Abstract

Understanding the ultrafast transport properties of charge carriers in transition metal dichalcogenides is essential for advancing technologies based on these materials. Here, we study MoSe2 crystals with thicknesses down to the monolayer, combining ultrafast spatiotemporal microscopy and quantitative microscopic modelling. Crucially, we obtain the intrinsic ultrafast transport dynamics by studying suspended crystals that do not suffer from detrimental substrate effects. In mono- and bilayer crystals, we identify four sequential transport regimes. The first two regimes involve high-energy non-thermalized and quasi-thermalized carriers that propagate rapidly with diffusivities up to 1000 cm2/s. After ~1.5 ps, a remarkable third regime occurs with apparent negative diffusion, finally followed by exciton propagation limited by trapping into defect states. Interestingly, for trilayer and thicker crystals, only the first and last regimes occur. This work underscores the role of traps and dielectric environment in electron transport, offering valuable insights for the development of (flexible) (opto)electronic applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

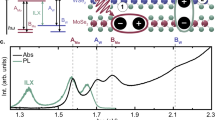

Transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) are layered semiconductors that exhibit particularly interesting optoelectronic properties, including large exciton binding energies (0.3–0.7 eV)1 for the A and B excitons2, strong light-matter interaction3,4, optical nonlinearities5,6,7, and the possibility to selectively populate different pseudo-spin valleys8,9. Some properties drastically change when reducing their thickness, most notably their bandgap, which is indirect for all thicknesses except for the monolayer case10,11. Overall, TMDCs provide an exceptionally rich playground with interactions between quasi-free carriers, bright and dark excitons, trions, phonons, and trap states, among others. It is the interplay between these species that will eventually determine the (opto)electronic performance of devices based on TMDCs. This interplay is further affected by key parameters, such as the energy and intensity of optical excitation, or the considered timescales. In addition, the large surface area of few-layer TMDCs makes them remarkably sensitive to their dielectric environment12,13,14,15. It is therefore important—from both an applied and a fundamental perspective—to understand the spatiotemporal dynamics of TMDCs in different dielectric environments and at sufficiently short timescales.

The ultrafast transport properties of solid-state materials are often studied using spatiotemporal microscopy. This powerful technique tracks how a population of excited species spreads over time, and enables the measurement of its diffusion coefficient16. This technique has been widely employed to study TMDCs17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, and the reported diffusivities vary over many orders of magnitude. Focusing on room-temperature experiments, a few recent studies claimed very fast initial diffusion, including a diffusivity of 980 cm2/s for 10 nm thick WS221, 502 cm2/s for monolayer WSe2 and 2295 cm2/s for monolayer MoSe220, attributed to the propagation of hot quasi-free carriers. Other studies claimed somewhat lower initial diffusivities, such as 70 cm2/s for liquid-phase exfoliated WS223. In suspended and SiO2-supported single-crystalline WS2, the exciton transport was found to be fluence-dependent with values up to 30 cm2/s26. Several studies reported exciton diffusivities around 10–20 cm2/s for monolayer MoSe224, MoS218, and WSe225. Lower exciton diffusivities have also been documented, such as 0.5 cm2/s for hBN-encapsulated few-layers MoS222. Finally, in some studies, signatures of apparent negative diffusion were reported32. At room temperature, this was observed for supported monolayer MoSe2 and WSe220, and for multilayer WS221. This counter-intuitive behavior usually implies that at least two different species with dissimilar diffusivities and lifetimes contribute to the transport.

These widely varying results indicate that the transport dynamics of TMDCs at room temperature are complex. Indeed, there is currently no unifying microscopic picture that explains the multitude of observations, in particular those during the first tens of picoseconds after photoexcitation. One of the main reasons for this is the difficulty in distinguishing the different species and the need for sub-picosecond time resolution to resolve the fastest processes. Another important reason is that—in most cases—TMDCs were supported on a substrate. When a substrate is present, the dielectric environment can vary from sample to sample and even from location to location on a single sample. These fluctuations in the external dielectric environment strongly impact ultrafast transport dynamics12. While encapsulation with hexagonal boron nitride reduces such dielectric disorder, it also directly influences diffusion22,29. Indeed, hexagonal boron nitride suppresses Coulomb scattering and modifies phonon dispersion18.

Here, we overcome these issues by studying single-crystalline flakes of MoSe2 that are suspended over a hole with a diameter of 15 μm. This minimizes the effect of disorder coming from the surroundings, while inducing only minimal residual stress33. Importantly, we systematically vary the flake thickness down to the monolayer, the pump fluence, and the dielectric environment by comparing suspended and supported flakes. We perform ultrafast spatiotemporal microscopy measurements with ~400 fs time resolution (see Supplementary Fig. S1), and examine the ultrafast transport properties through the time-dependent spatial spreading of the photoresponse. Crucially, we combine the experimental studies with microscopic calculations that consider three species: quasi-free particles, bound excitons, and their interactions with atomic defects acting as trap states. This microscopic model describes the full complexity of the ultrafast transport dynamics of our system by combining microscopically predicted and experimentally measured quantities. These material-specific results can also be applied to other TMDC monolayers (see Supplementary Fig. S12) and will be useful for the development of TMDC-based transistors34, flexible electronic applications35,36,37, sensors38,39,40,41, and photodetectors42,43,44.

