Abstract

Na-birnessite is a promising low-cost positive electrode material for aqueous sodium-ion batteries. However, its sodium storage capability is limited by narrow potential window and low redox activity in aqueous electrolytes. Herein, a Na-rich birnessite (NaMnO2•0.1H2O) with a highly ordered layered structure is reported as an advanced positive electrode for aqueous sodium-ion batteries, greatly suppressing Mn migration and its accompanying domino degradation effect, which enables a promoted upper charging cut-off potential up to 1.4 V (vs. Ag/AgCl), an enhanced specific capacity of 199.9 mAh g−1 at a specific current of 0.2 A g−1 based on the mass of active material for positive electrode, and greatly improved structural stability. In particular, a 3.0 V NaxH2–xTi2O5||NaMnO2•0.1H2O aqueous full cell prototype is validated, exhibiting a large specific energy of 117.1 Wh kg−1 based on the total mass of active materials in both positive and negative electrodes as well as a long cycle life. This work elucidates how interlayer chemistry and structural defects influence sodium ion storage in layered structures and provides opportunities for developing high-voltage aqueous batteries with large specific energy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to their low cost and non-flammability, rechargeable aqueous batteries are being considered as safer and more economical alternatives to lithium-ion batteries for large-scale energy storage1,2,3,4,5. However, the electrochemical stability window (ESW) of aqueous electrolytes is usually limited to 1.23 V owing to the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER) of water. This limitation leads to low redox activity of electrode materials and low operating voltage of batteries, hence resulting in low specific energy. Till now, great efforts have been devoted to expanding ESW of aqueous electrolytes6, including developing super-concentrated or molecular crowding electrolytes1,7,8, applying pH-modified/decoupling electrolytes9,10,11, introducing redox couple electrolytes12, and optimizing current collectors13. For instance, a super-concentrated LiTFSI aqueous electrolyte (>20 M) has been developed for a full aqueous Mo6S8||LiMn2O4 Li-ion battery, achieving a significantly expanded ESW of 3.0 V with good cycle performance1. Nevertheless, most previous works focused on electrolyte modification, and very few works investigated the electrode materials design to enlarge ESW.

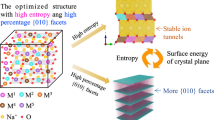

For aqueous sodium-ion batteries, manganese oxides (birnessite14,15,16,17, α-MnO218,19,20, Mn5O821,22, etc.) were widely explored as positive electrode materials because of their low cost and large theoretical capacity. However, the upper charging cut-off potential of manganese-based oxides is usually limited to ~1.0 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) in neutral electrolytes due to the low OER overpotential, thus restricting the ESW of aqueous sodium-ion batteries less than 2 V. Among manganese oxides, birnessite, a layered structure comprised of edge-sharing MnO6 octahedral slabs and intercalated Na+/crystal water, has attracted great interest due to its promising Na storage performance17. However, birnessite contains different symmetries, including hexagonal, monoclinic, and triclinic, and the reported Na+/crystal water contents are very different from sample to sample. Therefore, the reported Na storage performance of birnessite varies widely in literature, and clear guidance on the structural design of birnessite for aqueous sodium-ion batteries is still lacking. Based on the structural feature, we propose a structural design for birnessite to expand its potential window and increase its redox activity in aqueous electrolyte (Fig. 1). In birnessite, Mn defects (including Mn vacancy and interlayered Mn) are considered as highly active sites for OER23,24, which should be minimized to extend ESW. The hexagonal birnessite with less crystalline form usually possesses more Mn defects than monoclinic and triclinic birnessites. At the interlayer, the crystal water should be minimized because it reduces the available Na+ intercalation sites, which determines Na storage capacity. As reported in previous works, a high Na content in birnessite was demonstrated to lift its upper charging cut-off potential, resulting in improved Na storage performance15,17. Therefore, we believe birnessite with a high Na content and highly ordered layered structure could be an ideal positive electrode for aqueous sodium-ion batteries.

In this work, we investigate how the interlayer chemistry and Mn defects of birnessite affect its upper charging cut-off potential, OER, and Na storage performance in a neutral aqueous electrolyte. It is found that the upper charging potential limit of birnessite electrode can be significantly promoted by increasing Na content and reducing Mn defects. A Na-rich birnessite of monoclinic NaMnO2•0.1H2O with substantially suppressed Mn defects is developed, which boosts the upper charging cut-off potential to 1.4 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) in a low-concentrated aqueous electrolyte (1 M Na2SO4). In particular, this birnessite electrode can deliver a high reversible specific capacity up to 199.9 mAh g−1 at a specific current of 0.2 A g−1 together with outstanding cycling stability. Based on the results of electrochemical testing and density functional theory (DFT) calculations, we have demonstrated that having a Na-rich and water-deficient interlayer for birnessite is beneficial for increasing the overpotential for OER and structural stability during cycling. Finally, a high-voltage aqueous full cell composed of NaMnO2•0.1H2O electrode and NaxH2–xTi2O5 electrode is constructed, achieving a wide ESW of ~3.0 V with a high specific energy of 117.1 Wh kg−1 at a specific power of 117.5 W kg−1.

Results

Materials synthesis and characterization

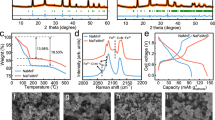

Na-birnessites (NaxMnO2•yH2O) nanowall arrays with tunable Na and crystal water contents were grown on carbon cloth by a “hydrothermal sodiation” method from the porous Mn3O4 nanowall arrays, according to our previous work25. As depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1a, all the diffraction peaks in the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the initial Mn3O4 sample can be assigned to the tetragonal spinel phase (JCPDS Card no. 24-0734). During the hydrothermal treatment, the spinel-to-layered phase transition occurred (Fig. 2a), and Na+ and water co-intercalated into the layered structure to form birnessite. By controlling the hydrothermal temperature and procedure, the N1 (Na0.46MnO2•0.61H2O), N2 (Na0.71MnO2•0.32H2O), and N3 (NaMnO2•0.10H2O) samples with various Na and crystal water contents were obtained. The chemical formulas of the N1–N3 samples were determined by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES, Fig. 2a) measurements and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA, Supplementary Fig. 2). The chemical compositions of the products validate the hypothesis that Na+ ions and crystal water molecules compete to occupy the interlayer sites.

a Schematic illustration of the phase transition from spinel-Mn3O4 to Na0.46MnO2•0.61H2O (N1), Na0.71MnO2•0.32H2O (N2), and NaMnO2•0.10H2O (N3). b XRD patterns of the N1 (in grey), N2 (in blue), and N3 (in red) powder samples collected from carbon cloth. c PDFs for the N1 (in grey), N2 (in blue), and N3 (in red) samples.

