Abstract

Plasma-electrochemical tandem conversion with NOx− as intermediates promises a route for renewable ammonia (NH3) synthesis from air and water. However, a critical challenge lies in developing electrolyzers capable of operating efficiently at large current densities. Here, we present a scalable membrane electrode assembly electrolyzer with a full runner design (MEA-FR) that achieves efficient NH3 production at industrial current densities. Compared to conventional serpentine runner configuration, MEA-FR leveraging forced convection within porous electrodes achieves three-order-of-magnitude enhancement in NOx− mass transfer flux. This design, meanwhile, generates strong shear forces across the porous electrode, promoting rapid detachment of O2 bubbles at the anode and reducing overpotential losses. Notably, MEA-FR exhibits a high Faradaic efficiency of 91.8 ± 1.4% for NH3 synthesis at 500 mA cm−2, significantly outperforming the serpentine runner counterparts (64.9 ± 1.1%). Furthermore, a scaled-up 4 × 25 cm2 MEA-FR stack with four modular cells is assembled with rotationally symmetric bipolar plates, delivering high NOx− conversion efficiency (>95%), high Faradaic efficiency (>91%), and long-term stability (>200 h) under industrial-relevant current densities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electrochemical ammonia (NH3) synthesis from air and water as nitrogen and proton sources, mediated by NOx− intermediates, represents a compelling sustainable pathway for green NH3 production1,2,3,4,5,6. This approach begins when non-thermal plasma (NTP) activates atmospheric N2 and O2 to form NOx species, which are transformed into NOx− before undergoing electrochemical reduction to NH37. Such a pathway aligns with intermittent renewable electricity sources, facilitating decentralized, on-demand NH3 supply8,9. However, scaling this technology suffers from inefficiencies in the electrochemical NOx− reduction reaction (eNOx−RR), particularly at the current densities demanded by industrial applications10,11. While catalyst innovation has been accelerated, electrolyzer design—the critical framework determining system performance—remains significantly underdeveloped12.

Membrane electrode assembly (MEA) electrolyzers stand out as the most promising architecture for eNOx−RR due to their zero-gap configuration and minimal ohmic losses13,14,15,16. Despite the remarkable progress in NH3 synthesis via MEA electrolyzers enabled by nanostructured porous electrodes, commercial-scale implementation remains hindered by limited operational stability and severe hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) under industrially relevant current densities17,18. A key limiting factor is the serpentine runner design of the MEA electrolyzers, which makes it difficult to regulate the homogeneity of the reactive species within the electrode, resulting in performance degradation and failure19. In particular, in three-dimensional porous electrodes, due to the lateral mass transfer resistance generated by its skeleton, it is difficult for the reactive species to transfer uniformly and efficiently from the serpentine runner side to the ion exchange membrane side13. In addition, while anion exchange membrane exhibits undesirable NOx− crossover, alternative implementations of proton exchange membrane (PEM) or bipolar membrane (BPM) inadvertently acidify the cathode-membrane interface through proton migration, enhancing HER and accelerating catalyst degradation17,20,21. Simultaneously, sluggish O2 bubble detachment during anodic oxygen evolution reaction (OER) leads to active site blockage and ionic pathway obstruction, increasing ohmic overpotential and concentration polarization, especially at large current densities22,23,24. Addressing these challenges demands a holistic redesign of flow fields, membrane-electrode interfaces, and bubble management protocols.

Recent efforts to resolve these limitations reveal persistent compromises. PEM-free flow-through reactors leveraging anodic O2 for NH3 stripping enhance NO3− recovery efficiency but introduce safety concerns from O2/NH3/H2 mixtures alongside energy losses through NH3 oxidation25. Similarly, inserting a porous solid electrolyte layer between cation exchange membranes partially suppresses HER through selective Na+ transport but fails to overcome NO3− mass transfer limitations at elevated current densities13. Although surface modifications26, micro-nano structuring27,28, and external fields29 can enhance O2 bubble management, scaling these fine-tuning approaches significantly increases system complexity and capital costs.

Here, we present an MEA electrolyzer with a full runner design (MEA-FR) that achieves efficient NH3 synthesis at industrial current densities with low cell voltages. The full runner design introduces forced convection within the porous electrode by pumping electrolytes through its inherent interconnected pores, which serve as integrated flow channels. This “two birds with one stone” strategy not only breaks the mass transfer limitations of NOx− within the porous cathode encountered in traditional MEA electrolyzers with serpentine runner design (MEA-SR), increasing the NOx− mass transfer flux by three orders of magnitude but also induces strong shear forces over the catalyst surface, promoting early detachment of O2 bubbles and reducing overpotential losses. Techno-economic assessment (TEA) shows that the eNOx−RR process is more feasible using the MEA-FR than conventional MEA-SR. Furthermore, the concept of our MEA-FR was extended to a realistic, scalable electrolyzer stack through a rotationally symmetric bipolar plate design. Notably, a scaled-up 4 × 25 cm2 MEA-FR stack delivers 40.8 A with a stack voltage of 10 V, achieving a high NH3 Faradaic efficiency (FE) of 92.6%. When coupled with NTP-assisted air activation, the MEA-FR stack achieves massive NH3 production with high NOx− conversion efficiency and NH3 FE, highlighting its potential for practical NH3 synthesis.

Results

MEA-FR electrolyzer design

Current research predominantly employs the MEA-SR with serpentine runner configuration (Fig. 1a) for evaluating eNOx−RR performance of porous electrodes under continuous operation15,30,31. This widely adopted design features serpentine flow channels machined into conductive current collectors (e.g., titanium or graphite plates), a standard architecture in CO2 reduction electrolyzers and fuel cells32,33,34,35. Unlike gas-phase reactions where gas reactants flow in serpentine channels, in the liquid-solid eNOx−RR system, NOx−-containing electrolyte traverses serpentine flow paths. Within the MEA-SR, the electrolyte adopts a flow-by pattern, primarily moving over the porous electrode surface. In the MEA-FR featuring a full runner design, we replace complex serpentine channels with a streamlined square slot to mechanically confine the electrode (Fig. 1b). The electrode is firmly sandwiched between the chamber walls and the separator membrane, compelling electrolyte permeation through the electrode’s intrinsic interconnected porous network in a flow-through pattern. We further demonstrated the scalability of the full runner concept through a bipolar plate featuring a rotationally symmetric dual full runner design (Fig. 1c), enabling straightforward stack assembly via modular titanium bipolar plate-bridged cell units.

