCOF-1. f Recycling experiments involving the photocatalytic production of H2O2 with B[f]QCOF-1 as the photocatalyst. g The control experiments showing the H2O2 production performance of B[f]QCOF-1 under various conditions. BA Benzyl alcohol, TEMPOL 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-N-oxyl.

Mechanism investigation of the B[f]QCOFs

To explore the possible reaction mechanism, a set of control experiments are firstly carried out with B[f]QCOF-1 as the representative photocatalyst under different conditions. As depicted in Fig. 4g, no hydrogen peroxide is detected without visible-light irradiation or the absence of B[f]QCOF-1 photocatalyst, disclosing the necessary of light and the photocatalyst nature of B[f]QCOF-1 in the H2O2 photosynthesis. The H2O2 production rate over B[f]QCOF-1 dramatically decreases from 9025 μmol g−1 h−1 to 7365 μmol g−1 h−1 and 1249 μmol g−1 h−1 when O2 is replaced by air or argon, respectively, suggesting that the oxygen reduction reaction is predominantly involved in H2O2 photosynthesis coupled with the existence of water oxidation reaction. When benzyl alcohol (BA) is added as the hole scavenger, a noticeable increase of the H2O2 production rate is observed. To further confirm the involvement of water oxidation reaction, we added AgNO3 as an electron scavenger to suppress H2O2 production via the ORR pathway under argon atmosphere47. Typically, the H2O2 production rate is obtained to be 1249 μmol g-1 h-1, while the H2O2 production rate is almost unchanged after the addition of AgNO3, confirming the WOR pathway for H2O2 production. Meanwhile, after the addition of typical hydroxyl radical scavenger (tert-butyl alcohol, TBA), the H2O2 yield also keeps unchanged, ruling out the participation of hydroxyl radicals in the formation of H2O2 (Supplementary Fig. 75). Moreover, the involvement of ORR and WOR pathways for H2O2 production is validated by isotopic experiments. For the ORR reaction pathway, B[f]QCOF-1 was irradiated in H216O and 18O2 for 12 h. After removing the unreacted gas with argon gas, MnO2 was added to the reaction system to covert H2O2 to O2 and the released gas was analyzed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (Agilent GC8890/5977BGC/MSD). As shown in Fig. 5a, the presence of 16O2 and 18O2 verifies the simultaneous ORR and WOR reaction pathways. In addition, the involvement of two-electron WOR pathway is further validated by employing argon saturated H218O as the water resource or employing H218O and 16O2 as the resource. The absence of 18O2 in the gas phase undoubtfully excludes the four-electron WOR pathway to produce O2 and the presence of 18O2 after converting H2O2 to O2 confirms the two-electron WOR pathway (Supplementary Fig. 76).

a The isotopic experiments with B[f]QCOF-1 as the photocatalyst in the presence of H216O and 18O2. b The EPR spectra of B[f]QCOF-1 under darkness and light with DMPO as the spin-trap agent. c The Koutechy-Levich plots of the B[f]QCOFs obtained from the RDE measurements. d RRDE voltammograms of B[f]QCOF-1 with a potential of −0.23 V vs. Ag/AgCl on Pt ring electrode to detect O2. e RRDE voltammograms of B[f]QCOF-1with a potential of 0.60 V vs. Ag/AgCl on Pt ring electrode to detect H2O2. f In-situ DRIFTS spectra of B[f]QCOF−1 during H2O2 photosynthesis over 60 min. g The HOMO and LUMO orbital distributions of the simplified B[f]QCOF−1 segments based on DFT calculation and corresponding electrostatic potential surface (ESP) maps of the B[f]QCOF-1 models. h Gibbs free energy diagram for oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) into H2O2 over the B[f]QCOFs. i Gibbs free energy diagram for water oxidation reaction (WOR) into H2O2 over the B[f]QCOFs.