To increase the Na content in birnessite, the interlayer crystal water must be reduced to release available sites. XRD patterns of all the N1–N3 powder samples collected from the carbon cloth exhibit a similar monoclinic birnessite structure (JCPDS Card no. 43-1456) with a space group of C2/m (Fig. 2b). The (001) diffraction peak shows a slight shift to higher diffraction angles from N1 to N3, indicating a decrease of interlayer distance for the birnessite, which is consistent with reduction of crystal water from N1 to N3. Synchrotron X-ray atomic pair distribution function (PDF) analysis was performed to investigate the local structure of the samples. As shown in Fig. 2c, the three peaks in PDF with increasing distance are indexed as Mn–O pair from MnO6 octahedral unit, and Mn–Mn pair and Mn–O pair from the nearest MnO6 octahedral units. The PDF analysis reveals a shortening trend of the average Mn–O bond length from N1 to N3, suggesting the MnO6 octahedral slabs could be stabilized by having more Na+ ions and less crystal water, which restrains the migration of Mn ions from the Mn layers to Na layers or the dissolution of Mn ions into the aqueous electrolyte26,27.

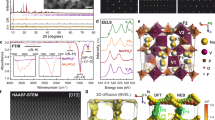

The field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) images show the morphology evolution from Mn3O4 to N1–N3 samples. Supplementary Fig. 3 reveals that the as-prepared Mn3O4 sample has a uniform nanowall morphology and each nanowall is composed of numerous nanoparticles. After the hydrothermal sodiation process, the N1 and N2 samples retain the similar nanowall morphology with very smooth surface (Fig. 3a–d), while the N3 sample shows a hierarchical nanowall morphology composed of interconnected nanosheets (Fig. 3e, f). To further investigate the crystal structures of N1–N3 at atomic scale, advanced spherical aberration-corrected electron microscope was utilized for detailed structural analysis. The high-angle annular dark field (HAADF)-scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) images of the N1–N3 samples recorded along the [010] zone axis are shown in Fig. 3g–i. The atomic arrangements in the N1–N3 samples agree well with the crystal model of the monoclinic birnessite along the [010] zone axis without any distorted Mn arrangements and Mn vacancies. The measured interlayer distances for the (001) planes of N1–N3 are 7.2, 7.1, and 7.0 Å, respectively, which are in good agreement with the XRD results. Further, Supplementary Fig. 4 shows the annular bright field (ABF)-STEM images of the N1–N3 samples recorded along the [010] zone axis. The N3 sample revealed a clearly higher contrast of interlayered Na than those of N1 and N2, suggesting the higher Na content in N3. A representative STEM image of N3 and corresponding energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mappings of Na, Mn, and O elements are shown in Fig. 3j. It can be seen that all the elements are uniformly distributed in the N3 nanosheets, implying the successful and efficient intercalation of Na+ ions during hydrothermal treatment. The Mn valence states in different samples were investigated by soft X-ray absorption spectroscopy (sXAS). The Mn L-edge sXAS spectrum consists of well separated absorption features in two regions of L3 (638–646 eV) and L2 (649–656 eV), resulting from the 2p core-hole spin-orbital splitting28. In the Mn L-edge sXAS spectrum of the Mn3O4 sample (Supplementary Fig. 1b), the two peaks in the L3 region correspond well to the Mn2+ and Mn3+ components in the spinel. Figure 3k shows Mn L-edge sXAS spectra of N1–N3, where the two peaks in the L3 region correspond to Mn3+ and Mn4+ components. It can be clearly seen that the Mn3+/Mn4+ ratio increases from N1 to N3 samples in the sXAS spectra, which agrees well with increasing Na content from N1 to N328.

FESEM images of (a, b) N1, (c, d) N2, and (e, f) N3 samples, respectively. g–i HAADF-STEM images of the N1–N3 samples along the [010] zone axis, respectively. j STEM image of the N3 sample and corresponding EDS mapping of Na, Mn, and O elements. k Mn L-edge sXAS spectra of the N1 (in grey), N2 (in blue), and N3 (in red) samples.

Electrochemical performance

The sodium storage performances of the N1–N3 samples in aqueous electrolyte (1 M Na2SO4) were investigated in three-electrode cells using Pt counter electrode and Ag/AgCl reference electrode. Figure 4a shows the typical cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of the N1–N3 electrodes at a scan rate of 1 mV s−1 in the potential window of 0 ~ 1.4 V (vs. Ag/AgCl). It is interesting to note that the CV curves display distinct behaviors within the same potential window for the three electrodes. For the N1 and N2 electrodes, the CV curves show a sharp specific current leap towards the upper cut-off potential, suggesting intense water decomposition ascribed to OER. From N1 to N3, the current leap is continuously decreasing, and it is barely seen in the CV curve for the N3 electrode, indicating suppressed OER with high Na content in birnessite. To further investigate the influence of carbon cloth on the N1–N3 electrodes, the polarization curve of carbon cloth was directly measured. The carbon cloth electrode shows higher OER activity than N2 (Supplementary Fig. 5a), illustrating that the carbon cloth cannot help improve upper cut-off potentials in N2 and N3. In the meantime, reversible redox peaks become more prominent with increasing specific current from N1 to N3, suggesting enhanced Na+ intercalation/deintercalation behavior with increased Na+ storage capability. At high scan rates (Supplementary Fig. 6), the CV curves of the N3 electrode show slight distortion with small polarization and the highest specific current as compared to N1 and N2, indicating good reversibility and rate capability.

a CV curves of the N1 (in grey), N2 (in blue), and N3 (in red) electrodes at a scan rate of 1 mV s−1 in 50 mL 1 M Na2SO4 using a platinum foil counter electrode and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode at 25 °C. b The charge/discharge curves of the N1 (in grey), N2 (in blue), and N3 (in red) electrodes at a specific current of 0.2 A g−1. c Rate capabilities of the N1 (in grey), N2 (in blue), and N3 (in red) electrodes and corresponding Coulombic efficiencies. d CV curve of the N3 electrode between 0 and 1.4 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) with shadowed area representing the surface capacitive contribution at a scan rate of 1 mV s−1. e Histograms illustrating the capacitive- and diffusion-controlled capacities at different scan rates for the N1 (in grey), N2 (in blue), and N3 (in red) electrodes. f Long-term cycle performance of the N1 (in grey), N2 (in blue), and N3 (in red) electrodes at a specific current of 10 A g−1. g CV curves of the NaxH2–xTi2O5||NaMnO2•0.1H2O full cell at different scan rates. h Charge/discharge curves of the NaxH2–xTi2O5||NaMnO2•0.1H2O full cell at different specific currents. i Cycle performance of the NaxH2–xTi2O5||NaMnO2•0.1H2O full cell at a specific current of 10 A g−1. All electrochemical measurements of three-electrodes were carried out in 50 mL 1 M Na2SO4 using a platinum foil counter electrode and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode at 25 °C, and the potential is not iR-corrected in the three-electrodes; all electrochemical measurements of the two-electrode cells were carried out in 80 μL 1 M Na2SO4 with the mass ratio of active materials in positive and negative electrodes of 1:3 at 25 °C.

