Abstract

Shell coating is known to suppress luminescence quenching in spherical upconversion nanoparticles. However, the emergence of anisotropic nanoparticles with facet-selective, directional growth complicates the coating process, and the use of traditional active, inert, or polymer coatings on such structures remains largely unexplored. Here, we synthesize a series of nanorods with designed geometries, enabling quantitative spectral analysis at the single-particle level. We observe that directional growth of inert or active shells at the rod tips enhances emission relative to the parent core, with their relative effectiveness governed by power density and shell thickness. Ligand presence—polymer or oleate—quenches upconversion relative to bare nanorods. Although local heating is observed at the single-particle level, it does not affect spectroscopic observations, ligand stability, or data reproducibility. Our findings reveal how directionally grown shells influence the optical properties of upconversion nanorods, providing essential insights for their future applications in bioimaging, sensing, and photonics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coating strategies have been extensively developed to address surface issues of nanoparticles, such as luminescence quenching1, poor aqueous stability2, and undesirable interactions with biological systems3. Upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs), a type of inorganic nanoparticles doped with lanthanide ions, exhibit unique optical properties by converting low-energy infrared light into higher-energy visible light. This distinctive feature makes UCNPs particularly valuable for applications such as bioimaging4, sensing5, and photodynamic therapy6. However, UCNPs are highly susceptible to surface quenching, where the presence of quenching agents or surface defects significantly reduces their luminescence efficiency. To overcome these challenges, various coating strategies have been explored7.

A commonly recognized and effective inert shell coating strategy involves the epitaxial growth of a layer of host crystal, such as NaYF4 or CaF2, around the core UCNPs8,9. This method creates a highly efficient barrier against quenching by preventing interactions between lanthanide ions and surface quenchers, which often originate from the vibrations of ligands10. A shell thickness of ≈4 nm is generally considered sufficient to strongly reduce surface-ligand quenching11. Active shell coatings, on the other hand, utilize functional materials that not only protect the UCNPs but also enhance their luminescence through energy transfer mechanisms12,13,14. Techniques such as doping the shell with specific ions like ytterbium and erbium can facilitate efficient energy transfer and reduce surface-related quenching, leading to improved upconversion efficiency15,16,17. To address quenching agents from the particle suspension environment, such as water molecules, and to make the nanoparticles aqueously stable and biocompatible, polymer coatings present an attractive solution18. These coatings introduce exogenous stability to biological samples, enhancing the compatibility and functionality of nanoparticles in aqueous environments19,20,21.

All the above strategies have been widely explored on spherical UCNPs, where coating a new layer homogeneously on the core structure is relatively straightforward. However, the effectiveness of these coating strategies on emerging types of UCNPs, such as directionally grown nanoparticles like nanorods, remains largely unknown. Recently, significant progress has been made in the controlled directional growth of UCNPs, enabling the precise formation of a series of elongated nanorods with or without an increase in their diameters, as desired22,23,24. This success is attributed to the highly anisotropic crystallinity and suitable lattice mismatch of hexagonal UCNPs (e.g., NaLnF4, Ln stands for lanthanides including Y, Gd, and others)25,26. These advancements have opened new possibilities for UCNPs in various fields including sensing27, super-resolution imaging24, intracellular imaging and tracking23,28, nanothermometry29, and self-assembly30,31, leveraging their structural and optical properties.

In this work, we study the effects of inert shell, active shell, and polymer coatings in conjunction with the directionally grown structures of UCNPs. The removal of the native oleic acid layer from the surface of as-synthesized UCNPs is a common method used to create a bare surface. This approach appears to be an effective alternative for forming a hydrophilic surface without introducing surface quenchers. We leverage single nanoparticle spectroscopy, specifically by measuring the power-dependent upconversion emission spectra of single UCNPs, to quantitatively analyze the impact of these coatings on their brightness. Beyond coating types, we also examine whether factors such as laser-induced self-heating and ambient moisture during measurement influence the observations. Our series of upconversion nanorods are composed of the widely popular host hexagonal NaYF4, doped with high concentration of sensitizers and emitters, i.e., 40 mol% of Yb3+ and 4 mol% of Er3+. These nanorods produce sufficient photon counts under a confocal microscope, allowing for spectroscopic measurements with the excitation power density tunable from approximately 7 × 104 to 3 × 107 W cm−2.

