Abstract

The liquid phase hydrogenation of nitroarenes is an important industrial reaction. The active sites are typically supported metal nanoparticles, which can be easily deactivated when sulfur groups are present in the substrate. Here, we report a new strategy for converting these S-containing nitroarenes by developing a dual-sites Pt/CeO2 catalyst consisting of highly defective CeO2 with abundant active oxygen vacancy and Pt sub-nano clusters. The hydrogenation of the nitro group in S-containing nitroarenes is induced to occur on the oxygen vacancies of the support rather than on the metal nanoparticles, which act only as the site of activating H2 by spillover. This functionality is not inhibited by strong chemisorption of the reactant S-groups, which is different from the hydrogenation of the nitro groups. Spillover H migrates to the oxygen vacancy site on the surface of defective CeO2, where the nitro-group is activated and reduced. This unconventional mechanism of hydrogenation is proven by combining many characterizations, theoretical modelling, kinetic and poisoning experiments. The best Pt/CeO2-300 catalyst shows a high reaction rate of 3.9 mmol·gcat.−1·h−1 with 5-amino benzothiazole selectivity of > 99%. It could produce over 145 kg·kgPt−1 of pure 5-amino benzothiazole in 250 hours on stream under continuous flow conditions. It is also proven and quantified by studying several molecules with different sizes and electronic structures that the accessibility of the -NO2 group to the Pt surface determines where the nitro groups are hydrogenated. Larger conjugated structures inhibit accessibility to the Pt surface of the -NO2 group, making it more prone to vacancy-activated nitro groups. This study provides valuable insights into the rational design and precise development of catalysts for the hydrogenation of liquid-phase chemicals containing S-groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Amine compounds represent a vital class of fine chemical intermediates extensively utilized as raw materials in the manufacturing of pharmaceuticals, pesticides, rubber, dyes, and various other chemical products1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Notably, amino compounds containing the thiazole ring serve as key intermediates in the synthesis of drugs and pesticides8,9. Conventional methods for amine preparation involve the reduction of corresponding nitro compounds utilizing stoichiometric Fe or Zn reagents in the presence of diverse proton sources or through other catalytic procedures utilizing toxic reducing agents such as N2H4 or NaBH410. In comparison to the aforementioned reducing agents, the utilization of molecular hydrogen (H2) is a preferable green method, providing high atom efficiency, as water is the sole by-product. Due to several practical advantages associated with heterogeneous catalysts11,12,13, including simpler procedures for separation and recycling, as well as a reduced amount of metal impurities in the final products, catalytic hydrogenation of aromatic nitro compounds (nitroarenes) with H2 using supported metal catalysts finds extensive application in the synthesis of various functionalized anilines for industrial production.

Early research on supported metal catalysts for nitro-group hydrogenation primarily focused on the modification of metals. Transition metals, particularly noble metals like Pt and Pd, have been widely employed in various hydrogenation reactions due to their unpaired d electrons14,15,16. Studies have explored the modulation of metal geometry and electronic structure17,18,19, including nanoparticle size20, bimetallic effects, organic ligand modification21, and support effects, such as strong metal-support interaction6,9,22,23. In hydrogenation liquid-phase reactions, when the reactants also contain sulfur groups, the latter typically poison supported metal catalysts24 due to a strong chemisorption, inhibiting the hydrogenation abilities. A strategy developed to limit this effect is to induce, by strong-metal support interaction (SMSI) effect, the formation of a thin layer of unsaturated oxides (such as TiOx and HxMoO3) on the surface of metal nanoparticles9,23. This strategy could limit the sulfur poisoning, but also reduce the activity of the catalyst.

The oxides used as catalyst support in the liquid hydrogenation reaction may also have a catalytic activity associated with the defect site (oxygen vacancies, Ov). They are indicated to play a role in many reactions, such as CO2 hydrogenation, VOC degradation, reduction of NOx and hydrocarbon reforming25,26,27. In the nitro group hydrogenation, the surface Ov sites selectively adsorb the -NO2 groups without competing adsorption with other functional groups. This characteristic allows an alternative strategy for the development of catalysts resistant to poisoning, rather than creating an oxide layer on the nanoparticle’s surface, which decreases the utilization and accessibility of the metal sites and uses the surface Ov sites as the primary active sites. The limiting factor is the lower ability of the surface Ov sites to activate H2. This limitation could be overcome by generating spillover H on the metal nanoparticles and realizing efficient surface mobility to the surface Ov sites, adsorbing the -NO2 groups. Studies on the activation of nitro groups on oxygen vacancies have been reported28,29,30,31. Still, the relationship between the nitro group structure and active sites has not been investigated, nor has the role of spillover hydrogen been investigated in reducing the nitro groups. Specifically, the factors governing the selectivity of nitro group activation on metals or vacancies remain unexplored.

CeO2 was chosen as the substrate due to the unique features of ceria, i.e., redox properties associated with the Ce3+/Ce4+ couple and the stabilization of a highly defective structure containing many oxygen vacancies26,27,32. For Pt/CeO2 catalyst, the dissociated H2 on Pt can induce the reduction of Ce4+ to Ce3+ and the controlled formation of oxygen vacancies, which can facilitate the adsorption and activation of the nitro group. Herein, we prepared highly defective CeO2, which was applied to support loading Pt sub-nano clusters. By extensive characterization, we exclude the presence of SMSI. These catalysts were investigated in the hydrogenation of various sulfur-containing nitroarenes. Kinetic and poison experiments indicate that the accessibility of the nitro group to the sub-nanosized Pt surface determines the activation site of the nitro group. Here, we introduce a methodology to describe the structural features of nitro groups and determine the effectiveness of active sites in a Pt/CeO2 catalyst.

