Abstract

Droplet manipulation technologies play a critical role in many aspects of biochemical research, including in complex reaction assays useful for drug delivery, for building artificial cells, and in synthetic biology. While advancements have been made in manipulating liquid droplets, the capability to freely and dynamically manipulate solid objects across aqueous and oil phases remains unexplored. Here, we develop an acoustofluidic frequency-associated microsphere embedding platform, which enables microscale rapid injection of microparticles from a fluorinated oil into aqueous droplets. By observing different embedding mechanisms at low and high acoustic frequencies, we establish a theoretical model and practical principles for cross-phase manipulations. The proposed system not only enables multi-phase manipulation but also provides contactless control of specific microparticles within various distinctive phases. We demonstrate the acoustic-driven embedding and subsequent on-demand disassembly of hydrogel microspheres. This system indicates potential for reagent delivery and molecule capture applications. It enhances existing droplet manipulation technologies by enabling both multi-phase and cross-phase operations, paving the way for solid-liquid interaction studies in artificial cell research. The capability for intricate multi-phase loading, transport, and reactions offers promising implications for various fields, including in-droplet biochemical assays, drug delivery, and synthetic biology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The ability to dynamically and precisely load and manipulate microparticles into nanoliter-sized liquid droplets represents a significant breakthrough with far-reaching applications in droplet microfluidics1,2,3,4. Allowing droplets to interact or exchange with a carrier fluid, such as injecting new reagents or enabling material exchanges, is crucial for micro reaction studies, biosynthesis, dPCR, artificial cells, and other research protocols that require sequential or repetitive addition of multiple reagents or strict control of reaction steps5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Droplet injection, a key technology for active manipulation, uses external forces such as electric pulses5,7,9 or acoustic waves6,8,13 to induce coalescence between target droplets and reagent-containing droplets or fluid5,6,14. This allows researchers to selectively and dynamically alter the chemical composition, concentration gradients, and physical properties of specific microdroplets5,6,7,15. This capability enhances experimental flexibility by enabling real-time adjustments and sequential additions that follow reaction orders.

The vast majority of current droplet injection technologies focus on interactions of droplets with an aqueous fluid7,16,17,18,19,20. These techniques are based on the principle of concentration gradient driven exchange or injection through the fusion of aqueous phase liquids5. These methods, even though efficient, exhibit several limitations. When reagents are injected into droplets, convection usually occurs as the droplet and the injected liquid come into contact and merge21,22. This results in the internal environment of the microdroplet being directly connected to the external environment5, which can lead to issues such as cross-contamination and excess reagent delivery due to delayed disconnections. Preparing the reagents in the form of droplets or solid capsules can effectively solve those problems8,22,23. Droplet fusion technology, which utilize reagent droplets to replace injection fluid, has been extensively studied as a potential alternative to these technologies8,24. While droplet fusion is well-suited for liquid-liquid interactions, research on solid-liquid interactions and multi-phase manipulations remains limited. As a result, particles must first be suspended or resuspended in an aqueous liquid or droplet before being injected using conventional droplet fusion techniques25,26. This process is particularly complex for hydrogels which often requires subsequent oil removal through methods like freeze-drying before resuspending the hydrogel in water25,27,28,29,30. Although the conventional process is well developed, solid reagent carriers are still critically needed because solid capsules or particles offer greater stability, do not self-fuse, and provide better control compared to droplets. Additionally, after injection, microparticles maintain a high contrast with the liquid properties, enabling post-injection control. Therefore, a method that can achieve direct particle embedding into droplets is initially needed. Such a method would enable manipulation of microscale biomaterials and droplets, as well as the microenvironment within droplets. Precision control over solid-liquid interactions in both dispersed and continuous phases can offer new insights into artificial cell research, better mimicking the interactions between cells and solid biomaterials, and advancing studies on drug delivery through cell membranes and into cells12,17,31,32,33,34.

Here, we introduce a system capable of directly embedding microparticles into droplets for biomedical applications: the acoustofluidic frequency-associated microsphere embedding (FAME) platform. This system overcomes previous phase interaction limitations by enabling both multi-phase and cross-phase manipulation capabilities. The FAME system enables the rapid (<100 ms) embedding of microparticles from a fluorinated oil carrier fluid into aqueous droplets. Based on theoretical analysis and practical experimentation with the FAME platform, distinct operating regimes have been identified. Specifically, we explained the mechanism behind the different embedding mechanism that were observed at low frequency (10 MHz) to high frequency (100–150 MHz)35,36,37,38,39. This dual-regime capability allows for the flexible manipulation of droplets and microparticles under various conditions, enhancing the versatility of the system. One of the key advantages of the FAME system is its ability to dynamically manipulate droplets both before and after embedding. This offers unprecedented control over the droplet microenvironment5,7. This capability includes real-time observation of rapid phenomena within droplets, making it possible to monitor and adjust reactions as they occur. This feature is particularly valuable for applications that require precise timing and control, such as drug delivery and molecule capture. We demonstrated the FAME system’s potential through various applications, including the generation and embedding of different types of hydrogel microspheres. Our results highlighted the system’s utility for future applications to embed and release therapeutic agents precisely, as needed. Additionally, the FAME system shows promise in molecule capture, where its ability to manipulate and observe droplets in real time can lead to more efficient and targeted biochemical assays. Our findings demonstrated a significant advancement in droplet microfluidics, opening the doors for efficient “lab-in-a-droplet” studies of biochemical assays, drug delivery, and higher-fidelity synthetic biology.

Results

Embedding microparticles from a fluorinated oil carrier fluid into nanoliter aqueous droplets via FAME

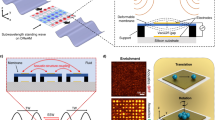

The FAME platform leverages traveling surface acoustic waves (SAW) to embed microparticles from fluorinated oil (FC-40, 3 M™ Fluorinert™ Electronic Liquid FC-40 Materials, 3 M™, USA) carrier fluid into nanoliter-sized aqueous droplets. FAME has a high injection efficiency across a wide frequency range (10–150 MHz) (Fig. 1a). The system operates through two distinct mechanisms at two different frequency ranges. This enables dynamic and precise manipulation of both droplets and microparticles (Fig. 1b). At high frequencies (100–150 MHz), the acoustic radiation force on the droplet becomes significantly smaller than the drag force, making it challenging for the droplet to deform. As the input power increases, the pushing force eventually overcomes the tension at the interface, allowing the microparticle to penetrate the water-oil interface and to be embedded into the droplet (Fig. 1b, left). In contrast, at low frequencies (e.g., 10–30 MHz), the wavelength of the input SAW approaches the diameter of a 100 μm water droplet. Under this condition, the acoustic wave interacts strongly with the target, the acoustic radiation force is significantly enhanced, and the acoustic pressure partially distorts the droplet. As the droplet’s surface tension attempts to restore its natural spherical shape, it encapsulates the microparticle in the process (Fig. 1b, right). This second mode of operation provides a different approach to embedding microparticles into droplets, expanding the versatility and potential applications of the system. Together, these two distinct mechanisms offer a robust and flexible platform for the precise manipulation and embedding of microparticles into nanoliter-sized droplets, enhancing the capabilities of microfluidic systems.

a Water in FC-40 droplets, along with ~15 μm microparticles suspended in FC-40, are injected into the acoustofluidic frequency-associated microsphere embedding (FAME) chip for operation. Subsequently, a focused interdigitated transducer generates a surface acoustic wave (SAW) pulse to embed the microparticles into the target droplets. The side and top views show the microchannel structure of the FAME system. On top of the microchannel are patterned holes for droplet trapping. b Schematic showing the basic structure and the two microparticle embedding modes of the system. Two different SAW frequencies (150 MHz, 10 MHz) drive the microparticle-initiated injection mode and the droplet-initiated encapsulation mode, respectively. The red-to-blue gradient on the surface of the droplet represents the peaks and troughs, respectively, of the traveling waves.

