Abstract

On September 11, 2023, Storm Daniel unleashed unprecedented rainfall over the Wadi Derna watershed, triggering one of the most devastating floods in modern history, striking Derna, a coastal city in Libya. This study reconstructs the disaster using an integrated modeling approach that combines satellite imagery, hydrologic, hydraulic, and geotechnical simulations, machine learning, eyewitness accounts, and digital elevation data to assess the impact of cascading dam failures. Our findings reveal that the region’s dams, even if structurally sound, would have provided minimal protection against the extreme runoff. However, their failure unleashed a destructive surge wave, amplifying the disaster’s magnitude and devastation. Here, we show that the collapse of aging flood control infrastructures, compounded by inadequate risk assessment and emergency preparedness, dramatically escalated the disaster’s impact. Our findings underscore the urgent need for systematic dam safety evaluations, enhanced flood forecasting, and adaptive risk management strategies that address climate extremes and infrastructure vulnerabilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

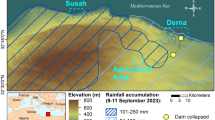

Derna is located at the end of a narrow valley, known as a wadi—an intermittently dry riverbed—where its geography and arid climate lead to flash floods and sparse vegetation. Derna faces distinctive challenges due to the predominantly arid nature of the wadi throughout most of the year, rendering it vulnerable to sudden and intense flash floods1. The Wadi Derna watershed, covering an area of 560 km2, is situated in the eastern region of Libya, east of the El Jebel El Akhdar area, and spans a distance of ~70 km to the west, running almost parallel to the Mediterranean coastline (Fig. 1). The Wadi originates from mountainous terrain, with an elevation of roughly 800 m above sea level, and eventually flows into the Mediterranean Sea after a 115 km-long course. Two dams, Bu Mansour and Al-Bilad, were constructed on the Wadi in the 1970s to protect Derna from flash flooding.

The watershed is delineated based on digital elevation model (DEM) data, with colors representing elevation (high: 843 m, low: 4 m). The blue diamonds (1–6) mark rainfall data extraction points used for hydrologic analysis. The Bu Mansour and Al-Bilad Dams are shown in purple, while Derna City is marked with a red star. The unconstructed dam site is indicated with a dashed purple line.

On September 10 and 11, 2023, Storm Daniel unleashed a torrential downpour, delivering an average of 350 mm of rainfall (95% confidence interval [CI]: 295.1–424.3 mm) within 24 h in the catchment of Wadi Derna. The resulting runoff filled the Derna Valley with a volume of water that far exceeded the capacity of the dams. Tragically, in the early hours of September 11, 2023, both dams gave way under immense pressure. The breach released flood waves several stories high, engulfing entire neighborhoods of Derna and sweeping them into the sea. This catastrophic event claimed an estimated 11,000–24,000 lives—up to 20% of the city’s population—leaving behind widespread destruction and heartbreak2,3,4,5,6.

Storm Daniel formed over the Ionian Sea as a low-pressure system due to a Europe-wide Omega block7. It crossed the Balkan Peninsula on September 4, 2023, causing severe damage and fatalities in Central Greece, Bulgaria, and Turkey from September 5–78,9. On September 9, it moved toward the Gulf of Sirte, drawing energy from unusually warm Mediterranean waters, likely driven by record-high July and August temperatures. Daniel intensified into a Mediterranean hurricane (Medicane) and made landfall along Libya’s eastern coast on September 10, 20238,10,11,12.

The storm moved southward, unleashing an unprecedented amount of precipitations in northeast Libya. Al-Bayda station (Latitude 32.75° and longitude 21.70°) that lies 20 km beyond the borders of the Wadi Derna Basin, recorded a total rainfall of 414.1 mm within 24 h1.

Derna has historically faced flash floods due to its location at the end of a highland ephemeral stream. Ashoor13 documented floods in Derna since 1942, when a flash flood caused severe losses for the German army. Major floods followed in 1956, 1959, and 1968. The October 1959 flood brought 146 mm of rain, causing significant damage. In response to the 1968 flood, the Libyan government commissioned a hydrologic study to develop flood control infrastructure. The Yugoslavian firm Hidroprojekt conducted the study and built two rock-filled dams with clay cores, along with supporting infrastructure for irrigation, transport, and water supply, completing construction in 197713.

The Bu Mansour and Al-Bilad dams were located in a geological area characterized by loamy soil, as confirmed by public reports and image data14. Bu Mansour lied about 14 km south of Derna City at an elevation of 220 m, while Al-Bilad was within the city limits at 50 m above sea level. The reported storage and height for Bu Mansour are 18 million cubic meters (MCM) and 75 m, and for Al-Bilad, 1.5 MCM and 45 m15. However, these values do not match the valley’s topography16. Analysis of digital elevation data indicates Bu Mansour’s height was ~42 m with a storage capacity of 22.5 MCM, while Al-Bilad’s storage of 1.5 MCM corresponds to a height of 24.5 m. A recent topographical survey by Ashoor confirmed these estimates17. Field observations after the Bu Mansour collapse suggested it held briefly before failing at an overtopping depth of <0.5 m, whereas Al-Bilad experienced several meters overtopping. Eyewitnesses, including the dam’s security guard, reported a 2 m overtopping at Bu Mansour at 2 a.m., 40 min before it failed3. Since the discovery of structural problems in the Bu Mansour Dam in the late 1980s, the dams underwent prolonged periods of neglect and disrepair, influenced by various factors3,18. While officials from the Tripoli-based government of Libya claim that the dams might have collapsed regardless of their structural health3, it is conceivable that structural deficiencies played a role in the catastrophic collapse shortly after the dam was overtopped.

The aftermath of the Derna disaster has raised numerous unanswered questions, with the most prominent being: did the dams fail due to prolonged neglect, or would their collapse have been inevitable given the unprecedented volume of precipitation? Was there a sense of complacency among residents in the floodplain influenced by a false sense of safety due to the presence of the dam? These pressing queries underscore the need for a rigorous quantitative analysis. Such efforts are essential to prevent similar tragedies in the future, especially in conflict zones3.

