Abstract

The vast and complicated many-qubit state space forbids us to comprehensively capture the dynamics of modern quantum computers via classical simulations or quantum tomography. Recent progress in quantum learning theory prompts a crucial question: can linear properties of a many-qubit circuit with d tunable RZ gates and G − d Clifford gates be efficiently learned from measurement data generated by varying classical inputs? In this work, we prove that the sample complexity scaling linearly in d is required to achieve a small prediction error, while the corresponding computational complexity may scale exponentially in d. To address this challenge, we propose a kernel-based method leveraging classical shadows and truncated trigonometric expansions, enabling a controllable trade-off between prediction accuracy and computational overhead. Our results advance two crucial realms in quantum computation: the exploration of quantum algorithms with practical utilities and learning-based quantum system certification. We conduct numerical simulations to validate our proposals across diverse scenarios, encompassing quantum information processing protocols, Hamiltonian simulation, and variational quantum algorithms up to 60 qubits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Advancing efficient methodologies to characterize the behavior of quantum computers is an endless pursuit in quantum science, with pivotal outcomes contributing to designing improved quantum devices and identifying computational merits. In this context, quantum tomography and classical simulators have been two standard approaches. Quantum tomography, spanning state1, process2,3, and shadow tomography4,5, provides concrete ways to benchmark current quantum computers. Classical simulators, transitioning from state-vector simulation to tensor network methods6,7,8,9 and Clifford-based simulators10,11,12, not only facilitate the design of quantum algorithms without direct access to quantum resources13 but also push the boundaries to unlock practical utilities14. Despite their advancements, (shadow) tomography-based methods are quantum resource-intensive, necessitating extensive interactive access to quantum computers, and classical simulators are confined to handling specific classes of quantum states. Accordingly, there is a pressing need for innovative approaches to effectively uncover the dynamics of modern quantum computers with hundreds or thousands of qubits15,16.

Machine learning (ML) is fueling a new paradigm for comprehending and reinforcing quantum computing17. This hybrid approach, distinct from prior purely classical or quantum methods, synergizes the power of classical learners and quantum computers. Concisely, the process starts by collecting samples from target quantum devices to train a classical learner, which is then used to predict unseen data from the same distribution, either with minimal quantum resources or purely classically. Empirical studies have showcased the superiority of ML compared to traditional methods in many substantial tasks, such as real-time feedback control of quantum systems18,19,20,21, correlations and entanglement quantification22,23,24, and enhancement of variational quantum algorithms (VQAs)25,26,27.

Despite their empirical successes, the theoretical foundation of these ML-based algorithms has far-reaching consequences, where rigorous performance guarantees or scaling behaviors remain unknown. A critical yet unexplored question in the field is: Is there a provably efficient ML model that can predict the dynamics of many-qubit bounded-gate quantum circuits?

The focus on the bounded-gate quantum circuits stems from the facts that many interested states in nature often exhibit bounded gate complexity and this has broad applications in VQAs28 and system certification29. Given the offline nature of the inference stage, any advancements in this area could significantly reduce the quantum resource overhead, which is especially desirable given their scarcity.

Here we answer the above question affirmatively by exploring a specific class of quantum circuits that has broad applications in quantum computing. Particularly, this class of N-qubit circuits consists of an arbitrary initial state, a bounded-gate circuit composed of d tunable RZ gates and G−d Clifford gates, where the dynamics refer to linear properties of the resulting state measured by the operator O. Our first main result uncovers that (i) with high probability, \(\widetilde{\Omega }(\frac{(1-\epsilon )d}{\epsilon T})\, \le \, n \, \le \, \widetilde{{\mathcal{O}}}(\frac{{B}^{2}d+{B}^{2}NG}{{\epsilon }^{2}})\) training examples are sufficient and necessary for a classical learner to achieve an ϵ-prediction error on average, where B refers to the bounded norm of O and T is the number of incoherent measurements; (ii) there exists a class of G-bounded-gate quantum circuits that no polynomial runtime algorithms can predict their outputs within an ϵ-prediction error. These results deepen our understanding of the learnability of bounded-gate quantum circuits with classical learners, whereas ref. 30 focuses on quantum learners. Furthermore, the achieved findings invoke the necessity of developing a learning algorithm capable of addressing the exponential gap between sample efficiency and computational complexity.

To address this challenge, we further utilize the concepts of classical shadow31 and trigonometric expansion to design a kernel-based ML model that effectively balances prediction accuracy with computational demands. We prove that when the classical inputs are sampled from the uniform distribution, with high probability, the runtime and memory cost of the proposed ML model is no larger than \(\widetilde{{\mathcal{O}}}(TN{B}^{2}c/\epsilon )\) for a large constant c to achieve an ϵ prediction error in many practical scenarios. Our proposed algorithm paves a new way of predicting the dynamics of many-qubit quantum circuits in a provably efficient and resource-saving manner.

Results

Problem setup

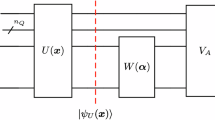

We define the state space associated with an N-qubit bounded-gate quantum circuit as

where ρ0 denotes an N-qubit state and U(x) refers to the bounded-gate quantum circuit depending on the classical input x with d dimensions. Due to the universality of Clifford (abbreviated as CI) gates with RZ gates32, an N-qubit U(x) can always be expressed as

where d is the number of RZ gates, and ue refers to the unitary composed of CI gates and the identity gate \({{\mathbb{I}}}_{2}\) with CI = {H, S, CNOT}. We denote the total number of gates and CI gates in U(x) as G and G−d, respectively. When ρ(x) is measured by a known observable O, its incoherent dynamics are described by the mean-value space, i.e., f(x, O) = Tr(ρ(x)O) with x ∈ [−π, π]d. This formalism encompasses diverse tasks in quantum computing, e.g., VQAs28, numerous applications of shadow estimation33, and quantum system certification29 (see Supplementary Material (SM) A for the elaboration).

