Abstract

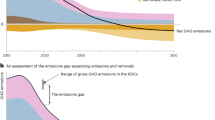

Scenarios for reaching net-zero and other climate policy goals are increasingly featuring widespread adoption of novel carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies. However, these technologies currently represent only a small fraction of total CDR and may face various barriers to large-scale deployment. What are the consequences of planning for levels of CDR today that may differ from those realized in the future? Here, we combine decision analysis and a global integrated assessment model (GCAM) to quantify the climate, technology, economic, and equity outcomes of planning for high or low CDR adoption under uncertainty. We find that planning for high CDR under a 2 °C target leads to minimal fossil fuel phase-out before mid-century. If large-scale CDR is not feasible, the rapid transition required after mid-century increases global stranded assets by 38%. A robust policy strategy that plans for low CDR opens up the possibility to limit end-of-century temperature change to 1.5 °C.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the window to avert the most severe impacts of climate change is rapidly shrinking, the urgency of taking steps to dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions is becoming increasingly apparent1. Actors at different levels of government2 — and increasingly in the private sector3,4 — are making commitments to reach net-zero or net-negative carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and limit global warming to 1.5 °C or well below 2 °C this century, as set out in the Paris Agreement5. Integrated assessment models (IAMs) are widely used to explore pathways for meeting these goals due to their broad systems coverage and long history in climate assessment and policymaking6. Scenarios that are consistent with the Paris goals show steep reductions in CO2 emissions across all sectors of the economy7 and, increasingly, widespread adoption of approaches to capture CO2 from the atmosphere and durably store it, referred to collectively as carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies8.

There are many potential CDR technologies with varying costs and levels of experience. The two novel technologies (i.e., not including conventional land use change and forestry9) that are most widely represented in models are bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) and, more recently, direct air carbon capture and storage (DACCS), although interest in other technologies is growing10,11. BECCS produces useful energy from biomass and captures the resulting CO2 emissions12. DACCS uses chemical processes to capture CO2 from ambient air13. The captured CO2 can then be durably stored (e.g., in underground geologic formations). Novel CDR technologies including BECCS and especially DACCS have seen growing interest from policymakers and the private sector4,14. However, these technologies are in the early stages of adoption, and thus their future role in the global economy is highly uncertain15,16.

A variety of factors may limit the build-out of CDR at a climate-relevant scale. Given their novelty, costs of CDR approaches such as BECCS and DACCS are highly uncertain9,17 but generally exceed the $100/tCO2 target recommended for economical deployment18,19. At scale, CDR may also place pressure on global land and water systems and require large energy and material inputs20,21,22. The risks of large-scale BECCS and other land-based CDR approaches have been particularly emphasized given their potential to increase food and water scarcity23. Additionally, large-scale geologic CO2 storage, while technically feasible24,25, may be socially and politically infeasible26,27. More broadly, social and political constraints may limit the scale-up of CDR and can vary depending on the particular CDR method and community needs and perspectives28,29. Some have also raised concerns about whether planning for CDR presents a moral hazard and risks deterring other climate action30,31,32. Even if rapid scale-up is feasible, CDR may have negative side effects that make high CDR futures less desirable17,33.

Despite these concerns, there have also been major advancements in CDR technologies. Innovation by start-ups and advanced market commitments have created niche markets to enable technologies to improve and scale4. Experience with other technologies34 suggests that a variety of factors may be important in driving future CDR adoption, including characteristics of the technologies themselves (e.g., modularity) and their use environments (e.g., public support and supply- and demand-side policies)35,36. With this in mind, policy analysis37 and bottom-up modeling suggest that a high-effort, “emergency”38 deployment scenario could reach CDR levels currently featured in some IAMs. Recent literature has also explored governance approaches for effectively reducing emissions while equitably allocating CDR responsibilities at local, national, and international levels39,40,41. These studies suggest that CDR can enable more ambitious and potentially more fair climate commitments, but a “fair-share” approach would require a large scale-up of current commitments by major emitters42,43.

Given these uncertainties, it is important to understand how planning for CDR today will affect whether and how we can meet climate goals in the future. Previous research has used IAMs to explore how constraints on CDR affect the timing and portfolio of emissions reductions under various climate policies14,44. Limits on growth rates can increase policy costs or even make ambitious targets infeasible, especially if multiple technologies are constrained, whereas a larger portfolio of CDR options can reduce costs10,45. Other research has used stochastic dynamic programming to explore how uncertainty in future CDR deployment through 2030 affects optimal mitigation policies in this decade, showing that accounting for this uncertainty leads to a need for more rapid emissions reductions46,47. One of these studies also calculates the global policy costs for a set of scenarios that plan for different future levels of CDR47, building on prior studies exploring similar questions using stylized emissions reduction scenarios44.

Here, we investigate the climate, technology, economic, and equity impacts of relying on uncertain CDR technologies. Our approach combines decision analysis and a state-of-the-art IAM (the Global Change Analysis Model, GCAM) to simulate a two-stage decision problem with six illustrative scenarios representing different approaches to climate policy and feasible adoption levels of CDR. We substantially expand on prior research in this area in three ways. First, we explore scenarios where uncertainty in CDR may not be resolved until mid-century, consistent with planning horizons featured in many long-term country strategies and net-zero commitments. Second, we quantify a wide range of regional and global outcomes for our scenarios, building on previous studies that have focused largely on emissions and temperature outcomes. Third, we consider a large number of variables in our sensitivity analysis to develop a more complete understanding of the timing, feasibility, and impacts of uncertain CDR scale-up.

We use this modeling framework to address two research questions:

-

1.

What are the temperature outcomes of policies designed to meet a 2 °C target if they plan for different levels of CDR than are realized in the future?

-

2.

What are the global and regional effects of these planning decisions on the pathway of energy transitions, low-carbon investments, and stranded assets?

We find that planning for high CDR today may lead to minimal fossil fuel phase-out over the next few decades, resulting in an even more rapid energy transition or end-of-century temperature change of up to 2.4 °C if these levels of CDR are infeasible. Conversely, planning for low CDR today can lead to more rapid technology transitions in the next few decades and reduce pressure on hard-to-decarbonize sectors. If high CDR is later revealed to be feasible, end-of-century temperature change can be reduced from 2 °C to 1.5 °C.