Results

Design and morphology of nanorods

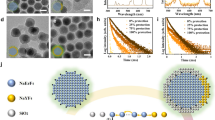

To ensure the consistency and comparability of our single-particle measurements, all samples analyzed in this study originate from the same parent core rods (CR), as shown in the TEM image in Supplementary Fig. 1. This section presents the structural characteristics of the anisotropic core-shell nanoparticles, including active-grown shells (AR1−3) and inert-grown shells (IR1−3), which serve as the fundamental platform for all subsequent investigations, including soft coating modifications. The active shell refers to a shell compositionally identical to the core (NaYF4: 40Yb3+4Er3+), enabling a seamless epitaxial interface, whereas the inert shell consists of a chemically distinct, optically inactive material (NaYF4). Figure 1a provides a schematic illustration of the synthesis strategy, highlighting the oriented epitaxial growth along the c-axis that yields ARi and IRi with identical size and morphology. Such oriented epitaxial growth occurs by appropriately adjusting the injection speed and the source of material during synthesis to grow shells predominantly at the two ends of the rods (see details in “Methods”). The accompanying TEM images and size distribution analysis (Fig. 1b−e) confirm the uniform dimensions of each sample and the identical growth lengths along the c-axis of the crystal between each pair in the AR and IR series. Specifically, the AR1−IR1, AR2−IR2, and AR3−AR3 pairs have shell thicknesses of 5, 8, and 14 nm, respectively, at the two tip-ends of the nanorods grown on CR, while the diameters of all samples remain constant at ≈38 nm.

a Schematic diagram illustrating the routes of directional growth of active shell or inert shell onto CR (Core Rod) sample. b−e TEM images and size distributions displaying the morphology after directional coating of active and inert shell. D refers to diameter, and L refers to length. Scalebar: 100 nm. For (c) and (e) the indicated error represents the standard deviation (SD) from 100 independent nanoparticle measurements. Colors in the Figure differentiate sample groups according to their surface coatings: yellow tones correspond to nanoparticles coated with active shells, and gray tones correspond to nanoparticles coated with inert shells. Different shades within each group reflect individual sample batches. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Directional shell coating for power-dependent core protection

To examine whether directional shell coating can mitigate quenching in the core rod and to understand how the directional growth of an active shell versus an inert shell influences protective behavior, we measured all as-synthesized samples at the single-nanoparticle level by drop-casting each onto a cover glass. By statistically analyzing the emission spectra (Supplementary Figs. 2−4) of ≈20 single nanoparticles per sample, we present the averaged integral intensity evolution trends for the three pairs in Fig. 2a and the enhancement factors relative to the CR as a function of power density in Fig. 2b. It is evident that directional coating on the two tip-ends provides substantial enhancement to the CR, with the enhancement effect varying in a power-dependent and size-dependent manner. At low power densities (≤3 × 105 W cm−2), IR1 exhibits greater enhancement than AR1. However, at higher power densities, this trend reverses, with AR1 outperforming IR1. A similar “crossover” behavior is observed for the IR2−AR2 pair at a lower threshold of ≈7 × 104 W cm−2, while for the IR3–AR3 pair, it occurs at an even lower power density, beyond the range of our testing conditions. This is because, regardless of the inert shell thickness, the enhancement factors tend to saturate across the entire power range. In contrast, the enhancement effect of the active coating becomes more pronounced with increasing power density and greater shell thickness. The key distinction between these two coatings is that the active coating contains more dopants, which can be excited once the excitation power is sufficiently high, leading to significantly greater enhancement. However, at low power densities, these additional dopants cannot fully contribute to the enhancement. This aligns with our observations in colloidal measurements, where the power density is low (1 W cm−2), and the lifetimes of the AR series are consistently shorter than those of the corresponding IR series (Supplementary Fig. 5).

