Abstract

The idea of fractional derivatives has a long history that dates back centuries. Apart from their intriguing mathematical properties, fractional derivatives have been studied widely in physics, for example in quantum mechanics and generally in systems with nonlocal temporal or spatial interactions. However, systematic experiments have been rare because the physical implementation is challenging. Here we report the observation and full characterization of a family of temporal solitons that are governed by a fractional nonlinear wave equation. We demonstrate that these solitons have non-exponential tails, reflecting their nonlocal character, and have a very small time-bandwidth product.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Derivatives, as a fundamental concept of calculus for more than three centuries, are usually understood to be of integer order, however a more general class of fractional order derivatives can be defined1. The idea of a fractional derivative was raised as early as 1695 in a correspondence between Leibniz and de l’Hôpital2, with fractional calculus being derived multiple times in attempts to understand physical observations, from the early work of Abel3 to the formalism of Caputo4.

Fractional derivatives are generally computed through integrals that depend on the values of a function over an entire interval5, so the equations they enter are said to be nonlocal. Fractional derivatives are thus well suited to describe nonlocal physical phenomena, either in time (memory) or in space (long-range interaction). They have been investigated in physical systems such as ferromagnetism6, nonlocal elasticity7,8, phase separation9, ultrasound10, porous media11, anomalous diffusion12, and non-diffusive transport in plasmas13. However, it is a recent generalisation of quantum mechanics to the fractional case14 that has led to an increased interest in fractional derivative models.

In fractional quantum mechanics, a fractional Laplacian enters as a (fractional) kinetic energy operator14,15,16 when replacing the statistics of Brownian motion in the calculation of path integrals by that of Lévy flights14,17. This leads to the fractional Laplacian operator \({(-{\nabla }^{2})}^{\alpha /2}\), with the Lévy index 0 < α < 2 1,17,18, which reverts to the usual Laplacian when α = 2. Lévy flights can be found throughout science, including, for example, in earthquake statistics19 and in the search strategies of predators20. Even though fractional Laplacians have been defined in as many as 10 different ways, it has been shown that all of these are equivalent21.

The Laplacian operator is fundamental to wave models, including the widely used nonlinear Schrödinger (NLS) equation. The generalisation of the Laplacian to the fractional case, and therefore the emergence of a fractional nonlinear Schrödinger equation, has prompted significant interest in fractional nonlinear wave theory. Rogue waves22, optical vortex solitons23, spin-orbit coupled solitons in Bose-Einstein condensates24, and dissipative solitons25 have all been found in fractional nonlinear wave equations. In applied mathematics, the nature of the ground state26,27, the well-posedness of the equations28,29, and the “blow-up” of the solutions30,31, depending on the parameter α, have all been studied. However, despite this considerable interest from multiple large communities, the absence of associated experiments is striking.

Optics is one of the most promising fields for the experimental realisation of physical systems with fractional Laplacians, because of its mature technology and the direct link between the model equations and the underlying physics. Indeed, the linear fractional propagation of light beams has already been studied theoretically32,33,34, and demonstrated experimentally35,36. However, these experiments considered free propagation, which, in the context of quantum mechanics, corresponds to the simple case of evolution without an external potential. In fact, any comprehensive experimental investigations of a fractional Laplacian with a potential, either linear or nonlinear, have yet to be reported.

Here, we provide such a demonstration: we report the generation and full characterisation of temporal solitons governed by a fractional Laplacian. To understand how a fractional Laplacian is represented in our optical experiment, we first consider the conventional case of the nonlinear Schrödinger equation, in which a second derivative operator (∣β2∣/2)(∂2/∂t2), where β2 is the dispersion coefficient, in the time domain, corresponds to a parabolic dispersion relation in frequency. This can be seen by application of the operator to e−iωt, where ω is the frequency, which leads to − ∣β2∣ω2/2 (see Fig. 1a, b). This relationship is valid in a co-moving frame in which any constant speed, represented by a linear relationship, vanishes. Similarly, a fractional Laplacian is represented in the frequency domain by an associated (non-parabolic) dispersion relation. As discussed in more detail in section “Experimental results”, we conduct our experiments using a fibre laser in which arbitrary dispersion relations can be applied by the use of a programmable phase mask37.

a–e Conventional solitons can form in the presence of quadratic dispersion. a Equivalence of the dispersion operator in the time and frequency domains. b The dispersion (red) and (inverse) group velocity (dashed green) vary smoothly with frequency ω. The dot dashed vertical line marks the soliton central frequency ω0. c At low intensities I, dispersion stretches pulses in time. Solitons can form at high intensities with smooth (d) spectral and (e) temporal profiles that decay exponentially. f Corresponding dispersion operator for Hilbert-NLS solitons. g The dispersion relation Eq. (1) has a discontinuous (disc.) derivative (red) and associated discontinuous (inverse) group velocity (dashed green) as a function of frequency; h At low intensities, the dispersion causes input pulses to split in two. At high intensities, solitons form, which have (i) a spectrum with discontinuous derivative, and (k) non-exponential decay in time. The units are arbitrary, and the intensity profiles in (d, e, i) and (k) are on logarithmic scales.

