Abstract

Optical physical unclonable functions (PUFs) are state-of-the-art in advanced security applications. Fabricated with inherent randomness, they generate fingerprint-like responses, serving as trust anchors for material assets. However, the existing PUFs, typically reliant on microscopic spatial features, face increasing threats from rapidly advancing microscale manipulation techniques. Here, we present novel PUFs based on random nanoscale variations within multi-resonant gold-silicon particles. These inevitable structural differences, coupled with strong optical resonances, provide unique spectral features in particles’ photoluminescence (PL), which we encode as unclonable keys. Our approach surpasses the shortcomings of diffraction-limited designs, additionally offering a multi-functional platform for robust authentication of goods and verification of individuals. We demonstrate two security label models based on PL mapping and direct PL imaging, as well as a concept for the first all-optical one-time password verification token with an exceptionally high storage density of unique information. This work paves the way toward nanoscale-enabled unclonability, bringing enhanced security for hardware-based cryptography, personalized access control, and cutting-edge anti-counterfeiting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Secure authentication of goods and verification of individuals, essential components of modern life, face increasing risks from the dual nature of technological progress. The rapid innovation transfer from science to industry provides forgers with advanced tools to replicate anti-counterfeit measures1, while emerging quantum computing threatens the existing encryption protocols2,3. To address these challenges, the development of hardware-based cryptography solutions, in particular physical unclonable functions (PUFs), is crucial4,5.

Fabricated with stochastic processes, PUFs use inherent randomness in their physical composition to form unique challenge-response pairs (CRPs)6. Each PUF stores its own collection of CRPs, which are fundamentally impossible to duplicate without alternative, more precise production techniques. They are usually classified as either weak or strong7,8. Weak PUFs store only several CRPs, which limits their use to counterfeit protection1. Conversely, strong PUFs contain an immense number of CRPs, making their complete measurement in a reasonable timeframe unattainable9. These superior cryptographic primitives are well-suited for various applications: random key generation10, one-time password (OTP) encryption11,12, and others13.

Commonly, PUFs based on optical responses offer enhanced security and information capacity5,14,15. However, current fabrication techniques for strong optical PUFs10,13,16,17,18 are often incompatible with the existing manufacturing lines and/or susceptible to sophisticated machine learning attacks6,19. Moreover, most PUF designs rely on microscopic spatial features15,20,21,22,23,24,25, which threatens their long-term security, considering the recent progress in microscale manipulation techniques26,27,28,29,30. Reducing PUFs’ critical dimensions (which determine their unique CRPs) down to the nanolevel would be a logical evolutionary step5,26. However, this entails fundamental readout-related challenges, requiring spatial imaging with sub-diffraction resolution and tolerance to higher noise intensities.

Here, we present novel optical PUFs based on multi-resonant gold-silicon (Au/Si) submicroparticles. Due to the specifics of their laser fabrication, these particles exhibit distinct, intricate internal configurations, which inevitably affect their broadband photoluminescence (PL) spectra. We explore this structure-spectrum relationship and describe how truly random nanoscale variations in our particles’ internal arrangement, coupled with strong optical resonances, give rise to the unique spectral features in their PL. We employ these optical responses as unclonable keys, which turns out to be extremely advantageous thanks to the huge amount of unique information contained in each PL spectrum. In contrast to typical PUFs that rely on directly encoded spatial randomness within the microscale dimensions, our spectrum-based concept allows downscaling critical PUF sizes beyond the optical diffraction limit. We develop several techniques for harnessing our spectral randomness, ranging from the most basic methods to more advanced and beneficial ones, and offer adaptable PUF-based security applications, including robust anti-counterfeiting labels (weak PUFs) and ML-driven OTP verification tokens (strong PUFs, see Fig. 1).

First, the laser-induced fabrication of Au/Si structures yields submicroparticles with distinct intricate internal configurations. The random nanoscale structural variations of these particles greatly contribute to their multi-resonant nature, producing bright, broadband PL spectra with unique characteristics. Leveraging this spectral randomness, we propose two anti-counterfeiting label models for quick and reliable authentication. The first model utilizes PL mapping and spectrum decomposition, and the second one employs direct PL imaging of printed pixel patterns under unfocused laser beam excitation. Both approaches use weak PUFs, where each label’s signature serves as a key stored in a static database (DB). Also, we note that the time required to measure all possible PL spectra from one laser-printed microstructure sufficiently surpasses its fabrication time, enabling the realization of a strong PUF. Building upon this concept, we introduce a one-time password verification token. Our protocol utilizes individual PL spectra, measured from randomly selected points within the printed array of microstructures, as unique access keys. To ensure high-level security, each key is valid for a single verification attempt. A high-accuracy machine learning model facilitates robust comparison of PL spectra. For a deeper understanding of the concepts illustrated in this figure, please refer to the main text of the manuscript.

Results

Au/Si particles: laser fabrication and bright luminescence

Hybrid metal-dielectric systems are recognized as versatile nanophotonic platforms, whose diverse combinations unlock extraordinary optical features31,32,33,34,35. To develop robust spectral PUFs, we chose the well-proven tandem of gold and silicon. This choice stems from their considerable environmental stability, leading to a potentially limitless lifetime under standard ambient conditions. Furthermore, hybrid Au/Si structures (for example, nanoparticles) overcome the limitations of silicon in light emission by leveraging the superior light absorption of gold and its efficient hot carrier injection into the active material36,37.

To fabricate Au/Si particles, we adopted the femtosecond (fs) laser-induced dewetting technique38,39,40. In contrast to traditional ablation strategies41,42,43,44, our approach is more straightforward, providing ordered arrays of particle-based microstructures with high throughput. To achieve this, a tightly focused laser beam irradiates the surface of a thin bilayer gold-silicon film, cutting out micrometer-sized circles and simultaneously heating them (Fig. 2a, “Methods” section). As a result, patches of diatomic melt are formed that experience a sequence of non-equilibrium hydrodynamic perturbations45. Ultimately, the melt breaks up into randomly dispersed submicron droplets, governed by surface tension forces and Rayleigh-Plateau-like instabilities46. The resulting particles represent an intricate intermixing of gold and silicon components, which is established during their solidification (Supplementary Fig. 1).

a Schematic illustration of the experimental setup used to fabricate hybrid Au/Si particles, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of an array of created structures (scale bar: 5 μm). The radius of the circles outlined by a femtosecond laser is 1.5 μm. With a laser beam scanning speed of 50 μm/s, this fabrication method allows the creation of up to 200 structures per minute. The size distribution of particles in these structures is presented in Supplementary Fig. 2. b The PL spectrum measured from one of the obtained Au/Si particles (red) vs. the spectrum from the initial bilayer film (gray). For PL excitation, we used a fs-laser system with a central wavelength of 1050 nm (“Methods” section). A sharp peak at 525 nm corresponds to the second harmonic generation (SHG). c Wavelength-dependent PL slopes (i.e., powers of nonlinear dependence of PL intensity on pump intensity at a given wavelength) from four randomly selected particles. Taking into account that 3PA in Au is more efficient than that in Si37, while 2PA is the most probable nonlinear process in Si66, one can assume that the overall white-light signal results from these two separate absorption processes, responsible for their parts of the spectrum. d Bright-Field (BF), Dark-Field (DF), and PL images of a printed pixel illustration of the Yin-Yang symbol. Scale bar: 20 μm.

