Abstract

Cultural systems play an important role in shaping the interactions between humans and the environment, and are in turn shaped by these interactions. However, at present, cultural systems are poorly integrated into the models used by climate scientists to study the interaction of natural and anthropogenic processes (i.e. Earth systems models) due to pragmatic and conceptual barriers. In this Perspective, we demonstrate how the archaeology of climate change, an interdisciplinary field that uses the archaeological record to explore human-environment interactions, is uniquely placed to overcome these barriers. We use concepts drawn from climate science and evolutionary anthropology to show how complex systems modeling that focuses on the spatial structure of the environment and its impact on demographic variables, social networks and cultural evolution, can bridge the gap between large-scale climate processes and local-scale social processes. The result is a blueprint for the design of integrative models that produce testable hypotheses about the impact of climate change on human systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The archaeology of climate change is an interdisciplinary field that explores the relationship between humans and their environment1,2. The archaeological record is a source of richly contextualised information about past human societies that provides a means of calibrating climate models, tracking human impacts on the environment and generating narratives in support of contemporary efforts to adapt to climate change3. Furthermore, archaeology provides a wealth of case studies with which to generate novel hypotheses that can be quantitatively tested4. Given the resurgence of interest in climate change research, bridging the gap between climate science and archaeology has become a priority (e.g. refs. 3,5). In this Perspective, we examine the different theoretical frameworks used to study biophysical, biological and cultural systems in hominin species with well documented cultural transmission. We identify bridging concepts that integrate these frameworks into a single modelling pipeline capable of generating testable hypotheses about human-climate interactions at both macro and microevolutionary scales.

Historically, climate scientists have focussed on discovering and explaining apparent correlations between the timing of significant thresholds in human evolution and climate events6,7. Correlative approaches have yielded numerous hypotheses about the impact of climate events on patterns of hominin speciation and dispersal (Box 1). Establishing causal links between climate events and changes in the palaeontological and archaeological records remains a major challenge, however8,9,10. In many of the studies cited in Box 1, the synchroneity of climate events and evolutionary change is assumed to indicate causality7 and adaptation and genetic drift are inferred mechanisms. But the causal pathways between climate change and culturally significant events such as the domestication of plants and animals11,12 and the transition to farming13, for example, are not always clear. This hinders our ability understand how climate change acts on human systems and highlights the need for a more integrated, interdisciplinary approach to climate science. Climate scientists adopt a range of theoretical frameworks, however, some of which may appear to be unreconcilable. Building conceptual bridges between these frameworks is a requirement if climate science is to advance14,15.

In this Perspective, we break down the conceptual barriers between existing theoretical frameworks to create an integrative workflow for the study of human-climate interactions. We use a modelling approach, grounded in complex systems theory, and highlight the role of spatial context—defined here as the abundance, spatial distribution, and connectivity of environmental variables relevant to human populations—as the critical link between biophysical and cultural systems. We begin by reviewing key theoretical frameworks in climate science, highlighting where conceptual and disciplinary boundaries exist. We then show how ecological models (see: Species Distribution Models), used in conjunction with Cumulative Cultural Evolution (CCE) theory, bridge the gap between evolutionary and anthropological approaches. A key aspect of CCE is its demonstration that patterns of cultural transmission and innovation are affected by the structure of the environment, producing evolutionary change in human culture (‘all that individuals learn from others that endures to generate customs and traditions’16 p. 938). This leads us to make a concrete proposal (Building Integrative Models) for the design of complex models that reconcile existing theoretical frameworks, exploit available datasets from the Earth and Social sciences, do not require extensive computing resources and can be adapted for use in different cultural and spatiotemporal contexts to make predictions about human/climate interactions that are testable using the archaeological record and Earth archives.

Theoretical frameworks

Systems Theory is a useful, cross-disciplinary framework for modelling the complexities of climate/human interactions, but conceptually different approaches have been adopted within this framework. From an evolutionary perspective (see: Evolutionary Theory) adaptation is identified as the causal mechanism linking climate change to transformations in human systems and models tend to focus on macroevolutionary change. Models developed from an anthropological point of view (see: Anthropological Theory), on the other hand, focus on mechanisms of change arising from within human systems and are more attuned to microevolutionary processes. Although these approaches emphasise different causal mechanisms and scales of interaction, they are not incompatible. The difficulty lies in identifying bridging concepts that enable the design of complex, multiscalar models that integrate environmental and cultural systems.

Systems theory

Complex systems theory is the dominant framework in climate change research today. A construct of physics, biology and the social sciences17, it highlights the importance of interdisciplinarity, the emergent properties of complex systems and the importance of local interactions as drivers of global processes, concepts that resonate with climate change archaeology5,14. Earth Systems Science (ESS), a variant of systems theory widely adopted by climate modellers18 encourages the integration of human variables in climate change models19, something human vulnerability and mitigation studies (e.g. ref. 20,21) that now routinely include economic and demographic variables attempt. Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS), a counterpart to ESS, is more widely adopted in the social and natural sciences22,23. From a CAS perspective, culture is a dynamic, complex system that interacts with the biosphere and other biological systems22,24,25. This definition of culture is compatible with evolutionary theory, but it also raises questions about the extent to which the cultural system evolves in a manner analogous to the genetic system (Box 2). Although complex systems theory emphasizes interdisciplinary and multiscalar approaches, different theoretical frameworks have been used to develop models that, as a result, fail to integrate the full range of complexity that a true complex system model requires.

Evolutionary theory

Evolutionary theory integrates biophysical and biological systems and has obvious applications for climate change research, although it oftentimes lacks a clear articulation of the mechanisms that explain how microevolutionary change ends up shaping the macroevolutionary process. At its core, evolution implies the existence of (or potential for) adaptation. As a state, adaptation implies the possession of traits and behaviours that contribute to positive fitness; for example, heightened oxygen metabolism is a metabolic adaptation to high-altitude conditions in many mammals. As a process (a population undergoes adaptation in a given environment), adaptation is the family of mechanisms through which an adaptive state is reached, as the etymology (‘towards being fit’) suggests. Since Ernst Mayr’s work on speciation, the process of adaptation has been understood as the sequential, iterative application of the generation of diversity (through mutation, recombination, immigration, and gene flow) and the removal of some of this variation through selection.

