Abstract

Climate change-induced sea-level rise and associated flood risk will have major impacts on coastal regions worldwide, likely prompting millions of people to migrate elsewhere. Migration behavior is expected to be context-specific, but comparative empirical research on coastal migration under climate change is lacking. We address this gap by utilizing original survey data from coastal Argentina, France, Mozambique and the United States to research determinants of migration under different flood risk scenarios. Here we show that migration is more likely in higher-than in lower-income contexts, and that flood risk is an important driver of migration. Consistent determinants of migration across contexts include response efficacy, self-efficacy, place attachment and age, with variations between scenarios. Other factors such as climate change perceptions, migration costs, social networks, household income, and rurality are also important but context-specific. Furthermore, important trade-offs exist between migration and in-situ adaptation. These findings support policymakers in forging equitable migration pathways under climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Low-lying coastal areas are among the geographies most vulnerable to increased flood risk from climate change, as a result of sea-level rise, as well as more extreme precipitation and changes in storm patterns1,2,3,4. They also accommodate major economic centers and are highly populated; more than 10% of the global population lives in the low-elevation coastal zone, where population numbers could approach 1.4 billion people by 20605. Given its vulnerability and socioeconomic importance, an expanding literature has investigated how increased flood risk may influence migration in coastal zones. Modeling studies suggest that by the end of this century, millions of people could be on the move because of sea-level rise and associated flood risk6,7. Such migration flows would have far-reaching implications for both sending and receiving communities as well as for migrants themselves8. However, large-scale modeling exercises need to be complemented by empirical research to understand what drives migration in coastal areas9,10,11. General assumptions and linear relationships between flood risk and migration do not likely hold; migration seems instead shaped by a complex set of factors, varying across (geographical) contexts12,13,14. Besides improving projections of future migration flows, empirical understanding of who migrates and why people migrate is also critical for anticipating impacts of coastal adaptation on migration15, for creating effective and equitable migration policies13,16, and for identifying potential welfare inequalities and trapped populations17.

There is a small but growing empirical literature on drivers of migration under flood risk, finding diverging motivations for migration decisions9,13,18. However, comparability of results is hampered by the use of single case studies and different survey methodologies and timings9,19. Furthermore, previous research has focused on past flood experiences and risk, while migration and its drivers are likely to change considerably under rising future flood risk9. As a result, a solid empirical understanding of coastal migration under increased flood risk is missing, and we lack knowledge on how drivers of coastal migration are shaped by local context.

To bridge this research gap, this study analyzes migration behavior and its drivers under different scenarios of future flood risk, utilizing comparable household survey data from more than 3500 respondents in different coastal zones worldwide with diverging geographical, cultural, and socioeconomic contexts (Methods). Our case studies are situated in four different continents and represent a low-income country (Mozambique), an upper-middle-income country (Argentina), and two high-income countries (France and the United States), according to the World Bank’s income classifications20. For each country, data were collected in coastal zones vulnerable to flooding and sea-level rise. Except for the United States, all countries lack empirical survey research on migration under (increased) flood risk9,13,18.

To gauge migration under rising flood risk, we measure respondent’s migration intentions in the current situation and under three scenarios of flood risk: the occurrence of major flooding every 10 years, 5 years, and every year (Methods). These scenarios were carefully constructed to make them clear and relevant for all respondents involved, while at the same time ensuring comparability across case study locations. Although not all study areas face the same flood risk, our results present a bandwidth of how migration could evolve under changing flood risk, closer or further away in the future. Because the flood scenarios are quantitative, results can be used in modeling projections of migration under flood risk and sea-level rise11.

To understand what drives people to migrate or stay, we utilize an analytical framework based on Protection Motivation Theory (PMT)21. PMT postulates that protective behavior is shaped by threat appraisal (perceived likelihood, severity, and worry of flooding) and coping appraisal (response efficacy, self-efficacy, and response costs). Widely applied in behavioral research on in situ climate change adaptation22,23,24, PMT is similarly relevant for researching migration as a measure to reduce climate risks25,26. However, migration is a more complex and impactful decision than in situ adaptation: it can impact people’s whole livelihood, and a variety of additional factors are often secondary or primary drivers of migration12,13,27. To account for this, we extend the PMT framework with a wide set of additional explanatory variables that are hypothesized to influence migration (Methods). We employ regression techniques to estimate and quantify the effects of these explanatory variables on migration, and estimate and present results separately by country and flood risk scenario.