The initial charge/discharge curves for each electrode at a specific current of 0.2 A g−1 are presented in Fig. 4b. For the three electrodes, all charge curves show larger capacity than discharge curves, and the irreversible capacity loss between charge and discharge can be attributed to water decomposition. It is clear that the N3 electrode shows the highest initial coulombic efficiency of 94.4% (78.2% for N1 and 85.4% for N2), which agrees well with the CV behavior, implying significantly suppressed OER in the N3 electrode. At a specific current of 0.2 A g−1, the reversible specific capacity of the N3 electrode can reach 199.9 mAh g−1, which is larger than 144.0 mAh g−1 for N1 and 177.9 mAh g−1 for N2 (based on the mass loadings of active materials for positive electrodes). Notedly, the carbon cloth electrode reveals negligible discharge capacities of <4 mAh g−1 (based on the mass loadings of active material or carbon cloth; Supplementary Fig. 5b, c) as compared to those of N1–N3 (>140 mAh g−1). The charge/discharge curves of the N1–N3 electrodes between 0 ~ 1.4 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) at different specific currents from 0.2 A g−1 to 10 A g–1 are shown in Supplementary Fig. 7. As the specific current increases, the charge and discharge curves of the N3 electrode display smaller polarization increase as compared to N1 and N2, revealing enhanced electrode kinetics in N3. As shown in the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) spectra (Supplementary Fig. 8), the N3 electrode exhibits the smallest ohmic resistance and charge transfer resistance as compared to N1 and N2. In addition, the straight line with the largest slope in the low frequency region for N3 suggest that the N3 electrode possesses enhanced Na+ diffusion capability in comparison with N1 and N2. The specific discharge capacities of the N1–N3 electrodes as a function of specific current were calculated and compared in Fig. 4c. Obviously, the N3 electrode exhibits both larger specific capacities and higher coulombic efficiencies at different specific currents than N1 and N2, demonstrating its superior rate performance with high reversibility. Even at a high specific current of 10 A g−1, the N3 electrode can still deliver a high specific capacity of 118.8 mAh g−1. As reported in literature, extension of the upper cut-off potential above 1.3 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) usually results in a low coulombic efficiency due to the OER of water in aqueous electrolytes, so do the N1 and N2 electrodes in this work. However, for the N3 electrode, a high initial coulombic efficiency of 94.4% can be achieved even at a low specific current of 0.2 A g−1 (near 100% during cycling), endowing the N3 electrode with a wide ESW in the neutral aqueous electrolyte.

To gain insight into the charge storage mechanism of the N1–N3 electrodes, the current contributions of surface-controlled process and diffusion-controlled process are separated by using Dunn’s method29. The surface-controlled capacitance contribution of each sample is shown by the shaded region in the CV curves in Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 9. Figure 4e summarizes the capacity contributions from diffusion-controlled and capacitive processes of the N1–N3 electrodes at different scan rates. At a low scan rate of 1 mV s−1, the capacity contributions for all three electrodes are dominated by bulk Na+ diffusion-controlled process. As the scan rate increases from 1 to 50 mV s−1, the dominant capacity contribution gradually shifts from diffusion-controlled process to surface capacitive process. In comparison, the N3 electrode displays the highest diffusion-controlled capacity contribution under high scan rates, suggesting superior electrode kinetics to N1 and N2. Therefore, it is revealed that the promoted Na storage capacity for the N3 electrode is mainly contributed by the facilitated Na+ intercalation/de-intercalation rather than the surface-dominated capacitive reaction despite the highest specific surface area of N3 (Supplementary Fig. 10). The long-term cycling stability was evaluated by galvanostatic charge/discharge measurements at a specific current of 10 A g−1 (Fig. 4f). After 20000 cycles, the retained discharge specific capacities are 17.8, 41.4, and 100.7 mAh g−1 for the N1, N2, and N3 electrodes, corresponding to 34.8%, 51.3%, and 82.9% capacitance retentions, respectively. Additional cycling tests of two duplicate N1–N3 electrodes also demonstrate consistent cycle performances across the N1–N3 electrodes (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 11). Compared with the previous reports for the birnessite and other MnOx-based electrodes in aqueous electrolytes, the as-presented N3 electrode exhibits both large specific capacity and long cycle life (Supplementary Table 1), suggesting the interlayer chemistry modulation in birnessite is effective in enhancing its Na storage capability and structural stability.

To demonstrate the future application of this N3 electrode in aqueous batteries for Na storage, a suitable negative electrode with an appropriate potential window and compatible capacity should be developed to couple with the N3 electrode for constructing the high-voltage aqueous Na-ion storage device. Ti-based materials have been reported as negative electrode materials with wide negative potential window, such as hydrogenated TiO2-II phase nanowire arrays and TiO2 nanowire arrays30,31. In this study, the NaxH2–xTi2O5 nanoflakes were grown on Ti foil to serve as the negative electrode, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 12a, b. The HRTEM image reveals a layered structure with an average interlayer distance of 7.6 Å (Supplementary Fig. 12c). The representative STEM image and corresponding EDS elemental mappings of Na, Ti, and O elements for the sample are shown in Supplementary Fig. 12d, indicating that all the elements are uniformly distributed throughout the entire nanosheets. In Supplementary Fig. 12e, f, the negative electrode material is identified as the orthorhombic phase of NaxH2–xTi2O5, confirmed by both XRD (JCPDS Card no. 47-0124) and Raman spectroscopy results32,33,34.

To clarify the suppressed hydrogen generation of the full cell on charging, we investigated the HER behavior of the Ti foil-supported NaxH2–xTi2O5 electrode. Supplementary Fig. 13 displays the polarization curve of the NaxH2–xTi2O5 electrode with a scan rate of 10 mV s−1, which confirms its low HER activity. Furthermore, the Ti foil-supported NaxH2–xTi2O5 electrode operates stably within a negative potential window of −1.6 ~ 0 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) in a 1 M Na2SO4 electrolyte (Supplementary Fig. 14) without observable hydrogen generation. The low HER activity and wide negative potential window of the NaxH2-xTi2O5 electrode accounts for the significant suppression of hydrogen generation on charge for the full cell device. Figure 4g shows the typical CV curves of the NaxH2–xTi2O5||NaMnO2•0.1H2O full cell at different scan rates of 1–50 mV s−1. Accordingly, the charge/discharge curves of the full cell between 0 and 3 V at different specific currents are shown in Fig. 4h. It is encouraging to find that this aqueous full cell device can achieve a wide ESW of 0 ~ 3.0 V with an average discharge voltage of 2.35 V at a specific current of 0.2 A g−1. The initial discharge capacity of the full cell was calculated to be 49.8 mAh g−1 (based on the total weight of active materials in both positive and negative electrodes) with a high initial coulombic efficiency of about 86.4% at a specific current of 0.2 A g−1. The initial irreversible capacity loss of the full cell can mainly be attributed to slight water decomposition on the negative electrode. At a high rate of 10 A g−1, the full cell still delivers a high reversible capacity of about 26.8 mAh g−1, displaying good rate performance. After 8000 consecutive charge/discharge cycles at 10 A g−1 (Fig. 4i), about 80.7% of its initial capacity was retained, indicating good cycle performance for the full cell. Based on the specific capacity and high cell voltage, the present NaxH2–xTi2O5||NaMnO2•0.1H2O full cell can deliver a maximum specific energy of about 117.1 Wh kg−1 at a specific power of 117.5 W kg−1 (Supplementary Fig. 15), which is much larger than the records of previously reported aqueous sodium-ion batteries and supercapacitors, such as AC||δ-MnO2 in 5 M NaNO3 (38.4 Wh kg−1 at the specific power of 599.7 W kg−1)35, Na0.27MnO2||Na0.27MnO2 in 1 M Na2SO4 (25 Wh kg−1 at a specific power of 600 W kg−1)17, NaTi2(PO4)3||Na0.44MnO2 in 1 M Na2SO4 (30 Wh kg−1 at a specific power of 78 W kg−1)36, NaTi2(PO4)3||NaMnO2 in 1 M Na2SO4 (30 Wh kg−1 at a specific power of 50 W kg−1)37, and Ag QD MoO3||Ag QDs MnO2 in 1 M Na2SO4 (51.9 Wh kg−1 at a specific power of 22.6 W kg−1)20.