Here, we consider the dispersion relation

and show in section “Hilbert-nonlinear Schrödinger equation” that it corresponds to a fractional Laplacian with α = 1. Here ω0 is the central frequency. The inverse group velocity \({v}_{g}^{-1}\) (in the co-moving frame) is related to the wavenumber by \({v}_{g}^{-1}=d\beta /d\omega\). Thus for ω < ω0, vg = 1/∣β1∣, whereas for ω > ω0, vg = − 1/∣β1∣. This dispersion relation and associated inverse group velocity are conceptually illustrated in Fig. 1g, and should be compared to the parabolic dispersion relation for conventional NLS solitons in Fig. 1b. At low intensities, when nonlinear effects are negligible, dispersion relation in Eq. (1) causes the pulse to split in two parts, with frequencies ω > ω0 speeding up and the frequencies ω < ω0 slowing down (Fig. 1h), as previously demonstrated by Liu et al.36. In contrast, in the conventional case the continuous variations of the group velocity lead to pulse broadening (Fig. 1c).

Combining the dispersion with the nonlinear properties of the optical fibre can lead to solitons. In the conventional case, described by the NLS equation, these solitons have a hyperbolic secant shape, both in frequency (Fig. 1d) and in time (Fig. 1e). They, therefore, are smooth and decay exponentially in both domains. In contrast, the dispersion relation following Eq. (1) leads to solitons with a discontinuous derivative in frequency (Fig. 1i), and which decay algebraically in time (Fig. 1k). These solitons satisfy the Hilbert-nonlinear Schrödinger (Hilbert-NLS) in Eq. (2)38 to be discussed in section “Hilbert-nonlinear Schrödinger equation”. This equation is a special case of the fractional NLS equation39, and has fractional Laplacian with α = 1.

Here, we demonstrate the unique properties of Hilbert-NLS solitons using spectral, temporal, and phase-resolved measurements, and compare these with the properties of the conventional solitons of the NLS equation for which α = 2. In particular, we explore (i) the intrinsic properties of the soliton shape (section “Soliton shape at α = 1”); (ii) the pulse-width dependence of the soliton energy at fixed β1 (section “Soliton energy at α = 1 with fixed β1”); and (iii) the soliton energy as β1 is varied (section “Soliton energy-dependence on β1 at α = 1”). Although we focus on the case with α = 1, the flexibility of our experimental apparatus allows for the generation of solitons at any value of the Lévy index α, and we additionally demonstrate the cases α = 5/4 and α = π/2 (section “Solitons for α ≠ 1”). Taken together, these results demonstrate that fractional nonlinear phenomena can be demonstrated experimentally–they pave the way for future experiments with new analogies in quantum mechanics and many other areas of physics and applied mathematics.

Results

Hilbert-nonlinear Schrödinger equation

The propagation of light in a nonlinear medium with dispersion relation Eq. (1) is governed by the Hilbert-NLS equation38 (see “Methods”)

where φ(z,t) is the electric field envelope, z is the propagation distance, t is time, and γ is the nonlinear coefficient40. The second term in this equation corresponds to the fractional Laplacian. The operator \({{{\mathcal{H}}}}\) denotes the Hilbert transform41, an integral, (i.e., nonlocal) operator. The Hilbert transform, in essence, reverses the sign of the amplitudes of the negative frequency components of its argument, thereby expressing the absolute value in Eq. (1), followed by a multiplication by i (see also Eq (8)). More precisely, we find \({{{\mathcal{H}}}}(\partial /\partial t){e}^{-i\omega t}=-i\omega {{{\mathcal{H}}}}({e}^{-i\omega t})=-i\omega \,i\,{{{\rm{sgn}}}}(\omega ){e}^{-i\omega t}=| \omega | {e}^{-i\omega t}\) 41 as illustrated in Fig. 1f. To see that this term corresponds to the fractional Laplacian \({(-{\nabla }^{2})}^{1/2}\) we consider the square of the operator, i.e.,

where we used that the Hilbert transform and taking a derivative commute, and that \({{{\mathcal{H}}}}{{{\mathcal{H}}}}=-\!\!{{{\mathcal{I}}}}\), with \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}\) the identity operator41. This finding is consistent with Kwasnicki, who showed that the operator in the second term in Eq. (2) corresponds to the fractional Laplacian with α = 1 according to Riesz21. The Hilbert transform is further discussed in the Methods section. We note that Eq. (2) also arises in the study of ferromagnetism6 and in the quasi-continuum limit of investigations of nonlinear, one-dimensional systems with long-range dispersive interactions38.

