Abstract

Heat is known to have harmful impacts on health; however, little is known about its impact on people with disabilities. We evaluate the association between heat and hospitalization through the emergency department among people with and without disabilities. We adopt a case-crossover design using 16 years (2006–2021) of claims data from the Korean National Health Insurance Service Database. A total of 584,743 admissions are recorded among people with disabilities. The heat risk (odds ratio) is 1.10 (95% confidence interval: 1.08–1.13) in people with disabilities. The relative heat risk between people with and without disabilities is 1.33 (95% confidence interval: 1.29–1.37). Within the population with disabilities, individuals with brain lesion disorders, intellectual and mental disabilities, or living in areas with low-middle population density exhibit higher heat risks than the total people with disabilities. Here, we show evidence of different heat risks between people with and without disabilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing frequency, intensity, and duration of extreme heat events are causing worldwide morbidity, mortality, and damage to ecosystems1. Numerous studies have identified the hazardous impacts of extreme heat on human health, including premature death, mental disorders, and cardiovascular, respiratory, and genitourinary diseases2,3,4,5,6. The heat mortality/morbidity associations have been studied in different continents, countries, populations, and vulnerable populations such as low-income group or minority ethnicities or cultures; although most associations are positive, they are uneven. Older adults who are aged 65 and older, individuals with lower income, and ethnic or cultural minorities are particularly vulnerable to heat due to biological and/or social factors4.

However, people with disabilities who have impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions owing to environmental and personal factors7 have rarely been investigated although they account for approximately 16% of the global population8. Some hypotheses suggest that people with disabilities have a higher risk of heat exposure. First, people with disabilities are at a higher risk because of their limited access to information, transportation, and medical services9. Second, certain medications and reduced heat-regulating mechanisms may hinder physical acclimatization to higher temperatures10,11. Finally, people with disabilities might have a lower socioeconomic status than those without disabilities owing to lower educational opportunities and limitations in socioeconomic activities8,12,13. This may result in ineffective management of heat because low socioeconomic status has been addressed as a representative risk factor4,10.

Studies that measure the risk of heat in people with disabilities are highly limited owing to the scarcity of data. Moreover, although some previous studies examined heat impacts by disability type, evidence of the different risks by causes of hospital admissions, demographic characteristics such as sex and age, and district-level characteristics are still substantially limited14,15. Furthermore, although baseline medical costs are higher among the population with disabilities compared to those without16, the economic burden attributable to heat within this population is likely underestimated.

In this work, to address these gaps in knowledge, we perform a nationwide study to investigate the impact of heat on hospitalization in people with disabilities living in South Korea (hereafter referred to as Korea) with different types of disabilities, sociodemographic statuses, and causes of admission. Furthermore, this study estimates the hospitalization costs attributable to heat exposure in people with disabilities to measure the corresponding economic burden quantitatively. We find a higher association between heat and hospitalization through the emergency department in people with disabilities than in people without disabilities.

Results

Descriptive results

Overall, 584,743 hospitalizations through the emergency department (ED admission) for cardiovascular, genitourinary, and respiratory diseases, and mental disorders among 3,652,016 persons with disabilities were recorded during the warm season spanning 2006–2021 (Table 1). The mean temperature of the study period was 22.7 °C (standard deviation (SD): 3.0). The mean age at ED admission was 66.1 years (SD: 17.0) for people with disabilities (Supplementary Table 1). The yearly baseline rates of ED admissions and ED admission costs during the warm season were highest among people with brain lesion disorders and mental disability within the population with disabilities (Supplementary Table 2). The demographic distributions of ED admissions, such as age and sex, were similar between disability groups and their corresponding control groups (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4).

