Abstract

Understanding how Earth’s continental nuclei first formed in the Archean eon (4.0–2.5 Ga) underpins our notions of early Earth geodynamics. Yet, the nature of Earth’s early protocrust and the primary mechanism for its transformation are poorly understood, as very ancient rocks preserving petrological evidence for these processes are incredibly rare. Here we report the discovery of a formerly melt-bearing amphibolite from the Sylvania Inlier of the Pilbara Craton in Western Australia. Radiometric dating of zircon and titanite in these rocks constrain the time of partial melting to 3565 Ma, providing evidence for a metamorphic event that predates most exposed rocks in the Pilbara Craton by ~30 million years. Low δ18O compositions and modelled melt compositions comparable to evolved Hadean rocks in the Acasta gneisses indicate Earth’s oldest continental crust may have sourced rocks of a similar composition. Thermodynamic modelling suggests partial melting at temperatures of 680–720°C and pressures of 0.8–1.0 GPa, implying a maximum burial depth of ~30 km. These results support models of continental nuclei formation via shallow partial melting of hydrothermally altered mafic protocrust in high heat flow environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although there is evidence for the existence of some felsic (silica-rich, continental) crust on Earth as early as 4.4 billion years (Gyr) ago1, data from rare exposures and very ancient detritus indicate Earth’s continents were built from pre-existing mafic nuclei (protocrust) and subordinate precursory continental crust (PCC) formed between the late Hadean and early Paleoarchean (4.03–3.5 Gyr ago)2,3,4,5,6,7. However, the physical processes involved and tectonic setting in which these ancient continental nuclei formed are debated8.

One prominent occurrence of ancient rocks resembling PCC are the 4.02 Gyr old Idiwhaa tonalite gneisses within the Acasta Gneiss Complex (AGC) of the Slave Craton in northwest Canada2,3. These rocks are geochemically distinct from younger Archean tonalite–trondjemite–granodiorite (TTG) series rocks in having high total iron (FeOT) and correspondingly low Mg# (atomic Mg/(Mg + Fe2+), low Sr/Y and Gd/Yb ratios, and containing primary (magmatic) zircon with sub-mantle (isotopically light) oxygen isotope compositions (δ18O < 4.7‰)2,3. These geochemical features resemble those of modern felsic crust produced by shallow (upper crustal; ≤ 15 km) magmatic fractionation and assimilation in Iceland (so-called Icelandites), suggesting Earth’s first continental nuclei may have formed in a similar manner2,3. However, an alternative model for Icelandite-like rocks involves shallow-level (uppermost few kilometres) partial melting of hydrothermally altered mafic crust9. Unlike with modern Icelandites, this could have occurred in response to intense meteorite bombardment on a planet with surface water during the Hadean to early Archean10,11.

Felsic rocks containing zircon with isotopically light δ18O compositions have since been documented amongst the oldest preserved parts of other Archean cratons, including in the Western Australian Pilbara and Yilgarn cratons11, indicating that the processes that produced the Idiwhaa tonalite gneisses may have been typical. Key to the origin of these ancient (c. 4.02 Gyr old) gneisses are their mafic host rocks, which include Fe-rich garnet-bearing amphibolites that are older than 4.02 Ga based on cross-cutting relationships, and represent rare remnants of the Hadean protocrust12. However, the protracted polymetamorphic history of the AGC has seemingly destroyed the primary mineralogical/petrological features of these rocks, obscuring any genetic link to the ancient felsic rocks3,12.

Here, we report formerly melt-bearing (migmatitic) Paleoarchean amphibolites from the Sylvania Inlier of the Pilbara Craton. Integrating detailed petrological observations with geochemistry, geochronology, phase equilibrium and geochemical modelling, we show that these rocks are suitable analogues for Earth’s reworked early (Hadean to early Archean) mafic protocrust. By constraining the pressure (P), and temperature (T) conditions these rocks formed under, we probe the thermal regime in which Earth’s first enduring continental nuclei originated.

Results & Discussion

Geological setting, petrology and mineral chemistry

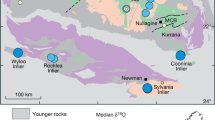

The Pilbara Craton of Western Australia preserves well-exposed weakly deformed and metamorphosed Archean rocks that represent a key geological repository of the early Earth13. In the dominantly Paleoarchean (3.6–3.2 Ga) East Pilbara Terrane, metamorphic grades are low (< or <<500°C) and higher grade (amphibolite to granulite facies) migmatitic metabasic rocks that might be the residual protoliths of the TTG-dominated crust are not exposed. However, in the Sylvania Inlier, south of the East Pilbara Terrane and at the margin of the Pilbara Craton (Fig. S1), Proterozoic orogenesis has exhumed such high-grade rocks14, potentially providing a window into Earth’s primitive protocrust.

The northern part of the Sylvania Inlier contains a package of ‘hybrid intermediate rock’ on the western margin of a greenstone belt (Fig. S1a, b)15 from which two samples of metatonalite (samples 216545 & 216594) have been investigated previously11. The rocks comprise 35–40% plagioclase, 35–40% quartz and 2–3% garnet with minor biotite, ilmenite, and titanite. Secondary epidote replaces plagioclase (5–6%) and chlorite locally replaces garnet (Fig. S2). Zircon from the metatonalite dated by SHRIMP U–Th–Pb geochronology yield ages of 3565 ± 3 Ma and 3566 ± 5 Ma11. Notably, these grains have low δ18O oxygen isotopic compositions (3.76–3.95‰)11, a feature shared by some Hadean zircon from the Idiwhaa tonalite gneiss of the AGC2,3. The focus of this study concerns two additional samples from the same geological unit within the Sylvania Inlier that are considerably more mafic than those previously reported (Fig. 1a–d). Macroscopically, the rocks are dominated by a fine-to-medium grained melanocratic matrix (melanosome) with variable quantities of quartzofeldspathic leucosome (Figs. 1c, d, S1 & S2), interpreted to reflect partial melting at the metamorphic peak.

Photomicrographs of amphibolites from the Sylvania Inlier showing their bulk mineralogy (a), evidence for partial melting including former melt pockets (b) and crystallised melt with idiomorphic plagioclase crystals and graphic texture (c), and titanite forming coronae around ilmenite. hbl = hornblende, ilm = ilmenite, ttn = titanite, ep =epidote, pl = plagioclase and q = quartz (d). e. Ternary diagram comparing the major element chemistry of the amphibolites and ‘metatonalites’ to Hadean-Eoarchean rocks in the Acasta Gneiss complex, mafic rocks from the Pilbara Craton and a global compilation of Archean TTG series rock (all normalized to 100% in the NCKFMASTO chemical system after ref. 10). f Chondrite normalised rare earth element (REE) distribution diagram comparing rocks from the Sylvania Inlier to a selection of other mafic rocks from the Pilbara Craton18,28. The average Apex and CF-2 compositions denote a typical tholeiitic and enriched basalt respectively (following Smithies et al.28), which are similar to the high TiO2 and intermediate TiO2 groups of the Mt Ada Basalt from Murphy et al.18.

The melanosome is mostly composed of amphibole + quartz + plagioclase + ilmenite + titanite with secondary epidote (Fig. 1a–d). Electron-probe microanalyser (EPMA) analyses classify the calcic amphibole as hornblende with AlT = 0.47–1.84 (Si = 7.53–6.16), Na + K(A) = 0.09–0.53, and Mg/(Mg + Fe) = 0.29–0.57, ranging from ferro-tchermakite to magnesio-hornblende/actinolite in a plot of Mg# versus Si content (Fig. S3). The leucosome is dominated by quartz and plagioclase in roughly equal proportions, and contains abundant accessory zircon. Plagioclase is extensively replaced by sericite and epidote, but where fresh, preserves lamella twinning and is albite to oligoclase in composition (XAn (atomic Ca/Ca + Na + K) = 0.03–0.31; Fig. S3). Preserved igneous textures in the leucosome include coarse-grained idiomorphic plagioclase crystals surrounded by finer-grained intergrowths of quartz and plagioclase (Fig. 1c), the latter resembling graphic textures common in pegmatites formed by crystallisation of volatile-saturated eutectic (minimum) granitic melts16. We interpret these quartzofeldspathic domains as the crystallized products of a hydrous partial melt formed during the prograde-to-peak metamorphic history.

