Abstract

The primary aim of the present randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was to investigate whether clindamycin and live Lactobacillus crispatus CTV-05 (LACTIN-V) would improve clinical pregnancy rates in IVF patients with abnormal vaginal microbiota (AVM) defined by high quantitative PCR loads of Fannyhessea vaginae and Gardnerella spp. IVF patients were randomised prior to embryo transfer into three parallel groups 1:1:1. Group one (CLLA) received clindamycin 300 mg ×2 daily for 7 days followed by vaginal LACTIN-V until the day of pregnancy scan. Group two (CLPL) received clindamycin and placebo LACTIN-V, and finally, group three (PLPL) received an identical placebo of both drugs. A total of 1533 patients were screened, and 338 patients were randomised. The clinical pregnancy rates per embryo transfer were 42% (95%CI 32–52%), 46% (95%CI 36–56%) and 45% (95%CI 35–56%) in the CLLA, CLPL, PLPL groups respectively. Thus, treatment of AVM did not improve reproductive outcome. The EudraCT (European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Clinical Trials Database) clinical trial identifier is 2016-002385-31; first registration day 2016-07-11.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A symbiotic relationship exists between reproductive-age women and a “normal” Lactobacillus dominant vaginal microbiota, reducing the acquisition of sexually transmitted infections such as Chlamydia, Herpes, HPV and HIV1,2,3,4. In contrast, the reproductive implications of having a subclinical non-Lactobacillus dominant vaginal dysbiosis are less clear. A non-Lactobacillus dominant vaginal dysbiosis can be defined either by molecular methods or by microscopy, predominantly dividing vaginal dysbiosis into bacterial vaginosis (BV) type and aerobic vaginitis (AV) type5. BV-type vaginal dysbiosis is usually dominated by Gardnerella spp. and/or Fannyhessea vaginae whereas AV-type is dominated by Streptococcus spp. and Enterobacteriacae5,6.

Vaginal dysbiosis is relatively common in the IVF population as seen in a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, including 26 studies, in which the prevalence of vaginal dysbiosis overall was 19% (95%CI 18–20%)7. The underlying hypothesis of the present study is that vaginal dysbiotic microbiota ascends to the endometrium, hampering embryo implantation and early pregnancy. As evidence behind this hypothesis, it has been reported that patients with BV have an increased risk of typical BV-type bacteria (e.g., Gardnerella) in the endometrium8. In one study, the odds ratio was 5.7 (95% CI, 1.8–18.3) for endometrial bacterial colonization in women with BV as compared to women without BV9. Moreover, in infertile women, there may be a link between the endometrial bacterial composition and chronic endometritis—interestingly including both BV- and AV-type bacteria10,11.

In the IVF population, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis reported a significantly reduced clinical pregnancy rate per embryo transfer in patients with vaginal dysbiosis, RR = 0.82 (95%CI 0.70–0.95, I2 = 49%) as well as an increased risk of early pregnancy loss (RR 1.49 ;95%CI 1.15–1.94, I2 = 38%) when compared to IVF patients without vaginal dysbiosis7. Moreover, recent studies, exploring endometrial microbiota in IVF patients reported that Lactobacillus dominant—especially Lactobacillus crispatus dominant—endometrial microbiota is associated with the most optimal reproductive outcome12,13. In contrast, the typical BV- and AV-type bacterial composition of endometrial dysbiosis were associated with poor reproductive outcomes13. Finally, in a prospective cohort of women undergoing ultrasound scans during the first trimester, euploid pregnancy loss was associated with a Lactobacillus-depleted vaginal microbiota14.

In modern IVF, even young women <35 years cannot be expected to exceed implantation rates of 60–70% following euploid blastocyst transfer15. Moreover, it is widely accepted that the remaining approximately 30–40% of implantation failures are a black box which may predominantly be caused by uterine factors. In this aspect, it might be hypothesized that genital tract dysbiosis could contribute to failed embryo implantation and early pregnancy loss. However, the evidence is inconclusive as to whether genital tract dysbiosis is causally involved in infertility. The vaginal dysbiosis primarily investigated herein is termed abnormal vaginal microbiota (AVM) and defined by high quantitative PCR loads of F. vaginae and/or Gardnerella spp. as explained in methods. AVM is a BV-type vaginal dysbiosis with an assumed high risk of endometrial dysbiosis and poor reproductive outcome. Previously, we reported on the advantages of a molecular-based diagnosis of vaginal dysbiosis in IVF patients16. Herein it was discussed (1) that a more objective diagnosis could be made as microscopists had significant inter-rater variability using Nugent score and (2) a molecular test enabled dichotomisation of the Nugent intermediate group which is difficult to interpret clinically; and (3) the establishment of quantitative thresholds using key vaginal bacteria to detect IVF patients at risk of a poor reproductive outcome due to ascending bacterial infection—i.e., the assumption was that the more bacteria in the vagina the more likely these bacteria were to ascend to the endometrium. Considering intervention, we decided to use clindamycin as it has been shown previously that Gardnerella isolates from patients with chronic endometritis are highly resistant to metronidazole and not clindamycin17. Apart from standard antibiotic treatment of BV, a so-called live biotherapeutic product containing live L. crispatus CTV-05 (LACTIN-V) has recently been shown to significantly reduce recurrent BV after 12 and 24 weeks post-treatment when used as an add-on to standard antibiotic therapy18. However, a potential effect on the reproductive outcome of antibiotic treatment and LACTIN-V in IVF patients has not been investigated. Thus, we aimed to investigate whether diagnosis and treatment of a BV-type vaginal dysbiosis prior to embryo transfer would improve the reproductive outcomes of IVF patients.

In this work, we show that treatment of BV-type vaginal dysbiosis in IVF patients with clindamycin alone or in combination with LACTIN-V prior to embryo transfer results in similar reproductive outcome when compared to placebo.