Droplets and microparticles exhibit different responses to acoustic waves at different wavelengths

Using the FAME system, we experimentally demonstrate that large droplets and small microparticles exhibit distinct behaviors under different acoustic wave frequencies. This difference makes the transport of microparticles across a droplet feasible. By gradually increasing the SAW frequencies, the corresponding wavelengths switch in scale from droplet size (~100 μm) to microparticle size (~15 μm), and the influence of the acoustic waves on the microparticles is enhanced (Supplementary Fig. 4)40,41,42,43. This trend is reflected in the vibrometer measurements (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 5, and Fig. 2d).

a Vibrometer measurement of the 10 MHz transducer powered system. Dashed lines: focus line (red); edge line of the wave band (purple); the midline of the edge and focus lines (blue). Data are graphed as the mean value ± SD (N = 30). Scale bar: 100 μm. b Simulation and experimental validation of droplet deformations under different frequencies. As the frequency increases, the overall degree of droplet deformation decreases. Scale bar: 50 μm. c Quantitative relationship between degree of droplet deformation with changes in acoustic frequencies and voltages. The blue area indicates the optimal parameters for successful injection. Data are graphed as the mean value ± SD (N = 10). d Vibrometer measurement of the 150 MHz transducer powered system. Data are graphed as the means ± SD (N = 30). Scale bar: 100 μm. e 1 μm fluorescent particles stream driven by 150 MHz traveling wave. Scale bar: 50 μm. f Snapshots of microparticle motion over 3 ms. Scale bar: 50 μm. g Quantitative relationship between the streaming rate of microparticles to changes in acoustic frequencies and voltages. The blue area indicates the optimal parameters for successful injection. Data are graphed as the mean value ± SD (N = 10). h Microparticle embedding mechanisms: As the surface acoustic wave (SAW) frequencies increase, there is a shift in the embedding mechanisms. Droplet-initiated encapsulation mode (low frequency): The droplet is deformed by the traveling wave and the microparticle migrates to the leading edge (#1). Then the microparticle is pulled towards the trailing edge and encapsulated by the droplet (#2). Microparticle-initiated injection mode (high frequency): The microparticle is pushed (#1) and vibrates due to the balance between \({F}_{p}\) and \({F}_{s}\) (#2). Then the microparticle passes through the water-oil interface (#3). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

When the wavelength is much larger than the target particle, scattering phenomena are very weak. There is minimal reflection of the wave on the target surface, resulting in a negligible influence of the target on the wave field. Generally, the radiation force can be derived from the Gor’kov potential field \(F=-\nabla U\), assuming \(k{R}_{t}\ll 1\), represents the radius of the target on which the radiation force acts. In this case, \(k{R}_{{droplet}} < 1\) but close to 1, where \(k\) is the wavenumber and \(R\) is the target radius. This condition deviates from the Gor’kov assumption. Therefore, at a low SAW frequency (~10 MHz), it is difficult to excite the lowest-order mode (simplest deformation pattern) of the droplet, causing the acoustic waves to exert a stronger influence on the larger droplets compared to the smaller microparticles. Additionally, when the wavelength of the acoustic wave is much larger than the size of the 15 μm microparticle, the acoustic wave is almost unaffected by the microparticle and can propagate around it, similar to how sound waves bypass small obstacles. In contrast, the acoustic radiation force dominantly acts on the droplet, which has a diameter of ~100 μm. Traveling waves with wavelengths comparable to the diameter of the droplets push the droplets, causing deformation (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 6). The greater the degree of deformation, the lower the tension at the water-oil interface, resulting in a stronger pulling force on microparticles attached to the surface. By measuring the eccentricity (\(e\)) of the deformed droplet, we can determine the range of acoustic wave frequencies that cause the most severe droplet deformation (Fig. 2c). Through simulation and experimental confirmation, successful microparticle embedding normally happens when \(e\ge 0.6\).

As the frequency increases, any scattering phenomena becomes significantly stronger. When the SAW frequency exceeds 100 MHz, meaning that \(k{R}_{{droplet}}\ge 1\), and the Gor’kov assumption no longer applies. In this case, the mode shape of the droplet is easily excited which results in less effective propulsion of the droplet (Fig. 2b, c). However, due to \(k{R}_{{microsphere}}\ll 1\), the acoustic waves exert a strong pushing force on the microparticles (Fig. 2d–g). At an acoustic frequency of 150 MHz, the wavelengths (~12.8 μm on LiNbO3)44 are comparable to the size of the target microparticles (Fig. 2d), and approximately eight cycles of traveling waves simultaneously act on the droplet. As examined by the vibrometer (Fig. 2d), the 150 MHz transducer generates sufficient acoustic pressure, with the vibration peak occurring solely at the focused area, to generate vortices along the y-axis and centered around the focal area. To further confirm that higher-frequency SAW generates stronger vortices compared to lower-frequency SAW, we specifically used smaller-sized particles in this verification experiment to better follow and visualize the vortex patterns and flow velocities. However, in subsequent embedding experiments, we consistently used uniformly sized 15 μm particles. The trajectory of 1 μm fluorescent particles confirmed the presence of strong vortices generated by the 150 MHz acoustic transducer (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Video 1). To directly compare the impact of the acoustic force on microparticles at different actuation frequencies and applied voltages, we tracked and calculated the average velocity of 5 μm particles (Fig. 2f). The results confirm our original hypothesis that high-frequency transducers have a more significant effect on microparticles by exerting a stronger force and accelerating the microparticles more in the liquid (Fig. 2g, Supplementary Fig. 7).

Combined with the droplet deformation measurement in Fig. 2c, we conclude that the acoustic waves exert a strong influence on either the microparticles or the droplets. This influence can be selected by changing the acoustic wave frequencies to better align with the size of either the droplet (typically ~ 15 μm) or the microparticles (typically ~ 100 μm). The relationship between the wavelength of the acoustic waves and the size of the target reveals that as the frequency increases, the effect of the acoustic waves shifts from predominantly affecting the droplets to predominantly affecting the microparticles.