The obtained Au/Si structures exhibit an intensive ultra-broadband up-conversion PL signal, spanning from 450 to 900 nm (Fig. 2b, “Methods” section). By analyzing luminescence slopes, we identified two- and three-photon absorption (2PA & 3PA) processes as main contributors to the measured signal (Supplementary Fig. 3). Notably, the dependence of the slope on the emitted photon wavelength shows an interesting behavior: while PL in the near-infrared range is dominated mostly by 2PA, the blue component of the signal corresponds to 3PA (Fig. 2c).

One of the key parameters of spectral PUFs is the signal acquisition time, which should be carefully optimized to avoid excessive readout duration47. This property directly depends on the fabricated structures’ quantum efficiency (QE), which we estimated according to the method presented elsewhere48,49,50 (see Supplementary Notes 1–3 and Supplementary Figs. 4–7). As an example, we demonstrate studies for three particles whose cross-sectional views and corresponding QEs are shown in Fig. 3a. We also measured the QE map from a particle-based microstructure (Fig. 3d). The obtained efficiencies (on the order of ~1−3.5%) are relatively high for silicon-based PL sources (Supplementary Table 1). Accordingly, the typical signal acquisition time required to obtain low-noise PL spectra is quite short and ranges from 0.1 to several seconds, depending on the pump laser power (Supplementary Fig. 8).

a HDAAF-STEM and BF-STEM imaging of cross-sections of three investigated hybrid Au/Si particles and enlarged parts of BF-STEM maps. Scale bars: 150 nm. Inscriptions indicate the measured mean Si grain size and QE values for each particle. Characteristic Fast Fourier Transforms of high-resolution TEM images of silicon grains reveal their poly-crystalline structure (Supplementary Fig. 10). b Gold-Silicon phase diagram. The arrows indicate the expected evolution of melt Au/Si droplets during their solidification (Supplementary Note 4). 1 – liquid cooling stage, 2 – undercooling, 3 – recalescence, 4 – quasi-equilibrium segregated solidification. After complete solidification, solid-state cooling returns the resulting particle to thermal equilibrium with the environment. c Grain size distribution of the particle #1 fitted according to the Kolmogorov–Avrami–Mehl–Johnson (KAMJ) model described in ref. 60. Inscriptions indicate the estimated times of grain nucleation (tcI) and growth (tcv) during the solidification of this particle (Supplementary Note 5). d SEM image of a laser-fabricated structure consisting of randomly dispersed hybrid particles and the corresponding measured QE map. e Cross section of a computer-generated model of our gold-silicon particle and a calculated normalized distribution of the electric field amplitude inside it when illuminated by a linearly polarized plane wave at a wavelength of 1050 nm. f Numerical simulation results: dependence of the spectral width of the field enhancement factor (EF) range of the Au/Si particle on the S-to-V value of its gold network. Straight lines indicate the general trend of dependence.

To demonstrate the practical efficiency of Au/Si microstructures and the scalability of our fabrication technique, we printed several pixel patterns (Fig. 2d). We performed their direct luminescence imaging under unfocused laser beam excitation with a standard digital camera (“Methods” section). The obtained bright photos once again confirm feasible, reliable, and quick measurement of PL from our microstructures, essential for potential applications. These intriguing results stem from the unique features of the Au/Si particles’ internal organization, which we consider further.

Inner structure and multi-resonant nature of Au/Si particles

Next, we investigated the internal composition of the fabricated gold-silicon particles to determine how it affects their PL properties. For this, the cross-sections of three different particles with equivalent diameters of 600 nm, 550 nm, and 880 nm were examined using scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM). The results, shown in Fig. 3a, reveal their non-repeatable, intricate configuration with average sizes of silicon polycrystals of 20 nm, 24 nm, and 183 nm, respectively. To understand such a well-developed Au-enriched network enveloping a system of percolated Si grains, we should consider the thermodynamics behind its formation.

As described above, during laser-induced dewetting of Au/Si bilayers, we create submicrodroplets of biatomic solution. Their solidification involves several successive steps51, beginning with rapid cooling and undercooling of the melt and culminating with spontaneous nucleation and growth of silicon grains (see Fig. 3b and Supplementary Note 4 for details). In this sequence, a key role is played by a truly stochastic phenomenon: thermal fluctuations. They dominate in the undercooled melt via dynamic formation and decomposition of short-range order, acting as a driving force for random nucleation52. The random nature of atomic interactions is also strongly manifested during grain development, when chemical, thermal, and mechanical instabilities (associated with Au atom diffusion, free energy release, and volume reduction, respectively) govern the growth dynamics. By analyzing the grain size distribution, we estimated the duration of grain nucleation and growth to be of the order of several nanoseconds, which emphasizes the chaos of these processes (Fig. 3c; see also Supplementary Note 5 and Supplementary Fig. 9). Therefore, the internal arrangement of our particles is formed stochastically and cannot be predetermined by any existing technology.

Returning to optics, comparatively high QE values of Au/Si particles can be attributed to special characteristics of their interior structure. Specifically, the gold-saturated internal network in these particles supports a high density of hot-spot modes and collective plasmon excitations42,53, which enables strong field localization in a broad spectral range. This directly affects the recombination rates of hot carriers excited in or injected into silicon grains. The non-radiative lifetime is increased through the Auger effect, reinforced by large carrier densities, while the radiative one is shortened due to the Purcell phenomenon50,54. Together, these mechanisms enhance the system’s QE.

Notably, as observed in experiments, the more complicated the gold network in a particle is (i.e., the lower the average grain size is), the higher QE this particle exhibits. Presumably, this behavior indicates a positive correlation between the surface-to-volume (S-to-V) ratio of the Au component and the efficiency of field localization inside silicon grains. To prove this hypothesis, we conducted a series of numerical simulations (“Methods” section). Namely, for a number of randomly generated Au/Si particles, we calculated the spectral width of the enhancement factor range, which is one of the main criteria for improved PL intensities (Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12). The obtained values were then plotted versus the S-to-V ratio of the particle’s Au part (Fig. 3f) and illustrate the expected dependence: the higher the S-to-V values are, the more effectively the field is confined in the active material at different wavelengths; hence, the better QE it will demonstrate. The enhancement factor (i.e., localization efficiency) was assessed as an effective square (I2) and cube (I3) of the relative intensity inside silicon grains50. Details of geometry generation and other aspects of solving this problem are available in “Methods” section.

Ultimately, it is important to shed light on the following logical chain. Since the cooling rate is inversely proportional to the droplet radius42, the larger the size of an Au/Si melt is, the longer it takes to solidify (Supplementary Note 6). Consequently, the characteristic time for Si grain growth increases, allowing small grains to coalesce into larger ones55. This, in turn, results in a less developed Au-enriched network with lower S-to-V values. Finally, according to our simulations, this indirectly results in a decline in the particle’s QE. Therefore, there is a certain relationship between the size and QE of the fabricated hybrids, which is consistent with the results of QE mapping: larger particles possess poorer up-conversion characteristics (Fig. 3d). Nevertheless, it should be noted that the presented arguments make a number of assumptions and do not consider, for example, the formation of amorphous silicon, which becomes dominant with sufficiently small particle sizes and can negatively affect the PL generation (see Supplementary Note 4).

