Abstract

Understanding the dynamics of marine dissolved organic carbon (DOC) is essential for predicting its role in carbon cycling and its response to climate change. Here, we unveil molecular transformations of marine chromophoric dissolved organic matter (CDOM) across the global ocean using Ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy. Significant variability in CDOM composition within the epi- and mesopelagic layers ( < 1000 m) correlates with physicochemical parameters, driven by irradiation, primary production, biological activity, transport, and riverine inputs. In the bathypelagic layer (1000–5000 m), up to 18.2% of highly conjugated molecules transform into low-molecular-weight CDOM, despite stable DOC concentrations. This dynamic process sustains biomass production and respiration in deep ocean, contributing a carbon flux of 3–24 Pg C yr−1—up to an order of magnitude more than the fast-sinking particulate organic carbon flux. Our findings offer insights into the molecular transformation of deep-ocean DOM and underscore the need to reassess the bathypelagic DOC pool’s role in the global carbon cycle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The world’s oceans fix ~53 Pg C yr−1 of atmospheric CO2 annually through photosynthesis in the sunlit layer1. A significant portion of this carbon is rapidly respired by marine microheterotrophs or oxidized via photochemical processes, recycling back to CO2 within the upper ocean. Only a small fraction (~1.5 Pg C yr−1) escapes mineralization and is transported into the bathypelagic layer (>1000 m)2,3. In view of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) account for more than 90% organic carbon4, extensive research has focused on the DOC cycle within the epipelagic and mesopelagic layers to unveil its contributions to the marine carbon cycle. DOC in the bathypelagic layer has often been presumed to be refractory and enough to be transported by ocean currents over thousands of years, inferred from apparent homogeneity and uniform DOC concentrations5. Consequently, the DOC cycle within the bathypelagic layer remains largely unaccounted for in current oceanic carbon cycling models3,6,7.

Despite the significant attenuation of particulate organic carbon (POC), which is produced in the euphotic layer and progressively remineralized as it sinks through the epipelagic and mesopelagic layers, leading to minimal POC availability in the deep ocean, high and relatively uniform bacterial and archaeal abundances have been observed throughout water columns in pelagic ecosystems, including the deep ocean. This raises the mystery of what fuels the abundant biomass production and respiration of bacteria and archaea in the deep ocean3,7,8,9. Earlier studies hinted at the potential for an overlooked DOC cycle in the deep ocean because the deep-ocean DOC pool contains significant amounts of bomb radiocarbon (14C) produced by nuclear weapons testing, equal to dissolved inorganic carbon levels. These high radiocarbon levels imply a turnover of only a few years or less for much of this surface-accumulated material, indicating that deep ocean DOC is a mixture of chemically distinct forms of carbon with varying radiocarbon ages (semi-labile and refractory fractions)5,10,11. Given that the bathypelagic layer holds around 72% of marine DOC, amounting to as much as 477 Pg C5, any evidence of DOC dynamics in this layer is crucial for reassessing the global carbon cycle and predicting the ocean’s response to increasing atmospheric CO2 and climate change.

Since most fractions of DOC are chromophoric (colored dissolved organic matter, CDOM), ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) absorption spectroscopy provides a sensitive and cost-effective method for analyzing the molecular characteristics of CDOM, and can also act as a proxy for certain DOC properties12,13. However, marine CDOM spectra generally feature a nearly exponential decline in absorbance from ultraviolet to visible wavelengths, reflecting its nature as a complex mixture of organic molecules. Despite extensive use, UV-Vis spectral analyses have not fully elucidated the specific mechanisms of optical signals and intrinsic properties of CDOM due to limitations in defining exact molecular structures, with relationships between spectral parameters and CDOM properties largely empirical and region-specific14,15,16,17,18,19,20.

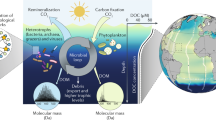

In order to gain insight into and quantify the molecular information conveyed by CDOM spectra, we developed a comprehensive spectral parameter profile across the Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic Oceans. This approach provides a detailed view of the vertical and spatial distribution patterns of marine CDOM from the surface to the deep ocean. Our findings offer perspectives on the gradients in CDOM driven by distinct water mass origins, chemical properties, and variability in organic matter composition. These gradients in CDOM breakdown are not merely chemical phenomena—they would profoundly impact the biological realm and biogeochemical dynamics, including the cycling of carbon, nitrogen, sulfur, and other elements in the dark ocean. Based on these insights, we propose the stepped microbe-DOM loop (SMDL) model to predict CDOM turnover time and flux in the deep ocean. This understanding is crucial for accurately assessing the ocean’s role in the global biogeochemical cycle, particularly regarding carbon storage, cycling, and broader implications for climate change.