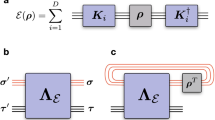

The purpose of most classical learners is to obtain a learning model h(x, O) to predict f(x, O). The general paradigm is shown in Fig. 1a. To accommodate the constraints of modern quantum devices, the training data are exclusively gathered by incoherent measurements. As such, the classical learner feeds x into the quantum circuit and receives \({\tilde{f}}_{T}({\boldsymbol{x}},O)\), as the estimation of f(x, O) incurred by T finite shots. By repeating this procedure with varied inputs, the classical learner constructs a training dataset \({\mathcal{T}}={\{{{\boldsymbol{x}}}^{(i)},{\tilde{f}}_{T}({\boldsymbol{x}},O)\}}_{i=1}^{n}\). Besides, the classical learner is kept unaware of the circuit layout details, except for the gate count G and the dimension of classical inputs d. Last, the inferred model h(x, O) should be offline, where the predictions for new inputs x is performed solely on the classical side. Given the scarcity of quantum computers, the offline property of h(x, O) significantly reduces the inference cost for studying incoherent dynamics compared to quantum learners, such as VQAs34,35.

a The visualization of learning bounded-gate quantum circuits with incoherent measurements. Given a circuit composed of G−d Clifford gates and d RZ gates, a classical learner feeds n classical inputs, i.e., n tuples of the varied angles of RZ gates, to the quantum device and collects the relevant measured results as data labels. The collected n labeled data are used to train a prediction model h that can perform purely classical inference to predict the linear properties of the generated state over new input x, i.e., Tr(ρ(x)O) with O being an observable sampled from a prior distribution, can be accurately estimated. Following conventions, the interaction between the learner and the system is restrictive, in which the learner can only access the quantum computer via incoherent measurements with finite shots. b The proposed kernel-based ml model consists of two steps. First, the learner collects the training dataset, i.e., n labeled data points via classical shadow. Then, the learner applies shadow estimation and the trigonometric monomial expansion to the collected training dataset to obtain efficient classical representations, where any new input of the explored quantum circuits can be efficiently predicted offline.

According to the above paradigm, the concept class of the mean-value space of a bounded-gate circuit is

where x ∈ [−π, π]d and Arc(U, d, G) refers to the set of all possible gate arrangements consisting of d RZ gates and G−d CI gates. The hardness of learning \({\mathcal{F}}\) by classical learners is explored by separately assessing the required sample complexity and runtime complexity of training a classical model h(x, O) that attains a low average prediction error with f(x, O). Mathematically, the average performance of the learner is expected to satisfy

where the classical input x is sampled from the distribution \({{\mathbb{D}}}_{{\mathcal{X}}}\). Here we suppose O consists of q local observables with a B-bounded norm, i.e., \(O=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i=1}^{q}{O}_{i}\) and ∑l∥Oi∥∞≤B, and the maximum locality of {Oi} is K. Learnability of bounded-gate quantum circuits. The following theorem demonstrates the learnability of \({\mathcal{F}}\) in Eq. (3), where the formal statement and the proof are presented in SM B-E (see Methods for the proof sketch).

Theorem 1

(informal) Following notations in Eq. (3), let \({\mathcal{T}}={\{{{\boldsymbol{x}}}^{(i)},{\tilde{f}}_{T}({{\boldsymbol{x}}}^{(i)})\}}_{i=1}^{n}\) be a dataset containing n training examples with x(i) ∈ [−π, π]d and \({\tilde{f}}_{T}({{\boldsymbol{x}}}^{(i)})\) being the estimation of f(x(i), O) using T incoherent measurements with \(T\le (N\log 2)/\epsilon\). Then, the training data size

is sufficient and necessary to achieve Eq. (4) with high probability. However, unless \({\mathsf{BQP}}\subseteq {\mathsf{P/poly}}\), there exists a class of G-bounded-gate quantum circuits that no algorithm can achieve Eq. (4) in polynomial time.

The exponential separation in terms of the sample and computational complexities underscores the non-trivial nature of learning the incoherent dynamics of bounded-gate quantum circuits. While the matched upper and lower bounds in Eq. (5) indicate that a linear number of training examples with d is sufficient and necessary to guarantee a satisfactory prediction accuracy, the derived exponential runtime cost hints that identifying these training examples may be computationally hard. Note that the upper bound does not depend non-trivially on T, so we omit it. Besides, an interesting future research direction is to explore novel techniques to match the factors N, B, and G in the lower and upper bounds, whereas such deviations do not affect our key results.

These results enrich quantum learning theory36,37, especially for the learnability of bounded-gate quantum circuits. Ref. 30 exhibits that for a quantum learner, reconstructing quantum states and unitaries with bounded-gate complexity is sample-efficient but computationally demanding. While Theorem 1 shows a similar trend, the varied learning settings (quantum learner vs. classical learner) and different tasks suggest that the implications and proof techniques in these two studies are inherently different. As detailed in SM J, these two works are complementary, which collectively reveal the capabilities and limitations of learning bounded-gate quantum circuits.

A provably efficient protocol to learn \({\mathcal{F}}\). The exponential separation of the sample and computational complexity pinpoints the importance of crafting provably efficient algorithms to learn \({\mathcal{F}}\) in Eq. (3). To address this issue, here we devise a kernel-based ML protocol adept at balancing the average prediction error ϵ and the computational complexity, making a transition from exponential to polynomial scaling with d when \({{\mathbb{D}}}_{{\mathcal{X}}}\) is restricted to be the uniform distribution, i.e., x ~ [−π, π]d.

Our proposal, as depicted in Fig. 1b, contains two steps: (i) Collect training data from the exploited quantum device; (ii) Construct the learning model and use it to predict new inputs. In Step (i), the learner feeds different x(i) ∈ [−π, π]d to the circuit and collects classical information of ρ(x(i)) under Pauli-based classical shadow with T snapshots, denoted by \({\tilde{\rho }}_{T}({{\boldsymbol{x}}}^{(i)})\). In this way, the learner constructs the training dataset \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\mathsf{s}}}={\{{{\boldsymbol{x}}}^{(i)}\to {\tilde{\rho }}_{T}({{\boldsymbol{x}}}^{(i)})\}}_{i=1}^{n}\) with n training examples. Then, in Step (ii), the learner utilizes \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\mathsf{s}}}\) to build a kernel-based ML model \({h}_{{\mathsf{s}}}\), i.e., given a new input x, its prediction yields

where \(g({{\boldsymbol{x}}}^{(i)},O)=\,\text{Tr}\,({\tilde{\rho }}_{T}({{\boldsymbol{x}}}^{(i)})O)\) refers to the shadow estimation of Tr( ρ(x(i))O), κΛ(x, x(i)) is the truncated trigonometric monomial kernel with

and Φω(x) with ω ∈ {0, 1, −1}d is the trigonometric monomial basis with values

A distinctive aspect of our proposal is its capability to predict the incoherent dynamics Tr(ρ(x)O) across various O purely on the classical side. This is achieved by storing the shadow information \(\{{\tilde{\rho }}_{T}({{\boldsymbol{x}}}^{(i)})\}\) into the classical memory, where the shadow estimation {g(x(i), O)} for different {O} can be efficiently processed through classical post-processing (refer to Method for details).

