Abstract

Vat photopolymerization 3D printed flexible polymer foams, characterized by their porosity and lightweight nature, are in high demand for applications in thermal insulation, sound absorption, noise reduction, and biomedicine. The vat photopolymerization used UV-curable resin composed of oligomer can provide excellent fabrication accuracy, however the high cross-linking density after curing prevents the green part from expanding and further being processed into foam parts. In this work, a facile additive manufacturing polyurethane foam preparation method that successfully balances fabrication accuracy and expansion ratio is presented. The oligomer containing difunctional dynamic polyurea bonds in the resin system ensures the printing accuracy. Additionally, the dynamic urea bonds disassociate under a heating condition, reducing the cross-linking density and providing free space for expansion. Moreover, heat stimulated chain extension and crosslinking enhance the stretchability of the foams, demonstrating a strain of up to 650% at a density of 0.25 g/cm3. This work addresses the challenge associated with fabricating free foaming parts via vat photopolymerization by delivering favourable surface quality and high expansion ratio without compromising mechanical properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polymeric foams, particularly flexible polymer foam, have found extensive use across a wide range of industrial applications1. There is an increasing demand for customer-specific foam structure, especially in applications including aerospace, biomedical, semiconductor, and automotive industries2. Research on polymer foams through 3D printing has been conducted for years, primarily focusing on fused filament fabrication (FFF) technology3,4,5,6 and direct ink writing technology7,8. However, the foam fabricated using extrusion-based 3D printing technologies exhibit non-uniform distribution of interlayer cells. Additionally, due to the limitations imposed by the diameter of filament, it is challenging to print parts with high-precision geometric structures, which makes it unsatisfied for designated application scenarios9. Vat photopolymerization provides superior fabrication accuracy10, which makes it a promising candidate for preparation of high precision polymer foam. However, such high precision highly depends on the high cross-linking density restricting the chain reptation, while the foaming procedure depends on the flexibility of the polymer chain.

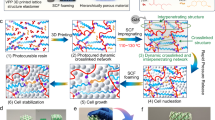

It has been reported that the employment of foaming strategies including the high internal phase emulsion template method11,12 and solvent etching techniques methods13,14, enables the preparation vat photopolymerization 3D-printed polymer foam parts. However, these approaches face challenges such as unsatisfied fabrication precision and uncontrollable expansion ratio. Regulating the composition of oligomers and monomers in UV-curable resins to decrease the crosslink density of the green parts after UV-curing can prepare foamable UV-curable resins with controllable expansion ratios. However, achieving an optimal crosslink density that balances high precision and a high expansion ratio remains a challenge and remains a research topic. It is revealed that in the cured UV-curable resin with high crosslink density, foaming agents primarily function to suppress crack formation and enhance toughness. However, this role limits their effectiveness in promoting the significant expansion of foaming agent15 (Fig. 1a). There have been reports on vat photopolymerization printed foams by UV-curable resins containing monomers only, but these approaches significantly compromise printing precision or mechanical performance of the foam (Fig. 1b)16,17. On the premise of maintaining the critical crosslink density of the polymer, reducing the crosslink density within the UV-cured parts through external stimuli and facilitating the free expansion of cells is an promising way to prepare high performance vat photopolymerization printed foam parts.

a Conventional resins for 3D printing: highly crosslinked structure makes the cured green parts unable to expand. b Monomer only composed UV-curable resin achieves a highly expansion ratio, however the dimensional accuracy of 3D printed green parts is poor due to the insufficient crosslinking density. c The UV-curable resin composed of PUB and monomers not only meets a higher printing accuracy for the green parts, but also achieves a higher and controllable foaming expansion ratio.

The dynamic covalent polymer networks (DCPN), while maintaining the integrity of the three-dimensional network of the cross-linked structure, can realize the polymer chain reconfiguration through bond exchange reactions18. This dynamic reconstruction mechanism allows the crosslinked polymer network to exhibit stress relaxation characteristics by the disassociation of dynamic covalent bonds. This feature of DCPN provides a strategy for precisely controlling the expansion ratio of cells during the foaming process. Furthermore, DCPN can significantly increase the entanglement extent of polymer molecular chains via exchange reactions, thereby substantially enhance the mechanical properties of the material19,20. Among the various dynamic acrylic polymer systems, polyurethane methacrylate blocking (PUB) oligomer containing thermally unstable covalent bonds21, has been successfully employed in preparing UV-curable resins with enhanced mechanical properties22 and self-healing capabilites23.

PUB containing tert-butylamine exhibit thermal instability24. After thermal post-treatment, released free isocyanate groups can react with polyamines to form a polyurethane crosslinked network, thereby enhancing the mechanical properties25. The introduction of difunctional oligomer PUB as main component together with thermally expandable microspheres (TEMs) as the foaming agents in the foamable UV-curable resin system exhibits the following advantages. First, the high modulus characteristic of the difunctional oligomer significantly improves the storage modulus of green parts during 3D printing process. This simultaneously improves printing accuracy and increase the printing success rate. Second, by synchronizing the foaming temperature and dissociation temperature of the oligomer, the expansion procedure can be realized in a single temperature range, resulting in stable and controllable foaming ratios. Third, the reconfiguration of polymer chain through bonds exchange initiated by thermal post-treatment enables the formation of high entangled and micro-crosslinked polymer chain structures of printed foam parts (Fig. 1c).