Results and discussions

Parametrization of CDOM spectra in oceans

Marine CDOM UV-Vis spectra are typically characterized by three Gaussian bands (A1, A2, and A3) located approximately at 203, 258, and 327 nm, respectively13,21, along with two additional bands (B1 and B2) at around 305 and 410 nm, which are specific to deep-ocean and terrestrial CDOM, respectively (see Methods). To provide a comprehensive spectral profile for CDOM, six UV-Vis spectral parameters—ag(275), ag(380), B1’, B2’, S275-295, and S380-443—were introduced. The vertical distribution patterns of these parameters in the central Pacific Ocean (150°W) are shown in Fig. 1.

ag(275) reflects the intensity of Band A2, primarily associated with aromatic compounds (AC) such as benzene derivatives and heterocyclic structures (e.g., pyrroles and pyridines), as well as compounds with more extended conjugated structures21. ag(275) values are higher at high latitudes (>40°N) and lower in the Southern Hemisphere mesopelagic zone (20°S–60°S) and subtropical surface waters22. ag(380) represents the intensity of Band A3, linked to aromatic compounds with a styrene-like core (ACSC) characterized by C=C bonds conjugated to benzene rings, such as caffeic acid, rosmarinic acid, and more extended aromatic structures like naphthalene21. ag(380) values peak in the meso- and bathypelagic layers of the Southern Hemisphere and are lower in the epipelagic and subtropical mesopelagic zones. S275-295 and S380-443 represent the spectral slopes that capture the root mean square (RMS) width of Bands A2 and A3, respectively, indicating heterogeneity within these bands21. S275-295 is steeper in the sunlit surface waters of subtropical Southern Hemisphere regions22, whereas S380-443 remains relatively uniform, except in the upper Northern Hemisphere layers.

B1’ reflects the intensity of Band B1, associated with CHO compounds rich in C=C, C=O, and COO− functional groups, typically formed through DOM oxidation and ring opening in deep-ocean environments23,24,25,26. B1’ values rise sharply near the lower mesopelagic boundary, with high values in the meso- and bathypelagic layers, especially in the Northern Hemisphere. B2’ corresponds to molecules represented by Band B2, which exhibit more extensive conjugated structures than ACSC, resulting in a lower energy gap between the molecular orbitals involved in electron transitions, leading to redshifted absorption27. B2’ values are higher in the upper Northern Hemisphere layers.

The vertical distribution patterns of these spectral parameters in the eastern Indian Ocean (Fig. S2) and central Atlantic Ocean (Fig. S3) generally resemble those in the Pacific. However, the Atlantic shows greater heterogeneity. These distributions reveal distinct depth-related DOM characteristics across ocean basins, providing insights into the molecular composition, transformation, and age of DOM within the water column.

Global pattern of CDOM dynamics

The distributions of spectral parameters strongly correlate with physicochemical parameters on a global scale (Figs. S1–S3). In the central Pacific and eastern Indian Oceans, eight distinct spectroscopic provinces (SPs) can be identified, while ten SPs are found in the central Atlantic Ocean (see Methods). These SPs align closely with classical biogeochemical provinces (BPs) in the Pacific and Indian Oceans but exhibit more divergence in the Atlantic (Fig. 2).

In the central Pacific Ocean, the epipelagic zone (<200 m) is primarily composed of SP2, SP5, and SP7. These regions generally exhibit low nutrient levels of N, P, and others, which limits biological activity and production, as indicated by low B1’ values (Fig. 1). SP5 and SP7, located in tropical and subtropical areas, experience year-round solar radiation, and photobleaching converts ACSC-like into AC-like compounds characterized by higher S275–295 values and lower ag(380) values22. Both SP7 and BP7 exhibit characteristics of an ocean desert, primarily due to the nutrient-poor conditions of the Pacific Subtropical Gyre. High B2’ values in the Northern Hemisphere are due to terrestrial CDOM input. In the epipelagic layer, substantial variability in molecular composition and DOC (Fig. S4) is primarily driven by light exposure, primary production, lateral transport, and riverine inputs.

The mesopelagic zone (200–1000 m) in the Pacific Ocean mainly comprises three SPs: SP3, SP4, and SP6. These regions receive limited solar radiation, slowing the conversion from ACSC-like to AC-like compounds, and reducing S275-295 values (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1). High concentrations of inorganic nutrients (e.g., N and P) in this zone promote microbial activity and enhance DOC mineralization and CDOM transformation (Fig. S4), increasing in B1’ values (Fig. 1)28,29. SP3, located near Antarctica, is influenced by Subantarctic Mode Water (SAMW) and Antarctic Intermediate Water (AAIW), with low ag(275) and ag(380) values and high S275–295 values (Fig. 1). SP4, spanning latitudes from 0° to 50°N, exhibits a crescent-shaped distribution and aligns geographically with BP4. Here, strong biological activity leads to oxygen depletion and high values of B1’, ag(275), and ag(380), indicating the fragmentation of marine snow and the production of high-aromatic-content CDOM. SP6 acts as a transitional zone between SP2 and SP4, with intermediate values across all spectral parameters.

DOC concentration in the mesopelagic zone follows the Martin Curve with varying attenuation coefficients (k) (Fig. S5a)30. The molecular dynamics of CDOM in this zone are largely influenced by DOC attenuation and associated microbial activity. B1’ correlates positively with k, whereas S275-295 correlates negatively (Fig. S5b). Higher B1’ values indicate regions with more intense microbial activity, as supported by a strong linear relationship between B1’ and apparent oxygen utilization (AOU) across the three oceans (Fig. S6). Lower S275-295 values in these regions suggest a greater in situ production of AC-like compounds by microbial activity.

