Abstract

Topological photonic structures have great potential to revolutionize on-chip optical integration due to the merit of robust propagation. However, an equally important issue, i.e., the efficient input and output coupling of topological structure with other elements, has not been systematically addressed. Here, we reveal that the coupling of topological photonic structures does not follow the mode matching principle widely used before, but follows the principle of transverse spin matching (TSM). According to this mechanism, efficient coupling between a topological waveguide (TWG) and a strip waveguide (SWG) is designed theoretically and demonstrated experimentally. Theoretical and experimental transmission efficiencies of 96.3% and 94.2% are respectively obtained, which are much larger than those obtained before. The TSM enabled efficient topological structure coupling guarantees a high overall energy efficiency, and paves the way for compact topological photonic chips.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Topological photonics has opened a new chapter for integrated optical science and technology because it has revolutionized the manipulating of light propagation1,2,3,4,5,6. In particular, topological photonic crystal waveguide will be competitive candidates in the on-chip integration of optical devices due to the robustness to a certain degree of defects, efficient propagation through bending angles, and multi-degree of freedom information encoding abilities7,8,9,10,11. For example, topological waveguides (TWGs) have been used to develop diverse topo-devices successfully for on-chip application, including optical delay lines12, beam splitters13,14,15,16, photonic switch17,18, cavities19,20, and lasers21,22,23,24,25.

Although the transmission efficient of light inside a single TWG is high, it is inevitable for light to input to and output from it in order to construct larger scale functional devices. Unfortunately, up to now, the maximum transmission efficiencies for practical TWGs are less than 80% for TWGs with flat interface and triangular holes3. For the bearded interface with circular air holes, the maximum transmission efficiency is lower than 25% even after the optimization of the inserted waveguides, which greatly weakens the intrinsic transmission merit of topological photonic structures. More details about current TWG coupling method are shown in Supplementary Note 1.1. Therefore, exploring the universal coupling mechanism between topological structures is one of the main challenges in the development of large scale topological optical chips.

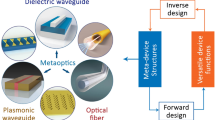

In this work, we demonstrate both theoretically and experimentally that transverse spin matching (TSM) is the universal mechanism for efficient coupling related to TWGs, as illustrated in Fig. 1. We also reveal that the widely used mode matching26,27,28 is not the sole method for achieving high transmission efficiency. The rigorous conditions imposed by mode matching are not indispensable, and TSM can offer a relaxed yet effective criterion. Even when the modes are orthogonal, TSM still can ensure a high transmission efficiency.

a Mode matching (MM) for the interconnection of two different slab waveguides (WG). For the ordinary two-dimensional slab waveguide coupling with widths W1 and W2, the waveguide coupling mechanism is more accurately described by vector mode matching (VMM). The rule of vector mode matching is the input and output interface vector mode profile matching. In order to match the mode profile, an optimized taper can be used to tune the mode profile adiabatically, and enhance the transmittance (T = 1). In fact, for the sake of simplicity, only complex electric field amplitude is usually considered in mode matching. b Transverse spin matching (TSM) for the coupling of a slab waveguide and a topological waveguide (TWG). b1 Although the vector mode matching degree at positions P1 and P2 is very low to α(P1P2) ~ 0 (Eq. (1)), the TS matching degree of is up to β(P1P2) ~ 0.6 (Eq. (3)), which results in T ~ 0.8. This phenomenon hints that the mode matching principle is not suitable for the design of topological structure coupling. b2 An optimized coupler tunes the TS profiles and gradually enhances the matching degree of TS from 0.6 (P1) to 1 (P4). As a result, a high transmittance T ~ 1 is obtained.

For the coupling of two ordinary slab waveguides (Fig. 1a), the mode matching is usually considered29,30, which is defined by the overlap integration of the two vector modes, i.e.,

where E = (Ex, Ey, Ez) is the vector electric field intensity, and both the spatial distribution and vector polarizations are considered. In case of α = 1, the input and output modes are perfectly matched for all the three Cartesian components. When α = 0, a zero transmittance of T = 0 is expected. In the planar waveguide with TE mode, E1 and E2 have nonzero components of Ex and Ey4,31,32, and vector mode matching requires Ex and Ey components to be matched simultaneously, as shown in Fig. 1(a). In fact, when E1 and E2 are along the same direction, it can be reduced to the case of scalar mode matching, as illustrated in Fig. 1(a).