Given that both O2 reduction and H2O oxidation are involved in H2O2 photosynthesis, electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy was performed using 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) as the spin-trap agent to identify the possible intermediates during the H2O2 photosynthesis reaction48. As shown in Fig. 5b and Supplementary Figs. 77–79, the typical six and four characteristic signals for DMPO-*O2− and DMPO-*OH are observed for all the B[f]QCOFs under light irradiation, while no peaks can be observed in dark, indicating the generation of *OOH and *OH intermediate species during the reaction28,48,49, while the formation of •OH is possibly originated from the decomposition of photogenerated H2O2 under visible light irradiation50. Moreover, the generation of •O2− was further validated by the probe experiments with nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) and the photocatalytic yield of •O2− during the photocatalytic process is calculated to be 8.8 × 10−5 M for B[f]QCOF-1 within 1 h (Supplementary Fig. 80). In addition, when 4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-N-oxyl (TEMPOL), the quenching agent of •O2−, was added to the reaction solutions under oxygen atmosphere, the H2O2 production rate significantly decreased to 3056 μmol g−1 h−1 owing to the decrease of the •O2− (Fig. 4g), further verified the indirect two-electron ORR pathway. Rotating disk electrode (RDE) tests at different rotational speeds were performed on all the B[f]QCOFs and the results unveil that the average electron transfer numbers of B[f]QCOF-1 to B[f]QCOF-4 are 2.09, 2.21, 2,19 and 2.28, respectively, (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Figs. 81–84) identifying their high selectivity towards two-electron ORR pathway. Moreover, the results of rotating ring disk electrode (RRDE) also demonstrate the two-electron ORR pathway (Supplementary Fig. 85). To investigate the WOR process on B[f]QCOF-1, the RRDE tests were carried out under argon condition with the potential scanning range of 1.2–2.4 V vs. Ag/AgCl for the rotating disk electrode. As depicted in Fig. 5d, e, no reduction currents are clearly observed at the Pt ring electrode when a constant potential of −0.23 V vs. Ag/AgCl is applied on the Pt ring electrode, excluding the generation of O2 via four-electron WOR process51, while significant oxidation current appeares when the potential of the Pt ring electrode is changed to an oxidative potential of +0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl, verifying the two-electron WOR process on B[f]COF-137,48. Both RDE and RRDE results clearly confirm that B[f]QCOF-1 undergoes both two-electron ORR and two-electron WOR pathways for the photocatalytic production of H2O2.

To get more insight into the reaction process, in-situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) measurements are performed to reveal the real-time intermediates during the photocatalytic process. Figure 5f depicts the time-dependent DRIFTS spectra of B[f]QCOF-1 in O2-saturated conditions with water vapor and under visible-light irradiation. As can be seen from Fig. 5f, the signals at 878 and 912 cm−1 (O-O bonding), the signal at 1189 cm−1 (•O2− species) and the signal at 1263 cm−1 (endo-peroxide intermediate species), steadily increase with the irradiation time, suggesting the formation of *OOH intermediate species and the two-step single-electron ORR pathway29,52. Furthermore, the appearance of the signals corresponding to the C-OH (1092 cm−1) and O-H (1404 cm−1) confirm the formation of *OH species and the WOR process for the studied photocatalytic system28,48. These results further confirm that the photocatalytic mechanism of B[f]QCOF-1 for H2O2 photosynthesis is the synergistic effects of ORR and WOR pathways. To gain a deeper understanding of the reaction mechanism, DFT calculations are employed to elucidate the ORR and WOR pathways. We firstly conduct the DFT calculations to determine the HOMO and LUMO orbital distributions of the simplified B[f]QCOFs segments, and further obtain the surface electrostatic potential (ESP) distribution maps of the B[f]QCOFs (Fig. 5g and Supplementary Figs. 86 and 87), which clearly demonstrate the electron distribution in the COF segments. Taking B[f]QCOF-1 as an example, the LUMO of B[f]QCOF-1 is mainly located on the formed benzo[f]quinoline, while the HOMO is delocalized over the entire repeating unit. As for the electrostatic potential distribution map of B[f]QCOF-1, more electrons are around the quinoline and adjacent benzene ring, which are likely to be the active sites for O2 adsorption and promoting photocatalytic oxygen reduction (Fig. 5g). Afterwards, the adsorption configurations of the B[f]QCOFs towards O2 at various sites are optimized (Supplementary Fig. 88). The results exhibit that the benzene ring nearest the quinoline linkage serves as the active site for O2 adsorption apart from B[f]QCOF-2, in which the triazine ring is obtained to be the active O2 adsorption site. Meanwhile, the quinoline ring is calculated to be the favorable site for the adsorption and conversion of H2O for all the B[f]QCOFs (Supplementary Fig. 89). Consequently, the Gibbs free energy diagrams for ORR and WOR pathways over all the B[f]QCOFs are calculated (Fig. 5h, i). Significantly, B[f]QCOF-1 possesses both the lowest ΔG value for *OOH formation and for *OH formation among all the COFs, which is in accordance with the experimental results that B[f]QCOF-1 exhibits the best photocatalytic performance. Based on the above experimental and theoretical calculations, a possible mechanism is proposed as follows. Under visible-light irradiation, the B[f]QCOFs can facilitate the separation of photogenerated electrons and holes. On the one hand, the electrons transfer to the CB and involve in the ORR pathway to produce H2O2. On the other hand, the photogenerated holes accumulate on the VB will participate in the WOR process to generate H2O2 (Supplementary Fig. 90). In a word, H2O2 can be generated from both O2 and H2O via integrated dual-channel pathways in this studied system.