Results

Synthesis and characterizations of the defective Pt/CeO2 catalysts

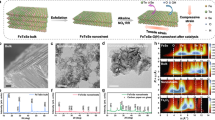

The CeO2 support was synthesized by a hydrothermal method with urea as an additive to increase the defect sites of CeO233, as detailed in the experiment section. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images revealed that the synthesized CeO2 exhibits a rod-shaped structure characterized by individual CeO2 nanoparticles in the size of 5–10 nm (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Figs. S1, 2; the letter S indicates Figures reported in the Supplementary Information). These CeO2 nanoparticles do not have preferential exposed surfaces, as shown in Fig. 1b and Supplementary Figs. S3, 4, where different CeO2 nanoparticles expose the (200), (111), and (220) faces, respectively. The FFT image derived from Fig. 1b also indicates that the rod-shaped structure consists of a polycrystalline arrangement of CeO2 nanoparticles. This irregular polycrystalline structure results in a high concentration of defects in CeO2. From the XRD data in Supplementary Fig. S5, all Pt/CeO2-T (T refers to the reduction temperature) exhibiting similar peaks at 2θ = 28.5°, 33.1°, 47.5°, and 56.5° correspond to the (111), (200), (220), and (311) faces of CeO2 (JCPDS 34-0394), respectively. The absence of detection of Pt crystalline phases suggests a high dispersion of Pt species due to its low content ( ~ 0.5%, Supplementary Table S1) and strong interaction with CeO2. Aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM was used to determine the morphology of the Pt/CeO2 catalysts. Several Pt single atoms and nanoclusters ( < 1 nm) were anchored on the surface of CeO2 (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. S3c). Elemental mapping by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) revealed the highly dispersed nature of Pt species on CeO2 (Supplementary Fig. S3d).

a, b SEM and HR-TEM images of as-synthesized CeO2. c Atomic resolution HAADF-STEM images of Pt/CeO2-300. d H2-TPR profile of Pt/CeO2. e H2-O2 titration results of Pt/CeO2-T and Pt/CeO2-C samples. f Pt 4 f XPS spectra of H2PtCl6/CeO2 and Pt/CeO2 catalysts. g XANES spectra at the K-edge of Pt of the Pt foil, PtO2, and Pt catalyst. h R-space spectra from the Fourier transform of the phase-uncorrected EXAFS, (i) EXAFS fitting curve for Pt in Pt/CeO2-300, and WT-EXAFS plots of (j) Pt foil, (k) Pt/CeO2-300, and (l) Pt/CeO2-450.

In contrast to the morphology of as-synthesized CeO2, commercial CeO2 (CeO2-C) exhibits a block-like structure of approximately 100 nm (Supplementary Fig. S1). Pt/CeO2-C with 0.5% Pt content displayed clearly visible Pt nanoparticles in the range of 2-3 nm (Supplementary Fig. S6). The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) specific surface area of Pt/CeO₂-C was only 5 m²·g⁻¹ (Supplementary Fig. S7). In contrast, the BET specific surface area of the Pt/CeO₂-T catalysts ranges from 83 to 115 m²·g⁻¹. Notably, the Pt/CeO₂-300 catalyst achieves the largest surface area, primarily attributed to its optimal reduction conditions. For better comparison, we also prepared a Pt/CeO₂-N sample with a high surface area of 96 m²·g⁻¹ (CeO₂-N originates from a one-step calcination of Ce(NO₃)₃). Similar to Pt/CeO₂-T catalysts, the Pt/CeO₂-N catalyst lacks discernible Pt nanoparticles (Supplementary Fig. S8), indicating a similar Pt morphology.

The high defective Pt/CeO2-T catalysts with a Pt loading of 0.5 wt% were prepared by the wet impregnation method. When H2PtCl6/CeO2 is reduced at high temperatures under H2, the dissociated H2 can induce the reduction of Ce4+ to Ce3+ and the formation of oxygen vacancies (Ov) through H2O formation and desorption. According to the equation \(-{{{{\rm{Ce}}}}}^{4+}{-{{{\rm{O}}}}}^{2-}-{{{{\rm{Ce}}}}}^{4+}+{H}_{2}\to -{{{{\rm{Ce}}}}}^{3+}-{{{\rm{\square }}}}-{{{{\rm{Ce}}}}}^{3+}+{H}_{2}O\) (where □ refers to oxygen vacancy)32,34, the appearance of the signal of H2O (m/z = 18) indicates the generation of Ov under a reduction atmosphere. The maximum amount of Ov is formed at 300 oC (Fig. 1d). The increase in Ov is not significant at higher reduction temperatures because reconstruction of the oxide occurs. To quantitatively determine Ov in the as-prepared Pt/CeO2 samples, H2-TPR and H2-O2 titration methods were used (Fig. 1d, e and Supplementary Fig. S9). H2-TPR was used to probe reactions of H2 on Pt/CeO2, which is often used to assess the reducibility (e.g., Ov formation) of oxide surfaces. The H2-TPR and CO2-TPD (Supplementary Fig. S10) of reduced Pt/CeO2-T catalysts further confirm the H2-TPR results (Fig. 1d). The Pt/CeO2-300 possesses the highest Ov content (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. S9). However, not all oxygen vacancies are active and can participate in the reaction35,36. The activity of oxygen vacancies in cerium oxide (CeO₂) is indeed highly dependent on their local environment and structural properties. In detail, their reactivity is influenced by several factors, such as coordination environment, defect association, and surface vs. bulk vacancies37,38,39,40,41,42. The H2-O2 titration results revealed that the content of Ov decreased in the following order: Pt/CeO2-300 > Pt/CeO2-N > Pt/CeO2-C (Supplementary Fig. S9). Therefore, the content of Ov rather than the specific surface area has a more significant impact on catalytic activity. The results show that Pt/CeO2-300 has active oxygen vacancies, while Pt/CeO2-C does not. The above series of characterization results shows that Pt/CeO2-300 is a two-site catalyst containing active Ov and Pt sites, while Pt/CeO2-C does not have (or in a much less pronounced way) oxygen vacancies.

