Abstract

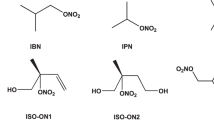

Organic nitrates (ONs) are considered as important tracers of secondary organic aerosol formation and are ubiquitous in ambient aerosols. However, the mechanisms of ON formation in the atmosphere are not well understood. Here, we show that ONs can be formed via multiphase reactions of organic peroxides with nitrite. Yields of ONs are measured as 12.8–14.9% at pH 3. The mechanism involves the recombination of a [RO• •NO2] caged radical pair resulting from the homolytic cleavage of alkyl peroxynitrite intermediate. ON yield decreases with the decreasing pH values, which may be ascribed to the positive dependence of its hydrolysis rate on the solution acidity. Additionally, it is found that the second-order rate constant of the reaction is closely dependent on pH and the molecular structure of organic peroxides. Extrapolation of kinetic and mechanistic results to the real atmosphere suggests that this pathway is important for ON formation in aerosols under typical atmospheric conditions, particularly in polluted urban areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Secondary organic aerosols (SOA) comprise a significant proportion of ambient aerosols, which profoundly affect regional air quality, climate, and public health1. Organic nitrates (ONs), that contain the functional group of -ONO2, can significantly decrease the saturated vapor of organic compounds, and are considered one of the key tracers of SOA2,3. Additionally, ONs serve as reservoirs of nitrogen oxides (NOx) by releasing NOx into the gas phase via photolysis and further oxidation4,5. ONs are ubiquitous in aerosols collected in various atmospheric environments, from clean areas to highly polluted urban areas6,7,8,9. Despite the prevalence of ONs in aerosols, their underlying formation mechanism remains unclear. Currently proposed major pathways for the atmospheric formation of ONs have included the addition of nitrate radicals (•NO3) to C=C bonds and the reactions of organic peroxyl radicals with nitric oxide (NO)10,11,12. Particulate ONs are mostly generated by gas-particle partitioning of gaseous ONs11 and the heterogeneous reaction of •NO3 with organic aerosols13. However, current atmospheric models incorporating the abovementioned pathways cannot reproduce ONs observation in ambient aerosols14, suggesting the missing sources of particulate ONs.

SOA derived from volatile organic compounds (VOCs, such as monoterpenes, isoprene, long-chain alkenes, and aromatics) contain substantial amounts of organic peroxides (POs)15,16,17. Recent studies revealed that either commercially available POs or isoprene- and monoterpene-derived peroxide mixtures, which represent a large pool of POs in the atmosphere, have unique reactivity towards sulfur dioxide (SO2), as like hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)18,19,20,21. The rate constants for some POs with S(IV) were found to be comparable to or greater than those reported for H2O2 with S(IV) under similar conditions21,22,23. Furthermore, S(IV) species other than sulfate can be partially converted into organosulfates (OSs) through nucleophilic displacement and acid-catalyzed rearrangement18. Given that nitrite (NO2−) can be oxidized by H2O2 to nitrate (NO3−)24,25,26, NO2− may also react with PO to provide an additional pathway for particulate ON formation in the atmosphere. However, there is a lack of knowledge on the kinetics and mechanisms of the reactions between PO and NO2−.

In the present study, we conducted comprehensive investigations of the kinetics and mechanisms of the multiphase reactions between NO2− and three commercially available POs (i.e., tert-butyl peroxide, 2-butanone peroxide, and cumene hydroperoxide). On-line chemical ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (ToF-CIMS) was employed to detect ONs and other products from the reactions. Effects of pH value, PO structure, and PO-to- NO2− ratio on the reactions were examined. Furthermore, by combining the laboratory results with field observation data collected from a remote site (Cape Verde) and an urban site (Beijing), the importance of this reaction to the formation of particulate ONs was evaluated. Our study reveals a significant source of ONs from multiphase reactions of PO and NO2−, which contributes significantly to SOA formation in the atmosphere.

Results and discussion

Kinetics of NO2 − oxidation by POs

Figure 1a shows the time dependence of NO2− concentration in the presence of either H2O2 or POs (i.e., tert-butyl peroxide, 2-butanone peroxide, and cumene hydroperoxide) at pH 3. In the presence of H2O2, NO2− was nearly completely consumed within 1-h reaction. NO2− was also consumed in the presence of three POs but not in their absence, indicating that they can also serve as oxidants of NO2– as well. Second-order rates of reactions between POs and NO2− were measured as well. Kinetics were quantified by reacting NO2− with an excess amount of peroxide (10 times higher). This stoichiometry enabled pseudo-first-order reaction kinetics (k′ = k × [peroxide]0) to be assumed. The calculation of rate constant is described by Eq. (1):

