Abstract

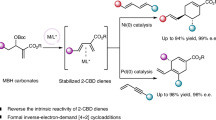

Topochemical reactions are favorable protocol in synthesizing specific polymers and realize controllable structural transformation in the crystalline state. However, their design protocol, type of reactions, and applications are very limited. Here we report a charge-transfer/Diels-Alder cascade reaction protocol to realize topochemical synthesis of chiroptical self-assembled materials with high efficiency. Imide appended 1,4-dithiin conjugates with chiral pendants feature intramolecular S‧‧‧O chalcogen bonds to afford a planar geometry, which behave as favorable electron acceptors to anthracene with high binding affinity. The charge-transfer interaction promotes the one-dimensional extension with the formation of macroscopic helical nanoarchitectures. Thermal treatment triggers the Diels-Alder reaction readily in the solution and self-assembly states, lighting up the supramolecular helical systems with absolute quantum yields up to 57%. The in situ dynamic transformation realized facile thermal-triggered display and information storage, and endowed the helical nanostructures with circularly polarized luminescence with dissymmetry factors at 10−2 grade. The cascade reaction protocol was further applied in synthesizing chiral luminescent macrocycles with potentials in chiroptical recognition and sensing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chirality endows materials with special complexity1,2,3,4,5. An intriguing property of chiral materials is the optical activity and circular dichroism, which enables the applications in asymmetric synthesis, sensing, separation, recognition, display, and information storage6,7,8,9,10,11. Chirality can be expressed at multiple levels from molecular, supramolecular to macroscopic scale; rational and precise manipulation of chirality is attractive yet remains a great challenge12,13,14. Bottom-up self-assembly is an effective protocol to realize chirality transfer, amplification and control, which allows for the periodic arrangement with specific screw sense15,16. It balances and connects the gap between molecular and macroscopic chirality, facilitating the construction of dynamic chiroptical materials17,18,19,20,21. To realize the dynamic chiral transformation and evolution, kinetic and thermodynamic protocols have been developed that flexible utilization of multiple components, additives, invasive or noninvasive stimuli, solvent media, and other external fields to modify and alter the chirality and chiroptical expression in a controllable manner22,23,24. Despite the above conventional protocols, developing alternative strategies in the synthesis of dynamic chiroptical materials shall advance the chiroptical applications, which, however, remain several challenges and difficulties25,26,27,28.

Topochemical reactions refer to the chemical reactions that occur in the crystalline state where the reactive sites are topologically packed29,30,31,32,33,34. The reactions are green, catalyst-free with high yields, such as alkyne-azide ‘click’ reaction and photo-triggered [2 + 2], [2 + 4] pericyclic reactions initiated by noninvasive heating or photo irradiation triggers35,36,37,38,39. These are widely employed in the targeted synthesis of polymers and the realization of single-crystal-to-single-crystal transitions40,41,42,43. The state-of-the-art topochemical systems are investigated in crystalline states and depending on the single-crystal structures, and consequently limit their applications in kinetically aggregated soft materials44,45. Compared to the long-range ordered crystalline matters, flexible self-assembled entities have less ordered molecular arrangement and more packing flaws, disfavoring the efficiency of topological chemical reactions46,47,48. In this regard, enhancing the noncovalent interaction and interplay between building units to give well-defined topological packing of reactive sites is a central factor49,50.

We intended to explore the applications of topochemical reactions in the synthesis of dynamic chiroptical materials. To overcome the less ordered packing in the kinetic aggregation process, charge-transfer (CT) interaction between aromatics was considered, as it provides alternative packing arrays to direct one-dimensional growth51,52,53,54. For topochemical reactions, we selected aryl diimide conjugated 1,4-dithiin with chiral pendants as CT electron acceptors (Fig. 1). X-ray structures illustrate the planar conformation of 1,4-dithiins directed by the four intramolecular S–O chalcogen bonds. The planar and electron-deficient nature allows for high binding affinity with anthracene to give CT complexes, which reacted via Diels–Alder (DA) reaction with ultrahigh efficiency, triggered by heating. It allows for alternation of π-conjugated structures that turn on the luminescence (quantum yields up to 57%). It enables the applications in thermal-triggered information storage and display, and the emergence of circularly polarized luminescence. In the self-assembled state, CT complexation enhances the one-dimensional packing as well as the chirality expression at the macroscopic scale, and heating arouses in situ DA reaction to light up the luminescence of helical fibers. The CT-DA cascade protocol shows great substrate applicability and was successfully employed in the topochemical synthesis of chiral luminescent macrocycles with advanced supramolecular chiral expressions. This work develops an advanced CT-DA protocol to synthesize a variety of chiroptical materials with high efficiency, and more intriguing applications are highly expected in the future.