Results

Carbon dioxide removal decision problem

We model the outcomes of planning for CDR in climate policy as a two-stage decision problem (see Fig. 1). First, in Stage 1, policymakers plan for a future state of the world where CDR deployment is high or low. Then, they design a climate policy in the form of a carbon price to meet a policy goal (e.g., limit global temperature change at the end of the century to 2 °C) under this CDR future. Second, in Stage 2, actors learn about the true future CDR potential. If they are correct in their predictions, they continue the climate policy as planned. If they are incorrect, there are two possible paths forward: (1) meet the original policy target, which will require enhanced actions (i.e., a higher carbon price) than anticipated if CDR potential is lower (and vice versa) or (2) keep the same policy (i.e., carbon price pathway) as before, resulting in a higher temperature change if CDR potential is lower (and vice versa). This decision framework produces six scenario narratives that we model in GCAM version 5.4 (see Methods). We refer to each scenario by its scenario label in Fig. 1.

We focus our analysis on a 2 °C end-of-century temperature target and a learning year of 2045 (i.e., one model period before mid-century). This target is consistent with current ambition in long-term pledges48 but exceeds the Paris goal to limit temperature change to well below 2 °C. For the high CDR scenario, we allow GCAM to select the level of CDR from BECCS and DACCS that results in the least-cost pathway to achieve the policy target. For the low CDR adoption scenario, we constrain annual removals from DACCS and total biomass use (including for BECCS) to 25% of levels observed in the high CDR scenario in each model period. We also examine the sensitivity of our results to different learning years (2030, 2035, 2040, and 2045), CDR ceilings (25% and 50%), and temperature targets (1.5 °C and 2 °C). Our approach does not permit levels of CDR to rise above the constraint, even in response to higher carbon prices, and thus represents a scenario where non-price (e.g., geophysical, environmental, technological, sociocultural, and institutional) factors are the main drivers of limits to CDR feasibility49.

Global emissions and temperature outcomes

Climate outcomes vary substantially across scenarios (see Fig. 2). These outcomes result from a net effect of four components: CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and industry (see Fig. 2a), CO2 removals from BECCS and DACCS (see Fig. 2b and SI Figs. S4 and S5), CO2 emissions and removals from the land sector (see SI Fig. S2), and non-CO2 emissions. Under a high CDR scenario (Plan High & Learn High), CO2 emissions increase slightly and do not begin to decline until 2040. These higher emissions are compensated by a substantial build-out of CDR that reaches 1.7 GtCO2 annually in 2050 and 27 GtCO2 in 2100. Conversely, under a low CDR scenario (Plan Low & Learn Low), CO2 emissions decline immediately and are halved by 2050. Net cumulative emissions from present day to the end of the century are also approximately 15% higher (see SI Information Fig. S1). By design, both scenarios reach 2 °C at the end of the century, but the high CDR scenario has a higher overshoot that peaks at 0.27 °C in 2075 and reaches net zero CO2 earlier (2075 vs. 2090 under a low CDR scenario). CDR also reduces the costs of climate change mitigation; the carbon price is nearly three times higher in both 2050 and 2100 under the low CDR scenario.

Global outcomes for the six scenario narratives (see Fig. 1) under a 2 °C end-of-century temperature target: a gross fossil fuel and industry CO2 emissions, b CO2 removal via DACCS, BECCS, and biomass liquids, c global mean temperature change, and d global carbon price. We show four of the six global carbon price pathways because scenarios without policy adjustment (indicated by the tag Keep Tax) follow the same carbon price trajectories as the Plan High & Learn High or Plan Low & Learn Low scenarios. Our policy does not directly include a tax on emissions from the land sector, but these emissions do vary across scenarios due to differences in bioenergy use (see SI Fig. S2).

Policymakers may plan for CDR levels that are different from what is realized in the future. If they plan for high CDR but later learn this is infeasible, they can increase the carbon price to meet the 2 °C goal, resulting in a dramatic (58%) reduction in CO2 emissions after the learning year. Alternatively, they can maintain the initial price trajectory, leading to a 0.4 °C temperature overshoot in 2100. If they plan for low CDR and later learn that high CDR is feasible, they can decrease the price trajectory, causing energy-related CO2 emissions to rebound by 55% in the learning year and remain the highest under any scenario through 2100. If instead they maintain their initial price trajectory while adopting high CDR, temperature change reaches 1.5 °C in 2100. While low CDR adoption is generally associated with higher carbon prices, prices in 2100 are 32% higher under a Plan High & Learn Low (Keep Target) scenario. This is the result of policymakers taking rapid action to reduce CO2 emissions after over-emitting prior to the learning year. By planning for low CDR, they can avoid this worst-case cost scenario.

Energy transitions, costs, and stranded assets

Major energy transitions occur across scenarios (see Figs. 3 and 4). However, before the learning year, scenarios planning for high CDR show no decline in unabated fossil fuel use in the electricity sector, whereas those planning for low CDR show an 81% decline by 2050 (see Fig. 3a). Near total (95%) phase-out in the electricity sector is reached by 2060 with low CDR and 2085 with high CDR. This faster retirement results in a cumulative 6.7 trillion USD in stranded assets, compared to 3.6 trillion USD with high CDR (see Fig. 3c). Electricity generation from low-carbon technologies also increases, with 91 and 108 trillion USD in cumulative low-carbon investments under high versus low CDR scenarios, respectively (see Fig. 3b, d). High CDR also leads to increased industrial energy demand, with DACCS consuming 12% of electricity for industry and 71% of natural gas in 2100, compared to 4% and 48% under the low CDR scenario (see Fig. 4a). In the transportation sector, low CDR leads to 40% lower energy demand and nearly three times higher electrification in 2100 (see Fig. 4b).

Global outcomes for the six scenario narratives (see Fig. 1) under a 2 °C end-of-century temperature target: a electricity generation over time from unabated fossil fuels (i.e., coal, natural gas, and oil without CCS), b electricity generation in 2050 and 2100 by technology type, color-coded by scenario, c cumulative stranded assets from fossil fuel power plants, and d cumulative low-carbon electricity investments. Low-carbon technologies are broadly defined to include renewable energy, BECCS, nuclear energy, and fossil fuels with CCS. Scenarios in b are color-coded as in other plots and labeled: (1) Plan High & Learn High, (2) Plan High & Learn Low (Keep Target), (3) Plan High & Learn Low (Keep Tax), (4) Plan Low & Learn Low, (5) Plan Low & Learn High (Keep Target), (6) Plan Low & Learn High (Keep Tax).

Global final energy use in a industry and b transportation for the six scenario narratives (see Fig. 1) under a 2 °C end-of-century temperature target. Energy use for DACCS in the industrial sector is substantial under the high CDR scenarios and is indicated separately with diagonal gray lines. Fossil fuels include direct burning and refined liquids from coal, natural gas, and oil; bioenergy includes solid and liquid bio-based fuels; fossil fuel energy for DACCS is natural gas. Scenarios are color-coded as in other plots and labeled: (1) Plan High & Learn High, (2) Plan High & Learn Low (Keep Target), (3) Plan High & Learn Low (Keep Tax), (4) Plan Low & Learn Low, (5) Plan Low & Learn High (Keep Target), (6) Plan Low & Learn High (Keep Tax). For more details on fossil fuel use across sectors, see SI Fig. S3.

