Abstract

Ferromagnetic semiconductors, coupling charge transport and magnetism via electrical means, show great promise for spin-based logic devices. Despite decades of efforts to achieve such co-functionality, maintaining ferromagnetic order at room temperature remains elusive. Here, we address this long-standing challenge by implanting dilute Co atoms into few-layer black phosphorus through atomically-thin boron nitride diffusion barrier. Our Co-doped black phosphorus-based devices exhibit ferromagnetism up to room temperature while preserving its high mobility (~\({1000{{{\rm{cm}}}}}^{2}{{{{\rm{V}}}}}^{-1}{{{{\rm{s}}}}}^{-1}\)) and semiconducting characteristics. By incorporating ferromagnetic Co-doped black phosphorus into magnetic tunnel junction devices, we demonstrate a large tunnelling magnetoresistance that extends up to room temperature. This study presents a new approach to engineering ferromagnetic ordering in otherwise nonmagnetic materials, thereby expanding the repertoire and applications of magnetic semiconductors envisioned thus far.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

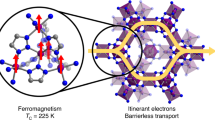

The quest for ferromagnetic-and-semiconducting systems that electrically function at room temperature poses significant challenges1. The recent 2D magnets such as CrI32,3,4 and CrSBr5 can combine electric-field tunable charge transport and spin configuration, which manifests as a magnetic transistor, yet the Curie temperature (\({T}_{{{{\rm{C}}}}}\)) is still below 160 K. Conventional dilute magnetic semiconductors (DMSs) based on substitutional magnetic doping of nonmagnetic semiconductors6,7,8 (e.g. II-VI CdTe6, III-V GaAs9,10, InAs11,12 or GaSb13,14, oxides like (TiO215, ZnO16,17), SiGe18 and 2D transition-metal dichalcogenides19,20,21,22) provide alternative solutions for high \({T}_{{{{\rm{C}}}}}\) up to room temperature. However, magnetic doping typically degrades the mobility of DMSs to a mere few \({{{{\rm{cm}}}}}^{2}{{{{\rm{V}}}}}^{-1}{{{{\rm{s}}}}}^{-1}\)23,24 or limits gate-tunability18,22. A room-temperature ferromagnet that simultaneously exhibits critical semiconducting characters such as high mobility, a high ON/OFF ratio, and a low subthreshold swing remains elusive.

Doping of semiconducting van der Waals (vdW) materials can be minimally invasive to the electronic structure and thus well suited to incorporate magnetism in layered semiconductors25. Here black phosphorous (BP) could be employed as a model 2D semiconductor to demonstrate such doping26 owing to its unique semiconducting features such as a moderate band gap27, record electron mobilities28,29,30, room-temperature micron-scale spin relaxation lengths31, high spin anisotropy32 and suitability for cobalt (Co) doping to yield ferromagnetic (FM) order33. Previous intercalation studies on BP with non-magnetic adatoms show that the electronic mobilities of intercalated BP can even increase compared to few-layer pristine BP26. These characteristics render BP an attractive platform for intercalation with magnetic adatoms, presenting an opportunity to realize gate-tunable room-temperature magnetism while preserving its intrinsic semiconductor properties.

In this paper, we study the magneto-transport properties of the resulting Co-doped BP devices, fabricated in both the lateral geometry and the vertical geometry. In the lateral configuration, we observed gate-tunable anomalous Hall effect and hysteretic in-plane magnetoresistance (MR); in the vertical junction, we observed bias-and-gate tunable tunnelling magnetoresistance (TMR) up to room temperature. Our results establish dilute Co-intercalated BP as a gate-tunable magnetic semiconductor operating up to room temperature, showcasing its potential for versatile applications in spintronics and magneto-electronics.

Results

Our density-functional theory (DFT) suggests that BP intercalated with a few percent of Co (See schematics in Fig. 1a) can be FM33,34,35 (Supplementary Notes 1-2). Here, the hybridization with native p-derived bands of BP is minor, so the intercalated Co atoms induce little charge transfer to BP, preserving its ambipolar gate-tunability. We define “majority” and “minority” spin states as the population imbalance between spin-up and spin-down states in Co-BP relative to Co electrode. Figure 1b presents the corresponding DOS schematic for Fig. 1c. In addition, in the conduction band, the population of spin-up is equal to that of spin-down (quenched magnetic moments). But near the conduction band edge, there exists a localized magnetic state. This state can be probed with tunnelling experiments. Inside the gap, there is no accessible state. On the other hand, in the valence band, there is an imbalance of spin-up and spin-down states. This gives rise to alternating behaviour of majority and minority carries as a function of \({E}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}\). We note that the electric-field tunability in BP also depends on Co doing concentration (See Supplementary Fig. S1).

a Atomic structure of the Co-intercalated BP illustrating magnetic doping in this system. Spin density isosurfaces of the Co atoms support an FM order in Co-BP. b Spin-polarized band structure of the same supercell after intercalation of a Co atom (3%) between the phosphorene layers; blue (red) represents the spin-up and spin-down bands. The grey curves represent the bands of pristine bulk BP. c Calculated density of states (DOS) of Co-BP near the Fermi level (\({E}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}\)(0)) according to the bandstructure of the charge neutral configuration shown in (b). Blue and red bands represent spin-up and spin-down, respectively. Dashed line is the \({E}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}\). Light colours represent the total DOS, while dark colours show only the d orbital projected DOS.

