Abstract

Southern-sourced Antarctic Intermediate Water (AAIW) and Subantarctic Mode Water (SAMW) are currently major sinks of atmospheric CO2. During the last deglaciation, atmospheric CO2 levels increased significantly during two specific time periods, Heinrich Stadial 1 (H1) ~18–14.6 ka BP (thousand years ago before present) and the Younger Dryas (YD) ~12.8–11.5 ka BP. Model simulation and proxy data studies suggest that AAIW/SAMW was crucial in explaining these changes during H1 and YD, but its variability and properties in the Southeast Pacific Ocean are still largely unknown. Here, we present records of benthic foraminiferal carbon isotopes, Mg/Ca-based water temperatures, paleosalinity reconstructions, and sortable silt mean grain size variations over the last 30 thousand years from Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) Site 1233, in the Southeast Pacific Ocean, which is bathed in AAIW/SAMW. Our proxy data suggest an increased northward circulation of high pCO2/ nutrient-enriched AAIW/SAMW during H1 and YD. Our data provides support for AAIW/SAMW as one of the important conduits for deglacial oceanic outgassing in the eastern equatorial Pacific upwelling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During the present global warming with vast human induced atmospheric CO2 increase, Antarctic Intermediate Water (AAIW) and Subantarctic Mode Water (SAMW) are major sinks for this anthropogenic CO21. These water masses are formed in the Southern Ocean in association with upwelling of nutrient enriched deep-water2,3. As these waters are undersaturated with respect to heightened atmospheric CO2 from anthropogenic sources, they absorb CO2 and transport it along with upwelled nutrients at intermediate depths towards low latitudes1,3. In the equatorial Pacific, significant parts of this oceanic stored CO2 at intermediate water depths enters the Equatorial Undercurrent by way of diapycnal mixing processes and surfaces decades after its entrainment in the high southern latitudes4,5. The eastern equatorial Pacific is one of the world’s major upwelling regions, where oceanic stored CO2 is released back into the atmosphere6,7.

Prior to the industrial revolution, the last deglaciation (~18–11 ka BP) is the most recent time in the Earth’s history when global atmospheric CO2 levels markedly increased by ~80 ppm along with an average global warming of 3–6 °C8,9. Deglacial CO2 increases took place during two short intervals, during ~18–14.5 ka BP known as Heinrich Stadial 1 (H1) and during ~12.8–11.5 ka BP known as the Younger Dryas (YD)8. In contrast to the modern, man-made atmospheric CO2 increase from emissions, this deglacial two-step increase in atmospheric CO2 resulted from Southern Ocean upwelling (and outgassing) of deep and “old” high pCO2 and nutrient-enriched water masses that had been isolated from the atmosphere for a long time10,11.

Several proxy-based studies including δ13C and radiocarbon activities (Δ14C) of planktonic and benthic foraminifera imply that AAIW/SAMW served as an important conduit of the glacial “old” high pCO2 water masses from the Southern Ocean toward the eastern Pacific tropical upwelling region and even further north6,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Indeed, during deglacial atmospheric CO2 rise high deglacial surface ocean pCO2 found in the eastern Pacific equatorial upwelling zone was proposed to partly originate from AAIW/SAMW6.

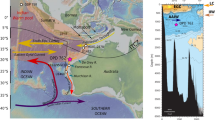

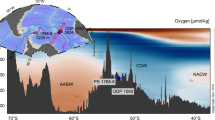

However, the hypothesis that AAIW/SAMW was an important conduit of “old” (high pCO2 and nutrient-enriched) water during the last deglaciation has yet to be rigorously tested in the Pacific Ocean. Offshore southern Chile, the deglacial AAIW/SAMW evolution (including temperature and salinity) is mostly unknown. Existing datasets for AAIW/SAMW ventilation are either far outside its modern core20 or are conflicting. For example, increased AAIW circulation was either suggested for the glacial or the deglaciation21,22, and AAIW as a main conduit of deglacial “old” water masses was rejected and later confirmed22,23,24. To fill this gap, we have developed multi proxy records of up to centennial scale (200 year resolution) from ODP Site 1233 (41°S; 74° 27’W) covering the last 30 kyrs. This Site is close to the major modern formation region of AAIW, which in this area is identical to the densest variety of SAMW2,25,26. Its water depth of 838 m puts it at the core of northward flowing AAIW/SAMW (Fig. 1a, b). Hence, we here refer to a combined AAIW/SAMW at our Site, since both water masses are indistinguishable using geochemical proxies27 and SAMW was proposed to be a major source for eastern Pacific AAIW28. We reconstructed AAIW/SAMW evolution using (1) benthic foraminiferal δ13C and Ba/Ca as indirect proxies for pCO2 contents and nutrients, (2) sortable silt mean grain sizes (\(\bar{{\mbox{SS}}}\)), a direct proxy for paleocurrent speeds and thereby changes in AAIW/SAMW northward flow, and (3) combined benthic δ18O and Mg/Ca which tracks changes in the AAIW/SAMW temperature and salinity (see Methods and Supplementary Discussion).

a Map showing core locations that are discussed in the eastern Pacific and the Drake Passage. b Oceanographic chart of the study area showing salinities (color shading) and oxygen contents (contour lines; in ml/l). The low salinity and high oxygen tongue of modern Antarctic Intermediate Water/ Subantarctic Mode Water (AAIW/SAMW) is indicated as well as Pacific Deep Water (PDW), Equatorial Subsurface Waters (ESSW), and Circumpolar Deep Water (CDW). Studied ODP core Site 1233 is displayed in red, other core sites are in white. Map and chart were created with ODV81, using data from World Ocean Atlas 2013 (ref. 82,83).

Results and Discussion

South Pacific AAIW/SAMW variability as one important conduit for CO2 increases in the eastern equatorial Pacific

During the last deglaciation our high-resolution benthic Uvigerina peregrina δ13C record (hereinafter referred to as benthic δ13C) was not affected by surface productivity changes (see Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary Fig. 1). The smoothed record shows a major decrease of ~1.2‰, followed by a second decrease of ~0.6‰ that principally track H1 and YD, when global atmospheric CO2 levels sharply increased (Fig. 2a, g) and atmospheric δ13C decreased by ~0.3‰, as recorded in Antarctic ice cores29 (Fig. 2a).

a Benthic δ13C from Site 1233 (black, thick line is a 3% weighted smooth made with Kaleidagraph 5.0) and Monte Carlo average of atmospheric δ13C from two Antarctic ice cores29 (red). b δ13C of N. dutertrei from Site 1238 (ref. 6; dark grey). c pCO2 reconstructions from Site 1238 (ref. 6; green) and Opal flux from V19-30 (ref. 33; dashed, brown). d Sortable silt mean grain size variations \((\bar{{\mbox{SS}}})\) (paleocurrent proxy) from Site 1233 (red, thick line is a 3% weighted smooth made with Kaleidagraph 5.0) and benthic Δ14C from Baja California sites16,18 (705 m water depths; dashed, blue). e Benthic-planktic 14C age difference from MD07-3088 (1536 m water depth; ref. 24; light blue). f Opal flux from the Pacific sector of the Southern Ocean38 (blue) and opal flux from the Atlantic sector of the Southern Ocean10 (dashed, green). g Global stack of atmospheric CO2 reconstructions8 (black). Shaded purple areas indicate Heinrich Stadial 1 (H1), the Bølling-Allerød /Antarctic Cold Reversal (BA/ACR), and the Younger Dryas (YD).