The most rapid changes in the energy sector occur when policymakers plan for CDR levels that are different from what is realized in the future. If they plan for high CDR, later learn that it is infeasible, and respond by increasing the carbon price to meet the 2 °C target, this scenario results in a rapid 89% reduction in unabated fossil fuel generation after the learning year. This sudden transition translates to 5.6 trillion USD in additional stranded assets and 26 trillion USD in low-carbon investment (compared to the high CDR scenario, see Fig. 3c). Industry and transportation combined also exhibit the lowest energy use and highest electrification rates under this scenario (see Fig. 4a, b). Conversely, if policymakers plan for low CDR, learn that high CDR is possible, and continue to meet the 2 °C goal, unabated fossil fuel generation increases by 72% after the learning year. This rebound does not meaningfully affect stranded assets but temporarily depresses low-carbon investments by up to 26%. Cumulative stranded assets are slightly higher in the Keep Target scenario around mid-century due to increased electricity demand but later decrease below the Keep Tax scenario. Industry and transportation energy demand in 2100 is similar to if policymakers had planned for high CDR initially, due to a higher available carbon budget after the learning year.

Regional outcomes and equity implications

Planning for CDR under uncertainty can also have diverse and important regional implications. Even under a Plan High & Learn High scenario, 2.8 times more CO2 is emitted than removed from 2020 to 2100 on a global scale (see Fig. 5a, b). While the U.S. and China have the highest cumulative CO2 emissions and removals (collectively contributing 34% of emissions and 39% of removals), other countries such as Brazil contribute more heavily to removals (9% of removals vs. 2% of emissions) (see SI Table S4 and SI Figs. S4 and S5). These results are broadly consistent with previous literature (although we recognize there is variation across models)10,20. However, uncertainty in future CDR also presents unique equity challenges. We generally find that regions in the Global South with less historic responsibility for climate change see the greatest potential benefits and burdens from being wrong about CDR. Specifically, if policymakers plan for high CDR and later learn this is infeasible, regions across Africa, South America, and parts of South Asia see the highest percent reductions in CO2 emissions, relative to a scenario where high levels of CDR are realized (see Fig. 5c). However, if policymakers instead plan for low CDR and discover that high CDR is feasible, many of these same regions benefit most in terms of additional allowed emissions (see Fig. 5d).

Regional outcomes under a 2 °C end-of-century temperature target, including: a cumulative CO2 emissions for fossil fuels and industry from 2020 to 2100 in the Plan High & Learn High scenario, b cumulative CO2 removal from DACCS and BECCS (in both electricity and liquids) from 2020 to 2100 in the Plan High & Learn High scenario, c ratio of the difference in cumulative CO2 emissions in the Plan High & Learn High scenario and the Plan High & Learn Low (Keep Target) scenario over cumulative CO2 emissions in the Plan High & Learn High scenario (i.e., the percent reduction in CO2 emissions necessary to meet Paris goals if actors are wrong about high CDR), d ratio of the difference in cumulative CO2 emissions in the Plan Low & Learn High (Keep Target) scenario and Plan Low & Learn Low scenario over cumulative CO2 emissions in the Plan Low & Learn Low scenario (i.e., the allowed percent increase in CO2 emissions if actors are wrong about low CDR).

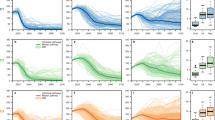

Sensitivity to policy timing and climate target

We also analyze how our results change with variations in the learning year (i.e., 2030, 2035, 2040, and 2045), CDR ceiling (i.e., 25% and 50%), and end-of-century temperature target (i.e., 1.5 °C and 2 °C). This sensitivity analysis results in a total of 70 model configurations (54 of which are solvable; see SI Table S6). We evaluate the global temperature, technology, and economic outcomes of these scenarios and present the full results in Supplementary Data File 1. There is value to learning early about the future potential of CDR. If policymakers learn they are wrong about CDR in 2030 and adjust to meet the 2 °C target, they can reduce total fossil fuel stranded assets by 1.0 trillion USD. Delayed learning about low CDR and more stringent CDR ceilings may make a 1.5 °C policy infeasible. A 50% CDR ceiling and a learning year of 2030 is the most stringent combination of parameters examined in this analysis that is feasible for a 1.5 °C Plan High & Learn Low (Keep Target) scenario. However, this scenario nearly quadruples the end-of-century carbon price (267% increase) and increases cumulative stranded assets by 6.1 trillion USD compared to the same scenario with a 2 °C policy target. Other feasible 1.5 °C scenarios include those with a 50% CDR ceiling and a learning year of 2030, 2035, 2040, or 2045 and all 2 °C scenario combinations. Scenarios with a 1.5 °C target and 25% CDR ceiling had very low solvability, limited to the Plan High & Learn High and the Plan High & Learn Low scenarios. See SI Tables S5 and S6 and Supplementary Data File 1 for a full summary of results.

Sensitivity analysis of a peak global mean temperature and global carbon price, and b cumulative fossil fuel stranded assets and low-carbon investment for the six scenario narratives (see Fig. 1). Here we consider four learning years (i.e., 2030, 2035, 2040, and 2045), two CDR ceilings (i.e., 25% and 50%), and two policy targets (i.e., 1.5 °C and 2 °C). The Plan High & Learn High and Plan Low & Learn Low scenarios do not vary across learning years, and the Plan High & Learn High scenario does not vary across CDR ceilings. The Plan High & Learn Low (Keep Tax) and Plan Low & Learn High (Keep Tax) scenarios have the same carbon price and stranded assets as the Plan High & Learn High or Plan Low & Learn Low scenarios; low-carbon investments vary due to the difference in BECCS. Due to low solvability, the following 1.5 °C scenarios are not presented above: Plan High & Learn Low (Keep Target) scenarios with a 50% CDR ceiling and a learning year of 2035, 2040, or 2045, and all scenarios with a 25% CDR ceiling. See SI Table S5 and Supplementary Data File 1 for full results.