Modeling microparticle embedding at select acoustic wave frequencies in FAME

Based on force analysis, numerical simulations, and the characteristics of acoustic forces at different frequencies (Supplementary Note 1), we have developed an analytical model for the operating mechanism behind our acoustofluidic FAME system. This model describes two main microparticle embedding modes (Fig. 2h): droplet-initiated encapsulation mode driven by low-frequency (~10 MHz) SAW pulses or microparticle-initiated injection mode driven by high-frequency (~150 MHz) SAW pulses.

As shown in Fig. 3a, we estimated the components of the reaction force applied to the microparticle, with the input acoustic pressure assumed to be \({p}_{{in}}={p}_{0}\sin ({ky}-\omega t)\). The force applied to the microparticle can be obtained by integrating over its perimeter

Where p0, k, ω, Ω are the acoustic pressure, wavenumber, applied frequency, and boundary of the microparticle, respectively. We estimated the vertical component of the capillary force pulling the microparticle along the y-axis (Fig. 3a). Here, the net capillary force (Fs) is achieved by performing an integration of the surface tension vectors around the contact lines of the solid-liquid interface. The contact line forms at the solid-liquid interface. In addition, we presume that the contact angle remains constant around the contact line. Owing to the symmetry with respect to the xy plane, the force components along the z-axis counteract each other and cancel out, with only the components parallel to the xy plane remaining. Then the y component of the capillary force is obtained by taking the projection of \({F}_{s}\) along y-axis:

a Illustration of the mechanism of the droplet-initiated encapsulation mode. (i) In step 1, the microparticle (orange) is pushed by the applied acoustic pressure (\({p}_{{in}}\)), with the related force: \({F}_{p}\). The microparticle moves toward the droplet (sky blue) and causes a collision over a small surface area. In step 2, the capillary force (\({F}_{s}\)) along the x axis constrains the microparticle to roll along the surface of the droplet. In step 3, after being trapped at the trailing edge of the droplet, the microparticle is prevented from separating by \({F}_{s}\). The deformed droplet exerts a drag force, \({F}_{w}\), pulling the microparticle inside. (ii) Numerical simulations of the acoustic pressure distribution and distributions of acoustic forces (red arrows) applied on the particles for every step above. b Mechanism for the microparticle-initiated injection mode. (i) Step 1 is similar to the first step of the droplet-initiated encapsulation mode. In step 2, \({F}_{p}\) pushes the microparticle further to counter Fs, which maintains surface continuity. In step 3, when the \({F}_{p}\) >> \({F}_{s}\) (y axis component), the microparticle is pushed to overcome the resistance due to the capillary force and breaks into the droplet. (ii) Numerical simulations of the acoustic pressure distribution and distributions of acoustic forces applied on the particles for every step above. c Image captured sequence of the droplet-initiated encapsulation process. At 72 ms, the microparticle is encapsulated by the droplet. Scale bar: 25 μm. d, Image captured sequence of the microparticle-initiated injection process. The microparticle accelerates in the carrier fluid, punches into, and vibrates on the droplet surface for ~50 ms. At 52 ms, the microparticle is injected into the droplet. Scale bar: 25 μm.

With

Where πR refers to the diameter of the contact line, \(\alpha\) refers to the angle between the plane of solid particle and the contact line on the droplet, and \(\gamma\) refers to the surface tension magnitude. \(\beta\) is the angle between the surface tension vector and the y-axis. At a low frequency, \({F}_{p}\) is balanced with \({F}_{{sy}}\). This balance prevents the microparticle from being pushed into the droplet along this leading contact point. Instead, \({F}_{{sx}}\) guides the microparticle to roll along the surface of the droplet (Fig. 3a, step 2). Eventually, the microparticle gets trapped against the trailing edge of the droplet. At this point, the pushing force on the microparticle becomes a pulling force, and \({F}_{s}\) resists the microparticle’s separation from the droplet (Fig. 3a, step 3). This process is named as the “droplet-initiated encapsulation mode”.

Similar to the droplet-initiated encapsulation mode, we estimate the component of the reaction force applied to the microparticle using a similar approach as in Eqn. [1], for the high frequency case (Fig. 3b). After being pushed by the acoustic radiation force into contact with the droplet (Fig. 3b, step 1), \({F}_{{sy}}\) arises, which prevents the microparticle from entering the droplet. The capillary force is a contact force related to material properties. As the microparticle is pushed, the angle (β) between the surface tension vector and the y-axis decreases (Fig. 3b, step 2). At high frequencies, the acoustic radiation force on the microparticle is much larger than at low frequencies. This results in \({F}_{p}{ > F}_{{sy}}\), which leads to microparticle embedding (Fig. 3b, step 3).

Testing the low-frequency domain of FAME for droplet-initiated encapsulation of a microparticle

Droplet-initiated encapsulation of microparticles occurs in the low-frequency acoustic wave case (~10 MHz). The corresponding wavelength on the LiNbO3 is about 397.9 μm (in water it is 148 μm and in FC-40 it is 68.4 μm)44,45, which is much larger than the diameter of the microparticle (~15 μm) and comparable to the size of droplet (~100 μm). A 15 μm diameter microparticle (polystyrene bead, PS07N, Bangs Laboratories, Inc., USA) embedding assay is conducted to validate the droplet-initiated encapsulation mode (Supplementary Video 2). As shown in Fig. 3c, when the wavelength is much larger than the microparticle and comparable to the droplet diameter, the input acoustic pressure deforms the droplet into a low-order mode shape, partially distorting it. As the droplet attempts to restore its equilibrium spherical shape, it encapsulates the microparticle in the process. As described, the microparticle will be pushed by the acoustic radiation force toward the surface of the droplet in the first 44 ms (Fig. 3c, step 1), leading to a collision over a small surface area. The target microsphere then migrates along the droplet surface under the influence of \({F}_{p}\) within the following 26 ms (Fig. 3c, step 2). Subsequently, at 72 ms, the droplet’s tendency to restore to its original shape generates a pulling force. This causes the microparticle to be fully encapsulated by the droplet (Fig. 3c, step 3).

