Abstract

Circadian clocks temporally orchestrate the behavioural and physiological rhythms. The core molecules establishing the circadian clock are clear; however, the critical signalling pathways that cause or favour the homeostasis are poorly understood. Here, we report that anti-Müllerian hormone (Amh)-mediated signalling plays an important role in sustaining circadian homeostasis in zebrafish. Notably, amh knockout dampens molecular clock oscillations and disrupts both behavioural and hormonal circadian rhythms, which are recapitulated in bmpr2a null mutants. Somatotropes and gonadotropes are identified as Amh-targeted pituitary cell populations. Single-cell transcriptome analysis further reveals a lineage-specific regulation of pituitary clock by Amh. Moreover, Amh-induced effect on clock gene expression can be abolished by blocking Smad1/5/9 phosphorylation and bmpr2a knockout. Mechanistically, Amh binds to its receptors, Bmpr2a/Bmpr1bb, which in turn activate Smad1/5/9 by phosphorylation and promote circadian gene expression. Our findings reveal a key hormone signalling pathway for circadian homeostasis in zebrafish with implications for rhythmic organ functions and circadian health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prominent daily physiological and behavioural rhythms are driven by self-sustained biological oscillators called circadian clocks1,2, which have an internally driven 24 h day–night rhythm and are controlled by a transcriptional autoregulatory feedback loop involving multiple clock genes3,4. The endocrine and neural signals serve as the endogenous entrainment cues for the circadian oscillators5,6,7. Rhythmic secreted factors and neuronal activity from the brain act on the pituitary endocrine centre to coordinate 24 h systemic homoeostasis8. In its function coupling the hypothalamus with peripheral target tissues, the pituitary gland generates multiple rhythmic hormones that carry time-of-day signals from the clock. Thus, the chronic disruption of circadian oscillations in the endocrine master gland of the body may have cascading effects on physiology and behaviour9,10. Identifying the molecular circuitry that modulates the intricate pituitary clock in a cell type-specific manner will provide important insight into the precise regulation of circadian output mechanisms and long-term circadian homoeostasis throughout complex systems and anatomical regions.

Organism-wide homoeostasis requires the proper timing and output of a network of clocks. The balance between circadian timing and the endocrine system is vulnerable to the effects of modern lifestyle factors such as shift work or a high-fat diet11,12,13. The disruption of biological rhythms due to mutations in clock genes or abnormal environmental stimuli contributes to endocrine diseases in the female reproductive system, such as polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) and premature ovarian insufficiency (POI)14,15,16,17,18,19. Preclinical studies suggest that abnormal circulating levels of AMH (anti-Müllerian hormone) may potentially be a contributing factor to the central pathophysiology of multiple reproductive diseases20 and has been applied as a biomarker for the clinical assessment of ovarian reserves and the diagnosis of female reproductive diseases, such as PCOS, POI and granulosa cell tumours of ovary (GCT)21,22,23,24. Interestingly, serum shock has been found to induce circadian gene expression and mimic light-induced immediate-early gene expression in vitro25, suggesting that blood-borne signalling factors might be able to stimulate the signal transduction pathways that regulate the molecular clock. Thus, we considered the possibility that AMH, the regulation of circadian clocks, and endocrine diseases are interlinked.

The self-sustaining nature of the clock allows individual cells to function as cell-autonomous oscillators. Moreover, at the tissue and systemic levels, single-cell oscillators must synchronize with each other to maintain coherent tissue rhythms26,27. The pituitary gland is a highly heterogeneous organ28,29 that comprises specialized cell populations that produce various types of hormones with different daily and/or seasonal rhythmic patterns13,30. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of intrinsic circadian clocks within distinct cell populations are poorly understood. A major challenge in understanding the regulation of the endocrine pathways controlling clock outputs is the realization of precise molecular genetic analyses of a single endocrine cell population in the context of the complex pituitary gland. In this study, we show that Amh signalling is essential for the maintenance of robust circadian oscillations of molecular clocks and hormonal and behavioural rhythms. By combining fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)31,32 and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) of the adult pituitary33, we identify and verify cell type-specific regulation of the pituitary molecular clock mediated by Amh signalling mainly in somatotropes and gonadotropes. Moreover, we reveal that Amh-Bmpr2a-Smad1/5/9 signalling acts through multiple conserved clock-controlled elements to activate clock gene transcription in vivo. Therefore, our results define an essential signalling mechanism by which Amh-Bmpr2a serves as the central gatekeeper of clock output endocrine signals and circadian homoeostasis, opening new avenues for mechanistic research on circadian tissue physiology and endocrine pathologies associated with circadian disruption.

Results

Amh is required for the maintenance of the circadian clock in zebrafish

Circadian behaviours can be affected by environmental or genetic manipulation that disrupt the circadian clock34. Initially, we investigated the potential role of Amh in circadian homoeostasis by continuously monitoring the locomotor activity of wild-type (WT) and amh-mutated adult zebrafish (amh−/−) under the 14 h:10 h light/dark (LD) cycles. As expected, WT zebrafish exhibited a robust diurnal rhythm of locomotor activity, with most activity occurring during the light-phase and sleep-like behaviour observed after lights-off (Fig. 1A). This observation is consistent with previous reports35,36,37. Interestingly, in amh−/− mutants, locomotor activity consistently remained reduced during multiple ZT0–14 periods and increased during multiple ZT14–24 periods, resulting in a relatively decreased amplitude of the locomotor activity rhythm (Fig. 1A). Importantly, the total locomotor activity was significantly decreased in amh−/− mutants under LD condition (Fig. 1B). Moreover, a less pronounced difference in average activity between the light- and dark-phase was observed in amh−/− mutants compared to WT (Fig. 1C). Additionally, the moving distance and activity of amh−/− mutants were markedly reduced during the light-phase but remained significantly increased during the dark-phase (Fig. 1D, E). We also re-evaluated behaviour in WT and amh−/− mutants under the dark/dark (DD) condition, obtaining similar results (Fig. 1F–I). The distance moved during the subjective night exhibited an increasing trend in amh−/− mutants, though this difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 1J left). Our detailed analyses revealed that amh−/− mutants remained more active than WT controls for the majority of the time during the subjective night under DD condition (Fig. 1J right), which is similar to the result under LD condition (Fig. 1E right). These results further confirmed the phenotype that rhythm strength was decreased in the locomotor activity of amh−/− mutants. Taken together, these results indicate a disruption of rhythmic locomotor activity in amh−/− mutants, suggesting a requirement of Amh for the maintenance of a normal circadian behavioural rhythm in zebrafish.

The locomotor activities were monitored and analysed in female WT control and amh−/− mutants under LD (A–E) and DD (F–J) conditions. The total locomotor activities in 72 h (B, G), the quantification of average activities (C, H) and the moving distance and activity during the light-phase (D) dark-phase (E) subjective day (I) or subjective night (J) were shown. In the waveforms of locomotor activities, each point was calculated from the 5 min binned data across 3 days. For violin plots, dots and triangle correspond to individual zebrafish and the black and grey horizontal lines display the median as well as 25th and 75th percentiles. The box-and-whisker plots were presented as interquartile ranges with the median indicated by a line and whiskers extending from the minimum to the maximum values. For B–E n = 12 (WT) and n = 8 (amh−/−), (G–J) n = 8 (WT) and n = 24 (amh−/−). Statistical analysis was performed using two-sided unpaired t-test. K Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of core clock genes in pituitaries harvested at the seven indicated time points under DD condition from WT and amh−/− females. Target gene expression levels are shown relative to the beta-actin 2 reference gene actb2. The expression of WT CT2 was used for normalization. Data are presented as mean values ± SD, n = 3, two-sided unpaired t-test. ZT represents zeitgeber time, where ZT 0 corresponds to lights on; CT represents circadian time. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We next investigate the effect of amh mutation on molecular clocks. Considering that the pituitary gland, a crucial component of the physiological and behavioural regulatory system34,38,39,40, has been reported as a targeted tissue for Amh signalling41,42, we examined expression patterns of core circadian clock genes in the pituitary in response to amh knockout. Under DD condition, the expression oscillations of core circadian clock genes are synchronized with the subjective day/night periods in WT fish (Fig. 1K), which are consistent with previous reports43,44,45,46,47,48,49. In contrast to WT, it appeared a clearly dampened amplitude of clock gene expression rhythms in the pituitary gland of amh−/− zebrafish (Fig. 1K). Specifically, per1b, per3, clocka and rev-erbβ2 expressions are significantly down-regulated at multiple time points within a 24 h cycle (Fig. 1K). Furthermore, we extended our investigation into the impact of amh mutation on the core clock gene expression in other peripheral tissues. Compared with the WT, a visibly dampened amplitude of clock gene expression rhythm was also observed in the kidney, liver and heart of amh−/− zebrafish, showing a significant downregulation of rev-erbβ2 and clocka at multiple time points, particularly during peak expression (Fig. S1). In summary, these results demonstrated that Amh plays an essential role in the regulation of circadian clock.

