Abstract

Division plane positioning in plants relies on the remarkably accurate selection of the cortical division zone (CDZ), earmarked by the preprophase band of microtubules. The PHRAGMOPLAST ORIENTING KINESIN 1 and 2 (POK1/2) play pivotal roles in CDZ maintenance in mitosis and guide the approaching phragmoplast during cytokinesis. Our knowledge regarding the mechanism of POK recruitment and subsequent maintenance is hitherto limited. Here, we report that POK2 arrives at the preprophase band utilizing a secondary microtubule-binding site within its carboxy-terminus. Effective tethering to the plasma membrane is achieved through non-specific electrostatic interactions with phospholipids. Reaching the cortex via premitotic cortical microtubules emerges as a prerequisite for POK2 polarization, as the order and the density of prophase microtubules become particularly relevant in the preprophase band-compromised mutant trm678. POK2 binding to cortical microtubules templates its future position at the cortex and appears critical for adequate division site setup and consequently tissue architecture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The evolution of plant growth was facilitated by the emergence of plant-specific cytoskeletal arrays that allow division plane positioning in three dimensions1,2,3. Division plane determination in vascular plants is the outcome of a selection process that responds to morphogenetic stimuli, including cell geometry and the mechanical properties of the cell wall, or to polarizing cues4. This leads to the polarization of the cortical division zone (CDZ), a distinct region of the plasma membrane and its adjacent cell wall, either in an equatorial position during symmetric divisions or in an off-center position during asymmetric/formative divisions5,6. Invariably, the CDZ instructs the assembly of a premitotic, dense cytoskeletal ring, the preprophase band, which is one of its first morphological indications earmarking the division site for cytokinesis6,7. The preprophase band forms during the G2 phase and disassembles upon nuclear envelope breakdown8. Following the disorganization of preprophase band microtubules, a molecular memory is maintained at the CDZ by numerous proteins that occupy the cell cortex at that region throughout mitosis and cytokinesis4.

Among these, the class I Kinesin-12 PHRAGMOPLAST ORIENTING KINESIN (POK) POK1/Kin-12C and POK2/Kin-12D are core division site proteins that emerge at the preprophase band and, upon transition to metaphase, remain continuously associated with the CDZ throughout mitosis and cytokinesis9. In addition, POK2 localizes at the midzone of the phragmoplast safeguarding its timely and steady expansion towards the cell periphery10. POKs are required for plant development and accurate cell plate positioning as simultaneous loss of function of POK1 and POK2 in Arabidopsis severely affects plant growth and morphology11. Cellular organization and architecture of individual tissues are disturbed in double mutants with oblique cell walls, indicating random cell plate insertion due to impaired phragmoplast guidance3,11. Among others, POKs exert scaffolding functions, through their C-terminal region, retaining other CDZ residents at the cell cortex. In particular, the microtubule-associated protein (MAP) TANGLED, and RanGAP1, which are independently recruited to the preprophase band in a microtubule-dependent manner, and Rho related of Plants (ROP) regulators PHGAPs, rely on POKs for their maintenance at the division site, as they are lost in POK mutants after preprophase band disassembly12,13,14.

Furthermore, TANGLED and RanGAP1 are absent from the cell cortex in root cells of fass/tonneau2 Arabidopsis mutants that are devoid of preprophase bands12,13. Along these lines, POKs fail to emerge in prophase in the absence of microtubules following oryzalin treatments that depolymerize microtubules, including those of the preprophase band3,10. Consequently, the preprophase band is a cytoskeletal array that is considered an important division site modifier4. The generation of the preprophase band requires the function of the TON1-TRM-PP2A (TTP) complex. The TONNEAU1 RECRUITING MOTIF (TRM) proteins are necessary for complex assembly and recruitment to the cytoskeleton15. It was shown that simultaneous mutation of TRM6, TRM7, and TRM8 impairs the formation of the preprophase band and in these mutants, a significant number of cells are lacking this array16.

The morphological robustness of trm678 preprophase band-compromised mutants, along with the presence of cortical POK1 rings in trm678 dividing cells, questioned the necessity of the preprophase band16,17. Evidently, despite advances, our knowledge on the mode of division plane establishment and the maintenance of proteins located at the division site is still poor. In an effort to delve into the mechanisms that orchestrate division plane positioning in plants, we use the core component of the division site, kinesin-12 POK2, that aside from its presence at the division site, prominently associates with the phragmoplast midzone10. Our work aims to unravel the mode of accurate, polar POK2 localization to the cell cortex and to understand its diverse phragmoplast guidance capabilities.

Results

POK2 C-terminus contains a secondary microtubule-binding site

We previously reported that the carboxy-terminal fragment of POK2 (Ct, 2083-2771 amino acids (aa)) is sufficient for POK2 presence at the preprophase band and the CDZ (Fig. 1a, b and Fig. 2a, b)10. To fully understand its impact on the protein localization pattern, we generated green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged POK2 ΔCt (GFP-POK2 ΔCt), lacking the Ct, and expressed it in tobacco bright yellow-2 (BY-2) cells and in Arabidopsis root meristems using p35S and native POK2 promoters (Supplementary Fig. 1). GFP-POK2 ΔCt failed to decorate the CDZ, confirming the necessity of the Ct for the spatiotemporal pattern of POK2 (Supplementary Fig. 1). To address how POK2 Ct arrives at the preprophase band in the absence of the amino-terminal motor10,18, we generated a series of truncations in POK2 Ct and assessed their ability to associate with microtubules (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 2). Indeed, fragments POK22503-2670 (POK2 #2) and POK22379-2670 (POK2 #2 + 3) showed filamentous patterns reminiscent of cortical microtubules in interphase and in prophase cells when expressed transiently in Nicotiana benthamiana or stably in Arabidopsis plants (Fig. 1c–f and Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). POK2 #2 and POK2 #2 + 3 also decorated bipolar mitotic arrays such as spindles and phragmoplasts, while POK22379-2520 (POK2 #3) remained rather cytosolic (Fig. 1f–h and Supplementary Fig. 3b), suggesting POK2 #2 was sufficient for microtubule association in vivo. Considering that this association could be indirectly mediated by an interaction partner or direct, we tested whether fragment #2 bound to tubulin. We performed an in vitro microcopy-based microtubule binding assay19 using purified glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-fused POK2 #2 (GST-POK2 #2) expressed in Escherichia coli (E. coli), and GST fused with microtubule binding domain of MAP420 (GST-MBD) as positive control (Fig. 1i). Mixing of GST-POK2 #2 with polymerized rhodamine-labeled microtubules and detection with an anti-GST Alexa 488-conjugated antibody revealed that POK2 #2 binds directly to microtubules. Microtubule binding was further examined with an in vitro microtubule spin-down assay21. Purified GST-POK2 #2 (Fig. 1i) consistently co-sedimented with microtubules in the pellet in low amounts, but repeatedly higher than the controls and GST-POK2 #8 far upstream of POK2 #2 (Fig. 1j–l and Supplementary Fig. 3c). Based on these results, we propose that POK2 Ct contains a secondary microtubule-binding site, similar to animal kinesin-12 homologs22. However, both, POK2 #2 and POK2 #2 + 3 fragments remained absent from the division site after prophase, despite enclosing the secondary microtubule-binding region necessary to bind cortical microtubules, preprophase bands, and bipolar mitotic arrays (Fig. 1f–h). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the emergence of POK2 #2 at the preprophase band alone is not sufficient for its preservation at the CDZ beyond preprophase band disassembly. Thus, CDZ maintenance might involve additional functional domains within POK2 Ct.

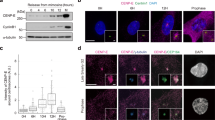

a Domain organization of full-length POK2 and relevant deletion constructs (blue bars). b Dividing cells expressing pPOK2::GFP-POK2 and the microtubule reporter pUBN::RFP-MBD. Arrows point to the division site. c Expression of p35S::GFP-POK2 #2 in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. GFP-POK2 #2 displays filamentous localization patterns (arrows) reminiscent of microtubules in interphase cells. d, e Co-expression of p35S::GFP-POK2 #2 and the microtubule reporter pUBN::RFP-MBD in Arabidopsis root interphase (d) and prophase (e) cells. Arrows point to cortical GFP signal co-localizing with microtubules. f Fragment GFP-POK2 #2 + 3 labels microtubule arrays in dividing cells. On the left, arrows show the preprophase band, the arrowhead points to a metaphase spindle. On the right, GFP-POK2 #2 + 3 decorates the phragmoplast (arrowhead). GFP signal is not associate with the cortex in metaphase (brackets). g, h Localization of GFP-POK2 #2 and GFP-POK2 #3. Unlike GFP-POK2 #2, which labels the phragmoplast in cytokinesis (g, arrowhead), GFP-POK2 #3 does not co-localize with the phragmoplast. In both cases, no signal is present at the cell cortex (brackets). i In vitro microscopy-based microtubule binding assay showing binding of POK2 to rhodamine-labeled polymerized microtubules. GST-POK2 #2 and GST-MBD (positive control) were detected using an anti-GST-Alexa 488-conjugated antibody. The assay was performed two times with similar results. j, k Coomassie-stained gels following sample ultracentrifugation. Before ultracentrifugation, samples were either mixed with polymerized and Taxol-stabilized microtubules (j) or incubated without microtubules (k). A MAP fraction (60% MAP2 at 280 kDa and 40% tau proteins at 40–70 kDa) served as positive control, while BSA (68 kDa) and GST (28 kDa) were used as negative controls. The arrows point out the respective protein bands. GST-POK2 #2 (GST-P2 #2) largely remains in the supernatant (S) after ultracentrifugation, while a small portion co-sedimented with microtubules in the pellet (P). l Quantification of the amount (%) of GST-P2 #2 in the pellet in the presence (+) and in the absence (−) of tubulin and normalized to GST-P2 #2 in (S). The assay was performed six times and the difference is significant (Two-sided Wilcoxon-signed-rank test p = 0.01355). Source data are provided as Source Data files.