The bathypelagic zone (>1000 m) comprises two SPs: SP1 and SP8. Both are influenced by the lower circumpolar deep water (LCDW) from Antarctica, resulting in similar physicochemical properties across these regions (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1). The bathypelagic layer holds a high concentration of nutrients, which promotes microbial activity, particularly in the upper layers (1000–3000 m), where B1’ values peak. Influx from SP4, driven by a salinity gradient, contributes to elevated ag(275) and ag(380) values in SP8. Overall, ag(275), ag(380), and B1’ values are slightly higher in the Northern Hemisphere than in the Southern Hemisphere, leading to the division of the deep ocean into two SPs. While physicochemical parameters in the bathypelagic zone show little regional variability, the SPs still reveal important distinctions.

In the Indian Ocean, the CDOM dynamics are similar to those in the Pacific, with the epipelagic layer dominated by SP6, SP7, and SP8. SP6, near the Asian continental shelf, shows high ag(275) and ag(380) values due to terrestrial input (Fig. S2). SP7 and SP8, located at tropical and subtropical regions, received intense sunlight, resulting in higher S275-295 and lower ag(380). SP8, positioned in the subtropical gyre, experienced low nutrient concentrations, which limit biological activity, leading to lower S380–443. In the mesopelagic layer, both SP4 and SP5 were influenced by SAMW and AAIW from the Southern Ocean, resulting in lower ag(275) and ag(380) values. But SP5 exhibits higher nutrient concentrations, leading to higher B1’ values. In the bathypelagic zone, SP1, SP2, and SP3 all showed lower values of S275-295 and higher B1’ values. SP1 is also characterized by high ag(275) and ag(380) values due to the input from SP5.

The dynamics of CDOM in the central Atlantic Ocean share similarities with those in the Pacific and Indian Oceans. In the upper ocean, sunlight irradiation leads to higher values of S275–295 and lower values of ag(275) and ag(380) (Fig. S3). In the deep ocean, higher nutrient concentrations result in higher B1’ values. The presence of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) promotes efficient vertical mixing, leading to fragmented and overlapping distributions of SPs.

CDOM dynamics in the bathypelagic layer

In the bathypelagic layer, spectral parameters only show subtle variations on a global scale (Figs. 1, S2, and S3), which is consistent with the apparent homogeneity suggested by relatively uniform DOC concentrations. However, closer examination reveals that CDOM in these ancient waters is still subject to ongoing biochemical processes (Fig. S7). In the Pacific and Indian Oceans, there is minimal change in DOC (<1.3%), typically with gradients less than 0.4% per kilometer from 1000 to 5000 m. However, significant and consistent changes in ag(380)/DOC are observed at rates of 18.2 and 13.1%, respectively, with average gradients of ~3.9 and ~2.0% per kilometer from 1000 to 5000 m; except for two key regions: the bottom of the mesopelagic layer in the Southern Hemisphere (20°S–60°S) and near the seafloor (Fig. 3). In the Southern Hemisphere mesopelagic layer, DOC transported by Antarctic currents undergoes microbial degradation resulting in negative gradients of DOC and positive gradients of ag(380)/DOC. At the seafloor level, resuspension and intense biological activity significantly impact both DOC concentration and composition. The uniform gradients of ag(380)/DOC indicate a gradual conversion process from ACSC-like compounds to AC-like and low-molecular-weight (LMW) compounds with depth. This is further supported by the gradients of S380-443 (Fig. S8). The positive values of d(S380–443)/d(depth) below 1000 m reflect a reduction in Band A3 width due to the continuous consumption of ACSC-like compounds. It is noteworthy that the relatively small and inconsistent changes in d(ag(275)/DOC)/d(depth) (Fig. 3) and d(S275–295)/d(depth) (Fig. S8) suggest more complex transformations in A2-related substances, especially in the Indian and Atlantic Oceans. Additionally, the gradient of B1’/DOC shows a clear positive trend in the upper deep ocean (Fig. S8), indicating that nutrient-rich environments support biological activity and the production of B1-represented substances. However, these substances degrade rapidly at intermediate depths, with d(B1’/DOC)/d(depth) turning negative at depths greater than 2,000 meters. A rapid decrease in d(B2’/DOC)/d(depth) in upper layers suggests that larger conjugated structures break down quickly in B2-represented substances.

a–c The Pacific Ocean. d–f The Indian Ocean. g–i The Atlantic Ocean. a, d, g d(DOC)/d(depth) (L μmol L−1 km−1). b, e, h d(ag(275)/DOC)/d(depth) (L μmol−1 km−1 m−1). c, f, i d(ag(380)/DOC)/d(depth) (L μmol−1 km−1 m−1). The left graph in each panel depicts the average ratio of gradient (RG), which quantifies the percentage of degradation in DOC or spectral parameters that would occur with a decrease in depth with unit 1 km.

