Abstract

Decoding arbitrary polarization information in a cost-effective way is a key target for next-generation optical sensing. However, the design of full-Stokes detectors capable of resolving polarization states in a single shot remains challenging. Here we introduce GOStokes, an approach that leverages heterogeneous grain orientation in solution-processed metal halide semiconductors to extract Stokes parameters in a single measurement. By developing polycrystalline films exhibiting strong inherent circular and linear dichroism, we harness randomly oriented grains to produce varied polarization selectivity across the spatial domain. Integrating these films as multi-channel optical filters with commercial cameras enables real-time polarimetric detection and imaging, each generating a transmission map from a single exposure. Using deep learning, GOStokes precisely determines arbitrary polarization states with an averaged mean absolute error below 1%. Our demonstration underscores the potential of combining low-cost, scalable, polycrystalline films with reconstruction algorithms for advanced polarimetric applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polarization of light is a fundamental property that describes the orientation of electric field vector as the light wave propagates. It plays a crucial role in broad applications ranging from remote sensing, biomedical imaging to quantum computing1,2,3,4. For any optical field, the state of polarization (SoP) can be described by a set of four quantities, known as Stokes parameters \({{{\bf{S}}}}=\left({S}_{0},{S}_{1},{S}_{2},{S}_{3}\right)\), where \({S}_{0}\) represents the total light intensity, \({S}_{1}\) and \({S}_{2}\) describe horizontal/vertical and diagonal linear polarization, respectively, and \({S}_{3}\) describes circular polarization (see Supplementary Note S1 for definitions and equations). Obtaining all Stokes parameters quickly and accurately is essential for these applications, requiring at least four independent measurements with different polarization selectivities. This has been conventionally achieved by mechanically rotating waveplates or polarizers to collect multiple sets of data sequentially over time5. However, this method is time-consuming, not suitable for dynamic or rapidly changing light sources, and the use of free-space optics hinders on-chip integration.

Recent developments in single-shot full-Stokes detection aim to address these limitations by capturing all polarization information in a single measurement6,7,8,9,10,11,12. A key approach utilizes materials or artificial patterns exhibiting linear dichroism (LD) and circular dichroism (CD) to differentiate polarization components, thus enabling full-Stokes parameter reconstruction. Specifically, LD provides contrast between orthogonal linear polarization components (\({S}_{1}\), \({S}_{2}\)), while CD distinguishes between left- and right-circularly polarized light (\({S}_{3}\)), with the accuracy of reconstructed SoP inherently dependent on the polarization selectivity and transmittivity of the optical elements (Supplementary Note S2).

Building on these principles, anisotropic metasurfaces with strong dichroism have been designed and arranged into pixel arrays to enable polarization-sensitive phase and amplitude modulation. This configuration encodes Stokes parameters into distinct intensity patterns, allowing for single-shot polarimetric imaging when integrated with a commercial camera13,14,15,16,17. The implementation of deep learning algorithms has further enhanced performance17,18,19,20, improving accuracy and robustness. More recently, a pioneering study demonstrated that disordered metasurface arrays with weak dichroism offer significant advantages over traditional designs17. While reducing polarization selectivity, this design improves overall transmission efficiency to above 60%, enabling broadband operation across the visible spectrum while maintaining high accuracy. Despite these improvements, metasurface arrays remain fundamentally constrained by material selection and fabrication precision. Manufacturing challenges become particularly pronounced at short wavelengths in the UV and blue regions, where the need for smaller feature sizes increases complexity and cost20.

Solution-processed thin film semiconductors offer new routes for achieving intrinsic structural anisotropy and chirality at the molecular and crystal levels21,22. Metal halide semiconductors (MHS), such as halide perovskites, exhibit large optical anisotropy when reduced in dimensionality and generate chiroptical responses upon integrating chiral organic molecules into their inorganic framework23,24. Unlike metasurface patterns where CD and LD originate from geometric asymmetry and resonance effects, those in MHS arise from crystal symmetry breaking, with their operational wavelength range governed by intrinsic electronic transitions. Leveraging these properties, MHS-based detectors for linearly polarized light (LPL)25,26,27 and circularly polarized light (CPL)28,29,30,31,32 have been each developed. Prior studies have shown that chiral anisotropic MHS single crystals or thin films, such as (R/S-MBA)2PbI4 (MBA = methylbenzylammonium), are sensitive to both types of polarization33,34. Such materials also exhibit the potential for self-powered and chip-integrable polarization detectors35,36, and their anisotropy ratios can be further enhanced through nanopatterning37,38,39. However, all such measurements still rely on time-sequential data acquisition, and full-Stokes detection and imaging in a single shot have yet to be achieved. This underscores the urgent need for innovative strategies that can mitigate these limitations.

