Abstract

Deep crustal shear zones, fundamental to the dynamics of terrestrial plate tectonics, exhibit complex processes of initiation and evolution that are yet to be comprehensively quantified across both long and short temporal scales. Conventionally, thermo–mechanical models posit that crustal rock behaviour is dominated by monomineralic aggregates undergoing processes like intracrystalline plastic deformation by dislocation creep. However, high-pressure and temperature conditions in crustal rocks involve minerals with extremely strong mechanical properties, challenging strain localization theories. Drawing on deformation experiments performed at eclogite-facies conditions, our research reveals that strain is efficiently localized through dissolution–precipitation creep, operating at notably lower stresses than dislocation creep. Strain accommodation and mass transfer are episodically accelerated by local transient fluid flow resulting from grain boundary movements, fracturing and densification reactions. Our results illuminate the interconnected thermo–hydro–mechanical–chemical processes underpinning crustal shear zone development, regardless of the plastic strength of mineral phases. We advocate that the inception and progression of subduction plate interfaces are predominantly steered by local transient changes of rheology beyond the seismogenic zone. Such changes are rooted in the chemical disequilibrium and fluid concentration of the slab materials, including sediments and mafic to ultramafic rocks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite extensive research over the years, the weakening mechanisms that govern strain localization at subduction interfaces, spanning from the downdip boundary of the seismogenic zone (∼350 °C) to the mechanical coupling transition with the upper plate mantle near sub-arc depths (> 600 °C)1,2,3, are still debated. This is primarily due to (i) the ambiguous rheology of crustal rocks buried at great depths, and (ii) the elusive relationship between metamorphism and deformation in viscous shear zones4,5. Flow laws (i.e., experimentally derived equations relating stress to strain rate) have only been determined for a few monomineralic and nominally anhydrous aggregates (e.g., quartz, feldspar, pyroxene) that deform at thermodynamic equilibrium by solid-state mechanisms (i.e., dislocation creep, diffusion creep)6,7,8,9. Consequently, even the most recent and sophisticated thermo–mechanical models of deep crustal rocks buried along plate interfaces draw on the main assumption that the rock rheology is primarily stress- and rate-temperature-sensitive in the absence of mineral reactions10. Yet, the investigated minerals rarely form a load-bearing framework in polymineralic crustal rocks. The investigated minerals may even be absent depending on the rock composition and the pressure–temperature (P–T) conditions of deformation11,12. Furthermore, many metamorphic assemblages forming at depth consist dominantly of minerals that are known to be mechanically strong (e.g., garnet, epidote, pyroxene, amphibole)13,14,15. These observations lead to the conundrum that if dislocation creep were the dominant mechanism controlling viscous flow beyond the seismogenic zone, strain localization in deep crustal rocks and, therefore, present-day plate tectonics, would not be possible16,17.

Field observations reveal that mineral reactions are ubiquitous in viscous shear zones. At the same time, undeformed rocks can remain largely metastable despite significant changes in P–T and/or fluid conditions (like in the Alps18,19, the Caledonides20,21,22 and the Pan-African orogenic belts23). Local dissolution and precipitation processes under deviatoric stresses have long been recognized to promote brittle and viscous strain localization by complex chemo–mechanical processes including pressure solution3,4,13,24, diffusive mass transfer25,26, fluid flow27,28,29,30 and nucleation of fine-grained aggregates18,22,31,32,33. Probing the interplay between stress, strain, fluid and metamorphism is, therefore, critical to better constrain the effective distribution of mineral reaction and crustal deformation (by dislocation creep, diffusion creep, dissolution–precipitation creep and/or brittle failure) along plate interfaces in both space and time3,5,17,34. Yet, quantifying the nature and importance of interconnected thermo–hydro–mechanical–chemical processes remains hindered by the general lack of experimental investigations on crustal rheology at high – to very high – pressure conditions and thermodynamic disequilibrium32,35,36,37.

This study tackles the crustal rheology conundrum by performing shear experiments at eclogite-facies conditions on a polymineralic aggregate representative of oceanic and/or lower continental crust buried and deformed far from chemical equilibrium in the presence of fluids.

Results

Experimental setup and mechanical data

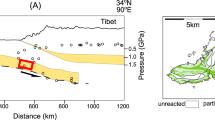

A series of four experiments was performed in a newly-designed solid-medium Griggs-type apparatus38 allowing general shear deformation at a very high confining pressure (Pc ∼2.1 GPa) corresponding to the eclogite-facies conditions (Fig. 1a,b, and Supplementary Table 1). The experiments were conducted at 850 °C and a shear strain rate varying from ∼1–5 × 10−5 s−1 due to both, the elastic stiffness of the apparatus and progressive thinning of the sample. The reactive starting material was made of plagioclase (labradorite; Pl1) and pyroxene (Px1) with 0.2 wt% of H2O added. Pyroxene consists of clinopyroxene (diopside; Cpx1) and orthopyroxene (enstatite; Opx). Reaction products formed during the experiments consist of secondary plagioclase (Pl2) and omphacite (Cpx2), garnet (Grt), quartz (Qz), coesite (Coe), kyanite (Ky), paragonite (Pg) and zoisite (Zo). This assemblage is typical of crustal rocks transformed at eclogite-facies21,39.

a Stress–strain curves displaying the mechanical evolution of the samples deformed and metamorphosed at eclogite-facies. Thick gray lines correspond to the strength for wet feldspar8 and wet quartz7 expected at the effective strain rates of the experiments (which slightly increased during the weakening stage). b Illustration (modified after ref. 38,81) of the sample assembly within a new generation Griggs-type deformation apparatus. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Experiments were stopped at different amounts of shear strain (γ), namely at peak-stress (γ ∼2) and high-strain conditions (γ ≥ 7) (Fig. 2), to constrain the chemo-mechanical evolution of the material (Figs. 3–5). The stress–strain curves are characterized by a very high peak differential stress (σd = 0.93–1.4 GPa) reached at γ ∼2 (Fig. 1a), ~50–60 h following the onset of deformation. Peak-σd is rapidly followed by a drastic weakening (between 48 and 74% of the peak stress) lasting for ∼10–20 h. Two samples eventually reached near steady-state conditions at γ ≥ 5 (Fig. 1a). Strength differences between samples can be explained by differences in the initial powder thickness. It is also worth noting that all samples deformed at stresses far below the Goetze criterion (σd ≤ Pc) representing the limit above which the samples are expected to deform by brittle mechanisms40. Moreover, none of the experiments has produced microstructures indicative for melt, such as glass films and/or pockets within grain boundaries or microfractures41.

a peak-stress experiment made of a single low strain zone (γ ∼2). b high strain experiment (γ ∼10) characterized by a strain gradient leading to the formation of a high-strain zone connecting the two tips of the opposite forcing blocks along the short diagonal (see figure inset). Orientations of the S-C and S-C’ type microstructures are highlighted in yellow.

a Overview showing reaction coronas (a few µm in width) composed of mineral products crystallizing after metastable primary phases. Red arrows point to Pl1-rich domains that have undergone full reequilibration in the vicinity of a C-type shear band (zoom in (b)). c, d Close-up views showing the intense phase mixing of reaction products crystallizing along grain boundaries of primary phases and micro-fractures. Silica polymorphs (Qz/Coe) are undifferentiated in this study.