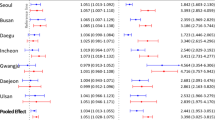

Association by disability status and type

Figure 1 shows the odds ratio and relative odds ratio (ROR) of total ED admissions and the excess ED admission costs attributable to heat, depending on the disability type. The estimated odds ratios with a 95% confidence interval [CI] generally exhibit a positive association between heat and ED admissions among people with disabilities. This association remained consistent when the model setting and references for odds ratio calculation were changed (Supplementary Table 5). The heat odds ratio estimate for the total people with disabilities was 1.10 (95% CI: 1.08–1.13), and the odds ratio estimate was the most pronounced for people with intellectual disability (odds ratio: 1.25 with 95% CI: 1.13–1.39). The estimated RORs for the total ED admissions were significantly higher than one across all disability types (i.e., odds ratio estimates of people with disabilities were higher than those of their control non-disability groups), except for people with blindness or vision loss disabilities. The differences in odds ratio estimates between people with and without disabilities were evident in people with intellectual and mental disabilities (ROR: 1.39 with 95% CI: 1.18–1.58 for intellectual disability and ROR: 2.27 with 95% CI: 2.05–2.51 for mental disability), and brain lesion disorder (ROR: 1.49 with 95% CI: 1.39–1.59) than other types of disabilities. The differences in odds ratios within the population with disabilities were summarized in Supplementary Fig. 1; people with mental disabilities, intellectual disabilities, or brain lesion disorders had significantly higher heat risk estimates for the total ED admissions compared to the total people with disabilities. Furthermore, we estimated the excess ED admission costs by type of disability: people with brain lesion disorder (US dollars (US$, 2023) 6.8 per person-year with 95% empirical confidence intervals (eCIs): US$ 4.8–8.7), and mental disability (US$ 4.0 per person-year with 95% eCIs: US$ 2.2–5.7) had higher point estimates of the excess cost estimates than other disability types. Due to the small sample size, the results were statistically unreliable for people with autistic disorder; therefore, we did not include these results in the figures but summarized them in Supplementary Table 6.

The panel (a) shows the risk estimates which were defined as the odds ratio with calculated odds at the 99th percentile compared to that at the local 75th percentile (99th percentile vs. 75th percentile) using a case-crossover design with a conditional logistic regression adjusted for national holidays and relative humidity. The panel (b) shows the relative odds ratio (ROR) which was calculated as the odds ratio of people with each disability type divided by the odds ratio of people without disabilities. The panel (c) shows the excess costs attributable to heat. Error bars show a 95% CI for estimates of risk and eCI for estimates of excess costs. N represents the number of cases from the population with disabilities, and cases of the population without disabilities were matched at a 1:1 ratio. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. CI confidence interval, eCI empirical confidence interval, USD United States Dollar.

Association by cause of admission

The heat odds ratios and RORs differed by the cause of admission (Fig. 2). Among the four causes of ED admissions, the odds ratio point estimates were generally higher in ED admissions for cardiovascular diseases than other types of ED admissions among people with disabilities, and the estimated RORs of cardiovascular ED admissions are significantly greater than 1 for all types of disabilities. Although estimated RORs for other ED causes showed heterogeneous patterns by disability type, individuals with mental disabilities showed significantly higher RORs compared to their control group in ED admissions for cardiovascular, genitourinary, and mental diseases/disorders. The three-dimensional exposure–lag–response associations exhibited different patterns by causes of ED admission (Supplementary Fig. 2). Further, people with brain lesion disorders had higher RORs than those of their matched control group in ED admissions for cardiovascular, genitourinary, and respiratory diseases. People with intellectual disabilities also exhibited significantly higher RORs in ED admissions for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. Furthermore, among disability groups (Supplementary Fig 3), people with brain lesions or physical disabilities had significantly higher heat risk estimates for cardiovascular ED admissions, and individuals with intellectual disabilities showed greater heat risk estimates for ED admissions with genitourinary diseases or mental disorders, compared to the total people with disabilities. Excess ED admission costs attributable to heat were pronounced in ED admission by cardiovascular diseases among individuals with brain lesion disorder (Supplementary Fig. 4).

The panel (a) shows the risk estimates which were defined as the odds ratio with calculated odds at the 99th percentile compared to that at the local 75th percentile (99th percentile vs. 75th percentile) with each disability type for each cause of admission using a case-crossover design with a conditional logistic regression. The panel (b) shows the relative odds ratio (ROR) which was calculated as the odds ratio of people with each disability type for each cause of admission divided by odds ratio of people without disabilities for each cause of admission. Error bars show a 95% CI for estimates of risk. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. CI Confidence interval.

Association by sociodemographic characteristics

Figure 3 depicts how heat odds ratios and RORs of ED admissions differed according to biological factors such as sex and age, and income status (socioeconomic factor). In the population with disabilities, the heat odds ratio estimates were significantly higher in people with low (p-value: 0.0093) and middle-income (p-value: 0.0153) compared to the odds ratio estimates of the total individuals with disabilities (Supplementary Table 7). Meanwhile, the significant heat risk differences between people with and without disabilities (RORs) by sex, age, and income (except for the high-income group) were observed in the total type of disabilities. Further, based on the point estimations of RORs, the effect modifications by these sociodemographic factors were generally more pronounced in individuals with brain lesion disorders or mental disabilities, compared to other types of disabilities. The excess ED admission costs by these sociodemographic characteristics are reported in Supplementary Fig 5.