Optimization of electrolyte flow

To investigate how different flow architectures influence the reaction environment in porous electrodes, we performed COMSOL simulations for single electrolyzer with 25 cm2 electrode geometric area (refer to more details in Supplementary Fig. 1). Comparative analysis reveals distinct transport mechanisms between the two designs: in MEA-SR, bulk electrolyte flows parallel to the electrode surface (Fig. 2a), whereas in MEA-FR, electrolyte is forced through the electrode’s interconnected pores (Fig. 2b). The flow velocity component in the effective mass transfer direction (\({v}_{x}\)) for both configurations under equivalent inlet flow rates is shown in Fig. 2c, d and Supplementary Fig. 2. MEA-SR exhibits steep velocity gradient, with \({v}_{x}\) peaking near the electrolyte-electrode interface and rapidly decaying across the electrode cross-section. This induces non-uniform mass transfer—faster at the outer electrode region near the electrolyte and substantially slower at the inner electrode region near the membrane. In contrast, MEA-FR demonstrates a markedly uniform distribution of \({v}_{x}\), enabling efficient mass transfer throughout the entire electrode. Importantly, MEA-FR delivers \({v}_{x}\) approximately three orders of magnitude higher than that in MEA-SR, emphasizing the impact of flow field design on mass transfer performance. We then simulated electrochemical reactions within the electrode using NO3− as a representative reactant. Figure 2e, f and Supplementary Fig. 3 illustrate the NO3− concentration distribution across the electrode from the electrolyte-cathode interface to the cathode-membrane interface in both configurations. The conventional MEA-SR exhibits a pronounced concentration gradient, with NO3− levels decreasing along the electrode cross-section. This results in depleted NO3− concentrations throughout most of the electrode volume away from the electrolyte-cathode interface, a consequence of the limited mass transfer caused by low \({v}_{x}\) in the electrode interior. In sharp contrast, MEA-FR maintains consistently high NO3− concentrations throughout the electrode due to enhanced mass transfer, indicating significantly improved conditions for eNOx−RR.

a, b Schematic illustrations of MEA-SR (a) and MEA-FR (b). c, d 2D distribution of the computed velocity components in the effective mass transfer direction across the electrode cross-section using MEA-SR (c) and MEA-FR (d). e, f NO3− concentration distribution within the porous electrode in MEA-SR (e) and MEA-FR (f). g, h Shear force distribution on cross-sectional plane of the porous electrode in MEA-SR (g) and MEA-FR (h).

Shear force plays a fundamental role in bubble removal dynamics by altering the forces acting on bubbles36. To reduce overpotentials associated with sluggish kinetics of O2 bubbles removal, introducing high shear forces over the catalyst surface is essential. Figure 2g, h and Supplementary Fig. 4 present the shear force distribution across electrode cross-sections in both designs. MEA-SR exhibits negligible shear force throughout the electrode, severely impairing bubble detachment efficiency. Conversely, MEA-FR generates a strong shear force, about three orders of magnitude higher than MEA-SR, at regions near the membrane and current collector. Even at mid-electrode regions that show moderate shear forces, they still surpass MEA-SR’s maximum shear force by two orders of magnitude, ensuring effective bubble evacuation across the entire electrode architecture.

Simulation results comparing thinner (1 mm) and thicker (2 mm) electrodes indicate that reducing electrode thickness mitigates mass transport heterogeneity within the MEA-SR (Supplementary Fig. 5). However, as electrode thickness increases, the detrimental effects of lateral mass transfer resistance become increasingly significant (Supplementary Fig. 6). In contrast, MEA-FR exhibits uniformly distributed and efficient mass transfer and strong shear force across the electrode, regardless of electrode thickness (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8). These findings collectively highlight that mass transport in MEA-SR is jointly constrained by both the intrinsic lateral mass transfer resistance of the electrode and the electrolyte flow-by pattern. Notably, the reconfigured flow regime in MEA-FR effectively overcomes these limitations, eliminating lateral transport bottlenecks and enabling markedly enhanced mass transfer performance.

Analysis of mass transfer mechanisms further clarifies the performance differences between these designs. In electrochemical reaction systems, mass transfer occurs through three mechanisms: diffusion driven by concentration differences, ionic electromigration driven by potential differences, and forced convection driven by external forces. In MEA-SR, the effective mass transfer direction of NOx− is from the electrolyte-electrode interface to the electrode-membrane interface. As illustrated in Fig. 2a, due to the more positive electrical potential and lower NOx− concentration at the electrode-membrane interface compared to the electrolyte-electrode interface, the directions of electromigration and diffusion align with the effective mass transfer direction, whereas convection occurs perpendicularly as electrolyte flows in the serpentine runner. Consequently, the more efficient convection mass transfer cannot contribute effectively to reactant transport. In MEA-FR, however, electrolyte flow within the electrode ensures all mass transfer mechanisms contribute cooperatively to the overall NOx− transport.

In general, the NOx− mass transfer process near the electrode is described using Nernst-Planck equation37. With excess supporting electrolyte (e.g., 1 M KOH) in eNOx−RR, ion electromigration becomes neglected, leaving concentration diffusion and forced convection are the dominant processes affecting the mass transfer flux38. For both electrolyzers, NOx− mass transfer near the electrode can be expressed by Eq. (1):

where \({J}_{{{{NO}}_{x}}^{-}}\) represents the mass transfer flux of NOx−, \({D}_{{{{NO}}_{x}}^{-}}\) is the diffusion coefficient, \(\frac{{\partial c}_{{{{NO}}_{x}}^{-},{x}}}{\partial x}\) is the NOx− concentration gradient, and \({c}_{{{{NO}}_{x}}^{-}}\) is the NOx− concentration. As shown in Fig. 2c, d, the \({v}_{x}\) value in MEA-FR exceed those in MEA-SR by three orders of magnitude, largely increasing the convective contribution (\({v}_{x}{c}_{{{{NO}}_{x}}^{-}}\)) to the mass transfer flux. In addition, the higher \({v}_{x}\) increases the Reynolds number (Re) (Eq. (2)), which, in turn, reduces the thickness of the concentration boundary layer (δc, Eq. (3)). Furthermore, \({\partial c}_{{{{NO}}_{x}}^{-},x}\) is greater in MEA-FR than in MEA-SR due to the higher NOx− concentration within the porous electrode, resulting in a steeper concentration gradient within the concentration boundary layer in MEA-FR, thereby enhancing NOx− mass transfer through concentration diffusion. Consequently, the NOx− mass transfer flux in the MEA-FR is three orders of magnitude higher than in the MEA-SR, demonstrating its capacity to overcome mass transport limitations under high current density conditions.