Results

The diimide appended 1,4-dithiin compounds (1–4) conjugated with chiral pendants were synthesized facilely through several step condensation reactions (Fig. 2), which were fully characterized by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and high-resolution mass spectra (Supplementary Figs. 2–13). To evaluate the in situ DA addition reactions, compounds 1–4 were individually mixed with 1 molar equiv. of anthracene in solution that was heated at 80 °C. 1H NMR monitored the dynamic [2 + 4] DA addition reactions without side products (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Figs. 49, 50). The DA adduct yields, along with the incubation time determined by 1H NMR monitoring, suggest the reactions are completed at about 100 h (solution state). The final yields for DA1-DA4 are 96.2%, 85.5%, 93.5%, and 55.4%, respectively (Fig. 3B). The relatively low transition efficiency of DA4 might be caused by the relatively large steric effects of appended phenylalanine segments. We explored the photophysical property changes in the diluted state (0.5 mM) subjected to a higher incubation temperature (120 °C) to accelerate the reaction efficiency. Absorption and emission changes were recorded, showing gradual changes upon heating (Fig. 3C, D, Supplementary Figs. 51–54). Notably, the bathochromic shift in absorption to the visible region was along with the turn-on green luminescence, suggesting the occurrence of DA reaction with potentials in smart and switchable luminescent materials. The DA addition blocks the conjugated imide-dithiin structures with the formation of a typical D-π-A conjugate that turns on the luminescence. Frontier-orbital analysis provides physical insights into the supramolecular complexation and photophysical properties (Fig. 3E, Supplementary Figs. 55–58). The highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) diagrams show that the energy gap (Δ = 1.94 eV) between HOMO of anthracene and LUMO of 1,4-dithiin is much lower than the pristine gap (Δ = 3.57 eV) of anthracene, whereby the CT complexation is allowed to facilitate the subsequent DA reaction. The evidence could also be found in the electrostatic potential (ESP) maps of donor and acceptor (Fig. 3F, Supplementary Fig. 59). The electron-deficient core of diimide appended 1,4-dithiin planes is attractive to the electron-sufficient core of anthracene. Solid state diffusion reflectance spectra of CT acceptor 1 feature a prominent CT band at around 620 nm (Fig. 3G), which is caused by the intermolecular packing between electron-deficient and abundant parts. However, the CT could be strengthened by incorporating anthracene, a more electron-rich polyaromatic hydrocarbon55. After incorporation of anthracene, the CT band becomes wider and stronger, relatively, which is due to the anthracene/dithiin complexation. In contrast, the DA adduct comprises no apparent CT band. Lifetime (τ) and quantum yields (Φ) of DA adducts were measured in diluted solutions (Fig. 3H, Supplementary Figs. 63, 64). DA1, DA3, and DA4 have bright luminescence with Φ between 40% to 60%. Unexpectedly, DA2 has very limited Φ (1.2%) and short τ values. In DA2, the naphthalene performs as a strong electron-rich donor, which shall cause the electron transfer from the photoexcited luminophore through a typical photoinduced electron transfer (PET) route, thus accelerating the nonradiative transitions. The brightness of DA adducts is maintained at the solid state without an apparent quenching effect due to the nonplanar geometries. After casting on glass substrates (Fig. 3I, Supplementary Fig. 65), the blue emission of anthracene was totally quenched after CT complexation with 1 (also quenched in solution phase). Following one minute of gentle heating using a heating gun, green emission is observed. This interesting property enables the design of the smart display materials. Carbazole and anthracene with indistinct blue emission were mixed with the CT acceptor 1 in the polymer matrices. The quenched emission only in anthracene regions shall be rapidly recovered after being heated to show preset patterns. It illustrates the great potential in display and anti-counterfeit labels (Supplementary Fig. 66).

A Incubation time-dependent 1H NMR spectra of compound 1 (50 mM) in the presence of 1 molar equiv. anthracene in CDCl3 at 80 °C. B Yields of DA adducts as functions of incubation time at 80 °C determined by 1H NMR. C, D Heating time-dependent absorption and emission (λex = 410 nm) spectra of compound 1 (0.5 mM) in the presence of 1 molar equiv. anthracene in DMSO at 120 °C. E HOMO-LUMO energy levels and distributions of different entities. Geometry optimizations were performed at the B3LYP-D3/def2-TZVP level. F ESP maps of 1 and anthracene. G Solid state diffusion reflectance spectra comparison of 1, CT complex (1:1) and DA adduct with anthracene. H Lifetime (τ) and quantum yields (Φ) of each DA adduct. I Thin films in polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) on the glass substrates that show distinct emission under 365 nm illumination after CT and in situ DA addition reactions, which were utilized for smart display by heating.

