Abstract

The emerging tropical cyclone (TC)-blackout-heatwave compound risk under climate change is not well understood. In this study, we employ projections of TCs, sea level rise, and heatwaves, in conjunction with power system resilience modeling, to evaluate historical and future TC-blackout-heatwave compound risk in Louisiana, US. We find that the return period for a compound event comparable to Hurricane Ida (2021), with approximately 35 million customer hours of simultaneous power outage and heatwave exposure in Louisiana, is around 278 years in the historical climate of 1980–2005. Under the SSP5-8.5 emissions scenario, this return period is projected to decrease to 16.2 years by 2070–2100, a ~17 times reduction. Under the SSP2-4.5 scenario, it decreases to 23.1 years, representing a ~12 times reduction. Heatwave intensification is the primary driver of this increased risk, reducing the return period by approximately 5 times under SSP5-8.5 and 3 times under SSP2-4.5. Increased TC activity is the second driver, reducing the return period by 40% and 34% under the respective scenarios. These findings enhance our understanding of compound climate hazards and inform climate adaptation strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In August 2021, Hurricane Ida, a Category 4 storm, struck Louisiana with intense winds, heavy rainfall, and storm surges, resulting in widespread flooding and damage to the state’s infrastructure systems. Subsequent to the hurricane’s landfall, the state experienced a loss of ~200 million customer hours of electricity, affecting roughly 2.15 million customers for an average power outage duration of 96 h. Data from the United States (U.S.) Department of Energy reveals that Hurricane Ida caused the most extensive power outage in Louisiana’s history, largely surpassing Hurricane Katrina (Category 5; 2005) and Hurricane Laura (Category 4; 2020), which led to losses of approximately 140 million and 100 million customer hours of electricity, respectively1,2,3.

Furthermore, a prolonged heatwave occurred in the aftermath of Hurricane Ida, particularly affecting households that lost power and thus had no air conditioning (3; 93% of Louisiana households used air conditioning in 2020 corresponding to ref. 4). Consequently, Louisiana residents experienced a total of 35 million customer hours of compound blackout-heatwave risk (with a heat index surpassing 37.8 °C/100 °F; 5). Customers exposed to the compound hazard endured an average of approximately 98 h of heatwave conditions5. Prolonged heat exposure can cause hospitalization and mortality risks6, especially among vulnerable populations7. Understanding how often Ida-like compound blackout-heatwave events may occur is critical for the development of risk mitigation strategies for populations vulnerable to hurricanes.

A “compound climate event” can result in large impacts due to the combination of climate drivers and hazards such as floods, wildfires, heatwaves, and droughts8. Traditional risk assessment methods typically consider one hazard at a time, potentially leading to an underestimation of risk, since the physical drivers causing extreme events may exhibit spatial and/or temporal dependencies and interact to exacerbate the overall impact. Hurricanes or more generally tropical cyclones (TCs), as drivers of extreme wind, rainfall, and storm surge, inherently lead to compound impacts on coastal regions9 and are responsible for nine of the ten largest power outages in the United States over a recent two-decade period10. While extreme winds are the primary source of damage to power systems, the presence of storm surges and heavy rainfall resulted in extensive flood inundation during Hurricane Ida, which caused additional physical damage and hindered power system resilience as repair crews were unable to access affected areas2. In addition, sea-level rise (SLR) may intensify coastal flood inundation by extending and prolonging the flood coverage, further exacerbating power system damage and delaying recovery operations.

Due to the seasonal peak of intense heat being ahead of that of major TCs, TC-heatwave compound events have so far been rare worldwide11. However, a previous study12 found that for Harris County (a portion of Houston situated on higher ground and affected by hurricane winds), Texas (TX), the percentage of residents experiencing 5-day TC-blackout-heatwave compound hazard conditions could increase by a factor as large as 23 over the course of the 21st century under the high emissions scenario RCP8.5. Also, in recent years, TC-heatwave compound events have happened in the Gulf Coast region. Hurricane Ida may represent the first hurricane landfall on the mainland United States associated with a long-lasting (i.e., multi-day), large-scale blackout-heatwave compound hazard (during Hurricane Laura the state-average heat index was also high but did not reach the threshold of 37.8 °C/100 °F). During Hurricane Ida and Laura, at least eleven and eight Louisianans, respectively, died of heat-related illnesses1,13. Investigating this emerging compound threat, enhanced by climate change, will contribute to our knowledge of and adaptation to compound climate hazards.

In this study, we integrate hazard projection and power system analysis to examine TC-blackout-heatwave compound risk for Louisiana over the 21st century under the combined influence of SLR and changes in heatwave and storm climatology. We highlight the change in the return period/recurrence interval of Ida-like compound events from the historical to future climates. We further quantify the relative importance of the change in various climatological variables (i.e., heat stress, sea level, storm frequency, storm intensity) in driving the changes in the compound risk.

Our framework is an extension of the previous study in ref. 12 to incorporate multiple hazards, including storm surge, rainfall, and SLR, in addition to wind and heatwave, to more comprehensively model TC-blackout-heatwave compound risk, for the entire State of Louisiana under various climate conditions. Specifically, we combine projections of heatwaves14, TC hazards (including wind, storm surge, and rainfall15), and SLR16,17,18, driven by CMIP6 GCMs14 under a moderate (Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 2–4.5) and a high (SSP5-8.5) emissions scenarios, to assess both a likely scenario and an upper bound of the risk. We generate a large number of compound hazard events (~30,000 stochastic sequences) based on the projections for historical (1980–2005) and future (2081–2100) climates to estimate how hazard probabilities may change over the 21st century (Methods). Then we utilize a physics-based power outage and restoration model for Louisiana to simulate wind/surge/rainfall-induced power system failure and recovery for each hazard event, to estimate the TC-blackout-heatwave compound risk. In doing so, we extend the existing wind-impact-only simulation method (county level12,19) to a wind-rainfall-surge coupled framework for power damage and recovery process modeling to consider a larger study area including coastal regions (state level; Methods). Considering the uncertainty surrounding the impact of climate change on the frequency of TCs making landfall along the Gulf Coast, we assume a constant TC frequency but also assess the sensitivity of the compound risk to TC frequency projection. To focus on the impact of climate change, we assume that the power system, population distribution, and recovery plans in the study region will remain unchanged. However, we assume that the coastal levees will be elevated following design guidance, as this enhancement may be considered necessary to prevent the region from frequent inundation due to SLR (“Methods”).

