Abstract

Direct photocatalytic oxidation of methane to high-value-added oxygenated products remains a great challenge due to the unavoidable overoxidation of target products. Here, we report an efficient and highly selective TiO2 photocatalyst anchored with subnanometric MoOx clusters for photocatalytic methane oxidation to organic oxygenates by oxygen. A high organic oxygenates yield of 3.8 mmol/g with nearly 100% selectivity was achieved after 2 h of light irradiation, resulting in a 13.3% apparent quantum yield at 365 nm. Mechanistic studies reveal a photocatalytic cycle for methane oxidation on the MoOx anchored TiO2, which not only largely inhibits the formation of hydroxyl and superoxide radicals and the overoxidation of oxygenate products but also facilitates the activation of the first carbon-hydrogen bond of methane. This work would promote the rational design of efficient non-noble metal catalysts for direct conversion of methane to high-value-added oxygenates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Direct conversion of methane (CH4) to high-value-added oxygenates (such as CH3OOH, CH3OH, HCHO, HCOOH, and CH3COOH) with molecular oxygen (O2) is one of the most ideal approaches to realize the optimization and utilization of methane and reduce the dependence on crude oil1,2,3,4,5. However, due to the intrinsic inertness of CH4, high temperatures and pressures are normally required to activate C–H bonds, which not only greatly decrease selectivity of the organic products but also give rise to operational risks and environmental problems6,7. Photocatalysis is a potential way to drive CH4 oxidation by utilizing solar energy instead of thermal energy to overcome thermodynamic barriers, which is drawing keen attentions due to its safe, green and economic advantages8,9,10,11. Upon excitation by photons, a series of active oxygen-containing radicals (such as •OH and O2•−) formed during photocatalytic CH4 conversion with O2 can activate the C–H bond under mild conditions12,13,14. However, the highly active radicals are much easier to oxidize oxygenates than CH415,16,17, and thus it is a great challenge to simultaneously optimize the activity and selectivity for the photocatalytic reaction, unless expensive oxidants (such as H2O2 and N2O) instead of O2 are utilized18,19,20,21,22.

Choosing appropriate cocatalysts plays a key role in photocatalytic CH4 oxidation on semiconductor photocatalysts, as they not only achieve efficient separation of photogenerated charge carriers to promote methane activation, but also regulate surface catalytic reactions to minimize the overoxidation of desired products. Among numerous cocatalysts, owing to the surface plasmon resonance effect and the electron trapping effect, noble metals (Pt, Pd, Au, Ag etc.) generally exhibit the excellent performance for photocatalytic CH4 oxidation15,23,24,25. It has been found that dual metal cocatalysts involving noble metals and less-expensive metal species would integrate both electron acceptor and donor cocatalysts with the photocatalyst, which could boost the separation of photogenerated carriers and weaken the oxidative potentials of photocatalysts to properly suppress overoxidation16,26. For example, a promising result obtained by Tang and coworkers26 showed that ZnO with state-of-the-art dual Au–Cu cocatalysts achieved nearly 100% selectivity and high activity for 4 h with a 14.1% apparent quantum yield at 365 nm for CH4 conversion to oxygenates. Recently, highly efficient alternative cocatalysts (including transition metals and their derivative species) to noble metals have been widely studied27,28,29,30,31. However, their performance remains far from satisfactory due to the sluggish separation of photogenerated carriers. Most recently, Ye and coworkers28 reported that atomically dispersed Ni on nitrogen doped carbon/TiO2 composite (Ni−NC/TiO2) achieved a high yield of oxygenates of 198 μmol with a selectivity of 93%, despite of the low apparent quantum yield (1.9% at 365 nm) for oxygenates. It is worth noting that most of the reported photocatalytic CH4 oxidation reactions mainly follow the radical reaction mechanism, leading to unavoidable overoxidation of the products, and therefore a long-time (>360 min) accumulation of the oxygenate products cannot be achieved.

To address these problems and further improve the catalytic performance of non-noble metal-modified photocatalysts, rational and applicable designs of suitable cocatalyst are of great urgency. Highly dispersed cocatalysts of transition metal oxide, including single sites and clusters, can sufficiently expose active sites, and maximize metal oxide-support interaction to facilitate the separation of photogenerated carriers32,33,34,35. More importantly, a rich tunability of the chemical state of transition metals and oxygen coordination may enable non-radical catalytic mechanism proceed, modulating the activity and selectivity by creating fitting electronic structure and active sites.

Molybdenum oxide (MoOx), in particular, tends to exhibit unique physical and chemical properties due to the variable Mo valence range of +2 to +6 and the presence of a variety of Mo−O bonds (including Mo=O bonds, short Mo−O bonds, and long Mo−O bonds), whose atomic and electronic structures can be sensitively tuned by heteroatoms (Bi, Ce, Co, Fe, etc.) and oxide supports (Al2O3, TiO2, ZrO2, SiO2)36,37. As such, MoOx based materials have been utilized to selective thermocatalytic oxidation of hydrocarbons, such as ethane, isobutane and isobutene38,39. Most recently, Shen et al. dispersed MoOx monolayer with Mo4+, Mo5+, and Mo6+ species on TiO2, which exhibited high activity and selectivity in thermocatalytic oxidation of isobutene to produce methacrolein40. In addition, some MoOx and their derivatives (such as MoOx/SiO2 and MoOx/SBA-15) were used to improve the efficiency of selective CH4 oxidation41,42,43,44. The volatility of active Mo species in the water-containing thermocatalytic reactions (≥500 °C) usually hinders the development of Mo-containing materials from an academic to a commercial catalyst45,46,47. The bottleneck can be resolved by photocatalysis under ambient temperature.

Herein, we report that subnanometric MoOx clusters anchored on TiO2 can fully expose the active sites of Mo species for photocatalytic CH4 oxidation with O2. A high C1 oxygenates yield of 3.8 mmol/g with nearly 100% selectivity was achieved after 2 h of light irradiation, resulting in a 13.3% apparent quantum yield at 365 nm, which outperforms some recent reports (Table S1). A long-time (1800 min) accumulation of the products has been realized during reaction process with almost constant productivity and high selectivity (> 95%). Mechanistic studies reveal a photocatalytic cycle for CH4 oxidation on MoOx−TiO2 surface. The MoOx-cocatalysts not only trap photogenerated electrons to boost the carrier separation, but also largely inhibit the formation of •OH and O2•− radicals to jam the overoxidation of desired oxygenates. This work would promote the rational design of efficient and economical non-noble metal catalysts for direct conversion of methane (CH4) to high-value-added oxygenates.