In our experiments, we generate optical pulses that have an intensity that remains unchanged upon propagation37,42. Such stationary solutions u(t) of Eq. (2) are defined through φ(z,t) = u(t)eiμz—where μ is a nonlinear contribution to the propagation constant—and satisfy

Although analytic solutions to Eq. (4) are not known, from its general properties, combined with numerical solutions43, we can find that these solitons have unique features that differ substantially from those of the conventional hyperbolic secant solitons40.

To highlight the difference between Eq. (2) and the conventional NLS equation, we consider their scaling relations. For example, it is straightforward to see that if φ(t, z) = u(t)eiμz is a solution of Eq. (2), then so is \(\tilde{\varphi }(t,z)=\eta \,u({\eta }^{2}t)\,{e}^{i{\eta }^{2}\mu z}\), where η is real and positive. This relies on the property of Hilbert transforms that if \(g(t)={{{\mathcal{H}}}}(f(t))\), then \(g(at)={{{\mathcal{H}}}}(f(at))\) for any real, positive a41. The scaling relation between φ and \(\tilde{\varphi }\) means that the pulse energy ∫∣φ∣2dt is independent of μ; the pulse energy thus does not depend on the pulse length at constant β1 and γ and it therefore is, in effect, quantised. From this, and other such relations (see “Methods”), it can be shown that

where K is a constant. From numerical calculations, it is found to take the value K = 2.47. This is a firm prediction which we confirm experimentally in section “Soliton energy at α = 1 with fixed β1”. It contrasts strongly with conventional solitons for which the pulse energy E ∝ 1/Δt, where Δt is the pulse length.

Experimental results

Our experiments are performed using a passively mode-locked fibre laser that incorporates an intracavity pulse shaper42,44. The pulse shaper (i) applies a phase that cancels the second- and third-order dispersion introduced by the optical fibre, so that the effects of these orders are negligible, and it also (ii) generates a dominant phase as ϕ(ω) = − ∣β1∣∣ω − ω0∣L, where L is the cavity length, consistent with Eq. (1) (see Supplementary Information Section 1). The output pulses are characterised through a set of temporal and phase-resolved measurements using a frequency-resolved electrical gating (FREG) apparatus (see “Methods”)45.

As discussed in more detail in the “Methods” section, the stationary solutions of Eq. (2) are marginally stable. To address this, we add a small amount of negative quartic dispersion at frequencies far from the central frequency (see “Methods”) where the spectral soliton amplitude is low (orange curve in Fig. 2a). However, the effect of this quartic dispersion on the generated soliton remains small in our experiments as discussed below.

a Measured (solid blue) and numerical (red dashed) spectra for ∣β1∣ = 40 ps km−1. The orange curve shows the net dispersion of the cavity; the solid curve corresponds to Eq. (1), whereas the dashed curve corresponds to the quartic dispersion included to provide stability. The inset shows the simulated laser output spectrum. b Retrieved (solid blue) and numerically calculated (red dashed) temporal intensity profiles. The inset shows (u(t))−1/2 versus time.

Soliton shape at α = 1

For the results discussed here, we first apply the phase profile shown in Fig. 2a (solid orange) for which ∣β1∣ = 40 ps km−1. The corresponding output spectrum of the laser operating in the Hilbert-NLS regime is shown in Fig. 2 (solid blue). It exhibits a triangular-like shape on a logarithmic scale, and is in very good agreement with the predicted shape (red dashed), calculated from solving Eq. (4) numerically43. Note the discontinuous derivative at the central frequency ω0, a consequence of the discontinuous derivative at the origin in Eq. (1). The sharp spectral peaks at low and high frequencies in Fig. 2a correspond to Kelly sidebands, resonant dispersive waves arising from perturbations when the soliton propagates around the cavity42,46. They can be ignored in our analysis.

We also modelled the laser dynamics using an iterative cavity map (see Supplementary Information Section 2)42. The simulated output spectrum of the laser, for the same parameters, is shown in the inset of Fig. 2a. It is in good agreement with the experiments and confirms that the nonlinear propagation is governed by the Hilbert-NLS equation Eq. (2).

The discontinuous derivative in the spectrum causes u(t) to be proportional to 1/t2 (i.e., I(t) ∝ 1/t4) as ∣t∣ → ∞ (see Fig. 1k), and is a manifestation of the nonlocal nature of the fractional Laplacian; the solutions thus decay algebraically unlike the exponential decay of conventional solitons40. This is confirmed in Fig. 2b, where the retrieved temporal intensity (solid blue) decays sublinearly on a logarithmic scale. This indicates slower-than-exponential decay, again in very good agreement with the predicted shape (red dashed). The small oscillations in the retrieved temporal shape arise from the quartic dispersion that is introduced to suppress the instabilities (see Supplementary Information Section 3). The inset of Fig. 2b shows the same data but with \(u{(t)}^{-\frac{1}{2}}\) on the vertical axis. Presented this way, the data is a straight line far from the origin, consistent with the expected algebraic decay.