The panel (a) shows the risk estimates which were defined as the odds ratio with calculated odds at the 99th percentile compared to that at the local 75th percentile (99th percentile vs. 75th percentile) using a case-crossover design with a conditional logistic regression. The panel (b) shows the relative odds ratio (ROR) which was calculated as the odds ratio of people with each disability type in each age, sex, and income group divided by the odds ratio of people without disabilities in each age, sex, and income group. Error bars show a 95% CI for estimates of risk. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. CI=confidence interval.

Association by population density

The estimated risks also differed according to the population density of residential areas (another social factor; Fig. 4). Based on ROR estimates, the heat risk difference between people with and without disabilities was generally more pronounced in areas with middle or low population density. The higher RORs in low-density areas were more pronounced in people with mental disabilities. This trend was similar when we used the population size as an urbanization indicator (Supplementary Table 8). The excess ED admission costs varied by population density (Supplementary Fig. 6).

The panel (a) shows the risk estimates which were defined as the odds ratio with calculated odds at the 99th percentile compared to that at the local 75th percentile (99th percentile vs. 75th percentile) using a case-crossover design with a conditional logistic regression. The panel (b) shows the relative odds ratio (ROR) which was calculated as the odds ratio of people with each disability type in each population density area divided by the odds ratio of people without disabilities in each population density area. Error bars show a 95% CI for estimates of risk. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. CI Confidence interval.

Discussion

In this nationwide study of people with disabilities, our findings revealed that people with disabilities have a significantly higher association between heat and total ED admissions (incorporating ED admissions for cardiovascular, genitourinary, and respiratory diseases, and mental disorders) than people without disabilities. Furthermore, the heat risk differences between people with and without disabilities were greater in ED admissions for cardiovascular diseases, and people with mental disabilities or brain lesion disorder. People with low or middle-income status have greater heat risk estimates compared to that of the total individuals with disabilities.

People with disabilities have a higher prevalence of chronic diseases and multimorbidity than people without disabilities17,18. Hypertension and hyperlipidemia, which show a high prevalence among individuals with disabilities, may further increase the risk of other cardiovascular diseases19. In addition, comorbid conditions may contribute to the use of various medications for their management20. In our cohort, comorbidities (dementia and chronic pulmonary diseases) and the presence of other disabilities among individuals with physical disability increased the risk estimate of ED admission related to heat (Supplementary Tables 9, 10). Moreover, some people with disabilities may depend on caregivers for daily functioning and activities18,21. As expressing needs can be challenging for some people with disabilities due to limited language capacity or difficulties in understanding their health condition18, heat-related manifestations and symptoms of distress and agitation may be overlooked by their caregivers22. Furthermore, people with disabilities encounter various barriers in education, work, social activities, access to information, and mobility8,9,12,13,15,23. These barriers can be associated with greater difficulty in preparing for, managing, and adapting to high temperatures in a timely manner. In short, higher levels of comorbid conditions, certain medications, difficulties in expressing health conditions, limited access to social infrastructure and medical services, and social deprivation among people with disabilities may collectively contribute to their increased risk estimates of ED admissions attributable to heat, compared to individuals without disabilities.

Our findings evidenced that ED admissions by mental disorders had high odds ratios among the four causes of admissions within the population with disabilities. People with mental health needs such as intellectual and mental disabilities generally showed greater risks of ED admission than those with other disability types based on the point estimates. Numerous previous studies that did not consider various types of disabilities found that individuals with comorbid mental disorders were more vulnerable to heat24,25. Heat can be a risk factor for the exacerbation of mental conditions26 and increase the risk of ED admissions, especially among people with limited cognitive function, or ED admissions by mental disorders16. Mental disorder comorbidities and mental health-related disabilities, including neurodevelopmental disorders, may reduce cognitive awareness, including weather conditions, and hence individuals may be less likely to perceive increased heat exposure or respond with adequate adaptation behaviors11,27. Additionally, antipsychotic and psychotropic medications have thermoregulatory side-effects28. The exacerbation of mental conditions and limited cognitive function may amplify the risk of ED admission among people with intellectual, and mental disabilities or ED admission due to mental disorders. The effects of these factors appear to be more pronounced in the population with disabilities compared to the population without disabilities.