To understand the CT-DA successive process from a structural perspective, single crystals were cultivated. Representatively, compound 1 features a planar geometry with a dihedral angle of about 180° (Fig. 4A, Supplementary Figs. 67–69). Most thianthrene and 1,4-dithiin derivatives adopt a bent geometry in most cases because planar topology results in antiaromaticity, which is energetically unfavorable unless there are steric constraints from larger substituents. In the present case, interestingly, in the absence of bulky steric effect, it still adopts the planar structure ascribed to the formation of intramolecular S–O bond (Fig. 4A). The S–O distance was around 3.1 Å, shorter than the sum of the van der Waals radii (3.5 Å). Meanwhile, the C-O-S angle was about 146°, in accordance with the σ-hole direction. The S–O locking should be the only mode, due to it is related to the occurrence of inherent CT interaction, which explains the dark green color of the electron acceptors in the solid state (Fig. 3G). Further evidence was provided by the noncovalent interaction (NCI) diagram, which visually demonstrates the formation of S–O chalcogen bond56. The interactions enable a conformational locking to afford a perfect planar geometry, which further facilitates the CT complexation. The S–O interaction has a profound influence on the planar geometry of 1,4-dithiin. The force, designated as the chalcogen bonding, is highly directional due to the orbital interplay between the anti-bonding orbital of the C-S σ-bond and the lone pair electron of oxygen. Other directions within the nonplanar geometry are unfavorable for the orbital interaction. The S–O interaction is thus locking the planar geometry, which further facilitates the CT complexation and size matching with anthracene. The bathochromic shift of absorption spectra (Fig. 3C) arises from the breaking of antiaromaticity. In a planar geometry of maleimide 1,4-dithiiin structure, the core shows antiaromaticity due to the number of 4n π electrons. Therefore, the S and maleimide are not fully conjugated, and after cycloaddition, the maleimide adopts the typical 4n + 2 aromaticity, causing a bathochromic shift of absorption. The corrected electronic energies imply a very high interaction energy of ΔEint = −94.52 kJ/mol (Fig. 4B, C, Supplementary Figs. 70–76). The reaction energy from the CT complex to the DA adduct is determined as −26.25 kJ/mol. The formation of stable CT complexes in the topological orientation increases the possibility of effective collision, thus elevating the reaction efficiency. X-ray structures of DA adducts were obtained (Fig. 4D), which all adopt an X shape. We notice the presence of multiple intramolecular noncovalent forces that lock the geometry. They contain the preserved S–O bonds, the emerged CH–π short contacts as well as the π–π stacking thanks to the bent aromatic planes of anthracene. These interactions could be found in the visual NCI diagram. Adaptive to the chiral pendants, the interactions are diversified, which influence the photophysical and chiroptical activities.

A X-ray structure of 1, its NCI diagram, as well as the X-ray structure of thianthrene. B Energy landscape of the CT complexation and DA addition reaction. C DFT optimized structure of the CT complex of 1 and anthracene. D X-ray structures of DA adducts. In the X-ray structure, C, H, O, S, and N atoms are color-coded as gray, white, red, yellow, and blue, respectively. Geometry optimizations were performed at the B3LYP-D3/def2-TZVP level and use indigo for C atoms.

Then we explored the evolution of chiroptical properties upon CT and DA processes. Due to the conformational locking, the shape-resistant geometry would facilitate the chirality transfer from chiral pendants to the aromatic luminophore core. Thereafter, the monomeric state in the solution exhibits active Cotton effects with moderate intensity (Fig. 5A, Supplementary Fig. 77). From 300 to 400 nm, they all exhibit exciton-type curves, indicating the strong coupling between the electronic transition dipole moment of benzene moieties with the 1,4-dithiin cores. The DA adducts in the solution state basically exhibit bathochromically shifted Cotton effects with distinct shapes (Fig. 5B, Supplementary Fig. 78), where chirality transfer still remains. After CT complexation with anthracene in the self-assembly state (dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO): H2O mixture), compared to the acceptors 1–4, the emergence of fingerprint-type circular dichroism (CD) peaks provide evidence for the strong CT complexation that generates multiple exciton couplings (Fig. 5C, D, Supplementary Figs. 79, 80). At the same time, we also evaluated the in situ DA reaction by recording gradual changes in CD spectra upon heating. To effectively represent the CD spectral transitions caused by reaction changes, a series of coassemblies (DMSO: H2O = 1:9) were prepared to characterize this process (Supplementary Figs. 81–85). In the self-assembly state, interestingly, the propensity of Cotton effects is almost identical to the solution state (Fig. 5B, E, Supplementary Fig. 86). It illustrates that the aggregation does not initiate supramolecular chirality to suppress the molecular chirality. The lack of directional force in the X-shaped DA adducts might result in the failed formation of one-dimensional chiral arrangements. Ascribed to the turn-on emission in the DA adducts, the circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) properties were evaluated both in the solution self-assemblies and polymer matrices (Fig. 5F, Supplementary Figs. 87, 88). DA1 to DA4 demonstrate green CPL emission at around 520 nm in the thin films of polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA). The dissymmetry glum ranges from 0.7 to 1.8 × 10−2, among the highest values in the self-assembled materials. A very interesting phenomenon is that either the chiroptical sign of acceptor 4 or DA4 with the same R or S absolute configuration is opposite to the others, in accordance with the CD sign inversion as well. The inversion is actually caused by the definition of the absolute configuration. Due to the numbering of COOMe being with high priority, the absolute chirality of DA4 is opposite to DA1-DA3, yet with the same relative chirality based on the orientation of aromatic moieties. It implies the vital role of the orientation of aryl groups in the chiral pendants in determining the supramolecular chiroptical properties.