Titanite is almost exclusively found as clusters of randomly oriented granules forming coronae around ilmenite crystals within the melanosome (Fig. 1d). Detailed backscattered electron (BSE) imaging of this titanite reveals relic grains of ilmenite, with titanite forming interconnected fracture networks in the cores of ilmenite where preserved (Figs. 1d, 2b). These observations indicate the titanite grew via the breakdown of ilmenite. In places, entrained fragments of matrix containing hornblende and titanite–ilmenite within larger leucosome segregations suggest ilmenite breakdown (and titanite growth) predated melt crystallisation and may have predated or been coeval with partial melting.

a High-resolution BSE and cathodoluminescence (CL) image of a zircon crystal from the amphibolite showing primary anatectic zircon crosscut by recrystallisation fronts and mottle-texture zircon. Red ellipses denote SHIRMP U-Pb analysis spots with corresponding common-Pb corrected 207Pb/206Pb dates, and white ellipses denote SIMS oxygen isotope analyses spots and δ18O (VSMOW) composition. b BSE image of titanite-ilmenite corona showing granular titanite texture and relic inclusions of ilmenite in titanite. c, d Stacked Tera-Wasserburg concordia diagram and box diagram showing U-Pb isotope composition of titanite(red) and zircon (green) in the amphibolite, and the weighted average U-Pb dates for each mineral respectively. e. Plane polarised light photomicrograph of garnet in the metatonalite. f Inverse Lu-Hf isochron diagram for garnet from the metatonalite showing that garnet in the metatonalite is the same age as zircon and titanite in the amphibolite. g. Kernel density estimate for a compilation of detrital and inherited zircon in rocks from the Pilbara Craton showing that partial melting in the rocks from the Sylvania Inlier occurred during an inferred major period of felsic crust production.

Geochemistry & Geochronology

Compared to the metatonalite samples, the amphibolites have low to moderate SiO2 (58–63 wt% versus 74–76 wt%), higher FeOT (8–12 wt% versus 3–4 wt%), MgO (2–3 wt% versus 0.2 wt%), CaO (6–8 wt% versus 2–3 wt%) and TiO2 (1–2 wt% versus 0.5 wt%), and similar Al2O3 (~13 wt%) contents. The most mafic samples (e.g. 255836) have flat to slightly positively sloping rare earth element (REE) patterns (Fig. 1f), with chondrite-normalised La/Yb ratios between 0.39 and 0.86. The concentrations of heavy REE (HREE) and high field-strength elements (HFSE; including Zr, Hf, Ti) in the amphibolites are similar to those of high-TiO2 basalts and the Coucal basalts (CF-2 in Fig. 1f) from the lower Warrawoona Group of the East Pilbara Terrane17,18. However, lower light REE (LREE) contents in the studied rocks result in strong positive Zr and Hf anomalies in primitive-mantle normalised distribution diagrams (Fig. S3a). This observation suggests that depletion in LREE might reflect fluid alteration that preferentially removed LREE over more immobile elements. In more leucocratic (formerly more melt-rich) samples (e.g. 255834), the depletion in LREE is more pronounced, resulting in stronger positive Eu anomalies (Eu/Eu* = 1.49–2.38, where Eu/Eu* is chondrite normalised \({Eu}/\sqrt{({Sm}\times {Gd})}\)) relative to more mafic samples (255836, Eu/Eu*= 1.21–1.31,) (Fig. 1f).

In situ zircon and titanite U–Th–Pb geochronology was undertaken to determine the age of the studied amphibolites. Detailed analytical and standardisation procedures are described in the Methods section, and a table of results are provided as supplementary materials. In BSE and cathodoluminescence (CL) images, most zircon grains are strongly altered and exhibit mottled textures, although some crystals preserve relatively unaltered areas with oscillatory zoning (Figs. 2a and S4). In sample 255834, a cluster of concordant analyses from these unaltered domains within zircon yield a date of 3567 ± 4 Ma, identical to that of zircon grains in the metatonalites (3565 ± 3 Ma and 3566 ± 5 Ma)11. After filtering for U–Pb concordance and secondary water content (measured via 16O1H, see Methods and Supplementary Information for details), in situ 18O/16O isotope measurements on these domains (presented as δ18O normalized to Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water) give δ18O values between 3.40 and 4.26 ‰ with a median value 3.86 ± 0.44‰ (2 s.d., n = 14), which is identical to zircon from the metatonlite11. A cluster of concordant U–Pb isotope analysis of the granular titanite overgrowths on ilmenite yield an age of 3565 ± 10 Ma (Fig. 2b–d). An in-situ Lu–Hf isotope analysis of garnet from a sample of the metatontalite yields a date of 3550 ± 60 Ma (216594, Fig. 2e, f).

Although it is possible that the zircon in the amphibolites is igneous in origin and crystallised during the emplacement of the mafic precursor, we infer an anatectic origin given the clear evidence for partial melting and similarities with zircon in the metatonalite noted above. Collectively, these data provide strong evidence that metamorphism and partial melting of the amphibolite was coeval with formation of the tonalites, implying a genetic link. The scatter in U–Pb isotope systematics correlates with the presence of mottle-textures and/or recrystallisation fronts within zircon (Fig. 2a), and minor disturbance in the U–Pb systematics of titanite is likely related to hydrothermal activity associated with deposition of the Fortescue and Hamersley basins around 2800–2700 Ma (Fig. 2c)19. Nevertheless, the unaltered zircon, titanite and garnet ages coincide with a distinct age mode of detrital and inherited zircon crystals from the East Pilbara Terrane (Fig. 2g)20,21, indicating that partial melting of the Sylvania amphibolite occurred during a major (tectono)thermal event that may have driven the earliest phase of felsic crust production within the Pilbara Craton. As such, these rocks offer a rare glimpse into the mafic source regions for the first felsic crust that formed in the Pilbara Craton.

Phase equilibrium modelling & thermobarometry

To determine the P–T conditions at which partial melting occurred, and hence estimate the depth of felsic crust production, phase equilibria were modelled using the software thermocalc22. Calculations were performed in the Na2O–CaO–K2O–FeO–MgO–Al2O3–SiO2–H2O–TiO2–O (NCKFMASHTO) chemical system using the measured (XRF) bulk compositions of samples 255836 and 255834 assuming an Fe3+/ΣFe ratio of 0.2, and measured loss on ignition as a proxy for H2O contents of 1.15 wt% and 0.82 wt% respectively.

A simplified P–T phase diagram calculated in the range 0.2–1.2 GPa and 600–800°C (Fig. 3a) shows the inferred peak stability fields for both rocks, along with phase boundaries denoting the appearance and disappearance of major phases. In the most mafic sample (255836), the inferred peak metamorphic assemblage of hornblende + plagioclase + quartz + titanite + melt implies temperatures of 650–720°C and pressures of 0.7–0.8 GPa (Figs. 3a & S8a). The upper pressure limit is defined by the garnet-in phase boundary, whereas the lower pressure limit is constrained by the biotite-out phase boundary to lower temperatures and ilmenite-in phase boundary to high temperatures. A minimum temperature of 650°C is demarcated by the appearance of melt (solidus), and an upper temperature limit by the appearance of ilmenite.

a Simplified pressure-temperature phase diagram (P–T pseudosection) showing fields for the inferred peak metamorphic assemblages, phases boundaries for important minerals and melt, and results of Zr-in-titanite thermometry. b Diagram of apparent Zr-in-titanite temperature against cooling rate, depicting the effect of post-crystallisation Zr diffusion in titanite for different grain sizes and starting temperatures during cooling. c Simplified ternary diagram showing melt evolving to compositions approaching metatonalites and Idiwhaa Gneisses as temperature increase along geotherms ranging from 700–1000°C.GPa-1. Note these melts are more Fe-rich than most Archean TTG. d Comparison of modelled trace element distributions for melts along a geotherm of 1000°C.GPa-1 showing good agreement in HREE with some naturally observed Fe-rich tonalites from the AGC and Pilbara Craton3,4.