a Single particle upconversion emission intensity evolution with increased excitation power density from 7 × 104 to 3 × 107 W cm−2. b Power-dependent enhancement factors of total upconversion intensity, comparing directional growth of active or inert shells to the core sample CR. c Power-dependent upconversion enhancement factors for each peak, investigating the enhancement origin of AR3@OA sample. Error bars represent the SD calculated from measurements of 20 individual nanoparticles for each sample. Colors in panels (a, b) differentiate the sample groups: yellow shades correspond to AR samples, gray shades to IR samples, and light yellow to CR. In (c), colors indicate emission wavelengths: cyan for 504 nm, dark green for 541 nm, light green for 557 nm, and red for 654 nm. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Since AR3 shows the largest difference in enhancement factor compared with its inert counterpart, we further investigated the distribution of enhancement factors for each major emission peak (Fig. 2c), including 504 nm (4G11/2 → 4I13/2), 541 nm (4S3/2 → 4I15/2), 557 nm (2H9/2 → 4I13/2), and 654 nm (4F9/2 → 4I15/2). Our analysis reveals that the coating-induced enhancement is more pronounced for the 541 and 557 nm emissions compared to the 504 and 654 nm emissions. This is because the original quenching in the CR sample is supposed to be more pronounced for the 541 and 557 nm emissions due to their high chance of cross-relaxation processes between Er3+ and Yb3+ ions, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 6. Note that the enhancement of the 504 nm emission as a function of power density exhibits a much steeper slope compared to other peaks. This difference stems from variations in the order of nonlinearity associated with the photon population processes: the population of the 4G11/2 state involves three- to four-photon processes, whereas the other excited states primarily involve two- to three-photon processes32.

The limited effectiveness of the directional inert shell in enhancing emission raises the question of whether a fully encapsulating inert shell, which passivates all surfaces rather than only the c-axis, could more effectively suppress surface quenching. We further synthesized fully inert-coated rods (IR4) and compared their single-particle emission intensities at 504, 541, 557, and 654 nm with those of CR and IR1−3 (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8). According to the results, none of the peaks from IR4 exhibited the strongest intensities; in fact, the 504 nm peak intensities were even weaker than those of the core rod, contrary to our expectations. This may be attributed to the excessively thick shell in IR4, which increase the nanoparticle size and result in non-negligible Rayleigh scattering and the light absorption of the shell, leading to energy loss during both excitation and emission processes. Similar observations have been reported in single nanoparticle imaging and powder-state spectroscopy studies, where too thick shells lead to decreased upconversion emission intensities33,34.

Polymer coating induces ligand quenching

Our group has long investigated stable surfaces of UCNPs for aqueous environments with potential bio-targeting capabilities, and we have developed a reversible addition fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymer coating strategy35,36. As illustrated in Fig. 3a, we employed this RAFT polymer (see chemical structures in Supplementary Fig. 9) to perform ligand exchange on UCNPs, ensuring the nanoparticles exhibit great mono-dispersity in water, as shown in the TEM in Supplementary Fig. 10. Their hydrodynamic size is uniformly distributed without aggregation, as revealed by the DLS in Fig. 3b. In Fig. 3c, the FTIR spectra show the presence of a phosphate group (PO43−) peak around 1050 cm−1 in all the polymer-coated samples. This, along with the Zeta potential data, as shown in Fig. 3d, confirms the coating of the polymers. The negative surface charges, originating from the COOH− groups in the polymer, contribute to the aqueous stability.

a Schematic diagram illustrating the routes of surface modification processed. b DLS characterization of polymer-coated samples. c FTIR spectra of AR1 with different surface conditions. FTIR of AR2, AR3 and IR samples after surface modification are shown in Supplementary Fig. 9. d DLS Zeta potential characterization of polymer-coated samples. Error bar represents the SD from 3 independent measurements. e Single particle upconversion emission intensity evolution comparison of the samples before and after surface modification. Error bar represents the SD calculated from measurements of 20 individual nanoparticles for each sample. In (b), (d), and (e), the light, medium, and dark yellow correspond to AR1–3, respectively. In panel (c), the light, medium, and dark yellow correspond to AR1 sample with polymer, bare, and OA surfaces, respectively. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

As additional surface always exhibits some degree of quenching effect, we also aimed to understand how strong the quenching could be with the native oleate OA− surface compared with a bare surface. To examine this, we utilized the common method of hydrochloric acid (HCl) wash to remove the surface OA− ligands (Fig. 3a; see “Methods”) and formed the bare nanorods. According to the FTIR analysis (Fig. 3c), the absence of the carboxyl group (COO−) peak around 1560 cm−1 in the bare samples confirms the successful removal of OA− ligands. TEM images taken before and after the surface treatment demonstrate the preservation of epigenetic integrity and mono-dispersity (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Among the comparison of these three sets of AR nanorods (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12), we found that those with a bare surface consistently exhibit the highest intensity compared to ligand-capped counterparts, with the difference becoming more pronounced at higher power densities. On the contrary, polymer coating induces more severe quenching than OA capping. It is well known that OA ligands act as non-radiative depopulation quenchers. A similar result was observed in a nanowire system, where the single particle upconversion of ligand-free nanowires was much higher than that of the as-synthesized ones37. Based on the chemical structures, the polymer contains a larger quantity of chemical bonds than OA (such as O−H, C−H, etc.), which contributes to stronger non-radiative quenching and weaker upconversion intensity. This phenomenon is similar to what has been observed in spherical UCNPs20. However, it is significant to note the strong surface-to-volume ratio dependency of the quenching effect from the polymer coating. The integral upconversion intensity of the smallest rod, AR1, declines most severely, with less than 50% remaining after ligand exchange by replacing OA with polymer (Supplementary Fig. 11, Supplementary Table 1). However, this decline alleviates with larger sizes.