A, B CD spectra of acceptors (0.5 mM) and DA adducts (1 mM) in solution (dichloroethane). C, D CD spectra of acceptors (1.67 mM) and CT complexes (0.83 mM, 1:1 by molar) in the self-assembly state (DMSO: H2O = 1:9 v/v). E CD spectra of DA adducts (1.67 mM) in the self-assembly state (DMSO: H2O = 1:9 v/v). F CPL spectra of DA adducts in the thin films of polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA).

After probing the properties of inherent building units, CT complexes, and DA adducts, we aimed to explore the thermal-triggered in situ transformation. It allows for the topochemical synthesis of DA products in the self-assembled state. Self-assembly was triggered by a typical solvent exchange protocol. Dispersing the building units into water generates the aggregates, depending on the chiral pendants, self-assembled into a variety of aggregates. Compounds 1–4 gave rise to nanoparticles and rods without the chiral expression at the nano/microscale. The formation of nanoparticles and rods reflects the insufficient directional force, such as hydrogen bonds or aromatic stacking, that failed to facilitate the one-dimensional growth for chiral expression. Representatively, compound 3 shows the merits of the in situ topochemical synthesis of chiroptical materials (Fig. 6A, Supplementary Figs. 89–106). After CT complexation, the achiral nanorods from inherent 3 transform into M-handed helices with apparently extended one-dimensional growth. The growth of one-dimensional architectures with helical bias requires directional force, such as well-defined π-stacking or hydrogen bonding. CT complexation with anthracene, as evidenced by the diffusion reflectance spectra and DFT optimization, introduced strong aromatic packing with alternative packed arrays, which greatly facilitates the one-dimensional growth. In situ heating of the self-assembled CT complexes in solution resulted in the formation of bright green luminescent materials, verified by the occurrence of DA reactions (1H NMR spectra registered in CDCl3 indicated a near unity transformation efficiency, Supplementary Figs. 107–114). It maintains the M-handed helical sense, also showing the enantiomeric effect that the opposite S-configuration affords P-handed correspondingly. In contrast, direct self-assembly of pure DA adducts shall generate crystalline or nanoparticles without the expression of chirality at the macroscopic scale. Further evidences were collected to unveil the transformation behaviors at the molecular level. X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern comparison illustrates that the CT complexation comprises two sets of inherent patterns (Fig. 6B, Supplementary Fig. 115), which are assigned as the newly formed DA band and shifted CT bands. Direct heating of the CT complexes arouses slight shifts of the peaks, with emerged small new peaks that are assigned as the independent self-assembled DA adducts. The mixture might be caused by the block-co-assembly with partial narcissistic sorting within the complexation, where the partial DA adducts adapted the packing in the solid state. Most of the CT complexes would transform into DA adducts in the self-assembled state, exhibiting the typical topological transitions. Under microspectrometer observation, the heated CT complexes exhibited bright green emission with a consistent microscale emission spectrum with the pure DA adducts (Fig. 6C, Supplementary Figs. 120, 121), which strongly verified the in situ topological transformation to DA products in the assembly state. Structural insights into the packing diversity were provided by the single-crystal profiles. In the packing modality, the donor would not prefer intermolecular chalcogen bonding due to the σ-holes being occupied by the carboxyl group intramolecularly (Fig. 6D). No π–π stacking but S–S short contacts were found with a distance of 3.578 Å, which is probably classified into the van der Waals. It is also found that benzene segments as electron donors form intermolecular CT complexation (D = 3.507 Å) with 1,4-dithiins (Fig. 6E), in good agreement with the reflectance spectra in Fig. 3G, which reflects strong CT binding affinity of the 1,4-dithiin groups. Packing mode of DA adducts (Fig. 6F) is expectedly to adopt no strong and directional forces due to the nonplanar topology and lack of polar functional groups. Hirshfeld surface analysis (Fig. 6G, Supplementary Figs. 122, 123) on the single-crystal profile of 1 and DA1 shows high fractions of H-H and other van der Waals forces with less directional interactions, illustrating the poor capability in generating chiroptical helical structures compared to the CT complexes.

A Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of R3 (1.67 mM), R3/anthracene complex (0.83 mM, 1:1 by molar) before and after heating, and the pure DAR3 (1.67 mM) in the self-assembled state (DMSO: H2O = 1:9 v/v). B The corresponding XRD patterns of different species in the self-assembled state. C Emission spectra collected by the microspectrometer of the heated CT complex (S3/anthracene 1:1, 0.83 mM); inset is the sample image at the excitation wavelength of 420 nm. D, E Stacking modes of 1 with different interactions; F Stacking structures of DA1 found in the X-ray structure. G Hirshfeld surface diagrams of H-H short contacts and the portion changes of 1 and DA1 found in the X-ray structure. Atoms are colored gray (C), white (H), red (O), yellow (S), and blue (N) in X-ray structures.