The surface electronic states, as well as the valence states of the Pt elements of Pt/CeO2, were investigated through XPS, Pt L3-edge XANES, and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS). Supplementary Figure S11 exhibits the Ce 3 d XPS spectra of these catalysts, and the quantitatively calculated results are also listed. The Ce 3 d XPS spectra are fitted with ten peaks. The Ce3+ surface concentration (Ce3+/Ce3++Ce4+) on Pt/CeO2-300 is 30.0 at%, which is higher than that on Pt/CeO2-450. This effect is caused by the SMSI between the CeO2 support and Pt species, verified by the decrease in the binding energy of Pt as the reduction temperature increases, indicating that cerium oxide transfers electrons to Pt (Fig. 1f, g). As the XANES spectra show in Fig. 1g, the white line of the Pt/CeO2-300 curve lies between a Pt foil and PtO2 references, indicating the oxidation state of Ptδ+(0 < δ < 4) in Pt/CeO2-300. An apparent peak is observed at 1.60 Å from the spectra of the Fourier-transformed (FT) k3-weighted EXAFS, which is attributed to the characteristic peak of Pt bonded with O (Fig. 1h). Besides, a small signal proves the appearance of a Pt-Pt characteristic peak at 2.6 Å; thus, Pt clusters are coexistent for Pt/CeO2-300 (Fig. 1i), which is in accordance with the atomic resolution HAADF-STEM images of Pt/CeO2-300. No Pt-O in the extended X-ray absorption fine structure spectrum of Pt/CeO2-450, combined with electron microscopy results, indicates that Pt/CeO2-450 contains exclusively Pt nanoparticles. Furthermore, the wavelet transforms (WT) of Pt/CeO2-300 exhibit Pt-O bonding at 5 Å−2, which further confirms the existence of Pt clusters and SAs (Fig. 1j–l).

Catalytic results

We evaluated the catalytic performance of Pt/CeO2-T, Pt/CeO2-N, and Pt/CeO2-C catalysts in the hydrogenation of sulfur-containing 5-nitrobenzothiazole (NBT). H2 was the reductant, and hydrogenation was made at 80 °C and 2 MPa H2 pressure. Figure 2a shows that the Pt/CeO2-C has almost no activity in these conditions, even extending the reaction time to 250 min. When the H2 pretreatment temperature for the Pt/CeO2-T catalysts varies from 250 oC to 450 oC, the TOF value exhibits a clear volcanic curve. The Pt/CeO₂-300 catalyst, reduced at 300 °C, exhibits the highest reactivity for NBT hydrogenation (Supplementary Fig. S12). The NBT was fully converted over Pt/CeO2-300 within 30 min with a TOF value of 836 h−1. For a 30 min reaction, Pt/CeO2-450 achieves only 20% conversion, revealing that further increasing the reduction temperature above 300 °C decreases the catalyst reactivity. Pt/CeO2-N showed a TOF of 175 h−1. By correlating the BET surface areas and Ov concentrations (determined by hydrogen-oxygen titration) of various ceria samples with their catalytic activities, we discovered that the Ov concentration, rather than the specific surface area, plays a more significant role in determining the catalytic performance. It is also interesting to show that the NBT hydrogenation performance of Pt/CeO2-300 shows a comparable activity among the reported results in the literature (Fig. 2b)9,23.

a The kinetic curve of Pt/CeO2 catalyzed NBT hydrogenation (reaction conditions: 10 mg catalyst,10 mg NBT, 3 mL ethanol, 80 °C, 2 MPa H2). b A summary of the TOF value of reported catalysts for NBT hydrogenation9,23. c The results of H2-D2 exchange. d KIE value. e NBT reaction order, H2 reaction order, and apparent activation energy for NBT hydrogenation of Pt/CeO2-300, Pt/CeO2-450 catalysts. f ABT productivity as a function of time on stream over Pt/CeO2-300 (reaction conditions: 1.4 g Pt/CeO2-300; 5 mM NBT in ethanol, 5.4 mL h−1; 80 °C, 2 MPa H2). Data in a was presented as mean ± s.d. of three technical replicates.

The adsorption and activation of H2 is a critical step in the liquid phase hydrogenation reactions36,37. H2-D2 isotopic exchange experiments were conducted to check the hydrogen dissociation ability over Pt/CeO2 (Fig. 2c). The H2 dissociation rate follows the order of Pt/CeO2-450 > Pt/CeO2-C > Pt/CeO2-300. Despite its high hydrogen dissociation capability, Pt/CeO2-C has zero activity in the hydrogenation of NBT. We also explored the kinetic isotope effect (KIE) feeding D2 during the NBT hydrogenation (Fig. 2d). For Pt/CeO2-T catalysts, the reaction was slowed down by a factor of 1.2-1.3 as a result of the zero-point energy difference between isotopic isomers, indicating hydrogen dissociation does not participate in the rate-determining step38. Therefore, hydrogen dissociation capability is not the key factor contributing to the difference in activity in this reaction.

