Abstract

The surface morphology and shape of crystalline nanowires significantly influence their functional properties, including phonon transport, electrocatalytic performance, to name but a few. However, the kinetic pathways driving these morphological changes remain underexplored due to challenges in real-space and real-time imaging at single-particle and atomic resolutions. This study investigates the dynamics of shell (Au, Pd, Pt, Fe, Cu, Ni) deposition on AuAg alloy seed nanowires during core-shell formation. By using chiral/non-chiral seed nanowires, advanced imaging techniques, including liquid-phase transmission electron microscopy (LPTEM), cryogenic TEM, and three-dimensional electron tomography, a three-step deposition process is revealed: heterogeneous nucleation, nanoparticle attachment, and coalescence. It is found that colloidal Ostwald ripening, metal reactivity, and deposition amount modulate nanoparticle size and surface roughness, shaping final morphologies. Noble metal nanoparticles (Au, Ag, Pd, Pt) coalesce with seed nanowire along the 〈111〉 direction, distinct from that of other metals. These findings are consistent across different metals, including Ru, Cu, Fe, and Ni, highlighting the hypothesis of these processes in nanowire formation. These findings enhance traditional crystallographic theories and provide a framework for designing nanowire morphology. Additionally, our imaging techniques may be applied to investigate phenomena like electrodeposition, dendrite growth in batteries, and membrane deformation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Understanding and controlling the growth of colloidal nanocrystals hold significant importance for creating functional materials and nanodevices of the future1,2,3,4,5,6,7. The well-known growth model proposes initial nucleation followed by growth via monomer attachment or particle fusion1,8,9,10. The growth of gold (Au) nanowires often employs a seed-mediated approach where small Au nanoparticles (seeds) serve as the starting point for elongation into nanowires11. During the growth of Au nanowires, twin boundaries can form, which can affect their mechanical and electronic properties12. The underlying mechanisms that lead to these twin boundaries are still not fully understood. Understanding the precise growth mechanisms, including the role of different surfactants and reducing agents, is crucial for controlling the size and shape of the nanowires. Silver (Ag) nanowires often exhibit different surface properties depending on their facets. For instance, controlling the growth environment can enhance specific facets, such as the {100} or {110} planes, leading to variations in optical and catalytic properties13. Alloying noble metals such as Au and Ag can result in unique properties, whereas controlling the phase composition of these alloyed nanowires is challenging14. Previous research has revealed that the morphology, composition, and diameter of Au nanowires can be controlled by varying the concentration of growth solutions and reaction conditions15,16. Some recent work focuses on the design and synthesis of nanowires with the control of organic ligands which is a kind of template or surfactant to induce the metal deposition17,18,19. Precise control over synthetic parameters is necessary to achieve metal nanowires with specific diameters for applications in electronics and sensing20,21.

However, more details about the growth process of crystals and the underlying mechanisms (especially in the case of metal core-shell nanowire synthesis) still need to be discovered in order to better control the crystal composition, size, shape, facet, phase, and surface properties as well as explain notable phenomena during the growth process. While the growth mechanisms of nanoparticles are generally better understood due to their simpler structure22,23,24,25, established methodologies, and extensive research, the complexities inherent in core-shell nanowire growth-such as their one-dimensional (1D) nature and dependency on surface interactions, as well as surface ligands-present challenges that continue to require detailed investigation25,26, even though some of the recent reports revealed the helical nanowire morphology depending on chiral organic ligands27,28.

The explorations of the growth of colloidal nanocrystals often rely on cutting-edge nanoscale and real-time imaging tools. In-situ liquid-phase transmission electron microscopy (LPTEM) is among the tool, which offers opportunities for visualizing the material growth in liquids with an atomic-level resolution by tracking on a particle-by-particle basis29,30,31,32,33,34. However, a challenge when utilizing LPTEM is the potential for the electron beam to disrupt solvent conditions and beam-vulnerable materials, which may cause imaging distortion and hinder the discovery of details of colloidal nanocrystal growth35,36,37,38,39. For example, it is reported that a Boerdijk-Coxeter-Bernal (BCB) type nanowire is beam sensitive to be destroyed during atomic resolution imaging40,41.

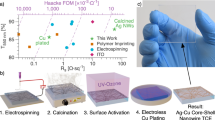

In this study, we employ low-dose LPTEM imaging to investigate the shaping process of core-shell nanowire crystals during seed-induced growth, without the addition of any organic ligands in solution. Notably, the seed nanowires undergo multiple centrifugation and washing steps, which likely reduce the number of ligands on their surfaces. Additionally, no extra ligands or organic solvents are introduced during the reaction process. Through single-particle tracking and cryo-TEM imaging, we identify three key steps in the spatiotemporal fluctuations of the core-shell metal nanowire morphology as the crystal grows: (1) Initially, outer metal atoms deposit on seed nanowires via heterogeneous nucleation due to its lower energy requirement, facilitating rapid deposition and forming the stage I of core-shell nanowire growth. (2) As concentration changes in solution, self-nucleation leads to nanoparticle formation, with many attaching to seed nanowires to reduce total surface energy, marking the stage II. (3) The attached nanoparticles coalescence with the nanowire in the stage III: coalescence depends on the deposited metal’s surface energy and lattice structure. Metals like Au, Ag, and Cu with low surface energy fuse more easily, resulting in smoother core-shell nanowires, whereas Pt and Pd show more surface knots. Interestingly, coalescence normally occurs along the 〈111〉 direction due to its lowest surface energy, making it the preferred fusion direction. This study enriches traditional crystal growth theory and provides a foundation for designing diverse nanomaterials. In solutions without extra organic ligands in colloids, the deposition mechanism of outer metal layers is similar regardless of using chiral or non-chiral seed nanowires, indicating that the crystal structure of seed nanowires has minimal impact on outer metal deposition. This mechanism differs from traditional nanoparticle two-step growth mechanism.

Additionally, our workflow has potential applications in a variety of phenomena governed by nanoscale imaging, including substrate-guided crystal growth, dendrite formation in battery, catalyst morphology revolution, fusion of lipid vehicles, and cellular compartmentalization.

Results

Observation of Pd deposition on AuAg alloy chiral seed nanowire via LPTEM imaging

First, we monitored the coating process of Pd on chiral AuAg nanowires (see Fig. S1 for initial morphology) using LPTEM (see Methods for operation details). It is noted that this chiral nanowire is also named as a BCB nanowire based on previous reports18,42,43 as shown in Fig. 1A, which is identified by both HRSTEM image and the corresponding FFT image. There is no organic ligand present as shown in X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra (Fig. S2) in the solution since we try to study the metal deposition on clean nanowire surface. Before this, we examined the stability of the chiral AuAg seed nanowires in LPTEM and found that they exhibited high structural stability in a liquid environment under the electron beam without any noticeable erosion (Fig. S3 and Movie S1). The liquid likely contributes to maintaining the integrity of the AuAg nanowires by absorbing some of the energy from the electron beam and reducing the chance of structural damage or erosion44.

