Abstract

The timing, rate, and magnitude of rapid sea-level rise during Meltwater Pulse 1B (MWP-1B, ~11.45–11.1 ka) remain controversial. Robust constraints on past MWPs are crucial to future predictions of global ice sheet instability. Using 154 new and existing U/Th and calibrated 14C-AMS dates from coral, algae, and microbialites recovered during Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Expedition 325, this study reconstructs reef development and relative sea-level (RSL) rise on the Great Barrier Reef (GBR). We identify 107 in situ RSL index points while refining estimates of vertical accretion and paleowater depth. Results show RSL rise during MWP-1B did not exceed 10.2–7.7 m or rates of 30–23 mm/yr, and was likely less. The GBR did not drown, indicating resilience to MWP-1B. These findings are more consistent with Tahiti and other Pacific records and do not support the Barbados record of MWP-1B as an abrupt step in global sea level, with a magnitude > 11 m.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Submerged coral reef systems have been used extensively to reconstruct the pattern of global ice sheet dynamics and sea-level changes over the past 30,000 years1,2. Studies have been undertaken on fossil reefs in various geologic and tectonic settings including active tectonic margins e.g., Barbados, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea3,4,5, subsiding oceanic islands e.g., Tahiti, Hawaii6,7 and stable continental margins e.g., Great Barrier Reef8. Records from these sites show consistency in the basic pattern of Last Glacial Maximum to deglacial sea-level rise9,10. However, despite recent progress11,12 there is still considerable debate concerning the timing, magnitude and reef response to abrupt sea-level rise events—so called meltwater pulse events (i.e., MWP-1A and 1B) that are superimposed on this general trend, and crucially have been linked to the catastrophic collapse of ice sheets and associated global climate changes4,6,13. Robust constraints on past MWPs are vital as they provide the sole observations of ice-sheet dynamics and global sea-level rise that are feared for the future. For example, there are concerns about the Antarctic ice sheet linked to marine ice sheet (MISI) and ice cliff instability (MICI) where scenarios predict up to +1.7 m with dynamic instability under SSP5-8.514. Their importance is further highlighted by the identification of the saddle collapse mechanism invoked for MWP-1A15.

Recent debates9,16,17 concerning MWP-1B have questioned the published sedimentary, stratigraphic, and chronological data from Barbados and Tahiti. Earlier radiocarbon and then U-series results from the Barbados submerged reefs defined the timing, rate, and magnitude of MWP-1A and 1B4,13 that were marked by distinct reef drowning events18. Using new U-Th ages from corals offshore Barbados, Abdul et al.19 redefined MWP-1B as initiating by 11.45 ka and ending at 11.1 ka as sea-level rose 14 ± 2 m and rates of sea-level rise reached 40 mm/yr. Notably, this rate is ~10 times faster than the current global rise, and establishing if reefs can or cannot keep pace with this rate is relevant for understanding future changes20,21. However, the existence of MWP-1B remains in conflict with previous work by Bard et al.22, who used U-Th to date shallow water corals from the Tahiti reef and found no significant discontinuity in the sea-level rise or reef drowning that could be associated with the MWP-1B period. Furthermore, Bard et al.17 argued the Barbados record was affected by three main problems that could explain the discrepancy. First, the Barbados cores are from an active subduction zone and could be influenced by large tectonic movements. Second, Acropora palmata may not be a reliable sea level marker during rapid sea-level rise, as its depth distribution can extend below 0–5 m. Third, differing glacio-isostatic adjustment (GIA) responses complicate the comparison of RSL records, including MWPs derived from the two locations e.g., refs. 20,23,24. In response, Mortlock et al.16 argued tectonics has not biased the Barbados record and that the two records could be reconciled by greater paleowater uncertainties in the Tahiti record. Finally, a reanalysis of the published data25 argued the Barbados reefal sequences contain hurricane-generated coral clasts, suggesting that there is insufficient dating to constrain the onset of MWP-1A while necessitating an earlier timing and reduced magnitude for MWP-1B (11.3 ka, 8–11 m in ~250 years).