Previous research has emphasized the crucial role of social factors and targeted communication in flood preparedness, highlighting the need for proactive risk management strategies19,20,21,22,23. Effective disaster mitigation requires a balanced approach that integrates both structural and non-structural measures24,25,26. Recent advances in hydrologic, hydraulic, and geotechnical modeling have enhanced our understanding of dam failure mechanisms, particularly the impacts of multiple dam failures during extreme weather events27,28. In this study, we use these modeling techniques to examine the role of dam failures in Derna during Storm Daniel. Our analysis demonstrates how sustained rainfall triggered a series of dam failures, intensifying the flood impact. These findings demonstrate the urgency for improving dam maintenance, enhancing flood management, and bolstering community resilience.

First, we gather data from various sources, including media reports and published works in English and Arabic, digital elevation models (DEMs), and satellite data and images. Second, using this information, we conduct hydrologic, hydraulic, and geotechnical modeling, complemented by machine learning-based satellite image analysis. We evaluate scenarios ranging from no dam failure to overtopping without structural breach, to full dam breaches with potential cascading effects. By integrating disparate data sources and employing a combination of advanced modeling techniques, we provide a comprehensive reconstruction of the disaster in a conflict zone where conventional data are limited.

Results

Rainfall, runoff, and flooding

Using the model configurations specified in the “Methods” section, rainfall data for September 8–13 was analyzed across six locations in the Wadi Derna watershed (points 1–6 in Fig. 1) revealing significant spatial and temporal variations. The corresponding rainfall hyetographs are shown in Fig. 2. The cumulative rainfall during this period ranged from 308–432 mm, with the upper watershed (points 1–4) experiencing notably higher totals compared to the lower watershed (points 5 and 6). The average cumulative rainfall depth across all locations was 350 mm. To assess rainfall data variability, a bootstrapping method29 was applied to generate confidence intervals at 50th, 90th, 95th, and 99th levels (Fig. 2g), offering a measure of uncertainty around the mean rainfall estimate.

a–f Hourly rainfall intensity (mm/hr) at six data extraction points (Points 1–6) based on the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) Integrated Multi-satellite Retrievals for GPM (IMERG) dataset. Rainfall values are sampled from 30-min resolution datasets to construct hourly intensity estimates. Each subplot presents the total accumulated rainfall (mm) and the geographic coordinates (latitude and longitude) of the extraction point. The data corresponds to September 10–11, 2023, covering the period of Storm Daniel’s landfall. Spatial variability in rainfall intensity highlights localized differences across the watershed. g Cumulative rainfall over the Wadi Derna watershed, showing the temporal evolution of accumulated rainfall (mm) from September 9–13, 2023. The shaded regions represent confidence intervals (CI) at 50%, 90%, 95%, and 99%, while the red line denotes the median rainfall estimate.

To give context, historical annual rainfall in the Derna station (latitude 32.76° and longitude 22.65°) has ranged from 280–500 mm over the past 56 years, and the 24-h rainfall with a 100-year return period was calculated at 120 mm30. Extrapolating from the Log-Pearson Type III frequency distribution fit by Osta and Masoud30, Storm Daniel’s precipitation in the Wadi Derna basin was found to have a return period exceeding 1000 years.

The hydrological modeling results using the Hydrologic Engineering Center’s Hydrologic Modeling System (HEC-HMS) software for Storm Daniel predicted the watershed’s runoff volume to be 160 MCM. The peak discharge reached a value of 4000 m3 s−1 at the Bu Mansour Dam at 2:27 a.m. on September 11, 2023, prior to the dam failure. The predicted overtopping time matches with the eyewitness accounts3. The total runoff generated by Storm Daniel in the Wadi Derna watershed was thus seven times greater than the capacity of the two dams combined. Figure 3a–c show the computed headwater elevation at the Bu Mansour and Al-Bilad dams. For the Al-Bilad dam, the headwater elevation may exhibit one or two peaks depending on which dam failed first.

Time series of headwater elevation (m) and flow rate (m3/s) simulated using the HEC-RAS hydrodynamic model for different dam breach sequences. a Bu Mansour Dam overtopped at 12:30 a.m. on September 11, 2023, and breached at 2:40 a.m., releasing a downstream flood wave. b Al-Bilad Dam overtopped at 12:50 a.m. but remained intact until breaching at 3:00 a.m. following the flood surge from Bu Mansour’s failure. c Al-Bilad Dam breached at 1:40 a.m. due to overtopping, independent of Bu Mansour, and later experienced additional flooding from Bu Mansour’s breach at 3:25 a.m. The red circles indicate overtopping, and the red triangles mark dam breach events. d Simulated flow hydrographs 1 km downstream of Al-Bilad Dam, comparing two failure sequences: Scenario 1 (solid blue line) represents Bu Mansour failing first, generating a surge that subsequently triggers Al-Bilad’s failure, and Scenario 2 (dashed red line) represents Al-Bilad failing first, producing an initial flow spike before the arrival of Bu Mansour’s flood wave.

Hydrodynamic simulations using the Hydrologic Engineering Center’s River Analysis System (HEC-RAS) were conducted to evaluate the impact of the extreme flood event in Derna City in September 2023. Four scenarios were examined to assess different dam failure and flood propagation mechanisms. In Scenario 1, based on eyewitness accounts3, the Bu Mansour Dam breach was initiated in the model at 2:40 a.m. on September 11, 2023, generating a surge wave that subsequently triggered the Al-Bilad Dam breach. In Scenario 2, the Bu Mansour Dam breach was initiated at the same time (2:40 a.m.), but the Al-Bilad Dam failed independently due to an overtopping depth of 4.5 m at 1:40 a.m. To further analyze the impact of the dams on flooding, Scenario 3 assumed both dams remained structurally intact, overtopping but not breaching. In Scenario 4, the dams were completely absent, resulting in unobstructed runoff directly reaching Derna City.

Figure 3d depicts the simulated volume flow rate one km downstream of the Al-Bilad dam for Scenarios 1 and 2. At 12:50 a.m., the Al-Bilad dam overtopped, causing a sharp increase in the flow rate. In Scenario 1, cascading dam failure led to a spike in the flow rate from 4600 m3 s−1 to 17,600 m3 s−1 within a span of less than 1 h. In Scenario 2, Al-Bilad Dam was independently breached, with an early peak flow rate of 5400 m3 s−1, followed by a larger peak of 16,100 m3 s−1 from the Bu Mansour dam failure.

