Abstract

Solid-state sodium metal batteries have attracted great interest because of their improved safety and abundant Na resources. However, the interfacial resistances and instabilities induced by parasitic reactions, together with Na dendrite issues, result in reduced rate capability and poor cycling stability. Here, we address these challenges by intrinsically inhibiting parasitic interfacial redox reactions through enhanced P-O covalency in Na3Zr2Si2PO12 (NZSP) with Na2SiF6 incorporation, wherein the high electronegativity of F strengthens P-O covalency. Additionally, SnF2 coating provides a sodiophilic surface and stabilizes the NZSP interface, which is essential for effective electrochemical cycling. This integrated approach significantly reduces interfacial impedance to 2.0 Ω cm2, enabling stable Na plating/stripping for 3600 hours at 0.5 mA cm-2/0.25 mAh cm-2. The full cell with Na3V2(PO4)3 positive electrode demonstrates stable cycling with high-rate capability (87.5% capacity retention after 2500 cycles at 1 C and 96.1% capacity retention after 1200 cycles at 5 C). This study sheds light on the development of high-performance quasi-solid-state sodium batteries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sodium-ion batteries are regarded as a promising candidate for next-generation energy storage systems due to the abundance of Na resources1. However, the current sodium-ion batteries based on liquid electrolytes have the critical safety issue due to the use of flammable liquid electrolytes, which urgently requires the development of solid-state sodium metal batteries (SSBs) with a high safety2,3,4,5,6. Solid-state electrolytes (SSEs) are the core component of SSBs. Na3Zr2Si2PO12 (NZSP) oxide electrolytes have garnered significant interest due to their three-dimensional ion transport framework and facile synthesis7,8,9,10. While the application of NZSP is promising, it is currently restricted by two main factors: low ionic conductivity and high interfacial impedance in contact with metallic Na11. To date, researchers have been able to significantly enhance the ionic conductivity of SSEs by ion doping12,13,14. Furthermore, the interfacial contact between the Na negative electrode and SSEs was effectively mitigated by the interfacial modification techniques, including interfacial coating and the formation of molten metal alloys15,16,17,18. The interfacial modification techniques in question can effectively enhance the contact between the Na negative electrode and SSEs, thereby reducing the interfacial impedance19. Unfortunately, despite the aforementioned improvements, the cells still experience Na dendrites puncturing the SSEs over extended periods of cycling or at higher current densities, which can ultimately lead to cell failure. This phenomenon may be largely attributed to the fact that NZSP reacts with Na and thus destroys the NZSP structure under prolonged cycling or high current density.

Nevertheless, a substantial number of researchers concur that the NZSP structure is relatively stable20,21,22. According to the frontier molecular orbital theory, metal Na and NZSP undergo spontaneous electrochemical reactions due to the formation of interphase layers between them as a result of the difference in chemical potentials23. The interphase layer, formed through the process of ion and electron transport, plays a pivotal role in the stability of NZSP SSEs and the metal Na24. Wang et al. 25. demonstrated that a SSEs in contact with the negative electrode forms a mixed ion-electron conducting interphases capable of transporting both electrons and ions, which results in a continuous SSEs decomposition. Moreover, the ionic and electronic conductivity of the interphase determines the growth rate of the interphase thickness and the resulting interfacial resistance. High electronic and low ionic conductivity may lead to the occurrence of rapid parasitic degradation of SSEs26. In addition, Manthiram et al. 27 found that the ideal stabilizing interphase layer matter has a high ionic conductivity and a low electronic conductivity, which can effectively stabilize the Na and NZSP interface, and prevent Na from further parasitic reaction with NZSP. The metal Na electrochemically reacts with the NZSP to form interfacial parasitic products in the form of the mixed ion-electron conducting interphases28. This uncontrollable interphase layer leads to the continuous decomposition of the NZSP, which promotes the growth of Na dendrites on the surface and inside of the SSEs, thus deteriorating the performance of the cell29. Therefore, it is of utmost importance to develop and design an NZSP structure that inhibits the corrosive effects of metallic Na, thereby modulating the ionic and electronic nature of the interfacial phases formed.

Based on calculations and experiments, it was determined that an interfacial parasitic reaction between Na and NZSP may originate from the spontaneous and irreversible redox reaction between PO4/SiO4 tetrahedra in the structure of NZSP and metallic Na30. This reaction results in the gradual destruction and decomposition of NZSP. This PO4/SiO4 tetrahedron is composed of P-O/Si-O covalent bonds, which are susceptible to attack by electron-rich Na atoms, which in turn diminishes the weakened bond energy of the P-O/Si-O bonds31. This, in turn leads to the formation of parasitic products of phosphates/silicates with low ionic conductivity and ZrSi with high electronic conductivity, resulting in successive parasitic reactions and consequent destruction of NZSP32. Therefore, we speculate that enhancing the stability of the NZSP interface may depend on the inhibition of the redox activity of the PO4/SiO4 tetrahedra to tune the electronic and ionic nature of the products generated from the interfacial phase, which in turn stabilizes the structure of NZSP. However, the construction of stable NZSP to regulate the interfacial phase between NZSP and Na has been little studied, which remains a critical challenge.

In this work, we successfully inhibit the interfacial redox between PO4/SiO4 tetrahedra and metal Na through two complementary approaches: enhancing P-O covalency in NZSP with the incorporation of Na2SiF6 (NSF) and applying SnF2 coating to create a stable interface, thus achieving a high-rate capability and stability quasi-SSB. The NSF was introduced into the NZSP structure to form NZSP-NSF SSEs, which allows the doping of F in PO4/SiO4 tetrahedra to construct a stable structure and effectively inhibit the irreversible redox decomposition of NZSP. Moreover, the introduction of extra Si can effectively increase the Si/P ratio in NZSP, which in turn increases the ionic conductivity of the SSEs. Separately, the SnF2 coating provides a sodium-philic interface and stabilizes the electrode-electrolyte interface, suppressing side reactions during cycling. The synergistic effect of NZSP-NSF bulk modification and SnF2 surface coating facilitates the generation of denser NaF intercalation at the interface, thereby inhibiting the nucleation and growth of Na dendrites and enabling long cycling at high current densities. The interfacial impedance is only 2.0 Ω cm2, and the assembled symmetric cells show a stable plating/stripping of Na (6000 h at 0.2 mA cm−2 and 3600 h at 0.5 mAh cm−2), which are much longer than that of the pure NZSP (100 h). The quasi-solid-state full cell with the Na2SiF6 doped NZSP-NSF SSEs and with Na3V2(PO4)3 (NVP) positive electrode show a high capacity retention of 87.5% after a long-term 2500 cycle at 1 C. Even at a high specific current of 5 C it still delivers a discharge-specific capacity of 100.11 mAh/g and keeps a very high retention of 96.1% after 1200 cycles. This study offers an effective strategy to address the interfacial issues in terms of parasitic redox, large interfacial impedance, and Na dendrites through both enhancing P-O covalency within the electrolyte and stabilizing the interface with SnF2 coating, which work synergistically to advance the development of high-performance quasi-solid-state sodium batteries.

Results and discussion

Properties and characterization of solid electrolytes

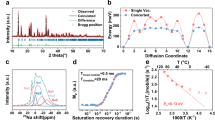

As previously reported, the facile high-temperature solid phase method was used to synthesize NZSP-xNSF (x = 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0 wt%). The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns demonstrate that NZSP-xNSF has the same monoclinic phase (C2/c space group) as pure NZSP (PDF#01-070-0234). It is further found that with the increase in the amount of Na2SiF6, no increase in the amount of nonconducting ions of ZrO2 is observed33 (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Figs. 1–2). This means doping a small amount of Na2SiF6 does not cause a large change in the crystal structure. In addition, the transport of Na+ ions in NZSP SSEs necessitates the overcoming of the bottleneck region in Na1-Na2, which is responsible for the migration of Na+ ions. The size of the bottleneck is directly correlated with the magnitude of the migration energy barrier, which in turn influences the conductivity of Na+ ions. Consequently, XRD refinement of NZSP-xNSF was conducted to determine the position of each atom and calculate the size of the bottleneck (T1) in the Na+ ions conduction pathway7. Following the XRD refinement of NZSP-xNSF with varying doping concentrations, a notable decline in cell volume was observed with the elevation of Na2SiF6 doping (Supplementary Fig. 3a and Supplementary Tables 1–6). This phenomenon can be attributed to the substitution of F doping in the position of O in the SiO4/PO4 tetrahedron, where the ionic radius of F is significantly smaller than that of O, consequently reducing the overall cell volume of NZSP-xNSF. Therefore, scanning electron microscope (SEM) analysis reveal that the particles of the NZSP-xNSF samples exhibit a higher packing density and fewer pores in comparison to the pure NZSP (Supplementary Fig. 4). Moreover, since XRD is not sensitive to the element F, neutron diffraction, which is more sensitive to the element F, was employed to test NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF34 (Fig. 1b, c). The fitting of these parameters confirms that both NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF belong to the C2/c space group crystal structure (Fig. 1d, e). The sites of F doping into the O site of PO4/SiO4 can be determined by refining the occupancy of NZSP-0.6NSF (Supplementary Tables 7–8). Meanwhile, the NZSP-0.6NSF exhibits lattice shrinkage (a = 15.65296 Å, b = 9.05466 Å, c = 9.21783 Å, V = 1086.485 Å3) compared to the NZSP structure (a = 15.65415 Å, b = 9.05502 Å, c = 9.21993 Å, V = 1086.678 Å3). This is because F− occupies the O position of PO4/SiO4 in NZSP35, and its smaller radius causes lattice contraction compared to O2−. Therefore, it was determined that doping with Na2SiF6 indeed results in a reduction in the cell volume of the SSEs (Supplementary Fig. 5a).

a The XRD patterns of Na3Zr2Si2PO12-xwt%Na2SiF6 (x = 0,0.2,0.4,0.6,0.8,1.0) and enlarged diagram of the two characteristic peaks. b, c The NPD patterns and the corresponding Rietveld refinement results of NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF. d, e Schematic of crystal structures of NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF after NPD Rietveld refinement (the orange balls represent Na atoms, green balls represent Zr atoms, blue and purple balls represent Si and P atoms, respectively, yellow balls represent O atoms, and red balls represent F atoms). f, g The XPS fine spectra at P 2p and Si 2p for NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF. h, i The Solid-state MAS NMR of 31P and 29Si of NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF. j The SEM image of the NZSP-0.6NSF and corresponding EDS elemental mappings of Na, Zr, Si, P, and F.