In this work, we introduce GOStokes (Grain-Orientation-based Stokes), an approach leveraging heterogeneous grain orientation of chiral MHS thin films for high-accuracy single-shot full-Stokes detection and imaging. This method capitalizes on the polycrystallinity of thin films to achieve a random distribution of LD elements across the spatial domain, facilitating a spatially varied response to polarized light. As a result, the films directly function as multi-channel polarization filters, eliminating the need for additional fabrication steps. By using deep learning algorithms, GOStokes precisely reconstructs the SoP from a single image captured by a commercial camera, enabling high-accuracy polarimetry. This method was demonstrated using solution-processed chiral (R/S-MBA)2CuCl4, which exhibits pronounced optical anisotropy and chirality, and achieved low mean absolute errors (MAEs) of 0.99%, 1.09%, and 0.81% for S1/S0, S2/S0, and S3/S0, respectively, in measurements with spatially invariant polarization. To date, this accuracy stands as the record of any short-wavelength polarimetry in the blue and violet spectra and surpasses that of previous pattern-free methods by an order of magnitude. Furthermore, we developed a polarization imaging system using GOStokes, providing a cost-efficient and rapid sensing platform for full-Stokes polarization detection and imaging.

Results

Linear and circular dichroism of chiral (R/S-MBA)2CuCl4 thin films

The (R/S-MBA)2CuCl4 was used to demonstrate the effectiveness of GOStokes due to its strong optical anisotropy40. The (R/S-MBA)2CuCl4 films were fabricated by spin-coating a precursor solution onto glass substrates, followed by annealing to remove the solvent. Their low-dimensional crystal structure was confirmed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) of both thin films (Supplementary Fig. S1) and single crystals (CCDC 2285418 and 2285357)41, showing structural anisotropy along three crystal axes (Fig. 1a, b). Grazing incidence wide-angle X-ray scattering (GIWAXS) was employed to investigate the crystal orientation, revealing that the c-axis of the grains aligns perpendicular to the substrate, as evidenced by the strong (001) and (002) peaks along the qz axis (Fig. 1c). When light is incident normally to the substrate, linear dichroism can arise due to in-plane structural anisotropy along the a- and b-axes.

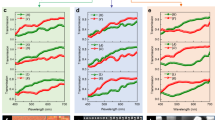

a Schematic diagram of (R/S-MBA)2CuCl4 polycrystalline thin films. b Views of the crystal structure along the a-axis (top) and the b-axis (bottom). c The GIWAXS pattern of (S-MBA)2CuCl4 thin film. d DFT calculated dielectric functions with electric field oscillating along the a-axis (blue) and the b-axis (orange). Solid and dash lines represent the real and imaginary parts of dielectric function, respectively. e Experimental validation of linear dichroism. f TD-DFT calculated excited state properties of a (CuCl4)2− anion. Two major band-to-band transitions (2.85 eV, left; 2.90 eV, right) are included, which correspond to the CD peak at 400 nm. Electron (top) and hole (bottom) density distributions of each transition are depicted in yellow. Electric and magnetic transition dipole moments are labeled. g Experimental CD and h gCD of (R/S-MBA)2CuCl4 thin films.

We therefore analyzed the polarization-dependent optical properties of chiral (R/S-MBA)2CuCl4 through both experiments and ab initio calculations. First, we examined local LD by measuring the transmission of LPL through a small region of uniform crystal orientation, with the incident light’s electric field vector oscillating along the a- and the b-axes of grains (Fig. 1e). The measured dichroic ratio is as high as 2.01 at 406 nm, with an average of 1.81 across 400–450 nm, indicating strong anisotropic absorption. To further understand the origin of this large LD, we evaluated the polarization-dependent absorption coefficient (\(\alpha\)) using the equation:

where \(\omega\) represents angular frequency, \({\varepsilon }_{1}\left(\omega \right)\) and \({\varepsilon }_{2}\left(\omega \right)\) are the real and imaginary parts of the dielectric function, respectively. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations revealed large variations in \({\varepsilon }_{1}\left(\omega \right)\) and \({\varepsilon }_{2}\left(\omega \right)\) in response to the oscillation direction of the electric field vector, demonstrating a clear polarization dependence in α (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Fig. S2a). The excellent agreement between theory and experiment validates the significant LD, which plays a crucial role in resolving the Stokes parameters \({S}_{1}\) and \({S}_{2}\), essential for capturing linear polarization information.

We next investigated the CPL response of the chiral films. A pronounced CD with large dissymmetry factor (\({g}_{{CD}}\) of 10-2 ~ 10−1) was observed below 450 nm, exceeding that typically observed in chiral molecules and lead halide perovskites (10−3-10−4)42. The strong apparent CD arises from a combination of intrinsic CD due to structural chirality and interplay between LD and linear birefringence (LB) (Supplementary Note S3). The reversal of optical chirality when light is incident from opposite sides of the film further confirms the role of LD and LB in modifying the apparent CD (Supplementary Fig. S3). As GOStokes utilizes apparent CD for CPL modulation and \({S}_{3}\) reconstruction, we further elucidated this optical effect through theoretical calculations.