where k is the second-order rate constant, M−1 s−1; [peroxide]0 and [NO2−]0 are the initial concentrations of peroxide and NO2−, respectively, M. The k value for NO2− reacting with H2O2 at pH 3.01 ± 0.06 was calculated to be 2.41 ± 0.13 M−1 s−1. Lee et al.27 also measured the k value of the same reaction at pH 3.09. This value was estimated to be 2.56 M−1 s−1 after normalized to ca. zero ion strength (Supplementary Discussion), aligning with our result. The comparison result suggests that the method of kinetic measurement used in this study is reliable. Figure 1b shows that the measured reaction rate constants for three POs are of the same order of magnitude as that for H2O2. At pH 3, the k value was calculated to be 1.04 ± 0.07 M−1 s−1 for tert-butyl peroxide, 1.89 ± 0.05 M−1 s−1 for 2-butanone peroxide, and 0.87 ± 0.02 M−1 s−1 for cumene hydroperoxide, respectively. It is noted that POs used are commercially available and thus are likely to be less reactive than those found in ambient aerosols18. Therefore, it is likely that atmospherically relevant POs in aerosols could be more reactive towards NO2–.

a Time dependence of NO2− consumption in reaction without (blank (yellow)) or with peroxides (i.e., H2O2 (gray), tert-butyl peroxide (blue), 2-butanone peroxide (red), and cumene hydroperoxide (green)) at pH 3. [NO2−]0 = 0.5 mM; [peroxides]0 = 1 mM. b Second-order rate constants (k) for reaction of NO2− with each of the abovementioned peroxides at different pHs. [NO2−]0 = 0.1 mM; [peroxides]0 = 1 mM; pH: 3–4.5. All error bars represent the standard deviations calculated from experimental replicates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

As shown in Fig. 1a, NO2− is consumed much faster in reaction with 2-butanone peroxide than in reaction with tert-butyl peroxide and cumene hydroperoxide. The higher reactivity of 2-butanone peroxide may be attributed to the more –OOH group contained. Similarly, Wang et al.18 found that compared to commercially available POs with only one –OOH group, 2-butanone peroxide reacted more rapidly with SO2. Additionally, given the varied pH values in ambient aerosols (from –1 to 5)28, the effect of pH value on the reactions of NO2− with peroxides was also investigated. Compared to the number of –OOH group containing, pH value is a more significant feature affecting the reaction. That is, as the solution pH value increased, the reactivities of H2O2 and POs toward NO2− decreased. The k value at pH 3 was found to be 30 times larger than that at pH 4. Previous study revealed that the mechanism of NO2– oxidized by H2O2 is that H2O2 reacts with aqueous HONO25. The molar fraction of NO2– and HONO in the aqueous phase is significantly affected by pH value. Thus, the decrease in the k value at high pH may be ascribed to the decreased proportion of HONO in the aqueous phase. Attention should be given that there is a linear relationship between pH and lg(k). Further parameterization of k values as a function of pH for the applications in atmospheric models is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Mechanism of the formation of ONs

NO2− can be terminally converted to NO3− in the presence of H2O225. Under acidic conditions, the reaction between NO2− and H2O2 generates a reactive intermediate, namely peroxynitrous acid (HOONO). Homolysis of the O–O bond of HOONO yields a geminate pair of radicals, comprising a hydroxide radical (•OH) and a nitrite radical (•NO2). Approximately 30% of this geminate pair diffuses out of the solvent cage as free •OH and •NO2, while the remainder collapses to nitric acid (HNO3)29. Free •NO2 can rapidly undergo self-reaction to generate dinitrogen tetroxide (N2O4) and then react with H2O to produce HNO3. Additionally, HOONO can also proceed in non-radical isomerization to generate NO3− and H+. Thus, most NO2− should be converted to NO3− ultimately. In this study, we employed ion chromatography (IC) to quantify the consumed NO2− and the produced NO3−. NO3− yield was calculated to be ~98.3 ± 0.4%, which is in agreement with the theoretical value (Supplementary Fig. 1). This result also implies that during the reaction, there was negligible interference caused by HONO returning to the gas phase and by other forms of inorganic nitrogen.