Results

Patient enrolment

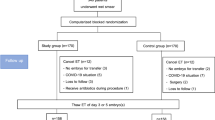

Between December 7, 2017, and September 21, 2022, a total of 1533 IVF patients were screened for AVM. Subsequently, a total of 338 patients were randomised. Failure to meet the inclusion criteria was predominantly due to absence of AVM (N = 1003). Despite being positive for AVM, a total of 19 patients declined to participate in the RCT and in addition, 36 patients conceived spontaneously before randomisation.

For the intention to treat (ITT) analysis, we excluded 3 patients within 24 h after randomisation in which we did not record further data in our database. One patient developed appendicitis (took one tablet of clindamycin), another patient did not take any study medication at all as the pills were too big to swallow, and the last patient was randomised despite not being positive for AVM because of a reading error in the laboratory that was discovered early.

During the time of the interim analysis, we discovered a laboratory error that resulted in five patients being incorrectly randomised and who underwent full study protocol despite not having AVM at the time of screening. Thus, it was decided to compensate with five additional patients who had the same randomization allocation as the incorrectly diagnosed and randomised patients. Considering modified (m)ITT analysis, we decided not to include the five patients who were incorrectly diagnosed and randomised but instead included the additional five patients randomised. Moreover, four patients were randomised erroneously as the AVM screening test was more than 90 days old before actual randomisation. Finally, one patient turned out to be pregnant few days after randomisation. Thus, the abovementioned 10 patients, who did not meet in/exclusion criteria and additionally 59 patients who did not undergo embryo transfer <63 days from randomisation were not included in the mITT analysis. For the mITT analysis, this resulted in 94 patients allocated to clindamycin and LACTIN-V (CLLA), 88 patients receiving clindamycin and placebo LACTIN-V (CLPL), and 84 patients allocated to placebo clindamycin and placebo LACTIN-V (PLPL). A detailed overview can be seen in the Consort flowchart, Fig. 1.

Baseline characteristics

In Table 1 the baseline characteristics are shown at the mITT level. There were no statistically significant differences between the three groups in any of the background variables. Most patients (88%) were randomised in a fresh cycle and this study reports no differences between groups considering the number of oocytes retrieved and the availability of a blastocyst for transfer. A total of 14 patients (5%) received antibiotic prophylaxis at the time of oocyte retrieval due to e.g., endometriosis. Notably, prophylactic antibiotic treatment is not a standard for all patients at oocyte retrieval in the participating clinics.

Primary outcome

In the primary analysis considering the mITT population, the crude clinical pregnancy rate per embryo transfer was 41% (95%CI 32–53%), 47% (95%CI 37–58%) and 45% (95%CI 36–57%) in the CLLA, CLPL, PLPL groups respectively. Following adjustment for embryo quality and female age the clinical pregnancy rate was 42% (95%CI 32–52%), 46% (95%CI 36–56%) and 45% (95%CI 35–56%) in the CLLA, CLPL, and PLPL groups respectively, Table 2. The average effect of the two active groups compared to the PLPL group was close to unity, aRR 0.98 (95%CI 0.74–1.29). Both the PP and the ITT analyses were similar to the mITT analysis and did not show any statistically significant differences between the three groups, supplementary Table S1.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes from the mITT analysis can be seen in Table 2. The adjusted positive hCG rate per embryo transfer was 62% (95%CI 52–71%), 65% (95%CI 56–75%) and 59% (95%CI 49–69%) in the CLLA, CLPL, PLPL group respectively. The adjusted ongoing pregnancy rate was 41% (95%CI 31–51%), 45% (95%CI 35–55%) and 44% (95%CI 34–55%) in the CLLA, CLPL, PLPL group respectively. Finally, the adjusted live birth rate did not differ significantly, 40% (95%CI 30–50%), 45% (95%CI 35–55%) and 40% (95%CI 30–51%) in the CLLA, CLPL, PLPL groups respectively. There were no preterm births prior to week 34 and the number of preterm births prior to week 37 was 4 (4%), 2 (2%) and 4 (5%) in the CLLA, CLPL, PLPL group respectively, P = 0.72.

Adverse events

The adverse events differed significantly between groups, Table 3. We report a statistically significant increase in diarrhoea and abdominal pain in the two active clindamycin groups compared to the PLPL group, RR 2.92 (95%CI 1.26–6.76) and RR 2.19 (95%CI 1.05–4.58), respectively. An increased risk of vaginal candidiasis was close to statistical significance in the two clindamycin groups compared to PLPL. Compared to the two arms receiving placebo LACTIN-V, more patients experienced vaginal itching in the active LACTIN-V arm, RR 4.09 (95%CI 1.26–13.29). Finally, a significant higher proportion of patients suspected that they received active clindamycin in the two active clindamycin groups compared to the PLPL group, RR 1.46 (95%CI 1.09–1.95). Importantly, there was nearly 100% compliance to study medication. For clindamycin, patients were asked to return the pillbox to the clinic after completion and 232/335 (69%) did whereas the remainder told the clinic that they forgot the pillbox but took all pills. Only 3 patients returned clindamycin pills. This was due to the tablets being too big for them to swallow. Moreover, a total of seven serious adverse events were registered without being suspected to be adverse reactions. The list of serious adverse events can be seen in supplementary Table S2.