At the inferred peak metamorphic conditions, the models predict 2–5 mol% melt, consistent with the observed proportion of leucosome in hand specimen (Fig. S1c). The phase diagram for sample 255834 is broadly similar, although the inferred peak stability field spans a larger pressure range as the stability of garnet is restricted to higher pressures (Fig. 3a, Fig. S8b). The model for sample 255834 has no clinopyroxene-free assemblages in the P–T window of interest, with minor clinopyroxene (<5 mol%) predicted to be present. This could reflect limitations in the current activity–composition models for metabasic rocks, which have been shown to underestimate the amount of hornblende and over estimate that of clinopyroxene, particularly in rocks with high modal abundances of the former23. Nevertheless, within the inferred peak stability field for sample 255834, the predicted titanite Zr concentrations (10–110 ppm, see Methods) are in excellent agreement with measured values (19–151 ppm, n = 128), providing an independent average temperature constraint of 693 ± 35°C using the temperature–concentration relations of ref. 24. (Fig. 3a).

The good agreement between the phase equilibrium models for the two different samples and Zr-in-titanite thermometry suggests that the inferred peak P–T conditions are robust. These data translate into an apparent geotherm (or thermobaric ratio, T/P) between 700 and 1000°C.GPa−1. From the topology of both diagrams the formation of the observed ilmenite–titanite reaction textures can be explained by near isobaric cooling from temperatures greater than 740–780°C. If so, the absence of any garnet in the metamorphic assemblage indicates these rocks may have been buried along a geotherm warmer than 1000°C.GPa-1, so as not to intersect the garnet stability field during their prograde P–T evolution. Using finite-difference models for Zr diffusion in titanite25 we show that, for grains with radii of 5–30 µm, the predicted apparent Zr-in-titanite temperatures match the naturally observed distribution over a large range of cooling rates (1–100°C.Myr-1, Fig. 3b).

The replacement of ilmenite by titanite has also been documented in mafic granulites hydrated during their retrograde evolution26,27. In these cases, titanite growth is generally associated with the conversion of anhydrous minerals like clinopyroxene and orthopyroxene into (OH–-bearing) amphibole. Although there is no evidence for any pre-existing pyroxene in these rocks, the titanite grains do exhibit lower F contents relative to Al and Fe than predicted by (Al + Fe3+) + F = Ti + O substitution reactions27 (Fig. S3d). The titanite chemistry implies additional OH– within the titanite lattice to maintain the charge balance, consistent with a fluid phase being present when titanite grew27. On a temperature–MH2O (mol% H2O) diagram (Fig. S9a) this pathway is depicted by increasing MH2O at constant temperature. Importantly, in this region of the temperature–MH2O diagram, the titanite-in, ilmenite-out and melt-in (solidus) lines all have steep negative slopes and are sub-perpendicular to the MH2O axis. Hence, a fluid-fluxed melting model can also explain many of the petrological features of these rocks, including the titanite coronae on ilmenite, and lack of anhydrous peritectic minerals. However, given that at low MH2O garnet is also predicted to be part of the subsolidus mineral assemblage, and the low zircon δ18O compositions imply a hydrothermally altered protolith, a model of closed-system (constant MH2O) burial, heating and cooling along a high geotherm is perhaps most likely.

Constraints on the source of early felsic crust

The new geochronological data, petrological observations and thermodynamic modelling indicate that the studied amphibolites are suitable source rocks for the metatonalites that represent some of the earliest felsic crust in the Pilbara Craton (Fig. 3). Accordingly, 15–35% partial melting of source rocks with a mineralogy similar to the Sylvania amphibolites can produce melts with major element and HREE chemistry matching naturally observed Eoarchean-to-Paleoarchean Fe-rich tonalites from the Pilbara craton over the observed range of apparent geotherms (700–1200°C.GPa-1, Fig. 3c, d).

However, there are several key differences. The depletion in LREE relative to HREE is not typically observed in other (known) old mafic components of the Pilbara Craton21, which generally show flat to positive sloping chondrite normalised REE patterns12,28. Thus, the depletion of LREE relative to HREE and other HFSE like Zr, Hf and Ti may reflect the hydrothermal history of the rocks. Detailed work on element gains and losses from the 3481 Ma Dresser hydrothermal system in the East Pilbara Terrane shows that LREE are notably mobile in high-temperature amphibole–chlorite- dominated alteration assemblages, which in some places show depletion in LREE relative to HREE and other immobile elements29. Importantly, the mobility of LREE is not uniform across the system, even among rocks with similar alteration assemblages. Assuming the hydrothermal system that affected the basalts in the Dresser Formation is analogous to that which affected the Sylvania amphibolites, a spectrum of compositions, including LREE-enriched and LREE-depleted components might be expected. The apparent dominance of LREE-enriched compositions among ancient crustal melts shown in Fig. 3d could reflect the fact that LREE-depleted rocks like the Sylvania amphibolites are minor components of these ancient hydrothermal systems. Such complexity will not affect metamorphic phase relations, which will be similar for rocks with similar major element chemistry, irrespective of their trace element concentrations.

Despite the fact that, in both cases, the modelled melts are depleted in LREE relative to the naturally observed rocks, highlighting important contributions from enriched material, the Sylvania amphibolites are good petrological analogues for the source of the metatonalites. The major element composition of the metatonalites from the Sylvania Inlier also lies close to the melting paths depicted in Fig. 3c. However, none of the modelled trace element distributions for the melt match their observed trace element patterns (Fig. 1f), indicating that the metatonalites are not simply partial melts of the amphibolite. Rather, the concave up (‘U-shaped’) REE profile of these rocks and strong positive Eu anomaly suggests they formed via plagioclase accumulation, with the slight positive sloping HREE attributed to the presence of garnet, indicating a more complicated petrogenetic history.

Interestingly, the Sylvania amphibolites also share many geochemical features of the Hadean rocks of the AGC (the Idiwhaa tonalitic gneiss and garnet amphibolites)2,3,12, including intermediate SiO2, low Al2O3, elevated FeOT/MgO, and low FeOT/TiO2, the latter on account of high TiO2 contents. Although the absolute FeOT content is lower than the most Fe-rich components of the AGC (garnet amphibolites), the more Fe-rich samples of the Sylvania amphibolites (255836) have similar FeOT/MgO and FeOT/TiO2 ratios to the AGC garnet amphibolites (Fig. 1e). Moreover, the presence of low δ18O magmatic zircon in rocks from the AGC and the Sylvania Inlier indicate that, in both cases, the mafic source rocks experienced high-temperature isotopic exchange with Archean seawater2,3. The major and trace element modelling also confirms the Sylvania amphibolites as suitable sources to the Idiwhaa tonalite gneiss, although this would require heating to temperatures beyond amphibole stability (>825°C) along very high geothermal gradients exceeding 1200°C.GPa-110. Therefore, Earth’s first felsic crust may have had similar source rocks.