OER and structural stability

In order to elucidate the mechanism of the raised upper cut-off potential observed in the N3 electrode, we investigated the OER behavior of the N1–N3 electrodes. Supplementary Fig. 16a displays polarization curves of the N1–N3 electrodes with a scan rate of 10 mV s−1. The order of increasing overpotential (η) at a current density of 10 mA cm−2 for the OER is as follows (Supplementary Fig. 16b): N1 (η = 460 mV) < N2 (η = 667 mV) < N3 (η = 788 mV). In general, η increases with the increase of Na content and decrease of crystal water content, indicating the suppressed OER from N1 to N3. In addition to the η value, Tafel slope based on each curve was also calculated as another important metric for the OER activity of the electrodes. The higher slope suggests the lower electrocatalytic activity of the electrode gained from per amount of applied overpotential38.

As shown in Supplementary Fig. 16c, a Tafel slope of 220 mV dec−1 associated with the N3 electrode is significantly higher than the Tafel slopes associated with N1 (90 mV dec−1) and N2 (156 mV dec−1). As reported in the literature on elucidating the rate-determining steps, higher Tafel slopes (>120 mV dec−1) are typically associated with water adsorption process on the catalytic site, while the lower Tafel slopes (≈ 40 mV dec−1) are mainly ascribed to the O–O bond formation39,40,41,42. Therefore, it is suggested that the rate-determining step of OER on these three electrodes is possibly determined by the water adsorption process. In addition to the Na/crystal water content, Mn defects can also significantly affect OER for birnessite electrode. For comparison, monoclinic birnessite (M1) and hexagonal birnessite (H1) were prepared by the traditional chemical synthesis methods43,44. The comparison of PDFs of M1, H1, and N1 suggests the existence of Mn vacancies and interlayered Mn in both M1 and H1 birnessites (Supplementary Fig. 17). Consequently, the M1 and H1 electrodes show greatly enhanced OER as compared to N1, resulting in reduced upper cut-off potentials less than 1.2 V (vs. Ag/AgCl). Owing to the poor structure ordering with Mn defects, the M1 and H1 electrodes also exhibited inferior cycling performance within 10000 cycles.

Structural degradation of the birnessite electrodes after cycling was investigated by STEM and the obtained HAADF images of the N1–N3 samples after 20000 cycles are shown in Fig. 5a–c. It is observed that the N3 electrode maintained the initial highly ordered layered structure with a large and constant interlayer distance of 7.0 Å even after 20000 charge/discharge cycles (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 18c). In contrast, some Mn ions in the N2 electrode have migrated into the Na layers after 20000 charge/discharge cycles (marked by the red circles) in Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 18b. More severe Mn ions migration to the interlayer occurred in the N1 electrode after cycling, resulting in seriously contracted interlayer space (less than 6.0 Å) due to the weakened electrostatic repulsion of oxygen layers between MnO6 slabs (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 18a).

a–c HAADF-STEM images for the N1–N3 samples after 20000 cycles. d Mn L-edge sXAS, e PDFs, and f O K-edge sXAS spectra for the N1 (in grey), N2 (in blue), and N3 (in red) electrodes after 20000 cycles. g XRD patterns for the powdery N1 (in grey), N2 (in blue), and N3 (in red) samples collected from carbon cloth after 20000 cycles.

The Mn L-edge sXAS spectra of the three electrodes after 20000 cycles are shown in Fig. 5d. The sXAS spectra of the electrodes indicate that Mn2+ ions were produced in the N1 and N2 electrodes but not in the N3 electrode after cycling. These results suggest that some tetrahedral Mn2+ species could be formed at the interlayers of the N1 and N2 electrodes. Therefore, it has been revealed that the N3 electrode is structurally more stable as compared to the N1 and N2 electrodes. When Mn ions migrate to interlayers, a pair of Mn–Mninterlayer can be found in PDFs, which has a similar bond length of ~3.5 Å to the Mn–O pair from the nearest MnO6 units. As shown in Fig. 5e, the PDFs of the N1 and N2 electrodes after 20000 cycles show significantly enhanced peaks at ~3.5 Å as compared to N3, which is ascribed to the migration of Mn and formation of interlayered Mn in N1 and N2. Moreover, the PDF datum of the N1 sample displays an asymmetric peak for the Mn–O pair and stronger Mn–Mninterlayer peak than the N2 sample, suggesting more Mn ions migration to the interlayer in N1. The O K-edge sXAS spectra were analyzed for the three samples after cycling to investigate the valence state of interlayered Mn ions and the ligand environment. As shown in Fig. 5f, a peak located at ~533 eV was emerged in the spectra for both N1 and N2, indicating that Mn2+ ions were formed and occupied the tetrahedral positions in the interlayers45,46. In addition, the intensities of the pre-edge peaks at ~529 eV for the N1 and N2 samples after cycling are much stronger than their pristine samples, demonstrating that oxygen losses were generated in the N1 and N2 electrodes during cycling. Therefore, it is believed that the Mn2+ formation in N1 and N2 is driven by the oxygen loss with charge compensation. The oxygen loss and interlayered Mn occupancy induce disorder in the birnessite structure, which can be clear seen in the XRD patterns of the N1–N3 samples after cycling as shown in Fig. 5g. Moreover, the interlayered Mn occupancy could seriously impede Na+ intercalation, thus leading to continuous capacity loss during cycling. With a high Na content, the N3 electrode exhibited greatly enhanced structural stability and didn’t show any detectable oxygen loss and interlayered Mn occupancy during cycling. As shown in XRD pattern (Fig. 5g), the N3 electrode well maintained its highly ordered layered structure even after 20000 cycles, agreeing well with the STEM results.