Figure 4 shows simulated flood depths in the city for Scenarios 1, 3, and 4 along with a plot of flood depth classification. The flood depths resulting from these Scenarios are classified into seven color codes. The classified flood depths (in m) are further segmented into seven-pixel groups: 0.03–1, 1.01–2, 2.01–3, 3.01–4, 4.01–5.5, 5.51–9.0, and >9.01. The histogram in Fig. 4d provides a comparative analysis of flood depths among the three Scenarios under the classified pixel groups. Notably, severe flood conditions are evident under the “Dam Breach” (Scenario 1), with a substantial rise in flood depths observed in the floodplain and the Wadi Derna channel.

Maps show the spatial distribution of simulated flood depths (m) in Derna under three scenarios: a No dam scenario (Scenario 4), where the flood propagates without any obstruction; b Cascading dam failure (Scenario 1), where Bu Mansour and Al-Bilad Dams breach sequentially; and c No dam breach (Scenario 3), where both dams overtop but remain intact, mitigating peak flood depths. The color scale represents flood depths, ranging from 0.03 m to >9.01 m. Panel d presents a histogram of inundated area (km2) by flood depth category, comparing flood extents across all three scenarios. The results are derived from HEC-RAS hydrodynamic modeling.

The difference in inundation extent between the “No Dam Breach” (Scenario 3) and “No Dam” (Scenario 4) is only 1.9%, indicating minimal flood mitigation benefits from the dam infrastructure during extreme precipitation events. In contrast, the “Dam Breach” scenario shows a 45% increase in inundation extent compared to “No Dam”, signaling a substantial flood wave from dam failure sweeping through the city. The histogram in Fig. 4d reveals a marked increase in flood depths, especially in the 2.01–5.5 m range. Additionally, depths exceeding 9.01 m account for 18% of the inundated area in the “Dam Breach” scenario, versus 11% without the dams occurring primarily in the wadi.

Table 1 presents simulated water depth and flow rate inside (Point A) and outside the Wadi (Point B) in Fig. 4b in the City of Derna during peak flow under different scenarios. The water depths inside the Wadi are ~2 times greater in Scenarios 1 and 2 compared to Scenarios 3 and 4, but significantly greater (~7 times) in the overbank area. The differences between Scenarios 3 and 4 are nominal.

Assessment of model performance

The predicted flood levels were compared against post-event flood marks collected by Ashoor et al.31, recorded at 23 flood-impacted building locations. Details of the flood mark locations and heights are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 5 presents a comparison between simulated and observed flood levels at these locations. Validation metrics, including Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE), root mean squared error (RMSE), and mean absolute error (MAE), were used to assess model performance. The NSE of 0.57 indicates satisfactory agreement32, while RMSE and MAE values of 2.8 m and 2.41 m, respectively, reflect average deviations from observed levels.

Scatter plot comparing predicted and observed water surface elevations (WSE) at 23 flood mark locations. The blue markers represent observed flood marks, the red line is the linear regression fit, and the dashed green line indicates perfect agreement. Model performance is evaluated with RMSE = 2.8 m, NSE = 0.57, and coefficient of determination (R2) = 0.79.

Flood impact on building structures

Flood impacts on building structures were analyzed using Maxar satellite imagery from September 1333. The flood affected building was detected using change detection method34. The Maxar imagery was segmented to extract building footprints and cross-referenced with pre-event data using ArcGIS Pro. A Random Forest Classifier35, trained on over 200 samples (80% training, 20% testing), categorized buildings as either “Fully/Partially Destroyed” or “Undamaged”. The classification metrics, presented in Table 2, indicate the robustness of the method.

Figure 6 shows the mapped flood impact within a 3.5 km2 floodplain in Derna, assessing 2217 buildings. Of these, 862 were classified as “Fully/partially destroyed” (red circle) and 1355 as “Undamaged” but flood-affected (blue circle). Validation against HEC-RAS simulated flood inundation for 120 randomly selected “Fully/partially destroyed” buildings yielded a precision of 0.95, recall of 0.78, F1-score of 0.85, and overall accuracy of 0.76.

Maxar 30 cm resolution satellite image taken on September 13, 202333, shows the impact of dam breach flooding on building structures in Derna. Buildings are classified as undamaged but flood-affected (blue) or partially/fully damaged (red) using a change detection method34. The blue boundary represents the flooding extent. The top-right zoom-in panel highlights flood-affected but undamaged structures, while the bottom-right zoom-in panel focuses on partially and completely destroyed buildings along the left bank of Wadi Derna.

Discussion

The results indicate that the Bu Mansour dam failure was the primary cause of the catastrophic flooding, while the Al-Bilad dam’s failure had a relatively minor impact. Intense precipitation would have resulted in flooding even without the dam failures, but the damage to property and loss of life would have been significantly lower. The concentrated runoff from Storm Daniel, within a brief period, meant that the presence of the dams—even if they could withstand overtopping—would have marginal benefits.

We performed a finite element analysis on seepage and deformation scenarios in a 2D model of the Bu Mansour dam— both with and without cracks in its clay core—to assess the impact of poor maintenance on potential sudden failure. The geotechnical modeling identifies four potential phases leading to the failure of the Bu Mansour dam.

Seepage flow across these four phases is illustrated in Fig. 7. Phase I represents the period before any precipitation, during which the reservoir is dry and the dam remains stable. Phase II occurs during extreme rainfall, causing the reservoir to form upstream, saturating the upstream rockfill and partially saturating the core. In Phase III, the reservoir reaches its maximum capacity, leading to overtopping. Poor structural conditions in the core allow for significant seepage within the clay, raising the risk of piping failure. Cracks in the dam exacerbate seepage, further compromising structural integrity. Phase IV marks severe damage to the downstream rockfill slopes due to overtopping, with overflow rates causing breach conditions within an hour. High seepage and the development of piping significantly accelerated this breach.