Low atmospheric δ13C during H1 has been interpreted as a direct consequence of upwelling (and outgassing) of deep, old water masses with low δ13C and high pCO2 in the Southern Ocean29. The correlation of atmospheric δ13C (ref. 29) with our benthic δ13C tightly connects AAIW/SAMW δ13C with the outgassing of these deep low δ13C water masses (Fig. 2a). The fact that the amplitude of our benthic δ13C at 838 m water depth is much larger (2–4 times) than the changes observed in the atmosphere confirms that the low benthic δ13C is sourced from the deep ocean, and not from the surface ocean as an indirect consequence of outgassing in the Southern Ocean30.

Multiple lines of evidence support our notion that the low deglacial benthic δ13C values at AAIW/SAMW depths reflect the entrainment of “old”, high pCO2/ nutrient-enriched water masses into AAIW/SAMW as has been speculated before6,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Benthic δ13C are inversely correlated to Ba/Ca (this study; nutrient proxy) and Rhenium (Re) excess concentrations21 (proxy for oxygenation) from the same site (see Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary Fig. 1). Further support for our interpretation stems from radiocarbon activities (Δ14C) of benthic foraminifera off the coast of Southern Chile at AAIW/SAMW depths (cores SO161-SL122; GeoB 7162)22,24 (Fig. 1a, b). Values deviate from the atmospheric Δ14C record during the deglaciation, and within AAIW/SAMW depths even reaching an extreme low value of ~ −200‰ during H1 (GeoB 7162), marking the presence of “old” water masses22,24. In contrast, core sites in the same ocean area but located outside and deeper than modern AAIW/SAMW are within Pacific Deep Water (PDW)20. These sites do not show deglacial benthic δ13C decreases and even point to increases which is in line with a better ventilation of aged glacial PDW20,24.

Our smoothed \(\overline{{{\rm{SS}}}}\) record shows considerable increases from ~14.25 μm to ~16.25 μm during H1 and high values of ~16 μm during YD, suggesting the intensification of AAIW/SAMW-related bottom currents at the intermediate depth core location (Fig. 2d). Such strengthening of AAIW/SAMW circulation together with low oxygen concentrations21 (high Re) and low benthic δ13C water (this study; Fig. 2a) is best explained by the entrainment of “old” upwelled Southern Ocean waters into AAIW/SAMW (see also Supplementary Fig. 1). Without this assumption, a stronger circulation would likely lead to increased oxygenation21, which contradicts the Re excess data.

The postulated acceleration of AAIW/SAMW current speeds is sustained by a model simulation for H1, showing an increased AAIW flow (and an atmospheric CO2 increase) in response to strengthened and poleward-displaced, Southern Hemisphere westerly winds (SWW)31. However, this simulation and a related simulation of atmospheric and oceanic δ13C did not reproduce our observed negative δ13C anomalies at AAIW/SAMW depths, but rather in the upper ocean layer30,31. Hence, we tested our observed AAIW/SAMW δ13C anomaly by running a Danish Center for Earth System Science (DCESS) model simulation forced with increased high-latitude ocean (i.e., Southern Ocean) vertical exchange for the H1 and YD periods (see Methods; Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary Fig. 2, 3). The results of the simulation for 800 m water depth qualitatively reproduces our observed negative δ13C anomalies in the South Pacific AAIW/SAMW, supporting the direct imprint of upwelled old (low δ13C) water masses in the Southern Ocean at AAIW/SAMW depths at Site 1233 (Fig. 3b). In addition, the results of this simulation for atmospheric pCO2 and δ13C show considerable agreement in timing and amplitude to the observed pCO2 and δ13C changes across H1 and YD (Fig. 3a, c).

a Atmospheric observed δ13C (dashed, black) in comparison to simulated outcome (black). b Simulated ocean δ13C at 800 m depth for low-mid latitudes (0–52°, red) and high latitudes (52–70°, blue). c Observed atmospheric pCO2 (dashed, black) in comparison to simulated outcome (black). For emphasis on the perturbations across the deglaciation, results presented in (a,b) have been detrended.

Strengthened AAIW/SAMW circulation and low benthic δ13C between H1 and YD appear quasi-synchronous with the low δ13C of subsurface-dwelling N. dutertrei (habitat depth of ~100 water depth32) and increased surface pCO2 based on boron isotopes from planktic foraminifera at eastern equatorial Pacific upwelling Site 1238 (ref. 6). This is accompanied by high opal accumulation rates at nearby Site V19-30 (ref. 33) (Fig. 2a–d). The synchroneity of events, provides support for the deglacial fueling of this region by increased flow of high pCO2 / nutrient-enriched AAIW/SAMW6. Indeed, AAIW/SAMW is in modern times a major southern source for the Pacific Equatorial Undercurrent and is estimated to account for 6–21% of its total transport5,34. A significant amount of anthropogenic CO2 along with nutrients are transported by AAIW/SAMW (including the same density layer we track at Site 1233) into the Equatorial Undercurrent through diapycnal mixing and finally to the surface by upwelling4,5,35. Additionally, direct upwelling of large amounts of AAIW/SAMW in the eastern equatorial Pacific was suggested from modern surface Δ14 C data at the Peruvian upwelling and the Costa Rica Dome36. Hence, it is plausible that principally during H1 and YD the increased AAIW/SAMW circulation which carried old and high pCO2 waters would have promoted the enhanced CO2 outgassing seen at eastern equatorial upwelling Site 12386 through one or both of these pathways (Fig. 2a, c, d). Also, other biochemical processes might have played a role for the increased outgassing during the deglacial. For instance, local mesopelagic nutrient recycling, a recently proposed major source for productivity in low latitudes lead to respiration of organic matter and therefore CO2 outgassing37. Yet it is difficult to quantify this process for the deglaciation, however, we suspect an increase as is simulated for future global warming with rising SST37. Deglacial outgassing in the eastern equatorial Pacific upwelling would have been complementary to vast CO2 outgassing in the Southern Ocean associated with global atmospheric CO2 increases during H1 and YD8,10 (Fig. 2g).

The low deglacial N. dutertrei δ13C at ODP Site 1238 (ref. 6) could have been caused by surface exchange with the atmosphere30. However, the close correspondence between high opal accumulation rates and increased CO2 outgassing at the surface, indicates that the N. dutertrei δ13C is associated with upwelling of high pCO2/ nutrient- rich waters6. Changes in the intensity of upwelling that could have impacted the above-described changes could be ruled out at ODP Site 1238 (ref. 6).