To address the controversy around the existence, timing, rate, and magnitude of MWP-1B additional, continuous reef records are required. In this study, we present a synthesis of new and existing geomorphic, sedimentologic, biological and dating information from fossil reef cores recovered from the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) shelf-edge reefs during Integrated Ocean Drilling Program (IODP) Expedition 325 (Exp. 325) that span reef growth and RSL rise during MWP-1B (Fig. 1). We confirm that the GBR did not drown as a direct result of MWP-1B and the GBR RSL rise is more consistent with Tahiti and does not support the Barbados record of MWP-1B as an abrupt step in global sea level, at least with magnitude > 11 m.

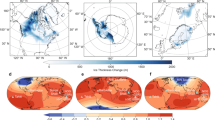

High-resolution bathymetric images showing surface geomorphology of NOG-01B (a), HYD-01C (b), and HYD-02A (c), the drill-hole locations (red lines represent core penetration depths), and the depth of distinct terraces on the adjacent seabed. Bathymetric data sets originally published in ref.45 and publicly available at ref.49. d–f Simplified stratigraphic sections showing the distribution of recovered core intervals, coral assemblages (A through F) and their interpreted paleowater depths (< 10 m or > 20 m), and selected U–Th (black) and 14C AMS (blue) ages at M0057A, M0034A, and M0042A. Chronostratigraphic boundaries of the shallow Reef 4 sequence are represented by solid colored lines (orange base and purple top), and short dashes show their corresponding deep-water fore-reef slope deposits after8,21,26.this study (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for more details). g Map of the GBR showing flooded shelf areas corresponding to sea levels between 45 m and 75 m below (green) the present-day GBR bathymetry after50, that approximates the period representing the growth of the “proto-GBR” (Reef 4) between ~13–10 ka. Images51 of representative core sections showing (h) shallow, high-energy (0–6 m) coralgal assemblages (a) (M0057A-06R) characterizing growth during the Younger Dryas, before and after Meltwater Pulse 1B (MWP-1B), and i deep-water (> 20 m) fore-reef slope assemblages (d) (M0034A-01R) following reef drowning ~10 ka (blue line). More detailed geomorphic, chronostratigraphic, and biologic information is given in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Results and discussion

Continued shallow water reef growth during meltwater pulse 1B in the GBR

Our results show that the GBR grew rapidly and continuously throughout MWP-1B and was characterized by shallow, high-energy coralgal reef assemblages and did not drown until after ~10 ka (Fig. 1)21,26. New comparisons with modern Indo-Pacific27 coral, coralline and vermetid assemblages and the Reef 4 assemblages confirm that paleowater depths range from 0–6 m to 0–10 m at both transects before, likely during and after MWP-1B (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. 1). NOG-01B provides the most complete record with 0–6 m paleowater depths (cA2—Isopora, aA1—shallow algal assemblage) from the start of MWP-1B at 11.45 ka to at least 11.28 ka before transitioning to again shallow 0–10 m paleowater depths (cA1?—Isopora & Acropora, aA1) by 10.93 ka. Despite drilling and recovery issues, HYD-01C/2 A are consistent with this general pattern of shallow coralgal assemblages, and paleowater depths 0–10 m, before (cA1, cA2, and aA1) and after (cC—merulinids, with shallow water algal indicators aA1) MWP-1B (Supplementary Fig. 1).

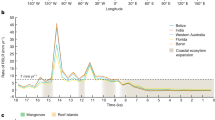

NOG-01B (M0057A) (a) (red symbols) and HYD-01C/02 A (M0034A, M0042A) (b) (blue symbols) age vs. depth data, paleowater depths (gray vertical lines), the vertical reef accretion histories (red and blue linear growth segment modified after21) are based on all available in situ U/Th coral and calibrated 14C AMS coral and coralline algal ages (see Supplementary Table 1). c We calculated their average vertical accretion rates (mm/yr) using a visual best fit approach (after21) (red stepped plot for NOG-01B and blue for HYD-01C/02 A) and a Monte Carlo analysis showing the simulated median vertical accretion (red dashed line for NOG-01B and blue for HYD-01C) through time that also fully captures the age and depth uncertainties of the age model (see Supplementary Fig. 3 for more details). Average vertical accretion rates (mm/yr) from the Holocene reefs adjacent to the HYD-01C, 02 A, and NOG-01B transects are shown in the green stepped plot21. The Younger Dryas (gray), Meltwater Pulse 1B (MWP-1B) (green), and time of Reef 4 drowning (RD) (red hashed) are shown as vertical shaded bars.