Implications for early Achean crust-forming processes

The ‘hybrid-intermediate rock unit’15 from the Sylvania Inlier represents the metamorphosed remnants of some of the earliest mafic crust from the Pilbara Craton. Given that similar chemical characteristics are shared by the putative Hadean mafic crust in the AGC, we propose a similar petrogenetic history2,3. The elevated FeOT and TiO2 content (relative to MgO) are indicative of anhydrous (H2O < 0.2 wt%) reduced mantle-derived magma whose liquid lines of descent are controlled by low-pressure fractionation crystallisation with delayed Fe–Ti oxide saturation, similar to those inferred to have produced the mafic rocks in the AGC2,30. That the absolute FeOT and TiO2 content of the garnet amphibolites in the ACG are higher than the majority of mafic rocks in the Pilbara Craton could reflect differences in composition, hydration state and oxygen fugacity of the parental melts. However, it could also indicate that the Sylvania amphibolites formed from melts more chemically evolved than those that produced the Acasta garnet amphibolites, particularly since Fe–Ti oxide saturation will rapidly deplete the residual melt in Fe and Ti as differentiation proceeds. We infer that magmatic differentiation was partly responsible for these differences as the Sylvania amphibolites have comparable FeOT/MgO and FeOT/TiO2 ratios to the Acasta garnet amphibolites at lower MgO and higher SiO2 contents. Nevertheless, the isotopically light δ18O composition (3.86‰) of zircon grains from the amphibolite indicate the protolith also experienced high-temperature (>300–400°C) hydrothermal alteration before partial melting9. Therefore, the original magma must have erupted onto or intruded the shallow crust where it was hydrothermally altered by Archean seawater at high temperature, then finally transported to depths where it began to melt.

Despite the good correspondence between the major element composition of the Sylvania metatonalites and the modelled melt compositions (Fig. 3c), partial melting alone cannot reproduce their trace element chemistry (Fig. 3d). During low pressure differentiation of tholeiitic magmas FeOT enrichment is largely driven by the removal of plagioclase and Mg-rich clinopyroxene, where plagioclase tends to dominate fractionation assemblages (60–75% cumulatively)30, such that the metatonalites could be metamorphosed cumulates formed during differentiation of the parental magmas. However, the Sylvania metatonalites generally lack ferro-magnesian phases, excluding minor garnet and secondary chlorite (Fig. S2), and consequently have lower MgO and CaO, and higher Na2O and K2O contents than mafic cumulates31. Since the age and oxygen isotopic composition of zircon from the metatonalites are identical to the anatectic zircon in the amphibolite, and there is clear textural evidence that plagioclase was an early crystallising phase from small volumes of melt trapped within the amphibolite (e.g. Fig. 1d, e), we interpret the metatonalites to be plagioclase-rich cumulates formed by fractionation of tonalitic crustal melts generated deeper in the crust32. Although no garnet is observed in the exposed amphibolite, the phase equilibrium models predict that garnet will be present at pressures greater than 0.8 GPa, only marginally deeper than the crustal level presently exposed. Therefore, this model can also explain the presence of garnet with an identical age to the zircon and metamorphic titanite in the metatonalites (Fig. 2), which is inferred to be of either magmatic or peritectic origin.

It has been argued that the absence of stable garnet under crustal pressure conditions (<1.4 GPa) in partial melting experiments using basaltic glasses retrieved from modern ocean plateaux environments invalidates an intracrustal origin for early Archean felsic crust33. The results presented here contradict this claim. This discrepancy reflects the strong control of the proportion of FeO to MgO on garnet stability34. We illustrate this point using a pressure–composition (P–XFeO) diagram based on sample 255836B constructed at 700°C (Fig. S9b), where XFeO = FeOT /(FeOT + MgO) in mol%. The pressure at which garnet appears in the metamorphic assemblage is highly dependent on XFeO. At Fe-contents comparable to the bulk composition of modern MgO-rich ocean island basalt used in experimental studies (XFeO = 0.35–0.36) garnet is predicted to be unstable below 1.4–1.5 GPa33. However, at XFeO > 0.62 garnet stability is significantly less sensitive to Fe content and is stabilised between 0.72 and 0.85 GPa (Fig. S9b). Since XFeO for the more mafic Sylvania amphibolites is ~0.68–0.72, the absence of garnet as a residual phase in these melt-bearing metabasic rocks provides a robust maximum pressure (and thereby depth) constraint on melt generation.

Even so, most felsic rocks in Archean cratons were derived from sources with lower XFeO ratios than the mafic rocks described here (e.g. Fig. 1e), and the presence of trace element signatures related to residual garnet in more Mg-rich crustal melts clearly has pressure/depth significance (e.g. Fig. S9). As high XFeO mafic rocks are rare among Archean mafic rocks in general, it is intriguing that such rocks appear to have been involved in the earliest crust formation events in both the Slave and Pilbara cratons2,4. Given their antiquity, we interpret these rare Fe-rich mafic rock to be fragments of the primordial crust that surfaced the early Earth and was largely reworked to become more magnesian during the growth and maturation of the continents (Fig. 4). Considering the two disparate continental nuclei that preserve these Fe-rich rocks formed nearly 500 million years apart suggests that whatever processes produced these continental nuclei were also highly asynchronous.

The circulation of hydrothermal seawater (blue arrows) through faults and fractures (black lines) in the ancient protocrust produces rocks with low δ18O compositions. Subsequent burial and/or heating of this altered protocrust produce tonalitic partial melts (magmas) with low δ18O compositions (orange and yellow polygons). Note that spatial variations in bulk crustal composition (e.g., XFeO) and geotherm may result in both garnet-absent and garnet-present melting. Garnet-present melting will form low-pressure to medium-pressure TTG melts and where geotherms are locally high enough, garnet-absent melting may generate rocks with Icelandite characteristics.

Our thermodynamic modelling indicates that partial melting of Sylvania amphibolites occurred at depths of around 30 km, close to the estimated thickness of primary mafic (mantle-derived) crust predicted for higher Archean potential temperatures (25–35 km)35, and the average crustal thickness from modern oceanic plateaux like at Iceland (29 km)36 and the Ontong-Java plateau (33 km)37. Our results support the notion of continental nuclei formation via intracrustal partial melting and differentiation in high heat flow environments (Fig. 4)2,32.

Methods

Whole-Rock Geochemistry

New data for samples 255834 and 255836 were obtained for this study, following the analytical procedures outlined by Smithies et al.38,39. The analyses were conducted by Bureau Veritas, Perth, Western Australia. Sample preparation involved crushing with a plate jaw crusher and milling in a low-chromium steel mill to produce pulp with a nominal particle size of 90% passing <75 µm. Major and minor elements (Si, Ti, Al, Cr, Fe, Mn, Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba, Na, K and P) contents were measured using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometry on fused glass discs, while loss on ignition was determined by thermogravimetric analysis. Trace elements — including Ag, As, Ba, Be, Bi, Cd, Ce, Co, Cr, Cs, Cu, Dy, Er, Eu, Ga, Gd, Ge, Hf, Ho, La, Lu, Nb, Nd, Ni, Pb, Pr, Rb, Sc, Sm, Sn, Sr, Ta, Tb, Th, Tl, Tm, U, V, W, Y, Yb, Zn and Zr — were measured by laser ablation ICP–MS on a fragment of each glass disk earlier used for XRF analysis. Data quality was monitored by blind insertion of sample duplicates, internal reference materials, and the certified reference material OREAS 24b. BV Minerals also included duplicate samples, certified reference materials (including OREAS 24b), and blanks. Total uncertainties for major elements are ≤1.5 %, those for minor elements are <2.5 % (at concentrations >0.1 wt.%) and those for most trace elements are ≤10 % (Lu ±20 %). Newly acquired (samples 255834 & 255836) and compiled (samples 216545 & 216594) geochemical data are provided in Supplementary Data 1. Chondrite- and primitive mantle–normalized trace element plots use the reference compositions of Sun & McDonough40.