Comparison of cross-sectional seepage between a well-maintained dam (left) and a poorly maintained dam (right). a Phase I—dry condition (September 10, 6:00 p.m.: no seepage occurs in either case, with the dam structure remaining stable. b Phase II–half-full reservoir (September 10, 10:00 p.m.): no significant differences between the poorly maintained and properly maintained dams at this stage. c Phase III—full reservoir (September 11, 12:50 a.m.): Seepage pressure increases, with water passing through the core in the poorly maintained case, indicating structural weakness. d Phase IV—overtopping and breach initiation (September 11, 2:40 a.m.): the poorly maintained dam experiences high saturation, reaching a steady-state seepage condition, accelerating internal erosion and potential structural failure. e Stability analysis at Phase IV: the well-maintained dam remains marginally stable at FS = 1.11, while the poorly maintained dam shows a fully developed slip surface with FS = 1.07, indicating imminent failure. The color scale represents saturation (a–d) and deflection (e), with red indicating high deformation and structural instability.

The dam’s displacement due to internal flow during Phase IV is shown in Fig. 7e. In both scenarios, the factor of safety decreases, more notably in the poorly maintained dam. In the case of the poorly maintained dam, a significant slip surface develops, indicating imminent failure. While a well-maintained dam might eventually fail due to surface erosion, the time to failure would be longer, allowing more time for evacuation.

The Yugoslavian company estimated the 1000-year and 10,000-year flood volumes for the Bu Mansour dam to be 14 MCM and 22.5 MCM, respectively31. However, their 1972 report recommended a flood mitigation strategy involving three dams: Bu Mansour, Al-Bilad, and a third dam that was never constructed. Had this third dam been built, the contributing watershed to Bu Mansour would have been reduced to 140 km2, instead of the current 466 km2. In a 2003 assessment, the Swiss firm Stucky used alternative methodologies to estimate flood volumes and found the Yugoslavian estimates to be significantly lower than the required design capacity31,36.

To evaluate the potential impact of a third dam on hydraulic loading at Bu Mansour, we simulated runoff using a hypothetical 200 mm rainfall event over the entire 466 km2 watershed, employing the SCS-II rainfall model with a curve number (CN) of 81.3. The calculated total runoff volume at the Bu Mansour dam site was 67 MCM—three times the dam’s current capacity. If a third dam were operational, it would intercept 47.5 MCM of this runoff, reducing the volume reaching Bu Mansour to 19 MCM. Under extreme events, such as Storm Daniel, the third dam could retain up to 111 MCM, limiting the runoff volume to Bu Mansour to 39 MCM. While this remaining volume still exceeds the dam’s capacity, it would significantly reduce the hydraulic pressure on Bu Mansour.

Flood management often relies on structural measures like levees and reservoirs36. However, exclusive reliance can create a cycle where increased protection promotes urbanization in floodplains, escalating the demand for even higher protection standards, as seen in the Netherlands37. Elevated protection levels can also foster a false sense of security, reducing preparedness and increasing vulnerability36,38. In Derna, extensive development in the Wadi bed and complacency among residents and officials exemplified this “flood control paradox”. Despite structural concerns, Wadi Derna’s dams survived two significant storms in 1986 and 2011 without failure. A survivor recalled similar flooding in 2011 that did not lead to catastrophe39. The disaster was exacerbated by missed warnings, inadequate disaster preparedness, and evacuations focused on coastal areas instead of the floodplain. Effective warnings and evacuations could have prevented most casualties, according to the World Meteorological Organization’s head40.

Global concerns about dam safety are rising due to increasing extreme weather and heavy rainfall41. The Derna disaster highlights how dam failure can trigger rapid, catastrophic flooding, emphasizing the need for dam rehabilitation, climate-resilient infrastructure, and thorough risk assessments. While climate change heightens safety risks, the economic benefits of dams remain substantial42. The lessons from Derna underscore the need for enhanced safety standards, comprehensive evacuation plans, and a balanced approach between structural measures and public risk perception.

The input datasets and models used in this study contain inherent uncertainties, particularly in a data-scarce region like the Derna watershed. Spatial rainfall estimates, especially from satellite sources such as GPM and GSMaP, are subject to systematic and random errors due to limitations in retrieval algorithms, spatiotemporal sampling, and atmospheric adjustments, often resulting in underestimations or overestimations of rainfall43. Terrain-dependent errors in quantitative precipitation estimates are also noted in coastal and mountainous regions, which apply to the Derna watershed44. Among the DEMs tested—SRTM, JAXA-ALOS, FABDEM, and MERIT—JAXA-ALOS demonstrated the best fit to the study area’s topography, aligning closely with reported reservoir capacities and thus being selected for final modeling. The hydrologic and hydrodynamic models were calibrated to incorporate these diverse rainfall datasets and topographic inputs, with additional adjustments to roughness values based on local conditions and validation against available ground observations. Despite data constraints, this approach enhances the reliability of model outputs, providing valuable insights for flood prediction and preparedness in regions with limited resources.

The Derna case underscores the need for prioritized flood management over purely structural solutions. This includes monitoring infrastructure and water levels, especially as extreme weather events become more frequent. Comprehensive inspections, remote monitoring, and proactive maintenance are crucial, along with clear evacuation plans and robust public communication. These measures aim to build a holistic disaster management approach that minimizes risks and enhances community preparedness.

Methods

This study reconstructed the Derna flood event using an integrated approach that combined hydrological, hydraulic, and geotechnical analyses. Numerical modeling was performed using spatial and temporal data processed in GIS software. The HEC-HMS hydrological model generated runoff from rainfall data, which was then routed in the HEC-RAS hydraulic model to simulate flood routing and dam breach. The geotechnical behavior of the dam under progressive hydraulic loading was evaluated using Plaxis 2D. Model calibration and validation used data from eyewitness accounts, news reports, ground photos, flood marks, and satellite images.

Hydrological analysis

The hydrologic analysis for the Derna watershed involved four key steps: (1) DEMs processing, (2) watershed delineation, (3) parameterization, and (4) storm rainfall-runoff simulation. Different DEMs were compared from various sources, including the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM)45, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s Advanced Land Observing Satellite (JAXA-ALOS) version 3.246, the Forest And Buildings removed (FABDEM)47,48, and the Multi-Error-Removed (MERIT)49. The best resolution available for the Derna watershed was 30 m, making SRTM, JAXA-ALOS, and FABDEM the primary choices. The SRTM DEM showed lower resolution than other DEMs, and studies confirmed that JAXA-ALOS has higher accuracy than SRTM50,51. JAXA-ALOS 30 m was selected for modeling after accuracy assessments showed its reservoir capacity estimates were consistent with reported data13,15, unlike FABDEM, which overestimated the Al-Bilad reservoir capacity.