Subsequently, kinetic experiments to measure the apparent reaction order were carried out by determining the effect on the rate of the concentration of NBT and H2 pressure, maintaining the NBT conversion < 30% (differential conditions). As shown in Fig. 2e, the increase of the partial pressure of H2 can boost the reaction, while the reaction rate is suppressed in excess of NBT. The apparent reaction order of H2 over Pt/CeO2-300 and Pt/CeO2-450 catalysts is 0.34 and 0.46, respectively. This observation, i.e., the increase in the reaction order of H2 on raising the reduction temperature, is consistent with the differences in the hydrogen dissociation capabilities of the catalysts at different reduction temperatures. The apparent reaction order of NBT over Pt/CeO2-300 and Pt/CeO2-450 catalysts is − 0.76 and − 0.48, respectively. The Pt/CeO2-300 exhibits the strongest NBT adsorption strength39. Kinetic experiments at different temperatures allowed the measure of the apparent activation energy of Pt/CeO2-T. Pt/CeO2-300 shows the lowest activation energy of 32.7 kJ·mol−1 compared to 39.4 kJ·mol−1 of Pt/CeO2-450 (Fig. 2e).

In conclusion, the strong adsorption and activation of NBT on the catalyst surface facilitates the reduction of activation energy, thereby accelerating the reaction rate. Moreover, we expanded other nitro-containing thiazoles (Supplementary Table S2). These results indicate that the Pt/CeO2-300 catalyst has excellent substrate generality, whether for electron-donating or electron-withdrawing groups. In addition, the catalyst’s stability was assessed using a micro-fixed bed reactor in continuous flow experiments. The catalyst’s activity consistently remained at approximately 30% over 70 h on stream, with a product selectivity of 100% (Supplementary Fig. S13). Considering the high purity requirements of products in the pharmaceutical industry for fine chemicals, we ensured complete conversion of NBT to guarantee product purity. As shown in Fig. 2f, there is a linear growth of the productivity in over 250 hours of reaction, i.e., the reaction rate remains constant at a value of 3.9 mmol·gcatal−1h−1. In addition, the 5-amino benzothiazole (ABT) selectivity remains constant and exceeds 99%, as verified by 1H and 13C NMR results, resulting in a calculated yield of 94%. (Supplementary Fig. S14). Therefore, in over 250 hours of continuous experiments, there are no signs of deactivation, and the catalytic performances remain stable. Remarkably, a total of 145 kg·kgPt−1 of pure 5-amino benzothiazole is produced in 250 hours of continuous flow conditions, showing the high productivity of the catalyst and its industrial relevance. The HAADF-STEM images of the spent catalyst (Supplementary Fig. S15) demonstrate that the Pt single atoms and clusters remain uniformly dispersed on the CeO2 support, maintaining a distribution pattern comparable to that of the fresh catalyst. Furthermore, ICP analysis reveals that the leaching of active metal species is negligible, with no significant loss of Pt content detected (0.49% vs. 0.45%). These comprehensive characterization results collectively confirm the exceptional structural and compositional stability of our catalyst system under reaction conditions.

In contrast to other nitro-containing compounds, NBT is a unique molecule that contains both a sulfur atom and a nitro group. Sulfur has a stronger coordinating ability than the nitro group. S preferentially strong chemisorb on metal surfaces, poisoning the metal sites. This strong chemisorption inhibits the activation of other unsaturated groups (such as the nitro groups) on the metal surface. Commercial Pt/C, as an example of strong hydrogen dissociation capabilities, shows high activity in nitro and C = C bond hydrogenation reactions in the absence of sulfur. However, the Pt/C exhibits almost no activity in NBT hydrogenation. Similarly, when benzothiazole is added, Pt/C activity in the hydrogenation of nitro and cyclohexene is completely inhibited (Supplementary Fig. S16), further confirming the sulfur poisoning effect on the Pt surface. On the other hand, these tests also indicate that the activation of C = C bonds and nitro groups primarily occurs on the Pt surface for Pt/C catalysts, which is in agreement with the literature indications.

Pt/CeO2-300 behaves differently from Pt/C and other Pt-based supported catalysts, maintaining a high and constant activity in the presence of compounds containing sulfur. There is, thus, a different mechanism of activation of the nitro groups. This indication is demonstrated by poisoning experiments, where the effect of the poison/substrate ratio for different poisons (thiazole - TZ, benzothiazole - BTZ and thiophene - TP) was analyzed in the Pt/CeO2-300 catalyzed hydrogenation of C = C and nitro compounds (Fig. 3). In the hydrogenation of cyclohexene, the addition of 0.2 molar equivalents of benzothiazole completely deactivated the catalyst. The Pt sites responsible for activating C = C are occupied by sulfur-containing species, preventing the activation of C = C and thereby impeding the progress of the reaction (Fig. 3a, b). In the hydrogenation of NBT, three different poisons (benzothiazole, thiazole, and thiophene) were introduced.

Poisoning experiments (effect of the poison/substrate ratio) and the scheme of the mechanism of the Pt/CeO2-300 catalyst after being poisoned during the hydrogenation of cyclohexene (a, b) and 5-nitro benzothiazole. c–h Poisoning agents are thiazole (TZ), benzothiazole (BTZ), and thiophene (TP). The dotted lines correspond to the lowest activity maintained or the lowest relative conversion. All initial reaction activities without poison are less than 100%.

The results of the poisoning experiments showed the conversion is not or minimally affected (maintained over 90%, see Fig. 3c–h) regardless of the type of S-containing poisons and the BTZ/poisons ratio. Based on the control experiments in the hydrogenation of NBT catalyzed by Pt/CeO2-300, the activation site for nitro groups is not the metal Pt but possibly the Pt-Ov-Ce interface or the Ov on the CeO2 support. In earlier studies, we observed that Pt/CeO2-C (e.g., on commercial CeO2) exhibited excellent hydrogen dissociation ability and showed the presence of Pt-Ov-Ce interface, but is inactive in the NBT hydrogenation. Therefore, in this system (Pt/CeO2-300), the activation site for nitro groups is suggested to be the active Ov site on the ceria surface, while Pt is responsible for hydrogen dissociation. Herein, nitro hydrogenation can only occur when active hydrogen species migrate from the metal to the activated nitro group through hydrogen spillover generation and surface mobility over the oxide40,41,42.