A HRSTEM image of the chiral AuAg nanowire which showing typical Boerdijk-Coxeter-Bernal Structure as reported41. The inserted image shows the corresponding FFT obtained along the axis of the nanowire in the right to identify Boerdijk-Coxeter-Bernal lattice. B Snapshot image depicts the dynamic process of Pd deposition on a chiral AuAg nanowire: atomic-scale observations reveal an increase in nanowire diameter and the emergence of distinct lattice patterns in Pd〈111〉 direction with time (Red arrow shows the outline of the chiral seed nanowire, and the position of Pd deposition). The electron dose rate was 8.4 e·Å−2·s−1. C Snapshot image depicts the dynamic process of Pd nanoparticle deposition directly on a AuAg nanowire in colloids: the green circle highlights some attached Pd nanoparticles on AuAg seed nanowire followed by covalence whose positions are labelled by red arrows. The electron dose rate was 7.5 e·Å−2·s−1. D The STEM images show the formation of a double-helical nanowire after Pd deposition on the chiral seed nanowire. The surface of the resulting nanowire reveals the outlines of Pd nanoparticles, as indicated by the red arrows. E Schematics show the noble metal deposition hypothesis by using a chiral AuAg alloy nanowire as seed. The heterogeneous nucleation, homogeneous nucleation, nanoparticle attachment, Ostwald ripening, and nanoparticle coalescence lead to a competitive growth mode giving double helical core-shell nanowires.

Next, LPTEM was used to observe the deposition behavior of Pd on the surface of AuAg seed nanowires. This was achieved by adding chloropalladic acid and ascorbic acid as a reducing agent to the dispersion of the seed nanowires in deionized water. Figures 1B and S4 display sequential images describing the coating trajectory of Pd on the chiral AuAg nanowires (see Movie S2 for details) in at the atomic resolution, which demonstrates that Pd atomic layer deposition led to an increase in the diameter of chiral AuAg seed nanowires from 2 nm to 3.3 nm and the emergence of distinct lattice patterns in 〈111〉 direction which is highlighted in yellow dashed line. Time-dependent changes in area, obtained through deep learning-based image processing (see Methods and Fig. S5 for operation details), further illustrate that the diameter of chiral AuAg nanowires gradually increases during the Pd deposition process (Fig. S6).

These results suggest that during the initial stage (0–6.5 s) of Pd coating on chiral AuAg nanowires, foreign Pd atoms act as nucleation sites and trigger the growth of a new Pd layer on the surface of the chiral AuAg nanowires (such a process called heterogeneous nucleation45,46,47), following heterogeneous nucleation mode due to its lower energy barrier. This process aligns with the nucleation and growth mechanisms described in classical crystal growth theory which has been applied to explain metal nanoparticles growth48,49. It is named as stage I of the core-shell metal nanowire growth in this work.

In addition, we observed the attachment of Pd nanoparticles on chiral AuAg seed nanowires within the same solution in the following imaging section. Due to the impact of metal deposition on the atomic-scale in-situ imaging, the attachment process of the nanoparticles could not be directly observed. Therefore, we decided to capture images at a lower magnification to better visualize the overall process. As shown in Fig. 1C (Fig. S7 and Movie S3), distinct particle-like structures (marked in green) can be clearly seen on the surface of the AuAg nanowires. It is evident that Pd nanoparticles rapidly attach to the nanowire surface within seconds, with four distinct Pd nanoparticles adhering to the nanowire within 34 s. This serves as the most direct evidence of nanoparticle attachment on the nanowire surface. Additionally, the growth of other Pd nanoparticles can be observed in the solution. All the observed Pd nanoparticles are very similar in shape and size due to their formation of homogeneous nucleation. Finally, the Pd deposition results in the formation of a double-helical core-shell nanowire as shown in Fig. 1D.

The above observations suggest that the growth mechanism of the nanowires involves multiple processes, which is different from a two-step mode in classical theory of metal nanoparticle growth7. Hence, the following hypothesis is provided in this work as shown in Fig. 1E: (1) Initially, outer metal atoms preferentially deposit onto the surface of seed nanowires through heterogeneous nucleation, which requires lower energy. This process enables rapid deposition and represents the first stage of core-shell nanowire growth (stage I). (2) As the concentration of reactive species changes, self-nucleation occurs, leading to the formation of nanoparticles. A substantial portion of these nanoparticles adhere to the seed nanowires in order to minimize the overall surface energy, marking the second stage of growth (stage II). (3) In the third stage, the attached nanoparticles fuse with the nanowires, completing the growth process while Ostwald ripening also affects the final morphology of the core-shell nanowire (stage III). Notably, for chiral seed nanowires such as those with a BCB structure, the deposition of noble metals results in the formation of a double-helical structure (Figs. 1D, S8, and 9). The double-helical morphology and its formation mechanism observed in this study have been previously reported: this phenomenon is attributed to the deposition of the second layer on the seed nanowire leads to the increase of the internal strain of the nanowire, likely possessing the twisted lattice structure characteristic of the BCB type50.

It is evident that several key issues must be addressed to validate the proposed hypothesis. These questions include: (1) whether the experimental phenomena observed during LPTEM are influenced by experimental conditions, such as the electron beam or solution volume; (2) whether the proposed hypothesis is universally applicable to all deposited metals or is specific to Pd as a unique case; (3) whether the hypothesis applies exclusively to chiral metal nanowires as seed templates; and (4) whether other experimental parameters have been adequately considered, such as the effect of reducing agent strength on deposition kinetics or potential differences in the deposition behavior of transition metals. The following study aims to address these issues in detail to support the proposed hypothesis.

Observation of the intermediates during metal deposition on chiral seed nanowires via Cryo-TEM imaging

To address the first question regarding the influence of experimental conditions, such as the electron beam and solution volume, cryo-TEM was employed to capture intermediates during nanowire growth directly from the original solution. This approach eliminates the potential artifacts caused by electron beam irradiation, small solution volumes, or material decomposition, allowing for the most accurate preservation and visualization of the native morphological features of the intermediate products. Additionally, with further Pd deposition on chiral AuAg nanowires, the occurrence of heavy Pd homogeneous nucleation induced by electron beam, ripening, and the substantial production of gas bubbles significantly hindered the LPTEM imaging (Movie S4), which is a common challenge in the in-situ TEM imaging study. By freezing and imaging samples at various growth times, the intermediates can be obtained. Consequently, we adopted a cryo-TEM to study the later stages of Pd deposition on chiral AuAg seed nanowires. This approach not only eliminated electron beam interference, streamlining the experimental process, but also enabled the quantitative analysis of the resulting nanowire core-shell structures. Although intermediates can be extracted and studied at different time points in non-cryo-preserved samples, this approach raises concerns about whether post-treatment processes may alter their morphology. Such potential alterations could compromise the reliability of subsequent quantitative analyses, making it challenging to accurately uncover the underlying growth mechanisms. Specifically, we applied a rapid cooling process using liquid nitrogen (Fig. S10) to quench the reactions at various time points to collect intermediates for TEM observation. The intermediates obtained after 1 min of Pd deposition reaction exhibit a double helical structure with spots on nanowire surface (Figs. 2A, S10, and S11), whose twisting is due to the strain relaxation of lattice transformation16,50. Between 1 and 5 min of the reaction, Pd-coated nanowires exhibit the presence of nanoparticles on their surfaces, indicating a nanoparticle attachment process during this stage II (Figs. 2B, C, S12, and 13). High-resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy (HRSTEM) images show that the seed nanowires are individually enveloped by a layer of Pd (Fig. 2D) in the final product. Particularly, the morphology of the intermediate after 5 min, as shown in Fig. 2E, is clearly revealed by cryo-EM images. These images demonstrate numerous small nanoparticles attaching to the double-helical nanowires, which at this stage have already formed a double-helical structure. This observation is consistent with the results obtained from LPTEM, effectively ruling out potential influences from the experimental environment. To further investigate the growth kinetics, the intermediate after 1 min was also characterized using cryo-EM. As shown in Fig. 2F–H, not only can the deposition of Pd nanoparticles be clearly observed, but the deposition of Pd atomic layers is also evident (Fig. 2F). This phenomenon further confirms that the growth process of core-shell nanowires involves both heterogeneous nucleation in the form of Pd atomic layer deposition (indicated by red arrows in the figures) and the attachment of Pd nanoparticles (indicated by yellow arrows in the figures). HRSTEM images reveal that the coalescence of Pd nanoparticles occurs along the 〈111〉 direction (Fig. 2G), while EDX maps confirm the presence of deposited Pd layers (Fig. 2H).