Results

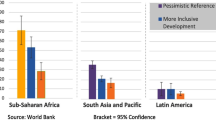

Figure 1 shows distributions of migration intentions in our four case studies at present and under the three flood scenarios. There are several notable observations. Following expectations from the literature13,28, migration patterns differ across national contexts. Migration intentions are higher in the higher-income contexts of France and the United States than in Argentina, and are lowest in Mozambique. One reason for this may be the high costs of migration, which can be borne more easily by people in higher-income countries. Another is that Argentina and Mozambique represent more collectivistic societies where attachment to local place is generally stronger, which is shown by our data (Supplementary Table 1). Conformingly, respondents in Argentina and Mozambique also report having migrated less often in the past. We also observe the universal finding that migration intentions increase under scenarios of higher flood risk, illustrating that flood risk can be a major force in shaping future migration. Migration intentions in Mozambique are lower in the 10-year flood scenario than they are at present, as such a scenario would be an improvement to current (perceived) flood risk levels. In the past 4 years, the area witnessed two major flood hazards, following cyclone Idai in 2019 and Eloise in 202129. Survey results further show that, as expected30, migration would be predominantly internal with people moving to more inland destinations (Supplementary Table 3).

Recent review studies have called for more research on the role of risk perceptions in migration decision-making13,31. Our results show that flood risk perceptions, related to the perceived likelihood and severity of flooding, generally have a positive association with migration intentions (Fig. 2; Supplementary Results). However, similar to research on in situ adaptive behavior23,24, our observed effects are weak or insignificant. Worry and climate change perceptions play in some cases a larger role. In Mozambique, flood worry is strongly positively associated with the likelihood of migration under the two highest flood scenarios. This may be due to Mozambique being the most heavily affected by floods of our four case studies, including recent devastations by cyclones Idai and Eloise, which may reinforce the effects of worry if such floods are expected to occur more regularly. Fear of climate change is an important predictor in the United States. In the United States, climate change seems a polarized topic32, exemplified by showing the lowest mean and highest standard deviation of our case studies (Supplementary Table 1). Low fear or disbelief in climate change may prompt people to underestimate the impacts of increased flood risk and subsequently influence adaptive decisions, including migration33. For France, flood worry has a surprising negative sign, and climate change fear has a positive sign in the highest flood risk scenario. A possible reason for this is that this scenario deviates most from present flood-risk conditions, especially for France, where respondents report the lowest experience and perceived likelihood of flooding of our case studies (Supplementary Table 1). As such, the influence of current worry about flooding may become obsolete, while forward-looking perceptions like climate change fear may become more important migration drivers.

Results are based on 16 regression analyses (four countries, four flooding scenarios: Source data are provided in Supplementary Results). NA signifies no observations for this category. Significant variables in the respective countries are depicted with a standing (negative effect) or running person (positive effect), as determined by two-sided t-tests. The higher the color hue, the more significant the variable is.

Except for Mozambique in the highest flood risk scenario, no strong positive relationship can be found between personal flood experience and migration. The same holds when substituting this binary measure for the number of floods experienced and the perceived severity of flood experience (results not shown). Solely when people report having experienced a loss of income due to past flooding does this, in the case of Argentina and Mozambique, have a consistent positive association with migration (Supplementary Results). Hazard experience has been found to influence risk perceptions through an availability heuristic34, and mediation analysis confirms that part of the effect of experience goes through this channel, making its overall effect more positive in most cases and significant in some (Supplementary Results). A reason for the small effect of experience may be the relatively high frequency with which floods occur in the countries we study, potentially making flood experiences less memorable as a result23. Extreme flood events have been found to influence migration in the early aftermath of flooding25. Nevertheless, the generally weak effects of past experience are in accordance with previous comparative and review studies on migration as well as in situ adaptation9,23,24, and this finding thus seems to apply more universally.

Coping appraisal represents the perceived capability (self-efficacy) and costs to migrate and its perceived effectiveness in reducing flood risk (response efficacy). In line with research on in situ climate adaptation24,35, we find that coping appraisal is a major driver of migration. In all countries, perceived effectiveness is positively associated with migration intentions under the flood scenarios, with results being significant except for France. Self-efficacy is among the strongest predictors of migration and is universally significant at the 1% level. A one-point increase on the five-point Likert scale comprising this measure leads to a 3.2–12.2 percentage point increase in the reported likelihood of migration (Supplementary Results). In contrast to the higher-income contexts of France and the United States, migration costs are a consistent deterrent to migration in Argentina and Mozambique. Its effect is strongest in the lowest-income context of Mozambique (unit-effect size up to −7 percentage points), illustrating the importance of financial considerations in this country.

Past in situ adaptation choices may influence migration decisions, for instance, by reducing risk. However, previous empirical work has mainly studied in situ adaptation and migration in isolation, and our knowledge of potential trade-offs and interdependencies between in situ adaptation and migration is, therefore, still limited9,18,28,36. Main ways for households to adapt in situ to flood risk involve taking measures to prevent water from entering homes (through elevation or dry-proofing) or taking wet-proofing measures to reduce damage in case water enters the home37 (see Supplementary Table 1 for examples of these measures).