The hydrogen spillover ability was evidenced by a color change in the WO3 experiment (Supplementary Fig. S17). The proposed mechanism is thus based on three surface processes: (i) hydrogen dissociation on Pt species (activity maintained even in the presence of strong poisoning by S), (ii) nitro group activation on Ov, and (iii) surface migration of active hydrogen species (spillover) from the Pt nanoparticles to the activated nitro group where the nitro groups are converted to amino groups.

Recognition of nitro groups by active sites

Further experiments were conducted to prove the proposed mechanism and better understand the question of which type of nitro substrate will preferentially activate on the Ov rather than the Pt over the Pt/CeO2 catalyst. We compared different nitro-containing molecules with different geometric and electronic structures. Abundant active oxygen vacancies characterize Pt/CeO2-300, while Pt/CeO2-C has a minimal amount of active oxygen vacancies, as shown by H2-O2 titration. Pt/CeO2-300 has both oxygen vacancies and Pt metal sites as bifunctional sites, while Pt/CeO2-C has only metal sites. The comparison of their behavior in different nitro-containing molecules allows us to obtain valuable information on the difference between single (e.g., the metal nanoparticles in Pt/CeO2-C) versus dual sites (metal cluster and Ov in Pt/CeO2-300).

After introducing a poison to deactivate the metal, hydrogen activation can still occur on the metal surface because hydrogen molecules are much smaller than the poison molecules. Taking the example of cyclohexene hydrogenation, which can only occur on the metal surface43, both Pt/CeO2-300 and Pt/CeO2-C showed comparable activity before poisoning. However, after the introduction of the poison, both Pt/CeO2-300 and Pt/CeO2-C were deactivated, demonstrating that the added poison was sufficient to cover the metal surface (Supplementary Fig. S18). This evidence further confirms that C = C double bonds can only be activated on Pt. The introduction of poisons completely covers the metal sites and prevents unsaturated groups from accessing the Pt sites.

As for the activation of nitro group, Pt/CeO2-300 and Pt/CeO2-C had comparable catalytic activity before poisoning when nitrobenzene was used as the reactant (Fig. 4a). The KIE value for the Pt/CeO2-300 is about ~ 1 (Supplementary Fig. S19), indicating the hydrogen dissociation does not participate in the rate-determining step and activation of nitro group is likely the rate-determining step. After the addition of the poisoning agent, Pt/CeO2-300 retained ~ 10% of its catalytic activity, while Pt/CeO2-C was completely deactivated. Similar to the hydrogenation and poisoning rules of cyclohexene, the nitro group of nitrobenzene is mainly activated and converted on the metal Pt.

a–d Comparison of the catalytic activity in the hydrogenation of nitrobenzene and its derivatives before and after poisoning with thiazole (TZ). e–h Comparison of the catalytic activity in the hydrogenation of nitro benzoxazole (NBX), 2-nitro naphthalene (NN), and 9-nitro anthracene (NA) and nitro benzothiazole (NBT) before and after poisoning with benzothiazole (BTZ). All reactions were carried out under conditions where poison/substrate = 0.3:1, ensuring the comparability of activation for both substrate and poison. A reaction temperature of 60–80 °C and a hydrogen pressure of 1-2 MPa ensure that hydrogenolysis does not participate in the rate-determining step.

To investigate the effect of electronic structure, we introduced electron-donating methyl and hydroxyl groups and electron-withdrawing carbonyl groups in the para and ortho positions of nitrobenzene. After TZ addition (as a poisoning agent), Pt/CeO2-300 retains about 10% activity in nitro group reduction for all the different substituents, whereas Pt/CeO2-C is fully deactivated (Fig. 4b–d). These results indicate that in nitrobenzene hydrogenation, the hydrogenation of nitro is mainly carried out at the metal Pt site and is not limited by substituents.

Further tests to investigate the geometric structure were made by analyzing three substrate molecules with different kinetic sizes: nitro benzoxazole (NBX, 4.31 × 7.84 Å), 2-nitron naphthalene (NN, 5.00 × 8.13 Å), and 9-nitro anthracene (NA, 6.11 × 9.32 Å), were chosen initially (Fig. 4e–h). Due to steric hindrance, the nitro group reduction activity was significantly lower than that of NB. In the hydrogenation of NBX, after introducing benzothiazole poison, the activity for the Pt/CeO2-300 catalyst was sustained at approximately 40% of the original activity. In this case, there is a significantly different behavior compared to the complete deactivation observed for nitrobenzene. This result implies that despite both involving nitro group hydrogenation, the potential difference in active sites might contribute to this variation.

When using NN (having a large conjugated system size) as the reaction substrate, the conversion was maintained at about 60% after benzothiazole poison addition. Expanding the conjugated ring size to NA, the conversion remains at about 70% because it takes place on the Ov site. When sulfur-containing nitro molecules are introduced, and the accessibility of the metal is completely inhibited, the activation of the nitro group occurs entirely on the Ov site. Results from a series of control experiments demonstrate that the recognition of Pt/CeO2-300 active sites by nitro substrate molecules is primarily influenced by the geometric structure and poison effect of the molecules connected to the nitro group. This transition, from benzene to naphthalene to anthracene, shifts from the metal to Ov site, the place of activation/reduction of the nitro groups, in turn affecting the inhibition effect by S-containing species.