Results

Thickness dependence and experimental approach

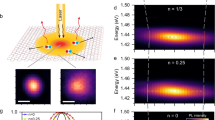

In order to study the ultrafast spatiotemporal dynamics of suspended MoSe2, we perform transient reflection microscopy measurements. After photoexcitation using ultrashort pump pulses, ultrashort probe pulses interrogate the sample with a variable time delay Δt and spatial offset Δx (Fig. 1a)16. When the pump and probe pulses are incident on the same spot on the sample, the pump-induced change of the reflected probe light over time describes the ultrafast dynamics of the photoexcited species (see the “Methods” section for details, and Supplementary Fig. S2 for the schematics of the setup).

a Schematic view of a suspended MoSe2 flake over a hole with a diameter of 15 μm. A pump and a probe beam impinge on the sample at controlled Δx and Δt. b Piezo scanning map acquired with the pump (1.2 μJ/cm2) and probe beams overlapped in time and space. c Normalized spatiotemporal map where both Δx and Δt are varied, showing the spatial spreading of the photoexcitation in time in the bilayer sample. d–f Time-resolved measurements, showing the transient reflectivity as a function of Δt, with Δx = 0, for a suspended trilayer (d), bilayer (e) and monolayer (f) at 20 μJ/cm2, 10 μJ/cm2 and 1 μJ/cm2 respectively. Solid lines indicate the exponential fit. g–i Spatiotemporal measurements, showing the extracted squared width as a function of Δt for a suspended trilayer (g), bilayer (h) and monolayer (i) at 20 μJ/cm2, 0.2 μJ/cm2 and 0.2–1 μJ/cm2 respectively. Multiple measurements are represented for each thickness, represented by different colors. The datasets with the darker orange colors in (g) have been vertically shifted to match the light orange dataset, which is the one acquired with the same alignment as the other thicknesses. The solid line in panel (g) represents trap-limited diffusion. The gradual color bars on top of panels (g–i) represent different regimes of diffusion.

Figure 1d–f shows the transient reflection signal ΔR as a function of time delay for trilayer, bilayer and monolayer suspended MoSe2, respectively. The pump and probe pulses are spatially overlapped, i.e. Δx = Δy = 0. The trilayer sample is representative for all thicker flakes (L > 3), which are shown in the Supplementary Fig. S3. Details about lifetime fits are presented in Supplementary Fig. S4. We observe a biexponential decay for all the thicknesses, with the rapid component becoming faster (from 10 ps to 0.7 ps) and stronger (from 40% to 73% contribution to the decay) when decreasing the sample thickness. Since the probe is resonant with the A exciton (1.52–1.57 eV45, see Supplementary Fig. S5 for control experiments), this decay mostly reflects the exciton lifetime, which is governed by radiative and non-radiative exciton recombination processes, plus a possible additional component due to transport away from the initially excited area.

The literature presents a broad range of interpretations regarding the fast decay dynamics typically observed in monolayer TMDCs, such as exciton-exciton annihilation46, thermal effects46, direct trapping47, defect-assisted recombination47, out-of-center diffusion48, 1s exciton formation47,48,49,50,51,52,53 and surface-environment interaction. In our measurements, the effects of exciton-exciton annihilation and thermal effects seem negligible, because the decay does not change significantly in the employed fluence range of 0.2–20 μJ/cm2 (see Supplementary Fig. S6), whereas exciton-exciton annihilation would lead to faster decay for higher fluence46. Direct trapping and defect-assisted recombination are also unlikely, as the whole population—even at longer times—would be drained by this process otherwise. Finally, out-of-center diffusion influences the decay, but alone it cannot explain the fast component observed, as our simulations show in Supplementary Fig. S4.

In order to perform reliable spatiotemporal measurements, it is a prerequisite to have a spatially homogeneous signal magnitude. We therefore first measure a transient reflection map of the suspended MoSe2 flake with pump and probe beams overlapped in time and space (see Fig. 1b). The signal in the suspended area is homogeneous. In Fig. 1c we show an exemplary spatiotemporal map of a suspended sample by combining a temporal delay between pump and probe pulses with a spatial offset Δx between them. We obtain the ultrafast transport properties by examining the spatial broadening of the signal with pump-probe time delay, as it indicates spreading of the population of photoexcited species.

We show the ultrafast spatiotemporal dynamics in Fig. 1g–i for trilayer, bilayer and monolayer MoSe2. Remarkably, the results vary abruptly upon reducing the number of layers. These plots show the squared width σ2 as a function of time delay Δt. We subtract the pre-time-zero signal from the data, as this corresponds to residual phonon heat that has accumulated in the suspended crystal54. We obtain the width σ from a Gaussian fit of the signal at a given time delay Δt as a function of spatial offset Δx (see Supplementary Fig. S7 for the raw data). The increasing width as a function of time delay shows that the photo-induced excitation spreads in space. We describe this spreading using Fick’s law of diffusion generalized with a time-dependent diffusion coefficient D(t). This gives the following dependence of the squared width as a function of pump-probe time delay: \(\frac{d{\sigma }^{2}(t)}{dt}=2D(t)\). A linear increase of the squared width corresponds to a time-independent diffusivity. Clearly, for all flakes, the diffusivity is time-dependent.

Spatiotemporal dynamics of suspended multilayer MoSe2

We first focus on the multilayer samples and will discuss the monolayer case in the next section, while the bilayer case is qualitatively similar to the monolayer case. The squared width for the trilayer sample starts around 0.12 μm2. This initial width is larger than the expected convoluted one of 0.07–0.11 μm2, given the independently measured widths of the pump and probe focus spots: 135–170 nm and 225–280 nm, respectively (see Supplementary Fig. S8). This mismatch in widths suggests the occurrence of fast initial diffusion that we are not able to resolve. For this initial spreading, we estimate a diffusivity exceeding 100 cm2/s by entering into Fick’s law the width mismatch and the time resolution tres as time difference.

After the initial fast spreading of quasi-free charge carriers, the diffusion is dominated by excitons, which start in a linear regime, before slowing down after a few tens of picoseconds. We describe these transport dynamics with the model from Seitz et al.55: in case trap states are present in a sample with a density Ntraps = 1/λ2, photoexcited species get trapped once they travel a distance comparable to the average distance between trap states λ. Besides impacting the drift56, traps induce an apparent slowing down of diffusion with a characteristic trapping time \({\tau }_{{{{\rm{trap}}}}}=\frac{{\lambda }^{2}}{D}\)29,55. In the trap-limited diffusion model the squared width evolves as: \({\sigma }^{2}(\Delta t)-{\sigma }^{2}(\Delta t=0)=2{\lambda }^{2}\left(1-{e}^{-\frac{D\Delta t}{{\lambda }^{2}}}\right)\). In the limit of no traps (λ → ∞) and in the limit of Δt < < τtrap, the trap model gives the usual linear diffusivity equation σ2(Δt) − σ2(Δt = 0) = 2DΔt.