Figure 3 shows that in all four countries, a substantial proportion of respondents have implemented these in situ adaptation measures. Uptake is highest in Argentina and Mozambique, possibly because people experience flooding more often and can rely less on the government to protect them. Additionally, a non-dualistic understanding of nature and society, which is more common in countries of the Global South, may explain the higher uptake of adaptation measures in Argentina and Mozambique. When people see themselves as part of the environment and aim to live in harmony with nature, they may prefer in situ adaptation over relocation in response to changing environmental conditions. As expected from a risk perspective, in situ adaptation reduces the reported likelihood of migration under scenarios of increased flood risk (Fig. 2), except in Argentina. Under the highest flood risk scenario, the effectiveness of in situ protection may be limited18. We observe here that solely the implementation of both water-prevention and wet-proofing measures strongly deters migration across contexts, decreasing the likelihood of migration in France, Mozambique and the United States with, respectively 6, 19, and 11 percentage points. These findings provide empirical support for the notion that adaptation choices are interdependent, indicating in situ adaptation could prevent or postpone migration under climate change13.

Network theory predicts that migration is more likely among people who have migrated before and with larger social networks outside their place of residence12,16,38. Past migration experience may facilitate future migration due to familiarity with the migration process as well as with people, cultures, and institutions elsewhere. Our results show that past migration experience is, in most cases, indeed (weakly) positively associated with migration intentions. Having a larger external social network seems to be a stronger determinant of migration, but only in France and the United States. Perhaps because of better migration opportunities in these higher-income countries, close family and friends may overrule practical/livelihood considerations in migration decisions.

Previous research has found that place attachment can be a strong deterrent of migration, and may prompt people to stay even under critical conditions39,40,41. For many people, giving up the practical, emotional, and self-identifying meaning ascribed to a place is not an easy endeavor. Our findings conform to this notion. Place attachment, measured via six statements following the Abbreviated Place Attachment Scale42 (Supplementary Table 1), is (often strongly) negatively associated with migration intentions. Results for life satisfaction are almost consistently insignificant. A reason for this may be that while life dissatisfaction could increase migration aspirations, on a psychological level, it has been associated with lower (perceived) human agency43, which could inhibit migration.

We find mixed effects for the influence of risk preferences on migration behavior. This is in contrast with previous research, which has theorized and found risk-averse people to be less likely to migrate44. Although migration can indeed be a risky endeavor, staying in a place with high (and increasing) environmental risk is also characterized by risk and uncertainty. In support of this, an interaction analysis shows that fear about climate change in combination with risk aversion increases migration in most cases (Supplementary Results). Hence, risk aversion may well work both ways in these circumstances, which would be relevant to study further in future research.

This study confirms earlier studies, which state that income, among other factors, is an important aspect of objective adaptive capacity, and which can differ from perceived capability45. Since income levels vary by country, we categorized respondents as low-, middle-, or high-income based on their self-reported income, using country-specific thresholds. The low-income group corresponds to the poorest 33%, the middle group to the middle 33%, and the high-income group to the richest 33% respondents. The effect of higher income is positive and often significant in Argentina and Mozambique (increasing the migration likelihood up to 9 percentage points), while results are mostly insignificant for France and the United States. These findings add to the significant effects found for migration costs in these countries and suggest that in countries where overall economic development is lacking, access to financial resources and opportunities shapes people’s migration decisions under climatic risk. While relatively poorer households may utilize migration to improve their condition, these findings support the idea that resource-constrained households will be less likely to move due to difficulties or inability to finance migration18.

Results for gender and education are mostly insignificant. This is in line with previous empirical research on coastal risk and migration, in which no clear relationship for these variables was found9. Significant results of “other or non-specified” for gender should be taken with caution because of the low observations. Age is significantly negatively associated with current migration intentions in all four countries. For older people, migration can be more tedious, and they may also be less willing to start a new life elsewhere. However, under the flood risk scenarios, we do not find a consistent effect for age. Seebauer and Winkler46 have found that under flood risk, older residents may be more likely to move if they feel, existing or anticipated, frailness to cope with flooding. This could possibly cancel out the initial reluctance for migration.

Rural residency does not seem to be much associated with migration in the higher-income contexts of France and the United States. In Mozambique, on the other hand, we find that migration is currently less likely among rural residents, as they greatly depend on local natural resources for their livelihoods, and this can tie them to place. However, under the highest flood risk scenario, the effect is reversed. This holds for both Mozambique and Argentina, with rural residents being respectively 18 and 10 percentage points more likely to move than (semi) urban dwellers. People may perceive that under such conditions their livelihoods, and the local natural resources on which they depend, will not be sustainable anymore12,13.

Discussion

Literature widely acknowledges that the impacts of climate change on coastal migration will be context-specific, but comparative empirical research has been missing to understand how this plays out specifically. We addressed this research gap by analyzing survey data of more than 3500 respondents in diverse coastal contexts, vulnerable to sea-level rise and flooding, in Argentina, France, Mozambique, and the United States. We find that migration intentions are higher in the high-income contexts of France and the United States than in Argentina and Mozambique. In all countries, migration intentions increase considerably under scenarios of increased flood risk. Response efficacy, self-efficacy, place attachment, and age are universal drivers of migration, although results vary among flood risk scenarios. Several drivers are context-specific. Climate change perceptions and social networks only drive migration in France and the United States. On the other hand, migration costs, household income, and rurality are drivers more specific to Argentina and Mozambique. Except for Argentina, in situ adaptation decreases the propensity to migrate. Although often assumed to be of high importance in the literature, the effects of flood risk perceptions and experience are mostly weak or insignificant.