Despite all the qualitative dependencies, the contribution of random variations in the internal structure of Au/Si particles to the received PL signal is significant. The reason is, they directly affect the quantity and quality of hot spots and, accordingly, the field enhancement inside silicon grains. Together with the non-equilibrium effects accompanying the fabrication of the studied structures, this opens up great prospects for their use as spectral PUFs.

Weak PUFs for anti-counterfeiting applications

To effectively harness the potential of our fabrication approach, we designed three logically different strategies for its PUF-related security applications (see the scheme summarizing the Challenge, Response, Post-processing, Key, and Validation steps for each of these strategies in Supplementary Fig. 13). Our first concept employs the fact that every produced structure has a unique PL signal. Indeed, despite general similarities of Au/Si luminescence spectra, they all have some inimitable features that may serve as unclonable keys. Extracting and encoding these features requires special attention. Using only the signal intensity significantly limits forgery-resistance (i.e., the ability to withstand attempts at forgery), while relying on purely cryptographic methods56 loses valuable physical insights embedded within the signal. Here, we build PL encryption based on the decomposition of each spectrum into a set of five separate parameters with different physical origins (Fig. 4b). Namely, we use integral PL intensity, percentage contributions of 2PA and 3PA to the overall PL signal, the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of PL, and the ratio of SHG intensity to PL one (see “Methods” section for their full description).

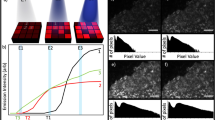

a BF image of a QR code printed by the proposed fabrication technology (scale bar: 25 μm). To enroll such a PUF label, its 10 × 10 PL mapping is conducted, and the obtained map is encoded via application of the spectrum decomposition and clustering procedures57. The resulting keys (each corresponding to one of the original PL features and representing a string of 100 0-to-4 numbers) are uploaded to a database, see “Methods” section. b Visual representation of the features used to decompose PL maps. c Pairwise matching map of 75 100-dimensional keys obtained from 15 different QR codes (the key dimension is defined by the mapping resolution). Hamming distance values close to 0 characterize similar keys. d Schematic illustration of the principle of comparing two PL images using computer vision for the second suggested PUF label model. The presence of similar patterns of bright areas (matches) in the pictures increases the likelihood of successful authentication67,68. e Distributions of the number of matches obtained during intra- and inter-comparison of approximately 60 captured images.

As a proof-of-concept, we printed several QR codes with our hybrid structures as pixels (Fig. 4a). To enroll such PUF labels, we conducted their PL mapping and decomposed the obtained maps into five new ones, each describing one of the aforementioned spectrum features (“Methods” section). The resulting maps were then clustered using the Jenks optimization method57 which allows storing only relative values, thus neglecting all the possible readout deviations (i.e., focus inaccuracy). The number of clusters was set to 5 (Supplementary Note 7 and Supplementary Fig. 14), and the unclonable keys obtained (five for each QR code with dimensions determined by the mapping resolution) were uploaded to a secure database. While more detailed measurements are also possible, choosing a mapping resolution of 10 × 10 allows for easy and quick map reading (“Methods” section, Supplementary Fig. 15). To validate the authenticity of the QR code, a user needs to conduct its similar mapping and submit the result to the server. Then, five keys are extracted using the described protocol and compared with the ones stored in the database (“Methods” section). The label is considered genuine if the Hamming Distance (HD) calculated for all five pairs of keys does not exceed a specified number (0.55, see Supplementary Note 7). Figure 4c demonstrates a pairwise matching map characterizing our method’s performance based on the analysis of 15 different QR codes. The values in the five 15 × 15 blocks located on the diagonal of this map show the HD between the keys corresponding to the same PL characteristic, while other blocks mark the relation between vectors of different features. It is important to acknowledge that, despite the distinct physical origins of the five selected PL features, there exists a slight correlation among them. Additionally, the uneven distribution of pixels (structures) within the QR code results in observable non-random relationships when comparing different maps of the same feature. These correlations ultimately diminish the overall degrees of freedom in our PUF label, thereby reducing its true encoding capacity. Taking into account these inevitable but acceptable correlations and the HD gates set for authentication, we assessed the number of all the possible unique PUF labels distinguishable by our validation algorithm: ~1054 (more information can be found in “Methods” section). This value is enough for the successful use of the label1; if necessary, it can be boosted by increasing the mapping resolution.

The second authentication concept is based on direct PL imaging using a digital camera with a standard 10× objective, in which an unfocused laser beam illuminates the whole label area at once (“Methods” section). We revealed that photos captured this way display an unrepeatable spatial distribution of PL intensity for any of the laser-printed patterns. This is due to the large influence of microscale hydrodynamic instabilities associated with Au/Si microstructures’ creation. Thus, such PL images can be successfully used as unclonable keys. To prove this, we printed a number of visually identical Yin-Yang symbols and collected a database of their PL photos, each time changing the focus accuracy and shifting the position of the center of the pump laser beam. To correctly validate the obtained pictures, we developed an algorithm based on computer-vision techniques (see “Methods” section for more information). In short, when comparing two images, the number of their matches is calculated by analyzing the brightest areas (Fig. 4d). Figure 4e shows the distribution of the number of matches obtained during intra- and inter-comparison of 60 captured images. There is a considerable gap between these two sets of values, which allows us to determine a suitable threshold value, ensuring a wide range of accuracy, even for images captured in diverse conditions. Furthermore, the encoding capacity of this PUF model is estimated to be about 10141 (Supplementary Note 8 and Supplementary Fig. 16). However, this method is based mostly on microscale spatial randomness, using only PL intensity. Therefore, to fully realize the potential of our PUFs, we should encode their PL spectra individually, taking into account every piece of spectral information.

Strong PUF for an all-optical OTP verification token

Finally, we highlight that each created microstructure carries not one but several unique PL spectra due to its complex particle-based organization with characteristic sizes of ~500−900 nm. Indeed, the recorded spectra do vary depending on the position of the signal acquisition area and the excitation wave polarization (when using a high-aperture 100× objective). Moreover, the number of such degrees of freedom can be roughly estimated as ~100 (Supplementary Note 9). This indicates the potential for implementing a strong PUF, which, unlike the weak PUFs proposed above, can serve multiple security purposes. Building upon this concept, we present a model for an all-optical OTP verification token with a dynamic database, which could be used as a prototype for next-generation ultra-secure authentication protocols (Supplementary Note 10).