Despite the reduction in unit cell volume observed in NZSP-xNSF upon doping with Na2SiF6, the size of the Na+ ion diffusion bottleneck T1 exhibits a distinct pattern (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Surprisingly, the T1 of NZSP-xNSF (x = 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6) doped with a modest quantity of Na₂SiF₆ exhibits an increase in value with rising doping levels. In contrast, the T1 of NZSP-xNSF (x = 0.8, 1.0) doped with excessive quantities of Na2SiF6 exhibits a decline. Therefore, the Na+ diffusion bottleneck T1 of NZSP-0.6NSF is considerably larger than that of NZSP-xNSF with other doping amounts. This fully explains that a small amount of doped Na2SiF6 will be able to enhance the mobility of Na+ ions due to the enhancement of the additional Si content, without restricting the transport of its Na+ ions due to the decrease of the unit cell volume. However, excessive doping of Na₂SiF₆ results in the obstruction of Na+ ion diffusion due to a reduction in the overall unit cell volume. Furthermore, the same conclusion was reached through neutron refinement, which demonstrated that the T1 diffusion bottleneck of NZSP-0.6NSF was significantly larger than that of NZSP (Supplementary Fig. 5b). These findings indicate that NZSP-0.6NSF exhibits a leading ionic conductivity, as the moderate doping of Na2SiF6 can effectively enlarge the diffusion bottleneck of Na+ ions. Furthermore, the bond lengths of the P-O bonds have been corroborated through XRD and neutron refinement of NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF (Supplementary Fig. 6). It can be demonstrated that the bond length of the P-O bond in NZSP-0.6NSF is markedly shorter than that of NZSP. This indicates that the doping of Na2SiF6 results in the doping of F into the position of O in the PO4 tetrahedra, which in turn causes the bond length of the P-O bond to shorten and the covalency of the P-O bond to increase.

Furthermore, the Na+ conductivity of NZSP-xNSF was tested using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) at 25 °C (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Among the tested samples, the moderately NZSP-0.6NSF exhibits a leading ionic conductivity at 1.3 × 10−3 S cm−1 (Supplementary Fig. 8). This result is consistent with the XRD refinement to obtain the Na+ ion diffusion bottleneck area T1. This is because excessive doping can cause severe contraction of the crystal structure, which can block the channels for diffusion of Na+ 13. In addition, the elemental compositions of NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF were determined using inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) to determine their Si/P variations. Unsurprisingly, the compositional contents of NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF are similar, with the only difference being the Si/P ratio content (Supplementary Table 9). The Si/P ratio content of NZSP-0.6NSF is larger than that of NZSP due to the doping of Na2SiF6. Therefore, the addition of Na2SiF6 is demonstrated to be effective in elevating the Si/P ratio, thereby enhancing the ionic conductivity of NZSP-0.6NSF36. In addition, the conductivity of NZSP-xNSF was tested in the range of 25–100 °C (Supplementary Fig. 9). The conductivity of NZSP-xNSF increases with temperature. Moreover, the activation energy (Ea) of various NZSP-xNSFs was evaluated using the Arrhenius equation: σ = A/T (exp(−Ea/kT)), where A is the pre-factor, and k is the Boltzmann constant. The NZSP-0.6NSF (0.33 eV) exhibits a lower activation energy in comparison to other SSEs (Supplementary Fig. 7b and Supplementary Table 10). In conclusion, moderate fluorination facilitates the transport of Na+ and the formation of a more stable structure to resist redox reactions with metal Na.

In light of the considerable influence of temperature on the structural integrity of NZSP-xNSF (x = 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0), the pertinent thermal gravimetric-differential scanning calorimetry (TG-DSC) analyses were undertaken (Supplementary Fig. 10). The TG-DSC of NZSP-xNSF revealed that the TG curves of NZSP-xNSF exhibited minimal variation with the addition of Na2SiF6, indicating that NZSP-xNSF did not undergo significant mass loss at elevated temperatures. Furthermore, the DSC curve indicates the absence of a discernible heat absorption peak in NZSP-0.6NSF. In contrast, the heat absorption peak of NZSP-xNSF (x = 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 1.0) occurs for both a small amount and an excessive amount of doped Na2SiF6, indicating that NZSP-0.6NSF exhibits optimal thermal stability and does not undergo a phase transition at elevated temperatures. Moreover, the variable-temperature XRD of NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF at temperatures between 30 and 150 °C was conducted to further substantiate the hypothesis that NZSP-0.6NSF is capable of inhibiting phase transitions at elevated temperatures. The variable-temperature XRD plot of NZSP clearly demonstrates that after 110 °C, NZSP has undergone a complete phase transition. This observation is consistent with the TG-DSC results (Supplementary Fig. 11a). The variable-temperature XRD plots of NZSP-0.6NSF indicate that its crystal structure remains essentially unaltered between 30 and 150 °C (Supplementary Fig. 11b). This implies that NZSP-0.6NSF, which has been doped with 0.6 wt% Na2SiF6, can effectively suppress the phase transition and enhance the thermal stability of the SSE.

The mechanical properties of SSE sheets is also a crucial parameter for evaluating their resistance to Na dendrites. To this end, the nanoindentation tests were conducted on NZSP-xNSF (Supplementary Fig. 12). The load-displacement curves of NZSP-xNSF with varying doping levels were compared, and the corresponding elastic modulus (E) and hardness (H) were calculated (Supplementary Fig. 13). The elastic modulus and hardness of NZSP (E = 75.05 ± 3.78, H = 4.83 ± 0.96) are observed to be lower than those of NZSP-xNSF doped with Na₂SiF637. This indicates that Na₂SiF₆ doping can effectively improve the densification of the SSEs and enhance the covalency of the P-O and Si-O bonds, which stabilizes the structure of PO₄/SiO₄ tetrahedra within the SSEs, thus enhancing the ability of the SSEs to resist Na dendrites. It is noteworthy that NZSP-0.6NSF exhibits a leading elastic modulus and hardness (E = 90.58 ± 5.76, H = 6.37 ± 0.85) among the doped amounts of NZSP-xNSF (x = 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 1.0). This observation further suggests that the SSEs doped with an insufficient amount of Na2SiF6 are unable to effectively enhance the covalency of the P-O bonds38. Furthermore, the excessive doping of SSEs with Na₂SiF₆ may result in lattice distortion, which can disrupt homogeneity and consequently of SSEs lead to a reduction in elastic modulus and hardness. Consequently, the electronic structure of NZSP-0.6NSF can be effectively modulated by introducing Na2SiF6. This intervention enhances the covalency of the P-O and Si-O bonds, thereby stabilizing the structure of the PO4/SiO4 tetrahedra within the SSEs39. Such stabilization is anticipated to confer a more robust defense against Na dendrite formation. In conclusion, the NZSP-0.6NSF SSEs doped with 0.6 wt% Na2SiF6 were ultimately chosen for assessment of their corresponding symmetric half-cell and full-cell performances.

Subsequently, solid-state magic angle nuclear magnetic resonance (MAS NMR) spectroscopy was conducted on the 31P, 29Si, and 19F nuclei of both NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF to evaluate their respective structural characteristics. The 31P NMR spectrum of NZSP revealed two principal peaks: the primary peak at −11 ppm, indicative of the predominant phase of NZSP, and a secondary peak at 7 ppm, corresponding to a zirconium-deficient phase that arises during synthesis40. In comparison, the 31P NMR spectrum of the NZSP-0.6NSF exhibits shifts of both original peaks to lower chemical shifts (Fig. 1h). This shift indicates a decrease in electron density surrounding the P atoms, attributed to the substitution of O in the PO4 tetrahedron by the more electronegative F41. This substitution leads to a reduction in electron density around P, consequently enhancing the covalency of the P-O bonds. The consistent shift is observed in the 29Si NMR spectrum, where the peak of NZSP-0.6NSF is positioned at lower chemical shifts relative to NZSP42 (Fig. 1i). This phenomenon can be ascribed to the incorporation of the more electronegative F in place of O within the SiO4 tetrahedron43. Additionally, the 19F NMR spectrum of NZSP-0.6NSF distinctly displays two peaks, corresponding to Si-F and P-F bonds, respectively40 (Supplementary Fig. 14). Consequently, these findings confirm that fluorine is indeed incorporated within the PO4/SiO4 tetrahedra.