a Domain organization of full-length POK2 and relevant deletion constructs (blue bars). b–d Dividing cells expressing pPOK2::GFP-POK2 Ct (b), pPOK2::GFP-POK2 Ct Δ#1 (c) and pPOK2::GFP-POK2 CtRK6A (d) along with the microtubule reporter RFP-MBD (magenta). Cells after prophase show prominent cortical division zone localization in (b), whereas the signal is broad and diffuse in (c, d). Compare signal intensities in (b) with that of the preprophase band in (d). Intensity plots depict profiles of signal intensities along the dashed lines (orange, prophase; blue, cytokinesis). Note the difference in peak heights. e Quantitative analysis of cortical GFP signal distribution in dividing root cells expressing POK2 Ct, POK2 Ct Δ#1, and POK2 Ct RK6A under the control of 35S promoter. The absence of fragment #1 or of the PBD interferes with the maintenance of the signal after prophase (POK2 Ct n = 42 cells, 18 seedlings; POK2 Ct Δ#1, n = 57 cells, 14 seedlings; POK2 Ct RK6A, 84 cells, 17 seedlings). f PIP strips incubated with purified GST-POK2 #1 (left), GST-POK2 #1RK10A (right) and with anti-GST antibody. On top, diluted anti-GST antibody (1 μl of 1:10 dilution, dots on the left) and protein solutions (dots at the center: undiluted protein after purification; dots on the right: protein at the dilution used) were dropped as detection controls. GST-POK2 #1 binds primarily to PI(3)P, PI(4)P, and PI(5)P, and phosphatidic acid (PA), whereas Alanine substitution mutant GST-POK2 #1RK10A does not bind phospholipids. The assay was performed three times with similar results. g, h Protein lipid overlay assays with polyPIPsomes (g) and PA-coated beads (h) following incubation with GST-POK2 #1 (g, h) or GST-POK2 #1RK10A (h). In (g), the protein amount eluted was higher in case liposomes contained 5% PI(3)P, PI(4)P, or PI(5)P compared to the control liposomes (-). In (h), after incubation with beads and three washing steps, the protein was detected in the eluate in the case of the WT fragment but was not visible when the RK10A mutant was used (IN, input; FT flow-through; EL, elution). The assays were performed twice with similar results. Source data are provided as Source Data files.

Maintenance at the division site requires electrostatic interactions with phospholipids

The establishment of the division site likely involves modifications at the plasma membrane23. Indeed, POK distribution at the cell cortex following prophase points to membrane-binding properties3,10. In silico analysis revealed the presence of basic hydrophobic amino acids (polybasic domains, PBD) within the last 100 aa of POK2, predicting elevated probability to associate with membranes (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 4a, b)24. PBDs mediate interactions with anionic phospholipids and often facilitate the interplay between peripheral proteins and the plasma membrane25,26. Therefore, we deleted the last 100 aa in POK2 Ct and examined the effects in vivo. Unlike POK2 Ct, which shows prominent CDZ localization, the fragment POK22083-2670, designated POK2Ct Δ#1, exhibited considerably decreased occupancy at the CDZ from metaphase onward, suggesting that the last 100 aa POK22672-2771 (POK2 #1) were important for the association of POK2 with the CDZ (Fig. 2b, c, e). To examine whether the PBD present in POK2 #1 is implicated in phospholipid binding, we mutated basic hydrophobic amino acids within the domain to alanine and expressed wild-type and mutant (POK2 #1RK10A) fragments fused to GST in E. coli. Then, we tested the purified proteins in protein-lipid overlay assays. Wild-type GST-POK2 #1 showed preferential binding to phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate (PI(3)P), PI(4)P, PI(5)P and phosphatidic acid (PA), whereas the mutant POK2 #1RK10A did not bind to any lipids on PIP strips (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 4d). Lipid binding was also confirmed using phospholipid-coated beads and polyPIPsomes, i.e., liposomes with different phospholipid compositions (Fig. 2g, h and Supplementary Fig. 4f)27. Finally, to examine whether the binding was specifically reliant on the PBD, we synthesized two biotin-conjugated peptides, one corresponding to the PBD, and one in which its basic hydrophobic amino acids were substituted to alanine26. Indeed, the wild-type peptide (net charge = 7.99) displayed phospholipid association comparable with POK2 #1, whereas the mutant peptide RK6A (net charge = 1.99) showed no binding, supporting the view that the basic amino acids at the end of POK2 C-terminus mediate POK2 tethering at the plasma membrane (Supplementary Fig. 4e). In planta, POK2 Ct with basic residue substitution fused to GFP (POK2 CtRK6A) was recruited to the preprophase band and, although the effective maintenance at the CDZ beyond prophase was compromised, association with the plasma membrane was not abolished but diffuse in more than 50% of cells (n = 84 cells; Fig. 2d, e and Supplementary Fig. 4c). Therefore, the PBD within POK2 #1 is not solely responsible for membrane association of POK2.

Thus, we sought additional domains providing membrane tethering within POK2 Ct, located upstream of fragment # 3, which remained cytosolic in planta (Fig. 1a, h and Supplementary Fig. 2). Using a series of truncations (POK22083-2379 #6, POK22267-2379 #7, POK22083-2268 #8), we further fine-mapped the suspected second lipid-binding region to POK22267-2379 (POK2 #7), upstream of the secondary microtubule-binding site (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 2). Protein lipid overlay assays (PIP strips) revealed that only fragments #6, and #7, but not fragment #8 bound phosphoinositides (Fig. 3a, d and Supplementary Fig. 5a, b). In silico analysis of POK2 #7 mapped the presence of basic and hydrophobic amino acids; however, BH-score values remained below the threshold of a typical PBD (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Next, we employed Heliquest, to predict the probabilities of amphipathic helices based on the hydrophobic moment, and discovered a region with amphipathic properties containing several arginines and lysines within POK2 #7 (Supplementary Fig. 5c). Furthermore, amphipathicity and hydropathy analysis identified the maximum amphipathicity value in that region (Supplementary Fig. 5d). Structural prediction using AlphaFold corroborated the presence of polar and hydrophobic faces within fragment #7 forming a helix (Supplementary Fig. 5e). Mutation of basic amino acids to non-polar or hydrophobic ones disturbed the polar face, reduced amphipathicity and abolished phospholipid binding (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 5d, e). Therefore, we propose fragment #7 associates with phospholipids via a putative amphipathic helix which commonly mediates membrane binding28. The existence of an additional phospholipid binding site may explain the weak maintenance of fragment #5 at the division site after prophase in planta, despite the absence of the PBD (Fig. 3a, b). It seems that both phospholipid-binding sites are required for efficient tethering of POK2 Ct to the plasma membrane post-prophase. Indeed, fusion of #5 and #1 restored localization at the division site (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 5f). In conclusion, the membrane-binding properties of fragment #7 and fragment #1 seems to promote membrane tethering. To further examine the functional relevance of the latter, we generated a protein POK2 #5 + 15RKtoLGGYV + RK6A carrying the mutations that disturbed amphipathicity and reversed the charge of the polybasic domain (Supplementary Fig. 5d, e). Live cell imaging shows that cells lose division site localization of POK2 #5 + 15RKtoLGGYV + RK6A after prophase, supporting the fundamental importance of plasma membrane tethering for maintenance upon preprophase band disassembly (Fig. 3e, f). Consistently, division site association was lost in BY-2 cells expressing full-length POK25RKtoLGGYV + RK6A after prophase (Fig. 3g).

a Domain organization of full-length POK2 and deletion constructs (blue bars). Tan and light blue bar indicate the putative amphipathic helix and the polybasic domain (PBD), respectively. b Successive images of a cell expressing p35S::GFP-POK2 #5 (green) and the microtubule marker pUBN::RFP-MBD (magenta) from pro-metaphase to cytokinesis. Cortical GFP-signal faints (arrows). c Cytokinetic cell with phragmoplast (magenta) and prominent cortical p35S::GFP-POK2 #5 + 1 (green) at the cortical division zone (arrow). Note the difference in localization in the absence of fragment #1. d PIP strips incubated with purified GST-POK2 #7, GST-POK2 #75RKtoLGGYV and anti-GST antibody. Diluted anti-GST antibody (1:10, left) and protein (right) were dropped as detection controls. Wild-type fragment #7 binds to PI(3)P, PI(4)P, and PI(5)P, while binding is abolished in GST-POK2 #75RKtoLGGYV mutant. The PIP strip assays were performed twice with similar results. e, f Images of a root cell expressing p35S::GFP-POK2 #5 + 15RKtoLGGYV + RK6A, stained with propidium iodide (e). Frequencies of dividing cells expressing this fragment (f; n = 55 cells, 11 seedlings). Signal in prophase (arrows) is lost from the cortex in cytokinesis (brackets). g Dividing BY-2 cells expressing pPOK2::GFP-POK25RKtoLGGYV + RK6A. Cortical POK2 rings in prophase are not maintained (bracket). h, i Single Z-plane images of cells expressing pPOK2::GFP-POK2 CtPBD-KRAS (green) along with pUBN::RFP-MBD (magenta, h). GFP-POK2 CtPBD-KRAS decorates the microtubule arrays (arrowheads) and localizes at the cortical division zone (arrows) comparably to wild-type Ct. (i) Comparison of division site width (yellow dashed lines) between POK2C KRAS and POK2C WT. Box plots show the median, the upper and lower quartiles, and the range of the data. The differences were not significant (One-way ANOVA: F = 1.8373, p = 0.177; Post Hoc Test: Tukey HSD; POK2C WT: n = 38 cells, 12 seedlings; POK2C KRAS: n = 42 cells, 9 seedlings). j GST-POK2 #1KRAS binds to a wide range of phospholipids in PIP strips. Dots serve as detection controls for protein (left) and anti-GST antibody (right). The PIP strip assay was performed twice with similar results. Source data are provided as Source Data files.

