Abstract

Anthropogenic activities have caused large-scale mercury (Hg) pollution in the Arctic reaching toxic levels, but knowledge of sources and pathways is sparse. Here, we present Hg stable isotope data in peat and key aquatic predatory species collected across Greenland. We observe distinct regional differences with significantly lower total Hg and higher δ202Hg in central-western versus northern-eastern Greenland influenced by different ocean currents. While Δ200Hg shows that atmospheric Hg deposition occurs predominantly (60–97%) as Hg(0), Δ199Hg reveals marked photochemical demethylation in especially freshwater habitats. We find δ202Hg in muscle tissue to increase with trophic level linked to internal metabolic transformation. Finally, we observe significant increases in total Hg and δ202Hg for several species/sites during the past 40 years, suggesting an increase in anthropogenic Hg sources and/or change in environmental processes. These findings show that ocean currents carrying large inventories of legacy Hg may be the dominant pathway driving present Hg uptake in Arctic marine and coastal areas. This explains the discrepancy between decreasing atmospheric Hg deposition in the Arctic in recent decades due to reduced global anthropogenic emissions, and the lack of response or increases in Hg-loads in many Arctic species, with implications for effectiveness evaluation of the Minamata Convention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mercury (Hg) is among the most toxic heavy metals and its occurrence in the Arctic environment has increased markedly since pre-industrial times1,2,3. Hg originates from both natural and anthropogenic sources and is transported to the Arctic via atmospheric pathways, rivers, and ocean currents4,5. Since the dawn of industrialization, an increasing fraction of Hg has been released from sources of anthropogenic air emission, such as small-scale gold mining and the burning of fossil fuels, resulting in a ~ 5-fold increase of Hg in the atmosphere6 and a ~3-fold increase in surface ocean waters7. Once Hg enters the Arctic, it biomagnifies in the long Arctic food webs, creating high Hg loads in long-lived top predators such as toothed whales, polar bears (Ursus maritimus) and humans, thereby constituting a threat to biodiversity and health due to adverse neuroendocrine disruption1,2. In recent decades, atmospheric Hg deposition has generally decreased across the Arctic8 due to global reduction of anthropogenic Hg emissions9, whereas predominantly increasing Hg trends occur for many biological matrices in the Arctic, including marine and freshwater fish and marine mammals3. This mismatch leaves important knowledge gaps regarding Hg sources and pathways to and within the Arctic10.

In recent years, Hg stable isotopes have proven to be an important tool in the study of Hg sources and pathways11,12. Hg exhibits both mass-dependent fractionation (MDF, δ202Hg) and mass-independent fractionation (MIF, Δ199Hg, Δ200Hg, Δ201Hg, and Δ204Hg)13. MDF occurs in all investigated biogeochemical transformation processes in the environment11,12, including foliar uptake of gaseous Hg(0)14 and methylation of inorganic Hg by bacteria15, and is seen internally in many species, including birds and mammals associated with metabolic detoxification16. Odd-isotope MIF (Δ199Hg and Δ201Hg) occurs in aquatic systems because of impact by natural sunlight13 and can be used to assess photochemical activity in the environment, including changes in sea-ice cover and turbidity prior to uptake of Hg in the aquatic (both marine and freshwater) food web12,17. Even-isotope MIF (Δ200Hg and Δ204Hg) is considered linked to photo-oxidation of gaseous Hg(0) in the tropopause18, and the Δ200Hg signature is commonly used as a conservative tracer of atmospheric Hg deposition pathways to both terrestrial surfaces and water bodies (i.e. deposition as Hg(0) or Hg(II))14,19,20. Despite scientific momentum in recent years, Hg stable isotopes in Arctic biota remain relatively unexplored14,17,21,22, and only scattered information exists for Greenland20,23,24.

Here, we report a Hg stable isotope study of key aquatic predatory species collected across several regions in Greenland over the past 40 years, to elucidate Hg sources and pathways, environmental processes, internal metabolism and trophic transfer across the Arctic food web, and to identify temporal changes. The species include land-locked Arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus) in the freshwater environment and shorthorn sculpin (Myoxocephalus scorpius), ringed seal (Pusa hispida), and polar bear in the marine environment collected at regular intervals as part of the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP) under the Arctic Council collaboration and previously included in total Hg assessments3. In addition, we include glaucous gull (Larus hyperboreus) despite not currently used for Hg monitoring in AMAP to represent seabirds. Furthermore, we include stable Hg isotopes in peat (palsa) profiles from two different coastal regions in Greenland (Central West and Northeast) to evaluate spatial differences and long-term changes in atmospheric Hg deposition. We observe significant regional differences in δ202Hg signatures of ~0.5-0.6‰ across three different sample types (sculpins, seals, and peat) for central-western versus northern-eastern Greenland influenced by different ocean currents. The Δ200Hg signatures in all samples show that atmospheric Hg deposition occurs predominantly (60-97%) as gaseous elemental Hg (i.e. Hg(0)), and the Δ199Hg reflect marked photochemical demethylation in the aquatic environment especially in freshwater habitats as identified in land-locked Arctic char. We find that δ202Hg in muscle tissue of the marine species (sculpin, ringed seal, glaucous gull, and polar bear) increase with trophic level linked to internal metabolism and isotopic fractionation. Finally, we identify significant increases in total Hg and δ202Hg for several species and sites during the past 40 years, suggesting increases in anthropogenic Hg sources and/or changes in environmental Hg transformation processes important for fractionation. Based on these results, we propose that ocean currents carrying large inventories of legacy Hg may be the main driver of Hg uptake in Arctic marine and coastal environments rather than air transport.

Results and discussion

Spatial trends in sources and pathways

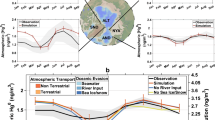

In the peat profiles, Hg stable isotopes reveal significant spatial differences in δ202Hg signatures between Central West Greenland (Qeqertarsuaq) and Northeast Greenland (Zackenberg) (Fig. 1a, b; Supplementary Fig. 1b; Supplementary Data 1). The differences in δ202Hg are consistent throughout the upper 25 cm active layers (i.e. the periodically unfrozen layers), with a median of 0.62‰ higher δ202Hg in the litter and upper 5 cm active layer (representing the most recent deposition) in Central West Greenland (median, −1.16‰; IQR, −1.21 to −1.08‰) compared to Northeast Greenland (median, −1.78‰; IQR, −1.84 to −1.72‰). The δ202Hg signatures decrease with depth and reach near-similar values in the upper part of the permafrost at both sites (Supplementary Fig. 1b; Supplementary Data 1). The Δ199Hg signatures are near-similar for Central West and Northeast Greenland in the litter and upper 5 cm active layer (medians, −0.17 and −0.15‰) (Fig. 1b) and decrease with depth down to c. 50 cm (Supplementary Fig. 1c; Supplementary Data 1). The Δ200Hg signatures show no significant variation with depth and are significantly higher in the litter and upper 5 cm active layer in Central West Greenland (median, 0.02‰; IQR, −0.01 to 0.03‰) than in Northeast Greenland (median, −0.05‰; IQR, −0.06 to −0.03‰) (Supplementary Fig. 1d; Supplementary Data 1). Total Hg concentrations in the peat profiles are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1a.

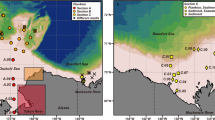

a Map of Greenland showing dominant ocean currents38,39,40 (modified from ref. 71) and the sampling locations. b Odd-isotope mass-independent fractionation (Δ199Hg) versus mass-dependent fractionation (δ202Hg) in two peat profiles from Northeast Greenland (ZAC) and Central West Greenland (QEQ). c, d Δ199Hg versus δ202Hg in muscle tissue of shorthorn sculpin (Myoxocephalus scorpius) and ringed seal (Pusa hispida) from Northwest Greenland (QAA), Central East Greenland (ITT), and Central West Greenland (QEQ). Shorthorn sculpins were sampled between 2021–2023 and ringed seals between 1984-2024. In all figures, bars indicate analytical uncertainty (mean ± 2 SD on replicate standards). Abbreviations used: ZAC Zackenberg, QEQ Qeqertarsuaq, QAA Qaanaaq, ITT Ittoqqortoormiit, ISO Isortoq.