Amh protein distribution in specific pituitary cell populations and its role in endocrine circadian homoeostasis

Given the strong effect of amh mutation on pituitary clock (Fig. 1K), we then focused on pituitary to understand the underlying molecular mechanism. We first determined the expression of the Amh protein in the pituitary of adult female zebrafish by immunofluorescence staining with a specific antiserum against Amh and found a wide distribution of Amh-immunoreactive cells in the adenohypophysis of WT zebrafish, including the proximal pars distalis (PPD) and the rostral pars distalis (RPD) (Fig. 2A a–c), consistent with the specific expression of Amh in the PPD of pituitary, where gonadotropes, somatotropes and thyrotropes are located (Fig. 2A d–f). In contrast, the Amh immunofluorescence signal was undetectable in amh−/− zebrafish (Fig. 2A g–i).

A Representative images: pituitary sections of adult WT and amh−/− female zebrafish immunolabelled with antiserum against Amh, in triplicate. B Schematic illustration of the isolation of Amh-immunolabelled pituitary cells from adult WT female zebrafish by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). C Representative scatterplots showing the staining of pituitary cells with anti-Amh and its isotype control. D Relative mRNA expression of endocrine cell marker genes in isolated Amh-positive pituitary cells. The expression of lhb was used for normalization. Data are presented as mean values ± SD and the individual data points are depicted (n = 3). E Representative images: double staining of WT pituitary sections by immunofluorescence staining of Amh (in green) and fluorescence in situ hybridization of gh1 (in red), a marker of somatotropes, in triplicate. PN pars nervosa, PI pars intermedia, PPD proximal pars distalis, RPD rostral pars distalis, DAPI 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Scale bars, 50 μm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further identify the cell lineages of Amh protein distribution, we next isolated Amh-positive pituitary cells by FACS after immunofluorescent staining with an anti-Amh antibody (Fig. 2B). Compared with the isotype control (0.051%), approximately 8.54% of the pituitary cells were Amh positive and were sorted (Fig. 2C). Although all the classical endocrine cell marker genes of the PPD and RPD areas of the pituitary were expressed in Amh-positive cells, the transcript levels of gh1 (somatotropes), lhb and fshb (gonadotropes) were obviously higher than those of other marker genes, including tshba (thyrotropes), pomca (corticotropes and melanotropes) and prl (lactotropes), indicating that somatotropes may be the primary site of Amh protein expression (Fig. 2D). We then costained the Amh protein by immunofluorescence after the evaluation of hormone marker gene transcripts via RNA fluorescent in situ hybridization (RNA-FISH) in pituitary sections to further verify the major Amh-positive cell lineages in vivo. The results showed that most Amh-immunoreactive cells were positive for gh1 mRNA in the PPD of the pituitary (Fig. 2E), whereas only a few Amh-positive cells expressed tshba mRNA (arrowheads in Fig. S2A). These histological results are highly consistent with our FACS results obtained with an anti-Amh antibody.

Since daily endocrine oscillations are orchestrated by the circadian clock, we further investigated the effect of amh mutation on the endocrine system. We examined the expression oscillations of hormone-coding genes expressed by Amh-positive cell lineages in the pituitary. Disrupted expression rhythms were visible among these hormone genes, including gh1, lhb, fshb and tshba, in amh-deficient pituitaries compared with the WT control (Fig. S2B). Thus, Amh is required for the maintenance of endocrine circadian homoeostasis.

Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals lineage-specific regulation of the pituitary circadian clock by Amh

The pituitary gland drives multiple conserved physiological processes in vertebrates by orchestrating hormone synthesis and release by specific cell lineages with a 24-h rhythm. To investigate the role of Amh within distinct pituitary cell populations, we performed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) of adult pituitaries from WT and amh−/− females. Barcoded cDNA libraries were prepared from dissociated pituitary live cells by using the 10X Genomics Chromium platform, followed by Illumina next-generation sequencing (Fig. 3A). We obtained over 5000 cells from WT and amh−/− mutants. The sequencing depth was over 84,000 reads for each cell. Finally, an average of >1000 genes were detected in each individual cell (Fig. S3A, B). After filtering for quality, we also applied the DoubletFinder tool to detect the potential doublets50, revealing an efficient removal of doublets (Fig. S3C).

A Schematic overview of the process of cell isolation and single-cell RNA-seq analysis of the zebrafish pituitary using the 10X Genomics platform (30 pituitaries in each group, WT and amh−/−). B UMAP visualization shows the unsupervised clustering of the aggregated results of two scRNA-seq experiments, revealing 10 major clusters of pituitary cells present in zebrafish. Each dot represents one cell, and colours represent cell clusters as indicated. C UMAP visualization of cluster marker genes. UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection. D Bar graph showing the percentages of each cell cluster in the pituitaries of WT and amh−/− zebrafish. E Gene ontology enrichment for the downregulated genes from the major affected pituitary cell populations of amh−/− zebrafish. The top 8 terms for biological process (BP) were shown. Hypergeometric test and Benjamini-Hochberg method used for multiple comparisons correction. F Volcano plot showing differential circadian clock gene expression between amh−/− and WT zebrafish in the major affected pituitary cell lineages. G Dot plot showing the expression changes in circadian clock genes across the pituitary cell clusters from WT and amh−/− female zebrafish. For F, G two-sided unpaired Wilcoxon test and adjustments were made for multiple comparisons. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We employed Seurat to identify cell clusters and Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) for visualization51. A total of ten cell clusters were identified according to the known marker genes33, including six classical pituitary endocrine cell populations (gonadotropes, corticotropes, melanotropes, somatotropes, lactotropes and thyrotropes), one fish-specific endocrine population (somatolactotropes), and three non-hormonal cell populations: a small potential progenitor cluster (isl1+ group) and two clusters with characteristics of pituicytes and immune cells (Figs. 3B, C and S3D). The relative proportion of each cluster weighed by the percentage of total cells in both genotypes showed that the ratios of gonadotropes and somatotropes were obviously reduced from 30.11% to 23.41% and 20.67% to 15.00%, respectively, in amh−/− mutants compared with WT zebrafish. The ratio of thyrotropes was clearly increased from 6.11% to 18.42% in amh−/− mutants compared to WT. However, the ratios of the other cell clusters showed no obvious change (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, the observed changes in cellular composition were validated by RNA-FISH detection of corresponding pituitary endocrine cell marker gene mRNA (Fig. S4). Results showed that gh1-labelled somatotropes and fshb-labelled gonadotropes were markedly reduced, while tshba-labelled thyrotropes were significantly increased in the amh−/− pituitary compared with WT controls (Fig. S4). These histological findings are highly consistent with the trends observed in our scRNA-seq data.

We then compared the transcriptome data of the three differential cell populations in amh−/− mutants. The differential expression analysis of gonadotropes, somatotropes and thyrotropes identified 193 genes (34 upregulated genes and 159 downregulated genes), 273 genes (12 upregulated genes and 261 downregulated genes) and 568 genes (29 upregulated genes and 539 downregulated genes), respectively, in amh−/− mutants, revealing a profound change in gene expression profiles (Supplementary Data 1). Gene Ontology (GO) analysis revealed that the downregulated genes were mainly associated with circadian rhythm regulation and the response to temperature stimulus in both gonadotropes and somatotropes, while they were enriched in the response to temperature stimulus, protein folding and circadian rhythm in thyrotropes (Fig. 3E). Among gonadotropes, somatotropes and thyrotropes, the upregulated genes identified in amh−/− mutants were significantly related to the JAK-STAT cascade, which has been proven to be a circadian rhythm regulatory pathway and is negatively regulated by clock genes52 (Fig. S3E). We also found that the core circadian clock genes were visibly downregulated in gonadotropes, somatotropes and thyrotropes (Fig. 3F). Thus, the obvious upregulation of JAK-STAT pathway genes might result from the overall dampening of core clock gene expression in these cell populations of amh−/− mutants. Moreover, the global differential expression analysis of clock genes revealed that many clock genes were obviously downregulated mainly in the gonadotropes, somatotropes, thyrotropes and corticotropes of amh−/− mutants compared to the WT control (Fig. 3G). Overall, comprehensive scRNA-seq analysis revealed that Amh plays vital roles in pituitary cell population development and lineage-specific regulation of the circadian clock, especially in Amh-positive pituitary cell populations.