The paleocurrent speed proxy (\(\bar{{\mbox{SS}}}\)) record broadly matches the radiocarbon age difference record between planktic and benthic foraminifera from deeper adjacent core MD07-3088 (ref. 24; Fig. 1a, b; 2d, e; 1536 m water depth), a record that reflects water mass stratification changes (small 14C difference = more vertical mixing). The deglacial acceleration of the AAIW/SAMW between H1 and YD is accompanied by an intensification of vertical mixing, and hence a decrease in stratification at core location MD07-3088 (ref. 24). Apparently, both processes were responding to the intensifying upwelling and mixing of deep-water masses in the Southern Ocean10,38 (Fig. 2d–f), forced by increased and southward displaced SWW10,31.

At the same time there is evidence of reduced intermediate water mass stratification at sites along the Peruvian and Galapagos continental margins inferred from benthic δ13C and δ18O records between 400 and 1000 m water depths12. It was speculated that AAIW/SAMW warming might have reduced the vertical temperature gradients in the Eastern Pacific, leading to reduced water mass stratification in the eastern equatorial Pacific upwelling region12.

Our AAIW/SAMW temperature reconstructions at Site 1233 do not show a warming and instead imply rather cool temperatures during H1 and YD. Furthermore, a cooling of ~2 °C is observed at the end of the Bølling-Allerød (BA; ~14.5–12.8 ka BP) which is known in the Southern Hemisphere as the Antarctic Cold Reversal (ACR) (Fig. 4c). Hence, the increased AAIW/SAMW current speeds during the deglaciation most likely led to an increased contribution of AAIW/SAMW at these intermediate levels northward to the Equatorial Undercurrent and thereby might explain weak intermediate water stratification in the regions cited above.

a Benthic δ18O from Site 1233 (green, crosses), alkenone-derived sea surface temperatures (SST) from Site 1233 (ref. 46; age model updated according to our current age model; blue), and a stacked Antarctic δ18O record consisting of five (WAIS Divide, EDML, EDC, Dome Fuji, Talor Dome) Antarctic ice cores47 (yellow). b Reconstructed SWW changes in latitude (black) and strength (gray)48 and Sortable silt mean grain size variations \((\overline{{{\rm{SS}}}})\) (paleocurrent proxy) from Site 1233 (red, thick line is a 3% weighted smooth made with Kaleidagraph 5.0. c Benthic TMg/Ca from Site 1233 (black, dots) and error band in gray. d δ18OIVC-seawater reconstructions from Site 1233 (dashed blue, triangles) and error band in blue. e Alkenone-derived SST from GC- 528 (ref. 49; red) and benthic-planktic 14C age difference from MD07-3088 (ref. 24; blue). Error bands are based on the propagated errors given in the method section. Shaded purple areas indicate Heinrich Stadial 1 (H1), the Bølling-Allerød /Antarctic Cold Reversal (BA/ACR), and the Younger Dryas (YD).

Our reported changes in proxy records across the last deglaciation could be influenced by vertical changes in the depth of AAIW/SAMW39. For instance, a simulated global glacial shallowing of AAIW40 could move Site 1233 out of the modern core of AAIW/SAMW and under increasing influence of lower Pacific Deep Water (PDW) (Fig. 1b). Our benthic δ13C and salinity reconstructions, however, in combination with existing proxy records for oxygenation from Site 1233 and from sites 1235 and 1234 from the upper and lower limit of modern AAIW/SAMW21 (Fig. 1a, b) demonstrate that such shifts did not affect Site 1233 and that the changes we observe are instead principally related to changes in the properties and flow speed of AAIW/SAMW itself (see Supplementary Discussion).

South Pacific AAIW/SAMW influence up to Baja California

The close correspondence between our AAIW/SAMW current speed reconstructions and benthic δ13C with negative benthic Δ14C excursions at core location MC19-GC31-PC08 off Baja California at 705 m water depth also sheds light on the ongoing controversy regarding the deglacial influence of AAIW there16,18,19,41,42,43,44 (Fig. 1; 2a, d). Originally, these negative Δ14C excursions between H1 and YD were interpreted as the effect of the inflow of “old” Southern Ocean sourced water masses transported via AAIW to this site16,18,19. This was contrasted by the view that regional hydrothermal vents might have caused the extreme low Δ14C off Baja California43. A more widespread benthic Δ14C study in the eastern equatorial upwelling region, although lending support for AAIW as a source for moderate low Δ14C there, rather favoured North Pacific intermediate waters as a source for low Δ14C near Baja California, refuting the influence of regional hydrothermal vents44.

The synchronization in time of our Site 1233 data with near Baja California benthic Δ14C data clearly supports the original interpretation16,18,19. We provide evidence that the increased northward flow of “old” (low δ13C) AAIW/SAMW water masses between H1 and YD could have impacted Baja California causing negative Δ14C excursions there16,18 (Fig. 2a, d). Support comes from neodymium isotope studies from the last deglacial from the same Baja California site (fish teeth) and the modern (water samples) from a wider area in the North Pacific42,45. The deglacial study off Baja California clearly shows a Southern Ocean source during intervals of low Δ14C excursions42. Additionally, the modern-day North Pacific study suggests that AAIW even has a strong impact on North Pacific intermediate waters45.

SWW as the main driver for AAIW/SAMW changes

Our benthic δ18O record from Site 1233 largely parallels alkenone-derived SSTs from the same site46 (age model updated according to our current age model; see Methods) and an Antarctic stacked δ18O record consisting of five Antarctic ice core cores that reflects changes in surface air temperatures47 (Fig. 4a). During H1 SST warming (~18–16 ka BP), there is a dramatic benthic δ18O decline of ~1.5‰, followed by a plateau of values around 3.5‰ from the end of H1 across BA/ACR and then a decrease again of ~1‰ during the YD warming (Fig. 4a). These similarities between our benthic δ18O record and alkenone-derived SST46 point to nearly synchronous deglacial changes at intermediate and in the surface waters.

The warming periods during H1 and the YD observed in alkenone-derived SST were interpreted as a combination of southward shifts of the SWW and Antarctic temperature increases, that directly affected atmospheric CO2 increases through upwelling and outgassing in the Southern Ocean46. The BA/ACR, however, known as a cooling period in the Southern Hemisphere was described as a warm SST plateau, which did not suggest a rebound of the SWW back to the north46 (Fig. 4a).

A recent combined model-data study based on available planktic foraminiferal δ18O records from the Southern Ocean support these deglacial changes in SWW, showing a ~5° poleward shift and ~25% strengthened SWW circulation48 (Fig. 4b). As stronger and more southward SWW most likely intensified AAIW formation31, it makes sense, that the deglacial AAIW/SAMW current speed increases at Site 1233 (\(\overline{{{\rm{SS}}}}\)) are in broad agreement with these poleward-displaced and strengthened SWW (Fig. 4a, b).