Although the statistical evidence was weak, our results could indicate that the heat odds ratios generally increased as the population density decreased among people with disabilities. It implies that people with disabilities who are living in low or middle population density areas generally have higher risk estimates of ED admissions attributable to heat than people with disabilities who are living in high population density areas. The estimated RORs shows that people with disabilities who are living in middle population density areas generally have higher heat risk estimates than people without disabilities who are living in middle population density areas. Previous studies have reported conflicting results regarding the impact of heat exposure by population density or urbanicity levels29. Some studies have shown a higher risk of heat exposure in urban areas (which usually have a high population density)30,31; however, others have shown a higher risk in rural areas (typically with low population density)29,32. A time-series study in Korea showed the highest heat-related mortality risk in rural areas29, consistent with our findings. Many countries have implemented heat warning systems. In Korea, the government sends heatwave alerts and operates heat-cooling shelters33. However, these social infrastructures, including medical resources, tend to be used mainly in urban areas29,34, and accessing these infrastructures and perceiving alerts can be challenging for people with mobility difficulties or sensory impairment9. Deficient distribution of heat-related policies and social infrastructure may result in low accessibility. Moreover, limited accessibility to these services among people with disabilities owing to their health conditions can exacerbate the overall decline in accessibility. This may amplify the risk of ED admissions attributable to heat among people with disabilities, particularly those living in areas of a low or middle population density.

We found that the patterns of association with heat depending on the cause of admission and sociodemographic status differed according to the disability type. This supports the notion that people with disabilities are a heterogeneous group7. The age structures differed by disability type. The age at which individuals were initially registered as having a disability varied as well, depending on the type of disability (Supplementary Table 11). In addition, according to the National Disability Statistics, the most common comorbidities differed depending on the disability class and type: gastritis and hyperlipidemia for physical disability and vision or hearing loss, hypertension for brain lesion disorder, and various mental disorders and schizophrenia in people with intellectual, and mental disability, and autistic disorder35. Thus, the disability type, age, socioeconomic status, and underlying health conditions may interact complexly with the heat impact, underlying the importance of intersectional explanations in interpreting the heterogeneous patterns observed in some disability types.

The excess ED admission costs attributable to heat were generally higher among groups with high heat odds ratios compared to those with low heat odds ratios, such as persons older than or equal to 65 years, the low-income group, and those with brain lesion disorders and intellectual, and mental disabilities within the population with disabilities. However, in some cases, the excess ED admission costs were high, although the heat odds ratios were small. For example, ED admissions for cardiovascular diseases among some disability populations showed higher excess ED admission costs than other causes, even though the heat odds ratios were smaller than the other causes. These differences occurred because attributable medical costs were examined using the product term of the heat ORs and baseline medical costs for each visit. Thus, when estimating the heat risk and making plans to respond to situations, different approaches and prioritizations depending on health risks or economic burdens are required.

This study is notable for its large scale in using nationwide data to assess the association between heat and ED admission in Korea for people with a broad spectrum of physical and mental health-related disabilities, including neurodevelopmental disorders. By considering different types of disabilities and sociodemographic characteristics of beneficiaries and comparing risk estimates between people with and without disabilities, this study provides insights into varying susceptibility depending on the disability type, age, sex, population density of residential areas, income status, and cause of admission. Furthermore, these results can be used as evidence for the necessity of a differential heat wave early warning system for people with disabilities as they are potentially more vulnerable and invisible population compared to other populations. Second, this study theoretically covered the entire Korean population with one of seven types of disabilities, and the findings may reflect certain characteristics of the population with disabilities in Korea. Our results may be useful for broader international communities in establishing climate risk mitigation policies. In addition, as we quantified the absolute increase in medical costs attributable to heat in addition to odds ratio and RORs, it provided various results that policymakers may utilize when planning, prioritizing, and evaluating policies.