Amh functions in the pituitary through the Bmpr2a/Bmpr1bb signalling pathway

In mammals, AMH binds to its specific type-II receptor AMHR2, which heterodimerizes with one of several type-I receptors, such as Acvr1 (Alk2), Bmpr1a (Alk3) or Bmpr1b (Alk6), to regulate target gene expression53,54,55. However, the amhr2 gene is not found in zebrafish and some vertebrate species with available genomes belonging to the classes Cypriniformes and Chondrichthyes, even though these species produce the corresponding Amh ligand56. Phylogenetic analysis of the Amhr2 and Bmpr2 amino acid sequences in fish species revealed a common origin of Bmpr2 and Amhr2, and Bmpr2a showed the closest relationship with Amhr2 among the type II receptors (Fig. S5A), suggesting that Bmpr2a might be recruited as an Amh receptor in fish species that lose amhr2 during evolution. In addition, genomic organization and gene synteny comparisons of bmpr2a and bmpr2b showed more conserved synteny within the genomic region of bmpr2a than that of bpmr2b in fish species, especially Danio rerio and Carassius auratus (Fig. S5B). This suggests that bmpr2a functions are more conserved than those of bmpr2b in fish species.

Among these candidate receptors, the transcript level of bmpr2a was obviously higher than those of bmpr2b, alk6b and alk2, while no alk3a/b and alk6a expression was detected in Amh-positive pituitary cells sorted by FACS with an anti-Amh antibody (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, pituitary scRNA-seq analysis revealed that bmpr2a was mainly expressed in Amh-positive cell lineages, including gonadotropes, somatotropes and thyrotropes, while bmpr2b expression was visibly lower than that of bmpr2a in gonadotropes and somatotropes (Fig. 4B). A coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiment was performed to determine the interaction between Amh and Bmpr2a. The Amh-HA and Bmpr2a-Flag plasmids were cotransfected into 293T cells, and the GFP-HA vector was used as a control. Although GFP-HA (asterisk) was expressed at a markedly higher amount than Amh-HA (double asterisks), only Amh-HA was able to pull down Bmpr2a-Flag using anti-HA Dynabeads (arrow, Fig. 4C). In addition, Bmpr1b (Alk6) is the only type I receptor that interacts with AMHR2 in a ligand-dependent manner54,57, and the phenotype of bmpr1bb (alk6b) mutant zebrafish mimics the amh mutant phenotype in which homozygotes display impaired gonadal development58,59. Since bmpr1ba (alk6a) was not expressed in Amh-positive pituitary cells, we further investigated whether Amh interacts with Bmpr1bb through co-IP experiments. Only Amh-HA was able to pull down Bmpr1bb-Flag using anti-HA Dynabeads (arrow), even though GFP-HA (asterisk) was expressed at a notably higher level than Amh-HA (double asterisk) (Fig. 4D). Moreover, histological double labelling by FISH further confirmed that bmpr2a mRNA was expressed in the Amh-positive cell lineages in vivo, such as the lh-expressing gonadotropes in the WT pituitary (arrowheads in Fig. 4E), which is consistent with our FACS and scRNA-seq results. Taken together, these results indicate that the action of Amh on the pituitary gland might depend on its receptors, Bmpr2a and Bmpr1bb.

A Relative mRNA expression of candidate receptors of Amh in the isolated Amh-positive pituitary cells determined by quantitative real-time PCR analyses. The expression of bmpr2a was used for normalization. Data are plotted as mean ± SEM, n = 3. B The expression level distributions of candidate type II receptor genes are shown as violin plots across WT pituitary cell clusters. The p-value was calculated using the two-sided unpaired Wilcoxon test. C, D Amh-HA or GFP-HA was cotransfected with Bmpr2a-Flag and Bmpr1bb-Flag into 293T cells. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated using anti-HA Dynabeads and analysed by Western blotting. E Representative images: double labelling of bmpr2a (red) and lhb (green) in WT pituitary sections by fluorescent in situ hybridization, in triplicate. Scale bars, 25 μm. F The Y2H assays showing the interaction between Amh and Bmpr2a. G Amh interacted with Bmpr2a in BiFC assays, in triplicate. Scale bars, 10 μm. H The 3D structures of Amh (a) and Bmpr2a (b), (c) the molecular docking analysis between Amh and Bmpr2a. I-J The SPR analysis for binding kinetics between Bmpr2a domain and Amh C-terminal domain (I) or the full-length Amh (J). SPR response profile for Bmpr2a at different concentrations with sensor-immobilized Amh C-terminal domain or the full-length Amh. ka, association rate constant; kd, dissociation rate constant; KD, dissociation constant. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We further confirmed the interaction between Amh and its type-II receptor Bmpr2a. First, the yeast-two-hybrid (Y2H) assays demonstrated a direct interaction between Amh and Bmpr2a (Fig. 4F). This interaction was independently verified using Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays (Fig. 4G). Amh protein consist of two unequal domains: a long N-terminal domain (green) and a short C-terminal domain (orange) (Fig. 4Ha), with the latter carrying the bioactivity60,61. The N-terminal domain enhances the bioactivity of the C-terminal domain but has no intrinsic bioactivity61,62. Bmpr2a, on the other hand, primarily contains a protein kinase domain (blue) and disordered regions within its C-terminus (pink) (Fig. 4Hb). Using molecular docking analysis, we found that the C-terminal domain of Amh interacts with the protein kinase domain of Bmpr2a (Fig. 4Hc). This was further supported by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) experiments. SPR analysis revealed that the C-terminal domain of Amh binds to the protein kinase domain of Bmpr2a with a dissociation constant (KD) of 1.394 μM (Fig. 4I). Notably, the binding affinity increased significantly when using the full-length Amh, resulting in a KD of 0.1161 μM—a ten-fold decrease—suggesting that the N-terminal domain enhances the interaction between the C-terminal domain of Amh and the protein kinase domain of Bmpr2a (Fig. 4J). Taken together, these results strongly demonstrate the receptor-ligand relationships between Amh and Bmpr2a.

Knockout of bmpr2a disrupts the circadian clock and endocrine homoeostasis in zebrafish

To investigate the functions of bmpr2a in zebrafish in vivo, bmpr2a-mutated zebrafish were generated using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. A targeting site in the second exon was chosen to disrupt all functional domains. Ultimately, a 13-bp deletion (named bmpr2a−13) and a 5-bp deletion (named bmpr2a−5) were identified and selected to establish mutant lines (Fig. S6A). The genotypes of WT zebrafish and two types of homozygotes were confirmed by genomic sequencing (Fig. S6B). The frameshift mutations in bmpr2a−13 and bmpr2a−5 resulted in truncated proteins lacking all functional domains due to premature termination codons (Fig. S6C).

To examine the role of bmpr2a in zebrafish circadian clock regulation, we performed locomotor activity experiments on WT and bmpr2a-mutated adult zebrafish (bmpr2a−/−). Continuous behavioural monitoring revealed that WT female zebrafish showed a typical diurnal pattern, with most activity occurring during the light periods under LD condition (Fig. 5A). In contrast, in bmpr2a−/− mutants, locomotor activity consistently remained reduced during the multiple ZT0–14 periods and increased during the multiple ZT14–24 periods, indicating a severe disruption of their behavioural rhythms (Fig. 5A). Notably, the total locomotor activity was significantly decreased in bmpr2a−/− mutants under LD condition (Fig. 5B). Moreover, there was a less pronounced disparity in average activity between the light- and dark-phase in bmpr2a−/− mutants compared to WT (Fig. 5C). In addition, the moving distance and activity of bmpr2a−/− mutants were significantly decreased during the light-phase and increased during the dark-phase (Fig. 5D, E). Importantly, similar phenotypes were observed in the bmpr2a−/− mutants under DD condition (Fig. 5F–J). The acute disruption of locomotor activity rhythms in bmpr2a−/− mutants suggests the alteration of their circadian system.

The locomotor activities were monitored and analyzed in the bmpr2a−/− mutants and corresponding WT female zebrafish under LD (A–E) and DD (F–J) conditions. The total locomotor activities in 72 h (B, G), the quantification of average activities (C, H), and the moving distance and activity during the light-phase (D), dark-phase (E), subjective day (I) or subjective night (J) were shown. In the waveforms of locomotor activities, each point was calculated from the 5 min binned data across 3 days. For violin plots, dots and triangle correspond to individual zebrafish and the black and grey horizontal lines display the median as well as 25th and 75th percentiles. The box-and-whisker plots were presented as interquartile ranges with the median indicated by a line and whiskers extending from the minimum to the maximum values. For B–E n = 12 (WT) and n = 20 (bmpr2a−/−), G–J n = 12 (WT) and n = 24 (bmpr2a−/−). Statistical analysis was performed using two-sided unpaired t-test. K The quantification of the activity variance relative to respective WT among the amh−/−, bmpr2a−/−, or amh−/−;bmpr2a−/− mutants. L Cyclic expression of core clock genes in pituitaries harvested at the seven indicated time points across 24 h under DD condition from WT and bmpr2a−/− females. Target gene expression levels are shown relative to the beta-actin 2 reference gene actb2. The expression of WT CT22 was used for normalization. Data are plotted as mean values ± SD, n = 3, two-sided unpaired t-test. ZT represents zeitgeber time, where ZT 0 corresponds to lights on; CT represents circadian time. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Furthermore, we established double knockout mutants (amh−/−;bmpr2a−/−) by crossing animals with single deletion of amh and bmpr2a. Similar to amh−/− or bmpr2a−/− mutants, amh−/−;bmpr2a−/− mutants displayed a clear reduction in locomotor activity during the subjective day and an increase in locomotor activity during the subjective night (Fig. S6D). Importantly, the severity of these phenotypes in amh−/−;bmpr2a−/− mutants is comparable to that observed in amh−/− or bmpr2a−/− mutants (Fig. 5K), highlighting the dependence of the phenotypes on Bmpr2a-mediated Amh signalling.