Discussion

Structural evolution of the N3 electrode during Na+ insertion and extraction was investigated by ex situ XRD and the corresponding contour plot is shown in Fig. 6a. During the charge and discharge processes, all the diffraction peaks shift reversibly without any peak splitting or extra peaks emerging, indicating a solid-state solution reaction without phase transition. The birnessite’s c-lattice parameter and unit-cell volume of the N3 sample during charge and discharge were obtained from the XRD refinement results. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 19, the c-lattice parameter varies between 7.17 and 6.96 Å during charge and discharge, resulting in a small volume change of ~1.8% for the N3 electrode. In comparison to the N3 electrode, the N1 and N2 electrodes exhibited larger changes in c-lattice parameter and overall volume during charge and discharge (Supplementary Figs. 20 and 21). These results suggest that N3 has better structural stability, as it experiences smaller volume change. DFT calculations have been further carried out to investigate the influence of Na content on OER and structural stability of birnessite. The different catalytic activities of the N1–N3 electrodes towards OER were analyzed through a comparative DFT calculation on the (001) surfaces of three structural models representing the N1–N3 samples (Supplementary Fig. 22 and Supplementary Data 1). The Gibbs free energy diagrams along the OER pathways calculated relative to H2O for the three structural models at the potential of 1.23 V (vs. Reversible hydrogen electrode, equilibrium potential of water splitting) are shown in Fig. 6b. Based on the previous reports41,42, four elementary steps were assumed in OER, which proceed through the formation of HO*, O*, HOO*, and OO* (* denotes the active site). All intermediates bind at the single O sites on the MnO6 slabs, and the OER depends on four elementary steps, especially the first three steps, indicating that water dissociation is intrinsically unfavorable on the surface of NaxMnO2•yH2O with high Na content and low crystal water content. Therefore, the DFT calculations directly support the experimental observation of the highest overpotential towards OER for the N3 electrode as compared to N1 and N2. As discussed in the literature38, the OER activities depend highly on the interlayer distances in birnessites. When the crystal water content of birnessite increases, the increased interlayer distance can enhance the OER activity in the present work, agreeing well with the decreased overpotential (Supplementary Fig. 16b) and DFT calculation results (Fig. 6b). Furthermore, the Mn ion migration from the octahedral site in MnO6 layer to the tetrahedral site in Na layer was investigated by the climbing-image nudged elastic band (CI-NEB) method47, which could find saddle points and minimum energy paths. Based on the TGA and ICP results (Supplementary Fig. 23 and Table 2), the chemical compositions of the N1–N3 samples at the fully charged state have been determined, displaying nearly no Na existence for both N1 and N2 but a certain amount of Na (Na/Mn ratio = 0.16) still exists in N3. In a simplified model in Fig. 6c (Supplementary Data 1), we consider a scenario when there is Na but no crystal water at interlayer, which is similar to the fully charged state for the N3 sample. When a Mn ion is taken from the octahedral site to the tetrahedral site, the system can never reach a stable or metastable state and the Mn ion will be pushed back to the original octahedral site at the final state after optimization. In this circumstance, the Mn migration to the interlayer is highly difficult to occur in the N3 electrode during the charge process, which is congruent with the STEM results. In another situation when there is only crystal water but no Na at interlayer (similar to the fully charged states of the N1 and N2 samples), Mn can be stabilized at the tetrahedral site by coordinating with one oxygen from the crystal water molecule. It is found that the Mn migration barrier increases as the crystal water content decreases (Supplementary Fig. 24), which agrees well with the experimental finding that a high Na content with reduced crystal water in birnessite can effectively suppress Mn migration during cycling.

a Contour plot of the ex situ XRD patterns collected during the initial charge/discharge of the N3 electrode under a specific current of 0.2 A g−1 in the potential window of 0 ~ 1.4 V (vs. Ag/AgCl). b The free energy evolutions for water splitting steps on the surfaces of the N1 (in grey), N2 (in blue), and N3 (in red) structural models. c The Mn ion migration barriers with or without Na+ ions existing at the interlayer in birnessite. d, e Schematic illustration of different structure variations of birnessites with different Na and crystal water contents during the charge/discharge processes.

Based on the above analysis, the interlayer chemistry of birnessite plays a critical role in determining its Na storage performance in aqueous electrolyte. The co-intercalation/co-deintercalation of hydrated sodium ions is a possible charge storage mechanism for birnessites in aqueous sodium-ion batteries. The co-intercalation/co-deintercalation of Na+ and H2O is possible when abundant Mn vacancies exist in the birnessite structure. Compared to the highly ordered birnessite structure with single Na+ intercalation/deintercalation, birnessite with abundant Mn vacancies typically shows a reduced ability to lock in the interlayer crystal water, which facilitates the insertion and extraction of hydrated sodium ions. However, this co-intercalation behavior is not completely reversible, leading to irreversible structural changes with variations in crystal water content and rapid structural degradation of birnessite48. For the present study, all the N1–N3 samples exhibited highly ordered layered structures without Mn defects before cycling. The N1 and N2 samples exhibited good cycle performance during the first 10000 cycles, indicating primary single Na+ intercalation and deintercalation. This finding aligns with the minimal changes of crystal water contents in N1 and N2 after 10000 cycles (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 25). During the first 10000 cycles, only a few Mn vacancies are produced in N1 and N2 samples, which accounts for their relatively stable structure and minimal variation in crystal water content.

Structural variations of a low Na content birnessite and a high Na content birnessite during charge and discharge are schematically illustrated in Fig. 6d, e. For the low-Na-content birnessite, during the charge process, nearly all Na+ could be extracted from the interlayer, rendering high possibility for Mn migration from the octahedral site in MnO6 layer to the tetrahedral site in Na layer. The initial formation of Mn vacancies in the N1 and N2 samples is believed to occur gradually with cycling. As shown in the ICP results (Supplementary Table 3), the N1 and N2 samples showed a decrease in Na contents after 10000 cycles, which can greatly increase Mn migration probability and create Mn vacancies in the following cycles. Accordingly, the reduced Na contents in the N1 and N2 samples will render the formation of Mn vacancies for the second 10000 cycles. The accumulation of Mn vacancies in N1 and N2 will trigger oxygen redox and oxygen loss from the lattice49,50, which in turn will induce the formation of Mn2+, allowing it to migrate more favorably to the tetrahedral sites51. Therefore, the loss of oxygen, along with the formation and migration of Mn2+, creates a domino effect that accelerates more and more interlayered Mn occupancies with interlayer distance shrinking and severe irreversible structural degradation with Mn dissolution (Supplementary Table 4), leading to rapid capacity fading for the second 10000 cycles. It is noted that the presence of numerous water molecules can weaken the interaction between Mn and O in N1 and N2. As a result, the average Mn–O bond length becomes longer compared to birnessite with high Na content (N3), as evidenced by the PDF results (Fig. 2c). The increased average Mn–O bond length for the low-Na-content birnessite in the present work indicates weakened MnO6 octahedra, which can increase Mn migration and dissolution capability in the presence of the low Na content with high crystal water content52. It can be seen that Mn dissolution occurs obviously in N1 and N2 after cycling, and Mn dissolution in N1 is more serious than N2 (Supplementary Table 4). Additionally, significant changes in crystal water content in the N1 (from 10.11 wt% to 0.62 wt%) and N2 (from 5.28 wt% to 1.28 wt%) during the second 10000 cycles (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 26) indicate that the intercalation and deintercalation of hydrated sodium ions also contribute to irreversible structural degradation. In contrast, the N3 sample with high Na content retains a certain amount of Na+ at the interlayer at the end of charge and the initial high Na content effectively suppresses the formation of Mn vacancies, which prevents the unfavorable domino effect from occurring throughout the cycling process. With unseen Mn migration (Fig. 5), negligible Mn dissolution (Supplementary Table 4), and largely unchanged crystal water content (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 26), single Na+ intercalation and deintercalation are maintained in N3 sample, ensuring high structure stability for the entire cycling. Therefore, a high Na content with highly ordered layered structure design in N3 enables not only a wide ESW but also enhanced Na storage capacity with long cycle life, which, however, cannot be realized for the traditional birnessites with low Na contents and rich Mn defects.