A TEM images of Pd deposition on chiral AuAg nanowires at the initial stage of nucleation (Stage I). B Pd nanoparticle attachment (Stage II). C The condensation (Stage III). D HRSTEM image of the Pd coated AuAg nanowires. E HAADF STEM image of the Pd coated chiral AuAg nanowires indicating Pd nanoparticles (yellow arrow) attachment after 5 min growing via cryo-STEM imaging. F, G STEM image of the Pd coated chiral AuAg nanowires in atomic resolution showing both Pd atom deposition (red arrow) and Pd nanoparticle coalescence (yellow arrow) in Pd 〈111〉 direction on AuAg seed nanowire captured by cryogenic STEM after 1 min growth in colloid. H EDX maps confirm the Pd element deposition on the seed nanowire correspondingly as in this figure (F). I Liquid-phase TEM images of Au deposition on chiral AuAg nanowires at the initial stage of nucleation (Stage I). J Au nanoparticle attachment (Stage II) with the red arrow highlighted Au nanoparticle attachment. K The condensation (Stage III) with the red arrow highlighted Au nanoparticle coalescence. L HRSTEM image of the Au coated AuAg nanowires after 10 min growing via cryo-STEM imaging showing nanoparticle coalescence in Au 〈111〉 direction.

As a comparative experiment, the intermediates during the deposition of Au on chiral AuAg seed nanowires were also investigated via cryo-EM imaging. While the Au deposition process also exhibited similar nanoparticle attachment behavior highlighted in red color arrows and dashed lines (Fig. 2I–K), there are two notable differences compared to Pd deposition. First, the number of attached Au nanoparticles is significantly decreased compared to Pd deposition case. Second, the surface of the resulting core-shell nanowires is much smoother. Meanwhile, atomic-scale imaging reveals that the coalescence of Au nanoparticles also occurs along the 〈111〉 direction as shown in Fig. 2L (Figs. S14 and 15), similar to the phenomenon observed during Pd deposition. The Au deposition control experiment also addresses the second question raised earlier, demonstrating that the proposed mechanism is not limited to Pd deposition.

To verify whether the experimental phenomenon is unique, Pt deposition experiments were also conducted. The results (Figs. S16–S18) revealed that the double-helical nanowires formed after Pt deposition exhibited a rough surface with numerous knots, similar to the observations in the Pd deposition experiments. This indicates that the deposition processes follow a similar pattern, with partially fused nanoparticles also observed on the surfaces of the nanowires in both cases.

Nanoparticle coalescence with chiral seed nanowire revealed by atomic electron tomography

A key question arises regarding our hypothesis: is there an interfacial fusion between the core-shell nanowires and the metal nanoparticles? Does nanoparticle attachment truly occur, or is it just an artifact caused by the surface atom deposition observed in 2D imaging? Although atomic-scale STEM images clearly reveal the coalescence of Pd nanoparticles with the seed nanowire along the 〈111〉 direction as shown in Fig. S19, could this observation potentially be a limitation of the 2D imaging perspective?

To address this, we conducted 3D atomic-resolution reconstruction analysis (Figs. S20 and 21) via Usi-Net deep learning40,51 (Fig. S22) toward the Pd (or Au) coated chiral AuAg nanowires to provide a thorough understanding of surface microstructures (Figs. 3A–D, S23–26, and Movies S5 and S6). These figures clearly reveal the presence of nanoparticles adhering to the nanowire surfaces (highlighted within red circles in Fig. 3A, C, and D). These details are challenging to discern in 2D TEM images due to the obstructive nature of nanoparticles. Clearly, interfacial fusion between the nanoparticles and nanowires was observed along the Pd 〈111〉 direction (Fig. 3D). This finding provides a definitive answer to the question posed above. Notably, by comparing HRSTEM images of the same location captured at different time points during imaging, it can be confirmed that the electron beam did not cause any structural damage to the sample (Figs. S21 and S25). This ensures the reliability of atomic-scale 3D reconstruction experiments and the accuracy of the analytical results. It is notably that the missing wadge effect could lead to some errors in the 3D reconstruction which could be corrected via some published method even though the r-factor (Fig. S27) showing the accuracy of the 3D tmography51.

A HRSTEM image of Pd coated chiral AuAg nanowires, showing the core-shell morphology as well as the attached nanoparticle blocked inside the double helical (red box). B, C 3D atomic resolution electron tomography of Pd coated chiral AuAg nanowires, showing in different orientation. The tilting angle range of electron tomography: [−62˚, 64˚]. The attached Pd nanoparticle as well as the phase merge in 〈111〉 direction is highlighted (the red box). D Crop image of 3D atomic resolution reconstructed Pd coated chiral AuAg nanowires, showing its attached orientation in Pd 〈111〉 direction highlighted in yellow dash line. E 3D atomic resolution electron tomography of Au coated chiral AuAg nanowires, showing a smooth surface. The tilting angle range of electron tomography: [−63˚, 67˚]. F HRSTEM image of Fe coated chiral AuAg nanowires, showing the core-shell morphology as well as the attached nanoparticle coalescence in Fe(110) direction. The inserted image is the whole double-helical nanowire with scale bar: 5 nm. G HRSTEM image of Ni coated chiral AuAg nanowires, showing the core-shell morphology in atomic resolution. The inserted image is the whole double-helical nanowire with scale bar: 50 nm. H HRSTEM image of Cu coated chiral AuAg nanowires, showing the core-shell morphology in atomic resolution. The inserted image is the whole double-helical nanowire with scale bar: 20 nm. I HRSTEM image of Ag coated chiral AuAg nanowires, showing the core-shell morphology as well as the attached nanoparticle coalescence in Ag 〈111〉 direction.

A direct comparison between Pd coated chiral AuAg nanowires and Au coated chiral AuAg nanowires demonstrates that the latter exhibits smoother surfaces (Fig. 3D, E). Unexpectedly, we observed interface coalescence between nanoparticles and nanowires at the atomic scale. This interfacial coalescence phenomenon can explain why the final nanowire surface is smoother than the surface of intermediates. By the diameter survey of AuAg@Au, AuAg@Pd, and AuAg@Pt nanowires (Tables S1 and 2), we observed that under identical experimental conditions-namely, the same precursor concentration and a growth time of 30 min the average diameter of AuAg@Au nanowires is 5.3 nm, which is smaller than the average diameters of AuAg@Pd and AuAg@Pt nanowires, which range from 6.3 to 6.4 nm. This result suggests that the coalescence of Au nanoparticles is more uniform, leading to smaller particle sizes compared to the coalescence of Pd and Pt. This difference may be attributed to the fact that Au has a more similar interfacial energy with the AuAg seed nanowire compared to Pd and Pt (Table S3).

