Abstract

As important components of global commons, environmental changes in polar regions are crucial to the local and global sustainability. However, they have received little attention in the current framework of sustainable development goals (SDGs). This study examines the impacts of climate change in polar regions, emphasizing the interconnectedness of these areas with other parts of the global system. Here we show that polar regions are a limiting factor in achieving global SDGs, similar to the “shortest stave” in Liebig’s barrel, primarily due to the teleconnection effects of climate tipping elements. Proactive actions should ensure polar regions aren’t left behind in achieving global SDGs. We proposed a specific SDG target and five indicators for the interconnected effect of the cryosphere on climate actions and incorporate considerations for Indigenous peoples in polar regions. With the right actions and strengthened global partnerships, polar regions can be pivotal for advancing global sustainable development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The principle of “leaving no one behind” necessitates the equitable and uniform implementation of United Nations (UN) sustainable development goals (SDGs). Globally, socioeconomic resources are predominantly allocated following the Pareto principle, where a minority of high-income economies defined by World Bank Country and Lending Groups1 control a substantial portion of the global wealth2. Efforts to achieve SDGs should therefore prioritize addressing this imbalance, guided by Liebig’s law of the minimum. However, ameliorating the disparities in the pursuit of SDGs presents a considerable challenge, especially in polar regions, including the Arctic, the Antarctic, and the Third Pole (the Tibetan Plateau and surrounding high mountain areas)3,4,5. Polar regions, covering approximately 20.1% (or ~300\(\times\)106 km2) of the global land area and 16.7% (or ~600\(\times\)106 km2) of the ocean area3, are recognized as outposts (or early warning systems) of climate change6,7.

Meanwhile, these regions serve as biodiversity reservoirs, water towers, and storage of climate driving gases8. They also provide a diverse array of ecosystem services that are critical for global sustainable development. For example, the fisheries in the Arctic and Antarctic contribute to achieving zero hunger (SDG2). The sustainable management of these fisheries is of great values to conserving and sustainably using global marine resources (SDG14)9. The Third Pole, with its total annual runoff exceeding 650\(\times\)109 m3, is vital for guaranteeing water security for downstream residents (SDG6)10. Furthermore, the protection and maintenance of high mountain vegetation and biodiversity are fundamental for the global protection and restoration of terrestrial ecosystems (SDG15).

However, sustainable development in polar regions has been largely overlooked in the formulation of global SDGs11. A mere 0.75% of the SDG-focused studies during 2015–2022 have considered polar regions, as indicated in our literature reviews (Supplementary Table 1). Furthermore, the marginalization of polar regions is also reflected in other international reports, such as the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Global Environment Outlook (GEO) series12. Beginning with GEO-213, polar regions have often been treated as side issues, highlighting their consistent underrepresentation in global environmental governance systems. In addition, there are currently no specific SDG indicators for the Arctic or Antarctic regions. Although mountain areas have garnered more attention than their polar counterparts, only 3 out of the 248 SDG indicators are associated with mountain regions14. This neglect of SDGs in polar regions is mainly due to the misapprehension that sustainable development in these areas is economically marginal and would contribute minimally to global SDG efforts, a belief stemming from their sparse populations and geographical remoteness.

Polar regions, as interconnected biophysical entities critical to planetary climate regulation, require governance models based on transnational collaboration and shared stewardship—principles central to SDG 17. However, current global environmental governance mechanisms often prioritize territorially bounded concerns over transboundary ecological interdependence. Existing frameworks lack institutional pathways to engage polar regions equitably in resource mobilization, knowledge co-creation, or technology transfer, despite their disproportionate climate-regulating functions. Therefore, the marginalization of these systems not only reflects ecological oversight but also a broader shortfall in operationalizing the cross-sectoral partnerships and policy coherence advocated by the SDG agenda.

In this study, we highlight the critical role of polar regions in global sustainable development in a teleconnection perspective using an online expert survey and bibliometric analysis. We posit that polar regions are the fragile boundaries of the planet’s climate commons15 because these regions are associated with 12 out of the 16 climate tipping elements identified thus far16,17. Furthermore, people living in these regions face heightened exposure to escalated risks attributable to dramatic climate change. These risks include thawing permafrost, reduced shore protection owing to the melting of sea ice and increased river flows, thereby leading to substantial climigration events18,19,20. However, the involvement of these communities in advancing the SDGs has been left behind11.

Therefore, given the fragilities in environmental, social, and economic sustainability, polar regions could be the “weakest link” in achieving global SDGs, akin to the “shortest stave” of Liebig’s barrel analogy. Neglecting these regions in the SDG framework could precipitate an unforeseen “tragedy of the commons”. More importantly, once polar regions are ‘left behind’, it might seriously impair the Earth’s sustainable future through the cascading effects of interconnected tipping elements21, thereby jeopardizing efforts to maintain planetary boundaries within a safe operating space22. If the right actions are implemented through global partnerships (SDG17), they would not only strengthen the sustainable development in polar regions, but also further enable the achievement of global SDGs.

Results

Impacts of climate change in polar regions and implications for global sustainable development

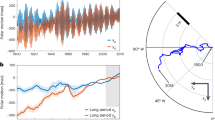

The polar regions have undergone catastrophic changes (Fig. 1) (See Methods) due to the amplification effect of warming23,24, profoundly impacting the achievement of SDG13—climate action. Beyond this, the teleconnection effects of polar climate tipping elements extend their influence on other SDGs. For example, the melting of polar glaciers and ice sheets alters global water distribution, directly impacting water resource management (SDG6) and exacerbating sea level rise, which threatens low-lying ecosystems (SDG15)25. Additionally, the reduction in polar sea ice has been linked to an increase in extreme weather events, destabilizing global ecosystems and indirectly affecting biodiversity and ecosystem services26.

The mean annual air temperature warming rate in the Arctic is 0.68 °C per decade, exceeding the 99% statistical confidence level. In contrast, the Antarctic warming rate was 0.08 °C per decade, which is not statistically significant with a p-value of 0.34. On the Tibetan Plateau, the warming rate from 1980 to 2022 is 0.35 °C per decade. Notably, the maximum warming rates of 0.36 °C per decade and 0.37 °C per decade were observed in the region between 4500 to 5000 m and 5500 to 6000 m, respectively, a phenomenon referred to as “elevation-dependent warming”27,28, which remains a subject of ongoing debate.