The time-bandwidth product ΔfΔt—the product of the full-width at half maximum (FWHM) of the spectral and temporal intensities—is characteristic for a particular pulse shape. For conventional hyperbolic secant solitons, for example, it takes the value 0.31540. For the soliton solutions to Eq. (4), it takes the extremely small value ΔfΔt = 0.063 based on numerical calculations. By measuring the FWHM of the pulses in Fig. 2(a) and (b), we find Δf = 0.046 THz and Δt = 1.81 ps, corresponding to a time-bandwidth product of 0.083. The fact that this is almost four times smaller than for hyperbolic secant pulses highlights the marked difference between the pulses we generate and conventional solitons. The small discrepancy of the measured time-bandwidth product with the theoretical value is likely due to residual chirp in our dispersion-managed laser configuration42.

Soliton energy at α = 1 with fixed β 1

As discussed in section “Hilbert-nonlinear Schrödinger equation”, the energy E of the soliton solutions of Eq. (2) is given by Eq. (5), and is independent of the pulse duration Δt. We verify this prediction by measuring the output pulse duration and energy for different pump powers. We deduct the portion of the energy in the spectral sidebands by integrating the corresponding measured optical spectrum. Results of these measurements are shown in Fig. 3a (blue circles), and are in good agreement with the predicted soliton energy calculated from Eq. (5) for the same parameters (solid red) once we account for the output coupling and insertion loss of the spectral shaper42. The measured output energy varies by only approximately 17% as the pulse width varies by a factor 3. On the other hand, the expected energy of conventional solitons for the parameters of our laser cavity is shown by the dashed green curve and follows a 1/Δt-dependence (see “Methods”)40,42. For these conventional pulses, therefore, the pulse energy changes by a factor 3 as the pulse duration varies by the same factor. The observation that the soliton energy is approximately constant as the pulse width varies by a factor 3 indicates once more the clear difference between the solitons we generate and conventional NLS solitons.

a Measured pulse energy E versus pulse duration Δt (blue circles) for ∣β1∣ = 30 ps km−1. The red line shows the predicted energy from Eq. (5). The dashed green line shows the energy scaling of the conventional NLS soliton for our cavity fibre parameters (see “Methods”). b Measured energy versus number of Hilbert-NLS solitons co-propagating in the cavity. The error bars were derived from average power measurements.

For larger pump powers, the laser cavity can sustain several solitons propagating at the same time. As Eq. (5) predicts that the energy of each pulse is equal, the total soliton energy in the cavity jumps as the pump power is changed and the number of solitons in the cavity changes. We measure the output pulse train using a slow photodetector and oscilloscope for up to np = 5 solitons in the laser cavity. The energy of each pulse is then calculated by integrating the recorded temporal trace and dividing by np. In all cases, we find that, (i) the energy of each soliton is consistent with Fig. 3a and is approximately constant over the pump power range for which a given number of pulses exist in the cavity (see Supplementary Information Section 4); and (ii) the energy of the total number np of solitons is np times the energy of a single soliton. Experimental confirmation is provided in Fig. 3b. It shows that the output energy of the laser jumps by approximately 52 pJ as an additional soliton enters the cavity, consistent with Eq. (5).

We note that the quantisation of the pulse energy is not novel in itself. Grudinin et al.47 for example, reported a laser with this property. However, in their case, the fixed energy arises from the properties of the gain medium and the mode-locker. In contrast, in our work, it is entirely due to the phase properties of the cavity.

Soliton energy-dependence on β 1 at α = 1

Equation (5) also predicts that the pulse energy is linearly proportional to the magnitude of the dispersion coefficient β1, which can be arbitrarily adjusted by the intracavity pulse-shaper42. We repeated the measurements from section “Soliton energy at α = 1 with fixed β1” but for different values of the dispersion coefficient β1. We measured the energy for np = 2 and np = 5 solitons and divided this energy by 2 and 5, respectively. The results of this are shown in Fig. 4 and are in excellent agreement with the prediction from Eq. (5). In particular, the line drawn through the data intersects the vertical axis close to the origin, as required. All of the results presented in this section confirm that the solitons observed in this work correspond to the case α = 1 and are governed by the Hilbert-NLS equation (Eq. (2)).

Solitons for α ≠ 1

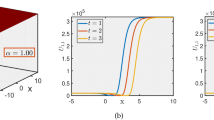

Finally, we report the generation of other fractional NLS solitons for Lévy indices α ≠ 1. Using the same experimental approach as discussed above, we apply a phase profile \(\phi (\omega )=-\frac{| {\beta }_{\alpha }| }{\alpha !}| (\omega -{\omega }_{0}){| }^{\alpha }L\) with α1 = 5/4 and α2 = π/2. Here the ∣βα∣ are constants with units of m ⋅ s−α, and α! is evaluated using the Gamma function, i.e., α! = Γ(α + 1). The numerical values of ∣βα∣/α! are chosen such that the generated solitons have bandwidths that are similar to that for α = 1. We again apply weak negative quartic dispersion to improve the soliton stability.