Results

Synthesis and characterization of the MoOx−TiO2 catalyst

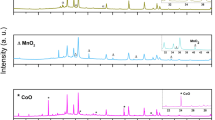

After the synthesis of anatase TiO2 nanosheet with predominantly exposed (001) facet, a series of MoOx−TiO2 photocatalysts with different Mo loading (0.05–0.7 wt.%) were prepared via a facile impregnation method. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns (Fig. 1a) show that all diffraction peaks correspond to pure anatase and no signal of Mo species is detectable on the MoOx−TiO2 samples. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image (Fig. 1b) shows that the 0.5%MoOx−TiO2 sample exhibits a typical nanosheet morphology with an average size of ca. 120 nm and a thickness of ca. 10 nm. The high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) (Fig. S1 in supporting information) shows clear lattice fringe and the lattice spacing parallel to the lateral facets is 0.356 nm, corresponding to the (101) facet of anatase TiO2. Although the Mo species is not observed by HRTEM on the surface of 0.5%MoOx−TiO2, aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning TEM (AC HAADF-STEM) images (Figs. 1c, d and S2) clearly exhibits subnanometric MoOx clusters of ca. 0.6 nm on 0.5%MoOx−TiO2. The energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) elemental mapping images (Fig. 1e) indicate that elemental Mo is uniformly dispersed throughout the entire surface of 0.5%MoOx−TiO2. Moreover, the MoOx structures on 0.1%MoOx−TiO2 and 0.7%MoOx−TiO2 have also been characterized by the AC HAADF-STEM experiments (Figs. S3 and S4). It can be found that the MoOx species mainly exist as single sites and small amount of subnanometric cluster on 0.1%MoOx−TiO2, while aggregated sub-nanometer MoOx clusters with slightly increased size (ca. 0.77 nm) are present on 0.7%MoOx−TiO2.

The surface compositions and chemical states of MoOx−TiO2 were investigated by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). As shown in the high-resolution Mo 3d XPS spectra (Fig. 2a), two peaks at 232.6 and 235.8 eV can be ascribed to Mo 3d5/2 and Mo 3d3/2 of Mo6+ species, respectively. As the Mo loading increases, more MoOx species are bond to TiO2 surface, and more MoOx clusters are formed, leading to the shift of Mo 3d, O 1s, and Ti 2p XPS peaks towards higher binding energy as shown in Figs. 2a and S5. X-ray absorption fine structure spectra (XAFS) were further acquired to investigate the coordination environment of Mo in MoOx−TiO2 using Na2MoO4, MoO3, MoO2, and Mo foil as references. The Mo K-edge X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra (Fig. 2b) show that the absorption edge position of MoOx−TiO2 is very similar to Na2MoO4, and the pre-edge transition at 20006.1 eV is due to Mo 1s to 4d transition with low symmetry of coordination atoms. Thus, the Mo species anchored to titanium dioxide should have tetrahedral [MoO4] characteristics similar to Na2MoO4.

a Mo 3d XPS spectra of MoOx−TiO2 with different Mo loading. b Mo K-edge XANES spectra of 0.5%MoOx−TiO2, Na2MoO4, MoO3, MoO2, and Mo foil. c FT Mo K-edge EXAFS spectra of 0.5%MoOx−TiO2, Na2MoO4, MoO3, and Mo foil. d EXAFS fitting curve of 0.5%MoOx−TiO2. The inset is the model MoOx structure on TiO2. The O, Ti, and Mo atoms are in red, grayish and cyan, respectively. e UV–Vis absorption spectra and (f) the corresponding plots of transformed Kubelka–Munk function versus photon energy of TiO2, 0.5%MoOx−TiO2 and MoO3. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The coordination structure of MoOx species is resolved by combining Fourier transformed (FT) Mo K-edge extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) analysis and atomistic modeling based on DFT calculations. Figure 2c compares the FT Mo K-edge EXAFS spectra for MoOx−TiO2, Na2MoO4, MoO3, and Mo foil. The MoOx−TiO2 photocatalyst exhibits first-shell scattering at 1.19 Å in R space (without phase correction), which is similar to the values, 1.13 and 1.10 Å, found for Na2MoO4 and MoO3, respectively. This is distinct from the case of Mo foil, in which the first-shell scattering locates at 2.38 Å. As such, we tentatively assign the primary scattering pair at 1.19 Å in the R-space spectrum of MoOx−TiO2 to two types of Mo−O bonding. To reveal the configuration of Mo species on TiO2, the curve fitting for EXAFS spectrum was performed (Fig. 2d and Table S2). The fitting results of the first-shell scattering (1–2.2 Å) show that one Mo−O bond length is 1.68 Å with an average coordination number of 2.5, and the other is 2.26 Å with an average coordination number of 1.0 on MoOx−TiO2. Meanwhile, the wavelet transformation analysis of MoOx−TiO2 catalyst and MoO3 has been conducted (Fig. S6), which is used to provide resolutions in both the R- and k-spaces and therefore has the potential to distinguish paths with similar coordination distances48. The peak centered at (k, R) = (5, 1.2) is associated with the Mo−O single scattering path, which is similar to that in MoO3. While the peaks centered at (k, R) = (8.5, 2.4) and (8.8, 3.1) probably correspond to the Mo−Ti and Mo−Mo scattering paths, respectively. The assignment is based on the fact that the scattering atoms are heavier with higher centering k values, and the peak at (k, R) = (8.8, 3.1) matches well with that of the Mo−Mo path in MoO3 centered at (k, R) = (10.0, 3.1) (Fig. S6b). Combined with the AC HAADF-STEM result, we deduce that the Mo species exist as subnanometric hexavalent Mo oxide (MoOx) clusters anchored on TiO2 surface as shown in Fig. 2d, insert. According to the UV–Vis absorption spectra (Fig. 2e), the light absorption of bare TiO2 occurs at wavelengths shorter than 400 nm (the ultraviolet region) while that of 0.5%MoOx−TiO2 extends to visible light region (400–800 nm). Then, the UV–Vis absorption data are converted into Tauc plots to determine the bandgap (Fig. 2f). Compared to the bare TiO2, the bandgap of 0.5%MoOx−TiO2 exhibits a slight reduction (0.06 eV), which can be attributed to the formation of Ti−O−Mo bonds on TiO2 anchored with subnanometric MoOx clusters. Similar to the MoO3, the visible light absorption of 0.5%MoOx−TiO2 should be mainly associated with the subnanometric MoOx clusters.

The photocatalytic performance of CH4 oxidation with O2

Photocatalytic CH4 oxidation reactions were performed on bare TiO2 and MoOx−TiO2 photocatalysts with variable Mo loading. As shown in Fig. 3a, the oxygenate products of CH4 photooxidation include CH3OOH, CH3OH, HCHO, HCOOH CO, and CO2. C2+ products and H2 could not be detected (Fig. S7). The produced CH3OOH, CH3OH, and HCOOH were detected by 1H NMR spectra (Fig. S8), while HCHO was quantified using the calibration curves established by the acetylacetone colorimetric method (Fig. S9). CO2 and CO as the overoxidized products, were determined by gas chromatography (Fig. S10). Xenon lamp was used as light source (Fig. S11). The bare TiO2 exhibits a relatively low liquid oxygenate yield of 1.58 mmol/g for the 2 h reaction (0.79 mmol/g/h) with an oxygenate products selectivity of 87.2%. The yield of liquid oxygenates increases slightly when the Mo loading is increased to 0.1% and increases significantly to maximum (1.90 mmol/g/h) when the Mo loading is increased to 0.5%, while it declines slightly with the further increase of Mo loading to 0.7%. According to the AC HAADF-STEM results, the MoOx species are fully transformed into subnanometric MoOx clusters with the increase of Mo loading to 0.5%, and aggregated sub-nanometer MoOx clusters with slightly increased size (ca. 0.77 nm) are present when the further increase of Mo loading to 0.7%. These experimental results indicate that the subnanometric MoOx clusters can enhance the activity of photocatalytic CH4 oxidation over MoOx−TiO2 more effectively than the single MoOx sites. Moreover, the larger size and aggregated MoOx clusters are slightly less favorable to the increase in the catalytic activity probably due to the reduced exposure of MoOx sites. Compared to single-site catalysts, subnanometric-cluster catalysts not only have higher tunability in chemical composition and atomic arrangements of active sites, but also provide multiple adsorption sites for multi-reactant catalytic systems49,50. Recently, Lu et al. prepared rGO catalysts anchored with Ru3O2 clusters, which were efficient and selective for the oxidative dehydrogenation reaction of 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (THQ). They found that Ru3O2 clusters promoted the adsorption of reactants and desorption of products, and the stronger interaction of Ru3O2 clusters with the rGO support facilitated the electron transfer compared with that of single atoms and nanoparticles51. Dong et al. also demonstrated that the unique reactive interfaces between subnanometric BaO clusters and TiO2 facilitated the activation and dissociation of nitrate, leading to the efficient and selective photocatalytic conversion of nitrate to ammonia52.