Testing the high-frequency domain of FAME for microparticle-initiated injection

At high frequencies (100–150 MHz), the droplet acts as a transport medium for the incoming wave, inducing high-order modes within it. The acoustic radiation force on the droplet becomes significantly weaker than the drag force. This makes droplet movement difficult. In contrast, as indicated by the theory (Supplementary Note 2)46, high-frequency SAWs in the range of 100–150 MHz have wavelengths comparable to the diameter of 15 μm microbeads. This similarity in scale induces strong nonlinear variations in the acoustic radiation force on the microparticles as the input frequency changes (Supplementary Fig. 8). This nonlinear response of the microparticles to the driving frequency generates pronounced resonance effects at specific actuation frequencies, producing a substantial acoustic radiation force on the microbeads. The applied acoustic pressure effectively pushes the small microparticles forward while maintaining the stability of the droplet (Fig. 3d). As the input power increases, the pushing force eventually overcomes the tension at the interface. This allows the microparticle to penetrate the water-oil interface and effectively be injected into the droplet. An experiment is recorded to validate this mechanism (Supplementary Video 3). As shown in Fig. 3d, a 15 μm polystyrene bead suspended in FC-40 is accelerated by 150 MHz traveling waves and attaches to the surface of the droplet within 10 ms (Fig. 3d, step 1). The bead vibrates on the droplet surface, due to minor instabilities in the pushing force (Fig. 3d, step 2). Approximately 52 ms later, the bead breaks through the water-oil interface and is injected into the aqueous droplet (Fig. 3d, step 3). The experimental results successfully confirmed the feasibility of this acoustofluidic microparticle embedding scheme. The high-speed microscope images in Fig. 3 support the two analytical models.

In addition to the low and high-frequency cases, acoustic waves with frequencies in the middle range (50–90 MHz) were also tested. However, in this intermediate range, the wavelength of input SAW neither aligns with the droplet’s size nor approaches the particle’s size. As a result, both targets are pushed in the same direction and moved strongly by the acoustic radiation force (Supplementary Fig. 9), leading to a failure to embed the microparticle into the droplet (Fig. 2h, Supplementary Video 4).

Post-embedding manipulation of microparticles and droplets via FAME

The mechanism also infers that acoustic waves have the capability for dynamic microparticle and droplet manipulation after embedding12,17,47,48,49. Experimentally, we verified that droplets will rapidly respond to acoustic waves (Supplementary Fig. 10a). The droplets start to move and deform within 3 ms of the acoustic wave initiation. Importantly, this response persists even after microparticles have been embedded into the droplets. In addition to the nanoliter droplet, the acoustofluidic FAME platform can manipulate the microparticles post-embedding as well. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 10b, fluorescent microparticles are aggregated by acoustic waves within the droplet (Supplementary Video 5). This demonstrates the capability for dynamic microparticle manipulation within droplets via acoustics, after FAME embedding.

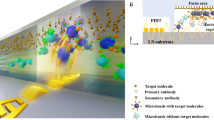

Dynamic manipulation of functional hydrogel microspheres via FAME

Hydrogel microspheres or capsules play crucial roles in drug delivery, release, and capture within droplet microfluidic systems25,27,50,51,52. Next, the FAME system will be used to demonstrate the adjustment of microdroplet environments by embedding hydrogel microspheres into them. Different functional hydrogels can be embedded into droplets to achieve various functions (Fig. 4a). To demonstrate a molecular release function, an agarose hydrogel microsphere is used. Hydrogel materials like agarose, which form gels through physical entanglement, can be easily disassembled by an external force such as heat and pressure, thus releasing any trapped molecules53,54,55. After embedding agarose microspheres into the droplet, sustained acoustic pulses are continued to be applied to the target droplet. As shown in Fig. 4b, the agarose microspheres exhibited the expected continuous swelling and breakdown within the droplet (Supplementary Video 6). After continuously applying acoustic wave pulses with a 500 ms duration, 1/2 duty cycle for ~13 cycles, the agarose microsphere became invisible. Furthermore, we also measured the diameter changes of agarose microspheres before and after embedding (Fig. 4c). After being embedded into the droplet, the size of the agarose hydrogel generally increased by 0.5–1.5 times and remained stable (Supplementary Fig. 11). Then acoustic wave pulses were continuously applied to the droplets containing the agarose microspheres (Fig. 4d). After ~10 cycles, the sizes of the microspheres begin to change dramatically. Following an additional 3–5 cycles, the microspheres have typically expanded to more than 2.5 times their original sizes and become invisible, making further measurement difficult. To validate the breakdown of the agarose microspheres, we first encapsulate 1 μm green-fluorescent particles within the agarose microsphere. After being embedded into the droplet and disassembled by acoustic wave stimulation, the fluorescent particles were successfully released and spread out within the droplet (Fig. 4e). To further verify the molecular release capability of agarose, we encapsulate 0.2 mg/mL FITC within agarose microspheres. As shown in Fig. 4f, after the microsphere is embedded into the droplet and broken down by acoustic pressure, the fluorescence intensity of the droplets increases by ~0.57-fold. The fluorescence intensity of the agarose microsphere before embedding is detected as well (Supplementary Fig. 12), which is about 5.8 times higher than the background intensity of the carrier fluid. This demonstrates that agarose hardly releases FITC molecules into the oil-phase carrier fluid.

a Schematic showing the dynamic embedding process for two types of hydrogel microspheres. On the left side, the FITC encapsulated agarose microsphere is embedded into the droplet to achieve molecule release and, on the right side, the stereocomplexed PEG-PLA microsphere is used for FITC capture. b Microscope image sequence capturing the process of an agarose microsphere being embedded into a droplet, followed by its swelling and breakdown induced by acoustic waves. Scale bar: 25 μm. c Comparison of size changes in agarose microspheres, for three different microsphere sizes, before and after being embedded. d The growth of agarose microspheres size within droplets as the number of cycles of acoustic wave pulses increases. e Images displaying the release of fluorescent microparticles within the droplet following the embedding of agarose microspheres into the droplet. Scale bar: 25 μm. f Comparison of fluorescence intensities of droplets before and after embedding with FITC carried agarose microspheres. The center line indicates the median, the edges of the box represent the first and third quartiles, and the whiskers extend to span a 1.5 interquartile range from the edges, and the square points refer to the mean value (N = 20). g Bright and fluorescent images showing the fluorescence intensities of the droplet and stereocomplexed PEG-PLA microsphere before and after embedding (0.2 mg/mL FITC in the original droplet). Scale bar: 25 μm. h Measurement of fluorescence intensities for droplets before embedding, droplets without embedding, droplets with microspheres embedded, and microspheres that have been embedded into the droplets. Unless otherwise noted, all data are graphed as the mean value ± SD (N = 10). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

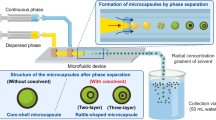

In addition, we utilized stereocomplexed PEG-PLA56, a hydrogel material, to demonstrate molecular capture within a droplet (Supplementary Note 3, Supplementary Fig. 13). Stereocomplexed PEG-PLA microspheres are formed by extruding droplets of gel solution dissolved in ethyl acetate through oil, after which the gel solution droplets solidify into microspheres. To engage in biologically relevant research, these microspheres need to transition to an aqueous medium. This is an ideal application for the FAME system. The mesh-like structure of stereocomplexed PEG-PLA microspheres endows them with excellent water absorption and molecular adsorption capabilities. A validation test is conducted to evaluate the molecular capture capability of stereocomplexed PEG-PLA microspheres (Fig. 4g). The fluorescence intensity of the 0.2 mg/mL FITC solution droplets are detected before embedding them into droplets (control group). The fluorescence intensity in blank droplets (without any microspheres) and in microsphere-loaded droplets (liquid part and hydrogel part) are measured and compared against the control group. As shown in Fig. 4h, after being embedded into the droplet, the fluorescence intensity of the microspheres is 2.2 times higher that of the droplet solution, while the fluorescence intensity of the droplet liquid part decreases by ~10%, indicating that FITC molecules were captured by the stereocomplexed PEG-PLA microsphere. We compare the molecular capture capabilities of stereocomplexed PEG-PLA with alginate and agarose (Supplementary Fig. 14), proving the powerful FITC capture ability of stereocomplexed PEG-PLA microspheres.