In our protein-lipid overlay assays, the binding of fragments POK2 #1 and POK2 #7 was limited to a subset of lipids. A reasonable hypothesis might be the existence of a specific lipid composition at the division site29. Consequently, polarized lipids could account for the accurate tethering of POK2 at the plasma membrane region corresponding to the CDZ. To test this possibility, we exchanged the PBD of POK2 Ct with that of KRAS4B, a mammalian small GTPase that binds to a broad range of phospholipids30. Swapping the PBD of GST-POK2 #1 with the KRAS PBD (GST-POK2 #1PBD-KRAS; net charge = 10.88) increased the range of lipids associating with the fragment (phosphatidylinositol phosphates, phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylserine) (Fig. 3j). This loss of binding specificity did not interfere with the distribution of GFP-POK2 CtPBD-KRAS expressed in Arabidopsis that showed localization at the CDZ, comparable to wild-type POK2 Ct (Fig. 3h, i). Similar observations were made when the PBD in GFP-POK2 Ct was replaced by that of PHGAPs (GFP-POK2 CtPBD-PHGAP; net charge = 6.99), which interact with POKs at the division site, but exhibit different phospholipid-binding preferences (Supplementary Fig. 5g)14,31. Therefore, we conclude that the interplay between POK2 and the plasma membrane might not rely on a specific phospholipid composition at the CDZ. Instead, we propose electrostatic interactions of the PBD and the amphipathic helix with anionic phospholipids, likely spread evenly across the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane, mediate POK2 division site maintenance.

POK2 binding to cortical microtubules is a prerequisite for division site maintenance

Our results established, that two membrane-binding sites flanking a cryptic microtubule-binding region in the POK2 Ct are required for the spatiotemporal localization pattern (Supplementary Fig. 2). Notably, the motor domain of POK2 does not confer preprophase band targeting10. Based on the filamentous distribution of POK2 during its recruitment and its disappearance upon oryzalin treatment during prophase10, we hypothesized that premitotic microtubules, i.e., the preprophase band, are instrumental for the initial targeting of POK2 to the cell cortex and its subsequent maintenance. To test this notion, we generated truncated POK2 proteins that excluded the microtubule binding site (#2 + 3) and the PBD (#1), retaining the amphipathic helix (POK21-2379, GFP-POK2 Δ#4, GFP-POK2 Δ#2 + 3; Fig. 4a). In line with our hypothesis, the truncated proteins showed significantly reduced preprophase band localization compared to the full-length protein, and affected POK2 division site maintenance despite the presence of one or both membrane-associated domains (Fig. 4a–e). We quantified the ratio of fluorescence intensities between the preprophase band and cytoplasm in prophase cells of GFP-POK2 and GFP-POK2 Δ#4, both expressed under POK2 native promoter (Fig. 4g) and between CDZ and phragmoplast midzone in cytokinetic cells (Fig. 4h). In both, prophase and cytokinesis, the ratio of GFP-POK2 Δ#4 fluorescence intensity was reduced compared to GFP-POK2, indicating that recruitment and maintenance of the deletion mutant was compromised (Fig. 4e–h). Furthermore, the overall frequency of cortical GFP-POK2 Δ#4 was about halved throughout cell division, with instances of incomplete rings (Fig. 4i and Supplementary Movie 1). Since GFP-POK2 Δ#4 was faintly present at the cortical division site in some cells, we asked whether this suffice to rescue the pok1pok2 double mutant phenotype. Consistent with its low abundance, we observed partial genetic complementation of the pok1pok2 mutant root length phenotype and of oblique cell division plane orientation by GFP-POK2 Δ#4 (Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Fig. 6). We envisioned that the partial complementation might be attributed to the presence of POK2 Δ#4 in the midzone, which, similar to POK2, contributes to phragmoplast steady expansion10, and may populate the cortical division site during late cytokinesis. Indeed, we did observe such instances of “late recruitment” (Fig. 5c). This way the phragmoplast may compensate for the low abundance or the lack of CDZ localization of core residents, as has been suggested earlier32. Midzone targeting, however, occurred also when excluding the entire Ct region (Supplementary Fig. 1). Therefore, we compared the degree of complementation between GFP-POK2 Δ#4 and GFP-POK2 ΔCt (Fig. 5a, d–f). In contrast to GFP-POK2 Δ#4;pok1pok2, root meristems organization, root length, and young seedlings of GFP-POK2 ΔCt;pok1pok2 expression lines were comparable with the pok1pok2 mutant (Fig. 5d–f). This difference between GFP-POK2 Δ#4 and GFP-POK2 ΔCt further emphasizes important functional aspects included, but not limited to the putative amphipathic helix that might facilitate docking of the approaching phragmoplast at the parental cortex. Nevertheless, accurate cortical POK2 placement relies on its ability to access the preprophase band microtubules and is essential for division plane orientation and growth (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 6).

a Domain organization of full-length POK2, POK2 Δ#4, POK2 ΔCt, and POK2 Δ#2 + 3, and relevant C-terminal fragments (blue bars). The putative amphipathic helix and the polybasic domain (PBD) are indicated by tan and light blue bars. b, c Dividing cells expressing pPOK2::GFP-POK2 Δ#2 + 3 and p35S::GFP-POK2 #2 + 3, stained with propidium iodide. Unlike GFP-POK2 Δ#2 + 3 (arrow and bracket in b), GFP-POK2 #2 + 3 decorates the preprophase band (arrows in c), while in cytokinetic cells, both are located at the phragmoplast. d Prophase (lower) and cytokinetic (upper) cells expressing GFP-POK2 #1 and RFP-MBD. GFP-POK2 #1 signal is cytosolic (arrowheads). e, f Prophase and cytokinetic cells expressing pUBN::RFP-MBD and pPOK2::GFP-POK2 (e) or pPOK2::GFP-POK2 Δ#4 (f). GFP-POK2 signal decorates the cortical division zone in prophase and cytokinesis (arrows in e), whereas GFP-POK2 Δ#4 does appear at the cortex (brackets in f). The arrowheads indicate the preprophase band, anaphase spindle, and phragmoplast in (e) and the preprophase band and phragmoplast in (f). Yellow dashed squares indicate representative regions of interest (ROI) used for quantification shown in (g, h). g, h GFP-signal intensity ratio between cortex and cytosol in prophase (g), and between cortex and phragmoplast midzone in cytokinesis (h) of cells expressing either pPOK2::GFP-POK2 or pPOK::GFP-POK2 Δ#4 (yellow dashed squares, (g), POK2, n = 27 data points, 15 cells; POK2 Δ#4 n = 26 data points, 15 cells). Box plots show the median, the upper and lower quartiles, and the range of the data. The difference is significant (One-way ANOVA: F = 57.1977, p = 0.0010053; Post Hoc Test: Tukey HSD). (h, POK2, n = 27 data points, 16 cells; POK2 Δ#4 n = 30 data points, 19 cells). The difference is significant (One-way ANOVA: F = 92.9539, p = 0.0010053; Post Hoc Test: Tukey HSD). i Frequency of cortical GFP-signal distribution in root cells expressing pPOK2::GFP-POK2 and pPOK2::GFP-POK2 Δ#4. Note the reduced cortical GFP-POK2 Δ#4 rings. The increase in cortical rings in cytokinetic cells originates from midzone GFP-POK2 Δ#4 reaching the cortex (POK2, n = 170 cells, 14 seedlings; POK2 Δ#4, n = 107 cells, 7 seedlings). Source data are provided as Source Data files.

a Domain organization of full-length POK2, POK2 Δ#4 and POK2 ΔCt. b Root cells in prophase (upper) and cytokinesis (lower) expressing pPOK2::GFP-POK2 Δ#4 and the microtubule reporter RFP-MBD in pok1pok2. GFP signal is cytosolic in prophase and does not co-localize with the preprophase band (bracket and arrow, respectively). In cytokinesis, it decorates exclusively the midzone of the phragmoplast (arrowheads). Note the oblique orientations of the phragmoplasts and the absence from the division site (brackets). c Successive single Z-plane images (time stamp indicates minutes) obtained from live-cell imaging of a cytokinetic cell expressing pPOK2::GFP-POK2 Δ#4 (upper panels). Propidium iodide shows cell walls (merge in lower panels). GFP-POK2 Δ#4 locates to the phragmoplast. Upon phragmoplast expansion towards the adjacent parental cortical regions, initial connections are established (arrow in 04:00), during the course of late cytokinesis, the GFP signal accumulates at the cortex (left arrow in 06:00), later the signal becomes reminiscent of the exploratory microtubules (arrows in 09:00). d–f root meristems, root length, and seedling phenotypes of pok1pok2 expressing no transgene, GFP-POK2 ΔCt, or GFP-POK2 Δ#4. d Root meristems, cell walls visualized by propidium iodide. e Quantification of root length. Box plots show the median, the upper and lower quartiles, and the range of the data. The differences in root length are significant (One-way ANOVA: F = 148.8218, Post Hoc Test: Tukey HSD; p = 0.0010053 (POK2 ΔCt pok1pok2 vs POK2 Δ#4 in pok1pok2); p = 0.0463516 (POK2 ΔCt pok1pok2 vs pok1pok2); p = 0.0010053 pok1pok2 vs POK2 Δ#4 in pok1pok2), pok1pok2, n = 58 roots; POK2 ΔCt, n = 42 roots; n = 52 (3 biological replicates). f Seedling phenotypes (6 days after germination, upper panel) and young plants (lower panel). Source data are provided as Source Data files.