Results

Historical cases

We first examine power outage simulations of the historical cases of Hurricanes Ida and Laura, which are the two major events over the last decade that caused widespread power disruptions in Louisiana1. Ida devastated the eastern half of Louisiana, which is more densely populated (including the city of New Orleans), whereas Laura grazed the western side. Ida destroyed 31,000 poles (reported by local utility company Entergy20) that carry lower-voltage distribution lines in the neighborhoods, twice as many as those in Hurricane Laura (14,000 poles) and Katrina (2005; 17,000 poles).

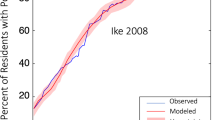

As shown in Fig. 1a and b, the model’s estimates for the overall impact of Hurricanes Ida and Laura on Louisiana compare relatively well with the observation. Hurricane Ida led to 47% (48% in simulation) of customers being out of power within the first 24 h, and it took ~10 days (11 days in simulation) for 90% of customers to restore power. Meanwhile, up to 60% of Louisiana customers were under heatwave conditions within 6 days after Hurricane Ida’s landfall. About 42% independent customers experienced compound power outage and heatwave hazards for at least one day after the hurricane’s landfall, and the percentage of customers experiencing the compound hazard surpassed 15% during a period of time (see Supplementary Fig. 1). Hurricane Laura led to 27% (29% in simulation) of customers being out of electricity initially and it took ~6 days (8 days in simulation) for 90% of customers to restore power (see Supplementary Fig. 2 for spatial distribution).

a Ida and b Laura. The red curve shows median values, with 5% to 95% quantile range shown by shade and the blue curve shows the observation. The yellow curve in (a) shows the percent of customers impacted by heatwaves (value reads the right axis). c Comparison of observed and simulated spatial distribution of power outage for Hurricane Ida. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To measure the overall severity of the blackout associated with each TC, we compute the cumulative interruption hours throughout Louisiana (the total of all customers’ power outage duration), a commonly used metric in evaluating power system reliability21. The model simulation estimates in total 189 (156–242; ±3 standard deviations) million power interruption hours for Ida, which is consistent with the observed 206 million hours, and 110 (77–153) million power interruption hours for Laura, which compares relatively well with the observed 99 million interruption hours. As a comparison, Hurricane Katrina led to ~140 million power interruption hours. The model estimation for the spatial and temporal distribution of power outage also correlates well with observations (the average relative error is <10% between the modeled and observed county-level power outage), as illustrated in Fig. 1c for the power outages at 24 h, 5 days, and 8 days after landfall at the county level for Hurricane Ida.

Blackout and compound hazards

Integrating power outage and recovery modeling with projections of future TC, SLR, and heatwaves, we examine the TC-induced blackout-heatwave compound risk in Louisiana. We generate 10,000 simulations of synthetic hazard events for each of the historical (1980–2005) and future (2081–2100) SSP5-8.5 and SSP2-4.5 scenarios. Each stochastic simulation includes a continuous 20-year sequence of TC occurrences, along with the physical simulation of TC tracks, wind speeds, rainfall amounts, storm surge levels, and heatwaves. We track each customer’s exposure (i.e., duration) to blackout or compound blackout-heatwave hazard in the power outage and recovery modeling process for each synthetic hazard event. Then, we integrate the customer-level results to obtain state-level statistics and estimate the return periods (i.e., reciprocal of annual exceedance probability) of event total interruption hours for the historical and future climates. As demonstrated by the substantial shift of the return period curves (Fig. 2), the power outage risk will increase dramatically from the historical to the future climate. Specifically, the historical return period of a power outage of 206 million customer hours, as in Hurricane Ida, is 64 years (Table 1). The return period of a power outage like Hurricane Ida’s total outage is projected to be 35.8 years in the future under the SSP5-8.5 emissions scenario, compared to 38.2 years under SSP2-4.5. The total power outage for an event with Ida’s historical return period of 64 years is approximately 413 million customer hours under SSP5-8.5 and 265 million customer hours under SSP2-4.5. The return period of a TC-blackout-heatwave compound hazard of 35 million customer hours, as in Hurricane Ida, is 278 years in the historical climate. This return period is expected to decrease in the future climate to 16.2 years under SSP5-8.5 (~17× reduction) and 23.1 years under SSP2-4.5 (~12× reduction). A compound hazard event with Ida’s historical return period of 278 years is projected to cause about 435 million customer hours of impact under SSP5-8.5 and 138 million under SSP2-4.5. Such an event would induce an average blackout-heatwave compound hazard duration of approximately 8.8 days (SSP5-8.5) or 2.8 days (SSP2-4.5) for each of Louisiana’s 2.13 million customers.