We compare the spatial spreading for the monolayer, bilayer and trilayer samples during the first few picoseconds in Fig. 2a. For the trilayer case, the solid line shows the result of the trap-limited diffusion model. Using the trap model for the trilayer and thicker flakes, we obtain an average diffusion coefficient of 17 ± 1 cm2/s, as shown in Fig. 2b. The analyzed datasets for thicker samples can be found in Supplementary Fig. S3. This diffusivity is similar to the 19 ± 2 cm2/s for supported bulk MoSe2 found in ref. 24, the 14.5 cm2/s found for WSe227, and the 10.5 cm2/s for WS221. We obtain a trap density that is between 2 × 109 and 5 × 109 /cm2 for the multilayer samples with L ≥ 3 (Fig. 2c). Such a trap density indicates a very high-quality sample, placing it at the highest end of the quality spectrum, being the typical defect densities of CVT-grown bulk MoSe2 (HQ graphene) between 8 × 1010/cm2 and 5 × 1012/cm2 according to ref. 57.

a Comparison of the spatiotemporal spreading during the first few picoseconds for monolayer, bilayer and trilayer MoSe2. Here we removed the intercept of the linear fit from the squared width for each flake. Thinner flakes have a larger slope and thus faster diffusion. The solid lines represent linear diffusion in the cases of monolayer and bilayer. In the trilayer case, the solid line represents trap-limited diffusion, which at early times resembles linear diffusion (dashed line). b Diffusion coefficients corresponding to the solid lines in panel (a), giving an average of 17 ± 1 cm2/s for the trilayer and above. c Trap densities obtained from the trap-limited diffusion model applied to the trilayer and thicker flakes, giving an average of 3 × 109 /cm2. The gradient shading in panels (b) and (c) correspond to the average value with its standard deviation.

Spatiotemporal dynamics of suspended monolayer MoSe2

For monolayer MoSe2 samples, interesting differences appear: the fast decay component gradually becomes more dominant (see Fig. 1d–f), and the transport properties become increasingly complex (see Fig. 1g–i). When varying the pump fluence over more than an order of magnitude – from 0.2 to 25 μJ/cm2—we observe no change in the dynamics (see Fig. 3a). The fluence-independent dynamics suggests that there is no significant contribution from nonlinear effects, in contrast to ref. 20, which used fluences two or three orders of magnitude higher than ours, and reported fluence-dependent decay dynamics for (supported) monolayer flakes. The pronounced biexponential decay indicates that different relaxation and/or transport processes become more dominant compared to the multilayer case, with the fastest component featuring a decay time of around 0.7 ps.

a Normalized experimental dynamics obtained at different fluences that correspond to photoexcited quasi-free carrier densities in the range 5 − 100 × 1010/cm2 (open circles with dashed lines). b Experimentally obtained spreading for 0.2 and 1 μJ/cm2 excitation fluences (filled circles), compared with the calculated spreading for the two corresponding photoexcited quasi-free carrier densities 5 and 25 × 1010/cm2 (solid lines). The diffusion is clearly nonlinear and contains four different diffusion regimes with very fast (Regime I), fast (Regime II), apparent negative (Regime III), and slow (Regime IV) diffusion. The first two regimes correspond to non-thermalized and quasi-thermalized high-energy quasi-free carriers; Regime III corresponds to exciton formation; and Regime IV corresponds to exciton diffusion.

Focusing on the first few picoseconds of the spatiotemporal dynamics, we notice that the initial squared width around Δt = 0 is again larger than the expected one based on the spot sizes of the pump and probe: 0.16 μm2 with the lowest excitation fluence. As in the bilayer and trilayer case, this indicates the occurrence of fast initial diffusion that we are not able to resolve with our time resolution. The estimated diffusivity in this Regime I (< 400 fs) is around 1000 cm2/s. A similar initial diffusivity was obtained for substrate-supported monolayer MoSe220 at room temperature, but with a much larger photoexcited quasi-free carrier density and fluence-dependent dynamics.

After the very fast expansion during photoexcitation (Regime I), there is a second transport regime with a duration of ~1 picosecond. In this “Regime II”, the spreading is increasingly fast for decreasing flake thickness, as shown in Fig. 2a, with a diffusivity of ~35 cm2/s for bilayer and ~60 cm2/s for monolayer, i.e. 2 and 4 times larger than for flakes with L ≥3 (see Fig. 2b). Higher fluences lead to faster diffusion in the two initial regimes (see Fig. 3b), in surprising contrast with the fluence-independent dynamics (see Fig. 3a). Thus, exciton-exciton annihilation can be excluded as a cause of the fluence-dependent diffusivity. We suggest that the two regimes that occur during and directly after photoexcitation are associated with the expansion of quasi-free carriers with excess kinetic energy. This will be fully confirmed by our microscopic predictions, as shown by the solid lines in Fig. 3b, and can be microscopically understood from the competition between the densities of excited quasi-free carriers and traps. Most likely, other slow-diffusing species may be present in this regime, such as the 1s excitons previously addressed. Their slow transport is likely hidden behind the fast diffusion of high-energy quasi-free carriers.

After the two initial regimes with fast diffusion, a regime with rather abrupt apparent negative diffusion occurs. In this “Regime III”, the squared width decreases. An apparent negative diffusion typically occurs when a long-lived slow diffusing species follows a short-lived fast diffusing one. This has been observed for example in gold, where it is caused by the combination of fast electronic heat diffusion and slow phonon heat diffusion58,59. Negative apparent diffusion has also been predicted31,32 and observed60 for resonantly excited W-based materials at cryogenic temperatures and for specific energy-resolved measurements. Negative apparent diffusion at room temperature has been observed in supported monolayer WS221, WSe2 and MoSe220. However, their pump fluences were high enough to have nonlinear effects20 and to induce local temperature gradients21. In our measurements with lower fluence, we are in the linear regime. Moreover, none of the literature works presented above were conducted on suspended samples.