a Overview showing the decrease of the overall grain size and the increase of the proportion of mineral products with increasing strain. b–d Close-up views within the high-strain zones showing near complete mineral equilibration. e, f Brecciation of rigid clasts of Px1 cemented by fine-grained aggregates of Cpx2 within the high-strain zones. Orange arrows point to micro-pores distributed along micro-fractures.

a peak-stress experiment. b, c high strain experiments. Pink arrows point to fine-grained reaction products preferentially formed in stress shadows, cracks, and sheared crystallization tails. Note that Pl2 and Cpx2 are significantly enriched in Na2O compared to the primary phases. Cpx2 is also slightly depleted in MgO. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Peak-stress experiment

The sample deformed up to peak-stress conditions exhibits low-strain features with an incipient foliation defined by the elongated shapes of the primary phases oriented at ∼45° to the shear plane (Fig. 2a, Fig. 3a). Strain is preferentially localized in a network of small C-type shear bands deflecting and transecting the foliation, together with thin local C’-type shear bands (Fig. 3b). Both types of shear bands (C and C’) are composed of fine-grained (≤ 5 µm) mixtures of reaction products, which are also found throughout the sample in reaction coronas around the primary phases (Fig. 3a–d). Reaction progress can locally be large enough in zones of higher strain to lead to the total replacement of Pl1 (Fig. 3b). Reaction products are also observed filling intragranular micro-fractures within the primary phases (Fig. 3c, d).

The fine-grained mixtures of reaction products consist of Zo+Qz/Coe+Cpx2+Pl2+ Ky±Grt±Pg (in order of abundance). The assemblage locally varies depending on the reactive bulk composition: Cpx2±Grt is preferentially found in Px1-rich domains and Zo+Qz+Pl2+Ky±Pg in Pl1-rich domains (Fig. 3d, Fig. 5a, and Supplementary Fig. 1). Reaction coronas generate a drastic grain size reduction (by a factor 100) along grain boundaries. The increased aspect ratio of the primary phases, with the long axis aligned parallel to the foliation plane, can be caused by intracrystalline plastic deformation and/or preferential dissolution on the interfaces at high angle to the shortening direction. Precipitation of reaction products preferentially occurs in strain shadows and low-stress sites, and eventually induces the development of deformed tails as shear bands (Fig. 3b, and Fig. 5a).

High-strain experiments

All samples deformed to γ ≥ 7 show a strain gradient leading to the formation of a high-strain shear zone connecting the two tips of the opposite forcing blocks (Fig. 2b). The strain gradient is marked by a drastic grain size reduction accompanied by a modal increase of reaction products formed at the expense of primary phases (Fig. 4a,b). The foliation, oriented at ∼45° to the shear plane in the low-strain zones, is increasingly transposed to the shear plane orientation in the high-strain zones due to the development of numerous C- and C’-type shear bands (Fig. 2b, Fig. 4a–c).

Microstructures in the low-strain zones are similar to the ones reported in the peak-stress experiment. The primary phases display asymmetric and sigmoidal reaction coronas with preferential dissolution subnormal to the shortening direction and preferential crystallization of fine-grained products in pressure shadows and tails (Fig. 4a, Fig. 5b, c).

The high-strain shear zone has a relatively large and consistent thickness among the different samples (50–60% of the final sample thickness in the sample center). Pl1 porphyroclasts are completely transformed into fine-grained mixtures (≤ 5 µm) of Zo+Qz/Coe+Ky±Pl2±Grt that are interconnected within the shear plane (Figs. 4d, e, and 5b, c, and Supplementary Fig. 1). Zoisite – the sole hydrous product (i.e., ∼2 wt.% H2O)−accounts for 30 ( ± 5) wt.% of the mixtures in Pl1-rich domains (Fig. 4b, d, e). Px1 porphyroclasts occur as partially dissolved relics with irregular grain boundaries (Fig. 6a). They act as rigid particles surrounded by fine-grained mixtures of Cpx2±Grt in stress shadows and elongated sheared tails (Fig. 4b–f, and Fig. 6a). The tails of Px1 porphyroclasts are very thin (≤ 25 µm) and interconnected by layers of Zo+Qz/Coe+Pl2+Ky (Fig. 4b–f, and Fig. 5b, c). Moreover, Px1 porphyroclasts are often fragmented by fractures that are sealed by Cpx2. Pl2 and Cpx2 are both enriched in Na compared to Pl1 and Px1. Grt is Ca-rich in Pl1-rich domains and Fe–Mg-rich in Px1-rich domains (Figs. 4d–f, and 5b, c). Grt also shows an asymmetric zoning pattern testifying to oriented crystal growth in the stretching direction (Fig. 4d).

a Phase map of a high-strain zone (OR114). Parent Cpx1 porphyroclasts (grain size > 5 µm) and new Cpx2 grains (grain size < 5 µm) are highlighted by white and gray boundaries, respectively. Non-indexed pixels are indicated by black areas (mostly corresponding to Pl1-rich domains). b Orientation map of clinopyroxene grains (Cpx1 and Cpx2) color-coded based on their crystal reference frame (inverse pole figure) with respect to the shear direction (X). c Crystallographic preferred orientation of Cpx1, Cpx2, zoisite and kyanite shown in equal-area lower-hemisphere pole figures. The latter are plotted with isocontours based on the mean orientation of grains, except for Cpx1 where all pixels are considered (see “Method” section for details and references). Number of data points (n), texture index (J), misorientation index (M) and mean grain size (GS; root mean square) are given for each set of pole figures, except for Cpx1 where the M-index is not given (not applicable). MUD = multiple of uniform distribution. d Grain size distribution, shape preferred orientation (SPO; long axis distribution) and vorticity axis distribution across subgrain boundaries (SGB) of Cpx2. Note that grains below 0.7 µm in size were not detected because of the map step size of 0.2 µm (see “Method” section). σ1 = maximum stress; σ3 = minimum stress. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) analyses show that Cpx1 porphyroclasts in high-strain shear zones have a high aspect ratio (root mean square (RMS) = 2.2), with the long axis generally oriented subparallel to the foliation plane (Fig. 6a). They also display intragranular misorientations, giving rise to subgrain boundaries (SGB)–i.e., pixel-to-pixel misorientations between 2° and 10°–and testifying to plastic deformation (Fig. 6b). Pole figures of Cpx1 indicate a strong crystallographic preferred orientation (CPO) with [001] and [100] axes subparallel and subperpendicular to the foliation plane, respectively (Fig. 6b,c). In contrast, the reaction products have a very small grain size (RMS equivalent diameter < 1.2 µm) and do not show any evidence of intragranular boundaries, except for Cpx2 (grains < 5 µm in diameter), in which the distribution of SGB vorticity axis is statistically consistent with their CPO and the dominance of {110} < 001> dislocation slip-systems42 (Fig. 6d). Although kyanite and zoisite do not show any evidence of crystal plasticity, they display a weak to moderate CPO (M-index = 0.1, J-index < 3.8) with a common pattern with that of Cpx2: the shortest principal crystallographic axis (i.e., [001] for Ky; [010] for Zo) and the longest one (i.e., [100] for both Ky and Zo) are oriented respectively subparallel and subperpendicular (to form a weak girdle) to the lineation (Fig. 6c).