First, we confirm the feasibility of implanting Co atoms in BP using planar-view atomic-resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) (See Fig. 2a, b, Supplementary Fig. S2 and Methods). We achieve average Co doping concentration and Co separation of ~3% and ~2 nm, respectively, and do not detect signatures of Co clustering or other defects (confirmed with four separate samples). To confirm the semiconducting nature of our Co-BP (See the optical micrograph and measurement set-up in Fig. 2c), we measure current under constant bias voltage (\({V}_{{{{\rm{SD}}}}}=\,\)−1 V) and back-gate voltage \({V}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}\) varying from −75 V to +100 V. A clear OFF state is visible for \({V}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}\) range between 0 V and 36 V. Beyond this range, our device shows bipolar behaviour with hole mobility up to 1000 \({{{{\rm{cm}}}}}^{2}{{{{\rm{V}}}}}^{-1}{{{{\rm{s}}}}}^{-1}\) and an ON/OFF ratio exceeding 5000 (Top panel in Fig. 2d). This suggests that our Co-BP remains charge neutral (or slightly p-type) and thus can be tuned into either n-type or p-type by the back gate.

a Planar-view atomic-resolution HAADF image of a Co-doped multilayer BP flake. The image intensity is directly related to the atomic weight of the imaged species. The brightest spots in the planar view HAADF image (marked with red circles) are isolated Co atoms on the BP surface while the dimmer spots (yellow circles) show isolated Co atoms intercalated in deeper interlayer spaces. b Intensity histogram of the mapped atomic columns in (a), indicating the adsorbed and intercalated individual Co atoms with P atomic columns. c Optical micrograph and measurement schematics of the lateral Hall bar device (Device A) of Co-BP on 285-nm SiO2/Si substrate. The ultra-thin BN acts as an encapsulation/diffusion barrier that protects BP and allows dilute Co intercalation. Pairs of Ti/Au (2/85 nm) contacts labelled by #1 and #2 and by #1 and 3 are used for probing the Hall resistance (\({R}_{{xy}}\)) and the channel resistance (\({R}_{{xx}}\)), respectively under a constant current from source (S) to drain (D). Scale bar: 4 μm. d Top panel: Transconductance of the lateral Hall bar device at \({V}_{{{{\rm{SD}}}}}=\) −1 V. Bottom panel: The magnetization field (\({B}_{{{{\rm{C}}}}}\)) as a function of back-gate voltages. The error bars are extracted by fitting with a confidence interval of 99.7%. e Two representative anomalous Hall effect curves at 1.6 K in the hole regime (red dots, fitted by the black line) and electron regime (blue dots). f Optical micrograph and schematics of Device B for in-plane MR measurement. The MR is probed by the voltage between the contacts labelled by #1 and #2. The injection electrode is made of Co/Ti (1.5 nm/35 nm), where Co was deliberately deposited as a discontinuous dust layer of 1.5-nm nominal thickness. Scale bar: 3 μm. g Temperature dependence of MR at \({V}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}=\) − 50 V and Ibias = −40 μA. For comparison, the bottommost curve (black) refers to the metallic electrode (Co/Ti) itself at \(T=\) 2.5 K, confirming it has no magnetoresistance. The in-plane field (\({B}_{{||}}\)) is collinear with the current. The zoomed-in details of the MR at 300 K are shown in the top panel.

Next, we investigate the magnetic nature of our Co-BP by performing AHE measurements (Device A, See Methods). We sweep an out-of-plane magnetic field (\({B}_{\perp }\)) and show the representative \({R}_{{{{\rm{xy}}}}}-{B}_{\perp }\) curves in hole and electron regimes (Fig. 2e). In the hole regime, the field dependence can be described by a Langevin-type function \({R}_{{xy}}^{{{{\rm{AHE}}}}}={R}_{0}^{{{{\rm{AHE}}}}}\tanh \left(\frac{B}{{B}_{{{{\rm{C}}}}}}\right)\)36, where \({R}_{0}^{{{{\rm{AHE}}}}}\) is proportional to the saturation magnetization and \({B}_{{{{\rm{C}}}}}\) is the saturation field (See the fitting in Fig. 2e). This suggests magnetism in Co-BP (See the extracted \({B}_{{{{\rm{C}}}}}\) in bottom panel of Fig. 2d and details in Supplementary Fig. S3). In contrast, we do not observe any AHE with a positive back gate, possibly because the lateral transport cannot probe the expected magnetic order near the conduction band minimum due to low conductance. This regime will be examined in the vertical tunnelling Devices C and D below, which is less sensitive to the low conductivity at the conduction band edge.