In order to reframe evolutionary theory in the context of cultural evolution, it is important to generate an inventory of the mechanisms that drive evolutionary change. Classifying these mechanisms by whether they generate (mutation, recombination, gene flow) or filter (selection, drift) variability is a first step towards identifying analogues within the realm of cultural evolution. It is also important to consider whether these mechanisms operate at both microevolutionary and macroevolutionary scales. Even though macroevolution (which generates diversity above the species level) proceeds from microevolution (which occurs at the population level within species), there is no clear definition of the mechanisms and processes linking the two.

Cultural evolutionary theory applies evolutionary theory to the study of human systems (Box 2) on the grounds that culture, and the behavioural plasticity it provides, is a fitness-enhancing adaptation subject to natural selection (e.g. ref. 26). It has been argued, however, that cultural evolution is so fundamentally different from biological evolution that it cannot be meaningfully addressed within a Darwinian evolutionary framework27,28.

Most notably, differences between biological and cultural evolution, such as the mode of selection (Box 2), cast doubt on the primacy of external variables such as climate as drivers of cultural change. Whereas natural selection is a clearly defined mechanism that describes how environmental change drives the evolution of biological organisms, the cultural context in which cultural evolution occurs produces competing demands on the process of selection that are not fully accounted for in the modern Darwinian synthesis. Systems theory provides the framework within which these competing demands can be reconciled, provided we acknowledge that human systems are open, multiscalar systems influenced by both internal contexts and external influences (e.g. ref. 25).

The Extended Evolutionary Synthesis (ESS) takes a different approach, bridging the gap between biological and cultural systems by highlighting mutual feedback relationships between natural and cultural selection (e.g. ref. 29). Niche construction emphasises that non-random cultural changes affect the impact of environmental conditions on individuals and societies and may thereby drive biological evolution by changing the context of ‘natural’ selection30. However, while ESS accounts for some aspects of cultural change within evolutionary theory, broadly speaking it has not addressed the accumulative nature of material culture production in human societies31, nor does it provide clear explanatory mechanisms32,33. Models produced from this perspective, therefore, will still fall short of being fully integrated.

Anthropological theory

In Anthropology and its sister discipline Archaeology, ontological thinking competes with ecological approaches. Twentieth-century postmodernists rejected evolutionary theory as a suitable framework for the study of cultural variation and social transformation, the implication being that natural and human systems should be studied in isolation. Under the influence of thinkers such as Gibson34 and Bateson35, however, a more holistic view of human beings as both biological and social organisms has emerged as an alternative to the Cartesian dualism that previously dominated Western thought. From this perspective, cultural variation is the result of individual agency and the complex web of relations, organic and inorganic, within which agents are situated36. This approach is compatible with systems theory but repositions the study of material culture at the centre of the archaeology of climate change, highlighting both the necessity and the challenge of reconciling two very different, but potentially complementary, theoretical approaches.

The archaeology of climate change

The archaeology of climate change harnesses the analytical power of species distribution models (SDMs) to study the impact of past climate events on the spatial behaviour of human populations (e.g. refs. 37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45). Much of this research focusses on the impact of biophysical processes on the spatial distribution of human populations and patterns of dispersal, inferred to be causally linked by adaptation. Cultural change is typically addressed after the modelling process is complete, using inferential arguments to draw links between climate shifts and chronologically correlated cultural patterns8. This is partly a result of a tendency for environmental archaeologists and human ecologists interested in macroevolutionary processes to gravitate towards environmental data and ecological models. Among the latter, the proponents of cumulative cultural evolution (CCE) adopt a demographic focus, examining the impact of population structure (demography) on rates and patterns of cultural change. Archaeologists interested in microevolutionary processes at local or regional scales, on the other hand, tend to adopt a more qualitative, historical approach to the study of human-environment interactions.

We argue, as others have before us15, that by adopting a unified approach and bridging the gaps between environmentally based, demographic and historical approaches, the archaeology of climate change can solve what is currently a major stumbling block in climate science: the design of complex models that integrate Earth and human systems effectively and can be used to study their interactions at micro and macroevolutionary scales, producing hypotheses that can be tested using the archaeological record and Earth archives. This is made possible by integrating CCE models and SDMs.

Cumulative culture models

Cumulative cultural evolution (CCE), a concept that flows from cultural evolution theory (Box 2), emphasises the accumulation of variation over time, often described in terms of an increase in the complexity of material culture46. For example, what started as simple stone flaking accumulated changes over generations resulting in the development of compound projectile weapons with long production sequences combining many materials. Cumulative culture may be more broadly construed in terms of an increasing richness of cultural traits within a population, i.e. more types of tools or greater stylistic variability47,48. Put simply, CCE can be equated with the ‘standing on the shoulders of giants’ metaphor for scientific progress; the incremental advances made by any given scientist are made possible only by the wealth of scholarship that has gone before. Similarly, cultural evolution occurs only when culturally inherited traits undergo incremental improvement before being transmitted to future users, who can themselves add further innovation. While it is not uniquely human (e.g. refs. 49,50), cumulative culture is a key adaptation of our lineage51.