POK2 rings in preprophase band-compromised mutants rely on an anisotropically organized microtubule array

The requirement of POK2 binding to premitotic microtubules for efficient CDZ maintenance prompted us to examine its localization in the preprophase band-compromised mutant trm67816. The mutant exhibits a relatively mild phenotype (Supplementary Fig. 7a) despite the majority of cells are devoid of a preprophase band, and a considerable number of cells display atypical preprophase bands16. Surprisingly, regardless of the preprophase band aberrations in this mutant, previous studies reported the existence of a CDZ, because of the presence of cortical YFP-POK1 rings in cytokinesis16. We investigated GFP-POK2 distribution in trm678 dividing cells of the root meristem by live cell imaging and whole-mount immunolocalization of GFP and tubulin. First, we determined the frequency of cell cycle phases considering chromatin condensation and microtubule organization (Supplementary Fig. 7b). Seedlings expressing GFP-POK2 in trm678 showed a higher frequency of cells in prophase, compared to wild-type (Supplementary Fig. 7b). This result implied that prophase might be delayed in trm678 mutants, matching the premitotic/mitotic gene expression peak of TRM716.

We recorded native, mitosis-specific GFP-POK2 localization patterns at the cortex of wild-type and trm678 cells and found filamentous cortical arrangements which were sensitive to oryzalin (Fig. 6a–c)10, and thus, decided to investigate further the interplay of POK2 with microtubules. Consistent with published data, there were no differences in the anisotropy of interphase cortical microtubules between wild-type and trm678 expressing GFP-POK2, which is under cell cycle control and therefore absent from interphase cells (Supplementary Fig. 7c, d)16,33. However, in contrast to wild-type cells, in live cell imaging, we observed GFP-POK2 recruitment to the cell cortex in random patterns in trm678 prophase cells, occasionally followed by a reorganization into cortical rings of filamentous POK2 co-localizing with a subpopulation of cortical microtubules (Fig. 6d, e and Supplementary Movie 2). The anisotropy of microtubules in prophase was higher in wild-type compared to trm678 mutant cells (Fig. 6e, f). Moreover, in both conditions, filamentous GFP-POK2 showed anisotropy values similar to the microtubules, and co-localization analysis (Manders’ coefficients) confirmed the positive correlation of POK2 and premitotic cortical microtubules (Fig. 6e–g). Quantification of cortical GFP-POK2 in trm678 showed patterns varying from aberrant POK2 rings reminiscent of preprophase bands to filamentous POK2 accumulations with random or ordered orientations that did not form continuous rings, and a small number of cells exhibiting no filamentous signal (Fig. 7a–c). Collectively, our results support the view that POK2 binds to cortical microtubules in prophase (Fig. 6 and Fig. 7).

a Median view of a trm678 cell expressing pPOK2::GFP-POK2 and pPOK2::RFP-MBD. GFP signal in prophase (arrows) co-localizes with microtubules (arrowheads). b Trm678 prophase cell (dashed lines) expressing pPOK2::GFP-POK2 and the histone marker pPOK2::RFP-H2B. The cortical signal assumes various filamentous orientations (arrow). c Cortical views of trm678 prophase cells (outlined by dashed lines) expressing pPOK2::GFP-POK2 and pPOK2:: RFP-H2B, before and 8 min after treatment with 10 μΜ oryzalin. The filamentous POK2 localization is sensitive to the microtubule depolymerizing drug. d Images of a prophase cell at consecutive time points. GFP-POK2 undergoes slow reorganization leading to the formation of an aberrant cortical ring (arrows). e Cortical views of wild-type and trm678 prophase cells expressing pPOK2::GFP-POK2, following immunolabeling of GFP and tubulin and chromatin staining with DAPI. GFP-POK2 signal decorates cortical microtubules in prophase (arrows). Arrowheads point to the preprophase band in wild-type. f Anisotropy of filamentous POK2 (blue circles and green triangles) and microtubules (orange circles and magenta triangles) in prophase. Wild-type and trm678 roots expressing pPOK2::GFP-POK2 were immunolabeled (anti-GFP and anti-α-tubulin). The graph displays the mean values, and error bars represent the standard deviation. Anisotropy of microtubules and POK2 filaments differ between wild-type and trm678 (MTs: p = 0.00000029; POK2: p = 0.0203; Two-way Anova; Tukey’s multiple comparison test). Differences between microtubules and POK2 filaments are not significant (Tukey’s multiple comparison test WT p = 0.0994; trm678 p = 0.9566; WT, n = 38 cells; trm678, n = 57 cells (4 biological replicates); F-test (Two-sided) for equality of variances: POK2 and MTs in WT: p = 0.274; POK2 and MTs in trm678: p = 0.295). g Manders’ coefficient co-localization analysis of GFP-POK2 signal and microtubules suggesting positive correlation in wild-type and trm678 prophase cells (WT n = 45 cells; trm678 n = 44 cells, 4 biological replicates). The graph displays the mean values, and error bars show the standard deviation. GFP-POK2 co-localizes with the subpopulation of microtubules in WT, and in trm678 cells microtubule association is reduced (One-way Anova F = 14.4172; Post Hoc Test: Tukey HSD, Differences between coefficient values are not significant in WT (p = 0.899) and are significant in trm678 cells (p = 0.0010053). Source data are provided as Source Data files.

a Domain organization of full-length POK2 and POK2 Δ#4, lacking the C-terminal fragment #4. b–d Quantification of cells expressing pPOK2::GFP-POK2 (c) and pPOK2::GFP-POK2 Δ#4 (d) in trm678 following immunolabeling of GFP and tubulin (b). In prophase cells, the cortical GFP-POK2 signal is heterogenous, ranging from well-defined preprophase bands, (i) atypical enrichments reminiscent of a band co-existing with cortical microtubules, (ii) and cortical array with random (iii) or parallel (iv) orientation, to distributions exhibiting no filamentous signal (v). After prophase, a considerable number of cells do not display cortical rings but show random accumulations. In the case of pPOK2::GFP-POK2 Δ#4, the signal is occasionally at the cell cortex in prophase and completely absent later on (compare with c). For quantification of cortical signal in cytokinesis, only early cytokinetic cells with midzone populations that had not reached the parental wall were included in the counting (GFP-POK2: n = 141 (172 cells total); 10 seedlings; GFP-POK2 Δ#4: n = 76 (94 cells total), 9 seedlings. Source data are provided as Source Data files. e Time-lapse images of GFP-POK2 in trm678 root cells from prophase to cytokinesis. Note the absence of cortical GFP signal until late cytokinesis, where midzone POK2 populates the cell cortex (yellow dashed square). The white arrowheads point to the midzone, and the brackets depict the lateral walls, while the yellow arrowheads depict the late recruitment to the cortex. f, g Time-lapse images of a cell expressing pPOK2::GFP-POK2 Δ#4 (green) and pPOK2::RFP-H2B (magenta). At time point 00:00 min, the cell (outlined with dashed lines) is in prophase, based on the organization of chromatin. Neither cortical nor median views show a GFP signal at the cortex. In metaphase (10:00 min) and cytokinesis (16:00 min), cortical signal is still absent (brackets), although midzone targeting is visible. g Fluorescence intensity profile along the dashed orange line drawn in the cytokinetic cell of the panel (f).

Next, we asked how the diverse POK2 recruitment patterns in trm678 mutants affected its cortical distribution later in cell division. Unlike the wild-type, in metaphase and cytokinesis, a subset of cells possessed atypical rings with uneven width, while the majority displayed no ring distribution at all (Fig. 7b, c and Supplementary Fig. 8a–e). This indicates that during prophase, the preprophase band-driven placement determines the position of the plasma membrane-tethered POK2 populations at the cortex later. To examine this hypothesis, we followed cells from prophase to cytokinesis. Live cell imaging revealed that the GFP-POK2 prophase patterns remained until the end of cytokinesis, and in cells that showed “late recruitment”, it was the POK2 population residing at the phragmoplast that finally attached to the cell cortex (Fig. 7e). To validate further the dependency of POK2 localization on cortical microtubules and its impact on division site maintenance, we used the truncated fragment of POK2 Δ#4 lacking the second microtubule-binding domain and PBD (Figs. 4 and 7a). In the trm678 mutants, the GFP-POK2 Δ#4 signal was mainly cytosolic and rarely appeared filamentous, resulting in a complete loss of rings in metaphase and cytokinesis (Fig. 7b, d, f and Supplementary Fig. 8f). The latter underscores the importance of POK2 Ct ability to bind microtubules to reach and subsequently tether to the cortex.