Treatment of AVM and post hoc analyses on reproductive outcome

As stated in the research protocol19, consecutive vaginal samples were taken during the RCT; among them on the day of randomisation and at embryo transfer. In the mITT population, the total number of AVM positives on the randomisation day was 78% (204/261, 95%CI 73–83%). Thus, due to a potential misclassification bias caused by randomising AVM negatives, we made a post hoc sensitivity analysis on the mITT-level for all patients with AVM at the randomisation day. However, we found no significant differences in reproductive outcomes between the randomised groups as based on AVM on the randomisation day (Table 4). Moreover, patients without AVM on the randomisation day (N = 57) had an overall clinical pregnancy rate non-significantly different when compared to AVM positives, 49% (95%CI 36–62%). The number of patients who were successfully treated for AVM at embryo transfer (AVM at randomisation, but not at embryo transfer) was 100% (61/61), 75% (43/57) and 36% (22/61) in the CLLA, CLPL and PLPL groups, respectively, P < 0.01. All the above-mentioned treatment success rates were significantly different compared both pairwise within the respective groups to the spontaneous cure rate prior to randomisation as well as significantly different when compared independently between groups. In addition, we report an overall non-significantly increased clinical pregnancy rate in case of AVM at embryo transfer, RR 1.13 (95%CI 0.81–1.56) when compared to patients not having AVM at embryo transfer. This was primarily seen in the PLPL group in which a higher but statistically non-significant clinical pregnancy rate was seen in the AVM positive group when compared to AVM negatives at embryo transfer day, RR 1.63 (95%CI 0.96–2.76). In Table 4, we also report the reproductive outcome in patients stratified by vaginal community state types (CST) on randomisation day using deferred data analysis from 16S rRNA gene sequencing as described in methods. Within CST IV-A + B (BV-type), CST IV-C (AV-type) and CST I, II, III, V (Lactobacillus dominant CSTs), we did not see a significant effect of either of the three treatment groups on pregnancy outcome, Table 4. Subsequently, we compared the overall CST IV group against the combined group of all Lactobacillus dominant CSTs on the day of randomisation regardless of allocated treatment and by mITT criteria and found a significantly higher clinical pregnancy rate in the Lactobacillus dominant group, RR 1.36 (95%CI 1.00–1.85). For comparison, this was not seen in the comparative Lactobacillus dominant group at embryo transfer in which the clinical pregnancy rate was non-significantly lower compared to patients with CST IV at embryo transfer, RR 0.93 (95%CI 0.71–1.22). Finally, we investigated a potential differential effect in primary outcome between patients randomised in fresh and frozen embryo transfer cycles and observed no statistically significant differences between groups (Tables S3 and S4).

Discussion

The present drug intervention trial found no evidence of an improved reproductive outcome in the two active treatment groups (CLLA and CLPL), separately or combined when compared to placebo (PLPL) in IVF patients diagnosed with AVM. In contrast, patients reported significantly more adverse events such as abdominal pain, diarrhoea, and vaginal itching in the active treatment groups. Importantly, the reproductive outcome of the three groups was very close to unity despite superior treatment efficacy of AVM in the CLLA and CLPL group compared to the PLPL group. In post hoc analysis, we report similar results for patients having CST IV on randomisation day in whom we observed no significant treatment effect on the reproductive outcome when comparing intervention with CLLA, CLPL and PLPL.

The result of the present study was unexpected as multiple previous studies reported an association between genital tract dysbiosis and the reproductive outcome of IVF patients. Actually, one of those association studies was from our own group in 201616 in which a comparable group of IVF patients with untreated AVM had a clinical pregnancy rate per embryo transfer of 9% (2/22) compared to 44% (27/62) in the PLPL group of the present study. In consideration of the small sample size in the initial study, we hypothesized a more conservative effect of intervention in the present study where the clinical pregnancy rate per embryo transfer was estimated to be 20% in the PLPL group compared to 40% in the CLPL group. However, based on the results of the present study, this hypothesis may now be rejected. It is important to note the superior treatment efficacy of vaginal dysbiosis in the CLLA and CLPL groups compared to the PLPL group. Thus, due to a succesfull bacterial treatment but no effect on reproductive outcome, the present study questions the biological plausibility that BV-type vaginal dysbiosis (AVM or CST IV-A + B) may causatively affect the reproductive outcome. In addition, although active treatment caused more side-effects, intervention with CLLA, CLPL and PLPL did not negatively affect the reproductive outcome in neither AVM negative patients nor in patients with a Lactobacillus dominant CST at the time of randomisation.

As regards external validity of the initial findings, a systematic review and meta-analysis was recently updated to investigate the overall association between vaginal dysbiosis and the reproductive outcomes of IVF patients7. The results of the meta-analysis were somewhat conflicting; Although the vaginal dysbiosis group had a lower risk of clinical pregnancy per embryo transfer (RR 0.82 ;95%CI 0.70–0.95, 25 studies) as well as an increased risk of early pregnancy loss (RR 1.49; 95%CI 1.15–1.94, 20 studies) compared to the non-dysbiosis group, the impact on live birth rate of both the overall vaginal dysbiosis group and a sub-stratified BV-type vaginal dysbiosis group was statistically non-significant, RR 0.94 (95%CI 0.76–1.16, 14 studies) and RR 0.96 (95%CI 0.76–1.21, 13 studies). Although this might be due to fewer studies having follow-up at the time of live birth, the true impact of vaginal dysbiosis on the reproductive outcome of IVF patients may in any case be smaller than hypothesized in the sample size calculation of the present study. However, neither in the planned nor in the post hoc analyses of the present study was it possible to extract any treatment effect on the reproductive outcome when comparing the CLLA, CLPL and PLPL groups. In contrast, in the post hoc analysis we found that patients who had a spontaneously occurring Lactobacillus dominant CST on the day of randomisation seemed to have a better clinical pregnancy rate regardless of the allocated treatment group; interestingly this effect was not seen in the corresponding Lactobacillus dominant group on the day of embryo transfer which was impacted by the allocated treatment. This might be interpreted as an a priori more optimal reproductive outcome in the patients with a spontaneously occurring Lactobacillus dominant CST and, thus an effect independent of treatment. In fact, the findings of the present study are somewhat in line with the recent debate regarding treatment of BV for the prevention of preterm birth in which a significant association between BV and preterm birth was reported by a meta-analysis20, whereas the largest intervention trial21 did not show any benefit from treatment. Consequently, clinical guidelines22,23 do not recommend treating BV in order to reduce preterm birth.