Furthermore, the F-doped sites were further probed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Comparing the XPS peaks of NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF indicates that NZSP-0.6NSF has peaks of F 1s in addition to Na 1s, Zr 3d, Si 2p, P 2p, and O 1 s. The F 1s peaks appear at 684.28 and 687.18 eV, representing the successful doping of F (Supplementary Fig. 15)44. Meanwhile, the results of XPS deep etching (750 and 1500 s) show that the F element is not only distributed on the surface of NZSP but also abundantly present in its interior. The positions of Na 1s and Zr 3d remain unchanged for NZSP-0.6NSF compared to NZSP45 (Supplementary Fig. 16). The difference is that the P 2p and Si 2p peaks of NZSP-0.6NSF are shifted to higher binding energies, which is because the high electronegativity of F attracts electrons around P and Si, resulting in a relative decrease in the electronegativity of P and Si atoms35,43 (Fig. 1f, g). Simultaneously, the O 1s peak of NZSP-0.6NSF shifts to higher binding energies due to lattice contraction, resulting in increased bonding energy between Si-O and P-O bonds46 (Supplementary Fig. 17). This tighter connection between the electron cloud of O atoms and surrounding Si and P atoms is responsible for the shift. The analytical findings indicate that F doping at the O sites within the PO4/SiO4 tetrahedra of NZSP modulates the electronic configuration of the tetrahedra. This modification enhances the covalency of the P-O and Si-O chemical bonds, thereby conferring enhanced stability upon the NZSP-0.6NSF.

Furthermore, the XPS characterization techniques have a limited depth of analysis, typically up to 100 nm below the surface layer. It was determined that the energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) characterization technique is typically able to semi-quantitatively analyze the composition of elements at an approximate depth of 1 μm below the surface layer. Consequently, the EDS characterization analysis of NZSP-0.6NSF SSEs were conducted to assess the F content semi-quantitatively. The SEM-EDS results clearly indicate that the chemical composition of NZSP-0.6NSF SSEs is comprised of Na, Zr, Si, P, and F elements (Fig. 1i). Additionally, the calculated molar ratio of Na, Si, and O is 16.32:9.96:60.28, which is in close alignment with the theoretical molar ratio (15:10:60) (Supplementary Fig. 18 and Supplementary Table 11). Furthermore, a uniform distribution of the Na, Zr, Si, P, O, and F elements in the NZSP-0.6NSF SSEs was also observed under transmission electron microscope-energy dispersive spectrometer (TEM-EDS) at a higher magnification (Supplementary Fig. 19). Additionally, the calculated molar ratio of Na, Si, and O is 16.95:10.14:61.62, which is also in good agreement with the theoretical molar ratio (Supplementary Fig. 20 and Supplementary Table 12). Nevertheless, the SEM-EDS and TEM-EDS results exhibit elevated Zr element concentrations and diminished P element concentrations. This discrepancy is attributed to the fact that the EDS energy spectrum lines of Zr (La, 2.04 KeV) and P (Ka, 2.02 KeV) elements are in close proximity, resulting in an overlap of the EDS spectral summits of Zr and P elements47. Consequently, the specific content of the Zr and P elements is subject to bias in the detection process. Accordingly, the F content in NZSP-0.6NSF SSE can be approximated semi-quantitatively through the use of SEM-EDS and TEM-EDS analyses, with the F content estimated to be ~0.6% on a molar basis. Moreover, given that the EDS characterization technique is only semi-quantitative, it remains challenging to accurately determine the precise doping amount of F element in NZSP-0.6NSF SSEs. In consideration of the relatively low content of Na₂SiF₆ dopant, a more sensitive ion chromatography characterization method was employed for the purpose of accurately quantifying the F content in NZSP-0.6NSF SSEs. The NZSP-0.6NSF SSEs were treated using the alkali fusion method, which facilitated the dissolution of the NZSP-0.6NSF SSEs in solution, thus enabling the testing of their F ions. As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 21, the peak corresponding to the F ion in NZSP-0.6NSF SSEs is observed at a retention time of 3.5 min. Subsequently, the fluorine concentration in the NZSP-0.6NSF SSEs was 0.0063 mg/L based on the linear relationship (Supplementary Fig. 22). These findings provide compelling evidence of fluoride doping into the SSEs.

Interface modification of solid electrolyte

To compare the cell performance of NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF, the interfaces were modified with SnF2. The XRD plots of SnF2-coated NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF show peaks at 25.1°, 26.3°, 27.8°, and 28.3°, which correspond to the (112), (204), (312), and (400) crystal planes of SnF248 (Supplementary Fig. 23). This illustrates that SnF2 is successfully coated on the surface of the SSEs. The SnF2-coated NZSP-0.6NSF and SnF2-coated NZSP SSEs were examined using cross-sectional SEM, and the thickness of the SnF2 coating was observed to be 18 μm (Supplementary Fig. 24). Both SnF2-coated NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF exhibit a tightly packed intermediate and outer SnF2 layer at the interface after SnF2 modification. This intermediate layer may be produced by the decomposition of SnF2 during its interaction with the SSEs at high temperatures. Interestingly, the major elemental distributions of SnF2-coated NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF are found to be Sn and F in both the middle and outer layers by EDS. Differently, elemental distributions of Na, Zr, Si and P are also found in the intermediate and outer layers of the SnF2-coated NZSP (Supplementary Fig. 25). Whereas, no distribution of these elements is found in the intermediate and outer layers on SnF2-coated NZSP-0.6NSF (Supplementary Fig. 26). The partial destruction of the NZSP structure occurs due to the interaction of SnF2 with the poorly structurally stabilized NZSP at high temperatures. In contrast, NZSP-0.6NSF exhibits improved structural stability, preventing its reaction with SnF2 at high temperatures and thus avoiding the destruction of the NZSP structure. In order to be more relevant to the actual electrolyte-SnF2 interaction, a TG-DSC test was conducted by mixing NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF SSEs powders with 1 wt% SnF2 powder (Supplementary Fig. 27). The TG curves show that there is almost no mass loss in the NZSP mixture with SnF2 and the NZSP-0.6NSF mixture with SnF2 in the same temperature range. Furthermore, the DSC curves of the NZSP mixture with SnF2 exhibited heat absorption peaks at lower temperatures and demonstrated a leading heat absorption compared to the NZSP-0.6NSF mixture with SnF2. This suggests that the NZSP-0.6NSF with SnF2 exhibits enhanced thermal stability. Consequently, the NZSP-0.6NSF can maintain its structural integrity at elevated temperatures and impede its decomposition and destruction during the interfacial modification process. This conclusion is consistent with the results of TG-DSC and variable temperature XRD of NZSP-0.6NSF. This is because F doping effectively regulates the electronic configuration of the SSEs, enhancing the covalency of the internal chemical bonds, which in turn stabilizes the internal structure of the NZSP-0.6NSF49,50.

The chemical composition at the interface of the SnF2-coated NZSP-0.6NSF pellet before and after contact with molten Na was determined using XPS analysis. For the NZSP-0.6NSF before melting Na, 495.6 and 487.2 eV correspond to Sn-F bonds in the Sn 3d XPS spectrum and at 684.9 eV in the F 1s XPS spectrum, respectively51 (Supplementary Fig. 28). This indicates that SnF2 is successfully coated onto the NZSP-0.6NSF surface. Upon reaction with molten Na, the XPS of Sn 3d exhibited two peaks of Sn0 metal48 (494.0 and 485.6 eV). Thermodynamically, the reaction causes the production of metal Sn0 to alloy with metal Na, forming NaxSn alloys such as Na15Sn4 and Na9Sn4. Additionally, the NaxSn alloy formed significantly improves the interfacial contact between the NZSP-0.6NSF and the Na metal. Concurrently, the XPS spectrum of F1s is shifted towards the low binding energy (684.2 eV), which indicates that the initial Sn-F is transformed into Na-F upon the melting of Na52. The NaF can promote the rapid transport of Na⁺ ions at the interface, preventing localized Na⁺ ion accumulation and thus effectively suppressing the formation of Na dendrites. Eventually, upon contact with molten Na, the interfacial layer at SnF2 generates a NaxSn alloy and NaF, bringing Na into close contact with the SSEs. Although the interfacial layer of SnF2 can effectively improve the contact between the metal Na and the SSE surface, the stability of the resulting interface will also depend on the properties of the SSEs itself. The interfacial impedance of SnF2-coated NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF was tested (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, the interfacial impedance was determined by fitting the impedance data of Na|SnF2-NZSP|Na and Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na symmetric cells to equivalent circuits. In the EIS spectra, the high-frequency intercept indicates the bulk resistance (Rb) of the electrolyte, the mid-high frequency semicircle corresponds to the grain boundary resistance (Rgb), and the low-frequency semicircle represents the interfacial resistance (Rint). Since the symmetric cell has two identical interfaces, the total Rint must be divided by 2 to obtain the impedance of a single interface. After fitting, the interfacial impedances of the Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na and Na|SnF2-NZSP|Na symmetric cells were found to be 2.0 and 6.5 Ω cm2 (Supplementary Table 13). Thus, this indicates that NZSP-0.6NSF can form a more stable interface with SnF2 to transport Na+. Furthermore, the density functional theory (DFT) was employed to assess the interfacial energy of NZSP and NZSP-NSF in the context of various compositions, including Na, NaF, and Na9Sn4 alloys48 (Supplementary Fig. 29). The interfacial formation energy of Na|NZSP-NSF (−1.36 J m−2) is more negative compared to that of Na|NZSP (−2.40 J m−2), suggesting that F doping intrinsically improves the natrophilic properties of NZSP. Furthermore, contact angle tests revealed that NZSP-0.6NSF SSEs have wettability with Na metal, evidenced by lower contact angles compared to the NZSP SSEs, indicating a more sodium-philic surface (Supplementary Fig. 30). In addition, the interfacial formation energy of NZSP-NSF to NaF and Na9Sn4 alloys (−3.87 J m−2, and −7.36 J m−2) is more negative compared to NZSP (−3.31 J m−2, and −6.72 J m−2), indicating that the interfaces between NaF and Na9Sn4 alloys and NZSP-NSF are more compatible and contactable.

a The symmetric cell impedance spectra for NZSP-0.6NSF and NZSP (inset). b, c Critical current density of the Na|SnF2-NZSP|Na and the Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na symmetric cells at 30 °C. d, e The GEIS of the Na|SnF2-NZSP|Na and the Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na symmetric cells under 0.3 mA cm−2 at different Na plating/stripping times. f Interfacial impedance evolution over time for Na|SnF2-NZSP|Na (inset) and the Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na symmetric cells. g, h The DRT test for Na|SnF2-NZSP|Na and the Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na symmetric cells. i Tafel curve test for Na|SnF2-NZSP|Na and the Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na symmetric cells (The yellow represents Na|SnF2-NZSP|Na, and red represents Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na).