The third question regarding the proposed hypothesis concerns the potential of the mechanism. To address this, experiments were designed to deposit different metals onto chiral seed nanowires. As shown in Fig. 3F–I, metals including Fe, Ni, Cu, and Ag were investigated (Figs. S28 and S29). Experimental observations revealed that the deposition of all these metals resulted in the formation of double-helical structures, along with evidence of nanoparticle coalescence. However, the yield of double-helical nanowires varied depending on the specific metal used, decreasing in the order of Cu > Ag > Fe > Ni. Furthermore, EDX mapping confirmed the successful deposition of the outer-layer metals. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 3F, the fusion of Fe nanoparticles with nanowires primarily occurs along the 〈111〉 direction, whereas Ag nanoparticles exhibit fusion along the 〈111〉 direction shown in Fig. 3I. Combining these observations with previous results for Pd, Au, and Ag deposition, a general trend of phase emerges: noble metal nanoparticles tend to fuse along the 〈111〉 direction, while this is not the case for transition metals. This phenomenon may be attributed to the following reasons, first, the {111} surface of noble metals has the lowest surface energy, prompting nanoparticles and nanowires to come into contact and fuse along this plane to minimize the overall free energy of the system52. This energy-driven process makes the 〈111〉 direction the preferred orientation for fusion. Second, differences in surface energy among metals influence their fusion tendencies, with metals exhibiting lower surface energy (e.g., Cu and Ag) more readily diffusing across surfaces and fusing with other metals53. All the above phenomena deviate from traditional studies on nanowire growth mechanisms54,55,56,57,58,59. However, the deposition behavior of Ni cannot be fully explained by these mechanisms. Finally, perhaps an interesting future research direction could involve studying how different types of organic ligands influence the deposition of an outer metal layer on nanowires and the direction of grain boundary fusion.

The observation of metal deposition on non-chiral seed nanowire via nanoscale imaging

The fourth question regarding the proposed hypothesis pertains to whether the crystal structure of the seed nanowires influences nanoparticle attachment during outer-layer metal deposition and whether Ostwald ripening occurs. To address this issue, non-chiral seed nanowires (Fig. S30) were applied to conduct similar metal deposition experiments. The chiral AuAg seed nanowires were synthesized at room temperature, while the non-chiral AuAg seed nanowires were synthesized at 40 °C, with all other experimental conditions kept identical. After synthesis, the nanowires underwent four rounds of washing. XPS analysis confirmed the absence of any organic ligands on the surface of all seed nanowires (Fig. S2).

The experimental procedure and the anticipated metal deposition mechanism are illustrated in Fig. 4A. The process begins with the heterogeneous nucleation and deposition of metal atoms, followed by nanoparticle (NP) attachment, and ultimately NP coalescence. The extent of coalescence varies depending on the type of metal deposited. Figure 4B presents the NP coalescence process during Pd deposition, captured via in-situ LPTEM. Notably, the NP coalescence process is rapid, completing in approximately 40 s (Figs. S31 and S32, and Movie S7), although this duration depends on the type of metal deposited. The HRSTEM images reveal both the deposition of Pt atomic layers and the coalescence of Pt NPs along the 〈111〉 direction as shown in Fig. 4C. These observations are like the deposition behavior of noble metals on chiral nanowires, thereby supporting the universality of the proposed mechanism. The phenomenon of Pt deposition observed in Fig. 4C could potentially be attributed to galvanic replacement between Pt and the AuAg alloy nanowire. However, similar nanoparticle formation was also observed in our experiments involving Ag deposition and other metals, which supports our hypothesis. It is possible that the galvanic replacement between Pt and the AuAg alloy nanowire may explain why the nanoparticles appear larger in the Pt deposition experiment.

A Schematics show the noble metal deposition process by using a chiral AuAg alloy nanowire as seed. The heterogeneous nucleation, homogeneous nucleation, nanoparticle attachment, Ostwald ripening, and nanoparticle coalescence lead to a competitive growth mode giving. B The snapshot image illustrates the LPTEM observation of Pd nanoparticle coalescence with nanowire locally. C Right: TEM image of Pt coated non-chiral AuAg seed nanowire giving a core-shell nanowire with rough surface (this is an intermediate after 5 min growth imaging via cryo-TEM) showing lots of Pt nanoparticles attachment highlighted in red arrow. Left: HRSTEM image showing both Pt atom deposition (red arrow) and Pt nanoparticle coalescence in Pt 〈111〉 direction (yellow arrow). D TEM images showing different types of metal deposition on non-chiral AuAg seed non-chiral nanowire giving a core-shell nanowire with nanoparticles attachment which includes Pd, Au, Ni, Cu, and Ru. The red arrows show the position of the nanoparticle coalescence which region is highlighted in red color on nanowire (these are intermediates after 5 min growth imaging via cryo-TEM).

The universality is not limited by the crystalline structure of the seed nanowires or the type of deposited metal. As shown in Fig. 4D, deposition experiments involving Pd, Au, Ni, Cu, and Ru (Figs. S33–38) further confirm this mechanism. In the absence of any organic ligands, metal deposition on AuAg seed nanowires consistently exhibits both NP attachment following self-nucleation and atomic layer deposition driven by heterogeneous nucleation. These conclusions are supported by the observed increase in the diameter of the resulting core-shell nanowires and the formation of surface knot-like structures. Importantly, these phenomena closely resemble the deposition behavior observed on chiral nanowires, further supporting the proposed mechanism.

The morphology of the resulting core-shell nanowires reveals that, after Au deposition, the surface is the smoothest, although some NP contours can still be detected (Fig. S40). In contrast, after the deposition of Pd or Pt, the surface of the core-shell nanowires becomes very rough, with distinct and abundant NP contours visible (Figs. S41 and S42). This roughness is primarily due to the greater interfacial energy that needs to be overcome for fusion, making the process more challenging. These observations are highly consistent with findings from the double-helical synthesis experiments.

Following the 3D reconstruction of the core-shell nanowires in nanoscale (Movie S8), we performed surface curvature analysis (Fig. S43). The analysis shows that the surface of the gold-deposited nanowires is smoother compared to that of the palladium-deposited nanowires, which remains rough despite phase coalescence. This discrepancy may arise from differences in lattice matching between the various metal crystals.

Another issue needed to consider is whether the Mx+ to M reduction reaction affects its deposition dynamics on AuAg seed nanowire without organic ligands. Control experimental results indicate that when a strong reducing agent, such as sodium borohydride (Fig. S44b), is used, Pd homogeneous nucleation dominates. This leads to the formation of many Pd nanoparticles in the solution, with relatively few nanoparticles attaching to the nanowire surface. In contrast, when a weaker reducing agent, such as ascorbic acid (Fig. S44a), is used, heterogeneous nucleation becomes dominant, resulting in noticeable nanoparticle coalescence on the nanowire surface. These findings suggest that the redox reaction rate in the solution plays a significant role in determining the mechanism of Pd deposition. Taking into account parameters such as the yield of nanowires and the valence state of reduced metal products, environmental factors in the reaction solution, including pH (Table S4), reactant concentration, reducing agent concentration, and temperature (Table S5), may all influence the yield of core-shell nanowires.