The measured spectra (solid blue curve) corresponding to α1 = 5/4 and α2 = π/2 are shown in Fig. 5a, b, respectively, and are again in very good agreement with the numerically predicted profiles (red dashed) and previous numerical studies17,48. When no phase is applied by the pulse shaper, the laser operates in the conventional NLS soliton regime (α3 = 2). The intrinsic anomalous negative second-order dispersion of the fibre then balances the Kerr nonlinearity (see “Methods”) and the output pulses exhibit the well-known hyperbolic secant spectrum, as seen for comparison in Fig. 5c. These measured spectra show that the discontinuous derivative in Fig. 2a “softens” as α → 2 for which case the spectrum is smooth. The associated calculated temporal intensity profiles of these solitons are shown in Supplementary Information Section 5.

Dispersion relations \(\beta (\omega )=-\frac{| {\beta }_{\alpha }| }{\alpha !}| (\omega -{\omega }_{0}){| }^{\alpha }\) are indicated by solid orange curves, whereas dashed orange curves correspond to the quartic dispersion included to provide stability. Solid blue curves are measured spectra, whereas numerically calculated spectra are red dashed. a α1 = 5/4 and \({\beta }_{{\alpha }_{1}}/{\alpha }_{1}!=-30\,\,{{{{\rm{ps}}}}}^{{\alpha }_{1}}\,{{{{\rm{km}}}}}^{-1}\); b α2 = π/2 and \({\beta }_{{\alpha }_{2}}/{\alpha }_{2}!=-\!\!15\,\,{{{{\rm{ps}}}}}^{{\alpha }_{2}}\,{{{{\rm{km}}}}}^{-1}\); and (c) α3 = 2 and β2/2! = − 10.7 ps2 km−1, the dispersion of single-mode fibre (see “Methods”).

These results confirm the versatility of our experimental setup and its ability to generate solutions to a large range of nonlocal and nonlinear wave equations.

Discussion

We have provided the first comprehensive experimental realisation of fractional solitons by harnessing the interaction between fractional dispersion, associated with a fractional Laplacian, and the Kerr nonlinearity in a fibre laser cavity. We focused on solitons with the dispersion relation Eq. (1), and for which the solitons are described by the Hilbert-NLS equation (2). In a sense, this case, for which α = 1 and the conventional NLS, for which α = 2 are extremes in the usual interval 0 ≤ α ≤ 2 since for α < 1 the solitons are unstable (see “Methods”). However, we show in section “Solitons for α ≠ 1” that our experimental approach is flexible enough to dial in any value 1 ≤ α ≤ 2, allowing in-depth studies of other fractional regimes49.

Fractional Laplacians are nonlocal operators, and indeed this property enters Eq. (2) through the presence of the Hilbert transform. This leads to the discontinuity in the derivative of the spectrum, which in turn leads to the non-exponential asymptotic temporal behaviour of the solutions. The nonlocality makes it difficult to find analytic solutions of Eq. (4) since approaches that rely on local or asymptotic expansions cannot be used. Even though closed-form solutions to the Benjamin-Ono equation50, which also involves a Hilbert transform and which is somewhat related to Eq. (4)51, are known, these solutions do not carry over to the present case.

In conclusion, we report the generation and full characterisation of nonlocal solitons that satisfy the Hilbert-NLS equation, a special case of the fractional NLS equation. These solitons have striking properties, summarised below, for which applications may be developed in future, for example in telecommunications or in laser physics.

-

The soliton spectrum has a discontinuous derivative, which reflects the discontinuous derivative of the dispersion relation Eq. (1). In turn, this discontinuous derivative leads to non-exponential asymptotic decay in time. This reflects the nonlocal properties of the Hilbert transform that enters the fractional Laplacian.

-

These solitons have a very small time-bandwidth product, much smaller than that of conventional solitons. This can be attributed to the compact spectrum, which is a consequence of the discontinuous derivative. Even though the algebraic decay implies a broad spectrum, this is not yet apparent at the relatively high intensities that determine the solitons’ FWHM.

-

The soliton energy is independent of their peak power or width.

Our theoretical model is sufficient for all the cases considered here, even though it is based on a conservative Hilbert nonlinear Schrödinger equation. It is in very good agreement with both our experimental results and with numerical simulations based on an iterative map model, consistent with earlier studies of stationary solutions in similar systems with non-fractional dispersion relations42.

While our experiments were carried out in an optics context, our results are universal and agnostic to the particular physical embodiment of the governing equation. As such, our results can act as a starting point for a new wave of experimental investigations of linear and nonlinear wave phenomena in media with fractional dispersion relations.

Methods

Hilbert-nonlinear Schrödinger equation

The nonlinear Schrödinger (NLS) equation with generalised dispersion and with a cubic nonlinearity takes the general form

where \({{{{\mathcal{O}}}}}_{D}\) is an operator describing the dispersion. As discusssed for the conventional NLS equation, the dispersion relation takes the form \(\beta=-\frac{1}{2}\,| {\beta }_{2}| {\omega }^{2}\) 40, where β is the wavenumber, in which case \({{{{\mathcal{O}}}}}_{D}=\left(\frac{| {\beta }_{2}| }{2}\right)\left(\frac{{\partial }^{2}}{\partial {t}^{2}}\right)\).