To corroborate the FM order in Co-BP, we compare its in-plane MR with a Co-dust film alone of the same evaporated thickness (~1.5 nm). Both geometries are shown in Fig. 2f (Device B, See Methods) and are capped by a Ti layer, since Co dust alone is non-conducting. We sweep the in-plane field (\({B}_{{{{\rm{||}}}}}\)) along the direction of the applied current along the zig-zag direction (See Supplementary Fig. S4). The absence of MR in “Co dust + Ti” electrode (probed with contacts labelled by “3” and “4”) strongly suggests the lack of FM long-range order in Co dust itself (curve labelled “Co dust” in Fig. 2g). In contrast, the Co-doped BP region (probed with contacts labelled by “1” and “2”) displays very large and hysteretic MR, as reflected in the longitudinal field sweeps at various temperatures up to 300 K shown in Fig. 2f. This is characteristic of a FM channel undergoing magnetization reversal as a function of a collinear magnetic field sweep37. Both \({B}_{{{{\rm{C}}}}}\) and \(\Delta R\) are finite, indicating that Co-BP remains FM beyond room temperature.

To further characterize the magnetism in Co-BP, we perform magneto-optic Kerr effect (MOKE) measurements at room temperature. We note that the Co dusts are also evaporated on adjacent Au pads to compare the differences in MOKE signals. In Co-BP, the out-of-plane polar MOKE signal is large, negative, and saturates at 700 mT. As expected, the saturation field at room temperature is smaller than that measured by the AHE at 1.6 K. Since the sample is slightly tilted, there is a small in-plane magnetic field component, allowing us to also record simultaneously the in-plane MR (See Methods). We observe an in-plane MR signal with a switching field that matches that of the MOKE signal originating from the initial in-plane reversal of the magnetization (blue region in Fig. 3a). It is also comparable to that observed in the in-plane MR measurements shown in Fig. 2g. In contrast, MOKE measurements of Co dust on Au electrodes exhibit none of these features. Instead, only a small kink near zero field indicative of disconnected Co clusters is observed (Fig. 3b).

a Kerr signal and MR signal. Blue region indicates the in-plane switching and the orange region indicates the out-of-plane saturation during the field scan. b A comparison of Kerr signals on Co-BP and Co on Au pads. Inset: Optical micrograph showing the Co-BP region. c MFM characterization of the sample at 1.7 K and under \({V}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}=\) − 40 V. At, as \({B}_{\perp }\) increases, a darker region (the edge is denoted by the dashed line) begins to appear in the Co-BP region. This corresponds to a negative frequency shift (Δf) that represents an attractive force between the cantilever and sample surface, indicating Co-BP becomes magnetic. d MFM profiles of the line scans for frequency shift (Δf) from c. The curves are shifted vertically for better presentation.

We also performed magnetic force microscopy (MFM) measurements (Methods & Supplementary Information). Here, we evaporate Co dusts onto the entire substrate such that we can compare the MFM signals from Co-BP and Co-SiO2 (See the labelled region in the micrograph from in Fig. 3c). We record the frequency shift (Δf) as a function of position (Fig. 3c) at 1.7 K. A large Δf is due to the attractive force between the magnetic cantilever and a magnetic substrate. In our experiments, we only observed such a magnetic signature for Co-BP at negative gate voltages and absent on the SiO2 substrate. Here, we discuss representative data at \({V}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}=-\)40 V. At zero magnetic field, no magnetic signal is observed. As the magnetic field increases, Δf increases in the Co-BP defined by the darker region with a well-defined edge (top part of the scan). On the other hand, Δf on the SiO2 region remains unchanged. At magnetic fields above 1.5 T, similar to the AHE measurements in Fig. 2c, the magnetic contrast saturates. Additionally, we show representative line scans of Δf in Fig. 3d. The difference in Δf between the scans at 0 T and 1.5 T is clearly visible in the Co-BP region (~0.1 Hz) but marginal on SiO2.

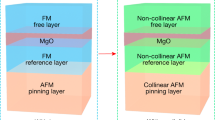

From an application perspective, an important question is whether Co-BP can be easily integrated into ready-to-use spintronic devices with gate tunability. Here, our proof-of-concept device is a magnetic tunnel junction (MTJ), which uses Co-doped BP layer and a 35-nm thick Co stripe act as the ferromagnetic layers with BN as the tunnelling barrier (Devices C and D in Fig. 4a) (See Methods and Supplementary Fig. S5). Intriguingly, we observe hysteretic switching between two distinct resistance states in the TMR when sweeping \({B}_{{{{\rm{||}}}}}\) along the easy axis of the Co contact. A representative TMR measurement at \(T=\) 2.5 K shown in Fig. 4b displays well defined, large resistance steps (∆R = 800 Ω, upper panel). In addition, the minor loop (lower panel) displays the square-shaped hysteretic profile expected for an FM–insulator–FM MTJs, thus confirming the existence of an effective FM contact on the BP side of the junction with a well-defined coercive field.