Precipitation data for September 8–13 were collected from GPM IMERG, with additional data from GSMaP and ERA552,53. These satellite datasets were validated against a ground observation station at Roaya-Sirte54, where GPM IMERG showed the closest alignment, while ERA5 tended to overestimate and GSMaP to underestimate rainfall (Fig. 8, Table 3). Rainfall data were extracted at six key locations across the watershed using Google Earth Engine, generating six time series for hydrologic modeling (Fig. 2).

Cumulative rainfall (mm) recorded from ground observations and three different precipitation datasets—GPM IMERG (solid blue line), GSMaP (black line), and ERA5 (solid green line)—during the storm event. The ground observation data (solid orange line), recorded at Roaya-Sirte, Libya (31.204999°N, 16.599°E), serves as a reference for evaluating the accuracy of satellite and reanalysis products.

HEC-HMS55 was used for the rainfall-runoff analysis. The watershed, delineated using JAXA-ALOS DEM46, covered 560 km2, and subbasins were defined for enhanced modeling precision using WMS software56. Subbasin properties like slope and time of concentration were calculated, with runoff losses estimated using the NRCS CN method57. A CN value of 81.3 was adopted for the Wadi Derna watershed, as recommended by Ashoor13 based on analyses of geological, soil, and land cover characteristics in the region. This CN value corresponds to the antecedent moisture condition level II (AMC II), which represents typical or normal soil moisture conditions prior to a storm. Schneider and McCuen58 have noted that AMC II values provide the most accurate CN estimates for a watershed. To further confirm pre-storm moisture conditions, an NDWI (Normalized Difference Water Index) analysis was conducted using Landsat Sentinel-2 imagery59,60. While several studies (e.g., Merz and Plate61, Castillo et al.62, Brocca et al.63, Gamage et al.64) suggest that initial moisture conditions may be less impactful during extreme events, the selected CN value offers a reliable baseline for this analysis.

Rainfall-runoff transformation was performed using the SCS unit hydrograph method, while flood routing in Bu Mansour Dam’s watershed employed the Muskingum-Cunge method65. Given the rapid changes in flow caused by dam breaches, HEC-RAS was utilized to model flood propagation and inundation over a 105 km2 area downstream of Bu Mansour Dam. Various Manning roughness values, as per Chow66, ranging from 0.03 to 0.05 s m−1/3 for mountainous streams, were initially tested. Eyewitness accounts indicated that the Bu Mansour reservoir was completely dry by sunset (~6:30 p.m.) and began filling by 8 p.m., reaching critical levels after midnight and persisting until 2 a.m.3. This information guided the calibration process, resulting in an optimal calibrated Manning’s n value of 0.04 for the channel reaches. The time of concentration was determined using the Kirpich equation67, with the lag time set at 60% of the calculated time of concentration68,69.

The Supplementary Information includes comprehensive hydrological data supporting this analysis. Key details cover subbasin parameters (Table S1), cumulative rainfall distribution (Fig. S1), DEM-based dam storage curves (Fig. S2), subbasin delineations (Fig. S3), and WMS watershed segmentation (Fig. S4). The HEC-HMS hydrological model and related data, including rainfall intensities, and hydrographs, are shown in Figs. S5 and S6. Sentinel-2-derived NDWI data (Fig. S7) further support the findings.

Error adjustment of GPM rainfall data

To address spatial error dependencies in GPM rainfall data, we employed bivariate copulas, a method commonly used for quantifying uncertainty by modeling probability distributions. Observed biases were first calculated as the difference between GPM rainfall and observed rainfall estimates (ORE) using an additive error formulation: \({P}_{BAR{E}_{i}}={P}_{OR{E}_{i}}+\epsilon\), where \({P}_{BAR{E}_{i}}\) represents the bias-adjusted rainfall estimate (BARE) for each pixel. The biases at each rainfall gauge were then fitted to their optimal marginal distribution, determined by the Anderson-Darling test at a 5% significance level. Cumulative distribution functions for the biases were calculated per gauge.

Four bivariate copulas—Gaussian70,71, t-copula72, Clayton73, and Frank74,75—were evaluated, with the t-copula selected based on the lowest AIC and BIC values, as shown in Table 4. Assuming independence of biases across pixels, the t-copula model was used to generate 1000 ensemble samples per pixel, with outliers removed using Mahalanobis distance76. Finally, the simulated biases were added to the GPM data to produce the Bias-Adjusted Rainfall Estimate (BARE), which was subsequently applied in hydrological and flood modeling.

Dam break flood simulation

A 2D hydrodynamic flood model was developed using HEC-RAS software77 to simulate dam break events and model flood routing and inundation. The simulation used 2D shallow water equations with the Eulerian-Lagrangian method (SWE-ELM) and covered a 105 km2 floodplain extending from Bu Mansour Dam to the coastline.

The model incorporated the 30 m JAXA-ALOS DEM, dam storage curves, and the inflow hydrograph at Bu Mansour Dam derived from HEC-HMS hydrologic modeling, which includes simulations of rainfall-runoff processes and channel routings in the watershed. Excess rainfall from Point 6, calculated via the SCS-CN method57, was applied uniformly to the 2D mesh, using a weighted CN value of 81.3. The total rainfall over 48 h (September 10–11) was 361 mm, with 61 mm of initial abstraction losses and 300 mm of excess rainfall.

The simulation used a 5-s time step, with a 25 m grid for most of the floodplain and a 15 m grid near Derna. The breach formation times were calculated using various empirical equations (Froehlich, MacDonald, Von Thun and Gillette, Xu and Zhang)78,79,80,81,82. The Von Thun and Gillette equation yielded the most accurate flood arrival times compared to eyewitness reports3,39, estimating breach times of 58 min for Bu Mansour Dam and 38 min for Al-Bilad Dam. The breach at Bu Mansour Dam was initiated at 2:40 a.m. on September 11, according to eyewitness accounts3. The breach initiation in the HEC-RAS of the Al-Bilad Dam varied by scenario. In Scenario 1, the dam breached when the overtopping depth reached 6.5 m, driven by the surge wave from the Bu Mansour Dam breach, occurring at ~3:00 a.m. on September 11, 2023. In Scenario 2, the Al-Bilad Dam breached independently at 1:40 a.m. due to sustained overtopping conditions. Scenario 3 explored the impact of both dams maintaining structural integrity, while Scenario 4 assumed the dams were absent altogether. The modeling domain for HEC-RAS dam break simulations is shown in Fig. S8 in the Supplementary Information section.