These observations are also evident in the IR samples, indicating that the influence of surface ligands on single-particle emission is not exclusive to AR samples (Supplementary Figs. 9, 13−16, Supplementary Table 2). The consistent trend—higher emission from IRi bare samples, followed by IRi@OA, with IRi@polymer exhibiting the weakest emission—suggests that surface quenching cannot be fully inhibited, even when an inert shell is present. This can be attributed to the fact that the directional inert shell does not fully encapsulate the nanoparticle, leaving certain surfaces still susceptible to quenching effects.

Discussions on testing conditions

Thermal quenching has always been a significant factor affecting upconversion luminescence. Although our testing process did not involve an external heating stage, there could be self-heating phenomena in the samples during the measurement, especially under high-power excitation38. The estimated temperatures at corresponding power densities can be calculated based on the Boltzmann distribution of the Er3+ energy levels (2H11/2 and 4S3/2)39, assuming that the low power range without self-heating corresponds to room temperature (25 °C). When calculating temperature, the emission band at 557 nm is likely to cause erroneous thermal readings, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 17. This emission corresponds to the transition from the 2H9/2 energy level, which is not relevant to the thermally coupled energy levels. Therefore, we used Band 1 and Band 2 as the thermally coupled bands for precise temperature calculations, as shown in Fig. 4a. According to the natural logarithm of the intensity ratio ln (IBand 1/IBand 2) and the calculated power-dependent temperature curve of AR3 samples (Supplementary Fig. 18e and Fig. 4b), we found that as the power density increases to 107 W cm−2, the self-heating temperature exceeds 100 °C, with the OA-coated surface exhibiting the highest temperatures, followed by the polymer-coated surface, and finally the bare samples, which show the lowest temperature increase. Those phenomena were also observed in AR1−2 and IR1−3 samples, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 18 and 19. As shown in Fig. 2, the presence of quenching suggests that a portion of the absorbed energy undergoes energy transfer but is lost as heat rather than being emitted as luminescence. Moreover, the C–H bonds in surface ligands can directly absorb 976.5 nm laser light, as the overtones of C–H stretching vibrations match the laser wavelength. Consequently, samples with ligand coatings are expected to generate more local heating than those with bare surfaces. The thermal contact of samples with the substrate may also affect their steady-state temperature. The thermal conductivity of common ligands (e.g., ≈0.17 W m−1 K−1) for oleic acid) is much lower than that of glass (≈1 W m−1 K−1). This creates a thermal resistance barrier at the nanoparticle-ligand-glass interface, slowing heat transfer from the particle to the substrate. Consequently, bare nanoparticles (directly contacting glass) dissipate heat faster, while ligand-coated particles exhibit higher localized temperatures due to hindered thermal pathways40.

a Selection of emission bands for calculating the temperature of samples based on the Boltzmann distribution formula. The deep pink refers to Band 1 covering 512−535 nm, and the light pink refers to Band 2 covering 535−545 nm. b Temperature results of soft-coated AR3 samples calculated based on the selected emission bands. c Intensity versus laser power curves obtained with both increasing and decreasing power densities for soft-coated AR3 samples. The deep and light pink refers to the heating cycles 1 and 2, respectively; the deep and light blue refers to the cooling cycles 1 and 2, respectively. d Power-dependent single particle intensity of soft-coated AR3 samples without ambient moisture (in vacuum). e Power-dependent enhancement factors of upconversion intensity, comparing vacuum AR3 samples to the corresponding air samples. The error bars in (b, d, e) represent the SD calculated from measurements of 20 individual nanoparticles for each sample. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