With the full expansion as Λ = d, the cardinality of the frequency set {ω} in Eq. (7) is 3d, impeding the computational efficiency of our proposal when the number of RZ gates becomes large. To remedy this, here we adopt a judicious frequency truncation to strike a balance between prediction error and computational complexity. Define the truncated frequency set as \({\mathfrak{C}}(\Lambda )=\{{\boldsymbol{\omega }}| {\boldsymbol{\omega }}\in {\{0,\pm 1\}}^{d},\,s.t.\,\parallel {\boldsymbol{\omega }}{\parallel }_{0}\le \Lambda \}\). The subsequent theorem provides a provable guarantee for this tradeoff relation, with the formal description and proof deferred to SM F.

Theorem 2

(Informal) Following notations in Eqs. (3)–(6), suppose \({{\mathbb{E}}}_{{\boldsymbol{x}} \sim {[-\pi,\pi ]}^{d}}\parallel {\nabla }_{{\boldsymbol{x}}}\,\text{Tr}\,(\rho ({\boldsymbol{x}})O){\parallel }_{2}^{2}\le C\). When the frequency is truncated to Λ = 4C/ϵ and the number of training examples is \(n=| {\mathfrak{C}}(\Lambda )| 2{B}^{2}{9}^{K}{\epsilon }^{-1}\log (2| {\mathfrak{C}}(\Lambda )| /\delta )\), even for T = 1 snapshot per training example, with probability at least 1−δ,

The obtained results reveal that both sample and computational complexities of \({h}_{{\mathsf{s}}}\) are predominantly influenced by the cardinality of \({\mathfrak{C}}(\Lambda )\), or equivalently, the quantity C as Λ = 4C/ϵ. That is, a polynomial scaling of \(| {\mathfrak{C}}(\Lambda )|\) with N and d can ensure both a polynomial runtime cost to obtain κΛ(x, x(i))g(x(i), O) and a polynomial sample complexity n, leading to an overall polynomial computational complexity of our proposal (see Methods and SM G for details). In contrast, for an unbounded C such that \(| {\mathfrak{C}}(\Lambda )|\) exponentially scales with the number of RZ gates d, the computational overhead of \({h}_{{\mathsf{s}}}\) becomes prohibitive for a large d, aligning with the findings from Theorem 1.

We next underscore that in many practical scenarios, the quantity C can be effectively bounded, allowing the proposed ML model to serve as a valuable complement to quantum tomography and classical simulations in comprehending quantum devices (See SM K for heuristic evidence). One scenario involves characterizing near-Clifford quantum circuits consisting of many CI gates and few non-Clifford gates, which find applications in quantum error correction38,39 and efficient implementation of approximate t-designs40. In this context, adopting the full expansion with Λ = d is computationally efficient, as \(| {\mathfrak{C}}(d)| \sim O(N)\). Meanwhile, when focused on a specific class of quantum circuits described as CI + RZ with a fixed layout, our model surpasses classical simulation methods41,42 in runtime complexity by eliminating the dependence on the number of Clifford gates G−d.

Another scenario involves the advancement of VQAs28,43,44, a leading candidate for leveraging near-term quantum computers for practical utility in ML45, quantum chemistry, and combinatorial optimization46. Recent studies have shown that in numerous VQAs, the gradients norm of trainable parameters yields C ≤ 1/poly(N)47,48,49,50 or C ≤ 1/exp(N), a.k.a, barren plateaus51,52,53,54. These insights, coupled with the results in Theorem 2, suggest that our model can be used to pretrain VQA algorithms on the classical side to obtain effective initialization parameters before quantum computer execution, preserving access to quantum resources55,56. Theoretically, our model broadens the class of VQAs amenable to classical simulation, pushing the boundaries of achieving practical utility with VQAs57,58,59.

Last, the complexity bound in Theorem 2 hints that the locality of the observable K is another factor dominating the performance of \({h}_{{\mathsf{s}}}\). This exponential dependence arises from the use of Pauli-based classical shadow, and two potential solutions can be employed to alleviate this influence. The first solution involves adopting advanced variants of classical shadow to enhance the sample complexity bounds60,61,62,63. The second solution entails utilizing classical simulators to directly compute the quantity {Tr(ρ(x(i))O)} instead of shadow estimation {g(x(i), O)} in Eq. (6), with the sample complexity summarized in the following corollary.

Corollary 1

(Informal) Following notations in Theorem 2, when \({\{\text{Tr}(\rho ({{\boldsymbol{x}}}^{(i)})O)\}}_{i}\) are computed by classical simulators and \(n \sim \widetilde{{\mathcal{O}}}({3}^{d}{B}^{2}d/\epsilon )\), with high probability, the average prediction error is upper bounded by ϵ.

Although using the classical simulators can improve the locality of observables and remove the necessity of quantum resources, the price to pay is increasing the computational overhead and only restricting to a small constant d. Refer to SM H for the proofs, implementation details, and more discussions.

Remark

For clarity, we focus on showing how the proposed ML model applied to the bounded-gate circuits with CI and RZ gates. In SM I, we illustrate that our proposal and the relevant theoretical findings can be effectively extended to a broader context, i.e., the circuit composed of CI gates alongside parameterized multi-qubit gates generated by arbitrary Pauli strings. In SM J, we show how our proposal differs from Pauli path simulators.

Numerical results

We conduct numerical simulations on 60-qubit quantum circuits to assess the efficacy of the proposed ML model. The omitted details, as well as the demonstration of classically optimizing VQAs with smaller qubit sizes, are provided in Method and SM J.