In the marine species, Hg stable isotopes in muscle tissue of shorthorn sculpin and ringed seal reveal similar significant regional differences in δ202Hg signatures between Central West Greenland, Northwest Greenland (Qaanaaq), and Central East Greenland (Ittoqqortoormiit) (Fig. 1c, d). Shorthorn sculpin displays 0.46 to 0.58‰ higher median δ202Hg in Central West Greenland (median, 0.41‰; IQR, 0.33 to 0.47‰) compared to Northwest Greenland (median, −0.17‰; IQR, −0.20 to −0.10‰) and Central East Greenland (median, −0.05‰; IQR, −0.10 to 0.08‰). Ringed seal shows 0.59 to 0.63‰ higher median δ202Hg in Central West Greenland (median, 0.87‰; IQR, 0.63 to 1.24‰) compared to Northwest Greenland (median, 0.24‰; IQR, 0.09 to 0.45‰) and Central East Greenland (median, 0.28‰, IQR, 0.17 to 0.43‰). Δ199Hg and Δ200Hg signatures in shorthorn sculpin and ringed seal do not differ significantly between the three regions (Fig. 1c, d; Fig. 2). Total Hg concentrations are significantly lower in both sculpin liver and ringed seal muscle and liver in Central West Greenland compared to Northwest and Central East Greenland (Supplementary Fig. 2; Supplementary Data 1 and 2).

The samples include muscle tissue of land-locked Arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus), shorthorn sculpin (Myoxocephalus scorpius), glaucous gull (Larus hyperboreus), ringed seal (Pusa hispida), and polar bear (Ursus maritimus) collected in Greenland between 1983-2024 and peat core samples (0-25 cm). Δ200Hg is considered a conservative tracer of atmospheric Hg deposition as Hg(0) or Hg(II) with Δ200Hg = −0.05‰ (interquartile range (IQR), −0.08 to −0.03), corresponding to Hg(0) deposition, and Δ200Hg = 0.14‰ (IQR, 0.09 to 0.18) corresponding to Hg(II) deposition (global averages; ref. 19). The middle line in the box represents the median, the box limits indicate the upper and lower quartiles, and the whiskers represent the range up to 1.5 times the IQR. Analytical uncertainty is 0.05‰ (2 SD on replicate standards). Abbreviations used: ITT Ittoqqortoormiit, QAA Qaanaaq, QEQ Qeqertarsuaq, ISO Isortoq, ZAC Zackenberg.

The consistent geographic differences in δ202Hg signatures in the peat profiles as well as in δ202Hg and total Hg in shorthorn sculpins and ringed seals are surprising and considered likely to reflect long-term regional differences in Hg source inputs to Greenland. Overall, Central West Greenland displays ~0.5 to 0.6‰ higher δ202Hg compared to similar matrices in Northwest, Northeast, and Central East Greenland, with consistent differences observed throughout the active layer in peat profiles (Fig. 1b) and through the last 40 years of sampling for ringed seal (Fig. 3a). Although the peat profiles are not dated, a similar peat profile (i.e. palsa consisting of alternating layers of segregated ice, peat, or mineral soil material) from Northeast Greenland is dated to 2623 ± 123 BP at 50 cm depth25, implying that the Hg in the upper c. 25 cm thick active layer of the peat should represent hundreds of years of deposition though growth rates of palsas vary with time26.

a, b Mass-dependent fractionation (δ202Hg) and odd-isotope mass-independent fractionation (Δ199Hg) in muscle tissue from subadult ringed seals (Pusa hispida) ( ≤ 4 years) in Central West Greenland (QEQ), Northwest Greenland (QAA), and Central East Greenland (ITT). c, d δ202Hg and Δ199Hg in muscle tissue from subadult polar bears (Ursus maritimus) (females ≤4 years; males ≤ 5 years) from ITT. Unfilled symbols are individual measurements and filled symbols are annual medians. Linear regression trendlines are determined based on Mann-Kendall (M-K) and Theil-Sen’s (T-S) slope analysis of the annual medians and test statistics are shown. Solid lines are significant at the p < 0.05 level, dashed lines are not significant. For polar bears, the annual medians are also adjusted for changes in diet over the period (Supplementary Fig. 3; Supplementary Data 1) and the trend lines (dotted lines) as well as test statistics for the diet adjusted medians are shown. Analytical uncertainty is 0.14‰ for δ202Hg and 0.05‰ for Δ199Hg (2 SD on replicate standards). Abbreviations used: QEQ Qeqertarsuaq, QAA Qaanaaq, ITT Ittoqqortoormiit.

However, using δ202Hg as source tracers in peat profiles and biological tissue samples pose limitations. For peat, factors such as vegetation type and decomposition/leaching may influence δ202Hg27,28. Consequently, to minimize potential effects of vegetation type and decomposition on the δ202Hg between sites, we chose two representative palsas, one from each region, both considered ombrotrophic and fully covered with a similar vegetation type dominated by sedges including Carex and Eriophorum species as well as a diverse moss flora. We observe the same spatial difference in δ202Hg in the fresh litter layer and through the upper 25 cm of the active layer between the two regions (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Fig. 1b; Supplementary Data 1), indicating little/no effects from to varying decomposition between the two sites. Thus, the consistently higher δ202Hg signatures in Central West Greenland throughout the top 25 cm active layer compared to the Northeast Greenland profile indicate persistent long-term regional differences in δ202Hg inputs. For the biological tissue samples, δ202Hg signatures are influenced not only by the Hg source input to the environment but also by all biogeochemical transformation processes (e.g. microbial methylation/demethylation)11,12 as well as prey species/trophic level29,30, and internal metabolism in the species12,16. Here, we choose to compare δ202Hg signatures in similar species (shorthorn sculpin and ringed seal) and tissues (muscle) across the three regions to minimize effects related to differences in prey species/trophic level and internal metabolism. The consistent ~0.5 to 0.6‰ higher δ202Hg in Central West Greenland compared to the other Greenland regions for both peat (mainly influenced by atmospheric Hg(0) source uptake22,31) and marine species (considered mainly influenced by marine methyl-Hg source uptake32) suggests an overall difference in Hg source inputs between the regions. However, we cannot rule out that regional differences in environmental biochemical processes affecting the δ202Hg can have additional minor effects.

The significant spatial difference in δ202Hg for Greenland contrasts with recent model predictions for atmospheric Hg deposition in the Arctic showing regional differences in absolute deposition but relatively uniform source compositions, reflecting a relatively long lifetime of Hg in the atmosphere (~0.5–1 y)33 and effective mixing of source inputs4. Atmospheric Hg transport to the Arctic follows a general pattern dominated by northern Eurasian sources in winter and mid-latitude Asian and North American sources in spring4,34. The significantly higher δ202Hg in all sample matrices at the Central West Greenland site, located only ~1000 km from the Northwest Greenland site and both being exposed to the same overall atmospheric transport patterns, is therefore surprising. This suggests that direct atmospheric Hg deposition may not, as currently predicted5, be the dominant pathway for Hg pollution in marine and coastal areas in Greenland and perhaps also elsewhere in the Arctic. Inputs of Hg from rivers or glacial meltwater in Greenland are considered low35,36,37 and therefore not a likely cause of the observed δ202Hg variation.