However, we find that the mode matching principle widely used before are not suitable for the coupling of a two-dimensional (2D) slab WG with a 2D TWG shown in Fig. 1(b). Here, since we’re using a 2D model, the integral in Eq. (1) is performed along the y-axis only. Results show that the mode profiles of the incident slab WG at position P1 and that of the TWG at position P2 are orthogonal, and the degree of mode matching α is about 0 according to Eq. (1). However, the transmission efficiency is found to be as high as T = 0.8, but not zero. This clearly shows that the mode matching principle is inconsistent with the transmission efficiency of TWGs, although it can be used to get a rather high transmission efficiency in some specific cases3,4,17,19,33.

Recent studies have established a fundamental relationship between transverse spin (TS) angular momentum and the Poynting vector P, where TS is locked to the direction of energy flow propagation in the waveguide mode (TS-momentum locking34,35,36). This connection implies that the distribution of transverse spin is directly tied to the characteristics of the energy flow within waveguide modes, and vice versa. Specifically, the transverse spin distribution of a unidirectional transmission waveguide mode corresponds to its unique energy flow. Conversely, by customizing the transverse spin distribution, it is possible to excite the corresponding unidirectional transmission waveguide mode.

Therefore, from the perspective of TS, one can find that the TSs at P1 and P2 are matching to some degree. When we optimize the incident slab WG to tune the matching degree of TS gradually from 60% to ~100%, as shown in Fig. 1(b2), a very high transmission efficiency ~100% can be obtained. The mode matching degree α in P4 is 0.892, indicating that perfect mode matching is not a necessary condition for efficient coupling of topological modes. Instead, transverse spin matching utilizes spin-momentum locking to achieve unidirectional propagation of energy flow by exciting a specific transverse spin distribution at the coupling plane. Unlike traditional mode matching mechanisms, this approach explores the dynamics of coupling between different modes from the perspective of momentum and reveals the unique phenomenon of transverse spin and momentum evolution. A detailed distinction and relationship between the insertion waveguide coupling scheme and the transverse spin matching scheme are provided in Supplementary Note 1.1.3. In addition, since the transverse spin is a universal property independent on the specific structure, the method can be extended to any other topological structures (See Supplementary Note 1.1 for details).

According to the phenomenon described above, we propose the TSM to address the coupling issue of topological photonic structures, which allows nearly perfect coupling between a practical strip waveguide (SWG) and a TWG slab, and a theoretical transmission efficiency of 96.3% and experimental efficiency of 94.2% are obtained, which are much larger than those reported before. This principle solved the coupling issue of topological structures and may promote the rapid development of transverse-spin-matched nanophotonics and large-scale TWG based photonic systems.

Results and discussion

Principle of transverse spin matching

We use the structure shown in Fig. 2(a) to analysis the principle of TSM. The incident SWG is made of silicon with a width D and height h. The TWG is formed by air hole pairs in a silicon slab, and the radius of big/small holes are 110 nm and 55 nm, respectively. This structure has been widely used in the investigation of diverse topological devices1,7. The band structure and topological protected eigen mode can be numerically calculated using the finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) method. The TSM is derived from the intrinsic relationship between the transverse spin and the propagation direction in nanophotonic devices34,37.

a Schematic of coupling structure. The width of the SWG is D. The thicknesses of the waveguides are h. The TWG is formed by air holes with radiuses of 110 nm and 55 nm according to honeycomb lattice with lattice constant of a0. A, B, and B’ are three typical positions to analyze the TS patterns. b, c Distributions of the TSs in the SWG near the position A, and in the TWG near the positions B and B’ with a separation of 0.5a0. d Changes of T and the degree of TSM β with the central position ycenter of the incident SWG at the fixed width of D = 1.2 μm. e Comparing STWGz with SSWGz when ycenter = −0.21 μm and 0.36 μm, from which the TSM can be observed intuitively.