The CCE literature is extensive but it tends to focus on the internal (i.e., social and cognitive) mechanisms of innovation, transmission, and selection at the expense of operationalized measures that reflect alterations to artefact form or assemblage variability (but see in refs. 52,53). More promising for our purposes is its focus on population density, mobility, and connectivity, as these spatial parameters can be directly conditioned by climatic and environmental changes. Larger populations are expected to produce more innovation per unit time (since per capita innovation rate is viewed as a constant), and both formal models and simulations demonstrate that greater population density and more mobility increase rates of transmission, since both lead to higher encounter rates between individuals or groups54,55. Connectivity also regulates rates of cultural evolution since large ‘culturally panmictic’ populations may generate more variation per unit time, but they may also suppress new innovations54,56. Structured or ‘partially connected’ populations, by contrast, maintain both cultural diversity and a sufficiently large overall population to sustain high innovation rates. The cultural trajectories of sub-populations partially isolated by the fragmentation of areas of suitable habitat following climatic and environmental change may diverge, with periodic contact between them facilitating the spread and combination of any beneficial variants that arise in individual demes (see also56,57,58). The archaeological record reveals spatially explicit patterns of cultural production59 confirming a link between climate change, the structure of the environment and patterns of cultural transmission. Models of cultural evolution are rarely spatially explicit, however (e.g. ref. 60) hindering their integration with palaeocological and archaeological models.

Species distribution models

In contrast to models of cultural evolution, Species Distribution Models (SDMs) use spatially explicit environmental variables to estimate the distribution and size of habitable ‘patches’ (see below). The resulting models can then be used to predict chronological trends in population size and connectivity, offering the possibility of measuring the impact of climate change. SDMs are well placed, therefore, to bridge the gap between models of cultural evolution and climate change.

Since their introduction in 198461, ecology has seen a constant increase in the use of SDMs (also known as habitat suitability models, or ecological niche models), of which the most frequently used are presence-only models like Maximum Entropy, or more flexible presence-absence models such as Generalised Linear Models (GLM) and tree-based methods (including Random Forest and Boosted Regression Trees)62. The typical SDM pipeline begins with the selection and preparation of observation data and environmental variables in a geographic information system to produce a feature class (observations) and a stack of spatially continuous coverages describing a set of environmental variables (predictors). The distribution of values in the environmental variables at locations where presences are recorded is used to characterise ‘suitable’ environmental conditions relative to background locations. Depending on the specific model used to predict habitat suitability, these background locations can be drawn at random or based on the distance to known observations63. The resulting models can be projected onto geographical space, mapping the distribution of suitable habitat on a scale of 0 to 1 (1 being the optimal set of conditions), which can be further thresholded to reflect discrete categories of habitat suitability64. SDMs can be combined into ensemble models65, although simulation studies highlight that this does not always improve model quality66.

Global climate models typically operate at spatial resolutions of ~150 km, which is suitable for tracking macroevolutionary processes over large spatial domains. A range of statistical and machine learning techniques is available for increasing the spatial resolution of global climate models to scales more suitable for tracking microevolutionary processes67, including short-term patterns of mobility and subsistence. Finally, SDMs describe the relationship between species distributions and the physical environment, but whether they describe a species’ fundamental niche, its realised niche, or only some niche components is debatable68 and depends very much on how the model is specified and whether functionally relevant environmental variables were selected.

Archaeological applications use archaeological sites as records of human presence (observations) and paleoclimate variables (e.g. temperature, precipitation) in conjunction with other abiotic variables (e.g. topographic variables) as the predictors. SDMs require ecological variables with high spatial coverage, which means that climate models, rather than reconstructions based on climate proxies such as pollen counts, are the most suitable source of climate data. Sources of simulated paleoclimate data are increasingly available for past timeframes69,70,71,72,73.

One of the dangers of a modelling approach is misspecification, i.e., either ignoring data that can’t readily be quantified or using data based on availability74. Many, if not most, archaeological SDMs use a restricted set of variables, ignoring biotic factors such as the presence of competitors, for example. SDMs also assume an equilibrium state which may or may not be appropriate, although rather than increasing the error in the model, non-equilibrium presences tend to provide conservative estimates of the distribution75. Despite these restrictions, existing models provide useful insights into the distribution of suitable habitat and its components under different climate regimes at regional or continental scales. Most fall short of providing a full explanation of how climate change affects the cultural system, however. The explanatory power of SDMs can be improved by developing testable hypotheses that address the question of causality prior to the modelling process, e.g. by introducing relevant variables into the modelling stream and testing them using a variable selection protocol (e.g. refs. 37,76).

Contemporary techniques in species distribution modelling help ensure that models are transferable to new environments. For example, proper use of cross-validation leads to more transferability when habitat selection rules can be assumed to be stable77 although some species-specific features decrease model transferability, e.g. decreased longevity or strong differences in the response to topographic relief and elevation78, these are relevant in multi-species assessments and are not evidence that transferability is not possible, a priori. The largest cross-species comparison of transferability to date79, although limited to tree species, provides important lessons applicable to other taxa, including humans. First, although transferability issues may arise regardless of the algorithm used—which suggests that transferability is bounded by the species being predicted—the situation is improved systematically by representing habitat suitability as a quantitative (rather than binary) response. Second, although transferability can decrease when finer-scale environmental layers are coarsened to match the scale of bioclimatic variables80, the use of downscaling techniques to increase the resolution of bioclimatic variables, as our workflow suggests, confers protection against low transferability. In what follows, we explore the conceptual gap between SDMs designed, for the most part, to gauge the impact of climate change on the spatial behaviour of past human populations, and models of cultural transmission.

Building integrated models: a workflow

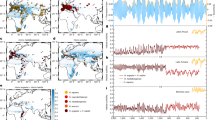

In this Perspective, we propose an integrative modelling chain (Fig. 1, Box 3) that explicitly uses the spatio-temporal structure of the environment to bridge the gap between climate-informed SDMs and models of cultural evolution. We recommend involving climate scientists from different disciplines (e.g. paleoclimatologists, ecologists and archaeologists) in the model design process to ensure that archaeologically relevant variables are identified prior to running the models to address the issue of causality. Furthermore, by adopting complex systems science as the overall theoretical framework of the analysis, we highlight the importance of fine-grained archaeological analyses of the material culture record and the role of social context and historical contingency in determining the final outcome of human-environment interactions.