In order to understand the origin of the observed apparent negative diffusion, we note that the negative regime occurs in the transition period from fast to slow decay (see Fig. 1f and i). This suggests that the population of a fast-diffusing species decreases while a new species with slower diffusion starts to dominate the signal after ~1.5 ps. In the next section, we will present a microscopic picture that confirms this assumption, attributing the new population to excitons. The exciton diffusivity in “Regime IV” is on the order of 1−2 cm2/s — in good agreement with the diffusivity of 1 cm2/s that was calculated for monolayer TMDCs32 and the 0.5 cm2/s observed for four-layer MoS222. The exciton monolayer diffusivity is lower than the one of ~17 cm2/s for multilayer MoSe2, since excitons in the monolayer are formed only after an initial equilibrium between traps and quasi-free carriers had already been established.

Microscopic model for monolayer MoSe2

In order to understand the ultrafast spatiotemporal dynamics in monolayer MoSe2, we use a microscopic model that includes quasi-free carriers, excitons, and a continuum distribution of defect states. We treat the momentum and energy thermalization within a relaxation time approximation, see Supplementary section “Microscopic modeling”. Thermalization refers to the process by which excess energy is lost, leading to the system reaching a Boltzmann distribution in the low-density limit. We extrapolate the momentum relaxation times according to the first-principle input for quasi-free carrier mobilities and our evaluation of exciton-phonon scattering rates61. For energy thermalization we take a thermalization velocity of 0.38 eV/ps as microscopically obtained in ref. 52. We neglect other possible off-resonant exciton formation processes, as we focus on exciton transport. The latter is expected to be dominated by the direct resonant formation of highly-mobile electron-hole pairs, whose thermalization eventually results in exciton formation. Finally, for the trap density we use 2.5 × 109/cm2, based on the experimentally obtained results for trap-limited exciton diffusion in multilayer MoSe2 (see Fig. 2c). Importantly, the calculations only contain parameters that are either determined from our independent measurements or obtained from predictions in literature, with no freely adjustable parameters.

In Fig. 3b we compare the experimental results for two different fluences with the theoretical predictions for two initial quasi-free carrier densities, corresponding to the expected photoexcited quasi-free carrier density in the experiment (obtained assuming an absorption at 400 nm similar to the one at 532 nm of 10–33%45). Since the energy of the probe pulses is resonant with the A-exciton, we investigate the combined propagation of bound excitons and trap states, neglecting the direct contribution of quasi-free carriers. The latter are assumed to contribute indirectly to the signal via trapping or scattering with excitons. We find excellent agreement between the microscopic predictions and the experiments in all the four diffusion regimes, illustrated in Fig. 4. In Regime I, the microscopic predictions reproduce the ultrafast spatial broadening taking place during the excitation (centered around delay time Δt = 0). Thus, we can microscopically explain why the first measured spatial profile is larger than the convoluted pump-probe size. This ultrafast expansion is attributed to photoexcited, non-thermalized, high-energy quasi-free carriers. In Regime II, the theoretical predictions reproduce the magnitude of the transient diffusion coefficient as well as its fluence-dependent behaviour. This is attributed to the fast broadening of quasi-thermalized, high-energy quasi-free carriers, which thermalize and get trapped. In Regime III, the model predicts the apparent negative diffusion at a delay around 1.5 ps, which is the transition region between high-energy quasi-free carrier diffusion and exciton diffusion, marked by the scattering of the thermalized quasi-free carriers into bound excitons. Finally, in Regime IV, slow diffusion of excitons occurs. We predict qualitative similar behaviours for other TMDC monolayers, typically with faster transient diffusion than in MoSe2 due to the larger corresponding carrier mobilities (see Supplementary Fig. S12). Below, we describe in detail these four different regimes.

On the left of each panel, a schematic representation of charge carriers and excitons diffusing; on the right of each panel, the energetic description, including the minimum of the quasi-free carrier continuum band (e–h), the exciton energy (X), and the defect state energy (d). The Gaussian shapes represent the amount of spatial density (N) present in each state. Lateral orange arrows indicate diffusion in space (the longer the arrow, the faster the diffusion). a Regime I: ultrafast broadening of photoexcited, non-thermalized, high-energy quasi-free carriers, which get trapped. b) Regime II: fast broadening of quasi-thermalized, high-energy quasi-free carriers, which thermalize and get trapped. c Regime III: transition region between high-energy quasi-free carriers diffusion and exciton diffusion, marked by the scattering of the thermalized quasi-free carriers into bound excitons. d Regime IV: slow broadening of excitons that diffuse in equilibrium with the trap landscape.

Regime I, Δt < 400 fs–Photoexcitation with non-resonant pump energy injects mainly non-thermalized high-energy, quasi-free carriers in the system. These quasi-free carriers have an excess energy determined by the difference between the pump and the bandgap energy. Relaxation of the high-energy quasi-free carriers both in momentum and in energy then occurs via carrier-phonon interaction32. During the initial thermalization, owing to their large excess energy, the quasi-free carriers spread out in space very rapidly and get trapped when they encounter defects (see Fig. 4a), while new quasi-free carriers are continuously being generated by the laser pulse. By including the effects of the finite duration of the laser in the source term, we calculate a diffusivity in this regime DI between 800 cm2/s and 1200 cm2/s depending on the excitation density, see Fig. 3b, and in agreement with our experimental finding of 1000 cm2/s. Here we assume that the experimental probe pulses with an energy of 1.55 eV are not sensitive to high-energy quasi-free carriers, but probe trapped charges. The latter reflects the propagation of the fastest quasi-free carriers, which are the first ones to reach unoccupied defects and be captured there. The ultrafast spreading of non-thermalized high-energy quasi-free carriers that get trapped in defects thus generates a broadened spatial profile on a timescale corresponding to the trapping time \({\tau }_{{{{\rm{trap,I}}}}}=\frac{{\lambda }^{2}}{{D}_{{{{\rm{I}}}}}}\), which is a few hundred femtoseconds and therefore indeed below the experimental time resolution of ~400 fs. With a higher fluence, a larger initial photoexcited quasi-free carrier density is created and therefore there are more high-energy quasi-free carriers able to be captured, leading to a higher diffusivity, as confirmed by both the theoretical prediction and the experiment (see Fig. 3b).