Division site setup and functions in preprophase band-less mutants

Division site proteins arrive independently at the cortex utilizing the preprophase band microtubules, but they interact with each other to form a fully functional CDZ4,34. The defects in the reorganization of mitotic cortical microtubules in trm678 cells suggested that the necessary modifications of the division site are not implemented. Consequently, in trm678 cells, the compromised preprophase band formation affects POK cortical localization (Fig. 7)16 and POKs might not be the only division site residents misplaced in this mutant35. On the other hand, the average orientation of cell walls is merely unaffected, and the trm678 mutant plants have a remarkably robust phenotype in comparison to pok1pok2 mutants (Fig. 8a, c and Supplementary Fig. 7a). It is tempting to speculate that differences between these mutants in cell wall orientations and growth is due to the presence of the aberrant preprophase bands and due to endogenous POK1 and POK2 in trm678, that retain the ability of being recruited to the cortex, where they still scaffold interacting CDZ components.

a Trm678 root meristems and meristems expressing pPOK2::GFP-POK2 Δ#4 in trm678 and in trm678,pok1pok2 mutant background. The cell walls are stained with propidium iodide. b Single Z-plane images of root meristem cells of quintuple mutant trm678,pok1pok2 expressing pPOK2::GFP-POK2 Δ#4. GFP signal faintly decorates the metaphase spindle (arrow) but is prominently recruited to the phragmoplast midzone (arrowheads). No cortical association of the truncated fragment is detected (brackets). Cell walls are stained with propidium iodide. Note the oblique GFP and cell wall orientation. c Quantification of cell wall orientations in root meristems. Median values and upper and lower quartiles are depicted. Note that differences are not significant between pok1pok2 and GFP-POK2 Δ#4;trm678,pok1pok2 quintuple mutant (p = 0.0749). Differences between trm678 and GFP-POK2 Δ#4;pok1pok2 and between pok1pok2 and GFP-POK2 Δ#4 are not significant (p = 0.8019 and p = 0.07498, respectively; One-way Anova, F = 69.4972; Post Hoc test: Tukey HSD; pok1pok2 n = 268 cells in 2 roots; trm678 n = 331 cells in 2 roots; GFP-POK2 Δ#4;pok1pok2 n = 240 cells; GFP-POK2 Δ#4;trm678 n = 401 cells in 3 roots; GFP-POK2 Δ#4;trm678,pok1pok2 n = 538 cells in 5 roots). Source data are provided as Source Data files. d Plants expressing pPOK2::GFP-POK2 Δ#4 in trm678 and in trm678,pok1pok2 mutant background. A pok1pok2 mutant of the same age is shown on the right, next to these plants, for a direct comparison of development between the different genotypes.

To test the latter possibility, we decided to eliminate endogenous POKs, in trm678 plants expressing POK2 Δ#4. In trm678,pok1pok2 quintuple mutant plants, POK2 Δ#4 is unable to access the cortex until late cytokinesis due to the lack of the secondary microtubule-binding site (Fig. 7b, d, f and Supplementary Movie 3). trm678 plants with and without POK2 Δ#4 expression have a relatively mild phenotype (Fig. 8a, c). However, in the absence of endogenous POKs, growth was significantly affected, and POK2 Δ#4 expression was not sufficient to restore the oblique cell wall phenotype (Fig. 8). Although phragmoplast midzone localized POK2 Δ#4 (Fig. 8a, b) contributes to cell plate positioning somehow, it cannot compensate for the superior functions of the POK population at the cortex i.e., phragmoplast guidance and protein scaffolding (Fig. 8).

Discussion

Based on our functional domain analysis, we propose that cortical targeting of the core division site resident POK2 relies on its secondary microtubule-binding site, while the subsequent membrane tethering, upheld by two membrane-binding sites, enables POK2 to exert its guidance function. As yet, the existence of unknown interaction partners that contribute to POK2 polar placement cannot be excluded. Domain swapping of POK2 PBD revealed that the plant CDZ likely does not comprise a polarized lipid composition, unlike, for instance, the sterol-rich membrane domains governing premitotic cell polarization in yeast36. On the contrary, accurate cortical POK2 positioning relies on its ability to bind prophase cortical microtubules, which serve as templates for subsequent membrane tethering.

Besides, complementation experiments with POK2 deletion mutants revealed that phragmoplast stability might contribute to division plane orientation to some extent, allowing the cell plate to reach the cortex at the preselected site, irrespective of the presence of membrane-tethered, phragmoplast awaiting POK2 populations. Scenarios in which geometrical- or polarity-based positioning of the premitotic nucleus are determining factors of the future division plane37,38, potentially explain the astonishingly mild oblique cell wall phenotype under limited guidance from the CDZ. Since there is no cytoplasmic streaming disturbing the expansion of the cytokinetic apparatus39,40, a phragmoplast of a root meristematic cell that initiates between the daughter nuclei and expands steadily may reach the cortex within the preselected CDZ. It is noteworthy that similar to TAN-deletion mutants in air9 tan background41, we observed several cells with “late recruited” cortical POK2 Δ#4, consistent with the notion that phragmoplast midzone-derived POK2 accesses the cortex in late cytokinesis and form late rings (Fig. 5c).

The developing cell plate meets the parental cell wall at the division site, as long as the phragmoplast reaches the CDZ at a critical distance, otherwise the cell plate fusion might occur elsewhere leading to atypical cell shapes, as has been shown in grasses42. In any case, docking of the approaching phragmoplast to the cortex could involve midzone-localized POK2 tethering to the plasma membrane via binding to phospholipids. Besides, microtubule binding of POK2 Ct might allow the POK2 population on the phragmoplast peripheral exploratory microtubules to interact with the telophase cortical microtubules recently discovered in maize (Fig. 5c)18,43,44. Such interplay may explain the “late recruitment” of POKs, in mutants with compromised division site or preprophase band34,45. Myosin VIII ATM1 is a potential candidate for POK2 interaction during late phragmoplast expansion. Interestingly, ATM1 has been implicated in collision events of microtubules with membrane-associated structures, while in Physcomitrium, myosin VIII binds to plus ends of phragmoplast microtubules, promoting lateral expansion towards the cortex44,46. Along the same lines, during late cytokinesis, maize TAN is recruited to aberrant cell plate fusion sites in a myosin XI-dependent manner47. Consistent with physical connections between the cytokinetic apparatus and the CDZ44, GFP-POK2 decorated a thin bridge between the phragmoplast and the cortex (Fig. 7e, 50 min).

Myosin XI isoforms also influence division plane orientation, and recently, MYA1/Myo11F has been shown to genetically interact with POKs35,48. An interaction of MYA1 with POK2 might take place either at the phragmoplast midzone or at the CDZ before cytokinesis. It was proposed that the latter facilitates the formation of Cytoskeleton-Associated Motor assemblies at the Preprophase band site (CAMPs), and consistently MYA1 localization is affected in trm678 cells35. In the same direction, the compromised formation of preprophase bands in the trm678 and the iqd678 mutants interfered with the abundance of POK1 cortical rings16,49 and POK2 cortical rings (this study). Our results suggest that the random recruitment of TTP complexes required for MT rearrangements to the cortex in trm678 mutants is responsible for the very slow reorganization and the disordered cortical microtubule patterns, which in turn affect POK2 recruitment. Like in wild-type, in trm678, prophasic cortical microtubules prescribe the imminent POK2 localization at the plasma membrane, and thus, the presence of POK2 rings relies on the order and density of cortical microtubules. Taken together, these results support the requirement of preprophase band microtubules for the timely arrival of core components of the division site.

By definition, the CDZ is a region that possesses a dynamic but distinct composition8. Considering the number of proteins including MYA1, that owe their maintenance at the cortex to POKs’ scaffolding function after prophase and the randomness of POK positions in trm678, our results challenge the proposed presence of a canonical CDZ in these mutants and corroborate the existence of alternative mechanisms that confer robustness4,12,13,16,35,50. We tested the guidance capacities of the midzone population under the complete loss of steering by the cortex POK population. In particular, prompted by the partial rescue of pok1pok2 by GFP-POK2 Δ#4, we expressed this fragment in trm678 mutants in the absence of endogenous POKs. The prominent POK2 midzone association, however, did not restore the oblique cell wall phenotype in roots pointing to the significance of a proper CDZ setup and maintenance.

Our findings, summarized in a hypothetical model (Supplementary Fig. 9), further support the importance of the preprophase band assembly for a fully functional division site. It seems that the preprophase band serves as the readout of mechanical, geometric, or polarizing cues and operates as a recruiting template for the correct positioning of core division site components, i.e., POKs that subsequently tether to the adjacent plasma membrane via electrostatic interactions. Excluding POKs from the cortex impairs phragmoplast guidance and disempowers the CDZ, by depriving it of POK-depended residents. Collectively, our work unravels the mechanism of POK2 recruitment and its multidimensional functions during cell division that contribute to proper cell plate positioning.

Methods

Plant Material

In the present study, wild-type, mutant, and transgenic plants of the Arabidopsis thaliana accession Columbia (Col-0) were utilized. Mutants pok1pok2 (allele combination pok1-1pok2-3) and trm678 were described previously3,16.

Growth conditions

Arabidopsis seeds were sterilized with 6% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite (Roth, 9062) and sown on plates containing ½ × Murashige and Skoog medium with vitamins (Duchefa-Biochemie, M0222) plus 0.1% MES in 1% (w/v) phyto-agar (Duchefa, P1003). Seeds were stratified for at least 24 h at 4 °C in darkness, and afterward, seedlings were grown at standard conditions (22 °C, 16 h light/8 h darkness cycle). For crossing or reproduction, 2-week-old seedlings were transferred to soil and grown in a plant growth chamber under the conditions described above.

Generation of constructs

Entry vectors

PCR fragments were amplified by Phusion HF polymerase for cloning purposes (New England Biolabs, M0530).

POK2 1-27715RKtoLGGYV + RK6A: PCR fragment amplified from pENTR3CPOK22267-27715RKtoLGGYV + RK6A using BamHI_POK2_ATG-2083a and POK2 2379 Stop_SalI _R and cloned into pENTR3C POK210 digested with BstZ17I and XhoI resulting in pENTR3C POK2 Δ#45RKtoLGGYV. Plasmid was created via ligation after digest of the latter and of the pENTR3C POK22267-27715RKtoLGGYV + RK6A with AsiSI and SphI.

POK21-2379 (POK2 Δ#4): Generated by ligation, following digest of pENTR3C POK210 and pENTR3C POK22083-2379 with SphI/PvuI.

POK21-2084 (POK2 Δ#Ct): PCR fragment was amplified using POK2 4050_F and POK2 2084 Stop_XhoI_R (Supplementary Table 1) and pENTR3C POK2 as template. Amplicon and pENTR3C POK2 restriction were digested with PshAI and XhoI and ligated.