A guiding mode propagating in the x direction has both transverse and longitudinal components of electric field38. The longitudinal and transverse electric fields always have a phase difference of π/2, which results in an elliptically polarized electric field and thus carries a TS37,39,40,41,42. Also, the TS has unique distributions for the strip and topological waveguide, since the eigenmodes of them are different. The transverse spin is defined as

Here, Sz0 is a normalization coefficient to make the maximum of Sz = 1. For the TE mode, the other components of the transverse spin are 0, since Ez ≡ 0. The sign and amplitude of Sz are sensitively related to the direction of light propagation37, which is widely known as spin-momentum locking4,43. That’s to say, the sign of TS is closely related to the propagation direction of the topological mode. Therefore, it’s highly desired to define the degree of TSM to quantitatively demonstrate the matching of difference of TS distribution. More details about the band structure and propagation features are shown in Supplementary Note 1.2. The above analysis considers the transverse spin of the TE mode, which can be extended to the TM mode directly. The only difference between them is that the former is calculated using the electric fields, while the latter is calculated using the magnetic fields31.

Since TS is directly related to the direction of propagation and thus affects the transmission efficiency, the signed value of TS should be used (but not the absolute value). According to this point, the matching degree of TS is defined as

where SSWGz(y, z) and STWGz(y, z) are the TS at the coupling plane of the SWG and TWG, respectively. The integral region is the cross-section of the topological waveguide, as shown in Fig. 2a. Here, the selection of the integral region considers the lateral size of the waveguide mode and the topological mode. It can be found that the value range of β is [−1,1]. When SSWGz = STWGz, β = 1, which is the case of perfect TSM. The input energy should be coupled into the TWG perfectly. However, when SSWGz = −STWGz and β = −1, the energy should propagate to the back direction (i.e., reflection) according to the analysis above. In this case, the transmission will be zero, which is analog to the case of orthogonality in mode matching. The difference of Eqs. (1) and (3) clearly show the distinct physics of mode matching and transverse spin matching. The main target of TSM is to make β equal (or close to) 1, which is affected by several parameters shown below.

First is the position of coupling. As shown in Fig. 2(b), (c), although TS in the SWG is independent on x, it changes periodically in the TWG, which results in β being sensitively related to the coupling position. For example, for the positions B and B’ with a separation of \(0.5{a}_{0}\), the difference between \({{{\rm{TS}}}}({x}_{B},y,z)\) and \({{{\rm{TS}}}}({x}_{B^{\prime}},y,z)\) can be observed obviously. Actually, the matching degree of them is only about 0.3 according to Eq. (3). Without loss of generality, we select the position B as an example in the following discussions, and it can be extended to any other coupling positions straightly, such as position B’, in the process of optimization.

Second, when the coupling position B is determined, the width D and position (ycenter) of the input SWG are also vital in order to fulfill the TSM condition. Here, we set D = 1.2 μm as an example, which is a similar width to the effective width of the TWG. When we shift the waveguide transversely, the maximum (53.5%) and minimum (26.3%) transmissions occur at ycenter = −0.21 μm and ycenter = 0.36 μm, respectively, as shown in Fig. 2(d). One can find that a larger transmission T always corresponds to a larger β, which agrees to our principle of TSM. There is a slight discrepancy between the transmittance T and β, which is due to the scattering of light by the coupling interface. Figure 2(e) compares the distributions of TS inside the SWG and TWG at ycenter = −0.21 μm and ycenter = 0.36 μm, from which the matching degrees of TS can be understood intuitively. More details about the position of coupling and width D are shown in Supplementary Note 1.4.

Nearly perfect coupling based on TSM

According to the analysis above, one should optimize the input SWG to give out a TS distribution that matches the position B. Also, the optimization target should be replaced when the coupling position or topological waveguide type is changed. For this purpose, the widely used adiabatic mode convertor, such as the taper shown in Fig. 1(a), is not suitable. Recently, using mathematical optimization algorithm to design photonic devices has been widely studied44,45,46,47,48. Among them, genetic algorithm (GA), as a method good at global optimization, has attracted great attention in the design of various nanophotonic devices46,49,50. Therefore, we use GA to optimize the SWG. When data sets become large (such as the number of discrete pixels of the coupler is large), reverse design strategy (such as adjoint method48,51,52 or the level set method45,53) should be introduced to achieve optimal targets more rapidly and efficiently.