a interruption hours under power outage, b interruption hours under blackout-heatwave compound hazard. The red curve shows median values for SSP5-8.5 for the future climate, with the 5–95% quantile range shown by shade, the yellow curve represents SSP2-4.5 for the future, and the blue for the historical climate. The dashed lines highlight Hurricane Ida’s power outage and compound risk levels. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The power outage level under SSP2-4.5 is similar to that under SSP5-8.5 at Ida’s return period or shorter, although the power outage level becomes higher in SSP5-8.5 at longer return periods (Fig. 2a), due to higher extreme TC hazards and SLR in SSP5-8.5. The difference between the two emissions scenarios is larger for the compound risk. Specifically, the return period of the compound hazard impact at Ida’s level under SSP5-8.5 is slightly shorter than that under SSP2-4.5, and the return period of larger compound impacts becomes dramatically shorter under SSP5 8.5 (Fig. 2b), due to combined effects of larger increases in extreme heatwaves, TC hazards, and the sea level under SSP5-8.5. For example, the return period of extremely severe compound events, such as those with triple the impact of Hurricane Ida (i.e., 100 million customer-hours of compound hazards), is expected to be 2.5 times longer under SSP2-4.5 compared to SSP5-8.5. However, for less severe events, such as those with a third of Ida’s impact (i.e., 10 million customer-hours of compound hazards), we do not find a statistically significant difference in the event return period/frequency between the two emissions scenarios. These findings suggest that the combined effects of global warming and increasing hurricane intensity amplify the risk of the most extreme compound events. Nonetheless, the moderate emission scenario may still lead to a similar increase of frequency for events of Ida’s impact magnitude, compared to the high emissions scenario.

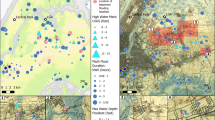

Spatial pattern of compound risk

To investigate the spatial distribution of the compound risk, we estimate the county-average compound hazard interruption days for each synthetic hazard event. Figure 3 shows the compound hazard interruption days with Ida’s historical return period of 278 years for each county in Louisiana in the historical and future climates. The coastal counties face a greater compound risk than inland counties for both historical and future climates (Fig. 3a–c). For example, the counties with an average compound hazard impact larger than 20 days in the future climates are mostly coastal counties. Coastal counties often face a greater compound risk since hurricane winds reach peak strength before the storm makes landfall, and storms weaken as they move inland, causing less damage to the inland power infrastructure. Moreover, the floods induced by storm surge and heavy rainfall can severely damage coastal power sectors. The flooding also hampers the recovery efforts of local contractors by submerging electrical components in water and obstructing local traffic and logistics with debris.

a Historical average interruption, b future SSP5-8.5 average interruption, and c future SSP2-4.5 average interruption, for each county in Louisiana for a compound hazard event with a 278-year return period. d Distribution of affected Orleans Parish customers’ compound hazard duration under a 278-year event. The solid lines show the percentage of affected customers experiencing compound hazard up to a certain temporal length in the historical and future climates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The general spatial disparities in compound risks are also substantial and will increase with climate change. For example, in the historical climate, the most impacted county may face on average a 1.8-day compound hazard with the return period of 278 years, and the least impacted county does not face any compound risk (Fig. 3a). In the future, under the SSP5-8.5 scenario, the county with the greatest impact may face an average of 12.7 days of compound hazard exposure for an event with the return period of 278 years. Under the SSP2-4.5 scenario, this average is 3.1 days. Conversely, the least impacted area is projected to experience only 1.1 days under SSP5-8.5 and 0.1 days under SSP2-4.5 (Fig. 3b–c). To assess the spatial disparity in the compound risk, we use the Gini coefficient22, a statistical measure of inequality commonly applied to income, wealth, or consumption distribution. The coefficient ranges from 0 (perfect equality, where all counties face the same average compound hazard duration) to 1 (full inequality, where only one county faces the hazard). In the historical climate, the Gini coefficient is approximately 0.312. However, under future scenarios, it increases to 0.632 for SSP5-8.5 and 0.411 for SSP2-4.5. These results suggest that intensifying hurricane hazards disproportionally impact coastal regions and vulnerable communities distant from substations, and thus, climate change is likely to exacerbate existing disparities and inequalities in TC-blackout-heatwave compound risks across Louisiana.

We also examine the distribution of compound hazard durations for residents in densely populated counties. Figure 3d illustrates the distribution of compound hazard interruption days for affected customers in Orleans Parish, for a 278-year compound event. In the historical climate, only 3% of affected customers may experience a compound hazard lasting more than 120 h (5 days). In the future, under the SSP5-8.5 scenario, nearly 60% of affected customers are projected to face a compound hazard exceeding 120 h, with nearly 30% experiencing durations longer than 240 h (10 days) and 10% encountering durations exceeding 360 h (15 days). Under SSP2-4.5, 20% of affected customers may face compound hazards exceeding 120 h, 3% may experience durations longer than 240 h, and no customers are expected to encounter durations beyond 360 hours. Hence, climate change not only increases the average compound hazard impact but also intensifies the tail risk that vulnerable residents may encounter, especially under the high emissions scenario.

Drivers of changes in compound risk

The change in the compound risk is driven by the change in three climate factors: 1) heatwaves (heat index) 2) TC climatology, and 3) the sea level. As we assume that TC frequency remains unchanged in the future, the changes in TC climatology include changes in TC characteristics, particularly intensity (which drives changes in wind, storm tide, and rainfall). To determine the relative effect of the changes in these factors, we estimate the changes in the compound risk due to changes in temperature, SLR, and TC climatology, respectively, by adjusting each variable to its future value or distribution and calculating the resulting return period of Ida’s compound hazard (i.e., 35 million customer hours of simultaneous power outage and heatwave impact), as shown in Fig. 4a.

a. Relative impact of each climate change factor assuming a consistent TC frequency. b Sensitivity to TC frequency change. Note that the combined impact of all climate factors on Ida’s compound hazard return period is highly non-linear, and thus, the sum of the relative impact of individual factors does not equal the total impact. Data are presented as the mean value with 10–90% quantile. 10,000 stochastic samples of storm sequences for each climate case are used to derive the statistics. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