a Product yield and selectivity of liquid organic oxygenates for a series of MoOx−TiO2 with different Mo loading. b Product yield and selectivity of liquid organic oxygenates for 0.5%MoOx−TiO2 with variable H2O amount. Time course for product yield and selectivity of liquid organic oxygenates for (c) bare TiO2 and (d) 0.5%MoOx−TiO2. Reaction condition in (a–d): 10 mg catalyst, 100 mL water, 2 MPa CH4, 0.1 MPa O2, 25 °C, light source: 300 W Xe lamp, 13 mW/cm2 (UV light), 420 mW/cm2 (full spectrum). Three repeated experiments were performed under the same conditions, and the total yield (the sum of all products) was obtained for each of the three experiments. Error bars represent the standard deviations of the three total yield. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The photocatalytic performance of MoOx−TiO2 exhibits a volcanic trend with the increase of Mo loading, and the highest yield of liquid oxygenates reaches 3.80 mmol/g for the 2 h reaction (1.90 mmol/g/h) over 0.5%MoOx−TiO2. On the other hand, the product selectivity also exhibits a volcanic trend along with the increase of Mo loading, and the optimal selectivity of liquid oxygenates is nearly 100% over 0.5%MoOx−TiO2. According to the AC HAADF-STEM results, the MoOx species are transformed into subnanometric MoOx clusters with the increase of Mo loading to 0.5%, and the product selectivity also increases. With the further increase of the Mo loading, aggregated sub-nanometer MoOx clusters with slightly increased size are predominant, resulting in a slightly decrease of the product selectivity. Thus, the formation of subnanometric MoOx clusters should be also the key to improve the selectivity of liquid oxygenates. In addition, the catalyst shows high stability, and there is no obvious decrease in activity after 6-run cycling tests (12 h in total) (Fig. S12). Noteworthily, due to the difference of light sources in different studies, including light intensity and composition, it is difficult to precisely compare the catalyst performance by reaction rate. The apparent quantum efficiency (AQE) provides a reliable assessment of photocatalytic efficiency. The AQE for the liquid oxygenates over 0.5%MoOx−TiO2 is determined to be 13.3% (Table S1) under the irradiation of monochromatic light of 365 nm.

When the solubility of CH4 and O2 in water is increased by elevating the pressure, the selectivity of liquid oxygenates reaches the maximum at CH4 of 2 MPa and O2 of 0.1 MPa (Figs. S13 and S14). The excessively dissolved CH4 and O2 cause a decrease in selectivity of liquid oxygenates from nearly 100% to 98% due to the overoxidation of products. The effect of water on the photocatalytic CH4 oxidation over bare TiO2 and 0.5%MoOx−TiO2 is also investigated (Figs. 3b and S15). With the increase of H2O amount, both product yield and selectivity of liquid oxygenates are slightly boosted on bare TiO2 due to the production of hydroxyl (•OH) and superoxide (O2•−) radicals and the enhanced desorption of the liquid oxygenates, in consistent with the previous reports15,53,54. Unlike these radical reactions, with increasing H2O amount from 25 to 100 mL, the yield of liquid oxygenates decreases from 5.40 to 3.80 mmol/g for 2 h reaction, while their selectivity increases from 97% to nearly 100% in the aqueous photocatalytic CH4 oxidation over 0.5%MoOx−TiO2 (Fig. 3b), which may mainly occur on the MoOx active sites of the catalyst surface. The increase of H2O amount can reduce the concentration of the catalyst, and the probability of reactants to contact with the active sites on catalyst, leading to the decline in the product yield. Moreover, the increase of H2O amount can reduce the concentration of the oxygenate products, and inhibit the further oxidation of these oxygenates to CO2. Thus, the selectivity of the liquid oxygenates increases with the increase of H2O amount. We also performed the photocatalytic CH4 oxidation reaction on TiO2 with variable Mo loadings under the test condition: 25 mL water, 2 MPa CH4, 0.1 MPa O2 (Fig. S16). The product yield and selectivity of liquid organic oxygenates are optimal for the 0.5%MoOx−TiO2 sample.

Figure 3c shows time course for product yield and selectivity of liquid organic oxygenates on bare TiO2. The product yield slightly grows up after 360 min of irradiation, but the selectivity of liquid organic oxygenates decreases considerably from 90% to 77% along with irradiation time (up to 1800 min), which can be ascribed to the overoxidation of oxygenate products. With the increase of reaction time, more oxygenate products accumulate in solution, which boosts their further oxidation to CO2. Thus, as the reaction time increases, the selectivity of liquid oxygenates on bare TiO2 declines. In contrast, on 0.5%MoOx−TiO2, when the reaction time is gradually prolonged up to 1800 min, the product yield successively increases to 25.1 mmol/g with a high and stable selectivity of liquid organic oxygenates (95–100%) (Fig. 3d), indicating that the MoOx clusters can not only largely improve the activity of photocatalytic CH4 oxidation, but also hinder the overoxidation of these oxygenates to reach a high selectivity. Thus, a long-time accumulation of products can be achieved during the reaction process over the MoOx−TiO2 photocatalyst.

Reactive intermediates characterized by NMR and EPR

There is no product detectable without photocatalyst or light, or replacing CH4 with N2 (Table S3), indicating that all of the products originate from photocatalytic conversion of CH4. Isotope labeling NMR experiments using 13CH4 and 17O2 were performed to trace the source of carbon and oxygen atoms of these products. The 13C NMR spectrum (Fig. 4a, upper) shows four obvious peaks assigned to CH3OOH (65.0 ppm), CH3OH (49.0 ppm), HOCH2OH (82.3 ppm, derived from the hydration of HCHO in aqueous solution), and HCOOH (171.6 ppm), indicating that the formed oxygenates are derived from reactant 13CH4. Similar result is also found from the 1H NMR spectra (Fig. 4a, lower). For photocatalytic CH4 oxidation in a 12CH4 and 16O2 atmosphere, two 1H peaks at 3.26 and 8.42 ppm correspond to 12CH3OH and H12COOH, respectively. Using 13CH4 instead of 12CH4, both peaks split into two peaks due to 1H–13C J coupling (140 Hz) in the formed 13CH3OH and H13COOH. Furthermore, for the reaction in a 13CH4 and 17O2 atmosphere, the full width at half maximum of the signals for 13CH3OH and H13COOH obviously increases due to the weak 1H–17O J coupling (1.96 Hz), indicating that the oxygen atoms in CH3OH and HCOOH are originated from reactant 17O2. Additionally, when the N2 gas was used instead of O2 in the photocatalytic reaction (Table S3), only trace yield of products (HCHO, CO, and CO2) was generated, suggesting that the oxygen in HCHO is mainly derived from O2. When photocatalytic CH4 oxidation was carried out under direct heating conditions without a light source, only trace amounts of CO2 were produced (Table S3), indicating that the reaction was light-initiated rather than thermally driven.