Discussion

Strategies to meet net-zero and other climate goals set by governments (and in the private sector) often rely, implicitly or explicitly, on a large build-out of novel CDR technologies. It is thus important to understand how planning for CDR today could change the outcomes of climate policy in the future, particularly in situations where CDR potential is different from (and lower than) the levels featured in models used to inform emissions reduction targets and other mitigation benchmarks over the coming decades. We explore this question by modeling global scenarios where policymakers plan for one level of CDR (high or low) and later learn what level of deployment will be feasible. We represent low CDR feasibility by implementing a ceiling on adoption set to 25% of the annual removals observed in a baseline scenario to meet a 2 °C end-of-century temperature limit. This ceiling may represent a combination of technical, environmental, social, and political barriers to CDR build-out49.

If policymakers plan for a future state of the world with high CDR, CO2 emissions reductions in the energy sector are delayed, with emissions remaining relatively flat by mid-century under a 2 °C target (and decreasing by 33% from the present to 2050 under a 1.5 °C target; see Supplementary Data File 1). These delays could pose a challenge for mitigation if high CDR build-out is later revealed to be infeasible. If systems are able to adjust, the costs of being wrong may be substantial, including a 32% increase in end-of-century carbon prices and a 38% increase in cumulative fossil fuel stranded assets under a 2 °C target, compared to a scenario where policymakers planned for low CDR from the beginning. Under a 1.5 °C target, the costs of being wrong are even higher, and if policymakers learn too late (i.e., after 2045) that high CDR is not possible or constraints are sufficiently stringent (i.e., less than 50%), reaching 1.5 °C may be infeasible. The costs of being wrong are unevenly distributed across regions, and we find they may be disproportionately borne by lower income countries.

Public policies will be key to future innovation and upscaling of novel CDR technologies. A higher carbon price or more ambitious emissions reduction target may incentivize additional CDR (a feature that we do not capture in our modeling approach) if high prices are a major barrier to deployment. However, insights from the innovation literature suggest that a variety of targeted supply- and demand-side policies are also necessary to support technologies as they grow and scale. Importantly, recent work suggests that more ambitious demand-side policies from governments are needed to create markets to purchase the CDR that announcements by CDR companies currently anticipate will be available over the next decade9. Barriers and enablers to CDR are also interdependent, and well-designed policies may partially address social, cultural, environmental, and other barriers. While we do not assign probabilities to the low versus high CDR outcomes that we model in our scenarios, near-term policies can increase the likelihood of future scale-up through mid-century and beyond14,34. Deployment of CDR at scale can be costly (see SI Fig. S11), and realized levels of CDR will depend on how these costs compare to the costs of addressing residual emissions in hard-to-abate sectors.

As with all scenarios that represent climate policies over several decades, our storylines make various simplifying assumptions. We model CDR uncertainty as a two-stage decision problem with an exogenous constraint. However, future CDR may be driven by a combination of endogenous (e.g., carbon price) and exogenous factors. Our choice to use an exogenous constraint reflects both a recognition of the importance of non-price factors and the fact that CDR often functions as a backstop in models (and thus deployment can be insensitive to changes in costs). Additionally, some adjustments that we model (e.g., rapid emissions decline or rebound) may not be feasible in the real world; instead, they provide an illustration of the scale of transitions consistent with different policy structures and their associated costs. Actors may also adjust their behavior to reflect uncertainty in CDR, but current plans in both the public and private sector suggest this has yet to occur on a broad scale4,50. It is likely that learning will be an iterative process, potentially affording more opportunities to adjust if realized CDR falls short of plans. Future work can leverage methods in stochastic dynamic programming (building on prior studies46) and decision-making under deep uncertainty51 to more fully represent uncertainties in CDR scale-up and potential policy responses.

Designing effective and equitable climate policies requires attention to a variety of social, political, and environmental factors that are not fully represented in IAMs52,53. Our scenarios represent uncertainty in CDR for climate policy using a global carbon price and CDR ceilings, yet both of these are likely to exhibit high spatial variation. Equity outcomes can change under different policies and constraints, and future work could investigate the potential benefits of policies that explicitly target equity in planning for uncertainty in CDR. Additionally, the ability of actors to adjust after uncertainty is resolved may be limited and fall in between the two scenarios (i.e., keeping a target and keeping a tax) we present or occur more gradually over time. These features all highlight that the results we present are illustrative and designed to inform broad policy discussions on energy and climate targets (e.g., emissions reductions, fossil fuel phase-out, innovation and upscaling, etc.). Appropriate planning for CDR and other mitigation options should include a broad discussion of positive and negative side effects and engagement with communities where these technologies may be deployed.

Our results underscore the importance of robust climate policies. If CDR can reach widespread deployment, it may decrease the costs of climate policy. Whether this deployment is socially desirable will depend on how communities across the world balance this benefit with the potential side effects of CDR. However, if adopting CDR at scale is not feasible or desirable, the costs of planning for it can be high. To address this risk, policymakers can create incentives to support CDR technologies as they develop and scale while also accelerating emissions reductions from the energy system (thereby increasing the likelihood of an outcome like our Plan Low & Learn High (Keep Tax) scenario). If high CDR adoption is possible, policymakers can meet the same target with reduced pressure on hard-to-decarbonize sectors. This strategy may be equity-enhancing and result in relatively higher emissions reductions in high-income countries. Additionally, CDR innovation can enable policymakers to substantially increase their level of ambition in the future, reaching a 1.5 °C target at the end of the century by continuing the same policy that would only have reached 2 °C without a major build-out of CDR technologies.

Methods

The Global Change Analysis Model (GCAM)

We use the Global Change Analysis Model (GCAM) version 5.4 in this research. GCAM is an open-source integrated assessment model that represents interactions across five global systems: energy, socioeconomics, agriculture and land use, climate, and water. First developed in 1981 by the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL), GCAM is currently maintained by interdisciplinary researchers at the Joint Global Change Research Institute (JGCRI) at PNNL and the University of Maryland (github.com/JGCRI/gcam-core). GCAM is widely used in energy and climate policy assessment, as demonstrated by its role in reports published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change5,54 and designing and evaluating national climate strategies48,55. To optimize model performance and run time, we configure and access GCAM 5.4 via Docker (available at https://hub.docker.com/r/mnbindl/gcam-docker_v5-4). All scenarios are managed through the HTCondor Software Suite (HTCSS) at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for High Throughput Computing (CHTC)56.

GCAM characterizes system interactions across 32 geopolitical regions and 384 land-water regions from the year 1990 through 2100 at five-year time steps. It is a dynamic recursive model, meaning that it sequentially solves for market equilibrium prices and quantities across all sectors in each period without knowledge of the future, making it well-suited to answer questions about decision-making under uncertainty. Intertemporal optimization models, in contrast, find a solution using complete knowledge of future conditions. While both classes of model typically find a single “optimal” solution57, a growing number of studies have begun applying exploratory modeling methods to achieve targets via a variety of pathways58. Additionally, GCAM represents a diverse portfolio of CDR technologies, including DACCS and BECCS. More recent versions representing additional methods10 were not available at the start of this research. See SI Figs. S6 through S9 for comparisons between output from GCAM and other IAMs included in the AR6 Scenario Explorer and Database59.