XPS results of Pt/CeO2-300 adsorbing NB and NBT provide further evidence for our mechanistic indications. As evident from Supplementary Fig. S20, we observed comparable Pt 4 f binding energy (BE) for the initial Pt/CeO2-300, Pt/CeO2-300-NB, and Pt/CeO2-300-NBT. This similarity is likely attributed to the low exposure of the Pt surface and the XPS-derived Pt 4 f BE representing an average value across the surface to a depth of less than 10 nm, inclusive of a minor amount of NB/NBT. Upon comparing Pt/CeO2-300, we noted a significant decrease in the Ov content from 14% to 4.8% after chemical adsorption of NB and NBT (Fig. 5a). In detail, the oxygen vacancy content of Pt/CeO2-300 + NBT decreased by 66%. In comparison, that of Pt/CeO2-300 + NB only decreased by 34% (Fig. 5b). Such a clear trend further confirms the difference in nitro activation sites. Compared with NB, the nitro group of NBT molecules is activated on Ov.

a O 1 s XPS spectra of Pt/CeO2-300 catalyst chemically adsorbed substrates NB and NBT, respectively. b Variation in the concentration of oxygen vacancies on the surface of Pt/CeO2-300 catalyst after adsorption of different substrate molecules. c, d Calculated adsorption energy of various nitro-substrates on Pt cluster and Ov, respectively. eThe relationship between Pt accessibility and nitro activation site. f Schematic diagram of nitro group activation site selection for different nitro-substrate molecules on the Pt/CeO2-300 catalyst.

Theoretical support for the proposed mechanism

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations were employed to examine the adsorption energy discrepancy of nitro compounds between CeO2 planes featuring oxygen vacancies (Ov) and the Pt sub-nano cluster surface. As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S21, for NBT molecules adsorbed on Pt clusters, irrespective of whether they adopt a standing or lying-down configuration, sulfur exhibits a markedly stronger adsorption affinity compared to the nitro group. This observation implies that sulfur effectively occupies the sites crucial for nitro group activation on the metallic surface. Consequently, this finding rationalizes why most single-site Pt-based catalysts fail to facilitate the hydrogenation of nitro compounds containing sulfur atoms even under harsh conditions.

Thus, it is reasonable to infer that the nitro groups of NBT primarily occupy Ov sites of the Pt/CeO2 catalyst for activation. The results of the DFT calculations revealed that a vertical adsorption mode on the oxygen vacancy site activates the nitro group of NBT. The adsorption energy is − 3.06 eV, which is higher than that on the metal surface (− 2.52 eV). Therefore, the Pt/CeO₂-300 catalyst, with its abundant Ov, exhibits a particularly strong adsorption capacity for NBT. In contrast, for other nitro molecules devoid of sulfur atoms (depicted in Fig. 5c), the constraints imposed by the limited size of Pt clusters predispose these molecules towards a lying adsorption mode for nitro group activation. Notably, as the molecular size escalates from NB to NA, there is a gradual decline in the adsorption energy of the nitro group in the standing configuration on the Pt surface. Conversely, the adsorption energy of the nitro group in the lying configuration on the Ov surface incrementally rises along the same series. This divergent trend in adsorption energy variations for the nitro group on the Pt surface versus Ov aligns with experimentally identified activation sites, reinforcing our experimental conclusions. Hence, during the hydrogenation progression from NB to NBT, the reduced accessibility to Pt prompts a shift in the activation site for the nitro group from the metal surface to Ov, as schematically represented in Fig. 5d.

In the case of the dual-site Pt/CeO2 catalyst, which contains both Pt sub-nano cluster and Ov sites, the accessibility of Pt sites plays a crucial role in determining the activation site of the nitro group (Fig. 5e). When the molecule connecting the nitro group is smaller, the accessibility of the Pt site is high, leading to the preferential activation of the nitro group at the metal site. As the size of the substrate molecule increases, the accessibility of Pt decreases. Consequently, the activation site for the nitro group shifts gradually from being metal-dominated to Ov-dominated. When the substrate molecule contains a stronger adsorption group like sulfur, the accessibility of the metal is nearly zero, and the nitro group can only be activated in the Ov site, as shown in the mechanism diagram reported in Fig. 5f.

Discussion

A catalyst based on highly defective CeO2 on which Pt nanoclusters are deposited was synthesized to develop dual sites catalysts combining high-activity of surface oxygen vacancies (Ov) in nitro group reduction and Pt nanoclusters acting as sites for generating spillover H that migrate to the nitro groups coordinated to Ov to reduce them. Extensive characterization and kinetic/poisoning experiments have proven these indications and how this mechanism allows an efficient and stable behavior in reducing S-containing nitroarenes.

In the hydrogenation reaction of nitrobenzothiazole (e.g., containing sulfur), the Pt/CeO2-300 has significantly higher activity compared to other catalysts and the reference Pt/CeO2-C catalyst. Poisoning experiments with sulfur-containing molecules confirmed that the activation of nitro groups in these molecules exclusively occurs on Ov. For nitrobenzene and its derivatives with different substituents, 90% of nitro activation occurred at the metal sites. The electronic structure and reactivity of the aromatic ring (due to substituents) did not affect the nitro group reducibility and the effect of S-poisoning. As the conjugated structure of the benzene ring increases from benzene to benzothiazole, naphthalene, and anthracene, there is a gradual transition of the nitro activation site from the metal site to the Ov site. When the nitro-containing molecule also contains sulfur, the nitro group is entirely activated by the oxygen vacancies. We propose that molecular recognition of nitro reduction sites primarily depends on the accessibility of metal Pt, which is mainly related to the size of conjugated structures linked to the nitro group and the presence of poison elements, especially sulfur.

In conclusion, the results prove that the strategy based on a dual-site catalyst for the hydrogenation of S-containing nitroarenes (i) is effective, leading to highly active and stable catalysts with superior performances of industrial relevance, (ii) is preferable over those based on covering the metal particles by a thin oxide layer, (iii) offers new possibilities in designing new catalysts exploiting a similar dual-site strategy. In addition, the molecular recognition of nitro reduction sites offers new clues for designing innovative catalysts.