The Atlantic exhibits significantly different trends of DOC and spectral parameter gradients, likely due to the influence of the strong AMOC. The observed gradients in the Pacific and Indian Oceans cannot be explained by density diffusion, which is several orders of magnitude weaker (data not shown).

Deep ocean molecular transformations

We propose that the gradient patterns of spectral parameters and DOC in the deep ocean are primarily governed by the stepped microbe-DOM loop (SMDL), as illustrated in Fig. 4. In the upper deep ocean, bacteria and archaea consume high-molecular-weight (HMW) macromolecules to build biomass and release LMW extracellular substances such as polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and DNA, resulting in an obvious decrease the intensity of Bands A3 (ag(380)/DOC) and a slight increase/decrease intensity of Bands A2 (ag(275)/DOC), which change consistently with depth (Fig. 3). This transformation extends further, likely leading to even smaller molecules, such as sugars and proteins. Extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) and viral lysis of these microorganisms compensate for some DOC consumption, resulting in little change in overall DOC concentrations, while DOM is in a state of constant molecular flux; meanwhile, suspended and slow-sinking particles (<40 m d−1) form through the aggregation of microbes, detritus, fecal pellets, and other organic particles7,31. As slow-sinking particles transport deeper, they continue to fuel microbial activity7,32,33. During the SMDL, high-energy macromolecules are consumed, producing LMW33,34. This process plays a critical role in shaping deep-ocean DOM distribution and sustaining microbial life across various depths. The balance of nutrient limitation, cell detachment, mortality, and sinking rates maintains the ecological food web in the deep ocean3,7,8,9.

In the upper deep ocean, bacteria and archaea consume macromolecules to build biomass. Suspended and slow-sinking particles form through the aggregation of microbes, detritus, fecal pellets, and other organic particles. As slow-sinking particles transport organic material to greater depths, they continue to fuel microbial activity. During the SMDL, high-energy macromolecules are consumed, producing low-molecular-weight extracellular substances. In this figure, POC stands for particulate organic carbon, LMW for low-molecular-weight, MMW for medium-molecular-weight, HMW for high-molecular-weight, agg for aggregation, disagg for disaggregation, and EPS for extracellular polymeric substances.

Historically, deep-ocean DOM was considered recalcitrant, persisting for millennia due to its molecular properties35,36. However, significant amounts of bomb radiocarbon found in the deep-ocean DOC pool suggest that deep-ocean DOC is a mixture of chemically distinct carbon fractions of varying ages5,10,11. Recent studies suggest that DOM recalcitrance is not an intrinsic property of individual molecules, but rather emerges as a bulk property at the ecosystem level35,37,38. The debate surrounding deep-ocean DOM dynamics is complicated by the uniformity of DOC concentrations and the lack of apparent compositional distinction5. This study demonstrates a clear distinction of deep marine DOM at a molecular level. Notably, the vertical gradients of UV-Vis spectral parameters reveal clear trends from HMW to LMW compounds in the deep ocean (Fig. 3).

The breakdown of macromolecules via SMDL is not just a chemical phenomenon—they may profoundly impact the biological realm. One major enigma is the energy source for the huge biomass production and respiration of bacteria and archaea in the deep ocean, where marine snow from the euphotic zone has mostly attenuated in the epi- and mesopelagic layers3,7,8,9. The stepwise degradation of macromolecules in DOM can provide a steady energy source for microbial communities, supporting a relatively uniform distribution of microbial biomass with depth7,9.

This process aligns with globally consistent relationships observed between biomass across the epi-, meso-, and bathypelagic layers and net primary production (NPP) and consistent vertical gradient of ag(380)/DOC (Fig. 3), underscoring the critical link between surface productivity and deep-ocean energy availability32. For instance, bathypelagic biomass increases significantly, from approximately 200 mg C m−2 d−1 in oligotrophic regions to about 800 mg C m−2 d−1 in mesotrophic regions32.

The structure of DOM molecules—and the associated energy release—affects microbial trophic levels at various depths39,40. Observed shifts in prokaryotic communities and increased archaeal abundance with depth underscore the link between DOM and microbial trophic dynamics7,9,41. Concurrently, rising 15N isotopic signatures in microbes and POC with depth indicate accumulation of nitrogen in DOM cycling41,42,43.

The mortality and aggregation of microbes in the deep ocean generate significant amounts of slow-sinking and non-sinking particles44,45. Observations indicate that slow-sinking POC concentrations are one or two orders of magnitude higher than those of fast-sinking particles in the mesopelagic layer, with even more non-sinking POC present46,47. This suggests that most slow-sinking particles are produced in situ, rather than from fragmentation of fast-sinking particles7. Data from the Southern Ocean further support this hypothesis, showing that the contribution of slow-sinking POC to total flux increases with depth48. A strong correlation between microbial respiration and suspended POC highlights the essential role of buoyant particles in sustaining metabolic activity in the dark ocean7,49.