Glaciers and ice sheets in polar regions have experienced remarkable retreat. Between 1972 and 2022, the Greenland Ice Sheet lost approximately 5467 ± 535 Gt, corresponding to a decadal loss of 1072 ± 105 Gt. Similarly, the Antarctic ice sheet lost a total of 4,790 ± 987 Gt of ice between 1979 and 2022, equating to a decadal loss of 1089 ± 224 Gt. The Third Pole exhibited a decadal mass-balance change rate of −210 ± 70 Gt from 2000 to 2021.

The Arctic continues to experience a decline in sea ice, with an average annual reduction in sea ice extent of –4.6 ± 0.2% per decade from 1979 to 2023. Meanwhile, sea ice thickness has decreased at a rate of –0.43 m per decade from 1997 to 2021. In contrast, the gradual expansion of Antarctic Sea ice ceased in 2014, and recent loss rates have surpassed those observed in the Arctic. Overall, the trend in Antarctic Sea ice extent from 1979 to 2023 reflects a decline of –0.28 ± 0.50% per decade.

Both the snow cover duration and snow depth decreased in last several decades. In the Arctic region (such as North Canada, Siberian region), the average snow depth during September–May decreased by 1–3 cm per decade from 1980 to 2023. In the Antarctic region, the annual average snow accumulation remained relatively constant at approximately 35 cm per year prior to 1900 but increased at a rate of approximately 1.4 cm per decade after 1900. During the most recent decade (2000–2009), snow accumulation increased by approximately 30% of the baseline values determined from 1712 to 1899. Over the Tibetan Plateau, the average area with snow cover days exceeding 60 days during 2001/2002–2020/2021 decreased by ~31.21\(\times\)104 km2 compared to 1980/1981–2020/2021, and the average snow depth decreased by ~0.15 cm per decade.

The ground temperatures of permafrost in the three pole regions have increased in recent years. Notable permafrost warming has occurred in Arctic during 1981–2020, with a rate of 0.21 ± 0.24 °C per decade. The most substantial warming was observed in northwestern Siberia, northeastern Siberia, and the Arctic Svalbard Archipelago. In Antarctic, permafrost ground temperature increased by 0.25 ± 0.27 °C per decade during 2008–2020, with the most pronounced warming in the northeastern and eastern parts of the continent. In contrast, permafrost warming in the Third Pole was markedly lower than in the Arctic and Antarctic, with a rate of 0.06 ± 0.05 °C per decade during 1981–2020. Several factors contribute to these observed differences, including the greater latent heat effect of the warm permafrost in the Third Pole and the faster warming in the Arctic due to polar amplification effects29. Notably, the permafrost regions of the Arctic and the Tibetan Plateau are confirmed to contain substantial carbon reserves, estimated at 1460–1600 Pg and 15.31 Pg, respectively. In contrast, the carbon storage in Antarctica remains unproven.

ERA5-Land dataset reveals a pronounced increase in evapotranspiration rates in response to rising temperatures, with a rate of 8.3 mm per decade in the Arctic (R² = 0.67) and 9.0 mm per decade in the Tibetan Plateau (R² = 0.57). In contrast, no clear trend in runoff depth was detected (0.7 mm per decade in the Arctic, R² = 0.005; −6.7 mm per decade in the Tibetan Plateau, R² = 0.06), indicating considerable spatial variability. It is important to note that recent studies reveal substantial regional variability in Arctic lake dynamics, with an overall increase in lake numbers and water volumes, contrary to decreasing trends in some lakes30. Permafrost degradation is identified as a major factor in the reduction of certain Arctic lake areas31. Conversely, lakes in the Third Pole region have notably expanded over recent decades, primarily due to increased precipitation, glacier melt32, and permafrost degradation33,34,35,36.

In subarctic regions (latitude >60° N), treelines have shifted upward at an average rate of 4.76 m per decade from 1981 to 2018, which is closely correlated with precipitation changes in autumn, winter, and annual37. In the Tibetan Plateau, the average rate of upward shift over the past 100 years has been much lower, at 2.9 ± 2.9 m per decade (range: 0–8.0 m per decade). Although climatic warming has generally promoted the upward migration of alpine treelines, the rate of upslope movement in this region is primarily influenced by species interactions38.

In the Arctic, the growing season has lengthened by an average of 8.58 days from 1982 to 2014, corresponding to an increase of 2.60 days per decade. However, changes in growing season duration were not consistent across the entire period. From 1982 to 1999, the growing season lengthened at a rate of 5.06 days per decade, while from 2000 to 2014, it actually shortened by −1.08 days per decade, largely due to a warming hiatus during the latter period39. In the Tibetan Plateau, the start of the growing season advanced by 8.3 ± 2.0 days between 2000 and 2020, while the end of the season was delayed by 8.2 ± 1.9 days, resulting in an overall extension of the growing season by 7.86 days per decade during this period40. The arctic warming leads the increasing greenness because of shifts in plant species from graminoids towards shrubs, as well as increases in snow water equivalent, soil moisture, and active layer thickness41. However, some tundra areas show browning due to the earlier snow cover and ground ice melting under the background of greenness42,43.

Environmental changes in these regions are constitutionally interconnected, often abrupt, and could lead to disastrous consequences for humanity22. Amplified by climate change and the “telecoupling effects”44,45, shifts in polar environment pose severe threats to long-term climate goals and jeopardize the attainment of global SDGs. A salient example is that the rapid loss of ice sheet in Antarctic and Greenland, which contributes to a sea-level rise of 0.1–0.5 m46, potentially leading to coastal flooding and erosion. As a consequence, it is projected that by 2100, ~600 million people and 20% of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP) will be at risk47,48. Fortunately, substantial adaptation strategies have already been explored to mitigate these impacts49. However, a more alarming concern is that the meltwater from Arctic sea ice and Antarctic ice sheet could diminish seawater density and deep convection, potentially weakening or even halting the thermohaline circulation50, thus triggering abrupt temperature decreases51. A historical precedent for such is the Younger Dryas event, which occurred approximately 12,900 to 11,700 years before present and resulted in temperature plummet by several degrees Celsius within decades52. Indigenous peoples, who are intimately connected to environment and resources in polar regions, are among the earliest to confront the direct impacts of pole climate change. For instance, in the Third Pole, nearly 2 billion people depend on freshwater provided by the Asian’s water towers4. However, the cascading effect of increasing disasters such as avalanche and glacial lake outburst in these areas may amplify the damage to the downstream populations and infrastructure53.