(a, upper) 13C and (a, bottom) 1H NMR spectra for the product at a 2 h reaction time using 30 ml water, 80 kPa 13CH4/12CH4, 20 kPa O2/17O2, and 10 mg 0.5%MoOx−TiO2. b EPR spectra for detecting free radicals in the aqueous solution over bare TiO2 and 0.5%MoOx−TiO2. DMPO was added as the radical trapping agent. c In-situ EPR spectra of 0.5%MoOx−TiO2 in N2, CH4, O2 and (CH4 + O2) atmospheres before and during light irradiation. d In-situ 13C NMR spectra for bare TiO2 (bottom) and 0.5%MoOx−TiO2 (upper) in a (13CH4 + O2) atmosphere with increasing irradiation time. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) with DMPO as the radical trapping agent was used to detect free radicals in the aqueous photocatalytic CH4 oxidation with O2 over bare TiO2 and 0.5%MoOx−TiO2 (Fig. 4b). For bare TiO2, the typical and strong signals of •OH and O2•− radicals trapped by DMPO (DMPO−OH and DMPO−OOH) were observed under light irradiation, indicating the presence of •OH and O2•− radicals. Thus, the CH4 oxidation on the bare TiO2 should undergo a radical process, which can lead to unavoidable overoxidation55,56 and difficult accumulation of the liquid oxygenates for a long-time (Fig. 3c). For 0.5%MoOx−TiO2, both •OH and O2•− radicals decline remarkably, while its photocatalytic performance is much better than that of bare TiO2. It can be concluded that the CH4 oxidation mainly occurs on the metal active sites (MoOx) on the surface of the photocatalyst, rather than via a radical reaction initiated by the •OH and/or O2•− radicals. When the same amount of Mo was loaded on silica, there was no product generated (Table S3), suggesting that TiO2 plays a key role in photocatalytic CH4 oxidation, which should be the source of photogenerated carrier formation.

We used in-situ EPR spectroscopy to follow the formation and reaction of paramagnetic intermediates on the surface of bare TiO2 and 0.5%MoOx−TiO2. For 0.5%MoOx−TiO2, the EPR signal at g┴ = 1.929, g‖ = 1.874 appeared upon light irradiation (Fig. 4c), which is associated with tetra-coordinated Mo5+ sites (Mo4C5+)57 arising from trapped photogenerated electrons at the hexavalent MoOx sites. The in-situ Mo 3d XPS experiments were conducted to confirm the transfer of photogenerated carriers on surface MoOx species (Fig. S17a). In addition to the Mo4C5+ species, a small amount of Mo4+ species were formed on MoOx−TiO2 under irradiation, which could not be detected by EPR. When O2 was introduced into the 0.5%MoOx−TiO2 and the CH4/0.5%MoOx−TiO2 system, both of the EPR signals (Fig. 4c) decreased significantly upon light irradiation. Thus, it can be deduced that the reduced Mo sites (Mo4C5+ and Mo4C4+) transfer the trapped electrons to activate adsorbed O2, and are re-oxidized to hexavalent MoOx sites. Meanwhile, according to the in-situ O 1s XPS experiments (Fig. S17b), the photogenerated hole can oxidize surface oxygen to generate oxygen vacancies. However, unlike the presence of surface superoxide (Ti−O2•) on the bare TiO2 in the O2/(O2 + CH4) atmosphere during light irradiation (Fig. S18), no such active surface radicals are present on 0.5%MoOx−TiO2. According to the in-situ ATR-FTIR spectra (Fig. S19), the reduced Mo sites can react with adsorbed O2 to form surface peroxide sites Mo−OO and Mo−OOH, corresponding to the O−O stretching bands at 982 and 800 cm−1, respectively58,59. In the presence of CH4 and O2, the surface peroxide sites (especially Mo−OO) are significantly reduced upon light irradiation.

In-situ 13C MAS NMR experiments were used to follow the evolution of CH4 photooxidation by O2 on bare TiO2 and 0.5%MoOx−TiO2 (Fig. 4d). The formation rate of products (including gas and liquid) remains almost constant within 1 h (Fig. S20). For bare TiO2 in a (13CH4 + O2) atmosphere, four NMR signals evolve along with irradiation time. CH4 was oxidized by active oxygen-contained radicals (•OH and O2•−) to physically adsorbed CH3OH (52.0 ppm) and chemically adsorbed CH3OH (65.0 ppm), which can be subsequently oxidized to HOCH2OH (106.0 ppm) and adsorbed HCOOH (170.0 ppm). For 0.5%MoOx−TiO2 in a (13CH4 + O2) atmosphere, besides these oxygenate products, two types of surface intermediates are detected at 10–30 and 135.2 ppm, which can be assigned to physisorbed CH4 and chemisorbed HCHO on MoOx sites as confirmed by the following theoretical calculations. Compared with bare TiO2, the amount of physisorbed CH4 is greatly boosted on 0.5%MoOx−TiO2 surface upon the irradiation, which facilitates the photocatalytic oxidation of CH4. The unique reaction intermediates and reaction process suggest that the photocatalytic reaction mechanism is entirely different from the previous radical reaction mechanism60,61,62.

Photocatalytic mechanism and theoretical calculation of CH4 oxidation by O2

It can be found that HCHO is the main product of photocatalytic CH4 oxidation on MoOx−TiO2 (60% of the total oxygenate products, Fig. 3a). More interestingly, CH3OH tends to be further oxidized on bare TiO2, while it is hardly further oxidized on MoOx−TiO2 (Fig. S21). As such, the HCHO should be mainly produced by direct CH4 oxidation on MoOx−TiO2 rather than by the oxidation of product CH3OH by radicals. Furthermore, due to the low content of •OH and O2•− radicals formed on MoOx−TiO2 (Fig. 4b), the HCOOH can be effectively accumulated with little overoxidation to CO2 in the photocatalytic HCHO oxidation (Fig. S22). In contrast, owing to the relatively high content of •OH and O2•− radicals formed on bare TiO2, the generated HCOOH tends to be overoxidized to CO2. These results explain the difference in HCOOH formation between TiO2 and MoOx−TiO2 (Fig. 3c, d).