Through the comparative nature, the results of this study offer important insights into environmental migration as well as climate adaptation policy in different countries. A main finding is that our results suggest that financial inequalities have a major impact on migration decisions between and within countries. Besides lower migration intentions in general in Argentina and Mozambique, we find that migration decisions in these countries are also shaped much more strongly by household income and migration costs, especially in Mozambique, as compared to France and the United States. While it is known that income plays an important role in migration decisions, this study highlights that migration intentions are generally higher in high-income countries. While in higher-income countries a large swath of the population may be able and willing to bear the often high costs of migration, this may be much harder for relatively poorer households in lower-income countries like Mozambique. Under increased climate risk, where income opportunities are expected to be further confined, this may lead to increased risks of trapped populations17. This result underlines that (financial) support mechanisms (such as managed retreat) may be needed to substantially lower this risk in lower-income countries47,48.

We find in all countries that migration intentions increase substantially under scenarios of higher flood risk, which could be triggered by climate change and associated sea-level rise. This provides an important task for governments and institutions to plan for migration and accommodation49 and protect vulnerable coastal communities. Flood protection measures can have a large influence on migration decisions. For example, coastal protection by governments15, but also in situ flood adaptation by households, can limit the need for migration. Our results provide empirical confirmation of this, showing it can strongly deter migration intentions, and this may be an additional incentive for governments and NGOs in the Global South to facilitate in situ adaptation23,24. Note that protection levels vary greatly across countries, even across regions within the EU or the United States. This shows there are limits to in situ adaptation, especially under climate change and sea-level rise13.

Our study provides data and insights on coastal migration under climate change in different contexts worldwide. Future research can examine sea-level rise impacts other than flooding, such as salinization and erosion50, and may assess the influence of land ownership on migration decisions51. New research may also take a longitudinal survey approach and use in situ adaptation and migration modeling, such as agent-based models11, to elicit under what conditions which migration or adaptation behavior is most likely, by whom, and over time. Together, such studies can further contribute to providing an appropriate scientific knowledge base for decision-makers to anticipate and manage coastal migration and adaptation.

Methods

Survey setup

For our research, comparable household survey data were collected in four countries: Argentina (N = 800), France (N = 849), Mozambique (N = 828), and the United States (N = 1060). All data collection took place in 2022. The regions cover a variety of coastal environments: delta’s, sandy coasts, and urban/rural areas. In each country, data were collected in coastal zones prone to flooding, based on coastal flood risk and climate change models52. We conducted surveys in both urban and rural areas, in all four countries, as dynamics of rural and urban migration may vary considerably12,16. In Argentina, data were collected in the Buenos Aires province; in France, in flood-prone areas along the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts; in Mozambique, in the Sofala province; and in the United States in the states of Florida and New York (see Supplementary Methods for more details). The high (and various) exposure to flood risk of the case studies is reflected by the survey data; in each location, 13% to 73% of respondents have already experienced home flooding in the past 10 years (Supplementary Table 1). Overall, the survey samples are largely representative of the populations from which they were collected (Supplementary Tables 4, 5, 6). We considered weighting of the survey data not feasible because the demographic statistics in flood zones can be uncertain because the delineation of these zones are uncertain due to their course resolution, Therefore, there is a risk of weighting the survey data with incorrect statistics. Moreover, the survey data collection followed the standard procedures to randomly select participants and arrive at a representative sample, as described below.

Per household, only one member was allowed to take part in the survey. The survey data was gathered online in France and the United States. For this, we partnered with survey companies with extensive experience in collecting survey data in the local context and with high-quality and diverse respondent panels, which in France was Kantar and in the United States, Downs & St. Germain Research. Both survey companies implemented pre-survey and in-survey controls to uphold survey data quality and ensure authentic survey responses. Because access to the internet is less widespread in Argentina and Mozambique, especially in rural and lower-income contexts, we collected the survey data through face-to-face interviews in these countries. Here, we worked with experienced (local) survey companies that hired local enumerators and supervisors to conduct the interviews. Target respondent numbers in each of the survey areas were determined in relation to population size and to ensure valid statistical comparisons between case study sites were possible. Within the selected case study areas and neighborhoods, households were randomly approached to ask for their participation in the survey, until the target was reached (with slight deviations being allowed). Only adults in good mental health were allowed to participate in the survey. It was not required for the respondent to be the head of the household, to ensure the equal representation of men and women in the survey. Researchers of the study were present in the countries during the data collection process to assess the study areas, to assist in training the local enumerators, and to help in supervision and guidance. In each of the four countries, we conducted a pilot study to test the clarity and relevance of the survey questions and to make adjustments if necessary (N ~ 60 per country).