SIMS Analytical Methods

Zircon separated from the leucosome-rich sample 255834 was analysed via secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) on the SHRIMP II ion microprobe at the John de Laeter Centre at Curtin University. Procedures followed those described by Compston et al.41, with modifications summarized by Williams42. A 25 μm diameter primary beam of O2 ions at 10 keV, purified by means of a Wien filter, was employed to sputter secondary ions from the surface of each target zircon grain. The net primary ion current, as measured leaving the sample, was typically 1.7–1.9 nA. Secondary ions are accelerated to 10 keV, energy-filtered by passage through a cylindrical 85° electrostatic analyser with a turning radius of 1.27 m, and mass-filtered using a 72.5° magnet sector with a turning radius of 1 m. Secondary ions are counted by switching the magnetic field to direct the secondary ion beam into an electron multiplier used in pulse-counting mode. During the analytical session, the secondary ion analyser is set to a mass resolution of ≥5000 (1% peak-height definition), which is sufficient to resolve lead isotopes from most potential molecular interferences. During the session analyses of the 91500 zircon reference indicated an internal spot-to-spot (reproducibility) uncertainty of <0.63% (1σ), and a 238U/206Pb* (* = radiogenic) calibration uncertainty of <0.5% (1σ). Analyses of OGC zircon treated as an unknown indicated a yield concordia date of 3464 ± 5 Ma (n = 7, MSWD = 1.5) identical to the reported age, indicating that a 207Pb/206Pb fractionation correction is unnecessary. As a secondary check, GSWA sample 142535 yielded a date of 3246 ± 7 Ma (n = 5, MSWD = 0.86), within uncertainty of the reported SIMS age (3236 ± 3 Ma). Our date being slightly older reflects minor Pb loss that was not accounted for in the previously reported data43. Common-Pb correction used the measured 204Pb and contemporaneous common-Pb isotopic compositions determined according to the model of Stacey and Kramers44. All SIMS U-Th-Pb data are provided in Supplementary Data 2. Cathodoluminescence images showing individual spot locations are provided in Fig. S4a, b. Tera-Wasserburg concordia diagrams for secondary reference materials are shown in Fig. S6a, b.

Following U-Th-Pb isotope analysis, the mount was repolished using a 0.5 µm colloidal silica solution to remove the upper 1–2 µm of the sample surface and the U-Th-Pb analysis pits. Before oxygen isotope analysis, the mount was cleaned in ethanol and distilled water before coating with ~60 nm Au. The mounts were loaded in the vacuum chamber three days prior to analysis to degas. Measurement of oxygen isotopes (18O, 16O, 16O1H) was carried out in the same location as the U-Th-Pb isotope analyses in July 2023 using a CAMECA IMS 1300-HR3 in the John de Laeter Centre at Curtin University. The 133Cs+ primary beam conditions included a + 10 kV acceleration potential, a beam diameter of ~15 µm, and a beam current of ~2 nA.

An individual oxygen isotope analysis lasted approximately ~4 minutes and involved pre-sputtering (rastering) for 60 s over a 10 × 10 µm area to approach sputter equilibrium, automated secondary ion tuning, and 120 s of simultaneous integration of masses 16O, 16O1H, and 18O. A normal incidence electron gun was utilized for charge compensation. The negative secondary ions were extracted from the sample mount (–10 kV potential) into the transfer section of the secondary ion column. Secondary ion transfer conditions included a 5 mm wide field aperture, a 121 µm entrance slit, a 202 µm exit slit, and a 50 eV energy window. The mass-separated oxygen isotopes were detected simultaneously in Faraday cups at the L’2 (16O), FC2 (16O1H) and H1 (18O) positions in the multi-detector array. Mass resolution (M/∆M at 10% peak height) at L’2 and H1 was nominally 2500, and count rates for 16O were ~1.5–2.0 × 109 c/s.

Instrumental mass fractionation was monitored by duplicate analyses of 91500 zircon reference before and after every six unknowns. No significant drift in the IMF was identified during a session. The data for unknowns were corrected in blocks of six unknowns bracketed by two 91500 analyses at the start and end of each block. Individual spot uncertainties at 95% confidence are typically ± 0.26‰ (range: 0.16–0.42‰), and include errors relating to within-spot counting statistics, internal reproducibility of the 91500 reference material, and instrumental mass fractionation. The analytical results for the Plesovice and Mud Tank zircon reference materials, which were treated as unknowns throughout the session, give an error-weighted mean for δ18O = +7.94 ± 0.08‰ (2se, MSWD = 1.19, n = 13), and +4.81 ± 0.07‰ (MSWD = 0.69, n = 13) respectively, with no outliers rejected, and within the uncertainty of the reported values (Fig. S7a). All oxygen isotope data are provided in Supplementary Data 3, and individual spot locations on each crystal are denoted on S4a & b.

δ18O (VSMOW) was calculated as follows:

where 18O/16O (VSMOW) = 0.0020052, and δ18O(VSMOW) is reported in ‰.

In addition, it has been shown that the presence of water in zircon, typically as hydroxyl ions (OH-), indicates potential secondary overprint45,46. Elevated 16O1H/16O values greater than the crystalline reference material implies water within the zircon structure possibly affecting the original δ18O value. Therefore, we also calculated raw 16O1H/ 16O ratios as a qualitative measure of zircon OH- content47. Measured 16O1H/ 16O ratios in zircon reference materials were relatively consistent throughout the run, but show a steady decrease with time, likely related to diminishing outgassing of the epoxy mount with time. This background 16O1H/16O is accurately modelled using a power law function shown in Fig. S6b (R2 = 0.88). The fractional deviation of unknown samples away from the power law model at the same position in the analysis sequence is denoted in Fig. S7b by XOH:

XOH provides a relative measure of the addition OH- present within the zircon crystal. There is a weak correlation (R2 = 0.14–0. 16) between the IMF corrected δ18O values and XOH (Fig. S7c). Unknown analyses with XOH < 0.3 show relatively consistent δ18O compositions, within uncertainty of one another, whereas samples with XOH > 0.3 trend to lower δ18O values with increasing XOH. We therefore apply a cutoff XOH value of 0.3, which roughly corresponds to a 3σ envelope of the model for the standard analyses, to separate zircon preserving primary δ18O compositions from those that have been affected by secondary processes (Fig. S7b and c).

LA-ICP-MS Analysis

Titanite geochronology

U-Pb isotope analysis of titanite was performed in situ on polished thin sections of sample 2555834. Given the small grain size and low U contents, U-Pb isotopic data were acquired on a Nu Plasma II multicollector LA-ICP-MS using ion counter detectors to allow for maximum spatial resolution and sensitivity. The analyses were carried out at the GeoHistory Facility in the John de Laeter Centre, Curtin University. The sample was ablated using a RESOlution 193 nm ArF excimer laser system with a beam diameter of 16 µm. Analyses were performed at a 10 Hz laser repetition rate with a laser energy of 2.6 J.cm-2 as measured on the sample surface. Throughout the ablation, the sample cell was flushed with ultrahigh-purity He (350 ml/min) and N2 (3.8 ml/min).

U–Pb data were processed in Iolite48 using the built-in “Geochronology4” data reduction scheme with MKED1 (1517 ± 0.32 Ma)49 as a calibration standard as its radiogenic Pb/common Pb ratio is fixed. The titanite BLR (1047.1 ± 0.4 Ma)50 was employed as a secondary reference material and treated as an unknown to verify the procedure. For BLR, a model-1 regression through the U-Pb isotopic data from common Pb (approximated Stacey-Kramer common Pb model44) yielded a lower intercept date of 1048 ± 3 Ma (MSWD = 1.6, n = 16), identical to the recommended value. Titanite U–Pb geochronology data are presented in Supplementary Data S4. All uncertainties are reported at a 2σ level. Representative BSE and electron back-scatter diffraction image (EBSD) detailing the textural complexity of the titanite are provided in Fig. S5a, b respectively with several U-Pb analyses locations highlighted. A histogram showing the grain-size distribution (measured as the maximum Feret diameter) of individual titanite crystals is provided in Fig. S5c.