On the basis of the aforementioned experimental results, the photogenerated electrons are trapped by hexavalent MoOx sites to form Mo4C5+ and Mo4C4+ sites in the initial step of CH4 activation on MoOx−TiO2, instead of trapping by surface OH/H2O and O2 to generate •OH and O2•− radicals, which has been detected by in-situ EPR and Mo 3d XPS techniques (Figs. 4c and S17a). On the other hand, as shown in in-situ O 1s XPS spectra (Fig. S17b), the photogenerated holes can oxidize surface oxygens to form oxygen vacancies. Subsequently, the reduced Mo sites (Mo4C5+ and Mo4C4+) react with adsorbed O2 to generate surface peroxide sites, including Mo−OO and Mo−OOH, and the former can react with CH4 as revealed by in-situ ATR-FTIR spectra (Figure S19), suggesting that these peroxide sites are the reactive sites.

To understand the enhanced reactivity for selective photocatalytic CH4 oxidation to high-value-added oxygenate products, we have performed DFT calculation to simulate the reaction pathways on the proposed Mo−OO active site (Figs. 5 and S23). The reaction energy for the formation of Mo−OO (intermediate A) through interaction of Mo−O center and O2 was 1.76 eV on MoOx−TiO2, which is much lower than that (2.72 eV) for the formation of the peroxide intermediate (Ti−OO) on the bare TiO2. According to our theoretical calculations, the Mo−OO active sites can dissociate into the original structure (Mo−O) and O2 with an exothermic energy of −1.76 eV, indicating that the dissociation of Mo−OO site is thermodynamically favorable. This should be the reason that the peroxide species (including Mo−OO and Mo−OOH) formed upon irradiation decline obviously after the irradiation as shown in the in-situ ATR-FTIR spectra (Fig. S19). Thus, the formation of the Mo−OO active sites could be maintained by the photon energy available from light irradiation. The adsorption of CH4 at the Mo−OO site (intermediate B) releases an energy of -0.08 eV, accounting for the increase in CH4 physisorption upon irradiation (Fig. 4d). The activation of the first C−H bond of CH4 produces chemisorbed CH3OH (CH3O−Mo2, intermediate C), which is the rate-determining step of the catalytic cycle with an endothermic energy of 0.77 eV. According to the experimental results, CH4 activation on bare TiO2 can proceed via a radical mechanism. Our theoretical calculations indicate that the energy required for the first C−H bond activation decreases from 1.65 eV on bare TiO2 (Fig. S24) to 0.77 eV on MoOx−TiO2 (intermediate B → C, Fig. 5), highlighting the effective promotion of CH4 oxidation by MoOx−TiO2. The hydrolysis of CH3O−Mo2 would lead to the formation of product CH3OH. According to the previous reports25, the bare TiO2 with predominantly exposed (001) facets can inhibit the formation of •CH3 and •OH radicals. In addition to the radical reactions in solution, the C−H activation of CH4 also occurs partly on surface peroxide active sites (Ti−OO) of the bare TiO2. The MoOx loading on the TiO2 further reduces the formation of the radicals (Fig. 4b), so that the C−H activation of CH4 occurs mainly on the surface peroxide active sites (Mo−OO) of MoOx−TiO2. Therefore, the similar type of active sites and surface photocatalytic mechanism lead to the less change in product distribution before and after MoOx loading on TiO2 as shown in Fig. 3a.

The calculated reaction energy profile of photocatalytic CH4 oxidation on the subnanometric MoOx cluster. (Bottom) The corresponding structural models (structure A−G) in the figures. The H, C, O, Ti, and Mo atoms of MoOx−TiO2 are in white, dark gray, red, grayish, and cyan, respectively, while the O atoms from O2 are in purple. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. The atomic coordinates of corresponding structural models data are provided as Supplementary Data 1.

In the following step, CH3O−Mo2 is transformed to chemisorbed HCHO (CH2O−Mo2), and one H2O molecule (intermediate D) is generated by Mo−OOH abstracting one hydrogen atom from CH3O−Mo2 with an activation energy −1.54 eV. Therefore, the formation of chemisorbed HCHO through the second C−H bond activation is a thermodynamically favorable process. Two photocatalytic cycles of CH4 conversion on MoOx−TiO2 are proposed (Fig. 6). In the H2O-assisted mechanism of CH4 oxidation, the medium H2O molecule could facilitate desorption of H2O molecule and interact with the C atom of chemsorbed HCHO (H2O···CH2O, intermediate E1) with an exothermic reaction of −2.12 eV. Then the formed H2O···CH2O could be converted into chemsorbed dihydroxymethane (HOCH2OH−Mo, intermediate F1) through a H transfer step with an endothermic energy of 0.80 eV. After that, the attack of O2 on the Mo−O site results in the formation of terminal Mo−OO site, companying with the cleavage of HOCH2OH−Mo bond with an exothermic reaction of −0.94 eV, indicating that the generation of Mo−OO site and physisorbed CH2(OH)2 (intermediate G1) is thermodynamically favorable. Finally, the CH2(OH)2 is released with a low endothermic energy of 0.15 eV, suggesting that the formed CH2(OH)2 can be readily separated from the MoOx−TiO2 surface. The CH2(OH)2 has been detected by 13C NMR spectra (Fig. 4a), which is a derivative from the hydration of HCHO. The formation of CH2(OH)2 would prohibit the further oxidation of HCHO, in agreement with our experimental results. As a long-time accumulation of HCHO proceeds in the reaction, the amount of HCHO adsorbed on the active site increases, leading to a tendency for HCHO to be further oxidized to HCOOH (Fig. 3d).

In the anhydrous mechanism of CH4 oxidation, the direct desorption of H2O molecule with an endothermic energy of 0.45 eV results in the formation of intermediate E2, and then one O2 molecule adsorbs on its Mo−O site to form intermediate F2 with an adsorption energy of −0.32 eV. The adsorbed O2 molecule also facilitates the conversion from chemsorbed HCHO to physisorbed HCHO (intermediate G2) with an exothermic reaction of −1.92 eV. The desorption energy of HCHO is as low as 0.16 eV. As shown in Fig. 5, although the anhydrous mechanism of CH4 oxidation is thermodynamically feasible, the H2O-assisted reaction mechanism is more energetically favorable.