a Left panel: Schematic drawing of the vertical Co/BN/BP MTJ devices studied in this work, which are grounded by a bottom-contacted graphene electrode. Right Panel: Schematic spin-resolved density of states of bulk Co (left) and of Co-BP (right) qualitatively reflects the DFT + U band structures. For Co-BP, the light-shaded red and blue areas represent the phosphorus p-derived bands, only slightly changed relative to pristine BP; the darker, peaked traces represent the narrow bands associated with the Co d orbitals. The energy ranges labelled I–IV refer to the corresponding device operation states discussed in the text. b Major (upper panel) and minor (lower panel) loop scans of the tunnelling magnetoresistance (TMR) of TMJ (Device C) under \({V}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}=+ 20\) V at 2.5 K, with magnetic field parallel to the top Co electrode. c TMR of Device D at different gate voltages (\({V}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}\)), measured at 2.5 K with \({I}_{{{{\rm{bias}}}}}=\) − 60 μA (DC) + 5 µA (AC). From top to bottom: Co-BP becomes increasingly p-type with the positive-to-negative \({V}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}\) variation; background resistances are 1.5, 3.5, 7.6 and 2.7 kΩ, respectively (at \({B}_{{||}}=\) −60 mT). d TMR under Ibias= − 60 A (DC) + 5 µA (AC) in Device C at 300 K. Inset: The temperature dependence of TMR. The data are extracted from Supplementary Fig. S6.

We then demonstrate the gate-tunability of the Co-BP DMS (Fig. 4c). The measurements reveal a sequence of four “operational states”, namely, an absence of TMR in n-type BP (\({V}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}=\) + 60 V), a positive TMR near the edge of conduction band (\({V}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}=\) + 30 V), an absence of TMR inside the gap (\({V}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}=0{V}\)), a negative TMR p-type BP (\({V}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}=-50\,\)V). Specifically, we labelled these four states as I–IV with reference to the corresponding energy ranges highlighted in the DOS schematic of Co-BP shown in Fig. 4a. Here the position of \({E}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}\) in Co-BP determines whether the local moments \({{{{\boldsymbol{\mu }}}}}_{{{{\rm{Co}}}}}\) are finite or zero, allowing gate control of local moment formation. Specifically, in device state I, Co-BP is a n-type semiconductor with \({E}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}\) in the conduction band and quenched moments, explaining the featureless MR curve at \({V}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}\ge\) + 50 V. In device state II, \({E}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}\) lies near the band edge and \({{{{\boldsymbol{\mu }}}}}_{{{{\rm{Co}}}}}\) is finite, so that Co-BP is FM and the heterostructure operates as a tunnelling spin valve that probes the localized magnetic moments from Co. In comparison, this state is not visible in lateral transport (i.e., Device A) mostly likely due to the marginal conductance at the conduction band edge38. Device state III is obtained upon further reducing \({E}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}\) into the gap, in which case, the itinerant carrier density may now be insufficient to couple FM order among them. Further reducing \({V}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}\) brings \({E}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}\) to the valence band with a substantial increase in carrier density. In device state IV, unlike in the conduction band minimum, Co-BP is reinstated as a FM contact and the spin-valve signal re-emerges but is inverted. The opposite TMR sign in states II and IV is in good agreement with DFT which also sees an inversion of majority and minority spins in BP. The tunnelling out of the bulk Co electrode injects minority spin polarization into Co-BP; consequently, a positive (negative) TMR step will only arise when minority (majority) states are dominant on the Co-BP side. The electric field effect of BP not only allows for turning ON/OFF magnetism but also a switch between positive and negative TMR signals.

Importantly, we examine whether our Co-BP DMS in a TMR device can function up to room temperature. Remarkably, the TMR signal is finite and retains sharp steps even at 300 K39 (Fig. 4d, see also). As expected, the TMR value decreases with increasing temperature due to spin-flip scattering and activation of inelastic tunnelling channels40, especially at high bias41,42 (Inset in Fig. 4d). The observation of TMR at 300 K (Fig. 4d) provides a lower bound for \({T}_{{{{\rm{C}}}}}\). Interestingly, this is in line with the indirect exchange coupling estimate (Supplementary Note 1). The TMR value also depends on the current bias and is maximum for \(-\)60 µA (See Supplementary Figs. S6 and 7).

Finally, we investigate the doping profile of our Co-doped BP of the Co/BN/BP heterostructures using scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM). As anticipated from the penetration of deposited metals into vdW materials43 and also the BN dissolution-precipitation process44, we observe that the topmost BN layers in contact with the Co electrode is amorphized and mixed with Co. However, a crystalline BN monolayer remains adjacent to BP, critical for the MTJ performance discussed above. This is also supported by non-linear \(I-V\) curves of the tunnelling junction (Supplementary Fig. S8). As mentioned earlier EELS mapping shows that Co is also incorporated into BP under the BN layer. From the close-up views of multiple regions in Fig. 5a (See panels i-iii), we do not detect any Co clusters inside BP layers. Figure 5b shows that the STEM-extracted vdW gap expands by about 10% at the BN/BP interface and gradually recovers the bulk value outside the Co penetration depth.