We further examined the expression oscillations of the circadian molecular clock in bmpr2a−/− mutants, including the core transcription activators and two negative feedback pathway genes. First, we observed synchronized expression oscillations of clock genes in the WT pituitary under DD condition, aligning with the subjective day/night periods (Fig. 5L). This observation is consistent with previous reports43,44,45,46,47,48,49. Compared with the WT, a visibly dampened amplitude of clock gene expression rhythms was observed in the pituitary gland of bmpr2a−/− zebrafish, showing a significant downregulation of per1b, per3, clocka and rev-erbβ2 at multiple time points, especially the peak expression (Fig. 5L). To broaden our understanding, we extended our analysis to other tissues. In contrast to WT, it also appeared a clearly dampened amplitude of clock gene expression rhythms in the kidney, liver and heart of bmpr2a−/− zebrafish. Notably, rev-erbβ2 and clocka expressions are significantly down-regulated particularly at the peak point (Fig. S7A). Taken together, these data indicate that bmpr2a is essential for zebrafish circadian clock regulation.

We also examined the expression pattern of hormone genes that were expressed in the Amh-targeted pituitary cell lineages, including gh1, lhb, fshb and tshba. All of these hormone coding genes displayed a severely disrupted expression rhythm in bmpr2a−/− pituitaries compared with the WT control (Fig. S7B). Thus, bmpr2a has a similar function to amh in controlling circadian clocks and hormonal circadian rhythms. Furthermore, we carefully examined the embryonic development of amh−/− and bmpr2a−/− mutants at multiple stages (24, 54 and 106 hours post-fertilization (hpf)). Our results revealed that both mutants were morphologically indistinguishable from WT controls at all examined stages (Fig. S7C), indicating that the loss of amh or bmpr2a does not results in overt morphological abnormalities during embryonic development. In summary, these data demonstrate that Amh regulates the zebrafish circadian clock through its receptor Bmpr2a in vivo.

Transcriptional control of the circadian clock by the Amh/Bmpr2a-Smad signalling pathway

Amh is a member of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) family that recruits Smad proteins as an active transcription factor to regulate target gene expression55. We found that phosphorylated Smad1/5/9 colocalized with Amh in the PPD of the WT pituitary (Fig. S8A). Moreover, in both amh−/− and bmpr2a−/− zebrafish, there was a significant decrease in the average number of phospho-Smad1/5/9 (P-Smad1/5/9) positive cells in the pituitary (Fig. S8B–E), indicating an impaired activation of Smad1/5/9 signalling.

To further define Smad1/5/9-regulated transcriptional programmes, we performed CUT&Tag experiment with P-Smad1/5/9 antibody in the pituitary glands of WT, amh−/− and bmpr2a−/− mutants, producing highly reproducible data (Fig. S9A). Our analysis unveiled predominant CUT&Tag signals at transcription start sites (TSSs), as depicted in Fig. S9B. Of significance, in the WT pituitary, we observed P-Smad1/5/9 binding to most clock genes, in contrast to a reduced occurrence of such binding in the amh−/− and bmpr2a−/− mutants (Fig. 6A and Supplementary Data 2). Notably, a clear reduction in P-Smad1/5/9 signals was evident at specific clock gene TSSs, exemplified by rev-erbβ2, per1b and cry2 (Figs. 6B and S9C), and extended to numerous other clock gene TSSs in amh−/− and bmpr2a−/− mutants (Figs. 6C and S9D). These findings strongly suggest a requirement of Amh-Bmpr2a axis for P-Smad1/5/9 binding at clock gene promoters.

A Column chart showing the percentages of circadian clock genes bound by P-Smad1/5/9 revealed by the CUT&Tag assay in pituitaries from WT, amh−/− and bmpr2a−/− mutants. B UCSC Genome Browser tracks of CUT&Tag signals at circadian clock genes, such as the rev-erbβ2 loci. C Metagene analysis showing the CUT&Tag signals of P-Smad1/5/9 at circadian clock gene promoters in WT, amh−/− and bmpr2a−/− pituitaries. Two-sided unpaired t-test, ***p = 1.568e-08 (WT vs amh−/−), ***p = 5.546e-05 (WT vs bmpr2a−/−). TSS, transcription start site. D The numbers of typical clock gene cis-regulatory elements bound by P-Smad1/5/9. E Global profile of P-Smad1/5/9 at typical cis-regulatory elements of clock genes.

Further analysis revealed that in WT pituitary, a substantial number of P-Smad1/5/9 binding sites harbour typical cis-regulatory elements of clock genes, including the E/E’-box (CACGT[G/T])63,64, REV-ERB/ROR binding elements (RRE, [A/T]A[A/T]NT[A/G]GGTCA)64, cAMP response elements (CRE, TGACGTCA)65 and DBP/E4BP4 binding elements (D-box, TTA[T/C]GTAA)64,66 (Fig. 6D and Supplementary Data 3). This suggests that P-Smad1/5/9 might regulate multiple transcriptional circuits of the molecular clock through these elements. Notably, the D-box, which serves as a light-regulated enhancer element in zebrafish67,68,69, showed considerably less binding of P-Smad1/5/9 compared to the E/E’-box (Fig. 6D). Moreover, in contrast to a slight reduction in P-Smad1/5/9 binding to the D-box, a more pronounced reduction at the E/E’-box, REE and CRE was observed in both amh−/− and bmpr2a−/− pituitary (Fig. 6E and Supplementary Data 3). In addition, no obvious P-Smad1/5/9 signal was observed at the TSSs of cry5 (6–4 photolyase) (Fig. S9E), a purely light-induced gene70. These results suggest that the light input pathway of circadian clock may not substantially contribute to Amh/Bmpr2a-Smad1/5/9 signalling-mediated rhythmic regulation. Collectively, these findings suggest that Amh-Bmpr2a-Smad1/5/9 axis transduce the signal for clock gene expression through specific targeting of a subset of typical clock gene cis-regulatory elements.

To bolster this model, we examined the protein levels of Amh during the light-dark cycles and constant darkness conditions in blood of WT fish. Our results revealed a robust circadian rhythm in Amh protein levels in both conditions, correlating with clock gene oscillations (Fig. 7A). Additionally, Amh administration induced a significant dose-dependent increase in clock gene expression (Figs. 7B and S10A). Notably, this Amh-induced effect on clock gene expression was absent in the bmpr2a−/− mutants (Figs. 7C and S10B) or upon P-Smad1/5/9 inhibition (Figs. 7D and S10C). Furthermore, the circadian oscillations of clock genes are perturbed when P-Smad1/5/9 is inhibited (Figs. 7E and S10D) or in bmpr2a knockout pituitary (Fig. 5L). Hence, these findings substantiate the notion that the rhythmic Amh signal sustains circadian rhythms through the Bmpr2a-Smad1/5/9 pathway.

A The expression rhythm of Amh in WT zebrafish. B Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of core clock genes in pituitaries after treatment with different concentrations of recombinant Amh or saline as a control. The expression of control group was used for normalization. C Expression levels of clock genes in pituitaries after treatment with recombinant Amh in WT and bmpr2a−/− mutants. The expression of WT + saline group was used for normalization. D Expression levels of core clock genes in pituitaries after treatment with recombinant Amh, Amh + P-Smad1/5/9 inhibitor or saline as a control. The expression of control group was used for normalization. E The oscillation of clock gene expression in the WT pituitaries when P-Smad1/5/9 is inhibited. The expression of WT ZT2 was used for normalization. All the data are presented as mean values ± SD, and the individual data points are depicted (n = 3, part of n = 6 in (C)). Statistical analysis was performed using two-sided unpaired t-test. F A schematic model depicting the role of Amh/Bmpr2a-Smad1/5/9 signalling pathway in the regulation of circadian rhythms. We propose that Amh signalling regulates the oscillation of molecular clock in the hypophysis in a cell type-specific manner, thereby accurately gating the major output pathway of circadian information. Amh signalling deficiency causes corresponding circadian endocrine and behavioural rhythm disorders. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In summary, our data demonstrated that Amh-Bmpr2a regulates circadian clock gene expression and oscillation through Smad1/5/9-mediated transcription, thereby maintaining the homoeostasis of the internal timing system and the endocrine system.