The questionnaire was written up in English and translated into local languages by native speakers from the aforementioned local survey companies. The translated questionnaires were then reviewed by local scientific partners to ensure clarity and cultural appropriateness. The data collection and research procedures are all in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the ethics regulations of the European Research Council. All respondents in all countries provided informed consent before participating in the survey.

Migration intentions

We measure permanent migration intentions at present and under three hypothetical flood scenarios using four survey questions (Supplementary Table 1). We define permanent migration as people moving away from their current neighborhood to live somewhere else for the long term, with the intention to stay. This definition allows for the fact that people may move within the same village or elsewhere in the study area. In addition, this definition emphasizes that we measure migration for the long term and not temporary or seasonal migration, while still accounting for the possibility of return migration27. Because migration can be a contentious word, we use acceptable synonyms in each language (e.g., relocation in English). We focus on migration intentions, and not actual migration, because this allows us to research how future changes in flood risk may influence migration patterns. Furthermore, it is hard to localize and identify people who have already migrated from flooding.

To measure current migration intentions, we asked respondents about the likelihood that in the next five years they will permanently migrate away from their neighborhood, with the following answer options: (1) Will not migrate permanently (0% chance to migrate permanently), (2) Unlikely (1%–39% chance), (3) Not unlikely/not likely (40%–60% chance), (4) Likely (61%–99% chance), (5) Will migrate permanently for certain (100% chance to migrate permanently).

The use of probabilities provides richer information on people’s migration intentions than simple yes/no questions, and reflects the uncertainty associated with stated intentions to take future decisions. To improve comprehension for respondents, quantitative probability values are combined with qualitative Likert-scale indicators, which was especially important for data collection in the lower-income contexts. In accordance with previous research25,27, we employ for the analyses the probability (percentage) values because this allows us to estimate linear models, which display easily interpretable marginal effects. For answer options that contain a range of percentage values, we use the middle value (i.e., 20 for the answer option “Unlikely (1%–39% chance)”, 50 for “Not unlikely/not likely (40%–60% chance)”, and 80 for “Likely (61%–99% chance)”).

Subsequently, we measured migration intentions using three survey questions, including scenarios of flood risk, which relate to the frequency with which major flood events occur. The same answer options are used here as for the question on current migration intentions, described previously. To keep results comparable, we presented the same definition of major flooding to respondents in all countries, based on the definition by US National Weather Service53: “A major flood is a flood that results in the extensive (and potentially destructive) inundation of buildings and roads and requires significant evacuations of people and transfer of people’s property to higher elevations”. In the three questions, we asked respondents to imagine that such major flood events would occur in their neighborhood on average (1) once every 10 years, (2) once every 5 years, and (3) once every year, and to thereafter provide the likelihood that they would permanently migrate from their neighborhood under the given scenario. Using changes in flood frequency is a common way to present flood risk scenarios to respondents, and has been applied and tested in multiple questionnaire studies on flood adaptive behavior27,54,55.

Flood risk scenarios

All areas surveyed are at least in the projected 1 in 10-year coastal flood zone in 2100/2150 under current trajectory climate change (SSP 3-7.0), but most face higher expected coastal flood risk51. Besides coastal flooding, the study areas are also at risk of pluvial and/or fluvial flooding and compound floods, for which risk is also expected to increase under climate change56,57,58. In the flood scenarios, we do not specify the flood type, and they thus represent overall flood risk. This is also helpful because flood types often interact. Although not all respondents in the survey face the same (future) flood risk, utilizing the same scenarios across contexts is needed to make results comparable and provide a quantitative bandwidth of how migration could evolve under changing flood risk. In Mozambique, the two highest flood scenarios are already close to lived reality, with several major floods in the past years, whereas the 10-year flood scenario would represent an improvement to current conditions. On the other hand, in France, the 1-year flood scenario is unlikely in most places given current flood protection standards and climate change projections. Whether the scenarios will become reality depends, to a large extent, on climate change mitigation and adaptation policies, making our findings relevant for a broad range of climate and policy scenarios.

To gauge respondent’s comprehension of the scenario questions and to test the accuracy of the reported migration intentions, we asked a debriefing question to all respondents about how certain they were of their choices in these questions. This is a common and validated debriefing question in the choice behavior literature59. Measured on a five-point scale from very uncertain to very certain, respondents on average reported to be certain about their choices (means vary from 3.81 in the United States to 4.23 in Mozambique). Only 3% (Mozambique) to 13% (United States) of respondents reported being very uncertain or uncertain about their choices. That there is some uncertainty is not surprising given that migration can be a difficult decision to make. In most countries, except Mozambique, there is a weak positive correlation of certainty with migration intentions, indicating that people who report lower intentions to migrate are more uncertain about their choice than people with higher migration intentions.