Regime II, 400 fs < Δt < 1.5 ps–During Regime II, the quasi-thermalized high-energy quasi-free charges are losing their energy by thermalizing and emitting phonons. Similarly to Regime I, the high-energy quasi-free carriers spread out until they get trapped in defects (see Fig. 4b). They still have excess energy to some extent and therefore a still relatively large, fluence-dependent diffusivity. As shown in Fig. 3b, the model reproduces the experimentally observed spatial spreading, giving DII ≈ 70–80 cm2/s using the experimental conditions–a photoexcited quasi-free carrier density of 5 × 1010 /cm2 and a trap density of 2.5 × 109 /cm2. Interestingly, we predict a fluence-dependent increase of diffusion both in Regime I and II, in excellent agreement with our experiments. The predicted fluence-dependent diffusion is not due to nonlinear effects induced by interactions between quasi-free carriers or excitons, such as Auger annihilation26,62,63, Mott transition64 or local temperature gradient21. Instead, it happens because of the competition between the density of excited quasi-free carriers and the one of traps. In particular, it is the ratio of these two densities that determines the efficiency of the transient diffusion, rather than the absolute values of each of them individually. In Fig. 3b we keep the trap density fixed while increasing the e-h pair density, hence modifying their ratio. We predict no changes in diffusivity if we vary the two densities while keeping their ratio constant (see Supplementary Figs. S9 and S10).

Regime III, around 1.5 ps–After having lost their excess energy, the thermalized quasi-free carriers form bound excitons (see Fig. 4c). Once Coulomb-bound free excitons are formed, they dominate the probe signal, rather than trapped charges. Since excitons are formed by the coldest and hence slowest quasi-free carriers, during Regime III apparent negative diffusion occurs. Our microscopic model reproduces the magnitude of the spatial shrinking, its timescale and its fluence-dependent behaviour (see Fig. 3b). We obtain interesting insights into the physics of the system by varying the parameters of the simulation. In particular, we predict that a larger photon energy would lead to the occurrence of apparent negative diffusion at a longer pump-probe delay time, because high-energy quasi-free carriers take longer to relax into excitons. Furthermore, the trap density determines the various diffusivities, as shown in the Supplementary Figs. S9 and S10.

Regime IV, Δt > 1.5 ps–Once exciton formation has occurred, the situation is very similar to the multilayer case and trap-limited exciton diffusion dominates (see Fig. 4d). Our microscopic model gives a diffusivity DIV of 1–2 cm2/s in the trap-limited regime, in agreement with experimental results. While in WS2 the quasi-free carriers could have a larger steady-state diffusivity than excitons29 via larger charge mobilities61, here in MoSe2 the excitonic diffusion in Regime IV is much slower than the one in Regime II mostly due to the absence of the large excess energy. Excitonic excess energies could also lead to transient faster diffusion in W-based TMDCs65 at cryogenic temperatures, where the energy thermalization is slower than at room temperature thanks to the suppressed phonon population.

Effect of dielectric environment

Besides providing crucial insights into our experimental observations, the microscopic model also predicts what will happen in the region where the crystal is supported on a substrate, rather than suspended (see Supplementary Fig. S11). The most important effect is that in the supported region, the dielectric inhomogeneity leads to more complex relaxation pathways, and therefore a distribution of thermalization times for the photoexcited quasi-free carriers with excess energy. This will then lead to a less sharp transition to the regime where excitons dominate the diffusion. We experimentally confirm that this indeed happens by performing spatiotemporal measurements on a terraced-like flake with different thicknesses, supported on PDMS (polydimethylsiloxane), as shown in Fig. 5a-f. We observe that Regime II becomes shorter-lived than in the suspended samples, and the total scattering from quasi-free carriers into excitons (Regime III) is therefore less abrupt. Importantly, the spatiotemporal dynamics vary from location to location on the supported monolayer crystal. This explains the strong variation across the different studies of transport dynamics using non-suspended samples, and highlights the importance of studying suspended samples to obtain access to the intrinsic properties.

a Schematic view of a supported MoSe2 flake on a PDMS substrate. b Optical image of the flake with a monolayer (L = 1) region and a trilayer region (L = 3). c, d Time-resolved measurements, showing the transient reflectivity as a function of Δt, with Δx = 0, for a supported trilayer (c) and monolayer (d) at 2 μJ/cm2. e), f) Spatiotemporal measurements, showing the extracted squared width as a function of Δt for a supported trilayer (e) and monolayer (f) at 2 μJ/cm2. Multiple measurements are represented for each thickness, represented by different shades of the same color.

Discussion

In conclusion, we studied the ultrafast transport dynamics in both suspended and supported MoSe2 films, with thicknesses varying down to the monolayer. We combined spatiotemporal microscopy experiments with microscopic simulations—which provided not only a qualitative, but also a quantitative confirmation of our experimental results—and identified four transport and relaxation regimes for suspended monolayer MoSe2: (I) very fast diffusion with a diffusivity on the order of 1000 cm2/s during the excitation of non-thermalized high-energy quasi-free carriers; (II) fast diffusion with a diffusivity of several tens of cm2/s driven by high-energy quasi-free carriers; (III) apparent negative diffusion caused by the formation of excitons; and (IV) slow diffusion with a diffusivity of a few cm2/s governed by trap-limited exciton diffusion. Trapping of quasi-free carriers or excitons in defects plays a key role in all diffusion regimes. The diffusivities in Regimes I and II are fluence-dependent, as they rely on the interplay and relative amount of high-energy quasi-free carriers and defects.

For trilayer (and thicker) suspended MoSe2, the system goes directly from Regime I to a mixed Regime II-III-IV, where the diffusivity is around 17 cm2/s before excited species get trapped. The lack of contraction in the trilayer can be attributed to its distinct temporal and transport dynamics compared to the monolayer. Specifically, the slower thermalization of hot carriers in the trilayer may lead to a less abrupt change in the diffusion coefficient between quasi-free carriers and excitons, suppressing the negative diffusion observed in monolayers (see Supplementary Fig. S6). This highlights the strong dependence of diffusion regimes on thermalization velocity and the evolution of excited species over time.