According to reported velocities of slow-sinking particles (3–22.2 m d−1)46,47 and spectral parameter gradients (Fig. 3), the turnover time of ag(380)-represented substances ranges from 3 to 30 years (see Methods). Specifically, the turnover times in the Pacific and Indian Oceans are 3–20 and 4–30 years, respectively, and are 14–102 years in the Atlantic Ocean. The turnover time of ag(275)-represented substances spans from 67 to 495 years in the Pacific Ocean. These ages may be overestimated because SMDL can consume and produce simultaneously both HMW and LMW molecules, especially LMW, which complicates accurate turnover calculations for ag(275)-represented substances in the Indian and Atlantic Oceans (Fig. 3).

The SMDL would significantly enhance vertical carbon flux to the deep ocean. According to the downward flux of organic carbon via slow-sinking particles measured in epi- and mesopelagic layers, ranging from 23 to 186 mg C m−2 d-146,47, the SMDL could potentially transport 3–24.5 Pg C yr−1 to the deep ocean, up to an order of magnitude greater than gravitational flux of POC from surface production, estimated at 1.5 Pg C yr−13. This calculation does not account for POC fragmentation or fast-sinking particles generated within the SMDL.

The SMDL’s flux potentially reconciles the gap between the supply of sinking POC and the organic carbon demand in deep-ocean microbial communities3,7,31,50. With microbial respiration in the bathypelagic zone estimated at 1.3–1.6 Pg C yr−1, and upper bounds reaching 18.0–20.4 Pg C yr−1, passive POC sinking alone is insufficient for sustaining bathypelagic microbial populations3,32. Even at its highest flux estimates, POC could only support half of the observed respiration3. Dark ocean chemolithoautotrophy, fueled by reduced compounds like ammonia, sulfide, hydrogen, and iron, supports some biomass8, but its magnitude cannot be of the same order of magnitude as heterotrophic biomass production7,8,51,52. Our findings highlight DOC’s critical role as a substrate source within the SMDL, contributing significantly to the carbon budgets in the deep ocean3,53,54.

In conclusion, this study profiles CDOM distributions across the global ocean using UV-Vis spectral parameters, underscoring the essential role of microbial DOC cycling in the oceanic carbon cycle in the deep ocean. In the absence of photosynthesis, alternative energy sources such as POC from upper ocean layers and in situ chemosynthesis alone cannot fully support the extensive deep-ocean microbial communities. Instead, microbial degradation of DOC provides a consistent energy source, enhancing the stability and diversity of these populations and maintaining a balanced nutrient cycle despite the lack of fresh organic inputs. This process shapes the ecosystems of the deep ocean.

Traditional oceanic carbon cycling models have primarily focused on surface processes like photosynthesis, terrestrial inputs, and physical mixing. Our findings reveal that deep-ocean DOC undergoes more rapid and dynamic cycling than previously recognized, driven by the SMDL. This process extends into upper ocean layers where large populations of bacteria and archaea exist, yet it remains largely unaccounted for in current models3,6,7. Incorporating DOC recycling into global carbon cycle models is crucial for accurately representing the ocean’s capacity for carbon turnover and sequestration, thereby refining predictions of carbon fluxes and climate feedback mechanisms.

Methods

Data source

Data were collected from the Climate Variability and Predictability (CLIVAR) program along the P16 (2005–2006), I8/I9 (2007), and A16 (2005)–A20/A22 (2003) lines (locations detailed in Fig. S9). DOC records were sourced from the Hansell/Carlson DOC datasets, accessible at [http://yyy.rsmas.miami.edu/groups/biogeochem/Data.html]. UV-Vis spectral data were provided by Norman B. Nelson. Physicochemical parameters, including temperature, salinity, oxygen, nitrate, phosphate, and silicate, were retrieved from the Global Ocean Data Analysis Project (GLODAP) database at [https://glodap.info/]. To align the spectral data with physicochemical parameters, records from CLIVAR lines were matched based on the following criteria: spatial proximity within ±5 km, sampling time within ±1 h, and a relative depth difference not exceeding 5%.

UV-Vis spectra processing methods

The deconvolution of CDOM absorbance spectra (Fig. S10) was performed according to our previous study21 with the Curve Fitting Tool in MATLAB 2016b. Initially, we used only three bands to fit the CDOM spectra. Because the fitting process has multiple solutions, we restricted the maximum amplitude location of Bands A1, A2, and A3 to 6.0-6.3 eV (196.8–206.6 nm), 4.5–4.8 eV (258.3–275.6 nm), and 3.6–3.8 eV (326.3–344.4 nm), respectively. Because the spectral data on CLIVAR lines concern wavelengths >275 nm, in which the relative intensities of Band A1 were typically low (below 20% for most cases), extracting relevant information about Band A1 solely from the spectral data >275 nm was challenging and prone to errors. Therefore, based on statistical analysis, we postulated that the maximum position of Band A1 was at 6.2 eV (200.0 nm), with a root mean square width of 0.75 eV. Additionally, it was assumed that the amplitude of Band A1 was fivefold higher than that of ag(275) due to the well-established observation that ag(200) is typically five times larger than ag(275) in most spectra records. This approximation was then implemented in the further numerical fitting, and in most cases, R2 > 0.99 is obtained13,21.