Discussion

In summary, we have successfully designed and synthesized a set of fully conjugated benzo[f]quinoline-linked COFs via one-pot three-component [4 + 2] cyclic condensation of aldehydes and aromatic amines with triethylamine as the vinyl source. These obtained B[f]QCOFs possess high crystallinity and physicochemical stability. More importantly, the obtained B[f]QCOF-1 exhibits a superior H2O2 production rate of 9025 μmol g−1 h−1 in pure water without any sacrificial agent under visible-light irradiation (λ ≥ 420 nm), outperforming almost all the previously reported COF-based photocatalysts under comparable conditions. We believe that this work not only enriches the synthetic route for the construction of robust fully conjugated COFs, but also helps the rational design of high-performance COF-based photocatalysts for efficient H2O2 photosynthesis.

Methods

Synthesis of B[f]QCOF-1

To a 10 mL Pyrex tube was added 1,3,5-tris(p-formylphenyl)benzene (15.6 mg, 0.04 mmol), naphthalene-2,6-diamine (9.5 mg, 0.06 mmol) and ammonium iodide (34.8 mg, 0.24 mmol). Then, di-tert-butyl peroxide (45 μL, 0.24 mmol), triethylamine (67 μL, 0.36 mmol) and anhydrous 1,2-dichlorobenzene (o-DCB, 1.0 mL), anhydrous EtOH (1.0 mL) were added. Afterwards, the mixture was homogenized by sonication for 10 min. Then, acetic acid (6 M, 0.2 mL) was added and the Pyrex tube was flame-sealed and heated in an oven at 120 °C for 3 days. After cooling down to room temperature, the precipitate was collected by centrifugation and washed with N, N-dimethylformamide, THF, acetone and dried under vacuum at 100 °C to afford the dark green powders (21 mg, 78%).

Synthesis of B[f]QCOF-2

To a 10 mL Pyrex tube was added 4,4’,4”-(1,3,5-triazine-2,4,6-triyl)tribenzaldehyde (15.7 mg, 0.04 mmol), naphthalene-2,6-diamine (9.5 mg, 0.06 mmol) and ammonium iodide (34.8 mg, 0.24 mmol). Then, di-tert-butyl peroxide (45 μL, 0.24 mmol), triethylamine (67 μL, 0.36 mmol) and anhydrous 1,2-dichlorobenzene (o-DCB, 1.0 mL), anhydrous EtOH (1.0 mL) were added. Afterwards, the mixture was homogenized by sonication for 10 min. Then, acetic acid (6 M, 0.2 mL) was added and the Pyrex tube was flame-sealed and heated in an oven at 150 °C for 3 days. After cooling down to room temperature, the precipitate was collected by centrifugation and washed with N, N-dimethylformamide, THF, acetone and dried under vacuum at 100 °C to afford the dark green powders (23 mg, 85%).

Synthesis of B[f]QCOF-3

To a 10 mL Pyrex tube was added benzene-1,3,5-tricarbaldehyde (13.0 mg, 0.08 mmol), naphthalene-2,6-diamine (19.0 mg, 0.12 mmol) and ammonium iodide (69.6 mg, 0.48 mmol). Then, di-tert-butyl peroxide (90 μL, 0.48 mmol), triethylamine (134 μL, 0.72 mmol) and anhydrous 1,2-dichlorobenzene (o-DCB, 1.0 mL), anhydrous EtOH (1.0 mL) were added. Afterwards, the mixture was homogenized by sonication for 10 min. Then, acetic acid (6 M, 0.2 mL) was added and the Pyrex tube was flame-sealed and heated in an oven at 120 °C for 3 days. After cooling down to room temperature, the precipitate was collected by centrifugation and washed with N, N-dimethylformamide, THF, acetone and dried under vacuum at 100 °C to afford the dark green powders (28.5 mg, 81%).