These findings indicate that the growth mechanism of metal core-shell nanowires during colloidal synthesis is a complex competitive process involving three key steps: heterogeneous nucleation, homogeneous nucleation, and nanoparticle attachment & coalescence. Additionally, this process encompasses phase coalescence and Ostwald ripening (Fig. 5A). Figure 5A illustrates the Ostwald ripening observed via LPTEM, which contributes significantly to variations in the nanowire morphology highlighted in red and blue color, surface characteristics, and size highlighted by yellow arrow due to the dissolution and redeposition (Fig. S46 and Movie S9). This ripening process leads to the formation of surface “knots,” representing localized growth and restructuring on the nanowire. However, Oswald ripening was not observed in the transition metal deposition experiments, even after multiple attempts. It seems that the metal type significantly influences Ostwald ripening due to differences in surface energy and atomic mobility. Noble metals (like Au, Ag, and Pd) exhibit pronounced ripening due to higher atomic diffusivity and surface energy compatibility, whereas transition metals (such as Fe, Ni, Cu, and Ru) exhibit limited ripening as a result of lower diffusivity and surface energy mismatch. In comparison, our experiments demonstrate that the coalescence speed of nanoparticles varies depending on the metal type. For instance, Pd, Au, and Pt nanoparticles coalesce rapidly because they have similar interfacial energies with AuAg alloy nanowires, while Fe, Ni, Cu, and Ru show delayed deposition-coalescence dynamics. Furthermore, the effects of different reducing agents and temperatures on the experimental outcomes were tested. It was observed that using ascorbic acid, hydrazine hydrate, or sodium borohydride to reduce Ni(NO3)2 all yielded the same type of nanowires without significant differences in the experimental observations (Fig. S38), and the nanoparticle attachment was trapped clearly, which means that our hypothesis works to transition metals too. Notably, ascorbic acid effectively reduces Cu²⁺, Fe²⁺, Ni²⁺, and Ru³⁺ ions to their elemental forms. However, the presence of oxide layers on the surface of the nanowires, as confirmed by XPS characterization (Fig. S45), introduces uncertainty regarding the extent of reduction achieved for these metals. Finally, the pH of the solution was measured during the experiments using different reducing agents, with the pH range spanning from 2.61 to 10.81. While the pH did not significantly affect the morphology of the products, it may influence the final valence states of the metals and their yield, as shown by our experimental results.

A The snapshot image illustrates the LPTEM observation of Ostwald ripening among attached Pd nanoparticles highlighted in red and blue color. The yellow arrow shows the position of the Ostwald ripening which gives a surface with lots of knots as an evidence of nanoparticle attachment. B STEM image of Au coated chiral AuAg nanowires with the dashed line showing the reference region for strain analysis. C STEM image of Au chiral coated AuAg nanowires after denoising. D, E Color map of strain distribution (±2.0%) of Au coated chiral AuAg nanowires. F HRTEM image of Au coated chiral AuAg nanowires, which is the same sample as shown in C. Color maps showing the strain distribution in Ɛyy direction of (G) the pristine BCB AuAg nanowire, and (H) the BCB AuAg nanowire@Au, after one atom layer Au deposition, which are collected from MD simulations.

Local strain analysis of Au@AuAg core-shell double-helical nanowires

Further, we investigated the atomic-scale strain within Au coated chiral AuAg seed nanowires (double-helical nanowires, Fig. S47). Typically, atomic-scale imaging using HRSTEM, followed by geometrical phase analysis (Fig. S48), was used to determine strain distribution on a specific plane. However, this approach is not applicable for our case due to the 3D geometry of double-helical nanowire. Here, we used MATLAB code to analyze the strain within Au coated AuAg nanowires60. Figure 5B, C outlines the reference region of data processing and that after denoising. Figures 5D, E and S49 present color maps of strain for a uniform region of the double-helical nanowire respectively, showing that the strain distribution in this double-helical nanowire exhibits regional specificity even though the whole double-helical nanowire looks uniform in geometry under HRTEM (Fig. 5F): higher strain is observed in the central and boundary regions of the nanowire, while the middle region displays lower strain with relatively uniform distribution. Higher strain in the central region is likely induced by the deposition of external Au atoms, while higher strain at the boundary may result from structural features at the boundary. Although ultrathin metallic double-helical nanowires were synthesized decades ago50, there has been no effective method to investigate the influence of internal strain on their structure. In this study, we employed a coding technique to analyze the internal strain within ultrathin double-helical nanowires. This strain arises from the packing of interpenetrated icosahedral or decahedral units in the BCB seed nanowires (Fig. S47). The molecular dynamic simulation results (Fig. 5G, H and Tables S6 and 7) show that the stress within the nanowire increases as gold atoms are deposited on the outer layer. Specifically, depositing one layer of gold atoms causes the number of high-stress region atoms within the nanowire to increase by approximately 30% (Fig. S50) due to the simulation result. This observation aligns with the experimental findings of stress within the nanowire and is consistent with previous literature61. Understanding this strain contributes to a deeper comprehension of their helical formation mechanism and provides insights into controlling the chirality and yield of double-helical nanowires.

In summary, this study investigates the deposition dynamics of various metals on seed nanowires with different crystalline structures, including both chiral and non-chiral seed nanowires, in a ligand-free solution. Our findings reveal that the growth mechanism of core-shell nanowires can be divided into three distinct stages: (1) an initial stage dominated by heterogeneous nucleation and atomic deposition, which occurs rapidly within a few seconds; (2) a short-lived intermediate stage primarily driven by NP attachment, lasting several tens of seconds; and (3) a final stage involving NP coalescence. This process is accompanied by Ostwald ripening, which occurs within the first five minutes and can extend up to 30 min depending on factors such as interfacial energy between the metals. The crystalline structure of the seed nanowire has minimal influence on this growth mechanism. However, several factors significantly impact the final morphology of the core-shell nanowires, including the type and reactivity of the deposited metal, as well as the interfacial energy between the metals. For AuAg alloy seed nanowires, noble metals such as Au, Ag, Pt, and Pd exhibit a tendency to coalesce preferentially along the 〈111〉 crystal direction. Additionally, the rate of redox reactions in the system plays a critical role in determining the competition between self-nucleation and heterogeneous nucleation62. Specifically, the use of strong reducing agents promotes the deposition of metal layers via NP attachment to the seed nanowires. Our work demonstrates a combination and competitive growth mechanism of metal core-shell nanowires derived from advanced TEM imaging that can improve noble metal nanocrystals design and applications63,64,65,66,67.

Methods

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Synthesis of AuAg nanowires

Chiral AuAg nanowires were synthesized in a colloidal system50. Typically, the process involved incubating HAuCl4, AgNO3 (mole ratio 1:1), ascorbic acid, and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, 40 mM) in a DMF/H2O mixture (volume ratio 8:1) for 6 days at room temperature. Subsequently, the solution was left at room temperature for 6 days without agitation. Concurrently, the non-chiral AuAg nanowires were obtained when the solution was incubated at 40 °C. The AuAg nanowires were isolated by centrifugation at 7895 × g for 8 min. Subsequently, the nanowires underwent three rounds of water washing to remove excess PVP. Further impurities were eliminated by using a 15 mL plastic centrifuge tube and an additional 5 mL of water. For future use of the purified AuAg nanowires, they could be re-dispersed in 1 mL H2O without any aggregation.