To elucidate the effect of different structure of MoOx species on catalytic activity, in-situ EPR experiments were also conducted on 0.1%MoOx−TiO2 and 3.0%MoOx−TiO2 (Fig. S25). It has been found that the MoOx species mainly exist as single sites on 0.1%MoOx−TiO2 (Fig. S3). Similar to the case of 0.5%MoOx−TiO2, the reduced Mo sites (Mo4C5+) were also formed on the 0.1%MoOx−TiO2 under illumination as shown in Fig. S25a. Subsequently, the reduced Mo sites can react with adsorbed O2 to generate surface active peroxide sites (Mo−OO) that can activate CH4. As such, the single MoOx sites should also exhibit excellent photocatalytic activity of CH4 oxidation. However, the content of the active Mo sites exposed on the single MoOx sites of 0.1%MoOx−TiO2 is much lower than that exposed on the subnanometric MoOx clusters of 0.5%MoOx−TiO2. This should be the reason that properties of part of the bare TiO2 surface are preserved, while a small amount of surface superoxide species (Ti−O2•) are formed on the 0.1%MoOx−TiO2. We have performed DFT calculations to predict the activation of the first C−H bond of CH4 on TiO2 loaded with single MoOx site (Fig. S26), which is the rate-determining step of the photocatalytic CH4 oxidation. It can be found that the first C−H bond activation in CH4 exhibits thermodynamic favorability with a calculated reaction energy −0.80 eV, which is much lower than that (0.77 eV) on TiO2 loaded with subnanometric MoOx cluster. While the formation of oxygen vacancy (Mo−Ov) requires a high energy of 4.35 eV on TiO2 loaded with single MoOx site, which is the key to generate the Mo−OO active sites, much higher than that of 3.30 eV on TiO2 loaded with subnanometric MoOx cluster (which is similar to the band gap energy of anatase TiO2). Therefore, the photocatalytic activity of CH4 oxidation on 0.5%MoOx−TiO2 is much higher than that on 0.1%MoOx−TiO2 (Fig. 3a). According to the XRD experiment of 3.0%MoOx−TiO2 (Fig. S27), the MoOx species loaded on TiO2 should be MoO3 nanoparticles. As shown in the in-situ EPR spectra (Fig. S25b), reduced Mo sites (hexa-coordinated Mo5+ sites, Mo6C5+)63 were formed on the 3.0%MoOx−TiO2 under illumination. Unlike 0.1%MoOx−TiO2 and 0.5% MoOx−TiO2, under O2 and (O2 + CH4) atmospheres, the signal intensity of the Mo6C5+ site remains almost unchanged on 3.0%MoOx−TiO2, indicating that the formed Mo6C5+ sites cannot transfer the photogenerated electron and activate CH4 effectively. Therefore, the activity of photocatalytic CH4 oxidation on 3.0%MoOx−TiO2 (0.91 mmol/g/h) is much lower than that on 0.5%MoOx−TiO2 (1.90 mmol/g/h).

Discussion

In summary, we report a highly efficient and selective photocatalytic oxidation process of CH4 into high-value-added oxygenates by molecular O2 on Mo oxide anchored TiO2 catalysts (MoOx−TiO2). The AC HAADF-STEM and X-ray absorption spectra show that the MoOx species with tetrahedral [MoO4] characteristics are present as subnanometric clusters of hexavalent MoOx sites, uniformly dispersed throughout TiO2. Based on in-situ EPR, XPS, and NMR results, a full photocatalytic cycle for CH4 oxidation by MoOx−TiO2 is proposed, which is completely different from the conventional radical reaction mechanism. The initial step in the activation of CH4 on MoOx−TiO2 involves the capture of photogenerated electron-hole pairs by the hexavalent MoOx sites to form Mo4C5+ and Mo4C4+ sites, followed by reduction of adsorbed O2 to generate a surface peroxides site (Mo−OO), which largely inhibit the formation of •OH and O2•− radicals and the overoxidation of oxygenate products. Combined with the DFT calculations, it can be found that the Mo−OO site is the reactive site which can promote the physisorption of CH4 and the activation of the first C−H bond of CH4. As a result, a high C1 oxygenates yield of 3.8 mmol/g with nearly 100% selectivity was achieved on the MoOx−TiO2 after 2 h of irradiation, resulting in a 13.3% apparent quantum yield at 365 nm. Furthermore, a long-time (1800 min) accumulation of oxygenate products has been realized during reaction process with almost constant productivity and high selectivity (> 95%). The results presented herein would be helpful for the rational design of efficient non-noble metal photocatalysts for direct conversion of CH4 to high-value-added oxygenates.

Methods

Materials

The following chemicals are used in the experiment, including Tetra-n-butyl titanate (Ti(OBu)4, Macklin, 98%), Hexaammonium heptamolybdate tetrahydrate ((NH4)6Mo7O24•4H2O, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., ≥ 99.0%), Anhydrous ethanol (CH3CH2OH, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., ≥ 99.7%), Sodium hydroxide (NaOH, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., ≥ 96.0%), Hydrofluoric acid (HF, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., ≥ 40%), 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO, Dojindo Laboratories, ≥ 99%), Deuterium oxide (D2O, Energy Chemical, 99.9%). The water in all the experiments is de-ionized (DI) water in resistivity of 18.2 MΩ·cm.

Catalyst preparation

TiO2 nanosheets with dominant (001) facet were synthesized by hydrothermal method. Briefly, 1.0 ml of hydrofluoric acid (HF) was added to 25.0 ml of Ti(OBu)4 in a Teflon-line autoclave and then kept at 473 K for 24 h (Caution: HF is corrosive and a contact poison, and it must be handled with care!). After the autoclave was cooled to room temperature, the resulting product was separated by centrifugation and washed three times with anhydrous ethanol and NaOH solution (0.1 M), respectively. The catalyst was then stirred in the NaOH solution for 24 h and washed with deionized water until the supernatant was neutral. Finally, it was dried at 80 °C for 8 h. Catalyst yields are around 50%.

The MoOx-loaded TiO2 catalyst was prepared by simple impregnation method. Dissolve 0.5 g ammonium molybdate in 10.0 ml water to form ammonium molybdate solution. The Mo loading was achieved by mixing a certain amount of ammonium molybdate solution (0.56 ml) and water with TiO2 nanosheets (0.2 g) and stirring until the liquid is completely evaporated. The mixture was calcined at 673 K for 4 h in an air atmosphere. Catalyst yields are around 85%.

Catalyst characterization

XRD measurements of the prepared samples were conducted on a Panalytic X’ Pert3 diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54184 Å) operating at 40 kV and 40 mA. SEM was measured on a S4800 apparatus with an acceleration voltage of 3 kV. HRTEM images were acquired on Tecnai G2 F30 S-TWIN instrument at 300 kV. AC HAADF-STEM images and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping were measured on JEM ARM 200 F apparatus with an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) were collected on a Thermo Scientific Escalab 250Xi instrument using Al Kα (1486.6 eV) irradiation with the C 1 s characteristic peak of 284.8 eV as the reference. X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy spectra were acquired at the Mo K-edge on beamline 1W1B at the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility, which operates at 2.5 GeV with a current of 250 mA. The UV–Vis absorption spectra were obtained using a Cary 4000 UV–Vis spectrometer with BaSO4 as a reference. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) experiments were conducted on Nicolet iS50 spectrometer with a homemade spectral cell for attenuated total reflectance (ATR) FTIR experiments.

EPR experiments were performed using a JEOL JES-FA200 spectrometer to detect photogenerated reactive oxygen species64. Hydroxyl radicals (·OH) and superoxide radicals (\({{{{\rm{o}}}}}_{2}^{\_}\)) were captured via the spin-trapping technique with 5, 5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO). All these EPR experiments were conducted with 0.1 mT of the modulation amplitude and 3 mW of the microwave power at room temperature. The microwave frequency was 9.1 GHz.

Solid-state 13C CP/MAS NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker Advance III 400 spectrometer (9.4 T) with resonance frequencies of 399.33 MHz (1H) and 100.42 MHz (13C). A 4 mm MAS probe at a spinning rate of 12 kHz was utilized. For 1H −13C cross-polarization, Hartmann-Hahn matching conditions were optimized using hexamethylbenzene (HMB), with a contact time of 6 ms and a recycle delay of 1.5 s.