The self-heating may raise concerns about the stability of the nanoparticles during high-power excitation, particularly for polymer-coated samples. This, in turn, could affect the reproducibility of data acquisition. To assess the thermal stability of the ligands coated nanorods, we performed two measurement cycles on the same samples, varying the power density in both increasing and decreasing sequences (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Fig. 20). Our results show negligible variation in particle intensity at the same power level, proving the sufficient stability of samples and reproducibility of our experiments. To evaluate potential decomposition of the ligands caused by local heating, we also tested the TGA curves of AR3@polymer and AR3@OA (Supplementary Fig. 21). The TGA results show no significant weight loss below 200 °C, with the polymer beginning to detach from the particle surface around 280 °C, whereas OA exhibits a much higher detachment temperature at 330 °C. The critical decomposition temperatures of polymer and OA are significantly higher than the local heating temperatures, further supporting our high reproducibility of the single-particle spectroscopy under experimental conditions.

The solvent surrounding UCNPs plays a crucial role in quenching effects observed in ensemble measurements. Specifically, the initial state of OA-coated samples is dispersed in cyclohexane, while polymer-coated nanorods are dispersed in water. This difference is significant in colloidal ensemble spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 22) but diminished in single particle spectroscopy. Since the single nanoparticle samples were prepared by drop-casting diluted colloidal samples onto a cover glass, followed by air drying and sealing, the solvents in the colloidal samples are expected to evaporate. However, residual moisture from the ambient air or solvents may still be present on the dried nanoparticles. To assess the impact of this residual moisture, we dried the samples under vacuum and compared their optical properties with those of air-dried samples, as shown in Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 23. We consistently observed that the relative intensity among single nanorods with OA surfaces, polymer coatings, and bare surfaces remains unchanged regardless of the drying conditions, although the absolute intensity of nanorods dried under vacuum is slightly higher than those in air (Fig. 4e, Supplementary Table 3). Furthermore, the hydrophobic OA-coated surface exhibits relatively smaller intensity enhancement compared to the hydrophilic surfaces (polymer and bare), which indicates that the moisture absorbed in hydrophilic surfaces may primarily originate from the original solvent.

Discussion

We have studied the effects of surface coating on the directionally grown UCNPs. Based on single-particle analysis of a series of nanorods, we found that directional growth at the two tip-ends enhances emission compared to the parent core rod. The superior protective effect of directionally grown shells, whether active or inert, is both power- and size-dependent, leading to a “crossover” in their power-dependent enhancement factor curves at a certain threshold. Surface ligands, rather than the solvents of colloidal nanoparticles, are proven as the major quencher in single nanoparticle spectroscopy. Although soft coatings like polymers are an effective modification strategy for enhancing the aqueous stability of UCNPs, they significantly quench upconversion at the single nanoparticle level, even more severely than the OA surface. The extent of polymer-induced surface quenching decreases with increasing shell thickness on directionally grown rods, regardless of whether the shell is active or inert, even though their side facets remain in direct contact with quenchers. Although significant self-heating is observed in single nanoparticle spectroscopy, it does not impact the above-mentioned observations or compromise the thermal stability of the organic ligand coating. These insights highlight key considerations for optimizing the performance of directionally grown upconversion nanorods in various applications.

Methods

Materials

YCl3·6H2O (99.99%), ErCl3·6H2O (99.99%), YbCl3·6H2O (99.99%), oleic acid (OA, 90%), and 1-octadecene (ODE, 90%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Ammonium fluoride (NH4F, 98%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Tetrahydrofuran (THF, 99.9%) and hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 97%), cyclohexane (HPLC), methanol (99.9%), and ethanol (99.5%) were purchased from ChemSupply. The di-block copolymer (POEGMEA-b-PMAEP) was synthesized using RAFT polymerization as reported in ref. 36.

Synthesis of core nanoparticles

The synthesis of NaYF4:40%Yb, 4%Er core nanoparticles was conducted using a co-precipitation method. In a standard procedure, 1 mmol of LnCl3·6H2O (Ln = Y, Yb, Er) with a molar ratio of 56:40:4 was placed in a 50 mL three-neck round-bottom flask containing 6 mL of oleic acid (OA) and 15 mL of 1-octadecene (ODE). The mixture was heated to 170 °C under an inert atmosphere and held at this temperature for 40 min. After this period, the solution was cooled to room temperature (RT) to form a clear and transparent solution. Subsequently, 10.5 mL of a methanol solution containing NaOH (2.5 mmol) and NH4F (4 mmol) was added to the mixture and stirred for 30 min at RT. The temperature was then gradually raised to 80 °C and maintained for 30 min to evaporate the excess methanol until bubbling ceased. Next, the mixture was heated to 110 °C and held for 10 min to remove any residual methanol and water. The temperature was then increased to 300 °C and maintained for 90 min. After cooling to RT, the resulting core nanoparticles were collected and re-dispersed in 5 mL of cyclohexane following several washings with a cyclohexane/ethanol mixture.