In randomly oriented systems, intrinsic CD arises from the interaction between the electric (\({{{\boldsymbol{\mu }}}}\)) and magnetic (\({{{\boldsymbol{m}}}}\)) transition dipole moments, which is characterized by the dissymmetry factor:

where \({g}_{{CD}}\) is the ratio of differential (\(\Delta A\)) to average (\(A\)) absorbance of left- and right-handed CPL, and \(\theta\) is the angle between \({{{\boldsymbol{\mu }}}}\) and \({{{\bf{m}}}}\). Time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) calculations reveal two key band-to-band transitions at 2.85 eV and 2.90 eV, where \(|{{{\boldsymbol{\mu }}}}|\) and \(|{{{\bf{m}}}}|\) are aligned (\(|\cos \theta |\approx 1\)) and close in magnitude. This leads to an experimentally observed intrinsic CD peak at 375 nm for (R/S-MBA)2CuCl4 (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. S4).

The LB of (R/S-MBA)2CuCl4 originates from differences in the refractive index (\(\Delta n\)) along different crystal axes. This can be expressed as:

where \({\varepsilon }_{a1}\left(\omega \right)\) and \({\varepsilon }_{b1}\left(\omega \right)\) are the real parts of the dielectric function along the a- and b-axes, respectively. The calculated average \(\Delta n\) of 0.033 at 400–450 nm is comparable to commercially available birefringent materials used for quarter-wave plates (QWPs) (Supplementary Fig. S2b). The strong LB, together with LD, enhances the apparent CD observed in these films. Without additional fabrication, the optical anisotropy and chirality of (R/S-MBA)2CuCl4 make it highly promising for full-Stokes detection.

Heterogeneous grain orientation of (R/S-MBA)2CuCl4 thin films

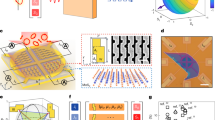

Heterogeneous grain orientation is a fundamental property that GOStokes leverages. The stochastic crystallization process leads to floral-shaped microstructures composed of a large number of needle-like crystalline grains (Fig. 2a). The a-axis of each grain is aligned parallel to the long edges of the needles and varies in orientation within the plane. This heterogeneity causes spatially varied LD effect, as evidenced by our analysis of LPL transmission at three distinct positions (Fig. 2d). We found that the transmittance is different at each location and peaks when the electric field of the LPL aligns with the local a-axis. These observations confirm the presence of multiple LD elements across the space domain. Film thickness variations also play a crucial role in GOStokes. Our analysis shows that thicker films, obtained by increasing the precursor concentration, exhibit stronger LD, which in turn enhances apparent CD (Fig. 2e–h). Due to the notable roughness of (R/S-MBA)2CuCl4 films, with a root mean square (RMS) value of ~10% of the total thickness, thickness variations further modulate the apparent \({g}_{{CD}}\) and LD dichroic ratio across the film (Fig. 2b, c and Supplementary Fig. S5). Combined with spatially varied LD induced by grain orientation, this leads to distinct optical responses across domains, fulfilling the essential requirements for multi-channel optical filtering in single-shot full-Stokes detection (Supplementary Note S2).

a Optical microscopic image of an (S-MBA)2CuCl4 thin film fabricated using a 50 wt% precursor solution. Regions labeled (i)-(iii) display different crystal orientations. Mapping of the CD g-factor (b) and LD dichroic ratio (c) for films fabricated with precursor concentrations of 20 wt%, 30 wt%, and 50 wt%. Scale bar, 1 mm. d LPL angle-dependent transmittance for regions (i)-(iii), demonstrating the varied LD elements across the spatial domain. Averaged film thickness (e) and grain size (f) as a function of precursor concentration, with error bars representing RMS roughness (e) and the standard deviation of grain size (f). CD g-factor (g) and LD dichroic ratio (h) as a function of precursor concentration, with error bars representing their standard deviation within the imaged region. Violin plots show the statistical distribution across the entire imaged region of the film.

To integrate the films into a compact detection system with limited magnification ratio, the grain size should exceed the sensor pixel size to fully utilize the optical anisotropy of each grain. Meanwhile, the floral-shaped microstructure should remain smaller than the sensor format to ensure sufficient coverage of diverse LD elements. By adjusting the precursor concentration, we control the grain and microstructure sizes to meet these criteria. The grain width (along the b-axis) can be tuned from 100 to 102 μm (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. S7), matching the pixel size of various CMOS sensors. Meanwhile, the grain length (along the a-axis) ranges from 10² to 10³ μm, ensuring that the entire microstructure fits within the format size of most imaging sensors. This tunability provides GOStokes with the flexibility to adapt to specific system requirements.