The integration of stereocomplexed PEG-PLA and agarose with our acoustofluidic FAME platform enables different functions such as solid drug delivery or molecular capture. The system offers a dynamic and precise hydrogel microsphere embedding and manipulation solution, paving the way for future on-chip drug delivery, synthetic biology, and bio-chemical reaction studies.

Discussion

Our acoustofluidic FAME platform significantly pushes forward the development of droplet microfluidic manipulation technologies. It provides a powerful tool for the active manipulation of microparticles, droplets, and the resulting microenvironment. This advancement enriches the possibilities of droplet microfluidics, providing a multi-functional analytical tool for in-depth scientific research5,7,10,57. FAME overcomes the limitations imposed by the water-oil interface barrier by using short traveling acoustic wave pulses to manipulate the multi-phase system and enable cross-phase microsphere embedding. The proposed platform is a practical demonstration of solid microparticles transitioning from a continuous oil phase (e.g., the carrier fluid) into a dispersed liquid droplet. Furthermore, supported by experimental results, we developed a comprehensive model that elucidates the mechanism of microparticle embedding into droplets across various frequency ranges. With this understanding of the acoustofluidic FAME system’s operating principles, we enable rapid and direct microparticle embedding as well as dynamic, real-time adjustments of the droplet microenvironment. This, in turn, facilitates the study of dynamic processes and allows for the initiation of reactions on demand.

Previous methods for manipulating droplets, such as pre-encapsulation of microcapsules with conditionally triggered degradation or active droplet injection using high-voltage electric pulses or acoustics, have shown promise but come with inherent limitations13,17,29,58. Droplet injection methods enable dynamic adjustment of the droplet microenvironment through the exchange of liquid reagents to be injected5,9. However, conventional droplet injection technologies are hindered by their limited ability to handle solid targets, potential cross-contamination between reagents and droplets, restricted multi-phase manipulation capability, and difficulties in achieving real-time monitoring within flow systems6,59,60,61. Our system overcomes these limitations by directly embedding microparticles into aqueous droplets, thereby eliminating the need for complex preprocessing steps. It prevents potential contamination by isolating reagents into distinct hydrogel microspheres and enables dynamic control of both droplets and microspheres pre- and post-embedding60. This capability enables controlled multi-phase manipulation and rapid delivery of active agents, such as drugs or biochemical reagents, into confined environments. It promises effective real-time monitoring of time-sensitive physical or chemical reactions. This innovation in multi-phase manipulation also paves the way for further artificial cell research. Expanding on the water-in-oil droplet artificial cell system12,62,63,64, our approach enables the construction and manipulation of more complex artificial cells, such as water droplets with solid particles in oil. Our system provides an efficient tool for studying cellular multi-phase interactions and related phenomena.

Despite its advantages, there are still several drawbacks to the current FAME system. One notable challenge lies in enhancing the precision and efficiency of microparticle embedding (Supplementary Note 4, Supplementary Fig. 15). Further quantitative measurements are needed to accurately evaluate and analyze the acoustic pressure, interfacial tension, and drag and push force required for successful embedding of microparticles into droplets. Another aspect for future development is to optimize the microfluidic design for high-throughput assays and selective microparticle embedding for drug delivery or synthetic biology applications. Future improvements should focus on enhancing the system’s throughput, precision, and scalability. This includes optimizing the microfluidic channel structure by introducing an array of microscale traps for precise positioning and constraint of nanoliter droplets and target microparticles65,66. Such an array design would ensure that each droplet aligns and corresponds to a target microparticle, enabling highly scalable manipulation. In parallel to this improvement, optimizing the transducer design is crucial, with future research focusing on focused IDT array integration or broadening to facilitate the simultaneous manipulation and embedding of multiple microparticle-droplet combinations67,68. Additionally, improvements in embedding and washing different types of microparticles, along with other system enhancements, will be essential to make the platform suitable for practical applications. Further optimization and improvement can unlock the full potential of our acoustofluidic FAME technology for broader adoption and practical applications in biomedical engineering and synthetic biology69,70,71,72.

In summary, the acoustofluidic FAME system offers dynamic, non-invasive handling of nanoliter droplets, embedding solid microparticles from a fluorinated oil carrier fluid into the target droplet. A practical acoustofluidic-based method for controlling solid-liquid droplet interactions, along with an analytical model of the operating mechanism in different frequency regimes, has been presented. Demonstrations with agarose hydrogels and PEG-PLA solid microparticles show the potential for constructing and manipulating more sophisticated artificial cells that closely resemble real cell systems, conducting complex and multi-step chemical or biochemical reactions, and initiating and monitoring rapid chemical reactions with precise temporal control.

Methods

Design of the acoustofluidic FAME system

The acoustofluidic FAME system aims to validate the two theories for high-frequency and low-frequency microparticle embedding modes. To achieve this, a series of focused interdigital transducers were designed with resonant frequencies of 10 MHz, 30 MHz, 50 MHz, 70 MHz, 100 MHz, and 150 MHz. The focus angle of all transducers is set to 20° to achieve the highest energy concentration efficiency, as determined in previous studies20,73 (Supplementary Note 5, Supplementary Table 1). To maintain consistency, the distance between the transducer and the microchannel is set to ~500 μm. Another critical part of the system is the microfluidic channel that loads and traps droplets (Fig. 1a, right). The microchannel consists of two main structures: at the bottom is a fully connected channel with a height of 80 μm and a width of 400 μm. When preparing droplets, loading droplets with a flow of >1 μL/s causes them to move through the bottom channel. At the top of the channel, several independent round holes are concave upwards with a diameter of 100 μm and a depth of 40 μm (Fig. 1a). When the droplet flow rate decreases, droplets slow down and gradually float because the density of water droplets (~1 g/cm³) is lighter than FC-40 oil (1.85 g/cm³, 3 M™ Fluorinert™ Electronic Liquid FC-40 Materials, 3 M™, USA) (Supplementary Table 1). The round holes temporarily trap the droplets, restrict them within a limited range, and facilitate acoustic wave powered embedding. The center of each hole is aligned with the channel centerline, ensuring that the focal point of the interdigital transducer falls on the droplet.