Finally, the presence of the substrate creates more complex relaxation pathways and dielectric fluctuations, which make Regime II shorter-lived than in the suspended samples. The total scattering from quasi-free carriers into excitons (Regime III) is therefore less abrupt, as reproduced by our microscopic model.

The gained insights explain the broad range of observed diffusivities of TMDCs at room temperature by means of four leading causes. First, at different time delays, different species are present and therefore different diffusivities will be obtained, depending on the transport regime that the system is in. Second, the spatiotemporal dynamics depend on the photon energy of the pump pulses. Indeed, the abrupt apparent negative diffusion takes place at a time that crucially depends on the pump photon energy (see Supplementary Fig. S11). Third, in all regimes the trap density plays a crucial role through the defect-assisted diffusion processes, and such a density depends on the occurrence of sample-to-sample variations. Consequently, diffusion studies could become an important contact-free technique to assess sample quality in terms of trap densities. Fourth, the broad variation of observations in previous studies is likely related to sample-to-sample variations. While we predict qualitatively similar intrinsic transport in different TMDC monolayers (see Supplementary Fig. S12), this intrinsic diffusion is dominant only for suspended samples, while samples that are supported on a substrate experience modified relaxation channels and dielectric fluctuations, which can alter the relaxation and transport pathways. Follow-up work could explore varying the pump wavelength, to verify the predicted delay in negative diffusion for larger photon energy, and varying the probe wavelength even more out of resonance, to explore possible different sensitivities to excitons and trapped charges at different wavelengths. Overall, controlling these four leading causes will be beneficial for the development and optimization of electronic and optoelectronic devices based on TMDCs.

Methods

Sample preparation

Suspended samples are prepared and characterized according to the method described in ref. 45. MoSe2 flakes with 6 different thicknesses— with number of layers L =1, 2, 3, 7, 14, and 20–are prepared by mechanical exfoliation from bulk crystals onto a viscoelastic PDMS stamp. Using dry transfer, they are suspended over titanium (5 nm)-gold (50 nm)-coated silicon nitride substrates that contained a hole with a diameter of 15 μm (Norcada, NTPR005D-C15). These flakes are monocrystalline, and have very clean surfaces and low strain45.

The supported samples, instead, are left on top of the PDMS stamp and not dry-transferred onto the hole.

Transient reflection microscopy

In a typical transient reflection microscopy experiment, an ultrashort pump pulse photoexcites, and an ultrashort probe pulse interrogates the sample with a variable time delay Δt and spatial offset Δx. If the pump and probe pulses are incident on the same spot on the sample (Δx = 0), the pump-induced change of the reflected probe light describes the ultrafast dynamics of the photoexcited species. By combining a temporal delay between pump and probe pulses with a spatial offset Δx between these pulses, ultrafast transport dynamics are obtained16.

In our experiments, we use an excitation wavelength of 400 nm (corresponding to a photon energy of 3.1 eV), which is well above the 1.55 eV exciton resonance of MoSe2. We modulate the pump beam at 4.3 kHz. We keep the pump fluence between 0.2 and 25 μJ/cm2. With an absorption of ~10–50%45 depending on the thickness, this corresponds to a density of 4 − 2500 × 1010 photoexcited quasi-free carriers per cm2. The probe beam is set at a wavelength of 800 nm, corresponding to an energy of 1.55 eV with a bandwidth of ± 10 meV, as determined by the pulse duration via Heisenberg’s uncertainty relation. This means that the probe is mostly sensitive to A excitons, which have an energy of 1.52–1.57 eV, depending on the flake thickness45. We verified that a 15 meV shift in the probe energy does not significantly affect our spatiotemporal dynamics, as demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. S5. All our measurements are performed at room temperature and under ambient conditions.

The schematics of the setup is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S2. A pulsed titanium sapphire (Ti:sapph) oscillator, Coherent Mira 900, outputs pulsed light with a pulse duration of about 150 fs at 76 MHz repetition rate and 800 nm central wavelength ( ± 6 nm) (probe beam). The laser is frequency-doubled using a BBO crystal to generate the pump. After separation of the two wavelengths with a dichroic beam splitter, both beams are precompensated for group velocity dispersion through prism compressors, leading to a time resolution better than 400 fs (10%-90% rise time, Supplementary Fig. S1 for more details). To improve focusing, beams are cleaned by two pinhole-based spatial filters. The pump beam (400 nm) is modulated by an optical chopper, while the probe beam (800 nm) is sent onto a variable delay line and over the scanning galvanometric (galvo) mirrors to change its temporal and spatial overlap with the pump beam, respectively. Both beams are recombined by another dichroic beam splitter before entering the microscope objective (oil immersion, NA = 1.4, 60x magnification) and focused onto the sample, which is placed on top of a movable piezo stage. The transient signal from the sample is collected in reflection. The probe is isolated from the pump beam via a 450 long-pass filter, and detected by an avalanche photodiode (APD), linked to a lock-in amplifier in order to detect little reflectivity changes of the probe (transient signal) due to the presence of a pump beam.

Theoretical model

We microscopically describe the system consisting of quasi-free carriers, excitons and trapped particles, with spatial distributions and densities indicated respectively by \({N}_{{{{\bf{Q}}}}}^{eh}(x,t)\), \({N}_{{{{\bf{Q}}}}}^{X}(x,t)\) and Ntrap(x, t). Both quasi-free carriers and bound excitons are mobile, hence we describe them via a distribution in real and momentum space by exploiting the excitonic Wigner function and by assuming parabolic bands (effective mass approximation). The spatial evolution of quasi-free carriers and excitons is described by including (i) free propagation according to their own group velocity, (ii) phonon-driven momentum- as well as energy-thermalization (both intra- and interband), and (iii) trapping into defect states. Since the captured particles are bound to defects they are not mobile anymore, hence they are described via the momentum-independent density Ntrap(x, t). The maximum of the trap density is limited to one particle for each defect (taking into account the atomic size of defects). Finally, a source term is added to the quasi-free carriers to address the energy- and time-dependent optical excitation. More details can be found in Supplementary Information.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are provided within the Main Article, Supplementary Information File and Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Ugeda, M. M. et al. Giant bandgap renormalization and excitonic effects in a monolayer transition metal dichalcogenide semiconductor. Nat. Mater. 13, 1091–1095 (2014).