Synthesis of B[f]QCOF-4

To a 10 mL Pyrex tube was added 4,4’,4”,4”‘-(pyrene-1,3,6,8-tetrayl)tetrabenzaldehyde (18.5 mg, 0.03 mmol), naphthalene-2,6-diamine (9.5 mg, 0.06 mmol) and ammonium iodide (34.8 mg, 0.24 mmol). Then, di-tert-butyl peroxide (45 μL, 0.24 mmol), triethylamine (67 μL, 0.36 mmol) and anhydrous 1,2-dichlorobenzene (o-DCB, 0.9 mL), anhydrous EtOH (1.0 mL) were added. Afterwards, the mixture was homogenized by sonication for 10 min. The, acetic acid (6 M, 0.2 mL) was added and the Pyrex tube was flame-sealed and heated in an oven at 120 °C for 3 days. After cooling down to room temperature, the precipitate was collected by centrifugation and washed with N, N-dimethylformamide, THF, acetone and dried under vacuum at 100 °C to afford the yellowish-brown powders (25 mg, 82%).

Photocatalytic H2O2 production

Typically, the activated COFs (B[f]QCOF-X, 10 mg) and water (50 mL) were introduced into a hermetically sealed device, a quartz tube with a cap. The suspension was bubbled with continuous oxygen and stirred in dark for 30 min to reach the adsorption-desorption balance before the photocatalytic test was performed. Afterwards, the O2-saturated suspension was illuminated under a 300 W Xenon lamp (PLS-SEX 300, Beijing Perfectlight, China) and the reaction temperature was maintained via the water chiller system. At designed intervals (e.g. 1 h, 2 h, 3 h and 4 h irradiation), 3 mL of the reaction suspension was collected and filtrated with a 0.22 μm membrane filter. The liquid solution was well-mixed with the pre-prepared titanium sulfate solution and the absorption spectra were detected by UV-Vis spectrophotometer. After the photocatalytic experiments, the B[f]QCOFs were recovered by centrifugation and thoroughly washed with water and ethanol for three times and dried under vacuum at 120 °C for 12 h before next experiments.

Isotope labeling experiments

(a) Oxygen reduction reaction: In a typical experiment, a 15 mL vial was charged with 5 mg of the activated B[f]QCOF photocatalysts and 8 mL of H216O and the vial was subsequently sealed with a rubber septum, followed by purging with argon for 1 hour to remove the remaining 16O2. Afterwards, 18O2 (purity: 99%, 10 mL) was injected into the vial via a syringe, which was irradiated by a 300 W Xenon lamp (λ ≥ 420 nm filter) for 12 h, and the 18O2 gas was further removed by purging with argon, while the reaction solution was transferred to another vial containing MnO2 and argon, and the produced gas during the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide was analyzed by employing the Agilent GC8890 /5977BGC/MSD system.

(b) Water oxidation reaction: The activated photocatalyst (5 mg) were added to a 15 mL custom reaction tube containing 8 mL H218O. After purging with argon for 1 h to remove all the air in the solution, the reaction was carried out under 300 W Xenon lamp (λ ≥ 420 nm filter) irradiation for 12 h and was analyzed using the Agilent GC8890 /5977BGC/MSD system.

Calculation method

All theoretical calculations were performed using Gaussian 09 program53. The geometries were optimized at the B3LYP54,55,56/6-31 + G(d) level. Optimized molecular stereoscopic structure figures were prepared using CYLView57. Frontier molecular orbitals and the graphs of atomic charges were visualized with VMD58. The excitation states were further computed using time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) calculations. The first excited states of the fragments were analyzed using the Multiwfn 3.8 (dev) program58,59.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Côté, A. P. et al. Porous, crystalline, covalent organic frameworks. Science. 310, 1166 (2005).

Yaghi, O. M. et al. Reticular synthesis and the design of new materials. Nature. 423, 705–714 (2003).

Wang, H. et al. Covalent organic framework photocatalysts: structures and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 4135–4165 (2020).

Wang, G.-B. et al. Covalent organic frameworks: emerging high-performance platforms for efficient photocatalytic applications. J. Mater. Chem. A. 8, 6957–6983 (2020).

Li, X. et al. Chemically robust covalent organic frameworks: progress and perspective. Matter 3, 1507–1540 (2020).