For the wavelength ranges 295–330 nm and 400–420 nm, deviations between measured spectra and the three Gaussian-band model (Bands A1–A3) were modeled with two additional Gaussian bands, B1 and B2. The amplitude maxima positions of Band B1 and B2 were set as 4.00–4.10 eV (302.4–310.0 nm) and 2.95–3.10 eV (400.0–420.0 nm), respectively. Absorption coefficients were computed using Eq. (1)

where ag(λ) (m−1) is the Napierian absorption coefficient of CDOM at wavelength λ, A(λ) (dimensionless) is the absorbance at wavelength λ, and l is the path length of the spectrophotometric cell.

The spectral slope \({S}_{{\lambda }_{1}-{\lambda }_{2}}\) was determined using Eq. (2).

UV-Vis absorption spectra of CDOM are fairly well represented by three to five Gaussian distribution bands21 when analyzed against photon energy (eV), computed using by Eq. (3), with resultant spectra modeled by Eq. (4).

where Eoi (eV) is the band center, Aoi is the amplitude, and Wi is the RMS width.

To simplify, the intensity of Band B1 band B2 was computed using Eqs. (5)-(6).

where ag’(305) and ag’(410) represent the absorption coefficients at 305 and 410 nm in the exponentially declining spectra within the ranges 295–330 nm and 380–443 nm, respectively, as determined by Eqs. (7) and (8).

The DOC–normalized differential spectra (DAS) were computed using Eq. (9).

where ag(λ)i represents the absorption of the selected CDOM sample, DOCi denotes the DOC of the selected sample, ag(λ)ref signifies the absorption of the reference sample, and DOCref indicates the DOC of the reference sample.

Identification of spectroscopic and biogeochemical provinces of marine CDOM

Biogeochemical provinces were defined based on physicochemical parameters—temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, nitrate, phosphate, and silicate—as described in the literature55. Given the lack of particulate organic carbon flux and spatial variation in the deep sea, this factor was excluded from our analysis.

For classifying UV-Vis-derived spectroscopic provinces of marine CDOM, we organized the spectral parameters (ag(275), ag(380), S275-295, S380-443, B1’, and B2’) as a matrix, with each parameter standardized using Eq. (10).

where \(\bar{X}\) is the average, and σ is the standard deviation.

We divided the normalized data into several clusters using the k-means method56. Relevant calculations were run to retrieve between 2 and 50 clusters using the Euclidian distance approach. The times of repetition were set as 999. The ratio of the intra-class mean distance to inter-class mean distance was computed by Eq. (11).

where ui represents the central coordinates of class i, and d represents Euclidean distance. The elbow point in the relationship between the D and k functions represents the optimal value of k. All the work was done by MATLAB 2016b using custom scripts.

The computation of the DOC attenuation coefficient

DOC concentrations in the mesopelagic layer decreased vertically following the Martin Curve (Eq. (12)) in each spectroscopic province of the Pacific and Indian Oceans30.

where z is the selected depth, z0 is the referenced depth, \({{{DOC}}}_{z}\) is the DOC at depth z, \({{{DOC}}}_{{z}_{0}}\) is the DOC at depth z0, and k is referred as coefficient of attenuation.

The estimation of CDOM turnover time

The distances (h) at which the parameter values (P) of ag(275)/DOC and ag(380)/DOC decrease to zero were estimated using the average P at a depth of 1000 m (P1000) and the average gradient of d(P)/d(depth) between 1000 and 5000 m, as described in Eq. (13). The velocity of slow-sinking particles (v) was set to 3–22.2 m d−1, based on values reported in the literature46,47. The turnover time (t) of CDOM was then computed using Eq. (14).

Data availability

All data are available within the article, or available from the corresponding authors on request.

Code availability

All code-related methods described in this paper are provided within the article. For access to the code for data processing, please contact the corresponding author.

References

Johnson, K. S. & Bif, M. B. Constraint on net primary productivity of the global ocean by Argo oxygen measurements. Nat. Geosci. 14, 769–774 (2021).

Hansell, D. A. & Carlson, C. A. Localized refractory dissolved organic carbon sinks in the deep ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 27, 705–710 (2013).

del Giorgio, P. A. & Duarte, C. M. Respiration in the open ocean. Nature 420, 379–384 (2002).

DeVries, T. & Weber, T. The export and fate of organicmatter in the ocean: new constraints from combining satellite and oceanographic tracer observations. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 31, 535–555 (2017).

Hansell, D. A., Carlson, C. A., Repeta, D. J. & Schlitzer, R. Dissolved organic matter in the ocean: a controversy stimulates new insights. Oceanogr 22, 202–211 (2009).

Henson, S. A. et al. Uncertain response of ocean biological carbon export in a changing world. Nat. Geosci. 15, 248–254 (2022).

Herndl, G. J. & Reinthaler, T. Microbial control of the dark end of the biological pump. Nat. Geosci. 6, 718–724 (2013).

Middelburg, J. J. Chemoautotrophy in the ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L24604 (2011).