In the present study, we found a significantly higher spontaneous AVM cure rate of 36% in the PLPL group from the time of randomisation to embryo transfer as compared to the overall spontaneous AVM cure rate of 22% from screening to randomisation. This difference may indicate a positive AVM treatment effect of the LACTIN-V placebo containing mainly maltodextrin (a glucose polymer), which theoretically might have contributed to a higher pregnancy rate in the PLPL group. In line with this, a study in the rhesus macaque indeed showed that a vaginal gel containing maltose (a dimer of glucose) significantly increased the abundance of Lactobacillus in the vagina24. However, restricting the analysis of the present study to IVF patients who remained AVM positive at embryo transfer and who were given PLPL showed a clinical pregnancy rate of 58% (23/40) as compared to PLPL patients not having AVM at embryo transfer who had a clinical pregnancy rate of 35% (12/34), RR 1.63 (95%CI 0.96–2.76). Results were similar for grouping by CST IV in PLPL patients at embryo transfer day. Thus, the potential treatment effect on AVM or CST IV of the PLPL groups seems independent and not related to the reproductive outcome. Moreover, if causal inference does exist between AVM/CST IV and a poorer reproductive outcome, it would be expected that the substantial number of AVM/CST IV positives in the PLPL group had a poorer reproductive outcome—which we did not find. As based on the abovementioned lack of biological plausibility of an active effect of PLPL on the reproductive outcome, we do not consider that an active placebo effect has impacted the results of the present RCT, albeit a control group of AVM positives with no intervention would have been optimal.

The most recent Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis on the use of antibiotics prior to embryo transfer published November 2023 reported low certainty according to GRADE, considering all reproductive outcomes, including clinical pregnancy rate, odds ratio 1.01 (95%CI 0.67–1.55, 2 RCTs) in the treated group compared to the untreated group25. The finding of the present RCT adds certainty to the conclusions published previously, albeit it is important to note that both studies included in the Cochrane review considered IVF patients not targeted for genital tract dysbiosis prior to embryo transfer.

To the best of our knowledge, only a few smaller intervention studies have been published in IVF patients diagnosed with vaginal or endometrial dysbiosis, also reporting on reproductive outcomes. Thus, Eldivan et al.26 randomised IVF patients on the first day of ovarian stimulation to screening and subsequent treatment for BV, trichomoniasis, chlamydia and gonorrhoea. The comparator was patients who were randomised to no screening for the abovementioned microorganisms, but who were treated as standard patients. A total of 17/45 (38%) IVF patients were positive for BV using Nugent’s criteria, and they received treatment with oral metronidazole 500 mg two times daily for 7 days before embryo transfer. Despite treatment, only 4/17 (24%) conceived (hCG positive) in the BV-treated group compared to a conception rate of 12/28 (43%) in patients screened negative for BV. In the unscreened group, the conception rate was 14/40 (35%). Although the results were not statistically significant, the study suggested that the poor reproductive outcome seen in the BV-positive group persisted regardless of metronidazole treatment. The present RCT adds to that explanation as the reproductive outcome of the present study was close to unity in the two active treatment arms compared to PLPL. Thus, treatment of vaginal dysbiosis does not seem to increase the reproductive outcome of IVF patients, but as previously discussed, an IVF patient with a Lactobacillus dominant CST may have an a priori better reproductive outcome induced by an unknown mechanism.

One of the largest studies on the association between IVF outcomes and endometrial microbiota based on 16S rRNA gene sequencing reported that the genera Gardnerella and Atopobium (now Fannyhessea) were significantly associated with a poor reproductive outcome whereas the genus Lactobacillus was significantly associated with an optimal reproductive outcome13. We recognise that this does not constitute evidence of a direct correlation between vaginal and endometrial microbiota, however, taken together the similarity to the vaginal microbiota is striking. Moreover, a recent study by our group in IVF patients and oocyte donors concluded that a bacterial gradient of similar composition including AVM as defined herein was present ranging from high bacterial loads in the vagina, to 2 orders of magnitude lower in the cervix and 3 orders of magnitude lower in the endometrium27. Considering evidence for the intervention actually making an impact on the endometrial microbiota, recent non-randomised intervention trials has shown that the combination of oral antibiotics and vaginal lactobacillus supplementation can change the endometrial microbiota into a Lactobacillus dominant state28,29. Moreover, it has been proven that oral intake of clindamycin reaches the endometrium30.

Strengths and limitations

One of the primary strengths of the present study is the RCT design, monitored according to the ICH-GCP guidelines reporting on both efficacy and safety. Under the hypothesis of a 20% clinical pregnancy rate in the PLPL group as compared to a 40% clinical pregnancy rate in the CLPL group, the actual statistical power in the primary analysis described (mITT) was 0.82. As discussed above considering external validity of associative studies published until recently, the relative risk estimate of BV-type dysbiosis on the IVF outcome may be smaller than hypothesized herein. However, there is not even a trend of a difference between the three treatment groups in the present RCT, which would make it unlikely that the potential lack of power in the study may have hidden a true treatment effect. Moreover, this RCT provides evidence of vaginal microbiota changes alongside intervention which questions the causality between BV-type dysbiosis and the reproductive outcome.

This RCT investigated screening and treatment of AVM as an add-on to standard clinical practice as we hypothesized that this might have been the future strategy for all IVF patients, regardless of infertility diagnosis. Thus, the study had relatively broad inclusion criteria, at large mimicking the clinical setting of daily standard IVF patients. Currently, after study completion and the study showing no difference, it can be discussed whether a more targeted approach in certain patient groups would yield different results. As an example, we included patients undergoing both fresh and frozen embryo transfer cycles as we considered treatment prior to embryo transfer to be the primary objective and, thus, disregarded any differential effect that these two IVF treatments (fresh/frozen cycle) might have on the vaginal microbiota and the reproductive outcome. Randomising in frozen embryo transfer cycles, only, would eliminate the potential bias from randomisation before oocyte retrieval, as patients in a fresh cycle may not have embryo transfer within the study intervention period. However, in the present study, we did not see any statistical difference in primary outcome across the randomised groups when comparing fresh and frozen embryo transfer cycles.

One of the important limitations of the present study is the spontaneous AVM cure rate of 22% from screening to randomisation. Based on recent evidence regarding temporal dynamics of the vaginal microbiota31, this spontaneous cure rate is probably what might be expected. Nevertheless, sensitivity analysis of AVM or CST IV positive patients from the vaginal swabs taken on the day of randomisation did not yield different results, Table 4. The AVM diagnosis was used in the present study as this study was designed in 2016 where 16S rRNA gene sequencing was not as available as today and because the turn-around time would not allow timely intervention. Moreover, we considered the importance of targeting total abundance of BV bacteria and not the relative abundance as in 16S rRNA gene sequencing. We consider AVM a BV-type vaginal dysbiosis based on previous findings of high sensitivity and specificity towards Nugent score BV16 and CST IV32, however small differences exist. Finally, the assumption that vaginal dysbiosis can be used as a proxy of endometrial dysbiosis might be challenged and, thus, we cannot exclude that a specific screening and treatment for endometrial dysbiosis would yield different results.