Garnet geochronology

Garnet Lu-Hf geochronology followed methods outlined by Simpson et al.51 and Ribeiro et al.52. In situ Lu–Hf geochronology was performed on polished thin sections at the John de Laeter Centre GeoHistory Facility, Curtin University, Australia. The instrumentation consisted of a RESOlution 193 nm ArF excimer laser equipped with a Laurin Technic S155 sample cell, coupled to an Agilent 8900 triple quadrupole ICP-MS/MS operating with a NH₃/He gas mixture in the reaction cell (20% NH₃ in premixed He). This setup follows the methodology outlined by Simpson et al.51 or Lu and Hf isotope measurements. The laser, gas flow, and mass spectrometer setup are summarised in Supplementary Data 1. A Laurin Technic ‘squid’ aerosol mixing device was used to smooth aerosol pulses between the laser and ICP-MS. Garnet samples were ablated using a fluence of ~3.5 J.cm-2, repetition rate of 10 Hz and a circular laser beam of 90 µm. Garnet reference materials (GWA–1 and GWA–2)52 and NIST SRM 610 were ablated using a circular laser beam of 130 µm and 33 µm, respectively. A low flow rate of N2 (4 ml.min-1) was added to the carrier gas before the ICP torch to enhance sensitivity53, passing through inline Hg traps. To optimise sensitivity, nitrogen (4 ml/min) was added to the carrier gas stream prior to the ICP torch, Instrument tuning was first carried out in single quadrupole mode (no collision gas) using NIST SRM 610 to optimize plasma conditions, suppress oxide interferences, and enhance ¹⁷⁵Lu sensitivity, with a 50 µm beam. Upon switching to MS/MS mode, the ICP-MS was tuned to maximise sensitivity for Hf reaction products using NH3/He. To check for potential systematic errors in Lu/Hf from pulse/analogue (P/A) conversion in the 8900-detector system, we performed repeated measurements of the NIST SRM 610 standard using different spot sizes and detector modes for 175Lu (33 and 64 µm), resulting in a P/A factor of ~0.18.

Lu–Hf isochron ages were calculated using the inverse isochron regression in IsoplotR54,55 with 176Lu decay constant after Söderlund et al.56. Inverse isochron ages and analytical uncertainties are stated at the 2 σ level of confidence (95 % confidence). Garnet GWA–1 (1267.0 ± 3.0)52 was employed as reference material to account for instrumental and matrix effects, and GWA–2 (934.7 ± 1.4 Ma)52 was employed as a secondary age check. GWA–1 yielded a matrix-uncorrected inverse isochron age of 1281 ± 24 Ma (N = 34, MSWD = 1,2), indicating a positive offset of ~1.1 % compared to the isotope dilution Lu–Hf reference age. After applying this correction factor to 176Lu/176Hf ratios (garnet reference materials and unknowns), GWA–2 yielded a matrix corrected inverse isochron age of 944 ± 24 Ma (N = 31, MSWD = 1.1) in agreement with the reference age. All the garnet Lu-Hf isotope data are provided in Supplementary Data 5. Inverse isochron diagrams showing the results for secondary garnet reference materials are provided in Fig. S6d, e.

Titanite Zr concentrations

Zr concentration (and several other major and trace elements) were measured in titanite in a separate analytical session. These measurements were made using the same laser and instrument settings used for U-Pb isotope analysis and element beam intensities were measured on a triple quadrupole Agilent 8900 ICP-MS. The trace element glass standard GSD1 was used as the internal calibration standard with 49Ti as the standard element. Glasses BHVO, NIST SRM 610, NIST SRM 612, and natural titanite MKED1 were run as unknowns to check the accuracy of the data reduction procedure. The median measured Zr concentration and standard deviations (2σ) for these secondary reference materials are provide in Table S1 below. A full table of the LA-ICP-MS trace element data are provided in Supplementary Data 6.

Thermodynamic and Trace Elment Modelling

Pseudosections were calculated using thermocalc v3.5022 and the internally consistent dataset ds63 (created on 05.01.2015) of Holland and Powell57. Pressure--temperature diagrams were constructed in the 10-component Na2O—CaO—K2O—FeO—MgO—Al2O3—SiO2—H2O—TiO2—O2 (NCKFMASHTO) model system. The activity-composition (a-X) models used in this study are: clinoamphibole (actinolite--glaucophane--hornblende--cummingtonite), clinopyroxene (augite) and tonalitic melt of Green et al.58; epidote of Holland and Powell57; ternary plagioclase model (C1) of Holland et al.59,60; chlorite, biotite, muscovite--paragonite, garnet, orthopyroxene of White et al.61; spinel--magnetite of White et al.62; ilmenite of White et al.63; albite, quartz, rutile, titanite and H2O are pure end-member phases. Bulk compositions were converted from weight % oxides to molar % oxides by ignoring minor MnO and P2O5 and assuming that 20 % of total Fe is present as Fe3+. The H2O-content was chosen in order to stabilize the fluid-present solidus over the explored pressure range. Uncertainties for the assemblage field boundaries are approximately ± 1 kbar and ± 50°C at a 2σ level64. Pressure-temperature (P-T) pseudosections for each modelled composition are provided in Fig. S8. Temperature-composition (T-X) and pressure-composition (P-X) pseudosections for sample 255836 are provided in Fig. S9.

Utilizing the same thermodynamic dataset and a–X models as outlined above, Gibbs free energy minimization software PerpleX was used to calculate the composition and abundance of melt and solid (residual) phases at a given pressure and temperature for sample 255836. The calculated residual stable phase assemblage (X, mass fraction), corresponding melt proportion (F), and mineral-melt partition coefficients (Kd) appropriate for partial melting of metabasic rocks65 were used to calculate bulk partition coefficients [Ds = Ʃ(Kd × X)], and thereby constrain the trace element compositions of melts produced along different geothermal gradients. For these calculations, we used the modal batch melting equation66:

where Co and Cm are the concentration of elements in the source rock and melt, respectively.

The Zr contents of titanites can be used as an additional independent geothermometer24; however, the Zr-in-titanite (ZiT) temperature calibration is dependent on several other variables, including the activity of titania (\({a}_{{{TiO}}_{2}}\)), activity of silica(\({a}_{{{SiO}}_{2}}\)) and pressure24. To account for these variables, we calculate titanite Zr ppm P–T contours for the thermodynamic model of sample 255834 using the approach of Yakymchuk et al.67,68, Quartz is predicted to be present across the entire modelled P–T range therefore \({a}_{{{SiO}}_{2}}\) is taken to be 1.0. \({a}_{{{TiO}}_{2}}\) at each P–T point is related to the chemical potential of titania via the expression:

where \({\mu }_{{{TiO}}_{2}}^{P,T}\) is the chemical potential of rutile at a given P–T point, \({\mu }_{{{TiO}}_{2}}^{0}\) is standard state chemical potential of reference (i.e. rutile), R is the universal gas constant and T is temperature in Kelvin. As \({\mu }_{{{TiO}}_{2}}^{P,T}\) and \({\mu }_{{{TiO}}_{2}}^{0}\) may be calculated using thermocalc, one can solve for \({a}_{{{TiO}}_{2}}\) at a given P-T point within the model domain via the expression:

The Zr concentration at each P–T point is then calculated by substituting the relevant values for \(\,{a}_{{{SiO}}_{2}}\), \({a}_{{{TiO}}_{2}}\), P and T into the equation from Hayden et al.24. Titanite Zr concentration contours for sample 255834 calculated via this approach are shown as dashed white lines in Fig. S8b.

EPMA Analysis

Mineral compositions were determined using a JEOL JXA-8530FPlus Hyper-Probe electron probe microanalyzer (EMPA) equipped with an energy-dispersive (ED) and five wavelength-dispersive (WD) spectrometers housed at the Institute of Earth Sciences, NAWI Graz Geocenter, University of Graz, Austria. Measurement conditions were 15 kV accelerating voltage, 10 nA beam current, and a beam diameter of 1–5 µm depending on the analysed mineral. Calibration was carried out using a range of synthetic and natural mineral reference materials. Mineral compositions measured using EPMA are provided in Supplementary Data 7. The calculation of structural formulae from measured weight percent oxide was carried out using the MATLAB programme MinPlot69.