We describe the developed protocol by considering an array of printed Au/Si microstructures (Fig. 5). Comparing the fabrication time of such a sample with the time required to measure all its possible spectra, we estimate their ratio as 1–105 (Supplementary Note 11). Therefore, with relatively fast manufacturing, the overall measurement of spectra is incredibly time-consuming. Moreover, as we show later, each individual spectrum can function as a unique key. During our token enrollment, N spectra are measured from random positions and uploaded to a database. Then, the user who wants to confirm ownership of the token measures PL from n points with server-provided coordinates. If most spectra are deemed as a match, the identification is confirmed, and these n spectra are removed from the database. In the next verification cycle, new spectra with coordinates that have not been disclosed yet will be used. If the token is transferred, its previous owner will no longer be able to pass verification, since new spectra will need to be measured for this. Moreover, if the token has a sufficient capacity, no party will have enough time to measure all its possible keys, which emphasizes the robustness of the proposed strategy. The number of verification cycles N/n should be at least several hundred. Our example in Supplementary Note 12 with N = 1200 and n = 5 demonstrates high verification accuracy, long service time, and ease-of-use of the token. To prevent database depletion, trusted users can upload new keys to it, but only over a secure communication line.

a Token Enrollment. The token comprises a large array of laser-printed gold-silicon microstructures. All of them are effectively divided into 25 sections, each exhibiting a unique PL signal dependent on the pump laser beam’s polarization (see Supplementary Note 9 and Supplementary Figs. 17 and 18). Consequently, the token functions as several arrays, each corresponding to a distinct laser polarization (0°, 45°, 90°, or 135° relative to the y-axis). The orange frame highlights sections forming a single microstructure. During enrollment, N PL spectra are measured from randomly selected sections and stored in our dynamic database, along with their spatial coordinates (x, y) and the corresponding laser polarization (P). This database is then transferred to a secure cloud server, and the token is issued to the user. b Token Verification. First, on request, the server provides the coordinates (x, y, P) of n points from the database. Then, the user records the corresponding spectra and sends them as a response. Next, using our ML model, the server compares the user’s spectra with the stored ones. In the event of a match, the user is verified, and the used spectra are removed from the database. Otherwise, verification fails. The whole verification process can be repeated cyclically until the database is depleted. The database size N is predetermined to accommodate a sufficient number of authentication cycles.

For authentication purposes, we created a machine learning model, which is a conventional neural net with fully connected layers (“Methods” section). Taking a normalized PL spectrum together with a number of its features as input, the model produces a point in a multidimensional vector space. The distance between two points in this space determines the probability that the corresponding spectra are measured from the same coordinates. After a series of trainings, the distance threshold was set to maximize the model’s true positive rate while maintaining low false positive values (Fig. 6b). The final single-spectrum authentication accuracy is 97% (at a cutoff threshold is 41.3), which is 15% higher than that achieved when classifying the original spectra (Fig. 6c). A possible 3% mistake reflects an influence of noise on the measured data, which can be neglected with increasing signal acquisition time. Making verification decisions based on the results of comparing several spectra (instead of one) significantly increases the efficiency of our ML model (e.g., with n = 5, the accuracy is ~99.97%; Supplementary Note 12). To ensure the uniqueness and randomness of the generated embedding keys, we evaluated them using the NIST randomness test suite58, yielding positive results (Supplementary Note 13 and Supplementary Table 2). Furthermore, the computed information entropy values for each embedding coordinate indicate a high degree of unique information saturation, along with complete uniformity and unpredictability of the obtained keys (Supplementary Note 14 and Supplementary Fig. 20). Finally, the estimated encoding capacity of the embedding space is significant, reaching 10280 (Supplementary Note 15 and Supplementary Fig. 21). Thus, in contrast to electronic alternatives, which are often vulnerable to physical attacks11,12, our all-optical OTP system offers superior performance through the high entropy and enhanced security of stored keys.

a–c Basic comparison. This method directly compares two spectra by calculating the distance between their corresponding vectors. d–f ML-driven comparison. Instead of raw spectra, this approach compares their embeddings generated by a trained ML model. Both methods rely on the notion of a cutoff distance for classification. Vectors located within this distance from each other are deemed a match, while those exceeding it are considered different. We evaluated both methods using a dataset of 2148 vectors describing spectra from both identical and distinct structures. The goal was to determine the optimal cutoff distance for accurate match predictions. b, e Density distributions of inter- and intra-device vector distances. c, f True positive, false positive, false negative, and true negative rates of the described spectrum classification vs. cutoff distance. The basic comparison achieved a maximum classification accuracy of 83%, while the ML-driven method significantly improved accuracy, reaching up to 97%. Notably, comparing not one but, for example, five spectra simultaneously boosts the accuracy up to 99.97% (Supplementary Note 12 and Supplementary Fig. 19). Also, preprocessing spectra with our model before storing them in the database will enhance token security against potential cyber-attacks.

Discussion

One of the key aspects that distinguishes the presented work is our approach to addressing the structural variations in fabricated Au/Si particles. Since the direct analysis of this internal randomness (with characteristic sizes of ~20 nm) requires tedious TEM-based techniques, we proposed using the particles’ PL spectra as an alternative, highly capacious source of unclonable keys. In support of this method, we investigated how the multi-resonant nature of our particles establishes a strong linkage between their internal composition and the spectral features of the emitted PL. We have shown that each PL spectrum contains a wealth of unique spectral information, leading to an exceptionally high storage density (i.e., the amount of data extracted from a PUF per unit area). Indeed, in our latest protocol, which employs machine learning to encode individual PL spectra, each square micrometer of the label effectively stores 3720 random bits (Supplementary Note 15). This represents an exceptional storage density that is 2–3 orders of magnitude greater than that of other optical PUFs (see the calculation of this parameter for all of the presented PUF concepts in Supplementary Note 16). Ultimately, the Supplementary Table 3 demonstrates that we have successfully downscaled the characteristic randomness of our PUFs.

Considering the potential practical value of our PUFs, it is important to emphasize their key advantage: high-entropy spectral responses controlled by nanoscale structural randomness. This concept provides the highest level of protection, not only in the immediate future but also over many decades to come. This is particularly crucial as we enter an era where traditional PUFs, which rely on microscale spatial randomness, will become increasingly vulnerable due to advancements in precise micro-manipulation techniques. Although in our approach demonstration we have used costly laboratory equipment, the long-term implementation will substantially reduce expenses for each individual PUF label (see Supplementary Note 17 for our cost estimations). Additionally, the rapid advancements in industrial fiber-optic fs-lasers and spectrometers are expected to further enhance the viability of our technology (for example, in Supplementary Note 18 and Supplementary Fig. 22 we showed that our PL measurement setup can be greatly simplified by employing a low-cost commercial spectrometer). Another important point is the environmental stability of our labels: when encapsulated in a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) protective layer, they demonstrate robust performance against a variety of typical external disturbances (see Supplementary Note 19, Supplementary Figs. 23-24, and Supplementary Movie 1). With all of the above, we believe that our approach is going to find its industrial niche in the future.