However, the comparison of our benthic Mg/Ca-derived temperatures (TMg/Ca) with alkenone-derived sea surface temperatures (SST) from the same site46 shows an opposite development during H1 and at the end of the BA/ACR (Fig. 4a, c). During H1 (~18 and 16 ka BP), when alkenone-derived SST46 increased most by ~4 °C, benthic TMg/Ca stay relatively cold, and at the end of the BA/ACR when benthic TMg/Ca show a decrease of ~2 °C (Fig. 4a, c), alkenone derived SST reached a warm plateau ~13 °C (ref. 46; Fig. 4a, c).

This lack of deglacial warming of our benthic TMg/Ca creates an apparent mismatch with our decreasing benthic δ18O values (Fig. 4a, c). However, the benthic δ18O record does not exclusively reflect AAIW/SAMW temperatures, but instead depends on global ice volume, sea water temperature, and salinity. Our benthic δ18OIVC-seawater record, corrected for these changes in global ice volume and temperature (see Methods) points to a lowering during H1, and at the end of BA/ACR with a total amplitude of ~1.3‰ (freshening), synchronous with relatively cold or cooling of benthic TMg/Ca, at times when the SWWs increased and shifted poleward48 (Fig. 4b–d).

Hence, we argue that the freshening with relatively cold AAIW/SAMW temperatures during H1 and at the end of BA/ACR at Site 1233 were mainly driven by these changes in SWW through affecting the source region of AAIW/SAMW. This interpretation is supported by an alkenone-derived SST record from core GC-528 located in the Drake Passage49 that shows deglacial cooling during the southward shift and strengthening of SWWs48 that broadly resembles our cold AAIW/SAMW temperatures during H1 and at the end of BA/ACR. (Fig. 4b, c, e).

Core GC- 528 is reasonably representative for the source region of AAIW/SAMW bathing Site 1233 between ~50–60°S, just as modern AAIW formed at Drake Passage-like latitudes contributes to Atlantic Ocean AAIW and Southeast Pacific AAIW/SAMW that flows northward along the coast of Chile25,50.

The tight interconnection between both ocean regions at different depth levels becomes especially evident by the comparison of our δ18OIVC-seawater values with GC-528 alkenone-derived SST49 (Fig. 4d, e). Warm (cold) periods at GC- 528 (ref. 49) coincide with more saline (fresher) AAIW/SAMW conditions at Site 1233 with notable AAIW/SAMW freshening at the end of BA/ACR.

Previously, it was argued that the deglacial poleward movement of SWW redirected the cold AAIW from the Pacific into the Atlantic, that might explain SST cooling at GC-528 (ref. 49). However, this would not explain synchronous cool AAIW/SAMW during H1 and cooling during the end of BA/ACR at Site 1233 (Fig. 4c, e).

Alternatively, we suggest that strengthening and poleward migration of the SWW enhanced upwelling of cold, deep-water masses and mixing between the polar and the subantarctic fronts nearby GC-528 that caused sea surface cooling in the AAIW/SAMW formation area, consequently affecting AAIW/SAMW temperatures at Site 1233. This cooling effect through upwelling/mixing is evidenced by the synchronous correlation between vertical mixing at MD07-3088 (ref. 24) and alkenone-derived SST at GC-528 (ref. 49) (Fig. 4e). Warm glacial alkenone-derived SST occurred when water masses were stratified, and SST dropped when the stratification decreased during the deglaciation. A general surface cooling effect from the Southern Hemisphere during the final BA/ACR, cannot be ruled out for having indirectly amplified AAIW/SAMW cooling at Site 1233, but seems rather unlikely, as the BA/ACR was not characterized as a surface cooling period at this Site46. The high SST during the glacial at GC-528 (ref. 49) could have been amplified by regional meltwater stratification that might explain higher amplitudes there in comparison to Site 1233 AAIW/SAMW temperatures (Fig. 4c, e).

The freshening of AAIW/SAMW during H1 and at the end of BA/ACR at Site 1233 is best explained by increased freshwater input into the AAIW/SAMW formation area, most likely caused by increased precipitation rates due to the southward shift of the SWWs12,51. In particular, during H1, this freshening was likely amplified by melting of sea ice or icebergs through vast Antarctic warming12,51. During this time, increased sea-ice transport from strengthened SWWs likely intensified AAIW/SAMW formation rates52. The formation of relatively fresh AAIW/SAMW during H1 and at the end of BA together with deep upwelling is not unlike the situation in the modern ocean, whereby upwelled relatively salty, Circumpolar Deep Water is transformed in part into relatively fresh AAIW/SAMW52.

We reconstructed Southeast Pacific AAIW/SAMW properties close to its formation area at ODP Site 1233. Our benthic foraminiferal δ13C and sortable silt mean grain sizes (\(\overline{{{\rm{SS}}}}\)) showed prominent δ13C decreases and a strengthened northward AAIW/SAMW circulation between H1 and YD. These changes in combination with other proxy records from the same site suggested a strong northward flow of high pCO2 and nutrient-enriched AAIW/SAMW during H1 and YD, synchronous with the changes in the proxy records from the eastern Pacific equatorial upwelling region and even off Baja California. Our proxy evidence supports earlier assumptions about the far-reaching effects of AAIW/SAMW, which most likely increased outgassing of oceanic CO2 in the eastern equatorial Pacific upwelling region6. Deglacial changes in our AAIW/SAMW temperature, salinity and current speed reconstructions were related to poleward shifted and strengthened SWW, which shaped the evolution and hence the properties of Southeast Pacific AAIW/SAMW.

Methods

Analysis of benthic foraminiferal stable isotopes (δ18O and δ13C), Mg/Ca, and Ba/Ca

For Mg/Ca and stable isotope analysis on benthic foraminifer Uvigerina peregrina we mostly used 20 cm3 of bulk sediment which was increased to 100 cm3 in several cases during the last 20 kyrs because of lack of enough specimens. Bulk samples from Site 1233 were freeze-dried, wet sieved over a 63 μm sieve and dried in an oven at 40 °C. We then carefully selected benthic foraminifers from the >250 μm fraction size using a stereo microscope. For Elemental analysis (Mg/Ca, Ba/Ca) ∼7–20 specimens were selected and gently crushed between glass plates. If the sample material was ∼ >15 specimens, the crushed sample was separated into 2/3 used for Elemental analysis and into 1/3 which was used for stable isotope measurements. In cases when the sample material was smaller, 2-3 specimens were separated from the sample and used for stable isotope analysis. Stable isotope analyses were performed at GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel on a Thermo Scientific MAT 253 with a Kiel IV Carbonate device. Standard Deviations (Analytical Precision 1σ) of Bremen standards measured during the sessions (n = 73) was ∼0.04 ‰ for δ13C and ∼0.09‰ for δ18O. Crushed samples for elemental analysis were cleaned according to standard cleaning procedure53 (including reductive step with hydrazine) before analysis on a VARIAN 720–ES Axial ICP-OES at GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel. Spectral lines for Mg/Ca ratios were 279 nm and 370 nm, and for Ba 455 nm. To monitor any remaining contamination source for the Mg/Ca (Ba/Ca) ratios through the presence of silicates and/or Mn-Fe oxyhydroxide coatings, Al (167 nm), Fe (238 nm), and Mn (257 nm) were measured. Al/Ca and Mn/Ca ratios were on average low and near detection limits and Fe/Ca ratios showed a median value of 0.1 mmol/mol indicating effective cleaning. However, when Al/Ca ratios were greater than >0.1 mmol/mol and were accompanied by relatively high Mg/Ca ratios we discarded these samples (including Ba/Ca values) as this might be an indication of contamination with terrigenous material53. Mostly, these samples also showed higher Fe/Ca ratios (>0.1 mmol/mol). In one case, we decided to discard a sample based on high Fe/Ca. To correct a drift during the measurement sessions, the ECRM 752-1 standard was measured repeatedly. Blanks were inserted every 15th sample to monitor any external contamination. On average, analytical precision (1σ) for Mg/Ca ratios was ~0.04 mmol/mol.