Methods

Preparation of CeO2

Defect-rich CeO2 was synthesized by the urea precipitation method. Specifically, 19.73 g of Ce(NO3)2·6H2O (45 mmol) and 27.27 g of urea (450 mmol) were dissolved in 200 mL of deionized water. The solution was heated to 80 °C and refluxed for 12 h. After cooling naturally to room temperature, the solution was filtered, washed three times with deionized water, and dried at 80 °C. The sample was dried in a muffle and then dried in a water bath. The dried sample was calcined in a muffle furnace at 350 °C for 4 h to obtain CeO2.

Preparation of Pt/CeO2-T and Pt/CeO2-C

Pt/CeO2-T catalysts were prepared through a conventional impregnation method with a metal content of 0.5 wt%. In a typical process, commercial CeO2 or as-synthesized CeO2 (300 mg) was dispersed in H2PtCl6 aqueous solution (3.0 mL,1.5 mg Pt). The slurry was stirred at room temperature for 12 h and then dried at 60 °C for 12 h. The powder product was reduced under H2 at 300 and 450 °C for 2 h with a heating rate of 3 °C min−1. The gray powder catalysts were denoted as Pt/CeO2-T (T refers to the reduction temperature).

Catalytic hydrogenation activity test

The hydrogenation reactions were carried out in a stainless-steel autoclave (300 mL) with a thermos couple-probed detector. In a typical reaction,10 mg 5-nitro benzothiazole, 10 mg catalyst, and 3 mL ethanol were placed in a 5 mL ampule tube, and then the ampule tube was loaded into the reactor. After the reactor was purged five times with H2, the final pressure was adjusted to 2 MPa, and the reactor was heated to 80 °C with vigorous stirring. After the reaction, the reaction mixture is diluted with ethanol, filtered for collection, and analyzed using an Agilent 7890B GC instrument equipped with an Agilent HP-5. The experiment of adding a poison agent was carried out in the same reactor, using ethanol as a solvent and adding the corresponding substrate and poison agent. The reaction products were diluted with ethanol and analyzed by gas chromatography. The D2-kinetic isotope experiment uses the same method to test catalytic activity, only replacing H2 with D2.

Hydrogenation stability of 5-nitro benzothiazole was performed in a high-pressure fixed-bed reactor (EMC-3, Oushisheng company). Typically, before the reaction, a 1.400 g catalyst with grain sizes of 40–60 mesh was loaded in the reactor. Then, a solution of 5-nitrobenzothiazole in ethanol (5 mM) as mobile phase was fed into the reactor at a given flow rate of 5.4 mL h−1; meanwhile, the high-purity H2 was fed into the reactor at 2.0 MPa and 80 °C. The outflow from the column reactor was sampled for gas chromatography (GC).

The sources of chemical reagents, detailed characterization methods and the density functional theory (DFT) calculations are provided in the supplementary material.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. All other relevant raw data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided in this paper.

References

Wang, C. et al. Insight into single-atom-induced unconventional size dependence over CeO2-supported Pt catalysts. Chem. 6, 752–765 (2020).

Deng, P. et al. Atomic insights into synergistic nitroarene hydrogenation over nanodiamond-supported Pt1-Fe1 dual-single-atom catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202307853 (2023).

Wu, Q. Y. et al. Full selectivity control over the catalytic hydrogenation of nitroaromatics into six products. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202408731 (2024).

Chen, G. et al. Interfacial electronic effects control the reaction selectivity of platinum catalysts. Nat. Mater. 15, 564–569 (2016).

Zhong, Y. et al. Locking effect in metal@MOF with superior stability for highly chemoselective catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 4659–4666 (2023).

Corma, A. & Serna, P. Chemoselective hydrogenation of nitro compounds with supported gold catalysts. Science 313, 332–334 (2006).

Song, J. et al. Review on selective hydrogenation of nitroarene by catalytic, photocatalytic and electrocatalytic reactions. Appl. Catal. B 227, 386–408 (2018).

Wang, N., Saidhareddy, P. & Jiang, X. Construction of sulfur-containing moieties in the total synthesis of natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 37, 246–275 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Cooperation of Pt and TiOx in the hydrogenation of nitrobenzothiazole. ACS Catal. 12, 11369–11379 (2022).

Layek, K. et al. Gold nanoparticles stabilized on nanocrystalline magnesium oxide as an active catalyst for reduction of nitroarenes in aqueous medium at room temperature. Green. Chem. 14, 3164–3174 (2012).

Qu, R., Junge, K. & Beller, M. Hydrogenation ofcarboxylic acids, esters, and related compounds over heterogeneous catalysts: A step toward sustainable and carbon-neutral processes. Chem. Rev. 123, 1103–1165 (2023).

Iemhoff, A., Vennewald, M. & Palkovits, R. Single-atom catalysts on covalent triazine frameworks: At the crossroad between homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202212015 (2023).

Pu, T., Zhang, W. & Zhu, M. Engineering heterogeneous catalysis with strong metal–support interactions: characterization, theory and manipulation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202212278 (2023).

Mori, K., Hata, H. & Yamashita, H. Interplay of Pd ensemble sites induced by GaO modification in boosting CO2 hydrogenation to formic acid. Appl. Catal. B 320, 122022 (2023).

Meng, F. et al. Shifting reaction path for levulinic acid aqueous-phase hydrogenation by Pt-TiO2 metal-support interaction. Appl. Catal., B 324, 122236 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Pt3Ti Intermetallic alloy formed by strong metal–support interaction over Pt/TiO2 for the selective hydrogenation of acetophenone. ACS Catal. 13, 4030–4041 (2023).

Ma, Y. et al. High‐density and thermally stable palladium single-atom catalysts for chemoselective hydrogenations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 21613–21619 (2020).