POK2Δ2379-2697 (Δ#2 + 3): POK2 Ct2083-2379 linker2697-2771 amplified via overlap PCR using appropriate primers (Supplementary Table1), digested with BamHI and SalI and introduced into the pENTR3C digested with BamHI and XhoI. The latter plasmid was digested with SphI and PvuI and cloned using pENTR3C POK2 as the vector backbone.

POK22379-2670 (fragment #2 + 3): Amplicon generated via PCR using pENTR3C POK22083-277110 as a template and specific primer combinations introducing BamHI/SalI sites (Supplementary Table 1). Afterward, the insert was cloned into pENTR3C via restriction digest (BamHI/XhoI) and ligation.

POK22379-2520 (fragment #3): Amplicon generated via PCR using pENTR3C POK22083-2771 as a template and specific primer combinations introducing BamHI/XbaI sites (Supplementary Table 1). Afterward, it was cloned into pENTR3C via restriction digest and ligation.

POK22503-2670 (fragment #2) Amplicon generated via PCR using pENTR3C POK22083-2771 as template and specific primer combinations introducing BamHI/SalI sites (Supplementary Table 1) and, it was cloned into pENTR3C via restriction digest (BamHI/XhoI) and ligation.

POK22672-2771 (fragment #1): Amplicon generated via PCR using pENTR3C POK22083-2771 as a template and specific primer combinations introducing BamHI/SalI sites (Supplementary Table 1). Afterward, it was cloned into pENTR3C via restriction digest (BamHI/XhoI) and ligation.

POK22083-2670 (fragment Ct #Δ1): Amplicon generated via PCR using pENTR3C POK22083-2771 as template and specific primer combinations introducing BamHI/SalI sites (Supplementary Table 1) and, was cloned into pENTR3C via restriction digest (BamHI/XhoI) and ligation.

POK22083-2379 (fragment #6): Amplicon generated via PCR using pENTR3C POK22083-2771 as a template and specific primer combinations introducing BamHI/SalI sites (Supplementary Table 1). Afterward, it was cloned into pENTR3C via restriction digest (BamHI/XhoI) and ligation.

POK22083-2268 (fragment #8): Amplicon generated via PCR using pENTR3C POK22083-2670 as a template and specific primer combinations introducing BamHI/XhoI sites (Supplementary Table 1), and was cloned into pENTR3C via restriction digest and ligation.

POK22267-2379 (fragment #7): Amplicon generated via PCR using pENTR3C POK22083-2670 as a template and specific primer combinations introducing BamHI/SalI sites (Supplementary Table 1). Afterwards, it was cloned into pENTR3C via restriction digest (BamHI/XhoI) and ligation.

POK22267-23795RKtoLGGYV: Fragment generated via PCR and site-directed mutagenesis using mismatch primers (Supplementary Table 1) and POK2 #7 as template in two cloning steps.

POK22267-2670 (fragment #5): Amplicon generated via PCR using pENTR3C POK22083-2670 as a template and specific primer combinations introducing BamHI/SalI sites (Supplementary Table 1). Afterward, it was cloned into pENTR3C via restriction digest (BamHI/XhoI) and ligation.

POK22267-2771 (fragment #5 + 1): Using pENTR3C POK22083-2379 as a template with specific primers, a fragment including 2267-2379 was amplified and cloned into pENTR3C POK22083-2771 via restriction digest with BamHI and SphI and ligation.

POK22672-2771RK10A: Amplified from pUC57 POK2C RK10A using specific primer combinations. The PCR fragment was introduced into pENTR3C via BamHI/XhoI restriction digest and ligation. POK2C RK10A sequence with flanking XhoI sites and PstI sites was synthesized and introduced into pUC57 by General Biosystems, USA.

POK22083-2771RK6A: pUC57 POK2C RK6A with flanking XhoI/PstI sites synthesized by General Biosystems and digested. Afterward, it was introduced into pENTR3C POK2 POK22083-2771 via restriction digest and ligation.

POK22267-27715RKtoLGGYV + RK6A: Created by ligation following digest of POK22267-23795RKtoLGGYV and POK22083-2771RK6A with SphI and PvuI.

POK22672-2771PBD-KRAS: Amplicon was generated using pUC57 POK2C KRAS4B PBD synthesized sequence, with flanking SapI/PstI sites (General Biosystems) as a template and specific primers (Supplementary Table 1). Following restriction digest and ligation, the fragment was introduced into pENTR3C.

POK22083-2771PBD-KRAS: pUC57 POK2C KRAS4B PBD and pENTR3C POK22083-2771 were digested with SapI/PstI and ligated resulting in the pENTR3C POK22083-2771PBD-KRAS.

pENTR3C POK22083-2771PBD-PHGAP: pUC57 POK2C PHGAP-PBD (synthesized by General Biosystems) and pENTR3C POK22083-2771 were digested with SapI/PstI and afterward ligated to generate pENTR3C POK22083-2771PBD-PHGAP.

H2B: Amplified using Arabidopsis wild-type cDNA from flower buds and the H2B (AT5G22880) specific primers listed in (Supplementary Table 1). The resulting PCR fragment was cloned into pENTR3C via restriction digest (BamHI/EcoRI) and ligation.

Destination vectors

pPOK2 promoter sequence (2162 bp long) flanked by SacI/SpeI sites was amplified from pGEM proPOK211 containing approximate 2570 bp upstream of POK2 start codon and cloned into pUBN:GFP and pUBN:RFP destination vectors to replace UBQ10 promoter (pB7WRG2 vector backbone)51,52.

Expression clones

For generation of XFP and GST fusions, Gateway LR reactions using LR Clonase II mix (Invitrogen 11791) were performed as follows:

pPOK2::GFP-POK2: LR reaction using pENTR3C POK210 and pPOK2 GFP destination vector.

pPOK2::GFP-POK21-27715RKtoLGGYV + RK6A; pPOK2::POK2Δ2379-2697 (Δ#2 + 3); pPOK2::GFP-POK2 Δ#4; pPOK2::GFP-POK2 ΔCt; pPOK2::GFP-POK2Ct; pPOK2::GFP-POK2Ct RK6A; pPOK2::GFP-POK2 Ct Δ#1: LR reactions using pPOK2::GFP destination vector and the respective entry clones.

p35S::GFP-POK2Ct; p35S::GFP-POK2Ct RK6A; p35S::GFP-POK2 Ct Δ#1; p35S::GFP-POK2 #1: LR reactions using pFK241 pGreenIIS p35S::GFP destination vector10.

p35S::GFP-POK2 #2; p35S::GFP-POK2 #2 + 3; p35S::GFP-POK2 #4; p35S::GFP-POK2 #5; p35S::GFP-POK2 #5 + 1; p35S::GFP-POK2 #5+15RKtoLGGYV + RK6A; p35S::GFP-POK2 CtPBD-KRAS p35S::GFP-POK2 CtPBD-PHGAP: LR reactions using pK7WGF2 p35S::GFP destination vector51 and the respective pENTR plasmids.

pDEST15 T7::GST-POK2 #2; pDEST15 T7::GST-POK2 #1; pDEST15 T7::GST-POK2 #1RK10A; pDEST15 T7::GST-POK2 #1PBD-KRAS, pDEST15 T7::POK2 #6; pDEST15 T7::POK2 #7; pDEST15 T7::POK2 #75RKtoLGGYV, pDEST15 T7::POK2 #8: LR reactions with the respective pENTR plasmids and pDEST15 T7::GST destination vector (Invitrogen).

Τ7::GST-MBD: LR reaction with pDONR 207 MBD3 and pDEST15 T7::GST destination vector.

pDEST15 T7::GST: The destination vector was digested with BamHI in order to remove the ccdB box and religated.

pPOK2::RFP-H2B; pPOK2::RFP-MBD: LR reactions using pENTR3C H2B and pDONR 207 MBD and pB7RWG2 destination vector driving expression under pPOK2. Ligations and LR reactions were transformed into E. coli strain TOP10 (Invitrogen, C404003) or 2T1R (Invitrogen, A10460) in case where ccdB survival bacteria were necessary. Constructs were sequencing-verified prior to further use (Eurofins Genomics).

Plant transformation

Transgene integration into the plant genome was accomplished by the Agrobacterium tumefaciens transformation53, using the GV3101 or the AGL-1 strain. Screening for resistant transformants was performed on an appropriate selective medium.

Genotyping – rescue

Primers used for genotyping of the pok1pok2 double mutant10 and the trm6, trm7, and trm8 mutations16 are listed in (Supplementary Table 1).

Transformation of BY-2 cells (Nicotiana tabacum)

The BY-2 wild-type cells were transformed with Agrobacterium carrying the appropriate constructs. An overnight bacterial culture was re-diluted and grown to an OD600 0.8. The BY-2 cells (fresh 3-days-old culture) were sedimented by gravity, were washed twice with liquid Paul’s medium, mixed with the bacterial cells, and plated on solid Paul’s medium containing phytagel (Sigma, P8169)54. Following incubation at 25 °C in darkness for 72 h, cells were transferred on microscopy slides for imaging.

Nicotiana benthamiana leaf transformation

Transformed agrobacteria were grown overnight, and the cultures were rediluted (approximately to an OD600 of 0.2). At an OD600 1.0, the bacteria were harvested and resuspended in water and spun for 10 min at 3500 × g. The washing step was repeated three times, and the pellet was resolved in N. benthamiana infiltration medium (MgCl2 10 mM, MES 1 mM, Acetosyringone 100 μM, Roth, 6003). Finally, 3-week-old tobacco leaves were infiltrated on the abaxial leaf surface, and, after 48 h, the expression and localization patterns were analyzed.