Photocatalytic measurements

Photocatalytic CH4 oxidation reactions were conducted in a 230 mL batch photoreactor equipped with a quartz window on the top. In a typica procedure, 10 mg of catalyst was uniformly dispersed in 100 mL deionized water via ultrasonication for 5 min. The photoreactor was then sealed and purged using O2 (purity, 99.999%) for 15 min to exhaust air. Subsequently, the reactor was pressurized with 0.1 MPa O2 and 2.0 MPa CH4 (purity, 99.999%). The mixture was continuously stirred at 1000 rpm in a water bath under illumination. After the reaction, the reactor was cooled in an ice bath to below 10 °C. Gaseous products were collected in gas bags and quantified by gas chromatography equipped with a methanizer and flame ionization detector. Liquid-phase products were filtered and analyzed via ¹H NMR spectroscopy. Formaldehyde was quantified by the colorimetric method25. The selectivity of products were calculated according to the following equations:

Isotopic tracer experiments

13C-labeled CH4 and/or 17O-labeled O2 were used to trace the fate of carbon atoms from methane and oxygen atoms from oxygen. Typically, 10 mg catalyst was dispersed in 30 ml of water and transferred to a glass unit for sealing. The catalyst solution was degassed on a vacuum system and labeled gas was added for the reaction. A similar approach was adopted to do 13C-labeled CH3OH photocatalytic conversion experiment. Bruker Avance-600 liquid NMR spectrometer was employed to analyze the liquid products obtained from the isotopic tracing experiments. The 1H NMR spectra were acquired using a water suppression pulse sequence.

Calculational method

Spin-polarized DFT calculations with Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functional were performed by applying the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) code65,66. The plane-wave basis set in conjunction with the projected augmented wave method was utilized to describe the valence electrons and the valence-core interactions.

The kinetic energy cut-off of the plane wave basis set and energy convergence threshold for each iteration was set to 400 eV and 10−5 eV, respectively. The geometries were considered to have converged when the forces acting on each atom was less than 0.05 eV/Å. The Brillouin zone-sampling was restricted to the gamma point. The van der Waals (vdW) interactions were incorporated by using Grimme’s DFT−D3 method as implemented in VASP. In this study, Mo4O12 and Mo3O11−Mo−OO clusters were constructed on the (001) facet of anatase TiO2 (Fig. S23). Based on the structure of anatase TiO2, we simulated the (001)−2 × 2 surface using 6 atomic layers with a 15 Å of vacuum between periodic slabs. The bottom three atomic layers were held fixed in their bulk positions while the remaining atoms were allowed to relax.

Data availability

All the data that support the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Agarwal, N. et al. Aqueous Au-Pd colloids catalyze selective CH4 oxidation to CH3OH with O2 under mild conditions. Science 358, 223–227 (2017).

Shan, J., Li, M., Allard, L. F., Lee, S. & Flytzani-Stephanopoulos, M. Mild oxidation of methane to methanol or acetic acid on supported isolated rhodium catalysts. Nature 551, 605–608 (2017).

Jin, Z. et al. Hydrophobic zeolite modification for in situ peroxide formation in methane oxidation to methanol. Science 367, 193–197 (2020).

Qi, G. et al. Au-ZSM-5 catalyses the selective oxidation of CH4 to CH3OH and CH3COOH using O2. Nat. Catal. 5, 45–54 (2022).

Gesser, H. D., Hunter, N. R. & Prakash, C. B. The direct conversion of methane to methanol by controlled oxidation. Chem. Rev. 85, 235–244 (2002).

Horn, R. & Schlögl, R. Methane activation by heterogeneous catalysis. Catal. Lett. 145, 23–39 (2014).

Olivos-Suarez, A. I. et al. Strategies for the direct catalytic valorization of methane using heterogeneous catalysis: challenges and opportunities. ACS Catal. 6, 2965–2981 (2016).

Yuliati, L. & Yoshida, H. Photocatalytic conversion of methane. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 1592–1602 (2008).

Song, H., Meng, X., Wang, Z.-j, Liu, H. & Ye, J. Solar-energy-mediated methane conversion. Joule 3, 1606–1636 (2019).

Li, Q., Ouyang, Y., Li, H., Wang, L. & Zeng, J. Photocatalytic conversion of methane: recent advancements and prospects. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202108069 (2022).

Chen, F. et al. Defective ZnO nanoplates supported AuPd nanoparticles for efficient photocatalytic methane oxidation to oxygenates. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2303642 (2024).

Nosaka, Y. & Nosaka, A. Y. Generation and detection of reactive oxygen species in photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 117, 11302–11336 (2017).

Wu, X., Zhang, H., Xie, S. & Wang, Y. Photocatalytic conversion of methane: catalytically active sites and species. Chem. Catal. 3, 100437 (2023).

Liu, C. Y. et al. Illustrating the fate of methyl radical in photocatalytic methane oxidation over Ag-ZnO by in situ synchrotron radiation photoionization mass spectrometry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202304352 (2023).

Song, H. et al. Direct and selective photocatalytic oxidation of CH4 to oxygenates with O2 on cocatalysts/ZnO at room temperature in water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 20507–20515 (2019).

Song, H. et al. Selective photo-oxidation of methane to methanol with oxygen over dual-cocatalyst-modified titanium dioxide. ACS Catal. 10, 14318–14326 (2020).

Jiang, Y. et al. Enabling specific photocatalytic methane oxidation by controlling free radical type. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 2698–2707 (2023).

Ravi, M., Ranocchiari, M. & van Bokhoven, J. A. The direct catalytic oxidation of methane to methanol-a critical assessment. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 16464–16483 (2017).

Xie, J. et al. Highly selective oxidation of methane to methanol at ambient conditions by titanium dioxide-supported iron species. Nat. Catal. 1, 889–896 (2018).

Sun, X. et al. Molecular oxygen enhances H2O2 utilization for the photocatalytic conversion of methane to liquid-phase oxygenates. Nat. Commun. 13, 6677 (2022).

Zhao, G., Adesina, A., Kennedy, E. & Stockenhuber, M. Formation of surface oxygen species and the conversion of methane to value-added products with N2O as oxidant over Fe-ferrierite catalysts. ACS Catal. 10, 1406–1416 (2019).

Wu, X. et al. Atomic-scale Pd on 2D titania sheets for selective oxidation of methane to methanol. ACS Catal. 11, 14038–14046 (2021).

Linic, S., Christopher, P. & Ingram, D. B. Plasmonic-metal nanostructures for efficient conversion of solar to chemical energy. Nat. Mater. 10, 911–921 (2011).

Jiang, W. et al. Pd-modified ZnO-Au enabling alkoxy intermediates formation and dehydrogenation for photocatalytic conversion of methane to ethylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 269–278 (2021).

Feng, N. et al. Efficient and selective photocatalytic CH4 conversion to CH3OH with O2 by controlling overoxidation on TiO2. Nat. Commun. 12, 4652 (2021).

Luo, L. et al. Binary Au-Cu reaction sites decorated ZnO for selective methane oxidation to C1 oxygenates with nearly 100% selectivity at room temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 740–750 (2022).

Ding, J. et al. Asymmetrically coordinated cobalt single atom on carbon nitride for highly selective photocatalytic oxidation of CH4 to CH3OH. Chem. 9, 1017–1035 (2023).

Song, H. et al. Atomically dispersed nickel anchored on a nitrogen-doped carbon/TiO2 composite for efficient and selective photocatalytic CH4 oxidation to oxygenates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202215057 (2023).