We first use the proposed ML model to predict the properties of rotational GHZ states. Mathematically, we define an N-qubit rotational GHZ states with N = 60 as \(\left\vert \,\text{GHZ}\,({\boldsymbol{x}})\right\rangle=U({\boldsymbol{x}})({\left\vert 0\right\rangle }^{\otimes N}+{\left\vert 1\right\rangle }^{\otimes N})/\sqrt{2}\), where U(x) = RY1(x1) ⊗ RY30(x2) ⊗ RY60(x3), and the subscript j refers to applying RY gate to the j-th qubit. At the training stage, we constitute the dataset \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{s}\) containing n = 30 examples, where each example is obtained by uniformly sampling x from [−π, π]3 and applying classical shadow to \(\left\vert \,\text{GHZ}\,({\boldsymbol{x}})\right\rangle\) with the shot number T = 1000.

The first subtask is predicting a two-point correlation function, i.e., the expectation value of Cij = (XiXj + YiYj + ZiZj)/3 for each pair of qubits (i, j), at new values of x. To do so, the proposed ML model leverages \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{s}\) to form the classical representations with Λ = 3 and exploits these representations to proceed with prediction at x. Figure 2a depicts the predicted and actual values of the correlation function for a particular value of x, showing reasonable agreement. The second subtask is exploiting how the prediction error depends on the truncation value Λ, the number of training examples n, and the shot number T. Figure 2b showcases that when T = 1000 and the training data are sufficient (i.e., n ≥ 500), the root mean squared (RMS) prediction error on 10 unseen test examples is almost the same for the full expansion (i.e., Λ = 3) and the proper truncation (i.e., Λ = 2). Besides, Fig. 2c indicates that when n = 500, the prediction error on the same test examples reaches a low value for both Λ = 3 and Λ = 2 once the shot number T exceeds a threshold value (T ≥ 50). These results are consistent with our theoretical analysis.

a Two-point correlation. Exact values and ML predictions of the expectation value of the correlation function Cij = (XiXj + YiYj + ZiZj)/3 for all qubit pairs of 60-qubit GHZ states. The node’s color indicates the exact value and predicted value of the two subplots, respectively. b, c PREDICTION ERROR. Subplot (b) depicts the root mean squared (RMS) prediction error of the trained ML model with varied truncation Λ and number of training examples n. Subplot (c) shows the RMS prediction error of the trained ML model with varied truncation Λ and the shot number T. The setting Λ = 3 refers to the full expansion.

We next apply the proposed ML model to predict properties of the state evolved by a global Hamiltonian \({\mathsf{H}}={J}_{1}{\otimes }_{i=1}^{N}{Z}_{i}+\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i=1}^{N}{X}_{i}\), where J1 is a predefined constant and the qubit count is set to N = 60. The initial state is \({\left\vert 0\right\rangle }^{\otimes N}\) and U(x) is the Trotterized time evolution of \({\mathsf{H}}\). By properly selecting the evolution time at each Trotter step and J1, the Trotterized time-evolution circuit takes the form \(U({\boldsymbol{x}})=\mathop{\prod }\nolimits_{j=1}^{d}({e}^{-\imath {{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{j}{\otimes }_{i=1}^{N}{Z}_{i}}{\otimes }_{i=1}^{N}\,\text{RX}\,(\pi /3))\). We set the total number of Trotter steps as d = 1. At the training stage, we constitute the dataset \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\mathsf{s}}}\) following the same rule presented in the last simulation. The only difference is the dataset size and the shot number, which are n = 20 and T = 500. The task is predicting the magnetization with \(\left\langle \bar{Z}\right\rangle=\frac{1}{60}{\sum }_{i}\left\langle {Z}_{i}\right\rangle\).

The comparison between the exact value and the prediction with Λ = 1 (full expansion) is shown in Fig. 3a. We select 25 test examples evenly distributed across the interval [−π, π]. By increasing the number of training examples n from 10 to 20, the prediction values of the proposed ML model almost match the exact results.

a Prediction on the evolved state with d = 1. The notation n = a refers to the number of training examples used to form the classical representation as a. The y axis denotes the magnetization \(\left\langle \bar{Z}\right\rangle=\frac{1}{60}{\sum }_{i}\left\langle {Z}_{i}\right\rangle\). b Pretraining performance of the proposed ml model on a 50-qubit tfim. The inset presents the prediction error of the proposed ML model for both the ideal (solid bar) and shadowed (Hatching patterns with '/') cases, i.e., T → ∞ and T = 300. The main plot depicts the training dynamics of the proposed ML model over 500 iterations under ideal (circle markers) and shadowed (star markers) settings. The shaded areas represent the variance, while the dashed line indicates the exact ground-state energy.

We last evaluated the performance of the proposed ML model as a classical surrogate for variational quantum eigen-solver (VQE) in estimating the ground-state energy of the Transverse Field Ising Model (TFIM). The explored 50-qubit TFIM takes the form as \({\mathsf{H}}=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i=1}^{N-1}-0.2{Z}_{i}{Z}_{i+1}-0.5\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i=1}^{N}{X}_{i}\) with N = 50. The initialized state is \({\left\vert 0\right\rangle }^{\otimes 50}\) and the employed ansatz is \(U({\boldsymbol{x}})=\mathop{\prod }\nolimits_{i=1}^{N-1}\,\text{RZZ}\,({{\boldsymbol{x}}}^{(i)};i)({\otimes }_{i=1}^{N}\,\text{RX}\,({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{i+N-1})){\text{Ha}}^{\otimes N}\), where Ha refers to the Hadamard gate and RZZ(x(i); i) denotes applying RZZ gate to the i-th and i + 1-th qubits.

The pretraining process involves three steps. In the first two steps, we construct the training dataset \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\mathsf{s}}}\) by randomly sampling x ∈ [−π, π]99 from a uniform distribution and inputting these values into the ansatz U(x) to generate classical shadows. The number of trainable examples is set as n = 1500 and the snapshot for each quantum state ρ(x) has two settings, which are T = 300 (shadow case) and T → ∞ (ideal case). Once \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\mathsf{s}}}\) is collected, we move to the third step, where the proposed ML model \({h}_{{\mathsf{s}}}({\boldsymbol{x}},{\mathsf{H}})\) built on \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\mathsf{s}}}\) to pretrain VQEs. The pretraining amounts to an optimization task with \(\mathop{\min }\limits_{{\boldsymbol{x}}}{h}_{{\mathsf{s}}}({\boldsymbol{x}},{\mathsf{H}})\). The Adam optimizer is used to minimize this surrogate loss, with a learning rate of 0.01 and a total of 500 iterations. Refer to SM K for more details.