Diffusion Modelling

Apparent Zirconium in titanite temperatures are a function of cooling rate, initial temperature and grain radius, and were calculated using ZirTiDiS (Zirconium in Titanite Diffusion Software)25 executed in MATLAB. ZirTiDiS solves the diffusion equation for a spherical geometry using an implicit finite difference scheme and experimentally-determined diffusion parameters for Zr in titanite70. The initial Zr concentration is calculated for specified starting temperature, pressure and activities of TiO2 and SiO2 using the equation of ref. 24. and allocated to the entire grain. Cooling rates are kept constant for individual runs. During cooling, the boundary condition for equilibrium Zr concentration at the grain rim is calculated at each time step using the Hayden equation. The resulting concentration gradients drive Zr diffusion from grain core to rim, resulting in variable effective Zr concentrations for each cooling history. The final Zr concentration remaining at the grain core is then converted to apparent ZiT temperature with the Hayden equation. The diagrams in Fig. 3b are calculated for cooling from variable initial temperatures (coloured lines) to 600°C at a constant pressure of 8.5 kbar and fixed activities (aTiO2 = 0.8, aSiO2 = 1). It is pointed out that since these values are kept constant during each run, the choice of pressure and activities does not affect the recorded apparent Zr-in-titanite temperature. See Schorn and Moulas25 for details.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are presented in the manuscript and Supplementary Information and Data. These data are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28748390.

References

Wilde, S. A., Valley, J. W., Peck, W. H. & Graham, C. M. Evidence from detrital zircons for the existence of continental crust and oceans on the Earth 4.4 Gyr ago. Nature 409, 175–178 (2001).

Reimink, J. R., Chacko, T., Stern, R. A. & Heaman, L. M. Earth’s earliest evolved crust generated in an Iceland-like setting. Nat. Geosci. 7, 529 (2014).

Reimink, J. R., Chacko, T., Stern, R. A. & Heaman, L. M. The birth of a cratonic nucleus: lithogeochemical evolution of the 4.02–2.94 Ga Acasta Gneiss Complex. Precambrian Res. 281, 453–472 (2016).

Wiemer, D., Schrank, C. E., Murphy, D. T., Wenham, L. & Allen, C. M. Earth’s oldest stable crust in the Pilbara Craton formed by cyclic gravitational overturns. Nat. Geosci. 11, 357–361 (2018).

Kirkland, C. et al. Widespread reworking of Hadean-to-Eoarchean continents during Earth’s thermal peak. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–9 (2021).

Mulder, J. A. et al. Crustal rejuvenation stabilised Earth’s first cratons. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–7 (2021).

Reimink, J. et al. No evidence for Hadean continental crust within Earth’s oldest evolved rock unit. Nat. Geosci. 9, 777 (2016).

Moyen, J.-F. The composite Archaean grey gneisses: petrological significance, and evidence for a non-unique tectonic setting for Archaean crustal growth. Lithos 123, 21–36 (2011).

Bindeman, I. et al. Silicic magma petrogenesis in Iceland by remelting of hydrothermally altered crust based on oxygen isotope diversity and disequilibria between zircon and magma with implications for MORB. Terra Nova 24, 227–232 (2012).

Johnson, T. E. et al. An impact melt origin for Earth’s oldest known evolved rocks. Nat. Geosci. 11, 795–799 (2018).

Johnson, T. E. et al. Giant impacts and the origin and evolution of continents. Nature 608, 330–335 (2022).

Koshida, K., Ishikawa, A., Iwamori, H. & Komiya, T. Petrology and geochemistry of mafic rocks in the Acasta Gneiss Complex: Implications for the oldest mafic rocks and their origin. Precambrian Res. 283, 190–207 (2016).

Van Kranendonk, M. J., Smithies, R. H., Hickman, A. H. & Champion, D. C. Paleoarchean development of a continental nucleus: the East Pilbara terrane of the Pilbara craton, Western Australia. Dev. Precambrian Geol. 15, 307–337 (2007).

Tyler, I. M. & Thorne, A. M. The northern margin of the Capricorn Orogen, Western Australia—an example of an Early Proterozoic collision zone. J. Struct. Geol. 12, 685–701 (1990).

Tyler I. M. The Geology of the Sylvania Inlier and the southeast Hamersley Basin. Geological Survey of Western Australia (1991).

London, D. & Kontak, D. J. Granitic pegmatites: scientific wonders and economic bonanzas. Elements 8, 257–261 (2012).

Smithies, R. H., Van Kranendonk, M. J. & Champion, D. C. It started with a plume–early Archaean basaltic proto-continental crust. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 238, 284–297 (2005).

Murphy, D. et al. Combined Sm-Nd, Lu-Hf, and 142Nd study of Paleoarchean basalts from the East Pilbara Terrane, Western Australia. Chem. Geol. 578, 120301 (2021).

Tyler, I. M., Fletcher, I. R., De Laeter, J. R., Williams, I. R. & Libby, W. G. Isotope and rare earth element evidence for a late Archaean terrane boundary in the southeastern Pilbara Craton, Western Australia. Precambrian Res. 54, 211–229 (1992).

Kemp, A. I., Hickman, A. H., Kirkland, C. L. & Vervoort, J. D. Hf isotopes in detrital and inherited zircons of the Pilbara Craton provide no evidence for Hadean continents. Precambrian Res. 261, 112–126 (2015).

Petersson, A. et al. new 3.59 Ga magmatic suite and a chondritic source to the east Pilbara Craton. Chem. Geol. 511, 51–70 (2019).

Powell, R. & Holland, T. An internally consistent dataset with uncertainties and correlations: 3. Applications to geobarometry, worked examples and a computer program. J. Metamorph. Geol. 6, 173–204 (1988).

Forshaw, J. B., Waters, D. J., Pattison, D. R., Palin, R. M. & Gopon, P. A comparison of observed and thermodynamically predicted phase equilibria and mineral compositions in mafic granulites. J. Metamorph. Geol. 37, 153–179 (2019).

Hayden, L. A., Watson, E. B. & Wark, D. A. A thermobarometer for sphene (titanite). Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 155, 529–540 (2008).

Schorn S., Moulas E. ZirTiDiS: an implicit finite difference code for the calculation of apparent Zr-in-Titanite (ZiT) temperatures (1.0).). 1.0 edn. Zenodo (2024).

Xirouchakis, D. & Lindsley, D. H. Equilibria among titanite, hedenbergite, fayalite, quartz, ilmenite, and magnetite: experiments and internally consistent thermodynamic data for titanite. Am. Mineral. 83, 712–725 (1998).

Harlov, D., Tropper, P., Seifert, W., Nijland, T. & Förster, H.-J. Formation of Al-rich titanite (CaTiSiO4O–CaAlSiO4OH) reaction rims on ilmenite in metamorphic rocks as a function of fH2O and fO2. Lithos 88, 72–84 (2006).

Smithies, R., Champion, D. & Van Kranendonk, M. Formation of Paleoarchean continental crust through infracrustal melting of enriched basalt. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 281, 298–306 (2009).

Caruso, S., Van Kranendonk, M. J., Baumgartner, R. J., Fiorentini, M. L. & Forster, M. A. The role of magmatic fluids in the~ 3.48 Ga Dresser Caldera, Pilbara Craton: New insights from the geochemical investigation of hydrothermal alteration. Precambrian Res. 362, 106299 (2021).

Grove, T. L. & Kinzler, R. J. Petrogenesis of andesites. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 14, 417–454 (1986).

Longhi J. A new view of lunar ferroan anorthosites: Postmagma ocean petrogenesis. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 108, (2003).

Laurent, O. et al. Earth’s earliest granitoids are crystal-rich magma reservoirs tapped by silicic eruptions. Nat. Geosci. 13, 163–169 (2020).

Hastie, A. R. et al. Deep formation of Earth’s earliest continental crust consistent with subduction. Nat. Geosci. 16, 816–821 (2023).