For the derivation of Eq. (2) in the main text, we require the Hilbert transform41

where \({{{\mathcal{P}}}}\) denotes the principal value. The Hilbert transform has the property that41

where \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\) and \({{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}^{-1}\) denote the Fourier transform and its inverse, respectively. Thus, the effect of the Hilbert transform is to reverse the signs of the amplitudes of the spectral components with negative frequencies (the factor i guarantees that the Hilbert transform of a real function is real). Since \(| \omega |=\omega \,{{{\rm{sgn}}}}(\omega )\) where \({{{\rm{sgn}}}}\) is the sign function it is not surprising that Eq. (2) involves a Hilbert transform.

Soliton scaling and instability

Equation (4) in the main text has a number of scaling properties according to which the solutions must satisfy

where f is a function that needs to be found numerically. To illustrate this, consider the following example: suppose we have a solution of Eq. (4). Then the μ dependence in Eq. (9) ensures that if u is shortened by a factor η and the amplitude increases by a factor \(\sqrt{\eta }\), then every term in Eq. (4) increases by a factor η3/2 in magnitude, so that the resulting function is also a solution.

Now the pulse energy is given by ∫u2(t)dt. Carrying out this integration we then immediately find Eq. (5). The fact that μ cancels out indicates that, for fixed β1 and γ, the pulse energy does not depend on the pulse width or peak power.

The condition for stability of solitons in conservative systems has been discussed by many authors17,52. Boulenger et al.30, for example, express it in terms of a scaling index sc

where N is the dimensionality, α is defined in the main text, and σ describes the nonlinear term through ∣φ∣2σφ. For sc < 0 the system is subcritical, for sc > 0 it is supercritical, whereas for sc = 0 it is critical. In our case N = 1, α = 1 and σ = 1, and so sc = 0, corresponding to the critical case. By comparison, for the conventional NLS equation N = 1, α = 2 and σ = 1, so \({s}_{c}=-\frac{1}{2}\), corresponding to the stable, subcritical case. The finding that sc = 0 follows from the scaling relation derived above and is equivalent to the observation that the energy E does not depend on μ, and it is thus an immediate consequence of the fact that the energy does not depend on the pulse width. In our non-conservative system, this instability manifests as a spectral asymmetry. In our numerical simulations with initial phase noise, the soliton spectrum and energy fluctuate after each round trip. Such behaviour can be arrested by applying a small additional perturbation53,54, as discussed in more detail below.

Experimental laser cavity

The total laser cavity of length L = 18.2 m is made of sections of standard telecommunication single-mode fibre (SMF-28) and a short section of erbium-doped fibre (1 m). SMF-28 has a nonlinear coefficient γ = 1.3 W−1m−1 at 1560 nm. The dispersion coefficients are β2 = − 21.4 ps2 km−1 and β3 = 0.12 ps3 km−1. As the length of erbium-doped fibre is much shorter than the total cavity length and the mode-field diameter and numerical aperture are close to that of SMF-28, we assumed similar dispersion coefficients and nonlinear coefficients.

The intracavity pulse shaper is programmed to induce a total spectral phase that: (i) compensates the second- and third-order dispersion introduced by the optical fibres, and (ii) generates a fractional Laplacian following Eq. (1). To stabilise the solitons, quartic dispersion is applied at the spectral pulse edges, beginning from the intersection points of the two dispersion curves (i.e., \(-| {\beta }_{4}| {(\omega -{\omega }_{0})}^{4}/24=-| {\beta }_{\alpha }| | (\omega -{\omega }_{0}){| }^{\alpha }/\alpha!\)) extending towards the pulse edges. The values of β4 are chosen to ensure long-term stability and a high intensity contrast (e.g., higher than 20 dB) between the central and the intersection points. Thus, β4 = − 40 ps4 km−1 is used in Fig. 2 and β4 = − 20 ps4 km−1 for the other figures. Even though the addition of a small amount of quartic dispersion leads to slight changes in the generated solitons, the overall effects—while most clear in our pulse energy measurements (see Fig. 3)—are nonetheless quite modest.

Phase-resolved spectro-temporal characterisation

The output pulses were sent into the FREG setup. The pulses were split into two branches by a 70/30 fibre-coupler; 30% of the output power was sent to a branch with a variable delay before being detected by a fast photodiode and transferred to the electrical domain. This electrical signal drove an intensity modulator that gated the optical pulses from the 70% branch of the fibre-coupler. Using an optical spectrum analyser, we measured the spectra as a function of the delay to generate the associated optical spectrograms. The spectra were recorded over a nm spectral bandwidth with a Δλ = 0.1 nm resolution, and the temporal delay was scanned over 40 ps with a 0.2 ps temporal step. The experimental spectrograms were then deconvolved with a blind deconvolution numerical algorithm (1024 × 1024 grid; retrieval errors ≤ 0.001) to retrieve the pulse amplitude and phase in the temporal domain.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and the supplementary materials are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15300723.