Electrochemical eNOx −RR performance evaluation

To evaluate the MEA-FR design at industrially relevant conditions, we construct test electrolyzers with an electrode area of 25 cm2 for direct comparison with conventional MEA-SR configurations (Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10). For optimal electrochemical performance, we prepared Co nanowires-decorated Co foam as the cathode based on their established excellent NH3 selectivity and long-term stability39,40, paired with NiFeOx nanosheets-deposited Ni foam anode that provides rapid OER kinetics in alkaline environments to reduce reaction overpotential41,42. Electrode structure and composition were characterized by several microscopy and spectroscopy techniques (Supplementary Figs. 11–14). We incorporated BPM that effectively prevented ionic species crossover between cathodic and anodic chambers (Supplementary Fig. 15)43, while employing single-pass flow operation to ensure consistent feeding of NOx− concentration.

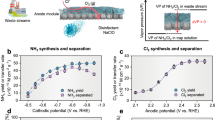

After optimizing flow parameters to balance reactant delivery and residence time (Supplementary Figs. 16 and 17), we conducted comparative performance evaluations using 0.1 M NO3−. At all tested current densities (Fig. 3a), MEA-FR exhibits consistently lower cell voltage than the conventional MEA-SR design, with the performance difference becoming more pronounced at higher operational current densities. Performance divergence between the two configurations was particularly evident in product selectivity measurements (Fig. 3b), where MEA-SR showed progressive deterioration of NH3 FE from 88.5 ± 0.4% at 100 mA cm−2 to 54.6 ± 1.4% at 600 mA cm−2 due to intensified competition between eNO3−RR and HER. This phenomenon also aligns with previous MEA studies under low NO3− concentrations and high current densities13,17. In contrast, the MEA-FR design maintains a superior NH3 FE of 91.8 ± 1.4% at 500 mA cm−2 and 89.0 ± 1.6% at 600 mA cm−2. This superior performance extended to eNO2−RR as well, where MEA-FR achieved 92.8 ± 1.0% NH3 FE at 500 mA cm−2 compared to only 67.7 ± 1.0% for MEA-SR under identical conditions (Supplementary Fig. 18). To assess operational adaptability, we further investigated MEA-FR performance across a wide range of NO3− concentrations. Figure 3c reveals the interrelationship between current density and reactant concentration, with mass transport limitations at low NO3− concentrations (< 0.1 M) and high current densities (>300 mA cm−2). However, MEA-FR maintained NH3 FE > 82.0% even at dilute feedstocks (500 ppm NO3−), a significant advantage for variable nitrogen sources (Supplementary Figs. 19–23).

a Comparison of cell voltage of different combinations at varied current densities. All voltages are reported without iR correction. b FE of NH3, NO2−, and H2 versus current density with 1 M KOH containing 0.1 M NO3− as influent. c Current density-depended NH3 FE with different concentrations of NO3− as influent using MEA-FR. d FE of products versus current density under 0.1 M KOH. e Monitored O2 evolution in MEA-SR (up) and MEA-FR (down) under a current density of 500 mA cm−2. f Comparison of cost per kg of NH3 production using MEA-SR and MEA-FR under different current densities. g Schematic of reaction mechanism within the MEA-FR design. The error bars represent the standard deviation from three independent measurements. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

For practical implementation, we evaluated batch processing performance using electrolyte recirculation to maximize NOx− conversion. Leveraging the relationship between optimal current densities and NO3− concentrations, we implemented a step-current chronopotentiometry (CP) profile during batch NO3− conversion tests (Supplementary Table 1)15. By adjusting the current density at different intervals corresponding to different levels of NO3− conversion, MEA-FR achieved a high NO3− conversion efficiency of 98.2% (25.2 μg mL−1 NO3−-N remaining) and an NH3 FE of 86% when processing 1 L of 0.1 M NO3− (1400 μg mL−1 NO3−-N) (Supplementary Fig. 24). In contrast, constant-current operation at 500 mA cm−2 over MEA-FR yielded lower performance (94.7% conversion, 74.2 μg mL−1 residual NO3−-N, 67.8% NH3 FE) after 2 h of electrolysis (Supplementary Fig. 25). Comparative testing with MEA-SR under identical conditions demonstrated its fundamental limitations, achieving only 37.5% NH3 FE with 444.6 μg mL−1 NO3−-N remaining in the catholyte over a 3 h constant-current operation (Supplementary Fig. 26). In addition, long-term operational stability was confirmed through an extended 90-hour test comprising six consecutive 15 h batch experiments with MEA-FR using 5 L of 0.1 M NO3− as circulating catholyte (Supplementary Fig. 27 and Supplementary Table 2). At the tenth hour over each batch cycle, the average NO3− conversion efficiency reached 99%, and the average NH3 FE reached 90%. This stability demonstrates the robust nature of the MEA-FR design under extended operation, though we observed that while prolonging reaction time could marginally increase NO3− conversion, simultaneously, enhanced competitive HER will occur, reducing the overall NH3 FE.

The lateral mass transfer resistance inherent to porous electrodes limits the application of thicker electrodes in MEA-SR for achieving higher reaction currents. Increasing cathode thickness exacerbates intra-electrode mass transport limitations, thereby intensifying HER dominance in thicker electrodes (Supplementary Fig. 28). In contrast, MEA-FR overcomes this constraint by enabling uniform and efficient mass transport throughout the entire electrode architecture, achieving consistently high-efficiency NH3 synthesis across varying cathode thicknesses. This finding aligns precisely with prior simulation results, validating the capability of MEA-FR to decouple eNOx−RR performance from lateral mass transfer resistance constraints. To mitigate the impact of mass transfer limitations in MEA-SR, electrolyzer performance under high NO3− concentration of 1 M was evaluated (Supplementary Fig. 29). At lower current densities (<400 mA cm−2), MEA-SR exhibits negligible mass transfer limitations, achieving FE for NH3 production exceeding 92%. However, as current density further increases, lateral mass transfer resistance in MEA-SR becomes pronounced, reducing NH3 FE to 70.6% at 1 A cm−2. With superior mass transport capabilities, MEA-FR electrolyzer consistently delivers superior NH3 FE, maintaining 94.9% even at 1 A cm−2. Moreover, we investigated the influence of local pH by varying electrolyte alkalinity. In MEA-SR, proton migration from the BPM creates a local environment with reduced pH at the cathode-membrane interface that favors HER over eNO3−RR. This effect intensifies in less alkaline media (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 30), with HER dramatically increasing in 0.1 M KOH electrolyte containing 0.1 M NO3−. Even under these challenging conditions, MEA-FR maintained substantially higher NH3 FE than MEA-SR, demonstrating that its architecture effectively counteracts localized acidification through enhanced mass transport.