Instead, we propose that ocean currents may be the main Hg pathway explaining the significantly lower total Hg concentrations and higher δ202Hg observed in marine and coastal areas in Central West Greenland than in Northwest, Northeast, and Central East Greenland. Central West Greenland is dominated by the relatively warm West Greenland Current, which is a mixed current comprising a branch of the Irminger Current from the North Atlantic Ocean and a branch of the East Greenland Current originating from the Arctic Ocean (Fig. 1a)38. The other Greenland regions are all dominated by currents from the Arctic Ocean39,40. The total Hg concentrations measured in North Atlantic waters are lower than in Arctic waters5,41,42, with North Atlantic-sourced water flowing into the Arctic having lower Hg (0.15 ± 0.07 ng/l) than Arctic Ocean surface waters (0.24 ± 0.12 ng/l)5. Further, the few studies available on Hg stable isotopes in seawater report higher δ202Hg in the North Atlantic waters (median, −0.45‰)19 than in Arctic Ocean waters (−2.85 to −1.10‰)43. Consequently, we hypothesize that ocean currents may be the main driver of Hg uptake in marine and coastal environments in Greenland, and other Arctic regions, either through direct uptake of Hg from ocean waters or through Hg evasion from the ocean surface followed by atmospheric redeposition and uptake, explaining the significantly lower total Hg in marine species and higher δ202Hg in both marine species and peat profiles in Central West Greenland influenced by Atlantic Ocean water. It is interesting to note that the same regional difference in δ202Hg as recorded for marine species occurs in the peat profiles in Central West Greenland and Northeast Greenland, situated 800 m and 2 km inland, respectively. This may be due to a greater influence of atmospheric Hg deposition from sea spray and/or evasion/redeposition of Hg from regional ocean surface waters24 compared to long-distance atmospheric sources. The influence of sea spray on the vegetation in coastal zones is well known44, and laboratory studies have shown that sea salt aerosols have a high capacity for uptake of reactive gaseous Hg45. A recent study shows that oceanic evasion is likely the dominating source and pathway to atmospheric Hg(0) in the Arctic during summertime ( ~ 80%) driving the transport to Arctic terrestrial ecosystems46. Likewise, evasion from the ocean surface waters is known to constitute a major part ( ~ 43%) of the global Hg flux budget8.

The Hg transported by ocean currents includes Hg previously deposited from the atmosphere to the ocean and terrestrial surfaces, which is later transported to the ocean via rivers and glaciers. The Δ200Hg signatures in peat profiles and aquatic biota have been used as a conservative tracer of atmospheric deposition pathways (as elemental Hg (Hg(0)) or Hg(II) wet or dry deposition, respectively) in numerous previous studies19,28,47. The Δ200Hg signatures in the peat profiles and marine and freshwater species in Greenland indicate that the dominant atmospheric deposition pathway is as Hg(0) rather than Hg (II) (Fig. 2). Jiskra et al.19 applied a two-source mixing model for the northern hemisphere with a Δ200Hg value of −0.05 as end-member Hg(0) dry deposition and a Δ200Hg value of 0.14 as end-member Hg(II) of combined wet and dry deposition. Applying the same regression line for the peat litter layer and upper 5 cm active layer in Central West Greenland and Northeast Greenland indicates that ~64 and ~97% (medians) of the current/recent vegetation uptake and Hg deposition in these two regions occurred as Hg(0) deposition and the remaining ~36% and ~3% as Hg(II) wet or dry deposition. For the entire peat active layer profiles down to 25 cm depth, the median Hg depositions as Hg(0) are ~72 and ~92% for Central West Greenland and Northeast Greenland, respectively. These estimates include net deposition of Hg(II) from atmospheric mercury depletion events (AMDEs) occurring in the Arctic during springtime48 in the estimated Hg(0) deposition, as the Δ200Hg signatures are considered unaffected by AMDEs20,22. During AMDEs, sea salt-derived halogen radicals oxidize atmospheric Hg(0) to Hg(II), leading to substantial Hg deposition from the atmosphere48. The Δ200Hg signatures in the marine and freshwater species in this study indicate that between ~60 and ~87% of the Hg bioaccumulated in the species are atmospherically deposited as Hg(0), while the remaining ~13 to ~40% are deposited via wet or dry Hg(II) deposition (Fig. 2). These values are consistent with the range of recently observed Δ200Hg values for other areas in the Arctic14,19,20,21.

No consistent spatial differences in Δ199Hg are observed between similar sample types across the studied Greenland regions in contrast to some Arctic studies21,23, likely because the regions cover a relatively limited latitude range (69-77°N) and therefore have comparatively similar photochemical exposure.

Environmental processes and trophic transfer

In the marine species, total Hg concentrations in muscle tissue are lowest in sculpin, ringed seal, and polar bear (medians, 0.09 to 0.36 μg/g wet weight (ww)), followed by glaucous gull (median, 0.61 μg/g ww), while land-locked Arctic char exhibits the highest concentrations (median, 0.66 μg/g ww) (Supplementary Data 2). Hg stable isotope signatures vary significantly between matrices (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Data 2). Peat has the lowest δ202Hg (medians in active layer, −1.4 and −1.7‰ for Central West and Northeast Greenland, respectively) and Δ199Hg (medians in active layer, −0.16 and −0.33‰). Marine species show a large variation in δ202Hg (medians, −0.17 to 2.2‰) and Δ199Hg (medians, 0.75 to 1.2‰) in muscle tissue. Land-locked Arctic char shows a δ202Hg in muscle tissue within the range of the marine species (median, 0.93‰), while Δ199Hg is significantly higher (median, 6.2‰). Δ200Hg signatures exhibit relatively little variation between sample matrices (medians, −0.038 to 0.038) (Fig. 2; Supplementary Data 2).

a Odd-isotope mass-independent fractionation (Δ199Hg) versus mass-dependent fractionation (δ202Hg) in the muscle tissue of all samples included in this study, i.e., land-locked Arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus, n = 32), shorthorn sculpin (Myoxocephalus scorpius, n = 58), glaucous gull (Larus hyperboreus, n = 15), ringed seal (Pusa hispida, n = 239), and polar bear (Ursus maritimus, n = 195) sampled in Greenland in 1983-2024, and peat core samples (down to 25 cm depth, n = 35). b Odd-isotope mass-independent fractionation signatures (Δ201Hg and Δ199Hg) in all muscle tissues of land-locked Arctic char (inserted graph) and marine aquatic key species in this study compared to experimentally measured trendlines for residual methyl-Hg from aqueous photochemical demethylation and residual Hg(II) from aqueous photochemical reduction of Hg(II)13. c Boxplot of δ202Hg in the muscle and liver of land-locked Arctic char, shorthorn sculpin, ringed seal, glaucous gull, and polar bear sampled in 2021-2023. For polar bear, δ202Hg in hair and kidney is also shown. The middle line in the box represents the median, the box limits indicate the upper and lower quartiles, and the whiskers represent the range up to 1.5 times the interquartile range. d, Δ199Hg versus δ202Hg in the muscle tissue of shorthorn sculpin, ringed seal, glaucous gull, and polar bear sampled in 2021-2023 in Central East Greenland (ITT), representing different trophic levels (although food web dynamics are complex as discussed in the text). Abbreviations used: ITT Ittoqqortoormiit, QAA Qaanaaq, QEQ Qeqertarsuaq, ISO Isortoq, ZAC Zackenberg. In all the figures, the bars indicate analytical uncertainty (mean ± 2 SD on replicate standards), and ellipses show 95% confidence intervals.

We observe trophic level differences in δ202Hg signatures with significantly increasing δ202Hg in muscle tissue between shorthorn sculpin, ringed seal, glaucous gull, and polar bear in Central East Greenland (Fig. 4d). We see a similar significant trophic level difference in δ202Hg for shorthorn sculpin and ringed seal in Central West Greenland and Northwest Greenland (Fig. 1c, d; Supplementary Data 2). Ringed seal has 0.33 to 0.46‰ higher median δ202Hg and glaucous gull has 0.94‰ higher median δ202Hg compared to shorthorn sculpin. Polar bear exhibits the highest δ202Hg, with 1.8 to 2.2‰ higher median δ202Hg compared to shorthorn sculpin and 1.4 to 1.9‰ higher median δ202Hg compared to ringed seal. Shorthorn sculpin and ringed seal in Central East Greenland have significantly lower Δ199Hg signatures (medians, 0.87 to 0.89‰) than glaucous gull and polar bear (medians, 0.98 to 1.0‰).