Analysis of the vertical accretion data also suggest that the GBR was not negatively impacted by MWP-1B (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. 3). Using a similar approach to Webster et al. 21, we estimated vertical accretion rates for Reef 4 using two methods (linear visual fit and Monte Carlo simulations), which use only in situ corals and coralline algae that yielded robust U–Th and calibrated 14C AMS ages (NOG-01B n = 70; HYD-01C n = 47). At both NOG-01B and HYD-01C, the linear visual fit and the Monte Carlo vertical accretion analyses were broadly consistent (Fig. 2a–c). NOG-01B rates were similar before and after MWP-1B ranging between 4.7 and 6.3 mm/yr. In contrast, HYD-01C grew rapidly at 12 mm/yr immediately prior to MWP-1B before the vertical accretion slowed to about 4 mm/yr afterward. HYD-02A was excluded from the vertical accretion analysis due to few in situ samples (n = 7) but the vertical accretion rates for these points are similar (3-4 mm/yr) to the adjacent HYD-01C (Fig. 1c). Critically, these vertical accretion rates of between 4 and 6 mm/yr (see rate from comparable modern reefs, Fig. 2c) were maintained until at least 10.5–10.3 ka as Reef 4 approached final shallow water reef drowning well after the end of the proposed MWP-1B timeframe.

GBR constraints on MWP-1B and relationship to other deglacial RSL reef records

Based on key in situ RSL index points we reconstructed the maximum magnitude and rate of sea-level rise during MWP-1B possible for the GBR data (Fig. 3). This reconstruction accounts for the maximum age and depth uncertainties for each in situ RSL index point including uncertainties in the age (2σ), paleowater depth, and vertical position (drilling recovery error) (see Supplementary Fig. 4 for details). The maximum RSL pathway based on key GBR index points at the start of MWP-1B that intersects with the end of MWP-1B (11.1 ka) (Supplementary Fig. 4B) allows us to calculate the likely amplitude and rate of RSL rise. We conclude that the maximum RSL rise possible from the NOG and HYD sites is 10.2 m and 7.7 m at a rate of 30–23 mm/yr, respectively, between 11.48 and 11.1 ka. While we cannot rule this upper boundary out as it is within the bounds of uncertainty, based on consistent vertical accretion rates and shallow water assemblages after MWP-1B, the magnitude and rate of sea-level rise is likely to be significantly less. Unfortunately, a lack of recovery and drilling disturbances mean that the GBR record does not record the last part the MWP-1B interval (11.28–11.1 ka) continuously with in situ RSL points. However, 7 ex situ ages also span this interval (11.44–11.12 ka), which while clearly not in situ, are composed of the same high energy and shallow water coralgal assemblages (0–6 m, 0–10 m) (Supplementary Fig. 2, Fig. 5) characterizing the adjacent reef sequences. Taken together, these data suggest similar shallow water paleo-environmental conditions before, during, and after MWP-1B in the GBR.

RSL records from the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) (NOG-01B) (M0057A) (a) (red symbols) and HYD-01C/02 A (M0034A, M0042A) (b) (blue symbols) (this study), Tahiti (c) (orange symbols), New Guinea (c) (brown and yellow symbols), Vanuatu (d) pink and green symbols), and Barbados (e) (blue symbols) are shown. The timing, magnitude, and rate of the RSL change during Meltwater Pulse 1B (MWP-1B) are shown for the GBR (this study), Tahiti22, New Guinea3,28, Barbados–dark blue19, light blue25. See the original data sources for more details about sample context, tectonic corrections, age uncertainties, and paleowater estimates applied to the RSL records in these other studies. The Younger Dryas (gray), MWP-1B (green), and time of GBR Reef 4 drowning (RD) (red hashed) are shown as vertical shaded bars.