The achieved results are illustrated in Fig. 3b. The inset illustrates the prediction error between the exact result and the optimized \({h}_{{\mathsf{s}}}({\boldsymbol{x}},{\mathsf{H}})\), evaluated using 500 test examples sampled from the same data distribution as the training examples. The prediction error for both the shadow and the ideal datasets remains remarkably low, demonstrating the success of the learning process. The main plot shows the dynamics of the proposed ML model during the minimization of the surrogate loss. For both the noisy and ideal cases, the estimated energies after pretraining are close to the exact value.

Discussion

In this study, we prove that learning bounded-gate quantum circuits with incoherent measurements is sample-efficient but computationally hard. Furthermore, we devise a provably efficient ML algorithm to predict the incoherent dynamics of bounded-gate quantum circuits, transitioning from exponential to polynomial scaling. The achieved results provide both theoretical insights and practical applications, demonstrating the efficacy of ML in comprehending and advancing quantum computing.

Several crucial research avenues merit further exploration. First, our study addresses the scenario of noiseless quantum operations. An important and promising area for future investigation is the development of provably efficient learning algorithms capable of predicting the incoherent dynamics of noisy bounded-gate quantum circuits64,65,66. Secondly, it is vital to extend our theoretical results from average-case scenarios to worst-case scenarios, wherein classical input can be sampled from arbitrary distributions rather than solely from the uniform distribution67,68. Such extensions would deepen our understanding of the capabilities and limitations of employing ML to comprehend quantum circuits. Moreover, there exists ample opportunity to enhance our proposed learning algorithm by exploring alternative kernel methods, such as the positive good kernels69 adopted in ref. 70. In addition, independent of this work, a crucial research topic is understanding the hardness of classically simulating the incoherent dynamics of bounded-gate quantum circuits with simple input quantum states in terms of the averaged prediction error. Last, it would be intriguing to explore whether deep learning algorithms71 can achieve provably improved prediction performance and efficiency for specific classes of quantum circuits.

Methods

Computational efficiency

The proposed ML model, as mentioned in the main text, is not only sample efficient but also computationally efficient when the quantity C is well bounded. Here we briefly discuss why the proposed ML model is computationally efficient and defer the detailed analysis in SM G.

Recall that our proposal consists of two stages: training dataset collection and model inference. As a result, to demonstrate the efficiency of our proposal, it is equivalent to exhibiting the computational efficiency at each stage.

Training dataset collection

This stage amounts to loading the collected training dataset \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{{\mathsf{s}}}={\{{{\boldsymbol{x}}}^{(i)},{\tilde{\rho }}_{T}({{\boldsymbol{x}}}^{(i)})\}}_{i=1}^{n}\) into the classical memory. For the classical input controls \({\{{{\boldsymbol{x}}}^{(i)}\}}_{i=1}^{n}\), \({\mathcal{O}}(dn)\) the computation cost is sufficient. For the classical shadow \({\{{\tilde{\rho }}_{T}({{\boldsymbol{x}}}^{(i)})\}}_{i=1}^{n}\), the required computational cost is \({\mathcal{O}}(nNT)\), where T refers to the number of snapshots. According to Theorem 2, the number of training examples n polynomially scales with N and d for an appropriate C. Taken together, this stage is computationally efficient when C is well bounded.

Inference stage

Following the definition of our model in Eq. (6), its inference involves summing over the assessment of each training example \(({{\boldsymbol{x}}}^{(i)},{\tilde{\rho }}_{T}({{\boldsymbol{x}}}^{(i)}))\), and the evaluation of each training example is composed of two components, i.e., the shadow estimation \(\,\text{Tr}\,(O{\tilde{\rho }}_{T}({{\boldsymbol{x}}}^{(i)}))\) and the kernel function calculation κΛ(x, x(i)).

As for the Pauli-based shadow estimation, the computation of each \(\,\text{Tr}\,({O}_{i}{\tilde{\rho }}_{T}({{\boldsymbol{x}}}^{(i)}))\) can be completed in \({\mathcal{O}}(T)\) time after storing the classical shadow in the classical memory. In other words, the computation can be completed in \({\mathcal{O}}(Tq)\) runtime \(O=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i=1}^{q}{O}_{i}\). As for the kernel function calculation, it can be completed at \({\mathcal{O}}(| {\mathfrak{C}}(4C/\epsilon )| )\) runtime.

Taken together, the inference stage is also computationally efficient when C is well bounded, where the required computational cost is \({\mathcal{O}}(n(Tq+| {\mathfrak{C}}(4C/\epsilon )| ))\).

Proof sketch of theorem 1

The proof of Theorem 1 is reached by separately analyzing the lower and upper bounds of the sample complexity, and the lower bound of the runtime complexity.

Sample complexity. We separately analyze the lower and upper bounds of the sample complexity. As for the lower bound, we design a specific learning task in which the concept class is \(\hat{{\mathcal{F}}}=\{{f}_{{\boldsymbol{a}}}({\boldsymbol{x}})| {\boldsymbol{a}}\in {\{0,1\}}^{d},{\boldsymbol{x}} \sim {[-\pi,\pi ]}^{d}\}\) with \(f({\boldsymbol{x}})=\sqrt{2\epsilon }B\cos (\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i=1}^{d}(1-{{\boldsymbol{a}}}_{i}){{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{i})\). We demonstrate that such concepts can be effectively prepared by a two-qubit circuit with d RZ gates and G−d Clifford gates. We then harness Fano’s lemma to establish the lower bound of the sample complexity when learning \(\hat{{\mathcal{F}}}\), i.e., \(\Pr [{{\boldsymbol{a}}}^{*}\,\ne \, \bar{{\boldsymbol{a}}}]\ge 1-\frac{I({{\boldsymbol{a}}}^{*};\bar{{\boldsymbol{a}}})+\log 2}{\log | \hat{{\mathcal{F}}}| }\) with a * being the target concept and \(\bar{{\boldsymbol{a}}}\) being the inferred concept. Specifically, we independently quantify the upper bound of the mutual information \(I({{\boldsymbol{a}}}^{*};\bar{{\boldsymbol{a}}})\) and the cardinality of the concept class \(| \hat{{\mathcal{F}}}|\). Supported by the results of information theory, we obtain \(I({{\boldsymbol{a}}}^{*};\overline{a})\le n\cdot \min \{\frac{\epsilon T}{1-\epsilon },N\log 2\}\), independent of the gate count d or G. Meanwhile, we have \(| \hat{{\mathcal{F}}}|={2}^{d}\). Taken together, we reach the lower bound.