Polar regions are teleconnected with other parts of the global system

We carried out an online expert survey to quantify the relationship between the polar regions and the realization of global SDGs from the polar and mountain research communities (see Methods). This survey reflects the current understanding of the scientific community on this teleconnection (Fig. 2).

a SDG1 to SDG6. b SDG 1 to SDG12. c SDG 13 to SDG17. This assessment was based on an expert survey (n = 163 independent responses), and each data point represents an independent expert evaluation. The importance of polar regions for SDG were scored from 1 to 10, with 1 signifies not important at all and 10 indicates most important. Box plots represent the median (centre line), the interquartile range (box bounds: 25th–75th percentiles), and whiskers extending to the most extreme data points within 2×interquartile range. Outliers beyond this range are shown as individual points. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The results indicated that all 17 SDGs are potentially affected by polar regions, with mean teleconnection effect scores (TES) ranging from 5.9 to 8.8 and associated uncertainties spanning from 1.9 to 3.0. Notably, climate action (SDG13) received the highest score with mean TES value (TESmean) of 8.8 and median TES value (TESmedia) of 10, underscoring the great influence of polar regions on global SDGs through climate action. This is partially linked to the presence of climate tipping elements in polar regions. Following closely was clean water and sanitation (SDG6), with a TESmean of 8.5, aligning with pivotal role of polar regions in sustaining global water resource. Life on land (SDG15) and life below water (SDG14) attained scores of 8.1 and 7.9, respectively, ranking third and fourth and highlighting the critical contribution of polar region ecosystem services and biodiversity to global sustainability. Interestingly, most participants stated the criticality of SDG17—global partnership, reflecting the importance of polar regions in achieving global sustainable development fairly and evenly. The relatively low standard deviations for these five SDG goals further corroborate a widespread consensus on their importance. For societal SDGs, responses of participants indicated that SDG 3—good health is important (TESmean = 7.4), suggesting the potential of polar regions to impact global health and well-being. However, SDGs related to social fairness (SDG4: quality education; SDG5: gender equality; and SDG10: reduced inequalities) were scored lower (6.3, 5.9, and 6.3) with high uncertainties (2.9, 3.0, and 2.8), indicating that these goals hold lesser relevance for polar regions in achieving global SDGs, albeit with a recognition of limited consensus. These reports also implied the importance of considering this issue in a perspective of social equality.

To further substantiate that climate action (SDG13) can influence the other SDGs54 and to determine which polar regions are most critical, we conducted an analysis based on the SDG-related keywords of the recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports (see Methods, Supplementary Tables 2–6).

The concept of SDG has emerged as the most frequently mentioned topic in the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), the Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (SROCC), and the Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C (SR1.5). Particularly, the AR6 report on Mitigation of Climate Change and SR1.5 highlights the intricate interconnections between climate actions and SDGs. SR1.5 includes a dedicated chapter on SDGs, elucidating that synergies dominate the relationship between climate action and the other SDGs, and that trade-offs can be effectively managed through enhanced capacity building, governance, and technology.

In these reports, polar regions and mountains are highlighted as outposts of climate change. The IPCC SROCC states that intensifying changes in the ocean and cryosphere poses great challenges to achieving all SDG goals. The IPCC AR6 report on Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability includes dedicated chapters on Polar regions and Mountains. These sections demonstrate that strengthening climate action can reduce the risks associated with failing to achieve other SDGs. Furthermore, social system transformation, particularly in terms of justice and equity (with a special focus on Indigenous people), can strengthen climate resilient capacity, advancing the achievement of SDGs. Consequently, given the critical role of polar regions in climate action, ensuring sustainable development in these regions is not only contributory but also a facilitator in the achievement of global SDGs.

Revising and localizing the SDGs for polar regions

Our analysis underscores the urgent need to revise and localize the SDGs for polar regions, which are confronted by unique challenges, such as tipping elements, sparse populations, harsh environmental conditions, and the critical role of Indigenous cultures and knowledge55,56,57. Although these regions hold immense global importance, current UN SDG indicators inadequately address these unique aspects, with only five indicators (SDG 2.3, 2.5, 6.6, 15.1, 15.4) directly applicable to the polar regions57. Our findings highlight the necessity of introducing a specific SDG target and five additional indicators (Table 1) that resonate with the specific characteristics and telecoupling effects seen in polar regions, as evidenced by the survey results (Fig. 2). These initiatives are designed to refine existing SDGs to better address the unique needs of polar regions, ensuring that the global commitment to “leave no one behind” is truly inclusive.

Considering the pivotal role of the cryosphere in climate actions and its connection to critical tipping elements vital for global sustainability, we recommend adding a dedicated target for the cryosphere under SDG 13 (climate action), designated as SDG 13.4. We further propose a specific indicator to monitor cryosphere’s key components —ice sheets, glaciers, snow, permafrost, and sea ice—across both polar and high mountain areas. This indicator would provide a more accurate assessment of the changes in these critical systems.

The well-being and health of Indigenous peoples, as well as the preservation of their cultures, are of paramount importance. In polar regions, life expectancy is remarkably lower compared to other regions, attributable to the harsh natural environment, scarce medical resources, and widely dispersed populations. Besides, resident health in these regions faces additional threats from the impacts of climate change. To address these challenges, we propose a specific indicator under SDG 3.4 to enhance the awareness and support for human health in extreme environments. The traditional lifestyles and culture of Indigenous peoples in polar regions are also being transformed by climate change and the forces of globalization. To preserve these cultural heritages, we recommend adding a specific indicator under SDG 4.7, specifically aimed at promoting education in traditional cultural practices within polar communities.

Since biodiversity conservation in polar regions requires a unified global effort, we propose the inclusion of a specific indicator of SDG 15.a.2, aimed at increasing attention and securing funding for biodiversity protection in these fragile ecosystems. Data is a cornerstone for effective evaluation and management. To deepen our understanding of polar environments, we propose a specific indicator of SDG 17.6.2 to promote the development of robust information infrastructure in polar regions, thereby facilitating data sharing and fostering collaborative innovation.

Figure 3 outlines the strategic roadmap for integrating these proposed targets and indicators with existing SDG framework. The figure highlights the critical role of tipping elements, placing them within the broader climate context and emphasizing the intricate interactions between natural and human systems. It emphasizes the destabilizing effects of natural system tipping elements while also acknowledging the potential of social tipping points in protecting polar regions and supporting the achievement of SDGs. The figure also stresses the importance of addressing both nature-related and human-related aspects, proposing concrete goals for clean water, life below water and on land, as well as health, education, and equality for Indigenous peoples. Central to this framework is the proposed climate action target (SDG 13.4) and the fostering of global partnerships to ensure fair and equitable progress across these dimensions.

a Global distribution of climate tipping elements, atmospheric circulation patterns, and biosphere components affecting polar regions (Adapted from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research under a Creative Commons License)95. b Nature-related revised and localized indicators crucial for polar regions, covering clean water and sanitation (SDG 6), life below water (SDG 14), and life on land (SDG 15). c Proposed target and indicators for climate action (SDG 13), supported by global partnerships (SDG 17) to ensure fair and equitable implementation. d Human-related revised and localized indicators important for polar regions and Indigenous peoples, addressing good health and well-being (SDG 3), quality education (SDG 4), gender equality (SDG 5), and reduced inequalities (SDG 10). The figure illustrates the interconnected dynamics between natural system tipping elements and social tipping elements, underscoring their role in achieving SDGs in polar contexts.