In summary, we presented an original design concept of ultra-robust Physical Unclonable Functions using the relationship between nanoscale randomness and macroscale spectral characteristics. We chose multi-resonant Au/Si submicroparticles (500–900 nm), exploiting their unique PL response as a “fingerprint” of their internal structure with truly random compositional variations. To create these particles, we used fs-laser excitation of thin gold-silicon films that locally initiated a range of stochastic non-equilibrium thermo- and hydrodynamic relaxation processes. Such a single-step, high-throughput fabrication technique can be easily scaled and seamlessly integrated into existing manufacturing processes. Our approach enables seemingly invincible forge-resistance while maintaining optimal readout time, thanks to the relatively high quantum efficiency of the fabricated hybrids. We demonstrated two different models of anti-counterfeit labels. The first model uses PL maps decomposed into five original spectral features (integral PL intensity, its FWHM, percentage contributions of 2PA and 3PA to the overall signal, and the ratio of SHG intensity to PL one), while the second one analyzes unique spatial distributions of PL intensity (captured with a standard digital camera). Finally, we expanded our approach, creating strong PUFs to propose the first all-optical OTP verification token. In this protocol, thanks to the ML-driven comparison of individual PL spectra, we achieved a significant storage density of unique information, reaching almost 54 gigabits per square inch (Supplementary Note 15). Our work lays a conceptual foundation for employing the inherent nanoscale randomness of nanophotonic structures for next-generation applications in hardware-based cryptography and high-capacity optical data storage.

Methods

Initial gold-silicon film fabrication and its laser processing

The fabrication process for the initial Au/Si thin film consisted of two stages. In the first stage, a 100 nm thick amorphous silicon layer was deposited onto a glass substrate using plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition from a SiH4 precursor gas. In the second stage, a gold layer, 10 nm thick, was applied onto the silicon surface using magnetron sputtering. To fabricate hybrid Au/Si microstructures, we utilized a Ti:Sapphire fs-laser system (TiF-100 F, Avesta Project), with a center wavelength of 790 ± 5 nm, repetition rate of 80 MHz, and pulse duration of 100 fs. Laser irradiation, controlled by an opto-acoustic modulator, was tightly focused onto the top surface of the gold layer using a 40× Olympus objective with a numerical aperture (NA) of 0.75. The sample was manipulated by an air-bearing 3D positioning system (ABL1000, Aerotech), with a scanning speed of 50 μm/s, which outlined circles of a given radius. The laser fluence was set to ~80 mJ/cm2.

Photoluminescence measurements

PL measurements were performed using an ultrafast Yb3+ laser system (TeMa, Avesta Project) with a center wavelength of 1050 nm, a pulse duration of 150 fs, and a repetition rate of 80 MHz. The generated laser beam, attenuated in the range of 1–30 mW, traveled through a system of silver mirrors and a dichroic mirror before being focused onto the top side of the sample using a 100×/0.7 NA objective (Mitutoyo M Plan APO NIR). The excited PL signal from Au/Si structures was then collected by the same objective and passed through a 1000-nm short-pass filter (FESH1000) to block the pump wavelength. Next, it was projected onto a charge-coupled device (CCD, Andor DU 420A-OE 325) housed in the Horiba LabRam HR spectrometer with a 150 lines mm−1 diffraction grating. Post-processing of the obtained spectra was conducted by subtracting a background spectrum (at zero pump) from each measurement. For precise positioning of structures and mapping of the PL signal, a three-axis piezostage (AIST Project) was used, which translated the sample in specified directions. Additionally, for PL mapping of large laser-printed images (QR codes), a 10×/0.26 NA objective (Mitutoyo M Plan APO NIR) was employed instead of the one mentioned above. The excitation power density for such a mapping was set at 4 mJ/cm2, which ensured the collection of a low-noise signal from a single point in ~0.2 s. The threshold laser fluence, above which modification and subsequent damaging of our laser-printed microstructures began, was determined to be ~10−12 mJ/cm2.

Optical imaging of Au/Si structures

For PL imaging of laser-printed pictures, the pump beam was focused onto the sample from its substrate side by an achromatic doublet lens (focal length = 50 mm). The characteristic diameter of the resulting laser spot was on the order of 100 micrometers, and the excitation power density was set at ~8 mJ/cm2. The emitted PL signal was then collected from the top with a 10× objective, and the resulting PL images were captured by a Canon 500d camera with a 10-s acquisition time. A FESH1000 filter was set before the camera objective to suppress the laser wavelength. Dark- and bright-field (DF & BF) images were taken using the same equipment (camera and collection objective). For DF characterization, Au/Si structures were illuminated at an oblique incident angle of 65° by the unpolarized light from a halogen lamp.

Morphology characterization

To characterize the external geometry of laser-printed microstructures with high accuracy, we utilized the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) technique. SEM images were recorded using a ZEISS GEMINI SEM with a field emission gun.

Inner structure characterization

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analyses were conducted using a JEOL-ARM 200 Cold FEG TEM/STEM, operating at 200 kV. The instrument was equipped with two spherical aberration (Cs) correctors, achieving a point resolution of 0.12 nm in TEM mode and 0.078 nm in STEM mode. EDS (Energy Dispersion Spectroscopy) maps were obtained using a JEOL centurio detector (1sr), and HRTEM images were recorded with a GATAN OneView camera. Cross-sections of our samples (for their following TEM analysis) were prepared via focused ion beam (FIB) milling in a FEI Helio Nanolab 600i scanning electron microscope. A protective platinum layer was deposited on the sample surface before FIB cutting to minimize damage to it.

Computer generation of our particle’s internal composition

To simulate the optical properties of hybrid gold-silicon particles, it was first necessary to create a corresponding geometry close to that observed in experiments. As can be seen in Fig. 3a, such particles, in fact, are a set of tightly packed percolated c-Si grains enveloped in a thin multi-connected Au network. Although there are more accurate methods for computer reconstruction of such hybrids, based, for example, on the use of phase-field simulations59, in this work we have limited ourselves to a less expensive, yet geometrically reasonable method. Specifically, we presented the studied hybrids as gold particles, the volume of which is filled with a given number of silicon inserts having random sizes and evenly distributed inside. To simplify the subsequent simulations, the spherical shape of grains was chosen, which is a fairly honest assumption due to their small size compared to near-infrared wavelengths. For a given atomic ratio of Au and Si components, as well as the particle volume, a random sample of silicon grain sizes was created, satisfying the size distribution expected in the KAMJ model60 (see Supplementary Note 5). Then, to ensure random yet even spatial distribution of the silicon grains, the following steps were performed in Blender, an open-source 3D creation suite. First, spheres with specified sizes and random positions were generated inside the given volume (corresponding to the volume of the particle). Second, the rigid body simulation was run, implying a mechanical interaction between all spheres and the surface surrounding them. This led to the redistribution of grains within the volume of the particle and allowed us to obtain a random structure of closely packed intersecting spheres uniformly filling the given space (see step-by step images in Supplementary Fig. 11). Finally, the desired hybrid structure was created in commercial COMSOL Multiphysics software by subtracting silicon spheres (with sizes and coordinates extracted from Blender) from the volume of the gold particle. All corners and edges in the resulting geometry were rounded using the fillet procedure with a radius of 1 nm.