Concentrations of NO2− and NO3− during the reactions of NO2− with POs were monitored as well. Time profiles of these reactions display the decrease of NO2– with a pronounced increase of NO3– (Supplementary Fig. 1), suggesting that NO3− is the dominant product. However, it is worthy of note that there was an imbalance of inorganic nitrogen (NO2− + NO3−) during the reactions. This imbalance was observed to be 14.9 ± 0.6% for tert-butyl peroxide, 14.3 ± 0.7% for cumene hydroperoxide, and 12.8 ± 0.1% for 2-butanone peroxide, respectively. As mentioned above, the gas–aqueous equilibrium of HONO as well as other inorganic nitrogen species formation could be excluded as explanations for this imbalance. Therefore, it was speculated that the formation of organic nitrogen-containing compounds, which cannot be detected by IC, caused this imbalance. Given that NO3− is the major product, a control experiment was conducted by adding PO into 0.5 mM NO3− solution to determine whether NO3− is a precursor of the proposed organic nitrogen-containing compounds. There was no change in NO3− concentration at the end of this experiment, indicating that NO3− is not the precursor. Moreover, to verify the production of organic nitrogen-containing compounds, we performed the experiment of peracetic acid (PAA), a ubiquitous PO in the atmosphere, reacted with NO2–. PAA was prepared by mixing a solution of acetic acid with H2O2. Although the acetic acid was in excess during the PAA preparation, the contribution of acetic acid to NO2– consumption can be ruled out owing to the negligible degradation of NO2– in the acetic acid/NO2– system under the same experimental conditions. Supplementary Fig. 2 shows that there also exists the inorganic nitrogen imbalance for PAA. Therefore, together with the results of commercially available POs, it can be concluded that organic nitrogen-containing compounds, most likely ONs can be produced from the oxidation of NO2– by POs.

To identify the formed ONs, on-line ToF-CIMS was employed to monitor the reaction of tert-butyl peroxide with NO2− at pH 3. A peak at m/z 120, which can be assigned to C4H10NO3+, was established to be formed during the reaction (Fig. 2). Its formation pathway was elucidated based on mechanisms of NO2− oxidized by H2O2 (Fig. 2c). In the initial step, tert-butyl peroxide reacts with HONO to yield an intermediate, C4H9OONO. Previous studies revealed that alkyl peroxynitrite (ROONO) is a short-lived species, which homolyze quickly along the O–O bond26,30,31. Goldstein et al.30 predicted that the half-life of CH3OONO in water is less than 1 µs, which is much shorter than that of HOONO (1 s)32. Although the rate constant for the homolysis of C4H9OONO has not been reported, we verified that C4H9OONO is also prone to decomposition compared to HOONO using benzoic acid (BA) as the probe (Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary Fig. 3). Formed C4H9OONO rapidly decompose into a geminate pair, [C4H9O• •NO2]. [C4H9O• •NO2] either collapses to form butyl nitrite (C4H9ONO2) or some of its constituent radicals diffuse out to form free •NO2 and C4H9O•. Finally, C4H9O• decomposes into C3H6O and a methyl radical (•CH3). It is noted that the high-intensity signal for acetone still appeared even in the background spectrum from ToF-CIMS, which overlapped with the potential C3H6O signal. Nonetheless, we observed a signal at m/z 31, corresponding to formaldehyde (HCHO) produced from the self-reaction of •CH3O2 radicals, which is the intermediate of the reaction of the •CH3 radical with O2. The observation of HCHO supports our speculation that C4H9ONO2 may arise from the recombination of caged radical pairs. Another potential pathway for the fate of C4H9OONO is isomerization to a NO3− and a carbonium ion (C4H9+). C4H9+ is terminally converted into tert-butanol by reacting with H2O (Fig. 2b). To further explore the proposed mechanism, products of NO2− oxidized by other POs (i.e., PAA and cumene hydroperoxide) were also examined. Target species such as C9H12ONO2+ and C2H4OONO2+ were detected via ToF-CIMS (Supplementary Fig. 4), suggesting that the proposed mechanism may be also appropriate for ON formation from the reactions of NO2− with other POs in the atmosphere.

a Monitoring the formation of C4H10NO3+ (m/z 120) during the 1-h reaction of tert-butyl peroxide (1 mM) with NO2– (0.5 mM) at pH 3 (red line) using online ToF-CIMS under positive mode. Blue line represents the result of the same experiments performed in the absence of NO2–. b Gas chromatography–mass spectrum of tert-butanol in sample collected after the reaction. c Proposed pathways for the formation of C4H9ONO2. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Based on the inorganic nitrogen balance derived from IC measurements, the yield of ONs from the reaction of NO2− with tert-butyl peroxide, 2-butanone peroxide, and cumene hydroperoxide were calculated to be 14.9 ± 0.6%, 12.8 ± 0.1% and 14.3 ± 0.7%, respectively. We also investigated the effects of pH value and initial NO2− concentration on the yields of ONs (Fig. 3). It is found that there is no significant variance of the ON yields by variations in the ratio of PO to NO2− concentrations. However, the yield of ONs positively depends on the pH value. At pH 4, the yield of ONs was measured as 24.3 ± 0.9% for tert-butyl peroxide, 14.5 ± 0.3% for 2-butanone peroxide, and 25.4 ± 1.9% for cumene hydroperoxide, respectively (Fig. 3a). ON can undergo hydrolysis via the acid-catalyzed mechanism to produce an alcohol and a nitrate33,34,35. Tertiary ONs were found to have hydrolysis lifetimes on the time scale of minutes to hours, whereas primary and secondary had hydrolysis lifetimes of days to months33,34,35. In addition to structure, another crucial factor is the pH value. The hydrolysis rate of ONs positively depends on the acidity of solution34,35. For instance, Rindelaub et al.34 observed that the hydrolysis rate of tertiary α-pinene-derived ONs increased from 3.2 × 105 s−1 to 2.0 × 103 s−1 when pH value decreased from 6.90 to 0.25. Thus, at pH 4, the higher yield of ONs for tert-butyl peroxide and cumene hydroperoxide may arise from the lower hydrolysis rate compared to pH 3. And the impact of pH is not remarkable for 2-butanone peroxide given that the corresponding ON with secondary substituted structure is more stable. Additionally, it seems that the yield of ONs is affected by the structures of POs. The discrepancy between these POs may be ascribed to their solubility in water. Specifically, compared with tert-butyl peroxide and cumene peroxide, 2-butanone peroxide is more soluble in water, allowing its corresponding radical to more easily escape from a radical cage and thereby inhibit the formation of ONs.