Device fabrication and operation

The FAME system comprises a piezoelectric substrate and a channel made from polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, Sylgard 184 Elastomer Kit, Dow Corning Corp, USA). A 500 μm thick, 4-inch Y-128° cut lithium niobate (LiNbO3, Precision Micro-Optics, USA) wafer serves as the piezoelectric substrate. Standard photolithography was used to pattern the focused interdigital transducers on the LiNbO3 wafer. Subsequently, a layer of Cr (5 nm) followed by a layer of Au (200 nm) was plated onto the LiNbO3, where the pattern had been etched. For the fabrication of the PDMS microfluidic channel, an inverted template was created using an SU-8 mold (University Wafer Inc., USA). The microfluidic part of the system consists of a microchannel with a height of 80 μm and a width of 400 μm at the bottom. At the top of the channel, several round holes with a diameter of 100 μm are concave upwards with a depth of 40 μm. This design necessitates two rounds of standard soft lithography. After fabricating both the LiNbO3 substrate and the PDMS microchannel, the components undergo 6 min of surface plasma treatment to achieve a firm bond between them.

Droplet loading and release

The microchannel consists of a mostly flat chamber with a height of 80 μm and a width of 400 μm at the bottom (Fig. 1a, right, Supplementary Fig. 16(i)). The roof of the chamber features recessed circular holes that are 100 μm in diameter, which closely matches the droplet size, and a depth of 40 μm, which is smaller than the droplet radius. Since the density of the droplets (~1 g/mL) is lower than that of FC-40 (1.85 g/mL), droplets naturally float to the upper layer of the channel when introduced slowly using a static pressure pump (~1 μL/s)20. Upon reaching a recessed circular hole, buoyancy lifts the droplet upward, securely trapping it within the hole (Supplementary Fig. 16(ii)). Because the hole’s diameter closely matches that of a single droplet, each hole accommodates only one droplet at a time (Supplementary Fig. 16(iii)). After embedding, the chip is flipped over, and FC-40 is rapidly flowed through to dislodge the droplets using hydrodynamic forces (Supplementary Fig. 16(iv)). This process is then repeated to reload a new droplet for the next embedding cycle.

Preparation of droplets

Water-in-oil droplets are generated by a microfluidic generator. The droplet generator features an inner inlet loaded with water or an aqueous solution. The outer inlet is filled with fluorinated oil (FC-40). FC-40 flows from the peripheral channel around the inner inlet to the cross-junction of the channel, squeezing the water flow and forming water droplets. To generate droplets consistently, two syringes are pumped by a syringe pump (neMESYS 290N, Germany) at flow rates of 4 μL/min for water and 30 μL/min for FC-40, respectively. For generating fluorescent droplets, a 0.2 mg/mL FITC solution (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) replaces water as the dispersed phase.

Preparation of hydrogel microspheres

Hydrogel microspheres were fabricated via a three-phase microfluidic method (Supplementary Fig. 13)56. The dispersed phase consisted of a solution of PEG-PLLA/PrPDLA (2:1 molar ratio) dissolved in ethyl acetate (10 wt%) (Supplementary Note 3). Continuous phase 1 was composed of Span80 in light mineral oil (3 vol%). Continuous phase 2 was composed of 9 wt% poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) in deionized water (Millipore Sigma, USA). The dispersed phase was loaded and dispensed using an analytical glass syringe (500 μL, Hamilton, USA). The continuous phases were loaded and dispensed in plastic syringes (5 mL, BD, USA). Polyethylene tubing (0.023 in. ID × 0.038 in. OD, PE-50, Warner Instruments, USA) was used to deliver all phases to and from the microfluidic chip. Flow rates were controlled precisely by syringe pumps (Pump33DDS, Harvard Apparatus, USA) which were set to deliver 0.9 μL/min for the dispersed phase, 23.0 μL/min for continuous phase 1, and 32.0 μL/min for continuous phase 2. The flow of each phase was started in the following order: continuous phase 1, continuous phase 2, and dispersed phase. Droplet formation was monitored in real time using a BZ-X700 series digital fluorescence microscope (Keyence, Itasca, IL). All three phases with droplets exited the device via the outlet tubing which was submerged in a vial filled with deionized water to induce gelation (Supplementary Fig. 13a). The hydrogel microspheres were transferred to a centrifuge tube (15 mL) and centrifuged (800 × g) for 5 min. The water and oil layers were aspirated, and the tube was refilled with DI water then vortexed. This process was repeated 5× to remove organics or impurities from the fabrication process. Microspheres were then filtered through 40 µm cell strainers (PluriSelect, El Cajon, CA), lyophilized, and resuspended in FC-40 (Supplementary Fig. 13b).

The generation of agarose microspheres follows a similar process. A 10% agarose solution (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was melted at 65 °C and loaded into the dispersed phase inlet. Continuous phase 1 consisted of 1% 008-FluoroSurfactant FC-40, while continuous phase 2 was blocked. The set up of two phases remained the same. After forming agarose droplets using the same microfluidic method, the droplets gelled into microspheres as the temperature decreased to 20 °C.

Electronics

The focused interdigital transducer is powered by a pulsed AC signal from a function generator (AFG3102C, Tektronix, USA) and amplified by an amplifier (25A250A, Amplifier Research, USA). During the embedding process, the signal pulse is set to 100 ms. The input voltage for the 10 MHz transducer is ~60 Vpp (peak-to-peak), while for the 150 MHz transducer, around 30 Vpp is suitable for high-frequency microparticle-initiated injection. When swelling and enforcing the disassembly of agarose microspheres, a cyclic signal pulse with a 250 ms pulse and a 250 ms interval replaces the single pulse to provide longer and stronger acoustic waves manipulation.

Microscopy

In the experiments, a Nikon inverted microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti, Nikon Instruments Inc., Japan) is used for capturing microscopy images, recording videos, and collecting fluorescent images. High-speed videos (500–4800 fps) are recorded to analyze the microparticle embedding process using a high-speed camera (Mini AX 200, FastCAM Inc., USA). For fluorescence assays, a laser with an optical filter (49002 ET-EGFP, Chroma Technology, USA) is used to excite green fluorescence particles (1 μm, 5 μm, Magsphere Inc., USA) and FITC molecules.

Eccentricity measurement

Droplet deformation videos are recorded using a high-speed camera. The videos are then cropped to focus solely on the droplets using ImageJ software. Then, those videos are imported into a custom-written MATLAB program (R2017b, MathWorks, USA) to calculate the eccentricity of the deformed droplets using MATLAB’s built-in eccentricity algorithm.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test by GraphPad Prism 9.0. The data were presented as a mean ± standard deviation (SD). Confidence levels of *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 were selected as the threshold values.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data and code supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and the supplementary materials. Further information is available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The acoustic wave simulations were performed with commercial software COMSOL Multiphysics 6.0. No special codes were developed for this study. The computation details are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Nan, L., Zhang, H., Weitz, D. A. & Shum, H. C. Development and future of droplet microfluidics. Lab Chip 24, 1135–1153 (2024).