Spatial arrangement of polarization selectivity

To validate our approach for single-shot full-Stokes detection, we investigated the spatial arrangement of polarization selectivity using a chiral (R/S-MBA)2CuCl4 thin film as a multi-channel optical filter. The experimental setup is illustrated in Fig. 3a. Collimated incident light with an arbitrary SoP is generated using an optical system that comprises a halogen lamp, a lens, a bandpass filter, a linear polarizer, and waveplates. The (R/S-MBA)2CuCl4 sample and a black-and-white CMOS camera together form a polarization-sensitive detection system. Each detection involves capturing the transmittance map of the sample film under specific incident polarization condition.

a Experimental setup to examine the spatially varied polarization selectivity. Half wave plate (HWP) and quarter wave plate (QWP) were mounted on rotational motors to generate desired SoPs. The sample and CMOS camera form the detection system. Images taken by the CMOS camera under various incident polarization conditions, including LPL (b, c), CPL (d, e) and elliptically polarized light (f–i). The (S-MBA)2CuCl4 thin film using a 30% precursor was employed in front of the camera. To reduce the image size and enhance signal-to-noise ratio, each image was downscaled to 40 \(\times\) 40 pixels. Dataset wise normalization was applied to each image.

Representative transmittance maps under various SoPs are demonstrated in Fig. 3b–i. We clearly observed that at the single-pixel level, transmittance strongly depends on the SoP due to structural chirality and anisotropy. In addition, at the image scale, the overall pattern varies distinctly due to the heterogeneous orientation of the grains.

Specifically, the spatially varying LD leads to significant variations in LPL response across the space domain, with orthogonal polarizations producing inverse grayscale values (Fig. 3b, c). In contrast, the CD elements, evenly distributed across the entire sensing area, result in a uniform grayscale map under pure CPL incidence, exhibiting clear intensity differences between RH and LH CPL (Fig. 3d, e). Elliptically polarized light, which can be mathematically decomposed to both linear and circular components, also results in varied transmittance maps due to the mixture of CD and LD elements (Fig. 3f–i). These results confirm the feasibility of GOStokes approach for full-Stokes detection, enabling single-shot measurements to capture an array of data with varied polarization selectivity.

Full-Stokes detection enabled by deep learning

Building on these capabilities, we explored the performance of polycrystalline chiral (R/S-MBA)2CuCl4 thin films for full-Stokes detection. This requires collecting transmission maps under known SoPs to build a robust model. To address the high-dimensional maps, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) were employed to extract Stokes parameters (Fig. 4). The neural network consists of three feature extraction blocks, each with a 2D convolution layer and max-pooling layer, followed by three fully connected layers with dropout regularization (Fig. 4a, see Methods for Data Collection and Deep Learning). The output layer provides normalized Stokes parameters (S1/S0, S2/S0, and S3/S0), allowing direct decoding in a single forward pass.

a Schematic diagram of the CNN used to resolve SoPs from images. The input layer is a transmission map, which is downscaled to 40 \(\times\) 40 pixels to reduce the computational cost. The output layer includes three Stokes parameters normalized by incident power. b Polarization states from the output of the CNN data sets plotted on the Poincaré sphere. c Test MAE using different training set sizes. The CNN model significantly outperforms the traditional Mueller matrix method. d Representative demonstration of 20 SoPs randomly selected from the test set. CNN-predicted Stokes parameters were plotted together with their ground truth values. For each Stokes parameter, the averaged MAEs over five independent films is labeled. e Accuracy comparison with previous reports.

We employed gridded SoPs on a Poincaré sphere for training, while the validation and test sets were sampled randomly (Fig. 4b). The incident SoPs were derived from the rotation angles of waveplates, establishing the ground truth for model training and evaluation. The performance was evaluated on the test set using mean absolute errors (MAEs) between the ground truth and predicted values. With sufficient training data, MAE dropped to ~1% for both training and test sets, demonstrating high accuracy.

For comparison, the traditional Mueller matrix method was also used, assuming that each pixel corresponds to a distinct filter channel with its polarization transformation explicitly determined (Supplementary Eqs. (S5) and (S6)). However, its MAE remained high even with a large training set (Fig. 4c), indicating severe underfitting. This suggests that treating each pixel as an independent channel is insufficient, possibly due to anisotropic scattering, whereas CNNs effectively capture hidden correlations to improve prediction accuracy.

Five different films were tested using CNN-based GOStokes. Leveraging its robust data-driven nature, GOStokes adapts to various films and delivers consistent predictions across all input SoPs, achieving superior detection accuracy. The MAEs for S1/S0, S2/S0, and S3/S0 reach 0.99%, 1.09%, and 0.81%, respectively, with standard deviations of 0.17%, 0.14%, and 0.18% among the five films, indicating high reproducibility (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Table S1). The method also demonstrates tolerance to minor beam shifts when trained on a diverse dataset covering various beam profiles (Supplementary Fig. S9). Compared to other methods, our approach achieves an order of magnitude higher accuracy than all detectors without artificial structures and the highest performance for detection wavelengths below 450 nm (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Table S2).