a Yields of ONs for three POs (i.e., tert-butyl peroxide, cumene hydroperoxide, and 2-butanone peroxide) at different pH values (blue: pH 3; yellow: pH 4). [NO2−]0 = 0.5 mM; [peroxides]0 = 1 mM. b ONs Yield as a function of the ratios of POs to NO2− concentration. The colors from light green to dark green represent the ratio of POs to NO2− are 10:1, 2:1 and 1:1, respectively. [NO2−]0 = 0.1, 0.5, 1 mM; [peroxides]0 = 1 mM; pH: 3. All error bars represent the standard deviations calculated from experimental replicates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Atmospheric implications

With the measured kinetic dataset, we further estimated the importance of this pathway of ON formation in the atmosphere. Specifically, it was evaluated by comparing the rate of particulate ON production via the PO oxidation pathway with that via the traditional gas-particle partition pathway under typical clean (remote) and polluted (urban) atmospheric conditions (remote: Cape Verde; urban: Beijing). Production rates for these two pathways were calculated using Eqs. (2) and (3):

where R1 is the rate of particulate ONs from the gas-particle partitioning followed by the gas phase formation process, ng m−3 h−1; R2 is the rate of particulate ONs from PO oxidation pathway without the consideration of the impacts of other PO conversion pathways in the particle phase (Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary Fig. 5), ng m−3 h−1; \({\alpha }_{1}\) and \({\alpha }_{2}\) are the gas-particle partition coefficients of ONs and POs, respectively; Pgas(ONs) is the production rate of ONs in the gas phase simulated by a chemical box model, ng m–3 h–1; [PO]gas is the concentration of POs in the gas phase simulated by the model as well, ng m–3; [NO2−] is the concentration of NO2− in aerosols, M; k is the second-order rate constant for the reaction of POs with NO2−, M–1 s–1, based on the parameterization scheme for cumene hydroperoxide as a function of pH; LWC is the aerosol water content, L m–3; and Y is the yield of ONs, %. pH and LWC were calculated using ISORROPIA II model. The performance of the model was validated by the good agreement between the observed and simulated ammonia (NH3) concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 6). The calculations of pH and LWC as well as the validation of the model are detailed in Supplementary Methods. Y was estimated to be 13%, as this was the lowest yield obtained in this study.

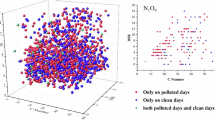

In Beijing, for the base scenario (Scenario 1: α1 = 0.2, α2 = 0.001), the production rates of particulate ONs via the PO oxidation and gas-particle partition pathways were calculated to be 118.5 and 165.5 ng m−3 h−1, respectively (Supplementary Table 2). These results indicate that the PO oxidation pathway plays an important role in particulate ON formation under polluted urban conditions. It is noted that calculated production rates are closely related to the values of α1 and α2. Some field studies showed that particulate ONs account for about 20% of the total ONs (particulate ONs + gaseous ONs) with an upper limit of 35%36,37. The gas-particle partition coefficient of POs was estimated to be 0.1–1%38. Given the varied partition coefficients for ONs and POs that have been reported, sensitivity analyses with the wide range of α1 (0–0.35) and α2 (0–0.01) values were conducted. The fraction of the PO oxidation pathway to the total particulate ON production rate in Beijing is shown in Fig. 4a. Results of sensitivity analyses confirmed that this pathway made an important contribution in most scenarios. Specifically, for the scenario (Scenario 4: α1 = 0.35 and α2 = 0.01) with the maximum values of α1 and α2, the fraction of the PO oxidation pathway was ~80% (Supplementary Fig. 7). When α2 was set to 0.001, the PO oxidation pathway still accounted for a significant fraction (29.0%) of the total production of particulate ONs even the maximum value of α1 was adopted.