To investigate the factors underlying the lower cell voltage in the MEA-FR design, we examined various electrolyte flow pattern combinations (Supplementary Fig. 31). The cathode chamber with serpentine runner coupled with the anode chamber with full runner was designated as SRc-FRa, and the cathode chamber with full runner coupled with the anode chamber with serpentine runner as FRc-SRa. The J-E curves for SRc-FRa and FRc-SRa closely resemble those for MEA-FR and MEA-SR, respectively (Fig. 3a), highlighting the critical role of full runner design at the anode side in reducing the overpotential of MEA-FR. To further visualize the flow behavior, we used transparent polymethyl methacrylate flow panels to observe the electrolyte flow at the anode side (Supplementary Fig. 32). As shown in Fig. 3e, high-speed camera shots reveal distinct differences in O2 bubble evolution behavior. In MEA-SR, insufficient shear forces allow bubbles to adhere to the electrode surface, growing substantially before eventual detaching into serpentine channels. As current density increases, these O2 bubbles progressively obstruct electrolyte flow paths, block active catalytic sites, and create barriers to ionic transport (Supplementary Fig. 33 and Supplementary Movie 1–6). The resulting mass transport and charge transfer limitations significantly increase anode overpotential, further offsetting the beneficial increase in reaction sites afforded by thicker electrodes (Supplementary Fig. 34). MEA-FR, by contrast, generates strong shear forces that promote immediate bubble detachment and rapid evacuation from the electrode surface, maintaining optimal interfacial contact between electrolyte and catalyst regardless of operating current and anode thickness (Supplementary Figs. 34, 35 and Supplementary Movie 7–12).

Further investigation of operating parameters demonstrated a clear inverse relationship between flow rate and cell voltage across all electrolyzer designs (Supplementary Fig. 36). This correlation confirms that higher shear forces generated at increased flow rates directly contribute to reduced overpotential losses through enhanced bubble management. We also examined the influence of electrolyte alkalinity, finding that OER kinetics depend significantly on the mass transfer of OH−, with cell voltage increasing substantially in dilute (0.1 M) KOH and decreasing in concentrated (3 M) KOH environments (Supplementary Fig. 37). MEA-FR demonstrates enhanced cell performance in a wide OH− concentration range, highlighting the crucial role of reinforced mass transfer and early detachment of O2 bubbles within MEA-FR in reducing overpotential losses.

To further elucidate the mass transport enhancement enabled by electrolyte permeation through porous electrodes, we evaluated a hybrid flow regime in an interdigitated runner electrolyzer (Supplementary Fig. 38). In this configuration, the electrolyte adopts a flow-by pattern along the channels analogous to serpentine runner, while simultaneously penetrating the electrode’s porous matrix between adjacent channels via flow-through pattern akin to the full runner architecture. The interdigitated runner electrolyzer demonstrated intermediate eNOx−RR performance—surpassing MEA-SR but underperforming MEA-FR—which conclusively demonstrates that introducing forced convection within the electrode significantly enhances mass transport and thereby elevates NH3 synthesis efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 39).

Based on the electrochemical performance of our MEA-FR design, we conducted a comprehensive TEA to assess its economic viability for industrial implementation (Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Table 3)13,44. It should be noted that to highlight the influence of the electrolyzer, only eNO3−RR process is considered in our TEA. MEA-SR achieves minimum production costs of 1.69 US$ per kg NH3 at 200 mA cm−2, but this increases to 2.52 US$ per kg NH3 at 600 mA cm−2 due to reduced energy efficiency from intensified HER (Fig. 3f). This economic penalty at higher current densities renders conventional MEA-SR fundamentally unsuitable for high-throughput industrial operation. In contrast, MEA-FR maintains nearly constant production costs across a wide current density range, rising only marginally from 1.36 to 1.47 US$ per kg NH3 as current density rises from 300 to 600 mA cm−2. While these costs remain slightly higher than the current market price of NH3 from the Haber-Bosch process (1.15 US$ per kg), they compare favorably with existing NO3− removal costs in wastewater treatment plants (about 3.82 US$ per kg NH3)45,46. Single-variable sensitivity analysis identified electricity price, cell voltage, and current density as the most influential parameters affecting production costs (Supplementary Fig. 40 and Supplementary Tables 4, 5), highlighting critical areas for future research aimed at lowering production costs. With projected renewable electricity cost reductions and further improvements in catalyst design and membrane technology, MEA-FR-based eNO3−RR has clear potential to achieve costs below 1.15 US$ per kg NH3 (Supplementary Fig. 41)47.

Based on our comprehensive simulation and performance analysis, we propose mechanistic models for the eNOx−RR mechanism in MEA-FR and MEA-SR. In conventional MEA-SR, two distinct but interrelated phenomena limit performance: lateral mass transfer resistance causes NOx− depletion zones within the electrode, while simultaneous inward proton flux from the BPM generates localized acidification at the cathode-membrane interface. These conditions synergistically promote HER over eNOx−RR at high current densities. Concurrently at the anode, insufficient shear forces permit O2 bubbles to adhere and grow on catalytic surfaces, blocking active sites and increasing overpotential losses (Supplementary Fig. 42). By comparison, MEA-FR resolves these limitations through its integrated flow architecture. Convection-enhanced mass transfer ensures uniform distribution of high concentration NOx− throughout the electrode while facilitating efficient proton consumption, maintaining stably alkaline conditions at the cathode-membrane interface that suppress HER. Simultaneously, precisely controlled shear forces at the anode promote immediate O2 bubble detachment, preserving active catalytic areas and minimizing overpotential losses (Fig. 3g). This combination of enhancements enables MEA-FR to maintain superior performance across the broad operating window required for industrial implementation.