Synthesis of core@shell rod nanoparticles

The synthesis of NaYF4:40%Yb, 4%Er nanorods involved the longitudinal growth of a shell precursor onto core nanoparticles using a hot-injection method. The initial step was the preparation of the shell precursor. To achieve this, 1.5 mmol of LnCl3·6H2O (Ln = Y, Yb, Er) with a molar ratio of 56Y:40Yb:4Er (for an active shell) or 100Y (for an inert shell) was introduced into a 50 mL three-neck round-bottom flask containing 6 mL of oleic acid (OA) and 15 mL of 1-octadecene (ODE). This mixture was then heated to 170 °C under an inert gas atmosphere. After maintaining this temperature for 40 min, the solution was allowed to cool to RT, resulting in a clear and transparent solution. Following this, 18.75 mL of a methanol solution containing NaOH (3.75 mmol), NH4F (6 mmol), and KOH (3 mmol) was added. The solution was stirred for 30 min and then heated to 80 °C under inert gas to remove the methanol, continuing until bubbling ceased. Finally, the reaction mixture was cooled to RT, yielding the rod shell precursors.

To achieve the single-dimension growth of nanorods, 0.2 mmol of core nanoparticles were combined with 1 mmol of NaOH, 3.6 mL of oleic acid (OA), and 9.2 mL of 1-octadecene (ODE) in a 50 mL flask. The solution was heated to 170 °C under an inert gas atmosphere for 30 min and then further heated to 310 °C. At this stage, 0.04 mL of rod shell precursors were injected into the reaction mixture, which was kept at 310 °C for 1 min to allow ripening. This injection and ripening process was repeated multiple times to produce nanorods of varying lengths. Finally, the reaction mixture was cooled to RT. The resulting nanorod samples were washed several times with a cyclohexane and ethanol mixture and then dispersed in cyclohexane.

For full-capsulation shell growth of nanorods, after being heated to 310 °C, 0.2 mL of rod shell precursors were injected into the reaction mixture, which was kept at 310 °C for 3 min to allow ripening. Other conditions are identical.

Surface modification for ligand-free nanoparticles

The nanoparticles dispersed in cyclohexane (1 mL, 5 mg) were first precipitated by adding 1 mL ethanol and collected by centrifuging at 20,240 × g for 6 min. After removing the supernatant, 1 mL of HCL (0.2−0.5 M) and 1 mL of ethanol were added, and the mixture was ultrasonicated for 5 min. The resultant nanoparticles in dispersion were centrifuged at 20,240 × g for 40 min to obtain the ligand-free nanoparticles. The nanoparticles were further purified by washing three times in 2.0 mL of ethanol-deionized water solution (1:1 v/v) and re-dispersed in 1 mL of deionized water for further use.

Surface modification (ligand exchange) for polymer-coated nanoparticles

The nanoparticles (5 mg) were first dispersed in 1 mL of THF, followed by adding 5 mg of di-block polymer dispersed in 1 mL of THF. The mixed solution was shaken at room temperature for 12 h. The obtained polymer-coated nanoparticles were centrifuged, followed by washing three times using THF and deionized water (1 mL+0 mL, 0.5 ml+0.5 mL, 0 mL+1 mL, respectively). After the third wash, the supernatant was removed, and the nanoparticles were re-dispersed in 1 mL deionized water for further use.

Characterization

The morphology of the as-synthesized nanoparticles was characterized via transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging (JEOL F200) with an operating voltage of 200 kV. The samples were prepared by dropping a dilute suspension of nanocrystals onto copper grids. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy spectra were obtained on Nicolet IS 50/6700 (Thermofisher). The measurement of DLS (dynamic light scattering) and Zeta potential (ζ) was carried out by Zetasizer (Malvern Panalytical). TGA results were measured from SQ600.

Preparation of sample slides for confocal measurement

Glass coverslips and slides were initially cleaned with ethanol and then air-dried in a fume hood. The nanoparticles were diluted with cyclohexane to a concentration of 0.5 × 10−5 mmol mL−1. Subsequently, 10 μL of the diluted sample was deposited onto the surface of a coverslip. Once the cyclohexane had evaporated in the air, the coverslip was inverted onto the glass slide and sealed in preparation for single particle measurement.