The first step in any modelling process is to identify a research question, timeframe and spatial domain for which palaeoenvironmental and archaeological data are available. This step dictates the relevant spatial and temporal scales of the model. Next, a set of environmental variables (e.g. drawn from climate models or digital terrain models) is selected and prepared using a GIS (Fig. 1: phase 1). The preselection of environmental variables should consider the scale of the model and be grounded in theory to ensure that relevant variables are being tested. Climate data with sufficiently comprehensive spatial coverage are usually the products of general circulation models (AOGCMs). Archaeological sites serve as proxies for human presence (the dependent variable) and are selected, controlling for locational and chronological accuracy. One or more modelling techniques (e.g. MaxEnt, Random Forest, Boosted Regression Trees, GLM) are then selected to identify patterns in the distribution of sites relative to environmental variables and make predictions about the relationship between human presence and the physical environment68 (Fig. 1: phase 2, top). A stepwise procedure can be used to select relevant variables from the pool of candidate predictors during the modelling process, avoiding some of the misspecification errors mentioned above and providing a means of testing hypotheses81,82. Once a numerical model of habitat suitability is produced, it can be projected onto geographic space and visualised (Fig. 1: phase 2, bottom).

In the following step (Fig. 1: phase 3, top), landscape connectivity and ecological network analyses developed in conservation science can be used to quantify the location and size of clusters of suitable habitat and the degree to which they are spatially connected83,84. A variety of tools are currently available for implementing these analyses as standalone productions, in R or in GIS environments85. Ethnographic and archaeological data can be used to establish the statistical parameters of the models, e.g. the expected range of mobility and the minimum area of core regions, identified using the suitable habitat model, tailoring the analysis to the scale and timeframe of interest. These landscape metrics can, in turn, be used to predict demographic variables such as group size based on habitable area (e.g. refs. 86,87) and the density of interactions between human groups using parameters set forth in CCE models (e.g. ref. 88).

The next step in the pipeline is to use CCE theory to predict higher-order cultural processes, such as rates of cultural innovation, the probability of transmission of novel traits and their retention at the level of the metapopulation (Fig. 1: phase 3, bottom). Climate change events are linked to changes in habitat structure that influence the demographic structure of human populations, which, in turn, is used to generate testable predictions about the material culture record. There is no circularity because the SDM is generated from locations and environmental variables, whereas the resulting predictions concerning cultural change will be tested using finer-grained aspects of the archaeological record (e.g. assemblage variability)89 (Fig. 1: phase 4, top).

Up to this point, the proposed pipeline attributes causality to the adaptive process and is well-suited to predicting climate-driven macroevolutionary change (e.g. speciation and patterns of dispersal), demographic patterns and higher-level processes governed by them (e.g. rates of cultural innovation and cultural transmission). Depending on model design and the criteria used to select variables, culturally relevant hypotheses (e.g. the degree of sensitivity to climate variability) may also be tested. The pipeline is not isotropic and feedback mechanisms between cultural and natural systems (e.g. anthropogenic impacts on vegetation cover90) can be incorporated into the modelling process using feedback loops91, providing input for the land surface component of GCMs, for example72 (Fig. 1: linking phases 3 and 4).

What the proposed pipeline cannot do is predict specific forms of cultural expression (the appearance of given ‘cultural traits’), nor can it explain why a given climate event can have unpredictable outcomes15. This level of detail is a product of historical contingency and random, non-linear relationships between the internal (social) and external (natural) variables that constitute the system. Archaeological, ethnographic and historical records provide valuable information about the nature and timing of the fundamental processes that contribute to the emergence of culturally specific properties of the system, e.g. the existence of social inequality, levels of violence, shifting political allegiances, etc. Full integration of human systems into Earth systems models, therefore, requires the compilation of detailed and highly contextualised archaeological and paleoenvironmental information that can be used to disentangle climate change impacts and local-scale cultural processes3 and careful consideration of the quality and scale of available data used7 (Fig. 1: phase 4).

Finally, it is possible to see how the proposed workflow (Fig. 2) could be expanded and adapted (Box 3). Case studies drawn from the archaeological and palaeontological records (e.g. refs. 8,92) generate hypotheses that can be incorporated into initial model design and quantitatively tested. Analogue methodologies involving the use of individual narratives to generate testable hypotheses have been developed by geographers studying the human dimensions of climate change4. Agent-based models93 can be added to the workflow, e.g. to calculate the probability that a series of small-scale interactions might transform the overall system under specific test conditions.

The pipeline is integrative, multiscalar and anisotropic. Climate models and Species distributions models (SDM) produce spatially explicit models of the distribution of human habitat. Cumulative cultural evolution (CCE) links habitat structure and transformations in the cultural system, generating hypotheses that can be tested using the archaeological record and Earth archives.

Conclusion

In this Perspective, we propose a blueprint for the design of complex models that overcome existing barriers in climate model design and generate predictions about human-climate interactions that are testable using the archaeological record and Earth archives. Climate models and climate change archaeology have been accused of environmental determinism94,95,96 as a result of a historically top-down approach to causality3,97 and over-emphasis of the role of readily identifiable and easily quantifiable climate variables as drivers of ecological and social change15,74. This potential bias can be overcome by improving the integration of human systems in Earth systems models5,14,19,23,74, grounding the modelling process in theory15 and generating predictions that can be tested using the archaeological, palaeontological and paleoenvironmental records8,98. The proposed pipeline produces an integrated workflow grounded in systems theory that articulates climate-driven SDMs, CCE-derived models of cultural evolution and contextualised, fine-grained analyses of human systems and the material culture record.