Frindt, R. & Yoffe, A. Physical properties of layer structures: optical properties and photoconductivity of thin crystals of molybdenum disulphide. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A. Math. Phys. Sci. 273, 69–83 (1963).

Huang, L. et al. Enhanced light–matter interaction in two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Rep. Prog. Phys. 85, 046401 (2022).

Wurstbauer, U., Miller, B., Parzinger, E. & Holleitner, A. W. Light–matter interaction in transition metal dichalcogenides and their heterostructures. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 50, 173001 (2017).

Wen, X., Gong, Z. & Li, D. Nonlinear optics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. InfoMat 1, 317–337 (2019).

Bikorimana, S. et al. Nonlinear optical responses in two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide multilayer: Ws2, WSe2, MoS2 and Mo0.5W0.5S2. Opt. express 24, 20685–20695 (2016).

Taghizadeh, A. & Pedersen, T. G. Nonlinear optical selection rules of excitons in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 99, 235433 (2019).

Malic, E. et al. Dark excitons in transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 014002 (2018).

Berghäuser, G. et al. Inverted valley polarization in optically excited transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Commun. 9, 971 (2018).

Mak, K. F., Lee, C., Hone, J., Shan, J. & Heinz, T. F. Atomically thin MoS2: a new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 136805 (2010).

Splendiani, A. et al. Emerging photoluminescence in monolayer MoS2. Nano Lett. 10, 1271–1275 (2010).

Raja, A. et al. Dielectric disorder in two-dimensional materials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 832–837 (2019).

Goodman, A. et al. Substrate-dependent exciton diffusion and annihilation in chemically treated MoS2 and WS2. J. Phys. Chem. C. 124, 12175–12184 (2020).

Su, H. et al. Dark-exciton driven energy funneling into dielectric inhomogeneities in two-dimensional semiconductors. Nano Lett. 22, 2843–2850 (2022).

Saleta Reig, D. et al. Unraveling heat transport and dissipation in suspended mose2 from bulk to monolayer. Adv. Mater. 34, 2108352 (2022).

Vazquez, G. D. B. et al. Spatiotemporal microscopy: shining light on transport phenomena. Adv. Electron. Mater. 10, 2300584 (2024).

Malic, E., Perea-Causin, R., Rosati, R., Erkensten, D. & Brem, S. Exciton transport in atomically thin semiconductors. Nat. Commun. 14, 3430 (2023).

Wang, R. et al. Ultrafast and spatially resolved studies of charge carriers in atomically thin molybdenum disulfide. Phys. Rev. B 86, 045406 (2012).

Wang, P. et al. Fast exciton diffusion in monolayer ptse2. Laser Photonics Rev. 16, 2100594 (2022).

Zhou, Y.-K. et al. Transient superdiffusion of energetic carriers in transition metal dichalcogenides visualized by ultrafast pump-probe microscopy. Ultrafast Sci. 2022, 0002 (2022).

Liu, Q. et al. Visualizing hot-carrier expansion and cascaded transport in ws2 by ultrafast transient absorption microscopy. Adv. Sci. 9, 2105746 (2022).

Weaver, H. L. et al. Detecting, distinguishing, and spatiotemporally tracking photogenerated charge and heat at the nanoscale. ACS nano 17, 19011–19021 (2023).

Morabito, F. et al. Long lived photogenerated charge carriers in few-layer transition metal dichalcogenides obtained from liquid phase exfoliation. Nanoscale Adv. 6, 1074–1083 (2024).

Kumar, N. et al. Exciton diffusion in monolayer and bulk mose2. Nanoscale 6, 4915–4919 (2014).

Cui, Q., Ceballos, F., Kumar, N. & Zhao, H. Transient absorption microscopy of monolayer and bulk wse2. ACS nano 8, 2970–2976 (2014).

Kulig, M. et al. Exciton diffusion and halo effects in monolayer semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 207401 (2018).

Cadiz, F. et al. Exciton diffusion in WSe2 monolayers embedded in a van der Waals heterostructure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 152106 (2018).

Leon, D. F. C., Li, Z., Jang, S. W. & Deotare, P. B. Hot exciton transport in WSe2 monolayers. Phys. Rev. B 100, 241401 (2019).

Zipfel, J. et al. Exciton diffusion in monolayer semiconductors with suppressed disorder. Phys. Rev. B 101, 115430 (2020).

Wagner, K. et al. Nonclassical exciton diffusion in monolayer WSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 076801 (2021).

Rosati, R. et al. Non-equilibrium diffusion of dark excitons in atomically thin semiconductors. Nanoscale 13, 19966–19972 (2021).

Rosati, R., Perea-Causin, R., Brem, S. & Malic, E. Negative effective excitonic diffusion in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Nanoscale 12, 356–363 (2020).

Babacic, V. et al. Thickness-dependent elastic softening of few-layer free-standing MoSe2. Adv. Mater. 33, 2008614 (2021).

Chhowalla, M., Jena, D. & Zhang, H. Two-dimensional semiconductors for transistors. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 1–15 (2016).

Jiang, D. et al. Flexible electronics based on 2d transition metal dichalcogenides. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 89–121 (2022).

Daus, A. et al. High-performance flexible nanoscale transistors based on transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Electron. 4, 495–501 (2021).

Zheng, L. et al. Recent progress of flexible electronics by 2d transition metal dichalcogenides. Nano Res. 15, 2413–24320 (2022).

Ko, K. Y. et al. High-performance gas sensor using a large-area ws2xse2−2x alloy for low-power operation wearable applications. ACS Appl. Mater. interfaces 10, 34163–34171 (2018).

Kim, T. H., Kim, Y. H., Park, S. Y., Kim, S. Y. & Jang, H. W. Two-dimensional transition metal disulfides for chemoresistive gas sensing: perspective and challenges. Chemosensors 5, 15 (2017).