To assess the dominant photochemical processes in the aquatic environment prior to Hg uptake, we compared Δ199Hg and Δ201Hg ratios in the aquatic species to experimentally established ratios representing photochemical reduction (1.00 ± 0.02) and photochemical demethylation (1.36 ± 0.02)13 (Fig. 4b). Median Δ199Hg/Δ201Hg in muscle tissue of the five species at the four sites ranges from 1.18 to 1.36, corresponding to 50–100% uptake of residual methyl-Hg from photochemical demethylation, with the following species-specific ratios and percentages of photochemical demethylation: shorthorn sculpin (medians, 1.21 to 1.36, 58-100%), ringed seal (medians, 1.25 to 1.36, 69-100%), glaucous gull (median, 1.18, 50%), polar bear (medians, 1.22 to 1.30, 61-83%), and Arctic char (median, 1.31, 86%).

To evaluate species-specific internal metabolic transformation processes as the driving mechanism behind the trophic level differences in δ202Hg, we measured Hg stable isotopes in muscle and liver of Arctic char, shorthorn sculpin, ringed seal, glaucous gull, and polar bear (Fig. 4c; Supplementary Data 2). In polar bear, we also measured Hg stable isotopes in hair and kidney. Shorthorn sculpin shows no difference in δ202Hg between muscle and liver, but all other species exhibit higher δ202Hg in muscle than in liver, significantly so for ringed seal and polar bear. For these species, differences in δ202Hg between muscle and liver are lowest in glaucous gull (median, 0.25‰) and Arctic char (median, 0.33‰) and highest in ringed seal (median, 1.1‰) and polar bear (median, 2.6‰). Polar bear hair has a δ202Hg signature that is not significantly different from that of muscle, and the δ202Hg signature of kidney is not significantly different from that of liver.

The significantly lower δ202Hg signatures observed in peat compared to marine and freshwater species are likely predominantly caused by the large isotope fractionation by foliar uptake14,22. Obrist et al.14 found that foliar uptake produced a negative shift in δ202Hg in Arctic tundra vegetation of ~−2‰ compared to Hg deposited as Hg(0). Uptake of Hg(0) by vegetation is considered the dominant pathway of atmospheric Hg deposition to terrestrial surfaces, both in the Arctic22 and globally31.

The large difference in 199Hg signatures between atmospherically deposited Hg in peat and the Hg found in marine species and, especially, freshwater species (Fig. 4a), evidence that Hg is subject to photochemical processing in the aquatic environment after mobilization and before entrance in the food chain. Once Hg accumulates in the food chain, negligible MIF is expected since the bioaccumulated Hg is no longer exposed to direct sunlight12. The Δ199Hg/Δ201Hg ratios in the marine and freshwater species included in this study (Fig. 4b) demonstrate that photochemical demethylation followed by uptake of residual methyl-Hg (rather than photochemical reduction followed by uptake of residual Hg (II)) is the dominant photochemical process affecting the Hg uptake in both marine and freshwater habitats in Greenland. The significantly higher Δ199Hg values observed in land-locked Arctic char compared to the marine species are considered due to intense in-lake photochemical demethylation at the South Greenland sampling site. It is well documented that freshwater and open-ocean fish have high Δ199Hg values relative to coastal and benthic fish11,29.

We observe an increase in δ202Hg signatures in muscle tissue with increasing trophic level for shorthorn sculpin, ringed seal, glaucous gull, and polar bear in Central East Greenland. The four species represent different trophic levels, but the food chain dynamics are complex, and except for ringed seals and polar bears, the species in the food chain may not be directly linked. Furthermore, the species have different mobility and therefore take up Hg at varying distances from the sampling sites. Sculpins are known as a sedentary benthic fish species with a generalist feeding strategy encompassing amphipods, polychaetes, decapods, molluscs, and other fish in their diet49. Ringed seals in East and Northwest Greenland are known to feed mainly on polar cod (Boreogadus saida) and Arctic cod (Arctogadus glacialis), whereas ringed seals in Central West Greenland primarily prey on amphipods (Parathemisto spp.), capelin (Mallotus villosus), redfish (Sebastes sp.), and squid (Gonatus sp.)50. The ringed seal ecology is closely connected to the sea ice and most adult ringed seals are believed to be rather stationary, whereas juvenile ringed seals from different parts of the Arctic have been reported to travel over large distances (>1000 km)51. Glaucous gulls are top predators and scavengers, and feed on a variety of prey items, including marine invertebrates, fish, birds, and bird eggs as well as e.g. polar bear left-over seal carcases52. Glaucous gulls come to East Greenland in spring and leave in late October to winter at lower latitudes, possibly around Iceland53. Polar bears are top predators and feed predominantly on ringed seals, hooded seals (Cystophora cristata), and harp seals (Pagophilus groenlandicus) in East Greenland but occasionally also on other food items (e.g. bearded seals (Erignathus barbatus), narwhal (Monodon monoceros), and Atlantic walrus (Odobenus rosmarus))54. The Central East Greenland polar bear subpopulation is one of 20 recognized subpopulations of polar bears in the world and the movement patterns cover >2000 km of pack ice and fast ice along the East Greenland coast above 64°N55.

We consider the observed MDF and increase in δ202Hg between trophic levels to be mainly caused by internal metabolic transformation processes, involving demethylation in the liver/kidneys and excretion of inorganic Hg with the urine, leading to enhanced δ202Hg in the residual methyl-Hg16, which is then transferred via the diet from prey to predator. We detect significant internal fractionation for ringed seal and polar bear, with lower δ202Hg in the liver (and kidney for polar bear), which is known to contain significant proportions of inorganic Hg56, and higher δ202Hg in muscle tissue (and hair for polar bear), which is known to contain almost 100% methyl-Hg56. Previous studies have detected internal MDF in some fish species as well as in seabirds and marine mammals16. However, to our knowledge, this is the only study on internal Hg fractionation in these Arctic key species and no studies exist on Hg stable isotopes in the muscle tissue of shorthorn sculpins, ringed seal, glaucous gull, and polar bear from other areas in the Arctic that can be used for comparison. Previous studies have shown MDF shifts and increases in δ202Hg related to the trophic transfer in non-Arctic areas29,30.

The significantly lower Δ199Hg signatures in shorthorn sculpins and ringed seals than in glaucous gull and polar bear in Central East Greenland indicate that sculpins and ringed seals are more influenced by Hg from benthic prey items, which are less impacted by photochemical processes29,57. In contrast, glaucous gulls and polar bears may at least partly feed on more pelagic prey items.

Temporal trends and future perspectives

The peat profiles from Central West Greenland and Northeast Greenland, representing long-term time series of Hg deposition, show increases in δ202Hg from −1.9 and −2.8‰, respectively, in the permafrost up to −1.0 and −1.6‰ in the active layers in Central West Greenland and Northeast Greenland, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1b; Supplementary Data 1), and the increases in Δ199Hg range from −0.64 and −0.59‰ in the permafrost up to −0.11 and −0.10‰ in the active layers (Supplementary Fig. 1c; Supplementary Data 1). In the marine species, total Hg in sculpin liver in Central West, Northwest, and Central East Greenland, and total Hg in ringed seal liver (all subadults, ≤4 y) in Northwest Greenland demonstrate a significant log-linear (i.e. exponential) increasing temporal trend for the period 1983-2024 (Supplementary Fig. 2a–c; Supplementary Data 1). Total Hg in ringed seal muscle and liver in Central West and Central East Greenland exhibits no significant temporal trend. Total Hg in polar bear liver and hair (all subadults, males ≤5 y and females ≤4 y) in Central East Greenland show a significant log-linear increasing temporal trend from 1983 to 2024 (Supplementary Fig. 2d; Supplementary Data 1). Notably, however, corresponding muscle samples from the same individuals show a significant decreasing trend.