A metal shell deposition on AuAg nanowires in the colloidal system (such as Au, Pd, Pt, Ag, Fe, Ni, Cu, Ru)

In a commonly performed Au coating experiment, 50 µL of the as-purified AuAg nanowires aqueous solution was introduced into 200 µL of aqueous L-ascorbic acid solution (concentration: 0.2 M) under vortex. Subsequently, 60 µL of HAuCl4 solution (volume ratio: H2O/DMF = 1:1) was added. The final mixture was allowed to sit undisturbed at room temperature for 30 min to complete the Au deposition. For the purification of the core-shell nanowire, it underwent centrifugation using a 15 mL plastic centrifuge tube at 3708 × g for 8 min. Following this, it was subjected to three rounds of water washing and an additional three rounds of ethanol washing to eliminate residues and surface ligands. Ultimately, the purified solution was re-dispersed in water for future use. Note: the sample size of double-helical nanowire was defined by sample survey after 9 trials of the above synthesis, whose survey was listed in Tables S1 and 2 in supplementary information. Different types of reducing agent were applied in the transition metal deposition experiments whose control experiments were shown in Tables S4 and 5.

Reducing agent test experiments in Pd deposition on AuAg nanowire in the colloidal system

In a commonly performed Pd coating experiment, 50 µL of the as-purified AuAg nanowires aqueous solution was introduced into 200 µL of aqueous sodium borohydride (concentration: 0.2 M) under vortex. All other parameters are the same as the above section.

Basic characterizations

Nanoscale resolution TEM images, TEM 3D tomography, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), and high-resolution TEM images were obtained through characterizations performed on an ultrathin carbon film-supported TEM grid (TED PELLA, INC). The atomic resolution STEM electron tomography characterizations were conducted using an FEI Titan 60-300 microscope, operating at an acceleration voltage of 200 kV, at the National Center for Electron Microscopy at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Table S3).

ADF-STEM data acquisition

Multiple tomographic tilt series were acquired with the TEAM 0.5 microscope and TEAM stage, located at the National Center for Electron Microscopy within the Molecular Foundry. Images for various samples were captured under different imaging conditions, including variations in voltage, screen current, and tilting range, as detailed in the supplementary information.

Fabrication of the graphene liquid cell

Creating a graphene liquid cell for in situ TEM involves many steps to fabricate the graphene acts as a stable enclosure for the liquid sample. Below outlines the fabrication process followed a reported method with some modification68: (1) Making Graphene-Coated TEM Grids: Using 5-layer graphene enhances the success rate of encapsulating liquid pockets in TEM grids without compromising resolution, as graphene, being atomically thin and low-Z, minimizes resolution loss primarily from liquid thickness. After cleaning with acetone to remove deposition residues, smoothing out the graphene-on-copper piece ensures proper bonding with TEM grids by eliminating macroscopic wrinkles. Subsequent copper etching using sodium persulfate exposes the graphene-coated grids, readying them for liquid cell fabrication. (2) Fabricating Liquid Cell Pockets: Begin by placing two graphene-coated TEM grids, graphene side up, onto a glass slide. Using a surgical scalpel blade, carefully trim approximately 1/4 of the edge from one grid. Next, prepare the liquid sample by depositing ~0.3 µL mixed solution (as shown in metal shell deposition section) onto the intact grid using tweezers to stabilize it against capillary forces. Immediately position the grid with the trimmed corner atop the droplet, ensuring the second grid rests on the first without expelling any liquid. Allow 10 min for graphene liquid cell pockets to form, acknowledging potential evaporation during this period, which stabilizes once a hermetic seal is achieved. The rate of the succussed liquid cell self-assembly is 3/5 followed the above protocol.

In-situ LPTEM data acquisition

We adapted a modified procedure based on a previously published method to transfer graphene onto the underlying TEM grids69,70. Initially, a single TEM grid coated with graphene was positioned on a glass slide with the graphene side facing upwards. A small droplet (0.4–0.5 µL) of the mixture solution was then carefully deposited at the grid’s center. Subsequently, another TEM grid coated with graphene was placed on top, effectively covering the droplet and the underlying TEM grid. Over the course of 10 min, as water evaporated from the environment, the top and bottom TEM grids were gently brought together, sealing the remaining solution. For data analysis of the movies, we employed deep learning using the Dragonfly software.

Cryo-TEM sample preparation and imaging

In our procedure, we typically utilized a TEM grid with a carbon film to capture the intermediates. We employed tweezers to hold the TEM grid and swiftly immersed it in the growth solution, promptly removing it with attached samples. Following this, the TEM grid with the plated intermediates was inserted into a Teflon-sealed Eppendorf tube. It was then rapidly submerged in a bath of liquid nitrogen (LN2) to swiftly quench the reaction. Subsequently, the TEM grid was meticulously secured onto a TEM cryo-holder (Gatan) using a cryo-transfer station, ensuring that the entire process took place within the LN2 environment. During our experiments, TEM imaging was conducted under cryogenic conditions at −74 °C.

3D reconstruction and segmentation

The 3D reconstruction and segmentation were carried out utilizing various coding methods and software, including Tomviz, and Avizo 9.0/Amira 6.4. Additional details can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Image processing via deep learning

HRSTEM image processing has witnessed significant advancements through the application of deep learning techniques in this work. The image processing contains various critical tasks such as denoising, drifting correction, plane wave alignment, and more, to enhance the quality and fidelity of HRSTEM images. Deep learning algorithms, including convolutional neural networks have demonstrated high efficacy in automatically removing noise artifacts, correcting drift-induced distortions, and aligning images to correct for specimen drift and beam instability, which has been applied in this work. More details could be found in supplementary information.

Molecular dynamic simulation (MD simulation)

The simulation utilized the open-source LAMMPS software and was conducted at 300 K. Post-processing was carried out using the Ovito software. The force field implemented was eam/alloy71. The system was further simulated for 20 picoseconds under the same ensemble. Finally, the atomic virial stress was calculated using the following formula (1):

In the formula, the first term represents contributions from the pair potential, where denotes the number of nearest neighbor particles, and are the coordinates of the two particles involved in the pair potential, and represent the forces acting on each of these two particles. The second term corresponds to forces arising from bond energy, which typically accounts for bond stretching and compression effects. The remaining terms include contributions from bond angles, dihedral angles, and improper interactions, all of which collectively describe the various potential energy terms in the force field. The K Space term accounts for long-range Coulomb interactions, specifically the forces arising from electrostatic interactions between charges in the system, typically computed using a method such as the Particle-Particle Particle-Mesh technique for efficiency and accuracy (Tables S6 and 7).