As discussed earlier, when all climate change factors are considered, Ida’s return period is projected to decrease from 278 years in the historical climate to 16.2 years under SSP5-8.5 and 23.1 years under SSP2-4.5 in the future climate. Among these factors, changes in heatwaves are the largest contributors to this reduction. Due to heatwave changes alone, Ida’s return period would drop to 47.6 years under SSP5-8.5 and 84.3 years under SSP2-4.5, representing approximately a five-fold and three-fold decrease, respectively. This substantial impact is driven by dramatic increases in temperature and humidity: the annual number of heatwave days (above 37.8 °C) is expected to rise eightfold from the historical climate to the future climate, based on the ensemble average of the six GCMs for the study region.

Changes in TC characteristics, especially intensity also contribute to the reduction, decreasing Ida’s return period to 167.8 years under SSP5-8.5 and 185.2 years under SSP2-4.5. By comparison, the impact of SLR is relatively small, reducing Ida’s return period to 251.2 years under SSP5-8.5 and 263.3 years under SSP2-4.5. SLR appears to have a relatively low impact because we assume the levees along the coast will be elevated. Also, the impact of SLR is limited to coastal regions, and it is averaged out when the compound hazard impact is calculated for the entire state. The contribution of the various climatological drivers to future compound risk is consistent across the two different emission scenarios.

Considering that the projection of TC frequency is subject to considerable uncertainty23,24, we assumed a constant TC frequency in above analyses. Here, we investigate the sensitivity of the estimated compound risk to the projection of TC frequency change. In one scenario, we apply the TC frequency in the applied TC model15, which projects relatively high increases in TC frequency in the future climates. Under SSP5-8.5, Ida’s return period decreases to 7.9 years, and under SSP2-4.5, it decreases to 15.2 years, compared to 16.2 years (SSP5-8.5) and 23.1 years (SSP2-4.5) when accounting for all climate change factors except TC frequency changes. In another scenario, we consider a 30% decrease in TC frequency, the lower bound of TC frequency projections ensembled in ref. 24. In this case, Ida’s return period becomes 28.4 years under SSP5-8.5 and 40.6 years under SSP2-4.5. While longer than the projections with increased or constant TC frequency, these return periods represent a similarly dramatic decrease from 278 years in the historical climate. This sensitivity test indicates the relatively small impact of TC frequency change compared to the combined effects of other climate change factors.

Discussion

This analysis highlights the substantial increase in the frequency of Ida-level extreme power outage-heatwave compound hazards over time, resulting from the combined effect of temperature increase, SLR, and storm climatology change under climate change. Linear interpolation suggests that Hurricane Ida’s return period has decreased from 278 years around the end of the last century to 225.6 years under SSP5-8.5 and 227.0 years under SSP2-4.5 in the 2020 s, representing approximately a 19% reduction over the past two decades. This real-life observation of an emerging climate compound hazard motivates further research on projecting future compound climate risks and developing strategies to mitigate climate risks for various regions around the world.

When examining the impact of various climate scenarios, such as the high emission scenario SSP5-8.5 and the moderate emission scenario SSP2-4.5, it appears that the risk associated with Ida-scale compound hazard events may not exhibit substantial difference. This result indicates that utility companies urgently need to prepare for the compound events to prevent major impacts, regardless of whether a moderate or high emissions scenario is considered. On the other hand, the frequency of larger compound impacts is expected to be significantly lower under the moderate emissions scenario. Moreover, the duration of interruptions caused by compound hazards will also be reduced with moderate emissions. This result highlights the importance of strengthening climate change mitigation policy to reduce the impact of extreme climate hazards.

We do not consider the potential change in the power grid or its operation in the future. In the future, localized solutions, including backup generators and solar panels, can provide temporary support to residents who lose power from the main grid, thus mitigating the impacts of compound hazards25. These solutions can help reduce the exposure of vulnerable populations to the effects of power outages and extreme heat, thereby lessening the overall impact of compound hazard events. However, backup generators and solar panels may be cost-prohibitive, limiting their effectiveness in reducing heat stress. Proactive policy measures, such as subsidies or tax breaks, may be needed to make these interventions accessible and effective for vulnerable populations. Also, equipping relief centers with reliable cooling and backup power systems can further enhance emergency response capacity. Prioritizing these interventions based on estimated compound risk can guide effective resource allocations. From the main power grid design perspective, adopting effective strategies like burying distribution networks and developing distributed power systems25 can bolster the resilience of power infrastructure against extreme weather events.

We also do not consider the potential changes in demographics and human habitat. As extreme climate events become more frequent, coastal megacities are also expected to develop rapidly26,27. Encouraging climate-resilient urban design principles that prioritize green spaces, water management systems, and heat-resistant building materials can enhance cities’ resilience against compound risks28. Also, the implementation of advanced early warning systems and preparedness measures, combined with public awareness campaigns, can help minimize potential impacts on vulnerable communities29,30. Moreover, changes in population patterns, such as urbanization in low-elevation coastal zones and the concentration of populations in areas vulnerable to climate hazards, can influence the impact of compound hazards, emphasizing the need to account for these demographic shifts when devising adaptation strategies26,31.