Discussion

Our study highlights the critical importance of polar regions in achieving global SDGs, particularly in relation to climate action. Despite their current underrepresentation in SDG frameworks, we have demonstrated that polar regions play a pivotal role in maintaining Earth’s environmental stability and resilience. The cascading effects of polar tipping elements on global environmental, social, and economic sustainability underscore the urgent need for targeted action and improved understanding of these vulnerable regions. These tipping elements not only directly impact climate action (SDG13) but also trigger a series of indirect effects on other SDGs. For instance, sea level rise resulting from the melting of polar ice sheets threatens populations and ecosystems in low-lying areas, impacting poverty reduction (SDG1), health (SDG3), and food security (SDG2). Furthermore, changes in the cryosphere substantially affect global water cycles, complicating sustainable water management goals (SDG6), while disruptions to polar ecosystems contribute to biodiversity loss and ecosystem service decline (SDG15).

Indigenous communities play a vital role in these processes, offering traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) that provides invaluable insights into local environmental changes, such as shifts in sea ice conditions and wildlife behaviors, which can improve early warning systems for climate adaptation58. In the Arctic, for instance, Indigenous knowledge of ice conditions has long informed seasonal hunting practices, offering perspectives on polar tipping points that complement and enrich scientific data. Beyond observation, TEK embodies a profound tradition of coexistence, adaptation, and influence within nature, affirming Indigenous communities as active participants in ecosystem dynamics. Reindeer herding peoples of the Arctic, such as those in Russia and Nordic countries, exemplify this interplay. Their adaptive practices, including shifting grazing patterns cause treeline migration, reflect both natural climatic changes and anthropogenic impacts like policy shifts that have eroded community resilience59. Similarly, nomadic communities in the Third Pole demonstrate adaptive capacities shaped by their deep connection to dynamic landscapes. Coastal Indigenous communities, such as the Inuit, further illustrate the enduring relevance of TEK in navigating climatic variability. Historically, their nuanced understanding of ice conditions has enabled sustainable hunting practices, showcasing resilience in variable climates. However, the unprecedented pace and scale of modern climate change have exceeded the domain of traditional knowledge. Initiatives like SmartICE (https://smartice.org/) demonstrate how TEK is being integrated with technological innovations, fostering new pathways for adaptation and resilience in a rapidly changing environment. Beyond adaptation, TEK offers vital contributions to sustainable land and resource management, aligning closely with SDG15 by preserving ecosystems through Indigenous conservation practices. These cultural and ecological insights underscore the importance of safeguarding Indigenous practices as a cornerstone of global sustainability efforts.

Our findings have revealed the necessity of revising existing SDG indicators to capture the unique challenges and contributions of polar areas. Therefore, we have proposed specific targets and indicators that account for the teleconnection effects of polar tipping elements, with particular attention to rapid cryosphere changes and their global impacts. These proposals are designed to deepen our understanding of polar-global interactions, provide accurate assessment of cryosphere services, and examine the interrelations between social and natural tipping points. This work supports the United Nations General Assembly’s declaration of 2025-2034 as the Decade of Action for Cryospheric Sciences, a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)-led initiative that recognizes the cryosphere’s fundamental role in Earth’s climate system (www.unesco.org/en/articles/united-nations-general-assembly-approves-decade-action-cryospheric-sciences-2025-2034).

For effective implementation of these strategies, we identify two critical areas for immediate priorities: enriching cyberinfrastructure and observation systems, and strengthening fundamental science research in polar regions. These efforts are essential for integrating polar regions into global sustainability efforts and harnessing their potential in achieving SDGs. The importance of Earth observations in achieving global SDGs is well-established60. Simultaneously, social sensing data, including community-based monitoring initiatives, provide valuable insights into social systems and Indigenous perspectives61. To maximize the utility of these diverse data sources, it is crucial to implement both FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable)62 and CARE (Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, and Ethics) principles in data governance. This ensures data accessibility and protects the rights of Indigenous peoples63.

We propose the development of an integrated, interoperable polar data platform to support comprehensive SDG assessments and strategy optimization in polar regions64. By enhancing data integration, this platform would also facilitate cross-border and cross-sector collaborations, driving advancements in integrated system modeling and polar research.

Addressing the multifaceted challenges of polar regions and their global impacts demands a robust foundation in multidisciplinary science. Comprehensive assessment of proposed indicators and the formulation of strategies for polar regions requires a deep understanding of polar-global teleconnections and the identification of tipping points65. Developing high-resolution atmosphere-ocean-ice-land coupled models that can capture key dynamics of polar regions is crucial, particularly when considering complex mechanisms like thermohaline circulation66 in deep ocean and Rossby wave67 in deep space. Accurately quantifying cryosphere services and their contributions to global SDGs requires innovative modeling approaches. These models should comprehensively assess the economic impact of cryosphere melting, including service loss and potential disasters68,69. Establishing global mechanisms for valuing and compensating cryosphere services, particularly their role in climate regulation, is essential to raise awareness of polar regions’ importance in achieving SDGs. These efforts are consistent with the nature-human interactions outlined Fig. 3, which highlights the deep interconnectedness of natural and social systems in polar regions. Additionally, advancing integrated assessment models or developing reciprocally coupled human-natural system models specific for polar regions is vital. Recent system dynamic models70,71 have quantified the feedbacks of global emissions reductions, technological developments, climate education, and shifts in perceptions, values, and norms on alleviating devasting climate change. Such models can elucidate how social tipping elements might influence cryosphere changes, offering insights into ways to avoid critical tipping points, and optimize synergies between polar and global SDG targets.

Despite providing valuable insights into revising SDGs for polar regions, this research has several limitations. First, the study relies heavily on expert opinions and existing literature, which may not fully capture the rapidly changing dynamics of polar environments. The timing of expert selection and the scope of literature review may also limit the robustness of the conclusions. Future studies could benefit from broader expert participation and a more comprehensive bibliometric approach, particularly by incorporating a wider range of keywords72. Second, our proposed framework may not adequately address potential conflicts between global climate goals and local development needs in polar areas, especially with respect to Indigenous peoples. Third, the successful implementation of these proposed SDG revisions would require extensive international cooperation and resource allocation, the feasibility of which this study has not fully explored. Lastly, the rapidly evolving nature of social and environmental interactions in polar regions presents an ongoing challenge for accurate long-term projections and policy recommendations.