This study has some limitations. First, we defined cases based on claims data; therefore, we may have lost some cases if beneficiaries did not visit the emergency department for accessibility or financial issues. Thus, we could not account for the differences in accessibility or affordability, which could be potential effect modifiers. Second, although ED admissions can recur in the same person, we could not consider recurrent admissions by adding a random intercept for each beneficiary because of the large data size and computational burden. Third, even though we adopted a time-stratified case-crossover to control confounding variables that are invariant or do not change markedly in a month, unmeasured confounders that could substantially change within a month (e.g., daily activities, mood, high-risk drinking, etc.) could exist. Therefore, all estimates of this study have to be interpreted as “associations”, not “causations”. Fourth, our study did not consider the long-term impact of heat; however, it has been regarded as a growing public health concern in recent studies36,37, thus, further studies that evaluate the long-term impacts of hot temperatures are needed to provide valuable findings. Finally, although subgroup analyses have revealed varying patterns across different types of disabilities, understanding of the specific mechanisms or causes behind these variations is limited. Further studies using more detailed data are required to elucidate these mechanisms.

In conclusion, this study found that individuals with disabilities generally have a higher association between exposure to heat and ED admissions than individuals without disabilities, and the risk differences were heterogeneous by type of disability, cause of ED admissions, demographic characteristics, and residential population density. With the increasing number of people with disabilities and summer temperatures, the impact of heat on human health, especially for people with disabilities, may be strengthened in the future. People with disabilities are not included as high-risk individuals in the Environmental Health Master Plans based on the Environmental Health Act of Korea; this situation is similar to that in many other countries. Using the quantified risks from our results, practical action plans targeting individuals at high risk such as people with disabilities can be developed.

Methods

Data source

We collected the entire ED admission during the warmest four months (June to September) following the previous studies16,38 from the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS), a single universal insurer in Korea, and the National Health Insurance Database (NHID). The NHID comprises claims data generated using the beneficiaries’ medical bill expenses claimed by medical service providers. Theoretically, everyone living in Korea must be registered within the NHIS, and 99.1% of South Korean nationals are active beneficiaries of the NHIS, except for transient and long-term expatriates39. The NHID also contains sociodemographic characteristics such as age, sex, residential area, economic status (with the degree of insurance payment), healthcare resource use like hospital visits, diagnosis based on International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10 code), and related medical costs.

Study population

A national registration system for people with disabilities is officially operated by the Korean government based on the Act on Welfare of Persons with Disabilities40 and the registration covered 94.1% of persons with disabilities in 201740. The registration process requires a disability certificate prescribed by a medical doctor with relevant medical records and the submitted documents are reviewed by the National Pension Service to determine the provision of welfare benefits based on the type and severity of disabilities40.

This study included seven types of disabilities for which residence information was available: (1) physical disability, (2) brain lesion disorder, (3) blindness or vision loss, (4) deafness or hearing loss, (5) intellectual disability, (6) autistic disorder, and (7) mental disability (Supplementary Note 1). The national cohort consisted of over three million beneficiaries with disabilities. We selected a control group (i.e., people without disabilities) for each type of disability to increase the comparability. A combined matching (propensity score-based 1:1 matching with an exact matching) was performed. Specifically, we considered sex (exact matching), age, income group, a province-level residential place, and four comorbidity variables (myocardial infarction or congestive heart failure, renal disease, dementia, and chronic pulmonary diseases; propensity score matching). The 1:1 nearest neighbor matching method was used for the propensity score matching. More detailed information on the matching variables and similarity tests between case and matched control groups is displayed in the Supplementary material (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4).

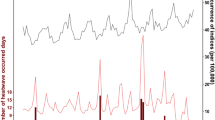

Meteorological variables

The satellite-based daily mean temperature (°C) and mean relative humidity (%) were collected using the Google Earth Engine (GEE) with the ERA5-Land dataset between June and September from 2006 to 202141. We used the daily mean temperature as the exposure index, which reflects overall temperature exposure. The daily mean temperature data of the ERA5-Land dataset showed a high accuracy compared to the temperatures measured at the monitoring stations (R2 > 0.95)38. These temperature data were extracted at a 9-km spatial grid and aggregated to district units (Si/Gun/Gu). We calculated the temperature percentiles of each district for 16 years using the collected temperature data and applied the percentile values of temperature as the exposure variables42.

Statistical modeling

We used a time-stratified case-crossover design to examine whether events were associated with a particular exposure6. As each case serves as its own control in the case-crossover design (i.e., self-matching), the design controls for time-invariant confounders over a short-term period (sex, diet, etc.) and adjusts for seasonality and long-term trends6. We defined a case day as the date of ED admission, and control days as the same year, month, and day of the week as the case day. The case day and matched three to four control days acted as the stratum, and we compared the exposure levels between the case and control days. We performed a conditional logistic regression to estimate the association between short-term exposure to hot temperatures and ED admission in people with and without disabilities.