In addition to reconciling existing theoretical frameworks, our proposed modelling pipeline is achievable. Environmental and archaeological datasets covering a range of timeframes and geographic locations are now readily available and extensive computing resources, beyond those already in use in most universities and laboratories, are not required. This Perspective, therefore, illustrates how the archaeology of climate science can use existing resources to design fully integrated complex systems models that contribute to climate science and can inform contemporary climate action by providing richly contextualised case studies that demonstrate how past human populations reacted to climate change events and document the outcomes.

References

Boivin, N. & Crowther, A. Mobilizing the past to shape a better Anthropocene. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1–12 (2021).

Burke, A. et al. The archaeology of climate change: the case for cultural diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2108537118 (2021).

Kohler, T. A. & Rockman, M. The IPCC: a primer for archaeologists. Am. Antiquity 85, 627–651 (2020).

Ford, J. D. et al. Case study and analogue methodologies in climate change vulnerability research. WIREs Clim. Change 1, 374–392 (2010).

Little, J. C. et al. Earth systems to anthropocene systems: an evolutionary, system-of-systems, convergence paradigm for interdependent societal challenges. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 5504–5520 (2023).

Blockley, S. In Handbook of Archaeological Sciences 151–158 (2023).

Behrensmeyer, A. K. Climate change and human evolution. Science 311, 476–478 (2006).

Faith, J. T. et al. Rethinking the ecological drivers of hominin evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 36, 797–807 (2021).

Coombes, P. & Barber, K. Environmental determinism in Holocene research: causality or coincidence. Area 37, 303–311 (2005).

Degroot, D. et al. The history of climate and society: a review of the influence of climate change on the human past. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 103001 (2022).

Larson, G. et al. Current perspectives and the future of domestication studies. PNAS 111, 6139–6146 (2014).

Zeder, M. A. Core questions in domestication research. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 3191–3198 (2015).

Bellwood, P. First Farmers: the Origins of Agricultural Societies (John Wiley & Sons, 2023).

Newell, B. et al. A conceptual template for integrative human–environment research. Glob. Environ. Change 15, 299–307 (2005).

White, S. & Pei, Q. Attribution of historical societal impacts and adaptations to climate and extreme events: integrating quantitative and qualitative perspectives. Glob. Chang. 28, 44–45 (2020).

Whiten, A., Hinde, R. A., Laland, K. N. & Stringer, C. B. Culture evolves. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 366, 938–948 (2011).

Thurner, S., Hanel, R. & Klimek, P. Introduction to the Theory of Complex Systems (Oxford University Press, 2018).

Steffen, W. et al. The emergence and evolution of Earth System Science. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 54–63 (2020).

Beckage, B., Moore, F. C. & Lacasse, K. Incorporating human behaviour into Earth system modelling. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 1493–1502 (2022).

Ford, J. et al. The resilience of Indigenous peoples in the face of environmental change and societal pressures. One Earth 2, 532–543 (2020).

Brklacich, M. & Bohle, H.-G. In Earth System Science in the Anthropocene (eds Eckart E. & Thomas K.) 51–61 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2006).

Lansing, J. S. Complex adaptive systems. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 32, 183–204 (2003).

Reed, P. M. et al. Multisector dynamics: advancing the science of complex adaptive human-earth systems. 10, e2021EF002621. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EF002621 (2022).

Barton, C. M. Complexity, social complexity, and modeling. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 21, 306–324 (2014).

Davis, D. S. Past, present, and future of complex systems theory in archaeology. J. Archaeol. Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10814-023-09193-z (2023).

Mesoudi, A., Whiten, A. & Laland, K. N. Perspective: is human cultural evolution Darwinian? Evidence reviewed from the perspective of the origin of species. Evolution 58, 1–11 (2004).

Boone, J. L. & Alden-Smith, E. Is it evolution yet? A critique of evolutionary archaeology. Curr. Anthropol. 39, 141–174 (1998).

Prentiss, A. M. Theoretical plurality, the extended evolutionary synthesis, and archaeology. 118, e2006564118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2006564118 (2021).

Stock, J. T., Will, M. & Wells, J. C. K. The extended evolutionary synthesis and distributed adatation in the Genus Homo. Phenotypic plasticity and behavioral adaptability. Palaeoanthropology 2, 205–233 (2023).

Laland, K., Matthews, B. & Feldman, M. W. An introduction to niche construction theory. Evolut. Ecol. 30, 191–202 (2016).

O’Brien, M. J. & Lala, K. N. Culture and evolvability: a brief archaeological perspective. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 30, 1079–1108 (2023).

Spengler, R. N. Niche construction theory in archaeology: a critical review. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 28, 925–955 (2021).

Riede, F. In Handbook of Evolutionary Research In Archaeology 337–358 (Springer, 2019).

Gibson, J. In Perceiving, Acting, and Knowing: Towards an Ecological Psychology (eds Shaw, R. & Bransford, J.) 127–143 (Lawrence Erlbaum., 1979).

Bateson, G. Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology. 535 (Jason Aronson Inc., 1972).

Ingold, T. The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling & Skills (Routledge, 2000).

Burke, A. et al. Risky business: the impact of climate and climate variability on human population dynamics in Western Europe during the Last Glacial Maximum. Quat. Sci. Rev. 164, 217–229 (2017).

Timmermann, A. & Friedrich, T. Late Pleistocene climate drivers of early human migration. Nature 538, 92–95 http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v538/n7623/abs/nature19365.html#supplementary-information (2016).

Timmermann, A. Quantifying the potential causes of Neanderthal extinction: abrupt climate change versus competition and interbreeding. Quat. Sci. Rev. 238, 106331 (2020).

Banks, W. E. et al. An ecological niche shift for Neanderthal populations in Western Europe 70,000 years ago. Sci. Rep. 11, 5346 (2021).

Banks, W. E., d’Errico, F., Peterson, A. T., Kageyama, M. & Colombeau, G. Reconstructing ecological niches and geographic distributions of Rangifer tarandus and Cervus elaphus during the LGM. Quat. Sci. Rev. 27, 2568–2575 (2008).