We limit the length of the convertor to be 0.8 μm in order to make the coupler compact, and the coupling area of 1.2 × 0.8 μm2 is discretized into 12 × 8 pixels. That’s to say, each pixel is a square with side length of 100 nm, which is selected according to the fabrication precision in the subsequent experiment. The material of each pixel can be air or silicon, which is determined by the GA optimization. The degree of TSM β is selected as the fitness function in optimization, which is nearly 10 times faster than the direct optimization of T. More details on GA, optimization steps, and results are provided in Supplementary Note 1.5. The final result of the optimization is shown in Fig. 3. Before (the initial generation) and after (the 15th generation) the optimization, the distributions of TS are shown in Fig. 3(a1), (a2), respectively. Clearly, the latter matches very well with the target TS distribution, and the degree of matching reaches to 0.843 according to Eq. (3). Moreover, the relationship between β and T is nearly linear in the optimization process (see Supplementary Note 1.5.4).

a Schematic diagram of the designed coupler between the incident SWG and TWG waveguides. The optimized area has a compact footprint of 1.2 × 0.8 μm2 and is discretized into 12 × 8 pixels. Each pixel is occupied by either silicon or air according to the GA optimization. a1–a3 The distributions of the TS before optimization, after optimization (15 generations in GA), and the target distributions. b Changes of transmittance T and degree of TSM β with the number of iterations N in the GA optimizing process. The transmission increases from 52.8% to 96.3%, and β increases from 0.271 to 0.843 after 15 iterations of optimization. Inset: bandwidth of the coupler. c Electric field distributions of pre-optimization (N = 0) and after-optimization (N = 15) structures.

Figure 3(b) shows the changes of β and transmission efficiency T with the number of iterations N. Results show that β and T are tightly bundled and increase almost synchronously. At the same time, however, the two curves are not overlap exactly, and there is a slight discrepancy between T and β due to the complex multiple-scattering of light by the coupling interface. After optimization of 15 generations, T increases from 52.8% to 96.3%, which is the highest transmission ever reported. We also checked the bandwidth of the structure, and found T ≥ 90% in a wide bandwidth of 22 nm (from 1536 to 1558 nm), as shown in the inset of Fig. 3(b).

It is noted that T does not reach to 100% is not due to the limitation of the TSM principle, but is due to the moderate parameters we selected to meet the experimental precision (as shown below). For example, T can be continuously increasing to more than 99% by shrinking the pixel size to 50 nm (Section Supplementary Note 1.5.5).

To verify the TSM mechanism discussed above, we fabricate the sample on a silicon wafer. The non-optimized coupling is also fabricated for comparison. The experimental setup for measurement is shown in Fig. 4(a). The scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of the TWG and optimized coupler is shown in Fig. 4(b). The optimized areas on the left (input coupling) and right (output coupling) sides of the TWG are mirror symmetry. More details about the sample and fabrication are shown in Supplementary Note 2.

a Schematic of experimental setup of the measurement. Light signal from an optical fiber tip is coupled into the waveguide (TE mode) through the input grating, and then a 50/50 Y-splitter sends the signals to the optimized coupler (upper branch) and to a reference arm (lower branch). The transmitted power is coupled out from the grating and collected by another optical fiber pigtail for detection. b SEM images of the optimized sample, including the TWG and the input and output waveguides on both sides, as well as the corresponding left and right optimization areas. c Experimentally measured results, and the peak value of 94.2% around 1555 nm is obtained. d Numerically computed results, which agrees well with those of measured results.

The light from a fiber is coupled into the waveguide through the input-grating, which is a TE polarized fundamental mode. Then a 50/50 Y-splitter is used to split the light into the upper and lower channels, and transmitted through the optimized TWG (upper channel) and the reference arm (lower channel), respectively. Then, the transmitted light signals were coupled out from the output-grating and collected by a fiber pigtail for detection, and the results are shown in Fig. 4(c).