We constructed the model Eq. (1) as follows to estimate the marginal risk of temperatures:

where Yit denotes the ED admission status of case number i on day t, cb the cross-basis function, and ns the natural cubic spline (NCS). We used a distributed lag non-linear model (DLNM) to address both the non-linear exposure–response functions and non-linear lag–response functions by defining the cross-basis function2. As in previous studies, we modeled the exposure–response curve using a natural cubic spline with four degrees of freedom (df)43. The lag–response curve was modeled using a NCS with two internal knots, and the maximum lag period was set to five days43. In addition, we added an interaction term between the cross-basis for temperatures and a binary indicator of disability (i.e., disabilityi = 1 for cases with disability and 0 for cases without disability) to compare the risk of ED admissions associated with heat between people with and without disabilities. We also adjusted for federal holidays using binary variables and present-day relative humidity using a NCS with three degrees of freedom.

We estimated the odds ratio of ED admissions associated with heat, which was calculated as the odds at the local 99th percentile compared with that at the local 75th percentile (99th percentile (28.8 °C) vs. 75th percentile (24.8 °C))16. To compare the risk between people with and without disabilities, we calculated the ROR by dividing the odds ratios of people with disabilities by the odds ratios of people without disabilities. To quantify the adverse health impacts of heat in another way, we calculated the annual increase in ED admission costs attributable to heat per 100,000 person-years. Using the estimated odds ratio, the excess ED admission costs were defined as α × (odds ratio - 1)/(odds ratio), where α was calculated using the daily medical costs of ED admission during the study period (June–September from 2006 to 2021) among the beneficiaries (of each study group), and odds ratio was the estimated odds ratio value43. The excess ED admission costs were determined for levels over the 75th percentile of temperature percentile, together with 95% eCIs, using 1000 Monte Carlo simulations2.

We conducted subgroup analyses based on sex (male and female), age (0–64 and 65+ years), population density (low, middle, and high population density areas), and income status (low-, middle-, and high-income groups) at ED admission. We used population density (persons/km2) as an urbanization indicator29. We segmented it based on the quantile values: Q1 (low) denotes values falling below the 33rd quantile, Q2 (middle) between the 33rd and 67th quantiles, and Q3 (high) exceeding the 67th quantile. For income status, we segmented the degree of insurance payment into three, defining the low-income group as the lowest 15% and the high-income groups as the highest 15%16. In addition, we classified ED admissions based on the cause of ED admission, resulting in four groups based on the principal diagnostic codes in the claims data from the NHID43: cardiovascular diseases (ICD-10: I00–I99), genitourinary diseases (N00–N99), mental disorders (F00–F99), and respiratory diseases (J00–J99). We performed the Wald test based on the independent assumption to examine the difference among estimates between subgroups.

Multiple sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of the results. First, we changed the maximum lag period from five to three days with one internal knot or seven days with two internal knots. Second, we estimated the odds ratio using other reference values to validate the associations. Additionally, we used population size (N) as an alternative urbanization indicator. We used SAS (Enterprise v7.1, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) for data pre-process and R (version 4.0.3; R Development Core Team) for statistical analyses with the packages DLNM, tsModel, spline, and survival.

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea (IRB No. E2302/004-002).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The satellite-derived ERA5-land temperature data are publicly available at the Google Earth Engine website: [https://earthengine.google.com/]. The claim data from the National Health Insurance Database are protected and available under restricted access for the requirements for data confidentiality and privacy. Therefore, the authors do not have permission to share claim data. Access can be obtained by a formal data application process and the National Health Insurance Service will process and approve the data request. To apply for the data, you are required to obtain IRB approval from an institution in South Korea, and this request procedure takes around a year. Once access is granted, you may use the data up to one year. Source data are provided with this paper. The source data consists of seven sheets. “Fig. 1” presents the number of cases from the population with disabilities, the estimated odds ratio, relative odds ratio, and excess medical costs attributable to heat, including their confidence intervals and empirical confidence intervals. “Fig. 2,” “Fig. 3,” and “Fig. 4” present the number of cases from the population with disabilities for each subgroup, and the estimated odds ratio and relative odds ratio, including their confidence intervals. “Supplementary Fig. 1” and “Supplementary Fig. 3” present the p-values from the Wald tests. “Supplementary Fig. 4,” “Supplementary Fig. 5,” and “Supplementary Fig. 6” present the number of cases from the population with disabilities for each subgroup, and the estimated excess medical costs attributable to heat, including their empirical confidence intervals. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

A sample of the analysis code is available from https://github.com/pjapja0823/NComm_DSB_Heat44.