As for the upper bound, we leverage hypothesis testing to reformulate its derivation as a task of quantifying the cardinality of the packing net for the concept class \({\mathcal{F}}\). Particularly, the cardinality is determined by all possible arrangements of d RZ gates and G−d Clifford gates across N-qubit wires, which is inherently a combinatorial problem. Through analysis, we obtain that the upper bound of the packing number of \({\mathcal{F}}\) is \(\left(\begin{array}{c}G\\ d\end{array}\right)\cdot {N}^{d}\cdot {3}^{G-d}\cdot {\left(\begin{array}{c}N\\ 2\end{array}\right)}^{G-d}\). Then, according to the result of statistical learning theory, the required sample complexity logarithmically depends on this cardinality, leading to the linear scaling with d and G.

Runtime complexity. To demonstrate the computational hardness, we leverage results from the \({\mathsf{BQP}}\) complexity class. Specifically, we construct a tailored concept class \({\mathcal{F}}\) that incorporates a concept f * realized by the \({\mathsf{BQP}}\) circuit. Consequently, if an efficient classical learner were to exist for this task, it would imply that any \({\mathsf{BQP}}\) language could be decided in \({\mathsf{P/poly}}\)-a scenario that is widely considered implausible.

The implementation of f * follows a similar manner to ref. 72. Let \({\mathsf{L}}\) be an arbitrary \({\mathsf{BQP}}\) language. Since \({\mathsf{L}}\in {\mathsf{BQP}}\), there exists a corresponding quantum circuit U * which decides input bitstrings x ∈ {0, 1}N correctly on average with respect to the data distribution. In particular, define \({O}^{{\prime} }={{\rm{Z}}}_{1}\otimes {{\mathbb{I}}}_{{2}^{N-1}}\) as the observable, which measures the Pauli-Z operator on the first qubit. The target concept f * is defined as \({f}^{*}({\boldsymbol{x}},{O}^{{\prime} })=\,\text{Tr}\,({O}^{{\prime} }{\rho }^{*}({\boldsymbol{x}}))\) with \(\rho={U}^{*}\left\vert {\boldsymbol{x}}\right\rangle \left\langle {\boldsymbol{x}}\right\rangle {U}^{*\dagger }\). The result \({f}^{*}({\boldsymbol{x}},{O}^{{\prime} })\), whether positive or negative, determines the decision regarding whether the input bitstrings x belongs to \({\mathsf{L}}\) or not. As such, we connect the problem of learning the mean-value space of bounded-gate circuits with complexity theory.

The remaining step to complete the proof involves demonstrating that the quantum state ρ *(x) can be efficiently prepared using RZ and Clifford gates. Taken together, this completes the proof.

Proof sketch of theorem 2

We first exhibit that the expected risk is upper bounded by the truncation error Err1 and the estimation error Err2 with \({{\mathbb{E}}}_{{\boldsymbol{x}}}| {h}_{{\mathsf{s}}}({\boldsymbol{x}},O)-f(\rho ({\boldsymbol{x}}),O){| }^{2}\le (\sqrt{{\text{Err}}_{1}}+\sqrt{{\text{Err}}_{2}})\), where \({\text{Err}}_{1}={{\mathbb{E}}}_{{\boldsymbol{x}}}\left[| \,\text{Tr}\,\left(O{\rho }_{\Lambda }({\boldsymbol{x}})\right)-\,\text{Tr}\,(O\rho ({\boldsymbol{x}})){| }^{2}\right]\,{{\rm{Err}}}_{2}={{\mathbb{E}}}_{{\boldsymbol{x}}}[| \,\text{Tr}\,\left(O{\rho }_{\Lambda }({\boldsymbol{x}})\right)-{h}_{{\mathsf{s}}}({\boldsymbol{x}},O){| }^{2}]\). Here we expand the explored state under the trigonometric monomial basis in Eq. (8) with \({\rho }_{\Lambda }={\sum }_{{\boldsymbol{\omega }}\in {\mathfrak{C}}(\Lambda )}{\Phi }_{{\boldsymbol{\omega }}}({\boldsymbol{x}})\) and ρ = ρd. Intuitively, Err1 measures the discrepancy between the target state and the truncated state, and Err2 measures the difference between the prediction and the estimation of the truncated state.

The upper bound of Err1 is established by connecting with the gradient norm of the expectation value Tr(ρ(x)O). More concisely, supported by the results of Fourier analysis, we prove that Err1 is upper bounded by \({{\mathbb{E}}}_{{\boldsymbol{x}} \sim {[-\pi,\pi ]}^{d}}\parallel {\nabla }_{{\boldsymbol{x}}}\,\text{Tr}\,(\rho ({\boldsymbol{x}})O){\parallel }_{2}^{2}/\Lambda\). Then, under the assumption \({{\mathbb{E}}}_{{\boldsymbol{x}} \sim {[-\pi,\pi ]}^{d}}\parallel {\nabla }_{{\boldsymbol{x}}}\,\text{Tr}\,(\rho ({\boldsymbol{x}})O){\parallel }_{2}^{2}\le C\), we obtain Err1≤C/Λ. The upper bound of Err2 is obtained by exploiting the results of Pauli-based shadow estimation. Particularly, we first prove that \({h}_{{\mathsf{s}}}({\boldsymbol{x}},O)\) is an unbiased estimator of ρΛ(x). Then we make use of the results of Pauli-based shadow to quantify the estimation error, i.e., \({\text{Err}}_{2}\le \tilde{{\mathcal{O}}}(| {\mathfrak{C}}(\Lambda )| \frac{1}{2n}{B}^{2}{9}^{K})\). Taken together, we reach the complexity bound in Theorem 2.