Confocal spectra measurement

An upright confocal optical system was constructed for intensity measurements. A single-mode fiber-coupled polarized 976.5 nm diode laser served as the excitation source and was focused on the sample using an oil-immersion objective lens (UPlanAPO, Olympus; ×100, NA = 1.4). The emission from the sample was collected by the same objective lens and then refocused into an optical fiber with a core size matched to the system’s Airy disk. A single-photon counting avalanche diode (SPAD) detector was connected to the collection optical fiber to measure the emission intensity in counts. Luminescence spectra were acquired using a fiber-coupled spectrometer (Andor) with following parameters: 1200 grooves mm−1 grating, 200 gain; 0.5 s exposure time, and 10 accumulation time. For colloidal lifetime measurement, the laser diode was modulated to produce 2000 μs excitation pulse. The power density of 976.5 nm laser is 1 W cm−2.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Li, F. et al. Size-dependent lanthanide energy transfer amplifies upconversion luminescence quantum yields. Nat. Photonics 18, 440–449 (2024).

Sedlmeier, A. & Gorris, H. H. Surface modification and characterization of photon-upconverting nanoparticles for bioanalytical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 1526–1560 (2015).

Francés-Soriano, L., Estebanez, N., Pérez-Prieto, J. & Hildebrandt, N. DNA-coated upconversion nanoparticles for sensitive nucleic acid FRET biosensing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2201541 (2022).

Di, X. et al. Spatiotemporally mapping temperature dynamics of lysosomes and mitochondria using cascade organelle-targeting upconversion nanoparticles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2207402119 (2022).

Arai, M. S. & de Camargo, A. S. Exploring the use of upconversion nanoparticles in chemical and biological sensors: from surface modifications to point-of-care devices. Nanoscale Adv. 3, 5135–5165 (2021).

Güleryüz, B., Ünal, U. & Gülsoy, M. Near infrared light activated upconversion nanoparticles (UCNP) based photodynamic therapy of prostate cancers: an in vitro study. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 36, 102616 (2021).

Liu, S., Yan, L., Huang, J., Zhang, Q. & Zhou, B. Controlling upconversion in emerging multilayer core-shell nanostructures: from fundamentals to frontier applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 1729–1765 (2022).

Wurth, C., Fischer, S., Grauel, B., Alivisatos, A. P. & Resch-Genger, U. Quantum yields, surface quenching, and passivation efficiency for ultrasmall core/shell upconverting nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 4922–4928 (2018).

Zheng, W. et al. Sub-10 nm lanthanide-doped CaF2 nanoprobes for time-resolved luminescent biodetection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 52, 6671–6676 (2013).

Rabouw, F. T. et al. Quenching Pathways in NaYF4:Er3+,Yb3+ Upconversion Nanocrystals. ACS Nano 12, 4812–4823 (2018).

Pini, F., Frances-Soriano, L. & Peruffo, N. Spatial and temporal resolution of luminescence quenching in small upconversion nanocrystals. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 11883–11894 (2022).

Wang, F. et al. Tuning upconversion through energy migration in core-shell nanoparticles. Nat. Mater. 10, 968–973 (2011).

Zhou, B. et al. Constructing interfacial energy transfer for photon up- and down-conversion from lanthanides in a core-shell nanostructure. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 55, 12356–12360 (2016).

Zhou, B. et al. Probing energy migration through precise control of interfacial energy transfer in nanostructure. Adv. Mater. 31, e1806308 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Enhancement of single upconversion nanoparticle imaging by topologically segregated core-shell structure with inward energy migration. Nat. Commun. 13, 5927 (2022).

Han, S. et al. Lanthanide-doped inorganic nanoparticles turn molecular triplet excitons bright. Nature 587, 594–599 (2020).

Siefe, C. et al. Sub-20 nm core-shell-shell nanoparticles for bright upconversion and enhanced forster resonant energy transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 16997–17005 (2019).

Nahorniak, M. et al. Chemical and colloidal stability of polymer-coated NaYF4: Yb, Er nanoparticles in aqueous media and viability of cells: the effect of a protective coating. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 2724 (2023).

Jin, J. et al. Polymer-coated NaYF4: Yb3+, Er3+ upconversion nanoparticles for charge-dependent cellular imaging. ACS Nano 5, 7838–7847 (2011).