It is observed that the transmission of the optimized sample is greatly improved within the frequency range of 1530−1570 nm, and the highest transmission efficiency reaches 94.2% at λ = 1555 nm, which agree well with the numerical simulation results shown in Fig. 4(d). These experimental results confirmed the validness of TSM in the coupling of topological waveguides. The nearly perfect coupling of waveguide and topological waveguides implies the optical chips based on topological devices are possible. In addition, the TSM mechanism provides a solution for the efficient coupling of on-chip optical waveguides because transverse spin-momentum locking is a common phenomenon in the strongly confined electromagnetic fields of micro and nanophotonics.

In conclusion, we have presented the TSM mechanism for the efficient coupling of topological photonic structures. We theoretically analyzed the coupling mechanism, designed the coupler, and fabricated and measured the coupler experimentally. The theoretical transmission efficiency of 96.3% and measured value of 94.2% are obtained successfully, which are much higher than those reported before. It is noted that the transmission efficiency could be increased further with a deeper optimization, and the corresponding method can be extended to any other topological structures. The perfect coupling of strip waveguide and topological waveguide reported in this paper combined with the advantages of unidirectional propagation and efficient in-/out-coupling of topological waveguide, and will prompt the rapid development of transverse-spin-matched nanophotonics.

Methods

Simulation

All of the simulation results in this work are calculated with full three-dimensional (3D) simulations using the finite-difference time-domain method. We use the periodic structure to obtain the band structure (Supplementary Note 1.2) and the transverse spin distribution of topological waveguide. In all simulations, the maximum scale of the discrete grid is 10 nm, making the resolution large enough to ensure the convergence.

Sample fabrication

The experimental samples were fabricated on a standard SOI wafer with a 220-nm-thick top silicon layer and a 2-μm-thick buried oxide layer, using a standard CMOS technique. The fabrication was done in two steps. Step 1: the electron-beam lithography and inductively coupled plasma is applied to pattern the top silicon layer, including topological waveguides, grating waveguide and other waveguide structures. Step 2: the top silica layer under the topological PC waveguide is etched by wet method to make it suspended. Please refer Supplementary Note 2.1 for more details of the fabrication process.

Measurement

In the experiments, a continuous wave generated by the tunable laser (Santec TSL-570) was first launched into a fiber polarization controller (FPC) to select TE mode, and then the light in fiber is coupled to the sample with the aid of an input grating. After passing through samples, the transmitted light signal coupled to the right output grating is collected by the fiber and fed into the optical power meter (NOYES OPM4). Please refer Supplementary Note 2.2 for more details on the Schematic diagram of experimental setup and the transmittance measurements.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and the supplementary materials.

References

He, X.-T. et al. A silicon-on-insulator slab for topological valley transport. Nat. Commun. 10, 872 (2019).

Arora, S., Bauer, T., Barczyk, R., Verhagen, E. & Kuipers, L. Direct quantification of topological protection in symmetry-protected photonic edge states at telecom wavelengths. Light Sci. Appl. 10, 9 (2021).

Shalaev, M. I., Walasik, W., Tsukernik, A., Xu, Y. & Litchinitser, N. M. Robust topologically protected transport in photonic crystals at telecommunication wavelengths. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 31–34 (2019).

Yang, Y. et al. Terahertz topological photonics for on-chip communication. Nat. Photonics 14, 446–451 (2020).

Shi, B. et al. Multiparticle resonant optical sorting using a topological photonic structure. Photon. Res. 10, 297 (2022).

Jia, R. et al. Valley-conserved topological integrated antenna for 100-Gbps THz 6G wireless. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi8500 (2023).

Jalali Mehrabad, M. et al. Chiral topological photonics with an embedded quantum emitter. Optica 7, 1690–1696 (2020).

Ju, L. et al. Topological valley transport at bilayer graphene domain walls. Nature 520, 650–655 (2015).