Fraction of the PO oxidation pathway to the total particulate ON production rate in (a) Beijing and (b) Cape Verde at scenarios of various α1 (0–0.35) and α2 (0–0.01) values. Black asterisk represents the base scenario (Scenario 1: α1 = 0.2, α2 = 0.001). Diurnal variation of production rates of particulate ONs for these two pathways (blue line: gas-particle partition pathway; purple line: PO oxidation pathway) in (c) Beijing and (d) Cape Verde modeled under the base scenario. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Similarly, the production rates of particulate ONs from PO oxidation and gas-particle partition pathways were determined for different scenarios in Cape Verde (Fig. 4b). These rates for Cape Verde would be much lower than those for Beijing, due to the lower concentrations of precursors (e.g., NOx and VOCs) in Cape Verde. Indeed, for the base scenario (Scenario 1), the production rates of particulate ONs from the gas-particle partitioning and PO oxidation pathways both were calculated to be less than 1 ng m−3 h−1. Nevertheless, the PO oxidation pathway was competitive with the gas-particle partition pathway in the remote areas as well.

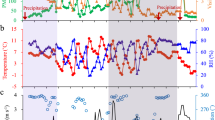

In addition, the diurnal variations in the production rate of particulate ONs were simulated for the base scenario (Scenario 1). The diurnal variation of ON production rate for the gas-particle partition pathway presents a bimodal distribution in both Beijing and Cape Verde (Fig. 4c). This may be resulted from the mechanism of ON formation that •NO3 oxidation dominates in the nighttime, and the reaction of •RO2 with NO predominates in the daytime. Which pathway is more important varies spatially. The production rate of particulate ONs in the daytime (7:00–18:00 LT) was lower than that in the nighttime (19:00–6:00 LT) in Beijing and vice versa in Cape Verde (Supplementary Table 2). Different from the gas-particle partition pathway, the PO oxidation pathway showed unimodal distribution in these two sites, reaching a maximum in the afternoon. It is expected that this pathway plays a more important role in the daytime given that POs are mainly generated from the photooxidation of VOCs. As shown in Supplementary Table 2, the PO oxidation pathway contributed to 22.0% of particulate ON production in all day, however, this fraction can increase up to 57.8% in the daytime (Supplementary Table 2). Additionally, it is noteworthy that elevated ON concentration in the afternoon has also been reported by previous field studies with unexplained mechanism9,39. For instance, Lin et al.9 reported that the concentration of secondary ONs increased in the daytime and reached a maximum at 17:00 LT in Xi’an, China. Additionally, Pye et al.14 applied the Community Multiscale Air Quality (CMAQ) model to simulate ONs in the southeastern United States. They found that particulate ON functional groups were severely underestimated in the daytime, although the upper limit of SOA yield and gaseous monoterpene-derived nitrate yield observed in laboratory experiments were used in their model. Evidences from previous field observations and model simulations further underscore the significance of the reaction between PO and NO2– as one of the missing sources of particulate ONs in the atmosphere.

Overall, the current study reveals a plausible mechanism for the formation of particulate ONs via the multiphase reactions between PO and NO2−. Crucially, the incorporation of experimentally determined kinetics and mechanistic insights into an atmospheric model enable the simulation of the production rates that are comparable to those of the traditional pathway in clean and polluted areas. The diurnal variation of this reaction aligns with previous field observations of increased concentrations of ONs in the afternoon that cannot be explained by currently established mechanisms. Therefore, our findings suggest that the pathway uncovered here may in fact be heretofore unrecognized sources of particulate ONs and SOA in the atmosphere.

Methods

Batch reactor experiments

Details of the experiments are summarized in Supplementary Table 3. Reactions were carried out in a 250 mL custom-built quartz reactor that was temperature-controlled with a water jacket. Three commercial POs, i.e., tert-butyl hydrogen peroxide (70 wt% in H2O, Sigma-Aldrich), cumene hydroperoxide (80%, Sigma-Aldrich), and 2-butanone peroxide (40%, Sigma-Aldrich), were used as representative of POs. In addition, PAA, a PO that was commonly observed in field campaigns, was employed to validate the proposed mechanism. PAA was synthesized from the solution of H2O2 mixing with acetic acid. The formation and purity of PAA was verified by nuclear magnetic resonance (Supplementary Fig. 8) and ToF-CIMS (Supplementary Fig. 9). Details about the preparation of PAA solution can be seen in Supplementary Methods. Solutions of various defined pH values (3–5, adjusted by HCl (36–38%, Hu Shi)) containing NaNO2 (0.5 mM), peroxide (1 mM), and dissolved O2 were introduced into the reactor for a total volume of 100 mL. Subsequently, the reactor was sealed and then stirred in the dark at 298 K for 2 h. NaNO2 concentration of 0.1 mM was used for kinetic studies to ensure that pseudo-first-order conditions prevailed, while NaNO2 concentrations of 0.1, 0.5, and 1 mM were used to explore the effects of the PO-to-NO2− ratio on the formation of ONs. Aliquots of ~1 mL were extracted from reaction mixtures at specific times during reactions and immediately quenched by the addition of NaOH (1 M, Macklin). The resulting quenched aliquots were immediately analyzed by IC (Dionex ICS-600). Furthermore, in some experiments, synthetic air (≥99.999%, Qingdao Weierda Gas) was continuously bubbled into solution (1 mM POs + 0.5 mM NO2−, pH 3) at 0.15 L min−1 for 1 h to carry the products into ToF-CIMS. This process enabled on-line real-time monitoring of organic products.