References

Herrmann, R. Fractional Calculus: An Introduction for Physicists. (World Scientific, New Jersey, 2011).

Ross, B. The development of fractional calculus 1695-1900. Hist. Math. 4, 75–89 (1977).

Podlubny, I., Magin, R. L. & Trymorush, I. Niels Henrik Abel and the birth of fractional calculus. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 20, 1068–1075 (2017).

Caputo, M. Linear models of dissipation whose Q is almost frequency independent—II. Geophys. J. Int. 13, 529–539 (1967).

Vásquez, L. From Newton’s equation to fractional diffusion and wave equations. Adv. Diff. Equ. 2011, 169421 (2011).

Kovalev, A. S., Kosevich, A. M., Manzhos, I. V. & Maslov, K. V. Precession soliton in a ferromagnetic film. J. Exp. Th. Phys. Lett. 44, 222 (1986).

Carpinteri, A., Cornetti, P. & Sapora, A. A fractional calculus approach to nonlocal elasticity. Europ. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 193, 193–204 (2011).

Carpinteri, A., Cornetti, P. & Sapora, A. Nonlocal elasticity: an approach based on fractional calculus. Meccanica 49, 2551–2569 (2014).

Akagi, G., Schimperna, G. & Segatti, A. Fractional Cahn-Hilliard, Allen-Cahn and porous medium equations. J. Diff. Equ. 261, 2935–2985 (2016).

Chen, W. & Holm, S. Fractional Laplacian time-space models for linear and nonlinear lossy media exhibiting arbitrary frequency power-law dependency. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 115, 1424–1430 (2004).

de Pablo, A., Quirós, F., Rodríguez, A. & Vázquez, J. L. A fractional porous medium equation. Adv. Math. 226, 1378–1409 (2011).

Yamamoto, M. Asymptotic expansion of solutions to the dissipative equation with fractional Laplacian. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 44, 3786–3805 (2012).

del-Castillo-Negrete, D. Fractional diffusion models of nonlocal transport. Phys. Plasmas 13, 082308 (2006).

Laskin, N. Fractional quantum mechanics and Lévy path integrals. Phys. Lett. A 268, 298–305 (2000).

Laskin, N. Fractional quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. E 62, 3135 (2000).

Laskin, N. Fractional Schrödinger equation. Phys. Rev. E 66, 056108 (2002).

Malomed, B. A. Basic fractional nonlinear-wave models and solitons. Chaos 34, 022102 (2024).

Mandelbrot, B. B. The Fractal Geometry of Nature. W. H. Freeman and Co Ltd, New York https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/catalog/1013748 (1983).

Sotolongo-Costa, O., Antoranz, J. C., Posadas, A., Vidal, F. & Vázquez, A. Lévy flights and earthquakes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 27, 1965–1968 (2000).

Humphries, N. E. et al. Environmental context explains Lévy and Brownian movement patterns of marine predators. Nature 465, 1066–1069 (2010).

Kwaśnicki, M. Ten equivalent definitions of the fractional Laplace operator. Fract. Calc.Appl. Anal. 20, 7–51 (2017).

Rizvi, S. T. R., Seadawy, A. R., Ahmed, S., Younis, M. & Ali, K. Study of multiple lump and rogue waves to the generalized unstable space time fractional nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Chaos Solitons Fract. 151, 111251 (2021).

Li, P., Malomed, B. A. & Mihalache, D. Vortex solitons in fractional nonlinear Schrödinger equation with the cubic-quintic nonlinearity. Chaos Solitons Fract. 137, 109783 (2020).

Sakaguchi, H. & Malomed, B. A. One- and two-dimensional solitons in spin–orbit-coupled Bose–Einstein condensates with fractional kinetic energy. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 55, 155301 (2022).

Qiu, Y. et al. Soliton dynamics in a fractional complex Ginzburg-Landau model. Chaos Solitons Fract. 131, 109471 (2020).

Frank, R. L. & Lenzmann, E. Uniqueness of non-linear ground states for fractional Laplacians in \({\mathbb{R}}\). Acta Math. 210, 261–318 (2013).

Seok, J. & Hong, Y. Ground states to the generalized nonlinear Schrödinger equations with Bernstein symbols. Anal. Theory Appl. 37, 157–177 (2021).

Guo, B. & Huo, Z. Global well-posedness for the fractional nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Commun. Partial Diff. Equ. 36, 247–255 (2010).

Sy, M. & Yu, X. Global well-posedness for the cubic fractional NLS on the unit disk. Nonlinearity 35, 2020 (2022).

Boulenger, T., Himmelsbach, D. & Lenzmann, E. Blowup for fractional NLS. J. Funct. Anal. 271, 2569–2603 (2016).