Khanikaev, A. B. et al. Photonic topological insulators. Nat. Mater. 12, 233–239 (2013).

Lu, L., Joannopoulos, J. D. & Soljačić, M. Topological photonics. Nat. Photon. 8, 821–829 (2014).

Jia, R., Tan, Y. J., Navaratna, N., Kumar, A. & Singh, R. Photonic supercoupling in silicon topological waveguides. Adv. Mater. 37, 2415083 (2024).

Hafezi, M., Demler, E. A., Lukin, M. D. & Taylor, J. M. Robust optical delay lines with topological protection. Nat. Phys. 7, 907–912 (2011).

Cheng, X. et al. Robust reconfigurable electromagnetic pathways within a photonic topological insulator. Nat. Mater. 15, 542–548 (2016).

Cha, J., Kim, K. W. & Daraio, C. Experimental realization of on-chip topological nanoelectromechanical metamaterials. Nature 564, 229–233 (2018).

Wu, X. et al. Direct observation of valley-polarized topological edge states in designer surface plasmon crystals. Nat. Commun. 8, 1304 (2017).

Wu, T. et al. Topological photonic lattice for uniform beam splitting, robust routing, and sensitive far-field steering. Nano Lett. 23, 3866–3871 (2023).

Wang, H. et al. Ultracompact topological photonic switch based on valley-vortex-enhanced high-efficiency phase shift. Light Sci. Appl. 11, 292 (2022).

Zhang, F. et al. Experimental realization of topologically‐protected all‐optical logic gates based on silicon photonic crystal slabs. Laser Photon. Rev. 17, 2200329 (2023).

Kumar, A. et al. Active ultrahigh-Q (0.2 × 106) THz topological cavities on a chip. Adv. Mater. 34, 2202370 (2022).

Xie, X. et al. Topological cavity based on slow-light topological edge mode for broadband purcell enhancement. Phys. Rev. Appl. 16, 014036 (2021).

Zhang, W. et al. Low-threshold topological nanolasers based on the second-order corner state. Light Sci. Appl. 9, 109 (2020).

Shao, Z.-K. et al. A high-performance topological bulk laser based on band-inversion-induced reflection. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 67–72 (2020).

Zeng, Y. et al. Electrically pumped topological laser with valley edge modes. Nature 578, 246–250 (2020).

Ma, J. et al. Room-temperature continuous-wave topological Dirac-vortex microcavity lasers on silicon. Light Sci. Appl. 12, 255 (2023).

Yang, L., Li, G., Gao, X. & Lu, L. Topological-cavity surface-emitting laser. Nat. Photonics 16, 279–283 (2022).

Zaki, K. A., Seng-Woon, C. & Chunming, C. Modeling discontinuities in dielectric-loaded waveguides. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn. 36, 1804–1810 (1988).

Sanchis, P., Bienstman, P., Luyssaert, B., Baets, R. & Marti, J. Analysis of butt coupling in photonic Crystals. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 40, 541–550 (2004).

Ushida, J., Tokushima, M., Shirane, M., Gomyo, A. & Yamada, H. Immittance matching for multidimensional open-system photonic crystals. Phys. Rev. B 68, 155115 (2003).

He, A., Guo, X., Wang, T. & Su, Y. Ultracompact fiber-to-chip metamaterial edge coupler. ACS Photonics 8, 3226–3233 (2021).

Sanchis, P., Martí, J., Blasco, J., Martínez, A. & García, A. Mode matching technique for highly efficient coupling between dielectric waveguides and planar photonic crystal circuits. Opt. Express, OE 10, 1391–1397 (2002).

Qian, Z. et al. Chiral spontaneous emission propagation based on a honeycomb photonic crystal slab. Phys. Rev. A 109, 063504 (2024).

Coles, R. J. et al. Chirality of nanophotonic waveguide with embedded quantum emitter for unidirectional spin transfer. Nat. Commun. 7, 11183 (2016).

Ma, J., Xi, X. & Sun, X. Topological photonic integrated circuits based on valley kink states. Laser Photonics Rev. 13, 1900087 (2019).