Benito, B. M. et al. The ecological niche and distribution of Neanderthals during the Last Interglacial. J. Biogeogr. 44, 51–61 (2017).

Ludwig, P., Shao, Y. P., Kehl, M. & Weniger, G. C. The last glacial maximum and Heinrich Event I on the Iberian Peninsula: a regional climate modelling study for understanding human settlement patterns. Glob. Planet. Change 170, 34–47 (2018).

Melchionna, M. et al. Fragmentation of Neanderthals’ pre-extinction distribution by climate change. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 496, 146–154 (2018).

Pedersen, J. B., Maier, A. & Riede, F. A punctuated model for the colonisation of the late glacial margins of northern Europe by Hamburgian hunter-gatherers. Quartär 65, 85–104 (2019).

Richerson, P. J. & Boyd, R. In Perspectives in Ethology: Evolution, Culture, and Behavior (eds Tonneau F. & Nicholas S. T.) 1–45 (Springer US, 2000).

Buchanan, B., O’Brien, M. J. & Collard, M. Drivers of technological richness in prehistoric Texas: an archaeological test of the population size and environmental risk hypotheses. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 8, 625–634 (2016).

Morin, O. Reasons to be fussy about cultural evolution. Biol. Philos. 31, 447–458 (2016).

Gunasekaram, C. et al. Population interconnectivity shapes the distribution and complexity of chimpanzee cumulative culture. Science 386, 920–925 (2024).

Dean, L. G., Vale, G. L., Laland, K. N., Flynn, E. & Kendal, R. L. Human cumulative culture: a comparative perspective. 89, 284–301 (2014).

Hill, K., Barton, M. & Hurtado, A. M. The emergence of human uniqueness: characters underlying behavioral modernity. Evol. Anthropol. Issues News Rev. 18, 187–200 (2009).

Eerkens, J. W. & Lipo, C. P. Cultural transmission, copying errors, and the generation of variation in material culture and the archaeological record. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 24, 316–334 (2005).

Derex, M. Human cumulative culture and the exploitation of natural phenomena. 377, 20200311. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0311 (2022).

Powell, A. & Thomas, M. Late pleistocene demography and the appearance of modern human behavior. Science 324, 1298–1301 (2009).

Grove, M. Population density, mobility, and cultural transmission. J. Archaeol. Sci. 74, 75–84 (2016).

Derex, M., Perreault, C. & Boyd, R. Divide and conquer: intermediate levels of population fragmentation maximize cultural accumulation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 373, 20170062 (2018).

Derex, M. & Mesoudi, A. Cumulative cultural evolution within evolving population structures. Trends Cogn. Sci. 24, 654–667 (2020).

Derex, M. & Boyd, R. Partial connectivity increases cultural accumulation within groups. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 2982–2987 (2016).

Bruxelles, L. & Jarry, M. Climatic conditions, settlement patterns and cultures in the Paleolithic: the example of the Garonne Valley (southwest France). J. Hum. Evol. 61, 538–548 (2011).

Demps, K., Herzog, N. M. & Clark, M. From mind to matter: patterns of innovation in the archaeological record and the ecology of social learning. Am. Antiq. 89, 19–36 (2024).

Booth, T. H., Nix, H. A., Busby, J. R. & Hutchinson, M. F. bioclim: the first species distribution modelling package, its early applications and relevance to most current MaxEnt studies. 20, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12144 (2014).

Norberg, A. et al. A comprehensive evaluation of predictive performance of 33 species distribution models at species and community levels. 89, e01370 (2019).

Broussin, J., Mouchet, M. & Goberville, E. Generating pseudo-absences in the ecological space improves the biological relevance of response curves in species distribution models. Ecol. Model. 498, 110865 (2024).

Liu, C., Newell, G. & White, M. On the selection of thresholds for predicting species occurrence with presence-only data. Ecol. Evol. 6, 337–348 (2016).

Drake, J. M. Ensemble algorithms for ecological niche modeling from presence-background and presence-only data. Ecosphere 5, art76 (2014).

Hao, T., Elith, J., Lahoz-Monfort, J. J. & Guillera-Arroita, G. Testing whether ensemble modelling is advantageous for maximising predictive performance of species distribution models. Ecography 43, 549–558 (2020).

Legasa, M. N., Thao, S., Vrac, M. & Manzanas, R. Assessing three perfect prognosis methods for statistical downscaling of climate change precipitation scenarios. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL102525 (2023).

Elith, J. & Leathwick, J. R. Species distribution models: ecological explanation and prediction across space and time. 40, 677–697. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120159 (2009).

Valdes, P. J. et al. The bridge hadCM3 family of climate models: HadCM3@Bristol v1.0. Geosci. Model Dev. 10, 3715–3743 (2017).

Yun, K. S. et al. A transient coupled general circulation model (CGCM) simulation of the past 3 million years. Clim Past 19, 1951–1974 (2023).

Leonardi, M., Hallett, E. Y., Beyer, R., Krapp, M. & Manica, A. pastclim 1.2: an R package to easily access and use paleoclimatic reconstructions. Ecography 2023, e06481 (2023).

Boucher, O. et al. Presentation and evaluation of the IPSL-CM6A-LR climate model. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, e2019MS002010. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019MS002010 (2020).

Armstrong, E., Tallavaara, M., Hopcroft, P. O. & Valdes, P. J. North African humid periods over the past 800,000 years. Nat. Commun. 14, 5549 (2023).

Degroot, D. et al. Towards a rigorous understanding of societal responses to climate change. Nature 591, 539–550 (2021).

Václavík, T. & Meentemeyer, R. K. Equilibrium or not? Modelling potential distribution of invasive species in different stages of invasion. Diver. Distrib. 18, 73–83 (2012).

Burke, A. et al. Exploring the impact of climate variability during the Last Glacial Maximum on the pattern of human occupation of Iberia. J. Hum. Evol. 73, 35–46 (2014).