In summary, highly ordered monoclinic Na-birnessites with different Na and crystal water contents are prepared by a hydrothermal method to investigate their electrochemical properties as positive electrodes for aqueous sodium-ion batteries. A suppressed OER can be achieved for birnessite by reducing Mn defects and increasing Na content, thus enabling an increased upper cut-off potential up to 1.4 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) in a neutral aqueous electrolyte of 1 M Na2SO4. Despite an expanded ESW, the high Na content can also endow the birnessite with a large Na storage capacity and improved structural stability with cycling. In this work, a rationally designed birnessite of NaMnO2•0.1H2O demonstrates a high specific reversible capability of 199.9 mAh g−1 and outstanding cycling stability with 82.9% capacitance retention after 20000 cycles. Based on this advanced positive electrode, a 3.0 V NaxH2–xTi2O5||NaMnO2•0.1H2O aqueous full cell prototype is validated to deliver a high specific energy of 117.1 Wh kg−1. The intrinsic structural degradation mechanism of birnessite in aqueous electrolyte is proposed, suggesting Mn migration from octahedral to tetrahedral site during the charge process is the trigger to induce oxygen loss and further interlayered Mn occupancy (domino effect). Overall, the Na content and Mn defects co-modulation strategy developed here for birnessite may initiate inspirations to design superior layered structures as intercalated positive electrodes for rechargeable batteries.

Methods

Material synthesis

The 3D self-supported porous Mn3O4 nanowall arrays on the carbon cloth, N1, N2, and N3 samples were fabricated according to our previous work25. In detail, the cathodic deposition of Mn3O4 nanowall arrays on the carbon cloth was conducted in a three-electrode configuration, consisting of a piece of carbon cloth (about 2 cm × 2 cm) as the working electrode, a platinum foil (about 4 cm2) as the counter electrode and an Ag/AgCl electrode (in saturated KCl) as the reference electrode. A solution of 0.015 M manganese acetate tetrahydrate (≥99%, Aldrich) and 0.015 M sodium sulfate (≥99%, Aldrich) was used as the electrolyte. A constant potential of −1.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl was applied to the carbon cloth substrate for 900 s during the cathodic deposition. After deposition, as-obtained Mn(OH)2 nanowall arrays on the carbon cloth were cleaned with distilled water and dried in the air at room temperature overnight to convert into Mn3O4. To fabricate the N1 and N2 samples, the Mn3O4 nanowall arrays were immersed into a 50 mL 0.1 M NaOH (≥99%, Aldrich) solution, which was then transferred into a 50 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave and heated at two different temperatures (160 and 180 °C) for 10 h, respectively. Differently, the N3 sample was fabricated by a two-step reaction. The carbon cloth substrate supported Mn3O4 nanowall arrays were hydrothermally treated in a 50 mL 0.15 M NaOH solution at 80 °C for 8 h. Subsequently, they were transferred into a 50 mL 0.1 M NaOH solution and heated at 180 °C for 8 h. After cooling down to room temperature, the obtained birnessite nanowall arrays were rinsed with distilled water and dried at 80 °C in the air for further characterization.

NaxH2–xTi2O5 electrode was prepared by a facile hydrothermal method. Typically, a piece of Ti foil (2 cm × 4 cm) was successively cleaned by sonication in HNO3 (69 wt%, Aldrich), deionized water, and ethanol (≥99.5%, Aldrich) for 30 min, respectively. Subsequently, it was immersed into a 50 mL Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave with 40 mL 1 M NaOH solution. After being heated at 200 °C for 20 h and treated in Ar gas at 300 °C for 2 h, the NaxH2–xTi2O5 sample was obtained.

The M1 and H1 samples were prepared by the traditional chemical synthesis methods43,44. In detail, 1 g NaMnO4 solution (40 wt%, Aldrich) and 1.8 g (NH4)2C2O4·H2O (≥99%, Aldrich) were added to 40 mL deionized water. The above mixed solution was transferred into a 50 mL Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave and subsequently heated at 80 °C for 12 h. The as-prepared product was washed and filtered with deionized water, and dried at 100 °C for 10 h, to obtain the M1 sample. 1 g NaMnO4 solution (40 wt%, Aldrich) and 2 mL acetic acid (≥99.8%, Aldrich) were added to 40 mL deionized water, and subsequently transferred into a 50 mL Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave at 80 °C for 12 h. The as-prepared product was washed and filtered with deionized water, and dried at 100 °C for 10 h, to obtain the H1 sample.

Materials characterization

The crystallographic information and phase purity of the samples were characterized by XRD (Bruker-AXS D8 Advance). The accurate chemical compositions of the samples were determined by TGA (SDTA851E) and ICP (Optima 4300DV) measurements. The ICP test provided each sample’s total mass and Na/Mn ratios. By combining the ICP results with the TGA data, the final chemical formulas of the samples were obtained. The morphology and microstructure of the samples were investigated by FESEM (JSM-IT500HR). A JEM-ARM200F STEM fitted with a double aberration-corrector for both probe-forming and imaging lenses was used to perform HAADF imaging, which was operated at 200 kV. Mn L-edge sXAS and O K-edge sXAS measurements were performed by the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility.

Electrochemical measurements

For the M1 and H1 electrodes, the active material, conductive carbon black (Super P), and poly(vinylidenefluoride) with a mass ratio of 8:1:1 were mixed by N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (≥99%, Aldrich) and stirred by automatic mixer to form a homogeneous slurry, and then the slurry was coated onto carbon cloth with doctor blade as a current collector (without calendaring procedure). The M1 and H1 electrodes were dried at 80 °C in the air for 10 h. The N1–N3 samples grown on carbon cloth, and the NaxH2–xTi2O5 sample grown on Ti foil without any binders or conductive additives were directly used as the electrodes. All above electrodes were transferred into an Ar-filled glove box for future use. The electrochemical measurements of individual working electrodes (the N1–N3, M1, and H1 electrodes as positive electrodes, and the NaxH2–xTi2O5 electrode as a negative electrode; the positive and negative electrodes were both cut to about 2 cm × 2 cm with scissors) were performed using three-electrode cells with a platinum foil (about 2 cm × 2 cm) counter electrode and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode in 50 mL 1 M Na2SO4 (≥99%, Aldrich; 18.2 MΩ cm resistivity for deionized water) electrolyte (pH = 7.54). The CV and galvanostatic charge/discharge measurements of individual positive electrodes were carried out in a potential windows of 0 ~ 1.4 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) (CHI660D). The EIS measurement was performed in the frequency range from 100 kHz to 0.01 Hz with an applied AC perturbation of 10 mV. The gravimetric specific capacity of each sample was calculated from the discharge curves use the following Eq. 1:

where the c (mAh g−1) is the specific capacity, the I (mA) is the applied discharging current, the t (h) is the discharge time, and the m (g) is the weight of active materials on the electrodes.