Cpx2 grains exhibit a moderate aspect ratio (RMS = 1.7) and a distinct shape preferred orientation (SPO), the long axes of which cluster around the minimum stress σ3 (Fig. 6d). The SPO strengthens with increasing grain size – as does the CPO – although the latter remains weak overall with J-index lower than 2 (Fig. 7a). Grains below 2 µm in diameter, which represent more than 60% of the surface area indexed in the high strain shear zone, also have a long axis distribution primarily oriented around the direction of σ3. In contrast, coarser grains (2–5 µm) have a higher aspect ratio (RMS = 2.0) and a long axis distribution strongly aligned in the stretching direction. Remarkably, the CPO pattern remains weak (M-index ≤ 0.06; J-index < 2) and unchanged despite the significant change of SPO for the coarser grains (Fig. 7a).

a CPO, SPO and aspect ratio (AR) evolution as a function of grain size (OR114). Pole figures (PF) were constructed with isocontours using equal-area lower-hemisphere projections based on the mean orientation of grains. n = number of data point; J = texture index; M = misorientation index; MUD = multiple of uniform distribution. b, c Maps of a high-strain shear zone (zoom over Fig. 6). b Phase map of Cpx with red lines corresponding to subgrain boundaries, here defined as pixel-to-pixel lattice misorientations between 2° and 10°. c Orientation map of Cpx grains color-coded based on the orientation of their crystal reference frame (inverse pole figure) with respect to the shear direction (X). d CPO of Cpx grains displayed in equal area lower-hemisphere pole figures for different areas around a C’-type shear band, including a pressure shadow of a Cpx1 porphyroclast (blue area). While Cpx grains do not show any CPO in the pressure shadow (blue PF), a CPO develops (orange PF) and strengthens (red PF) as strain increases in the shear band. The fabric strength (J and M) remains however very weak regarding the amount of finite shear strain (γ) calculated based on the angle (38°) between the foliation (S) and the shear plane (C’)43,44. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

A close-up view of a representative area of the high-strain zone (Fig. 7b,c) reveals that Cpx2 grains adjacent to a Cpx1 porphyroclast (blue area in Fig. 7d) lack of CPO, despite clear evidence of crystal shearing at the porphyroclast rim (i.e., lattice transposition into the shear plane; Fig. 7b). The CPO of Cpx2 grains in the sheared matrix strengthens with increasing strain in the stretching direction (highlighted in Fig. 7d at the favor of a C’-type shear band; orange and blue areas). However, the intensity remains very weak (M-index < 0.1, J-index < 3.4) regarding the amount of local shear strain (γ > 5 based on the angle between the foliation and shear plane43. For such a finite strain, a minimum strength of M = 0.3 and J = 10 would be indeed expected44.

At the nm-scale, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images indicate that reaction products lack of intracrystalline deformation, in contrast to primary phases (Fig. 8a,b). A compositional change is observed between defect-free Cpx2 grains and a plastically deformed Cpx1 grain. The sharp and irregular interface between them represents the reaction front. The Na enrichment in the new Cpx2 compared to the partly dissolved Cpx1 is consistent with the jadeite substitution associated with mineral reequilibration at high-pressure conditions. All reaction products in both Pl1- and Px1-rich domains display an elongated euhedral to subhedral shape preferentially aligned in the foliation plane but the crystallographic fabric remains weak (Fig. 8b, c), as observed at larger scale. Reaction products in Pl1-rich domains show an intense phase mixing without any noticeable strength difference, except where Grt forms larger grains (10–30 µm) deflecting the main foliation (Fig. 4d). Porosity, testifying of the presence of fluids (although some of it may have formed during sample preparation), is also observed at all scales along the reaction fronts, either at grain boundaries, triple–quadruple junctions or nano- to micro-fractures (Figs. 4f, and 8b, c).

a Bright field (BF) image of a FIB foil (OR110) showing at the nm-scale the microstructures within sheared Pl1- and Px1-rich domains. Note the lack of dislocation in the reaction products (including Cpx2). b Zoom over the Px1-rich domain. The EDS map of Na shows the difference in composition between the new Cpx2 grains and the partly dissolved 'parent' grain of Cpx1. The latter has a high dislocation density, contrary to the adjacent Cpx2 grains. The white arrows illustrate the propagation direction of the reaction front. c Zoom over the Pl1-rich domain, including an EDS map of Al showing the intense phase mixing. Blue and orange arrows indicate quadruple junctions and nanopores, respectively. While BF images are highly sensitive to crystallographic orientation, the high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) images are sensitive to contrasts in atomic number.

Discussion

Development of a crustal shear zone during eclogitization

The petrological and structural evolution (deformation microstructures, mineral reactions) characterizing our high-pressure experiments is strikingly similar to that reported in crustal, “block-in-matrix” shear zones formed at or close to plate interfaces at eclogite-facies conditions (e.g., in the Alps18,39,45, the Caledonides21,36, the Cyclades46) and at amphibolite/granulite-facies (e.g., in the metamorphic soles33, the Caledonides22,47, the Western Canadian Shield48). This indicates that the chemo–mechanical constraints and processes identified in this study can likely be used to better quantify viscous plate interface dynamics, despite differences between natural and experimental conditions (e.g., temperature, strain rate, grain size).

In our experiments, the high peak-stress conditions reached during the shear zone nucleation (σd ≥ 1 GPa) are consistent with the expected strength of plagioclase in terms of intracrystalline plasticity8 (Fig. 1a). Given that plagioclase is much weaker than most minerals predicted to be stable at high-pressure conditions, such as garnet, pyroxene and zoisite14,15, we confirm that strain localization by dislocation creep in the deep crust (500–600 °C) requires unrealistically high differential stresses (> 1 GPa), even under lower geological strain rates (10−12±1 s−1).

Incipient strain localization and weakening at peak-stress conditions coincides with the interconnection of reaction coronas of fine-grained elongated reaction products (Fig. 2a). This indicates that reaction-induced grain size reduction and stress-induced growth anisotropy can generate locations of chemo–mechanical weaknesses along primary grain boundaries that eventually act as well-oriented nucleation sites for S-C and S-C’-type shear zones. Increasing strain localization leads to the formation of a wide mylonitic shear zone (Fig. 2b) characterized by a weak mechanical strength approaching the one of wet quartzite7 (Fig. 1a).

Available flow laws and deformation mechanism maps8,9 predict that dislocation creep should dominate over diffusion creep at our experimental conditions. However, this result is inconsistent with the lack of plastic deformation for most of reaction products (zoisite, kyanite) and the weak CPOs relative to the amount of shear strain (Fig. 6, Fig. 8). Moreover, neither quartz/coesite nor plagioclase constitutes the load-bearing framework of shear zones (Fig. 8c). Instead, sheared reaction products show i) an intense phase mixing, ii) a very small grain size (≤ 5 µm), iii) local variations in chemical composition, iv) nano- to micro-pores along grain boundaries and v) no crystallographic relationships with the primary grains (Figs. 4d–f, and 5b, c). Altogether, these findings are best explained by grain-size-sensitive (GSS) creep combined with fluid-assisted mineral reactions and heterogeneous nucleation processes22,32,33. Dominant dissolution–precipitation creep (DPC) associated with oriented growth and rigid body rotation here accounts for i) a strong stress-controlled SPO of the sheared reaction products, ii) no correlation between SPO and CPO for grains below 2 µm in size (which account for > 60% of the shear zone), and iii) an increase of aspect ratio with increasing grain size. The lack of dynamically recrystallized grains around the primary porphyroclasts further indicates that intracrystalline plastic deformation plays a negligible role in strain accommodation, particularly during the stage of drastic weakening. Our experiments therefore corroborate the growing body of field observations indicating that crustal shear zones are dominantly driven by DPC rather than dislocation creep47,48,49. Because intergranular fluid-assisted mass transfer is orders of magnitude faster than solid-state diffusion50, DPC can explain strain accommodation at relatively high strain rates and low magnitude of differential stress, regardless of the mineral plastic strength17,34. Furthermore, the formation of quadruple junctions is inferred to be diagnostic of grain boundary sliding (GBS), which is an essential component of GSS creep, including DPC51 (Fig. 8). Nucleation of fine-grained polymineralic assemblages and GBS enhance porosity and phase mixing, impede grain growth by grain boundary pinning and, therefore, are crucial for the long-term development of shear zones that deform by GSS creep27,28,52.