The δ202Hg signatures in ringed seal and polar bear muscle show significant increasing trends for ringed seals in Northwest Greenland and for polar bears in Central East Greenland during 1983–2024 but no significant trend for ringed seals in Central West and Central East Greenland (Fig. 3a and c). The total increase in δ202Hg was ~0.5‰ for the ringed seals in Northwest Greenland, ~0.7‰ for the ringed seals in Central West Greenland, and ~1.7‰ for the polar bears in Central East Greenland during 1983-2024. Part of the increase in δ202Hg in the polar bears in Central East Greenland can be ascribed to a documented shift in diet during the period with consumption of significant less ringed seals having lower δ202Hg (median in muscle tissue, 0.28; n = 82) towards more hooded seals having higher δ202Hg (median, 1.19; n = 27) (Supplementary Fig. 3; Supplementary Data 1)54,58. These differences in δ202Hg between seal species are considered to mainly reflect differences in prey species59. When accounting for this change in diet composition for the polar bears, the increase in δ202Hg is reduced from ~1.7‰ to ~1.2‰ (Fig. 3c). We do not have similar data for potential changes in diet for the ringed seals. The Δ199Hg signatures in ringed seals in the three regions show no significant temporal trend during 1983–2024 (Fig. 3b), but polar bears in Central East Greenland demonstrate a near-significant increase (p = 0.06) (Fig. 3d) totalling ~0.19‰ for the entire period, which is reduced to ~0.10‰ and becomes insignificant (p = 0.27) when accounting for changes in diet composition.

For the peat profiles, the overall decreases in δ202Hg and Δ199Hg signatures with depth in Central West and Northeast Greenland follow a general global trend for lake sediment60. The higher δ202Hg in the top layers is in line with higher δ202Hg reported for modern anthropogenic Hg emissions61, whereas increasing Δ199Hg in more recent deposition may reflect a general change in environmental conditions60. The significant differences in δ202Hg and Δ199Hg between the active layer and the upper permafrost in Central West and Northeast Greenland with low δ202Hg and Δ199Hg in the permafrost are noteworthy. These differences may enable detection of a potentially increasing uptake of legacy Hg in Arctic aquatic species from thawing permafrost and subsequent river transport, which is currently a concern in the Arctic. Thus, recent estimates show that permafrost regions contain 7% of Earth’s global soil Hg pool62, and studies from Arctic Canada and Alaska describe elevated Hg fluxes in rivers attributed to permafrost and glacier ice thawing63,64. Further studies are needed to determine if these differences in δ202Hg and Δ199Hg in active layers and upper permafrost apply to larger areas in the Arctic.

For the marine species, significantly increasing temporal trends of total Hg in liver tissue of shorthorn sculpin, ringed seal, and polar bear (and in hair for polar bear) during 1983–2024 indicate increased Hg-loading in the Greenland marine environment during the last four decades, which has now reached toxic levels for top-predators such as polar bears with increases in total Hg in hair above the reported effect concentration of 6 ng/g (ref. 2) (Supplementary Fig. 2d; Supplementary Data 1). Liver tissue is the most often used matrix for temporal assessment of Hg loading in Arctic biota3 and reflects accumulation during a longer timespan compared to muscle and hair65. The increasing Hg trends in Greenland biota contradict the decreasing atmospheric Hg deposition trends observed across the Arctic during the last decades8 and support a general global disagreement between biota time series and atmospheric deposition trends10.

The temporal trends with increasing δ202Hg signatures in both ringed seals in Central West and Northwest Greenland, and in polar bears in Central East Greenland, are notable and indicate a change in Hg source composition during the last 40 years but can also be influenced by changes in biogeochemical processes in the environment during this period (Fig. 3a and c). The observed trends in Greenland towards generally higher δ202Hg signatures in ringed seals and polar bears during the last 40 years are in line with long-term trends observed in Hg depositions globally caused by an increased influence of anthropogenic Hg emissions60,61 but may also reflect changes in environmental transformation processes affecting the δ202Hg in the methyl-Hg taken up in the food web11,12.

We propose that the disagreement between increases in total Hg in many biota time series in the marine environment in Greenland, and other regions in the Arctic, and the decreases in atmospheric Hg deposition over the Arctic during the last decades, is predominantly due to the large inventory of legacy Hg in the aquatic environment transported by ocean currents. This causes a substantial lag in the response time between changes in external input from the atmosphere and the biotic response. Changes in physical, geochemical, biological, and ecological conditions, affecting the complex biogeochemical Hg cycling10, may also be factors contributing to the disagreement. The influence of ocean currents and the aquatic Hg inventory is reflected by significant differences in total Hg and δ202Hg between Central West and Northwest Greenland, which are situated only 1000 km apart and exposed to the same overall atmospheric wind transport regime but are influenced by different ocean currents (i.e. the Irminger Current from the North Atlantic and the Arctic Ocean currents, Fig. 1a), with different total Hg and δ202Hg levels. The observed increase in δ202Hg in some Greenland biota series during the last 40 years indicates enhanced contribution from modern-time anthropogenic sources and/or changes in environmental Hg transformation processes, but there may be a considerable time lag. The lifetime of Hg in the ocean is much longer than in the atmosphere, with estimated turnover times of >300 years66. These findings have major implications for the current understanding of the Arctic Hg cycle and for the effectiveness evaluation of UN’s Minamata Convention as the high Hg concentrations observed in the Arctic marine biota are likely to persist for a much longer period than previously anticipated, regardless of atmospheric emissions, especially in larger deeper marine ecosystems. Biota in smaller water bodies with less capacity for legacy Hg, such as lakes or shallow coastal environments with limited water mass turnover, are likely to respond faster to emission control. However, sea spray and oceanic evasion/redeposition of Hg will impact all Arctic marine and coastal ecosystems and may also dominate summertime transport to Arctic terrestrial ecosystems46. Consequently, biomonitoring to evaluate regulation efforts should be diverse and include multiple species occupying different ecological and geographic niches.

This study documents geographic differences and temporal trends in Hg sources and pathways, environmental processes, and trophic transfer across Greenland. Future studies using both total Hg and Hg stable isotopes are needed to document geographic trends in key species and samples covering the circumpolar Arctic, including Alaska, Arctic Canada, and Svalbard, to expand our knowledge of the Arctic Hg cycle. The influence of the ocean transport of legacy Hg should also be investigated in other global regions to help evaluate the effects of Hg regulations under the Minamata Convention and to fulfil UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

Methods

Inclusion and ethics

We have engaged local subsistence hunters and other persons from the local communities in Greenland in the samplings and several persons from Aarhus University and University of Copenhagen including technical staff and students have been involved in the study but without qualifying for co-authorship (but are included in the Acknowledgements section). Authorship follows the Vancouver recommendations and individual contributions have been clarified in the Author contributions section. The analysed animal tissue samples were mainly harvested by local subsistence hunters in Greenland following local legislation, practices, ethics, and hunting quotas. All samples obtained from polar bears were under the international IUCN CITES regulations legally exported from Greenland (295/2000, 61/2001, 69/2001, 66/2003, 156/2004, 23/2005, 17/2006, 08GL0706599, 09GL0805839, 10GL0806166, 10GL0805167, 42 10GL0806333, 10GL0806334, 11GL1003311, 12GL1003376, 13GL1003418, 14GL1003515, 15GL1166847, 16GL1167015, 17GL1167116, 18GL1717224, 19GL1717365, 20GL1717427) to Denmark (IM 0813-642/01, IM 0312-080/01, IM 1116-901/04, IM 1116-954/05, IM 0316-613/06, IM 0811-266/06, IM 0711-993/08, IM 0630-137/09, IM 0611288/10, IM 0611-290/10, IM 1223-856/10, IM 1223-855/10, IM 1214-596/11, IM 1199-728/12, IM 0826-378/13, IM 1202-211714, IM 1222-060/15, IM 1202-580/16, IM 0818-549/17, IM 0928-712/18, IM0816-496/19, DK2020-0017113-01).