Drivers of migration

To understand what drives migration under different scenarios of flood risk, we assess the role of a comprehensive set of explanatory variables. These variables and the associated survey questions and coding are presented in Supplementary Table 1. The core of our analytical framework is grounded in protection motivation theory (PMT)21, and consists of threat appraisal (perceived likelihood, perceived severity, and worry) and coping appraisal (response efficacy, self-efficacy, and response costs). PMT is the state-of-the-art theoretical framework in behavioral research on in situ climate adaptation, generally exhibiting a high explanatory power22,23,24. The components of the PMT framework also reflect aspects that are assumed to be critical in migration behavior (under climate change), including risk perceptions, capabilities to migrate, and migration costs13,18,31,60. In addition to risk perceptions related to flooding, we add climate change perceptions as an additional variable to the PMT framework to account for the fact that we study migration under climate change-induced flood risk scenarios.

Based on a thorough screening of the literature on flood- and climate change related mobility, including multiple review studies, we have extended the analytical framework with additional variables that have been found to be important factors in migration decision-making (under flood risk/climate change) or that have been proposed as critical topics for future research9,12,13,19,31,60,61. In this way, the analyses allow for the comparability of research findings across studies and contribute to moving the field forward. These additional variables include flood experience, the implementation of in situ flood adaptation, place attachment, life satisfaction, social networks, migration experience, and risk preferences. We also control in all our analyses for age, gender, education, household income, and rurality. Regarding gender, we incorporate the category “other or non-specified” in our analyses to safeguard inclusion, but due to low observations, the results for this category should be taken with caution. All question wordings for these variables are derived from and tested in previous research on these topics. Supplementary Table 2 displays relevant literature for each of these variables and the expected signs of the variable effects.

Regression analysis

To analyze the drivers of migration intentions, we make use of regression analyses. There are four dependent variables, including current migration intentions as well as migration intentions under the three flood risk scenarios (see “Dependent variables” section). Because we are interested in a cross-country comparison of migration drivers, we perform the analyses separately by country. This leads to a total of 16 regressions for the main analyses, all involving the same independent variables as described previously. We employ linear regression models because we measure the likelihood of migration as probabilities. The linear regression models are formulized as Eq. (1):

with M representing migration intentions, of individual i, regressed on k independent variables presented above. A variance inflation factor (VIF) analysis shows that for all countries, there is no indication of worrisome multicollinearity in the regression models (all VIFs <2). In addition to linear models, as a robustness test, we also performed ordered logit models using the Likert-scale categories instead of the percentage values, which led to very similar results (results available upon request).

In the paper, we also conduct a mediation analysis to assess whether flood risk perceptions mediate the impact of flood experience on migration intentions (flood experience may indirectly influence migration by increasing risk perceptions). For this analysis, we utilize the Karlson-Holm-Breen (KHB) method, which decomposes the total effects into direct and indirect effects in an unbiased manner62.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data has been collected under strict ethical rules of the case study countries, and the survey questions have been checked by an internal VU-University ethical commission. The raw COASTMOVE survey data cannot be shared openly due to privacy restrictions. For more detailed information on the survey data and case studies, see Supplementary Information. Source data for the figures are provided at this repository: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15090126. To evaluate the representativeness of the survey data, we compared our survey data with high-resolution age and gender data publicly available at https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/projects/gpw (see Supplementary Information). Countries were classified to income levels using World Bank data: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/opendata/new-world-bank-country-classifications-income-level-2022-2023. We used EUROSTAT data to derive educational levels: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/DEMO_R_PJANGRP3__custom_6246571/default/table?lang=en. We used national census data on educational levels for Argentina, publicly available from https://www.indec.gob.ar/indec/web/Nivel4-Tema-2-41-135, for Mozambique, publicly available from https://www.ine.gov.mz/en/inicio, and for the United States, publicly available from https://data.census.gov/.

Code availability

The model code used to conduct our statistical analyses are available at an open-source repository: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15090126. The code was run in Stata SE 18. We used the KHB package (Karlson-Holm-Breen method) to conduct the mediation analysis.

References

Kirezci, E. et al. Projections of global-scale extreme sea levels and resulting episodic coastal flooding over the 21st Century. Sci. Rep. 10, 11629 (2020).

Moftakhari, H. R., Salvadori, G., AghaKouchak, A., Sanders, B. F. & Matthew, R. A. Compounding effects of sea level rise and fluvial flooding. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 9785–9790 (2017).

Vitousek, S. et al. Doubling of coastal flooding frequency within decades due to sea-level rise. Sci. Rep. 7, 1399 (2017).

IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability (IPCC, 2022).

Neumann, B., Vafeidis, A. T., Zimmermann, J. & Nicholls, R. J. Future coastal population growth and exposure to sea-level rise and coastal flooding—a global assessment. PLoS ONE 10, e0118571 (2015).

Lincke, D. & Hinkel, J. Coastal migration due to 21st century sea‐level rise. Earths Future 9, e2020EF001965 (2021).

Nicholls, R. J. et al. Sea-level rise and its possible impacts given a ‘beyond 4 °C world’ in the twenty-first century. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 369, 161–181 (2011).