The lack of significant cracking during the shear zone nucleation (Fig. 3) indicates that viscous strain localization may not necessarily require brittle precursors, contrary to previous suggestions36,53. However, the subsequent stage of shear zone development (i.e., post peak-σd) is marked by extensive brecciation (and cementation) of the coarse-grained Px1 forming rigid clasts within a viscous matrix made of fine-grained reaction products (Figs. 4d–f, 5b,c). Such a bi-modal brittle–viscous deformation is typical of fluid-bearing “block-in-matrix” structures found in crustal shear zones of all metamorphic grades. It is a potential source of slow slip events and tremors recorded along plate interfaces3,46,54,55. The exact processes controlling brittle deformation in viscous shear zones remain nevertheless unclear in nature and our experiments. Failure may be triggered by local and transient high stress around rigid blocks within a matrix becoming increasingly weaker56,57,58 and marked by fluid flow and elevated pore-fluid pressures54,55 (see the micro-pores distributed along the fractures; Fig. 4f). High-stress concentration may also be linked to reaction-induced volume change associated to plagioclase breakdown at high-pressure conditions (∆V ≈ −15%)5,59.

Mass transfer processes and implications for dissolution–precipitation creep

The extent of mineral replacement progressively increases with strain intensity, thus reflecting the dependence of reaction kinetics on deformation and mass transfer processes13,18,60. At peak-stress conditions, after ∼140 h spent at 850 °C–2.1 GPa, the width of reaction products in low-strain domains remains limited to a few microns (Fig. 3c,d). This width is compatible with intergranular diffusivities of Al estimated in systems reaching near fluid-saturated conditions (∼10−17,−18 m2.s−1)50. Since Al is the least mobile component in the system, it is considered rate-limiting in the dissolution and precipitation processes. This indicates that fluid-assisted diffusive mass transfer likely controls reaction kinetics in quasi-static domains.

However, primary Pl1 porphyroclasts (∼100 µm) in the core of high-strain domains that developed in < 10–20 h after peak-stress conditions are fully dissolved and replaced by the reaction products (Fig. 4a–d). Such reaction kinetics are too fast (by at least ∼2 orders of magnitude) to be solely explained by intergranular diffusion, even under fluid-saturated conditions50. In addition, the large proportion of zoisite (∼30 wt.%) in these high-strain zones (Fig. 3b–e) testifies to local fluid contents (∼0.6 wt.%) exceeding by a factor 3 the amount of added water in the experiments. The spatial correlation between fluid concentration and rapid mass transfer points to the crucial role of fluid advection on reaction kinetics and, therefore, on dissolution and precipitation creep. This corroborates the plethora of field studies showing that shear zones represent preferential pathways for fluid flow and metasomatism along deep plate interfaces20,21,22,29,61,62,63,64, at a pace high enough (> 5 µm/h or cm/yr; this study; ref. 30,65) to be consistent with tectonic plate motions. Our results confirm existing models indicating that such rapid fluid flows are dynamically driven by local (µm-scale) and transient pressure gradients arising from viscous shearing27,28,66 and brittle deformation32,36,39. The creation of porosity, dilatancy and pressure gradients can also be the result of phase transformations5,64,67 as the plagioclase-breakdown reaction is associated with a large negative change in solid volume and involves the precipitation of zoisite, which may act as a fluid pump.

Dissolution and precipitation are significantly more extensive in Pl1-rich domains than in Px1-rich domains in high-strain zones (Fig. 4d, e). This observation indicates that reaction kinetics is primarily controlled by mineral reactivities where advective mass transfer is efficient. High Pl1 reactivity is related to large chemical disequilibrium68, as deformation takes place at Pc slightly below the albite = jadeite + quartz reaction69 but σ1 lying far above this reaction during most of the experiments (Fig. 1a). By contrast, solid solutions of pyroxene are predicted to remain stable over a much wider range of P–T conditions.

Differences in chemical equilibrium between the reactants explain the strength contrasts observed within the “block-in-matrix” shear zones. Reaction-induced grain size reduction is more pronounced in Pl1-rich domains than in Px1-rich domains. Due to the grain-size sensitivity of the deformation mechanisms, fully transformed Pl1-rich domains are weaker and become eventually larger and better-connected than less reactive Px1-rich domains (Fig. 4b–d). The rapid and dramatic stress drop (up to 74% of the peak stress) during strain localization is, therefore, primarily attributed to fast reaction kinetics and efficient mass transfer in Pl1-rich domains. Moreover, comparing our results with previous shear experiments conducted on similar starting materials but at lower pressures provides further evidence for the influence of local bulk composition and reaction kinetics on mechanical rock properties. At amphibolite-facies conditions (P = 0.5–1.5 GPa)32, Pl1 and Px1 are indeed significantly less reactive due to a smaller departure from chemical equilibrium. Strain localization occurs in narrower reactive shear zones that are only partially connected around coarse-grained primary phases still acting as rigid particles. Strain weakening in less reactive systems32 appears then to be much slower and less pronounced than in our experiments, supporting the dependence of strain on dissolution kinetics of stressed interfaces5,17,37.

Long- to short-term implications for the plate interface processes

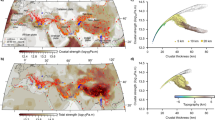

Compiling characteristics (lithologies, peak metamorphism) of exhumed materials from fossil subduction zones worldwide, including the Alps70 (Fig. 9), demonstrates a progressive increase of the proportion of mafic rocks relative to sediments with increasing depths62,71. Mafic rocks become the predominant lithology beyond the blueschist–eclogite facies transition (at T > 500–600 °C) at the kinematic plate interface in cold and mature systems. This lithological change, attributed to tectonic accretion of sediments at shallower levels72, is similarly observed during subduction initiation, although at amphibolite-facies conditions (at T > 700 °C) due to warmer thermal gradients73. Yet, numerical models still fail to predict strain localization in the deep crust as existing flow laws for feldspar, pyroxene or garnet8,14 tend to drastically overestimate the strength of the mafic crust deformed in viscous / semi-brittle shear zones.

Thermodynamic modeling for two average compositions of subducted metasediments from the Alps90 (left panel) and mid-ocean ridge basalts91 (right panel) showing the major mineral reaction boundaries and the evolution of structurally-bound H2O content (in wt.%) as a function of P and T. See “Methods” for details. The results are compared with a compilation of peak P–T estimates of subducted oceanic units from the Alps70. Note the switch in predominant lithology at the blueschist–eclogite facies transition between sediment–dominated and mafic–dominated units. Metamorphic facies are indicated in purple using the following abbreviations: EC: eclogite, BS: blueschist, GS: greenschist, Amp: amphibolite, PP: prehnite–pumpellyite. Mineral abbreviations: Law: lawsonite, Ctd: Chloritoid, Bi: biotite, Ep: epidote, Gln: glaucophane, Chl: chlorite.