Reactant and product analysis

NO2− and NO3− were analyzed by IC. Anions were separated on an analytical column (AS 11-HC, 4 × 250 mm; IonPac), which was protected by a guard column (AG11-HC, 4 mm × 250 mm, IonPac) and eluted with 20 mmol L−1 potassium hydroxide at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1.

ONs and other organic byproducts were detected by ToF-CIMS (Vocus, TOFWERK) equipped with H3O+ ionization source. Details about the instrument were well described in previous studies40,41. Briefly, the ionization source was operated at 2.0 mbar pressure, and the raw mass spectra were recorded at a time resolution of 1 s and analyzed using the software package Tofware 3.2.5 in an Igor Pro 9 environment (WaveMetric, OR, USA).

Quantitative analysis for BA was performed by an ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC, Agilent 1260) coupled with a UV detector operating at 230 nm. 15 µL sample was injected into the instrument. Separation was performed on a C18 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm, particle size = 5 µm; ZORBAX SB-C18), eluting with a solution comprising 0.02 M ammonium acetate and CH3CN (95/5 v/v) at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1. Injection of BA standard shows that the retention time of BA is 5.2 min.

GC-MS (8860A-5977C, Agilent) equipped with a capillary column (length = 60 m, diameter = 0.25 mm, film thickness = 1.4 μm; EDB-624 Agilent) was employed to detect tert-butanol produced in the experiments. Specifically, a 2 μL aliquot was injected into the stainless-steel adsorption tube of the instrument. The injector temperature was set to 180 °C, the carrier gas was helium, the flow rate was 1 mL min−1, and the shunt ratio was 5:1. The column was heated at 30 °C for 5 min and the temperature was then increased to 110 °C at 10 °C min−1 and held at this temperature for 10 min to release all analytes. The analytes were detected using a quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with an electron ionization source, which had an ionization energy and a temperature of 70 eV and 230 °C, respectively. Under these conditions, molecular ions were completely fragmented into small product ions, and detailed structural information of unknown compounds could be obtained.

Collection of field observation data

Data on trace gases (CO, NO, NO2, SO2, NH3, and VOCs), water-soluble inorganic ions (NO3−, SO42−, Cl−, NH4+, Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+) in PM2.5, and meteorological parameters (i.e., T) and RH were collected from our previous observation and published literature works, and then were used for model simulation.

The observational data in Beijing were collected from a campaign conducted in summer 2021 (June 1 to September 30), as part of the Integrated Field Atmospheric Composition Test for complex air pollution in North and East China in 2021. The 1-h resolution data in August 2021 used for model simulation can be downloaded from the website (https://zenodo.org/records/15609074). More detailed information about the campaign can be seen in our previous work42. Trace gas data for Cape Verde were obtained from the website (https://ebas-data.nilu.no/) of the Cape Verde Atmospheric Observatory, which is located in the tropical North Atlantic (16.86°N, 24.87°W). Particulate data were obtained from van Pinxteren et al.43 and meteorological parameters (RH and T) were downloaded from https://rp5.ru. The average meteorological parameters and the concentrations of pollutants in Beijing and Cape Verde during the observation period (August 2021) are shown in Supplementary Table 4.

Box model simulation

Gaseous concentration of POs and the gas-phase production rate of ONs in Beijing and Cape Verde were simulated using a chemical box model. The chemical mechanism of this model was derived from the Regional Atmospheric Chemical Mechanism version 2 (RACM2)44. Physical processes, including solar radiation evolution, planetary boundary layer evolution, dry deposition, and dilution mixing, were considered within the model. The RACM2 contains 17 stable inorganic species, four short-lived inorganic species, 55 stable organic species, 43 short-lived organic species, and 363 chemical reactions. A brief description of the chemistry of ONs and POs in RACM2 is provided in the Supplementary Methods. Specific chemical reactions and kinetic data are listed in Supplementary Tables 5 and 6. Data on the diurnal variations of meteorological parameters (T and RH) and trace gas concentrations (CO, NO, NO2, SO2, NH3, and VOCs) in the average state were input at a resolution of 1 h to constrain the model. The model was pre-run for 1 day to achieve a steady state of unconstrained species. Prior to simulation, the validation of the model was examined (Supplementary Methods). Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11 show that the model can effectively reproduces the chemical processes occurring in the atmosphere, and can be employed for further simulations.