Results and discussion

In this work, PUB was synthesized using PEG2000, IPDI, and TBAEMA. The synthesis process was detailed in our previous report26. To investigate the foaming possibility of synthesized PUB, the dissociation behaviour was first examined under thermal conditions. DSC results of synthesized neat PUB (Supplementary Fig. S1) initiated an endothermic behaviour at 80 °C. Therefore, the expansion temperature of the foaming agent should be higher than 80 °C. Moreover, DMA results (Supplementary Fig. S2) reveal that the storage modulus of UV-cured PUB decreases rapidly at temperatures ranged from 75–80 °C and drops to zero completely at c.a. 120 °C. This indicates that the UV-cured crosslinked points were deconstructed caused by the thermal disassociate of dynamic urea bonds. Furthermore, various foaming methods were explored. Results indicate that chemical foaming, supercritical CO2 foaming, and physical foaming methods failed to achieve high expansion ratios. After expansion, samples shrank back to their original dimensions within a short period, mainly due to the inability to prevent gas escape prior to post-curing. In contrast, samples prepared using thermally expandable microspheres (TEMs) displayed excellent shape retention (Supplementary Fig. S3). This is primarily because TEMs possess rigid shells that effectively prevent gas escape during cooling27. This feature also provides a sufficient processing window for foam materials during the post-curing stage.

Subsequently, 10 phr of TEMs and corresponding molar ratio (7.2 phr) of trifunctional polyether amine (PEA T403) as chain extenders were incorporated into PUB oligomer, along with TPO as a photoinitiator, for the initial printing tests. Detailed preparation procedure are outlined in the “Methods” section. It is worth noting that the viscosity of the UV-curable resin reached 33 Pa·s (Supplementary Fig. S4), significantly exceeding the conventional upper limit of vat photopolymerization. To address this challenge, the previously developed linear scan-based vat photopolymerization (LSVP) system28 was employed to print tensile test specimens. After cleaning the specimens with isopropanol, samples were subjected to thermal foaming and post-curing in an oven. The effects of varying foaming agents loading on the tensile properties were investigated in detail first (Supplementary Fig. S5). The results indicated that as the foaming agent content increased, both the density and tensile strength of the samples decreased; however, all samples exhibited improved elongation at break. Notably, when the foaming agent content was set at 10 phr, the sample achieved a fourfold volumetric expansion upon heating. Tensile testing revealed an elongation at break of up to 650% (Fig. 2a). This indicates that the released isocyanate groups under thermal conditions, together with the further chain extension facilitated by polyamines in the UV-curable resin system, significantly enhanced the mechanical performance of the foamed components.

a Tensile test of neat PUB printed foam (Left: digital photograph of tensile test; Right: corresponding stress-strain curve). b Printing precision test (IBOMA-TEMs5): The side length of the digital model is 60 mm, while the printed product width measures 60.1 mm. c Foaming precision test: the theoretical post-foaming size is 78 mm (the expansion ratio is 1.3), while the measured size is 78.14 mm. The inset in Fig. c is the SEM image of the sample. d Foaming procedure observation at different time intervals. e Finite element method is employed to simulate the expansion and heating of various lattices under directional thermal field. f Demonstration of the printed outcomes of samples featuring intricate lattice structure before and after foaming in midsole. g The post-foamed samples exhibit favourable compactness to midsole and outsole of a sport shoe.

Although simple structured samples can be printed using LSVP system, high-precision printing of complex geometric structured parts are not available to be printed. Here, monomers were introduced to reduce viscosity in the UV-curable resin system, enabling high-precision fabrication. Accordingly, the effects of varying types of monomers to PUB on foam density and mechanical properties were investigated, as demonstrated in Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Fig. S6. Notably, our findings indicate that the expansion ratio is solely influenced by the content of TEMs and irreverent to the monomer. It was also revealed that the combination of PUB oligomer with isobornyl methacrylate (IBOMA), characterized by its rigid bridged-ring structure, facilitates the fabrication of rigid foam components. Conversely, when PUB oligomer is mixed with lauryl methacrylate (LMA), renowned for its elongated pendant alkane chain, it results in soft foam exhibiting favourable resilience. Generally, monomers with longer side chains after UV curing tend to lower the overall glass transition temperature, thereby exhibiting better flexibility at room temperature. On the other hand, monomers that introduce more rigid, cyclic functional groups upon curing increase the overall glass transition temperature, resulting a higher rigidity29,30,31. To explore the impact of diluents on the success rate of printed parts, photocuring kinetics tests on different samples were conducted (Supplementary Fig. S7). All samples exhibit a rapid curing behaviour by reaching the peak storage modulus in a short time. The results indicate that the prepared foamable UV-curable resin is suitable for commercialized vat photopolymerization devices.

To study the effects brought by the introduction of monomers on the foaming precision, foamable UV-curable resin for 3D printing containing PUB oligomer, 30 phr of IBOMA, 5 phr of TEMs and PEA T403 was prepared (named as IBOMA30-TEMs5, where 30 represents the phr in the UV-curable resin system, and the naming rule for subsequent samples follows the same pattern).Precision test models were printed, and the digital photo of printed sample before and after foaming are shown in Fig. 2b. The green parts side length of the printed part is 60.1 mm (60 mm for.stl file), indicating an error less than 0.2%. Upon foaming, due to the precision advantage of vat photopolymerization, the structure maintains a resolution accuracy of less than 200 microns, with clearly visible layer lines (Fig. 2c). Additionally, the dimensional stability of formulations containing IBOMA and LMA at various foaming agent contents were investigated (Supplementary Fig. S8). The results indicate that the selection of monomer show no significant impact on foaming precision. Concurrently, the corresponding scanning electron microscope (SEM) images and pore size distribution statistics (Supplementary Fig. S9, S10 and inset in Fig. 2c) reveal that the foam pores exhibit a closed-cell foam morphology, a morphology unattainable through etching13,14 and emulsion methods11,12.