By contrast, our findings highlight that changes in rheology can be expected depending on the chemical disequilibrium state of the slab materials. The effective viscosity of hydrated crustal rocks undergoing major phase transformations (in the context of significant reaction overstepping and in the presence of fluids) can decrease by ∼2 orders of magnitude, approaching that of wet quartzite (η ∼1019 Pa.s at 500–600 °C, 2.0–2.5 GPa, strain rate of 10−12 s−1; Fig. 10c). This implies that strain localization by DPC can effectively occur within the deep crust at low effective stresses (a few tens of MPa) governing viscous plate interfaces74, thus confirming previous field-based observations17,33,34.

a Representative view of reaction–induced strain localization along a deep subduction interface spanning from the downdip limit of the seismogenic zone (∼350 °C) to the slab/mantle recoupling transition (> 600 °C). The blue and red segments outline the blueschist- and eclogite-facies conditions, respectively (see Fig. 9). The figure inset represents a close-up view on the kinematic plate interface from the blueschist–eclogite-facies transition where strain is inferred to localize within the reactive crust undergoing major rock dehydration and densification.”Block–in–matrix” shear zones, developed due to differences in reactivity among mineral aggregates and lithologies, may represent the source of transient slow slips and tremors. b Predicted evolution of the structurally-bound H2O content (in wt.%) and the density for two average lithologies of metasediments from the Alps90 and mid-ocean ridge basalts91 subducted along a 8 °C/km. See Fig. 9). The P–T segments of the major rock dehydration and solid volume change in the sediments and the mafic crust are highlighted in gray. Note the strong correlation with the peak P–T estimates of the mafic-dominated units from the Alps (500–600 °C), and the large solid volume change (∆V) similar to that induced by the plagioclase-breakdown reaction in our experiments. c Conceptual model of effective viscosity (η) evolution for the mafic crust subducted along a deep plate interface. At T < 500 °C, the viscosity of the metastable crust (following the dislocation creep flow law for wet plagioclase)8 remains significantly higher than the viscosity of sediments (following the dislocation creep flow law for wet quartz)7. At T ∼500–600 °C, the viscosity of the reactive crust (controlled by dissolution–precipitation creep) drastically decreases to approach that of sediments, as demonstrated in this study. The decrease in viscosity contrast (∆η) enables strain localization within the reactive mafic crust.

Viscous strain localization below the down-dip limit of the seismogenic zone (30–40 km depths) is controlled at the slab top by the weak mechanical properties of sedimentary horizons undergoing the first main dehydration reactions (Fig. 9, Fig. 10b). Meanwhile, thermodynamic modeling shows that underlying mafic rocks remain largely metastable in absence of significant strain and reaction until they reach eclogite-facies conditions (Fig. 10b). At temperatures of 500–600 °C, the mafic rocks experience major mineral transformations leading to substantial dehydration and solid volume change75 comparable to that modeled in our experiments (∆V ∼−10%; Fig. 10b). These transformations enable the onset of DPC and, thereby, drastic strain weakening in the stressed mafic rocks (Fig. 10c). Moreover, fluid flow within heterogeneous materials (sediment, mafic, ultramafic) promotes extensive metasomatism at the kinematic plate interface and, therefore, positive feedback between mineral reactions and strain localization in the downgoing slab39,45,62 as well as in the overlying mantle wedge29,76. Differences in reactivity among mineral aggregates and lithologies induce the development of “block-in-matrix” shear zones marked by heterogeneous rheologies (Figs. 4a–d, 10a). It is also noteworthy that DPC is a transient process since reaction progress and fluid flow are unlikely to be continuous at high-pressure conditions77. Transient reaction-induced weakening and brittle deformation within “block-in-matrix” structures (Fig. 4e,f) may thus correspond to episodic slow slips and tremors3,54,55,56.

The continuous increase of P–T conditions along plate interfaces eventually results in fluid depletion and the completion of mineral reactions (Fig. 10b), both favoring grain growth and reducing the efficiency of intergranular mass transfer18,26,33. Suppression of dissolution–precipitation creep and concomitant strain hardening in the slab and the overlying mantle wedge may also bear significant implications for plate tectonics. In particular, suppression of dissolution–precipitation creep has been inferred to trigger deep slab/mantle coupling2,78, driving, in turn, the initiation and long-term development of mantle convection near sub-arc depths1 (Fig. 10a). Consequently, our study provides important perspectives, prompting a reevaluation of thermo–hydro–chemo–mechanical processes that underpin global plate tectonics.

Methods

A series of general shear deformation experiments was performed in a new generation Griggs-type apparatus (Univ. Orléans) at a temperature of 850 °C and a confining pressure of 2.1 GPa. The starting material consists of a ∼0.8 mm-thick mixed powder including 50 wt.% of plagioclase (Ca0.6Na0.4Al1.6Si2.4O8), 35 wt.% of clinopyroxene (Ca0.95Na0.05Mg0.83Fe0.12Al0.10Si1.95O6), minor amount (≤ 15 wt.%) of orthopyroxene (Mg1.55Fe0.45Al0.05Si1.95O6), and rare amphibole (hornblende). The minerals were separated from an undeformed gabbro (Arnøya, Norway), crushed in an alumina mortar and then sieved to ≤ 100 µm. An amount of ∼0.25 g of powder + 0.2 wt.% H2O was placed between 8 mm-diameter shear pistons pre-cut at 45°. Water content was chosen to increase the reactions kinetics and mass transfer during the experiments, while not inducing partial melting or mechanical pore pressure effects79. The lack of melt in the reaction products is consistent with previous experimental studies conducted under similar conditions of temperature, mineral assemblage and water content80,81.

A detailed description of the sample assembly in the Griggs-type apparatus can be found in Fig. 1b and in ref. 38 The experimental Pc–T conditions were reached by advancing σ1- and σ3-pistons by increments, alternating with heating steps. Then the σ1-piston was advanced at a constant rate through the lead piece (i.e., a run-in period of 60–90 h) before touching the top alumina piston (i.e., hit point), marking the onset of sample deformation. At the end of the experiment, the samples were quenched to 200 °C within 2 min while retreating the σ1 piston to decrease the differential stress down to 50–100 MPa and to prevent the development of unloading cracks. The samples were then brought back to room P–T conditions at a decompression rate of 5 MPa per min (during ∼7 h). Mechanical data were digitally recorded and then processed using a MATLAB program modified by J. Précigout after Pec et al. 82 (https://www.jacques-precigout.fr/ressources). Stress-strain curves from the hit-point were produced after corrections for sample compaction and surface change due to the pistons overlap. Because general shear experiment commonly experiences a significant sample thinning during deformation (see Supplementary Table 1), the shear strain was calculated from the continuous monitoring of two displacement transducers (LVDT) as the sum of individual increments of shear displacement divided by the instantaneous shear zone thickness32. As a result, shear strain of 7–10 can be generated by lateral displacements of 4–5 mm. After the experiment, the samples were impregnated with epoxy, cut parallel to the shear direction, and prepared on polished sample mounts to be analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), electron probe micro-analyses (EPMA) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

SEM imaging was performed either with a Zeiss Supra 55 VP at the Institut des Sciences de la Terre de Paris (Sorbonne Univ., Paris, France), or with a Zeiss Merlin at the Institut des Sciences de la Terre d’Orléans (Univ. Orléans, Orléans, France). Backscattered electron (BSE) images were used to quantify the proportion of zoisite in high-strain domains (where the grains are large enough to be analyzed) using the image processing software ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). EMPA mapping were obtained and quantified using a Cameca SX-FIVE at CAMPARIS laboratory (Sorbonne (Sorbonne Univ.), Paris, France) with the following analytical conditions: a 15 kV accelerating voltage, a 10 nA beam current and a 1 µm spot size. The instrument was calibrated using diopside (Ca, Mg, Si), MnTiO3 (Mn, Ti), orthoclase (K, Al), Fe2O3 (Fe), albite (Na) and Cr2O3 (Cr) as standards to measure elements in brackets. Mapping data were then processed using XMapTools 4.083. FIB foils were cut with a FEI Helios NanoLab G3 and (S)TEM observations were conducted with a FEI Talos 200FX. TEM images were acquired in bright field (BF), and STEM images in high angular annual dark field (HAADF) as well as bright-field (BF-STEM) mode.

Electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) analyses were collected using a JEOL IT800SHL SEM coupled to an Oxford Instruments EBSD system with advanced Symmetry detector at the MACLE-CVL platform (Univ. Orléans, Orléans, France). Measurements were performed on a 70°-tilted polished sample with the following analytical conditions: a 20 kV accelerating voltage, a 6 nA beam current and a 0.2 µm step size along a hexagonal grid. The resulting map was first filtered using the Oxford AZtecCrystal 2.2 software, applying a first step of wild spikes removal, and then expanding indexed grains to fill grain boundaries. To do so, we applied 3 iterations of zero-solution removal considering four identical neighbors (level 5). The indexation rates were respectively of 74% and 85% before and after cleaning. The map was then processed using MTEX, an open-source Matlab toolbox for textural analysis (version 5.8)84,85. Grain and subgrain boundaries were respectively identified by defining a 10° and 2° threshold of misorientation angle, and grains with a surface smaller than 10 pixels on several rows were discarded. The grain size was calculated using the equivalent circle diameter and the shape preferred orientation (SPO) was calculated using the long axis of the best-fit ellipse applied to each grain. A half-width angle of 10° has been used to plot textures in pole figures and to calculate the J-index86 and M-index87. The microstructural results were compared to the prediction of deformation mechanism maps for feldspar8 and pyroxene9 calculated at our experimental conditions (i.e., temperature of 850 °C, grain size ≤ 100 µm, strain rate of 10−5 s−1).

The P–T evolution of metasedimentary and mafic rocks was estimated using forward thermodynamic modeling (Perple_X)88 in the MnNCKFMASHT system using an internally consistent thermodynamic dataset (hp62ver.dat)89. The metasediment corresponds to an average metapelite composition from the Schistes Lustrés in the Alps (”avSL” from ref. 90). The mafic rock corresponds to a mean composition of mid-ocean ridge basalts (“all MORB mean” from ref. 91). The pseudosections were calculated under fluid-saturated conditions, with the following solution models: orthopyroxene, chlorite, chloritoid, white mica, biotite, staurolite and garnet92, amphibole93, clinopyroxene94, and plagioclase95.

Data availability

The authors declare that most of the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. The Source Data file (including experimental data, EBSD and EMPA data generated in this study) is available in the Zenodo database under public access (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15180640).

References

Wada, I. & Wang, K. Common depth of slab-mantle decoupling: Reconciling diversity and uniformity of subduction zones. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst., 10, Q10009 (2009).

Agard, P. et al. Slabitization: Mechanisms controlling subduction development and viscous coupling. Earth-Sci. Rev. 208, 103259 (2020).

Oncken, O., Angiboust, S. & Dresen, G. Slow slip in subduction zones: reconciling deformation fabrics with instrumental observations and laboratory results. Geosphere 17, 1–26 (2021).

Gratier, J. P., Dysthe, D. K. & Renard, F. The role of pressure solution creep in the ductility of the Earth’s upper crust. Adv. Geophysics 54, 47–179 (2013).

Putnis, A. Fluid–mineral interactions: Controlling coupled mechanisms of reaction, mass transfer and deformation. J. Petrol. 62, 1–27 (2021).

Poirier, J.-P. et al. Creep of crystals: High-temperature deformation processes in metals, ceramics And minerals. (Cambridge University Press, 1985).

Hirth, G., Teyssier, C. & Dunlap, W. J. An evaluation of quartzite flow laws based on comparisons between experimentally and naturally deformed rocks. Int. J. Earth Sci. 90, 77–87 (2001).

Rybacki, E. & Dresen, G. Dislocation and diffusion creep of synthetic anorthite aggregates. J. Geophys. Res. 105, 26017 (2000).

Dimanov, A. & Dresen, G. Rheology of synthetic anorthite-diopside aggregates: Implications for ductile shear zones. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 110, 1–24 (2005).

Gerya, T. Numerical modeling of subduction: State of the art and future directions. Geosphere 18, 503–561 (2022).

Hacker, B. R. et al. H2O subduction beyond arcs. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 9, Q03001 (2008).

Condit, C. B., Guevara, V. E., Delph, J. R. & French, M. E. Slab dehydration in warm subduction zones at depths of episodic slip and tremor. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 552, 116601 (2020).

Brodie, K. H. & Rutter, E. H. On the relationship between rock deformation and metamorphism with special reference to the behaviour of basic rocks. Metamorphic React. 4, 138–179 (1985).

Zhang, K. J., Cai, J. X., Zhang, Y. X. & Zhao, T. P. Eclogites from Central Qiangtang, northern Tibet (China) and tectonic implications. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 245, 722–729 (2006).

Yamato, P., Duretz, T. & Angiboust, S. Brittle/ductile deformation of eclogites: insights from numerical models. Geochem., Geophysics, Geosystems 20, 3116–3133 (2019).

Regenauer-Lieb, K., Yuen, D. A. & Branlund, J. The initiation of subduction: criticality by addition of water?. Science 294, 578–580 (2001).

Wassmann, S. & Stöckhert, B. Rheology of the plate interface – Dissolution precipitation creep in high pressure metamorphic rocks. Tectonophysics 608, 1–29 (2013).

Koons, P. O., Rubie, D. C. & Frueh-Green, G. The effects of disequilibrium and deformation on the mineralogical evolution of quartz diorite during metamorphism in the eclogite facies. J. Petrol. 28, 679–700 (1987).

Pognante, U. Petrological constraints on the eclogite- and blueschist-facies metamorphism and P-T-t paths in the Western Alps. J. Metamorphic Geol. 9, 5–17 (1991).

Smit, M. A. & von Strandmann, P. A. P. Deep fluid release in warm subduction zones from a breached slab seal. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 534, 116046 (2020).

Bras, E., Baïsset, M., Yamato, P. & Labrousse, L. Transient weakening during the granulite to eclogite transformation within hydrous shear zones (Holsnøy, Norway). Tectonophysics 819, 229026 (2021).

Lee, A. L., Stünitz, H., Soret, M. & Battisti, M. A. Dissolution precipitation creep as a process for the strain localisation in mafic rocks. J. Struct. Geol. 155, 104505 (2022).

John, T., Scherer, E. E., Haase, K. & Schenk, V. Trace element fractionation during fluid-induced eclogitization in a subducting slab: Trace element and Lu-Hf-Sm-Nd isotope systematics. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 227, 441–456 (2004).

Wheeler, J. Importance of pressure solution and coble creep in the deformation of polymineralic rocks. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 97, 4579–4586 (1992).

Wheeler, J. The effects of stress on reactions in the earth: Sometimes rather mean, usually normal, always important. J. Metamorphic Geol. 36, 439–461 (2018).