Scaled-up MEA-FR stack performance evaluation

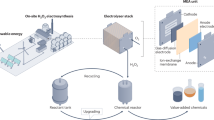

An efficient and stable electrolyzer stack is crucial for the large-scale industrial implementation of eNOx−RR. We integrated our full runner concept into a scalable stack architecture using a rotationally symmetric bipolar plate design. The detailed structures of current collectors, bipolar plates, and gaskets are presented in Supplementary Figs. 43 and 44. In the MEA-FR stack configuration, electrolyte flows in parallel through each cell’s porous electrodes, ensuring uniform reaction conditions across all units (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 45). This parallel flow approach is critical for maintaining consistent performance, as serial flow would create progressively decreasing NOx− concentration in downstream cells, leading to increased HER and reduced overall efficiency. From an electrical perspective, the cells are connected in series (i.e., the same current flows through them) to increase the integration of the MEA-FR stack, with bipolar plates conducting electrons from anodic OER to cathodic eNOx−RR, completing the entire circuit (Supplementary Fig. 46)48. We constructed and evaluated a 4 × 25 cm2 MEA-FR stack with four modular units (total electrode area of 100 cm2, Fig. 4b and Supplementary Figs. 47–49). The applied stack voltage distributed nearly equally among the four cells (Fig. 4c), confirming their uniform resistance and reaction environments. At 10 V stack voltage, the total electrolysis current reaches 40.8 A, corresponding to approximately 2.5 V per cell, which is consistent with single-cell performance. The MEA-FR stack achieves an impressive NH3 FE of 99.2% at 8 V and remained over 89% FE under a total current of 54.4 A at 11 V (Fig. 4d). In addition, long-term stability testing over 200 h through multiple batch cycles demonstrated consistent performance, with NH3 FE exceeding 87% at the end of each cycle (Fig. 4e). Post-operation examination confirmed the structural integrity of both cathode and anode materials (Supplementary Figs. 50, 51). These results confirm that the MEA-FR stack is highly effective for eNOx−RR at industrially relevant current densities, offering high selectivity and operational stability.

a The distribution and parallel flow of electrolytes in the MEA-FR electrolyzer stack. b Photographs of a 4 × 25 cm2 MEA-FR electrolyzer stack with four modular units. c Stack voltage-dependent voltage distribution and total electrolysis current. Cx represents the cell and the cell’s respective number. 1 M KOH solutions with or without 0.1 M NO3− were used under single-pass flow operation as catholyte and anolyte, respectively. d NH3 FE at different stack voltages. e The total electrolysis current and NH3 FE for a stability test at a 9 V stack voltage. Each cycle starts with 40 L of 1 M KOH containing 0.1 M NO3− as the catholyte and 3 M KOH as the anolyte. All voltages are reported without iR correction. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Tandem NH3 synthesis from air using the plasma-MEA-FR stack coupling

After validating the superior performance of the MEA-FR stack in eNOx−RR, we extended its application to a plasma-assisted air-to-NH3 synthesis system (Fig. 5a). This integrated approach follows a three-step relay conversion process: NTP-assisted air activation, chemical conversion, and electrochemical reduction. We employed a spark discharge NTP for atmospheric nitrogen activation, with optimization details available in our previous work2. The generated NOx species undergo chemical conversion with OH− in alkaline solution, forming NO2− and NO3− that serve as feedstock for the MEA-FR stack, completing the “air → NOx → NOx− → NH3” transformation pathway (Fig. 5b). After 20 h of operation with four spark discharge plasma units, a total of 0.096 mol L−1 NO2− and 0.0029 mol L−1 NO3− were collected in an 8 L absorption solution of 1 M KOH (Fig. 5c). For the electrochemical conversion stage (NOx− → NH3), we implemented a step-current CP protocol to maximize energy efficiency (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Table 6). As shown in Fig. 5b, the MEA-FR stack achieved NOx− conversion efficiency of 95.3% with an NH3 FE of 91.7% after 5 h of electrolysis. These results demonstrate the practical viability of the MEA-FR electrolyzer stack for distributed NH3 synthesis from air, water, and renewable electricity.

a Schematic of the tandem NH3 synthesis route using air and water. b Photograph of MEA-FR stack operation. c NH3 FE and concentration changes of NO2−, NO3−, and NH3 in a batch experiment. d Stack voltage profile under a step-current CP operation. All voltages are reported without iR correction. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In summary, we achieve two birds with one stone using a full runner design that addresses the significant challenges of slow and uneven mass transfer, severe HER, and substantial overpotential losses typically encountered in conventional MEA-SR for eNOx−RR under practical current densities. Through electrolyte flow engineering, our MEA-FR facilitates efficient mass transfer within the porous electrode, effectively mitigating concentration gradients and promoting the rapid renewal of the reactive microenvironment. This protocol is capable of handling electrolytes across various NOx− concentration levels, demonstrating high NH3 FE at practical current densities. Moreover, the strong shear forces induced by the MEA-FR configuration facilitate the early detachment of O2 bubbles, thereby reducing overpotential losses. Experimentally informed TEA further highlights the substantial role of the MEA-FR design in reducing the cost of NH3 synthesis, while identifying key parameters for further optimization. Notably, the MEA-FR design offers enhanced manufacturability and seamless scalability, making it an attractive option for large-scale assembly. With a rotationally symmetric bipolar plate design, the 4 × 25 cm2 MEA-FR stack showcases long-term operation stability, high NOx− conversion efficiency, and high NH3 FE under elevated operating currents. By successfully bridging the gap between laboratory-scale research and practical application, our findings establish a strong foundation for the commercialization of technologies of eNOx−RR. Furthermore, this concept offers a novel platform for investigating the intrinsic performance of porous electrodes, with potential applications extending to other electrochemical processes involving gas evolution and mass transfer limitations.

Methods

Chemicals

Cobalt nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO3)2·6H2O, 99.99%), ammonium fluoride (NH4F, AR), and potassium nitrite (KNO2, 97%) were purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Potassium nitrate (KNO3, AR), urea (CO(NH2)2, AR), potassium hydroxide (KOH, AR), nickel nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO3)2⋅6H2O, ≥ 98%), ferric nitrate nonahydrate (Fe(NO3)3⋅9H2O, 98.5%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 96%), hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37%), and ethanol (AR) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Salicylic acid (AR, 99.5%), sodium citrate dihydrate (AR, 99.0%), and sodium nitroprusside (AR, 99.0%) were purchased from Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Cobalt foam (99.9%) and nickel foam (99.9%) were purchased from Suzhou Keshenghe Metal Materials Co., Ltd.