Single-shot full-Stokes polarization imaging

We further demonstrated that GOStokes enables single-shot polarization imaging. To achieve this, an (S-MBA)2CuCl4 film adhered to an optical diffuser was placed at the imaging plane of a focusing lens (Fig. 5a). The image of the object, superimposed with the polarization-dependent pattern induced by the heterogeneous film, was projected onto the diffuser, where the scattered light was captured by a commercial CMOS camera. The captured images were divided into small regions, referred to as super-pixels, each containing \(N\times N\) original pixels and independently processed by a dedicated CNN to extract local Stokes parameters (Supplementary Fig. S10). To train the CNNs, Lens-1 was adjusted to generate a collimated beam with a known, uniform intensity profile on the film. The polarization of the beam was previously described (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. S11a), and raw data collected by the camera was computationally augmented to enable CNNs to resolve arbitrary SoPs (see methods). The choice of super-pixel size influences both accuracy and spatial resolution, with larger sizes improving accuracy at the cost of finer details (Supplementary Fig. S11b–d).

a Schematic of the imaging system. The object is first imaged onto a plane where the (S/R-MBA)2CuCl4 film and diffuser are located. Polarization across the field is resolved by capturing the superimposed image with a commercial camera. b Raw image of a test object captured by the camera, showing distinct patterns of different regions. The inset displays a color photo of the test object, which consists of a linear polarizer (LP) partially overlapped with a QWP. The object transmits LPL in the top right region and CPL in the bottom left. The area in between is blocked by the optical mount. Mappings of the Stokes parameters: c relative S0, d S1/S0, e S2/S0, and f S3/S0.

To validate the functionality of resolving spatially varied SoPs in a single shot, we imaged a linear polarizer partially overlapped with a quarter wave plate (QWP), as shown in Fig. 5b. This test data was not included in the original training set and was processed using a super-pixel size of \(N=20\). The uncovered region in the top right corner transmits LPL, producing a bright area with strong contrast due to heterogeneous LD. In contrast, the QWP-overlapped region converts the light into CPL, resulting in a homogenous appearance in the bottom left. The dark region corresponds to the area covered by the optical mount. Each local SoP was resolved by its trained CNN independently. The extracted Stokes parameter mapping closely matched the spatial SoP distribution, demonstrating the great potential of GOStokes for polarization imaging (Fig. 5c–f). We note that, as a fundamental limitation associated with the use of super-pixels, spatially fast-varying polarization states within a super-pixel region can result in reduced accuracy, such as at sharp boundaries between regions with distinct polarization states, as shown in Fig. 5c–f.

Discussion

This study presents GOStokes, an approach for single-shot full-Stokes detection using polycrystalline MHS thin films with structural anisotropy, chirality, and heterogeneity in grain orientation. Without additional fabrication, the spin-coated films serve as multi-channel optical filters, creating spatially varied polarization selectivity. By employing a deep learning algorithm, we achieved unparalleled detection accuracy for wavelengths below 450 nm, addressing a significant gap in accurate full-Stokes detectors for blue and violet light. Furthermore, our method enables single-shot polarization imaging through flexible and compact system integration.

While this work focuses on chiral MHS samples, GOStokes can be adapted to a broader range of heterogeneous thin films. To highlight its versatility, we also demonstrate the suitability of racemic (MBA)2CuCl4 films—materials lacking intrinsic chirality—for GOStokes measurements. Their strong local apparent CD, arising solely from LD and LB, enabled comparable detection accuracy to their chiral counterparts (Supplementary Fig. S12), further expanding material choices for polarization-sensitive imaging. This work opens up a potential avenue for integrable, accurate, and cost-effective Stokes measurement, poised for broad applications across various sensing systems.

Methods

Preparation of (R/S-MBA)2CuCl4 thin films

(R)-(+)-α-Methylbenzylamine (R-MBA, 99.0%) and (S)-(-)-α-Methylbenzylamine (S-MBA, 98.0%) were bought from TCI. Hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37%), copper oxide (CuO, 99.0%), and N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, 99.8%) were bought from Sigma-Aldrich. All chemicals were used directly without purification. CuO (400 mg) and R/S-MBA (1270 μL) were added to HCl (15 mL) and heated to 120 °C. After all solids were dissolved, the solution was cooled down to room temperature at a rate of 5 °C/h. Centimeter-sized (R/S-MBA)2CuCl4 single crystals were collected, cleaned with filter paper, and dried in vacuum overnight. To prepare polycrystalline thin films, glass substrates were treated by O2 plasma for 15 min. In a N2 glovebox, (R/S-MBA)2CuCl4 single crystals were dissolved in DMF with different weight ratios. The solution was filtered and spin-coated onto a glass substrate at 3000 rpm for 30 s, followed by annealing at 60 °C for 10 min and 100 °C for 30 min.