Stünitz, H. et al. Transformation weakening: diffusion creep in eclogites as a result of interaction of mineral reactions and deformation. J. Struct. Geol. 139, 104129 (2020).

Fusseis, F., Regenauer-Lieb, K., Liu, J., Hough, R. M. & Carlo, F. D. Creep cavitation can establish a dynamic granular fluid pump in ductile shear zones. Nature 459, 974–977 (2009).

Menegon, L., Fusseis, F., Stünitz, H. & Xiao, X. Creep cavitation bands control porosity and fluid flow in lower crustal shear zones. Geology 43, 227–230 (2015).

Soret, M. et al. Strain localization and fluid infiltration in the mantle wedge during subduction initiation: Evidence from the base of the New Caledonia ophiolite. Lithos 244, 1–19 (2016).

Kaatz, L. et al. Widening of hydrous shear zones during incipient eclogitization of metastable dry and rigid lower crust – Holsnøy, western Norway. Tectonics 40, 1–19 (2021).

Stünitz, H. & Tullis, J. Weakening and strain localization produced by syn-deformational reaction of plagioclase. Int. J. Earth Sci. 90, 136–148 (2001).

Marti, S., Stünitz, H., Heilbronner, R., Plümper, O. & Drury, M. Experimental investigation of the brittle-viscous transition in mafic rocks – interplay between fracturing, reaction, and viscous deformation. J. Struct. Geol. 105, 62–79 (2017).

Soret, M. et al. Deformation mechanisms in mafic amphibolites and granulites: record from the Semail metamorphic sole during subduction infancy. Solid Earth 10, 1733–1755 (2019).

Stöckhert, B. Stress and deformation in subduction zones: Insight from the record of exhumed metamorphic rocks. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 200, 255–274 (2002).

Getsinger, A. J. & Hirth, G. Amphibole fabric formation during diffusion creep and the rheology of shear zones. Geology 42, 535–538 (2014).

Incel, S., Renner, J. & Jamtveit, B. Evolution of brittle structures in plagioclase-rich rocks at high-pressure and high-temperature conditions—linking laboratory results to field observations. Geochem. Geophys., Geosyst. 21, e2020GC009028 (2020).

Baïsset, M. et al. Rheology of hydrated plagioclase at lower crustal conditions: Cataclasis, creep and transformational plasticity. J. Struct. Geol. 178, 105010 (2023).

Précigout, J., Stünitz, H., Pinquier, Y., Champallier, R. & Schubnel, A. High-pressure, high-temperature deformation experiment using the new generation Griggs-type apparatus. Journal of Visualized Experiments 2018, 1–14 (2018).

Locatelli, M., Verlaguet, A., Agard, P., Federico, L. & Angiboust, S. Intermediate-depth brecciation along the subduction plate interface (Monviso eclogite, W. Alps). Lithos 320–321, 378–402 (2018).

Kohlstedt, D. L., Evans, B. & Mackwell, S. J. Strength of the lithosphere: constraints imposed by laboratory experiments. J. Geophys. Res. 100, 17587–17602 (1995).

Ganzhorn, A. C. et al. Impact of gneissic layering and localized incipient melting upon melt flow during experimental deformation of migmatites. J. Struct. Geol. 85, 68–84 (2016).

Griffin, S. et al. Can the magmatic conditions of the martian nakhlites be discerned via investigation of clinopyroxene and olivine intracrystalline misorientations? J. Geophys. Res. Planets. 127, e2021JE007082 (2022).

Ramsay, J. G. Shear zone geometry: a review. J. Struct. Geol. 2, 83–99 (1980).

Hansen, L. N., Zhao, Y. H., Zimmerman, M. E. & Kohlstedt, D. L. Protracted fabric evolution in olivine: Implications for the relationship among strain, crystallographic fabric, and seismic anisotropy. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 387, 157–168 (2014).

Angiboust, S., Langdon, R., Agard, P., Waters, D. & Chopin, C. Eclogitization of the monviso ophiolite (W. Alps) and implications on subduction dynamics. J. Metamorphic Geol. 30, 37–61 (2012).

Kotowski, A. J. & Behr, W. M. Length scales and types of heterogeneities along the deep subduction interface: Insights from exhumed rocks on Syros Island, Greece. Geosphere 15, 1038–1065 (2019).

Giuntoli, F., Menegon, L. & Warren, C. J. Replacement reactions and deformation by dissolution and precipitation processes in amphibolites. J.bMetamorph. Geol. 127, e2021JE007082 (2018).

Graziani, R., Larson, K. P. & Soret, M. The effect of hydrous mineral content on competitive strain localization mechanisms in felsic granulites. J. Struct. Geol. 134, 104015 (2020).

Menegon, L., Pennacchioni, G. & Spiess, R. Dissolution-precipitation creep of K-feldspar in mid-crustal granite mylonites. J. Struct. Geol. 30, 565–579 (2008).

Carlson, W. D. Dependence of reaction kinetics on H2O activity as inferred from rates of intergranular diffusion of aluminium. J. Metamorphic Geol. 28, 735–752 (2010).

Drury, M. R. & Humphreys, F. J. Microstructural shear criteria associated with grain-boundary sliding during ductile deformation. J. Struct. Geol. 10, 83–89 (1988).

Précigout, J. & Stünitz, H. Evidence of phase nucleation during olivine diffusion creep: a new perspective for mantle strain localisation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 455, 94–105 (2016).

Mancktelow, N. S. & Pennacchioni, G. The control of precursor brittle fracture and fluid-rock interaction on the development of single and paired ductile shear zones. J. Struct. Geol. 27, 645–661 (2005).

Fagereng, A., Diener, J. F., Meneghini, F., Harris, C. & Kvadsheim, A. Quartz vein formation by local dehydration embrittlement along the deep, tremorgenic subduction thrust interface. Geology 46, 67–70 (2018).

Behr, W. M., Kotowski, A. J. & Ashley, K. T. Dehydration-induced rheological heterogeneity and the deep tremor source in warm subduction zones. Geology 46, 475–478 (2018).

Beall, A., Fagereng, A. & Ellis, S. Strength of strained two-phase mixtures: Application to rapid creep and stress amplification in subduction zone mélange. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 169–178 (2019).

Ladd, C. R. & Reber, J. E. The effect of a liquid phase on force distribution during deformation in a granular system. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 125, e2020JB019771 (2020).

Ioannidi, P. I., Pourhiet, L. L., Agard, P., Angiboust, S. & Oncken, O. Effective rheology of a two-phase subduction shear zone: Insights from numerical simple shear experiments and implications for subduction zone interfaces. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 566, 116913 (2021).

Yamato, P., Duretz, T., Baïsset, M. & Luisier, C. Reaction-induced volume change triggers brittle failure at eclogite facies conditions. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 584, 117520 (2022).

de Ronde, A. A. & Stunitz, H. Deformation-enhanced reaction in experimentally deformed plagioclase-olivine aggregates. Contributions Mineral. Petrol. 153, 699–717 (2007).

Angiboust, S., Pettke, T., Hoog, J. C. D., Caron, B. & Oncken, O. Channelized fluid flow and eclogite-facies metasomatism along the subduction shear zone. J. Petrol. 55, 883–916 (2014).

Bebout, G. E. & Penniston-Dorland, S. C. Fluid and mass transfer at subduction interfaces-the field metamorphic record. Lithos 240–243, 228–258 (2016).