Quantifying the reliability and resilience of infrastructure systems under the impact of future compound hazards is essential for climate change adaptation. Developing an integrated risk assessment framework that combines climatology, civil and electric engineering, urban planning, and social sciences is crucial for comprehensively understanding the interconnected nature of compound risks and their societal impacts, and the formulation of effective mitigation strategies32,33. For example, conventional statistical methods may fail to detect significant changes in compound risk, especially for the most extremes. Our analysis shows that the intensity of relatively frequent hazards may not change significantly in the future, especially under moderate emissions scenarios. However, if such a conclusion for frequent, observable events is statistically extrapolated to that for extreme events, we may transform events like Ida, which could have been foreseen and prepared for, into “black swan” events—unpredictable extreme disasters with unimaginable losses. Only physics-based modeling integrating climate and hazards projection and infrastructure/social system analysis may provide reliable estimates of future risks. This multidisciplinary perspective is essential for capturing the complex interactions between different hazards and their cascading effects on infrastructure systems and society as a whole, ultimately enabling the development of robust and resilient strategies to mitigate the impacts of compound hazards. Also, given various uncertainties in the projections of climate change and social development, there is a need for continuous refinement and updating of risk analysis techniques as improved modeling approaches and new data become available. By adopting a comprehensive approach that integrates various disciplines and continuously enhances our understanding of compound risks, we can work towards developing effective adaptation strategies for a sustainable future in the face of a changing climate.

Methods

Synthetic TC, storm surge, tide, and rainfall modeling

We use the synthetic TC hazard dataset generated in ref. 15 for the North Atlantic basin and select the TC tracks passing within 300 km of Louisiana, with a maximum wind speed of at least 22 m/s. The dataset contains synthetic TC tracks generated with the statistical-deterministic TC model34, which has been applied to TC hazard assessment9,35,36. The synthetic TC tracks for the historical period (between 1980 and 2005) were generated based on the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) reanalysis. The dataset also contains bias-corrected and weighted-average climate projections of TCs for the future period (2070 to 2100) under Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) emissions scenarios, SSP5 8.5 and SSP2 4.5. The dataset was generated based on projections from six CIMP6 models (selected given data availability and following previous studies): Canadian Earth System Model (CanESM5), Centre National de Recherches Météorologiques Climate Model (CNRM-CM6-1), UK Earth System Model (UKESM1-0-LL), EC-Earth3, IPSL-CM6A-LR (Institut Pierre-Simon Laplace Climate Model), and Model for Interdisciplinary Research on Climate (MIROC6). The TC storm tides were modeled in ref. 15 using the Advanced Circulation (ADCIRC) hydrodynamic model37,38. We extract peak storm tides at nodes (~1 km resolution) along the coastline of Louisiana for each TC and match these to the county level. The rain fields were simulated in ref. 15 for each synthetic TC using the physics-based Tropical Cyclone Rainfall (TCR) model39. We apply area-averaged TCR estimates at the county level, and we employ the maximum 24 h rainfall accumulation from each storm event, since the 24-hour storm duration is often utilized for rainfall risk assessment39,40.

To perform sequential risk analysis, we generate 10,000 stochastic samples of storm sequences for each of the historical and future climate conditions. These samples were derived by sampling storms (according to a Poisson process with a rate as the TC annual frequency) and their associated hazards from the TC hazard datasets described above. Each stochastic sequence consists of 20 consecutive years of TC activity. For the primary analysis in this study, we maintain a constant TC frequency in the future climate. For the sensitivity analysis, we consider the increased TC frequency projected by the statistical-deterministic TC model in ref. 15 and the decreased TC frequency by up to 30% projected by a range of climate models ensembled in ref. 24.

For each sampled storm, we generate the spatial-temporal wind field, employing the classical Holland wind profile41 and accounting for the effects of surface friction and large-scale background wind following ref. 42, and converting one-minute mean winds to 3 s wind gusts using gust factors43. We estimate the coastal flood area by comparing the height of peak storm tide (if over levee height) to the ground surface elevation specified by the USGS 30 m DEM44, assuming that areas would be inundated when the storm tide exceeds the ground elevation.

In Louisiana, the actual seawall heights vary largely along the coastline, ranging from 2 to 5 meters and often changing over short distances. Due to the difficulty in acquiring the precise data, our simulations do not incorporate partially available measurements45,46,47. We assigned the current seawall level based on estimated 100-year flood level (estimated in ref. 15) for each coastal county in Louisiana, according to the typical design guidance. For example, the 100-year flood level for New Orleans is approximately 3.4 meters above the North American Vertical Datum of 1988 (NAVD 88)9. This approximation introduces a degree of inaccuracy into our flood modeling. Acknowledging this limitation, we subsequently focused on binary flood data—whether a flood occurs or not—when developing our power system damage and recovery models. We observe that the occurrence of flooding is a critical factor that largely hinders the restoration efforts of the power system in coastal counties. However, the inundation depth of the flooding appears to have a less substantial impact. When compared to the areas affected by the TC’s wind and rainfall, the storm surge flooded regions are generally smaller. Therefore, the majority of the structural damage to the power system may not be caused by coastal flooding.

The future coastal levee plan is uncertain. In the future climate simulations, we assume the coastal levee will be elevated by ~ 2 m, based on the historical 100-year return level plus one percentile SLR. This design strategy is commonly used by governmental agencies to plan the seawall height, and it is within the framework proposed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for the New Orleans Region, Lafayette, and Lake Charles47. A sensitivity test was performed on future compound risks given different elevations of the coastal levee from 0-3 meters above the current level. If the levee were not elevated, the surge impact on the compound risk would be substantially higher than estimated in this study. On the other hand, when the levee is elevated by higher than 2 m, the estimated compound risk is not sensitive to the variation of the assumed levee increment up to the test case of 3 meters (see Supplementary Fig. 3). The generated wind, rainfall, and coastal flood conditions from each sampled storm drive the power grid outage and recovery analysis.