In conclusion, the results of this RCT do not support treatment of AVM or CST IV in IVF patients with clindamycin alone or in combination with LACTIN-V prior to embryo transfer in order to improve reproductive outcomes. Moreover, the present RCT challenges the hypothesis that a BV-type vaginal dysbiosis might be causally linked to reproductive outcomes as successful treatment of AVM and CST IV was independent and not related to the reproductive success of IVF. Thus, screening the general IVF population for BV-type vaginal dysbiosis cannot be recommended in a clinical setting.

Methods

The present research complies with all relevant ethical regulations. The present study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee in Central Denmark Region as well as by Danish Health Authority and Danish Data protection agency prior to commencing the study.

Study design

This randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial (RCT) was conducted at three University-affiliated fertility clinics and one private fertility clinic in Denmark. The EudraCT clinical trial identifier is 2016-002385-31; first registration day 2016-07-11. The current version of the protocol is 11, 2021-04-29. The trial protocol was published in 202019. The primary centre from which the ethical approval was accepted was Skive Regional Hospital.

Patients

Inclusion criteria were, female aged 18–42 years old, BMI < 35, negative chlamydia/gonorrhoea test within 6 months of IVF treatment, normal cervical smear within 3 years of IVF treatment, written informed consent, and AVM, according to criteria stated below with the vaginal swab being obtained less than 90 days before the randomisation day. Exclusion criteria were Hepatitis/HIV positivity, intrauterine malformations and severe concomitant disease, including inflammatory bowel disease. Patients were not allowed to take vaginal probiotics, neuromuscular blocking drugs, immunosuppressive medication, or investigational drug preparations other than the study product. Each patient could only participate once. Patients were approached when attending their first, second or third IVF stimulation cycle or frozen embryo transfer (FET) therefrom. If eligible, a vaginal swab was collected by the treating physician (N = 1238) or the patient herself (N = 273) using the ESwab™ system (Copan, Brescia, Italy). Previous studies found that self-collection of vaginal swabs is as valid as physician obtained swabs both considering qPCR of e.g., Gardnerella33 and sequencing34. The ESwab™ was subsequently shipped for central testing at Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen where it was analysed for AVM according to criteria stated below and as previously reported16. AVM is a qPCR-based diagnosis of a BV-type vaginal dysbiosis, targeting a high absolute abundance of Gardnerella spp. and/or F. vaginae with 93% sensitivity and 93% specificity compared to BV diagnosed by Nugent score (Gold standard)16. Patients were randomised on the first day of ovarian stimulation or during the first days of elective FET allowing for at least 12 days of study medication.

Randomisation, masking and intervention

The present RCT randomised three parallel groups 1:1:1. The first active treatment arm (CLLA) consisted of oral clindamycin 300 mg two times daily for 7 days followed by vaginal LACTIN-V (Osel Inc.). LACTIN-V is an investigational drug that contains L. crispatus CTV-05 (2 × 109 CFU/dose, 200 mg, delivered with pre-filled, single-use vaginal applicators) which was applied vaginally once daily after the last day of clindamycin treatment for a total of 7 consecutive days; thereafter twice weekly up to a total usage of 21 applicators or until completion of the clinical pregnancy scan at week 7–9.

The second active treatment arm (CLPL) consisted of oral clindamycin 300 mg, twice daily for 7 days followed by a LACTIN-V placebo as in the regimen described above.

Finally, the inactive treatment arm (PLPL) consisted of an identically appearing clindamycin placebo and a LACTIN-V placebo. Placebo clindamycin consisted of encapsulated mannitol. The placebo LACTIN-V formulation contained the same ingredients as LACTIN-V, without L. crispatus CTV-05.

Randomisation code and allocation concealment were performed by the pharmacy providing the study medication, using a computer-generated code. The identical medication packs were labelled with the randomisation number and received at the IVF centres from the pharmacy in blocks of 15, five of each of the three treatments, to secure equal distribution of treatment arms at the centres. The randomisation number was continuous and unique for each patient, and it was pre-labelled from the pharmacy before distribution to the clinics; thus, both patients and study personnel were blinded to the intervention. The pharmacy did not play any role in or had knowledge about the IVF treatment. The first person to investigate the unblinded dataset was an external statistician at Aarhus University, Denmark who analysed the reproductive outcome. After that, data was unblinded for the principal investigators.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was clinical pregnancy rate, defined as an ultrasound-proven intrauterine fetal heartbeat at gestational week 7–9. Secondary outcomes were live birth rate, biochemical pregnancy rate (hCG positive 9–11 days after embryo transfer according to local laboratory standards), implantation rate, pregnancy loss, preterm birth rate, birth weight and adverse events. Considering adverse events, we recorded all adverse events reported to the clinics from the day of randomisation to the day of embryo transfer, including an adverse event questionnaire on the day of embryo transfer. Patients without embryo transfer were approached to also fill in the questionnaire.

Compliance to medication was defined as those patients reporting to take all study medicine including those patients who took all study medicine, but inadvertently in a wrong way. Outcomes were analysed by ITT, modified intention to treat (mITT) and per protocol (PP). ITT included all randomised patients except those withdrawn from the study within 24 h from randomisation. For the mITT analysis, additionally, patients needed to fulfil in/exclusion criteria and to have embryo transfer less than 63 days from the active treatment start to cycle day 1 in the same menstrual cycle in which the embryo transfer was performed. For the PP analysis, additionally, all patients should adhere strictly to the protocol. Two authors (TH and MBJ) stratified patients for the mITT and PP analysis independently prior to breaking the randomization code.