Code implementation and simulation details

All numerical simulations in this work are conducted using Python, primarily leveraging the Pennylane and PastaQ libraries. For small qubit sizes with N ≤ 20, we use Pennylane to generate training examples and make predictions for new inputs. For larger qubit sizes with N > 20, we utilize PastaQ to generate training data and Numpy to handle post-processing and new input predictions.

The code implementation of our proposal proceeds as follows. The collected shadow states are alternately stored in the HDF5 binary data format and the standard binary file format in NumPy. For instance, when N = 60 and T = 5000, the file size of each shadow state is 14.4 MB. Utilizing advanced storage strategies can further reduce memory costs. The representation used in the kernel calculation is obtained via an iterative approach. In particular, we iteratively compute a set of representations {Φω} satisfying ∥ω∥0 = λ and λ ≤ Λ. Given a specified λ, we identify the indices with nonzero values via a combinatoric iterator and compute the corresponding representations according to Eq. (7). It is noteworthy that adopting distributed computing strategies can further improve the computational efficiency of our method.

In the task of predicting the two-point correlation of rotational GHZ states (i.e., Fig. 2a), the test value used in the prediction stage is x = [1.234, −1.344, −1.716]. All diagonal elements in the correlation matrix are set as 1.

Data availability

The data generated and analyzed during the current study are publicly available at the following repositories: Github: https://github.com/yuxuan-du/Efficient_Predicting_Bounded_Gate_QC; Google Drive: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1lzDyZ7d3Wsm2ncFMGhkUjJg7HrI3ouXy. These datasets support the findings of the study and include all data necessary to reproduce the results presented in the main text and supplementary materials.

Code availability

The code used in this study is available at the Github repository https://github.com/yuxuan-du/Efficient_Predicting_Bounded_Gate_QC.

References

Leonhardt, U. Quantum-state tomography and discrete Wigner function. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 4101 (1995).

Altepeter, J. B. et al. Ancilla-assisted quantum process tomography. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 193601 (2003).

Mohseni, M., Rezakhani, A. T. & Lidar, D. A. Quantum-process tomography: resource analysis of different strategies. Phys. Rev. A 77, 032322 (2008).

Aaronson, S. The learnability of quantum states. Proc. R. Soc. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 463, 3089–3114 (2007).

Aaronson, Scott. Shadow tomography of quantum states. In: Proceedings of the 50th annual ACM SIGACT symposium on theory of computing, 325–338 (2018).

Markov, I. L. & Shi, Y. Simulating quantum computation by contracting tensor networks. SIAM J. Comput. 38, 963–981 (2008).

Villalonga, B. et al. A flexible high-performance simulator for verifying and benchmarking quantum circuits implemented on real hardware. npj Quantum Inf. 5, 86 (2019).

Cirac, J. I., Perez-Garcia, D., Schuch, N. & Verstraete, F. Matrix product states and projected entangled pair states: concepts, symmetries, theorems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 93, 045003 (2021).

Pan, F. & Zhang, P. Simulation of quantum circuits using the big-batch tensor network method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 030501 (2022).

Bravyi, S. & Gosset, D. Improved classical simulation of quantum circuits dominated by clifford gates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 250501 (2016).

Bravyi, S. et al. Simulation of quantum circuits by low-rank stabilizer decompositions. Quantum 3, 181 (2019).

Begušić, T., Gray, J. & Chan, GarnetKin-Lic Fast and converged classical simulations of evidence for the utility of quantum computing before fault tolerance. Sci. Adv. 10, eadk4321 (2024).

Chen, J. et al. Quantum Fourier transform has small entanglement. PRX Quantum 4, 040318 (2023).

Arute, F. et al. Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor. Nature 574, 505–510 (2019).

Kim, Y. et al. Evidence for the utility of quantum computing before fault tolerance. Nature 618, 500–505 (2023).

Bluvstein, D. et al. Logical quantum processor based on reconfigurable atom arrays. Nature 626, 58–65 (2023).

Gebhart, V. et al. Learning quantum systems. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 141–156 (2023).

Torlai, G. & Melko, R. G. Neural decoder for topological codes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 030501 (2017).

Zeng, Y., Zhou, Zheng-Yang, Rinaldi, E., Gneiting, C. & Nori, F. Approximate autonomous quantum error correction with reinforcement learning. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 050601 (2023).

Dehghani, H., Lavasani, A., Hafezi, M. & Gullans, M. J. Neural-network decoders for measurement induced phase transitions. Nat. Commun. 14, 2918 (2023).

Reuer, K. et al. Realizing a deep reinforcement learning agent for real-time quantum feedback. Nat. Commun. 14, 7138 (2023).

Canabarro, A., Brito, Samuraí & Chaves, R. Machine learning nonlocal correlations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 200401 (2019).

Chen, Z., Lin, X., & Wei, Z. Certifying unknown genuine multipartite entanglement by neural networks. Quantum Sci. Technol. 8, 035029 (2022).

Koutny`, D. et al. Deep learning of quantum entanglement from incomplete measurements. Sci. Adv. 9, eadd7131 (2023).

Bennewitz, E. R., Hopfmueller, F., Kulchytskyy, B., Carrasquilla, J. & Ronagh, P. Neural error mitigation of near-term quantum simulations. Nat. Mach. Intell. 4, 618–624 (2022).

Zhang, Shi-Xin et al. Variational quantum-neural hybrid eigensolver. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 120502 (2022).

Wei, V., Coish, W. A., Ronagh, P. & Muschik, C. A. Neural-shadow quantum state tomography. Phys. Rev. Res. 6, 023250 (2024).

Cerezo, M. et al. Variational quantum algorithms. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 625–644 (2021).

Eisert, J. et al. Quantum certification and benchmarking. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2, 382–390 (2020).

Zhao, H. et al. Learning quantum states and unitaries of bounded gate complexity. PRX Quantum 5, 040306 (2024).

Huang, H.-Y., Kueng, R. & Preskill, J. Predicting many properties of a quantum system from very few measurements. Nat. Phys. 16, 1050–1057 (2020).

Ross, N.J. & Selinger, P. Optimal ancilla-free clifford+ t approximation of z-rotations. Quantum Inf. Comput. 16, 11–12 (2014).

Elben, A. et al. The randomized measurement toolbox. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 9–24 (2022).

Jerbi, S. et al. The power and limitations of learning quantum dynamics incoherently. Preprint at: arXiv:2303.12834 (2023).