Heatwave projections

Following ref. 11, the daily HI is determined as a function of daily maximum near-surface (2 m) air temperature, daily mean specific humidity, and daily mean surface pressure. To maintain consistency with the TC simulation, we obtain these data for Louisiana from the NCEP reanalysis and the six GCMs stated above during and after landfall for each sampled synthetic storm (each synthetic storm is associated with a climatological time of occurrence and development). The future HI projected by the GCM is bias-corrected12 by adding the difference between the NCEP reanalysis and the GCM-estimated historical HI. According to the historical analysis in ref. 11, the HI will drop upon TC landfall and will recover to the ambient average within around ten days. To account for this dependence between TCs and heatwaves, we add the composite of the impact of TC passage to the meteorological variables used to calculate the HI, where the composite impact is estimated based on historical data (Fig. 3a in ref. 11).

Sea level rise projections

We employ sea-level projections produced by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Sixth Assessment Report16,18 (AR6) using the Framework for Assessing Changes To Sea-level17 (FACTS). Localized probabilistic SLR projections under the SSP5-8.5 and SSP2-4.5 emission scenarios with “medium confidence” are incorporated in this analysis (there are two confidence levels in the datasets, which are low and medium levels). The local sea level projection takes into account ground uplift or subsidence, oceanographic effects, and spatially variable responses of the geoid and the lithosphere to shrinking land ice. The projection of SLR was developed for tide-gauge stations. For each TC sequence realization, we first sample a near-by SLR time series (a realization) from the projection for each county. Then, we add the SLR to the storm tide level at each time point for each county.

Power outage and recovery model

We apply a physics-based power system model, which explicitly simulates component-level damage to predict the total power outage, accounting for the effects of future evolving factors, e.g., climate change, infrastructure upgrade, and utility maintenance. The physics-driven modeling of the power system allows us to better understand the impact of climate change and effectiveness of risk mitigation measures compared to if we used purely data-driven models48,49.

Specifically, we extend the power grid outage and recovery model developed by refs. 12,19 to simulate TC impact on the electric power system in Louisiana (see the methodology diagram in Supplementary Fig. 4, power topology in Louisiana in Supplementary Figs. 5, 6, and electric utility service areas in Louisiana in Louisiana Public Service Commission50). The power grid failure model first applies probabilistic fragility functions to estimate the damage states of five main vulnerable component types of the power network: transmission substations, transmission lines, distribution nodes, distribution lines, and local distribution circuits. Component failures alter the power grid topology and may separate the power grid into disconnected sub-grids. A direct-current (DC) flow simulation is then performed to capture the power availability in each sub-grid (similar to approaches in refs. 51,52,53,54). The power system is open and connects with systems outside the study area via transmission lines; the performance of the power grid outside the study area is assumed to be under normal operation.

The fragility curves in refs. 12,19 only considered the wind damage. Here we extend the fragility functions to consider the effects of coastal floods and rainfall. For example, the probability of failure of a substation given specific wind, rainfall, and coastal flood levels is estimated based on a log-normal fragility function as Eq. (1):

where hazard (H/h) is considered as a linear combination of wind speed (w), rainfall amount (r), and flood condition (f, flooded or not; Boolean variable) with two parameters α and β. With the shape (σi) and location (μi) parameters, the log-normal distribution describes the probability of potential damage (D) in each of four states (di), i.e., i = {low, moderate, severe, complete} damage. Fragility function refers to the latent distribution of a component’s ability to withstand outer forces (hazard). Some components may not withstand any force at all, while others can withstand very large outer force. Given a certain outer force, the probability of damage to the component is equal to the integral of fragility from 0 to that force level, i.e., the probability that the strength of the component is lower than outer force. The fragility functions for other components (support structures, distribution nodes, poles, conductors, and circuits) are similarly modeled with exponential, logistic, or uniform distributions. These fragility functions are similar to those in refs. 12,19 except that the effects of rainfall and flood are incorporated. The parameters are estimated by the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method to minimize the mean squared error between simulated and observed county-level power outages1 under Hurricanes Laura and Ida with equal weight.

The recovery model, developed based on emergency response plans and operational data, applies estimated recovery resources based on a priority-oriented strategy to repair damaged transmission substations, transmission lines, and critical facilities vital to public safety, health, and welfare before local distribution networks12,19. Debris should be removed before utilities become able to reinstate the power system. This debris-cleaning time is sampled from a uniform distribution between 48 and 72 h (estimated from utility reports)2. We also account for that, without structural failure of the distribution system, residents may turn on the main power switch themselves 24–48 h after being flooded55.

There is a chance that TCs will make landfall in sequence, and the second TC comes before the damage caused by the first TC is fully recovered56. We account for this temporal compounding effect in our power system outage and recovery analysis. For each sampled sequential hazard time series, the initial state of the power system when a TC arrives is set based on the condition of the restoration state from the previous TC. If the power system is indeed not fully recovered from the previous TC impact, the emergency response plans following the second TC are also adjusted considering the recovery process for the first TC. Specifically, the response plans will re-evaluate and prioritize the restoration tasks and redirect the repair efforts based on this updated priority list.

The power grid outage and recovery models were calibrated (to determine the model parameters) for the study area using observed power outage data for Hurricane Ida and Laura using simulated wind and observed rainfall57 and flood58. The same wind field modeling method applied to the synthetic storms is used for these two historical storms with storm characteristics (i.e., track, intensity, and size) taken from the extended best track data59.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The transmission network data is from Homeland Infrastructure Foundation Level Database (HIFLD). The distribution network data is from Louisiana Public Service Commission (LPSC). The hurricane hazard data were obtained from Ref. 15. The generated power system failure statistics are deposited to Github and Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15012708). Source Data for figures are provided with this paper. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The codes for simulating power system failures are deposited to Github and Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15012708).