Discussion

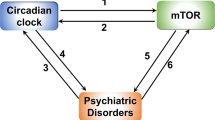

The circadian clock is an internal timing system consisting of three main components: an input pathway, an endogenous oscillator generating the circadian signal, and an output pathway through which downstream physiological and behavioural processes can be synchronized with the oscillator25. The clock output is transmitted via the hypothalamic-pituitary axis (HPA) and the autonomic nervous system (ANS)68,71,72. Endocrine and neural signals, serving as entrainment cues, are thought to be involved in the systemic homoeostasis and interactions among tissue oscillators in vertebrates11,13,68,72,73, but the mechanisms by which these are mediated and integrated are poorly understood. Here, we identify Amh hormone as an essential regulator of vertebrate circadian clocks. As shown in Fig. 7F, we propose that Amh signalling sustains molecular clock oscillations in pituitary cell types, including somatotropes, gonadotropes, and thyrotropes. This signalling ensures precise gating of the major output pathways of circadian information, thereby maintaining rhythm coherence and circadian homoeostasis at both tissue and systemic levels. Specifically, pituitary clocks regulate the rhythmic expression of endocrine signals through E/E’-boxes in the promoter regions of hormone-coding genes such as gh1, fshb, lhb, and tshba74. These endocrine signals synchronize downstream physiological processes in peripheral tissues with the oscillator. Loss of function of amh or its receptor bmpr2a dampens molecular clock oscillations, disrupts hormonal and behavioural circadian rhythms, and affects circadian rhythms in multiple peripheral tissues (Fig. 7F). Mechanistically, Amh signals by binding to its receptors, Bmpr2a/Bmpr1bb, and recruiting the Smad1/5/9 proteins, which are subsequently phosphorylated and translocated to the nucleus to regulate clock gene expression via multiple clock-controlled elements, including E/E’-boxes, RREs and CREs (Fig. 7F), providing a molecular mechanism for hormonal control of clock gene expression.

It is noteworthy that fish lack an SCN structure comparable to that found in mammals, such as rodents75,76,77. Instead, evidence suggests a more “primitive” organisation characterized by multiple distributed nuclei, speculated to collectively serve as the location of a central clock76,78,79,80. Precise mechanisms by which these nuclei are interconnected and interact with the pituitary gland require future investigation. Interestingly, the zebrafish pineal gland clock is possibly as part of a complex multiple pacemaker system, however, the precise organizations of this multicomponent clock system within the zebrafish brain are not clear76,77,78. Moreover, light entrains peripheral clocks in fish through direct exposure of cells and tissues to light, facilitated by widely expressed opsin photoreceptors. This direct light input bypasses the need for indirect signalling through the retina and a central SCN clock49,81,82. Consequently, the hierarchical organisation of circadian timing systems in fish and mammals differs fundamentally. Additionally, transcription factors such as Tef and Dbp, which bind to and activate transcription via D-boxes, play a role in the light input pathway in fish67,83,84. Unlike in mammals, where they serve as clock components or outputs66, in fish, D-boxes function as light-regulated enhancer elements rather than clock-regulated enhancers67,68,69, underscoring further distinctions between the two systems. Considering the similar phenotypes observed in amh−/− and bmpr2a−/− mutants under both LD and DD conditions, coupled with the absence of significant binding of P-Smad1/5/9 at D-boxes, our findings suggest that Amh/Bmpr2a-Smad1/5/9 signalling pathway probably operates as a light input pathway-independent regulator of circadian clock. Our findings also reveal Amh is an essential endogenous factor for the molecular clock oscillations in hypophysis and the maintenance of hormonal and behavioural rhythms. These suggest that the hypophysis clock is possibly as part of a multicomponent clock system in zebrafish brain, opening new avenues for mechanistic research on circadian systems in fish.

The pituitary gland, which serves as the central relay station for brain output signals, contains its own molecular clock capable of autonomous oscillation85,86, and this rhythm is not abolished by SCN lesions in vivo87. Moreover, intrinsic circadian clocks have a broad influence on the pituitary transcriptome88,89,90 and hormone-coding gene expression rhythms91,92,93,94. Thus, circadian clock function within the pituitary contributes to the normal execution of processes with time-of-day-dependent activity. Interestingly, the pituitary gland shows the most robust rhythm-generating capacity among peripheral tissues87,95. However, it is still not clear how intrinsic circadian clocks in the pituitary gland are regulated in vivo. We have shown here that the Amh hormone is required for the high-amplitude circadian transcription of core clock genes in the pituitary and gates endocrine and behavioural circadian rhythms (Figs. 1 and S2B), revealing an important molecular mechanism of endocrine-clock crosstalk. Some recent evidence has revealed roles of Amh in neuroendocrine function in the brain96,97,98. The pituitary gland is a vital component of the neuroendocrine system present in all vertebrates99. Our data demonstrate the functional mechanism of Amh in the hypophysis and circadian clock in vivo, hinting that Amh plays a critical role in the neuroendocrine regulation of the vertebrate circadian clock.

Although the circadian clock is cell autonomous, coupling between cell-autonomous oscillators is essential to prevent the desynchronization of cellular networks and the disruption of circadian tissue functions and circadian homoeostasis8. It is poorly understood how these cells are coordinated to maintain coherent tissue rhythms and which mechanisms control molecular clocks within these distinct cells or cell populations. The pituitary gland provides an excellent model for investigating this puzzle because it is a highly heterogeneous organ and harbours several distinct endocrine cell lineages that are implicated in the expression of both circadian and seasonal endocrine cycles30,99. Combined with FACS and scRNA-seq technologies, we sorted and identified Amh-targeted pituitary cell populations and revealed that Amh mainly regulates clock gene expression and cell numbers among somatotropes, gonadotropes and thyrotropes (Figs. 2 and 3). Moreover, we identified Bmpr2a as the receptor of zebrafish Amh and found that bmpr2a was mainly expressed in Amh-targeted cell lineages. bmpr2a deficiency causes a phenotype similar to that of amh mutants, further confirming these results (Figs. 4 and 5). Hence, these data fully elucidate the cell type-specific regulation of the molecular clock in the pituitary by Amh-Bmpr2a signalling. Our findings provide a cellular explanation for phenomena that have been well documented at the tissue and systemic levels; that is, pituitary cells can translate rhythmic secreted factors or neuronal activity into signals that regulate the amplitude of hormone secretion from the pituitary9,100. This mechanism ensures a temporally and spatially precise extension of the circadian clock output in a cell-specific manner.

The circadian regulation of the transcription of clock and clock-related genes is indicative of an integrated network of regulatory loops of great complexity101,102, making it difficult to understand without the comprehensive identification of network circuits in vivo103. Convincing evidence has revealed numerous conserved and functional cis-regulatory elements in clock and clock-related genes, especially E/E’-box regulatory elements, which are recognized as a structural keystone of the circadian clock4,64. Our work shows that most clock genes are regulated directly by P-Smad1/5/9 transcriptional coactivators in vivo through several canonical clock-controlled elements, such as E/E’-boxes (Fig. 6), hinting a conserved function of the Amh-Smad signalling pathway in vertebrate circadian clock regulation. The binding of P-Smad1/5/9 to different clock-controlled elements reveals a broad role of Amh-Smad signalling in the regulation of multiple complex transcriptional regulatory circuits of the circadian clock, and the molecular mechanisms still need to be further explored. The circadian oscillators hosted in peripheral tissues are able to integrate multiple time cues104, as observed in the pituitary and liver. How these zeitgeber signals are transmitted to the cell nucleus are poorly understood. Our findings indicate that an endocrine factor carrying time information initiates signal transduction through a ligand‒receptor interaction, and signalling then converges to result in the nuclear accumulation of transcriptionally active Smad complexes, revealing a crucial network circuit of clock transcriptional regulation. In addition to neurons96, the hypothalamus97 and the pituitary, AMH and AMHR2 have also been detected in multiple other tissues in females, such as the ovaries105, breasts106, uterus107, placenta108, and lungs109. Thus, this signalling model may have wider applications, not only for the temporal action of Amh on its target pituitary cells but also for the long-term maintenance of precise, high-amplitude circadian transcription of genes in other tissues.

Circadian misalignment, which often arises in modern society, has been linked to various diseases. A molecular understanding of circadian time will provide therapeutic insights that can help prevent and treat disease. AMH has been reported to be associated with multiple human reproductive diseases, such as PCOS, POI, GCT, and congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (CHH)98,110. Research into the physiological actions of AMH has rapidly expanded from studying its classical roles in gonadal development and sexual differentiation to the routine clinical use in reproductive health and as a biomarker in the diagnosis of female reproductive diseases. Recently, it was reported that declining female fertility results partially from an abnormal circadian clock caused by aberrant clock genes or unhealthy diet and sleep habits in modern life111. Thus, elucidating the role and mechanism of Amh signalling in circadian clock regulation in vivo has important implications not only for circadian physiology but also for understanding pathologies associated with circadian rhythm disruption. To achieve a system-level understanding of circadian mechanisms in medicine, further studies are needed to characterize the mechanisms of and associations between Amh-mediated circadian clock regulation and Amh-related diseases.