Electrode synthesis

The cobalt foam (CF, 5 × 5 cm2) was sequentially cleaned ultrasonically in ethanol, 1 M HCl, and ultrapure water for 10 min each. The Co(OH)F nanowire arrays (NWAs) were synthesized via a hydrothermal method43. The well-cleaned CF was immersed in a 120 mL aqueous solution containing 8 mmol Co(NO3)2⋅6H2O, 40 mmol CO(NH2)2, and 32 mmol NH4F within a 250 mL Teflon-lined autoclave. After heating at 120 °C for 8 h, the Co(OH)F NWAs/CF electrode was withdrawn and cleaned ultrasonically with ultrapure water for 1 min to remove weakly attached Co(OH)F nanowires. The Co NWAs/CF electrode was obtained through a radio frequency plasma-enabled low-temperature reduction process. The plasma treatment system was first evacuated to a pressure of 5 Pa, and then a 10% H2/Ar mixed gas was introduced at a gas rate of 30 mL min−1 until the pressure stabilized at 30 Pa. The plasma power was set to 100 W, and the treatment time was 1 h. After the system was completely cooled, the Co NWAs/CF electrode was removed and stored in a vacuum.

For the preparation of anode, NiFeOx catalyst was electrodeposited on nickel foam (NF, 5 × 5 cm2) with a three-electrode setup on an electrochemical workstation (CS310X, Wuhan CorrTest Instrument Co. Ltd.)41. The procedure for cleaning NF is the same as that for CF described above. 25 cm2 of NF and carbon paper were used as the working and counter electrodes, respectively. The NiFeOx/NF electrode was obtained by electrodeposition at − 1 V vs. Ag/AgCl for 300 s in an electrolyte of 3 mM Fe(NO3)3⋅9H2O and 3 mM Ni(NO3)2⋅6H2O. The NiFeOx/NF electrode was rinsed with water several times and dried in an oven.

Characterization

Scanning electron microscopy was conducted on a MALA3 LMH field emission scanning electron microscopy. High-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy was performed on a Talos F200X Lorenz transmission electron microscope. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy was conducted on a Thermo Fisher ESCALAB Xi + X-ray photoelectron spectrometer. All the XPS spectra were calibrated by shifting the peak of C 1 s to 284.8 eV. Ion chromatography was performed with a DIONEX INTEGRION ion chromatography.

Electrolyzer structures

Co NWAs/CF and NiFeOx/NF electrodes with a thickness of 1.5 mm were fabricated as the cathode and anode, respectively, each with a geometric area of 25 cm2. To investigate thickness-dependent effects, additional electrodes with thicknesses of 1.0 mm and 2.0 mm were tested. The BPM (Fumasep FBM-PK, 6 × 6 cm2, 110–160 μm) was used to prevent the crossover of reactants (NO3− and NO2−) and potassium species. BPM was stored in 1 M NaCl solution with 1 wt% Na2SO3 before use. In MEA-SR, the serpentine flow channel on the titanium current collector plate was 3 mm wide, 3 mm deep, and 50 mm long. Two silicone gaskets with 1.5 mm thickness and a 25 cm2 window were applied to prevent electrolyte leakage. In MEA-FR, the slot depth on the titanium current collector plate was 1 mm, and the thickness of the silicone gasket used was 0.5 mm. For the 4 × 25 cm2 MEA-FR electrolyzer stack, the electrolyte inlet and outlet diameters are 6 mm. The slots on both sides of the titanium bipolar plate have a depth of 1 mm, with 0.5 mm sealing gaskets.

Electrochemical measurement

All the electrochemical measurements on MEA-SR and MEA-FR electrolyzers were conducted under ambient conditions. An adjustable direct current regulated power source (eTOMMENS, eTM-1560P) was used to provide two-electrode full-cell voltage to the electrolyzer. CP tests with controlled current were conducted while voltages were recorded. Samples of the effluent were collected for later component analysis. The flow rate of electrolytes was controlled using peristaltic pumps. 1 M KOH aqueous solution and 1 M KOH with different concentrations of NO3− were flowed as anolyte and catholyte, respectively. Due to the dissolution of KOH in water releases a large amount of heat, the prepared electrolyte must be cooled to room temperature (25 ± 1 °C) before use. In the complete NO3− conversion batch experiments, 1 L of 1 M KOH solution with an initial NO3− concentration of 0.1 M (pH 13.91 ± 0.04, equal to 1400 μg mL−1 NO3−-N) was used as catholyte. The electrolyte in the catholyte storage bottle was sampled at specific intervals to quantify the products. Step-current CP tests were performed by changing the input current at a given time. The long-term stability test of MEA-FR was conducted by treating 5 L of 1 M KOH solution with 0.1 M NO3− under step-current operation, with each cycle tested for 15 h and a total of 6 cycles. Regarding the eNO3−RR test for the 4 × 25 cm2 MEA-FR electrolyzer stack, the electrolyte flow rates were set to four times the optimized flow rates for a single MEA-FR electrolyzer. In the long-term stability test for the MEA-FR electrolyzer stack, electrolyte tanks of 40 L were used with an electrolyte flow rate of 400 mL min−1. The experiment was stopped every 25 h, and the electrolyte refreshed. To maintain an alkaline environment at the anode, the concentration of KOH in the anolyte was 3 M.

The NTP-assisted tandem NH3 synthesis system was constructed on the basis of our previously published report2. In brief, air was pumped into the spark discharge NTP that generated by a high voltage power supply (HB-C06, Foshan Hongba Electronics Co., Ltd, China), which was driven by a manual contracting voltage regulator (TDGC2-0.5KVA, Zhejiang Chengqiang Electric Co., Ltd, China). To accelerate the accumulation of NOx− in the alkaline absorption solution, we connected four spark discharge NTP units in parallel. Each NTP operated at an air flow rate of 120 sccm, with the activated air being introduced into 8 L of 1 M KOH absorption solution. After 20 h, the resulting absorption solution was used as the electrolyte and fed into the MEA-FR electrolyzer stack. Peristaltic pumps were used to circulate the electrolyte between the MEA-FR electrolyzer stack and the storage tank.

Product quantification

The concentration of NH3 was detected via the indophenol blue method. For testing, a 2 mL sample was mixed with 2 mL of 1 M NaOH solution containing 5 wt% salicylic acid and 5 wt% sodium citrate, 1 mL of 0.05 M NaClO and 0.2 mL of 1 wt% sodium nitroprusside. The mixture was allowed to incubate for 2 h at room temperature. The intensity of the color correlates with NH3 concentration, which can be quantified by measuring the absorbance at 655 nm using a spectrophotometer and comparing it to a calibration curve of known NH3 concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 52).

The concentration of NO2− and NO3− was detected using ion chromatography. The calibration curve was obtained by fitting a series of plots regarding peak area and corresponding NO2−/NO3− concentration (Supplementary Fig. 53). The NO2− and NO3− concentrations were determined based on the measured peak area and the calibration curve.