Gibbs, J. et al. Dynamical simulation via quantum machine learning with provable generalization. Phys. Rev. Res. 6, 013241 (2024).

Anshu, A. & Arunachalam, S. A survey on the complexity of learning quantum states. Nat. Rev. Phys. 6, 59–69 (2023).

Banchi, L., Pereira, J.L., Jose, S.T., & Simeone, O. Statistical complexity of quantum learning. Adv. Quantum Technol. 2300311, (2023).

Calderbank, A. R., Rains, E. M., Shor, P. W. & Sloane, NeilJ. A. Quantum error correction and orthogonal geometry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 405 (1997).

Terhal, B. M. Quantum error correction for quantum memories. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 307 (2015).

40. Haferkamp, J. et al. Efficient unitary designs with a system-size independent number of non-Clifford gates. Commun. Math. Phys. 397, 995–1041 (2023).

Aaronson, S. & Gottesman, D. Improved simulation of stabilizer circuits. Phys. Rev. A 70, 052328 (2004).

Lai, Ching-Yi & Cheng, Hao-Chung Learning quantum circuits of some t gates. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 68, 3951–3964 (2022).

Tian, J. et al. Recent advances for quantum neural networks in generative learning. In: IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence (2023).

Bharti, K. et al. Noisy intermediate-scale quantum algorithms. Rev. Mod. Phys. 94, 015004 (2022).

Li, W. & Deng, D.-L. Recent advances for quantum classifiers. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 65, 1–23 (2022).

Farhi, E. & Harrow, A.W. Quantum supremacy through the quantum approximate optimization algorithm. Preprint at: arXiv:1602.07674 (2016).

Pesah, A. et al. Absence of barren plateaus in quantum convolutional neural networks. Phys. Rev. X 11, 041011 (2021).

Zhang, K., Hsieh, M.-H., Liu, L., & Tao, D. Toward trainability of deep quantum neural networks. Preprint at: arXiv:2112.15002 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Symmetric pruning in quantum neural networks. In: The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations (2023).

Larocca, M. et al. Theory of overparametrization in quantum neural networks. Nat. Comput. Sci. 3, 542–551 (2023).

McClean, J. R., Boixo, S., Smelyanskiy, V. N., Babbush, R. & Neven, H. Barren plateaus in quantum neural network training landscapes. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–6 (2018).

Cerezo, M., Sone, A., Volkoff, T., Cincio, L. & Coles, P. J. Cost function dependent barren plateaus in shallow parametrized quantum circuits. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–12 (2021).

Marrero, CarlosOrtiz, Kieferová, M. ária & Wiebe, N. Entanglement-induced barren plateaus. PRX Quantum 2, 040316 (2021).

Arrasmith, A., Holmes, Zoë, Cerezo, M. & Coles, P. J. Equivalence of quantum barren plateaus to cost concentration and narrow gorges. Quantum Sci. Technol. 7, 045015 (2022).

Dborin, J., Barratt, F., Wimalaweera, V., Wright, L. & Green, A. G. Matrix product state pre-training for quantum machine learning. Quantum Sci. Technol. 7, 035014 (2022).

Rudolph, M. S. et al. Synergistic pretraining of parametrized quantum circuits via tensor networks. Nat. Commun. 14, 8367 (2023).

Schreiber, F. J., Eisert, J. & Meyer, JohannesJakob Classical surrogates for quantum learning models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 100803 (2023).

Cerezo, M. et al. Does provable absence of barren plateaus imply classical simulability? Or, why we need to rethink variational quantum computing. Preprint at: arXiv:2312.09121 (2023).

Gan, B.Y., Huang, P.-W., Gil-Fuster, E., & Rebentrost, P. Concept learning of parameterized quantum models from limited measurements. Preprint at: arXiv:2408.05116 (2024).

Huang, H.-Y., Kueng, R. & Preskill, J. Efficient estimation of Pauli observables by derandomization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 030503 (2021).

Nguyen, H. C., Bönsel, JanLennart, Steinberg, J. & Gühne, O. Optimizing shadow tomography with generalized measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 220502 (2022).

Zhang, Q., Liu, Q. & Zhou, Y. Minimal-clifford shadow estimation by mutually unbiased bases. Phys. Rev. Appl. 21, 064001 (2024).

Vermersch, B. et al. Enhanced estimation of quantum properties with common randomized measurements. PRX Quantum 5, 010352 (2024).

Shao, Y., Wei, F., Cheng, S. & Liu, Z. Simulating noisy variational quantum algorithms: a polynomial approach. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 120603 (2024).

Fontana, E., Rudolph, M.S., Duncan, R., Rungger, I., & Cîrstoiu, C. Classical simulations of noisy variational quantum circuits. Preprint at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.05400 (2023).

Huang, H.-Y., Chen, S. & Preskill, J. Learning to predict arbitrary quantum processes. PRX Quantum 4, 040337 (2023).

Arunachalam, S. & de Wolf, R. Guest column: a survey of quantum learning theory. ACM SIGACT N. 48, 41–67 (2017).

Huang, H.-Y., Kueng, R. & Preskill, J. Information-theoretic bounds on quantum advantage in machine learning. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 190505 (2021).

Stein, E.M. & Shakarchi, R. Fourier analysis: an introduction. Vol. 1. Princeton University Press (2011).

Che, Y., Gneiting, C. & Nori, F. Exponentially improved efficient machine learning for quantum many-body states with provable guarantees. Phys. Rev. Res. 6, 033035 (2024).

Qian, Y., Du, Y., He, Z., Hsieh, M.-H. & Tao, D. Multimodal deep representation learning for quantum cross-platform verification. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 130601 (2024).

Molteni, R., Gyurik, C. & Dunjko, V. Exponential quantum advantages in learning quantum observables from classical data. Preprint at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.02027 (2024).

Acknowledgements

D.T. acknowledges support from the National Research Foundation, Singapore, under its NRF Professorship Award No. NRF-P2024-001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The project was conceived by Y.D. and D.T. Theoretical results were proved by Y.D. and M.H. Numerical simulations and analysis were performed by Y.D. All authors contributed to the write-up.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, Y., Hsieh, MH. & Tao, D. Efficient learning for linear properties of bounded-gate quantum circuits. Nat Commun 16, 3790 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59198-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59198-z