Hu, H. et al. Recent advances in two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides for biological sensing. Biosens. Bioelectron. 142, 111573 (2019).

Ping, J., Fan, Z., Sindoro, M., Ying, Y. & Zhang, H. Recent advances in sensing applications of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide nanosheets and their composites. Adv. Funct. Mater. 27, 1605817 (2017).

Velusamy, D. B. et al. Flexible transition metal dichalcogenide nanosheets for band-selective photodetection. Nat. Commun. 6, 8063 (2015).

Mu, C., Xiang, J. & Liu, Z. Photodetectors based on sensitized two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides -" a review. J. Mater. Res. 32, 4115–4131 (2017).

Mueller, T. & Malic, E. Exciton physics and device application of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide semiconductors. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 2, 29 (2018).

Varghese, S. et al. Fabrication and characterization of large-area suspended mose2 crystals down to the monolayer. J. Phys.: Mater. 4, 046001 (2021).

Shi, H. et al. Exciton dynamics in suspended monolayer and few-layer mos2 2d crystals. ACS nano 7, 1072–1080 (2013).

Valencia-Acuna, P. et al. Transient absorption of transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers studied by a photodope-pump-probe technique. Phys. Rev. B 102, 035414 (2020).

Ceballos, F., Cui, Q., Bellus, M. Z. & Zhao, H. Exciton formation in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Nanoscale 8, 11681–11688 (2016).

Perea-Causín, R., Brem, S. & Malic, E. Microscopic modeling of pump–probe spectroscopy and population inversion in transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. status solidi (b) 257, 2000223 (2020).

Trovatello, C. et al. The ultrafast onset of exciton formation in 2d semiconductors. Nat. Commun. 11, 5277 (2020).

Steinleitner, P. et al. Direct observation of ultrafast exciton formation in a monolayer of wse2. Nano Lett. 17, 1455–1460 (2017).

Brem, S., Selig, M., Berghaeuser, G. & Malic, E. Exciton relaxation cascade in two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Sci. Rep. 8, 8238 (2018).

Cha, S. et al. 1 s-intraexcitonic dynamics in monolayer mos2 probed by ultrafast mid-infrared spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 7, 10768 (2016).

Varghese, S. et al. A pre-time-zero spatiotemporal microscopy technique for the ultrasensitive determination of the thermal diffusivity of thin films. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 94, 034903 (2023).

Seitz, M. et al. Exciton diffusion in two-dimensional metal-halide perovskites. Nat. Commun. 11, 2035 (2020).

Li, Z. et al. Enhanced exciton drift transport through suppressed diffusion in one-dimensional guides. ACS nano 17, 22410–22417 (2023).

Kim, B. et al. Free trions with near-unity quantum yield in monolayer mose2. ACS nano 16, 140–147 (2021).

Block, A. et al. Tracking ultrafast hot-electron diffusion in space and time by ultrafast thermomodulation microscopy. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav8965 (2019).

Block, A. et al. Observation of negative effective thermal diffusion in gold films. ACS Photonics 10, 1150–1158 (2023).

Beret, D. et al. Nonlinear diffusion of negatively charged excitons in monolayer WSe2. Phys. Rev. B 107, 045420 (2023).

Jin, Z., Li, X., Mullen, J. T. & Kim, K. W. Intrinsic transport properties of electrons and holes in monolayer transition-metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 90, 045422 (2014).

Perea-Causin, R. et al. Exciton propagation and halo formation in two-dimensional materials. Nano Lett. 19, 7317–7323 (2019).

Erkensten, D. et al. Dark exciton-exciton annihilation in monolayer WSe2. Phys. Rev. B 104, L241406 (2021).

Steinhoff, A. et al. Exciton fission in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenide semiconductors. Nat. Commun. 8, 1166 (2017).

Rosati, R. et al. Dark exciton anti-funneling in atomically thin semiconductors. Nat. Commun. 12, 7221 (2021).

Acknowledgements

G.L.G.M., G.D.B.V. and N.F.v.H. acknowledge support through the MCIN/AEI projects PID2021-123814OB-I00, TED2021-129241BI00, the “Severo Ochoa” program for Centres of Excellence in R&D CEX2019-000910-S, Fundacio Privada Cellex, Fundacio Privada Mir-Puig, and the Generalitat de Catalunya through the CERCA program. G.L.G.M. is supported through the MCIN/AEI project PRE2019-091051. N.F.v.H. acknowledges the financial support by the European Commission (ERC Advanced Grant 101054846 - FastTrack). This work is part of the ICFO Clean Planet Program supported by Fundació Joan Ribas Araquistain (FJRA). S.V. and D.S.R. acknowledge the support of the Spanish Ministry of Economy through FPI-SO2018 and FPI-SO2019, respectively. K.J.T. acknowledges funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under Grant Agreement No. 804349 (ERC StG CUHL) and FLAG-ERA grant ENPHOCAL, by MICIN with No. PCI2021-122101-2A (Spain). ICN2 was supported by the Severo Ochoa program from Spanish MINECO grant no. SEV-2017-0706. E.M. and R.R. acknowledge financial support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) via SFB 1083 as well as the regular project 542873285. The authors acknowledge Pawel Wozniak for his contribution in the first stage of the paper and the acquisition of some preliminary results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.J.T., N.F.v.H, G.L.G.M., S.V., D.S.R., and G.D.B.V. conceived and designed the research. G.L.G.M. performed the measurements. G.L.G.M. and G.D.B.V. analyzed the data. S.V. and D.S.R. fabricated the supported and suspended samples. R.R. and E.M. conceived and developed the microscopic model. R.R. performed the simulations. G.L.G.M. and K.J.T. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the the interpretation of data, discussion and writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lo Gerfo Morganti, G., Rosati, R., Brinatti Vazquez, G.D. et al. Transient ultrafast and negative diffusion of charge carriers in suspended MoSe2 from multilayer to monolayer. Nat Commun 16, 5184 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60197-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60197-3

This article is cited by

-

MOCVD growth of covalent and 2D GaxSey: a phase validation and characterization

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2025)