Methods

Animals

The AB line zebrafish used in this study were purchased from the China Zebrafish Resource Center and reared in the zebrafish facility at the Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Zebrafish amh mutants were generated by using CRISPR/Cas9 technology as described in our previous report59. The maintenance, breeding, and staging of zebrafish were performed according to standard methods112. The mutant zebrafish used in this study were siblings of the WT controls and were raised in the same tanks before experiments. Seven to twelve-months old adult female zebrafish were used in the experiments. All animal experiments and treatments were performed with the approval of the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Behavioural assessment

Zebrafish behavioural assays were performed under both the light-dark (14 h:10 h) cycles and constant darkness conditions, as described previously with modifications47. Briefly, adult amh−/−, bmpr2a−/−, amh−/−;bmpr2a−/− mutants and corresponding WT female zebrafish were placed in a tank filled with rearing water, and their locomotor activities were monitored and recorded for a continuous 72 h period under LD and DD conditions using an automated video-tracking system (DanioVision Tracking System, Noldus Information Technology, Netherlands). The video-track quantization parameters were set as described previously113. Live video tracking and analysis were conducted using EthoVision XT 15 software (Noldus Information Technology). Tracks were analysed to determine the total distance moved by each zebrafish per 1 min time bin. The evaluation of the circadian rhythmicity of zebrafish behaviour was conducted by using ActogramJ software114.

Anti-Amh antibody and recombinant bioactive Amh preparation

The antibody used for the immunocytochemical detection of endogenous Amh in the adult zebrafish pituitary was prepared by Mabnus Biotech Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China) according to a previous report115. In brief, mice were immunized with peptides (against aa 441-456—QRAARADEDGPSASNQ) conjugated to keyhole limpet haemocyanin (KLH) through an added N-terminal cysteine four times at intervals of 28 days, 14 days and 14 days. Freund’s complete adjuvant (FCA) was used in the first injection, and Freund’s incomplete adjuvant (FIA) was used in the remaining injections. The antisera were purified with an affinity column coupled with the peptides, and this step was followed by dialysis and concentration. The antisera were then collected and stored at -80 °C.

Biologically active recombinant zebrafish Amh was produced as described in previous studies on zebrafish and humans105,115. The sequence encoding the zebrafish Amh protein C-terminal amino acids (Cys457-Arg549) was synthesized and inserted into the pET32a vector. Then, the expression plasmid containing the inserted sequence was used to transfect calcium chloride‐competent E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells. Recombinant Amh expression was induced by isopropyl thiogalactoside (IPTG) at a final concentration of 0.4 mM. After 3 h of induction, the culture was harvested by centrifugation at 6000 g and 4 °C for 5 min, and the pellet was suspended in 25 ml of lysis buffer (100 mM NaCl; 10 mM Tris‐HCl, pH 8; and 50 mM NaH2PO4). The cells were then sonicated on ice (eight 1 min pulses), and the debris was centrifuged at 14,000 g and 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant and precipitate were analysed by 15% SDS‐PAGE.

The soluble fraction was filtered through 0.22‐μm membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA), and the recombinant Amh was purified from the supernatant using an affinity Ni‐NTA superflow column (Qiagen) equilibrated with lysis buffer. The purified product (15 μl) was analysed by 15% SDS‐PAGE. The fractions containing the purified protein were dialysed against lysis buffer. After sterile filtration with 0.22‐μm membranes, the protein concentration was determined by Bradford’s method (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

Immunofluorescence analysis

For immunofluorescence examination, the intact pituitaries of adult zebrafish were carefully dissected after anaesthetization with MS-222 (Sigma, USA) and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma, USA) overnight at 4 °C. The fixed samples were dehydrated, embedded in paraffin and sectioned at a 4 μm thickness. Immunofluorescence detection was performed as previously described59. After deparaffinization, the slides were rehydrated in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 20 min, repaired in citrate-EDTA antigen retrieval solution (Beyotime), and incubated with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 2% goat serum in PBS for 1 h at room temperature to avoid the nonspecific binding of antibodies. The tissues were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibodies [anti-Amh antibody (mouse, 1:200), anti-phospho-Smad1/5/9 antibody (Cell Signalling Technology, 13820, Rabbit, 1:800)] diluted in blocking solution. After washing, the tissues were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with Alexa Fluor secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA, Cat. Nos. A32723, A32727, A32731, A32732) diluted 1:500 in blocking solution for the detection of the primary antibodies. DNA was stained with DAPI (Sigma), and the samples were photographed using a Leica SP8 confocal microscope (Leica, Jena, Germany). Experiments were performed at least in triplicate, and a series of sections were observed. The histological analyses of pituitaries were based on previous reports116,117.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting and analysis

Adult female zebrafish were anaesthetized with MS-222, and their pituitaries were collected under a dissecting microscope and immediately immersed in ice-cold PBS. After washing 2–3 times with ice-cold PBS, the pituitaries were enzymatically dissociated using 0.15% trypsin (Biological Industries, Israel) to obtain single-cell suspensions following the method previously described33. After blocking with 2% BSA, the dissociated cells were incubated with an anti-Amh antibody or an isotype control antibody (mouse IgG, 1:100). After washing three times, the cells were labelled with a goat anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA, A32727) and physically purified using a MoFlo-XDP High-Performance Cell Sorter (FACSAria III, Beckman Coulter). The sorting decision was based on measurements of RFP fluorescence (excitation: 561 nm, detection: RFP bandpass 575/10 nm) by comparing cell suspensions from the anti-Amh antibody- and isotype control antibody-labelled groups. Total RNA was extracted from the captured cells and used to synthesize first-strand complementary DNA with a RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Probe synthesis and fluorescent in situ hybridizations

Probes for zebrafish gh1, fshb, lhb, tshba and bmpr2a were transcribed in vitro using a Fluorescein or Digoxigenin (DIG) RNA labelling kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Specific primers with a T7 RNA polymerase promoter were designed to amplify the complementary DNA (cDNA) fragment of each gene (Supplementary Table 1). Each probe was used at a final concentration of 0.5-1 ng/μl. After anaesthetization with MS-222, the intact pituitaries of adult female zebrafish were sampled and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4 °C overnight. The fixed pituitaries were dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at a 4 μm thickness and stored at -80 °C.

mRNA detection by multicolour FISH was performed as previously described118 using the Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA)-Plus Cyanine 3/Cyanine 5 System (Perkin Elmer, USA, Cat. Nos. NEL752001KT). The sections were stained with DAPI (Sigma) and imaged with a Leica SP8 confocal microscope (Leica, Jena, Germany).

Phylogenetic analysis and gene synteny analysis

All full-length coding sequences of Amhr2, Bmpr2a and Bmpr2b used for comparison were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Alignment was performed using the MAFFT algorithm119. The TIM2 + I + G4 model was chosen as the best-fit DNA substitution model using ModelTest-NG version 0.1.16120. Phylogenetic reconstructions were established via the maximum likelihood (ML) method implemented in RAxML version 8.2.12 with 200 bootstrap replicates121. Amhr2 of Protopterus annectens was chosen as the outgroup.

Syntenic regions of the bmpr2a and bmpr2b genes were searched in the NCBI GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Conserved synteny was constructed based on the alignment of the target genes and genomic annotation according to the GenBank database.

Coimmunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis

To generate Flag- or HA-tagged expression plasmids, the full-length cDNAs of zebrafish Bmpr2a, Bmpr1bb (Alk6b), and Amh were inserted into a pCS2(+) vector. GFP was cloned into pCS2(+) as a control. The primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 1 in the Supplementary Information.

Coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assays and Western blotting were performed as previously described122. Briefly, 293T cells seeded in 10 cm dishes were transfected with 10 μg of the indicated plasmids. At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were washed twice with 10 ml of ice-cold PBS and lysed in 1 ml of NP-40 lysis buffer (Beyotime) containing protease inhibitors at 4 °C for 30 min on a rocking platform. The cellular debris was removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant was incubated with anti-HA Dynabeads (Bimake, B26202, USA) overnight at 4 °C. The beads were washed five times with washing buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 1% NP-40] and eluted with SDS‒PAGE protein loading buffer (Beyotime) by boiling for 8 min at 99 °C. The precipitated proteins were separated on a 10% SDS‒PAGE gel, transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore), and incubated with an anti-HA antibody (ABclonal, AE008, Mouse) and an anti-Flag antibody (Cell Signalling Technology, 2368S, Rabbit). The blots were detected with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) (ABclonal, AS014) and HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) (ABclonal, AS003) and visualized using an ImageQuant LAS 4000 mini instrument (GE Healthcare, USA).