Klein, C., Sparber, C. & Markowich, P. Numerical study of fractional nonlinear Schrödinger equations. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 470, 20140364 (2014).

Longhi, S. Fractional Schrödinger equation in optics. Opt. Lett. 40, 1117–1120 (2015).

Zhang, Y. et al. Propagation dynamics of a light beam in a fractional Schrödinger equation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 180403 (2015).

Zhang, L. et al. Propagation dynamics of super-Gaussian beams in fractional Schrödinger equation: from linear to nonlinear regimes. Opt. Express 24, 14406–14418 (2016).

Davis, J. A., Smith, D. A., McNamara, D. E., Cottrell, D. M. & Campos, J. Fractional derivatives—analysis and experimental implementation. Appl. Opt. 40, 5943–5948 (2001).

Liu, S., Zhang, Y., Malomed, B. A. & Karimi, E. Experimental realisations of the fractional Schrödinger equation in the temporal domain. Nat. Commun. 14, 222 (2023).

Runge, A. F. J. et al. Infinite hierarchy of solitons: Interaction of Kerr nonlinearity with even orders of dispersion. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 013166 (2021).

Gaididei, Y. B., Mingaleev, S. F., Christiansen, P. L. & Rasmussen, K. Ø. Effects of nonlocal dispersive interactions on self-trapping excitations. Phys. Rev. E 55, 6141 (1997).

Kirkpatrick, K. & Zhang, Y. Fractional Schrödinger dynamics and decoherence. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom 332, 41–54 (2016).

Kivshar, Y. S. & Agrawal, G. P. Optical Solitons: from Fibers to Photonic Crystals. (Academic Press, San Diego, 2003).

King, F.W. Hilbert Transforms. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2009).

Runge, A. F. J., Hudson, D. D., Tam, K. K. K., de Sterke, C. M. & Blanco-Redondo, A. The pure-quartic soliton laser. Nat. Photonics 14, 492–497 (2020).

Yang, J. Nonlinear Waves in Integrable and Nonintegrable Systems. (2010).

Mao, D. et al. Synchronized multi-wavelength soliton fiber laser via intracavity group delay modulation. Nat. Commun. 12, 6712 (2021).

Dorrer, C. & Kang, I. Simultaneous temporal characterization of telecommunication optical pulses and modulators by use of spectrograms. Opt. Lett. 27, 1315–1317 (2002).

Kelly, S. M. J. Characteristic sideband instability of periodically amplified average soliton. Electron. Lett. 28, 806–807 (1992).

Grudinin, A. B., Richardson, D. J. & Payne, D. N. Energy quantisation in figure eight fibre laser. Electron. Lett. 28, 67–68 (1992).

Wang, Z., He, M., Ling, X., Zhang, L. & Zhao, C. Numerical investigation of the fractional-soliton mode-locked fiber laser. Opt. Lett. 49, 5499–5502 (2024).

Liu, S. et al. Experimental emulator of pulse dynamics in fractional nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Laser Photonics Rev. 19, 2401714 (2025).

Benjamin, T. B. Internal waves of permanent form in fluids of great depth. J. Fluid Mech. 29, 559–592 (1967).

Roudenko, S., Wang, Z. & Yang, K. Dynamics of solutions in the generalized Benjamin-Ono equation: A numerical study. J. Comput. Phys. 445, 110570 (2021).

Vakhitov, N. G. & Kolokolov, A. A. Stationary solutions of the wave equation in a medium with nonlinearity saturation. Radiophys. Quantum Electron. 16, 783–789 (1973).

Gaididei, Y. B., Schjødt-Eriksen, J. & Christiansen, P. L. Collapse arresting in an inhomogeneous quintic nonlinear Schrödinger model. Phys. Rev. E 60, 4877–4890 (1999).

Stephanovich, V. A. & Olchawa, W. Stabilization of 1d solitons by fractional derivatives in systems with quintic nonlinearity. Sci. Rep. 12, 384–113 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Australian Research Council (ARC) Centre of Excellence in Optical Microcombs for Breakthrough Science (project no. CE230100006), funded by the Australian Government. A.F.J.R. is supported by the ARC Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE220100509). V.T.H., A.F.J.R. & C.M.d.S. are also supported by an ARC Discovery Project (DP230102200). The authors thank Professor Panayotis Kevrekidis for useful discussions in the early phases of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.T.H. performed the experiments and numerical simulations. A.F.J.R. designed the experimental setup. J.W. performed early experiments and numerical simulations. Y.L.Q. and M.L. performed numerical simulations. T.J.A. and C.M.d.S. carried out the theoretical analysis. A.F.J.R. and C.M.d.S. supervised the overall project. All of the authors contributed to the interpretation of the data and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoang, V.T., Widjaja, J., Qiang, Y.L. et al. Nonlinear wave propagation governed by a fractional derivative. Nat Commun 16, 5469 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60625-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60625-4