Data availability

The Beijing pollutant observation dataset is available from the website (https://zenodo.org/records/15609074). The Cape Verde pollutant observation dataset in this study is available from the EBAS database (http://ebas.nilu.no/), and the meteorological data is available from the website (https://rp5.ru). Source data are provided with this paper. The source data used in this study are available in the Figshare database under accession https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.2821099445.

Code availability

The ISORROPIA-II thermodynamic model is publicly released in http://isorropia.epfl.ch. The framework for box model running on the FACSIMILE platform is available from https://github.com/AirChem/F0AM.

References

Seinfeld, J. H. & Pandis, S. N. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: From Air Pollution to Climate Change 3rd edn (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2016).

Fry, J. L. et al. Secondary organic aerosol formation and organic nitrate yield from NO3 oxidation of biogenic hydrocarbons. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 11944–11953 (2014).

Ge, D. et al. Characterization of particulate organic nitrates in the Yangtze River Delta, East China, using the time-of-flight aerosol chemical speciation monitor. Atmos. Environ. 272, 118927 (2022).

Lee, B. H., Mohr, C., Lopez-Hilfiker, F. D. & Thornton, J. A. Highly functionalized organic nitrates in the Southeast United States: contribution to secondary organic aerosol and reactive nitrogen budgets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 1516–1521 (2016).

González-Sánchez, J. M. et al. On the importance of atmospheric loss of organic nitrates by aqueous-phase OH oxidation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 4915–4937 (2021).

Xu, L. et al. Aerosol characterization over the Southeastern United States using High-resolution Aerosol Mass Spectrometry: spatial and seasonal variation of aerosol composition and sources with a focus on organic nitrates. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 10479–10552 (2015).

Li, R. et al. Identification and semi-quantification of biogenic organic nitrates in ambient particulate matters by UHPLC/ESI-MS. Atmos. Environ. 176, 140–147 (2018).

Salvador, C. M. et al. Measurements of submicron organonitrate particles: implications for the impacts of NOx pollution in a subtropical forest. Atmos. Res. 245, 105080 (2020).

Lin, C. et al. Primary and secondary organic nitrate in Northwest China: a case study. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 8, 947–953 (2021).

Orlando, J. J. & Tyndall, G. S. Laboratory studies of organic peroxy radical chemistry: an overview with emphasis on recent issues of atmospheric significance. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 6294–6317 (2012).

Ng, N. L. et al. Nitrate radicals and biogenic volatile organic compounds: oxidation, mechanisms, and organic aerosol. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 2103–2162 (2017).

Zare, A. et al. A comprehensive organic nitrate chemistry: insights into the lifetime of atmospheric organic nitrates. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 15419–15436 (2018).

Nah, T. et al. Photochemical aging of α-pinene and β-pinene secondary organic aerosol formed from nitrate radical oxidation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 222–231 (2016).

Pye, H. et al. Modeling the current and future roles of particulate organic nitrates in the southeastern United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 14195–14203 (2015).

Docherty, K. S., Wu, W., Lim, Y. B. & Ziemann, P. J. Contributions of organic peroxides to secondary aerosol formed from reactions of monoterpenes with O3. Environ. Sci. Technol. 39, 4049–4059 (2005).

Nguyen, T. B. et al. High-resolution mass spectrometry analysis of secondary organic aerosol generated by ozonolysis of isoprene. Atmos. Environ. 44, 1032–1042 (2010).

Kautzman, K. E. et al. Chemical composition of gas- and aerosol-phase products from the photooxidation of naphthalene. J. Phys. Chem. A 114, 913–934 (2010).

Wang, S. et al. Organic peroxides and sulfur dioxide in aerosol: source of particulate sulfate. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 10695–10704 (2019).

Ye, J. H., Abbatt, J. P. D. & Chan, A. W. H. Novel pathway of SO2 oxidation in the atmosphere: reactions with monoterpene ozonolysis intermediates and secondary organic aerosol. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 5549–5565 (2018).

Yao, M. et al. Multiphase reactions between secondary organic aerosol and sulfur dioxide: kinetics and contributions to sulfate formation and aerosol aging. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 6, 768–774 (2019).

Dovrou, E., Rivera-Rios, J. C., Bates, K. H. & Keutsch, F. N. Sulfate formation via cloud processing from isoprene hydroxyl hydroperoxides (ISOPOOH). Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 12476–12484 (2019).