To ascertain whether the SnF2-coated NZSP-0.6NSF possesses a more sodium-philic surface, contact angle experiments were conducted, whereby metallic Na was deposited on SnF2-coated NZSP and SnF2-coated NZSP-0.6NSF SSEs. A comparison of the contact angles of Na on the SnF2-coated NZSP and SnF2-coated NZSP-0.6NSF surfaces reveals that the latter has a significantly lower Na contact angle (Supplementary Fig. 31). This evidence conclusively demonstrates that SnF2-coated NZSP-0.6NSF is capable of inducing a more uniform deposition of Na metal. Furthermore, the SEM-EDS cross-sections of SnF₂-coated NZSP and SnF₂-coated NZSP-0.6NSF were examined before and after Na plating/stripping, respectively, to substantiate that SnF2-coated NZSP-0.6NSF can facilitate a more uniform deposition of Na metal. Obviously, both SnF2-coated NZSP and SnF2-coated NZSP-0.6NSF before Na plating/stripping are due to the introduction of SnF2 artificial interfacial layer, which allows Na metal to be in close contact with NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF (Supplementary Figs. 32 and 33). In addition, the thickness of the metal Na was 20 μm. However, the SEM-EDS cross-sections of SnF2-coated NZSP and SnF2-coated NZSP-0.6NSF after Na plating/stripping demonstrate that the contact between Na metal and NZSP deteriorates after Na plating/stripping, resulting in the formation of voids (Supplementary Figs. 34a and 35). This deterioration is attributed to the production of undesirable parasitic products by the reaction between NZSP and Na metal. Conversely, SnF2-coated NZSP-0.6NSF maintains close contact between NZSP and Na metal after Na plating/stripping (Supplementary Figs. 34b and 36). This further demonstrates that SnF2-coated NZSP-0.6NSF facilitates uniform deposition of Na metal due to the introduction of Na2SiF6. Furthermore, the impedance of SnF₂-coated NZSP and SnF₂-coated NZSP-0.6NSF was evaluated before and after Na plating/stripping (Supplementary Fig. 37). It was discovered that the SnF₂-coated NZSP resulted in a considerable enhancement in interfacial impedance following the Na plating/stripping process. This was attributed to the unfavorable parasitic reaction between the NZSP and Na metal, which led to the formation of voids at the interface of the NZSP|Na. In contrast, the impedance of SnF2-coated NZSP-0.6NSF remains essentially unaltered before and after Na plating/stripping. This further substantiates that the incorporation of Na2SiF6 into NZSP can effectively impede the detrimental reaction between Na metal and NZSP-0.6NSF, ensuring that NZSP-0.6NSF maintains consistent contact with Na metal throughout the Na plating/stripping process.

To summarize, the NZSP-NSF enhances the interfacial compatibility and stability with Na metal more effectively than the unmodified NZSP, thereby forming a more Na-compatible and stable interface that facilitates Na+ transport at the interface. Importantly, the NZSP-NSF modulates the internal electronic structure of SSEs through F incorporation, thereby enhancing the covalency of its internal chemical bonds. This modification leads to the formation of a thinner and denser NaF interfacial layer upon contact with Na, which inhibits further reaction between Na and the SSEs53. Such characteristics are instrumental in enabling the symmetric cells assembled with these SSEs to exhibit prolonged cycling performance at elevated current densities.

Symmetric half-cell performance of solid electrolytes

The SSEs with optimal electrochemical performance following doping were explored through the testing of the activation energy and critical current density (CCD) of Na|SnF2-NZSP-xNSF|Na symmetric cells of NZSP-xNSF at varying doping amounts. Initially, the impedance of the Na|SnF2-NZSP-xNSF|Na symmetric cells of NZSP-xNSF at varying doping levels at 25 °C was examined (Supplementary Fig. 38). It was observed that the Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na symmetric cells exhibited the lowest total and interfacial impedance, indicating that the SnF2-coated NZSP-0.6NSF exhibited the most optimal interfacial stability and. Secondly, the activation energies of Na|SnF2-NZSP-xNSF|Na symmetric cells with varying doping amounts were determined through impedance tests at temperatures ranging from 25 to 85 °C, complemented by computational fitting analysis (Supplementary Fig. 39). It is evident that the Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na symmetric cells exhibit the lowest activation energies, which suggests that NZSP-0.6NSF facilitates the rapid transport of Na+ ions at the interface. Finally, the capacity of NZSP-xNSF to withstand Na dendrimer at varying doping levels was assessed through the measurement of the CCD of Na|SnF2-NZSP-xNSF|Na symmetric cells (Supplementary Figs. 40 and 41). It was noteworthy that the symmetric half-cell of Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na exhibited a leading CCD (1.3 mA/cm2), while the symmetric half-cell of Na|SnF2-xNZSP|Na, which lacked doping of Na2SiF6, displayed the lowest CCD (0.6 mA/cm2) (Fig. 2b, c). Furthermore, it is demonstrated that doping Na2SiF6 can stabilize the SSE structure and inhibit Na dendrite formation by enhancing the covalency of P-O bonds within the SSE. Consequently, NZSP-0.6NSF demonstrates reduced reactivity with metallic Na, effectively suppressing Na dendrite formation and enabling a higher critical current density. In addition, the DFT reveals that NZSP-NSF has a higher interfacial energy for NaF than NZSP. Therefore, this causes more ion-conducting NaF to aggregate on the NZSP-0.6NSF side, forming a NaF-rich interfacial layer. This NaF-rich interfacial layer not only reduces the interfacial impedance and makes the transport of Na+ more uniform, but also effectively inhibits Na dendrites54. Thus, the NZSP-0.6NSF with a more stable structure can more effectively inhibit Na dendrites and have better electrochemical performance.

Unidirectional galvanostatic electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (GEIS) studies were performed on Na-symmetric half cells at a current density of 0.3 mA cm-2 to further understand the stability changes of the SSEs during Na plating/stripping. Since NZSP is more likely to destroy the internal structure with further depletion of Na, it can be seen that the symmetric cells of Na|SnF2-NZSP|Na can only be cycled stably for 4 h before a cell short circuit occurs, and both its impedance and voltage values rapidly drop to 0 (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 42a). Surprisingly, the Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na symmetric cells have significantly improved the stripping performance of Na (Fig. 2e). The symmetric half-cell of Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na can stably strip Na for over 10 h with an interfacial resistance lower than 10 Ω cm2 and very low polarization voltage (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 42b). This demonstrates outstanding interfacial stability and the ability of NZSP-0.6NSF to resist deep discharge55. This further validates that the enhanced covalency of the internal chemical bonds within the NZSP-0.6NSF during Na plating/stripping is validated to contribute to extended cycle life, thereby achieving cell performance.

The GEIS results were further analyzed using the distribution of relaxation times (DRT) technique56. The transformation principle of this DRT is to transform the entire EIS data into a relaxation-based function γ(τ) (Supplementary Fig. 43). The DRT plot displays various electrochemical processes and impedance values through different peak positions and areas, respectively. The peak at τ < 1.6 × 10−7 s represents the grain boundary impedance of the NZSP55. The range of 1.6 × 10−3– 1.6 × 10−2 s represents the charge transfer process at the negative electrode, while the range of 10−1–10 s represents the process of interfacial Na+ transport57 (Rint). For the Na|SnF2-NZSP|Na symmetric cell in the process of Na stripping, the intensity of the corresponding Rint peak in the occurrence of an increase in the Na+ stripping capacity of the maximum only to 0.9 mA h cm−2, indicating poor interface dynamics during the stripping process of NZSP and damage to its structure (Fig. 2g and Supplementary Fig. 44a). In contrast, the intensity of the Rint peak of the Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na symmetric cell does not change significantly until it reaches 2.1 mA·h cm−2, indicating that NZSP-0.6NSF is more inhibition to the reduction of Na, making the overall structure less likely to be damaged (Fig. 2h and Supplementary Fig. 44b). To further investigate the chemical reaction processes at the interface, Tafel curves were tested in the high overpotential region for the exchange current density (j) of symmetrical half-cells. The exchange current density of Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na (0.204 mA cm−2) is significantly higher than that of Na|SnF2-NZSP|Na (0.141 mA cm−2), reflecting the faster transport kinetics of Na+ at the interface of NZSP-0.6NZSP (Fig. 2i). Therefore, the construction of NZSP-0.6NSF SSEs with enhanced covalency of P-O and Si-O chemical bonds is of great significance. It facilitates a well-ordered Na+ transfer interface and mitigates the risk of structural degradation from interactions with metallic Na during the charge-discharge processes.