Figure 3 plots all the key fossil coral reef accretion and RSL reef data spanning 13.5–9.5 ka, including the MWP-1B interval. While it is not possible to directly compare sea level records between sites due to GIA, nor is it within the scope or purpose of this paper to reevaluate and reinterpret these records17, several insights are possible by viewing these data together. First, from ~13.5 ka, through the Younger Dryas in the lead up to the start of MWP-1B, the pattern of reef accretion composed of shallow water reef assemblages is generally similar between all the records. It is only from MWP-1B starting at ~11.45 ka that Barbados deviates from the GBR and Tahiti, and by ~11.1 ka is distinctly offset from both datasets with the dated corals and particularly the RSL envelope (maximum and best estimate)19 lying well above the upper paleowater boundary of the majority of the Pacific RSL index points (Supplementary Fig. 5). Second, the MWP-1B intervals in the GBR, Tahiti and other Pacific reef records (New Guinea, Vanuatu)3,22,28 are broadly consistent, displaying similar continuous growth, vertical accretion rates and shallow assemblages. Third, our reconstruction suggests the RSL rise during MWP-1B did not exceed 8 m and 11 m at HYD and NOG, respectively, and likely was considerably less (e.g., median mid-point ~2–3 m, ~3–5 mm/yr; Supplementary Fig. 5) given the available evidence, and is consistent with the Tahiti record22. Fourth, due to gaps in the GBR record and vertical uncertainties (drilling recovery and paleowater) it is not possible to constrain MWP-1B further, however, it does not support the Barbados record of MWP-1B as an abrupt step in global sea level, at least with magnitude > 11 m17,25.

Implications for ice sheet dynamics and coral reef drowning

Our understanding of past MWP’s is vital to future predictions of global ice sheet instability. The absence of major ice sheet collapse during MWP-1B–at least corresponding to sea-level rise > 11 m and that is linked solely to the Northern Hemisphere ice sheets19–is consistent with recent reconstructions and models showing no significant accelerated melting of the Laurentide29,30 and Fennoscandian31,32 ice sheets and no Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) perturbations33,34 at this time. Further, the absence of a large MWP-1B may have positive implications illustrating the resilience of ice-sheets (or at least their buffering effect) during global warming over the same period35. However, it is not possible to rule out future instability of the Antarctic ice sheets that are reported to be at risk from MISI & MICI processes14,36 triggered by proximal and distal climate perturbations37,38. Finally, the lack of reef drowning as a direct result of MWP-1B in the GBR, Tahiti and other Pacific sites supports emerging evidence that deglacial and Holocene reef systems can show remarkable resilience to rapid sea-level events21, but it is likely synergistic paleoenvironmental factors (increases in SST, ocean acidification, sediment/nutrient flux) that ultimately cause final reef demise39,40,41,42,43.

Our analysis of the Exp. 325 data confirms that the Reef 4 “proto-GBR”: (1) did not drown as a direct result of MWP-1B, and (2) the reef growth history and calculated RSL rise envelopes are more consistent with the Tahiti and other Pacific records, and do not support the Barbados record of MWP-1B as an abrupt step in global sea level, at least with magnitude > 11 m. This has implications for understanding the sensitivity of reefs to sea-level rise and suggests that in the case of the GBR a sea-level rise with a maximum magnitude of 7–11 m and rate of 23–30 mm/yr was not sufficient to cause direct reef drowning. Furthermore, the possible absence of MWP-1B may have implications for the resilience of ice-sheets during global warming over the same period. However, additional high quality fossil reef records from other locations (e.g., Hawaii IODP Exp. 389, Belize, Seychelles Bank), along with more precise paleowater depth constraints, are needed to more fully constrain MWP-1B and its implications for ice sheet dynamics, and corresponding geochemical proxy data are required to tease out the paleoenvironmental factors responsible for the ultimate demise of the GBR reef ~10 ka.