Sampling

The sampling of Arctic char, shorthorn sculpin, ringed seal, glaucous gull, and polar bear was conducted in Greenland during 1983–2024; since 1994 in association with deliveries to the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP). Although glaucous gulls are not currently used for Hg monitoring in AMAP, they are included in this study to represent seabirds. More detailed information on sampling year(s) for each sample type is provided in Supplementary Data 2. The locations of the sampling sites are shown in Fig. 1a. The AMAP sampling sites with approximate coordinates are Ittoqqortoormiit (70º29′N, 21º58′W), Qaanaaq (77º28′N, 69º14′W), Qeqertarsuaq (69º15′N, 53º32′W), and Isortoq (60º54′N, 47º33′W). A thorough description of the programme is given in AMAP (2021)67.

Peat was sampled at palsas in Zackenberg and Qeqertarsuaq. A palsa is a typical feature of a permafrost-affected landscape and is common in poorly drained lowlands in Greenland68. Palsas are mounds that contain lenses of segregation ice and represent continuous peat formation and formation of ice in the core due to capillary water undergoing slow freezing68. Palsa formation and collapse is a dynamic feature68. Two complete (non-collapsing) palsas were sampled: one east of the Zackenberg River and north of Zackenberg Research Station (74°29'05“N; 20°33'58“W) in Northeast Greenland with a height of c. 1 m and one in Blæsedalen east of Qeqertarsuaq on Disko Island (69°16'05“N; 53°28'06“W) in West Greenland with a height of c. 0.7 m. The Zackenberg palsa was sampled in September 2012 and the Disko palsa in August 2022. Both palsas were fully covered by vegetation dominated by mosses and grasses. Roots occurred at both locations throughout the top 25 cm but dominated the top 5 cm. A nearby palsa in the Zackenberg area has been dated based on microfossils to 2623 ± 123 BP (14C AMS) at 0.5 m depth25. The samples were collected from the litter layer and the active layer comprising the top 25 cm. From the permafrost table, a steel pipe was hammered down into the soil with 10 cm depth increments, after which the sample was carefully collected from the pipe before sampling the next 10 cm. The samples were stored in plastic bags and kept frozen (below −6 °C). Prior to analyses, the samples were taken out of the freezer and the outer 0.5 to 1 cm cut off with a ceramic knife and discarded. The samples were subsequently cut into slices using a ceramic knife and put into plastic bags for further processing.

Chemical analyses

All samples were freeze dried prior to analysis, and the dry matter content was determined.

For muscle samples, subsamples of c. 0.4 g homogenized tissue were digested in a mixture of 4 ml nitric acid and 4 ml Milli-Q water in an Anton Paar 7000 Multiwave microwave oven (220 °C, 30 min). For liver and kidney, subsamples of c. 0.3 g homogenized tissue, and for hair and peat subsamples of c. 0.075 g and c. 0.5 g, respectively, were applied following the same digestion procedure as above. One blank, one duplicate, and at least one sample of certified reference material (CRM) were included in every series of digestions (18 vials). Immediately after digestion, 1 ml HCl was added, followed by dilution to c. 50 g with Milli-Q water. The CRMs DORM-5 (fish protein), DOLT-5 (dogfish liver), and TORT-3 (lobster hepatopancreas) were included in muscle, liver, and kidney digestions, respectively, IAEA-086 (human hair) in hair digestions, and ERM-CD-281 (rye grass) and NIST-1515 (apple leaves) in peat digestions.

Digestion solutions were analyzed for total Hg using an Agilent 7900 ICP-MS. Results of the CRMs showed close to 100% recovery of Hg (mean recovery ± 2 SD; DORM-5 (n = 46): 103 ± 15%; DOLT-5 (n = 9): 96 ± 15%; TORT-3 (n = 11): 105 ± 16%; IAEA-086 (n = 9): 100 ± 13%; ERM-CD-281 (n = 7): 111 \(\pm\) 16%; and NIST-1515 (n = 7): 105 ± 4%).

Next, the digestion solutions were analyzed for Hg isotopes using a Thermo Neptune XT MC-ICP-MS equipped with a Cetac HGX-200 cold vapor introduction system using 3% SnCl in 10% HCl (v/v) as reductant and a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min69. Prior to analysis, the digestion solutions were diluted to 1 ppb Hg for muscle, liver, kidney, and hair samples and 0.5 ppb for peat using an acid mixture corresponding to the solutions. The digestion solutions of peat containing <0.5 ppb (0.2–0.5 ppb, corresponding to 20–50 ng/g in samples) were analyzed without further treatment. The masses 198, 199, 200, 201, 202, and 204 were measured using Faraday cups with 1013 Ω amplifiers on mass 198 and 199, and 1011 Ω amplifiers on the other masses. Sensitivity was typically 0.5 V on mass 202 for 1 ppb Hg solution. Measurements were done using std-sample-std bracketing with NIST 3133 CRM as standard with a similar concentration as the samples, and a measurement time of 10 min. Signal intensities measured in digestion solutions corresponded well the NIST 3133 CRM showing minimum matrix dependency. The delta values δ202Hg, Δ199Hg, Δ200Hg, Δ201Hg, and Δ204Hg were determined relative to NIST 3133 as described in ref. 13 One blank sample and one NIST 8610 CRM were analyzed for at least every six samples to assess contamination/carry-over and accuracy/precision. Blank samples had signal intensities of <1% of samples and CRMs. The following values (mean ± 2 SD in ‰) were measured on the NIST 8610 in 1 ppb solution (n = 172) (δ202Hg: −0.54 ± 0.14; Δ199Hg: −0.02 ± 0.05; Δ200Hg: 0.01 ± 0.05; Δ201Hg: −0.04 ± 0.08, and Δ204Hg: 0.00 ± 0.14), 0.5 ppb solution (n = 10) (δ202Hg: −0.58 ± 0.10; Δ199Hg: −0.04 ± 0.05; Δ200Hg: 0.03 ± 0.04; Δ201Hg: −0.04 ± 0.07, and Δ204Hg: 0.05 ± 0.13), and 0.2 ppb solution (n = 5) (δ202Hg: −0.66 ± 0.16; Δ199Hg: −0.09 ± 0.10; Δ200Hg: 0.07 ± 0.07; Δ201Hg: −0.09 ± 0.09, and Δ204Hg: 0.19 ± 0.25), which are all within the range of certified values. The CRM IAEA-086 was also measured for Hg isotopes (n = 6) and the results (δ202Hg: 0.80 ± 0.03; Δ199Hg: 0.31 ± 0.03; Δ200Hg: 0.02 ± 0.02; Δ201Hg: 0.21 ± 0.02, and Δ204Hg: −0.10 ± 0.06) were close to previously reported values70.

The total Hg results reported in Supplementary Fig. 2 were analyzed as part of the AMAP Core biota monitoring programme in Greenland with results most recently published in 2022 (ref. 3), and we refer to method descriptions in references herein.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were done using R version 4.2.3. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to determine differences in Hg stable isotope signatures between sites and species. Prior to the ANOVA, a Shapiro-Wilk test was conducted to test for normality of data, and a Brown-Forsythe test was undertaken to test for equal variances between groups. A Welch ANOVA test was applied due to unequal variances identified for some groups, and a Games-Howell post hoc test was used to assess individual group differences (using R-package ‘rstatix 0.7.1’). Temporal trends in Hg stable isotope signatures were evaluated using the Mann-Kendall and Theil-Sen’s slope analysis on subadult ringed seals (≤4 years) and polar bears (males ≤5 years; females ≤4 years) (using R-packages ‘Kendall 2.2.1’ and ‘mblm 0.12.1’). Differences were regarded significant at p < 0.05. Temporal trends in Hg stable isotope signatures in Central East Greenland polar bears were adjusted for changes in diet composition using modelled diet compositions over time54,58 and Hg stable isotope signatures in prey items (see Supplementary Fig. 3; Supplementary Data 1).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data presented in this paper are provided in Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Data 2, or in the Source Data file, which may be used to generate all figures in the paper. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

This paper does not report any original code(s).