\({N}_{p}\) the number of nearest neighbor particles, \({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{1}\) represents the coordinates of two atoms involved in the pair potential, \({{{{\boldsymbol{F}}}}}_{1}\) and \({{{{\boldsymbol{F}}}}}_{2}\) represents the forces acting on these two atoms; (\({N}_{b}\)) forces arising from bond energy, (\({N}_{a}\)) bond angles, (\({N}_{d}\)) dihedral angles, (\({N}_{i}\)) improper interactions; KSpace represents the forces arising from long-range Coulomb interactions.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this article, and other findings of this study, are available in supplementary information, or from the corresponding author (Prof. Xiaohui Song: xiaohuisong@hfut.edu.cn) upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code applied in the strain analysis of the AuAg@Au double-helical nanowire is available from the corresponding author (Prof. Xiaohui Song: xiaohuisong@hfut.edu.cn) upon reasonable request.

References

Liao, H.-G., Cui, L., Whitelam, S. & Zheng, H. Real-time imaging of Pt3Fe nanorod growth in solution. Science 336, 1011–1014 (2012).

Liao, H.-G. et al. Facet development during platinum nanocube growth. Science 345, 916–919 (2014).

Luo, B. et al. Unravelling crystal growth of nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 589–595 (2023).

Yuk, J. M. et al. High-resolution EM of colloidal nanocrystal growth using graphene liquid cells. Science 336, 61–64 (2012).

Zhu, G. et al. Self-similar mesocrystals form via interface-driven nucleation and assembly. Nature 590, 416–422 (2021).

Yin, Y. & Alivisatos, A. P. Colloidal nanocrystal synthesis and the organic-inorganic interface. Nature 437, 664–670 (2005).

Zheng, H. et al. Observation of single colloidal platinum nanocrystal growth trajectories. Science 324, 1309–1312 (2009).

Li, D. et al. Direction-specific interactions control crystal growth by oriented attachment. Science 336, 1014–1018 (2012).

De Yoreo, J. J. et al. Crystallization by particle attachment in synthetic, biogenic, and geologic environments. Science 349, 6760 (2015).

Lee, J., Yang, J., Kwon, S. G. & Hyeon, T. Nonclassical nucleation and growth of inorganic nanoparticles. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16034 (2016).

Xia, Y. et al. One-dimensional nanostructures: synthesis, characterization, and applications. Adv. Mater. 15, 353–389 (2003).

Wang, J. et al. Near-ideal theoretical strength in gold nanowires containing angstrom scale twins. Nat. Commun. 4, 1742 (2013).

Huang, Q., Qin, D. & Xia, Y. Seeing is believing: what is on the surface of silver nanocrystals suspended in their original reaction solution. Chem. Sci. 15, 6321–6330 (2024).

Fan, Z. & Zhang, H. Template synthesis of noble metal nanocrystals with unusual crystal structures and their catalytic applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 2841–2850 (2016).

Wang, C., He, J. & Xia, Y. Controlling the composition and elemental distribution of bi-and multi-metallic nanocrystals via dropwise addition. Nat. Synth. 3, 1076–1082 (2024).

Lu, Y. et al. Braiding ultrathin Au nanowires into ropes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 10629–10633 (2020).

Mokashi-Punekar, S., Zhou, Y., Brooks, S. C. & Rosi, N. L. Construction of chiral, helical nanoparticle superstructures: progress and prospects. Adv. Mater. 32, 1905975 (2020).

Jin, H. et al. Modulating the alloying mode in the doping-induced synthesis of Au-Pd nanowires. Nano Res. 17, 3334–3343 (2024).

Du, W. et al. Twisting, untwisting, and retwisting of elastic Co-based nanohelices. Nat. Commun. 14, 4426 (2023).

Gong, S., Lu, Y., Yin, J., Levin, A. & Cheng, W. Materials-driven soft wearable bioelectronics for connected healthcare. Chem. Rev. 124, 455–553 (2024).

Ma, W. et al. Chiral inorganic nanostructures. Chem. Rev. 117, 8041–8093 (2017).

Gao, W. et al. Probing the dynamics of nanoparticle formation from a precursor at atomic resolution. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau9590 (2019).

An, Q. et al. Direct growth of single-chiral-angle tungsten disulfide nanotubes using gold nanoparticle catalysts. Nat. Mater. 23, 347–355 (2024).

Du, J. S., Bae, Y. & De Yoreo, J. J. Non-classical crystallization in soft and organic materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 9, 229–248 (2024).

Amiri, A., Yurkiv, V., Phakatkar, A. H., Shokuhfar, T. & Shahbazian-Yassar, R. Insights into formation and growth of colloidal multielement alloy nanoparticles in solution through in situ liquid cell TEM study. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2304685 (2024).

Liu, G. et al. Sub-nanometer Pt nanowires with disordered shells for highly active elelctrocatalytic oxidation of formic acid. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202422199 (2024).

Cheng, C. et al. Helical assemblies of colloidal nanocrystals with long-range order and their fusion into continuous structures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 1803–1812 (2025).

Chen, J. et al. Chiral inorganic nanomaterials characterized by advanced TEM: a qualitative and quantitative study. Adv. Mater. 36, 2410676 (2024).

Ross, F. M. Opportunities and challenges in liquid cell electron microscopy. Science 350, aaa9886 (2015).

De Yoreo, J. J. & Sommerdijk, N. A. J. M. Investigating materials formation with liquid-phase and cryogenic TEM. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16035 (2016).

Clark, N. et al. Tracking single adatoms in liquid in a transmission electron microscope. Nature 609, 942–947 (2022).

Hong, J. et al. Metastable hexagonal close-packed palladium hydride in liquid cell TEM. Nature 603, 631–636 (2022).

Zhou, S. et al. Visualizing interfacial collective reaction behaviour of Li-S batteries. Nature 621, 75–81 (2023).

Yang, R. et al. Fabrication of liquid cell for in-situ transmission electron microscopy of electrochemical processes. Nat. Protoc. 18, 555–578 (2022).

Park, J. et al. Graphene liquid cell electron microscopy: progress, applications, and perspectives. ACS Nano 15, 288–308 (2021).

Ou, Z., Wang, Z., Luo, B., Luijten, E. & Chen, Q. Kinetic pathways of crystallization at the nanoscale. Nat. Mater. 19, 450–455 (2020).

Kashin, A. S. & Ananikov, V. P. Monitoring chemical reactions in liquid media using electron microscopy. Nat. Rev. Chem. 3, 624–637 (2019).

Zeng, Z., Zheng, W. & Zheng, H. Visualization of colloidal nanocrystal formation and electrode-electrolyte interfaces in liquids using TEM. Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 1808–1817 (2017).

De Jonge, N. & Ross, F. M. Electron microscopy of specimens in liquid. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 695–704 (2011).

Song, X. et al. High-resolution electron tomography of ultrathin Boerdijk-Coxeter-Bernal nanowire enabled by superthin metal surface coating. Small 18, 2203310 (2022).

Velázquez-Salazar, J. J. et al. Experimental evidence of icosahedral and decahedral packing in one-dimensional nanostructures. ACS Nano 5, 6272–6278 (2011).

Xiao, Q., Wu, Y., Li, M., O’Keeffe, M. & Li, D. A metal-organic framework with rod secondary building unit based on the Boerdijk-Coxeter helix. Chem. Commun. 52, 11543–11546 (2016).

He, G., Wang, R., Fan, J., Liu, S. & Chen, H. In silico investigation on the twisting of gold nanowires. Mater. Today Commun. 33, 104319 (2022).

Pu, S., Gong, C. & Robertson, A. W. Liquid cell transmission electron microscopy and its applications. R. Soc. Open Sci. 7, 191204 (2020).