GCAM uses a variety of inputs at the geopolitical and land-water region scale (see Calvin et al.60 for an overview). Exogenously-specified inputs include population, labor productivity, primary resource supply curves, and technology characteristics and costs. The model also takes inputs from previous model periods. Examples of these endogenous inputs include GDP (except for the initial historical year), market shares of individual technologies, and growth rates in agricultural crop yields. Using these inputs, GCAM sequentially solves for market equilibrium for each future model period while capturing key interactions across sectors (e.g., increased electricity demand from electrifying transportation and industry) and rich technology characteristics (e.g., energy and other inputs for DACCS). GCAM outputs a variety of metrics including commodity prices and consumption, energy transformation and use, emissions of greenhouse gases and regulated air pollutants, and radiative forcing and temperature change. We focus on a variety of output metrics available from the GCAM 5.4 release version of Main_queries.xml or calculated as described below. Code for all scenarios is available as Supplementary Files.

-

Positive CO2 emissions (Fig. 2a): We calculate global positive CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and industry using the “nonCO2 emissions by sector” query (which contains both CO2 and non-CO2 species). First, we subset the output for each scenario to include CO2 sources only. Next, we aggregate the emissions sources into negative (i.e., airCO2, regional biomass, regional biomassOil, regional corn for ethanol, and regional sugar for ethanol) and positive (i.e., all non-negative) categories. Focusing on positive emissions only, we convert the annual totals from units of MtC to GtCO2.

-

CO2 sequestration (Fig. 2b): We calculate global CO2 sequestration from novel CDR using the “CO2 sequestration by technology” query. First, we filter the output to include only the DACCS, BECCS (IGCC CCS), BECCS (conv CCS), and biomass liquids subsectors for all scenarios, excluding CO2 sequestration from fossil fuels and cement. We aggregate CO2 sequestration for these technology types by year and scenario and convert the annual totals from units of MtC to GtCO2.

-

Temperature change (Fig. 2c): We calculate global temperature change directly (in °C) from the “global mean temperature” query for each scenario.

-

Global carbon price (Fig. 2d): We calculate the global carbon price from the “CO2 prices” query for each scenario. Due to differences in scenario configuration, these prices have different labels but convey the same concept (“globalCO2_LTG” for the Plan & Right scenarios and “globalCO2” for the Plan High & Learn Low (Keep Target) and Plan Low & Learn High (Keep Target) scenarios). For easier interpretation, we convert prices to units of $1,000/tC.

-

Unabated fossil fuel electricity generation (Fig. 3a): We calculate global electricity generation from unabated fossil fuels using the “elec gen by gen tech” (i.e., electricity generation by generation technology) query. First, we filter the output to include only fossil fuels without CCS (i.e., coal (IGCC), coal (conv pul), coal cogen, gas (CC), gas (steam/CT), gas cogen, refined liquids (CC), refined liquids (steam/CT), and refined liquids cogen). We then aggregate electricity generation totals (in EJ) by scenario and year.

-

Electricity generation by technology type (Fig. 3b): We calculate electricity generation by technology type for the years 2050 and 2100 using the “elec gen by gen tech” query. We aggregate this output into the following technology types for each scenario: fossil fuels without CCS (i.e., coal (IGCC), coal (conv pul), coal cogen, gas (CC), gas (steam/CT), gas cogen, refined liquids (CC), refined liquids (steam/CT), refined liquids cogen); fossil fuels with CCS (i.e., coal (IGCC CCS), coal (conv pul CCS), gas (CC CCS), refined liquids (CC CCS)); renewable and nuclear energy technologies (i.e., geothermal, hydro, rooftop_pv, CSP, PV, wind, wind_offshore, biomass (IGCC), biomass (conv), biomass cogen, Gen_III, Gen_II_LWR); and BECCS (i.e., biomass (IGCC CCS) and biomass (conv CCS)). For each technology category, we subset the output to include only the years 2050 and 2100.

-

Cumulative fossil fuel stranded assets (Fig. 3c): We calculate global cumulative fossil fuel stranded assets in the power sector using the “elecCumRetPrematureCost” (i.e., cumulative premature retirements) parameter from the GCAM-compatible plutus R package (available at https://github.com/JGCRI/plutus). First, we calculate capital and stranded costs for each scenario listed above using the gcamInvest function. Using the data aggregated to class 1 (i.e., dataAggClass1), we filter the output to include only fossil fuels (i.e., coal, coal CCS, gas, gas CCS, oil, and oil CCS). We then aggregate stranded asset totals by scenario and year and convert costs to units of trillion 2010 USD for easier interpretation.

-

Cumulative low-carbon technology investment (Fig. 3d): As with the stranded asset calculations, we use plutus to calculate global cumulative investment in low-carbon energy technologies. Using the data aggregated to class 1 (i.e., dataAggClass1), we extract data for the “elecCumCapCost” (i.e., cumulative electricity capacity installations) parameter. Next, we filter the data to exclude fossil fuels (i.e., coal, oil, and gas) and aggregate investment totals by scenario and year. For easier interpretation, we convert investments to units of trillion 2010 USD.

-

Final energy in industry (Fig. 4a): We calculate global final energy use by energy source in the industrial sector for the years 2050 and 2100 using the “industry final energy by tech and fuel” (i.e., industry final energy by technology type and fuel) query. First, we group energy inputs into the following categories: hydrogen, electricity, refined liquids, biofuel, gas, and coal. We then identify any energy sources that relate to DACCS (i.e., subsectors containing the strings “dac” or “CCS”). For each technology category, we subset the output to include only the years 2050 and 2100. We further calculate the contribution of biomass-based refined liquids and fossil-fuel-based refined liquids to the broader refined liquids category. To do this, we use the “refined liquids production by tech” (i.e., refined liquids production by technology) query and aggregate production into biomass-based refined liquids (contains FT biofuel with and without CCS, biodiesel, cellulosic ethanol, cellulosic ethanol CCS, corn ethanol, and sugarcane ethanol) and fossil-fuel-based refined liquids (contains coal to liquids, coal to liquids CCS, gas to liquids, and oil refining). We calculate the percentage of refined liquids that are biomass-based by dividing the biomass subcategory total by total production across all fuel types. We perform this calculation for the years 2050 and 2100 and repeat this process for the fossil fuel subcategory. We then recategorize the energy sources as follows: hydrogen, electricity, bioenergy (contains biofuels and refined liquids from biomass), and fossil fuels (contains coal, gas, and refined liquids from fossil fuels). Final energy use related to DACCS is overlaid as hashed lines in the final figure.