References

Dietz, R. et al. Current state of knowledge on biological effects from contaminants on arctic wildlife and fish. Sci. Total Environ. 696, 133792 (2019).

Dietz, R. et al. A risk assessment review of mercury exposure in Arctic marine and terrestrial mammals. Sci. Total Environ. 829, 154445 (2022).

Morris, A. D. et al. Temporal trends of mercury in Arctic biota: 10 more years of progress in Arctic monitoring. Sci. Total Environ. 839, 155803 (2022).

Dastoor, A. et al. Arctic atmospheric mercury: sources and changes. Sci. Total Environ. 839, 156213 (2022).

Dastoor, A. et al. Arctic mercury cycling. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 270–286 (2022).

Outridge, P. M., Mason, R. P., Wang, F., Guerrero, S. & Heimbürger-Boavida, L. E. Updated global and oceanic mercury budgets for the United Nations Global Mercury Assessment 2018. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 11466–11477 (2018).

Lamborg, C. H. et al. A global ocean inventory of anthropogenic mercury based on water column measurements. Nature 512, 65–68 (2014).

MacSween, K. et al. Updated trends for atmospheric mercury in the Arctic: 1995-2018. Sci. Total Environ. 837, 155802 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Observed decrease in atmospheric mercury explained by global decline in anthropogenic emissions. PNAS 113, 526–531 (2016).

Wang, F. et al. How closely do mercury trends in fish and other aquatic wildlife track those in the atmosphere? – Implications for evaluating the effectiveness of the Minamata convention. Sci. Total Environ. 674, 58–70 (2019).

Blum, J. D., Sherman, L. S. & Johnson, M. W. Mercury isotopes in earth and environmental sciences. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 42, 249–269 (2014).

Tsui, M. T.-K., Blum, J. D. & Kwon, S. Y. Review of stable mercury isotopes in ecology and biogeochemistry. Sci. Total Environ. 716, 135386 (2020).

Bergquist, B. A. & Blum, J. D. Mass-dependent and -independent fractionation of Hg isotopes by photoreduction in aquatic systems. Science 318, 417–420 (2007).

Obrist, D. et al. Tundra uptake of atmospheric elemental mercury drives Arctic mercury pollution. Nature 547, 201–204 (2017).

Rodriguez-Gonzalez, P. et al. Species-specific stable isotope fractionation of mercury during Hg(II) methylation by an anaerobic bacteria (Desulfobulbus propionicus) under dark conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 9183–9188 (2009).

Li, M.-L. et al. Internal dynamics and metabolism of mercury in biota: A review of insights from mercury stable isotopes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 9182–9195 (2022).

Masbou, J. et al. Hg stable isotope time trend in ringed seals registers decreasing sea ice cover in the Alaskan Arctic. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 8977–8985 (2015).

Cai, H. & Chen, J. Mass-independent fractionation of even mercury isotopes. Sci. Bull. 61, 116–124 (2016).

Jiskra, M. et al. Mercury stable isotopes constrain atmospheric sources to the ocean. Nature 597, 678–682 (2021).

Araujo, B. F. et al. Mercury isotope evidence for Arctic summertime re-emission of mercury from the cryosphere. Nat. Commun. 13, 4956 (2022).

Masbou, J. et al. Hg-stable isotope variations in marine top predators of the western Arctic Ocean. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2, 479–490 (2018).

Jiskra, M., Sonke, J. E., Agnan, Y., Helmig, D. & Obrist, D. Insights from mercury stable isotopes on terrestrial-atmosphere exchange of Hg(0) in the Arctic tundra. Biogeosciences 16, 4051–4064 (2019).

Renedo, M. et al. Contrasting spatial and seasonal trends of methylmercury exposure pathways of arctic seabirds: combination of large-scale tracking and stable isotopic approaches. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 13619–13629 (2020).

Sonke, J. E. et al. Mercury stable isotope composition of lichens and mosses from northern eurasia reveals Hg deposition pathways and sources. ACS Earth Space Chem. 7, 204–211 (2023).

Cable, S., Christiansen, H. H., Westergaard-Nielsen, A., Kroon, A. & Elberling, B. Geomorphological and cryostratigraphical analyses of the Zackenberg Valley, NE Greenland and significance of Holocene alluvial fans. Geomorphology 303, 504–523 (2018).

Cooke, C. A., Martínez-Cortizas, A., Bindler, R. & Gustin, M. S. Environmental archives of atmospheric Hg deposition – A review. Sci. Total Environ. 709, 134800 (2020).

Olson, C. L., Jiskra, M., Sonke, J. E. & Obrist, D. Mercury in tundra vegetation of Alaska: Spatial and temporal dynamics and stable isotope patterns. Sci. Total Environ. 660, 1502–1512 (2019).

Li, C. et al. A peat core Hg stable isotope reconstruction of Holocene atmospheric Hg deposition at Amsterdam Island (37.8oS). Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 341, 62–74 (2023).

Perrot, V. et al. Higher mass-independent isotope fractionation of methylmercury in the pelagic food web of Lake Baikal (Russia). Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 5902–5911 (2012).

Laffont, L. et al. Anomalous mercury isotopic compositions of fish and human hair in the Bolivian Amazon. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 8985–8990 (2009).

Jiskra, M. et al. A vegetation control on seasonal variations in global atmospheric mercury concentrations. Nat. Geosci. 11, 244–250 (2018).

Driscoll, C. T., Mason, R. P., Chan, H. M., Jocab, D. J. & Pirrone, N. Mercury as a global pollutant: sources, pathways, and effects. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 4967–4983 (2013).

Horowitz, H. M. et al. A new mechanism for atmospheric mercury redox chemistry: implications for the global mercury budget. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 6353–6371 (2017).

Durnford, D., Dastoor, A., Figueras-Nieto, D. & Ryjkov, A. Long range transport of mercury to the Arctic and across Canada. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 6063–6086 (2010).

Søndergaard, J. et al. Mercury exports from a High-Arctic river basin in Northeast Greenland (74°N) largely controlled by glacial lake outburst floods. Sci. Total Environ. 514, 83–91 (2015).

Jørgensen, C. J. et al. Large mercury release from the Greenland Ice Sheet invalidated. Sci. Adv. 10, eadi7760 (2024).

Søndergaard, J., Riget, F., Tamstorf, M. P. & Larsen, M. M. Mercury transport in a low-Arctic River in Kobbefjord, West Greenland (64° N). Water Air Soil Pollut. 223, 4333–4342 (2012).

Münchow, A. & Falkner, K. K. Melling, H. Baffin Island and West Greenland current systems in northern Baffin Bay. Prog. Oceanogr. 132, 305–317 (2015).

Münchow, A. & Melling, H. Ocean current observations from nares strait to the west of Greenland: interannual to tidal variability and forcing. J. Mar. Res. 66, 801–833 (2008).

de Steur, L., Sumata, H., Divine, D. V., Granskog, M. A. & Pavlova, O. Upper ocean warming and sea ice reduction in the East Greenland current form 2003 to 2019. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 261 (2023).

Cossa, D. et al. Mercury distribution and transport in the North Atlantic Ocean along the GEOTRACES-GA01 transect. Biogeosciences 15, 2309–2323 (2018).

Bowman, K. L., Lamborg, C. H. & Agather, A. M. A global perspective on mercury cycling in the ocean. Sci. Total Environ. 710, 136166 (2020).

Ŝtrok, M., Baya, P. A. & Hintelmann, H. The mercury isotope composition of Arctic coastal seawater. Cr. Geosci. 347, 368–376 (2015).

Du, J. & Hesp, P. A. Salt spray distribution and its impact on vegetation zonation on coastal dunes: a review. Estuar. Coast. 43, 1885–1907 (2020).

Malcolm, E. G. et al. Experimental investigation of the scavenging of gaseous mercury by sea salt aerosol. J. Atmos. Chem. 63, 221–234 (2009).