The electrocatalysis was measured by linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) with a scan rate of 10 mV s−1 using the above three-electrode cells (CHI660D). The measured potentials (vs. Ag/AgCl) were converted to the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) scale via the Nernst Eq. 2:

where the ERHE is the converted potential (vs. RHE), the EAg/AgCl is the experimental potential measured against an Ag/AgCl reference electrode, and the E0Ag/AgCl = 0.1967 V in saturated KCl at 25 °C. The calibration of reference electrode was performed by freshly prepared 4 M KCl solutions before the three-electrode cells testing.

The mass loadings of the active materials for positive and negative electrodes were determined to be 4–5 and 5–6 mg cm−2 by a Sartorius Analytical balance (CPA225D, with a resolution of 10 μg), respectively. To ensure the reproducibility of cycling data in the N1–N3 electrodes, we conducted additional cycling tests using two duplicate N1–N3 electrodes to evaluate their cycle performances. Supplementary Fig. 11 shows the long-term cycle performances of two duplicate N1–N3 electrodes with the mass loadings of 4 and 5 mg cm−2 at a specific current of 10 A g−1. For the ex situ measurements, all the electrode samples were cleaned with deionized water, dried at 80 °C in the air for 10 h, and protected in the vacuum packaging during storage transportation and handling.

The 2032-coin type full cell device was assembled by using N3 sample with 0.8 cm × 0.8 cm as a positive electrode and NaxH2–xTi2O5 with 1.3 cm × 1.3 cm as a negative electrode, separated by a piece of glass fiber (Whatman) with a diameter of 19 mm in 80 μL 1 M Na2SO4 (≥99%, Aldrich; 18.2 MΩ cm resistivity for deionized water) electrolyte. The mass ratio of NaxH2–xTi2O5||NaMnO2•0.1H2O was set to be 3:1 for the full cell to attain matched capacities for positive and negative electrodes. The full cell was investigated by CV and charge/discharge measurements in the voltage window of 0 ~ 3.0 V at different scan rates and specific currents. All electrochemical measurements of three-electrode and two-electrode cells were carried out at 25 °C. The gravimetric specific energy and specific power of NaxH2–xTi2O5||NaMnO2•0.1H2O full cell were evaluated by the Eqs. 3 and 4:

where the C (mAh g−1) is the specific capacity based on the total weight of active materials of positive and negative electrodes, the Vcell (V) is obtained as the average discharge voltage, the E (Wh kg−1) is the gravimetric specific energy, and the P (W kg−1) is the gravimetric specific power.

DFT calculations

DFT calculations have been carried out on different structural models for birnessites. Structural optimizations based on DFT were carried out with the plane-wave basis set Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP) code53,54. The generalized gradient approximation with the function described by Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof was used throughout55. A kinetic energy cutoff of 450 eV was used in the simulations. For geometry relaxation calculations, the Brillouin zone sampling used was 2 × 2 × 2 in the Monkhorst–Pack grid56. In the geometry optimization, the total energy was converged to 10−5 eV and the Hellmann-Feynman force on each relaxed atom was less than 0.02 eV Å−1. For binding energy calculations, the DFT-D3 method of Grimme was employed57, which included the effects of the van der Waals interactions. The diffusion and decomposition transition states were located by the climbing-image nudged elastic band (CI-NEB) method38, we chose 7 images on these paths with a force convergence of 0.05 eV/Å per atom.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Suo, L. et al. Water-in-salt” electrolyte enables high-voltage aqueous lithium-ion chemistries. Science 350, 938–943 (2015).

Yang, C. et al. 4.0 V aqueous Li-ion batteries. Joule 1, 122–132 (2017).

Chao, D. et al. An electrolytic Zn–MnO2 battery for high‐voltage and scalable energy storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 131, 7905–7910 (2019).

Chao, D. & Qiao, S. Z. Toward high-voltage aqueous batteries: super- or low-concentrated electrolyte? Joule 4, 1846–1851 (2020).

Chao, D. et al. Roadmap for advanced aqueous batteries: from design of materials to applications. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba4098 (2020).

Yu, M. et al. New insights into the operating voltage of aqueous supercapacitors. Chem. Eur. J. 24, 3639–3649 (2018).

Yamada, Y. et al. Hydrate-melt electrolytes for high-energy-density aqueous batteries. Nat. Energy 1, 16129 (2016).

Xie, J., Liang, Z. & Lu, Y. C. Molecular crowding electrolytes for high-voltage aqueous batteries. Nat. Mater. 19, 1006–1011 (2020).

Chao, D. et al. Atomic engineering catalyzed MnO2 electrolysis kinetics for a hybrid aqueous battery with high power and energy density. Adv. Mater. 32, 2001894 (2020).

Liu, C. et al. A high energy density aqueous battery achieved by dual dissolution/deposition reactions separated in acid‐alkaline electrolyte. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 1903589 (2020).

Chen, L. et al. High-voltage aqueous battery approaching 3 V using an acidic–alkaline double electrolyte. Chem. Commun. 49, 2204–2206 (2013).

Hwang, J. Y. et al. Next‐generation activated carbon supercapacitors: a simple step in electrode processing leads to remarkable gains in energy density. Adv. Funct. Mater. 27, 1605745 (2017).

Hou, Z. et al. Passivation effect for current collectors enables high-voltage aqueous sodium ion batteries. Mater. Today Energy 14, 100337 (2019).

Zhang, X. et al. Na-birnessite with high capacity and long cycle life for rechargeable aqueous sodium-ion battery cathode electrodes. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 856–860 (2016).

Jabeen, N. et al. High‐performance 2.6 V aqueous asymmetric supercapacitors based on in situ formed Na0.5MnO2 nanosheet assembled nanowall arrays. Adv. Mater. 29, 1700804 (2017).

Yadav, G. G. et al. Regenerable Cu-intercalated MnO2 layered cathode for highly cyclable energy dense batteries. Nat. Commun. 8, 14424 (2017).

Shan, X. et al. Structural water and disordered structure promote aqueous sodium-ion energy storage in sodium-birnessite. Nat. Commun. 10, 4975 (2019).

Young, M. J. et al. Charge storage in cation incorporated α-MnO2. Chem. Mater. 27, 1172–1180 (2015).

Jabeen, N. et al. Enhanced pseudocapacitive performance of α-MnO2 by cation preinsertion. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 33732–33740 (2016).

Zhang, X. et al. Silver‐quantum‐dot‐modified MoO3 and MnO2 paper‐like freestanding films for flexible solid‐state asymmetric supercapacitors. Small 15, 1805235 (2019).