Yeast two-hybrid assays

Yeast two-hybrid assays were performed as previously described123. Briefly, the amh and bmpr2a were constructed into the pBT3-SUC bait vector and pPR3-N prey vector, respectively. Next, specific bait and prey vectors were co-transformed into yeast strain NMY51. The pBT3-SUC-amh + pPR3-N was set for detection of self-activation. The pTSU2-APP + pNubG-Fe65 and pTSU2-APP + pPR3-N were used as the positive and negative control, respectively. Co-transformants were simultaneously plated on selection medium containing SD-TL (SD/-Leu-Trp), SD-TLH (SD/-Leu-Trp-His) and SD-TLHA (SD/-Leu-Trp-His-Ade) with the appropriate concentration of 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT) and incubated at 30 °C. Yeast growth statuses were observed after 3–5 days of incubation at 30 °C.

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays

BiFC assays were performed as described previously124, with slight modification. Briefly, the amh and bmpr2a were inserted into the pBiFC-VN173 and pBiFC-VC155 vectors respectively. Amh-VN173 + VC155 and VN173 + Bmpr2a-VC155 served as negative controls. bJun-VN173 + bFos-VC155 served as a positive control. The 293T cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The transfected cells were cultured overnight in an incubator. Then, the cells were rinsed in PBS solution and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS and imaged by fluorescence microscope.

Protein expression and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) assays

The proteins used in SPR assays were expressed in the FreeStyle™ 293-F cells (HEK-293F, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, A14527) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 8% CO2 and gentle shaking. 6 days after transfection, the culture medium was collected and centrifuged. The culture medium was filtered via 0.22 μm filter, and incubated with Protein A Sepharose FastFlow (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA, 17127901) and pre-equilibrated with a PBS buffer for 2 h at 4 °C. After incubation, the resin was loaded on the column and washed with wash buffer (WB, 1× PBS pH 7.4; 300 mM NaCl). The final step was performed using an elution buffer (EB; 0.1 M glycine, pH = 3.0). Fractions with the highest absorbance at λ = 280 nm were collected and then either directly dialysed for further experiments or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

The SPR assays were performed using a Biacore T200 instrument (GE Healthcare, BR-1100-64) with CM5 sensor chips (GE Healthcare) at 25 °C as previously described125. The buffer system was PBST (10 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4 pH 7.4, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 0.05% Tween 20). The full-length Amh or C-terminal domain protein was pre-immobilized 15000RU on the CM5 sensor chip using standard amine coupling chemistry with a 40 μg/mL concentration. Serially diluted Bmpr2a domain protein was flowed over the chip to evaluate the binding affinities. The binding kinetics were analysed with the Biacore T200 Evaluation Software (GE Healthcare) using the 1:1 Langmuir binding model.

Protein structure and molecular docking analysis

The 3D structures of the Amh and Bmpr2a proteins were predicted using AphaFold3 server (https://golgi.sandbox.google.com/). Molecular docking analysis was performed using HDOCK server (http://hdock.phys.hust.edu.cn/) and the docking data were visualized by PyMOL software.

Establishment of bmpr2a mutant zebrafish

bmpr2a mutant zebrafish were generated using CRISPR/Cas9 technology as previously described59. In brief, the guide RNA (gRNA) target sites were designed with an online tool, ZIFIT Targeter (http://zifit.partners.org/ZiFiT/CSquare9Nuclease.aspx), and a BLAST search of the zebrafish genome was performed to avoid off-target effects. The pCS2-Cas9 expression vector was linearized with the XbaI enzyme, purified and transcribed into Cas9 mRNA using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 ULTRA kit (Ambion, USA). The purified DNA templates were transcribed into gRNA with the TranscriptAid T7 High-Yield Transcription Kit (Thermo Scientific, USA). Cas9 and gRNA mRNAs were purified by lithium chloride precipitation and coinjected into one-cell-stage zebrafish embryos (Cas9 mRNA: 300 ng/ml, gRNA: 20 ng/ml). bmpr2a mutations were analysed by genomic PCR and sequencing as previously described59. The primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 1 in the Supplementary Information.

Amh treatment, RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Intraperitoneal injection was performed according to a previous report126. Adult WT female zebrafish were injected intraperitoneally with 0.01 or 0.12 μg/g body weight of recombinant Amh97,108, saline (0.75% NaCl, used as a control), or 0.12 μg/g Amh and 3 mg/kg LDN193189 hydrochloride (blocker of Smad1/5/8(9) phosphorylation, ApexBio, USA, Cat. No. A3545)127,128.

Female zebrafish tissues were isolated from the amh−/−, bmpr2a−/−, corresponding WT, and various injection groups. Total RNA isolation was performed using the SV Total RNA Isolation System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The isolated RNAs were reverse transcribed with the GoScriptTM Reverse Transcription System (Promega, USA) or the QuantiNovaTM Reverse Transcription Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT‒PCR) was performed with the CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) as previously described129. Beta-actin 2 (actb2) was used as an endogenous control. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and the data were analysed using the 2–ΔΔCT method. The gene-specific primer sequences are shown in Supplementary Table 1 in the Supplementary Information.

Single-cell RNA library preparation and sequencing

A single-cell RNA-seq assay was performed as previously described with minor modifications33. After dissection, zebrafish pituitaries from WT or amh−/− females were washed with cold PBS or fresh Ringer’s solution for 5–10 min, followed by mechanical and enzymatic dissociation in protease solution (0.25% trypsin (Life Technologies), 400 mg/ml collagenase D (Sigma) and 1 mM EDTA in PBS) and incubated at 28.5 °C for 20–30 min or until full dissociation was observed. Dissociation was stopped by the addition of 6X stop solution (6 mM CaCl2 and 30% foetal bovine serum (FBS) in PBS). The samples were filtered with a 40 μm cell strainer, centrifuged (400 g, 5 min, 4 °C) and then resuspended in 1X PBS. Single-cell cDNA libraries were synthesized using 10X Genomics Chromium Single Cell 3’ Library & Gel Bead Kit v3.1 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq machine using PE150.

High-throughput CUT&Tag

The CUT&Tag assay was performed as previously described with minor modifications130. Briefly, nuclei were harvested from a mass of zebrafish pituitary cells. Nuclei (106) were washed and incubated with 10 μl concanavalin A-coated magnetic beads. Bead-bound cells were then resuspended with dig-wash buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5; 150 mM NaCl; 0.5 mM spermidine; 1X protease inhibitor cocktail; 0.05% digitonin; and 2 mM EDTA) and a 1:50 dilution of primary anti-phospho-Smad1/5/9 antibody (Cell Signalling Technology, 13820, Rabbit, USA) or control IgG on a rotating platform overnight at 4 °C. The beads were washed in dig-wash buffer, and the primary antibody was removed using a magnetic stand and then incubated with a secondary antibody (1:100) for 60 min. After incubation, the beads were washed in dig-Hisalt buffer and incubated with the proteinA-Tn5 adaptor complex for 1 h. Next, the cells were resuspended in Tagmentation buffer (10 mM MgCl2 in Dig-med Buffer) and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The DNA fragments were purified using phenol‒chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction and ethanol precipitation. The sequencing libraries were prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions and cleaned using XP beads (Beckman Counter). Sequencing was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Vendor’s information) using 150 bp paired-end sequencing following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Analysis of single-cell RNA-seq data

Raw sequencing data were demultiplexed and aligned to the ENSEMBL GRCz11 zebrafish transcriptome to generate feature-barcode matrices using CellRanger (v5.0.1) with the default parameters. Next, the Seurat (v4.0.6) R package was used for downstream analyses131. Cells with <500 or >3000 unique genes were excluded, as they likely represented poor recovery or doublets. Cells with <500 UMIs or >10% mitochondrial gene expression were also removed. After filtering for quality, we further use DoubletFinder (v2.0.4) with default parameters to detect the potential doublets in our datasets50. We finally obtained 2584 and 3046 cells from the WT and amh−/− groups, respectively. We used “FindIntegrationAnchors” and “IntegrateData” to generate an aggregated matrix by aligning two libraries to suppress technical variance. Cell types were annotated with the combination of known markers for each cluster. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified by the function “FindAllMarkers” or “FindMarkers” in Seurat packages using “wilcox” test methods, and Bonferroni correction and GO biological process (BP) analysis were performed with the clusterProfiler R package132.

Analysis of CUT&Tag data

Raw reads were filtered by Trimmomatic (v0.35) to remove adaptor sequences and low-quality reads133. Clean reads were aligned to the zebrafish GRCz11 genome using BWA (v0.7.17) with the default options134. Then, MACS2 (v2.1.2) was used for peak calling135. Only confident peaks with >4 folds enrichment and with q-value < 0.00001 over background were kept for subsequent analyses. Normalized BigWig files were generated from Bam files using RSeQC (v4.0.4) and then visualized using the UCSC Genome Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu). DeepTools (v3.5.0)136 was used to calculate the average read density across defined genomic intervals from normalized BigWig files and plot heatmaps of chromatin occupancy. The normalization method was read per million (RPM). In addition, we used HOMER (v4.9.1) to annotated the cis-regulatory elements137.