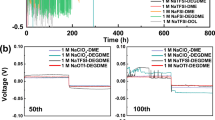

Galvanostatic Na plating/stripping tests were also used to characterize the stability of the cell interface. The symmetrical half-cells of Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na can be operated stably for 6000 h at 0.2 mA cm−2 with a polarization voltage of only 15 mV (Fig. 3a–d), while the symmetrical half-cells of Na|SnF2-NZSP|Na can be operated stably for only 100 h at 0.2 mA cm−2 with a polarization voltage of 32 mV (Fig. 3b). At higher current density (0.5 mA cm−2), the symmetrical half-cells of Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na can still be stabilized for 3600 h (polarization voltage of 42 mV), while the symmetrical half-cells of Na|SnF2-NZSP|Na can only operate for 7 h (Fig. 3e–h). According to available information, the Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na symmetric cell cycle has been maintained for a considerable time at high current densities (Supplementary Fig. 45 and Supplementary Table 14). To verify whether the symmetrical half-cells of Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na are shorted during prolonged Na plating/stripping, the impedance values at current densities of 0.2 mA cm−2 and 0.5 mA cm−2 are calculated using law of Ohm to be 75 Ω cm2 and 84 Ω cm2, respectively, which are very close to the actual test results. In summary, the NZSP-0.6NSF, endowed with enhanced covalency within its PO4/SiO4 tetrahedra, facilitates expedited Na+ transport at the interface and shields the SSEs from degradation throughout Na plating/stripping. This robustness is pivotal for achieving extended cycle life at elevated current densities.

a Galvanostatic Na plating/stripping performance of the Na|SnF2-NZSP|Na and Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na symmetric cell under 0.2 mA cm−2/0.1 mAh cm−2 at 30 °C. b–d Enlarged view of the galvanostatic curve under 0.2 mA cm−2/0.1 mAh cm−2 at different times. e Galvanostatic Na plating/stripping performance of the Na|SnF2-NZSP|Na and Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na symmetric cells under 0.5 mA cm−2/0.25 mAh cm−2 at 30 °C. f–h Enlarged view of the galvanostatic curve under 0.5 mA cm−2/0.25 mAh cm−2 at different times.

Full-cell performance of solid electrolytes

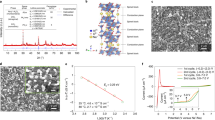

The NZSP-0.6NSF has been demonstrated to effectively improve ionic conductivity and to form a stable structure that inhibits Na dendrite formation. This provides favorable conditions for full-cell assembly. Therefore, the performance of SSEs for practical applications was evaluated using NVP as the positive electrode. In the beginning, the rate performance of the quasi-solid-state cell of Na|SnF2-NZSP | NVP and Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP was tested (Fig. 4a). In comparison, the Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP cell exhibits outstanding rate performance (Fig. 4b, c). The discharge-specific capacity of Na|SnF2-NZSP|NVP is significantly lower than that of Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP at different rates. To further confirm the ability of NZSP-0.6NSF to resist redox during electrochemical processes, the cycling performance of Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF | NVP full cell was tested at a rate of 1 C (1 C = 117 mA g−1) (Fig. 4d). The cycling performance of the Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF | NVP during charge and discharge is shown in Fig. 4e. The discharge-specific capacity of Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP at 1 C is 110.32 mAh g−1, and the capacity retention rate after 2500 cycles of stable cycling is as high as 87.5%, demonstrating excellent cycling performance. Relative to existing studies, this work demonstrates a notably higher discharge specific capacity and cycle life at a 1 C rate (Supplementary Fig. 46). In addition, the average Coulombic ratio efficiency was as high as 99.96% during the 2500 cycles, which indicates that NZSP-0.6NSF has higher energy conversion efficiency and less occurrence of interfacial side reactions. For comparison, the cycling performance of the Na|SnF2-NZSP|NVP full cell at 1 C was also tested (Fig. 4f). Although its discharge-specific capacity can be comparable to that of NZSP-0.6NSF at the initial stage, the structure of NZSP is prone to damage as the number of cycles increases, resulting in a capacity retention rate of only 65.5% after 200 cycles. Consequently, the NZSP-0.6NSF is capable of forming strongly covalent PO4/SiO4 tetrahedra, thereby reinforcing the structure of the SSEs and safeguarding it from degradation during charge and discharge cycles. This enhanced stability is instrumental in curtailing the formation of internal Na dendrites, which in turn is critical for preventing failure in SSBs.

a Rate performances of Na|SnF2-NZSP|NVP and Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP full cell (the blue represents Na|SnF2-NZSP|NVP, and red represents Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP). b, c Charge-discharge profiles of Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP and Na|SnF2-NZSP|NVP cell at various rates. d–f Cycle performance of the Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP and Na|SnF2-NZSP|NVP cell under 1 C (1 C = 117 mA g−1) at 25 °C. g, h Cycle performance of the Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP cell under 5 C (5 C = 585 mA g−1) at 25 °C.

The above results indicate that the full cell assembled with NZSP-0.6NSF exhibits stability when compared to the NZSP. To verify the structural stability of the NZSP-0.6NSF at higher rate levels following enhancements in P-O and Si-O covalency, the Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF | NVP full cell underwent long cycling tests at a high rate of 5 C (5 C = 585 mA g−1) (Fig. 4g). Surprisingly, Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF | NVP delivers a discharge-specific capacity of 100.11 mAh g−1 at 5 C and a capacity retention of 96.1% after 1200 cycles (Fig. 4h). This study presents a quasi-solid-state sodium battery with good stability and specific energy output, capable of operating at high discharge rates exceeding 5 C (Supplementary Fig. 47 and Supplementary Table 15). In conclusion, the incorporation of Na2SiF6 in NZSP-0.6NSF enables enhanced capacity retention and extended service life in SSBs. This is achieved by modulating the internal electronic structure to establish PO4/SiO4 tetrahedra with robust covalent bonds. Such structural integrity diminishes the likelihood of redox reactions between the SSEs and metallic Na, even under high specific current conditions.

Mechanistic investigation of redox-resistible solid electrolytes

The characterization of the interphase changes at the interface between SSEs and metallic Na before and after Na plating/stripping is challenging when SnF₂ is applied as a coating on the surface of SSEs. This difficulty arises due to the SnF₂ interfacial layer constructed at the interface, which impedes precise characterization of the SSEs surface. To simulate the impact of SnF2 coating on the SSEs surface, SnF2-modified Na was prepared by adding SnF2 to molten Na to assemble symmetrical cells of Na+SnF2|NZSP|Na+SnF2 and Na+SnF2|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na+SnF2. This approach facilitates the removal of SnF2-modified Na from the SSEs surface, effectively circumventing the obstruction posed by the SnF2 coating in characterizing the SSEs surface. Consequently, it becomes feasible to investigate the changes in the SSEs surface before and after Na plating/stripping of Na+SnF2|NZSP|Na+SnF2 and Na+SnF2|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na+SnF2 symmetrical cells, further exploring the reasons why NZSP-0.6NSF can resist redox reactions.

As shown in Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Table 16, the interfacial impedance of Na+SnF2|NZSP|Na+SnF2 (720.5 Ω cm2) is significantly higher than that of Na+SnF2|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na+SnF2 (54.5 Ω cm2). This indicates that after Na2SiF6 doping, the fluorine present on the NZSP-0.6NSF surface enables a more intimate contact between NZSP-0.6NSF and SnF2-modified Na. This results in relatively lower interfacial impedance in the assembled Na+SnF2|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na+SnF2. This phenomenon can be clearly observed through cross-sectional SEM-EDS analysis of NZSP-0.6NSF with SnF2-modified Na (Supplementary Fig. 48). Moreover, after Na plating/stripping, the interfacial impedance of the Na+SnF2|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na+SnF2 symmetric half-cell remains low at 60.45 Ω cm2. This suggests that NZSP-0.6NSF, with its enhanced P-O covalency, effectively suppresses parasitic interfacial reactions with metallic Na. This maintains the structural stability of the SSEs during Na plating/stripping and preserves the low interfacial impedance. In contrast, Na+SnF2|NZSP|Na+SnF2 exhibits an elevated interfacial impedance. This is due to that although the SnF2 modification facilitates contact between metallic Na and NZSP, certain voids still exist at their interface. These voids significantly increase the interfacial impedance. The cross-sectional SEM-EDS images of NZSP coated with SnF2-modified Na clearly show these gaps, resulting in higher interfacial impedance (Supplementary Fig. 49). Additionally, since NZSP itself remains unstable against metallic Na, interfacial parasitic side reactions occur during Na plating/stripping of Na+SnF2|NZSP|Na+SnF2. This leads to structural degradation of NZSP and eventually causes battery failure due to Na dendrite formation.

a, b The symmetric cell impedance spectra before and after Na plating/stripping of Na+SnF2|NZSP-0.6|Na+SnF2 and Na+SnF2|NZSP|Na+SnF2. c–e XPS deep etching spectra of Zr 3d, P 2p, and Si 2p before and after Na plating/stripping of NZSP. f–h XPS deep etching spectra of Zr 3d, P 2p and Si 2p before and after Na plating/stripping of NZSP-0.6NSF (The cycled Na+SnF2|NZSP|Na+SnF2 and Na+SnF2|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na+SnF2 were obtained by cycling Na+SnF2|NZSP|Na+SnF2 and Na+SnF2|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na+SnF2 after Na plating/stripping at 0.025 mA cm−2 for 20 cycles at 30 °C. Then, the cycled cells were disassembled and treated with anhydrous ethanol to remove Na to obtain cycled NZSP and cycled NZSP-0.6NSF). i, j The 3D render TOF-SIMS of CsNaF+, Cs3NaPO4+, Cs2Na2PO3+, Cs2Na3P+, and Cs2Na2P+ of cycled-NZSP and cycled-NZSP-0.6NSF for Na+SnF2|NZSP-0.6|Na+SnF2 and Na+SnF2|NZSP|Na+SnF2 (The cyan represents low concentration of the substance, while brown represents high concentration of the substance).