Heneghan, R. F. et al. The global distribution and climate resilience of marine heterotrophic prokaryotes. Nat. Commun. 15, 6943 (2024).

Follett, C. L., Repeta, D. J., Rothman, D. H., Xu, L. & Santinelli, C. Hidden cycle of dissolved organic carbon in the deep ocean. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 16706–16711 (2014).

Catalá, T. S. et al. Turnover time of fluorescent dissolved organic matter in the dark global ocean. Nat. Commun. 6, 5986 (2015).

Nelson, N. B. & Siegel, D. A. The global distribution and dynamics of chromophoric dissolved organic matter. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 5, 447–476 (2013).

Yan, M., Mo, S., Liu, Z. & Korshin, G. Absorptivity inversely proportional to spectral slope in CDOM. Environ. Sci. Technol. 59, 7156–7164 (2025).

Aurin, D., Mannino, A. & Lary, D. J. Remote sensing of CDOM, CDOM spectral slope, and dissolved organic carbon in the global ocean. Appl. Sci. 8, 2687 (2018).

Del Vecchio, R. & Blough, N. V. Spatial and seasonal distribution of chromophoric dissolved organic matter and dissolved organic carbon in the Middle Atlantic Bight. Mar. Chem. 89, 169–187 (2004).

Benner, R. & Kaiser, K. Biological and photochemical transformations of amino acids and lignin phenols in riverine dissolved organic matter. Biogeochemistry 102, 209–222 (2011).

Fichot, C. G. & Benner, R. The spectral slope coefficient of chromophoric dissolved organic matter (S275-295) as a tracer of terrigenous dissolved organic carbon in river-influenced ocean margins. Limnol. Oceanogr. 57, 1453–1466 (2012).

Osburn, C. L. et al. Optical proxies for terrestrial dissolved organic matter in estuaries and coastal waters. Front. Mar. Sci. 2 (2016).

Stedmon, C. A. & Nelson, N. B. in Biogeochemistry of Marine Dissolved Organic Matter (Second Edition) (eds Hansell, D. A. & Carlson, C. A.) Ch. 10 (Academic Press, 2015).

Yamamoto, K., De Vries, T., Siegel, D. A. & Nelson, N. B. Quantifying biogeochemical controls of open ocean CDOM from a global mechanistic model. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 129, e2023JC020691 (2024).

Yan, M. et al. A novel method to dynamically observe the three-dimensional global oceanic dissolved organic carbon reservoir. 02 February 2023, Preprint at Research Square (2023).

Helms, J. R. et al. Absorption spectral slopes and slope ratios as indicators of molecular weight, source, and photobleaching of chromophoric dissolved organic matter. Limnol. Oceanogr. 53, 955–969 (2008).

Guengerich, F. P. & Yoshimoto, F. K. Formation and cleavage of C–C bonds by enzymatic oxidation–reduction reactions. Chem. Rev. 118, 6573–6655 (2018).

Waggoner, D. C., Chen, H., Willoughby, A. S. & Hatcher, P. G. Formation of black carbon-like and alicyclic aliphatic compounds by hydroxyl radical initiated degradation of lignin. Org. Geochem. 82, 69–76 (2015).

Khatami, S., Deng, Y., Tien, M. & Hatcher, P. G. Formation of water-soluble organic matter through fungal degradation of lignin. Org. Geochem. 135, 64–70 (2019).

Waggoner, D. C., Wozniak, A. S., Cory, R. M. & Hatcher, P. G. The role of reactive oxygen species in the degradation of lignin derived dissolved organic matter. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 208, 171–184 (2017).

Scott, A. I. Interpretation of the Ultraviolet Spectra of Nature Products (Pergamon Press, 1964).

Yamashita, Y. & Tanoue, E. Production of bio-refractory fluorescent dissolved organic matter in the ocean interior. Nat. Geosci. 1, 579–582 (2008).

Meador, T. B. et al. Carbon recycling efficiency and phosphate turnover by marine nitrifying archaea. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba1799 (2020).

Martin, J. H., Knauer, G. A., Karl, D. M. & Broenkow, W. W. VERTEX: carbon cycling in the northeast Pacific. Deep-Sea Res. Pt. I 34, 267–285 (1987).

Baltar, F. et al. Significance of non-sinking particulate organic carbon and dark CO2 fixation to heterotrophic carbon demand in the mesopelagic northeast Atlantic. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L09602 (2010).

Hernández-León, S. et al. Large deep-sea zooplankton biomass mirrors primary production in the global ocean. Nat. Commun. 11, 6048 (2020).

Nguyen, T. T. H. et al. Microbes contribute to setting the ocean carbon flux by altering the fate of sinking particulates. Nat. Commun. 13, 1657 (2022).

Druffel, E. R. & Robison, B. H. Is the deep sea on a diet?. Science 284, 1139–1140 (1999).

Dittmar, T. et al. Enigmatic persistence of dissolved organic matter in the ocean. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 570–583 (2021).

Jiao, N. et al. Microbial production of recalcitrant dissolved organic matter: Long-term carbon storage in the global ocean. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 593–599 (2010).