Materials characterizations

The XRD data of thin films were collected at out-of-plane direction using a Rigaku SmartLab powder diffractometer with Cu Kα. LD measurements were carried out using a PerkinElmer LAMBDA 1050 + UV/Vis/NIR spectrophotometer with additional linear polarizer. CD spectra were measured using an Applied Photophysics Chirascan spectrometer. For apparent CD, the films were positioned directly facing the incident beam. The intrinsic CD was obtained by averaging the spectra recorded from the front and the back of the films. CD and LD mapping data were collected using a home-built setup, as illustrated in Fig. 3a. Film thickness was measured by a Zygo Nexview 3D optical profiler. GIWAXS measurements were conducted at Advanced Light Source (ALS), Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA at beamline 7.3.343. The samples were placed in a He-filled compartment during the measurements. Data were acquired at an incidence angle of 0.25° with a hard X-ray energy of 10 keV. The 2-D data were recorded with a Pilatus 2 M detector with a pixel size of 172 um and placed at a distance of about 280 mm from the samples. The scattering data were analyzed using a custom Nika package for Igor Pro (Wavemetrics Inc.).

Resolving SoPs

To extract the SoPs using Mueller calculus, we assume a training set of N images, each containing K pixels. Each row of \({{{{\bf{Y}}}}}_{{{{\rm{train}}}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N\times 4}\) is a Stokes vector corresponding to a known SoP in the training set. The first row of the Mueller matrix for pixel \(i\) is donoted as \({{{\bf{M}}}}(i)\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{4}\). The vector \({{{{\bf{X}}}}}_{{{{\rm{train}}}}}\left(i\right)\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N}\) represents the value of pixel \(i\) in training set. Each \({{{\bf{M}}}}(i)\) is obtained by minimizing \({{||}{{{{\bf{Y}}}}}_{{{{\rm{train}}}}}{{{\bf{M}}}}\left(i\right)-{{{{\bf{X}}}}}_{{train}}\left(i\right){||}}_{2}\), resulting in \({{{\bf{M}}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{K\times 4}\). During detection, for a test image \({{{{\bf{X}}}}}_{{{{\rm{test}}}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N}\), the target SoP \({{{{\bf{Y}}}}}_{{{{\rm{test}}}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{4}\) is solved by minimizing \({{||}{{{\bf{M}}}}{{{{\bf{Y}}}}}_{{{{\rm{test}}}}}-{{{{\bf{X}}}}}_{{{{\rm{test}}}}}{||}}_{2}\).

Inspired by classical architectures44,45, we built a CNN featuring three alternating layers of 2D convolution and max-pooling, followed by three fully connected layers designed to resolve SoPs from images. A dropout layer with a rate of 0.1% was added after the last max-pooling layer to mitigate overfitting. The CNN takes \({{{{\bf{X}}}}}_{{{{\rm{train}}}}}\left(j\right)\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N}\) as input, where \(j\) represents the index of a training image. The output has three channels representing S1/S0, S2/S0, and S3/S0. We chose an equally weighted mean square error (MSE) loss across the three output channels, and performed dataset-wise normalization prior to training. The 2.72 × 106 trainable parameters in the CNN were optimized by an Adam optimizer46 with a learning rate of 1.0 × 10−3 for 10,000 epochs. For each epoch, the training set was shuffled and evenly divided into two batches. All programming was conducted in PyTorch (version 2.0.1) and executed on a Nvidia RTX 2060 GPU with 6 GB memory. Each experiment takes less than five minutes in our computational environment.

Full-Stokes imaging

The imaging system contains a light source, an objective lens, a sample film, a diffuser, a commercial lens set and a CMOS camera. A superfrost slide from Electron Microscopy Sciences was used as the diffusor in the imaging system. A cover glass coated with (S-MBA)2CuCl4 film was tapped tightly on the frosted side of the diffusor. The light source of the system is a Thorlabs SOLIS-415C LED. Images were captured off-axis using the camera (Allied Vision Alvium 1800 U-234) to avoid light that directly passes through the diffusor.