Methods

Study sites and data analysis

This study integrates new and existing data from three drill sites through a drowned shelf edge reef 46-54 meters below sea level (mbsl) at Noggin Pass (NOG-01B, M0057) and Hydrographer’s Passage (HYD-01C, M0034A, HYD-02A, M0042A) that developed between 13 and 10 ka, encompassing the postulated MWP-1B interval (Fig. 1). Located far-field and on gently sloping continental margin, the GBR is well suited to constrain rapid sea-level rise and explore reef drowning8,44. This reef represents one of the five distinct reef sequences (Reef 1 to 5) in the Exp 325 record of the past ∼30 kyr, and is referred to as the “proto-GBR” (Reef 4)8,21. Morphologically, Reef 4 displays barrier-reef-dominated morphologies characterized by numerous pinnacles and sub-terraces, and can be traced almost continuously over 2000 km along the GBR shelf45,46. Earlier work suggests Reef 4 at HYD-01C and NOG-01B, located over 500 km apart, initiated growth soon after the platform flooding around 13 ka and was characterized by a thriving shallow-water (<5–10 m) reef community composed mainly of robustly branching and massive acroporids26, that grew continuously throughout MWP-1B and only drowning around 10 ka, perhaps due to higher sediment flux and reef stress21,47. This implied the GBR data were more consistent with Tahiti and not Barbados. However, so far RSL reconstructions, including GIA in the GBR, have been focused on the broad patterns over the past 30 kyr, limited to defining the sea-level fall to the LGM8 or attempts to reconcile MWP-1A11 and the impact of sediment loading on RSL48. Here we have assembled a database of 154 new and existing age data comprising U/Th corals, re-calibrated 14C-AMS corals, algae, and microbialite ages (see Supplementary Table 1 and 2 for more detail). These dates are integrated with a revised stratigraphic context, vertical accretion analysis, and coralgal paleowater depth estimates and used to reconstruct the detailed Reef 4 vertical accretion history and most likely RSL envelope before, during, and after MWP-1B.

Data availability

All data generated in this study are included in the Supplementary Information file.

References

Camoin, G. F. & Webster, J. M. Coral reef response to quaternary sea-level and environmental changes: state of the science. Sedimentology 62, 401–428 (2015).

Yokoyama, Y. & Esat, T. M. In Handbook of Sea-Level Research 104-124 (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2015).

Chappell, J. & Polach, H. Post-glacial sea-level rise from a coral record at Huon Peninsula, Papua New Guinea. Nature 349, 147–149 (1991).

Fairbanks, R. G. A 17000 year glacio-eustatic sea-level record: influence of glacial melting rates on the Younger Dryas event and deep ocean circulation. Nature 342, 637–642 (1989).

Cutler, K. B. et al. Radiocarbon calibration and comparison to 50 kyr BP with paired 14 C and 230Th dating of corals from Vanuatu and Papua New Guinea. Radiocarbon 46, 1127–1160 (2004).

Deschamps, P. et al. Ice-sheet collapse and sea-level rise at the Bolling warming 14,600 years ago. Nature 483, 559–564 (2012).

Sanborn, K. L. et al. New evidence of Hawaiian coral reef drowning in response to meltwater pulse-1A. Quat. Sci. Rev. 175, 60–72 (2017).

Yokoyama, Y. et al. Rapid glaciation and a two-step sea level plunge into the Last Glacial Maximum. Nature 559, 603–607 (2018).

Lambeck, K., Rouby, H., Purcell, A., Sun, Y. & Sambridge, M. Sea level and global ice volumes from the Last Glacial Maximum to the Holocene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 15296–15303 (2014).

Carlson, A. E. & Clark, P. U. Ice sheet sources of sea level rise and freshwater discharge during the last deglaciation. Rev. Geophys. 50, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011rg000371 (2012).

Lin, Y. et al. A reconciled solution of Meltwater Pulse 1 A sources using sea-level fingerprinting. Nat. Commun. 12, 2015 (2021).

Hibbert, F. D. et al. Coral indicators of past sea-level change: a global repository of U-series dated benchmarks. Quat. Sci. Rev. 145, 1–56 (2016).

Bard, E., Hamelin, B. & Fairbanks, R. G. U-Th ages obtained by mass spectrometry in corals from Barbados: sea level during the past 130,000 years. Nature 346, 456–458 (1990).

IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group. 2391 (2021).

Gregoire, L. J., Otto-Bliesner, B., Valdes, P. J. & Ivanovic, R. Abrupt Bolling warming and ice saddle collapse contributions to the Meltwater Pulse 1a rapid sea level rise. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 9130–9137 (2016).