-

Final energy in transportation (Fig. 4b): We calculate global final energy use by energy source in the transportation sector for the years 2050 and 2100 using the “transport final energy by fuel” query. First, we group energy inputs into the following categories: hydrogen, electricity, refined liquids, gas, and coal. For each technology category, we subset the output to include only the years 2050 and 2100. We then calculate the contribution of biomass-based refined liquids and fossil-fuel-based refined liquids to the broader refined liquids category using the process outlined for Fig. 4a. We then recategorize the energy sources as follows: hydrogen, electricity, bioenergy (contains biofuels and refined liquids from biomass), and fossil fuels (contains coal, gas, and refined liquids from fossil fuels).

-

Regional cumulative positive CO2 emissions map (Fig. 5a): We calculate regional positive CO2 for the Plan High & Learn High scenario using the same process as in Fig. 2a. We subset the data to include only the years 2020 through 2100 and perform a standard linear interpolation to obtain annual output. We then aggregate the annual output and plot the resulting cumulative totals for each region.

-

Regional cumulative CO2 removal map (Fig. 5b): We calculate regional CO2 removal from novel CDR (i.e., DACCS, BECCS, and biomass liquids) for the Plan High & Learn High scenario using the same process as in Fig. 2b. We subset the data to include only the years 2020 through 2100 and perform a standard linear interpolation to obtain annual output. We then aggregate the annual output and plot the resulting cumulative totals for each region.

-

Regional burden if wrong about high CDR (Fig. 5c): We calculate regional burden of being wrong about high CDR as the ratio of the difference in cumulative CO2 emissions in the Plan High & Learn High scenario and the Plan High & Learn Low (Keep Target) scenario over cumulative CO2 emissions in the Plan High & Learn High scenario (see Fig. 5 caption and Table 1).

Table 1 Measures to evaluate regional equity -

Regional benefit if wrong about low CDR (Fig. 5d): We calculate regional benefit of being wrong about low CDR as the ratio of the difference in cumulative CO2 emissions in the Plan Low & Learn High (Keep Target) scenario and Plan Low & Learn Low scenario over cumulative CO2 emissions in the Plan Low & Learn Low scenario (see Fig. 5 caption and Table 1).

-

CO2 price versus global mean temperature sensitivity analysis (Fig. 6a): This figure presents results across all temperature targets (i.e., 1.5 °C and 2 °C), learning years (i.e., 2030, 2035, 2040, 2045), and CDR ceilings (i.e., 25% and 50%). We follow the same above processes for calculating carbon price and global mean temperature, but select only the maximum value for each variable and scenario.

-

Stranded assets versus low-carbon investment sensitivity analysis (Fig. 6b): This figure presents results across all temperature targets, learning years, and CDR ceilings. We follow the same above processes for calculating stranded assets and low-carbon investment and select the maximum value for each variable and scenario.

Scenario design and implementation

We model climate policy design in GCAM under uncertainty about CDR potential as a two-stage decision problem using six scenario narratives (see Fig. 1 for an overview and scenario labels, which we use in describing the scenarios in this section). These scenarios are fully reproducible using both: (1) standard GCAM configuration files (which can be found at github.com/JGCRI/gcam-core or https://hub.docker.com/r/mnbindl/gcam-docker_v5-4) and (2) new files developed for this research (provided as Supplementary Data Files). We begin by running the GCAM 5.4 default policy configuration (which we refer to as the Plan High & Learn High scenario) in target finder mode (with a 2 °C target). Target finder mode allows GCAM to iterate over a scenario until it finds a least-cost path to achieve a given climate target. This scenario uses standard GCAM input files and enables DACCS, which is not enabled by default in GCAM 5.4. To improve model solvability, we disable the regional water supply constraint and remove a policy configuration file that includes regional near-term carbon prices to slightly adjust emissions in 2020, with minimal effects on the results.

After obtaining the Plan High & Learn High scenario output, we calculate total annual CO2 removal across the three modeled DACCS technology types (i.e., high temperature natural gas, high temperature electric, and low temperature heat pump) and total biomass for bioenergy (including BECCS) by technology type (i.e., biomass for electricity and other biofuels). We then create a ceiling on these totals to not exceed a fixed percentage of the levels observed in the Plan High & Learn High scenario in each model period. We re-run GCAM with the same modifications described above and this additional constraint pathway to create our Plan Low & Learn Low scenario. Note that we place a single ceiling on biomass use across sectors via the regional biomass, corn for ethanol, sugar for ethanol, and biomass oil sectors and a single ceiling on DACCS across technology types. In our main scenarios, both BECCS and DACCS are limited in each five-year time step to 25% of their use in the Plan High & Learn High scenario. This threshold was determined by finding the lowest CDR ceiling (in 5% intervals) for which all model periods solved completely for all learning years (i.e., 2030, 2035, 2040, and 2045).

In the Plan High & Learn Low (Keep Target) and Plan Low & Learn High (Keep Target) scenarios, policy effort prior to the learning year is represented by specifying a global carbon price for each five-year time step from 2025 up to the learning year. If actors plan for high future CDR, the global carbon price is set to follow the same near-term pathway as the Plan High & Learn High scenario; if they plan for low future CDR, it follows the same pathway as the Plan Low & Learn Low scenario. In both cases, all non-CO2 greenhouse gases are included in the carbon market using their standard Global Warming Potential (GWP) values61. In the learning year, target finder is activated alongside a change in CDR ceiling to represent actors learning about CDR potential and adjusting to meet the policy target. If CDR potential is low, then BECCS and DACCS are limited to 25% of their use in the Plan High & Learn High scenario; if CDR potential is high, then BECCS and DACCS may reach their full use potential (i.e., 100% of their use in the Plan High & Learn High scenario) but not exceed it.

In the Plan High & Learn Low (Keep Tax) and Plan Low & Learn High (Keep Tax) scenarios, a complete global carbon price pathway is specified for each five-year time step from 2025 through 2100. If planning for high CDR, the global carbon price follows the exact same pathway as in the Plan High & Learn High scenario, and CDR ceilings follow the same pathway as in the Plan High & Learn Low (Keep Target) scenario. If planning for low future CDR, the global carbon price will follow the exact same pathway as the Plan Low & Learn Low scenario, and CDR ceilings will follow the same pathway as the Plan Low & Learn High (Keep Target) scenario. Note that under the Plan Low & Learn High (Keep Target) scenario, modeled CDR levels could in theory reach higher values than seen in the Plan High & Learn High scenario. We again constrain CDR levels so they cannot exceed the levels observed in the Plan High & Learn High scenario.