Luo, L. et al. Nearly 100% selective and visible-light-driven methane conversion to formaldehyde via. single-atom Cu and Wδ+. Nat. Commun. 14, 2690 (2023).

Xie, P. et al. Oxo dicopper anchored on carbon nitride for selective oxidation of methane. Nat. Commun. 13, 1375 (2022).

An, B. et al. Direct photo-oxidation of methane to methanol over a mono-iron hydroxyl site. Nat. Mater. 21, 932–938 (2022).

Liu, L. et al. In situ loading transition metal oxide clusters on TiO2 nanosheets as co-catalysts for exceptional high photoactivity. ACS Catal. 3, 2052–2061 (2013).

Rhatigan, S., Sokalu, E., Nolan, M. & Colón, G. Surface modification of rutile TiO2 with alkaline-earth oxide nanoclusters for enhanced oxygen evolution. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 3, 6017–6033 (2020).

Nolan, M., Iwaszuk, A., Lucid, A. K., Carey, J. J. & Fronzi, M. Design of novel visible light active photocatalyst materials: surface modified TiO2. Adv. Mater. 28, 5425–5446 (2016).

Zhang, H. et al. Ultrasmall MoOx clusters as a novel cocatalyst for photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Adv. Mater. 31, 1804883 (2018).

Li, Q. et al. Insight into the selective oxidation of isobutene to methacrolein over Ce-accelerated Mo-Bi-Fe-Co-K-O catalyst. Mol. Catal. 527, 112401 (2022).

Zhang, B., Ford, M. E., Ream, E. & Wachs, I. E. Olefin metathesis over supported MoOx catalysts: influence of the oxide support. Catal. Sci. Technol. 13, 217–225 (2023).

Nguyen, T. D., Zheng, W., Celik, F. E. & Tsilomelekis, G. CO2-assisted ethane oxidative dehydrogenation over MoOx catalysts supported on reducible CeO2–TiO2. Catal. Sci. Technol. 11, 5791–5801 (2021).

Guan, J. et al. Oxidation of isobutane and isobutene to methacrolein over hydrothermally synthesized Mo–V–Te–O mixed oxide catalysts. Catal. Commun. 10, 528–532 (2009).

You, H., Ta, N., Li, Y. & Shen, W. MoOx monolayers over TiO2 for the selective oxidation of isobutene. Appl. Catal. A 664, 119342 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. H2-reduced phosphomolybdate promotes room-temperature aerobic oxidation of methane to methanol. Nat. Catal. 6, 895–905 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. Sulfite-enhanced aerobic methane oxidation to methanol over reduced phosphomolybdate. ACS Catal. 14, 4352–4361 (2024).

Lou, Y. et al. Selective oxidation of methane to formaldehyde by oxygen over SBA-15-supported molybdenum oxides. Appl. Catal. A 350, 118–125 (2008).

Ohler, N. & Bell, A. T. Study of the elementary processes involved in the selective oxidation of methane over MoOx/SiO2. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 2700–2709 (2006).

Millner, T. & Neugebauer, J. Volatility of the oxides of tungsten and molybdenum in the presence of water vapour. Nature 163, 601–602 (1949).

Volta, J.-C., Forissier, M., Theobald, F. & Pham, T. P. Dependence of selectivity on surface structure of MoO3 catalysts. Faraday Discuss. Chem. Soc. 72, 225–233 (1981).

Hansson, K. et al. Oxidation behaviour of a MoSi2-based composite in different atmospheres in the low temperature range (400–550 °C). J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 24, 3559–3573 (2004).

Tang, B. et al. A Janus dual-atom catalyst for electrocatalytic oxygen reduction and evolution. Nat. Synth. 3, 878–890 (2024).

Sun, G., Alexandrova, A. N. & Sautet, P. Structural rearrangements of subnanometer Cu oxide clusters govern catalytic oxidation. ACS Catal. 10, 5309–5317 (2020).

Li, X. et al. Advances in heterogeneous single-cluster catalysis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 7, 754–767 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Atomically precise single metal oxide cluster catalyst with oxygen-controlled activity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2200933 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Subnanometric alkaline-earth oxide clusters for sustainable nitrate to ammonia photosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 13, 1098 (2022).

Luo, L. et al. Synergy of Pd atoms and oxygen vacancies on In2O3 for methane conversion under visible light. Nat. Commun. 13, 2930 (2022).

Zhou, H. et al. Boosting reactive oxygen species formation over Pd and VOδ co-modified TiO2 for methane oxidation into valuable oxygenates. Small 20, 2311355 (2024).

Jiang, Y. et al. Elevating photooxidation of methane to formaldehyde via TiO2 crystal phase engineering. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 15977–15987 (2022).

Gong, Z., Luo, L., Wang, C. & Tang, J. Photocatalytic methane conversion to C1 oxygenates over palladium and oxygen vacancies co-decorated TiO2. Sol. RRL 6, 2200355 (2022).

Latef, A. ESR evidence of tetracoordinated Mo4c5+ species formed on reduced Mo/SiO2 catalysts prepared by impregnation. J. Catal. 119, 368–375 (1989).

Martínez Q, H., Valezi, D. F., Di Mauro, E., Páez-Mozo, E. A. & Martínez O, F. Characterization of peroxo-Mo and superoxo-Mo intermediate adducts in photo-oxygen atom transfer with O2. Catal. Today 394-396, 50–61 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Continuous flow system for highly efficient and durable photocatalytic oxidative coupling of methane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 2465–2473 (2024).

Du, H. et al. Photocatalytic O2 oxidation of CH4 to CH3OH on AuFe-ZnO bifunctional catalyst. Appl. Catal. B 324, 122291 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Constructing hollow porous Pd/H-TiO2 photocatalyst for highly selective photocatalytic oxidation of methane to methanol with O2. Appl. Catal. B 320, 121961 (2023).

Fan, Y. et al. Selective photocatalytic oxidation of methane by quantum-sized bismuth vanadate. Nat. Sustain. 4, 509–515 (2021).

Louis, C. & Che, M. EPR investigation of the coordination sphere of Mo5+ ions on thermally reduced silica-supported molybdenum catalysts prepared by the grafting method. J. Phys. Chem. 91, 2875–2883 (1987).

Yang, L., Feng, N. & Deng, F. Aluminum-dped TiO2 with dminant {001} facets: microstructure and property evolution and photocatalytic activity. J. Phys. Chem. C. 126, 5555–5563 (2022).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22127801, 22372177) received by N.F. and F.D., respectively, National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFA1509100) received by J.X., and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB0540000) received by J.X., N.F., and F.D.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.F. and F.D. conceived the project. N.F. designed the studies. P.W. synthesized the photocatalysts. N.F., P.W. performed NMR experiments. P.W., N.F., M.W., J.X., D.M., and J.Y. analyzed all the experimental data. Y.C. performed theoretical calculations. N.F., P.W., Y.C., J.Y., and F.D., wrote the manuscript. All authors interpreted the data and contributed to preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, P., Chu, Y., Wang, M. et al. Subnanometric MoOx clusters limit overoxidation during photocatalytic CH4 conversion to oxygenates over TiO2. Nat Commun 16, 4207 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59465-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59465-z

This article is cited by

-

Orchestrated multi-physics field-engineering toward valorized C2+ chemicals from CO2/CH4

Science China Materials (2026)