Furthermore, the Na+SnF2|NZSP|Na+SnF2 system stabilize for 25 h under 30 °C at 0.025 mA cm−2 (Supplementary Fig. 50a), whereas the Na+SnF2|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na+SnF2 system achieve 1000 h (Supplementary Fig. 50b). Moreover, the impedance of Na+SnF2|NZSP|Na+SnF2 decreases significantly after Na plating/stripping, whereas the impedance of Na+SnF2|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na+SnF2 remains unchanged after Na plating/stripping. This further illustrates that NZSP-0.6NSF has a more sodiumophilic surface compared to NZSP and can inhibit Na dendrites more effectively. The dendrite suppression capability of the SSEs is further revealed through CCD testing in the systems Na+SnF2|NZSP|Na+SnF2 and Na+SnF2 |NZSP-0.6SF|Na+SnF2. The CCD of Na+SnF2|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na+SnF2 (0.35 mA cm−2) substantially exceeds that of Na+SnF2|NZSP|Na+SnF2 (0.05 mA cm−2), indicating that the NZSP-0.6NSF effectively inhibits reactions with Na and enhances the interfacial stability (Supplementary Fig. 51). Overall, the enhanced covalency of the PO4/SiO4 tetrahedra in NZSP-0.6NSF confers an increased resistance to redox reactions with Na.

Moreover, the changes in SSEs composition before and after Na plating/stripping of Na+SnF2|NZSP|Na+SnF2 and Na+SnF2|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na+SnF2 symmetric cells were further analyzed to investigate the mechanism of NZSP-0.6NSF with redox-resistible property. The SEM cross-sectional images distinctly demonstrate that the crystal surface of the cycled NZSP is obscured and its boundaries are indistinct, suggesting a reaction with Na that compromises the structural integrity of NZSP and results in the formation of by-products, thereby altering its morphology31 (Supplementary Fig. 52). In stark contrast, the NZSP-0.6NSF retains its crystal structure with clarity and without observable change post-Na plating/stripping. This preservation is attributed to the introduction of F, which enhances the covalency of the P-O and Si-O bonds, thereby stabilizing the NZSP-0.6NSF structure against sodium-induced reactions. The cycled NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF sheets were further analyzed at the surface and the 60 and 120 s of etching using XPS deep etching, respectively. For the cycled NZSP, the binding energy of Zr in the deep etching spectroscopy of Zr 3d shift toward lower binding energies and shoulder peaks appear at even lower binding energies (Fig. 5c). The shoulder peak may correspond to conductive ZrSi, a potential product resulting from the interaction between NZSP and Na metal29. The formation of this conductive ZrSi is detrimental as it induces continuous interfacial reactions, potentially explaining the instability of NZSP during Na plating/stripping. Additionally, the interaction between Na and NZSP during Na plating/stripping has led to a shift in the Na 1s peak towards lower binding energies in the XPS deep etching analysis of the cycled NZSP58 (Supplementary Fig. 53a). Moreover, in the XPS deep etching spectra of P 2p and Si 2p, the observed shift towards lower binding energies indicates that the reaction between Na and NZSP compromises the structural integrity of the PO4/SiO4 tetrahedra within NZSP30 (Fig. 5d, e). Additionally, the emergence of two peaks corresponding to NaxPOy and NaxP species in the P 2p spectrum at lower binding energies is indicative of a reaction between metallic Na and the weakly covalent PO4 tetrahedra within NZSP59. This interaction culminates in the disruption of the P-O covalent bonds, yielding the observed products. Therefore, this finding corroborates the susceptibility of the P-O bonds within NZSP to sodium-induced degradation. In contrast, the XPS deep etching spectra of Zr 3d, P 2p, Si 2p, and Na 1s peaks of the cycled NZSP-0.6NSF remain essentially unchanged following Na plating/stripping (Fig. 5f–h and Supplementary Fig. 53b). The findings indicate that F supplementation significantly bolsters the covalency of the chemical bonds within the PO4/SiO4 tetrahedra of NZSP-0.6NSF. This enhancement diminishes the reactivity between the SSEs and Na, culminating in the achievement of stable SSBs performance even at elevated specific currents.

In addition, time-of-flight secondary-ion mass spectroscopy (TOF-SIMS) was performed to test cycled NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF to determine their stability by identifying the distribution of the products generated upon reaction with Na, respectively (Fig. 5i, j). In the TOF-SIMS depth profiles, the CsNaF+ signals from cycled NZSP are distinctly oriented perpendicularly to the SSEs sheet, exhibiting substantial variability in penetration depth. Conversely, the 3D render of CsNaF+ signals from cycled NZSP-0.6NSF demonstrates thin and dense distribution along the surface of the NZSP-0.6NSF. Upon Na plating/stripping, the detection of NaF on the SSEs sheet is attributed to the SnF2 in the molten Na, which induces the formation of an interfacial NaF layer. In contrast, the NZSP experiences a reactive interaction with Na during Na plating/stripping, leading to structural degradation. This interaction promotes the infiltration of NaF and Na into the SSEs, resulting in the development of a thick and inhomogeneous NaF interfacial layer. The incorporation of F in NZSP-0.6NSF augments the covalency of the P-O bonds, thereby enhancing its resistance to reaction with Na during electrochemical cycling. Furthermore, the introduced F- facilitates the formation of a compact NaF interfacial layer, which is more effective in mitigating the growth of Na dendrites. In the 3D render TOF-SIMS depth profiles of cycled NZSP, the presence of Cs3NaPO4+, Cs2Na2PO3+ Cs2Na2P+, and Cs2Na3P+ on the surface and interior of NZSP is observed, indicative of the P-O bond breaking by Na during electrochemical cycling, resulting in the formation of NaxPOy and NaxP27. This conclusion is also consistent with the XPS of the cycled NZSP.

In contrast, cycled NZSP-0.6NSF showed negligible presence of these species, suggesting that the introduction of F effectively stabilizes the P-O bond against Na-induced degradation, thereby preventing dendrite formation. Moreover, time-resolved TOF-SIMS mapping of cycled NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF at intervals of 0 s, 100 s, 200 s, 400 s, and 800 s reveals a notable presence of Cs3NaPO4+, Cs2Na2PO3+, Cs2Na2P+, and Cs2Na3P+ ions in the cycled NZSP, which are notably less abundant in the NZSP-0.6NSF (Supplementary Fig. 54). This observation is corroborated by the TOF-SIMS depth profiling results, further substantiating that NZSP is susceptible to redox reactions with metallic Na during Na plating/stripping (Supplementary Fig. 55). These reactions lead to the degradation of the PO4 tetrahedra, producing by-products such as NaxPOy and NaxP29. This degradation compromises the interface between NZSP and Na, contributing to the failure of the solid-state cell. In contrast, the NZSP-0.6NSF, due to the incorporation of the highly electronegative F, modulates the electronic structure of the PO4 tetrahedra and strengthens the P-O covalent bonds. This enhancement in covalency confers resistance to further redox reactions between Na and the SSEs, thereby facilitating the realization of high-performance SSBs.

The DFT was performed to gain a deeper understanding of the origin of the redox-resistible property of NZSP-NSF. In the construction of the NZSP-NSF model, the position of an O atom in the PO4 tetrahedron in the NZSP structure was replaced by an F atom. With regards to the Na|NZSP interface, it can be observed that when the PO4 tetrahedra of the NZSP interact with Na atoms, the P-O bonds in the PO4 tetrahedra are broken and NaxPOy or NaxP are formed, resulting in a rapid decomposition of the SSEs (Fig. 6a). The interfacial reconstruction indicates that phosphate or Na3P formation at the Na|NZSP interface is facile, which is consistent with the experimental results previously described. In contrast, the F-PO4 tetrahedron of NZSP-NSF presents an intact structure at the Na|NZSP-NSF interface and is not disintegrated (Fig. 6b). This suggests that the presence of F atom can effectively inhibit the metal Na from disrupting the P-O bond. The structural differences between the Na|NZSP and Na|NZSP-NSF interfaces are primarily attributed to the alterations in the electronic structure and covalency between P-O bonds in NZSP resulting from the doping of F atoms.

a, b Schematic atomic structure of Na|NZSP and Na|NZSP-NSF system at initial and post-reaction. c, d The local electronic structure of NZSP and NZSP-NSF. e, f Crystal orbital hamilton population of NZSP and NZSP-NSF. g Diagram of the energy gap between P-p, O-p, and F-p band center of PO4 unit in NZSP and F-PO4 unit in NZSP-NSF. h Schematic representation of the redox reaction process of NZSP and NZSP-NSF with Na (The orange balls represent Na atoms, blue balls represent Si atoms, purple balls represent P atoms, yellow balls represent O atoms, and red balls represent F atoms).