Wang, G.-B. et al. Construction of covalent organic frameworks via a visible-light-activated photocatalytic multicomponent reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 4951–4956 (2023).

Das, P. et al. Integrating bifunctionality and chemical stability in covalent organic frameworks via one-pot multicomponent reactions for solar-driven H2O2 production. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 2975–2984 (2023).

Qian, C. et al. Imine and imine-derived linkages in two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 881–898 (2022).

Geng, K. et al. Covalent organic frameworks: design, synthesis, and functions. Chem. Rev. 120, 8814–8933 (2020).

Wang, J.-R. et al. Robust links in photoactive covalent organic frameworks enable effective photocatalytic reactions under harsh conditions. Nat. Commun. 15, 1267 (2024).

Guan, Q. et al. Construction of covalent organic frameworks via multicomponent reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 1475–1496 (2023).

Dömling, A. et al. Chemistry and biology of multicomponent reactions. Chem. Rev. 112, 3083–3135 (2012).

Zhang, Z.-C. et al. Rational synthesis of functionalized covalent organic frameworks via four-component reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 4822–4829 (2024).

Wang, P.-L. et al. Constructing robust covalent organic frameworks via multicomponent reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 18004–18008 (2019).

Wang, J.-C. et al. Catalytic asymmetric wynthesis of chiral covalent organic frameworks from prochiral monomers for heterogeneous asymmetric catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 16915–16920 (2020).

Li, X.-T. et al. Construction of covalent organic frameworks via three-component one-pot strecker and povarov reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 6521–6526 (2020).

Li, X.-T. et al. Construction of acid–base bifunctional covalent organic frameworks via doebner reaction for catalysing cascade reaction. Chem. Commun. 58, 2508–2511 (2022).

Ding, L.-G. et al. Covalent organic framework based multifunctional self-sanitizing face masks. J. Mater. Chem. A. 10, 3346–3358 (2022).

Zhao, X. et al. Construction of ultrastable nonsubstituted quinoline-bridged covalent organic frameworks via rhodium-catalyzed dehydrogenative annulation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202208833 (2022).

Freese, T. et al. An organic perspective on photocatalytic production of hydrogen peroxide. Nat. Catal. 6, 553–558 (2023).

Campos-Martin, J. M. et al. Hydrogen peroxide synthesis: an outlook beyond the anthraquinone process. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 6962–6984 (2006).

Sun, Y. et al. A comparative perspective of electrochemical and photochemical approaches for catalytic H2O2 production. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 6605–6631 (2020).

Hou, H. et al. Production of hydrogen peroxide by photocatalytic processes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 17356–17376 (2020).

Liu, T. et al. Overall photosynthesis of H2O2 by an inorganic semiconductor. Nat. Commun. 13, 1034 (2022).

Krishnaraj, C. et al. Strongly reducing (diarylamino)benzene-based covalent organic framework for metal-free visible light photocatalytic H2O2generation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 20107–20116 (2020).

Xie, K.-H. et al. Covalent organic framework based photocatalysts for efficient visible-light driven hydrogen peroxide production. Inorg. Chem. Front. 11, 1322–1338 (2024).

Yong, Z. et al. Solar-to-H2O2 catalyzed by covalent organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202308980 (2023).

Chang, J.-N. et al. oxidation-reduction molecular junction covalent organic frameworks for full reaction photosynthesis of H2O2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218868 (2023).

Liu, R. et al. Linkage-engineered donor–acceptor covalent organic frameworks for optimal photosynthesis of hydrogen peroxide from water and air. Nat. Catal. 7, 195–206 (2024).

Das, P. et al. Solar light driven H2O2 production and selective oxidations using a covalent organic framework photocatalyst prepared by a multicomponent reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202304349 (2023).

Gao, Q. et al. Deaminative cyclization of tertiary amines for the synthesis of 2-arylquinoline derivatives with a nonsubstituted vinylene fragment. Org. Lett. 25, 109–114 (2023).

Ma, Y. et al. Three-component synthesis of 2-substituted quinolines and benzo[f]quinolines using tertiary amines as the vinyl source. J. Org. Chem. 88, 2952–2960 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Facile transformation of imine covalent organic frameworks into ultrastable crystalline porous aromatic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 9, 2998 (2018).

Pang, H. et al. One-pot cascade construction of nonsubstituted quinoline-bridged covalent organic frameworks. Chem. Sci. 14, 1543–1550 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. Constructing chemical stable 4-carboxyl-quinoline linked covalent organic frameworks via Doebner reaction for nanofiltration. Nat. Commun. 13, 2615 (2022).