Subsequently, IBOMA30-TEMs10 samples were further used to print various lattice models by commercial liquid crystal display (LCD)-based vat photopolymerization 3D printer. After printing, the printed green parts were put in the oven with a transparent observation window to foam. Different expansion status in certain time intervals were captured and illustrated in Fig. 2d. and Supplementary Movie S1. It was observed that the printed green parts begin to foam immediately once reaching the foaming temperature. Variations in heat transfer efficiency among different structures result in distinct expansion rates; however, they all uniformly expand to achieve the same expansion ratio, thereby demonstrating the adequacy of the available foaming time window. Observations of the foaming process revealed a strong correlation between the expansion behaviour and the direction of heat flux, attributed to the low thermal conductivity inherent in the polymer. Through finite element analysis simulating the heating field and expansion ratio, the foaming procedure including deformation degree can be accurately predicted (see Fig. 2e). To validate the applicability of this foaming method in other manufacturing industries, we printed a lightweight foam shoe sole and fitted it to the outsole (Fig. 2f). Typically, for the footwear industry, the size tolerance for manufactured foam is maintained within ± 1 mm. By assessing the expansion ratio of 3D-printed green components and proportionally scaling the digital 3D printing model file, it is evident that the foamed sample conforms precisely to the designed sample and seamlessly integrates with the corresponding rubber outsole (Fig. 2g). Generally, when foaming of elastomeric materials initiates from the solid state with a substantial expansion ratio, volumetric shrinkage is encountered as the foam undergoes cooling to room temperature subsequent to expansion32,33. Due to the plastic shell properties of the TEMs, the size of the 3D printed foam remains essentially unchanged upon cooling to room temperature. Our limit test results indicate that even after foaming, when subjected to a uniaxial magnification rate of 1.5 times (resulting in an overall volume magnification rate of 3.375 times), the size error of the printed solid block object did not exceed 5% (see Supplementary Fig. 11). The midsoles made of EVA foam and 3D printed foam (LMA30-TEMs10) underwent a compression durability test, revealing that the LMA30-10 foam exhibited consistently lower deformation after compression in comparison to the shoe-grade EVA foam. (Supplementary Fig. 12 and Supplementary Table S2)

Conventional foam preparation methods for elastomeric or rigid foams require distinctly different foaming and fabrication processes. In contrast, the mechanical properties of 3D printed foams can be facilely tuned by adjusting the composition of the UV-curable resin only. Here, three formulations were discussed in detail to investigate the impact of types and mass ratio of monomers on mechanical performance. First, tests on the compressive performance were performed, which is the most crucial mechanical property of the foam. For the IBOMA30 series samples, it can be observed that its compressive strength is slightly lower than that of commercial semi-rigid polyurethane foam when the density is low. However, when the density reaches 0.4 g/cm3 (The weight ratio of TEMs is 5 phr, the samples was named as IBOMA30-TEMs5), the compressive strength can reach 22 MPa, which significantly higher than the compressive strength of other polymer 3D-printed foams at the same density (Fig. 3a, b, corresponding detailed values are compiled in Supplementary Table S3)12,17,34,35,36,37,38,39,40. Noted that for conventional polyurethane foam, the density of the foam is determined by the pore diameter, while the wall thickness of the foam merely changed. Therefore, the compressive performance of the conventional foam shows an approximate linear relationship with its density41. Nevertheless, for 3D printed foam, its compressive performance shows a nonlinear relationship with its density. When the density is high (i.e., the expansion ratio is low), the printed foam exhibits excellent compressive strength. In order to explore the mechanism of the effect of expansion ratio on the mechanical properties of 3D printed foam, the thickness of the foam walls were observed through scanning electron microscopy (Supplementary Fig. S13). Corresponding images indicate that the TEMs induced foaming approach will significantly affect the wall thickness of the pores. When the expansion ratio is high, the polyurethane phase is isolated and distributed between the pore gaps. Whereas, as the density increases, the thickness of the pore walls significantly increases. At this stage, the polyurethane phase gradually transitions from isolated to a continuous homogeneous structure, replacing the TEMs shell as the main load-bearing structure. Furthermore, uniaxial tensile tests were also performed on IBOMA30 series samples of different densities (Fig. 3c). The tensile strength of the green part reached 13 MPa, and the elongation at break exceeded 300%. When the density decreased to 0.4 g/cm3, the tensile strength of the specimen was 2 MPa, and the elongation at break exceeds 160%. Even when the density drops to 0.17 g/cm3, it still maintains a tensile strength of about 1 MPa, surpassing the kPa level of most soft and semi-rigid polyurethane foams. This enhancement in mechanical properties is attributed to the PEA T403 chain extender effectively increasing the degree of entanglement in the 3D-printed polymer foam, thereby ensuring superior tensile properties. Simultaneously, the triamine introduces a certain level of crosslink points within the polymer network, which enhances both the toughness and resilience of the foam parts. Leveraging the advantages of 3D printing, the same material can achieve different compressive strain behaviours and thus achieve different buffering and shock absorption effects through the combination of different lattice structures. Here the LMA50-TEMs20 UV-curable resin, which exhibits favourable energy absorption effect, was employed to print three representative lattice structures for slow compression-unloading tests. The stress changes in the three lattice structures during the compression-release process are different, but they all show low damping characteristics (smaller curve area beneath the loading-unloading curves, Fig. 3d). As can be seen from the figure, under the same filling percentage, diamond structure exhibited the highest compressive strength throughout the process, indicating that this lattice structure is suitable for pressure-bearing applications. On the other hand, regular truss structure exhibits a lower initial strength. However, with the strain process increases, the strength rapidly rises, indicating that this lattice is more suitable for the application as filling and padding structures. It can be concluded that the 3D printed foams can flexibly change the damping characteristics of the foam through structural design to fulfil different needs. In the subsequent durability tests, due to the establishment of a linear polymer network structure with a higher molecular weight between PUB and the latent curing agent, the 3D printed foam with the SchwarzP lattice structure experienced a maximum strain loss of less than 8% after 1000 compressions (Fig. 3e, f).

a Compression strength of photo-cured foam and commercial polyurethane foam at different densities. b Compression strength of IBOMA30 series foam (marked with blue triangles) and other reported 3D printed foams, including DIW (circled by green colour), FDM (circled by red colour), and high internal phase emulsion methods (circled by green colour). c Tensile strength of IBOMA30 series foam with different TEMs loading. d Compression behaviour test for different lattice structures. e Mechanical behaviour of LMA30-TEMs10 foam under different compression cycle counts. f Residual strain (green dots) and stress loss (orange dots) of LMA30-TEMs10 foam during 1000 compression cycles. g Solubility behaviour of crosslinked foam (triamine cured) and entangled foam (diamine cured) in DMF solvent.