Although our study focuses on polar regions, the findings and methodological approaches have wider relevance for other remote and sparsely populated areas globally. The framework we propose for assessing and integrating unique regional characteristics into the SDG agenda could be adapted for other challenging environments, such as deserts, high mountain regions outside the Third Pole, or remote island communities. This approach highlights the importance of considering diverse geographical contexts in global sustainability efforts, ensuring that no region, regardless of its remoteness or unique challenges, is left behind in the pursuit of the SDGs.

In summary, the polar regions, as crucial climate commons of our blue planet, are currently at a pivotal juncture due to dramatic climate change and have a great impact on the achievement of global SDGs. The failure to effectively preserve the Earth’s three poles presents a risk to tipping points that is “too risky to bet against”. Therefore, we are faced with a choice between remaining passive, thereby being “left behind” and taking right actions. Indigenous communities could play key roles in the design and practice of polar SDGs. However, due to the cascading tipping dynamics, the governance of polar regions must ultimately involve a global effort. SDGs are not a champagne glass; their fair and universal achievement requires active, inclusive partnership. International cooperation could be enhanced through the development of shared observation systems and integrated data platforms that support collaborative research on polar ecosystems and climate change. Successful cross-border initiatives, such as the Decade of Action for Cryospheric Sciences, the Arctic Council’s Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP), the International Polar Year (2007–2008) and its upcoming 2032–2033 successor, as well as academic networks like the University of the Arctic and the Himalayan Universities Consortium, serve as scalable models for polar cooperation. These initiatives, along with early-career programs such as Association of Polar Early Career Scientists (APECS), play a crucial role in advancing collaborative research, enhancing data-sharing mechanisms, and building capacity for effective transboundary governance in polar regions. As the proverb goes, “a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step”, let us engage in collective actions and transform the Earth’s fragile boundaries into a proving ground for sustainable development through global partnerships.

Methods

Air temperature changes in polar regions

The ERA5 monthly average surface air temperature dataset (1980–2023) was used to calculate the annual mean temperature change rate in both the Arctic (north of 66°N) and Antarctic (south of 66°S), utilizing a resolution of 0.25° (https://www.ecmwf.int)73. For the Tibetan Plateau, a near-surface meteorological forcing dataset for the Third Pole region (TPMFD, 1980–2022) was employed, due to its higher resolution of 1/30° (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn)74,75. Temperature trends were determined using least-squares linear regression, and statistical significance was evaluated with the two-tailed Student’s t test75,76. For polar regions, ERA5 remains one of the most widely used and reliable reanalysis products despite some inherent limitations. Previous studies have demonstrated that ERA5 effectively represents temperature variations in polar areas when compared with ground-based observations77,78,79. In the Third Pole region specifically, ERA5 and TPMFD display comparable temperature increase trends, although discrepancies exist in their absolute mean temperature values. Benefiting from finer spatial resolution and improved accuracy, TPMFD provides enhanced capability to resolve spatial details of climate warming patterns.

Glacier and ice sheet changes in polar regions

The dataset provides reconciled ice mass balance estimates for the Greenland and Antarctic Ice Sheets, derived from three independent satellite techniques: gravimetry, altimetry, and the input-output method. This dataset updates from Otosaka et al.80, which is part of the Ice Sheet Mass Balance Inter-comparison Exercise (IMBIE). A detailed synthesis of satellite datasets, Glacial Isostatic Adjustment (GIA) and Surface Mass Balance (SMB) models used to derive the individual estimates of ice sheet mass balance is available in Zhao et al.81. For Greenland, the dataset includes 26 individual surveys, while 24 surveys were used for Antarctica. For the Third Pole, the glacier mass change was estimated using the large-scale glacier evolution model Open Global Glacier Model (OGGM), which was driven by monthly temperature and precipitation data from ERA5-Land reanalysis dataset for the historical simulations (2000–2021) as well as 10 bias-corrected General Circulation Models (GCMs).

Sea ice changes in polar regions

The sea ice extent was calculated using passive microwave brightness temperature data from SMMR, SSM/I and SSMIS82,83. Sea ice thickness data were derived from ICESat and CryoSat-2 data from 2011-2021 and combined with submarine cruise measurements from 1958–1976 to 1993–1997 using regression analysis, resulting in a regression residual with a standard deviation of 0.46 m. Linear trend analysis was conducted to assess the trends in Arctic and Antarctic Sea ice extent and thickness.

Snow cover changes in polar regions

The Daily 5-m Gap-free AVHRR snow cover extent (SCE) product over China (1980–2021)84 and the long-term time series of daily snow depth data in China (1980–2023)85,86 were utilized to analyze the spatial and temporal variations in snow cover area and snow depth in the Tibetan Plateau. The SCE data and snow depth data are archived in the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center, China. The temporal resolution is daily, and the spatial resolutions of them are 5 km (SCE) and 25 km (snow depth), respectively. The simulated snow depth data from ERA5-Land product were used to analyze the snow depth variation in the Arctic regions87. This data ranges spans from January 1950 to 2023, with spatial and temporal resolutions of 0.1°and hourly, respectively. For Antarctica, no long-term snow accumulation data are available. Therefore, we referred to the results of Thomos et al.88, which are based on 300 years of snow accumulation records from two ice cores drilled in Ellsworth Land, West Antarctica.

Permafrost changes in polar regions

The warming rates of permafrost in the Arctic, Antarctic, and the Third Pole were derived from ground temperature measurements at a depth of 10 m using linear regression. The ground temperature measurement data were sourced from the Global Terrestrial Network for Permafrost (GTN-P) and the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn). However, the original measurement data cover a short time span and contain substantial gaps. To address these issues, we reconstructed and extended the original ground temperature time series from 1981 to 2020, excluding Antarctic, using a physically informed machine learning model89. The root mean square error (RMSE) of the reconstructed ground temperatures for the Arctic and the Third Pole are 0.15 ± 0.12 °C and 0.11 ± 0.003 °C, respectively. The number of observation sites in the Arctic, Antarctic, and the Third Pole are 79, 5, and 5.