Shan, X. et al. High purity Mn5O8 nanoparticles with a high overpotential to gas evolution reactions for high voltage aqueous sodium-ion electrochemical storage. Front. Energy 11, 383–400 (2017).

Shan, X. et al. Bivalence Mn5O8 with hydroxylated interphase for high-voltage aqueous sodium-ion storage. Nat. Commun. 7, 13370 (2016).

Chan, Z. M. et al. Electrochemical trapping of metastable Mn3+ ions for activation of MnO2 oxygen evolution catalysts. PNAS 115, E5261–E5268 (2018).

Peng, H. et al. Redox properties of birnessite from a defect perspective. PNAS 114, 9523–9528 (2017).

Xia, H. et al. A monoclinic polymorph of sodium birnessite for ultrafast and ultrastable sodium ion storage. Nat. Commun. 9, 5100 (2018).

Zhou, G. et al. Mn ion dissolution mechanism for lithium-ion battery with LiMn2O4 cathode: in situ ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy and ab initio molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 3051–3057 (2020).

Seymour, I. D., Wales, D. J. & Grey, C. P. Preventing structural rearrangements on battery cycling: a first-principles investigation of the effect of dopants on the migration barriers in layered Li0.5MnO2. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 19521–19530 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. Ti-substituted tunnel-type Na0.44MnO2 oxide as a negative electrode for aqueous sodium-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 6, 6401 (2015).

Wang, J. et al. Pseudocapacitive contributions to electrochemical energy storage in TiO2 (anatase) nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 111, 14925–14931 (2017).

Tang, Y. et al. A highly ordered multi-layered hydrogenated TiO2-II phase nanowire array negative electrode for 2.4 V aqueous asymmetric supercapacitors with high energy density and long cycle life. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 623–632 (2018).

Guo, W. et al. TiO2 nanowire arrays on titanium substrate as a novel binder-free negative electrode for asymmetric supercapacitor. Electrochim. Acta 229, 197–207 (2017).

Xu, J. et al. Fabrication and characterization of potassium and sodium titanate via a hydrothermal method. J. Chem. Soc. Pak. 36, 388–393 (2014).

Que, L. F. et al. Thermal-induced interlayer defect engineering toward super high-performance sodium ion capacitors. Nano Energy 59, 17–25 (2019).

Que, L. F. et al. Robust and conductive Na2Ti2O5–x nanowire arrays for high-performance flexible sodium-ion capacitor. Chem. Mater. 29, 9133–9141 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. A hierarchical interconnected nanosheet structure of porous δ-MnO2 on graphite paper as cathode with a broad potential window for NaNO3 aqueous electrolyte supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 3, 2614–2622 (2020).

Li, Z. et al. Towards high power high energy aqueous sodium‐ion batteries: the NaTi2(PO4)3/Na0.44MnO2 system. Adv. Energy Mater. 3, 290–294 (2013).

Hou, Z. et al. An aqueous rechargeable sodium ion battery based on a NaMnO2–NaTi2(PO4)3 hybrid system for stationary energy storage. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 1400–1404 (2015).

Kang, Q. et al. Effect of interlayer spacing on the activity of layered manganese oxide bilayer catalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 1863–1870 (2017).

Thenuwara, A. C. et al. Copper-intercalated birnessite as a water oxidation catalyst. Langmuir 31, 12807–12813 (2015).

Shinagawa, T., Garcia-Esparza, A. T. & Takanabe, K. Insight on Tafel slopes from a microkinetic analysis of aqueous electrocatalysis for energy conversion. Sci. Rep. 5, 13801 (2015).

Man, I. C. et al. Universality in oxygen evolution electrocatalysis on oxide surfaces. ChemCatChem 3, 1159–1165 (2011).

Ling, T. et al. Engineering surface atomic structure of single-crystal cobalt (II) oxide nanorods for superior electrocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 7, 12876 (2016).

Wang, J. et al. The effect of manganese vacancy in birnessite-type MnO2 on room-temperature oxidation of formaldehyde in air. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 204, 147–155 (2017).

Liu, S. et al. Highly c-disordered birnessite with abundant out-of-layer oxygen vacancies for enhanced ozone catalytic decomposition. Sep. Purif. Technol. 322, 124254 (2023).

De Groot, F. M. F. et al. Oxygen 1s x-ray-absorption edges of transition-metal oxides. Phys. Rev. B 40, 5715–5723 (1989).

Lee, J. et al. Reversible Mn2+/Mn4+ double redox in lithium-excess cathode materials. Nature 556, 185–190 (2018).

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P. & Jónsson, H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Zhao, Y. et al. High-Na-content birnessite via P′3-stacking with tunable active facets for advanced aqueous sodium-ion batteries. ACS Nano 18, 32556–32568 (2024).

Tsuchimoto, A. et al. Nonpolarizing oxygen-redox capacity without O-O dimerization in Na2Mn3O7. Nat. Commun. 12, 631 (2021).

Kitchaev, D. A., Vinckeviciute, J. & Van der Ven, A. Delocalized metal–oxygen π-redox is the origin of anomalous nonhysteretic capacity in Li-ion and Na-ion cathode materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 1908–1916 (2021).

Seymour, I. D. et al. Mapping structural changes in electrode materials: application of the hybrid eigenvector-following density functional theory (DFT) method to layered Li0.5MnO2. Chem. Mater. 27, 5550–5561 (2015).

Zhu, X. et al. LiMnO2 cathode stabilized by interfacial orbital ordering for sustainable lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Sustain. 4, 392–401 (2021).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Grimme, S. et al. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 52272218 H.X., 22309088 X.Z., 52373245 J.X. and 52025025 L.G.), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (No. BK20210345 X.Z.), the Jiangsu Province Carbon Peak and Neutrality Innovation Program (Industry tackling on prospect and key technology, No. BE2022002‐4 H.X.), the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFB2404400 L.G.), the Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by Jiangsu Association for Science and Technology (No. JSTJ-2024-058 X.Z.), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Nos. 2024T170426 X.Z. and 2023M741772 X.Z.), and the Startup Foundation for Introducing Talent of NUIST (No. 2023r036 X.Z.). All authors thank the Nanjing University of Science and Technology for XRD and FESEM measurements, the Nanjing Jincaixin Technology Co., Ltd for the PDF characterizations, and the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility for sXAS characterizations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.X. supervised and planned the project. X.Z., J.X., Y.Z., and T.C. synthesized the samples and performed electrochemical measurements; Q.Z. and L.G. performed structural characterizations and data analysis; T.S. and S.L. performed DFT calculations; X.Z., J.X., and H.X. co-wrote the manuscript; all authors analyzed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

This research aligns with the Inclusion & ethics statement embraced by Nature Communications.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Boyu Shi, Naoaki Yabuuchi, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, X., Xu, J., Zhang, Q. et al. Regulating Na content and Mn defects in birnessite for high-voltage aqueous sodium-ion batteries. Nat Commun 16, 3838 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59223-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59223-1