In addition to the significant impact of monomers on the mechanical properties of foam, the topological structure of polymer chain reconstructed by dissociated dynamic covalent bonds and polyamines during the heat post-treatment show notable effects on the mechanical performance of polymers42,43. The influence of polyamines with different functionalities and flexible molecular chain structures on foam properties during post-curing were further explored. Here, two representative amines were selected for a comparison: 4,4’-diaminodicyclohexyl methane (PACM), a diamine with a rigid segment structure, and PEA D400, a diamine with a long-chain polyether structure. Briefly, PACM and PEA D400 share same functionality but different flexible polymer chain, while PEA D400 and PEA T403 share same flexible polymer chain but different functionality. Tensile tests results (Supplementary Fig. S14) revealed that foam samples extended with PACM exhibited high Young’s modulus but a low strain (less than 50%). In contrast, 3D printed foam samples extended with PEA D400 exhibited superior strain under the same tensile strength, primarily due to the longer flexible chain segments of PEA, which enabled more effective molecular chain entanglement, resulting a higher strain. Foam materials extended with PEA T-403 benefited from both longer flexible chain segments and a higher number of crosslinking points, significantly improve the strength and strain simultaneously. These results indicate that regulating molecular chain entanglement and crosslinking density enables the regulation of mechanical properties. To further investigate the topological structure of polymer chains with various amines, swelling-gel experiments were conducted44,45. The crosslink density and gel fraction of PUB samples post-curing were calculated for resin formulations including with diamine extenders, with triamine extenders, and using a 1:1 ratio of diamine and triamine extenders (Supplementary Fig. S15). The sample without amine extender was treated as a reference sample. Compared to reference sample, diamines extended specimen significantly reduced crosslinking density due to the linear polymer chain structure, resulting in a molecular chain structure predominantly characterized by chain entanglement. Triamines extended sample exhibited the highest crosslinking density and the lowest gel fraction, with chain structures exhibiting high degrees of crosslinking. Meanwhile, PUB extended with a combination of diamine and triamine showed intermediate crosslinking density. Furthermore, DMF dissolution tests also demonstrated that, without post-treatment, the foam rapidly dissolved in DMF solvent, whereas the polymer network constructed with the PACM extended the dissolution time but eventually fully swelled. After cross-linking with the triamine (PEA T403), the prepared foam could not completely dissolve in DMF, with only partial swelling observed (Fig. 3g). The above results fully demonstrate that the regulation of the mass ratio of difunctionalized amine and tri-functionalized amine can effectively achieve the proportion of molecular chain entanglement and crosslink in foamed materials.

The research on high-performance lightweight components has always been of great interest, and the strategy of constructing multi-scale honeycomb structures is frequently employed to fabricate ultra-lightweight parts with high strength46. In order to further demonstrate the potential of polymer foam materials when integrated into complex lattices, this study utilizes LCD vat photopolymerization 3D printer to fabricate polymer foam components with diverse lattice structures and assesses their load-bearing performance in terms of weight reduction. At a filling percentage of 20%, the post-foaming structure using IBOMA30-TEMs15 exhibits an apparent density decrease to 0.05 g/cm3, enabling it to be easily supported by grass as depicted in Fig. 4a. Remarkably, its ultimate load-bearing capacity can increase up to 5 kg, nearly 1000 times its own weight (Fig. 4b). With an increased apparent density of 0.08 g/cm3, the printed foams can withstand a load equivalent to that of an adult weighing 75 kg without deformation, resulting in a load-bearing capacity reaching up to 2000 times its own weight (Fig. 4c). In addition to exhibiting a notable high strength-to-weight ratio, 3D-printed foam also demonstrates outstanding shock absorption and cushioning protection for irregularly shaped objects, such as artifacts. Here, the energy absorption capability of foamed and unfoamed samples with the same lattice and size was tested. The results revealed that the foamed lattice samples absorbed 41.7% of the total compression energy, whereas the unfoamed lattice samples only absorbed 7.7%. When comparing the energy absorption capacity per unit mass, the foamed sample exhibited a value of 42.075 J/g, while the unfoamed sample only achieved 3.948 J/g – a difference exceeding tenfold (Fig. 4d). Moreover, despite having equivalent volumes, the weight of the foamed sample was merely about one-sixth that of its unfoamed counterpart. These findings indicate that incorporating foam into lattices can significantly enhance their energy absorption capacity while reducing overall weight – thus highlighting promising prospects for utilizing 3D printed foams in cushioning and energy-absorbing materials. Here, a foam protective cover specifically designed to conform to the shape of the glass was fabricated, as shown in Fig. 4e. The cover, which has a thickness of 5 mm and incorporates an enclosed glass component, was subjected to a drop test from a height of ~2 meters. The unprotected glass shattered after a single impact, whereas the glass with foam protection remained intact (Supplementary Movie S2). This is primarily attributed to the fact that the 3D printed foam structure not only exhibits long-term cushioning properties due to its lattice structure but also, compared to a solid elastomeric material, the internal pores provide superior short-range cushioning effects. Consequently, it demonstrates enhanced impact resistance and energy absorption performance. Additionally, our corresponding finite element analysis (FEA) results (corresponding FEA conditions are depicted in the Methods section and the results are shown in Supplementary Movie S3) align closely with experimental test data (Supplementary Fig. S16), further validating that compared to FFF (fused filament fabrication) 3D printed foam47,48, our method offers isotropy advantages which bridge theoretical analyses with practical applications.

a 3D-printed foam weighing 8 g and with an apparent density of 0.05 g/cm³ can be supported by a blade of grass. b By optimizing the lattice structure, this foam can support an object weighing 625 folds than its own weight. c Utilizing a lattice-based foam pad, it is possible to support an adult man (75 kg) while only weighing 35 g. d Comparative analysis of energy absorption between foamed and unfoamed lattices of identical dimensions. e Owing to the lightweight nature and excellent energy absorption capability of the 3D printed foam material, upon landing, the unprotected glass shatters due to impact, whereas the protected glass remains undamaged. f Investigation into the thermal recovery ability following long-term large-strain compression.