a Low magnification bright-field image of the Co/BN/BP heterostructure’s cross-sectional interface (scale bar 50 nm). Labels i–iii refer to magnified atomic-resolution bright-field images of the denoted regions, showing that the BP vdW structure and stacking is intact over 100’s of nm. b Evolution of the vdW interlayer gap (red) and monolayer thickness (blue), extracted from STEM cross-sections (inset), as a function of distance to the BN/BP interface (in number of BP monolayers). Scale bar: 1.5 nm. The lower inset illustrates our definition of the two plotted distances. c Line cuts of the elemental abundance perpendicular to the Co/BN/BP interface, extracted from electron energy loss spectra (EELS). The four coloured panels are energy dispersive spectrum (EDS) maps for the elements Co, P, N and B.

To further characterize the Co penetration, we did electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) along Co/BN/BP cross-sections, and obtained the elemental profiles shown in Fig. 5c. The depth profile of Co shows a penetration depth ~ 5 nm, with an average doping of around 3%. This can be controlled by the initial BN thickness and post-annealing process under high vacuum condition (See Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Fig. S9). Although the presence of cluster-free Co-BP is thus consistent with our transport data, it may not be the only possible explanation. The Co diffusion process may inevitably create certain atomic defects in the BN layers and the topmost BP layer, which could also contribute to the TMR switching and requires future experimental and theoretical investigation.

The AHE in p-type BP, the large hysteretic in-plane MR seen in planar transport and spin-valve switching behaviour observed in the MTJs are well-established hallmarks of robust FM order in Co-BP. Its vdW nature and electronic two-dimensionality are decisive in allowing non-detrimental magnetic doping and potentially large FM coupling. The coupled FM and semiconducting functionalities with high charge mobility up to room temperature is distinct from the types of electrical tunability commonly encountered in magnetic systems45 (See the comparison with other magnetic semiconductors in Supplementary Table S2). Given its electronic versatility30, its long spin-diffusion length31, and recent advances in large-scale growth and integration of BP46, our work opens the prospect of employing Co-BP as an active semiconducting FM element in potential spintronics applications without suffering conductivity mismatch problem. This methodology could also be applied beyond BP (Supplementary Fig. S10), thereby expanding the library of low-dimensional magnetic materials. Developing encapsulation techniques to ensure the practical use of our Co-BP devices will be a subject for further investigation in future.

Methods

Device fabrication

Device A: We mechanically exfoliated black phosphorus (BP) crystals onto a silicon substrate (covered by a 285 nm SiO2) and identify an ideal flake (typically 10 × 5 µm2, thickness ~ 6~7 nm) as the channel. An ultra-thin BN flake (2~ 4 layers) is then transferred following the semi-dry transfer method47 to fully encapsulate the BP flake in inert conditions (N2 gas-filled glovebox with oxygen and moisture level below 1 ppm). This BN is used as a dispersive atom diffusion barrier, which reduces clustering while also preserving the structural integrity of BP during the subsequent processing (Supplementary Note 3). The BN/BP stack is annealed at 200 °C for 6 h under high vacuum (\({10}^{-6}\) Torr) to remove any bubbles formed during the transfer processes. This results in cleaner interfaces between 2D layers and hence improves the bonding of BP with BN layers. A standard electron beam lithography (EBL) technique is employed to pattern Ti/Au contacts (2 nm/85 nm). A second EBL is employed to pattern the Co-doping region and followed by the deposition of Co dust layers (~1.5 nm) under ultra-high vacuum conditions (\(5\times {10}^{-8}\) Torr), which ensures Co does not form a continuous layer. The deposition rate for the Co dust is 0.3 A/s. Throughout deposition, the high melting point of evaporated Co introduces defects in the BN layer, both kinetically and chemically, as observed in metal-semiconductor interfaces48. The device is finally annealed at 200 °C for 6 h under high vacuum (\({10}^{-6}\) Torr) for a more uniform doping and improvement of the contact conductance before measurements.

Device B: The sample used for the in-plane MR studies followed the same fabrication procedure as Device A except for depositing Co/Ti (1.5 nm/35 nm). The encapsulation of Co dust by light element Ti is used as a contact for current injection.

Devices C and D: We mechanically exfoliated graphene onto a silicon substrate (covered by a 285 nm SiO2) as the bottom contact. A BP slab (thickness ~ 6~10 nm) was firstly exfoliated onto a PDMS stamp49, then aligned with the bottom graphene and finally brought in contact using a microscope. By gently peeling off the PDMS stamp, the BP slab stays on the bottom contact. An ultra-thin BN flake (2~ 4 layers) is then transferred following the semi-dry transfer method47 to fully encapsulate the BP/graphene stack in inert conditions (N2 gas-filled glovebox with oxygen and moisture level below 1 ppm). This BN is used as a dispersive atom diffusion barrier, which reduces clustering while also preserving the structural integrity of BP during the subsequent processing (Supplementary Note 3). The final stack (BN/BP/Graphene) is annealed at 200 °C for 6 h under high vacuum (\({10}^{-6}\) Torr) to remove any bubbles formed during the transfer processes. This results in cleaner interfaces between 2D layers and hence improves the bonding of BP with BN layers. A standard electron beam lithography technique is employed to pattern electrodes and followed by the deposition of Co/Ti (35 nm/7.5 nm) layers under ultra-high vacuum conditions (\(5\times {10}^{-8}\) Torr). The deposition rate for the Co and Ti layers is 0.3 A/s and 1 A/s, respectively. The vertical tunnelling devices have a typical area of 1 × 1 μm2 in each tunnelling junction (Supplementary Fig. S5).