Data analysis

Output was obtained from GCAM database files and analyzed at a global or regional level using R version 4.2.1 and RStudio version 2024.04.2 + 764. We first use rgcam version 1.2.0 (available at https://github.com/JGCRI/rgcam) to import GCAM database output into R for analysis and visualization. Project data files containing relevant queries were created for each scenario. Output from each query (e.g., carbon prices) are imported, modified as data frames, and visualized using ggplot2 version 3.5.1. These include the cost and level of CO2 emissions reduction under different CDR planning scenarios, climate indicators (e.g., global mean temperature), and various technical, economic, and environmental variables across sectors (e.g., electricity generation and stranded assets). We calculate cumulative stranded asset costs and investments in the electricity generation sector using plutus version 0.1.0 (available at https://github.com/JGCRI/plutus). Configuration files for all 62 attempted scenarios in the main analysis and sensitivity analysis as well as curated output for all 54 solvable scenarios are included as Supplementary Data Files.

We also calculate four measures to evaluate equity-relevant relationships between cumulative CO2 emissions and removals at a regional scale (see Fig. 5 and Table 1).

Sensitivity analysis

We perform a sensitivity analysis to explore how our results change with changes in the learning year, CDR ceiling, and end-of-century temperature target. In addition to the parameters featured in the main analysis, we consider a temperature target of 1.5 °C, CDR ceiling of 50%, and learning years of 2030, 2035, and 2040. This results in 64 supplementary scenarios, which are presented in full in SI Table S6 and summarized in Fig. 6. Due to the ambitious nature of some parameter combinations (i.e., a 1.5 °C target with delayed learning about low CDR potential), not all models solve. We characterize a scenario as unsolvable if GCAM experiences a core dump during the computation process or if scenario output repeatedly (≥3 occurrences) contains unsolved model periods. Note that as the model approaches the edge of solvability, some scenarios may not solve that are strictly less constrained (e.g., earlier learning year) than ones that do solve. We report scenario solvability in SI Table S6 and available output in Supplementary Data File 1.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data (scenario output) used in this study can be reproduced with the Global Change Analysis Model (GCAM) and associated input files (see Code Availability). Select output data for each scenario are available in Supplementary Data File 1.

Code availability

The Global Change Analysis Model (GCAM) version 5.4 is an open-source integrated assessment model, available at https://github.com/JGCRI/gcam-core/releases. GCAM was built using Docker to run on our Center for High Throughput Computing (CHTC)56 and published at mnbindl/gcam-docker_v5-4:v1. GCAM output was analyzed using rgcam version 1.2.0, available at https://github.com/JGCRI/rgcam. Configuration files for all 62 attempted scenarios in the main analysis and sensitivity analysis as well as curated output for all 54 solvable scenarios are included as Supplementary Data Files.

References

Iyer, G. et al. Ratcheting of climate pledges needed to limit peak global warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 1129–1135 (2022).

Hultman, N. E. et al. Fusing subnational with national climate action is central to decarbonization: the case of the United States. Nat. Commun. 11, 5255 (2020).

Hale, T. N. et al. Sub- and non-state climate action: a framework to assess progress, implementation and impact. Clim. Policy 21, 406–420 (2021).

Surana, K. et al. The role of corporate investment in start-ups for climate-tech innovation. Joule https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2023.02.017 (2023).

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Global Warming of 1.5°C: An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C Above Pre-industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty (2018).

van Beek, L., Hajer, M., Pelzer, P., van Vuuren, D. & Cassen, C. Anticipating futures through models: the rise of Integrated Assessment Modelling in the climate science-policy interface since 1970. Glob. Environ. Change 65, 102191 (2020).

Warszawski, L. et al. All options, not silver bullets, needed to limit global warming to 1.5 °C: a scenario appraisal. Environ. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abfeec (2021).

Fuhrman, J., McJeon, H., Doney, S. C., Shobe, W. & Clarens, A. F. From Zero to Hero?: Why integrated assessment modeling of negative emissions technologies is hard and how we can do better. Front. Clim. 1, 11 (2019).

Smith, S. et al. The state of carbon dioxide removal - 2nd Edition. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/F85QJ (2024).

Fuhrman, J. et al. Diverse carbon dioxide removal approaches could reduce impacts on the energy–water–land system. Nat. Clim. Chang. 1–10 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01604-9 (2023).

Morrow, D. R., Apeaning, R. & Guard, G. GCAM-CDR v1.0: enhancing the representation of carbon dioxide removal technologies and policies in an integrated assessment model. Geosci. Model Dev. 16, 1105–1118 (2023).

Consoli, C. Bioenergy and Carbon Capture and Storage: 2019 Perspective. Global CCS Institute, Melbourne, Australia (2019).

Gambhir, A. & Tavoni, M. Direct air carbon capture and sequestration: how it works and how it could contribute to climate-change mitigation. One Earth 1, 405–409 (2019).

Edwards, M. R. et al. Modeling direct air carbon capture and storage in a 1.5 °C climate future using historical analogs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2215679121 (2024).

Minx, J. C. et al. Negative emissions—Part 1: Research landscape and synthesis. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 063001 (2018).

European Academies Science Advisory Council. Negative emission technologies: What role in meeting Paris Agreement targets? German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina (2018).

Fuss, S. et al. Negative emissions—Part 2: Costs, potentials and side effects. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 063002 (2018).

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Negative Emissions Technologies and Reliable Sequestration: A Research Agenda. https://doi.org/10.17226/25259. (The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2019).

Sievert, K., Schmidt, T. S. & Steffen, B. Considering technology characteristics to project future costs of direct air capture. Joule 8, 979–999 (2024).

Fuhrman, J. et al. Food–energy–water implications of negative emissions technologies in a +1.5 °C future. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 920–927 (2020).

Fuhrman, J. et al. The role of direct air capture and negative emissions technologies in the shared socioeconomic pathways towards +1.5 °C and +2 °C futures. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 114012 (2021).

Smith, P. et al. Biophysical and economic limits to negative CO 2 emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 42–50 (2016).

Deprez, A. et al. Sustainability limits needed for CO2 removal. Science 383, 484–486 (2024).

Zahasky, C. & Krevor, S. Global geologic carbon storage requirements of climate change mitigation scenarios. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 1561–1567 (2020).

Kearns, J. et al. Developing a consistent database for regional geologic CO2 storage capacity Worldwide. Energy Procedia 114, 4697–4709 (2017).

Cox, E., Spence, E. & Pidgeon, N. Public perceptions of carbon dioxide removal in the United States and the United Kingdom. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 744–749 (2020).