Jin, H., Song, W. & Cao, C. An overview of metal density effects in single-atom catalysts for thermal catalysis. ACS Catal. 13, 15126–15142 (2023).

Ren, Y., Yang, Y. & Wei, M. Recent advances on heterogeneous non-noble metal catalysts toward selective hydrogenation reactions. ACS Catal. 13, 8902–8924 (2023).

Macino, M. et al. Tuning of catalytic sites in Pt/TiO2 catalysts for the chemoselective hydrogenation of 3-nitrostyrene. Nat. Catal. 2, 873–881 (2019).

Guo, M. et al. Improving catalytic hydrogenation performance of Pd nanoparticles by electronic modulation using phosphine ligands. ACS Catal. 8, 6476–6485 (2018).

Corma, A. et al. Transforming nonselective into chemoselective metal catalysts for the hydrogenation of substituted nitroaromatics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 8748–8753 (2008).

Liu, X. et al. Regulation of the properties of hydrogen dissociation and transfer in the presence of S atoms for efficient hydrogenations. ACS Catal. 14, 16214–16223 (2024).

Yu, J. & Jiang, X. Synthesis and perspective of organosulfur chemicals in agrochemicals. Adv. Agrochem. 2, 3–14 (2023).

Huang, X. et al. Ceria-based materials for thermocatalytic and photocatalytic organic synthesis. ACS Catal. 11, 9618–9678 (2021).

Ma, J. et al. High-dispersed CeOx species on mesopores silica to accelerate Ni-catalyzed CO2 methanation at low temperatures. Chem. Eng. J. 479, 147453 (2024).

Yue, G. C. et al. Boosting chemoselective hydrogenation of nitroaromatic via synergy of hydrogen spillover and preferential adsorption on magnetically recoverable Pt@FeO. Small 19, 2207918 (2023).

Rajendran, K. & Jagadeesan, D. Harnessing the oxygen vacancies in metal oxides for nitroreduction. Chem. Cat. Chem. 16, 202301647 (2024).

Yuan, Z. et al. Synergy of oxygen vacancies and base sites for transfer hydrogenation of nitroarenes on ceria nanorods. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl. 63, e202317339 (2024).

Geng, L. et al. Electronic modulation induced by oxygen vacancy creating in copper oxides toward accelerated hydrogenation kinetics of nitroaromatics. Appl. Catal. B 343, 123575 (2024).

Zhou, X. et al. Enhancing nitrobenzene reduction to azoxybenzene by regulating the O-vacancy defects over rationally tailored CeO2 nanocrystals. Appl. Surf. Sci. 572, 151343 (2022).

Chang, K. et al. Application of ceria in CO2 conversion catalysis. ACS Catal. 10, 613–631 (2019).

Humphreys, J. et al. Cation doped cerium oxynitride with anion vacancies for fe-based catalyst with improved activity and oxygenate tolerance for efficient synthesis of ammonia. Appl. Catal. B 285, 119843 (2021).

El Fallah, J. et al. Redox processes on pure ceria and on Rh/CeO2 catalyst monitored by X-ray absorption (Fast Acquisition Mode). J. Phys. Chem. 98, 5522–5533 (1994).

Kopelent, R. et al. Catalytically active and spectator Ce3+ in ceria-supported metal catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 8728–8731 (2015).

Ren, X. et al. Development of efficient catalysts for selective hydrogenation through multi-site division. Chin. J. Catal. 62, 108–123 (2024).

Zhang, Q. X. et al. Pd/oCNT Monolithic catalysts for continuous-flow selective hydrogenation of cinnamaldehyde. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 6, 8868–8879 (2023).

Liu, P. X. et al. Photochemical route for synthesizing atomically dispersed palladium catalysts. Science 352, 797–801 (2016).

Ren, X. et al. Efficient production of nitrones via one-pot reductive coupling reactions using bimetallic RuPt NPs. ACS Catal. 10, 13701–13709 (2020).

Kang, H. et al. Generation of oxide surface patches promoting H-spillover in Ru/(TiOx)MnO catalysts enables CO2 reduction to CO. Nat. Catal. 6, 1062–1072 (2023).

Wei, X. et al. High performance polyoxometalate-stabilizing Pt nanocatalysts for quinoline hydrogenation with water-mediated dynamic hydrogen. ACS Catal. 14, 5344–5355 (2024).

Kang, H. et al. Oxygen vacancy-dependent chemical intermediates on Ru/MnO catalysts dictate the selectivity of CO2 reduction. Appl. Catal. B 352, 124010 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. Selective hydrogenation over supported metal catalysts: From nanoparticles to single atoms. Chem. Rev. 120, 683–733 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the NSFC of China (Nos. 22472168 and 22172161 to Y.L., 22302027 to X.R.), the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (2024-MSBA-57 to Y.L.), the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (DICP I202421 to Y.L.), the Foundation of Dalian Youth Science and Technology Star Project (2022RQ030 to X.R.), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Provincial Universities of Liaoning (LJ242410150017 to X.R.). S.P. and G.C. also thank the support from the CAS President’s International Fellowship Initiative (PIFI) program and the SCOPE ERC Synergy project (ID 810182).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. and X.R. conceived the idea. X.R. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. J.H. carried out the synthesis, characterization, and performance measurements. J.M. conducted XAS and TEM measurements and the data analysis. Y.L. performed atomic resolution STEM measurements. Y.Z., W.C., S.P., and G.C. participated in the discussion of the study and revised the manuscript. Y.L. directed the research. All authors contributed comments on this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Alexis Bordet, Zhen-Yu Tian, and Yong Zhao for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ren, X., Huang, J., Ma, J. et al. Boosting the activity in the liquid-phase hydrogenation of S-containing nitroarenes by dual-site Pt/CeO2 catalysts design. Nat Commun 16, 4851 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59920-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59920-x