STEM characterization

The cross-sectional STEM specimens were prepared using a Cryo-focused Ion Beam (FIB) in ultra-high vacuum (<\({10}^{-6}\) mbar) in a liquid-nitrogen temperature environment. STEM imaging, EDS and EELS analysis of vertical heterojunctions of Co/BN/X (X = BP, graphite, MoS2, NbSe2) were performed on a FEI Titan Themis with a X-FEG electron gun and a DCOR aberration corrector operating at 300 kV. The inner and outer collection angles for the STEM images (\({\beta }_{1}\) and \({\beta }_{2}\)) were 48 and 200 mrad, respectively, with a convergence semi-angle of 25 mrad. The beam current was about 100 pA for imaging and spectrum collection. All STEM experiments were performed at room temperature. In the elemental analysis, the Co concentration (\({n}_{{{{\rm{Co}}}}}\) in Fig. 5b) is defined as the ratio of detected Co atoms to the total atoms of all the detected elements. This ratio and its error bars were calculated using a quantitative analysis model of EDS and EELS spectrum with commercial codes that are standard and routinely used in this type of elemental assessment.

Magnetotransport measurements

The magnetotransport measurements were performed in a home-made low-temperature electromagnetic system where the sample was sealed in vacuum and cooled down to a base temperature of 2.5 K. A standard low-frequency (13 Hz) lock-in technique was applied for signal acquisition with AC current amplitudes in the range 2~5 µA. Meanwhile, a DC source was driven through to the devices to probe their TMR or AMR. The differential resistance was measured by a second lock-in amplifier. The magnetoresistance was recorded as a function of an external magnetic field parallel to the easy axis of Co electrodes.

MOKE characterizations

MOKE measurements were performed with a red laser of 5-mW power, focused to a beam size of around 100-µm in length and 40-µm in height, covering the entire flake and portion of the nonmagnetic contacts. The incidence angle was approximately 16-degree, providing large polar MOKE signal (along out-of-plane field direction) and small longitudinal MOKE (parallel to beam direction). The sample is slightly tilted by about 2-degree with respect to the magnetic field, allowing a small in-plane reversal for the AMR signals at low magnetic fields.

MFM characterizations

MFM was conducted using an attocube attoDRY 2100 closed-cycle cryogenic system with attoAFM I probe, which operates at a base temperature of 1.7 K. The system is equipped with a superconducting magnet capable of applying out-of-plane field up to 9 T. Silicon probes with magnetic CoCr coating (MFMR by NanoWorld with a spring constant ranging from 2.5 to 5 N/m) were employed. Prior usage the probes were magnetized in out-of-plane direction using a neodymium magnet. For the measurements with gate voltage applied, MFM was performed with phase-locked loop and amplitude control to keep the same Q-factor. The magnetic contrast was observed in the frequency shift \(\Delta f\) of cantilever. Lift was kept in the range of 100–200 nm. For the room temperature tests the sample space was pumped and filled with He gas below 1 mbar to keep high Q-factor of the cantilever for better sensitivity.

First-principles calculations

First-principles calculations were performed on a \(5\times 4\times 2\) supercell of black phosphorus with a single cobalt atom between the two layers. The VASP software package was used to relax the structure and compute the electronic structure. A \(7\times 7\times 9\) Monkhorst-Pack reciprocal space grid and a plane wave energy cutoff of 500 eV were used. In order to account for the correlation effects intrinsic to transition metal compounds, we used the DFT + U method of Dudarev et al.50 with \({U}_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}=\) 1 eV. This value was chosen to reproduce the splitting of the two in-gap bands of the hybrid functional calculations of phosphorene reported in Seixas et al.33.

Data availability

The source data generated in this study have been deposited in the Figshare under accession code51.

References

Lee, Y. H. Is it possible to create magnetic semiconductors that function at room temperature? Science 382, eadl0823 (2023).

Huang, B. et al. Electrical control of 2D magnetism in bilayer CrI3. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 544 (2018).

Jiang, S., Li, L., Wang, Z., Mak, F. K. & Shan, J. Controlling magnetism in 2D CrI3 by electrostatic doping. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 549 (2018).

Klein, D. R. et al. Probing magnetism in 2D van der Waals crystalline insulators via electron tunneling. Science 360, 1218 (2018).

Telford, E. et al. Coupling between magnetic order and charge transport in a two-dimensional magnetic semiconductor. Nat. Mater. 21, 754 (2022).