References

Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. Global warming of 1.5 °C. IPCC Spec. Rep. impacts Glob. Warm. 1, 43–50 (2018).

Gasparrini, A. et al. Projections of temperature-related excess mortality under climate change scenarios. Lancet Planet. Health 1, e360–e367 (2017).

McIver, L. et al. Health impacts of climate change in Pacific Island countries: a regional assessment of vulnerabilities and adaptation priorities. Environ. Health Perspect. 124, 1707–1714 (2016).

Zhang, Y. et al. Socio-geographic disparity in cardiorespiratory mortality burden attributable to ambient temperature in the United States. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26, 694–705 (2019).

Wen, B. et al. Association between ambient temperature and hospitalization for renal diseases in Brazil during 2000–2015: a nationwide case-crossover study. Lancet Reg. Health-Am. 6, 100101 (2022).

Nori-Sarma, A. et al. Association between ambient heat and risk of emergency department visits for mental health among US adults, 2010 to 2019. JAMA psychiatry 79, 341–349 (2022).

WHO. World report on disability 2011. (World Health Organization, 2011).

Gamble, J. L. et al. in The Impacts of Climate Change on Human Health in the United States: A Scientific Assessment 247–286 (U.S. Global Change Research Program, 2016).

Izutsu, T. et al. in United Nations World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction and the Progress Thereafter.

Yeo, T. P. Heat stroke: a comprehensive review. AACN Adv. Crit. Care 15, 280–293 (2004).

Martin-Latry, K. et al. Psychotropic drugs use and risk of heat-related hospitalisation. Eur. Psychiatry 22, 335–338 (2007).

Houtenville, A., Shreya, P. & Rafal, M. Annual Report on People with Disabilities in America, 2021. Institute on Disability, University of New Hampshire (2021).

Engelman, A., Craig, L. & Iles, A. Global Disability Justice In Climate Disasters: Mobilizing People With Disabilities As Change Agents: Analysis describes disability justice in climate emergencies and disasters, mobilizing people with disabilities as change agents. Health Aff. 41, 1496–1504 (2022).

Kim, S., Byun, G. & Lee, J.-T. Association between non-optimal temperature and cardiovascular hospitalization and its temporal variation at the intersection of disability. Sci. Total Environ. 904, 166874 (2023).

Kang, Y., Baek, I. & Park, J. Assessing heatwave effects on disabled persons in South Korea. Sci. Rep. 14, 3459 (2024).

Park, J., Kim, A., Bell, M. L., Kim, H. & Lee, W. Heat and hospital admission via the emergency department for people with intellectual disability, autism, and mental disorders in South Korea: a nationwide, time-stratified, case-crossover study. Lancet Psychiatry 11, 359–367 (2024).

Horner-Johnson, W., Dobbertin, K., Lee, J. C. & Andresen, E. M. Disparities in chronic conditions and health status by type of disability. Disabil. health J. 6, 280–286 (2013).

Krahn, G. L., Hammond, L. & Turner, A. A cascade of disparities: health and health care access for people with intellectual disabilities. Ment. Retardation Developmental Disab. Res. Rev. 12, 70–82 (2006).

Steinberger, J. & Daniels, S. R. Obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk in children: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, and Obesity in the Young Committee (Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young) and the Diabetes Committee (Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism). Circulation 107, 1448–1453 (2003).

Mannucci, P. M., Nobili, A. & Investigators, R. Multimorbidity and polypharmacy in the elderly: lessons from REPOSI. Intern. Emerg. Med. 9, 723–734 (2014).

Perrin, J. M. Health services research for children with disabilities. Milbank Q 80, 303–324 (2002).

Tartarini, F., Cooper, P., Fleming, R. & Batterham, M. Indoor Air Temperature and Agitation of Nursing Home Residents With Dementia. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 32, 272–281 (2017).

Stein, P. J. & Stein, M. A. Climate change and the right to health of people with disabilities. Lancet Glob. Health 10, e24–e25 (2022).

Davido, A. et al. Risk factors for heat related death during the August 2003 heat wave in Paris, France, in patients evaluated at the emergency department of the Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou. Emerg. Med. J. 23, 515–518 (2006).