Hauer, M. E. Migration induced by sea-level rise could reshape the US population landscape. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 321–325 (2017).

Duijndam, S. J., Botzen, W. J. W., Hagedoorn, L. C. & Aerts, J. C. J. H. Anticipating sea‐level rise and human migration: a review of empirical evidence and avenues for future research. WIREs Clim. Change 13, e747 (2022).

Schlüter, M. et al. A framework for mapping and comparing behavioural theories in models of social-ecological systems. Ecol. Econ. 131, 21–35 (2017).

Tierolf, L. et al. A coupled agent-based model for France for simulating adaptation and migration decisions under future coastal flood risk. Sci. Rep. 13, 4176 (2023).

Black, R. et al. The effect of environmental change on human migration. Glob. Environ. Change 21, S3–S11 (2011).

Hauer, M. E. et al. Sea-level rise and human migration. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 28–39 (2020).

Laurice Jamero, M. et al. Small-island communities in the Philippines prefer local measures to relocation in response to sea-level rise. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 581–586 (2017).

Reimann, L. et al. Exploring spatial feedbacks between adaptation policies and internal migration patterns due to sea-level rise. Nat. Commun. 14, 2630 (2023).

Hunter, L. M., Luna, J. K. & Norton, R. M. Environmental dimensions of migration. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 41, 377–397 (2015).

Cundill, G. et al. Toward a climate mobilities research agenda: intersectionality, immobility, and policy responses. Glob. Environ. Change 69, 102315 (2021).

Kaczan, D. J. & Orgill-Meyer, J. The impact of climate change on migration: a synthesis of recent empirical insights. Clim. Change 158, 281–300 (2020).

Berlemann, M. & Steinhardt, M. F. Climate change, natural disasters, and migration—a survey of the empirical evidence. CESifo Econ. Stud. 63, 353–385 (2017).

Hamadeh, N., Van Rompaey, C., Metreau, E. & Eapen, S. G. New World Bank country classifications by income level: 2022–2023. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/opendata/new-world-bank-country-classifications-income-level-2022-2023 (2023).

Rogers, R. W. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J. Psychol. 91, 93–114 (1975).

Kuhlicke, C. et al. Spinning in circles? A systematic review on the role of theory in social vulnerability, resilience and adaptation research. Glob. Environ. Change 80, 102672 (2023).

Noll, B., Filatova, T., Need, A. & Taberna, A. Contextualizing cross-national patterns in household climate change adaptation. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 30–35 (2022).

van Valkengoed, A. M. & Steg, L. Meta-analyses of factors motivating climate change adaptation behaviour. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 158–163 (2019).

Duijndam, S. J. et al. A look into our future under climate change? Adaptation and migration intentions following extreme flooding in the Netherlands. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 95, 103840 (2023).

Schwaller, N. L., Kelmenson, S., BenDor, T. K. & Spurlock, D. From abstract futures to concrete experiences: how does political ideology interact with threat perception to affect climate adaptation decisions? Environ. Sci. Policy 112, 440–452 (2020).

Duijndam, S. J. et al. Drivers of migration intentions in coastal Vietnam under increased flood risk from sea level rise. Clim. Change 176, 12 (2023).

Hoffmann, R., Dimitrova, A., Muttarak, R., Crespo Cuaresma, J. & Peisker, J. A meta-analysis of country-level studies on environmental change and migration. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 904–912 (2020).

Mixed Migration Centre. Climate and Mobility Case Study: Beira, Mozambique: Praia Nova. (Mixed Migration Centre, 2023).

McLeman, R. In Climate and Human Migration: past Experiences, Future Challenges (ed. McLeman, R.) 180–209 (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Piguet, E. Linking climate change, environmental degradation, and migration: An update after 10 years. WIREs Clim. Change 13, e746 (2022).

Chinn, S., Hart, P. S. & Soroka, S. Politicization and polarization in climate change news content, 1985-2017. Sci. Commun. 42, 112–129 (2020).

Botzen, W. J. W., Michel-Kerjan, E., Kunreuther, H., De Moel, H. & Aerts, J. C. J. H. Political affiliation affects adaptation to climate risks: evidence from New York City. Clim. Change 138, 353–360 (2016).

Di Baldassarre, G. et al. Multiple hazards and risk perceptions over time: the availability heuristic in Italy and Sweden under COVID-19. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 21, 3439–3447 (2021).

Koerth, J., Vafeidis, A. T. & Hinkel, J. Household-level coastal adaptation and its drivers: a systematic case study review. Risk Anal. 37, 629–646 (2017).

Future Earth. Human Migration and Global Change: A Synthesis of Roundtable Discussions Facilitated By Future Earth. https://futureearth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/synthesis_of_migration_roundtable_discussions_final.pdf (2019).

Aerts, J. A review of cost estimates for flood adaptation. Water 10, 1646 (2018).

Massey, D. S. Social structure, household strategies, and the cumulative causation of migration. Popul. Index 56, 3 (1990).