The results of the electron localization function (ELF) analysis demonstrate that the electrons are distributed around the P and O atoms in the PO4 tetrahedra of the pristine NZSP (Fig. 6c, Supplementary Data 1). While with F doping, electron redistribution occurs in the F-PO4 tetrahedra in NZSP-NSF, where the P atoms point their electrons toward the surrounding O atoms60. This phenomenon can be attributed to the higher electronegativity of F, which induces a (Fig. 6d, Supplementary Data 1) redistribution of electrons in the PO4 tetrahedron. In general, larger ELF values are indicative of the presence of covalent bonds or lone electron pairs within the fixed domain. Consequently, the incorporation of F into the NZSP-NSF SSEs enhances the covalency of the P-O bonds, thereby stabilizing the structure of the PO4 tetrahedra.

These changes in electron distribution and bonding energy of the P-O bond were further detected by crystal orbital Hamilton population (COHP) and projected density of states (PDOS). As demonstrated by the COHP analysis, the bond length of the P-O bond in the F-PO4 tetrahedron in NZSP-NSF (1.50 Å) is slightly shorter than that in the PO4 tetrahedron in NZSP (1.54 Å), indicating that NZSP-NSF can enhance the bond strength of the P-O bond to a greater extent. Moreover, the analysis conducted by the integrated crystal orbital Hamilton population (-ICOHP) indicates that the bonding strength of the P-O bonds of the F-PO4 tetrahedra in NZSP-NSF (10.53 eV) is significantly greater than that of the P-O bonds of the PO4 tetrahedra in NZSP61 (9.72 eV) (Fig. 6e, f). This suggests that the NZSP-NSF can effectively enhance the covalency of the P-O bond and impede its reaction with Na, thereby preventing the destruction of the SSEs structure62,63. In addition, the PDOS conducted a comparative analysis of PO4 and F-PO4 tetrahedra in NZSP and NZSP-NSF, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 56). In comparison to the NZSP, both the O 2p and P 2p energy bands at the bonding state in NZSP-NSF exhibit a shift towards lower energies relative to the Fermi energy level, suggesting that the incorporation of F enhances the stability of the P-O bond64. Furthermore, the orbital overlap of F and P observed in NZSP-NSF indicates the formation of P-F covalent bonds. This is because F, due to its greater electronegativity, is prone to form P-F chemical bonds, which further stabilizes the structure of PO4 tetrahedra. The results of the DFT calculations indicate that the antioxidative reduction properties of NZSP-NSF are primarily attributable to the F doping, which induces electron redistribution in the PO4 tetrahedra, thereby constructing a more covalent P-O bond, which renders it less susceptible to reaction with Na (Fig. 6h). Consequently, modulating the intrinsic electronic structure of SSEs, particularly that of the PO4 tetrahedra, and increasing the covalency of P-O may be a fundamental strategy to inhibit redox reactions at the interface of NZSP SSEs during Na plating/stripping.

Distinguishing the role between doping and SnF2 on solid electrolytes

To investigate the impact of an artificial interfacial layer SnF2 and a Na2SiF6 dopant on the cycling stability and cell performance of SSEs, symmetric cells and full-cells of NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF were assembled by pasting Na metal (Na|NZSP/NZSP-0.6NSF|Na and Na|NZSP/NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP). Furthermore, SnF2 powder is incorporated into metallic Na to obtain SnF2-modified Na, thereby enhancing the wettability of metallic Na on NZSP and NZSP-0.6 NSF surfaces. This serves to better illustrate the sodium-philic role of SnF2, while diminishing the possibility that SnF2, when applied as a coating on the surface of SSEs, may suppress interfacial side reactions. Consequently, symmetric cells and full-cells of NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF with modified Na metal were assembled (Na+SnF2|NZSP/NZSP-0.6NSF|Na+SnF2 and Na+SnF2|NZSP/NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP).

First, impedance tests on Na|NZSP|Na and Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na symmetric cells revealed that the interfacial impedance of Na|NZSP|Na (1970 Ω cm2) is markedly larger than that of Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na (190 Ω cm2) (Supplementary Fig. 57). This further suggests that Na2SiF6-doped NZSP-0.6NSF significantly reduces the interfacial impedance due to enhanced P-O covalency, which impedes interfacial side reactions. Furthermore, it is observed that the interfacial impedance of Na+SnF2|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na+SnF2 is markedly lower than that of Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na. However, its interfacial impedance value is larger than that of Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na (2.0 Ω cm2). This indicates that SnF₂ can effectively enhance the sodium-philic of the SSEs for Na metal, facilitating close contact between the Na metal and the SSEs and reducing the increase in interfacial impedance due to poor physical contact. Furthermore, SnF₂ coating on the surface of the SSEs can more efficiently induce uniform deposition of Na metal on the surface of the SSEs, thereby reducing the interfacial impedance.

Secondly, the CCD of the Na|NZSP|Na and Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na symmetric cells were tested, and it was observed that the CCD of Na|NZSP|Na (0.025 mA cm−2) was markedly lower than that of Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na (0.2 mA cm−2) (Supplementary Fig. 58). Additionally, the rate performance of the full cell assembled with Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP (Supplementary Fig. 59a, b) markedly surpasses that observed with Na|NZSP|NVP (Supplementary Fig. 60a, b). The discharge-specific capacity of Na|NZSP|NVP is significantly lower than that of Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP at different rates. This also indicates that the NZSP-0.6NSF doped with Na₂SiF₆ can significantly inhibit interfacial side reactions due to the improvement of the P-O covalent nature, which enhances the ability to resist Na dendrites. In addition, both Na|NZSP|NVP and Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP exhibit negligible discharge capacity at high rate 5 C. This suggests that by directly affixing the Na sheet, it will be challenging to operate the battery at high specific current due to the unstable contact at the negative electrode interface. Furthermore, the rate performance of a full cell assembled with SnF₂-modified Na exhibited a similar trend (Supplementary Fig. 61a, b). Specifically, the discharge-specific capacity of Na+SnF2|NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP is significantly higher than that of Na+SnF2|NZSP|NVP at different rates. Furthermore, the discharge capacity of Na+SnF2|NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP is significantly greater than that of Na+SnF2|NZSP|NVP at a high rate of 5 C. This further indicates that doping Na₂SiF₆ is an effective method of enhancing the stability of the electrolyte in contact with metallic Na, while simultaneously inhibiting the generation of Na dendrites. However, it has been observed that the CCD and rate performance of the Na+SnF2|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na+SnF2 symmetric cells and the Na+SnF2|NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP full-cells, which are assembled with SnF2-modified Na, significantly outperform those of the Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na symmetric cells and Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP full-cells (Supplementary Fig. 62a, b). Nevertheless, they are slightly inferior to the rate performance of the SnF2-coated Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na symmetric cells and Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP full-cells. This further indicates that SnF2, when applied as a coating on the SSE, also possesses the properties to suppress the growth of Na dendrites and enhance the transport of Na+ ions at the interface.

Thirdly, the cycle stability of Na|NZSP|Na, Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na, Na+SnF2|NZSP|Na+SnF2, and Na+SnF2|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na+SnF2 symmetric cells were subsequently evaluated (Supplementary Figs. 50 and 63). The results demonstrate that both the Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na (70 h at 0.025 mA cm−2) and Na+SnF2|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na+SnF2 (1000 h at 0.025 mA cm−2) symmetric cells assembled by NZSP-0.6NSF exhibit excellent capabilities due to the significant inhibition of interfacial side reactions by NZSP-0.6NSF. In contrast, the assembled Na|NZSP|Na (3 h at 0.025 mA cm−2) and Na+SnF2|NZSP|Na+SnF2 (25 h at 0.025 mA cm−2) symmetric cells exhibited markedly reduced stability and were unable to withstand extended cycling. This is because unmodified NZSP becomes unstable due to interfacial side reactions and is unable to undergo stable cycling. Similarly, the same regularity trend was observed when testing the cycling stability of full cells assembled with Na|NZSP|NVP, Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP, Na+SnF2|NZSP|NVP, and Na+SnF2|NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP at 1 C rate. In particular, the capacity retention rate of Na|NZSP|NVP assembled with Na patch is observed to be only 18.75% after 50 cycles at 1 C (Supplementary Fig. 59c, d). In contrast, Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP exhibits a capacity retention of 57.58% after 80 cycles at 1 C (Supplementary Fig. 60c, d). The discharge capacity and capacity retention rate of Na+SnF2 | NZSP-0.6NSF | NVP assembled with SnF2-modified Na (72.85% capacity retention after 120 cycles) are markedly higher than those of Na+SnF2|NZSP|NVP (97.62% capacity retention after 200 cycles) at 1 C (Supplementary Figs. 61c, d and 62c, d). This further indicates that NZSP-0.6NSF with enhanced P-O covalency can effectively improve the cycling stability of the battery and effectively inhibit the generation of Na dendrites. Surprisingly, the stability of symmetric cells Na+SnF2|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na+SnF2 and full-cells Na+SnF2|NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP, assembled with SnF2-modified Na, is notably inferior compared to those of symmetric cells Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na and full-cells Na|SnF2-NZSP-0.6NSF|NVP, which are assembled with SnF2-coated NZSP-0.6NSF. This observation underscores the effectiveness of SnF2 when applied as a coating on the SSE, as it significantly contributes to stabilizing the interface and suppressing the formation of Na dendrites.