Taetz, S., John, T., Bröcker, M., Spandler, C. & Stracke, A. Fast intraslab fluid-flow events linked to pulses of high pore fluid pressure at the subducted plate interface. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 482, 33–43 (2018).

Plümper, O. et al. Fluid-driven metamorphism of the continental crust governed by nanoscale fluid flow. Nat. Geosci. 10, 685–690 (2017).

Beinlich, A. et al. Instantaneous rock transformations in the deep crust driven by reactive fluid flow. Nat. Geosci. 13, 307–311 (2020).

Précigout, J., Stünitz, H. & Villeneuve, J. Excess water storage induced by viscous strain localization during high-pressure shear experiment. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–9 (2019).

Bras, E., Yamato, P., Schmalholz, S. M., Duretz, T. & Podladchikov, Y. Y. Eclogitisation of dry and impermeable granulite by fluid flow with reaction-induced porosity: Insights from hydro-chemical modelling. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 617, 118256 (2023).

Pattison, D. R. M., Capitani, C. D. & Gaidies, F. Petrological consequences of variations in metamorphic reaction affinity. J. Metamorphic Geol. 29, 953–977 (2011).

Holland, T. J. B. The reaction albite= jadeite+quartz determined experimentally in the range 600–1200 °C. Am. Mineralogist 65, 129–134 (1980).

Agard, P. Subduction of oceanic lithosphere in the Alps: selective and archetypal from (slow-spreading) oceans. Earth-Sci. Rev. 214, 103517 (2021).

Agard, P., Plunder, A., Angiboust, S., Bonnet, G. & Ruh, J. The subduction plate interface: Rock record and mechanical coupling (from long to short time scales). Lithos 320–321, 537–566 (2018).

Menant, A., Angiboust, S. & Gerya, T. Stress-driven fluid flow controls long-term megathrust strength and deep accretionary dynamics. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–11 (2019).

Soret, M., Agard, P., Dubacq, B., Plunder, A. & Yamato, P. Petrological evidence for stepwise accretion of metamorphic soles during subduction infancy (Semail ophiolite, Oman and UAE). J. Metamorphic Geol. 35, 1051–1080 (2017).

Behr, W. M. & Platt, J. P. A naturally constrained stress profile through the middle crust in an extensional terrane. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 303, 181–192 (2011).

Angiboust, S. & Raimondo, T. Permeability of subducted oceanic crust revealed by eclogite-facies vugs. Geology 50, 964–968 (2022).

Angiboust, S. et al. Jolts in the jade factory: A route for subduction fluids and their implications for mantle wedge seismicity. Earth-Sci. Rev. 220, 103720 (2021).

Malvoisin, B. & Baumgartner, L. P. Mineral dissolution and precipitation under stress: model formulation and application to metamorphic reactions. Geochem. Geophys. Geosys. 22, e2021GC009633 (2021).

Soret, M. et al. Timescales of subduction initiation and evolution of subduction thermal regimes. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 584, 117521 (2022).

Kronenberg, A. K. & Tullis, J. Flow strengths of quartz aggregates: Grain size and pressure effects due to hydrolytic weakening. J. Geophys. Res. 89, 4281–4297 (1984).

Marti, S., Stünitz, H., Heilbronner, R., Plümper, O. & Kilian, R. Syn-kinematic hydration reactions, grain size reduction, and dissolution–precipitation creep in experimentally deformed plagioclase-pyroxene mixtures. Solid Earth 9, 985–1009 (2018).

Mansard, N. et al. Relationship between microstructures and resistance in mafic assemblages that deform and transform. Solid Earth 11, 2141–2167 (2020).

Pec, M., Stunitz, H., Heilbronner, R. & Drury, M. Semi-brittle flow of granitoid fault rocks in experiments. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 121, 1677–1705 (2016).

Lanari, P. et al. XMapTools: A Matlab©-based program for electron microprobe X-ray image processing and geothermobarometry. Computers Geosci. 62, 227–240 (2014).

Hielscher, R. & Schaeben, H. A novel pole figure inversion method: Specification of the mtex algorithm. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 41, 1024–1037 (2008).

Bachmann, F., Hielscher, R. & Schaeben, H. Texture analysis with mtex – free and open source software toolbox. Solid State Phenom. 160, 63–68 (2010).

Bunge, H. J. Textural analysis in materials sciences (Butterworth’s, London, 1982).

Skemer, P., Katayama, I., Jiang, Z. & Karato, S. I. The misorientation index: Development of a new method for calculating the strength of lattice-preferred orientation. Tectonophysics 411, 157–167 (2005).

Connolly, J. A. et al. The geodynamic equation of state: what and how. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 10, Q10014 (2009)

Holland, T. J. B. & Powell, R. An improved and extended internally consistent thermodynamic dataset for phases of petrological interest, involving a new equation of state for solids. J. Metamorphic Geol. 29, 333–383 (2011).

Bebout, G. E., Agard, P., Kobayashi, K., Moriguti, T. & Nakamura, E. Devolatilization history and trace element mobility in deeply subducted sedimentary rocks: Evidence from Western Alps HP/UHP suites. Chem. Geol. 342, 1–20 (2013).

Gale, A., Dalton, C. A., Langmuir, C. H., Su, Y. & Schilling, J.-G. The mean composition of ocean ridge basalts. Geochem., Geophysics, Geosystems 14, 489–518 (2013).

White, R. W., Powell, R., Holland, T. J. B., Johnson, T. E. & Green, E. C. R. New mineral activity-composition relations for thermodynamic calculations in metapelitic systems. J. Metamorphic Geol. 32, 261–286 (2014).

Green, E. C. R. et al. Activity–composition relations for the calculation of partial melting equilibria in metabasic rocks. J. Metamorph. Geol. 34, 845–869(2016).

Green, E., Holland, T. & Powell, R. An order-disorder model for omphacitic pyroxenes in the system jadeite-diopside-hedenbergite-acmite, with applications to eclogitic rocks. Am. Mineralogist 92, 1181–1189 (2007).

Fuhrman, M. L. & Lindsley, D. H. Ternary-feldspar modeling and thermometry. Am. Mineralogist 73, 201–215 (1988).

Acknowledgements

This project was financially supported by the Labex VOLTAIRE (ANR-10LABX-100-01) at Univ. Orléans (ISTO). It has benefited from the expertise and the facilities of the Platform Macle–CVL, which was co-funded by the European Union and Center-Val de Loire Region (FEDER). This project has received additional funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 101005611 (EXCITE Network; www.excite-network.eu) for Transnational Access conducted at UU EM and MINT facility. M.S. also acknowledges the European Research Council grant PERSISMO (grant 865411) for full support of this work. M. Ohl and I. di Carlo are thanked for analytical support on TEM and EPMA, respectively. Four anonymous reviewers are thanked for their constructive reviews and R. Neely is thanked for her editorial handling.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S. conceived the project, led the deformation experiments, completed the petro-structural study, conducted the thermodynamic modeling and wrote the manuscript. J.P. designed and contributed to perform the deformation experiments and conducted the EBSD analyses. H.S., F.O. and H.R. participated to the conception of the study. H.S. supervised the TEM analyses. O.P. provided access to the EXCITE network. A.L. provided the sample material. N.R. participated in conducting and treating the EMPA analyses. All co-authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks William Hoover, Dag Dysthe and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Soret, M., Précigout, J., Stünitz, H. et al. Deep crustal deformation driven by reaction-induced weakening. Nat Commun 16, 6407 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60692-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60692-7