Finally, considering the molecular characteristics of 3D printed foam, we assess the durability of the printed part (Fig. 4f). In general, once the collapse of foam pores, a certain degree of permanent deformation will occur, which is challenging to recover using conventional approaches49. However, due to the rigidness of TEMs’ shell, the 3D printed foam can preserve its structural integrity even under compression. Notably, after experiencing a significant deformation of 90% for a duration of 60 s, the foam can regain over 90% of its original dimensions through heat treatment within a temperature range of 60–70 °C. Observed recoverability surpasses that observed in most polymeric closed-cell foams (Supplementary Fig. S17).

In summary, we have developed a foamable UV-curable resin suitable for vat photopolymerization 3D printing. The foamable green parts prepared from this resin exhibit isotropic expansion, remarkably maintaining their original dimensional proportions originality. The performance of the printed foam can be effectively tuned from high strength to high resilience by altering the accompanying monomer. Furthermore, the density is adjustable within the range of 0.1–1 g/cm3, making it adaptable to a variety of application requirements. Notably, the 3D printed foam possesses the ability to recover and be reused after deformation through a simple heat treatment process. This as-prepared foamable UV-curable resin enables modern VPP techniques to access the preparation of one of the widely used polymeric materials.

Methods

Materials

Poly(tetramethylene ether glycol) (PTMG, Mn = 2000) (99%), isophorone diisocyanate (IPDI) (99%), 2-(tert-butylamino)ethyl methacrylate (TBEMA) (98%), dibutyltin dilaurate (DBTDL) (95%), trimethylolpropane tris[poly(propylene glycol), amine terminated] ether (PEA, trade name T403) (95%), Poly(propylene glycol) bis(2-aminopropyl ether) (PEA, trade name D400) (95%), isobornyl methacrylate (IBOMA) (50–150 ppm,MEHQ), lauryl methacrylate (LMA) (95%),2-hydroxyethyl acrylate (HEA) (96%), acryloyl morpholine (ACMO) (97%) were purchased from Aladdin Biochemical Technology(Shanghai,China) Co., Ltd., (2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)diphenylphosphine oxide (TPO) (95%) purchased from RYOJI Chemical(China) Co., Ltd. Thermally expandable microspheres (TEMs) (Expancel 930DU120) were purchased from Nouryon (China) Co., Ltd. UV absorber Orasol Orange 247 were purchased from BASF(China) Co., Ltd. All chemical reagents were used as received without further purification or processing.

Oligomer (PUB) synthesis

The UV-curable resin oligomer containing hindered amine structures was synthesized via a two-step process. In the initial step, 200 mmol of pre-dried PTMG (vacuum oven dried for at least 12 h) and 400 mmol of IPDI were introduced into a four-neck flask equipped with a stirring device, along with 0.01 g of DBTDL as a catalyst to facilitate the reaction between -OH and -NCO groups. The reaction was conducted under nitrogen protection at 50 °C for a duration of 3 h. The progress of the reaction was monitored using Fourier-transform infrared spectrometry, considering it complete when the absorption peak corresponding to the -NCO group at 2270 cm–1 remained stable. Subsequently, in the second step, TBEMA (400 mmol) was gradually added to the flask and reacted under nitrogen protection at 50 °C for an additional period of 3 h. The completion of this reaction was determined by observing the disappearance of the -NCO absorption peak.

UV-curable resin preparation

PUB, acrylate monomers, and TPO were initially introduced into a mixing container and blended under vacuum using a planetary mixer at 1800 rpm for 300 seconds. Following the mixing process, the appropriate amount of TEMs and PEA was added and further mixed at 1000 rpm for 240 seconds. This two-step mixing procedure effectively prevents premature deblock of PUB and its reaction with the amine chain extender due to temperature rise, while also avoiding potential Michael addition reactions between the amine and acrylate monomers. Three systems were prepared, each comprising five different formulations of TEMs content denoted as IBOMA30-x, LMA30-x, and LMA50-x respectively (where x represents the weight ratio of TEMs). Detailed formulations are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

3D printing process

The ELEGOO SATURN S, a compact 3D printer equipped with an LCD light source was utilized for the experiments. The measured light intensity of the printer ranged from 2.8 to 3.2 mW·cm−2. A layer thickness of 0.1 mm was set, consisting of 4 base layers and 3 transition layers. To determine printing time accurately, UV-curing kinetics tests were conducted alongside actual printing results: IBOMA30-TEMsx required a base layer exposure time of 15 s and a normal layer exposure time of 10 s; LMA30-TEMsx necessitated a base layer exposure time of 25 s and a normal layer exposure time of 16 s; LMA50-TEMsx demanded a base layer exposure time of 32 s and a normal layer exposure time of 22 s. Following printing, samples were subjected to ultrasonic cleaning using 95% ethanol for approximately three to five minutes (extended duration for complex models). Subsequently, the cleaned samples were exposed to UV light in a curing box for one minute to solidify any residual resin present on their surfaces.

Foaming process

The high-power oven equipped with a circulating air function was preheated to 160 °C. The models intended for foaming were carefully positioned inside the oven and subjected to a foaming time ranging from 5 to 15 minutes, depending on their size; solid models necessitated longer durations, while certain models required periodic flipping during the process to ensure uniform heating. Following the foaming stage, the models were subsequently transferred to a 120 °C oven and left for an additional duration of 5 h in order to accomplish secondary curing.