Adams, H. Why populations persist: mobility, place attachment and climate change. Popul. Environ. 37, 429–448 (2016).

Dandy, J., Horwitz, P., Campbell, R., Drake, D. & Leviston, Z. Leaving home: place attachment and decisions to move in the face of environmental change. Reg. Environ. Change 19, 615–620 (2019).

Swapan, M. S. H. & Sadeque, S. Place attachment in natural hazard-prone areas and decision to relocate: research review and agenda for developing countries. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 52, 101937 (2021).

Boley, B. B. et al. Measuring place attachment with the Abbreviated Place Attachment Scale (APAS). J. Environ. Psychol. 74, 101577 (2021).

Steckermeier, L. C. The value of autonomy for the good life. An empirical investigation of autonomy and life satisfaction in Europe. Soc. Indic. Res. 154, 693–723 (2021).

Jaeger, D. A. et al. Direct evidence on risk attitudes and migration. Rev. Econ. Stat. 92, 684–689 (2010).

Gray, C. L. & Mueller, V. Natural disasters and population mobility in Bangladesh. Proc Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 6000–6005 (2012).

Seebauer, S. & Winkler, C. Should I stay or should I go? Factors in household decisions for or against relocation from a flood risk area. Glob. Environ. Change 60, 102018 (2020).

Nawrotzki, R. J. & DeWaard, J. Putting trapped populations into place: climate change and inter-district migration flows in Zambia. Reg. Environ. Change 18, 533–546 (2018).

Siders, A. R., Hino, M. & Mach, K. J. The case for strategic and managed climate retreat. Science 365, 761–763 (2019).

Bott, L. M. & Braun, B. How do households respond to coastal hazards? A framework for accommodating strategies using the example of Semarang Bay, Indonesia. Int. J. Dis. Risk Red. 37, 101177 (2019).

Tierolf, L. et al. Coastal adaptation and migration dynamics under future shoreline changes. Sci. Tot. Environ. 917, 170239 (2024).

Akhter, S. & Bauer, S. Household level determinants of rural-urban migration in Bangladesh. Int. J. Soc. Behav. Educ. Econ. Bus. Ind. Eng. 8, 24–27 (2014).

Kulp, S. A. & Strauss, B. H. New elevation data triple estimates of global vulnerability to sea-level rise and coastal flooding. Nat. Commun. 10, 4844 (2019).

National Weather Service. Floods: The Awesome Power. 1–14 https://www.weather.gov/media/bis/Floods.pdf (2005).

Botzen, W. J. W. & van den Bergh, J. C. Monetary valuation of insurance against flood risk under climate change. Int. Econ. Rev. 53, 1005–1026 (2012).

Brouwer, R., Tinh, B. D., Tuan, T. H., Magnussen, K. & Navrud, S. Modeling demand for catastrophic flood risk insurance in coastal zones in Vietnam using choice experiments. Environ. Dev. Econ. 19, 228–249 (2014).

Fowler, H. J., Wasko, C. & Prein, A. F. Intensification of short-duration rainfall extremes and implications for flood risk: current state of the art and future directions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 379, 20190541 (2021).

Hirabayashi, Y. et al. Global flood risk under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 816–821 (2013).

Wahl, T., Jain, S., Bender, J., Meyers, S. D. & Luther, M. E. Increasing risk of compound flooding from storm surge and rainfall for major US cities. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 1093–1097 (2015).

Haghani, M., Bliemer, M. C. J., Rose, J. M., Oppewal, H. & Lancsar, E. Hypothetical bias in stated choice experiments: Part II. Conceptualisation of external validity, sources and explanations of bias and effectiveness of mitigation methods. J. Choice Model. 41, 100322 (2021).

Stoler, J. et al. The role of water in environmental migration. WIREs Water 9, e1584 (2022).

Bernzen, A., Jenkins, J. C. & Braun, B. Climate change-induced migration in coastal Bangladesh? A critical assessment of migration drivers in rural households under economic and environmental stress. Geosciences 9, 1–21 (2019).

Breen, R., Bernt Karlson, K. & Holm, A. A note on a reformulation of the KHB method. Sociol. Methods Res. 50, 901–912 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research received funding from the European Research Council through the ERC Advanced Grant project COASTMOVE (nr. 884442) and ERC grant project INSUREADAPT nr. 101086783. We thank the local survey partners for the great collaborations in collecting all the survey data. We also thank Lars Tierolf for making the case study map.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.D. took the lead in conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, visualization, and writing.; S.D. and L.C.H. jointly conducted the investigation with support from W.J.B. and J.C.J.H.A.; W.J.B., J.C.J.H.A. and L.C.H. supported conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, writing–original draft, writing–review, and editing.; S.C., J.D.-B., M.T., B.R., J.B. supported investigation and writing–review and editing; J.C.J.H.A. had the lead in funding and acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Duijndam, S.J., Botzen, W.J.W., Hagedoorn, L.C. et al. Global determinants of coastal migration under climate change. Nat Commun 16, 6866 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59199-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59199-y