Protein expression and purification

Plasmids containing GST or GST-POK2 sequence fusions downstream of the T7 promoter were transformed in SoluBL21 electrocompetent cells (Genlantis, C700210) and initially grown in selective LB medium before culturing in M9 minimal medium at 28 oC. Following induction with 1 mM IPTG (Duchefa, I1401), cultures were transferred to 18 oC for 16 h and harvested. Bacteria were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES pH7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 10 %(v/v) glycerol, 0.5 mM TCEP) and lysed via sonication and, following incubation with 0.2 mg/ml lysozyme and 1% (v/v) Triton X-100 for 1 h, the soluble proteins were isolated by centrifugation at 4 oC.

For the purification of the heterologous GST-tagged proteins from protein extracts, Glutathione Sepharose 4B beads were used (Cytiva, 170075601). The purification was carried out at room temperature, and, for sedimentation, samples were centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min. Sepharose beads (250 μl) in 20% ethanol were sedimented, washed twice in binding buffer (PBS, 140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.3), and sedimented again before use. The crude protein extracts and sepharose beads were incubated for 40 min at slow rotation (9 rpm). Samples were sedimented again, and the flow-through fractions in all further steps, were decanted. Samples were washed four times in a 1.6 ml binding buffer. The bound protein was then eluted from the sepharose matrix with 200 μl Elution Buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) containing 10 mM glutathione (Sigma, G4251) followed by 30 min incubation and sedimentation. Elutions were repeated three to four times. For each protein, eluates were mixed with sample buffer, and protein expression was checked on polyacrylamide gel stained with Coomassie, or with western blot immunodetection. The approximate protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay (Bradford reagent Sigma, B6916). Throughout the protein extraction and purification steps, all buffers contained 1x SIGMAFAST Protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, S8830).

Microtubule co-sedimentation assay

For the co-sedimentation assay, the Microtubule-Binding Protein Spin-down Assay Kit (Cytoskeleton, BK029) was used according to the manufacturer´s instructions. Proteins were eluted with General Tubulin Buffer (80 mM PIPES, 0.5 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl, pH 7.5; Cytoskeleton, BK029) plus 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100. The tubulin and the purified proteins were centrifuged at 4 °C with 100000 × g for 30 min to sediment unwanted aggregates and denatured protein. Before use, the tubulin (5 mg/ml) was thawed in the water bath at room temperature and was immediately transferred on ice. For the microtubule polymerization, tubulin was incubated at 37 °C for 15 min after adding 2 μl Cushion buffer (60% glycerol in General Tubulin Buffer pH 7.0). Then the Taxol was added stepwise as follows: 2 μl of 5 μM, 50 μM, and 500 μM. Between Taxol additions, the tubulin was incubated for 5 min and, for 15 min at 37 °C after the last addition. The polymerized microtubules were centrifuged for 10 min at room temperature with 21000 × g and resuspended in 200 μl General Tubulin Buffer containing 20 μM Taxol. Stable microtubules (approximately 0.4 nM) were used to prepare reactions of 50 μl volume. 16 μg MAP Fraction (60% MAP2, 40% tau proteins) were used as a positive control, and 7.5 μg BSA as a negative control. For each protein tested, 8-30 μg were used per reaction, and samples were prepared with and without microtubules. The reactions were incubated at room temperature for 30 min and layered on a Cushion Buffer containing 20 μM Taxol. The co-sedimentation was carried out at 100000 × g for 40 min. The uppermost 50 μl of the supernatant were taken off the sample, and 10 μl 5x Laemmli sample buffer were added to the supernatant. The rest of the Cushion Buffer was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 50 μl 1x Laemmli sample buffer. The pellet and the supernatant samples were loaded onto a 12% SDS-PAGE for analysis and quantification.

In vitro microscopy-based microtubule binding assay

For the visualization of microtubule binding of POK2 fragments in vitro, the protocol by Zhu et al.19 with some modifications was followed. In brief, for polymerization of microtubules, tubulin was mixed with rhodamine-labeled tubulin (Cytoskeleton, TL590M) and GTP (Cytoskeleton, BST06) and incubated at 37 °C for 20 min. After polymerization, microtubules were diluted in PEM containing 10 μΜ Taxol (Cytoskeleton, TXD01). For the microtubule binding assay, reactions were setup as follows: 20 μl of microtubules (20 μM tubulin) incubated with 10 μl of PEM (control), eluted GST-POK2 #2 (5 μΜ) or GST-MBD (0.6 μΜ, positive control) at 25 °C for 15 min. An anti-GST Alexa 488 conjugate (1:500; Invitrogen, A11131, Lot: 2491356) was added to the reaction for an additional 15 min. Microtubules were pelleted via centrifugation for 5 min at 17000 × g and resuspended in 50 μl of PEM containing Taxol and loaded on narrow wells formed on slides with double-sided tape and 22 × 22 mm coverslips and examined at the confocal microscope.

In silico predictions

Membrane binding

Membrane-binding sites were predicted with the BH-search tool (https://helixweb.nih.gov/bhsearch/)24 using a 19 aa window size. Screening of α-helix properties was done using the HELIQUEST web server with 20 aa sliding window (https://heliquest.ipmc.cnrs.fr/)55. Hydropathy and Amphipathicity scores were obtained using the TCDB database (https://www.tcdb.org/progs/?tool=hydro)56. For the computation of the theoretical molecular weights of different POK2 fragments, the Expasy Compute pI/Mw tool (https://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/) was used57.

Protein structure

Molecular structure prediction of wild-type and mutant fragment #7 was performed using AlphaFold 358,59 (https://alphafoldserver.com/) and visualized with UCSF ChimeraX (https://www.rbvi.ucsf.edu/chimerax/)60.

Protein-lipid overlay assays

PIP strips

GST fusion proteins were tested for binding selectivity to different lipids using PIP strips (Echelon, P-6001). First, 1 μl of undiluted protein, 1 μl of diluted antibody solution, and 1 μl of the protein at the concentration used for incubation, were dotted onto the PIP strip as controls. The PIP strip was incubated with blocking solution i.e., PBS containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20 (PBS-T), 3% (w/v) BSA 2% (v/v) milk. Next, the PIP strip was incubated with protein solution in PBS-T plus 3% BSA and 2% milk for 1 h. For immunodetection, the protein solution was decanted and after washing, an anti-GST antibody peroxidase conjugate (Sigma, A7340, Lot: 000110495) diluted 1:1000 in PBS-T plus 3% BSA and 2% milk was added for 1 h. Finally, the solution was discarded, and following washing, the PIP strip was incubated with 1.5 ml TMB precipitated substrate (Echelon, K-TMB) for detection of phospholipid binding. All incubation steps were carried out at RT with gentle agitation.

Lipid coated beads

GST fusion proteins were tested for phospholipid binding ability in pull-down assays using PI4P- and PA-coated agarose beads (Echelon, P-B004α P-B0PA). In brief, purified protein and the beads were mixed with binding buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl) supplemented with 0.5% (v/v) NP-40 (G Biosciences, 786–511) and incubated at 4 oC on an end-over-end rotator for 2 h. Following incubation, the flow-through was collected and beads were washed five times with binding buffer plus 0.75% (v/v) IGEPAL CA-630. Precipitation of beads was carried out by centrifugation at 800 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. Elution of bound proteins was performed by adding Laemmli sample buffer to the beads and heating to 95 °C for 10 min. Protein samples were separated on SDS-PAGE and detected via western blot immunodetection.

Liposomes

Phospholipid binding ability was also tested using polymerized liposomes composed of specific phosphoinositides (PolyPIPsomes, Echelon, Control Y-0000, PI(3)P, Y-P003, PI(4)P Y-P004, PI(5)P Y-P005. GST fusion proteins were mixed with liposomes (total lipid concentration 5 μΜ) in binding buffer (50 mM Tris HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% (v/v) NP-40 and rotated for 30 min at 4 °C. Afterwards, liposomes were centrifuged at 17000 × g 4 °C for 10 min and washed five times with binding buffer. Bound proteins were eluted by the addition of Laemmli sample buffer and incubation at 95 °C for 10 min. Detection was done via western immunoblotting.

Peptide lipid overlay assays

Chemically synthesized biotin-tagged peptides (BIOMATIK, Canada), corresponding to the wild-type polybasic sequence (RLKGKAKSRRSRNPERK) as well as to RK6A mutated one (RLAGAAASAASANPERK), were diluted and incubated with PIP strips using the procedure described above. Detection was carried out using a monoclonal anti-biotin-peroxidase antibody (1:1000, Sigma, A0185, Lot: 00090788) and the TMB substrate.

Coomassie staining and western blot immunodetection

Following SDS-PAGE, proteins were either stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 (Roth, 3862) or they were transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore, IPFL00010). For protein immunodetection on PVDF membranes, the anti-GST-POD (1:1000), the anti-α tubulin DM1A (1:1000, Sigma, T6199, Lot: 110M4849) and the anti-mouse-POD (1:2000, Sigma, A2554, Lot: 109M4835V) antibodies were used. When necessary, mild stripping of PVDF membranes before reprobing was done by incubation in 200 mM glycine, 0.1 % (w/v) SDS, and 1 % Tween 20, pH 2.2 followed by washes with PBS and TBS-T (0.1 % (v/v) Tween 20). Detection was performed with the Immobilon Crescendo Western HRP-Substrate (Millipore, WBLUR0100). In all cases, the protein marker used was the Color Protein Standard marker (New England Biolabs, P7719).