Sample size

We estimated a 40% chance for clinical pregnancy per embryo transfer in the active treatment arm as compared to the placebo arm which was estimated to have a maximum of 20% chance of clinical pregnancy per embryo transfer. These estimates were based on a pilot study in which we observed a clinical pregnancy rate per embryo transfer of 9% (2/22) in the AVM group versus 44% (27/62) in the normal group16. By a two-sample proportion test with a power of 80% and an alpha at 5%, the aim was to randomise 92 patients in each group. A potential difference between the two active arms was considered exploratory and consequently, this was not part of the power calculation, but we decided to include the same number of patients in the CLLA arm to investigate a potential added benefit of LACTIN-V. An interim analysis was performed, and to adjust for this, we added 10% more patients to the 92 randomised patients as suggested in Wittes et al.35. We estimated that 10% of couples would have no embryos for transfer after randomisation in fresh cycles, and we adjusted for this by adding another 10% to each randomised group, that is, 92 + 19 = 111. The Interim analysis was pre-planned and conducted at the time when 167 patients were randomised. At this point and under the conditions described previously19, the study board decided to continue the trial on March 12th, 2020.

Statistics

For each treatment group CLLA, CLPL and PLPL the estimated proportions, risk ratios (RR) and their confidence intervals were calculated using uni- and multivariate logistic regression analyses by generalized linear models with log-link function. The significance level for the final analysis was set at 4.9% (95.1% confidence intervals) due to the preplanned interim analysis where an alpha of 0.1% was used. The outcomes were analysed with and without adjusting for the following confounders: quality of the embryo (blastocyst/cleavage state –preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy was not performed in this study) and female age (continuous variable) which are well-described parameters affecting pregnancy rates. It was also pre-planned to adjust for double embryo transfer and for private/public clinics, however, only five patients received double embryo transfer without achieving clinical pregnancy. Furthermore, only 10 patients were included from the one participating private IVF clinic of whom only one patient had a clinical pregnancy. These numbers were not sufficient to adjust for double embryo transfer and private/public centres in the statistical model. We pre-planned to adjust for the abovementioned confounders since the primary analysis (mITT) was not performed per randomised patient but per transferred patient. The linear relation between the log of odds and age was evaluated using splines. To examine the sensitivity of the estimates, all the outcomes were further analysed under PP and ITT conditions. In Tables 1 and 3, we used Fisher’s exact test for binary variables, whereas the ANOVA was used for the continuous variables. We decided to provide a statistical test in Table 1 because all patients randomised did not necessarily have an embryo transfer and as such were not eligible for mITT analysis. Safety analysis (Table 3) was done per ITT. All these analyses were performed in STATA version 18 (StataCorp LLC).

Laboratory methods

After arrival of the vaginal eSwab specimen at the central laboratory at Statens Serum Institute (SSI), DNA from 100 µL of the vaginal screening sample was released boiling in 300 µL Chelex resin slurry as previously described36. Quantitative (q)PCRs detecting Gardnerella spp. (previously described as G. vaginalis) and Fannyhessea (F.) vaginae (previously Atopobium vaginae) were performed as previously described37. A vaginal sample was considered positive if having more than 5.7 × 107 and/or 5.7 × 106 copies/ml for Gardnerella spp. and F. vaginae, respectively. DNA extraction of vaginal samples for microbiota analysis was performed on a MagNAPure instrument (Roche Molecular Systems Inc., Pleasanton, CA, USA), using off-board enzymatic lysis by mixing 100 µL of sample with 150 µL MagNAPure bacterial lysis buffer with final concentrations of lysozyme (20 mg/mL), mutanolysin (250 U/mL) and lysostaphin (22 U/mL) (Merck Life Sciences, Søborg, Denmark) for 60 min at 37 °C. A total of 200 µl was extracted, using the Pathogen Universal 200 MagNA Pure protocol and eluted in 100 µl. The quality of the DNA extraction process was documented by simultaneous extraction of a vaginal mock community (ATCC® MSA-2007™, LGC Standards, Teddington, UK). After dissolving the bacteria according to the manufacturer’s instructions, the pellet of the vaginal mock community was re-suspended in 1 mL PBS and 10 µL was added to 100 µL ESwab® (Copan) transport medium. Negative controls for H2O were analysed on the same plates as the samples. Primers for 16S qPCR and amplification for 16S Illumina sequencing were the same as used by Fredricks et al. (Table S5) and have previously been published38.

For the sequencing, adapters and spacers added to the primer sequences, see Table S6. Amplification of the 16S Illumina sequencing, Kapa HiFi HotStart polymerase ready mix (Sigma-Aldrich) was used with the primer sequences described above, but with adaptors with heterogeneity spacers for MiSeq indexing and sequencing as described in Table S4. The indexing PCR was carried out using 2× KAPA HiFi, Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit v2 for indexing (384 combinations) (Illumina) and with 2 μL amplicon from the primary PCR in a final volume of 25 μL on a 2720 Thermal Cycler using the following conditions: 3 min at 95 °C, 15 cycles of 20 s at 98 °C, 15 s at 55 °C and 45 s at 72 °C, and final 5 min elongation step at 72 °C. After indexing, post-PCR cleanup was performed using a 1:1 ratio of AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter) following manufacturer’s instructions before quantification using AccuClear Ultra High Sensitivity dsDNA Quantification Kit (Biotium) following manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, samples were pooled in equimolar concentrations and quantified using the Qubit dsDNA HS assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) prior to sequencing on a MiSeq with a 600-cycle MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (Illumina) (with 20% phiX spike-in) and a pool of libraries loaded at 10 pM final concentrations.

Bioinformatics pipeline

Raw reads were demultiplexed using bcl2fastq (RRID:SCR_015058). Primers and heterogeneity spacers were trimmed using cutadapt (v. 2.3) in paired-end mode at an 8% error rate39. Subsequent sequence analysis was performed in Rstudio (v. 2022.07.0; R Core Team (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/.) with R version 4.2.1. Decontamination was done using the Decontam package (v. 1.18.0) using method “either” with frequency threshold = 0.1 and prevalence threshold = 0.5. Amplicon Sequence Variants were called using the dada2 pipeline (v. 1.26.0) using the function “filterAndTrim” with following parameters: truncLen = (270, 210), maxEE = 2, truncQ = 2, maxN = 040. CST were subsequently computed according to the publication by France et al.5.