Hydrological changes in polar regions

Runoff and evapotranspiration were obtained from the ERA5-Land dataset, spanning from 1981 to 2020 on a monthly basis (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu). The Third Pole region is defined as the area above 4000 m elevation on the Tibetan Plateau1. The Arctic region boundary follows the delineation provided by the AMAP, as specified by the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn). Simple linear regression analysis was employed to identify the trends in runoff and evapotranspiration.

Ecosystem changes in polar regions

For subarctic regions (latitude >60°N), treeline data from 28 sites were retained from articles and reports published between 1986 and 2020. For the Tibetan Plateau, data were collected from 14 treeline plots located between 28.4°N and 38.5°N. A meta-analysis of annual treeline shift rates was then conducted for the subarctic regions, while for the Tibetan Plateau, the location of the treeline was reconstructed at 50-year intervals using standard dendrochronological methods.

To analyze phenology in these regions, global CSIF data from 2000 to 2020 were used to derive phenology metrics for the Arctic region. Meanwhile, for the Tibetan Plateau, phenology metrics were calculated from MODIS NDVI (normalized difference vegetation index) and EVI (enhanced vegetation index) data over the same period. The trends in phenology metrics were evaluated by calculating the slope of a simple linear regression between phenology metrics and year.

Bibliometric survey to explore the SDG knowledge in the polar regions

To explore how scientists advance sustainable development knowledge in the polar regions, we conducted a bibliometric analysis based on the core collection from the Web of Science (WoS). The numbers of publications with the given topics were counted for the period before 2015 and 2015–2022, the year when the SDGs were officially released. The total number of publications was identified by searching “SDGs” in WoS. Publications that also featured keywords related to polar region were categorized as polar SDG-related publications (Supplementary Table 1).

The four sets of keywords, each with multiple spelling variations, are listed below. SDG includes the keywords “SDG” and “SDGs”. Arctic includes the keywords Arctic, North Pole, North Polar, and North Magnetic Pole. Antarctic includes the keywords Antarctic, South Pole, South Polar, and South Magnetic Pole. Third Pole includes the keywords Third Pole, the Tibet Plateau, Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, Himalaya, and Hindu Kush Mountain.

The keywords based bibliometric analysis here may encompass all definitions of the polar regions, particularly in the Arctic72. This could lead to a slight discrepancy between the bibliometric analysis and the AMAP boundaries used for quantitative spatial statistics in the study. We assume that this difference will not affect the conclusion that sustainable development in polar regions has been largely overlooked in the formulation of global SDGs.

Quantifying the teleconnection effects of the polar regions in achieving SDGs

To empirically evaluate the importance of polar regions in achieving global SDGs, we conducted an online survey using Google Forms. Experts were invited to score the importance of polar regions (the Antarctic, Arctic, and Third Pole) in contributing to the SDGs. A global pool of 1173 experts, specializing on polar and mountain research, was selected globally. This selection included authors of the SROCC and contributors to four cryosphere-related journals: The Cryosphere, Journal of Glaciology, Permafrost and Periglacial Processes, and Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research. In total, we ultimately received 163 survey responses. For details about the survey process, refer to Supplementary Method 1. These responses provided a distribution of scores across all SDGs, as detailed in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Relationship analysis of climate action and other SDGs regarding polar regions

To explore the relationship between climate action (SDG 13) and the other SDGs, as well as the importance of polar regions in reinforcing or undermining these relationship, the SDG keywords were counted and analyzed for each chapter in the sixth cycle of IPCC reports, including: the IPCC Sixth Assessment Reports (AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023, Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis90, IPCC AR6 Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability91, and IPCC AR6 Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change92), the IPCC SROCC93, and the IPCC SR1.594 (Supplementary Tables 2–6).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data used in this study are publicly accessible. The ERA5 monthly average surface air temperature dataset are publicly available at https://www.ecmwf.int, while the ERA5-Land dataset for global snow cover, runoff, and evapotranspiration are available at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu. The passive microwave brightness temperature data from SMMR, SSM/I, and SSMIS for sea ice are available at https://doi.org/10.7265/n5k072f8 and updated timely. The Near-surface meteorological forcing dataset for the Third Pole region are available at https://doi.org/10.11888/Atmos.tpdc.300398. The snow cover extent data in China are available at https://doi.org/10.12072/ncdc.I-snow.db0005.2020, while the snow depth dataset in China are available at https://doi.org/10.11888/Geogra.tpdc.270194. The ground temperature measurements data are sourced from the Global Terrestrial Network for Permafrost (GTN-P) (http://gtnpdatabase.org/boreholes) and the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (https://doi.org/10.11888/Geocry.tpdc.271107). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All computer code used in conducting the analyses summarized in this paper is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

World Bank. Country and Lending Groups. World Bank Data Help Desk. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519 (2025).

Thomas, P. & Emmanuel, S. Inequality in the long run. Science 344, 838–843 (2014).

Li, X. et al. CASEarth Poles: nig data for the three poles. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 101, E1475–E1491 (2020).

Yao, T. et al. The imbalance of the Asian water tower. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 618–632 (2022).

Hock, R. et al. High Mountain Areas. In IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (eds. Pörtner, H.-O. et al.) 131–202 (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

You, Q. et al. Warming amplification over the Arctic Pole and Third Pole: trends, mechanisms and consequences. Earth Sci. Rev. 217, 103625 (2021).

Duarte, C. M., Lenton, T. M., Wadhams, P. & Wassmann, P. Abrupt climate change in the Arctic. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 60–62 (2012).

Bohlmann, U. M. & Koller, V. F. ESA and the Arctic - the European Space Agency’s contributions to a sustainable Arctic. Acta Astronaut 176, 33–39 (2020).

Petterson, M. G., Kim, H. J. & Gill, J. C. Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources. in Geosciences and the Sustainable Development Goals (Springer International Publishing). https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-38815-7_14/ (2021).

Wang, L. et al. TP-River: monitoring and quantifying total river runoff from the Third Pole. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 102, E948–E965 (2021).

Degai, T. S. & Petrov, A. N. Rethinking Arctic sustainable development agenda through indigenizing UN sustainable development goals. Int. J. Sust. Dev. World 28, 518–523 (2021).

United Nations Environment Programme, (UNEP), Global Environment Outlook 6 (UNEP). https://www.unep.org/resources/global-environment-outlook-6 (2019).

United Nations Environment Programme, (UNEP), Global Environment Outlook 2UNEP). https://www.unep.org/resources/global-environment-outlook-2 (1999).

Makino, Y., Manuelli, S. & Hook, L. Accelerating the movement for mountain peoples and policies. Science 365, 1084–1086 (2019).