In order to detect the generated H2, the Ar carrier gas flow controlled by the mass flow meter was introduced into the catholyte storage tank. The mixed gas in the storage tank was then passed into the acid washing bottle to remove the volatilized NH3, and finally the mixed gas was discharged into the gas chromatograph (SP3420, Beifen-Ruili). The H2 concentration was quantified by the thermal conductivity detector.

FE calculation

In a single-pass conversion experiment, the FE is a variable independent of the operation time determined by the current density and flow rate. The NH3 FE was calculated by

where C is the NH3 concentration, v is the flow rate of catholyte, n is the electron transfer number, which is 8 for NH3 production and 6 for NO2− production, F is the Faraday constant (96,485 C mol−1), J is current density, and A is the electrode area.

While in the batch tests, the NH3 FE was calculated by

where V is the catholyte volume, t is the electrolysis time.

For NTP-assisted tandem NH3 synthesis, the NH3 FE was calculated by

where C1 and C2 were calculated by

The FE of H2 production was calculated by

where v is the mole flow rate of H2, n is the electron transfer number, which is 2 for H2.

Simulation details

The corresponding physical model was constructed based on the real electrolyzer structure and geometric dimensions. The physical model is meshed by the built-in meshing module in COMSOL V6.1. A three-dimensional steady-state model, which includes bulk fluid flow, species transport and reaction, has been developed to discuss the underlying reasons for improved reaction performance of the designed MEA-FR electrolyzer. Detailed simulation parameters and boundary conditions are listed in Supplementary Tables 7, 8. Two assumptions were applied in the numerical simulation. First, the reaction rates therein are time-averaged values calculated from experimental results, i.e., the time dependence of the electrode reactions before reaching the steady state is neglected. Second, the metal foam electrodes used for the experiments are described through the porous medium domain and are considered to be isotropic. Therefore, the governing equations are summarized below.

The steady state laminar model is used to describe the bulk fluid flow in the computational domain, with the mass and momentum conservation equations shown in Eqs. (10) and (11):

where ρ is the density of the mobile phase, u is the velocity vector, p is the pressure, I is the identity tensor, K is the viscous force tensor, F is the volume force vector, and ρg is the gravitational volume force.

The mass and momentum conservation equations used to describe the fluid flow within the porous electrodes are shown in Eqs. (12) and (13), respectively:

where Qm is the mass source; εp and κ are the porosity and permeability of the porous electrode; μ is the dynamic viscosity of the electrolyte; β is the inertial drag coefficient of non-Darcy flow, and it can be calculated by

where cF is the Forchheimer dimensionless parameter.

The mass transfer process of species i in the entire computational domain is controlled by

where N is the total flux; R represents the formation or consumption rate of the corresponding species, which is determined through experiments. The flux of species i in the electrolyte is represented by the Nernst-Planck equation:

where the three terms on the right side represent the diffusion process driven by the concentration gradient, the electro-migration process driven by the potential gradient, and the forced convection process driven by the external force, respectively.

Data availability

The data supporting the plots within this paper and other study findings are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided in this paper.

References

Ge, X. et al. Controlling the reaction pathways of mixed NOxHy reactants in plasma-electrochemical ammonia synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 35305–35312 (2024).

Liu, W. et al. Efficient ammonia synthesis from the air using tandem non-thermal plasma and electrocatalysis at ambient conditions. Nat. Commun. 15, 3524 (2024).

Meng, Z. et al. Efficient ammonia production beginning from enhanced air activation. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2202105 (2022).

Sun, J. et al. A hybrid plasma electrocatalytic process for sustainable ammonia production. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 865–872 (2021).

Li, L. et al. Efficient nitrogen fixation to ammonia through integration of plasma oxidation with electrocatalytic reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 14131–14137 (2021).

Meng, S.-L. et al. Cobaloxime: selective nitrite reduction catalysts for tandem ammonia synthesis. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 1590–1596 (2023).

Ren, Y. et al. Strategies to activate inert nitrogen molecules for efficient ammonia electrosynthesis: current status, challenges, and perspectives. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 2776–2805 (2022).

Winter, L. R. & Chen, J. G. N2 fixation by plasma-activated processes. Joule 5, 300–315 (2021).

Ren, Y. et al. Microscopic-level insights into the mechanism of enhanced NH3 synthesis in plasma-enabled cascade N2 oxidation-electroreduction system. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 10193–10200 (2022).

Liu, H., Bai, L., Bergmann, A., Cuenya, B. R. & Luo, J. Electrocatalytic reduction of nitrogen oxide species to ammonia. Chem 10, 2963–2986 (2024).

Xu, H., Ma, Y., Chen, J., Zhang, W. X. & Yang, J. Electrocatalytic reduction of nitrate - a step towards a sustainable nitrogen cycle. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 2710–2758 (2022).

Zhang, H. et al. Unveiling cutting‐edge developments in electrocatalytic nitrate‐to‐ammonia conversion. Adv. Mater. 36, 2312746 (2024).

Chen, F.-Y., Elgazzar, A., Pecaut, S. & Qiu, C. Electrochemical nitrate reduction to ammonia with cation shuttling in a solid electrolyte reactor. Nat. Catal. 7, 1032–1043 (2024).

Hao, S. et al. Improving the operational stability of electrochemical CO2 reduction reaction via salt precipitation understanding and management. Nat. Energy 10, 266–277 (2025).

Zhang, B. et al. Defect-induced triple synergistic modulation in copper for superior electrochemical ammonia production across broad nitrate concentrations. Nat. Commun. 15, 2816 (2024).

Wang, K. et al. Intentional corrosion-induced reconstruction of defective NiFe layered double hydroxide boosts electrocatalytic nitrate reduction to ammonia. Nat. Water 1, 1068–1078 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Proton exchange membrane electrode assembly for ammonia electrosynthesis from nitrate. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 6, 5067–5073 (2023).

Hu, Q. et al. Ammonia electrosynthesis from nitrate using a ruthenium–copper cocatalyst system: A full concentration range study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 668–676 (2024).

Wen, G. et al. Continuous CO2 electrolysis using a CO2 exsolution-induced flow cell. Nat. Energy 7, 978–988 (2022).

Ahmadi, M. & Nazemi, M. Understanding potential losses and pH distribution in the electrochemical nitrate reduction reaction to ammonia. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 63, 9315–9328 (2024).

Speck, F. D. & Cherevko, S. Electrochemical copper dissolution: A benchmark for stable CO2 reduction on copper electrocatalysts. Electrochem. Commun. 115, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elecom.2020.106739 (2020).