Calculation of Benthic temperatures, δ18Oseawater and ice volume corrected seawater values (δ18OIVC-seawater)

Bottom water temperatures were reconstructed using the core top based equation54: Mg/Ca= 0.074 (±0.004) x T + 0.81 (±0.05) which translates into a temperature error of ~ ±0.9 °C when applying our analytical precision of Mg/Ca analyses. We chose this equation as it provides the best fit of our core top benthic Mg/Ca-derived temperatures of on average 3.8 °C (7 data points within the last 5.3 kyrs) with modern observed temperatures of 4.5 °C at 830 m water depth near Site 1233 (ref. 55). It is known that the carbonate ion saturation of sea waters changed during the last deglaciation and is different between water masses and that this can affect benthic foraminiferal Mg/Ca ratios either during the precipitation process or post-depositional through calcite dissolution54,56. However, as has been shown, Mg/Ca ratios of Uvigerina peregrina are practically unaltered by these changes54,56 supporting the robustness of our benthic Mg/Ca-derived temperatures.

Before calculating δ18Oseawater and ice volume corrected seawater values (δ18OIVC-seawater) which serve as an approximation for past changes in salinities, the benthic δ18O record was interpolated because unfortunately, not all our Mg/Ca data were covered by δ18O data points due to lack of sample material. Interpolation between measured δ18O values were in the range of a few hundred years, and only once during the Holocene reach about 1 kyr. Due to interpolation between such short time intervals, we assume that the values are robust. δ18Oseawater values were then calculated using an established equation57: T = 16.9 − 4.38 \(\cdot\) (δ18Oforam- δ18Oseawater) + 0.1 \(\cdot\) (δ18Oforam - δ18Oseawater)2 after adding 0.27 ‰ for adjusting to the SMOW scale58. Finally, values were corrected for changes in global ice volume to calculate δ18OIVC-seawater values. Here a high-resolution estimation of global ice volume change was used which is based on multiple observations of sea level changes over the last 35 kyrs59. On average, the propagated error for our δ18Oseawater values is ~ ± 0.26‰ and we estimate a similar error for our δ18OIVC-seawater values as we used the high-resolution and accurate ice volume estimation59.

Grain size analyses and sortable silt mean grain size (\(\bar{{\mbox{SS}}}\)) as paleocurrent proxy

For grain size analyses we used approx. 700–750 mg from the freeze-dried bulk sediment (20 cm3), and then chemical removal steps of organic material and calcium carbonate followed60,61. To minimize any possible contamination with dust particles during removal steps, we decided to work under a laminar flow cabinet. Biogenic silica was not removed as opal concentrations were on average 3.7% (max. value of 5.2%) within the studied time interval21,62 and therefore estimated as negligible60. Organic material was removed by adding 20 mL H2O2 (35%) at about 70 °C for 6 h or until no further reaction took place. CaCO3 was removed by adding 10 ml HCl (10%) to 100 ml MilliQ water at about 90 °C for a few minutes. Subsequently, the acid sample solution was removed by repeated dilution with MilliQ water and decantation. Visual inspection of some samples after the removal steps with a microscope could not reveal any biogenic material. Finally, sample material was ultrasonicated and stored in a 0.02 M Polyphosphate solution. Before analysis, samples were again shortly ultrasonicated, filtered over a 100 μm membrane and analyzed on a Beckman Coulter Counter Multisizer 4e with an aperture tube of 100 μm at Pontifical Catholic University of Chile.

\(\overline{{{\rm{SS}}}}\) was then calculated according to the equation63,64: \(\bar{{\mbox{SS}}}\) = \(\frac{1}{V}{\sum }_{i=190}^{400}\left({V}_{i}\cdot {{d}}_{i}\right)\) Where i is the size bin reaching from 190 = 10.02 μm to 400 = 59.75 μm. (The used grain size scale is justified as no grains were detected within 59.75 μm and 63 μm. Vi is the differential volume at the ith size bin, and di is mid-size of the ith size bin, and V is the total volume between i = 190 and i = 400. Because it has been shown that only a few data counts of the coarse end of the Sortable Silt scale can alter the \(\overline{{{\rm{SS}}}}\) result through their disproportional high weights compared to the small grain numbers64, every sample was measured 2–6 times and an average value was calculated showing a standard deviation (1σ) of on average ~0.5 μm (150 samples). Additionally, all raw values of repeated analyses of the same samples were monitored to check consistency between single measurements. In 20 samples, we discarded single grain counts (1–4) in the coarse fraction (~30–60 μm) as they were not represented in the repeated analyses. Before rejecting these single grain counts, these samples usually showed an anomalous high standard deviation between 1.2 μm and 2.5 μm. Mismatches between repeated analyses of the same samples might have been caused by different errors. One might be the possibility that air bubbles were occasionally trapped within the system during measuring and were erroneously counted as grains. The other is the described phenomena of coincidence correction of measuring single grains, which can lead to artificial counts of grains caused by the software64.