Tavoni, A. & Levin, S. Managing the climate commons at the nexus of ecology, behaviour and economics. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 1057–1063 (2014).

Lenton, T. M. et al. Climate tipping points — too risky to bet against. Nature 575, 592–595 (2019).

Armstrong McKay, D. I. et al. Exceeding 1.5 °C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points. Science 377, eabn7950 (2022).

Immerzeel, W. W., van Beek, L. P. H. & Bierkens, M. F. P. Climate change will affect the Asian water towers. Science 328, 1382–1385 (2010).

Smith, S. L., O’Neill, H. B., Isaksen, K., Noetzli, J. & Romanovsky, V. E. The changing thermal state of permafrost. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 10–23 (2022).

Post, E. et al. Ecological consequences of sea-ice decline. Science 341, 519–524 (2013).

Liu, T. et al. Teleconnections among tipping elements in the Earth system. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 67–74 (2023).

Rockström, J. et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 461, 472–475 (2009).

Cohen, J. et al. Divergent consensuses on Arctic amplification influence on midlatitude severe winter weather. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 20–29 (2020).

Blackport, R. & Screen, J. A. Insignificant effect of Arctic amplification on the amplitude of midlatitude atmospheric waves. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay2880 (2020).

Zemp, M. et al. Global glacier mass changes and their contributions to sea-level rise from 1961 to 2016. Nature 568, 382–386 (2019).

Cohen, J. et al. Linking Arctic variability and change with extreme winter weather in the United States. Science 373, 1116–1121 (2021).

Pepin, N. et al. Elevation-dependent warming in mountain regions of the world. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 424–430 (2015).

You, Q. et al. Elevation dependent warming over the Tibetan Plateau: patterns, mechanisms and perspectives. Earth Sci. Rev. 210, 103349 (2020).

Wang, X. et al. Contrasting characteristics, changes, and linkages of permafrost between the Arctic and the Third Pole. Earth Sci. Rev. 230, 104042 (2022).

Shugar, D. H. et al. Rapid worldwide growth of glacial lakes since 1990. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 939–945 (2020).

Briggs, M. A. et al. New permafrost is forming around shrinking Arctic lakes, but will it last? Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 1585–1592 (2014).

Dai, A. & Song, M. Little influence of Arctic amplification on mid-latitude climate. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 231–237 (2020).

Zhang, G. et al. 100 years of lake evolution over the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 3951–3966 (2021).

Luo, S. et al. Satellite laser altimetry reveals a net water mass gain in global lakes with spatial heterogeneity in the early 21st century. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL096676 (2022).

Zhang, G. et al. Response of Tibetan Plateau lakes to climate change: trends, patterns, and mechanisms. Earth Sci. Rev. 208, 103269 (2020).

Zhang, G. et al. Extensive and drastically different alpine lake changes on Asia’s high plateaus during the past four decades. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 252–260 (2017).

Lu, X. et al. Mountain treelines climb slowly despite rapid climate warming. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 30, 305–315 (2021).

Liang, E. et al. Species interactions slow warming-induced upward shifts of treelines on the Tibetan Plateau. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 4380–4385 (2016).

Madani, N., Parazoo, N. C. & Miller, C. E. Climate change is enforcing physiological changes in Arctic ecosystems. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 074027 (2023).

Shen, M. et al. Plant phenology changes and drivers on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 633–651 (2022).

Myers-Smith, I. H. et al. Climate sensitivity of shrub growth across the tundra biome. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 887–891 (2015).

Phoenix, G. K. & Bjerke, J. W. Arctic browning: extreme events and trends reversing Arctic greening. Glob. Chang. Biol. 22, 2960–2962 (2016).

Bhatt, U. et al. Changing seasonality of panarctic tundra vegetation in relationship to climatic variables. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 055003 (2017).

Malinauskaite, L., Cook, D., Davíðsdóttir, B., Ögmundardóttir, H. & Roman, J. Ecosystem services in the Arctic: a thematic review. Ecosyst. Serv. 36, 100898 (2019).

Pongrácz, E., Pavlov, V. & Hänninen, N. Arctic Marine Sustainability (Springer Nature, 2020).

Edwards, T. L. et al. Projected land ice contributions to twenty-first-century sea level rise. Nature 593, 74–82 (2021).

Neumann, B., Vafeidis, A. T., Zimmermann, J. & Nicholls, R. J. Future coastal population growth and exposure to sea-level rise and coastal flooding - a global assessment. Plos ONE 10, e0131375 (2015).

Kirezci, E. et al. Projections of global-scale extreme sea levels and resulting episodic coastal flooding over the 21st Century. Sci. Rep. 10, 11629 (2020).

Hinkel, J. et al. The ability of societies to adapt to twenty-first-century sea level rise. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 570–578 (2018).

Hansen, J. et al. Ice melt, sea level rise and superstorms: evidence from paleoclimate data, climate modeling, and modern observations that 2 °C global warming could be dangerous. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 3761–3812 (2016).

Marotzke, J. Abrupt climate change and thermohaline circulation: Mechanisms and predictability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 1347–1350 (2000).

Fairbanks, R. G. A 17,000-year glacio-eustatic sea level record: influence of glacial melting rates on the Younger Dryas event and deep-ocean circulation. Nature 342, 637–642 (1989).

Shugar, D. H. et al. A massive rock and ice avalanche caused the 2021 disaster at Chamoli, Indian Himalaya. Science 373, 300–306 (2021).

Fuso Nerini, F. et al. Connecting climate action with other sustainable development goals. Nat. Sustain. 2, 674–680 (2019).

Xiao, C., Su, B., Wang, X. & Qin, D. Cascading risks to the deterioration in cryospheric functions and services. Chin. Sci. Bull. 64, 1975–1984 (2019).

Otto, I. M. et al. Social tipping dynamics for stabilizing Earth’s climate by 2050. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 2354–2365 (2020).

Nilsson, A. E. & Larsen, J. N. Making regional sense of global sustainable development indicators for the Arctic. Sustainability 12, 1027 (2020).

Galicia, M. P., Thiemann, G. W. & Dyck, M. G. Correlates of seasonal change in the body condition of an Arctic top predator. Glob. Chang. Biol. 26, 840–850 (2020).

Mathiesen, S. D. et al. Reindeer Husbandry, (eds Mathiesen, S. D., Eira, I. M. G., Turi, I. E. et al.) (Springer, 2023).

Guo, H. et al. Measuring and evaluating SDG indicators with Big Earth Data. Sci. Bull. 67, 1792–1801 (2022).

Fritz, S. et al. Citizen science and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2, 922–930 (2019).

Wilkinson, M. D. et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data 3, 160018 (2016).