Arrieta, J. M. et al. Dilution limits dissolved organic carbon utilization in the deep ocean. Science 348, 331–333 (2015).

Zakem, E. J., Cael, B. & Levine, N. M. A unified theory for organic matter accumulation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2016896118 (2021).

Zhao, Z. et al. Metaproteomic analysis decodes trophic interactions of microorganisms in the dark ocean. Nat. Commun. 15, 6411 (2024).

McParland, E. L. et al. Seasonal patterns of exometabolites depend on microbial functions in the oligotrophic ocean. Preprint at bioRxiv (2024).

Romero-Romero, S., González-Gil, R., Cáceres, C. & Acuña, J. L. Seasonal and vertical dynamics in the trophic structure of a temperate zooplankton assemblage. Limnol. Oceanogr. 64, 1939–1948 (2019).

Koppelmann, R., Böttger-Schnack, R., Möbius, J. & Weikert, H. Trophic relationships of zooplankton in the eastern Mediterranean based on stable isotope measurements. J. Plankton Res. 31, 669–686 (2009).

Broek, T. A. B. et al. Dominant heterocyclic composition of dissolved organic nitrogen in the ocean: a new paradigm for cycling and persistence. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2305763120 (2023).

Mouw, C. B., Barnett, A., McKinley, G. A., Gloege, L. & Pilcher, D. Phytoplankton size impact on export flux in the global ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 30, 1542–1562 (2016).

Kostadinov, T. S., Milutinović, S., Marinov, I. & Cabré, A. Carbon-based phytoplankton size classes retrieved via ocean color estimates of the particle size distribution. Ocean Sci. 12, 561–575 (2016).

Riley, J. et al. The relative contribution of fast and slow sinking particles to ocean carbon export. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 26, GB1026 (2012).

Giering, S. L. C. et al. High export via small particles before the onset of the North Atlantic spring bloom. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 121, 6929–6945 (2016).

Baker, C. A. et al. Slow-sinking particulate organic carbon in the Atlantic Ocean: magnitude, flux, and potential controls. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 31, 1051–1065 (2017).

Baltar, F., Aristegui, J., Gasol, J. M., Sintes, E. & Herndl, G. J. Evidence of prokaryotic metabolism on suspended particulate organic matter in the dark waters of the subtropical North Atlantic. Limnol. Oceanogr. 54, 182–193 (2009).

Uchimiya, M. et al. Balancing organic carbon supply and consumption in the ocean’s interior: evidence from repeated biogeochemical observations conducted in the subarctic and subtropical western North Pacific. Limnol. Oceanogr. 63, 2015–2027 (2018).

Reinthaler, T., van Aken, H. M. & Herndl, G. J. Major contribution of autotrophy to microbial carbon cycling in the deep North Atlantic’s interior. Deep Sea Res. Pt. II 57, 1572–1580 (2010).

Alonso-Sáez, L., Galand, P. E., Casamayor, E. O., Pedrós-Alió, C. & Bertilsson, S. High bicarbonate assimilation in the dark by Arctic bacteria. ISME J. 4, 1581–1590 (2010).

Burd, A. B. et al. Assessing the apparent imbalance between geochemical and biochemical indicators of meso- and bathypelagic biological activity: what the @$♯! is wrong with present calculations of carbon budgets?. Deep Sea Res. Pt. II 57, 1557–1571 (2010).

Alonso-González, I. J., Arístegui, J., Vilas, J. C. & Hernández-Guerra, A. Lateral POC transport and consumption in surface and deep waters of the Canary Current region: a box model study. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 23, GB2007 (2009).

Reygondeau, G. et al. Global biogeochemical provinces of the mesopelagic zone. J. Biogeogr. 45, 500–514 (2018).

Jain, A. K. Data clustering: 50 years beyond K-means. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 31, 651–666 (2010).

Acknowledgements

M.Y., S.M., Z.L., Y.H., C.Z., and H.W. received funding from the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52450013) and the Hainan Provincial Financial Support Project (No. 46000023T000000939334). We express our sincere gratitude to all contributors who have provided the DOC and absorption spectra data for their invaluable efforts in maintaining the SeaBASS and Hansell/Carlson DOC databases. We would also like to acknowledge Norman B. Nelson for providing spectral data generated during CLIVAR voyages, as well as Craig A. Carlson and David A. Siegel for their insightful comments and proofreading of past versions of this manuscript. Furthermore, we extend our thanks to the High-Performance Computing Platform of the Center for Life Science at Peking University for computing the theoretical absorbance of the model organic compounds.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Y. designed the research. S.M., Z.L., and Y.H. conducted the primary data analysis. S.M., C.Z., and H.W. performed the computation of the theoretical absorbance of the model organic compounds. The manuscript was written by S.M. and M.Y., with revisions made by N.H., G.K., and J.N.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Ruosha Zeng and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mo, S., Liu, Z., Hao, Y. et al. Unveiling ongoing biogeochemical dynamics of CDOM from surface to deep ocean. Nat Commun 16, 5202 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60510-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60510-0