Jun, Y.-S., Kim, D. & Neil, C. W. Heterogeneous nucleation and growth of nanoparticles at environmental interfaces. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 1681–1690 (2016).

Espinosa, J. R., Vega, C., Valeriani, C., Frenkel, D. & Sanz, E. Heterogeneous versus homogeneous crystal nucleation of hard spheres. Soft Matter 15, 9625–9631 (2019).

Tan, P., Xu, N. & Xu, L. Visualizing kinetic pathways of homogeneous nucleation in colloidal crystallization. Nat. Phys. 10, 73–79 (2014).

Thanh, N. T., Maclean, N. & Mahiddine, S. Mechanisms of nucleation and growth of nanoparticles in solution. Chem. Rev. 114, 7610–7630 (2014).

Mallette, A. J., Shilpa, K. & Rimer, J. D. The current understanding of mechanistic pathways in zeolite crystallization. Chem. Rev., Chem. Rev. 124, 3416–3493 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Chiral transformation: from single nanowire to double helix. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 20060–20063 (2011).

Yao, L., Lyu, Z., Li, J. & Chen, Q. No ground truth needed: unsupervised sinogram inpainting for nanoparticle electron tomography (UsiNet) to correct missing wedges. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 28 (2024).

Kodrycka, M. & Patkowski, K. Platinum, gold, and silver standards of intermolecular interaction energy calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 151, 070901 (2019).

De Luna, M. M. & Gupta, M. Effects of surface tension and viscosity on gold and silver sputtered onto liquid substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 201605 (2018).

Chen, R., Nguyen, Q. N. & Xia, Y. Oriented attachment: a unique mechanism for the colloidal synthesis of metal nanostructures. ChemNanoMat. 8, e202100474 (2022).

Pathiraja, G., Herr, D. J. & Rathnayake, H. Nanoscopic insight into Sol–Gel chemical kinetics of oriented attachment crystal growth in anisotropic copper hydroxide nanowires. Cryst. Growth Des. 22, 2889–2902 (2022).

Li, S., Jin, H. & Wang, Y. Recent progress on the synthesis of metal alloy nanowires as electrocatalysts. Nanoscale 15, 2488–2515 (2023).

Bu, L. et al. Surface engineering of hierarchical platinum-cobalt nanowires for efficient electrocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 7, 11850 (2016).

Liu, Z. et al. Aqueous synthesis of ultrathin platinum/non-noble metal alloy nanowires for enhanced hydrogen evolution activity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 11678–11682 (2018).

Zhu, S. et al. Tuning structural and compositional effects in Pd-Au nanowires for highly selective and active CO2 electrochemical reduction reaction. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1802238 (2018).

Ozdol, V. et al. Strain mapping at nanometer resolution using advanced nano-beam electron diffraction. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 253107 (2015).

Zhong, Q. et al. Strain-modulated seeded growth of highly branched black Au superparticles for efficient photothermal conversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 20513–20523 (2021).

Yang, D. et al. Unraveling nanosprings: morphology control and mechanical characterization. Mater. Horiz. 11, 3500–3527 (2024).

Li, M. et al. Ultrafine jagged platinum nanowires enable ultrahigh mass activity for the oxygen reduction reaction. Science 354, 1414–1419 (2016).

Zhao, H. et al. Atomic-scale structure dynamics of nanocrystals revealed by in situ and environmental transmission electron microscopy. Adv. Mater. 35, 2206911 (2023).

Yang, R. et al. Intercalation in 2D materials and in situ studies. Nat. Rev. Chem. 8, 410–432 (2024).

Zhang, Q. et al. In situ TEM visualization of LiF nanosheet formation on the cathode-electrolyte interphase (CEI) in liquid-electrolyte lithium-ion batteries. Matter 5, 1235–1250 (2022).

Hu, H., Yang, R. & Zeng, Z. Advances in electrochemical liquid-phase transmission electron microscopy for visualizing rechargeable battery reactions. ACS Nano. 18, 12598–12609 (2024).

Hauwiller, M. R., Ondry, J. C. & Alivisatos, A. P. Using graphene liquid cell transmission electron microscopy to study in situ nanocrystal etching. J. Vis. Exp. 135, 57665 (2018).

Yuk, J. M. et al. Graphene veils and sandwiches. Nano Lett. 11, 3290–3294 (2011).

Chen, Q. et al. 3D motion of DNA-Au nanoconjugates in graphene liquid cell electron microscopy. Nano Lett. 13, 4556–4561 (2013).

Zhou, X., Johnson, R. & Wadley, H. N. Misfit-energy-increasing dislocations in vapor-deposited CoFe/NiFe multilayers. Phys. Rev. B 69, 144113 (2004).

Acknowledgements

Work at Molecular Foundry of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. X.S. was supported by the starting-up funding of Hefei University of Technology under Grant No. 13020-03712021026, Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (PA2024GDGP0042). Y.W. was supported by the Jiangsu Specially Appointed Professors Project (No. 1711510024). We are grateful to Prof. Mary Scott, Miss Alex Bruefach, and Miss Hannah Devyldere from the University of California, Berkeley, Dr. Peter Ercius, and Dr. Karen Bustillo from Molecular Foundry at Lawrence Berkeley National Lab, Dr. Sheng Cheng from Hefei University of Technology for their kind help on the electron tomography experiments and 3D reconstructions. We are grateful to Prof. Hongyu Chen and Miss Qian Wang from Westlake University for the help on graphene liquid cell assembly and relative discussions. We thank the Hefei In-situ Technology. Co., Ltd. for the support on in-situ TEM experiments during the manuscript revision.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.S. conceived the idea and directed the project. X.S., Z.O., D.Y., B.Z. R.H., Y.W., and X.Z. designed all the experiments and synthesis of the nanowire materials. X.S., D.Y., B.Z., C.O., and C.S. designed the electron tomography experiments and the data collection. X.S., R.Y., X.Z., C.S., Z.O., performed the imaging process, X.S., H.X., X.W., X.Z., performed 3D reconstruction for tomography in nanoscale. X.S., D.Y., R.Y., and Z.O. performed the atomic resolution reconstruction and segmentation of nanowire under the help of Prof. Mary Scott from Molecular Foundry at Berkeley National Lab. X.S. and C.S. conducted the Cryo TEM characterizations. X.S., M.L., X.Z., Z.O., S.C., and R.Y. designed and worked on in situ liquid phase TEM experiments. X.S., D.Y., R.Y., X.Z., Z.O., and J.K. did the movie analysis via deep learning. M.L., B.Z., X.W., H.X., and H.X. analyzed the EDX data, HRSTEM data and prepare the samples for other characterizations. X.S., C.O., and X.Z. did the strain analysis of double helical nanowire by using MATLAB. All in-situ liquid phase TEM experiments and data collections are conducted at Hefei University of Technology, Molecular Foundry (Lawrence Berkeley National Lab) and University of California, Berkeley. MD simulation was performed by X.S., and X.Z. The manuscript preparation is completed at Hefei University of Technology. All authors commented on the manuscript and contributed to the discussion of the results, the preparation, and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, D., Zhang, X., Yang, R. et al. Observation of nanoparticle coalescence during core-shell metallic nanowire growth in colloids via nanoscale imaging. Nat Commun 16, 4795 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60135-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60135-3