Rational utilization of the CT-DA cascade reaction protocol enables the synthesis of chiral macrocycles. As a proof-of-concept, we synthesized three crown ethers embedded with anthracene at the 9,10-position (5O, 6O, 7O, Fig. 7A). Due to the presence of macrocyclic substituents with enlarged steric effects, DA reactions were initially conducted in solutions. And the successful synthesis of several macrocyclic DA adducts illustrates great potential of this protocol in constructing functional supramolecules (Supplementary Figs. 124–129). It expresses good structural extensibility to substrates, and the resultant products have customized absolute chirality and high quantum yields, which potentially can be used in chiroptical sensing applications. We also cultivated the single crystal of the macrocycle (DAS3-5O), which adopts a three-dimensional extended molecular topology. In the solution phase, the monomeric state exhibits very similar chiroptical activities with the pristine skeletons without crown ether pendants (Fig. 7B, Supplementary Figs. 130–133). It reflects the shape-resistance of the DA adduct skeleton that the conjugation of macrocycles would hardly alter the pristine chiral conformation and photophysical properties. In the aggregation state, the macrocyclic DA adducts possess distinct chiroptical behaviors in contrast to the pristine DA adducts. Reasonably, the appended crown ethers introduce significant steric effects with closure chains, which further enhance the conformation resistance. It favors boosting the chiroptical dissymmetry factors of CPL, whereby DA1-5O affords glum = ±0.02 in PMMA thin films. We also examined the potential in the topochemical synthesis of macrocycle-based chiroptical helical structures. After self-assembly, the 5O-7O and DA macrocycles all possess the propensity to give three-dimensional spheres or microcrystals without one-dimensional extension (Fig. 7C, Supplementary Figs. 134–145) on account of the insufficient directional forces. CT complexation, disregarding the steric effects of macrocycles, induces the formation of long and flexible helices with P-handedness, and the topology was maintained after heating to initiate the DA addition reaction. Such topochemical synthesis would well maintain the permanent porosity (Fig. 7D) while adopting a helical sense with controllable chiroptical properties.

A Chemical structures of anthracene-embedded macrocycles and the synthesized DA chiral macrocycles. B CD spectra of DA adducts in the solution (1 mM in dichloroethane) and assembly (1.67 mM, DMSO/H2O, 1/9) state, and CPL spectra (λex = 410 nm) of DA adducts in the thin films of polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA). C SEM images of self-assembled 5O (1.67 mM), its CT complexes with S3 (0.83 mM, 1:1 by molar), heated CT complexes, and DA adducts (1.67 mM) in DMSO/H2O mixture (1/9, v/v). D Packing of DA3-5O in the X-ray structure. E Emission spectra comparison of the different self-assemblies. Self-assembly protocols were identical to the SEM samples.

Discussion

In conclusion, we report the utilization of the cascade CT-DA reaction protocol to synthesize dynamically transformable chiroptical materials. Aromatic amide appended 1,4-dithiin conjugated with chiral pendants was designed and synthesized. The chiral compounds behave as effective electron acceptors to anthracene. CT complexation introduces directional noncovalent forces to induce the formation of one-dimensional helical nanoarchitectures. Thermal stimulus triggers a DA addition reaction to alter the π-conjugated aromatic structure to turn on the luminescence, with the applications in smart display and information storage. DA reaction promotes the emergence of CPL with a high dissymmetry g-factor at 10−2 grade. The CT-DA cascade protocol shows broad substrate applicability, whereby the macrocycles embedded with DA adduct segments were readily constructed, with potential in chiroptical sensing and self-assembled soft materials. The protocol greatly extends the type, application of topochemical reactions, especially in the synthesis of chiral matter.

Methods

Materials

All commercial chemicals were used as received. The synthesis procedures for acceptors and Diels–Alder (DA) adducts are described in Supplementary Fig. 1, while those for macrocycles are detailed in Supplementary Figs. 26 and 27.

Self-assembly protocol

The compounds were first dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide via ultrasonic treatment to prepare stock solutions (16.7 mM). For self-assembly formation, a specific volume of stock solution (100 μL) was injected into bulk deionized (DI) water (900 μL). After aging at ambient temperature for 8 h, the final system (1.67 mM) with a fixed DMSO/water volume ratio of 1:9 was obtained for subsequent characterization. A PMMA stock solution (0.1 g/mL in THF) was prepared, to which 0.05 mM DA product was added. This mixture (1 mL) was blade-coated onto quartz substrates (12 × 45 × 1 mm³) and air-dried under ambient conditions.

Co-assembly protocol

Chiral electron acceptor and electron donor solutions (50 μL each) were combined in vials, followed by the addition of 900 μL deionized water to form co-assembly solutions (total volume 1 mL). For comparative studies, control samples with varying concentrations maintained a fixed DMSO/water volume ratio of 1:9. Unless otherwise specified, all tested samples adopted the S-configuration. For co-assembled composites, anthracene and chiral acceptors were co-dissolved in the PMMA/THF solution for film casting.