Furdyna, J. K. Diluted magnetic semiconductors. J. Appl. Phys. 64, R29 (1988).

Ohno, H. Making nonmagnetic semiconductors ferromagnetic. Science 281, 951 (1998).

Dietl, T. A ten-year perspective on dilute magnetic semiconductors and oxides. Nat. Mater. 9, 965 (2010).

Ohno, H. et al. (Ga,Mn)As: a new diluted magnetic semiconductor based on GaAs. Appl. Phys. Lett. 69, 363 (1996).

Chiba, D. et al. Magnetization vector manipulation by electric fields. Nature 455, 515 (2008).

Ohno, H. et al. Electric-field control of ferromagnetism. Nature 408, 944 (2000).

Chiba, D., Yamanouchi, M., Matsukura, F. & Ohno, H. Electrical manipulation of magnetization reversal in a ferromagnetic semiconductor. Science 301, 943 (2003).

Tu, N. T., Hai, P. N., Anh, L. D. & Tanaka, M. Magnetic properties and intrinsic ferromagnetism in (Ga,Fe)Sb ferromagnetic semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 92, 144403 (2015).

Goel, S., Tu, N. T., Ohya, S. & Tanaka, M. In-plane to perpendicular magnetic anisotropy switching in heavily-Fe-doped ferromagnetic semiconductor (Ga,Fe)Sb with high Curie temperature. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 084417 (2019).

Matsumoto, Y. Room-temperature ferromagnetism in transparent transition metal-doped titanium dioxide. Science 291, 854 (2001).

Ueda, K., Tabata, H. & Kawai, T. Magnetic and electric properties of transition-metal-doped ZnO films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 79, 988 (2001).

Chen, R. et al. Tunable room-temperature ferromagnetism in Co-doped two-dimensional van der Waals ZnO. Nat. Commun. 12, 3952 (2021).

Wang, H. et al. High Curie temperature ferromagnetism and high hole mobility in tensile strained Mn-doped SiGe thin films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2002513 (2020).

Zhang, F. et al. Monolayer vanadium‐doped tungsten disulfide: a room‐temperature dilute magnetic semiconductor. Adv. Sci. 7, 2001174 (2020).

Fu, S. et al. Enabling room temperature ferromagnetism in monolayer MoS2 via in situ iron-doping. Nat. Commun. 11, 2034 (2020).

Yun, S. J. et al. Ferromagnetic order at room temperature in monolayer WSe2 semiconductor via vanadium dopant. Adv. Sci. 7, 1903076 (2020).

Song, B. et al. Evidence of itinerant holes for long-range magnetic order in the tungsten diselenide semiconductor with vanadium dopants. Phys. Rev. B 103, 094432 (2021).

Li, B. et al. A two-dimensional Fe-doped SnS2 magnetic semiconductor. Nat. Commun. 8, 1958 (2017).

Limmer, W. et al. Coupled plasmon-LO-phonon modes in Ga1-xMnxAs. Phys. Rev. B 66, 205209 (2002).

Rajapakse, M. et al. Intercalation as a versatile tool for fabrication, property tuning, and phase transitions in 2D materials. npj 2. D. Mater. Appl. 5, 30 (2021).

Wang, C. et al. Monolayer atomic crystal molecular superlattices. Nature 555, 231 (2018).

Li, L. et al. Direct observation of the layer-dependent electronic structure in phosphorene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 21 (2016).

Koenig, S. P. et al. Electric field effect in ultrathin black phosphorus. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 103106 (2014).

Li, L. et al. Black phosphorus field-effect transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 372 (2014).

Long, G. et al. Achieving ultrahigh carrier mobility in two-dimensional hole gas of black phosphorus. Nano Lett. 16, 7768 (2016).

Avsar, A. et al. Gate-tunable black phosphorus spin valve with nanosecond spin lifetimes. Nat. Phys. 13, 888 (2017).

Cording, L. et al. Highly anisotropic spin transport in ultrathin black phosphorus. Nat. Mater. 23, 479–485 (2024).

Seixas, L., Carvalho, A. & Castro Neto, A. H. Atomically thin dilute magnetism in Co-doped phosphorene. Phys. Rev. B 91, 155138 (2015).

Kulish, V. V., Malyi, O. I., Persson, C. & Wu, P. Adsorption of metal adatoms on single-layer phosphorene. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 992–1000 (2015).

Hu, T. & Hong, J. First-principles study of metal adatom adsorption on black phosphorene. J. Phys. Chem. C. 119, 8199–8207 (2015).

Gunkel, F. et al. Defect control of conventional and anomalous electron transport at complex oxide interfaces. Phys. Rev. X 6, 031035 (2016).

Leven, B. & Dumpich, G. Resistance behavior and magnetization reversal analysis of individual Co nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 71, 064411 (2005).

Kang, J. et al. Probing out-of-plane charge transport in black phosphorus with graphene-contacted vertical field-effect transistors. Nano Lett. 16, 2580 (2016).