Shi, P., Du, L., Li, C., Zayats, A. V. & Yuan, X. Transverse spin dynamics in structured electromagnetic guided waves. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2018816118 (2021).

Bliokh, K. Y., Bekshaev, A. Y. & Nori, F. Extraordinary momentum and spin in evanescent waves. Nat. Commun. 5, 3300 (2014).

Long, Y., Ren, J. & Chen, H. Intrinsic spin of elastic waves. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 9951–9955 (2018).

Lodahl, P. et al. Chiral quantum optics. Nature 541, 473–480 (2017).

Arora, S. et al. Breakdown of spin-to-helicity locking at the nanoscale in topological photonic crystal edge states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 203903 (2022).

Lang, B., McCutcheon, D. P. S., Harbord, E., Young, A. B. & Oulton, R. Perfect chirality with imperfect polarization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 073602 (2022).

Lax, M., Louisell, W. H. & McKnight, W. B. From Maxwell to paraxial wave optics. Phys. Rev. A 11, 1365–1370 (1975).

Bliokh, K. Y. & Nori, F. Transverse spin of a surface polariton. Phys. Rev. A 85, 061801 (2012).

Zhao, J. et al. Elastic valley spin controlled chiral coupling in topological valley phononic crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 275501 (2022).

Parappurath, N., Alpeggiani, F., Kuipers, L. & Verhagen, E. Direct observation of topological edge states in silicon photonic crystals: Spin, dispersion, and chiral routing. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaw4137 (2020).

Shen, B., Wang, P., Polson, R. & Menon, R. An integrated-nanophotonics polarization beamsplitter with 2.4 × 2.4 μm2 footprint. Nat. Photon. 9, 378–382 (2015).

Molesky, S. et al. Inverse design in nanophotonics. Nat. Photon. 12, 659–670 (2018).

Liu, Z. et al. Integrated nanophotonic wavelength router based on an intelligent algorithm. Optica 6, 1367 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Arbitrarily routed mode-division multiplexed photonic circuits for dense integration. Nat. Commun. 10, 3263 (2019).

Piggott, A. Y. et al. Inverse design and demonstration of a compact and broadband on-chip wavelength demultiplexer. Nat. Photon. 9, 374–377 (2015).

Forrest, S. Genetic algorithms: principles of natural selection applied to computation. Science 261, 872–878 (1993).

Yu, Z., Cui, H. & Sun, X. Genetically optimized on-chip wideband ultracompact reflectors and Fabry–Perot cavities. Photon. Res. 5, B15 (2017).

Lalau-Keraly, C. M., Bhargava, S., Miller, O. D. & Yablonovitch, E. Adjoint shape optimization applied to electromagnetic design. Opt. Express 21, 21693–21701 (2013).

Hughes, T. W., Minkov, M., Williamson, I. A. D. & Fan, S. Adjoint method and inverse design for nonlinear nanophotonic devices. ACS Photonics 5, 4781–4787 (2018).

Vercruysse, D., Sapra, N. V., Su, L., Trivedi, R. & Vučković, J. Analytical level set fabrication constraints for inverse design. Sci. Rep. 9, 8999 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the funding provided by the Heilongjiang Natural Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scholars (Grant No. JQ2022A001), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12274105). We thank the HPC Studio at the School of Physics, Harbin Institute of Technology for access to computing resources through INSPUR-HPC@PHY.HIT.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.S., H.L., and W.D. conceived the idea and developed the theory. B.S., R.F., Y.Z., and Y.C. designed and performed the analytical and numerical analysis of the structure. B.S., Q.J., S.G., J.Y., and X.L. performed the experiments. B.S., X.L., T.Z., and W.G. analyzed the data. B.S., Y.G., D.T., and W.D. wrote the manuscript. F.S., C.G., Y.C., C.Q., and W.D. supervised the project. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jianwei Wang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, B., Jia, Q., Li, X. et al. Efficient coupling of topological photonic crystal waveguides based on transverse spin matching mechanism. Nat Commun 16, 4645 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59941-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59941-6

This article is cited by

-

ZenBand: a numerical solver of photonic crystals with a graphical user interface

Scientific Reports (2026)