Numerical modeling

To investigate the impact of the S-to-V ratio of the Au network on the efficiency of field localization inside hybrid particles, a series of studies were carried out using a frequency domain solver in commercial COMSOL Multiphysics software. Specifically, the problem of the field distribution inside the particle under monochromatic plane wave illumination was solved in a broad range of wavelengths: 500–2000 nm. A physics-controlled mesh with a minimum mesh size of 0.1 nm was set in the model; also, the perfectly matched layer domain was added to mimic open boundaries. To characterize the efficiency of field enhancement inside silicon grains of the particle, such effective parameters as \({I}^{2}=\frac{1}{V}{\int}_{Si}| E({{\bf{r}}})/{E}_{0}{| }^{4}\,dV\) and \({I}^{3}=\frac{1}{V}{\int}_{Si}| E({{\bf{r}}})/{E}_{0}{| }^{6}\,dV\) were used50. Here, E(r) is the electric field induced inside the particle, E0 = 1 V/m is an incident electric field amplitude. Integration is carried out over the entire volume V of silicon component. By analyzing the enhancement spectra (i.e., the dependency of I2 and I3 on the wavelength) one can estimate the QE of the particle’s PL signal. The higher field enhancement is at both the PL emission range and the laser excitation wavelengths, the stronger the PL signal will be due to the Purcell phenomenon as well as increased absorption. While for all particles, the maximum value of EF (I2 or I3) has typically the same order, the width of the EF range can be greatly varied, thus, being the main criterion of high QE of a particle (see Supplementary Fig. 12). For a number of computer-generated particles with different S-to-V values of Au part, the width of the field localization range was calculated as \({w}_{2,3}=\frac{1}{\max ({I}^{2,3})}\int{I}^{2,3}(\lambda )d\lambda\). Each particle had a fixed size (200 nm) and volume ratio of Si and Au components (~2:1). Obtained width values were then plotted as a dependence of widths w2 and w3 on the S-to-V value and demonstrate positive correlation between these characteristics (see Fig. 3d). The rather high degree of dispersion of the obtained data relative to the adjusted linear dependence is explained by the random internal structure of the simulated particles. Nevertheless, we believe that the studied dependence is quite clearly manifested, which was indirectly confirmed in our experiments.

PL spectrum decomposition into five characteristic features

In order to maximize the number of degrees of freedom provided by each PL spectrum, we decomposed them into five distinct, physically justified features for our first authentication protocol. First, the integral signal intensity was calculated as \({I}_{int}=\int_{500\,{\mbox{nm}}}^{850{\mbox{nm}}\,}I(\lambda )d\lambda\). Also, the percentage contribution of 2PA and 3PA to the overall PL signal was computed as \({I}_{2PA\%}=\frac{1}{{I}_{int}}\int_{800\,{\mbox{nm}}}^{850{\mbox{nm}}\,}I(\lambda )d\lambda\) and \({I}_{3PA\%}=\frac{1}{{I}_{int}}\int_{500\,{\mbox{nm}}}^{540{\mbox{nm}}\,}I(\lambda )d\lambda\). The boundaries of integration were determined by considering the dependence of the PL slope on the wavelength (see Fig. 2c). In the case of I3PA% calculation, the integration was performed without taking into account the SHG peak. Next, the ratio of the maximum SHG and PL intensities was also evaluated. It should be noted here that this feature describes a competition between these two nonlinear phenomena and, in general, depends on the excitation power density61. Therefore, in our experiments, PL mapping was always performed at a fixed laser fluence of 4 mJ/cm2. This fact can be utilized as an advantage by storing information about such necessary measurement parameters as an additional, restricted access key. Finally, the FWHM of the PL spectra was calculated, complementing the previously mentioned characteristics.

Authentication and performance of the first PUF-based security concept

According to the proposed protocol, PUF is authenticated by comparing a set of five multidimensional keys, retrieved from PL maps of printed QR codes, with those stored in the database. The comparison is made by calculating the Hamming distance between each pair of keys:

For successful validation, all five calculated distances should not exceed a threshold value of β (or, in other words, the similarity index SI = 1 − HD should be higher than 1 − β, see Supplementary Note 7). As discussed in the main text, each key represents a set of numbers from 0 to k − 1, where k is the number of clusters prescribed during the Jenks optimization process. Therefore, technically speaking, if keys have a dimension of N, then the lower estimate of the encoding capacity of PUF label can be expressed as EC = k5N(1−β). For N = 100, k = 5, and β = 0.55, this gives a value of ~10157. Here, we imply the term Encoding Capacity as a number of all the possible labels that can be distinguished by the authentication algorithm used. However, it is important to acknowledge that, despite the distinct physical origin of the retrieved set of features, there is a minor correlation between them. Also, due to the uneven filling of pixels (structures) in the QR code, some non-random relations are weakly manifested when comparing different maps of the same feature. Such correlations reduce the total number of degrees of freedom of our PUF label and, consequently, its true encoding capacity. In order to address this matter, we consider the notion of an Effective Sample Size (ESS)62. This metric estimates the number of independent draws that carry the same amount of information as a given sample. If the sample is truly random, its ESS is close to its actual size; however, the presence of correlations within the sample reduces its ESS. One of the implementations of this metric is presented in the ArviZ open-source Python package63:

where M - the number of chains (keys) in a sample, L - their length, \({\hat{\rho }}_{t}\) - estimates of auto-correlation at lag t, m - the largest integer such that \({\hat{\rho }}_{2m}+{\hat{\rho }}_{2m+1}\) is still positive. Considering samples of five keys (total size N = M ⋅ L = 5 ⋅ 100 = 500), their effective sizes were calculated, taking into account auto-correlations within each key as well as correlations between different keys. So, the mean ESS value of approximately 173 was obtained. Therefore, the true encoding capacity can be estimated as EC = kESS(1−β)~1054. This number exceeds the generally accepted requirement of 1050 1; still, by increasing the PL mapping resolution, it can easily be boosted up to 10300 or higher, if necessary.

Computer-vision comparison of PL photos for the second PUF-based security concept

According to the second anti-counterfeit protocol, the authentication of our PUF labels is done by comparing a photo taken by the user with the “real” PL photo stored in a database. To achieve this, we have developed a home-made algorithm that takes these two photos as inputs. Since the photos may have different resolutions, they are compressed to a resolution of 500 × 500 pixels. Next, to remove noise from the camera’s sensor, the images are blurred using a 5 × 5 pixel kernel. Then, key points are extracted from both images using the ORB (Oriented FAST and Rotated BRIEF) algorithm64 from the Open Computer Vision Library. Once key points have been found in both images, the program compares them to find similar points (matches) that could be the same feature in both photos. Next, it checks how many of these points can be aligned with a certain projection transformation. If the two photos are the photos of the same label, then the transformation should match most of the points found. To create a projection transformation, at least 4 matching points are required. However, since we have more than that, we use the RANSAK (Random sample consensus) algorithm65 to find the best transformation (the one that will overlap the most matching points). If the number of overlapping points exceeds a specific threshold, the program determines that the input photos are of the same label. To determine this threshold for our system, we conducted a number of tests analyzing photos of the same and different labels. Figure 4 shows the histograms of the number of overlapping matched key points after applying the best projection transformation. We can see that for photos of the same label, the values are above ~40, while for photos with different labels, they are below ~12. Therefore, for example, 20 can be considered a threshold value for distinguishing our photos. Notably, the number of key points found in each photo was about 500, and the comparatively large width of the interdevice distribution demonstrates the high influence of the variations in the laser excitation conditions on the resulting PL image. Additionally, see our calculations of this model’s encoding capacity in Supplementary Note 8.