Rheological and photocuring kinetics tests

The resin viscosity at 25 °C was measured using a torque rheometer (DHR-2, TA Instruments, USA) with a shear rate range of 0.1–1000 s–1. A parallel steel plate fixture with a diameter of 40 mm and a loading gap of 250 µm was employed for the measurements. The photocuring kinetics of the resin were evaluated using the same instrument mentioned above. For this purpose, a lower fixture made of PMMA transparent light guide mirror with a diameter of 20 mm and an upper fixture made of aluminum parallel plate with the same diameter were used. Irradiation was performed for 100 seconds using a UV-LED light source with an intensity of 1.5 mW·cm−2 (wavelength: 320–500 nm). Changes in storage modulus (G’) and loss modulus (G”) were monitored during this process. During both experiments, specific parameters were set as follows: strain amplitude at 1%, angular frequency at 10 rad·s–1, and torque at 10 µN·m. Additionally, the loading gap for both tests was adjusted to be equal to or less than 200 µm.

Thermal analysis

The analysis of the deblocking temperature, secondary curing temperature, and foaming temperature of PUB was conducted using a differential scanning calorimeter (DSC) (DSC25, TA Instruments, USA) with a heating rate of 2 °C/min within a temperature range of 50–200 °C under nitrogen protection. The dynamic mechanical properties of polyurethane acrylate polyurethane prepolymers were determined using a dynamic thermomechanical analyzer (DMA Q800, TA instrument, USA). The DMA sample size was 10 mm × 8 mm × 0.65 mm. The storage modulus (E′) was measured in the temperature range of 20 °C to 180 °C at a constant frequency of 1 Hz and a heating rate of 3 °C min–1

Cell morphology observation

The microstructure of the foam was characterized by employing a scanning electron microscope (SEM) to acquire foaming structure. To enhance conductivity, the sample cross-sections were sputter-coated with gold for 60 seconds, while maintaining an electron gun acceleration voltage of 15 kV. Subsequently, ImageJ software was utilized for automatic statistical analysis and manual marking on SEM images to determine the foam cell size.

Foam density test

The density of samples with varying foaming ratios was determined using a densitometer through the water displacement method. To ensure complete immersion in water, each sample was carefully placed within a metal cage. The obtained results were then calculated utilizing Eq. (1).

where \({\rho }_{\alpha }\) is the density of the sample being measured, m1 is the mass of the sample in air, m2 is the mass of the sample immersed in water, and \({\rho }_{\omega }\) is the density of distilled water.

Mechanical performance test

The mechanical properties of the foam were evaluated using a universal testing machine (AGX-100 plus, Shimadzu, Japan). The compression performance test was conducted in accordance with ASTM-D3574-11 Test D, employing samples measuring 50 mm × 50 mm × 25 mm. Compression strength was determined by calculating the stress value after compressing to 75% strain, as per Eq. (2).

\({\sigma }_{{c}}\) is the compressive strength of the sample, F is the load borne by the sample, and A is the cross-sectional area of the sample in the compressive direction.

For cyclic compression testing, printed lattice structure foam models were compressed to a strain of 50% and subjected to repeated cycles of compression at a speed of 150 mm/min for a total of 1000 times. Strain loss was recorded as the difference between the maximum recovery value and the initial compression origin after each cycle, while stress loss referred to the discrepancy between the maximum stress value observed during each cycle and the initial compression stress value. The fatigue resistance of the samples was assessed based on changes in strain loss and stress loss. The compression rebound test employed rectangular samples measuring 50 mm × 50 mm × 25 mm, compressed to a strain of 90% and held for 60 seconds, followed by rapid unloading to measure the ratio of maximum recovery size to original size.

For quasi-static compression and energy absorption tests, three different lattice structure foam models were compressed at a speed of 0.16% s–1 (~3 mm/min) up to a strain of 70%, then immediately unloaded at the same speed back to the starting point. The energy absorption rate was calculated as the ratio of the area enclosed by the compression and unloading curves to that enclosed by the compression process and horizontal axis, according to Eq. (3).

where E is the energy absorption efficiency, \(\varepsilon\) is the sample compression strain, \({\varepsilon }_{\alpha }\) is the maximum compression strain, \({\sigma }_{c}\) is the stress curve of the loading process, and \({\sigma }_{r}\) is the stress curve of the unloading process.

In tensile testing, dog bone-shaped models were printed and stretched at a speed of 50 mm/min while recording maximum stress and maximum elongation prior to fracture occurrence.

Swelling test

The samples were immersed in DMF at 25 °C for 48 h, followed by drying in a ventilated environment at 60 °C for 24 h. The initial weight of the samples (m0), weight after dissolution (ms) and weight after drying (md) were recorded. Crosslink density was calculated using Flory-Rehner equation (Eq. 4)44.

Where, \(\nu\) is the volume fraction of polymer in the swollen mass, V is the molar volume of the solvent, n is the crosslink density, and \(\chi\) is the Flory solvent-polymer interaction term(Here are the interaction term of action of DMF and polyurethane\(\,\chi\) = 0.445).

Where, \({\rho }_{p}\) is the density of the polymer, \({\rho }_{s}\) is the density of the solvent, \({\rho }_{s}\) = 0.94 g/cm−3.

The gel fraction was calculated using the following equation.

Compression thermal recovery cycle test at 90% strain

Rectangular samples measuring 50 mm × 50 mm × 25 mm were subjected to compression at a rate of 50 mm/min until reaching a strain of 90%. Subsequently, the samples were maintained in this deformed state for a duration of 60 seconds, followed by placement in a temperature-controlled oven set at 70 °C for a period of 24 h. After cooling to room temperature, the ratio between the final sample size and its initial dimensions was measured. This experimental procedure was repeated ten times to evaluate the foam’s reusability.