Low, S., Fritz, L., Baum, C. M. & Sovacool, B. K. Public perceptions on carbon removal from focus groups in 22 countries. Nat. Commun. 15, 3453 (2024).

Hepburn, C. et al. The technological and economic prospects for CO2 utilization and removal. Nature 575, 87–97 (2019).

Shrum, T. R. et al. Behavioural frameworks to understand public perceptions of and risk response to carbon dioxide removal. Interface Focus 10, 20200002 (2020).

Otto, D., Thoni, T., Wittstock, F. & Beck, S. Exploring narratives on negative emissions technologies in the Post-Paris Era. Front. Clim. 3, 684135 (2021).

Buck, H. J. et al. Evaluating the efficacy and equity of environmental stopgap measures. Nat. Sustain 3, 499–504 (2020).

Hart, P. S., Campbell-Arvai, V., Wolske, K. S. & Raimi, K. T. Moral hazard or not? The effects of learning about carbon dioxide removal on perceptions of climate mitigation in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 89, 102656 (2022).

Prütz, R., Fuss, S., Lück, S., Stephan, L. & Rogelj, J. A taxonomy to map evidence on the co-benefits, challenges, and limits of carbon dioxide removal. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 1–11 (2024).

Nemet, G., Greene, J., Müller-Hansen, F. & Minx, J. C. Dataset on the adoption of historical technologies informs the scale-up of emerging carbon dioxide removal measures. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 1–10 (2023).

Roberts, C. & Nemet, G. Systematic Historical Analogue Research for Decision-making (SHARD): introducing a new methodology for using historical case studies to inform low-carbon transitions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 93, 102768 (2022).

Malhotra, A. & Schmidt, T. S. Accelerating low-carbon innovation. Joule 4, 2259–2267 (2020).

Meckling, J. & Biber, E. A policy roadmap for negative emissions using direct air capture. Nat. Commun. 12, 2051 (2021).

Hanna, R., Abdulla, A., Xu, Y. & Victor, D. G. Emergency deployment of direct air capture as a response to the climate crisis. Nat. Commun. 12, 368 (2021).

Batres, M. et al. Environmental and climate justice and technological carbon removal. Electricity J. 34, 107002 (2021).

Morrow, D. R. et al. Principles for thinking about carbon dioxide removal in just climate policy. One Earth 3, 150–153 (2020).

Honegger, M., Poralla, M., Michaelowa, A. & Ahonen, H.-M. Who Is paying for carbon dioxide removal? Designing policy instruments for mobilizing negative emissions technologies. Front. Clim. 3, 672996 (2021).

Fyson, C. L., Baur, S., Gidden, M. & Schleussner, C.-F. Fair-share carbon dioxide removal increases major emitter responsibility. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 836–841 (2020).

Peters, G. P., Andrew, R. M., Solomon, S. & Friedlingstein, P. Measuring a fair and ambitious climate agreement using cumulative emissions. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 105004 (2015).

Realmonte, G. et al. An inter-model assessment of the role of direct air capture in deep mitigation pathways. Nat. Commun. 10, 3277 (2019).

Pradhan, S. et al. Effects of direct air capture technology availability on stranded assets and committed emissions in the power sector. Front. Clim. 3, 660787 (2021).

Grant, N., Hawkes, A., Mittal, S. & Gambhir, A. The policy implications of an uncertain carbon dioxide removal potential. Joule 5, 2593–2605 (2021).

Grant, N., Hawkes, A., Mittal, S. & Gambhir, A. Confronting mitigation deterrence in low-carbon scenarios. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 064099 (2021).

van de Ven, D.-J. et al. A multimodel analysis of post-Glasgow climate targets and feasibility challenges. Nat. Clim. Chang. 13, 570–578 (2023).

Steg, L. et al. A method to identify barriers to and enablers of implementing climate change mitigation options. One Earth 5, 1216–1227 (2022).

Buck, H. J., Carton, W., Lund, J. F. & Markusson, N. Why residual emissions matter right now. Nat. Clim. Chang. 13, 351–358 (2023).

Lempert, R. J. et al. The use of decision making under deep uncertainty in the IPCC. Front. Clim. 6, 1380054 (2024).

Giang, A. et al. Equity and modeling in sustainability science: examples and opportunities throughout the process. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2215688121 (2024).

Peng, W. et al. Climate policy models need to get real about people — here’s how. Nature 594, 174–176 (2021).

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the IPCC. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland (2014).

United States Executive Office of the President & U.S. Department of State. The Long‑Term Strategy of the United States: Pathways to Net‑Zero Greenhouse Gas Emissions by 2050. Washington, DC : U.S. Executive Office of the President & Department of State (2021).

Center for High Throughput Computing. Center for High Throughput Computing. https://doi.org/10.21231/GNT1-HW21 (2006).

Wilkerson, J. T., Leibowicz, B. D., Turner, D. D. & Weyant, J. P. Comparison of integrated assessment models: carbon price impacts on U.S. energy. Energy Policy 76, 18–31 (2015).

Kwakkel, J. H. The exploratory modeling workbench: an open source toolkit for exploratory modeling, scenario discovery, and (multi-objective) robust decision making. Environ. Model. Softw. 96, 239–250 (2017).

International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis. AR6 Scenario Explorer and Database hosted by IIASA. https://data.ene.iiasa.ac.at/ar6/#/login (2022).

Calvin, K. et al. GCAM v5.1: representing the linkages between energy, water, land, climate, and economic systems. Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 677–698 (2019).

Joint Global Change Research Institute. GCAM v5.4 Documentation: GCAM Policy Examples. http://jgcri.github.io/gcam-doc/v5.4/policies_examples.html#linked-policy (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the University of Wisconsin-Madison Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education with funding from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF). We also thank Jay Fuhrman for helpful discussions on CDR costs. Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (G-2021-14177): M.R.E. and M.B. Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation: M.B.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: M.R.E. Data curation: M.B. Formal analysis: M.B. and M.R.E. Funding acquisition: M.R.E. Investigation: M.B. Methodology: M.R.E., M.B., and R.C. Project administration: M.R.E. Resources: R.C. Software: M.B. Supervision: M.R.E. Visualization: M.B. Writing – original draft: M.B. and M.R.E. Writing – review and editing: M.R.E., M.B., and R.C.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bindl, M., Edwards, M.R. & Cui, R.Y. Risks of relying on uncertain carbon dioxide removal in climate policy. Nat Commun 16, 5958 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61106-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61106-4

This article is cited by

-

The importance of radical transparency for responsible carbon dioxide removal

npj Climate Action (2026)