Hu, Z. et al. Understanding and utilizing droplet impact on superhydrophobic surfaces: phenomena, mechanisms, regulations, applications, and beyond. Adv. Mater. 36, 2310177 (2024).

Lathia, R. et al. Advances in microscale droplet generation and manipulation. Langmuir 39, 2461–2482 (2023).

Shapiro, J. M., Drinkwater, B. W., Perriman, A. W. & Fraser, M. Sonolithography: in-air ultrasonic particulate and droplet manipulation for multiscale surface patterning. Adv. Mater. Technol. 6, 2000689 (2021).

Ng, E. X., Miller, M. A., Jing, T., Lauffenburger, D. A. & Chen, C.-H. Low-volume multiplexed proteolytic activity assay and inhibitor analysis through a pico-injector array. Lab Chip 15, 1153–1159 (2015).

Mutafopulos, K., Lu, P. J., Garry, R., Spink, P. & Weitz, D. A. Selective cell encapsulation, lysis, pico-injection and size-controlled droplet generation using traveling surface acoustic waves in a microfluidic device. Lab a Chip 20, 3914–3921 (2020).

Huang, S. et al. Dynamic control and quantification of bacterial population dynamics in droplets. Biomaterials 61, 239–245 (2015).

Sesen, M., Fakhfouri, A. & Neild, A. Coalescence of surfactant-stabilized adjacent droplets using surface acoustic waves. Anal. Chem. 91, 7538–7545 (2019).

Jia, Y. et al. Sequential coalescence enabled two-step microreactions in triple-core double-emulsion droplets triggered by an electric field. Small 13, 1702188 (2017).

Zhang, J. et al. One-step fabrication of supramolecular microcapsules from microfluidic droplets. Science 335, 690–694 (2012).

Park, K.-S., Kim, C., Nam, J.-O., Kang, S.-M. & Lee, C.-S. Synthesis and characterization of thermosensitive gelatin hydrogel microspheres in a microfluidic system. Macromol. Res. 24, 529–536 (2016).

Li, J. et al. Building programmable multicompartment artificial cells incorporating remotely activated protein channels using microfluidics and acoustic levitation. Nat. Commun. 13, 4125 (2022).

De Lora, J. A. et al. Evaluation of acoustophoretic and dielectrophoretic forces for droplet injection in droplet-based microfluidic devices. ACS Omega 9, 16097–16105 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Mao, A., Mooney, D. J., & Weitz, D. A. Synthesis of cell-laden alginate microgels with tunable compositions based on microfluidic pico-injection technique. bioRxiv, 2022.2001.2009.475570 (2022).

Griffin, D. R., Weaver, W. M., Scumpia, P. O., Di Carlo, D. & Segura, T. Accelerated wound healing by injectable microporous gel scaffolds assembled from annealed building blocks. Nat. Mater. 14, 737–744 (2015).

Wei, C. et al. Rapid microfluidic mixing method based on droplet rotation due to PDMS deformation. Micromachines 12, 901 (2021).

Zhang, S. P. et al. Digital acoustofluidics enables contactless and programmable liquid handling. Nat. Commun. 9, 2928 (2018).

Fan, S.-K., Huang, P.-W., Wang, T.-T. & Peng, Y.-H. Cross-scale electric manipulations of cells and droplets by frequency-modulated dielectrophoresis and electrowetting. Lab Chip 8, 1325–1331 (2008).

Kumar, A., Chuang, H.-S. & Wereley, S. T. Dynamic manipulation by light and electric fields: micrometer particles to microliter droplets. Langmuir 26, 7656–7660 (2010).

Zhong, R. et al. Cellular immunity analysis by a modular acoustofluidic platform: CIAMAP. Sci. Adv. 9, eadj9964 (2023).

De Jonghe, J. et al. spinDrop: a droplet microfluidic platform to maximise single-cell sequencing information content. Nat. Commun. 14, 4788 (2023).

Nightingale, A. M., Phillips, T. W., Bannock, J. H. & de Mello, J. C. Controlled multistep synthesis in a three-phase droplet reactor. Nat. Commun. 5, 3777 (2014).

Xie, Y. et al. Exploring bubble oscillation and mass transfer enhancement in acoustic-assisted liquid-liquid extraction with a microfluidic device. Sci. Rep. 5, 12572 (2015).

Collignon, S., Friend, J. & Yeo, L. Planar microfluidic drop splitting and merging. Lab Chip 15, 1942–1951 (2015).

Zhao, Z. et al. Capturing magnesium ions via microfluidic hydrogel microspheres for promoting cancellous bone regeneration. ACS Nano 15, 13041–13054 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Elastic porous microspheres/extracellular matrix hydrogel injectable composites releasing dual bio-factors enable tissue regeneration. Nat. Commun. 15, 1377 (2024).

Kim, J. et al. On-demand delivery of therapeutic extracellular vesicles by encapsulating in monodispersed photodegradable hydrogel microparticles using a droplet microfluidic device. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 394, 134396 (2023).

Zhang, T. et al. One-step generation and purification of cell-encapsulated hydrogel microsphere with an easily assembled microfluidic device. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 9, 816089 (2022).

Lee, T. Y. et al. Microfluidic production of biodegradable microcapsules for sustained release of hydrophilic actives. Small 13, 1700646 (2017).

Roosa, C. et al. Microfluidic synthesis of microgel building blocks for microporous annealed particle scaffold. J. Vis. Exp. https://doi.org/10.3791/64119, e64119 (2022).

Guo, X. et al. Controllable cell deformation using acoustic streaming for membrane permeability modulation. Adv. Sci. 8, 2002489 (2021).

Zhang, P. et al. Acoustic streaming vortices enable contactless, digital control of droplets. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba0606 (2020).

Mazutis, L. & Griffiths, A. D. Selective droplet coalescence using microfluidic systems. Lab Chip 12, 1800–1806 (2012).

Islamova, A. G., Kerimbekova, S. A., Shlegel, N. E. & Strizhak, P. A. Droplet-droplet, droplet-particle, and droplet-substrate collision behavior. Powder Technol. 403, 117371 (2022).

Ahmed, D. et al. Rotational manipulation of single cells and organisms using acoustic waves. Nat. Commun. 7, 11085 (2016).

Jung, J. H., Destgeer, G., Ha, B., Park, J. & Sung, H. J. On-demand droplet splitting using surface acoustic waves. Lab Chip 16, 3235–3243 (2016).

Cheung, Y. N., Nguyen, N. T. & Wong, T. N. Droplet manipulation in a microfluidic chamber with acoustic radiation pressure and acoustic streaming. Soft Matter 10, 8122–8132 (2014).

Baudoin, M., Brunet, P., Bou Matar, O. & Herth, E. Low power sessile droplets actuation via modulated surface acoustic waves. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 154102 (2012).

Fan, X.-D. & Zhang, L. Phase shift approach for engineering desired radiation force: acoustic pulling force example. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 150, 102–110 (2021).