Finite element analysis (FEA)

The temperature field of the foamed structure was analysed using Ansys Workbench 2022R1 software, incorporating both the transient thermal analysis module and static structural module. The bottom of the plate was fixed to ensure constraint, while a thermal boundary condition was applied to achieve a surface temperature of ~160 °C. Realistic boundary conditions were closely simulated through the implementation of non-separation and thermal flow boundaries.

Also, FEA was conducted to investigate the compression behaviour of various lattice structures, including the Cube, SchwarzP, Diamond, and Truss lattices configurations. The simulations were performed using the Static Structural module in Workbench by applying a uniform compressive load to each lattice structure. The objective was to assess and compare the mechanical responses of each configuration, with particular emphasis on their stress and strain characteristics under compression.

The material properties employed in the simulation encompassed a density (ρ) of 1.7 × 10−7 kg/m3, Young’s modulus (E) of 2 × 107 Pa, and Poisson’s ratio (ν) of 0.4. To accurately capture the nonlinear elastic behaviour of the foam, the Ogden third-order hyperplastic model was utilized for curve fitting. This model, accommodating substantial deformations typical in foams, underwent calibration using experimental data to precisely depict the stress-strain relationship of polyurethane foam under compressive loads, thereby facilitating a more realistic simulation of its mechanical behaviour.

The lattice structures were meshed based on their geometric complexity, striking a balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. The Cube structure was meshed using a hex-dominant element type with an element size of 1 mm, resulting in 470,596 nodes and 451,632 elements. In contrast, the SchwarzP, Diamond, and Truss lattice structures with more intricate geometries were meshed using tetrahedral elements. For the SchwarzP lattice structure, the element size was set to 0.3 mm, resulting in 358,158 nodes and 1,345,645 elements. The Diamond lattice structure had an element size of 0.4 mm and contained 1,211,783 nodes along with 5,518,984 elements. Similarly for the Truss lattice structure which also had an element size of 0.3 mm but updated node count of 869159 and included a total of 3,130,742 elements. This meticulous meshing strategy ensured accurate representation of each lattice’s geometry while maintaining simulation feasibility.

The mechanical responses of all simulations were compared under standardized boundary and loading conditions to ensure a fair comparison. Each lattice structure was subjected to a compressive displacement of 10 mm, replicating a uniaxial compression test. The resulting compressive stresses and strains were recorded for each configuration.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are available in the Source Data files. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Easley, A. D. et al. Safer polyurethane foams with cyclic carbonates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218062 (2023).

Jiang, H. et al. Mechanical properties of 3D printed architected polymer foams under large deformation. Mater. Des. 194, 108946 (2020).

Nofar, M. et al. Foam 3D printing of thermoplastics: a symbiosis of additive manufacturing and foaming technology. Adv. Sci. 9, 2105701 (2022).

Pawar, A. et al. J. Mastering the density of 3D printed thermoplastic elastomer foam structures with controlled temperature. Addit. Manuf. 58, 103066 (2022).

Andersson, H. et al. Variable low-density polylactic acid and microsphere composite material for additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 40, 101925 (2021).

Kalia, K. et al. In situ foam 3D printing of microcellular structures using material extrusion additive manufacturing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 22454–22465 (2022).

Visser, C. W. et al. Architected polymer foams via direct bubble writing. Adv. Mater. 31, 1904668 (2019).

Gao, J. et al. Foaming photothermal inks for direct-ink writing: hierarchical design and enhanced solar-powered interfacial evaporation. J. Mater. Chem. A 12, 6592–6609 (2024).

Gunasekaran, H. B. et al. Rapid carbon dioxide foaming of 3D printed thermoplastic polyurethane elastomers. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 4, 1497–1511 (2022).

Zhang, F. et al. The recent development of vat photopolymerization: a review. Addit. Manuf. 48, 102423 (2021).

Sušec, M. et al. Hierarchically porous materials from layer‐by‐layer photopolymerization of high internal phase emulsions. Macromol. rapid Commun. 34, 938–943 (2013).

Bliah, O. et al. 3D printing stretchable and compressible porous structures by polymerizable emulsions for soft robotics. Mater. Horiz. 10, 4976–4985 (2023).

Mu, X. et al. Porous polymeric materials by 3D printing of photocurable resin. Mater. Horiz. 4, 442–449 (2017).

Chen, Q. et al. 3D printed multifunctional, hyperelastic silicone rubber foam. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1900469 (2019).

Kang, X. et al. Strengthening and toughening 3D printing of photocured resins by thermal expansion microspheres. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 140, e53516 (2023).

Wirth, D. M. et al. Highly expandable foam for lithographic 3D printing. ACS Appl. Mater. interfaces 12, 19033–19043 (2020).

Seo, S. E. et al. Three-dimensional photochemical printing of thermally activated polymer foams. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 3, 4984–4991 (2021).

Zou, W. et al. Dynamic covalent polymer networks: from old chemistry to modern day innovations. Adv. Mater. 29, 1606100 (2017).

Zhu, G. et al. Introducing dynamic bonds in light‐based 3D printing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2300456 (2024).

Fang, Z. et al. 3D printable elastomers with exceptional strength and toughness. Nature 631, 783–788 (2024).

Bachmann, J. et al. Investigation of the temperature influence on the dual curing urethane-methacrylate resin Rigid Polyurethane 70 (RPU 70) in digital light synthesis (DLS). Addit. Manuf. 37, 101677 (2021).

Kim, S. et al. UV–thermally dual-curable 1K clearcoat via urethane and radical reactions. Prog. Org. Coat. 182, 107704 (2023).

Shi, J. et al. Thermal and UV light adaptive polyurethane elastomers for photolithography-transfer printing of flexible circuits. Mater. Horiz. 9, 3070–3077 (2022).

Fang, Z. et al. 3D printing of dynamic covalent polymer network with on-demand geometric and mechanical reprogrammability. Nat. Commun. 14, 1313 (2023).

Xie, S. et al. High performance poly (methyl methacrylate) via hindered urea bond crosslinking. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 9457–9467 (2022).