To train models for imaging, dataset augmentation was applied using the transformation \({{{{\bf{X}}}}}_{{ijk}}^{{{{\rm{aug}}}}}={r}_{{ijk}}{{{{\bf{X}}}}}_{{ij}}^{{{{\rm{ori}}}}},{{{{\bf{Y}}}}}_{{ijk}}^{{{{\rm{aug}}}}}=[{r}_{{ijk}}{y}_{{0}_{{ij}}},{y}_{{1}_{{ij}}},{y}_{{2}_{{ij}}},{y}_{{3}_{{ij}}}]\), where \({X}_{{ij}}^{{ori}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N\times N}\) represents the original image of i-th super-pixel (\(i\in [0,H\times V)\)) with the j-th SoP, and \([{y}_{{0}_{{ij}}},{y}_{{1}_{{ij}}},{y}_{{2}_{{ij}}},{y}_{{3}_{{ij}}}]\) is its corresponding SoP. The random scaling factor \({r}_{{ijk}}{\mathbb{\in }}{\mathbb{R}}\) is introduced to generate the k-th augmented image (\({{{{\bf{X}}}}}_{{ijk}}^{{{{\rm{aug}}}}}\)) and its associated SoP (\({{{{\bf{Y}}}}}_{{ijk}}^{{{{\rm{aug}}}}}\)). In our demonstration, 1200 raw datapoints were collected (\(j\in [{{\mathrm{0,1200}}})\)), \(H=V=45\), \(N=20\). Each datapoint was augmented ten times (\(k\in [{{\mathrm{0,10}}})\)). Additionally, 120 dark data points containing noise were also added to the dataset. The training, validation and test sets contain 10100, 1010, and 1010 samples, respectively.

Data availability

All characterization and machine learning datasets are available at the GOStokes repository at Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1517528147.

Code availability

All custom code used to train models, resolve SoPs, and full-Stokes imaging is available at https://github.com/michaelge233/GOStokes/, under the Apache 2.0 License.

References

Arun, G. & Mishra, V. A review on quantum computing and communication. In 2014 2nd international conference on emerging technology trends in electronics, communication and networking 1–5 https://doi.org/10.1109/ET2ECN.2014.7044953 (2014).

He, C. et al. Polarisation optics for biomedical and clinical applications: a review. Light Sci. Appl. 10, 194 (2021).

Rubin, N. A. et al. Matrix Fourier optics enables a compact full-Stokes polarization camera. Science 365, eaax1839 (2019).

Stenflo, J. O. Solar magnetic fields as revealed by Stokes polarimetry. Astron. Astrophys. Rev. 21, 1–58 (2013).

Azzam, R. M. Stokes-vector and Mueller-matrix polarimetry. JOSA A 33, 1396–1408 (2016).

Zhang, S. et al. Dynamic display of full-Stokes vectorial holography based on metasurfaces. ACS Photonics 8, 1746–1753 (2021).

Zhang, X., Liu, L., Li, Y., Ning, T. & Zhao, Z. High-accuracy reconstruction of Stokes vectors via spatially modulated polarimetry using deep learning at low light field. Appl. Opt. 62, 9009–9017 (2023).

Fan, Y. et al. Dispersion-assisted high-dimensional photodetector. Nature 630, 77–83 (2024).

Singh, K., Tabebordbar, N., Forbes, A. & Dudley, A. Digital Stokes polarimetry and its application to structured light: tutorial. JOSA A 37, C33–C44 (2020).

Fang, C., Li, J., Zhou, B. & Li, D. Self-powered filterless on-chip full-Stokes polarimeter. Nano Lett. 21, 6156–6162 (2021).

Ma, C. et al. Intelligent infrared sensing enabled by tunable moiré quantum geometry. Nature 604, 266–272 (2022).

Dai, M. et al. On-chip mid-infrared photothermoelectric detectors for full-Stokes detection. Nat. Commun. 13, 4560 (2022).

Xian, S. et al. Highly precise and broadband full-Stokes polarimeter based on a deep learning algorithm. ACS Photonics 10, 2432–2439 (2023).

Shen, S., Li, S., Yuan, Y. & Tan, H. High-efficiency broadband achromatic metalenses for visible full-Stokes polarization imaging. Opt. Express 31, 28611–28623 (2023).

Ren, Y. et al. Full-Stokes polarimetry for visible light enabled by an all-dielectric metasurface. Adv. Photonics Res. 3, 2100373 (2022).

Zuo, J. et al. Chip-integrated metasurface full-Stokes polarimetric imaging sensor. Light Sci. Appl. 12, 218 (2023).

Fan, Q. et al. Disordered metasurface enabled single-shot full-Stokes polarization imaging leveraging weak dichroism. Nat. Commun. 14, 7180 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. Real-time machine learning–enhanced hyperspectro-polarimetric imaging via an encoding metasurface. Sci. Adv. 10, eadp5192 (2024).

Chen, C. et al. Neural network assisted high-spatial-resolution polarimetry with non-interleaved chiral metasurfaces. Light Sci. Appl. 12, 288 (2023).

Zhang, C. et al. Low-loss metasurface optics down to the deep ultraviolet region. Light Sci. Appl. 9, 55 (2020).

Long, G. et al. Chiral-perovskite optoelectronics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 423–439 (2020).

Ma, J., Wang, H. & Li, D. Recent progress of chiral perovskites: materials, synthesis, and properties. Adv. Mater. 33, 2008785 (2021).