Mortlock, R. A., Abdul, N. A., Wright, J. D. & Fairbanks, R. G. Reply to comment by E. Bard et al. on “Younger Dryas sea level and meltwater pulse 1B recorded in Barbados reef crest coral Acropora palmata” by N. A. Abdul et al. Paleoceanography 31, 1609–1616 (2016).

Bard, E., Hamelin, B., Deschamps, P. & Camoin, G. Comment on “Younger Dryas sea level and meltwater pulse 1B recorded in Barbados reefal crest coral Acropora palmata” by N. A. Abdul et al. Paleoceanography 31, 1603–1608 (2016).

Blanchon, P. & Shaw, J. Reef drowning during the last deglaciation: evidence for catastrophic sea-level rise and ice-sheet collapse. Geology 23, 23 (1995).

Abdul, N. A., Mortlock, R. A., Wright, J. D. & Fairbanks, R. G. Younger Dryas sea-level and meltwater pulse 1B recorded in Barbados Reef-Crest Coral Acropora palmata. Paleoceanography 31, 330–344 (2016).

Yokoyama, Y. & Purcell, A. On the geophysical processes impacting palaeo-sea-level observations. Geosci. Lett. 8, 13 (2021).

Webster, J. M. et al. Response of the Great Barrier Reef to sea-level and environmental changes over the past 30,000 years. Nat. Geosci. 11, 426–432 (2018).

Bard, E., Hamelin, B. & Delanghe-Sabatier, D. Deglacial meltwater pulse 1B and younger Dryas sea levels revisited with boreholes at Tahiti. Science 327, 1235–1237 (2010).

Milne, G. A., Gehrels, W. R., Hughes, C. W. & Tamisiea, M. E. Identifying the causes of sea-level change. Nat. Geosci. 2, 471–478 (2009).

Clark, P. & Mix, A. Ice sheets and sea level of the Last Glacial Maximum. Quat. Sci. Rev. 21, 1–7 (2002).

Blanchon, P., Medina-Valmaseda, A. & Hibbert, F. D. Revised postglacial sea-level rise and meltwater pulses from Barbados. Open Quat. 7, https://doi.org/10.5334/oq.87 (2021).

Humblet, M. et al. Late glacial to deglacial variation of coralgal assemblages in the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Glob. Planet. Change 174, 70–91 (2019).

Braga, J. C., Humblet, M., Ramos, D. A. E., Dechnik, B. & Webster, J. M. Quaternary coral, coralline algal and vermetid assemblages as sea-level indicators: a review. IAS Special Publication ‘Coral Reefs and Sea-Level Change: Quaternary Records and Modelling. A Window Into Future’ 49, 1–38 (2022).

Edwards, R. L. et al. A large drop in atmospheric 14 C/12 C and reduced melting in the Younger Dryas, documented with 230Th ages of corals. Science 260, 962–968 (1993).

Tarasov, L., Dyke, A. S., Neal, R. M. & Peltier, W. R. A data-calibrated distribution of deglacial chronologies for the North American ice complex from glaciological modeling. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 315-316, 30–40 (2012).

Gowan, E. J., Tregoning, P., Purcell, A., Montillet, J.-P. & McClusky, S. A model of the western Laurentide Ice Sheet, using observations of glacial isostatic adjustment. Quat. Sci. Rev. 139, 1–16 (2016).

Stroeven, A. P. et al. Deglaciation of Fennoscandia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 147, 91–121 (2016).

Cuzzone, J. K. et al. Final deglaciation of the Scandinavian Ice Sheet and implications for the Holocene global sea-level budget. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 448, 34–41 (2016).

Mikolajewicz, U. et al. Deglaciation and abrupt events in a coupled comprehensive atmosphere–ocean–ice sheet–solid earth model. Clim. Discuss. 2024, 1–46 (2024).

Liu, Z. Evolution of Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation since the last glaciation: model simulations and relevance to present and future. Philos. Trans. Ser. A Math., Phys., Eng. Sci. 381, 20220190 (2023).

Shakun, J. D. et al. Global warming preceded by increasing carbon dioxide concentrations during the last deglaciation. Nature 484, 49–54 (2012).