Age model

For an initial age control of Site 1233 we used published age control tie points during the Holocene based on tuning high-resolution Ca and magnetic susceptibility records to nearby 14C dated core GeoB3313-3 (Supplementary Fig. 4; ref. 65). For the period 8.7–32.8 ka BP we used 21 existing mixed planktic foraminiferal 14C AMS age control points46,65,66,67. These 14C AMS age datums were originally calibrated based on different curves e.g., CALPAL 2004 January calibration curve (www.calpal.de), INTCAL04 (ref. 68), and Fairbanks0107 (ref. 69). As all these calibration curves are now outdated, we updated the original 14C AMS age datums with Calib 8.20 software70 using the current calibration curve for the Southern Hemisphere71 (SHCal20; see Supplementary Table 1). Evidence from detailed tephrostratigraphy from southward located MD07-3088 indicates that reservoir ages most likely have considerably changed during the studied time-period24,72. As a detailed tephrostratigraphic study does not exist from Site 1233, we applied variable reservoir ages for the surface ocean using a model simulation73 and subtracted these from the initial datums before calibration (see Supplementary Table 1). Simulated average reservoir ages close by Site 1233 (41°S; 75°W) with a temporal resolution of 1 kyr were used for the critical time between 11 and 25 ka BP, and this resolution was lowered to 5 kyr for the Holocene and the remaining glacial period73. Subsequently, a 3-point moving average smooth was calculated. Then, uncalibrated atmospheric 14C ages were determined for these simulated sea surface reservoir ages and applied to uncalibrated 14C age datums from Site 1233. The obtained results were compared with the sea surface reservoir age from an identified tephra layer (Lepué Tephra) at Site 1233 with a basal depth of 14.80 mcd, which eruption could be dated using land deposits indicating a 14C age (BP) of ~9588 years74. Interpolation between planktic foraminiferal radiocarbon 14C ages (BP) at Site 1233 gives a marine age of ~10.07 ka BP for this tephra layer, resulting in a difference of 481 years compared with the land deposits, which is in accordance with the used simulated sea surface reservoir age of 554 years for this time (see Supplementary Table 1). The maximum difference between our used model-based surface reservoir age estimations73 and these proposed for site MD07-3088 (ref. 24) is ~400 years. Compared to previous reported age models from the same Site46,65,66,67 our revised age model has a maximum difference of ~1000 years during the deglaciation (Supplementary Fig. 4). As during the critical time period between 8 and 30 ka BP, there is every 1.1 kyrs a 14C AMS tie point, and the simulated surface reservoir ages were confirmed by one tephra layer, we assess the age model as robust. Indirect support for the updated age control comes from the timely match of our benthic δ18O and an Antarctic δ18O ice core stack47 (Fig. 4a).

DCESS model simulation

The DCESS Earth system model75 features modules for the atmosphere, ocean, ocean sediment, land biosphere and lithosphere, calibrated and tested against Earth system data and against output from more complex models. The model consists of one hemisphere, divided by 52° latitude into a low-mid latitude and a high latitude zone. The atmosphere module considers radiation balance, meridional transport of heat and water vapor between low-mid latitude and high latitude zones, and heat and gas exchange with the ice-free part of the ocean. Gases considered are carbon dioxide and methane for all three carbon isotopes, nitrous oxide and oxygen.

The model ocean is 270° wide, extends from the equator to 70° latitude and covers 70.5% of the Earth surface. Each ocean sector has 55 vertical layers with 100 m resolution. An ocean sediment sector is assigned to each ocean layer with widths taken from observed depth distributions. The ocean module has prescribed circulation and mixing. Model ocean tracers are temperature, salinity, oxygen isotope in water, phosphate, dissolved inorganic carbon for all three carbon isotopes, and alkalinity. Biogenic production of particulate organic matter depends on surface layer phosphate availability but with lower efficiency in the high latitude zone, due for example to iron limitation. The calcite to organic carbon rain ratio depends on surface layer temperature and carbonate ion concentration76.

The semi-analytical, ocean sediment module considers calcium carbonate dissolution and oxic and anoxic organic matter remineralization. The sediment is composed of calcite, non-calcite mineral and reactive organic matter. The land biosphere module considers leaves, wood, litter and soil. Net primary production depends on atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration and remineralization rates in the litter and soil depend on mean atmospheric temperatures. Methane production is a small fraction of the soil remineralization. This module has been extended to include three dynamically varying vegetation zones and a permafrost component77. The lithosphere module considers outgassing, weathering of carbonate and silicate rocks and weathering of rocks with old organic carbon and phosphorus.

For the simulation presented here we applied a approach77 for the last glacial termination that was updated to better represent dust-climate feedbacks78. For the period 25 ka BP to the present, we prescribed albedo forcing from changing ice sheet size as well as dust radiative forcing and iron fertilization of high latitude ocean biota as described in the above references.

We found agreement with observed low last glacial atmospheric pCO2 for the prescribed 25 ka BP forcing and with vertical exchange coefficient in the high latitude ocean (kvHL) above 1000 m reduced by 30% relative to pre-industrial levels (as calibrated before75) and kvHL below 1000-2000 m set to low values of the low-mid latitude ocean. Depth-dependent kvHL in the model last glacial generates a model analogy to isolated deep water in the Southern Ocean at that time. This is meant to emulate the effects of some combination of weakened or equatorward-shifted SWW and increased stratification through brine-induced effects as have been suggested in various studies31,48,79,80. This led to significantly increased deep ocean storage of 13C-depleted, dissolved inorganic carbon from remineralization of organic matter raining down from the ocean surface layer. In addition to the above mentioned forcing we also varied over time the size and distribution of kvHL to simulate storage/release of deep ocean carbon from/to the upper ocean and atmosphere (Supplementary Fig. 2). For the H1 and YD periods, we increased kvHL over all or most high latitude ocean depths to at or near preindustrial levels to emulate increased Southern Ocean upwelling drawn from greater depths as well as increased vertical exchange as would result from stronger SWW during these periods.

Data availability

The proxy data generated in this study have been deposited in the World Data Center for Paleoclimatology (WDC Paleo) under accession code: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/paleo-search/study/40139.

Code availability

Results from the model simulation is available at www.dcess.dk.

References

Sabine, C. L. et al. The oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2. Science 305, 367–CO371 (2004).

McCartney, M. S. Subantarctic Mode Water. In: Angel, M. (Ed.), A Voyage of Discovery. Pergamon, Oxford, pp. 103–119 (1977).

Sarmiento, J., Gruber, N., Brzezinski, M. A. & Dunne, J. P. High-latitude controls of thermocline nutrients and low latitude biological productivity. Nature 427, 56–60 (2004).

Resplandy, L., Bopp, L., Orr, J. C. & Dunne, J. P. Role of mode and intermediate waters in future ocean acidification: analysis of CMIP5 models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 3091–3095 (2013).

Ishii, M. et al. Ocean acidification from below in the tropical pacific. Glob. Biogeochemical Cycles 34, e2019GB006368 (2020).

Martínez-Botí, M. A. et al. Boron isotope evidence for oceanic carbon dioxide leakage during the last deglaciation. Nature 518, 219–222 (2015).

Takahashi, T. et al. Climatological mean and decadal change in surface ocean pCO2, and net sea-air CO2 flux over the global oceans. Deep-Sea Res. I 56, 2075–2076 (2009).

Köhler, P. et al. A 156 kyr smoothed history of the atmospheric greenhouse gases CO2, CH4, and N2O and their radiative forcing. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 9, 363–387 (2017).

Clark, P. U. et al. Global climate evolution during the last deglaciation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 1134–1142 (2012).

Anderson, R. F. et al. Wind-driven upwelling in the Southern ocean and the deglacial rise in atmospheric CO2. Science 13, 1443–1448 (2009).

Skinner, L. C. et al. Ventilation of the Deep Southern Ocean and Deglacial CO2 Rise. Science 328, 1147–1151 (2010).

Bova, S. C. et al. Links between eastern equatorial Pacific stratification and atmospheric CO2 rise during the last deglaciation. Paleoceanography 30, 1407–1424 (2015).