Zhang, L. et al. Optimizing the polymer cloak for upconverting nanoparticles: an evaluation of bioactivity and optical performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 16142–16154 (2021).

Zhang, L., Jin, D. & Stenzel, M. H. Polymer-functionalized upconversion nanoparticles for light/imaging-guided drug delivery. Biomacromolecules 22, 3168–3201 (2021).

Fischer, S., Swabeck, J. K. & Alivisatos, A. P. Controlled Isotropic and Anisotropic Shell Growth in beta-NaLnF4 Nanocrystals Induced by Precursor Injection Rate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 12325–12332 (2017).

Chen, B., Wang, Y., Guo, Y., Shi, P. & Wang, F. NaYbF4@NaYF4 nanoparticles: controlled shell growth and shape-dependent cellular uptake. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 2327–2335 (2021).

Wen, S. et al. Nanorods with multidimensional optical information beyond the diffraction limit. Nat. Commun. 11, 6047 (2020).

Liu, D. et al. Three-dimensional controlled growth of monodisperse sub-50 nm heterogeneous nanocrystals. Nat. commun. 7, 10254 (2016).

Zhao, J. et al. Tuning epitaxial growth on NaYbF4 upconversion nanoparticles by strain management. Nanoscale 12, 13973–13979 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Hedgehog-like upconversion crystals: controlled growth and molecular sensing at single-particle level. Adv. Mater. 29, 1702315 (2017).

Ren, W. et al. DNA-mediated anisotropic silica coating of upconversion nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 54, 7183–7186 (2018).

Mi, C., Zhou, J., Wang, F., Lin, G. & Jin, D. Ultrasensitive ratiometric nanothermometer with large dynamic range and photostability. Chem. Mater. 31, 9480–9487 (2019).

Ren, W. et al. Anisotropic functionalization of upconversion nanoparticles. Chem. Sci. 9, 4352–4358 (2018).

Wan, S. et al. Curvature-guided depletion stabilizes Kagome superlattices of nanocrystals. Science 387, 978–984 (2025).

Frenzel, F. et al. Multiband emission from single β-NaYF4(Yb,Er) nanoparticles at high excitation power densities and comparison to ensemble studies. Nano Res. 14, 4107–4115 (2021).

Yang, Y., Zhu, Y., Zhou, J., Wang, F. & Qiu, J. Integrated strategy for high luminescence intensity of upconversion nanocrystals. ACS Photonics 4, 1930–1936 (2017).

Dong, Y., Cui, H., Li, D., Wu, S. & Qin, W. Surface quenching mechanism and optimal coating shell thickness of nanomaterials. Surf. Interfaces 46, 104012 (2024).

Duong, H. T. T. et al. Systematic investigation of functional ligands for colloidal stable upconversion nanoparticles. Rsc. Adv. 8, 4842–4849 (2018).

Maddahfar, M. et al. Stable and highly efficient antibody-nanoparticles conjugation. Bioconjug. Chem. 32, 1146–1155 (2021).

Wawrzynczyk, D., Piatkowski, D., Mackowski, S., Samoc, M. & Nyk, M. Microwave-assisted synthesis and single particle spectroscopy of infrared down- and visible up-conversion in Er3+ and Yb3+ co-doped fluoride nanowires. J. Mater. Chem. C. 3, 5332–5338 (2015).

Pickel, A. D. et al. Apparent self-heating of individual upconverting nanoparticle thermometers. Nat. Commun. 9, 4907 (2018).

Zhou, J., Del Rosal, B., Jaque, D., Uchiyama, S. & Jin, D. Advances and challenges for fluorescence nanothermometry. Nat. Methods 17, 967–980 (2020).

Jiang, L., Wang, R. & Roskilly, A. Development and thermal characteristics of a novel composite oleic acid for cold storage. Int. J. Refrig. 100, 55–62 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support from Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (J.Z., FT220100018), Centre of Excellence on Quantum Biotechnology (J.Z., and D.J., CE230100021) programs, and Laurate Fellowship (D.J., FL210100180) programs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Z. and D.J. supervised the project. Y.C. conducted the synthesis and characterization. M.L. built the optical system. Y.C., J.Z., and X.Q. participated in the discussion and analysis of all the data. Y.C. and J.Z. prepared the figures and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, Y., Lu, M., Qin, X. et al. Understanding shell coating effects to overcome quenching in single anisotropic upconversion nanoparticles. Nat Commun 16, 4927 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60347-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60347-7