Huang, X. et al. 3D printing of high viscosity UV‐curable resin for highly stretchable and resilient elastomer. Adv. Mater. 35, 2304430 (2023).

Pawar, A. et al. Mastering the density of 3D printed thermoplastic elastomer foam structures with controlled temperature. Addit. Manuf. 58, 103066 (2022).

Weng, Z. et al. 3D printing of ultra-high viscosity resin by a linear scan-based vat photopolymerization system. Nat. Commun. 14, 4303 (2023).

Jagtap, A. R. & More, A. Developments in reactive diluents: a review. Polym. Bull. 79, 5667–5708 (2022).

Wang, D. et al. Low viscosity and highly flexible stereolithographic 3D printing resins for flexible sensors. Mater. Des. 243, 113052 (2024).

Porcarello, M. et al. Design of acrylated epoxidized soybean oil biobased photo-curable formulations for 3D printing. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 40, e00927 (2024).

Yang, C. et al. High-elastic and strong hexamethylene diisocyanate (HDI)-based thermoplastic polyurethane foams derived by microcellular foaming with co-blowing agents. J. CO2 Utilization 74, 102543 (2023).

Belmonte, P. et al. Foaming of thermoplastic polyurethane using supercritical CO2 AND N2: antishrinking strategy. J. Supercrit. Fluids 211, 106311 (2024).

Zhai, W., Jiang, J. & Park, C. B. A review on physical foaming of thermoplastic and vulcanized elastomers. Polym. Rev. 62, 95–141 (2022).

Zhang, S. et al. 3D-printed thermoplastic polyurethane/polyvinylidene fluoride gradient stiffness and hierarchical cellular structures with tailored energy absorption behaviour. Addit. Manuf. 83, 104062 (2024).

Zhao, J. et al. Corrugated thermoplastic polyurethane foams with high mechanical strength fabricated by integrating fused filament fabrication and microcellular foaming using supercritical CO2. J. CO2 Utilization 66, 102293 (2022).

Chen, X. & Lee, S. Morphology and compressive property of 3D-printed 3-pointed star shape prepared using lightweight thermoplastic polyurethane. Fibers Polym. 23, 1779–1788 (2022).

Dantzler, J. Z. et al. Porous polymer structures with tunable mechanical properties using a water emulsion ink. Materials 17, 1074 (2024).

He, X. et al. Aqueous condition-tolerated high internal phase oil-in-water Pickering emulsion as building block for engineering 3D functional materials. Chem. Eng. J. 446, 137162 (2022).

Loeb, C. K. et al. Hierarchical 3D printed porous silicones with porosity derived from printed architecture and silicone-shell microballoons. Addit. Manuf. 55, 102837 (2022).

Ferkl, P., Kršková, I. & Kosek, J. Evolution of mass distribution in walls of rigid polyurethane foams. Chem. Eng. Sci. 176, 50–58 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Highly entangled elastomer with ultra-fast self-healing capability and high mechanical strength. Chem. Eng. J. 479, 147689 (2024).

Guo, Z. et al. Engineering of chain rigidity and hydrogen bond cross‐linking toward ultra‐strong, healable, recyclable, and water‐resistant elastomers. Adv. Mater. 35, 2300286 (2023).

Flory, P. J. & Rehner, J. Jr Statistical mechanics of cross‐linked polymer networks II. Swelling. J. Chem. Phys. 11, 521–526 (1943).

Yoshida, H. et al. Kraft lignin in polyurethanes I. Mechanical properties of polyurethanes from a kraft lignin–polyether triol–polymeric MDI system. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 34, 1187–1198 (1987).

Yeo, S. J., Oh, M. J. & Yoo, P. J. Structurally controlled cellular architectures for high‐performance ultra‐lightweight materials. Adv. Mater. 31, 1803670 (2019).

Hu, B., Li, M., Jiang, J. & Zhai, W. Development of microcellular thermoplastic polyurethane honeycombs with tailored elasticity and energy absorption via CO2 foaming. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 197, 106324 (2021).

Marascio, M. G. et al. 3D printing of polymers with hierarchical continuous porosity. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2, 1700145 (2017).

Pradel, P. et al. In situ radiographic and ex situ tomographic investigation of pore collapse in laser shock-loaded polyurethane foam. J. Appl. Phys. 131, 055106 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Major Science and Technology Project of Fujian Province (Grant No.: 2021HZ027003)(Program Manager: L. W.), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Quanzhou City of Fujian Province (Grant No.: 2023GZ1) (Program Manager: Z. W.), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Fujian Province (Grant No.: 2023H4016, 2024N0063)(Program Manager: L. Z.), the STS Project of Fujian-CAS (Grant No.: 2022T3039, 2023T3043, 2024T3004)(Program Manager: Z. W.) and the Science and Technology Planning Project of Putian City of Fujian Province (Grant No.: 2023GJGZ004)(Program Manager: L. Z.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.W. and Z.W. contributed the conceptualization of the foamable UV-curable resin, methodology and original draft preparation. H.G. contributed to the methodology and investigations of the formulation. X.H. contributed the preparation of dynamic urea bonds oligomer. A.R.A. and X.D. contributed the corresponding finite element analysis and data collection. L.Z. contribute the data collection and analyse. X.Z. contributed the data curation and visualization. Y.L. and F.Y. contributed the lattice structure design for the midsole. L.W. contributed to the project administration, funding acquisition, manuscript review and editing. All authors contributed to data interpretation, analysis and drafting of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Z.W., H.G., and L.W. have patent pending to Fujian Institute of Research on the Structure of Matter, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Guillaneuf Guillaneuf, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.”

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Inclusion & ethics This research aligns with the inclusion & ethical guidelines embraced by Nature Communications.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, H., Huang, X., Arockiyasamy, A.R. et al. Vat photopolymerization of stretchable foam with highly entangled and crosslinked structures. Nat Commun 16, 4756 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60087-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60087-8