Min, K. H. et al. Tunable spin injection and detection across a van der Waals interface. Nat. Mater. 21, 1144 (2022).

Meservey, R. & Tedrow, P. M. Spin-polarized electron tunneling. Phys. Rep. 238, 173 (1994).

Åkerman, J. J., Roshchin, I. V., Slaughter, J. M., Dave, R. W. & Schuller, I. K. Origin of temperature dependence in tunneling magnetoresistance. Europhys. Lett. 63, 104 (2003).

Evans, R. F. L., Atxitia, U. & Chantrell, R. W. Quantitative simulation of temperature-dependent magnetization dynamics and equilibrium properties of elemental ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 91, 144425 (2015).

Wu, R. J. et al. Visualizing the metal-MoS2 contacts in two-dimensional field-effect transistors with atomic resolution. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 111001 (2019).

Suzuki, S., Pallares, R. M. & Hibino, H. Growth of atomically thin hexagonal boron nitride films by diffusion through a metal film and precipitation. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 45, 385304 (2012).

Matsukura, F., Tokura, Y. & Ohno, H. Control of magnetism by electric fields. Nat. Nano. 10, 209 (2015).

Wu, Z. et al. Large-scale growth of few-layer two-dimensional black phosphorus. Nat. Mater. 20, 1203 (2021).

Dean, C. R. et al. Boron nitride substrates for high-quality graphene electronics. Nat. Mater. 5, 722 (2010).

Liu, Y. et al. Approaching the Schottky–Mott limit in van der Waals metal–semiconductor junctions. Nature 557, 696 (2018).

Castellanos-Gomez, A. et al. Deterministic transfer of two-dimensional materials by all-dry viscoelastic stamping. 2D Mater. 1, 011002 (2014).

Dudarev, S. L., Botton, G. A., Savrasov, S. Y., Humphreys, C. J. & Sutton, A. P. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: an LSDA+U study. Phys. Rev. B 57, 1505 (1998).

Fu, D. et al. Electric field-tunable ferromagnetism in a Van der Waals semi-conductor up to room temperature. Figshare. Dataset, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28813250 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank Pietro Gambardella and Thiti Taychatanapat for the fruitful discussions. B.Ö. acknowledges the support from the Singapore NRF Investigatorship (Grant No. NRF-NRFI2018-8), Competitive Research Programme (Grant No. NRF-CRP22-2019-8), and MOE-AcRF-Tier 2 (Grant No. MOE-T2EP50220-0017). D.F. acknowledges the support from National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62174143). J.Lin acknowledges the support from National Natural Science Foundation (Nos. 12304019, 52473302 and 12461160252), Guangdong Innovative and Entrepreneurial Research Team Program (Grant No. 2019ZT08C044), Guangdong Basic Science Foundation, China (2023B1515120039), Quantum Science Strategic Special Project (No. GDZX2301006), Shenzhen Municipal Funding Co-construction Program Project (No. SZZX2301004) from the Quantum Science Center of Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, China, and also the assistance of SUSTech Core Research Facilities, especially technical support from Cryo-EM Centre and Pico-Centre that receives support from Presidential fund and Development and Reform Commission of Shenzhen Municipality. J.F. and O.V.Y. acknowledge support by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant No. 204254). First-principles calculations have been performed at the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre (CSCS) under Project No. s1299 and the facilities of the Scientific IT and Application Support Center of EPFL. A.A. acknowledges support by the National Research Foundation, Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore (NRFF14-2022-0083). K.S.N. acknowledges support from the Ministry of Education, Singapore (Research Centre of Excellence award to the Institute for Functional Intelligent Materials, I-FIM, project No. EDUNC-33−18-279-V12), the National Research Foundation, Singapore under its AI Singapore Programme (AISG Award No: AISG3-RP-2022-028) and from the Royal Society (UK, Grant No. RSRP\R\190000). K.W. and T.T. acknowledge support from the JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Numbers 21H05233 and 23H02052), the CREST (JPMJCR24A5), JST and World Premier International Research Center Initiative (WPI), MEXT, Japan. A.S. acknowledges funding from the Singapore Ministry of Education Academic Research Fund (AcRF NUS Grant No. 23−1072-A0001), and A*STAR’s Individual Research Grant scheme (MTC IRG Grant No. M23M6c0112).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.Ö. initiated, coordinated, and supervised the work. D.F., T.Q., X.C., J. Liu and Y.J. performed the device fabrication and transport measurements. D.F., T.Q., X.C., J.F., V.P., A.A. and B.Ö. analysed the data. F.H. and J. Lin performed the DF-TEM, HR-TEM and STEM characterizations. G.K.K., N.L.Y. and A.S. performed MOKE characterizations. S.G., M.K. and K.S.N. performed MFM characterizations. J.F., O.V.Y. and V.M.P. provided theory work. K.W. and T.T. grew the BN crystals. T.Q., A.A. and B.Ö. co-wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, D., Liu, J., Hou, F. et al. Electric field-tunable ferromagnetism in a van der Waals semiconductor up to room temperature. Nat Commun 16, 10197 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59961-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59961-2