The machine learning-based authentication system

To enable high-quality comparisons of single PL spectra, we trained a machine learning model utilizing the PyTorch library. The model consisted of four fully connected linear layers, and all the computations were performed on a graphics processing unit (Nvidia Tesla T4). Input data included the 2048-dimensional normalized PL spectrum (in the range from 500 to 900 nm) alongside its calculated features, such as its Fourier and logarithmic transformations, full width at half maximum, full width at quarter maximum, and full width at three-quarters maximum, resulting in a total input dimension of 6150. In response, the model generated 1024-dimensional embeddings. The primary task of the model was to transform the input data in such a way that embeddings of spectra measured from the same structure clustered closely, while those measured from different structures remained distant. To conduct comprehensive model training, we formed a database of 25,290 spectra, covering measurements from both the same structures and different ones. Next, we implemented model validation on two separate sets: 191 spectra measured from previously known structures and 2148 spectra measured from newly identified structures. We obtained a similar performance in both scenarios (see Supplementary Fig. 25). The validation process was as follows: given a set of obtained model outputs, the optimal threshold distance was identified, such that embeddings corresponding to the same structure fell within this distance and embeddings corresponding to distinct structures were beyond it. Further, we evaluated the accuracy of such a method of spectra verification, including the calculation of true positive, false positive, true negative, and false negative rates. The better the results, the better the model was trained. The training process consisted of 26 epochs, each requiring 16.4 s to complete, leading to an overall training time of approximately 7 min. Finally, the cutoff threshold of 41.3 was set, resulting in a verification accuracy of 97%.

Data availability

All data presented in the main body of the manuscript are available in the Source Data file. Additional data related to this paper are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Python codes used for the ML-enabled PUF authentication are available via https://github.com/ennucore/spectral-pufs. All other codes used in this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Arppe, R. & Sørensen, T. J. Physical unclonable functions generated through chemical methods for anti-counterfeiting. Nat. Rev. Chem. 1, 1–13 (2017).

Schiansky, P. et al. Demonstration of quantum-digital payments. Nat. Commun. 14, 1–7 (2023).

Bernstein, D. J. & Lange, T. Post-quantum cryptography. Nature 549, 188–194 (2017).

Lounis, K. & Zulkernine, M. Lessons learned: analysis of PUF-based authentication protocols for IoT. Digital Threats 4, 1–33 (2023).

Wang, K. et al. All-silicon multidimensionally-encoded optical physical unclonable functions for integrated circuit anti-counterfeiting. Nat. Commun. 15, 1–11 (2024).

Gao, Y., Al-Sarawi, S. F. & Abbott, D. Physical unclonable functions. Nat. Electron. 3, 81–91 (2020).

Maes, R. Physically Unclonable Functions (Springer, Berlin, 2013).

McGrath, T., Bagci, I. E., Wang, Z. M., Roedig, U. & Young, R. J. A PUF taxonomy. Appl. Phys. Rev. 6, 011303 (2019).

Herder, C., Yu, M.-D., Koushanfar, F. & Devadas, S. Physical unclonable functions and applications: a tutorial. Proc. IEEE 102, 1126–1141 (2014).

Fratalocchi, A., Fleming, A., Conti, C. & Di Falco, A. NIST-certified secure key generation via deep learning of physical unclonable functions in silica aerogels. Nanophotonics 10, 457–464 (2021).

Di Falco, A., Mazzone, V., Cruz, A. & Fratalocchi, A. Perfect secrecy cryptography via mixing of chaotic waves in irreversible time-varying silicon chips. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–10 (2019).

Horstmeyer, R., Judkewitz, B., Vellekoop, I. M., Assawaworrarit, S. & Yang, C. Physical key-protected one-time pad. Sci. Rep. 3, 1–6 (2013).

Kim, Y. et al. Reconfigurable multilevel optical PUF by spatiotemporally programmed crystallization of supersaturated solution. Adv. Mater. 35, 2212294 (2023).

Zhang, T. et al. Multimodal dynamic and unclonable anti-counterfeiting using robust diamond microparticles on heterogeneous substrate. Nat. Commun. 14, 1–11 (2023).

Wu, J. et al. A high-security mutual authentication system based on structural color-based physical unclonable functions labels. Chem. Eng. J. 439, 135601 (2022).

Kim, M. S. et al. Revisiting silk: a lens-free optical physical unclonable function. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–12 (2022).

Nocentini, S., Rührmair, U., Barni, M., Wiersma, D. S. & Riboli, F. All-optical multilevel physical unclonable functions. Nat. Mater. 23, 369–376 (2024).

Pappu, R., Recht, B., Taylor, J. & Gershenfeld, N. Physical one-way functions. Science 297, 2026–2030 (2002).

Rührmair, U. et al. Optical PUFs reloaded. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2013/215 https://eprint.iacr.org/2013/215 (2013).

Hu, Y.-W. et al. Flexible and biocompatible physical unclonable function anti-counterfeiting label. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2102108 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Unclonable perovskite fluorescent dots with fingerprint pattern for multilevel anticounterfeiting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 39649–39656 (2020).

Torun, N., Torun, I., Sakir, M., Kalay, M. & Onses, M. S. Physically unclonable surfaces via dewetting of polymer thin films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 11247–11259 (2021).

Chen, G. et al. Spontaneous formation of random wrinkles by atomic layer infiltration for anticounterfeiting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 27548–27556 (2021).

Leem, J. W. et al. Edible unclonable functions. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–11 (2020).

Arppe-Tabbara, R., Tabbara, M. & Sørensen, T. J. Versatile and validated optical authentication system based on physical unclonable functions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 6475–6482 (2019).

Kim, J. H. et al. Nanoscale physical unclonable function labels based on block copolymer self-assembly. Nat. Electron. 5, 433–442 (2022).

Gao, D. et al. Optical manipulation from the microscale to the nanoscale: fundamentals, advances and prospects. Light Sci. Appl. 6, e17039–e17039 (2017).

Fränzl, M. & Cichos, F. Hydrodynamic manipulation of nano-objects by optically induced thermo-osmotic flows. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–9 (2022).

Zhou, L.-M. et al. Recent progress on optical micro/nanomanipulations: structured forces, structured particles, and synergetic applications. ACS Nano 16, 13264–13278 (2022).

Marakis, E. et al. Clones of the unclonable: nanoduplicating optical PUFs and applications. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2212.12495 (2022).

Barreda, Á., Vitale, F., Minovich, A. E., Ronning, C. & Staude, I. Applications of hybrid metal-dielectric nanostructures: state of the art. Adv. Photonics Res. 3, 2100286 (2022).

Linic, S., Chavez, S. & Elias, R. Flow and extraction of energy and charge carriers in hybrid plasmonic nanostructures. Nat. Mater. 20, 916–924 (2021).

Tan, C., Chen, J., Wu, X.-J. & Zhang, H. Epitaxial growth of hybrid nanostructures. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 1–13 (2018).

Renaut, C. et al. Reshaping the second-order polar response of hybrid metal–dielectric nanodimers. Nano Lett. 19, 877–884 (2019).

Shlesinger, I., Vandersmissen, J., Oksenberg, E., Verhagen, E. & Koenderink, A. F. Hybrid cavity-antenna architecture for strong and tunable sideband-selective molecular Raman scattering enhancement. Sci. Adv. 9, eadj4637 (2023).