Geotechnical analysis

The geotechnical stability of the Bu Mansour Dam was assessed through a coupled flow and stability analysis, integrating flood hydrographs derived from the hydrologic model. The simulation was conducted using Plaxis 2D, a finite element method (FEM) geotechnical software known for its capability in capturing complex soil-structure interactions83. A plane strain model with 15-noded elements and medium mesh refinement was applied to optimize computational efficiency while maintaining precision.

The dam’s rockfill embankment included a clay core designed to control seepage; however, inadequate maintenance may have compromised its integrity. To simulate this, a high-permeability zone was introduced within the clay core to represent potential cracking conditions13. Dam height and elevation data were obtained from DEM inputs. The analysis considered four primary soil layers: cracked clay core (representing poor maintenance), intact clay core, loam soil, and rockfill. Key soil properties—including unit weight, void ratio, suction, shear strength, and permeability—were derived from relevant literature14 (see Table 5).

The simulation was divided into four phases to evaluate the dam’s response to incremental hydraulic loading: (i) initial dry condition, (ii) reservoir half-full, (iii) full reservoir with overtopping initiation, and (iv) dam breach condition. The dry phase represented the initial state without flooding from Storm Daniel, spanning from 06:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m. The second phase began at 10:00 p.m. when the reservoir reached half-full, simulated until 12:50 a.m. (a duration of 2 h and 50 min). The full reservoir phase lasted 110 min, ending at 02:40 a.m. when overtopping and breach initiation occurred. The final breach phase extended for 150 min, concluding as rainfall subsided.

A flood hydrograph was applied as the upstream boundary condition, incorporating height and elevation data derived from the DEM. These stages provided detailed insights into the dam’s behavior under varying hydraulic and structural stress conditions. Full model geometry details and structural specifications are provided in the Supplementary Information (SI).

Data availability

All data used in this study are publicly available and accessible through open-access sources. The satellite datasets, including Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) IMERG and Global Satellite Mapping of Precipitation (GSMaP), can be obtained from NASA’s Earth Observing System Data and Information System (EOSDIS) (https://earthdata.nasa.gov/). The ERA5-Land dataset is provided by the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS) and is available at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/. Maxar high-resolution satellite imagery can be requested through Maxar’s platform (https://www.maxar.com/). The DEMs, including JAXA-ALOS, are publicly available through their respective repositories. Specific HEC-RAS model outputs, geospatial datasets, and simulation results are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Additional relevant data are provided in the Supplementary Information files or can be obtained upon request.

Code availability

This study primarily relied on publicly available and commercial software tools, including HEC-RAS (Hydrologic Engineering Center’s River Analysis System), HEC-HMS (Hydrologic Modeling System), ArcGIS (licensed version from Esri), Plaxis 2D (finite element modeling for geotechnical applications), and WMS (Watershed Modeling System) for hydrologic pre-processing. No custom code or mathematical algorithms were developed for this study. All analyses were conducted using the standard functionalities of the listed software.

References

Cassidy, E., Torrential rain wreaks havoc in Libya — earthobservatory.nasa.gov https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/151826/torrential-rain-wreaks-havoc-in-libya (2023).

Rim Taher. A year of rebuilding Libya’s flood-hit Derna was plagued by politics https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2024/09/year-rebuilding-libyas-flood-hit-derna-plagued-politics (2024).

Gazzini, C., When the dams in Libya Burst: a natural or preventable disaster?—crisisgroup.org. https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/north-africa/libya/when-dams-libya-burst-natural-or-preventable-disaster.

Flemming, L., Libya floods: entire neighbourhoods dragged into the sea—bbc.com. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-66785466.

Sky News. Libya: warning over shortage of body bags as disease may compound deaths in flood-hit city. https://news.sky.com/story/libya-warning-over-shortage-of-body-bags-as-disease-may-compound-deaths-in-flood-hit-city-12960801 (2023).

Patrick Smith. Libya floods: death toll in Derna rises as rescue efforts continue. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/libya-floods-death-toll-derna-rcna105001 (2023).

Detring, C., Müller, A., Schielicke, L., Névir, P. & Rust, H. W. Atmospheric blocking types: frequencies and transitions. Weather Clim. Dyn. Discuss. 2020, 1–33 (2020).

Daniel, the meteo-hydrological updates in Libya—CIMA Research Foundation—cimafoundation.org. https://www.cimafoundation.org/en/news/daniel-the-meteo-hydrological-updates-in-libya/.

Cohen, L., “Historic flooding event” in Greece dumps more than 2 feet of rain in just a few hours — cbsnews.com https://www.cbsnews.com/news/greece-historic-flooding-more-than-2-feet-of-rain-in-just-a-few-hours/ (2023).

CEAM. Mediterranean sea surface temperature trend https://www.ceam.es/ceamet/SST/SST-trend.html (2023).

Henson, B., Masters, J. The Libya floods: a climate and infrastructure catastrophe https://yaleclimateconnections.org/2023/09/the-libya-floods-a-climate-and-infrastructure-catastrophe/ (2023).

Loveluck, L., Ludwig, J., Chamaa, M.E., Dadouch, S. ‘Catastrophe’ in Libya’s Derna as deadly floods engulf city https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/10/05/libya-derna-floods-disaster-government/ (2023).

Ashoor, A. A. Estimation of the surface runoff depth of wadi derna basin by integrating the geographic information systems and soil conservation service (scs-cn) model. J. Pure Appl. Sci. 21, 90–100 (2022).

Abagandura, G. O., Park, D., White, D. & JR, W. C. B. Modelling soil degradation in Libya. J. Nat. Sci. Res. 7, 30–40 (2017).