Finally, the cycled Na|NZSP|Na and cycled Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na were obtained by cycling Na|NZSP|Na and Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na after Na plating/stripping at 0.025 mA cm−2 for 20 cycles at 30 °C. The results demonstrated that cycled Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na (178.5 Ω cm2) exhibited minimal change, whereas the impedance of cycled Na|NZSP|Na (15640 Ω cm2) was significantly increased (Supplementary Fig. 57). The impedance of Na|NZSP|Na was markedly elevated, thereby corroborating the hypothesis that NZSP would undergo an interfacial parasitization reaction as a consequence of its interaction with Na metal. The formation of parasitic products at the interface resulted in an increased impedance. However, NZSP-0.6NSF demonstrated an ability to resist the interfacial parasitic reaction, which can be attributed to an enhancement in P-O covalency. Similarly, impedance tests on post-Na plating/stripping Na+SnF₂|NZSP|Na+SnF₂ (short circuit) and Na+SnF₂|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na+SnF₂ (60.45 Ω cm2) symmetric cells, as well as on post-Na plating/stripping Na|SnF₂-NZSP|Na (19 Ω cm2) and Na|SnF₂-NZSP-0.6NSF|Na (5 Ω cm2) symmetric cells, yielded the same experimental conclusion (Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Fig. 37).

To further differentiate the effects of the SnF2 interfacial layer and doped Na2SiF6 on SSEs, the interfacial ion diffusion energy barriers of Na+ ions in NaF and Na3PO4 were calculated (Supplementary Data 2). The DFT calculations of Na+ ions interface diffusion energy barriers in NaF show very low values, enabling rapid Na+ ion transport at the interface while preventing Na dendrite formation (Supplementary Figs. 64a, c). In contrast, metallic Na reacts with NZSP to produce NaxPOy interface byproducts with poor Na+ ions transport capabilities. This leads to continuous degradation of the NZSP structure, causing uneven Na+ distribution and subsequent Na dendrite formation. Therefore, the interface diffusion energy barriers of Na+ ions in Na3PO4 were calculated to further confirm this perspective. Clearly, the barriers are significantly higher than in NaF (Supplementary Fig. 64b, d). This further demonstrates that constructing NaF-rich interface layers facilitates rapid Na+ ion transport, preventing local Na+ ion accumulation that would cause uneven charge distribution and Na dendrite formation. Conversely, interface products that slowly transport Na+ ions cause local Na+ ion accumulation at the interface, resulting in uneven charge distribution and Na dendrite formation. Therefore, the enhancement of P-O covalency by doping Na2SiF6 can essentially inhibit the side reaction between metal Na and electrolyte. In conjunction with the modification of the SnF2 interface layer, a stable structure that facilitates the transport of Na+ ions at the interface can be effectively constructed, thereby enabling the realization of a high-performance quasi-solid-state sodium battery.

To further elucidate the impact of Na₂SiF6 doping on the stability of SSEs, TEM was employed to characterize NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF, respectively. The morphology of both NZSP and NZSP-0.6NSF exhibited a uniform distribution of grains without notable aggregation (Supplementary Fig. 65). Upon further magnification, the lattice fringes of the SSEs can be clearly observed in NZSP, wherein the fringes corresponding to the (−3, 1, 3), (−4, 2, 2), and (1, 1, 2) grain planes are readily discernible. Furthermore, the distribution of (−2, 2, 2), (−4, 0, 2), (4, 4, 0) and (−8, 0, 4) crystalline facets can be observed at the periphery of the grains (Supplementary Fig. 66). Furthermore, lattice streaks with distributions of (−3, 1, 3), (−4, 2, 2), and (1, 1, 2) grain faces were observed in NZSP-0.6NSF (Supplementary Fig. 67). However, the crystal plane spacing corresponding to these crystal planes of NZSP-0.6NSF is observed to be lower than that corresponding to these crystal planes of NZSP. This further suggests that the doping of F into the PO4 tetrahedra leads to a decrease in the overall cell volume, which results in a reduction in the corresponding crystal plane spacing and thus promotes the improvement of P-O covalency. It was unexpected to observe an amorphous shell layer surrounding the exterior of the NZSP-0.6NSF crystal structure. This phenomenon may be attributed to the presence of additional F and Si in the doped Na₂SiF6. The formation of this amorphous shell layer was found to effectively protect the SSEs structure65,66. Therefore, the amorphous shell layer formed in NZSP-0.6NSF and the enhanced P-O covalency can effectively prevent damage to the SSEs structure during the cycling process.

Therefore, the above experiments provide compelling evidence that NZSP-0.6NSF doped with Na2SiF6 exhibits a pronounced ability to impede the interfacial parasitic side reactions of the electrolyte on metal Na. Moreover, while SnF₂ can also facilitate Na+ ion transport at the interface and reinforce the electrolyte interface, its primary function is to improve the sodium-philic characteristics of the SSE. Conversely, the application of a SnF₂ layer to the Na₂SiF₆-doped NZSP serves to enhance the sodium-philic properties of the SSE, facilitating its bonding with metal Na and thus reducing the interfacial impedance. It can thus be concluded that the NZSP-0.6NSF SSEs, with their enhanced P-O covalency and the SnF2 artificial interfacial layer, can be combined synergistically to achieve stable cycling at high rates.

Effect of doping on the products and kinetics of interphase of solid electrolytes

In light of the preceding discussion, it becomes evident that doping plays a pivotal role in enhancing the stability of SSEs. Consequently, an in-depth examination is conducted to ascertain the impact of the interphase that is formed on the surface on the stability of the SSEs when the metal Na is in direct contact with the SSEs67. Additionally, temperature also influences the growth of interfacial side products and the corresponding changes in reaction kinetics. Initially, impedance tests were conducted on Na|NZSP|Na and Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na symmetric cells at different temperatures (25–75 °C) (Supplementary Fig. 68). It is evident that as the temperature increases, the impedance of both Na|NZSP|Na and Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na decreases with the change in temperature, indicating that an increase in temperature is beneficial for alleviating the formation of side products at the interface. Furthermore, the activation energy of Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na is lower than that of Na|NZSP|Na. This suggests that the SSE doped with Na2SiF6 effectively inhibits the continuous deterioration of the interface due to the enhanced covalency of P-O, leading to the stable formation of interfacial products and ensuring rapid transport of Na+ ions at the interface. Secondly, The CCD tests were conducted on Na|NZSP|Na and Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na symmetric cells at 30 °C, 50 °C, and 70 °C, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 69 and Supplementary Fig. 70). It is evident that the CCDs of both the Na|NZSP|Na and Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na systems exhibit an increase in response to elevated temperatures. Furthermore, the CCD of Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na demonstrates a significantly enhanced rate of increase in comparison to that of Na|NZSP|Na. This further indicates that the SSEs doped with Na₂SiF₆ are capable of resisting interfacial parasitic side reactions at the interface, as well as facilitating rapid Na⁺ ion transport. Furthermore, elevated temperatures facilitate the formation of stable interfacial products at the interface while effectively resisting the formation of Na dendrites. Finally, impedance tests were conducted on Na|NZSP|Na and Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na after Na plating/stripping at varying temperatures (Supplementary Figs. 71 and 72). As anticipated, the impedance of the Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na exhibits minimal variation following Na plating/stripping at disparate temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 73a). In contrast, the impedance of the Na|NZSP|Na exhibits a notable increase following Na plating/stripping at varying temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 73b). It is noteworthy that an increase in temperature serves to mitigate the magnitude of this impedance increase. Furthermore, NZSP-0.6NSF has been demonstrated to effectively inhibit the deterioration of the interface, as a consequence of the enhancement of P-O covalency.

The XPS tests were conducted on the SSE of Na|NZSP|Na and Na|NZSP-0.6NSF|Na after Na plating/stripping at different temperatures to determine the composition of the interphase. In the case of cycled NZSP at 30 °C, the binding energy of Zr is observed to shift towards lower binding energy in the depth-etched spectra of Zr 3d (Supplementary Fig. 74a). Additionally, a conducting ZrSi shoulder peak emerges at the lower binding energy. Furthermore, the Si 2p and P 2p peaks of cycled NZSP exhibit a shift towards lower binding energies (Supplementary Fig. 74b, c). Additionally, the emergence of peaks associated with NaxSiOy, NaxPOy, and NaxP neo-substances can be observed. These findings indicate that a combination of ionic and electronic conductors, comprising NaxSiOy, NaxPOy, and NaxP with ionic conductivity and ZrSi with electronic conductivity, is produced upon direct reaction of NZSP with Na metal. This further suggests that the metallic Na will preferentially react with the PO4 tetrahedra in NZSP, thereby disrupting the structure of the SSEs. However, due to the reaction between NZSP and metallic Na to produce ZrSi with high electronic conductivity, this makes Na dendrites are easy to occur. Furthermore, an additional analysis was conducted on the XPS etching data of cycled-NZSP at 50 °C and 70 °C, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 75 and 76). As with the preceding results, the corresponding Zr 3d, Si 2p, and P 2p are shifted to low binding energies, while simultaneously exhibiting interfacial byproducts with high electronic conductivity of ZrSi and ionic conductivity of NaxSiOy, NaxPOy, and NaxP. Notably, the magnitude of the observed shift of these peaks towards lower binding energies appears to diminish with increasing temperature. This further suggests that an increase in temperature may help to mitigate the deterioration of the interface.