Data handling

Study data was collected and managed, using REDCap electronic data capture tools41 hosted at Aarhus University and monitored by the University affiliated ICH-GCP unit. The randomization code was broken April 21, 2023, when the primary outcome was monitored, and patients had been stratified to ITT, mITT or PP analysis.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Meta-data for the results of the present manuscript is available from the tables. As per Danish and European law (GDPR) we are not allowed to share individual participant data without a data sharing agreement with the interested party. Researchers interested in pseudonymized individual participant data may contact the first or last author to access the data under a data-sharing agreement as decided by the Danish Data Protection Agency, https://www.datatilsynet.dk/english. The raw 16S sequences can be found on European Nucleotide Archive with accession number PRJEB89463. The timeframe to access data is approximately 3 months. The duration of access depends on the data-sharing agreement. The statistical code can be shared with the data. The full study protocol with statistical analysis plan is uploaded with this manuscript, albeit it has to a great extent already been published19. The metadata and statistical analysis log were available to reviewers. This trial conforms to the CONSORT 2010 guidelines and a completed CONSORT checklist is uploaded together with the trial protocol.

References

Wiesenfeld, H. C. et al. Lower genital tract infection and endometritis: insight into subclinical pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet. Gynecol. 100, 456–463 (2002).

Martin, H. L. et al. Vaginal lactobacilli, microbial flora, and risk of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and sexually transmitted disease acquisition. J. Infect. Dis. 180, 1863–1868 (1999).

Cherpes, T. L., Meyn, L. A., Krohn, M. A., Lurie, J. G. & Hillier, S. L. Association between acquisition of herpes simplex virus type 2 in women and bacterial vaginosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37, 319–325 (2003).

Fu, J. & Zhang, H. Meta-analysis of the correlation between vaginal microenvironment and HPV infection. Am. J. Transl. Res. 15, 630–640 (2023).

France, M. T. et al. VALENCIA: a nearest centroid classification method for vaginal microbial communities based on composition. Microbiome 8, 166 (2020).

Oerlemans, E. F. M. et al. The Dwindling microbiota of aerobic vaginitis, an inflammatory state enriched in pathobionts with limited TLR stimulation. Diagnostics (Basel) 10, 879 (2020).

Maksimovic Celicanin, M., Haahr, T., Humaidan, P. & Skafte-Holm, A. Vaginal dysbiosis - the association with reproductive outcomes in IVF patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. https://doi.org/10.1097/GCO.0000000000000953 (2024).

Mitchell, C. M. et al. Colonization of the upper genital tract by vaginal bacterial species in nonpregnant women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 212, 611.e1–611.e9 (2015).

Swidsinski, A. et al. Presence of a polymicrobial endometrial biofilm in patients with bacterial vaginosis. PLoS ONE 8, e53997 (2013).

Liu, Y. et al. Endometrial microbiota in infertile women with and without chronic endometritis as diagnosed using a quantitative and reference range-based method. Fertil. Steril. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.05.015 (2019).

Moreno, I. et al. The diagnosis of chronic endometritis in infertile asymptomatic women: a comparative study of histology, microbial cultures, hysteroscopy, and molecular microbiology. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 218, 602.e1–602.e16 (2018).

Bui, B. N. et al. The endometrial microbiota of women with or without a live birth within 12 months after a first failed IVF/ICSI cycle. Sci. Rep. 13, 3444 (2023).

Moreno, I. et al. Endometrial microbiota composition is associated with reproductive outcome in infertile patients. Microbiome 10, 1 (2022).

Grewal, K. et al. Chromosomally normal miscarriage is associated with vaginal dysbiosis and local inflammation. BMC Med. 20, 38 (2022).

Vitagliano, A., Paffoni, A. & Viganò, P. Does maternal age affect Assisted Reproduction Technology success rates after euploid embryo transfer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil. Steril. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2023.02.036 (2023).

Haahr, T. et al. Abnormal vaginal microbiota may be associated with poor reproductive outcomes: a prospective study in IVF patients. Hum. Reprod. 31, 795–803 (2016).

Petrina, M. A. B., Cosentino, L. A., Wiesenfeld, H. C., Darville, T. & Hillier, S. L. Susceptibility of endometrial isolates recovered from women with clinical pelvic inflammatory disease or histological endometritis to antimicrobial agents. Anaerobe 56, 61–65 (2019).

Cohen, C. R. et al. Randomized trial of lactin-V to prevent recurrence of Bacterial vaginosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1906–1915 (2020).

Haahr, T. et al. Effect of clindamycin and a live biotherapeutic on the reproductive outcomes of IVF patients with abnormal vaginal microbiota: protocol for a double-blind, placebo-controlled multicentre trial. BMJ Open 10, e035866 (2020).

Leitich, H. & Kiss, H. Asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis and intermediate flora as risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcome. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 21, 375–390 (2007).

Subtil, D. et al. Early clindamycin for bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy (PREMEVA): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 392, 2171–2179 (2018).

Haahr, T. et al. Treatment of bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy in order to reduce the risk of spontaneous preterm delivery - a clinical recommendation. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.12933 (2016).

US Preventive Services Task Force. et al. Screening for Bacterial vaginosis in pregnant persons to prevent preterm delivery: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 323, 1286–1292 (2020).

Zhang, Q.-Q. et al. Prebiotic maltose gel can promote the vaginal microbiota from BV-related bacteria dominant to lactobacillus in rhesus macaque. Front. Microbiol. 11, 594065 (2020).

Ameratunga, D., Yazdani, A. & Kroon, B. Antibiotics prior to or at the time of embryo transfer in ART. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008995.pub3 (2023).

Eldivan, Ö. et al. Does screening for vaginal infection have an impact on pregnancy rates in intracytoplasmic sperm injection cycles? Turk. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 13, 11–15 (2016).