Angulo, A., van der Linde, P., Gardeniers, H., Modestino, M. & Fernández Rivas, D. Influence of bubbles on the energy conversion efficiency of electrochemical reactors. Joule 4, 555–579 (2020).

Leistra, J. A. & Sides, P. J. Voltage components at gas evolving electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 134, 2442 (1987).

Vogt, H. The quantities affecting the bubble coverage of gas-evolving electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 235, 495–499 (2017).

Zhang, G. et al. Ammonia recovery from nitrate-rich wastewater using a membrane-free electrochemical system. Nat. Sustain. 7, 1251–1263 (2024).

Xu, W., Lu, Z., Sun, X., Jiang, L. & Duan, X. Superwetting electrodes for gas-involving electrocatalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 1590–1598 (2018).

Kim, Y. J. et al. Highly efficient oxygen evolution reaction via facile bubble transport realized by three-dimensionally stack-printed catalysts. Nat. Commun. 11, 4921 (2020).

Li, M., Xie, P., Yu, L., Luo, L. & Sun, X. Bubble engineering on micro-/nanostructured electrodes for water splitting. ACS Nano 17, 23299–23316 (2023).

Matsushima, H., Kiuchi, D. & Fukunaka, Y. Measurement of dissolved hydrogen supersaturation during water electrolysis in a magnetic field. Electrochim. Acta 54, 5858–5862 (2009).

Boppella, R., Ahmadi, M., Arndt, B. M., Lustig, D. R. & Nazemi, M. Pulsed electrolysis in membrane electrode assembly architecture for enhanced electrochemical nitrate reduction reaction to ammonia. ACS Catal. 14, 18223–18236 (2024).

Huang, P. W. et al. Impact of local microenvironments on the selectivity of electrocatalytic nitrate reduction in a BPM‐MEA system. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2304202 (2024).

Wakerley, D. et al. Gas diffusion electrodes, reactor designs and key metrics of low-temperature CO2 electrolysers. Nat. Energy 7, 130–143 (2022).

Lees, E. W., Mowbray, B. A. W., Parlane, F. G. L. & Berlinguette, C. P. Gas diffusion electrodes and membranes for CO2 reduction electrolysers. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 55–64 (2021).

Fan, J. et al. Bridging the gap between highly active oxygen reduction reaction catalysts and effective catalyst layers for proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Nat. Energy 6, 475–486 (2021).

Yuan, S. et al. Flow field design matters for high current density zero-gap CO2 electrolyzers. ACS Energy Lett. 9, 5945–5954 (2024).

Blackmore, B., Li, D. & Gao, J. Detachment of bubbles in slit microchannels by shearing flow. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 241, 514–520 (2001).

Lv, Y. et al. Mass transfer and electrochemical behavior of nitrate reduction to ammonia in electrocatalytic flow cell reactor. AIChE J. 70, e18262 (2023).

Bard, A. J. & Faulkner, L. R. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications 2nd Edition. (2001).

Deng, X., Yang, Y., Wang, L., Fu, X. Z. & Luo, J. L. Metallic Co nanoarray catalyzes selective NH3 production from electrochemical nitrate reduction at current densities exceeding 2 A cm−2. Adv. Sci. 8, 2004523 (2021).

Yang, K. et al. Unveiling the reaction mechanism of nitrate reduction to ammonia over cobalt-based electrocatalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 12976–12983 (2024).

Lu, X. & Zhao, C. Electrodeposition of hierarchically structured three-dimensional nickel–iron electrodes for efficient oxygen evolution at high current densities. Nat. Commun. 6, 6616 (2015).

Crandall, B. S. et al. Kilowatt-scale tandem CO2 electrolysis for enhanced acetate and ethylene production. Nat. Chem. Eng. 1, 421–429 (2024).

Xu, Z. et al. Continuous ammonia electrosynthesis using physically interlocked bipolar membrane at 1000 mA cm−2. Nat. Commun. 14, 1619 (2023).

Shin, H., Hansen, K. U. & Jiao, F. Techno-economic assessment of low-temperature carbon dioxide electrolysis. Nat. Sustain. 4, 911–919 (2021).

Schnitkey, G., Paulson, N., Zulauf, C. & Baltz, J. Fertilizer prices and company profits going into spring 2023. Farmdoc Daily https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2023/02/fertilizer-prices-and-company-profits-going-into-spring-2023 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Sustainable waste-nitrogen upcycling enabled by low-concentration nitrate electrodialysis and high-performance ammonia electrosynthesis. EES Catal. 1, 504–515 (2023).

Bond, K., Butler-Sloss, S., Lovins, A., Speelman, L., & Topping, N. X-change: Electricity—On track for net zero. https://rmi.org/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2023/07/rmi_x_change_electricity_2023.pdf (2023).

Endrődi, B. et al. Multilayer electrolyzer stack converts carbon dioxide to gas products at high pressure with high efficiency. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 1770–1777 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2020YFA0710000, G.D.Y.), the Joint Funds of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U22A20391, G.D.Y.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22302154, H.H.O.), the Key Projects in Shaanxi Province (2024CY2-GJHX-75, H.L.; 2023GXLH-004, CXY-2022-148, G.D.Y.), the Innovation Capability Support Program of Shaanxi (2023-CX-TD-26, G.D.Y.), the Project funded by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2024M762605, X.L.R.), the Program of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities (B23025, G.D.Y.), the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (GZC20232093, X.L.R.) and the high-level innovation and entrepreneurship talent project of Qinchuangyuan (No. QCYRCXM-2023-98, H.H.O.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.L. designed the MEA-FR electrolyzer and stack, synthesized and characterized the electrode materials, performed electrolyzer testing, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. Y.L. (the second author) performed COMSOL simulations. J.Q.Z. and X.L.R. participated in electrolyzer performance testing. Y.X.R. and M.Y.X. characterized the electrodes. H.H.O., Y.L. (the seventh author), H.L., and H.G.H. reviewed and revised the manuscript. G.D.Y. contributed significantly to the analysis of the data, supervision of the project, manuscript preparation, and funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jianan Gao, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, W., Lv, Y., Ou, H. et al. Full runner electrolyzer stack for industrial-current-density NOx−-mediated ammonia synthesis from air and water. Nat Commun 16, 5716 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61069-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61069-6

This article is cited by

-

Flow-synchronized ring-shaped electrochemical ion pumping for redox-free desalination without terminal electrodes

Nature Chemical Engineering (2025)