Immunofluorescence

Experiments were carried out using 5-day-old seedlings expressing pPOK2::GFP-POK2 and pPOK2::GFP-POK2 Δ#4 in wild-type and trm678 background. Seedlings were immersed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in PEM buffer (50 mM PIPES, 5 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgSO4·7H2O) pH 6.8 plus 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 for 45 min. After washing with PEM, the cell walls were digested with 0.2% (w/v) pectolyase (Duchefa, P8004) and 0.5% (w/v) cellulase (Sigma, C1184) in PEM pH 5.6, for 25 min at 25 oC. Following rinsing with PEM pH 6.8, cells were permeabilized with 10% (v/v) DMSO and 3% (v/v) NP-40 plus 2% (w/v) BSA (Roth, 0163) in PEM for 1 h. The cells were then incubated overnight with a rabbit anti-GFP (1:500, ChromoTek, pabg1-100, Lot: 70828032ΑΒ) and a YOL1/34 rat anti-α-tubulin (1:500, Millipore, CBL270, Lot: 2036079) and afterward, with Alexa fluor 488-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit (1:500, Jackson Immunoresearch, 111-545-144, Lot: 164430) and anti-rat cy3 (1:500, Jackson Immunoresearch, 112-165-003, Lot: 104437) antibodies for 1 h. Finally, seedlings were mounted on a DAPI-containing mounting medium (Vectashield Vector laboratories, H-1800).

Oryzalin treatment

Young seedlings expressing GFP-POK2 in trm678, were treated with 10 μΜ oryzalin (Supelco, PS-410). Confocal images of the same root meristem region were obtained before and after treatment. Treatment was performed by adding an aqueous solution of oryzalin at one edge of the microscope slide and simultaneously, by removing the mounting medium from the other edge using filter paper. During oryzalin treatment, Z-stacks were taken at 2 min intervals.

Microscopy imaging and image processing

Imaging was performed at constant room temperature (22 oC). A Leica TCS-SP8 equipped with a resonant scanner, Argon/Krypton mixed gas laser and He/Ne laser, hybrid detectors (HyD) and standard PMT detectors, objective 20x (NA = 0.75) or 63x (NA = 1.20) water immersion objective, was used for imaging. For excitation of GFP, the 488 nm laser line was used and fluorescence signal was detected between 493–550 nm (GFP). RFP and propidium iodide were excited with 561 nm solid-state laser, and the detection windows were 576-639 nm, and 577-632 nm, respectively. Z-projections and three-dimensional (3D) reconstructions of image stacks were generated using Fiji (ImageJ, https://imagej.net/Fiji). Linear color adjustments and color merges were conducted using Fiji, and Adobe Illustrator CS5 v15.0 was used to assemble the Figures. For live cell imaging, in the absence of a reporter, cell walls were stained with an aqueous solution of 2 μg/ml propidium iodide (Sigma, P4170).

Image analysis

Maximum Intensity profiles were performed in single-plane images using ImageJ. Orientation of microtubules and POK2 filamentous structures in wild-type and trm678 seedlings after immunolabeling of tubulin was performed with the fibril tool ImageJ plugin33 in cortical maximum Z-projections following manual rolling bar background subtraction. Correlation-based Manders’ coefficient (tM1 and tM2) analysis of filamentous POK2 signal and microtubules in prophase wild-type and trm678 cells was performed using the Coloc2 ImageJ plugin (http://imagej.net/Coloc_2). CDZ localization width of the POK2 signal was quantified with ImageJ, measuring the length of segmented lines drawn along the GFP signal at the cortex in single Z-projections of median cell planes. Cell wall orientation angle measurements was performed, measuring the angles of cell walls relative to the axis of the respective cell file in epidermal and cortex root cells.

MT-cosedimentation assay

The percentages of pelleted proteins were quantified based on the images of the Coomassie-stained polyacrylamide gels using the gel analysis command of ImageJ. First, the lanes with the supernatant and pellet fraction of a sample were selected. In the intensity plot, the area of the peaks corresponding to the protein of interest was measured and the percentage of protein amount in the soluble and pellet fractions calculated.

Localization patterns of POK2 fusion proteins

Dividing cells from seedlings co-expressing the fusion proteins along with the microtubule reporter RFP-MBD3 were classified into individual cell cycle stages, based on microtubule array organization. For determining the presence or absence of a GFP signal at a distinct subcellular location, only cells exhibiting RFP-MBD were taken into consideration. In the case of GFP-POK2 #5 + 15RKtoLGGYV + RK6A the cell cycle stage was determined by the presence of nucleus, the decoration of bipolar arrays by GFP signal and the brightfield views. For assessment of the localization patterns of POK2 GFP-fusion proteins in wild-type and trm678 cells, transgenic T2 seedlings were used following immunodetection of GFP and α-tubulin and DAPI staining. Classification into cell cycle stages was based on the organization of microtubules and of the chromatin.

Statistics and reproducibility

All experiments were repeated independently at least twice and produced reproducible results. Microscopic images of plant cells are representative of results obtained in at least 3 biological independent experiments. No data were excluded from the analyses. For statistical analyses, a minimum of n = 3 biological replicates were used. The statistical analysis for Fig. 1l was performed using a two-sided Wilcoxon-signed-rank test. In the case of anisotropy measurements of filamentous POK2 and premitotic microtubules in the same cells (Fig. 6f), significance values were determined using Two-way ANOVA (GraphPad Prism 10) and equality of variances was assayed using a two-sided F-test (https://www.statskingdom.com/). In all other cases, the significance values (p) were determined using One-way ANOVA with the Post Hoc HSD (https://astatsa.com/OneWay_Anova_with_TukeyHSD/). Graphs, line plots, and box plots were constructed using Graphpad Prism.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data of this study are available within the article, the Supplementary Information files and the Source Data files that accompany this article. Accession codes used in this study are AT3G19050 and AT5G22880. Source data are provided in this paper.

References

Delwiche, C. F. & Cooper, E. D. The evolutionary origin of a terrestrial flora. Curr. Biol. 25, R899–R910 (2015).

Buschmann, H. & Müller, S. Update on plant cytokinesis: rule and divide. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 52, 97–105 (2019).

Lipka, E. et al. The phragmoplast-orienting kinesin-12 class proteins translate the positional information of the preprophase band to establish the cortical division zone in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 26, 2617–2632 (2014).

Livanos, P. & Müller, S. Division plane establishment and cytokinesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 70, 239–267 (2019).

Müller, S. Update: On selected ROP cell polarity mechanisms in plant cell morphogenesis. Plant Physiol. 193, 26–41 (2023).

Glanc, M. Plant cell division from the perspective of polarity. J. Exp. Bot. 73, 5361–5371 (2022).

Rasmussen, C. G., Wright, A. J. & Müller, S. The role of the cytoskeleton and associated proteins in plant cell division plane determination. Plant J. 75, 258–269 (2013).

Smertenko, A. et al. Plant cytokinesis: Terminology for structures and processes. Trends Cell Biol. 27, 885–894 (2017).

Müller, S. & Livanos, P. Plant kinesin-12: Localization heterogeneity and functional implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 4213 (2019).

Herrmann, A. et al. Dual localized kinesin‐12 POK2 plays multiple roles during cell division and interacts with MAP65‐3. EMBO Rep. 19, e46085 (2018).

Müller, S., Han, S. & Smith, L. G. Two kinesins are involved in the spatial control of cytokinesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr. Biol. 16, 888–894 (2006).

Walker, K. L., Muller, S., Moss, D., Ehrhardt, D. W. & Smith, L. G. Arabidopsis TANGLED identifies the division plane throughout mitosis and cytokinesis. Curr. Biol. 17, 1827–1836 (2007).

Xu, X. M. et al. RanGAP1 is a continuous marker of the Arabidopsis cell division plane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 18637–18642 (2008).

Stöckle, D. et al. Putative RopGAPs impact division plane selection and interact with kinesin-12 POK1. Nat. Plants 2, 16120 (2016).

Spinner, L. et al. A protein phosphatase 2A complex spatially controls plant cell division. Nat. Commun. 4, 1863 (2013).

Schaefer, E. et al. The preprophase band of microtubules controls the robustness of division orientation in plants. Science 356, 186 (2017).

Bouchez, D., Uyttewaal, M. & Pastuglia, M. Spatiotemporal regulation of plant cell division. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 79, 102530 (2024).

Chugh, M. et al. Phragmoplast orienting kinesin 2 is a weak motor switching between processive and diffusive modes. Biophys. J. 115, 375–385 (2018).

Zhu, Y., Tan, W. & Lee, W. L. An in vitro microscopy-based assay for microtubule-binding and microtubule-crosslinking by budding yeast microtubule-associated protein. Bio Protoc. 8, e3110 (2018).

Marc, J. et al. A GFP-MAP4 reporter gene for visualizing cortical microtubule rearrangements in living epidermal cells. Plant Cell 10, 1927–1940 (1998).

Cho, H. P. et al. The dual-specificity phosphatase CDC14B bundles and stabilizes microtubules. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 4541–4551 (2005).

Sturgill, E. G. et al. Kinesin-12 Kif15 targets kinetochore fibers through an intrinsic two-step mechanism. Curr. Biol. 24, 2307–2313 (2014).

Damme, V. Cortical division zone establishment in plant cells. Trends Plant Sci. 12, 458–464 (2007).

Brzeska, H., Guag, J., Remmert, K., Chacko, S. & Korn, E. D. An experimentally based computer search identifies unstructured membrane-binding sites in proteins: Application to class I MYOSINS, PAKS, and CARMIL. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 5738–5747 (2010).

Platre, M. P. & Jaillais, Y. Anionic lipids and the maintenance of membrane electrostatics in eukaryotes. Plant Signal. Behav. 12, e1282022 (2017).

Barbosa, I. C. R. et al. Phospholipid composition and a polybasic motif determine D6 PROTEIN KINASE polar association with the plasma membrane and tropic responses. Development 143, 4687–4700 (2016).

Liu, P. et al. PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-dependent activation of the mTORC2 kinase complex. Cancer Discov. 5, 1194–1209 (2015).