Measurement of NMR and High-resolution mass spectra

1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker ADVANCE III 400 and 500 (1H: 400 MHz and 500 MHz, 13C: 100 MHz) spectrometer in DMSO-d6 or chloroform-d at 298 K. High-resolution mass spectra (HR-MS) were performed on an Agilent Q-TOF 6510.

Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements

Powder XRD patterns were collected on a PANalytical (X’Pert3 Powder&XRK-900). X-ray diffraction with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.15406 nm, voltage 45 KV, current 200 mA, power 9 KW). The samples were cast onto cover glasses (20 mm × 20 mm) and dried to form thin films.

Scanning electron microscope characterizations

SEM images were measured by a Zeiss scanning electron microscope (Germany). The samples for SEM detection were dropped on a single-crystal silicon wafer, dried, and then sprayed with gold to increase the contrast before detection.

Fluorescence microscope image

Micro-area fluorescence variations and fluorescence morphologies were measured with a 20/30 PVTM UV-Visible-NIR Microspectrophotometer. Charge-transfer complex was spin-coated onto a glass slide, and fluorescence changes in the micro-area were observed under a microscope.

Fourier transform infrared spectra

FT-IR spectra were recorded on a Tensor II FT-IR spectrometer. All samples were dried and further dispersed in a KBr pellet and submitted for FT-IR spectra measurement.

UV-Visible absorption spectra

UV-Visible absorption spectra were recorded at room temperature using a Shimadzu UV-1900 spectrophotometer. Absorption measurements were performed in a 10 mm quartz cuvette. Reflectance measurements were carried out with an Agilent Cary 5000 UV-Vis-NIR spectrophotometer equipped with an integrating sphere, using barium sulfate (BaSO4) as the reference standard.

Fluorescence spectra

The fluorescence spectra were recorded on an RF 6000 Shimadzu fluorophotometer. Fluorescence lifetime and quantum yield (QY) were measured by Steady State-Transient-Fluorescence Spectrometer (Edinburgh FLS920). 1 mM solution of DA1-4 dissolved in 1,2-dichloroethane was used for testing, with an excitation wavelength of 410 nm in a 10 mm cuvette.

Circular dichroism spectra and Circularly polarized luminescence spectra

CD and CPL were measured with an Applied Photophysics ChirascanV100 model. The sample was prepared by transferring a droplet of suspension into a quartz cuvette with a light path of 0.1 mm. The linear birefringence effects and possible artifacts caused by macroscopic anisotropy were generally excluded by flipping and changing the angle of the sample along the direction of incident light propagation. DA1 to DA4 demonstrate green CPL emission at around 520 nm in the thin films of PMMA. The in situ heating thin-film-like samples were fabricated by casting onto cover glasses (20 mm × 20 mm) and drying under controlled conditions. To induce the Diels–Alder reaction, in situ heating was applied directly to the glass substrates until the system became optically stable (∼10 min, monitored via color consistency). Subsequently, the thermally processed samples were cooled to room temperature to reach equilibrium prior to further characterization. Chiral optical testing is performed using quartz glass.

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements

Single crystal was collected on Rigaku Oxford Diffraction XtaLAB Synergy diffractometer equipped with a HyPix-6000HE area detector (Japan), using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54184 Å) from a Photon Jet micro-focus X-ray source. The structures were solved by direct methods and refined by a full matrix least squares technique based on F2 using the SHELXL 97 program (Sheldrick, 1997). The crystal packing was obtained using the software Mercury. Crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were obtained in methanol or dichloromethane solution by a slow evaporation method.

Density functional theory (DFT) computation

The absolute configuration of chiral electron acceptors and Diels–Alder (DA) adducts was extracted from X-ray crystal structures. Other similar structural analogs were obtained by simple modifications. All molecular geometries were optimized using Gaussian 16 software with density functional theory (DFT) calculations at the B3LYP-D3/def2-TZVP level. Noncovalent interaction (NCI) analyses were then performed on the optimized structures using Multiwfn. Cartesian coordinates of the optimized structures are provided in the Source Data.

Data availability

All relevant data generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author. Supplementary Information is available in the online version of the paper. Source Data are provided with this manuscript. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, under deposition numbers 2388504-2388508. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Noyori, R. Century lecture: chemical multiplication of chirality: science and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 18, 187–208 (1989).

Engel, K. Chirality: an important phenomenon regarding biosynthesis, perception, and authenticity of flavor compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 68, 10265–10274 (2020).

Barron, L. D. Chirality and life. Space Sci. Rev. 135, 187–201 (2008).

Liu, M., Zhang, L. & Wang, T. Supramolecular chirality in self-assembled systems. Chem. Rev. 115, 7304–7397 (2015).