Statistics and reproducibility

No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. All the statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc. version 8.3.0) or R. For two-group comparisons two-sided Student’s t-test was used. The specific statistical test method used for each figure is detailed in the corresponding figure legends. Data are presented as mean values ± SD (standard deviation) or ±SEM (standard error of the mean) from at least three reproducible experiments. The violin and box plots were presented as interquartile ranges with the median indicated by a line. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All the p-values are provided on the figures or in the legends. No data were excluded from the analyses.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All the primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 1 in the Supplementary Information. The sequencing data generated in this study have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession code GSE283840 and GSE283841. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The source codes for the analysis including workflows in Snakemake and scripts in the paper are available at the https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15221596.

References

Sehgal, A. Physiology flies with time. Cell 171, 1232–1235 (2017).

Dunlap, J. C. Molecular bases for circadian clocks. Cell 96, 271–290 (1999).

Takahashi, J. S., Hong, H. K., Ko, C. H. & McDearmon, E. L. The genetics of mammalian circadian order and disorder: implications for physiology and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 764–775 (2008).

Takahashi, J. S. Transcriptional architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Nat. Rev. Genet. 18, 164–179 (2017).

Reppert, S. M. & Weaver, D. R. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature 418, 935–941 (2002).

Dibner, C., Schibler, U. & Albrecht, U. The mammalian circadian timing system: organization and coordination of central and peripheral clocks. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 72, 517–549 (2010).

McNamara, P. et al. Regulation of CLOCK and MOP4 by nuclear hormone receptors in the vasculature: a humoral mechanism to reset a peripheral clock. Cell 105, 877–889 (2001).

Koronowski, K. B. & Sassone-Corsi, P. Communicating clocks shape circadian homeostasis. Science 371, eabd0951 (2021).

Bedrosian, T. A., Fonken, L. K. & Nelson, R. J. Endocrine effects of circadian disruption. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 78, 109–131 (2016).

Andrés Q.-S., Adrian L.-M., Martín L.-R., J. N. Muñoz-Tabares, N. A. Ramírez-Rojas effects of pituitary hormones deficiency from the specific pituitary lobes on learning, memory and survival behavior in the Wistar rat. Faseb J. https://doi.org/10.1096/fasebj.2022.36.S1.0R814 (2022).

Tsang, A. H., Astiz, M., Friedrichs, M. & Oster, H. Endocrine regulation of circadian physiology. J. Endocrinol. 230, R1–R11 (2016).

Allada, R. & Bass, J. Circadian mechanisms in medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 550–561 (2021).

Gamble, K. L., Berry, R., Frank, S. J. & Young, M. E. Circadian clock control of endocrine factors. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 10, 466–475 (2014).

Liu, Y. et al. Loss of BMAL1 in ovarian steroidogenic cells results in implantation failure in female mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 111, 14295–14300 (2014).

Miller, B. H. et al. Circadian clock mutation disrupts estrous cyclicity and maintenance of pregnancy. Curr. Biol. 14, 1367–1373 (2004).

Li, S. et al. Altered circadian clock as a novel therapeutic target for constant darkness-induced insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism of polycystic ovary syndrome. Transl. Res. 219, 13–29 (2020).

Takasu, N. N. et al. Recovery from age-related infertility under environmental light-dark cycles adjusted to the intrinsic circadian period. Cell Rep. 12, 1407–1413 (2015).

Amano, T. et al. Expression and functional analyses of circadian genes in mouse oocytes and preimplantation embryos: Cry1 is involved in the meiotic process independently of circadian clock regulation. Biol. Reprod. 80, 473–483 (2009).

Pilorz, V. & Steinlechner, S. Low reproductive success in Per1 and Per2 mutant mouse females due to accelerated ageing? Reproduction 135, 559–568 (2008).

Silva, M. & Giacobini, P. New insights into anti-Mullerian hormone role in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and neuroendocrine development. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 78, 1–16 (2021).

Knauff, E. A. et al. Anti-mullerian hormone, inhibin B, and antral follicle count in young women with ovarian failure. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 94, 786–792 (2009).

Dewailly, D. et al. The physiology and clinical utility of anti-Mullerian hormone in women. Hum. Reprod. Update. 20, 370–385 (2014).

Farkkila, A. et al. The clinical utility of serum anti-Mullerian hormone in the follow-up of ovarian adult-type granulosa cell tumors–a comparative study with inhibin B. Int. J. Cancer. 137, 1661–1671 (2015).

Moolhuijsen, L. & Visser, J. A. Anti-mullerian hormone and ovarian reserve: update on assessing ovarian function. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 105, 3361–3373 (2020).

Balsalobre, A., Damiola, F. & Schibler, U. A serum shock induces circadian gene expression in mammalian tissue culture cells. Cell 93, 929–937 (1998).

Welsh, D. K., Yoo, S. H., Liu, A. C., Takahashi, J. S. & Kay, S. A. Bioluminescence imaging of individual fibroblasts reveals persistent, independently phased circadian rhythms of clock gene expression. Curr. Biol. 14, 2289–2295 (2004).

Welsh, D. K., Logothetis, D. E., Meister, M. & Reppert, S. M. Individual neurons dissociated from rat suprachiasmatic nucleus express independently phased circadian firing rhythms. Neuron 14, 697–706 (1995).

Zhu, X., Gleiberman, A. S. & Rosenfeld, M. G. Molecular physiology of pituitary development: signaling and transcriptional networks. Physiol. Rev. 87, 933–963 (2007).

Kelberman, D., Rizzoti, K., Lovell-Badge, R., Robinson, I. C. & Dattani, M. T. Genetic regulation of pituitary gland development in human and mouse. Endocr. Rev 30, 790–829 (2009).

Ikegami, K., Refetoff, S., Van Cauter, E. & Yoshimura, T. Interconnection between circadian clocks and thyroid function. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 15, 590–600 (2019).

Lobo, M. K., Karsten, S. L., Gray, M., Geschwind, D. H. & Yang, X. W. FACS-array profiling of striatal projection neuron subtypes in juvenile and adult mouse brains. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 443–452 (2006).

Crouch, E. E. & Doetsch, F. FACS isolation of endothelial cells and pericytes from mouse brain microregions. Nat. Protoc. 13, 738–751 (2018).

Fabian, P. et al. Lineage analysis reveals an endodermal contribution to the vertebrate pituitary. Science 370, 463–467 (2020).

Allada, R. & Chung, B. Y. Circadian organization of behavior and physiology in Drosophila. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 72, 605–624 (2010).

Di Rosa, V. et al. Daily rhythms of the expression of key genes involved in steroidogenesis and gonadal function in zebrafish. PLOS ONE 11, e157716 (2016).

Vázquez, F. J. S., Terry, M. I., Felizardo, V. O. & Vera, L. M. Daily rhythms of toxicity and effectiveness of anesthetics (MS222 and eugenol) in zebrafish (danio rerio). Chronobiol. Int. 28, 109–117 (2011).

Mosser, E. A. et al. Identification of pathways that regulate circadian rhythms using a larval zebrafish small molecule screen. Sci. Rep. 9, 12405 (2019).

Mota-Rojas, D. et al. Physiological and behavioral mechanisms of thermoregulation in mammals. Animals 11, 1733 (2021).

Ball, G. F. & Balthazart, J. Individual variation and the endocrine regulation of behaviour and physiology in birds: a cellular/molecular perspective. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B. Biol. Sci. 363, 1699–1710 (2008).

Balment, R. J., Lu, W., Weybourne, E. & Warne, J. M. Arginine vasotocin a key hormone in fish physiology and behaviour: a review with insights from mammalian models. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 147, 9–16 (2006).

Bedecarrats, G. Y., O’Neill, F. H., Norwitz, E. R., Kaiser, U. B. & Teixeira, J. Regulation of gonadotropin gene expression by Mullerian inhibiting substance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100, 9348–9353 (2003).

Garrel, G. et al. Anti-Müllerian hormone: a new actor of sexual dimorphism in pituitary gonadotrope activity before puberty. Sci. Rep. 6, 23790 (2016).

Delaunay, F., Thisse, C., Marchand, O., Laudet, V. & Thisse, B. An inherited functional circadian clock in zebrafish embryos. Science 289, 297–300 (2000).

Laranjeiro, R. et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p20 controls circadian cell-cycle timing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110, 6835–6840 (2013).

Wang, M., Zhong, Z., Zhong, Y., Zhang, W. & Wang, H. The zebrafish period2 protein positively regulates the circadian clock through mediation of retinoic acid receptor (RAR)-related orphan receptor alpha (Roralpha). J. Biol. Chem. 290, 4367–4382 (2015).