Carroll, S. R., Herczog, E., Hudson, M., Russell, K. & Stall, S. Operationalizing the CARE and FAIR Principles for Indigenous data futures. Sci. Data 8, 108 (2021).

Alexander, S. M. et al. Qualitative data sharing and synthesis for sustainability science. Nat. Sustain. 3, 81–88 (2020).

Guo, H., Li, X. & Qiu, Y. Comparison of global change at the Earth’s three poles using spaceborne Earth observation. Sci. Bull. 65, 1320–1323 (2020).

Clark, P. U., Pisias, N. G., Stocker, T. F. & Weaver, A. J. The role of the thermohaline circulation in abrupt climate change. Nature 415, 863–869 (2002).

Li, X. et al. Tropical teleconnection impacts on Antarctic climate changes. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 680–698 (2021).

Dutton, A. et al. Sea-level rise due to polar ice-sheet mass loss during past warm periods. Science 349, aaa4019 (2015).

Garcia, R. A., Cabeza, M., Rahbek, C. & Araújo, M. B. Multiple dimensions of climate change and their implications for biodiversity. Science 344, 1247579 (2014).

Ramanathan, V., Xu, Y. & Versaci, A. Modelling human–natural systems interactions with implications for twenty-first-century warming. Nat. Sustain. 5, 263–271 (2022).

Moore, F. C. et al. Determinants of emissions pathways in the coupled climate–social system. Nature 603, 103–111 (2022).

Aksnes, D. W., Blöcker, C., Colliander, C. & Nilsson, L. M. Arctic research trends: bibliometrics 2016-2022 (Arctic Centre at Umeå University). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7961981. (2023).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Jiang, Y. et al. TPHiPr: a long-term (1979–2020) high-accuracy precipitation dataset (1/30◦, daily) for the Third Pole region based on high-resolution atmospheric modeling and dense observations. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 621–638 (2023).

He, J. et al. The first high-resolution meteorological forcing dataset for land process studies over China. Sci. Data 7, 25 (2020).

Yang, K. et al. A high-resolution near-surface meteorological forcing dataset for the Third Pole region (TPMFD, 1979–2022), National Tibetan Plateau Data Center. https://doi.org/10.11888/Atmos.tpdc.300398 (2023).

Bromwich, D. H., Ensign, A., Wang, S. H. & Zou, X. Major artifacts in ERA5 2-m air temperature trends over Antarctica prior to and during the modern satellite era. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL111907 (2024).

Wang, C., Graham, R. M., Wang, K., Gerland, S. & Granskog, M. A. Comparison of ERA5 and ERA-Interim near-surface air temperature, snowfall and precipitation over Arctic sea ice: effects on sea ice thermodynamics and evolution. Cryosphere 13, 1661–1679 (2019).

Yan, S. et al. Which global reanalysis dataset has better representativeness in snow cover on the Tibetan Plateau? Cryosphere 18, 4089–4109 (2024).

Otosaka, I. N. et al. Mass balance of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets from 1992 to 2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 1597–1616 (2023).

Zhao, H., Su, B., Lei, H., Zhang, T. & Xiao, C. A new projection for glacier mass and runoff changes over High Mountain Asia. Sci. Bull. 68, 43–47 (2023).

Fetterer, F., Knowles, K., Meier, W. N., Savoie, M. & Windnagel, A. K. Sea ice index (G02135, Version 3), National Snow and Ice Data Center. https://doi.org/10.7265/N5K072F8 (2024).

Roach, L. A. & Meier, W. N. Sea ice in 2023. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 5, 235–237 (2024).

Hao, X. et al. The NIEER AVHRR snow cover extent product over China – a long-term daily snow record for regional climate research. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4711–4726 (2021).

Che, T., Li, X., Jin, R., Armstrong, R. & Zhang, T. Snow depth derived from passive microwave remote-sensing data in China. Ann. Glaciol. 49, 145–154 (2008).

Dai, L., Che, T. & Ding, Y. Inter-calibrating SMMR, SSM/I and SSMI/S data to improve the consistency of snow-depth products in China. Remote Sens 7, 7212–7230 (2015).

Muñoz-Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-Land: a state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4349–4383 (2021).

Thomas, E. R., Hosking, J. S., Tuckwell, R. R., Warren, R. A. & Ludlow, E. C. Twentieth century increase in snowfall in coastal West Antarctica. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 9387–9393 (2015).

Liu, Y., Ran, Y., Li, X., Che, T. & Wu, T. Multisite evaluation of physics-informed deep learning for permafrost prediction in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 216, 104009 (2023).

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, (IPCC), Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (IPCC). https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/ (2021).

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, (IPCC), Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability (IPCC). https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/ (2022).

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, (IPCC), Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change (IPCC). https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/ (2022).

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, (IPCC), Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (IPCC). https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc/ (2019).

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, (IPCC), Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5 °C (IPCC). https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/ (2018).

Tipping Elements—the Achilles Heels of the Earth System (Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research). https://www.pik-potsdam.de/en/output/infodesk/tipping-elements (2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank Peijun An for contributing to the bibliometric survey. We also extend our gratitude to Wenting Hu, Shuang Liang, Bojin Yang, Yubao Qiu, Zekai Jin, Liyun Dai, Yibo Liu, Xinfeng Fan, and Yaozhi Jiang for their efforts in processing the climatic and environmental data for the three poles, and to Yanlong Guo for helping to draw Fig. 2. We express our sincere gratitude to the 163 experts who contributed their valuable insights through our online survey. X.L., Y.R., M.F., T.C., J.S., and B.C. is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41988101).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L., H.G., X.S., and G.C. conceptualized the manuscript. X.S. and T.C. carried out the bibliometric survey. Y.R., M.F., and B.C. quantified the teleconnection effects of polar regions in achieving SDGs. T.C., X.W.L., L.W., A.D., and D.S. assisted with data interpretation. R.J., J.S., and J.D. assisted with creating figures. X.L., H.G., G.C., X.S., Y.R., M.F., T.C., X.W.L., L.W., A.D., D.S., D.C., R.J., J.D., J.S., and B.C. contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Steffen Noe, Lars Kullerud, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Guo, H., Cheng, G. et al. Polar regions are critical in achieving global sustainable development goals. Nat Commun 16, 3879 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59178-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59178-3

This article is cited by

-

Accurate AQI forecasting in a high-altitude city using a simulated CVOCA-BiLSTM hybrid model: a case study of Lhasa, Tibet

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Multiscale processes in polar oceans and their climate and ecological implications

Acta Oceanologica Sinica (2025)