Haahr, T. et al. The genital tract microbiota of IVF patients and oocyte donors: a comparative analysis. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.10.18.619104 (2024).

Iwami, N. et al. Therapeutic intervention based on gene sequencing analysis of microbial 16S ribosomal RNA of the intrauterine microbiome improves pregnancy outcomes in IVF patients: a prospective cohort study. J. Assist Reprod. Genet. 40, 125–135 (2023).

Sakamoto, M. et al. The efficacy of vaginal treatment for non-Lactobacillus dominant endometrial microbiota—A case–control study. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 50, 604–610 (2024).

Elder, M. G., Bywater, M. J. & Reeves, D. S. Pelvic tissue and serum concentrations of various antibiotics given as pre-operative medication. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 84, 887–893 (1977).

Defining Vaginal Community Dynamics: daily microbiome transitions, the role of menstruation, bacteriophages and bacterial genes. https://www.researchsquare.comhttps://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3028342/v1 (2023).

Haahr, T. et al. Vaginal microbiota and IVF outcomes: development of a simple diagnostic tool to predict patients at risk of a poor reproductive outcome. J. Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiy744 (2018).

Srinivasan, S. et al. Temporal variability of human vaginal bacteria and relationship with bacterial vaginosis. PLoS ONE 5, e10197 (2010).

Forney, L. J. et al. Comparison of self-collected and physician-collected vaginal swabs for microbiome analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48, 1741–1748 (2010).

Wittes, J. Sample size calculations for randomized controlled trials. Epidemiol. Rev. 24, 39–53 (2002).

Jensen, J. S., Björnelius, E., Dohn, B. & Lidbrink, P. Use of TaqMan 5’ nuclease real-time PCR for quantitative detection of Mycoplasma genitalium DNA in males with and without urethritis who were attendees at a sexually transmitted disease clinic. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42, 683–692 (2004).

Datcu, R. et al. Vaginal microbiome in women from Greenland assessed by microscopy and quantitative PCR. BMC Infect. Dis. 13, 480-2334–13–480 (2013).

Golob, J. L. et al. Stool microbiota at neutrophil recovery is predictive for severe acute graft vs host disease after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Clin. Infect. Dis. 65, 1984–1991 (2017).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. 17, 10–12 (2011).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581–583 (2016).

Harris, P. A. et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inf. 42, 377–381 (2009).

Acknowledgements

P.H., T.H. and J.S.J. received—through their institutions—an unrestricted research grant from Osel, Inc., which produces LACTIN-V. A clinical trial agreement was made ensuring full data ownership and publication rights to P.H. Osel Inc. had inputs to study design but no role in data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the present manuscript. In addition to the unrestricted research grant from Osel, Inc. previously mentioned, other granters were Axel Muusfeldts Foundation grant number 2018-1311 to T.H., A.P. Møller Foundation for Medical Research grant number 18-L-0173 to T.H., Central Denmark Region Hospital MIDT Foundation grant number 421506 to T.H., and a PhD scholarship from Aarhus University, Denmark to T.H. We are grateful to the patients participating in this study as well as the many health/research professionals helping this trial to be completed. Research nurses at the respective clinics as well as laboratory technicians at Statens Serum institute should be commended for their work. We acknowledge Osel Inc. and Tom Parks especially for the collaboration on this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.H. wrote the first draft and made statistical analysis. N.l.C.F. was part of conceptualisation, patient recruitment, project administration, results interpretation and review and editing. A.P. was part of patient recruitment, project administration, results interpretation and review and editing. M.B.J. was part of conceptualisation, patient recruitment, project administration, results interpretation and review and editing. H.O.E. was part of conceptualisation, patient recruitment, project administration, results interpretation and review and editing. B.A. was part of conceptualisation, patient recruitment, project administration, results interpretation and review and editing. R.L. was part of conceptualisation, patient recruitment, project administration, results interpretation and review and editing. L.P. was part of patient recruitment, project administration, results interpretation and review and editing. H.S.N. was part of conceptualisation, patient recruitment, project administration, results interpretation and review and editing. V.H. was part of conceptualisation, patient recruitment, project administration, results interpretation and review and editing. T.R.P. was part of project administration, data curation and review and editing. A.S.H. was part of literature search and review and editing. J.S.J. was part of conceptualisation, methodology, supervision, project administration, data curation, funding acquisition, results interpretation and review and editing. P.H. was part of conceptualisation, methodology, supervision, project administration, data curation, funding acquisition, results interpretation and review and editing. All authors had access to the study data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. P.H. and T.H. directly accessed and verified the underlying data reported in the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.S.J., P.H. and T.H. are listed as inventors in an international patent application (PCT/US2018/040882), involving the therapeutic use of vaginal lactobacilli to improve IVF outcomes. T.H. received honoraria for lectures from Gedeon Richter and Merck. P.H. received unrestricted research grants outside this study from Merck, IBSA and Gedeon Richter as well as honoraria for lectures from MSD, Merck, Gedeon-Richter, and Theramex. J.S.J. received grants, speaker’s fee, and non-financial support from Hologic, speaker’s fees from LeoPharma and grants from Nabriva, all outside the submitted work and serves on the scientific advisory board of Roche Molecular Systems, Abbott Molecular and Cepheid. N.L.C.F. received unrestricted research grant from Gedeon Richter and honoraria for lectures from Merck. H.S.N. received through her institution research grant from Ferring and Freya Biosciences and honoraria for lectures from Merck, IBSA, Gedeon Richter, Novo Nordisk, Cook medical and Ferring. The remaining authors declare no competing interests related to this manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Haahr, T., Freiesleben, N.l.C., Jensen, M.B. et al. Efficacy of clindamycin and LACTIN-V for in vitro fertilization patients with vaginal dysbiosis: a randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled multicentre trial. Nat Commun 16, 5166 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60205-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60205-6

This article is cited by

-

From gut to gamete: how the microbiome influences fertility and preconception health

Microbiome (2025)

-

The uterine and vaginal microbiome in assisted reproductive technologies: implications for maternal and offspring outcomes

Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics (2025)