Schifano, P. et al. Susceptibility to heat wave-related mortality: a follow-up study of a cohort of elderly in Rome. Environ. Health 8, 1–14 (2009).

Hansen, A. et al. The effect of heat waves on mental health in a temperate Australian city. Environ. Health Perspect. 116, 1369–1375 (2008).

Millyard, A., Layden, J. D., Pyne, D. B., Edwards, A. M. & Bloxham, S. R. Impairments to Thermoregulation in the Elderly During Heat Exposure Events. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 6, 2333721420932432 (2020).

Stöllberger, C., Lutz, W. & Finsterer, J. Heat-related side-effects of neurological and non-neurological medication may increase heatwave fatalities. Eur. J. Neurol. 16, 879–882 (2009).

Lee, W. et al. Effects of urbanization on vulnerability to heat-related mortality in urban and rural areas in South Korea: a nationwide district-level time-series study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 51, 111–121 (2022).

Li, D. & Bou-Zeid, E. Synergistic interactions between urban heat islands and heat waves: The impact in cities is larger than the sum of its parts. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 52, 2051–2064 (2013).

Hajat, S., Kovats, R. S. & Lachowycz, K. Heat-related and cold-related deaths in England and Wales: who is at risk? Occup. Environ. Med. 64, 93–100 (2007).

Hu, K. et al. Evidence for urban–rural disparity in temperature–mortality relationships in Zhejiang Province, China. Environ. Health Perspect. 127, 037001 (2019).

Jang, Y. G. & Lee, S. K. A Case Study on the Heatwave Policy for Vulnerable Population due to Climate Change-Focused on the Elderly in Daegu City. 한국위기관리논집 15, 43–60 (2019).

Gamble, J. L. et al. Climate Change and Older Americans: State of the Science. Environ. Health Perspect. 121, 15–22 (2013).

Center, N. R. (2023).

Armstrong, B. et al. Longer-term impact of high and low temperature on mortality: an international study to clarify length of mortality displacement. Environ. Health Perspect. 125, 107009 (2017).

Rehill, N., Armstrong, B. & Wilkinson, P. Clarifying life lost due to cold and heat: a new approach using annual time series. BMJ open 5, e005640 (2015).

Park, J. et al. Association between heat and hospital admissions in people with disabilities in South Korea: a nationwide, case-crossover study. Lancet Planet. Health 8, e217–e224 (2024).

Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service & Service, N. H. I. 936 (Sun-Min, Kim, Do-Tae, Kang, 60, Hyeoksin-ro, Wonju-si, Gangwon-do, Korea; 32, Geongang-ro, Wonju-si, Gangwon-do, Korea, 2022).

Kim, K. Disability rating system reform in Korea: focusing on improving of the service delivery system for people with disabilities. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 45, 1–11 (2019).

Muñoz Sabater, J. ERA5-land monthly averaged data from 1981 to present, Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 55, 5679–5695 (2019).

Masselot, P. et al. Excess mortality attributed to heat and cold: a health impact assessment study in 854 cities in Europe. Lancet Planetary Health 7, e271–e281 (2023).

Sun, S. et al. Ambient heat and risks of emergency department visits among adults in the United States: time stratified case crossover study. BMJ. 375, e065653 (2021).

Park, J. NComm_DSB_Heat, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14970480 (2025).

Acknowledgements

WL was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2024-00343147 & RS-2024-00416848). HK was supported by Korea Environment Industry &Technology Institute (KEITI) through “Climate Change R&D Project for New Climate Regime.”, funded by Korea Ministry of Environment (MOE) (grant number: RS-2022-KE002235). JP was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2024-00412028). In addition, the study also used NHIS-NSC data (NHIS-2023-2-101) made by National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) in South Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.P. and W.L. conceptualized the study. W.L. and J.P. designed the methodology. J.P. analyzed and verified the data. W.L. and H.K. acquired study funding. W.L. and H.K. supervised the study. J.P. wrote the original draft. A.K., Z.A., K.E., H.K., and W.L. reviewed and edited the manuscript. H.K. and W.L. were responsible for the decision to submit the manuscript. J.P., A.K., Z.A., K.E., H.K., and W.L. had full access to the study results and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Meng Li, Ana Bonell, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, J., Kim, A., Al-Aly, Z. et al. Heat and hospitalization risks among people with disabilities in South Korea. Nat Commun 16, 4040 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59270-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59270-8