Lu, H., Vardeny, Z. V. & Beard, M. C. Control of light, spin and charge with chiral metal halide semiconductors. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 470–485 (2022).

Dou, Y. et al. Broadband achromatic quarter-waveplate using 2D hybrid copper halide single crystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 18007–18014 (2023).

Han, Z. et al. Oriented perovskite growth regulation enables sensitive broadband detection and imaging of polarized photons covering 300–1050 nm. Adv. Mater. 33, 2003852 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Intrinsic strong linear dichroism of multilayered 2D hybrid perovskite crystals toward highly polarized-sensitive photodetection. Adv. Opt. Mater. 7, 1901049 (2019).

Li, M. et al. Minute-scale rapid crystallization of a highly dichroic 2D hybrid perovskite crystal toward efficient polarization-sensitive photodetector. Adv. Opt. Mater. 8, 2000149 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. A chiral reduced-dimension perovskite for an efficient flexible circularly polarized light photodetector. Angew. Chem. 132, 6504–6512 (2020).

Ishii, A. & Miyasaka, T. Direct detection of circular polarized light in helical 1D perovskite-based photodiode. Sci. Adv. 6, eabd3274 (2020).

Chen, C. et al. Circularly polarized light detection using chiral hybrid perovskite. Nat. Commun. 10, 1927 (2019).

Li, D. et al. Chiral lead-free hybrid perovskites for self-powered circularly polarized light detection. Angew. Chem. 133, 8496–8499 (2021).

Maiti, A. & Pal, A. J. Spin-selective charge transport in lead-free chiral perovskites: the key towards high-anisotropy in circularly-polarized light detection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202214161 (2022).

Ma, J., Fang, C., Liang, L., Wang, H. & Li, D. Full-Stokes polarimeter based on chiral perovskites with chirality and large optical anisotropy. Small 17, 2103855 (2021).

Chen, Q. et al. Uniaxial-oriented chiral perovskite for flexible full-Stokes polarimeter. Adv. Mater. 36, 2400493 (2024).

Bai, J. et al. Wafer-scale patterning integration of chiral 3D perovskite single crystals toward high-performance full-Stokes polarimeter. J. Am. Chem. Soc. jacs.4c06822 https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.4c06822 (2024).

Chen, Q. et al. Manipulating perovskite structural asymmetry for high-performing self-powered full-Stokes polarimetry. Sci. Adv. 11, eads6123 (2025).

Zhao, Y. et al. Chiral 2D-perovskite nanowires for Stokes photodetectors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 8437–8445 (2021).

Zhao, Y. et al. Chiral 2D/Quasi-2D perovskite heterojunction nanowire arrays for high-performance full-Stokes polarization detection. Adv. Opt. Mater. 11, 2301239 (2023).

Wang, C., Li, G., Dai, Z., Tian, W. & Li, L. Patterned chiral perovskite film for self-driven Stokes photodetectors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2316265 (2024).

Hao, J. et al. Direct detection of circularly polarized light using chiral copper chloride–carbon nanotube heterostructures. ACS Nano 15, 7608–7617 (2021).

Das, R. et al. Family of chiral ferroelectric compounds with widely tunable band gaps. Chem. Mater. 36, 1891–1898 (2024).

Li, J.-K. et al. B,N-embedded double hetero[7]helicenes with strong chiroptical responses in the visible light region. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 17958–17963 (2021).

Hexemer, A. et al. A SAXS/WAXS/GISAXS beamline with multilayer monochromator. J. Phys. 247, 012007 (2010).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In Advances in neural information processing systems (eds. Pereira, F., Burges, C. J., Bottou, L. & Weinberger, K. Q.) vol. 25 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2012).

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1409.1556ArXiv14091556 (2014).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: a methed for stochastic optimization. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations (San Diego, CA, USA, 2015).

Ge, M. et al. GOStokes. Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.15175281 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Award Number 2415101 and the Packard Fellowships for Science and Engineering. GIWAXS data measurements at NCSU was supported by NCSU Goodnight Dist. Professorship Endowment. GIWAXS data were acquired at the beamline BL 7.3.3. of the Advanced Light Source, which is supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC02-05CH11231. Eric Schaible (BL7.3.3, ALS) is gratefully acknowledged for beamline maintenance as well as assistance with GIWAXS experiments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.G. and M.L. conceived the idea of this study. M.G. designed the experiment, conducted the DFT simulation, developed the detection system and the deep learning algorithm. Y.Y. designed and developed the imaging system. T.W. assisted in coding for dataset collection and optical measurements. S.M. and H.A. carried out the GIWAXS measurements. M.G. and M.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Yidong Hou and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ge, M., Yao, Y., Wang, T. et al. Accurate single-shot full-Stokes detection enabled by heterogeneous grain orientations in polycrystalline films. Nat Commun 16, 5603 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60914-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60914-y