Maksin, B., Wadi Derna—Libya - Hidrotehnika - Hidroenergetika a.d. — hidrotehnika.rs. https://www.hidrotehnika.rs/en/libya/wadi-derna/.

Petley, D., Further information about the Wadi Derna dams https://eos.org/thelandslideblog/further-information-about-the-wadi-derna-dams (2023).

Ashoor, A., Eladawy, A. Navigating catastrophe: lessons from Derna amid intensified flash floods in the anthropocene. Euro Mediterr. J. Environ. Integr. 9, 1125–1140 (2024).

Yee, V. Years of Graft doomed 2 dams in Libya, leaving thousands in muddy graves — nytimes.com https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/27/world/middleeast/libya-flooding-derna-corruption.html (2023).

Scolobig, A., De Marchi, B. & Borga, M. The missing link between flood risk awareness and preparedness: findings from case studies in an alpine region. Nat. Hazards 63, 499–520 (2012).

Burningham, K., Fielding, J. & Thrush, D. ‘It’ll never happen to me’: understanding public awareness of local flood risk. Disasters 32, 216–238 (2008).

Bodoque, J. M., Díez-Herrero, A., Amérigo, M., García, J. A. & Olcina, J. Enhancing flash flood risk perception and awareness of mitigation actions through risk communication: a pre-post survey design. J. Hydrol. 568, 769–779 (2019).

Maidl, E. & Buchecker, M. Raising risk preparedness by flood risk communication. Nat. Hazards Earth Sys. Sci. 15, 1577–1595 (2015).

Lechowska, E. What determines flood risk perception? A review of factors of flood risk perception and relations between its basic elements. Nat. Hazards 94, 1341–1366 (2018).

Meyer, V., Priest, S. & Kuhlicke, C. Economic evaluation of structural and non-structural flood risk management measures: examples from the Mulde River. Nat. Hazards 62, 301–324 (2012).

Dawson, R. J., Ball, T., Werritty, J., Werritty, A., Hall, J. W. & Roche, N. Assessing the effectiveness of non-structural flood management measures in the thames estuary under conditions of socio-economic and environmental change. Glob. Environ. Change 21, 628–646 (2011).

Schanze, J. et al. Systematisation, evaluation and context conditions of structural and non-structural measures for flood risk reduction. (CRUE Research report; No. I-1). CRUE Funding Initiative on Flood Risk Management Research. http://www.flood-era.ioer.de/files/FLOOD-ERA_Final_report.pdf (2008).

Salman, A. M. & Li, Y. Flood risk assessment, future trend modeling, and risk communication: a review of ongoing research. Nat. Hazards Rev. 19, 04018011 (2018).

Molinari, D., De Bruijn, K. M., Castillo-Rodríguez, J. T., Aronica, G. T. & Bouwer, L. M. Validation of flood risk models: current practice and possible improvements. Int. J. Dis. Risk Reduct. 33, 441–448 (2019).

Puth, M.-T., Neuhäuser, M. & Ruxton, G. D. On the variety of methods for calculating confidence intervals by bootstrapping. J. Anim. Ecol. 84, 892–897 (2015).

Osta, M. M. E. & Masoud, M. H. Implementation of a hydrologic model and GIS for estimating wadi runoff in Dernah area, Al Jabal Al Akhadar, NE Libya. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 107, 36–56 (2015).

Ashoor, A. & Eladawy, A. Watch and Upgrade or Deconstruct and Relocate: Derna Catastrophe Lessons Amid the Climate-change Era of Unpredictable Flash Floods, 17 January 2024, PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3858769/v1 (2024).

Moriasi, D. N., Gitau, M. W., Pai, N. & Daggupati, P. Hydrologic and water quality models: performance measures and evaluation criteria. Trans. ASABE 58, 1763–1785 (2015).

Maxar Technologies. Libya Floods September 2023. Maxar Open Data Program. (2023). https://www.maxar.com/open-data/libya-floods-0923. The imagery is used under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC 4.0) with attribution to Maxar Technologies. License details available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

Tanim, A. H., McRae, C. B., Tavakol-Davani, H. & Goharian, E. Flood detection in urban areas using satellite imagery and machine learning. Water 14, 1140 (2022).

Pal, M. Random forest classifier for remote sensing classification. Int. J. Remote Sens. 26, 217–222 (2005).

Di Baldassarre, G. et al. Hess opinions: an interdisciplinary research agenda to explore the unintended consequences of structural flood protection. Hydrol. Earth System Sci. 22, 5629–5637 (2018).

Di Baldassarre, G. et al. Socio-hydrology: conceptualising human-flood interactions. Hydrol. Earth System Sci. 17, 3295–3303 (2013).

Tobin, G. A. The levee love affair: a stormy relationship?1. JAWRA 31, 359–367 (1995).

Jaber, Z., Aggarwal, M., Smith, P. Why was the Libya flooding so deadly? — nbcnews.com https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/libya-flood-explained-conflict-corruption-climate-change-derna-dams-rcna105219 (2023).

Reuter. Casualties in Libya floods could have been avoided with warning system: WMO chief https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/casualties-libya-floods-could-have-been-avoided-with-warning-system-wmo-chief-2023-09-14/ (2023).

Choi, J.-H., Jun, C., Liu, P., Kim, J.-S. & Moon, Y.-I. Resolving emerging issues with aging dams under climate change projections. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 146, 04020025 (2020).

Beatty, S. et al. Rethinking refuges: implications of climate change for dam busting. Biol. Conserv. 209, 188–195 (2017).

Tian, Y., Peters-Lidard, C.D. A global map of uncertainties in satellite-based precipitation measurements. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, 24 (2010).

Tanim, A. H., Mullick, M. R. A. & Sikdar, M. S. Evaluation of spatial rainfall products in sparsely gauged region using copula uncertainty modeling with triple collocation. J. Hydrol. Eng. 26, 04021004 (2021).

Tozer, B. et al. Global bathymetry and topography at 15 arc sec: SRTM15+. Distributed by OpenTopography. https://doi.org/10.5069/G92R3PT9 (2019).

Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. ALOS World 3D 30 meter DEM, Version 3.2. Distributed by OpenTopography. https://doi.org/10.5069/G94M92HB (2021).