Oppo, D. W. & Fairbanks, R. G. Carbon isotope composition of tropical surface water during the past 22,000 years. Paleoceanography 4, 333–351 (1989).

Ninnemann, U. S. & Charles, C. D. Regional differences in Quaternary subantarctic nutrient cycling: Link to intermediate and deep water ventilation. Paleoceanography 12, 560–567 (1997).

Spero, H. J. & Lea, D. W. The Cause of Carbon Isotope Minimum Events on Glacial Terminations. Science 296, 522–525 (2002).

Marchitto, T. M. et al. Marine Radiocarbon Evidence for the Mechanism of Deglacial Atmospheric CO2 Rise. Science 316, 1456–1459 (2007).

Calvo, E. et al. Eastern Equatorial Pacific productivity and related-CO2 changes since the last glacial period. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 5537–5541 (2011).

Lindsay, C. M. et al. The surface expression of radiocarbon anomalies near Baja California during deglaciation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 422, 67–74 (2015).

Lindsay, C. M. et al. New constraints on deglacial marine radiocarbon anomalies from a depth transect near Baja California. Paleoceanography 31, 1103–1116 (2016).

Haddam, N. A. et al. Ventilation and expansion of intermediate and deep waters in the Southeast Pacific during the last termination. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 35, e2019PA003743 (2020).

Muratli, J. et al. Increased glacial-age ventilation of the Chilean margin by Antarctic Intermediate Water. Nat. Geosci. 3, 23–26 (2010).

Martínez Fontaine, C. et al. Ventilation of the Deep Ocean Carbon Reservoir During the Last Deglaciation: Results From the Southeast Pacific. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 34, 2080–2097 (2019).

De Pol-Holz, R. et al. No signature of abyssal carbon in intermediate waters off Chile during deglaciation. Nat. Geosci. 3, 192–195 (2010).

Siani, G. et al. Carbon isotope records reveal precise timing of enhanced Southern Ocean upwelling during the last deglaciation. Nat. Comm. 4, 2758 (2013).

Bostock, H. C. et al. Reviewing the circulation and mixing of Antarctic Intermediate Water in the South Pacific using evidence from geochemical tracers and Argo float trajectories. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. 73, 84–98 (2013).

Hanawa, K. & Talley, L. D. Mode Waters. Ocean Circulation and Climate, 373–386, Eds., Siedler, G. & Church, J., International Geophysics Series (Academic Press 2001).

Reyes-Macaya, D. et al. Isotopic characterization of water masses in the Southeast Pacific region: Paleoceanographic implications. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 127, e2021JC017525 (2022).

Sloyan, B. M. & Rintoul, S. R. Circulation, Renewal, and Modification of Antarctic Mode and Intermediate Water. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 31, 1005–1030 (2001).

Schmitt, J. et al. Carbon Isotope Constraints on the Deglacial CO2 Rise from Ice Cores. Science 336, 711–714 (2012).

Shao, J. et al. The atmospheric bridge communicated the δ13C decline during the last deglaciation to the global upper ocean. Clim 17, 1507–1521 (2021).

Menviel, L. et al. Southern Hemisphere westerlies as a driver of the early deglacial atmospheric CO2 rise. Nat. Comm. 9, 2503 (2018).

Farmer, E. C. et al. Corroborating ecological depth preferences of planktonic foraminifera in the tropical Atlantic with the stable oxygen isotope ratios of core top specimens. Paleoceanography 22, PA3205 (2007).

Bradtmiller, L. I., Anderson, R. F., Fleisher, M. Q. & Burckle, L. H. Diatom productivity in the equatorial Pacific Ocean from the last glacial period to the present: a test of the silicic acid leakage hypothesis. Paleoceanography 21, PA4201 (2006).

Nie, X., Gao, S., Wang, F., Chi, J. & Qu, T. Origins and pathways of the Pacific Equatorial Undercurrent identified by a simulated adjoint tracer. J. Geophys. Res.: Oceans 124, 2331–2347 (2019).

Rafter, P. A. & Sigman, D. M. Spatial distribution and temporal variation of nitrate nitrogen and oxygen isotopes in the upper equatorial Pacific Ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 61, 14–31 (2016).

Toggweiler, J. R., Druffel, E. R. M., Key, R. M. & Galbraith, E. D. Upwelling in the ocean basins north of the ACC: 1. On the upwelling exposed by the surface distribution of Δ14 C. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 124, 2591–2608 (2019).

Rodgers, K. B. et al. Low-latitude mesopelagic nutrient recycling controls productivity and export. Nature 632, 802–807 (2024).

Chase, Z., Anderson, R. F., Fleisher, M. Q. & Kubik, P. W. Accumulation of biogenic and lithogenic material in the Pacific sector of the Southern Ocean during the past 40,000 years. Deep-Sea Res., Part 2, Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 50, 799–832 (2003).

Pahnke, K. & Zahn, R. Southern Hemisphere Water Mass Conversion Linked with North Atlantic Climate Variability. Science 307, 1741–1746 (2005).

Li, L., Liu, Z., Zhu, C., He, C. & Otto-Bliesner, B. Shallowing glacial Antarctic Intermediate Water by changes in sea ice and hydrological cycle. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL094317 (2021).

Hain, M. P., Sigman, D. M. & Haug, G. H. Shortcomings of the isolated abyssal reservoir model for deglacial radiocarbon changes in the mid-depth Indo-Pacific Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L04604 (2011).

Basak, C., Martin, E. E., Horikawa, K. & Marchitto, T. M. Southern Ocean source of 14C-depleted carbon in the North Pacific Ocean during the last deglaciation. Nat. Geosci. 3, 770–773 (2010).

Zhao, N. & Keigwin, L. D. An atmospheric chronology for the glacial-deglacial eastern equatorial Pacific. Nat. Commun. 9, 3077 (2018).

Bova, S. C., Herbert, T. D. & Altabet, M. A. Ventilation of northern and southern sources of aged carbon in the eastern equatorial Pacific during the Younger Dryas rise in atmospheric CO2. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 33, 1151–1168 (2018).

Fuhr, M. et al. Tracing Water Mass Mixing From the Equatorial to the North Pacific Ocean With Dissolved Neodymium Isotopes and Concentrations. Front. Mar. Sci., 7 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.603761 (2020).

Lamy, F. et al. Modulation of the bipolar seesaw in the Southeast Pacific during Termination 1. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 259, 400e413 (2007).

Buizert, C. et al. Abrupt ice-age shifts in southern westerly winds and Antarctic climate forced from the north. Nature 563, 681–685 (2018).

Gray, W. R. et al. Poleward shift in the Southern Hemisphere westerly winds synchronous with the deglacial rise in CO2. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol 38, e2023PA004666 (2023).

Roberts, J. et al. Deglacial changes in flow and frontal structure through the Drake Passage. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 474, 397–408 (2017).

Sallée, J. et al. Southern Ocean Thermocline Ventilation. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 40, 509–529 (2010).