Gantchoff, M. G. et al. Distribution model transferability for a wide-ranging species, the Gray Wolf. Sci. Rep. 12, 13556 (2022).

Rousseau, J. S. & Betts, M. G. Factors influencing transferability in species distribution models. Ecography 2022, e06060 (2022).

Charney, N. D. et al. A test of species distribution model transferability across environmental and geographic space for 108 western North American tree species. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9, https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2021.689295 (2021).

Manzoor, S. A., Griffiths, G. & Lukac, M. Species distribution model transferability and model grain size – finer may not always be better. Sci. Rep. 8, 7168 (2018).

Fox, E. W. et al. Assessing the accuracy and stability of variable selection methods for random forest modeling in ecology. Environ. Monit. Assess. 189, 316 (2017).

Genuer, R., Poggi, J.-M. & Tuleau-Malot, C. Variable selection using random forests. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 31, 2225–2236 (2010).

Baguette, M., Blanchet, S., Legrand, D., Stevens, V. M. & Turlure, C. Individual dispersal, landscape connectivity and ecological networks. 88, 310–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12000 (2013).

McRae, B. H., Dickson, B. G., Keitt, T. H. & Shah, V. B. Using circuit theory to model connectivity in ecology, evolution and conservation 89, 2712–2724. https://doi.org/10.1890/07-1861.1 (2008).

Dutta, T., Sharma, S., Meyer, N. F. V., Larroque, J. & Balkenhol, N. An overview of computational tools for preparing, constructing and using resistance surfaces in connectivity research. Landsc. Ecol. 37, 2195–2224 (2022).

Ordonez, A. & Riede, F. Changes in limiting factors for forager population dynamics in Europe across the last glacial-interglacial transition. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–13 (2022).

Schmidt, I. et al. Approaching prehistoric demography: proxies, scales and scope of the Cologne Protocol in European contexts. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 376. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0714 (2021).

Timmermann, A., Wasay, A. & Raia, P. Phase synchronization between culture and climate forcing. Proc. R. Soc. B 291, 20240320. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2024.0320 (2024).

Garvey, R. Current and potential roles of archaeology in the development of cultural evolutionary theory. 373, 20170057. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0057 (2018).

Kaplan, J. O., Pfeiffer, M., Kolen, J. C. & Davis, B. A. Large scale anthropogenic reduction of forest cover in last glacial maximum Europe. PLoS ONE 30, e0166726 (2016).

Donges, J. F. et al. Closing the loop: reconnecting human dynamics to Earth System science. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 4, 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053019617725537 (2017).

Scheffer, M., van Nes, E. H., Bird, D., Bocinsky, R. K. & Kohler, T. A. Loss of resilience preceded transformations of pre-Hispanic Pueblo societies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2024397118 (2021).

Romanowska, I., Wren, C. D. & Crabtree, S. A. Agent-Based Modeling For Archaeology: Simulating the Complexity of Societies (SFI Press, 2021).

Riede, F. Environmental determinism and archaeology. Red flag, red herring. Archaeol. Dialogues 26, 17–19 (2019).

Judkins, G., Smith, M. & Keys, E. Determinism within human–environment research and the rediscovery of environmental causation. Geography. J. 174, 17–29 (2008).

Blaut, J. M. Environmentalism and Eurocentrism: A Review Essay (2000).

Nielsen, J. Ø & Sejersen, F. Earth System Science, the IPCC and the problem of downward causation in human geographies of Global Climate Change. Geografisk Tidsskr. Dan. J. Geogr. 112, 194–202 (2012).

Barton, C. M., Riel-Salvatore, J., Anderies, J. M. & Popescu, G. Modeling human ecodynamics and biocultural interactions in the late Pleistocene of western Eurasia. Hum. Ecol. 39, 705–725 (2011).

Quinn, R. L. et al. Influences of dietary niche expansion and Pliocene environmental changes on the origins of stone tool making. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 562, 110074 (2021).

Maslin, M. A. et al. East African climate pulses and early human evolution. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 101, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.06.012 (2014).

Vallverdú, J. et al. Age and date for early arrival of the Acheulian in Europe (Barranc de la Boella, la Canonja, Spain. PLoS ONE 9, e103634 (2014).

Gosling, W. D., Scerri, E. M. L. & Kaboth-Bahr, S. The climate and vegetation backdrop to hominin evolution in Africa. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 377, 20200483 (2022).

Müller, U. C. et al. The role of climate in the spread of modern humans into Europe. Quat. Sci. Rev. 30, 273–279 (2011).

Richerson, P. J., Boyd, R., and Bettinger, R. L. Was agriculture impossible during the Pleistocene but mandatory during the Holocene? A Climate Change Hypothesis. Am. Antiq. 66 (2001).

Weninger, B. et al. Climate forcing due to the 8200 Cal yr BP event observed at early neolithic sites in the eastern mediterranean. Quat. Res. 66, 401–420 (2006).

Vrba, E. S. Environment and evolution: alternative causes of the temporal distribution of evolutionary events. South Afr. J. Sci. 81, 229–236 (1985).

White, T. D. African omnivores: global climatic change and Plio-Pleistocene hominids and suids. In Paleoclimate and Evolution, with Emphasis on Human Origins (eds Virba, E. S., Denton, G. H., Partridge, T. C. & Burckle, L. H.) 369–384 (Yale University Press, 1994).

Grove, M. Change and variability in Plio-Pleistocene climates: modelling the hominin response. J. Archaeol. Sci. 38, 3038–3047 (2011).

Potts, R. Evolution and climate variability. Science 273, 922–923 (1996).

Potts, R. & Faith, T. Alternating high and low climate variability: the context of natural selection and speciation in Plio-Pleistocene hominin evolution. J. Hum. Evol. 87, 5–20 (2015).