Neal, J., Hawker, L. FABDEM V1-2. University of Bristol. https://doi.org/10.5523/BRIS.S5HQMJCDJ8YO2IBZI9B4EW3SN (2023).

Hawker, L. et al. A 30 m global map of elevation with forests and buildings removed. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 024016 (2022).

Yamazaki, D. et al. A high-accuracy map of global terrain elevations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 5844–5853 (2017).

Zhang, K. et al. Accuracy assessment of aster, srtm, alos, and tdx dems for hispaniola and implications for mapping vulnerability to coastal flooding. Remote Sens. Environ. 225, 290–306 (2019).

Chymyrov, A. Comparison of different dems for hydrological studies in the mountainous areas. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 24, 587–594 (2021).

Kubota, T. et al. Global satellite mapping of precipitation (GSMaP) products in the GPM era. In Satellite Precipitation Measurement Vol. 1, 355–373 (Springer, 2020).

Muñoz Sabater, J. ERA5-Land hourly data from 1950 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS). https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.e2161bac. https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/ (2019).

Weather Underground. Weather history and data archive. https://www.wunderground.com/ (2023).

Feldman, A.D. Hydrologic Modeling System HEC-HMS: Technical Reference Manual. US Army Corps of Engineers, Hydrologic Engineering Center (2000).

WMS—The All-in-one Watershed Solution — Aquaveo.com — aquaveo.com. https://www.aquaveo.com/software/wms-watershed-modeling-system-introduction.

USDA-NRCS. Chapter 10: Estimation of direct runoff from storm rainfall. In NRCS National Engineering Handbook Part 630: Hydrology, Ch. 10 (USDA-NRCS, 2004).

Schneider, L. E. & McCuen, R. H. Statistical guidelines for curve number generation. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 131, 282–290 (2005).

Gao, B.-C. Ndwi-a normalized difference water index for remote sensing of vegetation liquid water from space. Remote Sens. Environ. 58, 257–266 (1996).

McFeeters, S. K. The use of the normalized difference water index (ndwi) in the delineation of open water features. Int. J. Remote Sens. 17, 1425–1432 (1996).

Merz, B. & Plate, E. J. An analysis of the effects of spatial variability of soil and soil moisture on runoff. Water Res. Res. 33, 2909–2922 (1997).

Castillo Sánchez, V.M., Gómez-Plaza, A., Martínez-Mena García, M.D. The role of antecedent soil water content in the runoff response of semiarid catchments: a simulation approach. J. Hydrol. 284, 114–130 (2003).

Brocca, L., Melone, F., Moramarco, T. & Singh, V. Assimilation of observed soil moisture data in storm rainfall-runoff modeling. J. Hydrol. Eng. 14, 153–165 (2009).

Gamage, S., Hewa, G. & Beecham, S. Modelling hydrological losses for varying rainfall and moisture conditions in south australian catchments. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 4, 1–21 (2015).

Cunge, J. A. On the subject of a flood propagation computation method (muskingum method). J. Hydraul. Res. 7, 205–230 (1969).

Te Chow, V. Open Channel Hydraulics (McGraw-Hill, 1959).

Kirpich, T. P. Time of concentration of small agricultural watersheds. J. Civ. Eng. 10, 362 (1940).

Mockus, V. Use of Storm and Watershed Characteristics in Synthetic Hydrograph Analysis and Application (American Geophysical Union, Pacific Southwest Region, 1957).

de Simas, M. J. C. Lag-time characteristics in small watersheds in the United States (Doctoral dissertation, University of Arizona). ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (Publication No. 9713386). Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/lag-time-characteristics-small-watersheds-united/docview/304298378/se-2 (1996).

AghaKouchak, A., Bárdossy, A. & Habib, E. Copula-based uncertainty modelling: application to multisensor precipitation estimates. Hydrol. Process. 24, 2111–2124 (2010).

Žežula, I. On multivariate Gaussian copulas. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 139, 3942–3946 (2009).

Demarta, S. & McNeil, A. J. The t copula and related copulas. Int. Stat. Rev. 73, 111–129 (2005).

McNeil, A. J. Sampling nested archimedean copulas. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 78, 567–581 (2008).

Hofert, M., Mächler, M. & McNeil, A. J. Likelihood inference for archimedean copulas in high dimensions under known margins. J. Multivar. Anal. 110, 133–150 (2012).

Liebscher, E. Fitting copulas in the case of missing data. Stat. Papers 65, 3681–3711 (2024).

De Maesschalck, R., Candolfi, A., Massart, D. & Heuerding, S. Decision criteria for soft independent modelling of class analogy applied to near infrared data. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 47, 65–77 (1999).

Hydraulic Engineering Center. HEC-RAS River Analysis System https://www.hec.usace.army.mil/software/hec-ras/documentation/HEC-RAS_Users_Manual_65_Beta.pdf (2023).

Froehlich, D.C. Embankment dam breach parameters revisited. In Proc. Conference on Water Resources Engineering (ASCE, 1995).

Froehlich, D. C. Embankment dam breach parameters and their uncertainties. J. Hydraul. Eng. 134, 1708–1721 (2008).

MacDonald, T. C. & Langridge-Monopolis, J. Breaching characteristics of dam failures. J. Hydraul. Eng. 110, 567–586 (1984).

Von Thun, J.L., Gillette, D.R. Guidance on Breach Parameters. Internal Memorandum (U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation,1990).

Xu, Y. & Zhang, L. M. Breaching parameters for earth and rockfill dams. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 135, 1957–1970 (2009).

Brinkgreve, R., Broere, W., Waterman, D. PLAXIS 2D-Version 8 Tutorial Manual (Plaxisbv, 2006).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge funding support from the National Science Foundation (NSF) (Award #2152896), received by J.I. and S.K., and the Engineering Research and Development Center (ERDC), U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Funding #W912HZ21C0067, M. H. Chaudhry, PI), received by J.I. and E.G.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.I. conceptualized and led the study. A.M.N., A.H.T., A.N., S.K., and E.G. performed data gathering, modeling, analysis, writing, and reviewing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Heather Golden, Christian Massari, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nemnem, A.M., Tanim, A.H., Nahian, A. et al. How extreme rainfall and failing dams unleashed the Derna flood disaster. Nat Commun 16, 4191 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59261-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59261-9