Ozcelik, A. et al. Acoustic tweezers for the life sciences. Nat. Methods 15, 1021–1028 (2018).

Fakhfouri, A., Devendran, C., Ahmed, A., Soria, J. & Neild, A. The size dependant behaviour of particles driven by a travelling surface acoustic wave (TSAW). Lab Chip 18, 3926–3938 (2018).

Saeidi, D., Saghafian, M., Haghjooy Javanmard, S., Hammarström, B. & Wiklund, M. Acoustic dipole and monopole effects in solid particle interaction dynamics during acoustophoresis. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 145, 3311–3319 (2019).

Collins, D. J. et al. Acoustic tweezers via sub–time-of-flight regime surface acoustic waves. Sci. Adv. 2, e1600089 (2016).

Soluch, V. & Lysakowska, M. Surface acoustic waves on X-cut LiNbO/sub 3. IEEE Trans. Ultrason., Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 52, 145–147 (2005).

Eovino, B. E., Akhbari, S., & Lin, L. In Proc. IEEE 30th International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS) 1184–1187 (IEEE, 2017).

Ma, Z., Collins, D. J. & Ai, Y. Single-actuator bandpass microparticle filtration via traveling surface acoustic waves. Colloid Interface Sci. Commun. 16, 6–9 (2017).

Guo, F. et al. Controlling cell-cell interactions using surface acoustic waves. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 43–48 (2015).

Ao, Z. et al. Rapid profiling of tumor-immune interaction using acoustically assembled patient-derived cell clusters. Adv. Sci. 9, 2201478 (2022).

Yang, S. et al. Harmonic acoustics for dynamic and selective particle manipulation. Nat. Mater. 21, 540–546 (2022).

Zhu, Z. & Yang, C. J. Hydrogel droplet microfluidics for high-throughput single molecule/cell analysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 22–31 (2017).

Daly, A. C., Riley, L., Segura, T. & Burdick, J. A. Hydrogel microparticles for biomedical applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 20–43 (2020).

Liu, H. et al. A droplet microfluidic system to fabricate hybrid capsules enabling stem cell organoid engineering. Adv. Sci. 7, 1903739 (2020).

Lee, K. J. & Yun, S. I. Nanocomposite hydrogels based on agarose and diphenylalanine. Polymer 139, 86–97 (2018).

Li, D. S. et al. How hydrogel inclusions modulate the local mechanical response in early and fully formed post-infarcted myocardium. Acta Biomater. 114, 296–306 (2020).

Griffin, D. R. & Kasko, A. M. Photodegradable macromers and hydrogels for live cell encapsulation and release. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 13103–13107 (2012).

Tutoni, G. G. et al. Microfluidic assembly of degradable, stereocomplexed hydrogel microparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 14705–14714 (2024).

Kang, H. M. et al. Multiplexed droplet single-cell RNA-sequencing using natural genetic variation. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 89–94 (2018).

Deng, X. et al. Compound-droplet-pairs-filled hydrogel microfiber for electric-field-induced selective release. Small 15, 1903098 (2019).

Liu, L., Xiang, N. & Ni, Z. Droplet-based microreactor for the production of micro/nano-materials. Electrophoresis 41, 833–851 (2020).

Teh, S.-Y., Lin, R., Hung, L.-H. & Lee, A. P. Droplet microfluidics. Lab Chip 8, 198–220 (2008).

He, Z. et al. Composable microfluidic plates (cPlate): a simple and scalable fluid manipulation system for multiplexed enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Anal. Chem. 93, 1489–1497 (2021).

Fasciano, S. & Wang, S. Recent advances of droplet-based microfluidics for engineering artificial cells. SLAS Technol. 29, 100090 (2024).

Cheng, G., Han, X. & Zheng, S.-Y. Magnetically driven nanotransporter-assisted intracellular delivery and autonomous release of proteins. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 41096–41104 (2020).

Tian, L., Li, M., Patil, A. J., Drinkwater, B. W. & Mann, S. Artificial morphogen-mediated differentiation in synthetic protocells. Nat. Commun. 10, 3321 (2019).

Skelley, A. M., Kirak, O., Suh, H., Jaenisch, R. & Voldman, J. Microfluidic control of cell pairing and fusion. Nat. Methods 6, 147–152 (2009).

Dura, B. et al. Profiling lymphocyte interactions at the single-cell level by microfluidic cell pairing. Nat. Commun. 6, 5940 (2015).

Xia, J. et al. Acoustofluidic virus isolation via bessel beam excitation separation technology. ACS Nano 18, 22596–22607 (2024).

Zhao, S. et al. A disposable acoustofluidic chip for nano/microparticle separation using unidirectional acoustic transducers. Lab Chip 20, 1298–1308 (2020).

Rufo, J., Cai, F., Friend, J., Wiklund, M., Huang, T. J. Acoustofluidics for biomedical applications. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2, 30 (2022).

Rufo, J., Zhang, P., Zhong, R., Lee, L. P. & Huang, T. J. A sound approach to advancing healthcare systems: the future of biomedical acoustics. Nat. Commun. 13, 3459 (2022).

Yang, S. et al. Acoustic tweezers for high-throughput single-cell analysis. Nat. Protoc. 18, 2441–2458 (2023).

Wu, M. et al. Sound innovations for biofabrication and tissue engineering. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 10, 170 (2024).

Zhong, R. et al. Acoustofluidic Droplet Sorter Based on Single Phase Focused Transducers. Small 17, 2103848 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support from the National Institutes of Health (R01AG084098, R01GM141055, R01HD103727, R01GM143439, R01GM145960, R01GM144417, R44OD024963, R44AG063643, R44GM154514, and R44GM154515) and National Science Foundation (CMMI-2104295). Work by G.T. was supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant DGE 2139754. The authors are grateful to Dr. Luke P. Lee for editing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.Z. and X.X. led the experimental work. J.D.H.M., M.L.B., and T.J.H. provided guidance and contributed to the experimental design. R.Z., X.X., and G.T. developed the system concept and contributed to the device fabrication and improvements. M.L., K.Y., K.L., K.J., and Y.C. contributed to the experiment design and data analysis. R.Z. and X.X. contributed to data analysis and manuscript improvement. X.X. did the theoretical modeling and numerical simulation. G.T., K.Y., and K.J. contributed to data analysis. R.Z., X.X., G.T., J.D.H.M., and T.J.H. co-wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

T.J.H. has co-founded a start-up company, Ascent Bio-Nano Technologies Inc., to commercialize technologies involving acoustofluidics and acoustic tweezers. All remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Daniel Ahmed, Liangfei Tian, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhong, R., Xu, X., Tutoni, G. et al. An acoustofluidic embedding platform for rapid multiphase microparticle injection. Nat Commun 16, 4144 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59146-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59146-x

This article is cited by

-

Manipulation of microparticles using acoustic actuators: a review

Microfluidics and Nanofluidics (2026)