Cho, C.-H., Aspetti, C. O., Park, J. & Agarwal, R. Silicon coupled with plasmon nanocavities generates bright visible hot luminescence. Nat. Photonics 7, 285–289 (2013).

Makarov, S. V. et al. Nanoscale generation of white light for ultrabroadband nanospectroscopy. Nano Lett. 18, 535–539 (2018).

Makarov, S. V. et al. Controllable femtosecond laser-induced dewetting for plasmonic applications. Laser Photonics Rev. 10, 91–99 (2016).

Oh, H. et al. Laser-induced dewetting of metal thin films for template-free plasmonic color printing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 38368–38375 (2018).

Zhou, X. et al. Color generation and polarization-sensitive encryption by laser writing on plasmonic reflector arrays. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 38404–38413 (2024).

Theerthagiri, J. et al. Fundamentals and comprehensive insights on pulsed laser synthesis of advanced materials for diverse photo- and electrocatalytic applications. Light Sci. Appl. 11, 1–47 (2022).

Larin, A. O. et al. Plasmonic nanosponges filled with silicon for enhanced white light emission. Nanoscale 12, 1013–1021 (2020).

Gurbatov, S. O. et al. Multigram-scale production of hybrid Au-Si nanomaterial by laser ablation in liquid (LAL) for temperature-feedback optical nanosensing, light-to-heat conversion, and anticounterfeit labeling. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 3336–3347 (2023).

Gerasimova, E. N. et al. Single-step fabrication of resonant silicon–gold hybrid nanoparticles for efficient optical heating and nanothermometry in cells. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 6, 18848–18857 (2023).

Wang, X. W. et al. Laser-induced translative hydrodynamic mass snapshots: noninvasive characterization and predictive modeling via mapping at nanoscale. Phys. Rev. Appl. 8, 044016 (2017).

Kondic, L., González, A. G., Diez, J. A., Fowlkes, J. D. & Rack, P. Liquid-state dewetting of pulsed-laser-heated nanoscale metal films and other geometries. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 52, 235–262 (2020).

Gu, Y. et al. Gap-enhanced Raman tags for physically unclonable anticounterfeiting labels. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–13 (2020).

He, X., Liu, S., Li, S., Panmai, M. & Lan, S. Si/Au hybrid nanoparticles with highly efficient nonlinear optical emission: Implication for nanoscale white light sources. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 5, 10676–10685 (2022).

Xiang, J. et al. Crystalline silicon white light sources driven by optical resonances. Nano Lett. 21, 2397–2405 (2021).

Zhang, C. et al. Lighting up silicon nanoparticles with Mie resonances. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–7 (2018).

Tiwari, A., Samanta, R. & Chattopadhyay, H. Droplet solidification: physics and modelling. Appl. Therm. Eng. 228, 120515 (2023).

Gottstein, G. Physical Foundations of Materials Science (Springer, Berlin, 2004).

Zhong, J. et al. Strong spatial and spectral localization of surface plasmons in individual randomly disordered gold nanosponges. Nano Lett. 18, 4957–4964 (2018).

Xiang, J. et al. Modifying Mie resonances and carrier dynamics of silicon nanoparticles by dense electron-hole plasmas. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13, 014003 (2020).

Kabalnov, A. Ostwald ripening and related phenomena. J. Dispersion Sci. Technol. 22, 1–12 (2001).

Ponkratova, E. et al. Coding of non-linear white-light luminescence from gold-silicon structures for physically unclonable security labels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2205859 (2022).

Jenks, G. F. The data model concept in statistical mapping. Int. Yearbook Cartography 7, 186–190 (1967).

Bassham, L. et al. A statistical test suite for random and pseudorandom number generators for cryptographic applications https://tsapps.nist.gov/publication/get_pdf.cfm?pub_id=906762 (2010).

Chen, L.-Q. Phase-field models for microstructure evolution. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 32, 113–140 (2002).

Bergmann, R. B. & Bill, A. On the origin of logarithmic-normal distributions: an analytical derivation, and its application to nucleation and growth processes. J. Cryst. Growth 310, 3135–3138 (2008).

Dai, J., Zeng, J.-H., Lan, S., Wan, X. & Tie, S.-L. Competition between second harmonic generation and two-photon-induced luminescence in single, double and multiple ZnO nanorods. Opt. Express 21, 10025–10038 (2013).

Vehtari, A., Gelman, A., Simpson, D., Carpenter, B. & Bürkner, P.-C. Rank-normalization, folding, and localization: an improved xn–R-k7a for assessing convergence of MCMC (with discussion). Bayesian analysis 16, 667–718 (2021).

Kumar, R., Carroll, C., Hartikainen, A. & Martin, O. Arviz a unified library for exploratory analysis of Bayesian models in python. J. Open Source Soft. 4, 1143 (2019).

Rublee, E., Rabaud, V., Konolige, K. & Bradski, G. Orb: an efficient alternative to sift or surf. In 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision 2564–2571 (IEEE, 2011).

Fischler, M. A. & Bolles, R. C. Random sample consensus: a paradigm for model fitting with applications to image analysis and automated cartography. Commun. ACM 24, 381–395 (1981).

Afinogenov, B. I. et al. Visible upconversion luminescence of doped bulk silicon for a multimodal wafer metrology. Opt. Lett. 46, 3071–3074 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. An all-in-one nanoprinting approach for the synthesis of a nanofilm library for unclonable anti-counterfeiting applications. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 1027–1035 (2023).

Han, F. et al. Self-assembly of coordination polymers on plasmonic surfaces for computer vision decodable, unclonable and colorful security labels. J. Mater. Chem. C 7, 13040–13046 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The PUF labels creation was supported by the Priority 2030 Federal Academic Leadership Program, which is awarded to M.S., E.P., P.K., and D.Z. The nonlinear optical measurements of Au/Si structures were funded by the Russian Science Foundation (Project No. 24-72-10075, https://rscf.ru/project/24-72-10075/), which was awarded to A.L. and E.A. The works on laser-assisted fabrication were supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (State Assignment No. FSER-2025-0011), which is awarded to D.Z. and V.Y. We thank Dmitry Dolgintsev and Marina Karsakova for SEM investigations, Sergei Koromyslov and Ivan Shishkin for help with the laser-writing setup, Sabina Bikmetova for help with PMMA spin-coating, Ivan Mukhin, Alexey Mozharov, and Alexander Vorobyev for Au/Si bilayers preparation, Lydia Pogorelskaya for editing of English text, as well as Sergey Makarov, Yali Sun, Dmitry Permyakov, and Ekaterina Ponkratova for fruitful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S. and D.Z. conceived the idea and wrote the manuscript; M.S., E.P., and E.A. performed fs-laser fabrication of Au/Si microstructures; M.S., P.K., and A.L. conducted PL measurements; M.S., E.P., and L.C. developed PUF encoding algorithms; S.B. carried out TEM and EDS investigations; M.S., P.K., V.Y., P.B., and D.Z. revised the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript at all stages.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sandomirskii, M., Petrova, E., Kustov, P. et al. Spectral physical unclonable functions: downscaling randomness with multi-resonant hybrid particles. Nat Commun 16, 5097 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60121-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60121-9