Johnson, T. E., Brown, M., Gardiner, N. J., Kirkland, C. L. & Smithies, R. H. Earth’s first stable continents did not form by subduction. Nature 543, 239 (2017).

Herzberg, C., Condie, K. & Korenaga, J. Thermal history of the Earth and its petrological expression. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 292, 79–88 (2010).

Allen, R. M. et al. Plume‐driven plumbing and crustal formation in Iceland. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 107, ESE 4-1–ESE 4-19 (2002).

Richardson, W. P., Okal, E. A. & Van der Lee, S. Rayleigh–wave tomography of the Ontong–Java Plateau. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 118, 29–51 (2000).

Smithies, R. H. et al. No evidence for high-pressure melting of Earth’s crust in the Archean. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–12 (2019).

Smithies, R. H. et al. Oxygen isotopes trace the origins of Earth’s earliest continental crust. Nature 592, 70–75 (2021).

Sun, S.-S. & McDonough, W. F. Chemical and isotopic systematics of oceanic basalts: implications for mantle composition and processes. Geol. Soc., Lond., Spec. Publ. 42, 313–345 (1989).

Compston, W., Williams, I. & Meyer, C. U‐Pb geochronology of zircons from lunar breccia 73217 using a sensitive high mass‐resolution ion microprobe. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 89, B525–B534 (1984).

Williams, I. S. U-Th-Pb geochronology by ion microprobe. Rev. Econ. Geol. 7, 1–35 (1998).

Nelson D. R. 142535: foliated hornblende-biotite tonalite, Tarlwa Pool. In: in Compilation of SHRIMP U–Pb zircon geochronology data). Western Australia Geological Survey (1998).

Stacey, J. & Kramers, J. Approximation of terrestrial lead isotope evolution by a two-stage model. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 26, 207–221 (1975).

Liebmann, J., Spencer, C. J., Kirkland, C. L., Xia, X.-P. & Bourdet, J. Effect of water on δ18O in zircon. Chem. Geol. 574, 120243 (2021).

Pidgeon, R., Nemchin, A., Roberts, M., Whitehouse, M. J. & Bellucci, J. The accumulation of non-formula elements in zircons during weathering: Ancient zircons from the Jack Hills, Western Australia. Chem. Geol. 530, 119310 (2019).

Liebmann, J., Kirkland, C. L., Cliff, J. B., Spencer, C. J. & Cavosie, A. J. Strategies towards robust interpretations of in situ zircon oxygen isotopes. Geosci. Front. 14, 101523 (2023).

Paton, C., Hellstrom, J., Paul, B., Woodhead, J. D. & Hergt, J. Iolite: Freeware for the visualisation and processing of mass spectrometric data. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 26, 2508–2518 (2011).

Spandler, C. et al. MKED1: A new titanite standard for in situ analysis of Sm–Nd isotopes and U–Pb geochronology. Chem. Geol. 425, 110–126 (2016).

Aleinikoff, J. N. et al. Ages and origins of rocks of the Killingworth dome, south-central Connecticut: Implications for the tectonic evolution of southern New England. Am. J. Sci. 307, 63–118 (2007).

Simpson, A. et al. In-situ LuHf geochronology of garnet, apatite and xenotime by LA ICP MS/MS. Chem. Geol. 577, 120299 (2021).

Ribeiro B. et al. Garnet reference materials for in situ Lu–Hf geochronology: advancing the chronology of petrological processes. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 48, 887–908 (2024).

Hu, Z. et al. Signal enhancement in laser ablation ICP-MS by addition of nitrogen in the central channel gas. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 23, 1093–1101 (2008).

Li, Y. & Vermeesch, P. Inverse isochron regression for Re–Os, K–Ca and other chronometers. Geochronol. Discuss. 2021, 1–8 (2021).

Vermeesch, P. IsoplotR: A free and open toolbox for geochronology. Geosci. Front. 9, 1479–1493 (2018).

Söderlund, U., Patchett, P. J., Vervoort, J. D. & Isachsen, C. E. The 176Lu decay constant determined by Lu–Hf and U–Pb isotope systematics of Precambrian mafic intrusions. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 219, 311–324 (2004).

Holland, T. & Powell, R. An improved and extended internally consistent thermodynamic dataset for phases of petrological interest, involving a new equation of state for solids. J. Metamorph. Geol. 29, 333–383 (2011).

Green, E. et al. Activity–composition relations for the calculation of partial melting equilibria in metabasic rocks. J. Metamorph. Geol. 34, 845–869 (2016).

Holland, T. & Powell, R. Activity–composition relations for phases in petrological calculations: an asymmetric multicomponent formulation. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 145, 492–501 (2003).

Holland, T. J. B., Green, E. C. R. & Powell, R. A thermodynamic model for feldspars in KAlSi3O8− NaAlSi3O8− CaAl2Si2O8 for mineral equilibrium calculations. J. Metamorph. Geol. 40, 587–600 (2022).

White, R., Powell, R., Holland, T., Johnson, T. & Green, E. New mineral activity–composition relations for thermodynamic calculations in metapelitic systems. J. Metamorph. Geol. 32, 261–286 (2014).

White, R., Powell, R. & Clarke, G. The interpretation of reaction textures in Fe‐rich metapelitic granulites of the Musgrave Block, central Australia: constraints from mineral equilibria calculations in the system K2O–FeO–MgO–Al2O3–SiO2–H2O–TiO2–Fe2O3. J. Metamorph. Geol. 20, 41–55 (2002).

White, R., Powell, R., Holland, T. & Worley, B. The effect of TiO2 and Fe2O3 on metapelitic assemblages at greenschist and amphibolite facies conditions: mineral equilibria calculations in the system K2O-FeO-MgO-Al2O3-SiO2-H2O-TiO2-Fe2O3. J. Metamorph. Geol. 18, 497–511 (2000).

Powell, R. & Holland, T. On thermobarometry. J. Metamorph. Geol. 26, 155–179 (2008).

Bédard, J. H. A catalytic delamination-driven model for coupled genesis of Archaean crust and sub-continental lithospheric mantle. Geochim. et. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 1188–1214 (2006).

Shaw, D. M. Trace element fractionation during anatexis. Geochim. et. Cosmochim. Acta 34, 237–243 (1970).

Kirkland, C. et al. Titanite petrochronology linked to phase equilibrium modelling constrains tectono-thermal events in the Akia Terrane, West Greenland. Chem. Geol. 536, 119467 (2020).

Yakymchuk, C., Clark, C. & White, R. W. Phase relations, reaction sequences and petrochronology. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 83, 13–53 (2017).

Walters, J. B. MinPlot: A mineral formula recalculation and plotting program for electron probe microanalysis. Mineralogia 53, 51–66 (2022).

Cherniak, D. Zr diffusion in titanite. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 152, 639–647 (2006).

Acknowledgements

Funding for this work was provided by the Timescales of Mineral Systems Group. S. Schorn acknowledges the Austrian Science Fund (grant P 33002N) and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation for support. TEJ acknowledges support from the Australian Research Council grant DP200101104. We also thank Johann Diener and Martin Van Kranendonk for discussions and Noreen Evans, Brad McDonald, and Kai Rankenburg for analytical assistance. Research at Curtin was enabled by AuScope and the Australian Government via funding from the ARC (LE150100013). R.H. Smithies publishes with permission from the executive director of the Geological Survey of Western Australia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.I.H.H., S.S., T.E.J., A.Z., C.L.K., R.H.S., and M.B. conceived of the study. B.V.R. and A.K.S. performed chemical/isotopic analysis and data interpretation. All authors contributed to writing and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hartnady, M.I.H., Schorn, S., Johnson, T.E. et al. Incipient continent formation by shallow melting of an altered mafic protocrust. Nat Commun 16, 4557 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59075-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59075-9

This article is cited by

-

The evolution of Earth’s early continental crust

Nature Reviews Earth & Environment (2025)