Yashima, E. et al. Supramolecular helical systems: helical assemblies of small molecules, foldamers, and polymers with chiral amplification and their functions. Chem. Rev. 116, 13752–13990 (2016).

Jiang, J., Meng, Y., Zhang, L. & Liu, M. Self-assembled single-walled metal-helical nanotube (M-HN): creation of efficient supramolecular catalysts for asymmetric reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 15629–15635 (2016).

Sripada, A., Thanzeel, F. Y. & Wolf, C. Unified sensing of the concentration and enantiomeric composition of chiral compounds with an achiral probe. Chem 8, 1734–1749 (2022).

Hirose, D., Isobe, A., Quiñoá, E., Freire, F. & Maeda, K. Three-state switchable chiral stationary phase based on helicity control of an optically active poly(phenylacetylene) derivative by using metal cations in the solid state. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 8592–8598 (2019).

Peluso, P. & Chankvetadze, B. Recognition in the domain of molecular chirality: from noncovalent interactions to separation of enantiomers. Chem. Rev. 122, 13235–13400 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Achiral dichroic dyes-mediated circularly polarized emission regulated by orientational order parameter through cholesteric liquid crystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202312159 (2023).

Chen, X. M. et al. Light-activated photodeformable supramolecular dissipative self-assemblies. Nat. Commun. 13, 3216 (2022).

Sahoo, J. K., Pappas, C. G., Sasselli, I. R., Abul-Haija, Y. M. & Ulijn, R. V. Biocatalytic self-assembly cascades. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 6828–6832 (2017).

Guo, Y. Q. et al. Simultaneous chiral fixation and chiral regulation endowed by dynamic covalent bonds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202312259 (2023).

Kumar, P. et al. Photonically active bowtie nanoassemblies with chirality continuum. Nature 615, 418–424 (2023).

Wu, A. et al. Tunable chirality of self-assembled dipeptides mediated by bipyridine derivative. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202314368 (2023).

Zhang, Q., Toyoda, R., Pfeifer, L. & Feringa, B. L. Architecture-controllable single-crystal helical self-assembly of small-molecule disulfides with dynamic chirality. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 6976–6985 (2023).

Rahman Md, W. et al. Chirality-induced spin selectivity in heterochiral short-peptide-carbon-nanotube hybrid networks: role of supramolecular chirality. ACS Nano 16, 16941–16953 (2022).

Sarkar, S., Laishram, R., Deb, D. & George, S. J. Controlled noncovalent synthesis of secondary supramolecular polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 22009–22018 (2023).

Huang, Z., He, Z., Ding, B., Tian, H. & Ma, X. Photoprogrammable circularly polarized phosphorescence switching of chiral helical polyacetylene thin films. Nat. Commun. 13, 7841 (2022).

Kumar, J., Nakashima, T. & Kawai, T. Circularly polarized luminescence in chiral molecules and supramolecular assemblies. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 3445–3452 (2015).

Wang, F., Shen, C., Gan, F., Zhang, G. & Qiu, H. Tunable multicolor circularly polarized luminescence via co-assembly of one chiral electron acceptor with various donors. CCS Chem. 5, 1592–1601 (2023).

Hema, K. et al. Topochemical polymerizations for the solid-state synthesis of organic polymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 4062–4099 (2021).

Imai, Y. Circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) induced by an external magnetic field: magnetic CPL (MCPL). ChemPhotoChem 5, 969–973 (2021).

Wang, Z., Xie, X., Hao, A. & Xing, P. Multiple-state control over supramolecular chirality through dynamic chemistry mediated molecular engineering. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202407182 (2024).

Zhang, L., Wang, H.-X., Li, S. & Liu, M. Supramolecular chiroptical switches. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 9095–9120 (2020).

Yue, B. et al. In situ regulation of microphase separation-recognized circularly polarized luminescence via photoexcitation-induced molecular aggregation. ACS Nano 16, 16201–16210 (2022).

Bloom, B. P., Paltiel, Y., Naaman, R. & Waldeck, D. H. Chiral induced spin selectivity. Chem. Rev. 124, 1950–1991 (2024).

Hu, R., Lu, X., Hao, X. & Qin, W. An organic chiroptical detector favoring circularly polarized light detection from near-infrared to ultraviolet and magnetic-field-amplifying dissymmetry in detectivity. Adv. Mater. 35, 2211935 (2023).

Biradha, K. & Santra, R. Crystal engineering of topochemical solid state reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 950–967 (2013).

Khorasani, S. & Fernandes, M. A. A synthetic co-crystal prepared by cooperative single-crystal-to-single-crystal solid-state Diels–Alder reaction. Chem. Commun. 53, 4969–4972 (2017).

Wang, M., Jin, Y., Zhang, W. & Zhao, Y. Single-crystal polymers (SCPs): from 1D to 3D architectures. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 8165–8193 (2023).

Hema, K., Ravi, A., Raju, C. & Sureshan, K. M. Polymers with advanced structural and supramolecular features synthesized through topochemical polymerization. Chem. Sci. 12, 5361–5380 (2021).