References

Hurricane Response Record, Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Emergency Response, U.S. Department of Energy (2021).

Hurricane Ida Power Restoration, Utility Report, Entergy Link: https://www.entergynewsroom.com/article/entergy-system-hurricane-ida-update-9-2-21-9-m/ (Last visited: 11/25/2024) (2021).

Nicholas Bogel-Burroughs and Katy Reckdahl. The Greatest Killer in New Orleans Wasn’t the Hurricane. It Was the Heat. New York Times (2021).

U.S. Energy Information Administration. State air conditioning. Retrieved from https://www.eia.gov/consumption/residential/data/2020/state/pdf/State%20Air%20Conditioning.pdf (2020).

National Weather Service, Heat Watch vs. Warning Link: https://www.weather.gov/news/250310-heat-hazard (Last visited 4/08/2025) (2024).

Ebi, K. L. et al. Hot weather and heat extremes: health risks. Lancet 398, 698–708 (2021).

Lee, D. H. K. Seventy-five years of searching for a Heat Index. Environ. Res. 22, 331–356 (1980).

Zscheischler, J. et al. Future climate risk from compound events. Nat. Clim. Chang. 8, 469–477 (2018).

Gori, A., Lin, N., Xi, D. & Emanuel, K. Tropical cyclone climatology change greatly exacerbates US extreme rainfall–surge hazard. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 171–178 (2022).

Houser, T. & Marsters, P. The world’s second largest blackout. 385 (Rhodium Group, 2018).

Matthews, T., Wilby, R. L. & Murphy, C. An emerging tropical cyclone–deadly heat compound hazard. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9, 602–606 (2019).

Feng, K., Ouyang, M. & Lin, N. Tropical cyclone-blackout-heatwave compound hazard resilience in a changing climate. Nat. Commun. 13, 4421 (2022).

Louisiana Department of Health verifies one additional hurricane-related death, bringing toll to 27. Louisiana Dep. Heal. Published online Sept 9. Available at: https://ldh.la.gov/index.cfm/newsroom/detail/5761 (2020) Accessed Oct 21, 2020).

O’Neill, B. C. et al. The scenario model intercomparison project (ScenarioMIP) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3461–3482 (2016).

Xi, D., Lin, N. & Gori, A. Increasing sequential tropical cyclone hazards along the US East and Gulf Coasts. Nat. Clim. Chang. 13, 258–265 (2023).

Baylor Fox-Kemper et al. Ocean, cryosphere and sea level change. in Climate Change 2021–The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (ed. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)) 1211–1362 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.011.

Kopp, R. E. et al. The framework for assessing changes to sea-level (FACTS) v1.0: a platform for characterizing parametric and structural uncertainty in future global, relative, and extreme sea-level change. Geosci. Model Dev. 16, 7461–7489 (2023).

Garner, G. G. et al. IPCC AR6 Sea Level Projections. Version 20210809 (2021).

Ouyang, M. & Duenas-Osorio, L. Multi-dimensional hurricane resilience assessment of electric power systems. Struct. Saf. 48, 15–24 (2014).

Entergy, Restoration Times for Louisiana, including Hardest Hit Areas Link: https://www.entergynewsroom.com/article/entergy-louisiana-ida-update-9-20-2021/ (Last Visited: 4/08/2025) (2021).

U.S. Energy Information Administration, Annual Electric Power Industry Report, Form EIA-861 detailed data files (2021).

Gastwirth, J.L. The estimation of the Lorenz curve and Gini index. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 306–316 (1972).

Sobel, A. H. et al. Tropical cyclone frequency. Earth’s Future 9, e2021EF002275 (2021).

Knutson, T. et al. Tropical cyclones and climate change assessment: part II: projected response to anthropogenic warming. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 101, E303–E322 (2020).

Bennett, J. A. et al. Extending energy system modelling to include extreme weather risks and application to hurricane events in Puerto Rico. Nat. Energy 6, 240–249 (2021).

Hauer, M. E. Migration induced by sea-level rise could reshape the US population landscape. Nat. Clim. Chang. 7, 321 (2017).

Feng, K., Lin, N., Xian, S. & Chester, M. V. Can we evacuate from hurricanes with electric vehicles? Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ. 86, 102458 (2020).

Gill, S. E., Handley, J. F., Ennos, A. R. & Pauleit, S. Adapting cities for climate change: the role of the green infrastructure. Built Environ. 33, 115–133 (2007).

Wamsler, C., Brink, E. & Rantala, O. Climate change, adaptation, and formal education: the role of schooling for increasing societies’ adaptive capacities in El Salvador and Brazil. Ecol. Soc. 17, 2 (2012).

Birkmann, J. & von Teichman, K. Integrating disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation: key challenges—scales, knowledge, and norms. Sustain. Sci. 5, 171–184 (2010).

Seto, K. C., Güneralp, B. & Hutyra, L. R. Global forecasts of urban expansion to 2030 and direct impacts on biodiversity and carbon pools. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 16083–16088 (2012).

DT Cohen, 60 million live in the path of hurricanes. U.S. census bureau. Link: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2018/08/coastal-county-population-rises.html (Last visited 4/08/2025) (2018).

Xu, L. et al. Resilience of renewable power systems under climate risks. Nat. Rev. Electr. Eng. 1, 53–66 (2024).

Emanuel, K., Ravela, S., Vivant, E. & Risi, C. A statistical deterministic approach to Hurricane Risk Assessment. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 87, S1–S5 (2006).

Marsooli, R., Lin, N., Emanuel, K. & Feng, K. Climate change exacerbates hurricane flood hazards along US Atlantic and Gulf Coasts in spatially varying patterns. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–9 (2019).

Lin, N., Emanuel, K., Oppenheimer, M. & Vanmarcke, E. Physically based assessment of hurricane surge threat under climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2, 462–467 (2012).