Wang, S. et al. Heterogeneous interactions between SO2 and organic peroxides in submicron aerosol. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 6647–6661 (2021).

Yao, M. et al. Multiphase reactions between organic peroxides and sulfur dioxide in internally mixed inorganic and organic particles: key roles of particle phase separation and acidity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 15558–15570 (2023).

Vione, D. et al. New processes in the environmental chemistry of nitrite. 2. the role of hydrogen peroxide. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37, 4635–4641 (2003).

Goldstein, S., Lind, J. & Merényi, G. Chemistry of peroxynitrites as compared to peroxynitrates. Chem. Rev. 105, 2457–2470 (2005).

Ahn, Y.-Y., Kim, J. & Kim, K. Frozen hydrogen peroxide and nitrite solution: the acceleration of benzoic acid oxidation via the decreased pH in ice. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 2323–2333 (2022).

Lee, Y.-N. & Lind, J. A. Kinetics of aqueous-phase oxidation of nitrogen(III) by hydrogen peroxide. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 91, 2793–2800 (1986).

Pye, H. O. T. et al. The acidity of atmospheric particles and clouds. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 4809–4888 (2020).

Gerasimov, O. V. & Lymar, S. V. The yield of hydroxyl radical from the decomposition of peroxynitrous acid. Inorg. Chem. 138, 4317–4321 (1999).

Goldstein, S., Lind, J. & Merenyi, G. Reaction of organic peroxyl radicals with •NO2 and •NO in aqueous solution: intermediacy of organic peroxynitrate and peroxynitrite species. J. Phys. Chem. A 108, 1719–1725 (2004).

Merenyi, G., Lind, J. & Goldstein, S. The rate of homolysis of adducts of peroxynitrite to the C=O double bond. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 40–48 (2002).

Pryor, W. A. & Squadrito, G. L. The chemistry of peroxynitrite: a product from the reaction of nitric oxide with superoxide. Am. J. Physiol. 268, L699–722 (1995).

Hu, K., Darer, A. & Elrod, M. J. Thermodynamics and kinetics of the hydrolysis of atmospherically relevant organonitrates and organosulfates. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 8307–8320 (2011).

Rindelaub, J. D. et al. The acid-catalyzed hydrolysis of an α-pinene-derived organic nitrate: kinetics, products, reaction mechanisms, and atmospheric impact. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 15425–15432 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. Synthesis and hydrolysis of atmospherically relevant monoterpene-derived organic nitrates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 14595–14606 (2021).

Rollins, A. W. et al. Gas/particle partitioning of total alkyl nitrates observed with TD-LIF in bakersfield. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 6651–6662 (2013).

Kenagy, H. et al. Contribution of organic nitrates to organic aerosol over South Korea during KORUS-AQ. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 16326–16338 (2021).

Wang, S. et al. Organic peroxides in aerosol: key reactive intermediates for multiphase processes in the atmosphere. Chem. Rev. 123, 1635–1679 (2023).

Zhu, Q. et al. Characterization of organic aerosol at a rural site in the North China Plain Region: sources, volatility and organonitrates. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 38, 1115–1127 (2021).

Krechmer, J. et al. Evaluation of a new reagent-ion source and focusing ion–molecule reactor for use in proton-transfer-reaction mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 90, 12011–12018 (2018).

Li, H. et al. Terpenes and their oxidation products in the French Landes forest: insights from Vocus PTR-TOF measurements. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 1941–1959 (2020).

Zhang, Y. J. et al. Evolution of ozone formation sensitivity during a persistent regional ozone episode in Northeastern China and its implication for a control strategy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 617–627 (2024).

Pinxteren, M. et al. Marine organic matter in the remote environment of the Cape Verde islands—an introduction and overview to the MarParCloud campaign. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 6921–6951 (2020).

Goliff, W. S., Stockwell, W. R. & Lawson, C. V. The regional atmospheric chemistry mechanism, version 2. Atmos. Environ. 68, 174–185 (2013).

Yang, Y. et al. Multiphase reactions of organic peroxides and nitrite as a source of atmospheric organic nitrates. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28210994 (2025).

Acknowledgements

L.H. acknowledges support by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC3701102), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42207121), Outstanding Young Scholar of the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China (Overseas) (2022HWYQ-010), the Program for Taishan Young Scholar (tsqnz20221107). L.X. acknowledges support by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC3701101), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42061160478). The authors thank Vicki Grassian and Shunyao Wang for helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.H. and L.X. designed research; Y.Y., L.H., M.Z., Y.W., Y.X., Q.L., W.W., and L.X. performed research; Y.Y., L.H., and L.X. analyzed data; and Y.Y., L.H., and L.X. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Huang, L., Zhao, M. et al. Multiphase reactions of organic peroxides and nitrite as a source of atmospheric organic nitrates. Nat Commun 16, 5437 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60696-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60696-3