Huang, S. et al. Oceanic evasion fuels Arctic summertime rebound of atmospheric mercury and drives transport to Arctic terrestrial ecosystems. Nat. Commun. 16, 903 (2025).

Enrico, M. et al. Atmospheric mercury transfer to peat bogs dominated by gaseous elemental mercury dry deposition. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 2405–2412 (2016).

Steffen, A. et al. A synthesis of atmospheric mercury depletion event chemistry in the atmosphere and snow. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 8, 1445–1482 (2008).

Landry, J. J. et al. Feeding ecology of a common benthic fish, shorthorn sculpin (Myoxocephalus scorpius) in the high arctic. Polar Biol. 41, 2091–2102 (2018).

Siegsted, H., Neve, P. B., Heide-Jørgensen, M. P. & Härkönen, T. Diet of the ringed seal (Phoca hispida) in Greenland. NAMMCO Sci. Publ. 1, 229–241 (2014).

Yurkowski, D. J. et al. Influence of sea ice phenology on the movement ecology of ringed seals across their latitudinal range. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 562, 237–250 (2016).

Schmutz, J. A. & Hobson, K. A. Geographic, temporal, and age-specific variation in diets of glaucous gulls in Western Alaska. Condor 100, 119–130 (1998).

Lyngs, P. Migration and winter ranges of birds in Greenland. DOFT 97, 167 (2003).

McKinney, M. A. et al. Global change effects on the long-term feeding ecology and contaminant exposures of East Greenland polar bears. Glob. Chang. Biol. 19, 2360–2372 (2013).

Laidre, K. L. et al. Glacial ice supports a distinct and undocumented polar bear subpopulation persisting in late 21st-century sea-ice conditions. Science 376, 1333–1338 (2022).

Dietz, R., Overgaard, C. N., Hansen, M. M. & Hansen, C. T. Organic mercury in Greenland birds and mammals. Sci. Total Environ. 95, 41–51 (1990).

Pinzone, M. et al. Contamination levels and habitat use influence Hg accumulation and stable isotope ratios in the European seabass. Dicentrarchus Labrax. Environ. Poll. 281, 117008 (2021).

Dietz, R. et al. Unexpected Increases of Persistent Organic Pollutant and Mercury Levels in East Greenland Polar Bears (Unexpected) (Aarhus University, 2021).

Land-Miller, H. et al. Comparison of feeding niches between Arctic and northward-moving sub-Arctic marine mammals in Greenland. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 728, 163–182 (2024).

Lee, J. H. et al. Spatiotemporal characterization of mercury isotope baselines and anthropogenic influence in lake sediment cores. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 35, e2020GB00690 (2021).

Sun, R. et al. Historical (1850-2010) mercury stable isotope inventory from anthropogenic sources to the atmosphere. Elem. Sci. Anthr. 4, 000091 (2016).

Lim, A. G. et al. A revised pan-Arctic permafrost soil Hg pool based on Western Sibirian peat Hg and carbon observations. Biogeosciences 17, 3083–3097 (2020).

Vermilyea, A. W. et al. Continuous proxy measurements reveal large mercury fluxes from glacial and forested watersheds in Alaska. Sci. Total Environ. 599–600, 145–155 (2017).

Zdanowicz, C. et al. Snowmelt, glacial and atmospheric sources of mercury to a subarctic mountain lake catchment, Yukon, Canada. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 238, 374–393 (2018).

Chételat, J., Ackerman, J. T., Eagles-Smith, C. A. & Hebert, C. E. Methylmercury exposure in wildlife: a review of the ecological and physiological processes affecting contaminant concentrations and their interpretation. Sci. Total Environ. 711, 135117 (2020).

Kawai, T., Sakurai, T. & Suzuki, N. Application of a new dynamic 3-D model to investigate human impacts on the fate of mercury in the global ocean. Environ. Modell. Softw. 124, 104599 (2020).

AMAP. AMAP Assessment 2021: Mercury in the Arctic. https://www.amap.no/documents/doc/amap-assessment-2021-mercury-in-the-arctic/3581 (2021).

Seppälä, M. The origin of palsas. Geografiska Annaler. Ser. A, Phys. Geogr. 68, 141–147 (1986).

Sun, R., Enrico, M., Heimbürger, L.-E., Scott, C. & Sonke, J. E. A double-stage tube furnace-acid trapping protocol for the pre-concentration of mercury from solid samples for isotopic analysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 405, 6771–6781 (2013).

Yamakawa, A., Takeuchi, A., Shibata, Y., Berail, S. & Donard, O. F. X. Determination of Hg isotopic compositions in certified reference material NIES No. 13 human hair by cold vapor generation multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Accred. Qual. Assu. R. 21, 197–202 (2016).

Boertmann, D., Mosbech, A. (eds.). Eastern Baffin Bay - A Strategic Environmental Impact Assessment Of Hydrocarbon Activities. (https://www2.dmu.dk/Pub/SR9.pdf (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work received funds from the Danish Environmental Protection Agency (MST) for the project MINAMATA (grant no. 2020-64837; J.S.) to J.S., B.E., C.S., M.M.L. and R.D. and from the Carlsberg Foundation for the Thermo Neptune XT MC-ICP-MS instrument used for the Hg isotope analyses (grant no. CF19-0139; R.D.) to R.D. and J.S. MST provided funds for collections of the AMAP biota samples in connection with the Greenland AMAP Core biota program since 1994 (J. nr. 2022-86218; J.S.) to J.S., C.S. and R.D. Collection of the Greenland peat samples used in the study was supported by The Danish National Research Foundation (CENPERM DNRF100; B.E.) to B.E. The Ministry of Higher Education and Science in Denmark secured funds for development of new/improved analytical techniques/methods in support of a research-based management of the raw material extraction industry in Greenland to J.S. (appropriation under the Finance Act). Finally, the projects GREENPATH funded by the Danish National Research Foundation (grant no. 4258-00004B; R.D.), WHALEADAPT funded by New Frontiers in Research Fund, Canada (grant no. NFRFI-2023-00350; Melissa A. McKinney and R.D.) and ARCSOLUTION funded by the European Union (grant no. 101135051; Katrin Vorkamp and C.S.) provided resources for the authors (J.S., B.E., C.S. and R.D.) to conduct the work. Views and opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the funding institutions nor can the institutions be held responsible for them. The authors wish to thank Frank Farsø Rigét (retired) for leading the Greenland AMAP Core biota program between 2001 and 2022 and Marc Christian Allentoft-Larsen, Anders Galatius, Kasper Lambert Johansen, Jan Lorentzen, Hanne Sandell and local subsistence hunters in Ittoqqortoormiit, Qaanaaq and Qeqertarsuaq for their contributions to the AMAP Core biota programme as well as Anders Mosbech for advice and support. Ulla Kokfelt, Hans Frederik Engvej Hansen, Mathilde Hartung Bengtson and Maria Matthiesen are thanked for taking part in peat samplings. Laboratory technicians Sigga Johnsen, Sandra Drewes Fabricius, Cecilie Berg Carlé Nobel Zabel, Sabrina June Hvid and Anna Marie Plejdrup are acknowledged for their laboratory work related to the chemical analyses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization of the study was done by J.S., B.E., C.S. and R.D. Methodology was developed by J.S. and M.M.L. Investigations were carried out by J.S., B.E., C.S. and R.D. Funding acquisition was led by J.S. (MINAMATA, AMAP Core), R.D. (Carlsberg, GREENPATH, WHALEADAPT), C.S. (WHALEADAPT, ARCSOLUTION) and B.E. (CENPERM). Visualization was performed by J.S., who also led the paper writing. All author contributed to data interpretation and writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Gretchen Lescord who co-reviewed with Baylor Lynch, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Søndergaard, J., Elberling, B., Sonne, C. et al. Stable isotopes unveil ocean transport of legacy mercury into Arctic food webs. Nat Commun 16, 5135 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60356-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60356-6