Wang, G.-B. et al. Rational design of benzodifuran-functionalized donor–acceptor covalent organic frameworks for photocatalytic hydrogen evolution from water. Chem. Commun. 57, 4464–4467 (2021).

Zhi, Q. et al. Piperazine-linked metalphthalocyanine fameworks for highly efficient visible-light-driven H2O2 photosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 21328–21336 (2022).

Chen, D. et al. Covalent organic frameworks containing dual O2 reduction centers for overall photosynthetic hydrogen peroxide production. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202217479 (2023).

Fang, L. et al. Autocatalytic interfacial synthesis of self-standing amide-linked covalent organic framework membranes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 64, e202423220 (2025).

Zhou, E. et al. Cyanide-based covalent organic frameworks for enhanced overall photocatalytic hydrogen peroxide production. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202400999 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Molecular heptazine–triazine junction over carbon nitride frameworks for artificial photosynthesis of hydrogen peroxide. Adv. Mater. 35, 2306831 (2023).

Li, P. et al. 1D covalent organic frameworks triggering highly efficient photosynthesis of H2O2 via controllable modular design. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202319885 (2024).

Xu, Y. et al. Bioinspired photo-thermal catalytic system using covalent organic framework-based aerogel for synchronous seawater desalination and H2O2 production. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202421990 (2025).

Zhu, K. et al. Low-grade waste heat enables over 80 L m-2 h−1 interfacial steam generation based on 3D superhydrophilic foam. Adv. Mater. 35, 2211932 (2023).

Wu, Q. et al. A metal-free photocatalyst for highly efficient hydrogen peroxide photoproduction in real seawater. Nat. Commun. 12, 483 (2021).

Yue, J.-Y. et al. Thiophene-containing covalent organic frameworks for overall photocatalytic H2O2 synthesis in water and seawater. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202309624 (2023).

Peng, H. et al. Defective ZnIn2S4 nanosheets for visible-light and sacrificial-agent-free H2O2 photosynthesis via O2/H2O. redox. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 27757–27766 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. 12 Connecting sites linked three-dimensional covalent organic frameworks with intrinsic non-interpenetrated shp topology for photocatalytic H2O2 synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202401014 (2024).

Wu, C. et al. Polarization engineering of covalent triazine frameworks for highly efficient photosynthesis of hydrogen peroxide from molecular oxygen and water. Adv. Mater. 34, 2110266 (2022).

Luo, X. et al. Functionalized modification of conjugated porous polymers for full reaction photosynthesis of H2O2. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2415244 (2024).

Kou, M. et al. Molecularly engineered covalent organic frameworks for hydrogen peroxide photosynthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202200413 (2022).

Li, L. et al. Custom-design of strong electron/proton extractor on COFs for efficient photocatalytic H2O2 production. Angew. Chem. In.t Ed. 63, e202320218 (2024).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 09, Revision D.01 (Gaussian, Inc., 2009).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A. 38, 3098–3100 (1988).

Becke, A. D. et al. Density‐functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648–5652 (1993).

Lee, C. et al. Development of the colle-salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B. 37, 785–789 (1988).

Legault, C. CYLview20. User Manual (Legault, C. Y., Université de Sherbrooke, 2012).

Humphrey, W. et al. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38 (1996).

Lu, T. et al. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22371172 and 22171169), the Taishan Scholars Climbing Program of Shandong Province, the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2024MB119 and ZR2024MB161) and the Youth Innovation Science and Technology Program of Higher Education Institution of Shandong Province (No. 2023KJ194). The authors are grateful to Dr. Cong-Xue Liu from Pohang University of Science and Technology for constructive discussion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.-B.D. led the project. K.-H.X. and F.Z. synthesized and characterized the samples, performed experiments and data analysis. G.-B.W. and Y.G. conceived the idea, supervised the experimental work, interpreted the results and wrote the paper. J.-L.K., F.H. and Z.-Z.C. conducted the structural simulations and DFT calculations. S.-L.H. and L.C. conducted the fs-TA measurements. K.-H.X. and G.-B.W. contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and commented on the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, KH., Wang, GB., Huang, F. et al. Multicomponent one-pot construction of benzo[f]quinoline-linked covalent organic frameworks for H2O2 photosynthesis. Nat Commun 16, 3493 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58839-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58839-7