Potts, R. et al. Increased ecological resource variability during a critical transition in hominin evolution. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc8975 (2020).

deMenocal, P. B. Climate and human evolution. Science 331, 540–542. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1190683 (2011).

Trauth, M. H., Larrasoaña, J. C. & Mudelsee, M. Trends, rhythms and events in Plio-Pleistocene African climate. Quat. Sci. Rev. 28, 399–411 (2009).

Grove, M. Palaeoclimates, plasticity, and the early dispersal of Homo sapiens. Quat. Int. 369, 17–37 (2015).

Carotenuto, F. et al. Venturing out safely: The biogeography of Homo erectus dispersal out of Africa. J. Hum. Evol. 95, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.02.005 (2016).

Beyer, R. M., Krapp, M., Eriksson, A. & Manica, A. Climatic windows for human migration out of Africa in the past 300,000 years. Nat. Commun. 12, 4889 (2021).

Beyin, A. Upper Pleistocene human dispersals out of Africa: a review of the current state of the debate. Int. J. Evol. Biol. 2011, 615094. https://doi.org/10.4061/2011/615094 (2011).

Henrich, J. & McElreath, R. In Oxford Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology (eds Barrett L. & Dunbar R.) (Oxford University Press, 2007).

Whiten, A. Culture extends the scope of evolutionary biology in the great apes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 7790–7797 (2017).

Whitehead, H., Laland, K. N., Rendell, L., Thorogood, R. & Whiten, A. The reach of gene–culture coevolution in animals. Nat. Commun. 10, 2405 (2019).

Tëmkin I. & Eldredge N. Phylogenetics and material cultural evolution. Curr. Anthropol. 48, 146–154. https://doi.org/10.1086/510463 (2007).

Shennan, S. Evolution in archaeology. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 37, 75–91 (2008).

Henrich, J. Demography and cultural evolution: how adaptive cultural processes can produce maladaptive losses: the Tasmanian case. Am. Antiq. 69, 197–214 (2004).

Richerson, P. J. & Boyd, R. Not By Genes alone: How Culture Transformed Human Evolution (University of Chicago Press, 2008).

Smolla, M. et al. Underappreciated features of cultural evolution. 376, 20200259. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0259 (2021).

Muthukrishna, M., Morgan, T. J. H. & Henrich, J. The when and who of social learning and conformist transmission. Evol. Hum. Behav. 37, 10–20 (2016).

Kandler, A. & Laland, K. N. An investigation of the relationship between innovation and cultural diversity. Theor. Popul. Biol. 76, 59–67 (2009).

Godfrey-Smith, P. Darwinian Populations and Natural Selection (Oxford University Press, USA, 2009).

Henrich, J. & Boyd, R. The evolution of conformist transmission and the emergence of between-group differences. Evol. Hum. Behav. 19, 215–241 (1998).

Eriksson, K., Enquist, M. & Ghirlanda, S. Critical points in current theory of conformist social learning. J. Evol. Psychol. JEP 5, 67–87. https://doi.org/10.1556/jep.2007.1009 (2007).

Aplin, L. M. et al. Experimentally induced innovations lead to persistent culture via conformity in wild birds. Nature 518, 538–541. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13998 (2015).

Grove, M. In Human Success: Evolutionary Origins and Ethical Implications (eds Ramsey, G. & Desmond, H.) 144–159 (Oxford University Press, 2023).

Paquin, S. Les dispersions humaines en Europe au cours du stade isotopique marin 3 (MIS 3) et leurs conditions environnementales et climatiques Ph.D. thesis, Universite de Montreal, (2024).

Paquin, S., Albouy, B., Kageyama, M., Vrac, M. & Burke, A. Anatomically modern human dispersals into Europe during MIS 3: climate stability, paleogeography and habitat suitability. Quat. Sci. Rev. 330, 108596 (2024).

Dufresne, J.-L. et al. Climate change projections using the IPSL-CM5 Earth System Model: from CMIP3 to CMIP5. Clim. Dyn. 40, 2123–2165 (2013).

Farr, T. G. et al. The shuttle radar topography mission. Rev. Geophys. 45. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005rg000183 (2007).

Nikolakaki, P. A GIS site-selection process for habitat creation: estimating connectivity of habitat patches. Landsc. Urban Plan. 68, 77–94 (2004).

Collard, M., Buchanan, B., O’Brien, M. J. & Scholnick, J. Risk, mobility or population size? Drivers of technological richness among contact-period western North American hunter–gatherers. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 368, 20120412 (2013).

Maier, A. et al. Analyzing trends in material culture evolution—a case study of gravettian points from lower Austria and Moravia. J. Paleolithic Archaeol. 6, 15 (2023).

Vanhaeren, M. & d’Errico, F. Aurignacian ethno-linguistic geography of Europe revealed by personal ornaments. J. Archaeol. Sci. 33, 1105–1128 (2006).

Wren, C. D. & Burke, A. Habitat suitability and the genetic structure of human populations during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) in Western Europe. PLoS ONE 14, e0217996 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The support of the Fonds de Recherche du Québéc, Société et Culture (2019-SE3-254686) and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC #435-2016-1158) is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors actively contributed to the work presented in this Perspective, which was conceived during a multi-day workshop on the Archaeology of climate change. A.B., M.G., A.M., C.W., M.D. and T.P. wrote the paper, to which O.M., L.B. and S.B. contributed significantly. A.B., M.G., A.M., C.W. and S.B. provided Archaeological/Anthropological expertise, T.P. and M.D. contributed Ecological and Palaeoanthropological viewpoints, O.M. and L.B. provided insights from the Earth Sciences, O.M. and C.W. are responsible for graphic design.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Burke, A., Grove, M., Maier, A. et al. The archaeology of climate change: a blueprint for integrating environmental and cultural systems. Nat Commun 16, 5289 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60450-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60450-9

This article is cited by

-

The First Occupations of Western Europe: Dispersals and Population Dynamics in the Early to Middle Pleistocene

Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory (2026)