Lauher, J. W., Fowler, F. W. & Goroff, N. S. Single-crystal-to-single-crystal Topochemical Polymerizations by Design. Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 1215–1229 (2008).

Morimoto, K. et al. Edge-to-center propagation of photochemical reaction during single-crystal-to-single-crystal photomechanical transformation of 2,5-distyrylpyrazine crystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202212290 (2022).

Khazeber, R. & Sureshan, K. M. Single-crystal-to-single-crystal translation of a helical supramolecular polymer to a helical covalent polymer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA119, e2205320119 (2022).

Cao, C. et al. Photodimerization-triggered photopolymerization of triene coordination polymers enables macroscopic photomechanical movements. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 25028–25034 (2024).

Guo, Q.-H. et al. Single-crystal polycationic polymers obtained by single-crystal-to-single-crystal photopolymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 6180–6187 (2020).

Liu, Y., Guan, X.-R., Wang, D.-C., Stoddart, J. F. & Guo, Q.-H. Soluble and processable single-crystalline cationic polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 13223–13231 (2023).

Dou, L. et al. Single-crystal linear polymers through visible-triggered topochemical quantitative polymerization. Science 343, 272–277 (2014).

Jiang, X. et al. Topochemical synthesis of single-crystalline hydrogen-bonded cross-linked organic frameworks and their guest-induced elastic expansion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 10915–10923 (2019).

Anderson, C. L. et al. Solution-processable and functionalizable ultra-high molecular weight polymers via topochemical synthesis. Nat. Commun. 12, 6818 (2021).

Wei, Z. et al. Side-chain control of topochemical polymer single crystals with tunable elastic modulus. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 25, e202213840 (2022).

Kissel, P. et al. A two-dimensional polymer prepared by organic synthesis. Nat. Chem. 4, 287 (2012).

Kim, J., Hubig, S., Lindeman, S. & Kochi, J. Diels-Alder topochemistry via charge-transfer crystals: novel (thermal) single-crystal-to-single-crystal transformations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 87–95 (2001).

Krishnan, B. P. & Sureshan, K. M. Topochemical azide-alkyne cycloaddition reaction in gels: size-tunable synthesis of triazole-linked polypeptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 1584–1589 (2017).

Ouyang, G., Ji, L., Jiang, Y., Würthner, F. & Liu, M. Self-assembled möbius strips with controlled helicity. Nat. Commun. 11, 5910 (2020).

Maurya, G. P., Verma, D., Sinha, A., Brunsveld, L. & Haridas, V. Hydrophobicity directed chiral self-assembly and aggregation-induced emission: diacetylene-cored pseudopeptide chiral dopants. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202209806 (2022).

Qin, L., Gu, W., Wei, J. & Yu, Y. Piecewise phototuning of self-organized helical superstructures. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704941 (2018).

Meng, X. et al. Building a cocrystal by using supramolecular synthons for pressure-accelerated heteromolecular azide-alkyne cycloaddition. Chem. Eur. J. 25, 7142–7148 (2019).

Nguyen, T. L., Fowler, F. W. & Lauher, J. W. Commensurate and incommensurate hydrogen bonds. an exercise in crystal engineering. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 11057–11064 (2001).

Botes, D. S., Khorasani, S., Duminy, W., Levendis, D. C. & Fernandes, M. A. Supramolecular Inhibition of [4 + 2] Diels-Alder reactions in charge-transfer crystals. Cryst. Growth Des. 20, 291–299 (2020).

Yun, J. Y., Koo, J. J., Lee, D. K. & Kim, J. H. Quantitative regio-selective Diels–Alder reaction of an unsymmetrical 1,4-dithiin and anthracene through heterogeneous solid state conversion. Dyes Pigm 83, 262–265 (2009).

Han, J. et al. Enhanced circularly polarized luminescence in emissive charge-transfer complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 7013–7019 (2019).

Emenike, B. U., Shinn, D. W., Spinelle, R. A., Yoo, B. & Rosario, A. M. Quantifying macrocyclization-induced strain utilizing N-phenylimides as conformational reporters. Chem. Commun. 60, 4040–4043 (2024).

Pandeeswar, M., Khare, H., Ramakumar, S. & Govindaraju, T. Biomimetic molecular organization of naphthalene diimide in the solid state: tunable (chiro-) optical, viscoelastic and nanoscale properties. RSC Adv. 4, 20154–20163 (2014).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22171165, 22371170).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.W. and Y.P. contributed equally to this work. Z.W. and P.X. conceived the project. Z.W. performed the morphology characterization and DFT modeling. Y.P. synthesized the compounds and tested the corresponding spectra. Z.W. and Y.P. collaborate on fluorescent displays and related tests. A.H. and P.X. supervised and directed this work. P.X. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Qing-Hui Guo and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Pei, Y., Hao, A. et al. Topochemical synthesis of chiroptical materials through charge-transfer/Diels–Alder cascade reaction. Nat Commun 16, 5539 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60790-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60790-6