Luettich, R.A., Westerink, J.J. & Scheffner, N.W. “ADCIRC: an advanced three-dimensional circulation model for shelves, coasts, and estuaries. Report 1, Theory and methodology of ADCIRC-2DD1 and ADCIRC-3DL.” (1992).

Westerink, J.J., Luettich, R.A., Blain, C.A. & Scheffner, N.W. “ADCIRC: An advanced three-dimensional circulation model for shelves, coasts, and estuaries. Report 2: User’s Manual for ADCIRC-2DDI.” (1992).

Xi, D., Lin, N. & Smith, J. Evaluation of a physics-based tropical cyclone rainfall model for risk assessment. J. Hydrometeorol. 21, 2197–2218 (2020).

Fagnant, C., Gori, A., Ensor, K.B., Sebastian, A. & Bedient, P.B. Characterizing spatiotemporal trends in extreme precipitation across the Southern Texas Coast. Nat. Hazards 104, 1597–1621 (2020).

Emanuel, K. Assessing the present and future probability of Hurricane Harvey’s rainfall. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 12681–12684 (2017).

Holland, G. J. An analytic model of the wind and pressure profiles in hurricanes. Mon. Weather Rev. 108, 1212–1218 (1980).

Lin, N. & Chavas, D. On hurricane parametric wind and applications in storm surge modeling. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 117 (2012).

USGS (U.S. Geological Survey). Digital Elevation Model https://pubs.usgs.gov/sim/3049/ Last accessed: Mar-19-2025 (2022).

Palaseanu-Lovejoy, M., Thatcher, C. A. & Barras, J. A. Levee crest elevation profiles derived from airborne lidar-based high resolution digital elevation models in South Louisiana. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 91, 114–126 (2014).

Johnson, D. R., Fischbach, J. R. & Ortiz, D. S. Estimating surge-based flood risk with the coastal Louisiana risk assessment model. J. Coast. Res. 67, 109–126 (2013).

US Army Corps of Engineers, Hurricane & Storm Damage Risk Reduction System, New Orleans District (2021).

Nateghi, R., Guikema, S. D. & Quiring, S. M. Comparison and validation of statistical methods for predicting power outage durations in the event of hurricanes. Risk Anal. 31, 1897–1906 (2011).

Ji, C. et al. Large-scale data analysis of power grid resilience across multiple US Service Regions. Nat. Energy 1, 1–8 (2016).

Louisiana Public Service Commission Louisiana Electric Utility Service Area https://www.lpsc.louisiana.gov/Utilities_Map Last Accessed: Mar-19-25 (2025).

Yang, Y., Nishikawa, T. & Motter, A. E. Vulnerability and co-susceptibility determine the size of network cascades. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 048301 (2017).

Yang, Y., Nishikawa, T. & Motter, A. E. Small vulnerable sets determine large network cascades in power grids. Science 358, eaan3184 (2017).

Zhai, C., Chen, T. Y. J., White, A. G. & Guikema, S. D. Power outage prediction for natural hazards using synthetic power distribution systems. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 208, 107348 (2021).

Hines, P., Cotilla-Sanchez, E. & Blumsack, S. Do topological models provide good information about electricity infrastructure vulnerability? Chaos 20, 033122 (2010).

Seven Steps to Restore Power After a Flood. New Equipment Digest https://www.newequipment.com/plant-operations/article/22059483/seven-steps-to-restore-power-after-a-flood (Last accessed: Mar-12-25) (2017).

Xi D., Lin, N. Sequential landfall of tropical cyclones in the United States: from historical records to climate projections. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48 (2021).

Du, J. “NCEP/EMC 4KM Gridded Data (GRIB) Stage IV Data. Version 1.0.” UCAR/NCAR - Earth Observing Laboratory, https://doi.org/10.5065/D6PG1QDD (2011).

Dartmouth Flood Observatory. Link: https://floodobservatory.colorado.edu/ (Last Visited: 4/08/2025) (2021).

Demuth, J., DeMaria, M. & Knaff, J. A. Improvement of advanced microwave sounder unit tropical cyclone intensity and size estimation algorithms. J. Appl. Meteor. 45, 1573–1581 (2006).

Acknowledgements

K.F., N.L., A.G., D.X., and M. Oppenheimer were supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) as part of the Megalopolitan Coastal Transformation Hub (MACH) under NSF award ICER-2103754 to Princeton University, with MACH contribution number 44. K.F. was also supported by the HMEI-STEP Graduate Fellowship at Princeton University. K.F., A.G., and D.X moved during revision, and K.F. was then supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62088101), Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (Grant No.2021SHZDZX0100), Explorer Program (Grant No. 24TS1401600), and Xiaomi Foundation. M. Ouyang was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (72371109,71821001), Strategic study project of Chinese Academy of Engineering (2022-JB-02), and Project of Interdisciplinary Research Support Program in HUST (2023-32). We thank the IPCC AR6 Sea Level projection team for developing and making the sea-level rise projections available, multiple funding agencies for supporting the development of the projections, and the NASA Sea Level Change Team for developing and hosting the IPCC AR6 Sea Level Projection Tool.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The conceptualization of the project was carried out by K.F., N.L., M.O.Y., and M.O.P. The methodology was developed by K.F., N.L., A.G., D.X., and M.O.Y. The original draft of the writing was authored by K.F. and N.L., and K.F., N.L., A.G., D.X., M.O.Y., and M.O.P. reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Nadia Bloemendaal and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Feng, K., Lin, N., Gori, A. et al. Hurricane Ida’s blackout-heatwave compound risk in a changing climate. Nat Commun 16, 4533 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59737-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59737-8