Bamber, J. L., Riva, R. E. M., Vermeersen, B. L. A. & LeBrocq, A. M. Reassessment of the potential sea-level rise from a collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet. Science 324, 901–903 (2009).

Yokoyama, Y. et al. Widespread collapse of the Ross Ice Shelf during the late Holocene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 2354–2359 (2016).

Sproson, A. D., Yokoyama, Y., Miyairi, Y., Aze, T. & Totten, R. L. Holocene melting of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet driven by tropical Pacific warming. Nat. Commun. 13, 2434 (2022).

Toth, L. T. et al. Climatic and biotic thresholds of coral-reef shutdown. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 369–374 (2015).

Sanborn, K. L. et al. The impact of elevated nutrients on the Holocene evolution of the Great Barrier Reef. Quat. Sci. Rev. 332, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2024.108636 (2024).

Precht, W. F. & Aronson, R. B. In Coral Reefs at the Crossroads (ed D. K Hubbard, Rogers, C.S., Lipps, J.H., Stanley, Jr., G.D) 155-173 (Springer, 2016).

Kubota, K., Yokoyama, Y., Ishikawa, T., Suzuki, A. & Ishii, M. Rapid decline in pH of coral calcification fluid due to incorporation of anthropogenic CO(2). Sci. Rep. 7, 7694 (2017).

Cybulski, J. D. et al. Coral reef diversity losses in China’s Greater Bay Area were driven by regional stressors. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb1046 (2020).

Esat, T. M., Yokoyama, Y. & Webster, J. M. Constraining rapid sea level change through radiometric dating of corals growing over a range in paleowater depths. Quat. Sci. Adv. 7 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qsa.2022.10005 (2022).

Abbey, E., Webster, J. M. & Beaman, R. J. Geomorphology of submerged reefs on the shelf edge of the Great Barrier Reef: The influence of oscillating Pleistocene sea-levels. Mar. Geol. 288, 61–78 (2011).

Hinestrosa, G., Webster, J. M., Beaman, R. J. & Anderson, L. M. Seismic stratigraphy and development of the shelf-edge reefs of the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Mar. Geol. 353, 1–20 (2014).

Patterson, M. A. et al. Bioerosion traces in the Great Barrier Reef over the past 10 to 30 kyr. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 542 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.109503 (2020).

Lin, Y. et al. Relative sea level response to mixed carbonate-siliciclastic sediment loading along the Great Barrier Reef margin. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 607, 118066 (2023).

AusSeabed. AusSeabed, https://www.ausseabed.gov.au/data (2025).

Felis, T., Hinestrosa, G., Köhler, P. & Webster, J. M. Role of the deglacial buildup of the Great Barrier Reef for the global carbon cycle. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021gl096495 (2022).

Webster, J. M., Yokoyama, Y., Cotterill, C. & Scientists, E. Proceedings of the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Volume 325 Expedition Reports Great Barrier Reef Environmental Changes. (Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Management International, Inc., for the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program; https://doi.org/10.2204/iodp.proc.325.2011 2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank the IODP and ECORD (European Consortium for Ocean Research Drilling) for drilling the shelf edge of the Great Barrier Reef, and the Bremen Core Repository members for organizing the onshore sampling party. Financial support of this research was provided by the Australian Research Council (Grant Nos. DP1094001 DP200100206), ANZIC (Grant Nos. LG_0319, AILAF2103, PCAFX38901), and the Hanse-Wissenschaftskolleg Institute for Advanced Study (HWK), Delmenhorst, Germany to J.M.W. JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Nos. JP26247085, JP15KK0151, JP16H06309, JP17H01168, 23KK0013 and 24H00094) and JST CREST (JPMJCR23J6) provided support to YY.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M.W. was the primary author and responsible for the project design, integration of all data sets, and interpretations; Y.Y., M.H., J.C.B., T.E., S.F., and E.B. contributed to the data generation, analysis, interpretation, and also manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Benjamin Petrick and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Webster, J.M., Yokoyama, Y., Humblet, M. et al. Constraints on sea-level rise during meltwater pulse 1B from the Great Barrier Reef. Nat Commun 16, 4698 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59858-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59858-0