Keeling, R. F. & Stephens, B. B. Antarctic sea ice and the control of Pleistocene climate instability. Paleoceanography 16, 112–131 (2001).

Abernathey, R. et al. Water-mass transformation by sea ice in the upper branch of the Southern Ocean overturning. Nat. Geosci. 9, 596–601 (2016).

Barker, S., Greaves, M. & Elderfield, H. A study of cleaning procedures used for foraminiferal Mg/Ca paleothermometry. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 4, 8407 (2003).

Elderfield, H. et al. A record of bottom water temperature and seawater δ18O for the Southern Ocean over the past 440 kyr based on Mg/Ca of benthic foraminiferal Uvigerina spp. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 160–169 (2010).

Locarnini, R. A. et al. World Ocean Atlas 2013, Volume 1: Temperature. S. Levitus, Ed., A. Mishonov Technical Ed.; NOAA Atlas NESDIS 73, 40 pp (2013).

Elderfield, H. et al. Calibrations for benthic foraminiferal Mg/Ca paleothermometry and the carbonate ion hypothesis. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 250, 633–649 (2006).

Shackleton, N. J. Attainment of isotope equilibrium between ocean water and the benthonic foraminiferal genus Uvigerina. Isotopic changes in the ocean during the last glacial. Cent. Nat. Rech. Sci. Colloq. Int. 219, 203 (1974).

Hut, G. Consultants’ group meeting on stable isotope reference samples for geochemical and hydrological investigations. Int. Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna (1987).

Lambeck, K. et al. Sea level and global ice volumes from the Last Glacial Maximum to the Holocene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U. S. A 111, 15296–15303 (2014).

Mc Cave, I. et al. Sortable silt and fine sediment size/composition slicing: parameters for palaeocurrent speed and palaeoceanography. Paleoceanography 10, 593–610 (1995).

Mulitza, S. et al. Sahel megadroughts triggered by glacial slowdowns of Atlantic meridional overturning. Paleoceanography 23, PA4206 (2008).

Chase, Z., McManus, J., Mix, A. C. & Muratli, J. Southern-ocean and glaciogenic nutrients control diatom export production on the Chile margin. Quat. Sci. Rev. 99, 135–145 (2014).

Tegzes, A. D. et al. The role of the northward-directed (sub)surface limb of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation during the 8.2 ka event. Clim 10, 1887–1904 (2014).

Tegzes, A. D., Jansen, E. & Telford, R. J. Which is the better proxy for paleo-current strength: Sortable-silt mean size (ss) or sortable-silt mean grain diameter (dSS)? A case study from the Nordic Seas. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 16, 3456–3471 (2015).

Kaiser, J., Lamy, F. & Hebbeln, D. A 70-kyr sea surface temperature record off southern Chile (Ocean Drilling Program Site 1233). Paleoceanography 20, PA4009 (2005).

Lamy, F. et al. Antarctic timing of surface water changes off Chile and Patagonian Ice Sheet response. Science 304, 1959e1962 (2004).

Kaiser, J. et al. Links between Patagonian Ice Sheet fluctuations and Antarctic dust variability during the last glacial period (MIS 4-2). Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 1464–1471 (2010).

Reimer, P. J. et al. INTCAL04 terrestrial radiocarbon age calibration, 0-26 cal kyr BP. Radiocarbon 46, 1029–1058 (2004).

Fairbanks, R. G. Radiocarbon calibration curve spanning 0 to 50,000 years BP based on paired 230Th/234U/238U and 14C dates on pristine corals. Quat. Sci. Rev. 24, 1781–1796 (2005).

Stuiver, M. & Reimer, P. J. CALIB rev. 8. Radiocarbon 35, 215–230 (1993).

Hogg, A. G. et al. SHCal20 Southern Hemisphere Calibration, 0–55,000 Years cal BP. Radiocarbon 62, 759–778 (2020).

Carel, M., Siani, G. & Delpech, G. Tephrostratigraphy of a deep-sea sediment sequence off the south Chilean margin: New insight into the Hudson volcanic activity since the last glacial period. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 208, 99–111 (2011).

Butzin, M., Köhler, P. & Lohmann, G. Marine radiocarbon reservoir age simulations for the past 50,000 years. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 8473–8480 (2017).

Alloway, B. V. et al. Stratigraphy, age and correlation of Lepue Tephra: a widespread c. 11000 cal a BP marker horizon sourced from the Chaiten Sector of southern Chile. J. Quat. Sci. 32, 795–829 (2017).

Shaffer, G., Olsen, S. M. & Pedersen, J. O. P. Presentation, calibration and validation of the low-order, DCESS Earth System Model (Version 1). Geoscientific Model Dev. 1, 17–51 (2008).

Shaffer, G., Huber, M., Rondanelli, R. & Pepke Pedersen, J. O. Deep time evidence for climate sensitivity increase with warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 6538–6545 (2016).

Eichinger, R. et al. An improved land biosphere module for use in the DCESS Earth system model (version 1.1) with application to the last glacial termination. Geoscientific Model Dev. 10, 3481–3498 (2017).

Shaffer, G. & Lambert, F. In and out of glacial extremes by way of dust−climate feedbacks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. Usa. 115, 2026–2031 (2018).

Bouttes, N., D. Paillard, D. & Roche, D. M. Impact of brine-induced stratification on the glacial carbon cycle. Clim 6, 575–589 (2010).

Toggweiler, J. R., Russell, J. L. & Carson, S. R. Midlatitude westerlies, atmospheric CO2, and climate change during the ice ages. Paleoceanography 21, PA2005 (2006).

Schlitzer, R. Ocean Data View, http://odv.awi.de (2020).

Zweng, M. M. et al. World Ocean Atlas 2013, Volume 2: Salinity. Levitus, S. Ed., Mishonov, A. Technical Ed.; NOAA Atlas NESDIS 74, 39 (2013).

Garcia, H. E. et al. World Ocean Atlas 2013, Volume 3: Dissolved Oxygen, Apparent Oxygen Utilization, and Oxygen Saturation. Levitus, S. Ed., Mishonov, A. Technical Ed.; NOAA Atlas NESDIS 75, 27 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) for providing the sample material used in this study. C.K. thanks to Nadine Gehre, Paulina Guzmán, Laura Gana, and Francia Perez for technical support in the Lab. Financial support was provided by ANID Fondecyt Regular No. 1230534 (C.K.). Further support came from ANID-Fondecyt Regular No. 1231682 (F.L.). Additional funding was provided by DICYT-USACH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.K. conceptualized this study, led the writing of the manuscript, the analyzing and interpretation of the data. D.N., F.B., G.S., and F.L. were involved in the interpretation of the data and in writing. D.N. and F.B. contributed to the analysis of the data. G.S. provided the model simulation results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Masao Ishii, Juan Muglia and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Karas, C., Nürnberg, D., Lambert, F. et al. Enhanced deglacial carbon transport by Pacific southern-sourced intermediate and mode water. Nat Commun 16, 5245 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60551-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60551-5